R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

To examine the associations between

medical students

’ conceptions of learning,

strategies to learning, and learning

outcome in a medical humanities course

Yu-Chun Chiu

1,2, Jyh-Chong Liang

3, Hong-Yuan Hsu

1,4, Tzong-Shinn Chu

4,5, Kuan-Han Lin

6*, Yen-Yuan Chen

2,4*and

Chin-Chung Tsai

3Abstract

Background: By learning medical humanities, medical students are expected to shift from handling the diseases only to seeing a whole sick person. Therefore, understanding medical students’ learning process and outcomes of medical humanities becomes an essential issue of medical education. Few studies have been conducted to explore factors surrounding medical students’ learning process and outcomes of medical humanities. The objectives were: (1) to investigate the relationships between medical students’ conceptions of learning and strategies to learning; and (2) to examine the relationships between students’ strategies to learning and learning outcomes for medical humanities.

Methods: We used the modified Approaches to Learning Medicine (mALM) questionnaire and Conceptions of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire to measure the medical students’ strategies to learning and conceptions of learning respectively. The learning outcome of medical humanities was measured using students’ weighted grade in a medical humanities course. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the COLM and mALM questionnaires, in which construct validity and reliability were assessed. Pearson’s correlation was used to examine the relationships among the factors of COLM, mALM, and the weighted grade. Path analysis using structural equation modeling technique (SEM) was employed to estimate the structural relationships among the COLM, mALM, and the weighted grade.

Results: Two hundred and seventy-five first-year medical students consented to participate in this study. The participants adopting surface strategies to learning were more likely to have unsatisfactory learning outcome (β = − 0.14, p = .04). The basic-level conception of “Preparing for Testing” was negatively (β = − 0.19, p < .01) associated with deep strategies of learning, and positively (β = 0.48, p < .01) associated with surface strategies of learning (β = 0.50, p < .01). The basic-level conception of “Skills Acquisition” was positively associated with deep strategies of learning (β = 0.23, p < .01).

Conclusion: Medical educators should wisely employ teaching strategies to increase students’ engagement with deep and self-directed learning strategies, and to avoid using surface learning strategies in the medical humanities course in order to achieve better learning outcomes.

Keywords: Conceptions of learning, Approaches to learning, Strategies to learning, Medical humanities

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

* Correspondence:okonkwolin@gmail.com;chen.yenyuan@gmail.com 6

Department of Healthcare Administration, Asia University, #500, Rd. Liou-Feng, Wufeng, Taichung 41354, Taiwan

2Department of Medical Education, National Taiwan University Hospital, #7, Rd. Chong-Shan S, Taipei 10002, Taiwan

Background

Medical humanities is a multidisciplinary field including humanities, social sciences, the arts, and their applications to clinical practice [1,2]. By learning medical humanities, medical students are expected to think critically, to under-stand personal values, and to be equipped with cultural competence, leadership and teamwork, and empathy. Given that medical humanities is considered as shifting medicine from handling the diseases only to seeing a whole sick person [3], and that learning medical human-ities is expected to prepare medical students for respond-ing appropriately to complex clinical contexts [4], there has been a consensus that medical humanities should be integrated into the medical curriculum [5]. Although the importance of medical humanities is usually highlighted in medical education, medical humanities remained as the undesirable part of medical education, and medical humanities curriculum in medical schools receives more critiques than praises [2, 6]. Therefore, understanding medical students’ learning process and learning outcomes of medical humanities courses becomes an essential issue of medical education.

The learning process and outcomes of medical stu-dents have always been greatly concerned about by their teachers and medical educators, particularly the learning outcomes of medical humanities. Better learning out-comes for medical humanities imply that medical stu-dents may be capable of responding to complex clinical context. Among the factors which influence learning outcomes, conceptions of learning and approaches to learning have been reported as two of the most influen-tial factors on students’ learning [7–11].

“Conceptions of learning” is defined as learners’ coher-ent knowledge and beliefs about the whole picture of learning [7, 12]. Tsai reported two levels of conceptions of learning, and each level includes a total of three to four factors, i.e. higher-level conceptions of learning (“Increasing One’s Knowledge”, “Applying”, “Under-standing”, and “Seeing in a New Way”) and lower-level conceptions of learning (“Memorizing”, “Testing”, “Cal-culating”, and “Practicing Tutorial Problems”) [7]. In comparison, “approaches to learning” implies students’ motivations and strategies to learn or process the academic work [13]. Prior studies have reported surface approaches and deep approaches to learning. Surface approaches to learning include surface motivations (“Fear of Failure” and “Aim for Qualification”) and surface strategies (“Minimizing Scope of Study” and “Memorization”), and deep approaches to learning in-clude deep motivations (“Intrinsic Interest” and “Com-mitment to Work”) and deep strategies (“Relating Ideas” and“Understanding”) [11,14,15].

Several studies have examined the relationships between conceptions of learning and approaches to learning in the

disciplines of science [16], biology [11], and computer sci-ence [17]. Students with higher-level conceptions of learn-ing utilized deep strategies to learnlearn-ing, and those with lower-level conceptions utilized surface strategies [11,16]. Both lower-level and higher-level conceptions of learning have been found to be positively associated with surface motivation in computer science [17]. Prior studies in medical education have been mostly focused on the approaches to learning [18–22], but few of them were fo-cused on the conceptions of learning and the relationship between the conceptions of learning and the approaches to learning in medical students.

Previous studies have reported the relationships between the approaches to learning and learning outcomes for non-medical learners [23,24]. For example, Snelgrove et al. re-ported that student nurses’ deep approaches to learning sociology were positively and significantly related to their exam results and grade point average, and surface strategies negatively related to the learning outcomes without statis-tical significance [23]; and Chamorro-Premuzic et al. also found that the use of the deep approaches to learning was the most influential than personality and intelligence to ac-count for the variances of students’ academic performance [24]. In addition, the relationships between the approaches to learning and the learning outcomes for medical leaners were also examined [18, 22, 25]. For example, Reid et al. showed that medical students scored positively with deep approaches to learning and negatively with surface ap-proaches [25]. Liang et al. also examined the relationships between the approaches to learning and learning outcomes. They reported that the deep strategy, i.e. relating ideas and understanding, significantly predicted better learning out-comes, and the surface strategy, i.e. minimizing scope of study, significantly predicted unsatisfactory learning out-comes [22].

Although higher-level and lower-level conceptions of learning, and approaches to learning (deep motives, sur-face motives, deep strategies, and sursur-face strategies) were studied in medical education, none of the prior studies have been conducted to examine those surrounding the learning outcomes of medical humanities. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the relationships between medical students’ conceptions of learning and strategies to learning, and to examine the relationships between students’ strategies to learning and learning outcomes for medical humanities.

Methods

Setting

We conducted this study in the most academically presti-gious medical school in a university located in Northern Taiwan. While this study was conducted, the medical school enrolled approximately 155 students each year.

Data collection

We recruited the first-year medical students of the 2015—2016 cohort and the 2016—2017 cohort to par-ticipate in this study, all of whom had taken the required course of“Medicine and Humanities.”

This course was mainly composed of four segments general introduction: medical arts, medical history, medical philosophy, and Taiwan literature. A group of lecturers par-ticipated in teaching different topics in this lecture-based medical humanities course. Each topic, belonging to one of the four segments, was a two-hour lecture. The two-hour lecture was conducted once every week, 15–16 lectures a semester. In addition, students were required to participate in an experiential learning activity, and to give feedback and reflections on their learning.

The students were asked whether they would like to participate in this study or not. Two questionnaires with a cover letter explaining the purpose of this study were distributed to those who consented to participate in this study. In addition, the weighted grade of each participat-ing medical student of the “Medicine and Humanities” course was considered the learning outcome of medical humanities.

Instruments

We measured the first-year medical students’ concep-tions of learning medicine using the Concepconcep-tions of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire, which origin-ally had seven developed [7] factors. Two factors,“Skills Acquisition” and “Communication”, were added thereafter, using the contributions from three medical professionals, with the aim to demonstrate the unique characteristics of the medical discipline.

The COLM questionnaire used in this study consists of nine factors: advanced-level conceptions of learning medi-cine, highlighting relating learning medicine to application to medical practice, including “Increasing One’s Know-ledge”, “Applying”, “Understanding”, “Seeing in a New Way”, and “Communication”; and basic-level conceptions of learning medicine, focusing on learning medicine itself without paying attention to application to medical practice, including “Memorizing”, “Preparing for Testing”, “Prac-ticing Tutorial Problems”, and “Skills Acquisition.” Each factor contains a total of five to seven items, and a total of 56 items are included in the COLM questionnaire. A par-ticipant’s score of each factor was calculated by taking the average of all items in the factor. The sample items for each factor included in advanced-level and basic-level concep-tions of learning medicine are shown below (Appendix 1):

Basic-level COLM: Memorizing

“Learning medicine means memorizing the physiological mechanisms of humans in medical textbooks”

Basic-level COLM: Preparing for Testing “Learning medicine means passing all the examinations to obtain professional certification” Basic-level COLM: Practicing Tutorial Problems.

“Learning medicine means practicing with a SimMan simulator.”

Basic-level COLM: Skills Acquisition.

“Learning medicine means learning how to study systematically, such as using a concept map.” Advanced-level COLM: Increasing One’s Knowledge.

“Learning medicine means acquiring more medical knowledge.”

Advanced-level COLM: Applying

“Learning medicine means solving human medical problems.”

Advanced-level COLM: Understanding

“The purpose of learning medicine is to understand medical knowledge.”

Advanced-level COLM: Seeing in a New Way “Learning medicine means expanding my medical knowledge and visions.”

Advanced-level COLM: Communication “Learning medicine means learning how to cooperate with others as a team to complete the task.”

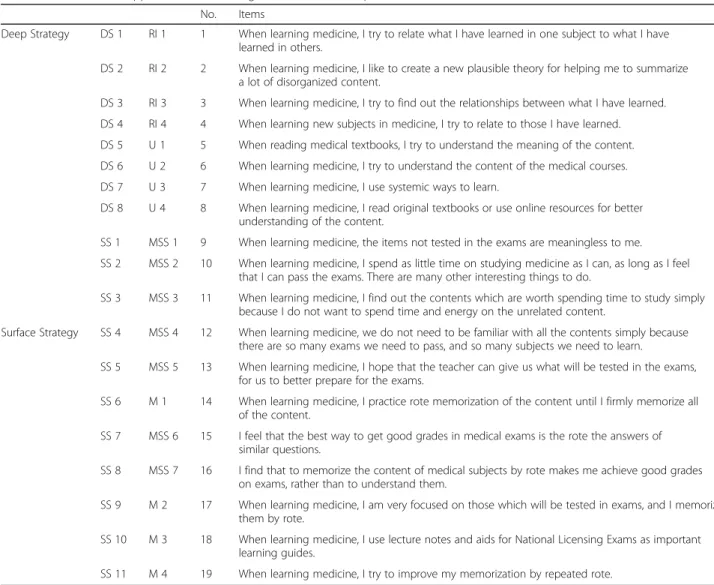

We used the modified Approaches to Learning Medi-cine (mALM) questionnaire, borrowing from the Ap-proaches to Learning Medicine (ALM) questionnaire, for measuring the first-year medical students’ strategies to learning medicine [22]. This mALM questionnaire is composed of deep strategies (four items for “Relating Ideas” and four items for “Understanding”) and surface strategies (seven items for “Minimizing Scope of Study” and four items for “Memorization”). All the items were coded using a Likert scale ranging from one to five, representing “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” re-spectively. A participant’s score of each strategy was cal-culated by taking the average of a factor’s all included

items in the strategy. The sample items for each strategy included in deep strategies and surface strategies are shown below (Appendix 2):

Deep Strategies: Relating Ideas

“When learning medicine, I like to create a new plausible theory for helping me to summarize a lot of disorganized content.”

Deep Strategies: Understanding

“When learning medicine, I try to understand the content of the medical courses.”

Surface Strategies: Minimizing Scope of Study “When learning medicine, I spend as little time on studying medicine as I can, as long as I feel that I can pass the exams. There are many other interesting things to do.”

Surface Strategies: Memorization

“When learning medicine, I am very focused on those which will be tested in exams, and I memorize them by rote.”

The learning outcome of medical humanities was measured using students’ weighted grade in the med-ical humanities course. The weighted grade was based on a global rating consisting of 40% class participa-tion, 25% short paper writing surrounding medical humanities issues, 25% term examination using mul-tiple choice questions focused on the lecture and assigned readings of the course, and 10% motivation and performance in experiential learning activities. Students’ grades were collected at the end of the course, and the score was treated as a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 100.

Statistical analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the COLM and mALM questionnaires, in which construct validity and reliability were assessed. The factor loading of each item, average variance ex-plained (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were estimated.

Pearson’s correlation was used to examine the rela-tionships among the factors of COLM, mALM, and weighted grade. The relationships between two vari-ables/factors with ap value of less than .20 were retained for further path analysis.

Path analysis using structural equation modeling technique (SEM) was employed to estimate the

structural relationships among the COLM, mALM, and students’ learning outcomes. The goodness of model fit was assessed, using the goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and normed fit index (NFI), to ensure that the structural model reasonably explained the structural relationships among COLM, mALM, and learning outcomes.

A p value of less than .05 were considered statisti-cally significant. All statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS AMOS 24 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). This study was approved by the Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee in National Taiwan University (201505HS002). The first-year medical students were asked verbally of their preference to participate in this study or not. Written consent was then obtained from those who preferred to participate in this study by signing the informed consent form, which was approved by the Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee in National Taiwan University.

Results

Two hundred and seventy-five (97.52%) of the 282 first-year medical students, 130 from the 2015—2016 cohort and 145 from the 2016—2017 cohort, consented to par-ticipate in this study. Among those 275 participating first-year medical students, 272 (98.91%), 67 females (24.63%) and 205 males (75.37%), completely answered the two questionnaires and were eligible for data ana-lysis. The participants’ ages ranged from 17.08 to 30.22 years old, with an average of 19.30 (standard deviation = 1.64).

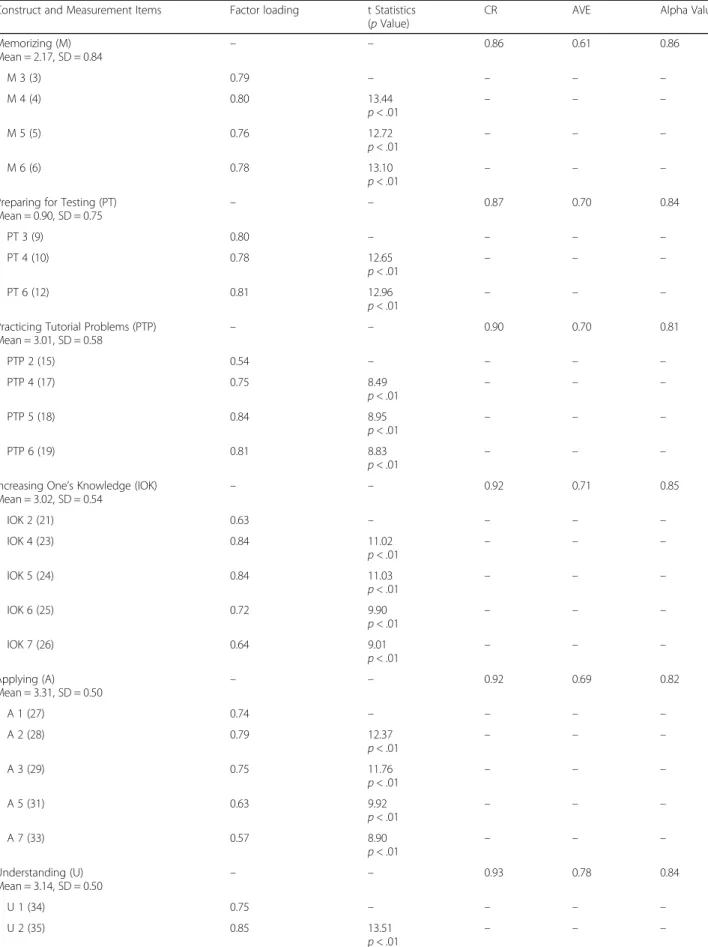

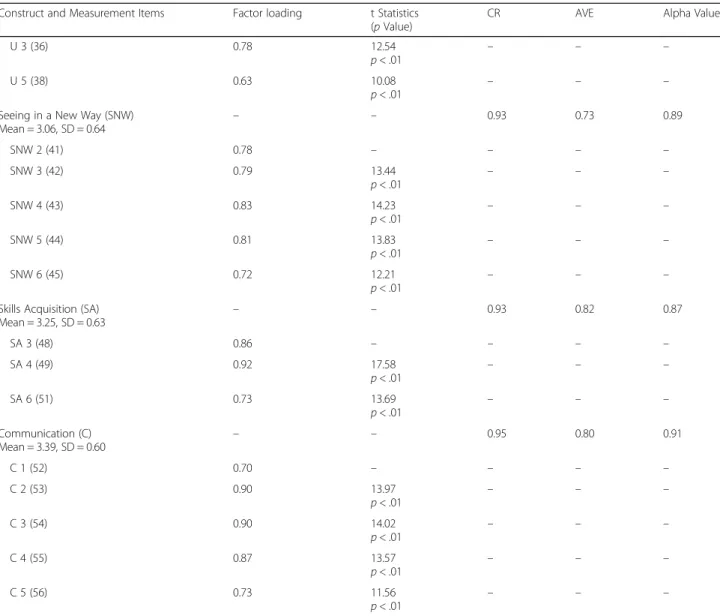

By CFA, 38 items, belonging to the four factors of advanced-level conceptions and five factors of basic-level of conceptions, were retained in the final version of the COLM questionnaire. The results of CFA re-vealed significant factor loadings for all items (values larger than 0.5) [26]. Furthermore, the scores of AVE and CR for the nine factors were higher than the threshold values of 0.5 and 0.7 [27, 28], with the scores ranging from 0.61 to 0.82 and 0.86 to 0.95, re-spectively, indicating acceptable construct validity and reliability (Table 1).

A total of eight items, five for deep strategies and three for surface strategies, were retained in the final version of mALM questionnaire after CFA. The factor loading values ranged from 0.59 to 0.92 and were greater than 0.5, suggesting suitable factor loadings [26]. The values of AVE and CR for two factors of mALM ranged from 0.52 to 0.79 and 0.77 to 0.95, re-spectively, demonstrating acceptable construct validity and reliability (Table 2) [27, 28].

Table 1 The CFA analysis for the Conception of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire. (N = 272)

Construct and Measurement Items Factor loading t Statistics

(p Value)

CR AVE Alpha Value

Memorizing (M) Mean = 2.17, SD = 0.84 – – 0.86 0.61 0.86 M 3 (3) 0.79 – – – – M 4 (4) 0.80 13.44 p < .01 – – – M 5 (5) 0.76 12.72 p < .01 – – – M 6 (6) 0.78 13.10 p < .01 – – –

Preparing for Testing (PT) Mean = 0.90, SD = 0.75 – – 0.87 0.70 0.84 PT 3 (9) 0.80 – – – – PT 4 (10) 0.78 12.65 p < .01 – – – PT 6 (12) 0.81 12.96 p < .01 – – –

Practicing Tutorial Problems (PTP)

Mean = 3.01, SD = 0.58 – – 0.90 0.70 0.81 PTP 2 (15) 0.54 – – – – PTP 4 (17) 0.75 8.49 p < .01 – – – PTP 5 (18) 0.84 8.95 p < .01 – – – PTP 6 (19) 0.81 8.83 p < .01 – – –

Increasing One’s Knowledge (IOK)

Mean = 3.02, SD = 0.54 – – 0.92 0.71 0.85 IOK 2 (21) 0.63 – – – – IOK 4 (23) 0.84 11.02 p < .01 – – – IOK 5 (24) 0.84 11.03 p < .01 – – – IOK 6 (25) 0.72 9.90 p < .01 – – – IOK 7 (26) 0.64 9.01 p < .01 – – – Applying (A) Mean = 3.31, SD = 0.50 – – 0.92 0.69 0.82 A 1 (27) 0.74 – – – – A 2 (28) 0.79 12.37 p < .01 – – – A 3 (29) 0.75 11.76 p < .01 – – – A 5 (31) 0.63 9.92 p < .01 – – – A 7 (33) 0.57 8.90 p < .01 – – – Understanding (U) Mean = 3.14, SD = 0.50 – – 0.93 0.78 0.84 U 1 (34) 0.75 – – – – U 2 (35) 0.85 13.51 p < .01 – – –

Table 3 shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficients

among the factors of COLM, mALM, and the weighted grade. All factors of the advanced-level con-ceptions of learning medicine (“Increasing One’s Knowledge”, “Applying”, “Understanding”, “Seeing in a New Way”, and “Communication”) were positively re-lated to the deep strategies to learning medicine (r = 0.13~0.28, p values = <.01~.03). In comparison, most of the factors of the basic-level conceptions of learn-ing medicine (“Memorizlearn-ing”, “Preparlearn-ing for Testlearn-ing”, and “Skills Acquisition”) were significantly related to the surface strategies to learning medicine (r =− 0.13~0.43, p values = <.01~.03). Interestingly, the med-ical students with the conception of learning medi-cine—“Practicing Tutorial Problems” were more likely

to learning medical humanities using deep strategies (r = 0.16, p value = .01).

Figure 1 shows the SEM structural model, and only the significant standardized path coefficients are dis-played. According to the results of path analysis, the participants with surface strategies to learning medi-cine were more likely to have worse learning outcome as indicated by the weighted grade of the medical hu-manities course (β = − 0.14, p value = .04). In addition, the basic-level conception of “Preparing for Testing” was negatively (β = − 0.19, p value < .01) associated with deep strategies of learning medicine, and positively (β = 0.48, p value < .01) associated with surface strategies (β = 0.50, p value < .01). The basic-level conception of “Skills Acquisition” was positively associated with deep Table 1 The CFA analysis for the Conception of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire. (N = 272) (Continued)

Construct and Measurement Items Factor loading t Statistics

(p Value)

CR AVE Alpha Value

U 3 (36) 0.78 12.54

p < .01

– – –

U 5 (38) 0.63 10.08

p < .01 – – –

Seeing in a New Way (SNW) Mean = 3.06, SD = 0.64 – – 0.93 0.73 0.89 SNW 2 (41) 0.78 – – – – SNW 3 (42) 0.79 13.44 p < .01 – – – SNW 4 (43) 0.83 14.23 p < .01 – – – SNW 5 (44) 0.81 13.83 p < .01 – – – SNW 6 (45) 0.72 12.21 p < .01 – – –

Skills Acquisition (SA)

Mean = 3.25, SD = 0.63 – – 0.93 0.82 0.87 SA 3 (48) 0.86 – – – – SA 4 (49) 0.92 17.58 p < .01 – – – SA 6 (51) 0.73 13.69 p < .01 – – – Communication (C) Mean = 3.39, SD = 0.60 – – 0.95 0.80 0.91 C 1 (52) 0.70 – – – – C 2 (53) 0.90 13.97 p < .01 – – – C 3 (54) 0.90 14.02 p < .01 – – – C 4 (55) 0.87 13.57 p < .01 – – – C 5 (56) 0.73 11.56 p < .01 – – –

Abbreviation List: CFA Confirmatory Factor Analysis, CR Composite Reliability, AVE Average Variance Extracted, M Memorizing, PT Preparing for Testing, PTP Practicing Tutorial Problems, IOK Increasing One’s Knowledge, A Applying, U Understanding, SNW Seeing in a New Way, SA Skills Acquisition, C Communication

strategies of learning medicine (β = 0.23, p value < .01). The indices suggested an acceptable model fit of the struc-tural model (GFI = 0.80, CFI = 0.72, RMSEA = 0.05, NFI = 0.90) [28,29].

Discussion

The conceptions of and strategies to learning medicine One of the findings in our study was that medical stu-dents holding“Preparing for Testing” COLM, was posi-tively associated with adopting surface strategies to learning, and negatively associated with adopting deep strategies to learning. Similar to our study results, previ-ous studies found that undergraduate students holding lower-level conception of learning tended to employ sur-face strategies to learning [11, 16]. Liang et al. also re-ported that computer science-major undergraduate students with lower-level conceptions of learning tended to employ surface strategies to learning computer sci-ence [17]. These results imply that students with lower-level conceptions of learning (“Memorizing”, “Preparing for testing”, “Practicing Tutorial Problems”, and “Skills Acquisition”) aimed at adopting surface approaches (the motives of “Fear of Failure” and “Aim for Qualification”, and the strategies of “Minimizing Scope of Study” and “Memorization”) to learning knowledge.

The other interesting finding was that medical stu-dents with “Skills Acquisition”, as one of the basic-level conceptions of learning, was positively associated with using deep strategies to learning. The finding contradicts

several previous studies pointing out that basic-level conceptions of learning were associated with surface strategies to learning [11,16,17].

An explanation may account for this finding. Starting from the first day of receiving medical education, med-ical students are expected to learn medmed-ical knowledge, to acquire clinical skills and to cultivate professional atti-tudes [30]. Assessments of clinical competencies, such as observing senior physicians’ professional behaviors in clinical encounters, discussion of clinical cases, and feed-back from multiple sources, are necessary and important [31]. Successful physicians combine learning medical knowledge, acquiring clinical skills and cultivating profes-sional attitudes with the flexibility required to implement competencies in the clinical encounter in which clinical contexts may change. Therefore, deep approaches to learning, including deep motivation and deep strategies, may maximize learning outcomes for learning medical knowledge, acquiring clinical skills and cultivating profes-sional attitudes. As a result, medical students holding the conception of learning medicine as “Skills Acquisition” may encourage their deep strategies to learning medicine for a better learning outcome.

The other explanation for accounting for this result should refer to the items of “Skills Acquisition” in the COLM questionnaire (Appendix 1). After factor ana-lysis, only three (SA 3, SA 4 and SA 6) of the five items representing “Skills Acquisition” were included in the following SEM model. Obviously, two of the Table 2 The CFA analysis for the modified Approaches to Learning Medicine (mALM) questionnaire. (N = 272)

Construct and Measurement Items Factor loading t Statistics

(p Value)

CR AVE Alpha Value

Deep Strategy (DS) Mean = 3.07, SD = 0.52 – – 0.95 0.79 0.88 DS 1 (1) 0.68 – – – – DS 3 (3) 0.91 13.34 p < .01 – – – DS 4 (4) 0.92 13.48 p < .01 – – – DS 5 (5) 0.78 11.71 p < .01 – – – DS 7 (7) 0.62 9.54 p < .01 – – – Surface Strategy (SS) Mean = 1.88, SD = 0.75 – – 0.77 0.52 0.73 SS 2 (10) 0.75 – – – – SS 3 (11) 0.75 8.88 p < .01 – – – SS 4 (12) 0.59 7.88 p < .01 – – –

Table 3 P e ar so n’ s co rrelation coeff icient b e tween the C on ceptio ns of Le ar nin g an d St ra te g ie s to Le arni n g ,a n d b e twe e n the w ei ghted g ra de and Strat e g ie s to Lea rning Me d icine Weigh ted Gra de Adva nced-l evel COLM Bas ic-level COLM IOK A U SNW C M PT PTP SA Deep Strateg y 0.11 (p = .08) 0.13 (p = .03 ) 0 .1 4 (p = .02) 0. 18 (p < .01) 0.16 (p = .01) 0.28 (p < .01) − 0.06 (p = .33) − 0.23 (p < .01) 0.16 (p = .0 1) 0.30 (p < .01) Surf ace Strat egy − 0.13 (p = .0 3) 0.02 (p =. 7 3 ) − 0.06 (p = .30) − 0.03 (p = .62) − 0.07 (p = .28) − 0.13 (p = .03) 0.24 (p < .01) 0.43 (p < .0 1) 0.09 (p =. 1 4 ) − 0.13 (p =. 0 3 ) Abbreviation: COLM Conceptions of Learning Medicine, IOK Increase One ’s Knowledge, A Applying, U Understanding, SNW Seeing in a New Way, C Communication, M Memorizing, PT Preparing for Testing, PTP Practicing Tutorial Problems, SA Skills Acquisition

three items (SA 3 and SA 4) clearly relate learning medicine to applying the skills they learned to medical practice, implying that “Skills Acquisition” may be a factor of advanced-level COLM. Therefore, the partici-pants who got a higher score in “Skills Acquisition”, potentially relating learning medicine to application to medical practice as indicated by SA 3 and SA 4, may use deep strategies to learning medical humanities. In addition, this finding also highlights that relocation of “Skills Acquisition” to be a factor of advanced-level COLM, and the items of “Skills Acquisition” used in the COLM questionnaire should be further deliber-ated. If “Skills Acquisition” is to mean the skills of learning medicine, it should remain in basic-level COLM. In comparison, if “Skills Acquisition” is to mean that learning medicine is to learn the skills ap-plied to medical practice, it should belong to advanced-level COLM. The items of “Skills Acquisi-tion” should be modified accordingly.

Medicine, different from other disciplines such as biol-ogy, chemistry, or physics, particularly emphasizes the application of knowledge. However, unlike previous studies [11, 16], our results did not show the significant association between the advanced-level conception of “Applying” and strategies to learning. The insignificant

association in this study may be attributed to the dual perspective of the “Applying” concept [7, 16]. On one hand, “Applying” implied that applying knowledge is based on knowing how to use the knowledge [32], and hence is considered as basic-level conception of learning. On the other hand,“Applying” can be interpreted as ap-plying knowledge to practical situation, and thus catego-rized into advanced-level conception of learning [7]. Potentially due to the first-year medical students’ dual perspective of “Applying”, the association between “Ap-plying” and the strategies to learning may not be signifi-cant. In addition, the first-year medical students in Taiwan at this point have not yet immersed themselves to basic or clinical medicine, thus have not yet devel-oped their conception of learning medicine about “Ap-plying”. As a result, the association between “Applying” and the strategies to learning medicine cannot be determined.

The strategies to learning medicine and learning outcomes in medical humanities

Several previous studies have reported that surface ap-proaches to learning were negatively associated with learn-ing outcomes [18,25,33]. Newble et al. also showed that medical students adopting surface approaches to learning, Fig. 1 Diagram of structural equation model of the relationships between conceptions of learning, strategies to learning, and learning outcomes

including surface motives and surface strategies mainly learned by rote memorizing and reproducing the material [34]. Liang et al. found that the house officers with surface strategies to learning medicine were more likely to get un-satisfactory learning outcomes [22]. There are two reasons to account for this phenomenon:

Firstly, medical humanities is considered far more multidisciplinary than medicine. Medical students’ ap-proaches to learning did not significantly change in dif-ferent clinical rotations [35] partly because medical students may see medicine as a single field. In compari-son, medical humanities is composed of a variety of disciplines. Rote-like learning for memorizing the know-ledge of some of the disciplines may be necessary for in-tegrating it into medical training. Secondly, because medical humanities remained an unappealing part of medical education [2,6], it is common that medical stu-dents, usually with adaptive learning strategies and moti-vations [22], employ surface strategies for learning medical humanities which is considered unappealing in medical curriculum.

Previous studies pointed out that deep strategies and motivations to learning were a predominant fac-tor affecting medical students’ academic performance [18, 20, 21]. Interestingly, our results did not echo previous studies on the significant association be-tween deep strategies to learning medicine and learn-ing outcomes. One possible reason is that uslearn-ing medical students’ weighted grades in the medical hu-manities course as a learning outcome may not en-tirely reflect its association with deep strategies to learning. The other possible reason is that the med-ical humanities course in this study actually did not induce deep strategies to learning. Many students criticized that medical humanities courses cannot dir-ectly provide them with tangible skills that are useful in clinical practice, and hence see them as unappeal-ing [2]. Accordingly, medical students tend to avoid using deep strategies for learning medical humanities which is considered unappealing and useless in clin-ical practice.

Strengths and limitations

Previous research has reported close relationships between students’ conceptions of learning and approaches to learn-ing. Nevertheless, few of them have been focused on exam-ining medical students’ learning process and learning outcomes in medical humanities. Our study firstly exam-ined the conceptions of learning, the strategies of learning, and the learning outcomes in medical humanities. Further-more, we used SEM which is with great strength to provide a summary evaluation of mathematical models involving a lot of linear equations. Nevertheless, several limitations might confine the academic merits of the study results.

First, this was a single-center study, and only first-year medical students were included. In addition, the medical students enrolled in this medical school have done the best in the Advanced Subjects Exam (also known as the University Entrance Exam) or the General Scholastic Ability Test as compared to those enrolled in other medical schools in Taiwan. Accordingly, the generalizability of the study results to other medical students may not be convincing.

Second, several potential factors, such as personal characteristics factors, social and cultural factors, were not included in the structural model. Consequently, the structural model could only explain the differences in medical students’ conceptions of learning medicine and strategies to learning medicine.

Third, the medical students’ learning outcome for medical humanities was measured using weighted grades including a variety of assessments on class participation, written examination, feedback on ex-periential learning, and a term paper. However, weighted grades in the medical humanities course only represented the medical students’ overall learn-ing performance of medical humanities, which may not represent students’ actual self-directed learning progress (e.g. engagement in extra-curricular activ-ities). Future research should examine the structural model in different indicators for learning outcomes of medical humanities.

Conclusions

Although the importance of incorporating medical humanities to both undergraduate and post-graduate medical education is continuously emphasized, ical humanities remained an unappealing part in med-ical curriculum. This study showed that a medmed-ical student’s conceptions of learning, such as preparing for testing and skills acquisition, were significantly as-sociated with the strategies to learning medicine, and medical students’ learning outcomes in the medical humanities course were inversely associated with the surface strategies to learning. Therefore, medical edu-cators should wisely employ teaching strategies to increase students’ engagement with deep and self-directed learning strategies, and to avoid using surface learning strategies in the medical humanities course in order to achieve better learning outcomes. By achieving better learning outcomes in medical human-ities, medical students are expected to shift from only handling the diseases to seeing a whole sick person, and responding appropriately to complex clinical con-texts. Future research is suggested to investigate med-ical students’ learning process and learning outcome surrounding medical humanities using a larger sample of medical students.

Appendix 1

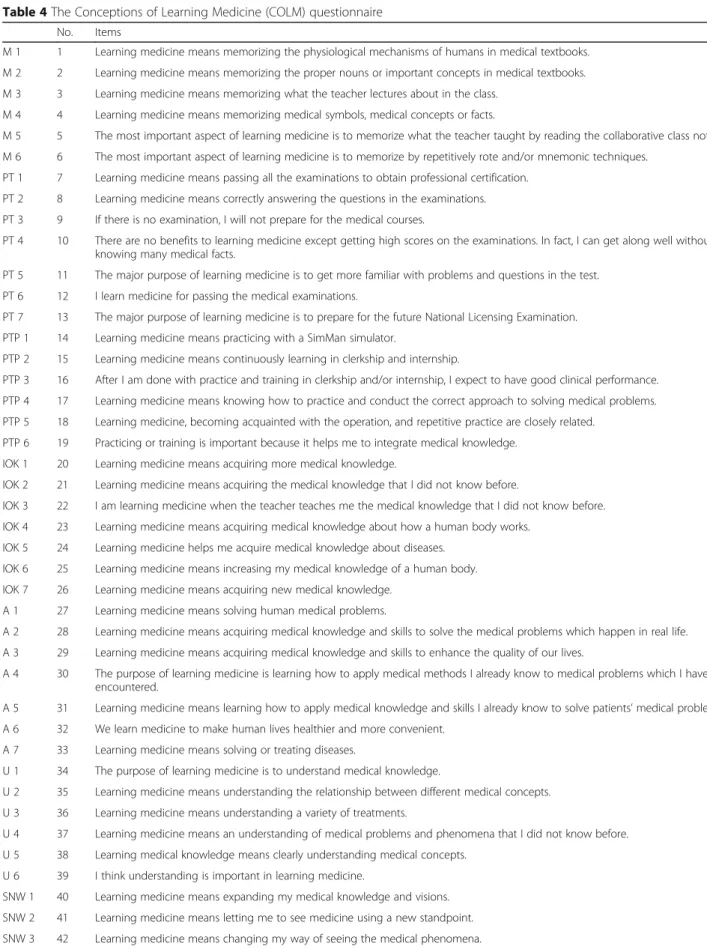

Table 4 The Conceptions of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire

No. Items

M 1 1 Learning medicine means memorizing the physiological mechanisms of humans in medical textbooks. M 2 2 Learning medicine means memorizing the proper nouns or important concepts in medical textbooks. M 3 3 Learning medicine means memorizing what the teacher lectures about in the class.

M 4 4 Learning medicine means memorizing medical symbols, medical concepts or facts.

M 5 5 The most important aspect of learning medicine is to memorize what the teacher taught by reading the collaborative class notes. M 6 6 The most important aspect of learning medicine is to memorize by repetitively rote and/or mnemonic techniques.

PT 1 7 Learning medicine means passing all the examinations to obtain professional certification. PT 2 8 Learning medicine means correctly answering the questions in the examinations. PT 3 9 If there is no examination, I will not prepare for the medical courses.

PT 4 10 There are no benefits to learning medicine except getting high scores on the examinations. In fact, I can get along well without knowing many medical facts.

PT 5 11 The major purpose of learning medicine is to get more familiar with problems and questions in the test. PT 6 12 I learn medicine for passing the medical examinations.

PT 7 13 The major purpose of learning medicine is to prepare for the future National Licensing Examination. PTP 1 14 Learning medicine means practicing with a SimMan simulator.

PTP 2 15 Learning medicine means continuously learning in clerkship and internship.

PTP 3 16 After I am done with practice and training in clerkship and/or internship, I expect to have good clinical performance. PTP 4 17 Learning medicine means knowing how to practice and conduct the correct approach to solving medical problems. PTP 5 18 Learning medicine, becoming acquainted with the operation, and repetitive practice are closely related.

PTP 6 19 Practicing or training is important because it helps me to integrate medical knowledge. IOK 1 20 Learning medicine means acquiring more medical knowledge.

IOK 2 21 Learning medicine means acquiring the medical knowledge that I did not know before.

IOK 3 22 I am learning medicine when the teacher teaches me the medical knowledge that I did not know before. IOK 4 23 Learning medicine means acquiring medical knowledge about how a human body works.

IOK 5 24 Learning medicine helps me acquire medical knowledge about diseases. IOK 6 25 Learning medicine means increasing my medical knowledge of a human body. IOK 7 26 Learning medicine means acquiring new medical knowledge.

A 1 27 Learning medicine means solving human medical problems.

A 2 28 Learning medicine means acquiring medical knowledge and skills to solve the medical problems which happen in real life. A 3 29 Learning medicine means acquiring medical knowledge and skills to enhance the quality of our lives.

A 4 30 The purpose of learning medicine is learning how to apply medical methods I already know to medical problems which I haven’t encountered.

A 5 31 Learning medicine means learning how to apply medical knowledge and skills I already know to solve patients’ medical problems. A 6 32 We learn medicine to make human lives healthier and more convenient.

A 7 33 Learning medicine means solving or treating diseases.

U 1 34 The purpose of learning medicine is to understand medical knowledge.

U 2 35 Learning medicine means understanding the relationship between different medical concepts. U 3 36 Learning medicine means understanding a variety of treatments.

U 4 37 Learning medicine means an understanding of medical problems and phenomena that I did not know before. U 5 38 Learning medical knowledge means clearly understanding medical concepts.

U 6 39 I think understanding is important in learning medicine.

SNW 1 40 Learning medicine means expanding my medical knowledge and visions. SNW 2 41 Learning medicine means letting me to see medicine using a new standpoint. SNW 3 42 Learning medicine means changing my way of seeing the medical phenomena.

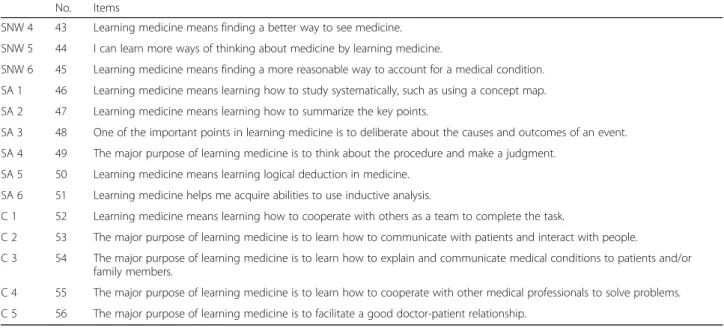

Table 4 The Conceptions of Learning Medicine (COLM) questionnaire (Continued)

No. Items

SNW 4 43 Learning medicine means finding a better way to see medicine. SNW 5 44 I can learn more ways of thinking about medicine by learning medicine.

SNW 6 45 Learning medicine means finding a more reasonable way to account for a medical condition. SA 1 46 Learning medicine means learning how to study systematically, such as using a concept map. SA 2 47 Learning medicine means learning how to summarize the key points.

SA 3 48 One of the important points in learning medicine is to deliberate about the causes and outcomes of an event. SA 4 49 The major purpose of learning medicine is to think about the procedure and make a judgment.

SA 5 50 Learning medicine means learning logical deduction in medicine. SA 6 51 Learning medicine helps me acquire abilities to use inductive analysis.

C 1 52 Learning medicine means learning how to cooperate with others as a team to complete the task.

C 2 53 The major purpose of learning medicine is to learn how to communicate with patients and interact with people.

C 3 54 The major purpose of learning medicine is to learn how to explain and communicate medical conditions to patients and/or family members.

C 4 55 The major purpose of learning medicine is to learn how to cooperate with other medical professionals to solve problems. C 5 56 The major purpose of learning medicine is to facilitate a good doctor-patient relationship.

Abbreviation List: M Memorizing, PT Preparing for Testing, PTP Practicing Tutorial Problems, IOK Increasing One’s Knowledge, A Applying, U Understanding, SNW Seeing in a New Way, SA Skills Acquisition, C Communication

Abbreviations

AVE:average variance explained; CFA: confirmatory factor analysis; CFI: comparative fit index; COLM: Conceptions of Learning Medicine; CR: composite reliability; GFI: goodness of fit index; mALM: modified Approaches to Learning Medicine; NFI: normed fit index; RMSEA: root-mean-square error of approximation; SEM: structural equation modeling

Acknowledgements Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

CYC: literature review, manuscript drafting, manuscript editing. LJC: study design, statistical analysis, funding support. HHY: building theoretical framework, study design, data interpretation. CTS: manuscript editing. LKH: statistical analysis, manuscript drafting, manuscript editing. CYY: building theoretical framework, study design, data collection, manuscript editing, funding support, submission approval. TCC: manuscript editing, submission approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the“Institute for Research Excellence in Learning Sciences” of National Taiwan Normal University from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan, and also by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST 104 –2511-S-002-007-MY2, MOST 105–2628-S-011-002-MY3, MOST 106–2628-S-003-002-MY3 and MOST 108–2634-F-002-023). The funders did not have any involvement in the data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of this article, and decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analyzed for this study is available from the co-corresponding authors, Dr. Kuan-Han Lin and Dr. Yen-Yuan Chen, by qualified researchers on a reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee in National Taiwan University (201505HS002). Participants’ written consents to join this study were obtained.

Appendix 2

Table 5 The Modified Approaches to Learning Medicine (mALM) questionnaire

No. Items

Deep Strategy DS 1 RI 1 1 When learning medicine, I try to relate what I have learned in one subject to what I have learned in others.

DS 2 RI 2 2 When learning medicine, I like to create a new plausible theory for helping me to summarize a lot of disorganized content.

DS 3 RI 3 3 When learning medicine, I try to find out the relationships between what I have learned. DS 4 RI 4 4 When learning new subjects in medicine, I try to relate to those I have learned. DS 5 U 1 5 When reading medical textbooks, I try to understand the meaning of the content. DS 6 U 2 6 When learning medicine, I try to understand the content of the medical courses. DS 7 U 3 7 When learning medicine, I use systemic ways to learn.

DS 8 U 4 8 When learning medicine, I read original textbooks or use online resources for better understanding of the content.

SS 1 MSS 1 9 When learning medicine, the items not tested in the exams are meaningless to me. SS 2 MSS 2 10 When learning medicine, I spend as little time on studying medicine as I can, as long as I feel

that I can pass the exams. There are many other interesting things to do.

SS 3 MSS 3 11 When learning medicine, I find out the contents which are worth spending time to study simply because I do not want to spend time and energy on the unrelated content.

Surface Strategy SS 4 MSS 4 12 When learning medicine, we do not need to be familiar with all the contents simply because there are so many exams we need to pass, and so many subjects we need to learn.

SS 5 MSS 5 13 When learning medicine, I hope that the teacher can give us what will be tested in the exams, for us to better prepare for the exams.

SS 6 M 1 14 When learning medicine, I practice rote memorization of the content until I firmly memorize all of the content.

SS 7 MSS 6 15 I feel that the best way to get good grades in medical exams is the rote the answers of similar questions.

SS 8 MSS 7 16 I find that to memorize the content of medical subjects by rote makes me achieve good grades on exams, rather than to understand them.

SS 9 M 2 17 When learning medicine, I am very focused on those which will be tested in exams, and I memorize them by rote.

SS 10 M 3 18 When learning medicine, I use lecture notes and aids for National Licensing Exams as important learning guides.

SS 11 M 4 19 When learning medicine, I try to improve my memorization by repeated rote. Abbreviation List: DS Deep Strategy, SS Surface Strategy, RI Relating Ideas, U Understanding, MSS Minimizing Scope of Study, M Memorization

Consent for publication

This study does not contain any individual person’s data in any form. Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Author details

1Department of Pediatrics, National Taiwan University Hospital, #7, Rd. Chong-Shan S, Taipei 10002, Taiwan.2Department of Medical Education, National Taiwan University Hospital, #7, Rd. Chong-Shan S, Taipei 10002, Taiwan.3Program of Learning Sciences, National Taiwan Normal University, #162, Rd. Heping E. Sec. 1, Taipei 10610, Taiwan.4Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Bioethics, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, #1, Rd. Ren-Ai sec. 1, Taipei 10051, Taiwan.5Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, #7, Rd. Chong-Shan S, Taipei 10002, Taiwan.6Department of Healthcare Administration, Asia University, #500, Rd. Liou-Feng, Wufeng, Taichung 41354, Taiwan.

Received: 10 June 2019 Accepted: 28 October 2019

References

1. Medical humanities [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_humanities]. 2. Shapiro J, Coulehan J, Wear D, Montello M. Medical humanities and their

discontents: definitions, critiques, and implications. Acad Med. 2009;84(2): 192–8.

3. Cassell EJ. The place of the humanities in medicine. Hastings-on-Hudson. NY: The Hastings Center; 1984.

4. Bolton G. Medicine, the arts, and the humanities. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):93–4. 5. General Medical Council U: Tomorrow's Doctors. London, UK: General

Medical Council, UK; 1993.

6. Wear D, Zarconi J. A humanities-based capstone course in medical education: an affirming and difficult look back. Journal for Learning through the Arts. 2006;2(1):8.

7. Tsai CC. Conceptions of learning science among high school students in Taiwan: a phenomenographic analysis. Int J Sci Educ. 2004;26(14):1733–50. 8. Sadi O, Dagyar M. High school Students' epistemological beliefs,

conceptions of learning, and self-efficacy for learning biology: a study of their structural models. Eurasia J Math Sci T. 2015;11(5):1061–79. 9. Duarte AM. Conceptions of learning and approaches to learning in

Portuguese students. High Educ. 2007;54(6):781–94.

10. Newble DI, Clarke RM. The approaches to learning of students in a traditional and in an innovative problem-based medical-school. Med Educ. 1986;20(4):267–73.

11. Chiou GL, Liang JC, Tsai CC. Undergraduate Students' conceptions of and approaches to learning in biology: a study of their structural models and gender differences. Int J Sci Educ. 2012;34(2):167–95.

12. Vermunt JD, Vermetten YJ. Patterns in student learning: relationships between learning strategies, conceptions of learning, and learning orientations. Educ Psychol Rev. 2004;16(4):359–84.

13. Biggs J: Approaches to Learning: Nature and Measurement of. In: The International Encyclopedia of Education. Edited by Postlethwaite TN, Husen T, 2nd edn: Pergamon press; 1994: 319–322.

14. Lin YC, Liang JC, Tsai CC. The relationships between epistemic beliefs in biology and approaches to learning biology among biology-Major University students in Taiwan. J Sci Educ Technol. 2012;21(6):796–807. 15. Lin YH, Liang JC, Tsai CC. Effects of different forms of physiology instruction

on the development of students' conceptions of and approaches to science learning. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012;36(1):42–7.

16. Lee MH, Johanson RE, Tsai CC. Exploring Taiwanese high school students' conceptions of and approaches to learning science through a structural equation modeling analysis. Sci Educ. 2008;92(2):191–220.

17. Liang JC, Su YC, Tsai CC. The assessment of Taiwanese college Students' conceptions of and approaches to learning computer science and their relationships. Asia-Pac Educ Res. 2015;24(4):557–67.

18. Mattick K, Dennis I, Bligh J. Approaches to learning and studying in medical students: validation of a revised inventory and its relation to student characteristics and performance. Med Educ. 2004;38(5):535–43. 19. Ward PJ. First year medical students' approaches to study and their

outcomes in a gross anatomy course. Clinical anatomy (New York, NY). 2011;24(1):120–7.

20. McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC, Sproston KA. Clinical experience, performance in final examinations, and learning style in medical students: prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316(7128):345–50.

21. McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC. Intercalated degrees, learning styles, and career preferences: prospective longitudinal study of UK medical students. BMJ. 1999;319(7209):542–6.

22. Liang JC, Chen YY, Hsu HY, Chu TS, Tsai CC. The relationships between the medical learners' motivations and strategies to learning medicine and learning outcomes. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1497373.

23. Snelgrove S, Slater J. Approaches to learning: psychometric testing of a study process questionnaire. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(5):496–505.

24. Chamorro-Premuzic T, Furnham A. Personality, intelligence and approaches to learning as predictors of academic performance. Pers Indiv Differ. 2008; 44(7):1596–603.

25. Reid WA, Duvall E, Evans P. Relationship between assessment results and approaches to learning and studying in year two medical students. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):754–62.

26. Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988;16(1):74–94.

27. Farrell AM, Rudd J: Factor analysis and discriminant validity: A brief review of some practical issues. In: 2009: Anzmac; 2009.

28. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL: Multivariate data analysis, vol. 5: Prentice hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 1998.

29. Arbuckle J: Amos users' guide, version 3.6: Marketing Division, SPSS Incorporated; 1997.

30. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203–7. 31. Swanwick T, Chana N. Workplace-based assessment. Br J Hosp Med (Lond).

2009;70(5):290–3.

32. Eklund-Myrskog G. Students' conceptions of learning in different educational contexts. High Educ. 1998;35(3):299–316.

33. Newble DI, Entwistle NJ, Hejka EJ, Jolly BC, Whelan G. Towards the identification of student learning problems: the development of a diagnostic inventory. Med Educ. 1988;22(6):518–26.

34. Newble DI, Entwistle NJ. Learning styles and approaches: implications for medical education. Med Educ. 1986;20(3):162–75.

35. Emilia O, Bloomfield L, Rotem A. Measuring students' approaches to learning in different clinical rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:114.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.