Efficacy of Integrating Information Literacy Education

Into a Women’s Health Course on Information

Literacy for RN-BSN Students

Ya-Lie Ku · Sheila Sheu* · Shih-Ming Kuo**ABSTRACT: Information literacy, essential to evidences-based nursing, can promote nurses’ capability for life-long learning. Nursing education should strive to employ information literacy education in nursing curricula to improve information literacy abilities among nursing students. This study explored the effectiveness of information literacy education by comparing information literacy skills among a group of RN-BSN (Registered Nurse to Bachelors of Science in Nursing) students who received information literacy education with a group that did not. This quasi-experimental study was conducted during a women’s health issues course taught between March and June 2004. Content was presented to the 32 RN-BSN students enrolled in this course, which also taught skills on searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting information. At the beginning and end of the program, 75 RN-BSN student self-evaluated on a 10 point Likert scale their attained skills in searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting information. Results identified no significant differences between the experimental (n = 32) and control groups (n = 43) in terms of age, marital status, job title, work unit, years of work experience, and information literacy skills as measured at the beginning of the semester. At the end of the semester during which content was taught, the information literacy of the experimental group in all categories, with the exception of information presentation, was significantly improved as compared to that of the control group. Results were especially significant in terms of integrating, analyzing, and applying skill categories. It is hoped that in the future nursing students will apply enhanced information literacy to address and resolve patients’ health problems in clinical settings.

Key Words: information education, information literacy, nursing curricula, nursing students.

Introduction

Technological advances and the global reach of the Internet have ushered in a new era for higher education. Nurses are increasingly required to acquire and analyze information from large volumes of literature and then apply this information in clinical practice. Information lit-eracy is essential to evidence-based nursing (Lee, Chen, & Chen, 2001; Pierce, 2000; Shorten, Wallace, & Crookes, 2001) and to the cultivation of nurses with specialist skills in informatics (Chuang & Hung, 2004). Tanner, Pierce, and Pravikoff (2004) reported that information literacy skill

represented a key criterion of nursing informatics com-petency. Additionally, information literacy can promote life-long learning among nurses (Cheek & Doskatsch, 1998; Hsu, 2002; Shorten et al., 2001). Although the litera-ture highlights the importance of information literacy for nursing, few nursing schools have considered integrating information literacy education into their curriculum. Also, the definition of information literacy varies in the literature and few studies have been published on the effectiveness of an information literacy education taught by nursing faculty (as opposed to a librarian) to improve the information liter-acy of nursing students.

RN, MSN, Doctoral Candidate, Instructor, School of Nursing, Fooyin University; *RN, PhD, Professor, School of Nursing, & Vice President; **MS, Instructor, Science Education Center.

Received: October 18, 2005 Revised: August 14, 2006 Accepted: January 23, 2007

Address correspondence to: Sheila Sheu, No. 151, Chin-Hsueh Rd., Ta-Liao Rural Township, Kaohsiung County 83102, Taiwan, ROC. Tel: 886(7)781-1151 ext. 451; E-mail: aa119@mail.fy.edu.tw

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to explore the effective-ness of an information literacy education by comparing the level of information literacy in a group of RN-BSN stu-dents who received an information education against that in another group of RN-BSN students who had not.

Literature Review

The literature was reviewed to obtain a definition of information literacy and to better understand the direction and findings of studies on information education. The review found numerous studies and articles published be-tween 1998 and 2005 investigating and discussing infor-mation education pertinent to nursing.

Information literacy

Cheek and Doskatsch (1998) categorized information literacy into the four areas of using libraries, reading pro-fessional literature, using computers, and developing life-long learning habits. In the area of library usage, Verhey (1999) broadly defined information literacy as the ability to use information resources, e.g., articles and journals, li-braries, and nursing department learning centers, to com-plete assignments. In addition to an ability to search in-formation resources, inin-formation literacy also embraces knowledge of the methodology by which the benefits and barriers of information can be obtained as well as the ability to utilize information resources after graduation (Verhey, 1999). Wallace, Shorten, Crookes, McGurk, and Brewer (1999) defined information literacy as the ability to handle, evaluate, and apply information using critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Pierce (2000) argued that information literacy is critical to achieving optimal nursing decisions based on searching, reviewing, and inte-grating research information. Furthermore, Chuang and Hung (2004) proposed that the objective of nursing infor-mation literacy is the management of nursing inforinfor-mation for its implementation into nursing care.

Shorten et al. (2001) defines information literacy as the ability to understand, handle, review, and evaluate liter-ature. Hsu (2002) further argued that information literacy should encompass literacy in the areas of language, com-puters, the media, and the Internet. Language literacy is the general ability to listen, speak, read, and write. In terms of computer usage, Cole (2004) suggested nursing schools develop information literacy software for nursing students focused on enhancing computer literacy. Computer literacy

is the ability to understand and utilize computer hardware and software (Hsu, 2002). Although information literacy is defined in the literature in various ways, Saranto and Hovenga (2004) noted that the concept of information liter-acy, with the exception of that related to computers, has not been widely appreciated or developed in the medical and nursing community. Rather than focusing on computer lit-eracy, the author chose to define information literacy in this study as the ability to search and screen, integrate, ana-lyze, apply, and present information. “Search and screen” is defined as the ability to select information, sources, and ranges for literature searches accurately. Ability to inte-grate information is defined as the ability to simplify and unite information. Ability to analyze information is de-fined as the ability to interpret and critique information. Ability to apply information is defined as the ability to uti-lize information to solve problems and publish informa-tion. Ability to present information is defined as the ability to use figures, tables, images, video-equipments, and com-puter software such as Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.

Information education

Nursing informatics began in the United States around 1992, with the first masters’ and PhD programs established in the University of Maryland (Chuang & Hung, 2004). In Taiwan, the National Taipei College of Nursing was the first school to build an innovative medi-cal and nursing informatics curriculum in problem-based learning (Wen & Duh, 1999). Chang Gung Univer-sity was the second school to establish an nursing infor-matics program (Chuang & Huang, 2004). Nevertheless, as the nursing informatics curriculum in Taiwan remains inadequate, innovative nursing information curricula still represent a pressing need in nursing education (Wen & Duh, 1999).

Examples of various studies done on information lit-eracy education in the nursing field include: A study, based on the suggestions of the National Informatics for Nursing Education and Practice (1997), defined information liter-acy education as the process of integrating information technology and knowledge into the nursing curriculum (cited in McNeil et al., 2003). An on-line survey involving 226 nursing college students found that most online schools required of their students only rudimentary word processing and e-mail skills (McNeil et al., 2003). Pierce (2000), investing the degree of informational literacy among nursing teachers and students, found both groups

lack adequate knowledge in utilizing Internet resources and in applying research to nursing practices.

Liu and Shieh (2000) determined that 50% of nurses in Taiwan were incapable of searching for information and lacked experience using the Internet. Chiu (2000) and Chuang and Chuang (2003) also identified Taiwanese nurses as having inadequate computer usage skills. In the Chiu (2000) study, researchers delivered training to 15 administration nurses and 165 staff nurses on Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Access, and Internet applications once a week for 6 weeks. Results, as reported by the researchers, at-tained application skill increases of 70-80 percent for administration nurses and 80-90 percent for staff nurses. Chuang and Chuang also found positive attitudes toward using common applications such as Word, PowerPoint, and Medline among 160 RN-BSN students. This same research found that attitude toward computer use had a sig-nificant, positive correlation to marital status, management role, and Internet usage but no significant relationship to years of work experience. Huang (2004) identified that nurses who were more highly motivated and self-reliant in terms of resolving computer problems experienced less anxiety when using computers and tended to use comput-ers for longer periods of time.

Dorner, Taylor, and Hodson-Carlton (2001) applied a tiered approach to develop a cooperative program linking librarians and faculty targeted to enhance nursing student research abilities (including information literacy skills) at Ball State University. Similarly, Rosenfeld, Salazar-Riera, and Vieira (2002) leveraged cooperation between nursing faculty and library staff to develop a web-based tutorial to upgrade nursing student literacy skills. Guillot, Stahr, and Plaisance (2005) also designed a dedicated online virtual environment at Southeastern Louisiana University that brought together the expertise of nursing faculty, librarians, and research consultants to increase nursing student litera-ture search proficiencies. A large majority (91%) of 100 nursing students responded that they were very satisfied with instructions received by e-mail and perceived them-selves more likely to find relevant literature as a result.

Nevertheless, this emphasis on rudimentary computer skills in the United States and Taiwan does not represent a true focus on information literacy. In this information era, nursing education should help students develop the skills critical to information literacy beyond simple computer skills. Cheek and Doskatsch (1998) explored the relation-ship between information literacy and the nursing

sional that cultivates information literacy-related profes-sional nursing attitudes, skills, and knowledge. Shorten et al. (2001) demonstrated that curricula with coursework covering information literacy turn out students with better information literacy than those without such coursework.

Two nursing schools, the University of Wollongong in Australia and San Francisco State University in the United States, have already integrated information education into their curriculum. A study conducted at the former demon-strates the curriculum has effectively improved students’ cognition and affection (Wallace et al., 1999). The ef-fectiveness of the information literacy curriculum at the School of Nursing, San Francisco State University, was evaluated based on the perspectives of nursing students and teachers (Verhey, 1999) and levels of information literacy were compared between two cohort students groups, one in 1992 (N = 142) and the other in 1996 (N = 145). For nursing students, the ability to search for information resources (articles and journals) improved significantly for the two cohort groups, with utilization rates for CINAHL (Cumu-lative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature) sig-nificantly enhanced (achieving nearly 37.7%). However, the latter cohort (N = 145) did not search for information efficiently and identified lack of time, knowledge of avail-able resources, and unfamiliarity with the library as barri-ers to effective information searching. Additionally, no significant difference in information literacy among nurs-ing teachers was found between the two cohort groups. Wallace, Allison, and Crookes (2000) also reported a lack of significant difference in information literacy between nursing students who participated in an information liter-acy program (N = 55) and those who did not (N = 72).

Most literature on information literacy has focused on either the application of information technology/computer skills or the environment in which these activities occur. Few studies have focused on search strategies or on the screening, integration, analysis, and application of in-formation. Oftentimes nursing students have difficulties searching and identifying articles as well as distinguishing professional articles from articles intended for the general public. Also, in facing the large volumes of literature avail-able, nursing students often do not understand how to inte-grate information in an appropriate way or conduct an in depth analysis. Finally, nursing students have little chance to apply the information learned in the courses in real case scenarios. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to de-velop nursing student information literacy in terms of

searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting information.

Methods

This study developed a method by which information literacy education could be integrated into a professional nursing training course. A pilot study in the area of women’s health issues that targeted 7 RN-BSN students increased sig-nificantly student information literacy abilities (searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and present-ing information) through a formal information literacy train-ing program held from September 2003 to January 2004. This quasi-experimental study utilized information literacy education as an intermediate variable to compare levels of information literacy between experimental and control groups. A convenient sample of RN-BSN students (N = 100) enrolled in a 3-years nursing program at a university in southern Taiwan was invited to participate, with a return rate for valid questionnaires approaching 75%. Experimental group students (n = 32) were assigned to attend a women’s health course which incorporated an information literacy education component. The control group (n = 43)

parti-cipated in a course entitled “Marriage and Family”, which did not include literacy education training. Nursing stu-dents in both groups were tested two weeks prior to and fol-lowing the semester, which ran from March through June 2004.

Information literacy education in this course comprised training in the skills required to effectively search and screen the literature for issues in women’s health. Based on infor-mation obtained by searching and screening books, journals, and the Internet, the investigator assisted nursing students to integrate obtained information to identify principal women’s health issues and suggest preventive strategies, analyze the similarities and differences in the information obtained from the three sources, and interpret and critique information from a feminist point of view. In this course, nursing stu-dents were required to analyze one woman case, identify the patient’s health issue, and apply strategies based on litera-ture-based research to address the health issue and prob-lem-solving skills successfully. Students were further en-couraged to publish their final reports. Additionally, skills needed to present relevant information were taught at the school information center, which provided free training in Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. Table 1 lists the activities

Table 1.

Information Literacy and Teaching Activities Included in Women’s Health Information Literacy Education

Information literacy Teaching activities involved in women’s health information education

Searching and screening information

1. Provide access to resources to search information related to women’s health; e.g., CINAHL, MEDLINE, ERIC, Chinese theses and journals;

2. Teach how to differentiate among information from various sources (e.g., books, journals, and the Internet), and how such relates to women’s health as presented in gynecology textbooks; 3. Guide students to narrow down information to focus on a particular women’s health issue. Integrating information 1. Teach students to integrate information on a particular women’s health issue from books;

2. Teach students to integrate information on a particular women’s health issue from journals; 3. Teach students to integrate information on a particular women’s health issue from the Internet. Analyzing information 1. Teach methods to compare similarities and differences in information in books, journals, the

Internet on a particular women’s health issue;

2. Apply a gender perspective to interpret and critique information on a particular women’s health issue from books, journals, and the Internet;

3. Apply a feminist point of view in interpreting and critiquing information on a particular women’s health issue from books, journals, and the Internet.

Applying information 1. Analyze a case dealing with a particular women’s health issue and make generalizations regarding the condition;

2. Design problem-solving strategies addressing the case based on information from books, journals, and the Internet;

3. Refer to papers published in women’s health journals. Presenting information 1. Teach 18 Word techniques in the school information center;

2. Teach 18 Excel techniques in the school information center; 3. Teach 18 PowerPoint techniques in the school information center.

involved in information literacy education training in the women’s health course designed for this study.

The scale used to measure information literacy of RN-BSN students in this study was developed by the au-thors and validated by educational experts in panel discus-sion. There were 6 items in the searching and screening section, 3 in the integrating section, 5 in the analyzing sec-tion, 6 in the application secsec-tion, and 3 in the presenting section. Nursing students in both groups used a 10-point Likert scale for self-evaluation of information literacy skills before and after the semester, which ran from March to June 2004. Table 2 lists the 23 information literacy items for RN-BSN students.

Results

Demographics

Mean age of subjects participating in this study was around 30 years. Most had more than 5 years of work expe-rience, were single (87.5%), and worked in acute/intensive (34.3%) or medical/surgical (43.8%) units as professional nurses (68.8%). Using the t test, Fisher Exact test, and Chi-Square statistical analysis, no significant differences were identified between the experimental (n = 32) and con-trol (n = 43) groups in terms of age, marital status, job title, work unit, and years of work experience. Table 3 presents demographic data for the experimental and control groups.

Table 2.

Information Literacy Items

Items

Searching and Screening

1. the ability to search information from different books 2. the ability to screen information from different books 3. the ability to search information from different journals 4. the ability to screen information from different journals

5. the ability to search information from various Internet websites/web pages 6. the ability to screen information from various Internet websites/web pages Integrating

1. the ability to integrate information from different books 2. the ability to integrate information from different journals

3. the ability to integrate information from various Internet websites/web pages Analyzing

1. the ability to compare information from books, journals, and the Internet 2. the ability to interpret information from the perspective of gender 3. the ability to analyze information from the perspective of gender 4. the ability to interpret information from different feminist perspectives 5. the ability to analyze information from different feminist perspectives Applying

1. the ability to apply information from different books to the design of problem-solving strategies to moderate case health issues 2. the ability to apply information from different journals to the design of problem-solving strategies to moderate case health issues 3. the ability to apply information from different Internet websites to the design of problem-solving strategies to moderate case

health issues

4. the ability to apply information from different books, journals, and the Internet in clinical cases

5. the ability to apply information from different books, journals, and the Internet into the nursing practicum 6. the ability to publish final reports in the women health journals

Presenting

1. the ability to use 18 Word skills 2. the ability to use 18 Excel skills 3. the ability to use 18 PowerPoint skills

Information Literacy

Using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with infor-mation literacy as a covariate variable, no significant dif-ference in information literacy (inclusive of searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting information) was found between experimental and control groups in the test administered prior to the beginning of the semester. However, with the exception of “presenting skill”, a significant difference in information literacy di-mensions was identified between the two groups in the test administered after the semester concluded. Table 4

pres-ents pre- and post-semester test scores of information liter-acy for experimental and control groups.

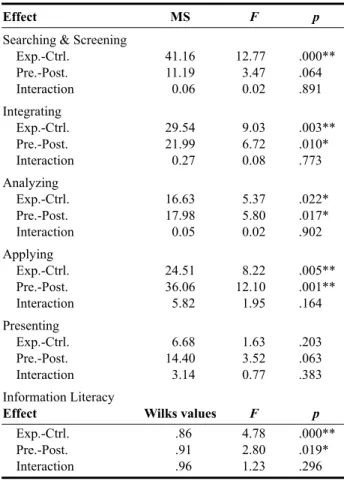

Through 2´ 2 Factorial ANOVA statistical analysis (Exp.-Ctrl. & Pre.-Post.) through General Linear Models, information literacy in the experimental group was found to have performed significantly better than the control group in terms of the level of improvement registered be-tween pre-semester and post-semester testing (Exp.-Ctrl., Wilks values = .86, F = 4.78; **p < .01; Pre-Post, Wilks values = .91, F = 2.80; *p < .05), especially in the dimen-sions of information integration, analysis, and application. Although searching and screening information abilities in

Table 3.

Experimental and Control Group Demographics (N = 75)

Experimental group Control group

Item of Comparison M ± SD n (%) M ± SD n (%) t/c2 p Age 29.31± 3.43 30.48± 3.66 1.62 .109a Working Experience 07.53± 2.81 08.34± 3.42 1.23 .221a Marital Status 0.91 .377b Single 28 (87.5) 34 (79.1) Married 04 (12.5) 09 (20.9) Work Unit 0.46 .794c Acute 11 (34.3) 15 (34.9) Medical/Surgical 14 (43.8) 16 (37.2)

Obs & Gyn/Pediatric/Others 07 (21.9) 12 (27.9)

Job Title 0.01 .904c

Professional nurse 22 (68.8) 29 (67.4)

General nurse/Technician 10 (31.2) 14 (32.6)

Note. Obs & Gyn = Obstetrics and Gynecology. a

t-test; bfisher exact test; cchi-square test. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Table 4.

Changes in Five Information Literacy Skill Scores for Experimental and Control Groups Before and After Intervention

Pre-semester test Post-semester test

Exp. Ctrl. Exp. Ctrl.

Items M ± SD M ± SD t p M ± SD M ± SD Fa p

Searching & Screening 5.91± 1.75 5.33± 1.66 1.48 .144 6.81± 1.46 5.81± 2.05 5.78 .019* Integrating 5.77± 1.86 5.07± 1.82 1.64 .106 6.71± 1.52 5.74± 2.03 6.57 .012* Analyzing 5.50± 1.90 4.95± 1.84 1.26 .213 6.30± 1.23 5.49± 1.80 5.45 .022* Applying 5.34± 1.74 4.98± 1.74 0.90 .369 6.75± 1.05 5.56± 2.10 8.23 *.005** Presenting 2.30± 1.72 3.13± 1.98 -1.91- .060 3.41± 1.96 3.83± 2.27 0.56 .456*

Information Literacy 24.82± 7.310 23.46± 7.140 0.81 .420 30.00± 5.630 26.55± 8.740 4.09 .047* Note. Exp. = experimental group; Ctrl. = control group. a

Results of ANCOVA. *p < .05. **p < .01.

the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group, the difference between pre-semester to post-semester testing results was not significant. Addi-tionally, improvements in information presentation in the experimental group were not significantly better than the control group, nor were differences between pre-semester and post-semester testing results. Table 5 illustrates the effect of F and Wilks values on information literacy in the experimental and control groups. Figure 1 presents the dif-ferences in information literacy between the experimental and control groups in both pre-semester and post-semester testing and Figure 2 shows the differences in searching and

Figure 1. Information literacy differences between experi-mental and control groups.

Figure 2. Differences in searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting abilities between experimental and control groups.

Table 5.

Experimental (n = 32)-Control (n = 43) Groups by Factorial ANOVA

Effect MS F p

Searching & Screening

Exp.-Ctrl. 41.16 12.770 .000** Pre.-Post. 11.19 3.47 .064 Interaction 00.06 0.02 .891 Integrating Exp.-Ctrl. 29.54 9.03 .003** Pre.-Post. 21.99 6.72 .010* Interaction 00.27 0.08 .773 Analyzing Exp.-Ctrl. 16.63 5.37 .022* Pre.-Post. 17.98 5.80 .017* Interaction 00.05 0.02 .902 Applying Exp.-Ctrl. 24.51 8.22 .005** Pre.-Post. 36.06 12.100 .001** Interaction 05.82 1.95 .164 Presenting Exp.-Ctrl. 06.68 1.63 .203 Pre.-Post. 14.40 3.52 .063 Interaction 03.14 0.77 .383 Information Literacy

Effect Wilks values F p

Exp.-Ctrl. 0.86 4.78 .000** Pre.-Post. 0.91 2.80 .019* Interaction 0.96 1.23 .296 Note. Exp. = experimental group; Ctrl. = control group; Pre. = Pretest; Post. = Posttest. *p < .05. **p < .01.

screening, integrating, analyzing, applying, and presenting abilities between the two groups in pre-semester and post-semester testing.

Discussion

This quasi-experimental study compared the informa-tion literacy of nursing students in experimental and con-trol groups. After taking a one semester course in women’s health that included information literacy training, the ex-perimental group scored significantly better than the con-trol group in all information literacy dimensions, with the exception of “presenting information”. This result is simi-lar to that obtained by Wallace et al. (1999), who found that the cognition of Australian nursing students improved after receiving information education. Verhey (1999) also indi-cated that nursing students utilized information resources (articles and journals) after information education better than prior to receiving such education. Shorten et al. (2001) further demonstrated that nursing students participating in a information literacy curriculum attained better informa-tion literacy than those who did not. However, conclusions in this study differ from those obtained in the research of Wallace et al. (2000), which detected no significantly dif-ferent information literacy in 55 nursing students who had participated information literacy program and a similar number who did not.

In terms of presenting information, the result of this study is similar to that of Chuang and Chuang (2003), which found that the ability of 160 RN-BSN nursing stu-dents to use Excel and PowerPoint did not improve sig-nificantly after skills training, even though students became more positive about using computer software such as Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and Medline. However, Chiu (2000) found that the ability to use Word, Excel, and the Internet increased to 70-80 percent for administration nurses and 80-90 percent for staff nurses within 6 weeks of taking relevant training courses. A reason why 75 RN-BSN student computer skills did not improve in this study may be because few RN-BSN stu-dents who handled the final group project presentation could have been the only ones with practical computer skills. This would have made this study different from Chiu’s (2000), which required every subject to complete computer skills training. Also, subjects in both the experimental and control groups in this study had all completed a basic computer skills course during their

first semester and should have a rudimentary familiarity with computer use and may not have been able to improve their level of skills during this study signifi-cantly due to a ceiling effect.

Furthermore, while this study identifies the impor-tance of information literacy education to enhance key dimensions of nursing student information literacy (e.g., searching and screening, integrating, analyzing, apply-ing, and presenting information), this study lacks com-munication between teacher and nursing students through media, and distance education. Duh, Wen, and Wen (2003) suggested that computer-mediated commu-nication has already become the most important channel of communication in 21st century nursing education. Media literacy represents the ability to understand and analyze media information, and is different from In-ternet literacy, which comprises the knowledge and skills required to search successfully for information on the Internet (Hsu, 2002). Chen (2002) further examined information about the Internet and communication ser-vices and how such is used in nursing. In the area of dis-tance education, Chiou (2001) proposed the definitions, types, strengths and weakness of distance education that apply to the nursing curriculum, especially in relation-ship to continuing education.

Conclusion

Information education has a history of more than 10 years in American and Australian nursing schools, with schools in the United States currently the most likely to integrate information education into nursing curriculum. Information education in Taiwan nursing schools re-mains in its infancy. As reflected in various studies, all countries maintain an excessive focus on basic computer skills in information literacy training. Therefore, the authors of this study suggest that nursing education in Taiwan should place a greater emphasis on information literacy education and design curricula to cultivate nurs-ing student information literacy, includnurs-ing the ability to search and screen, integrate, analyze, apply, and present information. Through advanced statistical analysis in this study, information literacy education was integrated into a one-semester women’s health course. Students who took this course registered an improvement in infor-mation literacy as compared with that of the control group, especially in along the dimensions of integrating, analyzing, and applying information. In terms of

apply-ing information, six groups of 32 RN-BSN students pub-lished their final reports in the professional journals, Kaohsiung Women Awakening Association and Women Center supported by the Bureau of Social Affairs Kaohsiung City Government. It is expected that nursing students in the future can apply information literacy abil-ities to solve patients’ health problems in clinical set-tings based on scientific data, which addresses the essence of evidence-based nursing.

Limitations

The authors identified two principal limitations of this study. Firstly, as the control group in this study attended a course entitled, “Marriage and Family”, researchers are unclear whether differences in information literacy abili-ties between the two groups are due to differing course goals and contents or to different teaching strategies be-tween instructors. Secondly, it remains unclear whether registered improvements were due to information literacy education or to the women’s health course curriculum. Future studies should compare the information literacy lev-els of nursing students participating in a women’s health course with information literacy education to students who take such a course without.

References

Cheek, J., & Doskatsch, I. (1998). Information literacy: A re-source for nurses as lifelong learners. Nursing

Educa-tion Today, 18(3), 243–250.

Chen, S. W. (2002). The internet: A new terrain for nursing professional. The Journal of Nursing, 49(6), 73–76. (In Chinese.)

Chiou, S. F. (2001). Distance education: A new teaching met-hod in nursing education. The Journal of Nursing, 48(4), 37–43. (In Chinese.)

Chiu, T. S. (2000). To promote the nursing personnel’s com-petence in information application through the life-long learning philosophy. VGH Nursing, 17(3), 248–259. (In Chinese.)

Chuang, Y. H., & Chuang, Y. W. (2003). Attitudes of two-year RN-BSN nursing students toward computers. The

Journal of Health Science, 5(1), 71–82. (In Chinese.)

Chuang, Y. H., & Hung, Y. Y. (2004). Nursing informatics: A new nursing specialty. The Journal of Nursing, 51(3), 59–64. (In Chinese.)

Cole, I. J. (2004). Computer literacy and skill system a soft-ware development project into computer and

informa-tion literacy for nursing students. On-Line Journal of

Nursing Informatics, 8(3), 21.

Dorner, J. L., Taylor, S. E., & Hodson-Carlton, K. (2001). Faculty-librarian collaboration for nursing information literacy: A tiered approach. Reference Service Review,

29(2), 132–140.

Duh, C. M., Wen, L. R., & Wen, M. Y. (2003). The impact of

network literacy on nursing students’ professional knowledge acquisition (in Chinese). Proceedings of the

3rd International Conference on Information Literacy and Life Long Learning Society. Shu-Te University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung county, Taiwan. Guillot, L., Stahr, B., & Plaisance, L. (2005). Dedicated

on-line virtual reference instruction. Nurse Educator, 30(6), 242–246.

Hsu, L. L. (2002). The application of information literacy to the nursing curriculum. The Journal of Nursing, 49(3), 54–58. (In Chinese.)

Huang, Y. R. (2004). The research of factors that affect the

nursing staff ’s development of information accomplish-ment- An Taiwan as an example (in Chinese).

Unpub-lished master’s thesis, National Chung Cheng Univer-sity, Taiwan.

Lee, S., Chen, S. L., & Chen, S. L. (2001). Nursing higher education meeting the changes and challenges of the 21st century. The Journal of Nursing, 48(4), 25–30. (In Chinese.)

Liu, D. M., & Shieh, M. L. (2000). Medical and nursing re-search information. The Journal of Health Science, 2(1), 12–33. (In Chinese.)

McNeil, B. J., Elfrink, V. L., Bickford, C. J., Pierce, S. T., Beyea, S. C., Averill, C., et al. (2003). Nursing infor-mation technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: A U.S. survey. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 341–349.

Pierce, S. T. (2000). Readiness for evidence-based practice:

Information literacy needs of nursing faculty and stu-dents in a Southern United States. Unpublished

doc-toral dissertation, Northwestern State University, Loui-siana.

Rosenfeld, P., Salazar-Riera, N., & Vieira, D. (2002). Pi-loting an information literacy program for staff nurses: Lessons learned. Computers, Informatics, Nursing,

20(6), 236–243.

Saranto, K., & Hovenga, E. J. S. (2004). Information liter-acy-what it is about? Literature review of the concept and the context. International Journal of Medical

Shorten, A., Wallace, M. C., & Crookes, P. A. (2001). De-veloping information literacy: A key to evidence-based nursing. International Nursing Review, 48(2), 86–92. Tanner, A., Pierce, S., & Pravikoff, D. (2004). Readiness

for evidence-based practice: Information literacy needs of nurses in the United States. Medinfo, 11(2), 936–940.

Verhey, M. P. (1999). Information literacy in an undergradu-ate nursing curriculum: Development, implementation, and evaluation. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(6), 252–259.

Wallace, M. C., Allison, S., & Crookes, P. A. (2000). Teaching information literacy skills: An evaluation.

Nur-se Education Today, 20(6), 485–489.

Wallace, M. C., Shorten, A., Crookes, P. A., McGurk, C., & Brewer, C. (1999). Integrating information literacy into an undergraduate nursing program. Nursing Education

Today, 19(2), 136–141.

Wen, L. R., & Duh, C. M. (1999). Innovative medical and nursing informatics curriculum-CSCW in problem ba-sed learning. Journal of Health Science, 1(1), 107–117. (In Chinese.)

整合資訊素養教育於婦女健康課程對在職護生

資訊素養之效能影響

顧雅利 許淑蓮* 郭世明**

摘 要:

資訊素養為發展實證護理的必備條件,且其可培養護理人員終身學習的能力。護理 教育應將資訊素養教育融入護理課程中,以增進護生的資訊素養能力。本研究目的 以比較有無接受資訊素養教育課程之在職護生的資訊素養技能方式,來探討資訊素 養教育的成效。此類實驗研究於2004 年 3 至 6 月期間執行於婦女健康議題課程中, 教導32 位在職護生搜尋與篩選、整合、分析、運用、及呈現資訊的技能。七十五位實驗及控制組學生於計畫前後以10 point Likert scale 自我評值其資訊搜尋與篩選、

整合、分析、運用、與呈現技巧等能力。結果顯示實驗組 (n = 32) 與控制組 (n = 43) 於年齡、婚姻、工作職稱、單位、年資、及學期一開始的資訊素養能力均無呈現顯 著地差異。一學期後,除了資訊的呈現能力外,實驗組由前測至後測其資訊素養能 力表現顯著地比控制組良好,尤其在資訊的整合、分析、及運用三方面。期許護生 未來能運用所加強的資訊素養技巧,來提出及解決臨床上患者的健康問題。