Schizophrenia is a devastating disease with a chronic course,1,2and results in marked impair-ment of social functions3–6 in the majority of patients. Over 90% of patients with schizophre-nia in Taiwan live with family;7 therefore, fam-ilies play a critical role in the daily life and care of patients. In general, psychiatric rehabilitation programs in Taiwanese communities have been inadequate,8–10 which has left caregivers with the burden of patient care. The issue of the bur-den on caregivers and their families has also been emphasized in research into the cost of

schizophrenia.11,12 Because of the shortage of supply of adequate psychiatric aid in the public sector, the caring potential and innate strength of caregivers should be fostered in a society with limited resources.

The field of mental healthcare research usu-ally adopts instruments of needs assessment, such as the Medical Research Council Needs for Care Assessment Schedule (MRC NCA) and the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN), to de-termine needs status and whether the provided services meet these needs.13As these instruments

Factors Related to Perceived Needs of Primary

Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia

Ling-Ling Yeh,1Hai-Gwo Hwu,2,3,4* Chun-Houh Chen,5Chen-Hsin Chen,4,5Agnes C.C. Wu6

Background/Purpose: Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness, and sufferers are usually dependent on

family, primary caregivers in particular. The present study was designed to assess the perceived needs of caregivers so that adequate services can be provided for them in the community.

Methods: A total of 177 primary caregivers were interviewed with the structured burden-and-need schedules

to determine their perceived needs, and the related clinical and demographic factors. Fourteen perceived needs were identified and classified into different need clusters using the generalized association plots. A multiple regression of logistic model was adopted to explore the relationships between the related factors and perceived needs.

Results: Four clusters of perceived needs were identified, which included assistant patient care (77.6%),

access to relevant information (66.1%), societal support (68.2%), and burden release (27.2%). These needs were significantly related to number of admissions, duration of illness, relationship between caregiver and patient, and education level of the caregiver.

Conclusion: Four clusters of caregivers’ perceived needs were identified and found to be related to

psychopa-thologic and demographic factors. These data are of value in designing appropriate community psychiatric programs to improve the quality of care and enhance the capacity of primary caregivers to care for patients. [J Formos Med Assoc 2008;107(8):644–652]

do not explore the perceived needs of primary caregivers, research findings using these instru-ments cannot reflect the support modalities or the potential of caregivers to care for patients. A few studies14–17have detected factors related to needs status (i.e. needs met or unmet) but pro-vided no insight into the target characteristics of subjects for allocating more resources. If we could identify specific patient and caregiver characteristics from the perspective of the pri-mary caregivers in order to distribute more mental healthcare resources, we would be able to achieve the goals of enhancing efficiency of resource al-location and fostering the innate strengths of caregivers.

Thus, the aim of this research was to explore the perceived needs of primary caregivers and to determine the related factors. Perceived needs are hypothesized to be related to patients’ clinical course, and the demographic and family/social variables of the primary caregivers. This research was also designed to identify specific character-istics of patients and caregivers that have the propensity for perceiving their needs.

Methods

SamplesThis study recruited patients who fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia,1 who were consecutively admitted to the acute psychiatric wards of the Department of Psychiatry, National Taiwan University, university-affiliated hospital of the Taoyuan Psychiatric Center, and Taipei City Psychiatric Center. All patients in this study underwent psychiatric treatment following the American Psychiatric Association practice guide-lines for comprehensive psychosocial manage-ment and medication.18 All subjects were also participating in the multidimensional psycho-pathological group research project (MPGRP)19 sponsored by the National Health Research Institute in Taiwan, a prospective follow-up psy-chopathologic study of schizophrenia. The re-cruitment details have been given in a previous

report.20 However, this investigation focused on the perceived needs of the primary caregivers.

The inclusion criteria for the primary care-givers enrolled in this study were as follows: (1) cohabitation with the patient; (2) responsibility for patient care; (3) primary decision-maker in treatment; and (4) communication capability and availability to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from both patients and primary caregivers for recruitment as study sub-jects. A well-trained research assistant interviewed primary caregivers face-to-face using the Family Caregiver Burden and Need Schedule (FBNS).19 Some caregivers were not able to provide infor-mation for all the research interests, and unavoid-ably, there was a proportion of primary caregivers who had missing data for some variables. Data collection

The FBNS consists of 382 items: 19 involved quan-titative data and were shown to have satisfactory interrater reliability (all intraclass correlation co-efficients [ICC] > 0.8); 156 items were rated in ranking scale, with satisfactory interrater reliabil-ity (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients > 0.8) for 154, while the remaining two were accept-able in this regard (0.7–0.8); and 207 items in-volved categorical data, with interrater reliability of κ > 0.80 for 204, and κ = 0.6–0.79 for the remaining three items. In general, the interrater reliability of the FBNS is very satisfactory.19 The data of the FBNS were collected during the hospitalization period of index admission.

Information with respect to the patients’ clini-cal course and status, including basic demographic data, psychiatric and treatment history, and so-cial function, were assessed by the attending psy-chiatrists, using structured clinical data schedules (CDSs)21 with satisfactory reliability. Interrater reliability was found to be satisfactory for 140 of the 153 CDS items. The 13 remaining items with lower interrater reliability were revised appropri-ately, and special instructions were provided for the researchers who conducted the interviews. The CDS data were collected at discharge of the index admission.

Analyzed variables

The 14 perceived needs obtained in the FBNS were: (1) comforting the aggravating patient; (2) assisting with the aggravating patient’s care; (3) transport of the aggravating patient to the service setting; (4) financial aid; (5) general psychological and practical support; (6) coping with medical teams; (7) understanding diagnosis and treat-ment; (8) identifying early signs of relapse; (9) understanding mental health laws; (10) general social acceptance; (11) occupational therapy; (12) sheltered work facilities; (13) advice on intimate relationships for the patient; and (14) lifelong custodial care of the patient. The interviewee provided a yes/no response with respect to these perceived needs (score, 1/0). All FNBS items had satisfactory interrater reliability (κ > 0.80).

The clinical variables used in this analysis were: (1) with/without marked negative symp-toms; (2) age at onset; (3) duration of illness; and (4) first/multiple admission/s. The presence of negative symptoms was assessed with the positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS),22 and analyzed using the generalized association plots method.20,23,24 As for interrater reliability coefficients, ICC values of 22/33 PANSS items were > 0.80, eight were 0.7–0.8, and three were 0.5–0.7. The other clinical variables were assessed by the CDS.

The family and social variables for the pri-mary caregivers were: (1) relationship between caregiver and patient; (2) education level; (3) job status; and (4) family size. The relationship be-tween the caregiver and patient was categorized as follows: (1) parent; (2) spouse; and (3) other (including sibling or child).

Data analysis

A multiple regression of logistic model26was used to examine the independent factors related to perceived needs, which were dependent vari-ables. The related factors of the perceived needs were divided into two groups of clinical and so-ciodemographic variables of the patients and the primary caregivers, respectively. SAS software27 was used for statistical analysis. The between 14 perceived needs paired absolute random error (ARE) coefficients (0≤ r ≤ 1) matrix was computed as the input proximity matrix for the GAP analy-sis. The Figure illustrates the ARE coefficients ma-trix for the 14 perceived needs permuted by the GAP divisive hierarchical clustering tree.23Each gray square in the matrix map represents a be-tween perceived needs ARE coefficient. A darker (lighter) square stands for a larger (or smaller) ARE coefficient. The GAP divisive hierarchical clustering tree algorithm automatically sorts sim-ilar perceived needs variables at closer positions along the main diagonal of the ARE coefficients matrix. Groups of darker squares along the main diagonal identify potential clusters of perceived needs. Gray squares, which occur only for the very last two columns and rows that correspond to the need cluster for burden release, including two need items concerning advice on intimate relationships and lifelong custodial care for pa-tients, represent negative ARE coefficients. The hierarchical clustering tree (dendrogram) struc-ture also reveals the clear grouping pattern of the 14 perceived needs.

Results

A total of 177 patients with schizophrenia (86 male, 91 female) were recruited for this study. In

2 years in 81 (45.8%) and 96 (54.2%) subjects, respectively.

A total of 177 primary caregivers (92 male, 85 female) were also recruited for the study. The majority were aged 31–60 years (64.6%), with 29.8% and 5.6% > 60 and < 30 years, respectively. Most of the primary caregivers were parents of the patient (70.1%), with spouses or children/ siblings (category other) making up 11.3% and 18.6% of the sample, respectively. Sixty percent of the families consisted of four individuals or less. The 14 perceived needs were grouped into four proximity clusters in the following order (upper left to lower right corner along the diagonal line of the resultant proximity matrix) based on GAP analysis: (1) need cluster for assistance with pa-tient care (5 items); (2) need cluster for accessing relevant information (3 items); (3) need cluster for societal support (4 items); and (4) need clus-ter for burden release (2 items) (Figure). Two out of the 14 perceived needs from the need cluster for burden release had zero and/or negative cor-relations with the remaining 12 (Figure).

The prevalence of the perceived needs or-dered by the GAP results is presented in Table 1. Except for lifelong custodial care (11.7%), the

prevalence of perceived needs was generally high (42.7–87.2%). Mean prevalence of the three principal need clusters for assistance with patient care, societal support, and access to relevant in-formation was 77.6%, 66.1% and 68.2%, respec-tively, while the prevalence of burden release was relatively low (27.2%).

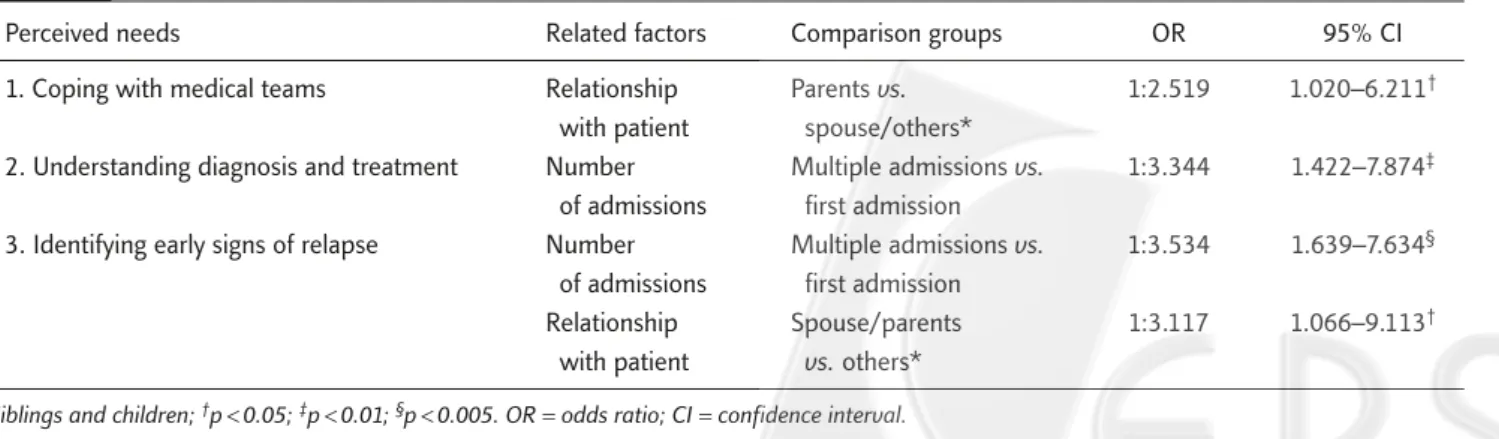

The results for factors related to specific clus-ters of perceived needs from the multiple regres-sion of logistic model are presented in Tables 2–5. Clinical variables significantly associated with various need clusters were: (1) single/multiple admission; and (2) duration of illness. Sociode-mographic variables significantly associated with need clusters were: (1) relationship between pri-mary caregiver and patient; and (2) education level of primary caregiver.

The results reveal that, in contrast to multiple admissions, for the first admission, the caregivers had a propensity to the perceived need to comfort the aggravating patient (Table 2), to understand diagnosis and treatment (Table 3), to identify early signs of relapse (Table 3), and the need for occu-pational therapy (Table 4). Comparing duration of illness (≤ 2 or > 2 years), caregivers were more likely to report the need to understand mental 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

0 1

Absolute random error coefficient

1 Need cluster for assistance with patient care Need cluster for access to relevant information Need cluster for societal support Need cluster for burden release

Coping with medical teams

Understanding diagnosis and treatment Identifying early signs of relapse Understanding mental health laws General social acceptance Occupational therapy Sheltered working facilities

Advice on intimate relationships for patient Lifelong custodial care for patient

Comforting the aggravating patient Assisting the aggravating patient

Transport of the aggravating patient to service setting Financial aid

General psychological/practical support

Figure.Generalized association plots for clustering the 14 perceived needs of the primary caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.

Table 1. Perceived needs of primary caregivers of patients with schizophrenia by prevalence and sample size

Prevalence of perceived needs Need cluster

N n (%)

I. Need cluster for assistance with patient care

1. Comforting the aggravating patient 168 133 (79.2)

2. Assisting the aggravating patient 172 150 (87.2)

3. Transport of the aggravating patient to service setting 170 135 (79.4)

4. Financial aid 168 129 (76.8)

5. General psychological/practical support 171 112 (65.5)

II. Need cluster for access to relevant information

1. Coping with medical teams 171 128 (74.9)

2. Understanding diagnosis and treatment 173 113 (65.3)

3. Identifying early signs of relapse 172 100 (58.1)

III. Need cluster for societal support

1. Understanding mental health laws 167 117 (70.1)

2. General social acceptance 169 106 (62.7)

3. Occupational therapy 162 135 (83.3)

4. Sheltered work facilities 169 96 (56.8)

IV. Need cluster for burden release

1. Advice on intimate relationships for patient 157 67 (42.7)

2. Lifelong custodial care for patient 154 18 (11.7)

Table 2. Factors related to the cluster of perceived needs for assistance with patient care

Perceived needs Related factors Comparison groups OR 95% CI

1. Comforting the aggravating patient Number Multiple admissions vs. 1:3.279 1.133–9.524* of admissions first admission

2. Assisting the aggravating patient’s care – 3. Transport of the aggravating patient to –

service setting

4. Financial aid –

5. General psychological/practical support Relationship Parents vs. 1:2.320 1.047–5.128* with patient spouse/others†

*p< 0.05; †siblings and children. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3. Factors related to the cluster of perceived needs for accessing relevant information

health laws (Table 4) and advice on intimate rela-tionships (Table 5) in patients with illness lasting longer than 2 years.

In contrast to caregivers who were parents, those who were spouses, siblings and children were more likely to report the perceived needs of gen-eral psychological and practical support (Table 2) and coping with medical teams (Table 3). In con-trast, when the primary caregiver was a sibling or a child rather than a spouse or parent, the pro-pensity was towards the perceived need to iden-tify early signs of relapse (Table 2), and general social acceptance (Table 4). The primary caregivers who were parents, siblings and children, rather than spouses, had a propensity towards the per-ceived need for occupational therapy (Table 4), and advice on intimate relationships for the patient (Table 5). Comparing education level, caregivers who had junior high school education and above had a greater propensity to the perceived need for sheltered work facilities (Table 4). Caregivers with primary/junior high school education were

more likely to state the perceived need for advice on intimate relationships for the patient (Table 5).

Discussion

This study reveals that the perceived needs of pri-mary caregivers can be grouped into four clusters, assistance with patient care, access to relevant in-formation, societal support and burden release. Except for two items in the need cluster for bur-den release, all 12 other need items had high prevalence, ranging from 58.1% to 87.2%. The clinical and demographic factors related to per-ceived needs are first/multiple admission/s, du-ration of illness (≤ 2 or > 2 years), relationship between caregiver and patient, and caregiver education level. The structure of the clusters of perceived needs as explored by GAP analysis was similar to that reported by Gall et al.28The di-mensions of social support and information with respect to patient care have also been found by

Table 4. Factors related to the cluster of perceived needs for societal support

Perceived needs Related factors Comparison groups OR 95% CI

1. Understanding mental health laws Duration of illness ≤ 2 yr vs. > 2 yr 1:5.056 2.003–12.759†

2. General social acceptance Relationship Spouse/parent vs. 1:3.137 1.105–8.905‡

with patient others*

3. Occupational therapy Relationship Spouse vs. 1:10.858 3.074–38.348†

with patient parents/others*

Number Multiple admissions vs. 1:5.556 1.355–22.727‡

of admissions first admission

4. Sheltered work facility Education level Primary school vs. junior 1:1.950 1.001–3.798‡

of caregiver high school and above *Siblings and children; †p< 0.001; ‡p< 0.05. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Table 5. Factors related to the cluster of needs for burden release

Perceived needs Related factors Comparison groups OR 95% CI

1. Advice on intimate Relationship Spouse vs. parents/others* 1:8.603 1.833–40.371†

relationships for patient with patient

Education level High school and above vs. 1:2.299 1.196–4.959†

of caregiver primary/junior high school

Duration of illness ≤ 2 yr vs. > 2 yr 1:2.216 1.082–4.539†

2. Lifelong custodial care –

Smith29and Winefield and Harvey.30Wennström et al31 identified three dimensions in the CAN, such as functional disability, social loneliness and emotional loneliness. Two of the clusters of per-ceived needs in the present study, assistance with patient care and societal support, are similar to those derived from the study of functional disabil-ity and social loneliness by Wennström et al.31 However, the need items were not exactly the same cross-culturally, and comparison of prevalence was not practical.

The need cluster for accessing relevant infor-mation consists of the perceived need to cope with medical teams, understand diagnosis and treat-ment, and identify early signs of relapse, which also had high prevalence (58.1–74.9%, Table 1). Main et al32also found that adult sibling caregivers considered that medical information provided by mental health professionals was inadequate and confusing. This finding justifies the assertion that psychological education for the primary care-giver has to emphasize this sort of psychiatric knowledge. Furthermore, the need to continuously campaign against the stigma of schizophrenia is highlighted by these research results, as demon-strated by the high prevalence of the perceived need to understand mental health laws (70.1%) and the need for widespread acceptance in soci-ety (62.7%). As the results pointed out, there is a high prevalence of perceived need for occupa-tional therapy and sheltered workshop facilities (56.8% and 83.3%, respectively). We suggest that providing sufficient community psychiatric rehabilitation services is indispensable.

It is interesting that the prevalence of perceived needs making up the burden release need cluster was relatively low (11.7–42.7%). Furthermore, it is quite remarkable that the prevalence of lifelong

hesitation. Traditionally, the siblings of these pa-tients assume this obligation of familial care when the parents die. Most parents worry about who will care for their children after their death. Therefore, parents who are primary caregivers hope that their children might develop intimate relation-ships, as their spouse would then assume the caregiver role after their death. Modernization in Taiwan will also have an impact on the integrity of the traditional family structure, which is ex-pected to increase the need for long-term custodial care in the near future. We emphasize the need for preemptive strategies in mental healthcare to deal with the issue in advance, in order to reduce the inevitable social costs associated with dramatic increases in the demand for custodial care.

The results of the present study indicate that both caregiver demographics and patient clinical variables are related to the perceived needs of primary caregivers, which provides valuable in-formation in the design of adaptive community psychiatric programs. Caregivers of first-admission patients obviously have less experience and knowl-edge with respect to the care of their charges, and a greater propensity towards the perceived need to comfort the aggravating patient, to understand diagnosis and treatment, to identify early signs of relapse, and the need for occupational therapy. Our results also reveal that caregivers were initially eager for their schizophrenic family member to be cured and eventually live independently through rehabilitation programs. In contrast, family care-givers of patients with an illness duration exceed-ing 2 years were more likely to report the perceived needs for understanding of mental health laws and for advice on intimate relationships for the patient. These more experienced caregivers had a less optimistic attitude toward schizophrenia as

and have limited available time; therefore, they are more likely to require general psychological or practical support. Furthermore, sibling and off-spring caregivers had a greater propensity towards perceived needs involving access to relevant in-formation: identifying early signs of relapse, attaining widespread acceptance in society, occu-pational therapy, and advice on intimate rela-tionships for the patient.

Caregivers with higher levels of education had a propensity towards the perceived need for shel-tered work facilities, while their less-educated counterparts were more concerned with advice on intimate relationships for the patient. The former group appeared to have a more aggressive and/or active attitude towards patient care, while the latter were apparently more conservative. The psychiatric medical service team must be sensitive to caregiver characteristics, so that they can provide appropri-ate psychological education and services.

Lauber et al34 reported that if the perceived needs of caregivers are met, it may prevent them from complete physical and emotional exhaus-tion, and increase the likelihood that they will continue to care for their charges. The perceived needs assessment could establish effective psy-chiatric service programs, and also offer an ori-entation towards setting clear goals for mental health policy. Devoting limited resources to pa-tients and caregivers with specific characteristics is efficient in terms of managing societal resources. This research approach could monitor the effi-ciency of mental healthcare systems and facilitate redirection of limited resources towards those in need.

Exploration of the perceived needs for ser-vices from the perspective of the primary caregiver provides valuable information for the reform of mental healthcare systems. Identifying specific clinical and demographic characteristics of pa-tients and caregivers through the analysis of fac-tors related to perceived needs could reallocate limited resources in an efficient way, to establish satisfactory mental health service programs. It is strongly recommended that factors related to the perceived needs of caregivers, such as the number

of admissions, duration of illness, education level of the caregivers, and their relationship with the patient, must be considered in the design of psy-chiatric services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institute, Department of Health, Taiwan (DOH 83∼88-HR-306; GT-EX 89P825P; EX90-8825PP; NHRI-EX91∼94-9113PP; NHRI-EX95, 96-9511PP).

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

2. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992:84–109.

3. Moller HJ, Von Zerssen D. Course and outcome of schizo-phrenia. In: Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR, eds. Schizoschizo-phrenia. Cambridge: Blackwell Science, 1995:106–127.

4. Hwu HG, Yeh EK. Two-year community follow-up of dis-charged psychiatric patients. Bull Chin Soc Neurol Psychiatry 1986;12:71–84.

5. Hwu HG, Chen CC, Strauss JS, et al. A comparative study on schizophrenia diagnosed by ICD-9 and DSM-III: course, family history and stability of diagnosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988;77:87–97.

6. Hwu HG. Schizophrenia—The Descriptive Psychopathology. Taiwan: Giching Publishing, 1999.

7. Hwu HG, Rin H, Chen CZ, et al. A study on the personal-familial and clinical data of psychiatric inpatients in Taiwan. Chin J Psychiatry 1995;9:16–31.

8. Hwu HG, Chen CH, Rin H, et al. The distribution of psy-chiatric beds in Taiwan. Chin J Psychiatry 1996;10:45–53. 9. Hwu HG, Chen CH, Rin H, et al. Hospital locality and domicile of psychiatric inpatients. Chin J Psychiatry 1996; 10:166–74.

10. Shen CJ, Chang SH. Stressor, coping strategy and health status among family members with psychotic patients—a time process perspective. Chin J Ment Health 1993;6: 89–116.

11. Yeh LL, Lee YL, Yang MC, et al. The economic cost of severely mentally ill patients. Chin J Ment Health 1997; 10:1–15.

12. Rupp A, Keith SJ. The costs of schizophrenia. Assessing the burden. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1993;16:413–23.

13. Cheah YC, Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Development of a measure profiling problems and needs of psychiatric patients in the community. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:337–44.

14. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kramer M, et al. Measuring need for mental health services in a general population. Med Care 1985;23:1033–43.

15. Bijl RV, Raveli A. Psychiatric morbidity, service use, and need for care in the general population: results of the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study. Am J Public Health 2000;90:602–7.

16. Burgy R, Hafner-Ranabauer W. Need and demand in psy-chiatric emergency service utilization: explaining topo-graphic differences of a utilization sample in Mannheim. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;250:226–33. 17. Andersen RL, Lyons JS. Need-based planning for persons

with serious mental illness residing in intermediate care facilities. J Behav Health Serv Res 2001;28:104–10. 18. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines

for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997:154(Suppl 1):1–63.

19. Hwu HG, Chen JZ, Lin HN, et al. Multidimensional Psychopathological Group Research Project. Report of National Health Research Institute, DOH-83-HR-306. Taiwan: National Health Research Institute, 1993. 20. Hwu HG, Chen CH, Hwang TJ, et al. Symptom patterns

and subgrouping of schizophrenic patients: significance of negative symptoms assessed on admission. Schizophr Res 2002;56:105–19.

21. Hwu HG, Yeung SY, Ko SH et al. Descriptive psychiatric data schedule: II. Personal, social and clinical data sched-ule: establishment and reliability studies. Bull Chin Soc Neurol Psychiatry 1985;11:47–56.

22. Cheng JJ, Ho H, Chang CJ, et al. Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS): establishment and reliability study of a Mandarin Chinese language version. Taiwan J Psychiatry 1996;10:251–8.

23. Chen CH. Generalized association plots for information vi-sualization: the applications of the convergence of itera-tively generated formed correlation matrix. Statistica Sinica 2002;12:1–23.

24. Lin ASK, Chen CH, Hwu HG, et al. Psychopathological di-mensions in schizophrenia: a correlational approach to items of the SANS and SAPS. Psychiatry Res 1998;77: 121–30.

25. Maxwell AE. Coefficients of agreement between ob-servers and their interpretation. Br J Psychiatry 1977;130: 79–83.

26. Fleiss JL, Williams JBW, Dubro AF. The logistic regression analysis of psychiatric data. J Psychiatr Res 1986;3: 195–209.

27. SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1990. 28. Gall SH, Atkinson J, Elliott L, et al. Supporting carers of

people diagnosed with schizophrenia: evaluating change in nursing practice following training. J Adv Nurs 2003; 41:295–305.

29. Smith G. Patterns and predictors of service use and unmet needs among aging families of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:871–7.

30. Winefield HR, Harvey EJ. Needs of family caregivers in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1994;20:557–66. 31. Wennström E, Sörbom D, Wiesel FA. Factor structure

in the Camberwell Assessment of Need. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:505–10.

32. Main MC, Gerace LH, Camiller D. Information sharing concerning schizophrenia in a family member: adult sib-lings’ perspectives. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1993;7:47–53. 33. Tsui SC, Yang YK, Shieh SK, et al. Comparison of family

burden and needs of home care service between schizo-phrenic and bipolar disorder patients. Taiwan J Psychiatry 1998;12:188–93.

34. Lauber C, Eichenberger A, Luginbühl P, et al. Determinants of burden in caregivers of patients with exacerbating schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2003;18:285–9.