台灣大學生拒絕行為之中介語研究

全文

(2) ABSTRACT This study investigates interlanguage and its motivating factors within the speech act of refusals by Chinese learners of English. Defined as an acquisitional interim between the native and target languages (Odlin, 1989), interlanguage has been proven distinctive in the act of refusals in terms of the frequency, order, and content of meaning patterns (e.g. Beebe et al. 1990; Gass & Houck 1999). Nevertheless little is known about the pragmatic and sociocultural performances of interlanguage in English refusals made by Chinese students. Questionnaires of Discourse Completion Test were designed to elicit imaginary noncompliance toward two demanding part-time jobs. 266 English refusals were solicited from English majors in three Taiwan universities. A qualitative analysis shows that the interlanguage refusals produced by Chinese students exhibit interlanguage distinctiveness in aspects of quantity, order, and length of refusal semantic formulas. The most frequently adopted formulas are Excuse, Regret, and Conventional nonperformative, forming the prevalent orders of Excuse - Regret and Excuse - Conventional nonperformative – Regret. Indulgence in External modification leads to lengthy responses and was used to compensate for the ossified operation of Epistemic and Dynamic modalities as Internal modification. These interlanguage features converge onto the first language and the learning context as contributing factors arising from positive and negative transfer and instructional effects in an EFL context. A proposal of developing communicative competence in foreign language learning is thus suggested by equipping Chinese students with the pragmatic and sociocultural knowledge. In doing this, this thesis brings both EFL learners and instructors’ attention further to the interpersonal meanings in the speech act communication.. i.

(3) 中文摘要 本論文研究台灣學生以英語回應之拒絕行為,主要探討台灣學生的英語中介 語及其背後可能的形成原因。中介語指語言習得過程中一過渡階段(Odlin, 1989) ,在以英語拒絕的中介語實證研究中,文獻指出學習者在表達拒絕意涵時, 其頻率、語序與內容上皆顯現獨特性(Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Gass & Houck, 1999)。然而,在中介語的實證研究中,卻少有以漢語為母語的 英語學習對象,探究其行使拒絕此言語行為時的語用與社會文化表現。本論文因 此以問卷的形式,設計「篇章完成測驗」以引出實驗參與者在拒絕請求時的英語 回應。實驗參與者來自台灣三所大學的 134 位大學生。問卷設計包含兩個情境, 要求參與實驗的大學生,想像一位研究助理打電話詢問他們是否願意接受兩份工 讀的工作,但在得知其繁重的工作內容後,想予以拒絕。 根據質性的分析,台灣學生的拒絕行為中介語,在拒絕語意公式的數量、語 序與長度三方面,皆顯現獨特的語用與社會文化特徵。數量上使用最多的語意公 式為「藉口」、「道歉」、「傳統非使願詞」,也因此造成語序排列上的偏好, 如「藉口 -- 道歉 -- 傳統非使願詞」。回應的長度明顯偏長,主要原因在於學 生過度使用具有非核心拒絕意涵的語意公式當作「外部修飾」。反而其「內部修 飾」的使用較為僵化,多出現認知情態詞,如“可能"、“我想"、“也許", 與動力情態詞,如“不行"、“沒辦法"等。 本論文探討其兩大可能影響因素:學習者的母語與學習環境,發現此兩因素 對學習者的中介語語用與社會文化表現有極大的影響。母語可能帶來正向與負向 的移轉作用。正向移轉發生在學習者的母語與目標語有相同性時,如國語與英語 的拒絕行為皆常使用「藉口」、「道歉」與認知、動力情態詞;負向移轉則可能 發生在兩語言的差異處,如台灣學生傾向以迴避或給予其他選擇為拒絕的語用策 略,但這些卻非英語母語人士習慣的回應方式。其次,學習的環境並非著重溝通 的第二外語環境,而是重視機械化練習文法結構與單字的外語填壓教育,因此可 能誤導學生在以英語拒絕時,只能僵化地使用部分語用策略,並過度以語意公式 的增加減緩拒絕的強度,卻反而造成語用失當或語意不清的反效果。本論文因此 藉以提出實際可行的教學建議,分為四項教學四步驟:提升學生的語用策略與文 化差異知覺、使學生自然習得慣用的語用策略、練習溝通式的產出、給學生機會 互相分享心得。本文的研究結果,期能讓台灣的英語教學工作者更注重學生語用 與社會文化溝通能力的發展,著重設計具有溝通目標的語言課程,讓學生在英語 的溝通能力上更上一層樓。. ii.

(4) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deepest gratitude is extended to my advisor, Dr. Chia-Ling Hsieh who has always been a motivator, an instructor, and a good friend throughout my Master research. She motivated me in times of despair, guided me in times of confusion, and offered guidance in times of chaos. Without her support and enlightenment, it would not have been possible for me to complete this interlanguage study, especially when the analysis of the results and the construction of the ideas baffled me. My thanks also go to my committee members: Dr. Posen Liao from National Taipei University and Dr. Stephanie W Cheng from National Chiao Tung University who both gave me invaluable comments on this study and helpful suggestions throughout the development of the research. I am also indebted to all the excellent professors in the Institute of TESOL in National Chiao Tung University for the training of my academic acuteness and the discovery of my research interest. A very special note of appreciation is directed toward the lecturer, Linda Wu from the Language Teaching and Research Center for helping me collecting my data. Finally I would like to express my gratitude toward my sincere families and friends for their encouragement and support. The love of my parents equips me with power and confidence to face all the difficulties, particularly when I need to worry about my part-time job and on-going research at the same time. I am also thankful to Dawson for his understanding and help; to my dear classmates, Clarence, Sandra, Claire, Livia, and Eric for their valuable opinions and ceaseless encouragement. I dedicate this work to all of them.. iii.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................. I 中文摘要.......................................................................................................................II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................... III TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... IV LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................1 BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATIONS..........................................................1 PURPOSES ..........................................................................................................4 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY...................................................................4 ORGANIZATION OF THE THESIS ...............................................................5. CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW....................................................................6 SPEECH ACT THEORY ...................................................................................6 Issue 1: Pragmatic Aspect. ..........................................................................6 Issue 2: Sociolinguistic Aspect ....................................................................9 INTERLANGUAGE PRAGMATICS ...........................................................11 Types of Studies on Interlanguage Pragmatics .......................................12 Use and Developmental Transfer .............................................................15 The Factor of Language Proficiency ........................................................19 The Factor of Learning Context...............................................................22 INTERLANGUAGE PRAGMATICS OF THE SPEECH ACT OF REFUSALS ........................................................................................................24 Issue 1: Speech Act Aspect ........................................................................24 Issue 2: Interlanguage Aspect ...................................................................25. CHAPTER 3 METHOD............................................................................................27 SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS ................................................................27 INSTRUMENTS................................................................................................27 PROCEDURES .................................................................................................31 DATA ANALYSIS ............................................................................................31 iv.

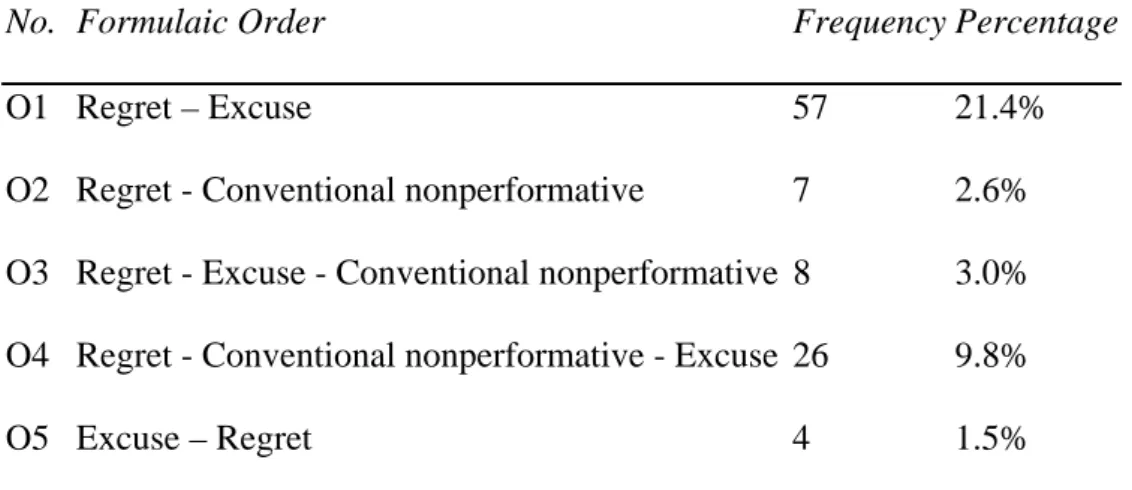

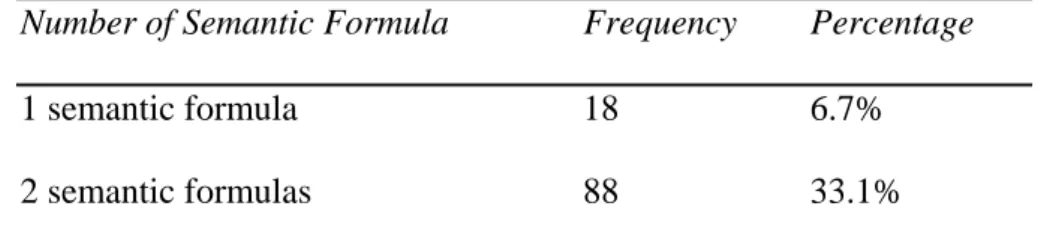

(6) CHAPTER 4 RESULTS............................................................................................32 THE USE OF SEMANTIC FORMULA .........................................................32 The Quantity Aspect ..................................................................................32 The Order Aspect.......................................................................................42 The Length Aspect .....................................................................................46 THE USE OF MODIFICATION.....................................................................50 External and Internal Modification .........................................................51 Modal Use in Internal Modification.........................................................54. CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS ...........................................60 THE INFLUENCE OF NATIVE LANGUAGE.............................................60 Positive Transfer ........................................................................................60 Negative Transfer.......................................................................................65 THE INFLUENCE OF LEARNING CONTEXT ..........................................69 Pragmatic Inadequacy...............................................................................70 Linguistic Ossification ...............................................................................72 Formulaic Repeatability............................................................................74 SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS ....................................................................76 APPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY ................................................................77 SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ...........................................80. APPENDIX A: DISCOURSE COMPLETION TEST ...........................................81 APPENDIX B: SUMMARY TABLE OF THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PARTICIPANTS........................................................................................................83. REFERENCES...........................................................................................................84. v.

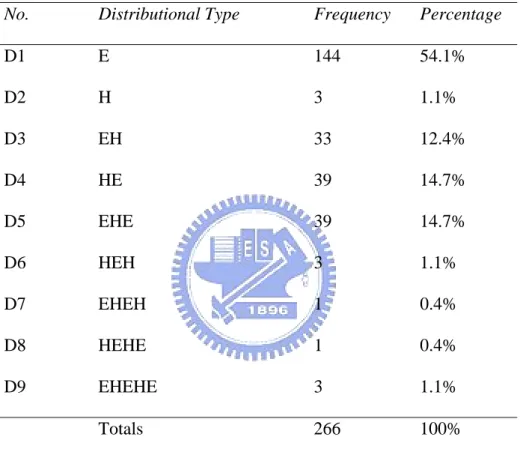

(7) LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Occurring Frequency of semantic formula used by Chinese students...........33 Table 2 : Occurring Frequency of formulaic orders used by Chinese students ...........42 Table 3 : Occurring Frequency of the number of semantic formulas in one response 47 Table 4 : Occurring Frequency of distributional type of external modification and head act ........................................................................................................51 Table 5 : Occurring Frequency of internal modification across semantic formulas....54. vi.

(8) 1. CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATIONS Communication competence is regarded significant in the second language learning process. Without this competence second language speakers are unable to accomplish successful second language communication. A number of studies have verified that pragmatic and sociocultural competence 1 constitute two essential elements in learners’ communicative capabilities (e.g., Liao & Bresnahan, 1996; Hassall, 2001; Nelson, Carson, Batal & Bakary, 2002; Byon, 2004). With pragmatic competence, second language speakers can manipulate pragmatic strategies such as indirectness, routines, and plenty of linguistic forms to achieve the intended pragmatic end and politeness values (Leech, 1983; Thomas, 1983). For example, one says “The kitchen seems to be in a bit of a mess.” to his roommate as a pragmatic convention as a request for cleaning the kitchen (for the conventionality in indirectness, see Blum-Kulka, 1989). With regard to sociocultural competence, it enables speakers to conform to certain social principles governing the interpretation and performance of the communicative action by speakers of the target language (Leech, 1983). This can be evident in Igbo culture that people all learn to utter a direct request such as “I want to work with your cutlass/hoe today” within a social system of mutual sharing, which however could be regarded rude and impolite in other cultures. The significance of the two abilities in second language learning was therefore proposed by Wolfson (1989).. 1. For ease of exposition, the ‘pragmatic’ and ‘sociocultural’ perspecctives mentioned in this thesis corresponds to the distinction between ‘pragmalinguistic’ and ‘sociopragmatic’ transfer termed by Kasper (1992). ..

(9) 2. She addressed that better control of the pragmatic and sociocultural parameters can make second language speakers effective in second language interpersonal interaction. Speech act communication requires speakers to comprehend or produce three levels of meaning to complete the negotiating process. The three levels include the ‘locutionary act’ (i.e., the literal meaning conveyed by the actual words), ‘illocutionary act’ (i.e., the intended meaning related to the utterance explicitly or implicitly), and ‘perlocutionary act’ (i.e., the effect that the illocutionary act imposes on the hearer) (Austin, 1962). For instance, if the locutionary sentence “It’s hot in here!” carries the illocutionary meaning “I want some fresh air!”, the perlocutionary result might be that the hearer opens the window (For more examples, see Thomas, 1995). To put it differently, the speech act communication succeeds only when the speaker’s intention is comprehensively understood and attained by the listener in the interaction flow. Previous studies have demonstrated that successful performance of speech acts is anchored upon sufficient pragmatic competence (e.g., Paulston, 1974; Canale and Swain, 1980). However the pragmatic operation may be specific to different cultures. It is to this end that this study attaches itself to examine the pragmatic performance in interlanguage under the English context. The study of interlanguage pragmatics as defined in a narrow sense refers to nonnative speakers’ comprehension and production of speech acts, and how their second-language-related speech act knowledge is acquired (Kasper, 1992; Kasper & Dahl, 1991). Invariably focusing on the nonnative speakers, it pays much attention to second language learners’ pragmatic and sociocultural performance with reference to various speech acts (Bardovi-Harlig, 1999, for review), especially those face-threatening acts (FTA) (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 65). Brown and Levinson.

(10) 3. proposed that when speakers have to conduct face-threatening speech acts such as requests, compliments, guarantees, oppositions and criticism (pp. 65-68), they would opt for strategies for positive or negative politeness to alleviate the damage to the interlocutor’s face. Positive politeness tends toward the protection of the listener’s positive self-image (i.e, positive face) while negative politeness toward the satisfactory of his basic need of free will (i.e, negative face) (p. 70). Faced with the concomitant needs of reaching the intended illocutionary force and of obeying the social norm of politeness, nonnative performers of such FTAs would very likely encounter great challenges on their pragmatic and sociocultural competence. Considering this latent obstacles for foreign language learners, the bulk of interlanguage pragmatics research dedicates itself to learners’ performance on divergent FTAs, such as refusals (e.g., Takahashi & Beebe, 1987; Gass & Houck, 1999; Nelson, Carson, Batal & Bakary, 2002; Al-Issa, 2003), requests (e.g., Schmidt, 1983; Trogsborg, 1995; Yu, 1999; Rose, 2000), compliments (e.g., Yu, 2004), and suggestions (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 1990). These studies all give prominence to both the pragmatic and sociocultural abilities with regard to the speech act behaviors. The speech act to be examined in this study, refusals in response to requests, also belongs to what Brown and Levinson (1978) termed ‘face-threatening acts’ for its performance potentially clashes with the face wants of the requester. A number of scholars (e.g., Shih, 1986; Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford, 1991; Liao & Bresnahan, 1996; Turnbull & Saxton, 1997; Nelson, Carson & Bakary, 2002; Hsieh, Chen & Hu, 2004) have confirmed that refusals embody an effort on the part of the refuser to apply socially approvable strategies for restoration of his or the requester’s face. Accordingly, the pragmatic tactics in aligned to the social and cultural expectation are the key factors to foreign language communication..

(11) 4. PURPOSES In order to assist Chinese learners of English in acquiring the pragmatic and sociocultural abilities and English teachers in developing effective instruction for speech act communication, second language scholars need to grasp the course of learners’ speech act development as to how they apply linguistic maneuvers to convey interpersonal meanings. Among the work of refusals, few were aimed at learners who speak Mandarin Chinese as their native language. Therefore, this thesis will qualitatively explore the interlanguage refusals produced by Chinese learners of English in particular on the pragmatic and sociocultural perspectives. The purposes of the thesis are three-fold:. (1) To uncover the pragmatic characteristics of the interlanguage refusals by Chinese learners of English in response to a request? (2) To explore how the influential factors of learners’ native language and learning contexts motivate their pragmatic use in the act of refusal, and to scrutinize to what extent the two factors are responsible for learners’ nonnative pragmatic use. (3) To apply the interlanguage findings to the speech act pedagogy by proposing a teaching approach.. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY It is believed that the actual performance of language learners serve as the foundation for TESOL theory and practice. The interlanguage data can not only be used to test the truth of the interlanguage hypothesis, but also aid English instructors in accurately predicting possible bottlenecks that Chinese learners may be faced with. In addition, the application of the empirical data also paves the pedagogical way for.

(12) 5. TESOL colleagues in that they can be familiarized with where in sociocultural forests Chinese learners may lose their direction.. ORGANIZATION OF THE THESIS This thesis includes six chapters. The first chapter sketches out the background of this research. The second chapter reviews the literature of speech act theory and interlanguage pragmatics, both of which bring out the necessity to empirically investigate Chinese learners’ interlanguage refusals as well as its motivating factors. In the third chapter, we put forward the design of the experiment by describing the participants, instrument and data analysis. The forth chapter outlines the qualitative results of interlanguage analysis with reference to the units of semantic formulas and the use of modal mitigators. For a comprehensive understanding, the factors that mainly contribute to the Chinese students’ interlanguage performance are advocated in chapter five. Finally, the practical applications and conclusion remarks are presented in chapter six..

(13) 6. CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. SPEECH ACT THEORY Speech Act Theory (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1995) has been developed extensively in recent years and has given rise to various studies in a wide spectrum of disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, pragmatics and sociolinguistics. Pragmatic and sociolinguistic approaches to studying speech acts among these disciplines especially arouse great interest in the second language acquisition profession. Pragmatic research has made a major contribution in viewing language as action (i.e., defined as the level of illocutionary force) and has explained language through actual use. The sociolinguistic approach has pursued the question of whether a language action is realized in terms of social appropriateness. Pragmatic and sociolinguistic aspects of speech act studies will be briefly introduced in the foregoing sections.. Issue 1: Pragmatic Aspect. As a widely-discussed domain in second language research, studies on speech act with respect to pragmatic aspects can be divided into three components: within one specific language (e.g., Blum-Kulka, 1987; Koike, 1989b; Turnbull & Saxton, 1997), between two or more languages (e.g., Chen, 1993; Lee-Wong, 1994; Fukushima, 1996; Liao & Bresnahan, 1996; Pair, 1996; Nelson, Carson, Batal & Bakary, 2002), and between languages produced by native and non-native speakers (e.g., Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Yu, 1999, 2004; Hassall, 2001, 2003; Byon, 2004). No matter within what language scope, these studies have disclosed diversified manipulations of strategies in favor of the perlocutionary effect of.

(14) 7. facework in the type of speech acts that intrinsically threaten interlocutors’ face. Studies on speech acts within one specific language mostly investigate how the use of linguistic strategies or devices is called for assisting the completion of speech acts. Koike (1989b) examined two request strategies produced by native Portuguese speakers from Brazil: the conditional mood and second-person reference. Results showed that the greater the distance from the deictic center is, in temporal or personal dimensions, the greater degree of politeness and the lesser degree of illocutionary force are. To put it in detail, the use of conditional forms in polite requests expresses the time frame farthest from the speakers’ present moment of speaking. By the same token, second-person reference or hearer-oriented utterances (e.g., “Would you/Could you do X?”) are more polite than speaker-oriented ones with first-person reference (e.g., “I would like you to do X.”). This is because the framing of the request shifts from the point of view of the speaker to that of the hearer, giving greater control to the hearer in the interaction process and making one step closer to the end of politeness. Hong (1996) analyzed Chinese native speakers’ request behavior under three imaginary situations in an open-ended questionnaire: (1) a patient wanted to have the prescription refilled because it worked very well previously; (2) one borrowed money from his/her office-mate to buy snack at a nearby store; (3) a police officer asked the civilian on the street to remove his/her car. Results presented the influence of the parameters of dominance and social distance on the choice of request strategies. For instance, when interacting with authority figures speakers would apply supportive moves (e.g., yisheng, qing nin zai gei we kai yi zhang yaofang, shangci de yao heng hao yong “Doctor, could you please write me another prescription, because it worked very well last time.”), make requests longer, and use addresses denoting respect and politeness (e.g., use of nin “you”). As to social distance, speakers tend to deposit.

(15) 8. pregrounders, such as compliments on the interlocutor or the reason why this request has been made, in order to alleviate the threatening force of the act. Some other studies compare speech acts between distinct languages, discovering similarities and variation in how the illocutionary force is expressed. Tseng (1999) used the open role play technique to elicit invitational conversations from 40 Chinese undergraduates in Taiwan and 40 American undergraduates in the U.S. Dissimilar to the stereotype that Chinese preferred tripartite structures and American favored a single structure in invitational conversations, Tseng’s study demonstrated that the Chi-square test of independence did not show significant difference in the occurrence of both structures in the two languages at issue. The only cross-linguistic contrast found was that under the situation of less familiarity between interlocutors, Chinese had the preference for the tripartite structure whereas Americans for the single one. On the assumption that cultural variations such as the discrepancies of mechanisms in speech acts may pose formidable obstacles for language learners, studies observing native and non-native speakers’ production constitute another research area. As a recent discussion of the speech act of request, Byon (2004) compared the utterances of requests produced by Korean and American English native speakers as well as English speakers of Korean, illustrating evident cultural effects. A salient one was that the native English speakers and American learners of Korean differed from native Korean speakers in the use of apology within requests. They adopted expressions of apology in their requesting utterances to implore forgiveness for one’s faults, yet native Korean speakers simply convey the sense of being polite. Another salient cultural effect was concerned with the Korean learners’ preference for ‘indirect requesting head act’ formula, which may derive from politeness in western cultures and relate to ‘negative politeness’ (Brown and Levinson, 1978, pp. 129-227)..

(16) 9. In the three types of speech act studies mentioned above, pragmatic aspect is given a prominent role as a necessity that facilitates meaningful, cohesive and effective interaction with others. More work in this aspect of speech acts is thus worth-pursuing.. Issue 2: Sociolinguistic Aspect When it comes to socio-cultural aspects of speech act studies, the issue of universality versus culture-specificity has been the central concern. The notion of universality was advocated by Brown and Levinson (1978), addressing that almost all languages and cultures operate along the line of protecting one’s positive and negative face. In other words, speakers need to protect listeners’ negative face (i.e., ‘the want of every ‘competent adult member’ that his actions be unimpeded by others’) as well as to defend his positive face (i.e., ‘the want of every member that his wants be desirable to at least some others’) (p. 62). However, a large number of opposing views have been constantly advocated to reveal the invalidity of Brown and Levinson’s assumption of universality (see Gu, 1990; Nwoye, 1992). It has even been argued that the presumption of any universality is no more than subjective, ethnocentric Anglo-Saxton perspectives (Wierzbicka, 1991). For example, Gu (1990) found this universal model unsuitable for Chinese culture. He critiqued that Chinese realization of negative face want is different from what Brown and Levinson depicts. In addition, Chinese more frequently realize the notion of politeness in terms of a normative view, thinking highly of a communal harmony in interaction. Another evidence for anti-universality is Ma’s (1996) proposal of ‘contrary-to-face-value communication’, by which Chinese exhibit their rules of saying “yes” for “no” and “no” for “yes”. For example, to avoid conflicts,.

(17) 10. Chinese would abandon a direct rejection but resort to an ambiguous “yes” such as “I understand your position.” and “I am listening to you.” In another situation that the guests complimented the host for the food prepared, the Chinese host would adopt a saying “no” for “yes” rule since a response of accepting the compliment may imply that the guest should recognize the time the host had spent in preparing the food. As noted by Ma, Chinese interact with others in an attempt to ‘avoid direct confrontation and maintain social harmony’. Also opposed to Brown and Levinson’s universal politeness, Nwoye’s (1992) study on linguistic politeness and socio-cultural variations of the notion of face expounded the imposition in Igbo society in Nigeria. In fact, few speech acts would be regarded impolite in Igbo society, where collectivism or group orientation is the norm and everyone within the society may need others’ assistance some day. Request was an act inherently not face-threatening at all in Igbo society in that this community was built on people’s sharing of food or goods. Offering did not constitute a face-threatening speech act, either, due to the collaborative principle executed in Igbo society. Reflecting that linguistic politeness is closely woven within the fabric of social values, Nwoye’s (1992) study again addressed the uniqueness of linguistic behaviors to a specific culture. The following discussion will turn to speech act studies that also throw light onto the socio-cultural aspect. Lee-Wong’s (1994) and Fukushima’s (1996) studies both verified that the influence of culture on the act of request is self-evident when impositives are considered socially appropriate in some cultures and societies. Lee-Wong’s (1994) came to the conclusion that ‘bald-on-record direct strategy’ (Brown and Levinson, 1978, pp. 94-101) such as imperatives containing action verbs (e.g., Qing ba xiangzi dakai, women yao jiancha “Please open the suitcase, we want to check.”) is the most preferred strategy in Chinese act of request. Identically,.

(18) 11. Fukushima’s (1996) discovered plenty of imperative uses and direct requests in Japanese act of request. It is cultural values that tolerate the use of imposition in both Chinese and Japanese cultures. In Chinese, the concepts of sincerity and solidarity make the speaker believes that the listener would not mind doing anything for him, while in Japanese, the in-group unity and identification foster their belief that requests imply closeness and intimacy. Still another one addressing socio-cultural implications was conducted by Pair (1996), studying the speech act of request made by native Spanish speakers and Dutch speakers speaking Spanish. This study revealed that the conventionally indirect strategy in Dutch sounds like an implication of anger or unhappiness when it is used to query about why the addressee did not want to do the requested act. Therefore, the nonnative speakers of Spanish from Holland were prone to inhibit such inquiry use. This again gave proof that nonnative speakers have the inclination to rely on the pragmatic principles in their native language. These anti-universality studies provide a theoretical framework for more cross-cultural analyses concerning speech acts.. INTERLANGUAGE PRAGMATICS Second language learners normally spend quite a period of time to reach target-language-like fluency. Regardless of any formal instruction, they generally undergo the process of making attempts to test the hypothesis of the target language. They may employ the knowledge of their first language or start with their realization about language in general, from which bit by bit a mental frame of the target language will be established to achieve communicative competency. This interim phase of language learning is identified as the ‘interlanguage continuum’ (Selinker, 1972), where differences from the target language use are not considered as serious errors or.

(19) 12. interference of the mother tongue (Hamilton, 2001). In effect, learners’ interlanguage can be detected in various cores of language, such as syntax, phonology, morphology, and semantics (Kasper and Rose, 2002). Some characteristics of learning pragmatics are partly on par with learning other compartments of languages (for detail, please refer to Gass and Houck, 1999) and it is these characteristics of interlanguage pragmatics will be focused in the remainder of this section.. Types of Studies on Interlanguage Pragmatics As far as research development, work on learning development has been the most arresting researching area in interlanguage pragmatics (ILP) since second language use and learning have received much attention among scholars. However, its focal object has long been given to pragmatic performance rather than the development of interlanguage (Kasper & Schmidt, 1996; Rose, 2000; Kasper & Rose, 2002). A brief introduction of second language performance as well as development studies up to date will be outlined in order. First, treatises on second language use or performance approach how non-native speakers produce and comprehend language action in L2. In effect, most of these studies cast emphasis upon the production part though there is a modicum of work examining learners’ judgment and comprehension (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). Two famous studies on the investigation of second language learners’ production were carried out by Takahashi and Beebe (1987) and Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz (1990). The former recruited four groups of participants: Japanese speaking Japanese in Japan (JJJ), Japanese learners of English in Japan (JEJ), Japanese speakers of English in the U.S. (JEA), and American native speakers of English (AEA) to take part in a Discourse Completion Test (DCT), a test that solicited refusals in response to.

(20) 13. requests, invitations, offers and suggestions. Results showed that JEJ resembled JJJ in the sequence of refusal semantic formula. For instance, all Japanese learners of English would begin with an empathy or expression of regret/apologies, followed by a statement of philosophy (e.g., Things with shapes eventually break. To err is human.) and an attempt to make the interlocutor off the hook (e.g., You can forget about it.). A sequential resemblance found by Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz (1990) was that both Japanese speaking Japanese and Japanese speaking English frequently used expressions of regret/apologies as a starter especially with higher-status interlocutors. A conclusion of L1 transfer was consequently drawn to explicate the above L2 production akin to speakers’ L1. Less as work on learners’ second language comprehension is, there are indeed some contributive studies demonstrating the dissimilarities between non-native and native speakers’ judgment and perception (see Bardovi-Harlig, 2001 for reference). Bergman and Kasper (1993) directed a study on L2 learners’ perception of English apologies. An assessment task was performed by 423 Thai graduate students and 30 native American English students to rate four context-internal factors (i.e., severity of offense, obligation to apologize, likelihood of acceptance of apology, and offenders’ loss of face). It was reported that Thai learners and native American English speakers differed in their ratings of the obligation to apologize. Native speakers rated this factor even higher. On the whole, two groups of speakers were shown to establish a high correlation between (1) obligation to apologize and severity of offense, (2) between severity and likelihood of acceptance, (3) between severity and face-loss, and (4) obligation and face-loss. Rather than a pure perception study of certain speech acts, Bardovi-Harlig and Dörnyei (1998) investigated the extent to which EFL as well as their teachers and ESL learners of English showed awareness of pragmatic and.

(21) 14. grammatical errors. Results indicated that ESL learners rated pragmatic errors more serious than EFL learners and teachers did. Learners and instructors under an EFL context tend to be more alert to grammatical errors and to give more serious rating in grammatically aberrant performance. Research into pragmatic comprehension and judgment competence convincingly demonstrate that the importance of such ability should be recognized. The second type of ILP literature concerning second language development also contains the dimensions of production as well as comprehension, in particular associating with L2 learners’ developmental continuum rather than L2 use only (e.g., Carrell, 1981; Bouton, 1988, 1994; Koike 1996). The research that will be discussed here includes Carrell’s (1981) early attempt to discern the difficulties in learners’ comprehension of English requests, and Koike’s (1996) study on the comprehension competence in the Spanish act of suggestion. The former study inspected whether there were any comprehension difficulties in a hierarchical manner in English indirect requests. Subjects of this study involved university students of four levels: low-intermediate, intermediate, high-intermediate and advanced, who were all able to interpret request forms such as “Please color the circle blue.” and “I would love to see the circle colored blue.” However, those with more complex syntactical structures such as interrogatives forms (e.g., “Must you make the circle blue?”) and negatives (e.g., “You shouldn’t color the circle blue.”) imposed more difficulties especially upon the lower-proficiency learners. Turning the target language from English to Spanish as a second language, the study conducted by Koike (1996) inquired into how university students (i.e., first, second, and third year students) comprehended Spanish suggestions. Students were asked to watch a monologue video tape recorded by native Spanish speakers and tried to recognize the illocutionary act under examination..

(22) 15. Certain phrases denoting speech acts, such as por favor “please” and no tengo dinero “I don’t have any money”, were adopted by third-year students. This detection insinuated that learners of a higher level started to possess the form-function mapping ability in the process of interpreting speech acts. From the literature cited in this section, a full view of interlanguage pragmatics contributes to our understanding of this complicated yet significant research area. In the proceeding sections, the issues of use and developmental transfer as well as influential factors in interlanguage will be elaborated respectively.. Use and Developmental Transfer As for the definition of pragmatic transfer, there still seems no common consensus among scholars owing to the perplexed relationship between pragmatics and sociolinguistics (Kasper, 1992). Odlin (1989) began with what transfer is not in light of second language acquisition research in the past. First, ‘transfer is not simply a consequence of habit formation’, as he asserted that language transferring is more a cognitive psychological process than a behavioral act. Second, ‘transfer is not simply interference’ since not all influences of the native language cause critical mistakes, specifically when there are relatively few differences between the two languages. Third, ‘transfer is not simply a falling back on the native language’. Forth, ‘transfer is not always native language influence’ when speakers are capable of speaking more than two languages. Combining these viewpoints, Odlin (1989, p. 27) outlined a definition for substratum transfer: Transfer is the influence resulting from similarities and differences between the target language and any other language that has been previously (and perhaps imperfectly) acquired..

(23) 16. In other words, if speakers’ linguistic repertoire includes more than two languages, influences of all languages that speakers know may exist. Referring to pragmatics interchangeably with sociolinguistics, Wolson (1989) framed a definition of interlanguage as such: ‘The use of rules of speaking from one’s own native speech community when interacting with members of the host community or simply when speaking or writing in a second language is known as sociolinguistic or pragmatic transfer’ (p. 141). Located in the field of interlanguage pragmatics, Kasper’s (1992) claim was that pragmatic transfer should be understood as ‘the influence exerted by learners’ pragmatic knowledge of languages and cultures other than L2 on their comprehension, production and learning of L2 pragmatic information’ (p. 207). In this study, pragmatic and sociolinguistic types of transfer are separated apart as two perspectives and will both receive examination. The issue of pragmatic transfer has been testified in a substantial quantity of single moment interlanguage pragmatics studies comparing interlanguage with corresponding first and second language (Takahashi, 1996; Kasper & Rose, 2002). As seen in the line of the tangled relation of pragmatics and sociolinguistics, pragmatic and socio-cultural transfer are the most conspicuous researching areas, though L1 transfer also occurs in other sub-levels of language systems, including phonetics, morphology, syntax, and lexical semantics (see Odlin, 1989 for detail). The pragmatic part probed into how L1 influences the production or comprehension of form-function correspondence in L2 (see Blum-Kulka, 1982; Olshtain, 1983; Trosborg, 1987; Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Maeshiba, Yoshinaga, Kasper & Rose, 1996; Pair, 1996; Byon, 2004). The sociolinguistic one delved into speakers’ L1 transfer in association with whether their communicative and discourse style are appropriate in the social context (see Cohen & Olshtain, 1981; Olshtain, 1983; Beebe, Takahashi &.

(24) 17. Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Takahashi & Beebe, 1993; Yu, 1999, 2004). The following discussion will be centered on the shift of socio-cultural norms to second language output. Yu (1999), on the basis of the requesting behavior of native Chinese and American English speakers as well as Chinese ESL learners of English, discovered transfer in the sociolinguistic fashion in that the concept of directness and indirectness differs between Chinese and western cultures. For Chinese, the conventionally indirect strategy such as ‘Could you take it for me?’ was not the main linguistic device to alleviate the face-threatening force in making a request. Rather, Chinese denote their sincere and polite attitudes by considerable use of imperatives (e.g., ‘Please take it for me.’), corresponding as well to the communal image that Chinese adhere to in mutual interaction. Such diverse concepts about the strategic use of directness and indirectness often results in learners’ sociolinguistic transfer. Followed by an analogous researching method, Yu (2004) further examined the compliment responses by native Chinese and English speakers as well as EFL and ESL speakers. Again with the influence of L1 socio-cultural norms, native Chinese speakers and EFL speakers in Taiwan manifested more rejections than acceptance when receiving others’ compliments. Nevertheless, this may be coded as impoliteness in native English and for ESL speakers since in western culture non-acceptance implies the addressees’ disagreement with the compliment. Reminiscent of the revealed socio-pragmatic transfer in interlanguage, other studies referred the nature of socio-pragmatic transfer to learners’ perception of the target language as specificity or universality (e.g., Blum-Kulka, 1982; Olshtain, 1983; House & Kasper, 1987). That is, learners normally do not transfer their L1 pragmatic rules to L2 settings if they consider the L2 language-specific. Conversely, perceiving the L2 language as universal is more likely to lead learners to the case of pragmatic transfer..

(25) 18. The above literature indeed lends empirical support to transfer from the first language or its culture in the interlanguage and provides the conceptual source of language specificity/universality as explanatory basis. However, the relationship between transfer and development is far less addressed in the literature. Takahashi and Beebe (1987) advanced a hypothesis of positive correlation between learners’ language proficiency and pragmatic transfer. They predicted that higher-proficiency learners are prone to transfer more pragmatic principles from L1 to L2 because of more linguistic sources available for higher-level learners. Another study drawing contradictory results was launched by Maeshiba, Yoshinaga, Kasper and Ross (1996), who inspected intermediate and advanced Japanese-speaking ESL learners’ metapragmatic assessment of English apology. By distributing a questionnaire containing seven contextual factors, positive pragmatic transfer was found in those highly-agreed factors in both Japanese and English (i.e., status, obligation to apologize, and likelihood of acceptance) while negative transfer occurred in those with less agreement between the two languages at issue (i.e., offender’s face loss, offended party’s face loss, and social distance). With respect to the issue of development, advanced learner group demonstrated more positive and less negative transfer than the intermediate one, which did not echo the positive correlation hypothesis either. In addition to the product-oriented studies in pragmatic transfer mentioned above, Takahashi (1996) insisted to look on the process-oriented side. Her study of Japanese indirect request strategies in English was a comprehensive one dealing with the process dimension. Appealing to the ‘contextual appropriateness of an L1 pragmatic strategy’ and the ‘equivalence of the L1 and L2 strategies’, she examined how the two parameters relate to pragmatic transferability by computing possible pragmatic.

(26) 19. transferability rate. A result was found that the rate of conventional equivalence (e.g., would you please and would you) was higher than that of their pragmatic functions. This partly expounded that Japanese learners of English had difficulties identifying equivalent functional strategies for requests but depended heavily on their first language in the choice of request strategies or conventions. On the whole, exploration of both product and process ends certainly acknowledge the decisive character of pragmatic transfer in the scope of interlanguage pragmatics.. The Factor of Language Proficiency Some ILP work, (e.g., Scarcella, 1979; Trosborg, 1987, 1995; Maeshiba, Yoshinaga, Kasper & Ross, 1996), has been proven fruitful in illuminating influential factors in second language learners’ ILP development. One of the most momentous factors lies in learners’ language proficiency. Previous work on the factor of learners’ language proficiency has excited much controversy as to how the pragmatic ability relates to the grammatical ability. Owing to learners’ ‘universal pragmatic principles’ (see Walters, 1980; Schmidt, 1983; Koike, 1989a; Eisenstein & Bodman, 1993), also depicted as an ‘implicitly and proceduralized type of knowledge’ (Kasper & Rose, 2002, p. 164), pragmatic ability has been addressed to precede grammar competence. Unable to be consciously inspected, this pragmatic universality is formed when learners acquire their mother tongue or their generalization about languages. Examples of such universal pragmatic competence can be demonstrated in various communicative speech acts and politeness strategies (see Brown and Levinson, 1987). It has been argued that without this prior pragmatic knowledge, L2 learners cannot involve themselves in a collaborative interaction and further absorb new pragmatic knowledge in L2..

(27) 20. Empirical evidence of this universality of pragmatic ability can be well represented by the following work. In Schmidt’s (1983) study, the participant Wes manifested greater improvement in pragmatic competence than in grammatical competence during the four-year observation. This further lends support to the hypothesis that a limited repertoire of grammatical knowledge does not hinder from the development of the pragmatic and discourse abilities. More impressive findings were later revealed by Koike (1989a), who proposed that learner’s grammar was unlikely to be constructed as quickly as the pragmatic knowledge they had already built up in L1. However, learners could still express their existing pragmatic concepts through their restricted language proficiency. Moving toward Eisenstein and Bodman’s (1993) observation of advanced learners’ gratitude expressions, we can clearly identify various types of grammatical errors such as in the use of intensifiers, tenses, word orders, idioms, prepositions, and word choices yet with accurate illocutionary force. It was therefore argued by Eisenstein and Bodman (1993) that, no matter in what level, learners are all capable of operating their previously-acquired pragmatic knowledge and their L2 linguistic resources to practice illocutionary acts with politeness effects. The opposite position toward the relationship between pragmatics and grammar, however, held that the development of grammar ability was prior to that of pragmatic competence. In this stance, learners were shown to adopt correct grammar yet carry inappropriate pragmatic and socio-cultural meanings in a L2 communicative setting. In. the. following. discussion,. there. will. be. three. instances. in. this. grammar-preceding-pragmatics case: (1) ‘grammatical knowledge does not enable pragmatic use’; (2) ‘grammatical knowledge enables non-target-like pragmatic use’; (3) ‘grammatical and pragmatic knowledge enable non-target-like sociopragmatic.

(28) 21. use’ (Kasper & Rose, 2002, p. 175). A representative study of the first instance was conducted by Salsbury and Bardovi-Harlig (2000), who elicited the progressive use of modality from beginning ESL learners in disagreement performance through oral interviews. A steady progress in the acquisition of modality was sketched as such: ‘maybe > think > can > will > would > could’. In spite of this linear acquisition pattern, most illocutionary force of disagreement was actually bounded with semantically marked lexicons. The second instance known as non-target-like pragmatic use, yet manifesting grammatical knowledge in certain degree, could be illustrated by Takahashi and Beebe’s (1987). They found greater pragmatic transfer at the higher grammatical level among Japanese speakers of English. Namely, they demonstrated intensive honor in the act of receiving an invitation when speaking the foreign language, English. A possible explanation of advanced learners’ frequent transfer was advanced toward their superior control of the target language. That is, the skilled manipulation made them effortless express whatever they intended to. The last instance put its focal concern in the non-target-like socio-cultural use. Yu’s (2004) compliment study discovered that Chinese learners of English were more likely to react to compliments with rejections, completely different from American native speakers who tend to accept compliments with an agreement. This was due to Chinese speakers’ first attention to modesty and relative power attached to the behavioral values of their indigenous culture. In spite of the seemingly contradictory tendencies in learners’ development of pragmatic and grammatical knowledge, the pragmatics-grammar nexus discussed above at least uncovers a weighty role that learners’ language proficiency has in the developmental continuum of interlanguage pragmatics..

(29) 22. The Factor of Learning Context In addition to the factor of language proficiency, the role of learning context has also been a great concern in the field of interlanguage pragmatic development. Two widely-debated variables in the factor of learning context are the second/foreign learning environment and instructed/uninstructed settings. Takahashi and Beebe (1987) indicated that pragmatic transfer occurs in both ESL and EFL contexts, especially in the former environment. This could be illustrated by their finding that ESL learners’ refusal production converge more with their refusal utterances in the target language. Moreover, Bardovi-Harlig and Dornyei (1998) compared the pragmatic and grammatical awareness of ESL learners at an U.S. university and of EFL learners in Hungary. Results showed that ESL students hold better pragmatic consciousness than EFL ones do, which can be inferred from the finding that ESL speakers take pragmatic errors more seriously than grammatical ones in interaction. A possible explanation may relate to the speaker’s residency since one key factor to learners’ pragmatic competence development is the opportunity for learners to interact with native speakers in daily life. In an ESL environment, learners cannot but struggle for coding and decoding the exchanged information in the course of communication to maintain the relationship with native speakers. Facing more challenging interaction with native speakers in their daily social situations, ESL learners would tend to prompt their focus on socio-pragmatic dimensions. Conversely, in an EFL learning context, known as a test-guided situation, EFL learners may be led to stress ‘microlevel. grammatical. accuracy’. rather. than. ‘macrolevel. pragmatic. appropriateness’ due to the washback of frequent assessment. Such great difference in the motivational stimuli was proved significant in learners’ development of interlanguage, which is also true in Schmidt (1993)..

(30) 23. Another variable in the learning context discussed in most work is the instructed/uninstructed setting. Different findings of instructional effects on interlanguage development have been revealed in some research (see Billmyer, 1990; House, 1996), among which there were considerable ones affirming the positive effects of pragmatic instruction. Especially in those suspecting negative transfer from L1 to L2 due to the innate equivalence of language forms and functions, pragmatic instruction in the target language is considered necessary to purposely immerse learners in a simulated social setting and to explicitly provide them with the appropriate pragmatic use in L2. This is exactly what Takahashi (1996) attempted to verify in terms of the request forms and functions between Japanese and English. This was also true in Odlin (1989) that instructional setting results in positive transfer since teaching fosters learner’s awareness of pragmatic rules. Another study on instructional effects but focusing on a beginning level was conducted by Wildner-Bassett (1994), who inspected the conversational routines produced by 19 American learners of German, who had received one-year instruction in German. An inspiring finding arose that even learners of German in a beginning level acquires some conversational routines, so she advanced early instruction of these pragmatic and social routines. There are still more unexploited influencing factor variables in second language learners’ interlanguage development (e.g., length of residence, input and interaction in noninstructional settings, etc.) (see Kasper & Rose, 2002 for more review). However, the two factors reviewed here, language proficiency and learning context, adequately indicates a strong connection between interlanguage development and pedagogical practice. Therefore, more empirical studies should be conducted to further explore how these two factors interact with each other in the second language acquisition process..

(31) 24. INTERLANGUAGE PRAGMATICS OF THE SPEECH ACT OF REFUSALS As shown in interlanguage pragmatics research, second language learners make major efforts in using their limited set of linguistic resources to convey a wide range of meaningful and affective cues of messages. Such task done by learners also account for what they would do in the act of refusals. Therefore, refusal studies concerning the speech act and interlanguage aspects are indeed necessary for discussion. In the following sections, refusal studies will be introduced first along the line of speech act aspect, followed by that of the interlanguage one.. Issue 1: Speech Act Aspect In the similar vein in earlier sections, the speech act aspect of refusals can be distributed into those within one specific language as well as two languages for comparison. As for the act of refusal within one language, the impediment of compliance in essence makes it highly face-threatening, leading scholars to explore the use of face-saving maneuvers in terms of the politeness goal. A significant one was conducted by Turnbull and Saxton (1997), who induced phone interviewees to reject a research assistant’s request to participate in psychological experiments. They contended that in refusals English speakers engage themselves in interpersonal work with modal structures. Three modal structures, ‘epistemic probability/possibility’ (e.g., I don’t think so), ‘root necessity/probability’ (e.g., I have to work), and a combination of both (e.g., I don’t think I can) used by the interviewees extensively appear in five types of refusing strategies: ‘negate request’, ‘negated ability’, ‘indicate unwillingness’, ‘performative refusals’, and ‘identify external impeding factors’. This modal logic denotes the speaker’s reluctance and/or obligation to decline, thereby.

(32) 25. taking on a critical role in repairing the interlocutors’ face and accomplishing the conversation. As a socio-culture-specific speech, refusals done by Chinese and westerners are actually in divergent fashion (See Gu, 1990; Ma, 1996). Two studies conducted between English and Chinese are presented as follows. Shih (1986) proposed that ‘off-record’ strategies (see Brown and Levinson, 1978, pp. 211-227) are most familiar in refusals among Chinese, for whom saying ‘no’ is more difficult than not answering at all. Liao and Bresnahan (1996), inspecting how American and Taiwanese university students gave refusals in response to six hypothetical scenarios of requests, advanced the dian-dao-wei-zhi “point-to-is-end—marginally touch the point” theory as an interpretation of Chinese ‘off-record’ politeness realization. These comparison studies indeed provide a better understanding of speech act manifestation across languages.. Issue 2: Interlanguage Aspect Regarding the interlanguage aspect in the existing refusal studies, the most frequently-adopted research method should be the comparison of refusal production produced by native and non-native speakers. Three important studies adopting this methodology will be presented as follows. Beebe, Takahashi and Uliss-Weltz (1990) presented an in-depth analysis on refusals produced by learners and native speakers of English from questionnaires. It was reported that Japanese learners of English prefer vague excuses—vague as to the detailed time and place involved with their excuses, as opposed to Americans’ specific way of telling others their plans. This difference, probably attributed to transfer of L1 socio-cultural principles, suggests the potential learning difficulty that L2 learners may encounter in developing their pragmatic ability. Focusing on.

(33) 26. academic advising session, Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford (1991) compared the semantic formulas used by native speakers and non-native speakers of English in refusing an advisor’s suggestion. By examining the tape recordings of actual advising sessions and by using Beebe, Takahashi and Uliss-Weltz’s (1990) taxonomy, they indicated that the semantic formulas used by native and nonnative speakers to reject their advisors’ suggestions differ quantitatively and qualitatively. For instance, the most frequently used semantic formula by both native speakers and nonnative speakers are reasons/explanations. While the second most common strategy among native speakers are alternatives, that among nonnative speakers is avoidance. Furthermore, the range of content of nonnative speakers’ reasons is broader and often more unacceptable. However, there still exist some similarities in refusals between languages. For instance, Nelson, Carson, Batal and Bakary (2002) drew a conclusion that many more similarities than differences were revealed among Americans and Egyptians in making refusals. They further indicated that pragmatic similarities are more likely to result in pragmatic success. The literature presented in this paper provides a window onto the intensive interaction of speech act theory and interlanguage pragmatics. At the outset of this chapter, much research has directly informed the intricate nature of pragmatic and socio-cultural aspects of speech act theory. As appeals have been considerably made to these two aspects in setting the targets for analysis, second language learners’ interlanguage in speech acts should also be invoked in terms of both pragmatic and socio-cultural perspectives. It is to this end that the research focus of this thesis will be concentrated on the pragmatic and socio-cultural manifestations of the speech act of refusal in Chinese students’ English interlanguage..

(34) 27. CHAPTER 3 METHOD. SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS The participants in the study were 134 Chinese undergraduates majoring in English in three universities in Taiwan. Among them, 31 were from National Chiao Tung University; 28 from National Taipei University; 75 from National Taipei University of Technology. There were 110 females and 24 males ranging in age from 18 to 25 years old. The participants were all university-level students, who have passed the Joint College Entrance Examination (also called JCEE) in Taiwan. In addition, they as English majors must have taken English courses for at least one year. With these requirements that an English major must have reached, the participants in this study were at least in a proficiency level of having no difficulty in constructing simple and complete English sentences to express themselves. In doing this, the extremely low-language-level learners who did not have proficient ability to freely convey themselves can be excluded since language proficiency may be an influential factor in exploring pragmatic and sociocultural competence (e.g., Yu, 1999).. INSTRUMENTS The instrument used to collect data in this thesis was a written questionnaire in the form of Discourse Completion Task (DCT), a popular method of data collection in speech act studies (for reviews of interlanguage methods see Kasper & Dahl, 1991; Rose & Ono, 1995; Hinkel, 1997). DCT normally consists of a number of situational descriptions, followed by a dialogue initiation with an empty slot for elicitation of the speech act at issue. Although DCT has the drawback of not representing the naturally.

(35) 28. occurring speech (Beebe & Cummings, 1996), it is still known for its utility for collecting large amounts of data and for conducting in-depth quantitative analysis. Henceforth, DCT was adopted as a tool in soliciting Chinese undergraduates’ interlanguage refusals in this study. The DCT questionnaire in this study was designed to uncover the exploratory results in Chinese learners’ interlanguage refusals in response to requests. It consisted of scripted situations, which represented socially differentiated contexts with different requesting contexts. In order to avoid biasing the participants’ response choices, the word refusal was not used in the descriptions (Beebe & Takahashi, 1989). The designed situations involved two types of jobs that respectively needed the applicants’ labor and mental contribution. One was labor work that required them to clean classrooms in a school building from seven to ten o’clock every Saturday and Sunday morning during the whole semester. The other one was in want of their mental efforts in reading over two hundred websites on English writing and grammar, for each of which a Chinese introduction as a guide to users needed to be completed. This job also demanded them to finish at least eight websites per hour. These two jobs were so constructed to appear demanding but reasonable so that the participants could be easily engaged in the imagination of the request-refusal situation. Moreover, these jobs required distinct types of ability that characterized them individually as labor work and brain work. The reason for such design was to ensure that students fond of different part-time jobs would all find either job reasonably to be declined. Examples of Job 1 and Job 2 are illustrated as follows.. Example: Job 1 You are required to clean classrooms in a school building from 7 to 10 every.

(36) 29. Saturday and Sunday morning during the whole semester. If you do not want to take this position after knowing its demanding workload, what would you say to the teaching assistant? TA: Would you like to take this job? You: ________________________________________________________________. Example: Job 2 You are required to read and write introductions to over 200 English learning websites. Eight websites need to be finished within one hour. If you do not want to take this position after knowing its demanding workload, what would you say to the teaching assistant? TA: Would you like to take this job? You: _________________________________________________________________. It should be noted that the constructed situations need to be intellectually and culturally plausible for the participants so that their responses would not hamper the validity of the results. Considering the suitability of the given context, the depicted situations in the DCT were rather specifically close to the university life. The part-time job recruitment was chosen according to the fact that taking part-time jobs is common to university students, also having been used in previous studies (see Hsieh & Chen, 2004; 2005a; 2005b) to collect the refusal data from undergraduates in Taiwan universities in their native language, Mandarin Chinese. Results showed that this social context was not unfamiliar to them since they could give proper responses.

(37) 30. in Mandarin Chinese tallying with the requested inquiry (for results in Chinese refusals see Hsieh and Chen, 2004; 2005a; 2005b). In an attempt to investigate learners’ oral rejection, the DCT was composed in its ultimate endeavor to create oral scenarios. To this end, refusal responses were not provided in the form of multiple choices. In the view of some researchers (Rintel & Mitchell, 1989; Beebe, Takahashi, & Uliss-Weltz, 1990), providing participants potential responses would limit the elicited speech acts and bias the results, though Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford (1993, p.159) indicated that DCT supplying possible hearer responses were better suited to nonnative speakers who were not linguistically and culturally competent in realizing and reacting to the given requests. However, in the case of this study, the data collection would not be stained with the participants’ language competence and with the designed situations due to the selection of English majors from universities as participants and the launch of the previous refusal studies in Chinese (i.e., Hsieh and Chen, 2004; 2005a; 2005b). Blank lines for refusal responses were given after the imaginaand Can you take this job for me?) Inclusion of such prompts was particularly preferable for studies of speech acts that were responses (such as rejections) instead of initiations (such as requests) (Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford, 1993). Stated as in the beginning of the questionnaire, participants should picture themselves in the action of refusing the requester. In spite of this, still two participants indicated acceptance or the choice of opting out as their response to the described requests, which should be excluded from the refusal analysis and therefore resulted in 266 pieces of response by 134 undergraduates..

(38) 31. PROCEDURES. The Discourse Completion Test was distributed to English majors of three universities. They were undergraduates from the courses of Multimedia English Workshop and Communicative Skills Workshop in National Chaio Tung University; Second Language Acquisition in National Taipei University; Phonetics and Technical Reading and Writing in National Taipei University of Technology. The researcher first explained how to answer the designed questions, reminding the participants of giving intuitional responses. After the data collection, two inter-raters assisted analyzing the participants’ responses to ascertain the reliability of the coding scheme.. DATA ANALYSIS In order to identify interlanguage features, a classification of refusal responses were needed. However, there has been little consensus among different accounts as to within what standard criteria the categorizations of the act of refusals are to apply. Beebe, Takahashi and Uliss-Weltz’s (1990) categorization model is probably the best-known and most frequently cited taxonomy for analyzing refusals (Gass & Houck, 1999). In line with their coding principle, refusals of each participant in this study were analyzed as a sequence of formulas coded in terms of their semantic content. Here is an example which was encoded in light of the semantic formulas, such as “I’m sorry (Regret), I’m not so a writer (Excuse), I don’t think I could write good introductions (Excuse). So why don’t you try on someone who is batter on writing? (Proposal of alternative)” New categories of semantic formulas were identified based on the corpus of this study. This remodeled categorization for the act of refusal was used for further qualitative analysis..

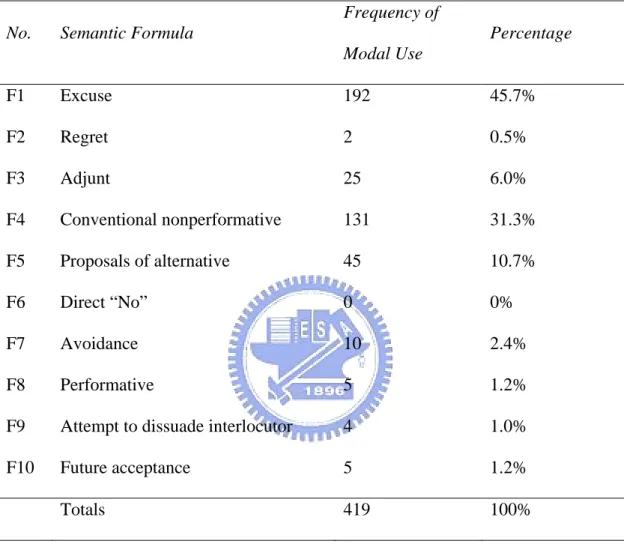

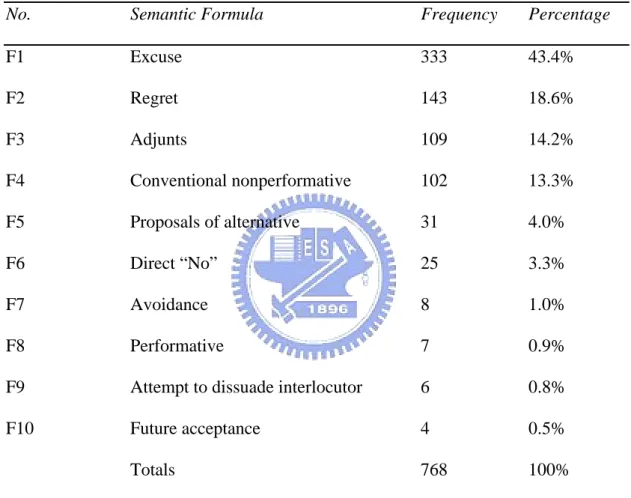

(39) 32. CHAPTER 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION. THE USE OF SEMANTIC FORMULA The refusal data elicited from Chinese learners speaking English exhibit ample interlanguage features. The first section in Chapter 4 will delve into these interlanguage refusals in terms of the quantity, the order, and the length aspects of semantic formulas produced by Chinese students. Considering how students incorporate these formulas and other pragmatic indicators in the act of refusing, the second section in Chapter 4 will investigate the use of modification and of modal devices. In order to comprehensively present the refusal data, the original transcription of the solicited production will be included in the following discussions as given examples without any correction of grammar or spelling.. The Quantity Aspect The Chinese participants speaking English as a foreign language provided a total of 266 responses, in which 768 semantic formulas were found. Table 1 shows the raw frequencies and percentage of each type of formula in learners’ data. As Table 1 indicates, of the total 768 formula produced by learners, learners adopted Excuse formula (F1) most often, which makes up 43.4% of the total semantic formulas (333 out of 768). Moreover, Regret (F2), Adjunct (F3), and Conventional nonperformative (henceforth called Nonperformative) (F4) formulas comprise respectively 18.6% (143 out of 768), 14.2% (109 out of 768), and 13.3% (102 out of 768) of all the formulaic use by Chinese students in performing English refusal. It should be noted that the Adjunct formula (F3) attaining such a high rank (14.2%) is.

(40) 33. due to its multiple subcategories (i.e., Appreciation, Statement of positive opinion, Pause filler, Repetition, and Emotional expressions), which will be introduced in detail in the following.. Table 1: Occurring frequency and percentage semantic formula used by Chinese students No.. Semantic Formula. Frequency. Percentage. F1. Excuse. 333. 43.4%. F2. Regret. 143. 18.6%. F3. Adjunts. 109. 14.2%. F4. Conventional nonperformative. 102. 13.3%. F5. Proposals of alternative. 31. 4.0%. F6. Direct “No”. 25. 3.3%. F7. Avoidance. 8. 1.0%. F8. Performative. 7. 0.9%. F9. Attempt to dissuade interlocutor. 6. 0.8%. F10. Future acceptance. 4. 0.5%. Totals. 768. 100%. Note. F=Semantic Formula; each number was rounded to one decimal.. The semantic formula will be expounded following the quantitative sequence listed in Table 1 in terms of its pragmatic function. Sample responses produced by learners will also be provided for demonstration. Excuse (F1): Excuses are situational-oriented in the sense that the type of reasons learners bring up varies with the nature of the requested events devised in this.

(41) 34. study. For those in response to the event of editing introduction for English websites, reasons normally pertain to the speaker’s internal impeding factors which encompass such personal traits as ability, intelligence, physical strength, and psychological conditions of the refuser. Hence, by pointing out the impediment of internal factors, refusers refer their declination to absence of certain necessary characteristics in association with themselves to justify their denial. An indication of this is presented in (1), (2), and (3). In order to be specific, some learners even point out their incompetence either in language or in computer skills.. (1). Maybe I don’t think I have ability to take this job, You can find other people to take.. (2). Sorry, I’m not really good at designing the website, maybe you can find another person.. (3). Sorry, my English is not good enough to do it.. On the other hand, impeding factors external to the speaker mostly correlate to the request of cleaning public areas. They refer to those reasons for rejection that arise from considerations for factors out of the range of capacities refusers are equipped with. Reasons of this type occur more often in situations where refusers respond to requests to participate in the cleaning job than in those where they reply to the writing task. A principal cause is that cleaning classrooms requires job-takers no particular capabilities as what are expected in the case of writing introductions to English websites. Almost every university student with normal physical conditions as well as available working hours is able to carry out the duty of cleaning. Along such line of reasoning, external impeding factors can satisfy the validity of their declination. This.

數據

Outline

相關文件

In the context of the English Language Education, STEM education provides impetus for the choice of learning and teaching materials and design of learning

• e‐Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

To provide suggestions on the learning and teaching activities, strategies and resources for incorporating the major updates in the school English language

- allow students to demonstrate their learning and understanding of the target language items in mini speaking

(2013) The ‘Art’ of Teaching Creative Story Writing In (Eds., Janice Bland and Christiane Lütge) Children’s Literature in Second Language Education. (2004) Language and

• helps teachers collect learning evidence to provide timely feedback & refine teaching strategies.. AaL • engages students in reflecting on & monitoring their progress

one on ‘The Way Forward in Curriculum Development’, eight on the respective Key Learning Areas (Chinese Language Education, English Language Education, Mathematics

(“Learning Framework”) in primary and secondary schools, which is developed from the perspective of second language learners, to help NCS students overcome the