探究教師於程度差異大班級教學的認知與實務:一位英語教師之個案研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Exploring Teacher Cognitions and Practices in Teaching Large Multilevel English Classes: A Case Study. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English, National Chengchi University. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 sit. y. Nat. n. er. io. In Partial Fulfillment of athe Requirements for the Degree l C Master of Arts n i v of U h. engchi. by Wun-ting Jhuang October 2013.

(3) Acknowledgements This work could not have been completed without the support and encouragement of many people. First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude and greatest appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Chin-chi Chao, who had been offering insightful guidance and much encouragement throughout the research of this work. I would also like to thank the two committee members, Dr. Chen-kuan Chen and Dr. Yi-ping Huang, for their encouraging words and useful advice, which helped me to further refine my thesis. My sincere appreciation also goes to Joy Lee, the teacher participant of this study.. 治 政 Without her kind and generous sharing of her learning, 大 learning-to-teach and teaching 立 experiences, this research would not have been possible. In addition, I would like to ‧ 國. 學. extend my gratitude to Sin-yin Lee, who had been providing considerable help by. sit. y. Nat. throughout the conduction of this research.. ‧. undertaking peer debriefing and offering consistent and timely encouragement. io. er. Last but not least, I would like to give my warmest thanks to my family and. al. friends who have accompanied me throughout the work. If it had not been for their. n. iv n C love, company and support, I could have enjoyed my thesis journey and learnt so h enot ngchi U much from the process.. iii.

(4) Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................................... iii. Table of Contents......................................................................................................... iv. Chinese Abstract.......................................................................................................... vi. English Abstract........................................................................................................... vii. Chapter 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................. 1. 1.1 Background of the Study............................................................................... 1. 1.2 Significance of the Study............................................................................... 6. 治 政 2. Literature Review…................................................................................................ 大 立 2.1 Research on Language Teacher Cognition.................................................... 9 9. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2 Borg’s (2006) Framework of Elements and Processes in Language 14. 2.3 Teaching English in Multilevel Classrooms.................................................. 19. ‧. Teacher Cognition................................................................................................ sit. y. Nat. io. al. er. 2.4 Teaching English in Large Multilevel Classrooms in Taiwan ...................... n. 2.5 Rationale and Research Questions of the Present Study…………………... Ch. n engchi U. iv. 23 28. 3. Methodology............................................................................................................ 31. 3.1 Research Design............................................................................................. 31. 3.2 Participants.................................................................................................... 32. 3.3 Data Collection and Procedures..................................................................... 37. 3.4 Data Analysis................................................................................................. 41. 4. Findings.................................................................................................................... 45. 4.1 Knowing and Empathizing with Her Students............................................... 46. 4.2 Building Variety into Teaching Practices to Accommodate the Diversity of Students…………………………………………………………………….. iv. 54.

(5) 4.3 Adding Differentiation into Criteria to Attend to the Diversity of Students. 65. 4.4 Admitting that Things Can be Beyond Her Control...................................... 73. 5. Discussion................................................................................................................ 81. 5.1 The Impact of Experience on the Teacher’s Cognition and Practice............. 81. 5.2 Reflection....................................................................................................... 88. 5.3 The Teacher’s Cognition about Students....................................................... 94. 5.4 The Impact of Context on the Teacher’s Cognition and Practice………...... 98. 6. Conclusions.............................................................................................................. 105. 6.1 Summary of the Study................................................................................... 105. 治 政 6.2 Pedagogical Implications.............................................................................. 大 立 6.3 Limitations of the Study................................................................................ 學. ‧ 國. 107 110 110. References................................................................................................................... 112. Appendices. 123. ‧. 6.4 Suggestions for Future Research................................................................... sit. y. Nat. io. al. er. A. Interview protocol for teacher narrative.................................................................. n. B. Interview protocol for post-observation semi-structured teacher interview........... Ch. n engchi U. v. iv. 123 125.

(6) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:探究教師於程度差異大班級教學的認知與實務:一位英語教師之個案 研究 指導教授:招靜琪博士 研究生:莊雯婷. 論文提要內容:. 政 治 大. 現有文獻指出在程度差異大班級中的英語教學相關研究傾向將研究重點置 於教師遇到的困難以及他們發現可有效解決問題的教學實務方法。少有研究會進 一步研究教師的心理層面以解釋這些教學實務方法是如何以及為何被使用在特 定教學時機與場域,也因此使他們的研究討論僅流於教學的表層。 為了呈現一個對程度差異大班級中的英語教學較為全面且深入的理解,本研 究採用教師敘事、訪談、觀察以及文件分析來研究一教師如何在程度差異大班級 中教英語、她在這樣的班級中教英語時抱有什麼教學認知以及她如何發展出這樣. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 的認知。 研究結果顯示此研究對象之教師持有四大教學認知與實務,包括(一)瞭解 並同理其學生、(二)使其教學實務多樣化以容納學生的多樣性、(三)將學習 標準層級化以照顧學生的多樣性,以及(四)接納有些事情乃是其力所不逮。經 分析後,研究者發現這四大教學認知與實務乃是研究對象之教師基於她所持有的 廣泛經驗,不論其發生於教室內或外,所進行省思後,構成並再次構成的教學認 知與實務。然而,儘管懷有這四大教學認知,研究對象之教師並非總能落實符合 其認知的教學實務。事實上,研究者發現研究對象之教師能實施符合其認知之教 學實務的程度乃是她個人落實其教學認知的能力與外在教學場域願意提供多大 空間予其落實其認知於實務之互動下的結果。. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 試圖促進在程度差異大班級中的英語教學與研究,本研究向在此種班級中的 四大主要族群,包括教師、教師培育者、研究者以及此班級下的其他相關人士提 出相關建議。 關鍵字:教師認知、程度差異大班級、學習英語為外語、質化個案研究. vi.

(7) Abstract A review showed that existing literature on teaching English in multilevel classrooms tends to focus on the difficulties teachers encounter and practices they find to be effective in addressing the problems in teaching such classes (Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Liu, 2004; Maddalena, 2002; Xanthou & Pavlou, 2008). Few studies have probed further to investigate the mental dimension of teaching that accounts for how and why certain practices are adopted in particular periods of class time and specific teaching contexts (Lu, 2011; Teng, 2009), hence rendering the discussions rather superficial touching only the surface of teaching.. 治 政 To present a more holistic and in-depth understanding 大 of teaching large 立 multilevel English classes, the present study drew on a teacher narrative, interviews, ‧ 國. 學. observations and document analyses to investigate how the teacher participant taught. ‧. large multilevel English classes, what cognitions she held in teaching such classes and. sit. y. Nat. how she developed such cognitions.. io. er. The findings revealed that the teacher held four major cognitions and practices in. al. teaching large multilevel English classes, including (1) knowing and empathizing. n. iv n C with her students; (2) building variety teaching practices to accommodate the h e ninto gchi U diversity of students; (3) adding differentiation into criteria to attend to the diversity of students and (4) admitting that things can be beyond her control. The four major cognitions and practices were found to have structured and restructured through the reflection that the teacher undertook on the vast experiences that she had accumulated both inside and outside the classroom. However, despite holding these cognitions, the teacher could not always implemented practices that conformed to her cognitions. In fact, it was found that the extent to which the teacher could implement practices congruent with her cognitions was the interactive result of her internal capacity to find vii.

(8) spaces to realize her cognitions and the surrounding teaching contexts’ willingness to allow room for her to put her cognitions into practices. In an attempt to facilitate instruction and research in large multilevel English classrooms, the study yielded implications for four parties working in the relevant contexts, including teachers, teacher educators, stakeholders of teaching contexts other than teachers, and researchers.. Keywords: teacher cognition, large multilevel classes, EFL, qualitative case study. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i Un. v.

(9) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study With the recognition that English has become one of the most widely spoken international languages (Crystal, 2003), an increasing number of researchers have devoted themselves to the research of teaching and learning English in a hope to understand how to learn English effectively. One of the research focuses in the field of teaching and learning English is the study of English teaching as it is considered to be one of the crucial driving forces for successful English learning on the part of learners.. 治 政 However, this tradition of inquiry did not receive the 大same amount of attention as it 立 does nowadays. In the earlier years of the study, teachers were viewed simply as ‧ 國. 學. followers of dominant teaching methods and objects of study (Johnson & Golombek,. ‧. 2002; Woods, 1996). While there was an abundant amount of research on the. sit. y. Nat. acquisition of second and foreign languages, a largely far less number of studies was. io. er. conducted to systematically examine how teachers instruct second and foreign. al. languages. It was not until more recently that teachers began to be recognized as. n. iv n C active thinking agents and knowing (Borg, 2003, 2006; Johnson & h e professionals ngchi U. Golombek, 2002; Woods, 1996) and a growing interest has been paid to such study, especially in the domain of teacher cognition. Teacher cognition is a collective term used by Borg (2003, 2006, 2009) to refer to the unobservable mental dimension of teaching including “what teachers know, believe, and think (Borg, 2003, p.81).” As a matter of fact, in an attempt to develop a better understanding of language teacher cognition and promote continued research on this domain of inquiry, Borg (2006) published a book about language teacher cognition, where he gave a general outline of teacher cognition research from which studies of language teacher cognition drew their conceptual basis, and studies that have been conducted from a 1.

(10) language teacher cognition perspective. In reviewing the existing studies, Borg found out that a large number of studies on teacher cognition, whether in the context of mainstream education or that of language teaching, supported a sociocultural view of teacher cognition and teacher learning. As Johnson (2009) noted, such a perspective sees teachers as learners of teaching who learn what and how to teach by personally engaging in learning and teaching activities and teacher cognition is developed from the participation of these activities. Based on his review, Borg suggested that the nature of teacher cognition is personal, practice-oriented and dynamic and also proposed a framework to illustrate how teacher cognition and practice are constructed. 治 政 and reconstructed from teachers’ personal learning and teaching 大 experiences. What 立 are implied in the framework are the interrelated and interactive relationships among ‧ 國. 學. language teachers’ learning, cognition and classroom practice, which indicate that to. ‧. have a holistic and in-depth understanding of a language teacher and her teaching, one. sit. y. Nat. cannot avoid studying either of the three.. io. er. Of the numerous contexts studied in the field of English teaching, one teaching. al. context that has received much attention is teaching in multilevel classrooms.. n. iv n C Multilevel classes are also known as mixed-ability classes (Baurain h e n g corhheterogeneous i U. & Phan, 2010), and are defined by Hess (2001) as “the kinds of classes that have been roughly arranged according to ability, or simply classes that have been arranged by age-group with no thought to language ability” (p.2). A multitude of factors have been reported to contribute to such classes, including difficulties to place students into different classes according to their English proficiency levels due to financial resources deficit or policies, and individual student factors, which are factors that vary across learners and may lead to diverse pace of learning, such as age, learning styles, personalities, and willingness to communicate (Mathews-Aydinli & Van Horne, 2006; Roberts, 2007). Teaching in such classes thus presents a variety of challenges for 2.

(11) teachers. Difficulties that have been mentioned frequently by teachers teaching in these contexts include difficulties of managing classroom effectively, of meeting the various needs and enhancing the motivation and interest of students with adequate materials and activities, of paying sufficient individual attention to students, and of assessing students effectively and appropriately (Baurain & Phan, 2010; Chang, 2009; Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Hess, 2001; Liu, 2004; Lu, 2011; Maddalena, 2002; Mathews-Aydinli & Van Horne, 2006; Teng, 2009; Ur, 1991; Xanthou & Pavlou, 2008). To address the teaching difficulties encountered in multilevel classrooms, many. 治 政 teachers and researchers in the field of Teaching English 大 to Speakers of Other 立 Languages (TESOL) invest considerable time and energy to study and share the ‧ 國. 學. practices and approaches that have worked effectively in their contexts and for their. ‧. students. Approaches said to work in multilevel classrooms include differentiated. sit. y. Nat. instruction (King-Shaver & Hunter, 2003; Quiocho & Ulanoff, 2009; Rothenberg &. io. er. Fisher, 2007; Tomlinson, 1999; Tomlinson, 2001) and cooperative learning. al. (MacDonald & Smith, 2010). In addition to these approaches, practices that are. n. iv n C recognized to be effective in addressing in teaching multilevel classes h e n gdifficulties chi U include practices such as conducting needs analysis prior to teaching, using classroom management strategies, using grouping strategies flexibly, providing self-access materials, using multilevel tasks and assessment and adopting leveled teaching materials and homework (Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Hess, 2001; Liu, 2004; Lu, 2011; Mathews-Aydinli & Van Horne, 2006; Roberts, 2007; Shank & Terrill, 1995; Teng, 2009; Ur, 1991; Xanthou & Pavlou, 2008). Although the literature on teaching multilevel English classes receives not a small coverage; however, most is not research-based. Of the relevant studies that the researcher reviewed, only eight articles are research-based. Among these, only three 3.

(12) were conducted in countries other than Taiwan. These thee studies were carried out in three different countries and with quite diverse research designs. Each provided different aspects of understandings about teaching English in multilevel classrooms, but few, except for the study conducted by Freedman, Delp and Crawford (2005), mentioned much about the interaction between teacher cognition and practice in such contexts. The study of Freedman et al. (2005) examined how an experienced teacher, Delp, taught in an untracked English literacy class and how her students thought of her teaching to understand how to successfully meet the needs of diverse students in untracked classrooms. Though providing a holistic and in-depth understanding of. 治 政 teaching and learning in untracked English classrooms, the大 study of Freedman et al. 立 (2005), however, was conducted in an English literacy class and placed its focus on ‧ 國. 學. teaching English literacy through literature studies, thus rendering itself rather hard to. ‧. shed light on teaching EFL in multilevel classrooms. Another study conducted by. sit. y. Nat. Xanthou and Pavlou (2008) investigated how 114 EFL teachers of public primary. io. er. schools in Cyprus dealt with teaching multilevel classes. In employing questionnaire. al. as their main research method for collecting data, Xanthou and Pavlou (2008) could. n. iv n C only provide a general understanding ofhhow the teacher participants in Cyprus taught engchi U and thought how they should teach in multilevel English classes. Also studying teaching English in multilevel classrooms, Maddalena (2002) however focused his study mostly on learners’ perspectives, that is, the examination of how his Japanese adult students responded to and perceived the use of advanced learners as teaching assistants, and offered few specific details about his cognition and practice of inviting advanced learners to be his teaching assistants in teaching the mixed-ability class. In Taiwan, a considerable number of scholars and researchers also noticed the numerous difficulties that teachers face in teaching multilevel English classes, and started to commence studies examining factors leading to such classes and what 4.

(13) effective practices could be employed in teaching such classes. In the year of 2003, at the request of Ministry of Education, Chang, Chou, Chen, Yeh, Lin and Hsu (2003) conducted a nation-wide study to investigate factors contributed to the bimodal distribution of students’ English abilities. In the research report, Chang et al. indicated that in addition to the normal class grouping policy, the development gaps between urban and rural areas, the socioeconomic gaps among families, the instruction of teachers, and the learning of students both in and outside of the classroom were also contributory factors of the phenomenon. In the following years, with an attempt to gain a better understanding of what. 治 政 specific difficulties that teachers encounter and how 大they address them, several 立 researchers in Taiwan also conducted studies to investigate teachers’ teaching in large ‧ 國. 學. multilevel classrooms. By employing questionnaire as his main research instrument,. ‧. Chen (2009) examined the perceptions of 204 elementary school English teachers in. sit. y. Nat. southern Taiwan toward large multilevel classes and their reported remedial practices.. io. er. Likewise, Liu (2004) also investigated the teaching difficulties that eight junior high. al. school expert teachers of four different subjects encountered in large multilevel. n. iv n C classrooms and the effective instructional that they adopted to deal with the h e n g cstrategies hi U problems. But unlike Chen (2009), Liu (2004) collected data with interviews and classroom observations and derived more in-depth analyses to answer her research puzzles. Based on the assumption that the use of classroom management strategies could address the difficulties that teachers encountered in teaching large multilevel classes, Chiang (2003) examined with a two-phase study design how 14 EFL elementary school teachers with varying amount of teaching experience employed such strategies in their classrooms. These studies together inform our understanding of teaching large multilevel English classes in Taiwan; however, they in various degrees fail to account for the 5.

(14) cognitive dimension of teaching and how this dimension of teaching is related to actual practice of teaching, which are viewed to be central to a deepened understanding of a teacher and her teaching (Borg, 2006; Freeman, 2002). Chen (2009) only devoted to derive general patterns of teachers’ perceptions toward their difficulties and remedial practices. Liu (2004) despite adopting classroom observation as one method of data collection, presented only teachers’ reported difficulties and practices in teaching English in multilevel classrooms. Chiang (2003), despite conducting a two-phase study to investigate the effective strategies that primary school English teachers employed in teaching multilevel classes, focused mainly on. 治 政 teachers’ shared practices with limited consideration of their 大personal cognitions. 立 Two more recent studies (Lu, 2011; Teng, 2009), with the recognition of the ‧ 國. 學. interactive relationship between teachers’ cognition and classroom practice,. ‧. investigated the beliefs and practices that teachers held in teaching large multilevel. sit. y. Nat. English classes. However, as Teng (2009) only examined the beliefs and practices of. io. er. two experienced elementary school English teachers, she could hardly explain the. al. correspondence between the two teachers’ beliefs and practices further other than the. n. iv n C attribution to their rich teaching experiences. though studying the issue h e nLug(2011), chi U. more holistically by incorporating the development process of the teachers’ beliefs in large multilevel English classes, failed to produce a genuine picture and understanding due to her somewhat inappropriate method design and data presentation.. 1.2 Significance of the Study In order to provide a more genuine, holistic and in-depth understanding of teaching English in multilevel classrooms, this study explored the learning to teach and teaching experiences of a junior high school English teacher in multilevel 6.

(15) classrooms and examined the cognitions and practices she developed in teaching and learning to teach such classes. The findings may inform teachers, researchers and other stakeholders of multilevel English classes about teaching and learning in multilevel English classes.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 7. i Un. v.

(16) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 8. i Un. v.

(17) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW The following literature review aims to provide an orientation for the present study and it covers five major sections. The first section begins with an introduction to existing research on language teacher cognition, which includes elaboration of the notion of language teacher cognition, a brief introduction of teacher cognition research where language teacher cognition research draws its conceptual basis, the numerous perspectives from which this field of research have been studied and the perspective from which the study was undertaken. Then, the second section elaborates. 治 政 Borg’s (2006) framework of elements and processes 大in language teacher cognition, 立 which was employed as the theoretical framework of this study, and the existing ‧ 國. 學. studies that have been conducted through the theoretical lens of Borg’s framework.. ‧. The third and fourth sections respectively examine the issue of teaching English in. sit. y. Nat. multilevel classes in general and a focused discussion of the issue in Taiwan. These. io. al. er. four sections then lead to the final section, which illustrates the rationale and the. n. research questions of the present study.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 2.1 Research on Language Teacher Cognition Over the years, as increasing recognition has been given to the characterization of teachers as active thinking agents and knowing professionals (Borg, 2003, 2006, 2009; Johnson & Golombek, 2002; Woods, 1996), more and more researchers have engaged themselves in studying the psychological dimension of teaching and its impacts on teachers’ actual practice of teaching. Studying respectively from various perspectives and on different aspects of the issue, researchers have proposed a multitude of terms to describe, wholly or partially, the psychological context of teaching, which resulted in a “definitional confusion” (Eisenhart, Shrum, Harding & 9.

(18) Cuthbert, 1988). Given the complex, multidimensional and intertwined nature of the psychological dimension of teaching, Borg (2003, 2006, 2009), in studying this issue in the context of language education, proposed language teacher cognition as a collective term, to refer to the unobservable mental dimension of teaching, which includes “what language teachers think, know, and believe (Borg, 2006, p.1)”. According to Borg (2003, 2006, 2009) and Freeman (2002), research on language teacher cognition emerged from general educational teacher cognition research and did not start to take hold until the mid 1990s. As the conceptual basis of language teacher cognition research, general education research on teacher cognition. 治 政 has a longer history, which traces its origin back to the 1970s. 大 Before the 1970s, the 立 field of educational research was fairly under the sway of a positivist epistemological ‧ 國. 學. perspective (Borg, 2006, 2009; Freeman, 2002; Johnson, 2009). Knowledge is. ‧. understood to be objective and generalizable from a positivist view. Consequently, the. sit. y. Nat. educational research at that time was dominated by a large amount of. io. er. “process-product” research, which sought to identify effective teaching behaviors that. al. would lead to greater learning outcomes so that other teachers could follow the. n. iv n C behaviors normatively. However, such h an epistemologicalU e n g c h i perspective started to suffer growing criticism since the 1970s. In a critical response to the positivist paradigm, an interpretative epistemological perspective began to take hold in educational research. An interpretative perspective considers knowledge to be socially constructed and hard to be abstracted from the social practices and contexts where it emerged. Adopting an interpretative perspective in conducting research on teaching thus means the need to go beyond the descriptions of teaching behaviors and to delve into what and how teachers know about their work and why they do what they do in their teaching contexts. From this stance, it was revealed that how and why teachers do what they do were largely informed by their previous experiences and teaching contexts they are 10.

(19) situated, which characterizes a sociocultural perspective of teacher learning. And it is based on such a perspective about human learning, either partially or fully, that a substantial amount of research on teacher cognition evolves (Johnson, 2009). As Borg (2006, 2009) noted, teacher cognition research was initiated at the year of 1975, when one group of experts in the field of education convened in a conference and argued that researchers needed to study the relationships between teachers’ classroom practices and the thoughts that underpinned their practices so to have a better understanding of teachers. From then on, there was a steady growth of studies examining the cognitions of teachers, which over the years have shifted their. 治 政 predominant perspectives. In the early years of the 大 inquiry into teacher cognition, 立 studies mainly focused on teachers’ planning, judgment and decision-making, which ‧ 國. 學. however were later recognized to be not sufficiently holistic in studying teacher. ‧. cognition. From the 1980s, works that adopted a more holistic perspective to view. sit. y. Nat. teacher cognition and practice began to emerge; these included studies of teachers’. io. er. knowledge (Clandinin & Connelly, 1987; Connelly, Clandinin & He, 1997; Elbaz,. al. n. 1981; Shulman, 1986, 1987), learning to teach process (Calderhead, 1988; Carter,. ni C h Thompson, 1992). 1990), and beliefs (Pajares, 1992; U engchi. v. It is based on the research of teacher cognition in the context of mainstream education that language teacher cognition research develops (Borg, 2003, 2006, 2009; Freeman, 2002). Drawing on the various perspectives from which studies about teacher cognition in the general education context have studied, research on language teacher cognition has been conducted from a substantial number of views to study the mental lives of language teachers, including reasons for instructional decisions, rationale for improvisational teaching, beliefs, and practical knowledge, to name a few. Informed by the general educational research on teachers’ decision-making, a 11.

(20) number of studies about language teacher cognition focused on the examination of factors accounting for the decisions language teachers made with regard to their instruction and improvisational teaching (Johnson, 1992; Osam & Balbay, 2004; Richards, 1998; Smith, 1996; Ulichny, 1996; Yang, 2010). In the early stage of inquiry into the decisions teachers made prior to and during their teaching, the research focus was placed primarily on the identification of the immediate antecedents to the decisions (Johnson, 1992; Richards, 1998; Smith, 1996). For example, in examining the instructions and decisions of six pre-service ESL teachers, Johnson (1992) found that the instructional decisions of these teachers were largely. 治 政 influenced by “unexpected student behavior (p. 527)”, a finding 大 that was also reported 立 in Smith (1996). In her study of the pedagogical decisions of a group of experienced ‧ 國. 學. ESL teachers, Smith noted that “student affective states (p. 210)” were of major. ‧. concern in the teachers’ interactive decisions. It did not seem to be later that the. sit. y. Nat. research on language teachers’ decision making started to examine the issue more. io. er. holistically by relating the decisions that teachers made with the larger other than the. al. immediate contexts where the teachers were situated (Osam & Balbay, 2004; Yang,. n. iv n C 2010). In the studies of Osam and Balbay and Yang (2010), the researchers h e(2004) ngchi U. found that the institutional and ethic cultures that dominated the teaching contexts of the teachers could also have a major impact on their decision making. In addition to the teachers’ decision making, a portion of research on language teacher cognition, drawing from mainstream educational research on teachers’ knowledge, examined language teacher cognition more holistically from this perspective (Ariogul, 2007; Chen, 2005; Chou, 2008; Golombek, 1998; Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2011; Sun, 2012; Tsang, 2004; Woods, 1996). Employing the notion of personal practical knowledge proposed by Clandinin and Connelly (1987), Golombek (1998) studied the personal practical knowledge (PPK) of two ESL 12.

(21) teachers and found their PPK, which was composed of knowledge of self, subject matter, instruction and context and was constructed from their previous learning and teaching experiences, informed their practice by serving as an interpretive framework and shaping their practice. Examining the PPK of an immigrant Chinese language teacher, Sun (2012) also confirmed the impact of previous personal experiences on a teacher’s PPK, but added “how profoundly an immigrant teacher’s identity and cultural heritage can shape personal practical knowledge and teaching practice (p. 766)”. Also focusing on the examination of the knowledge of language teachers, Woods (1996) however employed a different concept, that is, beliefs, assumptions and. 治 政 knowledge (BAK) in an attempt to recognize the interconnected nature within. Using 大 立 this notion to examine the teachers’ prior experiences and interpretation of classroom ‧ 國. 學. events, Woods (1996) found a teacher’s BAK evolved through her learning and. ‧. teaching experiences and played a role in both the “perceiving and thinking about (p.. sit. y. Nat. 247)” the classroom events and the “structuring and organizing (p. 247)” of the. io. er. instructional decisions.. al. Like Woods, Borg (2003, 2006) in reviewing the existing literature on teacher. n. iv n C cognition in the contexts of mainstream and language teaching, recognized h e n geducation chi U the interwoven nature of the various constructs within the mental lives of teachers. Hence, instead of compartmentalizing the sub-constructs for the sake of clarity, Borg (2003, 2006) proposed and used teacher cognition as an inclusive term to “embrace the complexity of teachers’ mental lives (Borg, 2003, p. 86)”. Based on the studies he reviewed, Borg (2006) also proposed a framework for the conceptualization and investigation of language teacher cognition to illustrate the interrelated and interactive relationships among teachers’ learning, cognition and classroom practice. As the present study aimed to explore a Taiwanese junior high school English teacher’s teaching in large multilevel English classes holistically, Borg’s (2006) framework of 13.

(22) elements and processes in language teacher cognition was thus employed as the theoretical framework of this study to assist the researcher in examining the teacher participant’s cognitions, practices and learning-to-teach process in large multilevel English classes from a sociocultural perspective in an in-depth and holistic manner. In the following section, the framework of Borg and the studies that have been conducted based on the framework are elaborated.. 2.2 Borg’s (2006) Framework of Elements and Processes in Language Teacher Cognition. 治 政 Based on his review of existing studies on language 大 teacher cognition, Borg 立 (2006) proposed a framework to conceptualize the cognitions of language teachers, ‧ 國. 學. how they developed and related their cognitions to their classroom practices. The. ‧. framework could be represented by the following figure.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Figure 1. Elements and processes in language teacher cognition (from Borg, 2006, p. 283) 14.

(23) According to Borg (2006), language teacher cognition played a critical role in teachers’ professional lives. Language teachers had cognitions about many aspects of their work, which ranged from personal understandings of self and colleagues, to those of subject matter, curricula, materials, activities, assessment and context and more generally to those of teaching, teachers, learning and learners. Language teachers constructed and reconstructed these cognitions throughout their professional lives. During the schooling phase, language teachers might develop preconceptions about teaching from their interactions with significant others such as their parents and teachers. Then, they carried these preconceptions to teacher education programs,. 治 政 where their existing cognitions and their participation 大in the program exercised a 立 mutual impact on each other. The mutually interactional relationship also existed ‧ 國. 學. between language teachers’ cognitions and classroom practices, which were mediated. ‧. by the interaction between their cognitions and the contextual factors in their teaching. sit. y. Nat. contexts that were so critical and integral to the teachers’ classroom practices. In. io. al. er. addition to the contextual factors, language teachers’ prior teaching experiences could. n. also have an impact on their cognitions and practices in an unconscious manner or through conscious reflection.C h. engchi. i Un. v. With this framework, Borg provided an orientation for conceptualizing existing and conducting further research on language teacher cognition. A review of existing studies revealed that Borg’s (2006) framework of elements and processes in language teacher cognition have been employed by a number of recent studies, with many of them being thesis and dissertation studies (Attia, 2011; Martinez, 2011; Mori, 2011; Nishino, 2009, 2012; Sasajima, 2012; Shih, 2011). To investigate the cognition and use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) of three in-service teachers of teaching Arabic to speakers of other languages (TASOL) in Egypt, Attia (2011) utilized Borg’s (2006) framework as a conceptual springboard to explore her 15.

(24) research problems. Based on data collected from a variety of sources, she found that teachers’ cognitions about teaching, learning and themselves, which were developed and redeveloped from their prior experiences, mediated their practices of integrating ICT into instruction and determined how they perceived and responded to the challenges within their teaching context. While affirming the role that the framework of elements and processes in language teacher cognition played in guiding her exploration of the relationships between teacher cognitions and use of ICT, Attia (2011) still proposed four major modifications to the framework to make it more reflective of her study. First, she downgraded the elements that language teachers had. 治 政 cognitions about to the overarching concept of ICT. Second, 大she replaced the 立 schooling and professional coursework boxes with boxes of early experiences as ‧ 國. 學. learner and teacher education to make the framework more accurately descriptive of. ‧. the elements within her study. Third, she connected the boxes of early experiences as. sit. y. Nat. learner and teacher education through the box of language teacher cognition in an. io. er. attempt to highlight the relationships among the three. Lastly, she positioned. al. contextual factors in teaching around both classroom practice and language teacher. n. iv n C cognition to emphasize that language teacher was studied within the context. h e ncognition gchi U In another dissertation study (Martinez, 2011), Borg’s (2006) framework was also employed to be one of the theoretical lenses to view the research puzzles. In her study, Martinez (2011) used the conceptual frameworks of social constructivism and language teacher cognition to examine the cognitions of five first-year teacher assistants (TAs) and how they developed and redeveloped their cognitions and practices during their learning-to-teach process in a university in the U.S.. In the research process, Martinez (2011) recognized the value of the language teacher cognition framework in guiding her to conceptualize the mental processes through which teachers made sense of their prior experiences and classroom practices. But she 16.

(25) also found Borg’s (2006) model to be rather limited as it did not account for the learning and teaching experiences that language teachers developed outside of the classroom, which she believed could also be critical forces that shaped the cognitions of language teachers. In addition to the aforementioned two studies, another four studies conducted in the context of Eastern countries such as Japan and Taiwan also adopted Borg’s (2006) model of elements and processes in language teacher cognition as their conceptual framework or a basis to formulate their own frameworks. In employing a mixed method research design to investigate the beliefs and practices with regard to. 治 政 communicative language teaching (CLT) of Japanese 大high school teachers, Nishino 立 (2009, 2012) drew on Borg’s (2003) framework to develop a hypothesized path model ‧ 國. 學. of her own. Based on Borg’s (2003) framework, which was grounded in his review of. ‧. mainstream educational teacher cognition research and was the basis of his later. sit. y. Nat. framework proposed in the year of 2006, Nishino formulated a path model of teacher. io. er. beliefs and practices to expound the relationships among teachers’ beliefs, practices,. al. prior learning and teacher training experiences, perceived teaching efficacy and. n. iv n C contextual factors. With her research Nishino found her results were more in h e nresults, gchi U line with the framework of Borg (2006) than that of Borg (2003), and emphasized the closely interconnected relationship between teachers’ classroom practices and their teaching contexts. Recognizing from her study that teachers’ classroom practices were highly contextualized, Nishino also suggested that the framework of Borg (2006) might be more suitable to be used as a conceptual framework of qualitative studies. Also studied from a teacher cognition perspective, Mori (2011) adopted the framework of Borg (2006) as the theoretical lens to view how the cognitions of two post-secondary English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers in Japan shaped their corrective feedback practices. Noticing that the inquiry into teachers’ corrective 17.

(26) feedback practices from such perspective was still rather limited, Mori, with her study, stressed how study teachers’ cognitions that underpinned their corrective feedback practices could produce a more nuanced understanding of the practices and the wider contexts where these practices were adopted. While Nishino (2009, 2012) and Mori (2011) affirmed the value of Borg’s (2006) framework in guiding them to examine teachers’ cognitions within their contexts, Sasajima (2012) in utilizing the language teacher cognition framework to investigate the cognitions of Japanese secondary school English teachers, however, found it hard to reflect the situated, social and local nature of the cognitions of his participants, and thus proposed a modified framework. 治 政 which was developed based on that of Borg (2006). Another 大study that was also 立 conducted in the context of secondary schools employed Borg’s framework of ‧ 國. 學. elements and processes in language teacher cognition to examine the cognitions and. ‧. practices of two Taiwanese English teachers with varying amount of teaching. sit. y. Nat. experiences in teaching aboriginal junior high school students in a remedial program. io. er. (Shih, 2011). With the research findings, Shih confirmed Borg’s (2006) framework. al. concerning the impacts of the teachers’ prior learning and teaching experiences and. n. iv n C teaching contexts on their cognitions. However, found the framework of Borg h e n gshe chi U. (2006) to be not sufficiently detailed in terms of its explication of contextual factors. While Borg used contextual factors to refer to “the social, psychological and environmental realities of the school and classroom (Borg, 2003, p. 94)” generally, Shih noted that the roles that teachers played in their teaching contexts could also had an impact on the power they enjoyed and in turn the classroom practices they employed in the contexts. In her study, Shih thus suggested that a more elaborate definition of contextual factors should be included in the framework. The review of studies that have been conducted through the theoretical lens of Borg’s (2006) framework showed that Borg (2006)’s framework of elements and 18.

(27) processes in language teacher cognition could be of considerable value in guiding researchers in conceptualizing language teachers’ cognitions, how they developed and related their cognitions to their classroom practices. As the current study aimed to develop a holistic and in-depth understanding of a Taiwanese junior high school English teacher’s psychological and actual practice of teaching in large multilevel English classes, Borg’s (2006) framework was taken as the conceptual framework that guided the researcher throughout the research process. In the following section, a general introduction is given to multilevel classes and studies concerning teaching English in such classes.. 立. 政 治 大. 2.3 Teaching English in Multilevel Classrooms. ‧ 國. 學. Multilevel classes, also known as mixed-ability or heterogeneous classes. ‧. (Baurain & Phan, 2010), are defined by Hess (2001) as “the kinds of classes that have. sit. y. Nat. been roughly arranged according to ability, or simply classes that have been arranged. io. er. by age-group with no thought to language ability (p.2).” The issue of teaching English. al. in multilevel classrooms has attracted particular attention because of the many. n. iv n C problems reported by teachers in classes. The teaching difficulties vary hteaching e n g csuch hi U somewhat as the teaching contexts differ, but generally the reported problems include difficulties of managing classroom effectively, of meeting the various needs and enhancing the motivation and interest of students with adequate materials and activities, of paying sufficient individual attention to students, and of assessing students effectively and appropriately (Baurain & Phan, 2010; Chang, 2009; Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Hess, 2001; Liu, 2004; Lu, 2011; Maddalena, 2002; Mathews-Aydinli & Van Horne, 2006; Teng, 2009; Ur, 1991; Xanthou & Pavlou, 2008). To address these difficulties, many teachers and researchers have invested 19.

(28) considerable time and energy to investigate and report effective practices and approaches, hoping to identify what constituted effective teaching in such classrooms so to transfer such knowledge to other teachers. Two approaches reported to be effective in multilevel classrooms are differentiated instruction and cooperative learning. Differentiated instruction is an approach to proactively organizing teaching and learning that provide students with multiple access to the curriculum in response to student readiness, interest and learning profiles. With a scaffolding system inherent in the differentiated instruction, it is said to be able to meet the individual needs of learners in multilevel classrooms (King-Shaver & Hunter, 2003; Quiocho & Ulanoff,. 治 政 2009; Rothenberg & Fisher, 2007; Tomlinson, 1999; Tomlinson, 大 2001). Likewise, 立 cooperative learning is also reported to be conducive to satisfying the diverse needs of ‧ 國. 學. individuals through student cooperation (MacDonald & Smith, 2010). In addition to. ‧. the two approaches, effective practices in addressing difficulties in teaching English. sit. y. Nat. to multilevel classes include practices such as conducting needs analysis prior to. io. er. teaching, using classroom management strategies, using grouping strategies flexibly,. al. asking higher achievers to provide peer tutoring, providing self-access materials,. n. iv n C using multilevel tasks and assessment and leveled teaching materials and h eadopting ngchi U homework (Chang, 2009; Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Hess, 2001; Liu, 2004; Lu, 2011; Mathews-Aydinli & Van Horne, 2006; Roberts, 2007; Shank & Terrill, 1995; Teng, 2009; Ur, 1991; Xanthou & Pavlou, 2008). Despite the substantial coverage, most of the literature on teaching English in multilevel classrooms, however, is not research-based. Of the relevant literature that the researcher reviewed, only eight articles are research-based. Among these, Freedman et al. (2005) considered the reservation that people had about the practice of untracking; commenced a three-year research study to examine an experienced teacher, Delp’s teaching in an untracked English literacy class in the U.S. to 20.

(29) understand how to effectively meet the various needs of diverse students in untracked classrooms from the perspectives of both teacher and students. Their review of relevant literature revealed that a number of such studies focused on and emphasized the importance of implementing heterogeneous cooperative learning groups to accommodate student diversity. However, in investigating the cognitive and actual practice of instruction of how Delp taught English literary works to a group of 30 academically and socioculturally diverse students throughout a semester, the researchers found that instead of using small cooperative learning groups advocated widely by the researchers, Delp mainly employed whole-class multimodal activities. 治 政 combined with individual teacher-student interactions 大in class. Freedman et al. hence 立 suggested what truly mattered in the success of Delp’s teaching in the untracked ‧ 國. 學. classroom might be a set of principles grounded in Vygotskian and Bakhtinian. ‧. theories rather than the participant structures that she utilized in class. These. sit. y. Nat. principles included “building a long-term curriculum, which promotes the recycling. io. er. of structures and ideas, with room for ever-deepening levels of complexity;. al. considering learners to be in control of their learning and building structures that. n. iv n C support them in challenging themselves; a learning community that respects h e n gbuilding chi U and makes productive use of diverse contributions from varied learners; providing opportunities for diverse ways of learning; providing support to individuals as needed; challenging all students, and keeping learners actively involved (pp. 118-119)”. In this way, the researchers concluded that the recommendations that seemed more useful were not specific suggestions about participant structures but “general principles, supported by examples that provide a variety of activities for teachers to choose from and that provide stimulus for teachers to invent their own activity systems, with their own participant and activity structures (p. 118)”. Although Freedman et al. (2005) provided insightful analysis with their holistic 21.

(30) and in-depth investigation, their study, nonetheless, was conducted in English literacy class whose focus was on teaching English literacy through literature studies, which rendered itself rather hard to shed light on teaching EFL in multilevel classrooms. To have a deepened understanding of the issue, one may need to undertake a review of studies more directly concerning teaching English as a language to multilevel classes. Out of the recognition of the numerous difficulties in teaching English to multilevel classes, two studies were also conducted to investigate what practices could work effectively in the context of EFL multilevel classrooms. Xanthou and Pavlou (2008), based on a review of related literature, conducted a mixed-method research. 治 政 design study to examine how 114 EFL teachers of public primary 大 schools in Cyprus 立 dealt with teaching multilevel classes. By consulting a considerable portion of ‧ 國. 學. research on how to effectively teach multilevel English classes, Xanthou and Pavlou. ‧. formulated a questionnaire and hypothesized that flexible grouping methods,. sit. y. Nat. cooperative and communicative activities, word games and various differentiated. io. er. tasks might properly accommodate the varying English abilities among the students.. al. To supplement the research findings from the questionnaire data provided by the 114. n. iv n C EFL school teachers, the researchers also six classroom observations of a h econducted ngchi U Level 1 class in an urban public primary school. With the analyses of the. questionnaire and observational data, Xanthou and Pavlou confirmed their hypothesis suggesting that flexible use of grouping strategies, cooperative activities, open-ended and differentiated communicative tasks and games could be capable of accommodating the various needs of students with diverse English proficiency levels. To encourage and sustain teachers’ incorporation of these practices into their classes, Xanthou and Pavlou also proposed that more teaching hours should be allowed for teaching in such classrooms. Likewise, Maddalena (2002) affirmed Xanthou and Pavlou’s finding of the value of student collaboration. Maddalena (2002) in teaching 22.

(31) English to a group of students with diverse proficiency levels in Japan, found that it was hard to take care of the various needs of students with different proficiency levels. To solve the problems encountered, Maddalena conducted action research to study how the students and the teacher, that is, himself, perceived the use of advanced learners as teaching assistants With data obtained through a questionnaire and classroom discussions, he reported that most students, regardless of their proficiency levels, were in favor of and benefited from this device. Maddalena hence suggested that advanced learners could serve as teaching assistants offering aid to their lower-level peers in the multilevel class.. 治 政 Despite of their provision of some understandings 大 of teaching English in 立 multilevel classrooms, the two studies of Xanthou and Pavlou (2008) and Maddalena ‧ 國. 學. (2002) offered only a general or incomplete picture of the issues being studied. By. ‧. employing questionnaire as their main data collection method, Xanthou and Pavlou. sit. y. Nat. (2008) provided a general account of the experiences and views of the 114 EFL. io. er. teachers in Cyprus on how to deal with multilevel English classes. However, they. al. could hardly offer further information about how and why each of those teachers. n. iv n C utilized such practices, that is, the dimension of teaching that underpinned h ecognitive ngchi U their actual teaching of practice. Similarly, Maddalena (2002), by affording findings mostly from students’ perspectives, also provided few specific details about his cognitions and practices of using advanced learners as teaching assistants in teaching the multilevel class. With a hope to achieve a more holistic and in-depth understanding of teaching English in multilevel classrooms, in the following section, the researcher elaborates the issues further with relevant studies conducted in Taiwan.. 2.4 Teaching English in Large Multilevel Classrooms in Taiwan 23.

(32) According to the Compulsory Education Law promulgated in 2004, students in all elementary and junior high schools in Taiwan should be randomly grouped based on normal class grouping so to promote students’ adaptive learning. Along the implementation of the policy was the inevitable accompaniment of multilevel English classes (Chang, 2009). According to some domestic researchers (Chang et al., 2003; Tsai, 2008), in addition to the policy, a variety of other factors resulted in varying English abilities among students, including the development gaps between urban and rural areas, the socioeconomic gaps among families, the instruction of teachers, and the learning of students both in and outside of the classroom. Multilevel English. 治 政 abilities among students were hence no new phenomenon.大 However, in recent years, 立 such multilevelness of students’ English abilities has been further intensified with the ‧ 國. 學. fact that more and more students started learning English in private English institutes. ‧. before receiving formal English education at school (Chen, 2009; Chiang, 2003; Liu,. sit. y. Nat. 2004; Lu, 2011; Teng, 2009; Tsai, 2008).. io. er. Besides, most of the English classes in elementary and secondary schools in. al. Taiwan are not only multilevel, but also large (Hess, 2001; LoCastro, 2001; Ur, 1991),. n. iv n C which poses even more challenges to teachers’ Although there is no h e n ginstruction. chi U. consensus as to what a large class is, it is agreed by many that what class size is large or too large depends mainly on teachers’ perceptions (LoCastro, 2001). Many of the English classes in elementary and secondary schools in Taiwan are comprised of more than 30 students, and in some cases, even more than 40 students, which is considered by many teachers to be large classes (Liu, 2004; Lu, 2011; Teng, 2009). In teaching such large multilevel classes, teachers reported many teaching difficulties, which included not only the difficulties encountered in multilevel classes, but also some other pedagogical, management-related, and affective problems (LoCastro, 2001). Faced with such large multilevel English classes, several researchers in Taiwan 24.

(33) have thus commenced studies on teachers’ teaching in these contexts hoping to gain a better understanding of what specific difficulties they encountered and how they addressed those problems. Of these studies, Chen (2009) examined the perceptions of 204 elementary school English teachers in southern Taiwan toward large multilevel classes and their reported remedial practices. By asking his teacher participants to complete a questionnaire, Chen found that teachers of different age groups and levels of education and teaching in different contexts had dissimilar perceptions toward difficulties encountered in teaching large multilevel classes. Despite so, most of the teachers reported that they addressed the difficulties with similar practices. During. 治 政 in-class teaching, most of the teachers said they would 大 ask higher achieving students 立 to provide tutoring to their less competent peers, employ multiple assessments and ‧ 國. 學. textbooks of appropriate challenge levels to take care of the needs of students with. ‧. varying English proficiency levels. Many teachers also reported that they adopted. sit. y. Nat. additional practices to facilitate the learning of higher and lower achievers. With the. io. er. former group of students, the teachers provided them with supplementary learning. al. materials of more challenging levels, whereas with the latter group, they offered more. n. iv n C guidance, opportunities for practice, and remedial instruction to assist h e nmultimedia gchi U them in learning English. In another study, Chiang (2003) also explored what difficulties elementary school English teachers encountered in teaching large. multilevel classes and how they dealt with those problems. But unlike Chen (2009), Chiang (2003), based on an unarticulated assumption that proper use of classroom management strategies could effectively address the problems, focused mainly on what classroom management strategies that the teacher participants employed to cope with the difficulties they faced in teaching large multilevel English classes. With a two-phase study design, she examined how 14 EFL elementary school teachers with varying amount of teaching experience employed such strategies in their classrooms. 25.

(34) In the first phase of her study, Chiang had telephone interviews with six first-year novice elementary school English teachers to understand what classroom management strategies were adopted in their classes. In the second phase, she conducted interviews and classroom observations of six more experienced teachers in two elementary schools in Northern Taiwan to examine the classroom management strategies they reported to use and they actually used to solve the difficulties they faced in large multilevel classes. From her study, she came to conclusions that both novice and experienced teachers had difficulties in teaching large multilevel classrooms and addressed the issue with various classroom management strategies. In view of the. 治 政 large multilevel classes accompanied by the normal class grouping 大 policy, Liu (2004) 立 also conducted a study to investigate what specific difficulties and practices that eight ‧ 國. 學. expert teachers of four different subjects encountered and adopted in large multilevel. ‧. classes in the context of junior high schools. With qualitative data elicited from. sit. y. Nat. teacher interviews and classroom observation, she found that the two expert English. io. er. teachers encountered similar difficulties and held the same beliefs in encouraging. al. students and innovating teaching but resorted to different instructional practices. Liu. n. iv n C concluded her study by arguing that teachers engage themselves in teacher h e nshould gchi U. development activities such as workshops, seminars and communication with expert teachers to develop and enhance their professionalism. Drawing from teachers’ perspectives, the studies of Chen (2009), Chiang (2003) and Liu (2004) together informed our understanding of teaching large multilevel English classes in Taiwan; however, none of these studies accounted much for the cognitive dimension of teaching, which according to Freeman (2002) are fundamental to a holistic and in-depth understanding of a teacher and her teaching as they form the “hidden side of teaching (p.1)”. By utilizing quantitative questionnaire data as the main research data of his study, Chen (2009) could only derive general patterns of 26.

(35) teachers’ perceptions toward their difficulties and remedial practices and could hardly provided us with further understandings of how the teachers’ perceptions impacted the instructional practices they adopted. Chiang (2003), despite employing a two-phase qualitative case study design to compare novice and experienced teachers’ reported and actual teaching, seemed to focus largely on identifying the shared classroom management strategies that the teachers employed and did not delve much into the cognitive basis that underpinned each teacher’s instructional strategies. Similarly, Liu (2004) though adopting classroom observation as one source of data collection, did not present the similarities and differences between teachers’ reported and actual. 治 政 classroom practices in teaching large multilevel classes, 大 nor did she examine them 立 with much reference to the teachers’ cognitions. ‧ 國. 學. Also aiming at exploring teacher’s teaching in large multilevel English classes,. ‧. two more recent studies, Teng (2009) and Lu (2011), studied the issue more. sit. y. Nat. holistically by investigating not only teachers’ practices, but also the cognitions they. io. er. held in teaching large multilevel classes. To study teachers’ beliefs and practices in. al. teaching large multilevel English classes, Teng (2009) collected data from. n. iv n C questionnaire, interviews and classroom of two experienced elementary h e n gobservations chi U school English teachers. From the data, she found that the two veteran teachers, like many other teachers, encountered difficulties in teaching large multilevel English classes, but they were capable of implementing effective practices, such as providing guided practice, employing flexible grouping methods and assigning multilevel assignments, that reflected their beliefs. In discussing the two teachers’ beliefs and practices, Teng (2009) attributed the congruence between the teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices to their rich teaching experiences but did not further investigate these experiences from which the two teachers developed and redeveloped their beliefs. Lu (2011) in studying four experienced junior high school English teachers’ 27.

(36) beliefs and practices, incorporated the development process of the teachers’ beliefs to make her investigation more holistic. From her study, she found that the four teachers constructed their beliefs based on their prior learning and teaching experiences, and could not always implement practices congruent to their beliefs owing to some contextual factors. For example, one teacher reported that the pressure from the school and students’ parents was one force that kept her from carrying out practices that reflected her beliefs. But despite so, the teachers could still enumerate several teaching practices, such as employing effective classroom management strategies, having students participate in cooperative learning, providing various activities and. 治 政 peer tutoring, that they found to work effectively within their 大teaching contexts. In 立 this way, by studying the teacher participants’ beliefs, practices and the factors that ‧ 國. 學. impacted the formation of beliefs and implementation of practices, Lu provided a. ‧. more holistic picture of what teaching in large multilevel English classes was.. sit. y. Nat. Nevertheless, her interview protocols which comprised several leading questions and. io. al. n. beliefs hampered the contribution of her study.. Ch. engchi. er. failure to deconstruct teacher beliefs into specific beliefs and to distinguish these. i Un. v. 2.5 Rationale and Research Questions of the Present Study As the previous review indicated, many studies on teaching English in multilevel classrooms only placed their research focus on the identification of effective teaching practices in such contexts. However, according to existing language teacher cognition research, it is quite evident that if one attempts to acquire a more holistic and in-depth understanding of a language teacher’s teaching, one can not merely examine her actual practice of teaching in the classroom, but has to study the cognitive dimension of teaching that underpins her classroom practices as well. Hence, this study, in an attempt to gain a deepened understanding of teaching in large 28.

(37) multilevel English classrooms, aimed to investigate the cognitions and practices that a junior high school English teacher held and employed in teaching large multilevel English classes. But unlike the previously reviewed studies on teaching English in large multilevel classrooms that were mostly conducted to identify effective classroom practices and the pedagogical beliefs and thoughts that supported these practices, this study hoped to delve into the issue in a way that was more open-ended and thorough by employing Borg’s (2006) framework of elements and processes in language teacher cognition to view the teacher’s teaching practices, the content and development process of cognitions that she held in large multilevel English classrooms holistically.. 立. 政 治 大. Two research questions were used to guide the current study:. ‧ 國. 學. 1. What cognitions did one Taiwanese junior high school teacher hold in teaching. ‧. large multilevel English classes? How did she develop such cognitions?. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2. How did the teacher’s cognitions interact with her actual classroom practices?. Ch. engchi. 29. i Un. v.

(38) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 30. i Un. v.

(39) CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY This chapter illustrates the methodology whereby this study was conducted. It covers four major sections, and begins with the first section which elaborates the research design of the current study. The second section describes the background information of the participants of the study, including the teacher participant and the students in the three classes that she taught. The third and four sections respectively note down how the research data were collected and analyzed.. 3.1 Research Design. 立. 政 治 大. This study aimed to explore the cognitions and practices of a junior high school. ‧ 國. 學. English teacher by examining her teaching and learning-to-teach experiences in large. ‧. multilevel classrooms. The complex and multifaceted nature and the research interests. sit. y. Nat. of this study (Hood, 2009; Merriam, 2009; van Lier, 2005) suggest that a qualitative. io. er. case study serves as an appropriate research design. A case study is defined by Merriam (2009) as the study of a “bounded system (p.40)” and by Yin (2009) as “an. al. n. iv n C empirical inquiry that investigates phenomenon in depth within its h ea contemporary ngchi U real-life context when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (p.18). In this study, the researcher hoped to study the “bounded. system,” that is, how one junior high school English teacher, with her cognitions that were constructed and reconstructed from her previous learning and teaching experiences, taught in large multilevel classrooms, with a case study design, as which affords knowledge that is concrete, contextual, and open for interpretation (Merriam, 2009) that is required to answer the research questions. Various sets of data were collected to derive in-depth and holistic understandings of teaching large multilevel English classes. 31.

(40) 3.2 Participants Teacher Participant The teacher participant of the current study, Joy (pseudonym), was an expert teacher who had rich experiences in teaching and other education-related activities and work. She was invited to participate in the study for two main reasons. First, Joy was an experienced teacher who had extensive experiences in teaching large multilevel English classes. Besides, she was an expert teacher who by the time the researcher commenced this study, had been appraised highly by many teachers,. 治 政 students and school administrators and won several awards大 for her expertise and 立 commitment to teaching. In addition, she had been assisting organizations such as the ‧ 國. 學. English Advisory Committee for Junior High School in Taipei, Taipei Teachers’. ‧. Association, National Teachers’ Association, and Ministry of Education in. sit. y. Nat. undertaking education-related work. The work that she had been engaging in touched. io. er. a variety of issues, one of which was teaching in large multilevel English classes.. al. Considering the vast experiences and understandings that Joy had accumulated about. n. iv n C teaching in large multilevel English classes, earnestly invited her to be h e nthegresearcher chi U the teacher participant of the present study. Joy was a 44-year-old female teacher who had accumulated 20 years of teaching experience by the time of the study. She grew up and received elementary. and secondary school education in eastern Taiwan. Then, she continued her studies in a university of education situated in central Taiwan, where she majored in English. However, at that time, most of the courses there did not interest her. After graduating from the university, since she did not find much passion in teaching, she did not engage herself in the work of teaching, like many of her classmates did. It was not until one year after graduation that she started teaching at the repeated request of a 32.

(41) school inspector living nearby. On the request of the school inspector, Joy started her teaching career by working as a substitute English teacher in La La junior high school, which was a fairly remote junior high school in eastern Taiwan with great difficulties in recruiting teachers. Despite being recruited as an English teacher, Joy had to teach other subjects such as history and geography as well. After finishing the one-year substitute teaching, she received the offer to teach in an elementary school. Having spent three years teaching in two elementary schools both situated in northern Taiwan, she found herself more fond of teaching in junior high schools and again started her job hunting for teaching positions in junior high schools. In the next year, she. 治 政 obtained the admission to teach in a junior high school 大 in a remote area of central 立 Taiwan, where she came to feel restraint in the exam-oriented school, which thus ‧ 國. 學. drove her to apply for a teaching position in the Fa Fa junior high school. Fa Fa junior. ‧. high school was in an urban area of northern Taiwan; at the time of the study, Joy had. sit. y. Nat. been teaching there for 14 years.. io. er. In addition to the rich teaching experiences, Joy also had extensive. al. education-related work and learning experiences. In the year of 2001, Joy started her. n. iv n C learning in an in-service teacherheducation MA program e n g c h i U in northern Taiwan. In the. same year, she also began working for Taipei Teachers’ Association and as a member of the English Advisory Committee for Junior High School in Taipei. In the following years, she successively worked for National Teachers’ Association and Ministry of Education. But at the same time, she still taught a particular number of classes in Fa Fa junior high school. In the years of 2008, 2009 and 2012, Joy also earned the opportunity to attend three overseas educational visits. Among the three overseas educational visits, she considered the one she had to Holland, Belgium, and France in the year of 2008 to be the overseas educational visit experience that had the greatest impact on her cognitions and practices of teaching large multilevel English classes. 33.

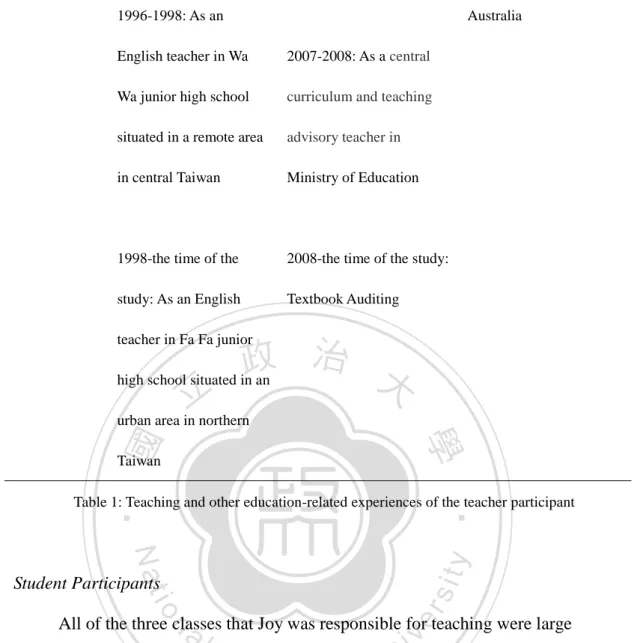

(42) Below is a table that summarizes Joy’s teaching and other education-related experiences in a chronological order.. Teacher. Teaching Experiences. Participant. Other Education-Related. Advanced Study and. Working Experiences. Overseas Educational Visit Experiences. 2001-2002: Taipei. 2001-2007: MA. substitute English. Teachers’ Association. in-service teacher. teacher in La La junior high school situated in a. education MA program 治 政 2001-2008: The English大. remote area in eastern. Advisory Committee for. 2006: Summer Study in. Junior High School in. Boston. 立. ‧. Taipei. 2008: Overseas. in Co Co elementary. io. al. n. school situated in an. urban area in northern Taiwan. sit. y. Nat. 1993-1995: As a teacher 2002-2003: National Teachers’ Association. Ch. engchi. educational visit to. er. Taiwan. 學. 1992-1993: As a. ‧ 國. Joy. Holland, Belgium and. iv n U France. 2003-2005: As a seed teacher of 9-Year. 2009: Overseas. 1995-1996: As a teacher. Integrated Curriculum in. educational visit to. in Bo Bo elementary. Ministry of Education. Germany and. school situated in an. Switzerland. urban area in northern. 2006-2007: Textbook. Taiwan. Editing for Ministry of. 2012: Overseas. Education. educational visit to. 34.

數據

Outline

相關文件

候用校長、候用主任、教師 甄選業務、考卷業務及試 務、教師介聘、外籍英語教 師及協同教學人員招募、推

To share strategies and experiences on new literacy practices and the use of information technology in the English classroom for supporting English learning and teaching

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

分類法,以此分類法評價高中數學教師的數學教學知識,探討其所展現的 SOTO 認知層次及其 發展的主要特徵。本研究採用質為主、量為輔的個案研究法,並參照自 Learning

Stone carvings from the Northern Song dynasty were mostly religion-oriented (namely Buddhism or Taoism), and today much of the research conducted on them has been derived from

language feature / patterns might you guide students to notice and help them infer rules or hypothesis... Breakout Room Activity 2: A grammar

• If we use the authentic biography to show grammar in context, which language features / patterns might we guide students to notice and help them infer rules or hypothesis.. •

認為它注重對四大師的研究而忽視支援這些大師布教活動的庶民之信仰的研 究。[13]