Regular Article

Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with Internet

addiction: Comparison with substance use

Ju-Yu Yen,

MD,

1,2Chih-Hung Ko,

MD

,

1,3Cheng-Fang Yen,

MD

,

PhD,

1,4Sue-Huei Chen,

PhD,

5Wei-Lun Chung,

MD6and Cheng-Chung Chen,

MD,

PhD1,4,61Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital,2Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Municipal

Hsiao-Kang Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung,3Graduate Institute of Medicine, College of Medicine,

Kaohsiung Medical University,4Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical

University,6Jsyr-Huey Mental Hospital, Kaohsiung and5Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taipei,

Taiwan

Aims: The aim of the present study was to compare psychiatric symptoms between adolescents with and without Internet addiction, as well as between analogs with and without substance use.

Methods: A total of 3662 students (2328 male and 1334 female) were recruited for the study. Self-report scales were utilized to assess psychiatric symptoms, Internet addiction, and substance use.

Results: It was found that Internet addiction or sub-stance use in adolescents was associated with more severe psychiatric symptoms. Hostility and depres-sion were associated with Internet addiction and sub-stance use after controlling for other symptoms.

Conclusions: This result partially supports the hypothesis that Internet addiction should be included in the organization of problem behavior theory, and it is suggested that prevention and inter-vention can best be carried out when grouped with other problem behaviors. Moreover, more attention should be devoted to hostile and depressed adoles-cents in the design of preventive strategies and the related therapeutic interventions for Internet addiction.

Key words: adolescent,depression,hostility,Internet addiction,psychiatric symptom,substance use.

T

HE INTERNET HAS become one of the most popular media and it is utilized by adolescents to enforce their competitiveness, but heavy use of the Internet results in many negative effects. Young has defined problematic Internet-using behavior as ‘Internet addiction’,1 while Ko et al. have proposeddiagnostic criteria to define adolescent Internet addic-tion.2 Based on this definition, epidemiological

evaluation in Taiwan has demonstrated that 19.8% of adolescents have Internet addiction.3 Adolescents

with Internet addiction usually suffer from problems with their daily routines, school performance, family relationships, and mood.4–6However, the question of

whether this would produce negative impacts on general mental health and produce more severe psy-chiatric symptoms is hitherto unknown. Although depression, lower self-esteem and lower life satisfac-tion have been reported in adolescents with Internet addiction,4,6,7 the general psychopathology has not

been evaluated completely.

According to problem behavior theory, use of alcohol, smoking, and illicit substance use have been grouped as problem behaviors of adolescents, which have the same psycho-social proneness, including social environment, perceived environment, person-ality, and behavior.8It has been suggested that

inter-vention programs directed at the organization of

Correspondence address: Cheng-Chung Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, 100 Tzyou 1st Rd. Kaohsiung City 807, Taiwan. Email: ccchen@mail.khja.org.tw Received 23 October 2006; revised 24 July 2007; accepted 27 August 2007.

problem behaviors may be more appropriate than those that have focused on specific behaviors alone.8

Internet addiction emerged as a behavior problem in adolescents after the Internet was well developed. It has not been included or comprehensively compared to previously defined problem behaviors. If Internet addiction is a new problem behavior, treatment inter-ventions should be developed in comprehensive pro-grams for this problem behavior. Previous reports derived from the same data of the present study have found that Internet addiction shares similar person-ality and family patterns of substance experience in adolescents.9,10If we hypothesize that Internet

addic-tion is one of the problem behaviors defined by problem behavior theory (as Jessor argued in a review of problem behavior that adolescent problem behav-ior would result in similar health compromising out-comes8), Internet addiction may jeopardize mental

health just as do other problem behaviors. Yet, the psychiatric symptoms of adolescents with Internet addiction and substance use have not been compared directly.

A previous report demonstrated that teenagers with substance use problems have more severe psychiatric symptoms.11 As substance use,12 Internet addiction

has been reported to be associated with depres-sion4,6 and attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder.13

Further, heavy Internet users have more severe psychopathology on the Symptoms Checklist 90 Revised.14,15However, because there is no clear

defi-nition of Internet addiction in these two previous reports, whether adolescents with Internet addiction had poor mental health is unknown.

Until now, there is no conclusive definition for Internet addiction. According to the Ko et al. study, the criteria for adolescent Internet addiction are as follows.2 Criterion A contains nine characteristic

symptoms of Internet addiction, including preoccu-pation, uncontrolled impulse, usage more than intended, tolerance, withdrawal, impairment of control, excessive time and effort spent on the Inter-net, and impairment of decision-making ability. Six or more criteria should be fulfilled in Criteria A. Cri-terion B describes functional impairment secondary to Internet use. Criterion C lists the exclusive criteria to eliminate the possibility of psychotic disorder and bipolar I disorder. The diagnostic criteria with good diagnostic accuracy (95.4%), specificity (97.1%), and accepted sensitivity (87.5%)2 could

provide a clear definition to further evaluate the correlates of Internet addiction in epidemiological

research. Accordingly, in the present study the defi-nition of Internet addiction was based on these diagnostic criteria.

Thus, in order to evaluate and compare the psychi-atric symptoms for adolescents with Internet addic-tion and those with substance use, the aims of the present study were to compare psychiatric symptoms between adolescents with and without Internet addiction, as well as between analogs with and without substance use.

METHODS

Participants

Seven of 87 junior high schools, six of 33 senior high schools, and four of 20 vocational high schools in Kaohsiung City and County in Taiwan were selected for evaluation. The selected schools included eight, five, and three schools from urban, suburban, and rural areas, respectively. Two classes were randomly selected from each grade in these schools. A total of 3662 students (2328 male participants and 1334 female participants) were recruited. The mean of their age was 15.48⫾ 1.65 years (range 11–21 years). After an informed consent form describing the goal of research had been completed by students, they were invited to anonymously complete a question-naire identifying psychiatric symptoms, and explor-ing the extent of Internet use/addiction or experience of substance use. Those who did not complete the questionnaires were excluded from the statistical analysis. The data for the 3517 respondents (2218 male and 1299 female; completion rate, 96.0%) were entered into the final statistical analysis. Approval was also granted by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Municipal Hsiao-Kang Hospital before commencement.

Measurement instruments

Brief Symptoms Inventory

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) is a shortened form of the Symptoms Checklist 90 Revised.16,17It is

a 53-item self-report symptom scale designed to measure levels of psychopathology. The BSI mea-sures nine symptom dimensions: somatization, obsession–compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, para-noid ideation and psychoticism. Additionally, there

are three global indices of distress, the General Sever-ity Index (GSI), the Positive Symptom Total (PST), and the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI). The ranges for test–retest values and internal consistency reliability (a coefficients) were 0.68–0.91 and 0.71– 0.85, respectively.16

Chen Internet Addiction Scale

The Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS) consists of 26 items, scored on a 4-point Likert scale, that assess five dimensions of symptoms of compulsive use, withdrawal, tolerance, and problems of interpersonal relationships and health/time management. The total scores of the CIAS ranged from 26 to 104. Higher CIAS scores indicated increased severity of Internet addiction. In the original study, the internal reliabil-ity of the instrument and its subscales ranged from 0.79 to 0.93 and correlation analyses yielded signifi-cantly positive correlation of total scale and subscale scores of CIAS with the hours spent weekly on Internet activity.18 Based on diagnostic interviews

conducted according to established criteria for Inter-net addiction,2a threshold CIAS score of 63/64 was

deemed to provide good diagnostic accuracy (87.6%) with respect to Internet addiction in adolescents.3

Participants who had a CIAS score>63 were classified as the Internet addiction group.

Questionnaire for Experience of Substance Use

The Questionnaire for Experience of Substance Use (Q-ESU) inquires dichotomously whether partici-pants currently regularly used tobacco, alcohol, or betel nut, or whether they had ever experienced cannabis, amphetamines, glue, heroin, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or ketamine.19

Statistical analysis

The participants who fitted the diagnostic cut-off point of the CIAS were classified as Internet addicts. The most common pattern of substance use in ado-lescents is occasional use, which does not fulfill DSM-IV criteria for substance use or dependence. But because any pattern of use of illicit substances by adolescents is potentially hazardous, any illicit sub-stance use is usually used to define the at-risk group of adolescents.20 In contrast, the experience of

alcohol or tobacco use is common among adoles-cents,20 thus, current regular use of tobacco and

alcohol is appropriate to define an at-risk group among adolescents.21,22 In the present study we

defined subjects with substance use experience as adolescents who had had an experience of illicit sub-stance use, or regular use of alcohol, tobacco, or betel nut based on the Q-ESU.

The t-test was used to compare psychiatric symp-toms on the BSI subscale and its three global indices for adolescents with or without Internet addiction, and those with or without substance use. Associa-tions between psychiatric symptoms and Internet addiction and substance use were further examined using logistic regression analysis controlling for the effects of gender, age and school type. In order to make comparisons between Internet addiction and substance use, all dimensions of the BSI were entered into the regression model. P< 0.05 was considered significant for all tests.

RESULTS

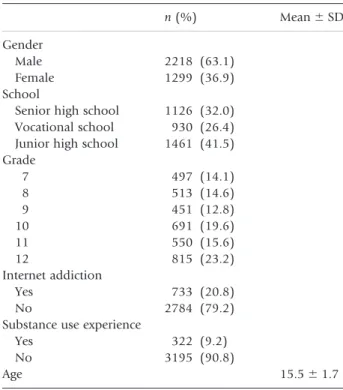

The demographic data and prevalence rate of Inter-net addiction and substance use of participants are shown in Table 1. A total of 733 (20.8%) and 322 (9.2%) participants were classified into the Inter-net addiction group and substance use group, respectively.

Table 1. Subject data

n (%) Mean⫾ SD Gender

Male 2218 (63.1) Female 1299 (36.9) School

Senior high school 1126 (32.0) Vocational school 930 (26.4) Junior high school 1461 (41.5) Grade 7 497 (14.1) 8 513 (14.6) 9 451 (12.8) 10 691 (19.6) 11 550 (15.6) 12 815 (23.2) Internet addiction Yes 733 (20.8) No 2784 (79.2) Substance use experience

Yes 322 (9.2) No 3195 (90.8)

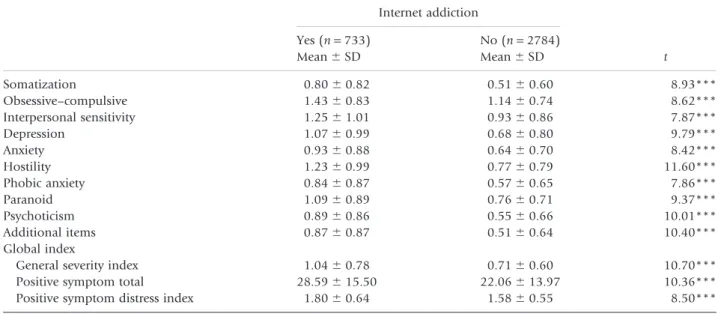

The comparisons of scores on all dimensions and three global indices on BSI between adolescents with and without Internet addiction are shown in Table 2. Results demonstrated that adolescents with Internet addiction had higher scores on GSI, PST,

PSDI and all dimensions. The comparisons of scores on all dimensions and three global indices on BSI between adolescents with and without substance use are shown in Table 3. Results demonstrated that adolescents with substance use had also Table 2. BSI scores for adolescents with or without Internet addiction

Internet addiction t Yes (n = 733) Mean⫾ SD No (n = 2784) Mean⫾ SD Somatization 0.80⫾ 0.82 0.51⫾ 0.60 8.93*** Obsessive–compulsive 1.43⫾ 0.83 1.14⫾ 0.74 8.62*** Interpersonal sensitivity 1.25⫾ 1.01 0.93⫾ 0.86 7.87*** Depression 1.07⫾ 0.99 0.68⫾ 0.80 9.79*** Anxiety 0.93⫾ 0.88 0.64⫾ 0.70 8.42*** Hostility 1.23⫾ 0.99 0.77⫾ 0.79 11.60*** Phobic anxiety 0.84⫾ 0.87 0.57⫾ 0.65 7.86*** Paranoid 1.09⫾ 0.89 0.76⫾ 0.71 9.37*** Psychoticism 0.89⫾ 0.86 0.55⫾ 0.66 10.01*** Additional items 0.87⫾ 0.87 0.51⫾ 0.64 10.40*** Global index

General severity index 1.04⫾ 0.78 0.71⫾ 0.60 10.70*** Positive symptom total 28.59⫾ 15.50 22.06⫾ 13.97 10.36*** Positive symptom distress index 1.80⫾ 0.64 1.58⫾ 0.55 8.50*** *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory.

Table 3. BSI scores for adolescents with or without substance use

Substance use experience

t Yes (n = 322) Mean⫾ SD No (n = 3195) Mean⫾ SD Somatization 0.88⫾ 0.92 0.54⫾ 0.62 6.55*** Obsessive–compulsive 1.39⫾ 0.86 1.18⫾ 0.75 4.27*** Interpersonal sensitivity 1.28⫾ 1.04 0.97⫾ 0.88 5.21*** Depression 1.18⫾ 1.07 0.72⫾ 0.82 7.42*** Anxiety 0.93⫾ 0.99 0.68⫾ 0.72 4.48*** Hostility 1.39⫾ 1.05 0.81⫾ 0.81 9.57*** Phobic anxiety 0.81⫾ 0.94 0.61⫾ 0.68 3.65*** Paranoid 1.18⫾ 0.96 0.79⫾ 0.74 7.01*** Psychoticism 0.92⫾ 0.98 0.59⫾ 0.68 5.96*** Additional items 0.94⫾ 0.96 0.55⫾ 0.66 7.16*** Global index

General severity index 1.10⫾ 0.87 0.74⫾ 0.62 7.22*** Positive symptom total 28.03⫾ 15.58 22.95⫾ 14.36 5.61*** Positive symptom distress index 1.91⫾ 0.71 1.60⫾ 0.55 7.58*** *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

higher scores on the GSI, PST, PSDI and all dimensions.

The association between psychiatric symptoms on the 10 dimensions of the BSI and Internet addiction was further examined using multiple logistic regres-sion (Table 4). Evaluation for collinearity showed that the condition index was 10.34 and thus accept-able to process regression analysis. The results indi-cated that adolescents with Internet addiction had higher level of hostility, depression, phobic anxiety, and additional symptoms, and a lower level of anxiety. But age was not significantly associated with Internet addiction.

The association between psychiatric symptoms on the 10 dimensional subscales of BSI and substance use was further examined using multiple logistic regression (Table 4). Results indicated that adoles-cents with substance experience were older and had higher hostility, more depression, greater somatiza-tion, less anxiety, and lower obsessive–compulsive behavior.

DISCUSSION

The present results show that adolescents with Inter-net addiction have more severe psychiatric symptoms than those without. This finding also corresponds to

analogous investigations of excessive Internet use in high schools.14,15We also found that adolescents with

substance use had more severe psychiatric symptoms than those without. Based on the Mueser et al. dis-cussion of comorbidity in substance use and other psychiatric disorders,23 we suggest four mechanisms

to account for the association between Internet addic-tion and psychiatric symptoms. First, psychiatric symptoms may lead to the onset or persistence of Internet addiction. Second, Internet addiction may precipitate psychiatric symptoms. Third, Internet addiction and psychiatric symptoms may increase vulnerability to each other. Finally, the shared risk factors, either genetic or environmental, lead to the onset or persistence of psychiatric symptoms and Internet addiction.

The Internet can provide social support,24

achieve-ment25 and pleasure of control,26 which provide

escape from emotional difficulty. Thus, adolescents with high-level psychiatric symptoms may utilize the Internet to cope with emotional distress. Without effective intervention for psychiatric symptoms, the use of the Internet might progress to addiction. In contrast, addiction to the Internet results in ineffec-tive coping and difficulty in real life.5Without

inter-vention for Internet addiction, the repeated negative consequences may cause further deterioration of Table 4. Logistic regression controlling for gender, age, and school

Internet addiction† Substance use experience‡

Wald c2 OR 95%CI Wald c2 OR 95%CI

Male 86.60*** 2.76 2.23–3.41 43.35*** 3.02 2.17–4.20 Junior high school§ 3.11 1.34 0.97–1.87 8.50** 2.04 1.26–3.30

Vocational high school§ 22.62*** 1.72 1.37–2.15 13.64*** 1.79 1.32–2.44

Age 2.04 1.07 0.98–1.18 12.43*** 1.27 1.11–1.45 Somatization 0.25 1.06 0.85–1.31 8.06** 1.52 1.14–2.03 Obsession-compulsion 0.03 0.98 0.82–1.18 11.74** 0.64 0.50–0.83 Interpersonal sensitivity 2.88 0.86 0.72–1.02 3.03 0.81 0.64–1.03 Depression 4.11* 1.21 1.01–1.46 13.02*** 1.58 1.23–2.03 Anxiety 3.97* 0.79 0.63–0.99 9.14** 0.61 0.44–0.84 Hostility 29.38*** 1.47 1.28–1.70 40.31*** 1.82 1.52–2.20 Phobic anxiety 6.04* 1.27 1.05–1.53 0.13 0.95 0.73–1.24 Paranoid 0.12 0.97 0.79–1.18 1.93 1.21 0.93–1.58 Psychoticism 0.58 1.09 0.88–1.35 0.44 0.91 0.67–1.22 Addition items 6.50* 1.32 1.07–1.64 3.84 1.34 1.00–1.80 *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

†Internet addiction, n = 733; control, n = 2784;‡substance use experience, n = 322; control, n = 3195. §Dummy variable for schools was senior high school.

psychiatric symptoms. Combining these two differ-ent views, Kraut et al. proposed a ‘rich get richer’ model whereby the Internet provides more benefits to those who are already well-adjusted.27By contrast,

poorly adjusted adolescents may suffer more delete-rious effects with heavy Internet use, creating a vicious circle. This bi-directional interaction between Internet addiction and psychiatric symptoms may produce mutual exacerbation, explaining the associa-tion. Lacking prospective studies, the association between psychiatric symptoms and Internet addic-tion cannot be validated by any one of the aforemen-tioned projected explanations; but the results suggest that psychiatric symptoms should be evaluated for adolescents with Internet addition.

From regression analysis, hostility was associated with Internet addiction and substance use in the present sample population. Previous reports have shown that hostility is an adolescent risk factor for smoking initiation,28early onset of alcoholism,29and

substance abuse.30Also, hostility has been reported to

predict escape-avoidance coping styles and substance use triggered by almost any cue, including negative emotional states and tension.31 Consequently, it

appears reasonable to assume that hostility may be a characteristic that predisposes the adolescent to coping with emotional stress by using escape-avoidance behavior, such as getting into virtual online activities. In contrast, adolescents who spend more time playing electronic games have been reported to have more hostility and be more predis-posed to acts of violence.32,33 Ko et al. reported that

75.6% of Internet addicts utilized the Internet to play online games.2Thus, the high engagement in violent

role-playing games by Internet addicts may partly account for the association with hostility. These results would suggest that adolescents with high hostility deserve more attention in the introduction of preventive strategies, and such hostility should be evaluated for Internet-addicted adolescents.

Depression has been reported to be associated with Internet addiction in an online survey.4 The present

results confirm this observation, and the significant association between Internet addiction and depres-sive symptoms may indicate that depression should be assessed in adolescents with Internet addiction. Logistic regression also demonstrated that high phobic anxiety is associated with Internet addiction. Because adolescents with phobic anxiety are reluctant to go out, the Internet provides them with a means of contacting others and engaging in game play without

exposure to phobic situations. However, this insular-ity may prevent them from coping with their prob-lems. But after control of other psychiatric symptoms, anxiety was negatively associated with both Internet addiction and substance experience. This result is dif-ferent to the present t-test results. It suggests that the association between Internet addiction and anxiety may be dependent on whether there is comorbidity with other psychiatric problems. However, further investigations to thoroughly survey the controversial association are necessary.

Older age was found to be associated with sub-stance use. This corresponds to previous reports.34,35

That the prohibition on legal or illicit substance use might decrease as age increased among adolescents, might partially explain the result. However, age was not associated with Internet addiction. Because the Internet was perceived as a learning tool for adoles-cents, most adolescents in Taiwan are permitted to use the Internet from primary school onwards. Also, because of the anonymity of the Internet, adoles-cents’ online behavior would not be prohibited according to their age. Thus, the impact of age on Internet addiction of adolescents might be limited.

The present results demonstrate that adolescents with Internet addiction have higher psychiatric symp-toms on all 10 dimensions on the BSI as well as in those items concerning substance use. In logistic regression analysis, hostility and depression were associated with Internet addiction as well as sub-stance use. Depression has been reported to be a shared compromising outcome of all problem behav-ior in adolescents.8 Also, other behavior problems,

such as delinquency and risky driving, have been reported to be associated with hostility.36,37 The

results suggest that adolescents with Internet addic-tion have poor outcomes for mental health, as do those who have other problem behaviors. This con-clusion supports the hypothesis that Internet addic-tion might well be included in the organizaaddic-tion of problem behavior as defined by problem behavior theory. If this hypothesis could be verified in further studies, Internet addiction should be one of the focuses for preventive strategies for organization of problem behavior.

The present results should be interpreted in the light of three limitations. First, social restrictions on substance use may make adolescents unwilling to admit substance use even in anonymous question-naires. Thus, participants with substance use may be underestimated. Second, the present cross-sectional

research design could not confirm causal relation-ships between Internet addiction and various psychi-atric symptoms. Thus, the association results should be further evaluated in prospective research to dem-onstrate the causal relationship between psychiatric symptoms and Internet addiction and substance use. Third, lacking information from other investigators, the assessment of Internet addiction was based only on the self-reported perspective of adolescents. If the participants denied or could not estimate their mal-adaptive Internet use, the Internet addiction would be underestimated.

CONCLUSION

This present study has demonstrated that adoles-cents with Internet addiction had poor outcome for mental health, as did those with substance use. This result partially supports the hypothesis that Internet addiction is one of the problem behaviors of ado-lescence as defined by problem behavior theory. Furthermore, hostility and depression were evalu-ated to be associevalu-ated with Internet addiction in the present adolescent sample population. Accordingly, more attention should be devoted to hostile and depressed adolescents in the design of preventive strategies and related therapeutic interventions for Internet addiction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 92-2413-H-037-005 SSS).

REFERENCES

1 Young KS. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new

clini-cal disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998; 1: 237–244.

2 Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Yen CF. Proposed

diagnostic criteria of Internet addiction for adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005; 193: 728–733.

3 Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF, Chen CC, Yen CN, Chen SH.

Screen-ing for Internet addiction: An empirical research on cut-off points for the Chen Internet Addiction Scale. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2005; 21: 545–551.

4 Young KS, Rogers RC. The relationship between depression

and Internet addiction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998; 1: 25–28.

5 Lin SSJ, Tsai CC. Sensation seeking and Internet dependence

of Taiwanese high school adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002; 18: 411–426.

6 Ryu EJ, Choi KS, Seo JS, Nam BW. The relationships of

Internet addiction, depression, and suicidal ideation in ado

lescents. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi 2004; 34: 102–110 (in Korean).

7

Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Wu K, Yen CF. Tridi-mensional personality of adolescents with Internet addic-tion and substance use experience. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006;

51: 887–894.

8 Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial

framework for understanding and action. J. Adolesc. Health 1991; 12: 597–605.

9 Yen JY, Yen CF, Chen CC, Chen SH, Ko CH. Family factors

of Internet addiction and substance use experience in Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007; 10: 323– 329.

10 Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Yen CF. Gender

differ-ences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005; 193: 273–277.

11 Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. Substance use

problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among ado-lescents in primary care. Pediatrics 2003; 111: e699–e705.

12 Chinet L, Plancherel B, Bolognini M et al. Substance use and

depression. Comparative course in adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006; 15: 149–155.

13 Yoo HJ, Cho SC, Ha J et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity

symptoms and Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004; 58: 487–494.

14 Yang CK. Sociopsychiatric characteristics of adolescents who

use computers to excess. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001; 104: 217–222.

15 Yang CK, Choe BM, Baity M, Lee JH, Cho JS. SCL-90-R and

16PF profiles of senior high school students with excessive Internet use. Can. J. Psychiatry 2005; 50: 407–414.

16 Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory:

An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983; 13: 595–605.

17 Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R, Administration, Scoring and

Proce-dures Manual 1. Clinical Psychometric Research, Baltimore, MD, 1977.

18 Chen SH, Weng LC, Su YJ, Wu HM, Yang PF. Development

of Chinese Internet Addiction Scale and its psychometric study. Chin. J. Psychol. 2003; 45: 279–294 (in Chinese).

19 Yen CF, Yang YH, Ko CH, Yen JY. Substance initiation

sequences among Taiwanese adolescents using metham-phetamine. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005; 59: 683–689.

20

Bauman A, Phongsavan P. Epidemiology of substance use in adolescence: Prevalence, trends and policy implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999; 55: 187–207.

21 Agrawal A, Madden PA, Heath AC, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK,

Martin NG. Correlates of regular cigarette smoking in a population-based sample of Australian twins. Addiction 2005; 100: 1709–1719.

22 Easton A, Kiss E. Covariates of current cigarette smoking

among secondary school students in Budapest, Hungary, 1999. Health Educ. Res. 2005; 20: 92–100.

23 Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Dual diagnosis: A review

24

Tichon JG, Shapiro M. The process of sharing social support in cyberspace. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2003; 6: 161–170.

25

Suler JR. To get what you need: Healthy and pathological Internet use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1999; 2: 385–393.

26 Leung L. Net-generation attributes and seductive properties

of the Internet as predictors of online activities and Internet addiction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004; 7: 333–348.

27 Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, Cummings J, Helgeson V,

Crawford A. Internet paradox revisited. J. Soc. Issues 2002;

58: 49–74.

28 Weiss JW, Mouttapa M, Chou CP et al. Hostility, depressive

symptoms, and smoking in early adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2005; 28: 49–62.

29 Dom G, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Differences in impulsivity and

sensation seeking between early- and late-onset alcoholics. Addict. Behav. 2006; 31: 298–308.

30 Patel DR, Greydanus DE. Substance abuse: A pediatric

concern. Indian J. Pediatr. 1999; 66: 557–567.

31 McCormick RA, Smith M. Aggression and hostility in

sub-stance abusers: The relationship to abuse patterns, coping

style, and relapse triggers. Addict. Behav. 1995; 20: 555– 562.

32

Gentile DA, Lynch PJ, Linder JR, Walsh DA. The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. J. Adolesc. 2004; 27: 5–22.

33 Kuntsche EN. Hostility among adolescents in Switzerland?

Multivariate relations between excessive media use and forms of violence. J. Adolesc. Health 2004; 34: 230–236.

34 Donovan JE. Adolescent alcohol initiation: A review of

psychosocial risk factors. J. Adolesc. Health 2004; 35: 529.

35 Sutherland I, Shepherd JP. The prevalence of alcohol,

ciga-rette and illicit drug use in a stratified sample of English adolescents. Addiction 2001; 96: 637–640.

36 Patil SM, Shope JT, Raghunathan TE, Bingham CR. The role

of personality characteristics in young adult driving. Traffic. Inj. Prev. 2006; 7: 328–334.

37 Swickard DL, Spilka B. Hostility expression among

delin-quents of minority and majority groups. J. Consult. Psychol. 1961; 25: 216–220.