行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

亞洲多元宗教市場中的基督教與民主:台灣與南韓的比較

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2414-H-004-044- 執 行 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 96 年 10 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學政治學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 郭承天 計畫參與人員: 碩士級-專任助理:吳振嘉 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 96 年 10 月 31 日

Christianity and Democracy in Asian Pluralist

Religious Markets: Taiwan and South Korea

Cheng-tian Kuo

Director and Professor, Graduate Institute of Religious Studies Professor, Department of Political Science

National Chengchi University Taipei, TAIWAN 116

ctkuo@nccu.edu.tw

Prepared for delivery at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA, August 30th-September 3, 2006. Data analyzed in this paper were collected by the East Asia Barometer Project (2000-2004), which was co-directed by Profs. Fu Hu and Yun-han Chu and received major funding support from Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University. The Asian Barometer Project Office (www.asianbarometer.org) is solely responsible for the data distribution. I appreciate the assistance in providing data by the institutes and individuals aforementioned. The views expressed herein are my sole responsibility. The generous funding provided by the National Science Council of the Taiwanese government (NSC 95-2414-H-004 -044) made this research possible.

Abstract

Using the Taiwanese and South Korean samples of the 2000-2004 Asian Barometer dataset, this paper confirms the Christian democracy hypothesis that Christianity (including Catholicism) contributes to democratization by indoctrinating democratic values and behaviors to their believers. However, the statistical analyses also support the religious market hypothesis that the logic of competition in pluralistic religious markets compels various religions to converge on dominant democratic values and behaviors within each country, although different religions and different countries continue to vary in the degrees and aspects of democratic commitment. These findings offer a more optimistic view for the prospect of non-Christian “religious democracies” than what the current scholarship proposes.

I. Theoretical Hypotheses

This paper examines two prevalent theoretical hypotheses about the relationships between religion and democracy: the Christian democracy hypothesis and the religious market hypothesis. There is a long tradition in social sciences scholarship in support of the Christian democracy thesis that Christianity (including Catholicism) has a positive relationship with democracy. In the early nineteenth century, Alex de Tocqueville and Max Weber explained the establishment and consolidation of American democracy in terms of Protestant theology and practices (Tocqueville 1969; Weber 1978). The establishment of democracy further led to the “democratization of American Christianity” in the first 50 years of the new country (Hatch 1989).

The connection between democracy and Christianity attracted renewed interests of the academia in the 1970s when Catholic democracies in Latin America and Southern Europe fell like dominos. Along with other cases, scholars concluded that democracy seemed to prosper better in Protestant countries than in Catholic, Confucian, or Muslim countries. Nevertheless, in the “Third Wave of Democratization,” the Catholic Church played a critical role in the establishment of democracy in Poland, South Korea, the Philippines, and Latin American countries, while some Confucian countries and most Muslim countries remained resistant to democratization (Huntington 1991; Ostrom 1997; Jelen and Wilcox 2002; Gill 1998; Monsma and Soper 1997; Diamond and Plattner 2001). Impressed by the compatibility of Evangelism and democracy in many Third World countries, Peter L. Berger (1999: 14) argues that “the Evangelical resurgence is positively modernizing in most places where it occurs… [it serves] as schools for democracy and for social mobility.”

Theoretically, Christianity may contribute to democracy in three ways: it promotes democratic theology, democratic ecclesiology, and democratic participation. First, the Protestant theology upholds the ideas of “covenant,” “the priesthood of all believers” and “the freedom of conscience,” based on which government accountability, individual freedom, and political equality of modern democracy are built (Locke 1683, 1993; Morgan 1965; Shields 1958; Paine 1776, 1995; Witte 2000; Eidsmoe 1987). The progressive Catholicism after the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) espouses human rights, and the Latin American liberation theology further mixed the Catholic teaching with Marxism (Sigmund 1990; Gutiérrez 1988). These Protestant and progressive Catholic theologies provide religious legitimacy to democratic movements in various countries.

Secondly, when Max Weber and Alex de Tocqueville analyzed Protestantism, they discussed not only the theological component but also the democratic

ecclesiology that translated abstract liberal theology into concrete democratic practices. For instance, in America, abstract liberal theological arguments like covenant, the freedom of conscience, the priesthood of all believers, and the original sin found concrete expression in institutional forms within many Protestant churches. These included the protection of the freedom of speech, congregationalism, and the checks and balances between clergy and laity (Clark 1994; Nettels1963; Schlesinger 1968).

Thirdly, democratic theology and democratic ecclesiology encourage Christians’ democratic participation. Democratic theology provides a religious legitimacy to democratic participation, while democratic ecclesiology offers a “school for democracy” (Berger 1999: 14) to indoctrinate Christians with democratic values and practices.

Furthermore, the “social capital” theories (Putnam 1993; Wuthnow 1988) explain well how Christians are better equipped to contribute to democracy. Churches are non-traditional voluntary civic groups where members can learn democratic values and behaviors, as well as accumulate social capitals (networks) in order to influence public policies.

The religious market hypothesis suggests that competitive religious markets would compel non-democratic religions to converge on democratic values. The original version of the religious market hypothesis deals with the relationship between the plurality of religious markets and religiosity (Stark and Bainbridge 1985; Finke and Stark 1992; Finke and Stark 2000; Warner 1993). Religions compete for religious believers just like firms compete for consumers. The plurality of religious markets (many religions coexist) tends to encourage religiosity of all religious believers, because religious leaders are compelled to provide quality religious products (hymns, rituals, and compassion, etc.) to raise the level of religiosity, which increases the human and material resources of a religion in order to compete with other religions. By contrast, the “lazy monopoly” (one dominant religion exists in a country) discourages religiosity, because religious leaders become lazy to provide quality religious products, and believers would rather stay home instead of committing human and material resources to the religion.

This paper builds on the religious market hypothesis by arguing that the logic of competition also compels all religions to converge on dominant democratic values in order to keep or attract religious consumers. Political scientists have found that the establishment of a democracy has a significant positive impact on the citizen’s commitment to democracy (Diamond 1999). It will be difficult for religious leaders or elites to insist on non-democratic values when their believers are influenced by democracy in all aspects of their lives. When the plurality of religious market exists,

believers would transfer their memberships to another denomination or religion that is more democratic.

Recent studies of church-state relations in the new democracies of Europe and South America reveal that although Catholic churches contributed to the establishment of these new democracies, they are losing their believers to the more democratic Protestant churches, especially the Pentecostals (Gill 1998; Jelen and Cox 2002). Facing the new competitors in the religious market, Catholic churches have encouraged local parishes, among other reforms, to adopt more democratic forms of governing, including giving the lay believers a larger role in church decisions and religious ceremonies.

Although the pressure for convergence is large, various religions or denominations respond differently to the logic of competition, depending on their tradition, organizational structure, resources, and leadership. Therefore, we expect to see both convergence and divergence in a competitive religious market.

This paper plans to test both the Christian democracy hypothesis and the religious market hypothesis in the contexts of Taiwan and South Korea. These two countries are chosen for three reasons. One, both countries are similar in political, social, and economic background. Two, previous case studies of both countries demonstrate that Christians played an important role in the establishment of their new democracies. And three, both countries have very competitive religious markets. The next section explains the compatibilities of these two countries. The third section elaborates the statistical research design and methodology. The Fourth section reports and discusses the statistical results. The last section concludes the analyses.

II. Compatibilities of the Korean and Taiwanese Cases

A. Similar Political, Social, and Economic Background

In terms of political background, both countries have experienced a similar sequence of Japanese colonization, authoritarian rule, and democratization.1 Korea lost its sovereignty in 1905 when the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty was signed, and formally annexed by Japan in 1910. She gained her independence on 15 August, 1945. Afterwards, the country was first ruled by the aristocratic government of Syngman Rhee from 1948 to 1960, then, by the military regimes of Park Chunghee (1961-1979) and Chun Doohwan (1980-1987). The opposition movement did not gain control of the government until Kim Youngsam was elected President in December 1992.

1

For recently published books on Taiwanese politics, see Chao and Myers (1998), Roy (2003), and Rigger (2001). On Korean politics, see Kihl (2004), Kil and Moon (2001).

Taiwan was ceded by China to Japan in 1895 as compensation to a lost war. She was returned to the Chinese government on 25 October, 1945. After the nationalist (Kuomingtang; KMT) government lost the civil war against the communists in mainland China in 1949, it fled to Taiwan and maintained a martial law regime until 1987. In 1996, the Taiwanese were able to directly elect the President for the first time since 1945. But the first government turnover by the opposition party (Democratic Progressive Party; DPP) did not materialize until 2000.

In terms of social background, both societies inherit the legacy of Confucianism in various social institutions, such as families, schools, social organizations, and regional/community organizations. Confucian emphases on loyalty, patriarchy, authority, personal network, collective welfare, and consensus permeate these social institutions (Pye 1992; Rozman 2002).

Economically, both countries are mid-sized countries and experienced similar developmental stages. Taiwan has a population about 23 millions, living in an island about 36,000 squared kilometers, while South Korea has a population about 49 millions, inhibiting in the southern half of a peninsular about 98 squared kilometers.2 Both countries went through a short period of import-substitution industrialization in the 1950s, shifted to export-led industrialization in the early 1960s, and continued to upgrade their major export products from textiles, electrical appliances, to electronics.3 These successful economic developments brought up per capita GDP of Taiwan to US$16,308 and of Korea to US$15,676 in 2005.4

B. Similar Christian Contribution to Democracy

In Taiwan, the Christian community has been divided into two political camps. The “Mandarin churches,” which use the Mandarin dialect in church activities, tend to support the “pan-blue” parties that include the KMT and its splinter parties, the New Party and the People First Party. The Catholics and most of the Protestant denominations, such as Baptists, Quakers, Methodists, and Lutherans came to Taiwan with the refugee nationalist government after 1949. Therefore, they had played mostly the “priestly role” toward the KMT government until 2000 when the DPP took over the government (Kuo 2006).

The only exception is the Taiwan Presbyterian Church (TPC). It was established directly by Canadian and Scottish missionaries in the 19th century and had little to do with Chinese Christians. After the 228 ethnic violence in 1947, it held a religiously separatist stand toward the KMT government. A “doubling the church movement”

2

“CIA-The World Factbook,” https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/index.html, 7/25/06.

3

For recent works on Korean economic development, see Song (2003), Chung and Eichengreen

(2005). On Taiwanese economic development, see Amsden and Chu (2003), Berger and Lester (2005).

4

from the mid-1950s to mid-1960s helped the TPC leadership bond with the masses. The ouster of Taiwan from the UN in 1971 prompted the TPC to issue a series of public statements to urge for democratization, human rights protection, and Taiwan independence. The KMT government responded harshly against these political moves by sending spies to the church hierarchy, harassing pastors, and imprisoning those who participated in demonstrations. The PCT stood firm and continued to educate the public about human rights, democracy, and Taiwan independence (Rubinstein 2001). It was the sole religious group playing the role of political prophet during the martial law regime.

In South Korea, the majority of the Korean Christians are Presbyterians. Korean Christians are proud to mention that Korean churches were established by Koreans, not by missionaries. They were actively involved in politics ever since their introduction to Korea. In the late 19th century, they participated in the power struggle related to modernization (Kang 1997; Lancaster and Payne 1997). During the Japanese colonial rule, the Christian community became divided into two political camps between those who subordinated to the new ruler and those who fought against the colonial government. After the war, the first type of churches continued to subordinate to the aristocratic and military regimes, while the second type of churches maintained their “prophet role” in criticizing the authoritarian regimes. They organized anti-government societies, held demonstrations, published critical statements, and were harshly repressed by the authoritarian regimes.

The religious foundation of the Protestant opposition movement is the Minjung Theology. It took side with the people (minjung) who were exploited by capitalism, authoritarianism, and patriarchy (Suh 1991; Park 1993). These people were filled with “han” (resentment, regret, and alienation) caused by these injustices. Jesus was regarded as a political liberator to liberate these oppressed people, and Korean Christians were the chosen disciples to implement this political program.

The Korean Catholics did not join the opposition movement until the early 1970s. Afterwards, they were as active and critical of the government as their Protestant counterparts. Kim Daejung, the most respected opposition leader who became the President in 1997, is a Catholics.

C. Similar Competitive Religious Markets

Unlike their counterparts in other “Third-Wave democracies,” Korean and Taiwanese Christianity is not the dominant religion or the largest religion in their countries. Therefore, it is interesting to examine the validity of the Christian democracy hypothesis and the religious market hypothesis in these two truly competitive religious markets.

According to the Asian Barometer dataset, which is explained in the next section, the major religions in Taiwan are Folk Religions (39.9%), Buddhism (24.5%), Daoism (11.1%), Protestantism (5.7%), and Catholicism (2.5); another 15.6% of the respondents do not identify with any religion.5 In South Korea, the major religions are Buddhism (24.4%), Protestantism (18.5%), Catholicism (8.1%), and Folk Religions (0.5%), while 48.5% do not identify with any religion.

III. Research Design and Methodology

The dataset analyzed in this paper comes from the Asian Barometer project. It covers seventeen East and South Asian countries or territories. Using the multi-stage-stratified random sampling method, about 1200 adult respondents aged 20 and above are interviewed, face-to-face, in each country, which provides a minimum confidence interval of plus or minus 3 percent at 95 percent probability. The Taiwanese survey was carried out in 2001 with 1415 cases, while the Korean survey was completed in 2003 with 1500 cases. Further information about the Asian Barometer project can be obtained at the website www.asianbarometer.org.

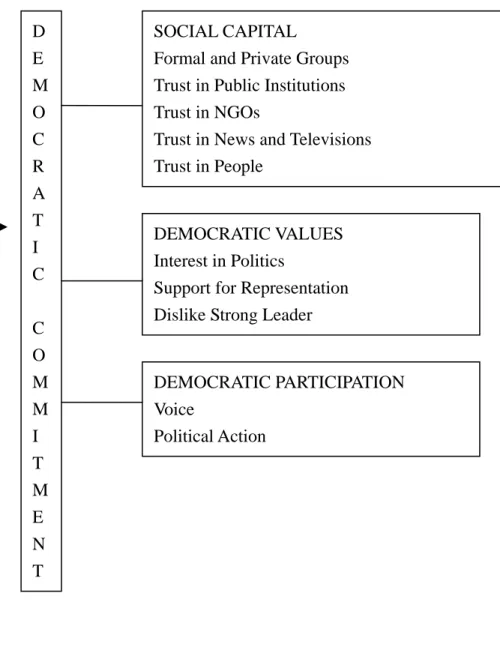

The research design of this paper is summarized by Figure 1. The core hypothesis is that people’s Belief affects their Democratic Commitment, which includes Social Capital, Democratic Values, and Democratic Participation. Control Variables include Education, Income, Gender, Age, and Country. The coding of these variables is explained below.

For the Beliefs variable, I recode the answers to the question (SE006) “Do you regard yourself as belonging to any particular religion?” into four dummy variables: Buddhism, Christianity/Catholicism/Islam, Folk Religion/Daoism, and Atheism. Christianity, Catholicism, and Islam are merged together for several reasons: one, current literature argues that Christianity and Catholicism are more democratic than other religions are; two, the Korean survey does not pick up any Muslim, while the Taiwanese survey includes only one Muslim case; and three, while the case numbers of Korean Catholics and Protestants are large enough for statistical analysis respectively, the numbers of Taiwanese Catholics (35 cases) and Protestants (80 cases) are relatively small. Similarly, both Folk Religion (564 cases) and Daoism (157 cases) are fairly represented in the Taiwanese survey; however, the Korean survey has only

5

According to Kuo (2006), the percentage of Taiwanese “none-believers” might have been

exaggerated. When asked “do you worship other deities such as Mazu, earth god, Guangong, or other deities,” more than half of these none-believers would reply yes. The Korean none-believers might exhibit a similar tendency, as will be explained below. Since the Asian Barometer project does not cross-examine the respondent’s belief with this additional question, the current percentages of the survey are adopted.

eight cases of Folk Religion and none of Daoism. According to Korean Overseas Information Service (1986: 11), this is a common problem when Western survey questions are translated into Korean language. Shamanism is a popular practice among Korean people. But most Koreans would not admit that the Shamanist practice is a form of Daoism or Folk Religion, as most of their Taiwanese counterparts would. Therefore, many Koreans (728 cases) would choose None (recoded as Atheism) as their religious identification. Since the major focus of this paper is about Christianity and Catholicism, the blurring line between Atheism and Folk Religion/Daoism is not a major concern here. For the same reason, the dummy variable of Christianity/Catholicism/Islam is treated as the default variable.

However, the interview of Korean Atheists prevents us from performing other important tests about the impact of religiosity on democratic values. While Taiwanese interviewers posed the question about religiosity to all Taiwanese respondents (including self-proclaimed Atheists), it seems that their Korean counterparts did the same to believers of various religions but skipped the Korean Atheists.6 This difference in interview procedure generates a colinearity problem when both the variables of Atheism and religiosity are on the right-hand side of an equation. It also makes the statistical analysis of the combined Korea-Taiwan samples unreliable.

There are three groups of dependent variables: Social Capital, Democratic Values, and Democratic Participation. Among the Social Capital variables, “Formal and Private Groups” combines the numbers of formal and private groups of which a respondent is a member. “Trust in Public Institutions” combines the scores of relevant variables (Q007-10) together, using the Factor Reduction Method (varimax rotation, principal component extraction) as a reference to select the most relevant variables. These Public Institutions include courts, national government, political parties, and parliament. “Trust in NGOs” is a recoded variable of the question “How much trust do you have in non-governmental organizations?” (Q018). Based on the above Factor Reduction Method, “Trust in News and Televisions” combines the scores of Q015 and Q016, which ask the respondent “how much trust do you have in” news and televisions, respectively. “Trust in People” is a recoded variable of Q024, which asks the respondent whether “most people can be trusted?” All of these Social Capital variables are coded in such a way that the higher scores mean higher levels of Social Capital.

Among the second group of dependent variable Democratic Values, “Interest in Politics” is a recoded variable of Q056, which asks the respondent “How interested

6

The religiosity question (SE007) asks the respondent: “How often do you practice religious services or rituals these days?” The answers are “At least twice a week,” “Once a week,” “Once a month,” “ Only on special holy days,” “ Once a year,” “Hardly ever,” “Never,” and “Don’t know.” There are no other religiosity questions in the questionnaire.

would you say you are interested in politics?” Based on the above Factor Reduction Method, “Support for Representation” combines the scores of Q121-124, which ask the respondents how much they agree or disagree with the following statements: “We should get rid of parliament and elections and have a strong leader decide things” (Q121), “No opposition party should be allowed to compete for power” (Q122), “The military should come in to govern the country” (Q123), and “We should get rid of parliament and elections and have the experts decide everything” (Q124). It is recoded in such a way that the higher score means the respondent’s higher level of support for representative institutions. Similarly, “Dislike Strong Leader” combines the scores of Q133, Q134, and Q138, which ask the respondent whether they agree or not with the statements that “Government leaders are like the head of a family; we should all follow their decisions” (Q133), “The government should decide whether certain ideas should be allowed to be discussed in society” (Q134), and “If we have political leaders who are morally upright, we can let them decide everything” (Q138). The score is recoded to show that higher scores mean stronger disagreements with these statements, and therefore, higher levels of democratic values.

The third group of dependent variable is Democratic Participation. Using the above Factor Reduction Method, “Voice” combines the scores of Q075-77, which ask the respondent how often they contacted elected legislative representatives (Q075), political parties or other political organizations (Q076), and NGOs (Q077). Similarly, “Political Action” combines the scores of Q029 and Q030, which asks the respondent in the last national election: “Did you attend a campaign meeting or rally?” (Q029) and “Did you try to persuade others to vote for a certain candidate or party?” (Q030).

The Control Variables include Education, Income, Gender, Age, and Country. Education is recoded from SE005b, which consists of four levels of education: illiterate, primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education. Income is recoded from SE009, which divides the respondents into five income groups. Gender recodes SE002 into a dummy variable with “1” for male and “0” for female. Age is recoded from SE003, which divides the respondents into twelve age groups. Country variable recodes the variable “country” into a dummy variable with “1” for Taiwan and “0” for South Korea.

This paper uses the Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) regression method to test the effects of Beliefs on the variables of Social Capital, Democratic Values, and Democratic Participation. Three models are applied to each dependent variable: Model 1 runs the OLS without Control Variables; Model 2 includes Education, Income, Gender, and Age; and Model 3 further adds Country to the Control Variables. Model 1 verifies the Christian democracy hypothesis that believers of Judeo-Christianity tend to have higher levels of democratic commitment than other

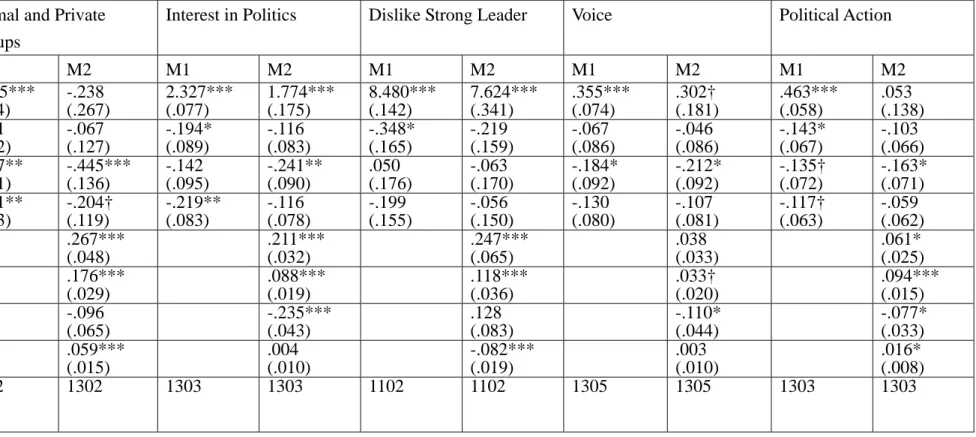

believers do. Model 2 provides a further examination about whether the religious effect comes from the religion itself or from the education, income, gender, or age attributes of believers. Model 3 examines the religious market hypothesis that various religions in a country tend to converge on democratic values but can be different from their counterparts in another country (see Table 1 and Table 2).

After the combined sample of Korea and Taiwan are examined, Models 1-3 are applied to the same set of variables (Models 1 and 2, but not Model 3) for the Korean and Taiwanese samples separately. The purpose is to find out the differences between the Korean and Taiwanese cases, as well as their differences with the combined sample. Ultimately, it allows us to examine the religious market hypothesis in more details. This research design is enlightened by Inglehart and Welzel (2005, Chapter 10)’s solution to the problem of cross-level analysis.

IV. Statistical Results and Discussion

A. The Combined Sample

Based upon Table 1 and Table 2 of the combined sample of the Korean and Taiwanese cases, seven observations can be derived. First, before the control variable of “Country” is introduced into the equations, Christians tend to have higher levels of “Trust in NGOs,” “Trust in People,” “Interest in Politics,” and “Support for Representation” than all other religious believers do. All the coefficients of other religions in Models 2 in these tests are negative, although not all are statistically significant. This seems to partially support the Christian democracy hypothesis that Christians are more democratic than other religious believers are.

[Table 1 and Table 2 about here.]

However, secondly, Christians do not surpass all other religious believers in the variables of “Formal and Private Groups,” “Trust in Public Institutions,” and “Dislike Strong Leaders.” Christians tend to join fewer formal and private groups than Buddhists and Folk Religion/Daoism believers do. It is possible that churches usually provide more social networks, or what Wuthnow (2002) calls “social bridging functions” than other religions do. In addition to collective worship, there are Bible study groups, fellowships, ministries, group tours, charity works, and etc. that offer a variety of personal and social needs to church members. Therefore, Christians feel less need to join other formal or private groups.

Atheists do (although below the significance level), but believers of Folk/Daoism rank even higher than the Christians do. One possible explanation is that Folk Religions and Daoism are influenced by traditional Confucianism which has a strong emphasis on citizen’s subordination to public officials. The survey question cannot tell the difference between a democratic trust of and an authoritarian obedience to public officials.

Korean and Taiwanese Christians tend to be less hostile to Strong Leaders than other religious believers, especially those of Folk Religion/Daoism do. It is possible that many Christian pastors and Catholic priests in these two countries still run a tight ship over their churches. The image of a strong religious leadership seems to spill over to a strong political leadership in the minds of Christians. By contrast, temples of Folk Religion and Daoism are rarely led by clergy. Therefore, the spill-over effect might be weaker.

Thirdly, Buddhists are not significantly different from Christians in their democratic commitment. Buddhists rank significantly higher than Christians do in the variables of “Formal and Private Groups” and “Voice.” The coefficient of Buddhists in the variable of “Dislike Strong Leader” is positive, although it is not statistically significant. Although the coefficients of Buddhists in the variables of “Trust in Public Institutions,” “Trust in NGOs,” “Trust in People,” “Interest in Politics,” and “Political Action” are negative, they are not statistically significant either.

Fourthly, as compared to Christians, Atheists do not have a score that is significantly higher in any of the Social Capital, Democratic Values, and Democratic Participation variables. Although the coefficients of Atheists in the variables of “Support for Representation” and “Trust in News and Televisions” are positive, they are not statistically significant.

Fifthly, although Folk Religion/Daoism believers rank significantly lower than Christians do in the variables of “Trust in NGOs,” “Trust in News and Televisions,” “Trust in People,” “Interest in Politics,” and “Support for Representation,” they rank significantly higher than Christians do in “Formal and Private Groups,” “Trust in Public Institutions,” and “Dislike Strong Leader.” It seems that Folk Religion/Daoism believers are able to contribute to democratic consolidation from different perspectives.

Sixthly, once the control variable “Country” is introduced into the equations, most of the significant differences between Christians and other religious believers disappear. The only differences remain are that of Atheism and Folk Religion/Daoism in “Trust in People,” and of Atheism in “Political Action.” The coefficients of “Country” are significant in all equations except for in “Voice” and “Trust in People.” This observation seems to support the religious market hypothesis that within the

same country, different religions would converge on the popular democratic values in order to survive the competitive religious market.

The “Country” variable also reveals that Koreans and Taiwanese are democratic in different ways. While the Taiwanese perform significantly better than the Koreans in the variables of “Formal and Private Groups,” “Trust in Public Institutions,” “Dislike Strong Leader,” and “Political Action,” the Koreans perform better in the variables of “Trust in NGOs,” “Trust in News and Televisions,” “Interest in Politics,” and “Support for Representation.”

Finally, for other control variables, the respondents’ Education and Income levels are positively related to their levels of democratic values in the variables of “Formal and Private Groups,” “Trust in People,” “Interest in Politics,” “Support for Representation,” “Dislike Strong Leader,” and “Political Action,” even after the Country variable is introduced into the equations. Female respondents tend to have lower levels of democratic commitment than their male counterparts do. “Age” effect is not consistent across different equations.

After the analysis of the combined sample, it will be interesting to explore the relationships between Beliefs and Democratic Commitment in Taiwan and South Korea separately, in order to further examine both the Christian democracy and religious market hypotheses. Is each country different from the other country, as well as different from the combined sample?

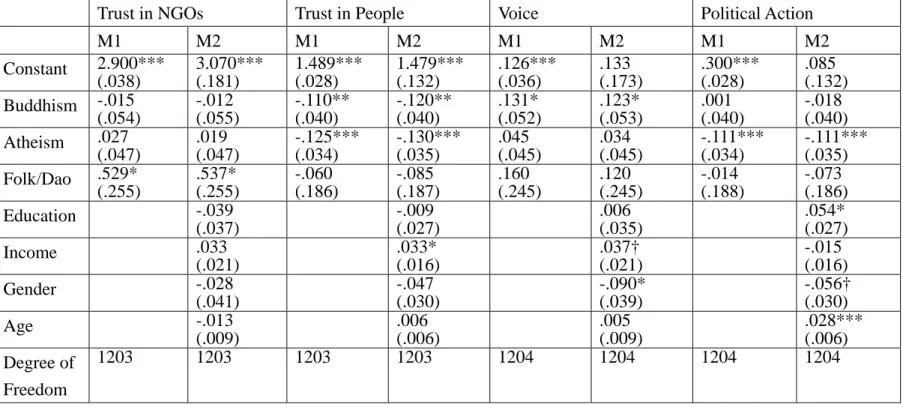

B. The Taiwanese Sample

Comparing Table 3 to Tables 1 and 2, the relationships between Beliefs and Democratic Commitment in Taiwan bear some similarities with and differences from the combined sample. In terms of similarities, first, Taiwanese Christians tend to have a higher level of democratic commitment than other religious believers in all equations presented here. The coefficients of all other religions are negative, although many of them are not statistically significant. This statistical result provides a partial support for the Christian democracy hypothesis that Christians are more committed to democracy than other religious believers do.

Secondly, the statistical results do not reveal that Taiwanese Buddhists and Folk Religion/Daoism believers are significantly less committed to democracy than their Christian counterparts are. Although their coefficients are negative, none is statistically significant after controlling for Education, Income, Gender, and Age. This finding is consistent with the religious market hypothesis that religions tend to converge on dominant democratic values in a competitive religious market.

Thirdly, Taiwanese Atheists are very likely to be less committed to democracy than their Christian counterparts are. In Models 2 of “Group Number,” “Interest in

Politics,” “Voice,” and “Political Action,” their coefficients are negative and statistically significantly. The coefficient of Atheists in “Dislike Strong Leader” is negative but not statistically significant.

[Table 3 about here]

In terms of the difference between the Taiwanese sample and the combined sample, Taiwanese Christians are not significantly different from other religions in the variables of “Trust in Public Institutions,” “Trust in NGOs,” “Trust in News and Televisions,” “Trust in People,” and “Support for Representation,” whose statistics are, therefore, not shown in Table 3. These statistically none-significant results tend to support the religious market hypothesis.

C. The Korean Sample

The Korean sample also bears some similarities with and differences from not only the combined sample but also the Taiwanese sample (see Table 4). In terms of the similarities with the combined sample, first, Korean Christians rank higher than all other religious believers in the variables of “Trust in People” and “Political Action.” The coefficients of all other religions are negative, and half of them are statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the Christian democracy hypothesis.

Secondly, however, Korean Christians do not rank the highest among all religions in the variables of “Trust in NGOs” and “Voice.” Korean believers of Folk Religion/Daoism rank significantly higher than their Christian counterparts do in “Trust in NGOs,” while Korean Buddhists rank significantly higher than the Christians do in “Voice.” This statistical result provides a partial support for the religious market hypothesis.

[Table 4 about here]

The difference between the Korean sample and the combined sample further supports the religious market hypothesis. Korean Christians are not significantly different from other religious leaders in the six variables that are not listed in Table 4 but are so in Tables 1 and 2, which include “Formal and Private Groups,” “Trust in Public Institutions,” “Trust in News and Televisions,” “Interest in Politics,” “Support for Representation,” and “Dislike Strong Leader.”

There are very few similarities between the Korean sample and the Taiwanese sample. The only similarity is that Christians in both countries rank the highest in the variable of “Political Action” and is significantly higher than Atheists are. This

statistical result is also consistent with that of the combined sample.

VI. Conclusion

Statistical analyses of the Korean and Taiwanese samples in the Asian Barometer dataset confirm both the Christian democracy hypothesis and the religious market hypothesis. The Christian democracy hypothesis assumes that Christian theology, organizational structure, and ethics have a positive impact on their believers’ democratic commitment. Overall speaking, Christians tend to have higher levels of democratic commitment than believers of other religions do, particularly when compared to Atheists. In most of the OLS regression models regarding Social Capital, Democratic Values, and Democratic Participation, coefficients of other religions are negative as expected by the Christian democracy hypothesis, although their significance levels vary.

However, Christians do not rank higher in democratic commitment in all aspects of democratic commitment. The religious market hypothesis suggests that other religions would converge on dominant democratic values, but also with some divergences. Buddhists are somewhat less committed to democracy than Christians are in most regression models, but outperform Christian in some models. Believers of Folk Religions and Daoism are even less committed to democracy than Buddhists are, but they have higher scores than Christians have in a few models.

A stronger support for the religious market hypothesis comes from the fact that after introducing the control variable of Country, most of the statistical differences among religions disappear. Christians are not significantly different from believers of other religions in each country. When the Korean and Taiwanese samples are analyzed separately, a similar conclusion is reached with more detailed information. In terms of both the number of regression models and significance levels, Christians are less different from their counterparts are in the same country. Finally, different religious believers and people in these two countries can be both democratic but in different ways.

One important implication of this paper is a more optimistic future for the prospect of religious democracies in non-Christian countries. Current literature on Christian democracy seems to imply that democracy works well only with Christianity. Huntington’s “Clashes of Civilizations” further predicts the inevitability of severe conflicts among religions/civilizations. However, even among the supposedly-anti-democracy Muslim countries, Abdou Filali-Ansary (2001: 40-41) points out that Islam has several features that are compatible with modern democratic

values, such as Unitarianism, individualism, egalitarianism, republicanism, and rule-based governance. John L. Esposito and John O. Voll (1996) argue that Islamic fundamentalism is not necessarily incompatible with democracy; it depends more on strategic calculations of major political and religious groups than on theological doctrines or values. Mark Tessler (2003) has found statistical evidence that, contrary to American academic perception, there is a strong popular support for democracy in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Algeria where fundamentalist movements are significant political forces. Steven Ryan Hofmann (2004) survey Muslims in other eight countries and reach a similar conclusion that Islam and democracy is compatible at the micro-level.

By comparing different religions in Taiwan and South Korea, this paper provides a similar optimistic prospect for democratic development in non-Christian countries. In the era of globalization, major religions have started the process of convergence on major democratic values, although they vary in degrees and aspects of democracy. Instead of a black-and-white contrast between Christian democracies and non-Christian authoritarianism/theocracy, the future is more likely to be a colorful world of democracies with different religious flavors.

References:

Ahn, Sang Jin. 2001. Continuity and Transformation: Religious Synthesis in East Asia, New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Almond, Gabriel A., and Sidney Verba, eds. 1980. The Civic Culture Revisited. Canada: Little, Brown and Company.

Amsden, Alice H., and Wan-wen Chu. 2003. Beyond Late Development: Taiwan’s Upgrading Policies. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

An, Choi Hee. 2005. Korean Women and God: Experiencing God in a Multi-religious Colonial Context. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

Baker, Don. 1997. “From Pottery to Politics: The Transformation of Korean Catholicism.” In Lewis R. Lancaster, and Richard K. Payne, eds. Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea, Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp.127-167.

Bellah, Robert N., [et al.]. eds. 1996. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley and L.A.: University of California Press.

Berger, Peter L. ed. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Berger, Suzanne, and Richard K. Lester. Eds. 2005. Global Taiwan: Building Competitive Strengths in a New International Economy. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Chung, Jun Ki. 1995. “Christian Contextualization in Korea”. In Ho-Youn Kwon, eds. Korean Cultural Roots: Religion and Social Thought. Chicago: Integrated Technical Resources.

Clark, J.C.D. 1994. The Language of Liberty 1660-1832: Political Discourse and Social Dynamics in the Anglo-American World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, Donald N. 1997. “History and Religion in Modern Korea: The Case of Protestant Christianity.” In Lewis R. Lancaster, and Richard K. Payne, eds. Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea, Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp.169-213.

Diamond, Larry. 1999. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Diamond, Larry and Marc F. Plattner. ed. 2001. The Global Divergence of Democracie. Baltmore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Eidsmoe, John. 1987. Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of Our Founding Fathers. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Filali-Ansary, Abdou. 2001. “Muslims and Democracy.” In Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner, eds. The Global Divergence of Democracies. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 1992. The Churching of America, 1776-1990. New Brunswick, NJ: University of Rutgers Press.

---. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gill, Anthony James. 1998. Rendering Unto Caesar: The Catholic Church and the State in Latin America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grayson, James Huntley. 2002. Korea: A Religious History. New York: Routledge. Gutiérrez, Gustavo. 1988. A Theology of Liberation. 2nd ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis

Books.

Hatch, Nathan O. 1989. The Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hofmann, Steven Ryan. 2004. “Islam and Democracy: Micro-Level Indications of Compatibility,” Comparative Political Studies, 6 (6): 652-676.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jelen, Ted Gerard, and Clyde Wilcox. 2002. Religion and Politics in Comparative Perspective: The One, the Few, and the Many. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kang, Wi Jo. 1997. Christ and Caesar in Modern Korea: A History of Christianity and Politics. New York: State University of New York Press.

Keyes, Charles F., Laurel Kendall, and Helen Hardacre, eds. 1994. Asian visions of authority: religion and the modern states of East and Southeast Asia. Hononlulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Kil, Soong Hoom, and Chung-In Moon, eds. 2001. Understanding Korean Politics: An Introduction. New York: State University of New York Press.

Kihl, Young Whan. 2004. Transforming Korean Politics: Democracy, Reform, and Culture. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Kim, Kwang-Ok. 1997. “Ritual Forms and Religious Experiences: Protestant Christians in Contemporary Korean Political Context.” In Lewis R. Lancaster, and Richard K. Payne, eds. Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea, Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp.215-248.

Kim, Yong-Bok. 1987. “Minjung and Power: A Biblical and Theological Perspective on Doularchy (Servant hood).” The Christian Century, July 15-22, pp.628-630. Or found at http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=94.

Korean Overseas Information Service. 1986. Religions in Korea. Seoul: Korean Overseas Information Service.

Kuo, Cheng-tian. 2006. Religion and Democracy in Taiwan. Book manuscript.

Lancaster, Lewis R., and Richard K. Payne, eds. 1997. Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea, Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.

Locke, John. 1685, 1955. A Letter Concerning Toleration. New York: The Liberal Art Press.

Monsma, Stephen V., and J. Christoper Soper. 1997. The Challenge of Pluralism: Church and State in Five Democraticies. Lanham, MD: Rowman-Littlefield. Morgan, Edmund S. ed. 1965. Puritan Political Ideas 1558-1794. New York:

Bobbs-Merrill.

Nettels, Curtis P. 1963. The Roots of American Civilization: A History of American Colonial Life. 2nd ed. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, Vincent. 1997. The Meaning of Democracy and the Vulnerability of Democracies: A Response to Tocqueville’s Challenge. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Paine, Thomas. 1776, 1995. Rights of Man, Common Sense, and Other Political Writings. eds. Mark Philp. New York: Oxford University Press.

Park, A. Sung. 1988. “Minjung and Process Hermeneutics.” Process Studies, Vol.17, No.2, Summer, pp.118-126.

Park, Andrew Sung. 1993. The Wounded Heart of God: The Asian Concept of Han and Christian Doctrine of Sin. Nashville, TN: Abringdon Press.

Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Robert D., eds. 2002. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pye, Lucian. 1981. The Dynamics of Chinese Politics. Cambridge, MA: Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.

Rigger, Shelley. 2001. From Opposition to Power: Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Roy, Denny. 2003. Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rozman, Gilbert. 2002. “Can Confucianism Survive in an Age of Universalism and Globalization?” Pacific Affairs 75(1): 11-37.

Rubinstein, Murray A. 1991. The Protestant Community on Modern Taiwan: Mission, Seminary, and Church. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

---. 2001. “The Presbyterian Church in the Formation of Taiwan’s Democratic Society, 1945-2001.” American Asian Review 19 (4): 63-96.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. 1968. The Birth of the Nations: A Portrait of the American People on the Eve of Independence. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Shields, Currin V. 1958. Democracy and Catholicism in America. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Sigmund, P.E. 1990. Liberation Theology at the Crossroads: Democracy of Revolution? New York: Oxford University Press.

Sik, Chung Chai. 1991. “Confucian-Protestant Encounter in Korea: Two Cases of Westernization and De-westernization.” In Peter K.H. Lee, eds. Confucian-Christian Encounters in Historical and Contemporary Perspective. Lewiston, N.Y. : E. Mellen Press., pp.399-433.

Stark, Rodney, and Wiliam Sims Bainbridge. 1985. “A supply-side reinterpretation of the ‘secularization’ of Europe.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Relgion, 33: 230-252.

Suh, David Kwang-sun. 2001. The Korean Minjung in Christ. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Sunoo, Harold Hakwon, eds. 1976. Repressive State and Resisting Church: The Politics of CIA in South Korea. Missouri: Korean American Cultural Association, pp.24-55.

Tessler, Mark. 2003. “Do Islamic Orientations Influence Attitudes Toward Democracy in the Arab World: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Algeria,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 2 (Spring): 229-49.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1969. Democracy in America. eds. J.P. Mayer. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Waner, R.S. 1993. “Work in Progress toward a New Paradigm in the Sociology of Religion.” American Journal of Sociology, 98 (5): 1044-1093.

Weber, Marx. 1964. The Sociology of Religion. Boston: Beacon Press.

---. 1978. Economy and Society. ed. Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Witte, John, Jr. 2000. Religion and the American Constitutional Experiment: Essential Rights and Liberties. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1988. The Restructuring of American Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

---. 2002. “Religious Involvement and Status-bridging Social Capital.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41 (4): 669-675.

Yoon, Yee-Heum. 1997. “The Contemporary Religious Situation in Korea.” In Lewis R. Lancaster, and Richard K. Payne, eds. Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea, Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp.1-17.

Young, Kim, [et al.]. 1993. Reader in Korean Religion, Korea: The Academy of Korean Studies.

BELIEFS Buddhism Christianity/Catholicism/Islam (Default) Folk Religion/Daoism Atheism SOCIAL CAPITAL

Formal and Private Groups Trust in Public Institutions Trust in NGOs

Trust in News and Televisions Trust in People

DEMOCRATIC VALUES Interest in Politics

Support for Representation Dislike Strong Leader

DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION Voice Political Action CONTROL VARIABLES Education Income Gender Age

Country (Taiwan, S. Korea)

Figure 1. Research Design D

E M O C R A T I C C O M M I T M E N T

Table 1: Social Capital (Combined Sample)

Formal and Private Groups

Trust in Public Institutions

Trust in NGOs Trust in News and

Televisions Trust in People M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 Constant .829*** (.052) -.250 (.176) -.355* (.177) 8.408*** (.103) 9.481*** (.382) 9.335*** (.381) 2.857*** (.032) 3.064*** (.118) 3.133*** (.117) 5.410*** (.064) 6.191*** (.230) 6.471*** (.218) 1.465*** (.024) 1.215*** (.084) 1.198*** (.085) Buddhism .131* (.067) .165* (.065) .093 (.066) -.070 (.135) -.124 (.136) -.266† (.138) -.049 (.042) -.052 (.043) .005 (.043) -.170* (.083) -.192* (.083) .085 (.080) -.053† (.031) -.042 (.031) -.054† (.032) Atheism -.058 (.064) -.071 (.062) -.068 (.062) -.176 (.127) -.181 (.128) -.167 (.127) .008 (.040) -.001 (.040) -.003 (.040) .037 (.079) .029 (.079) .022 (.075) -.073* (.030) -.074* (.030) -.073* (.030) Folk/Dao .066 (.066) .167* (.065) -.033 (.075) .550*** (.139) .484*** (.140) .037 (.163) -.153*** (.042) -.166*** (.043) -.004 (.050) -.756*** (.084) -.808*** (.085) .006 (.093) -.090** (.031) -.065* (.031) -.098** (.036) Education .216*** (.034) .226*** (.034) -.253*** (.076) -.250*** (.076) -.025 (.023) -.029 (.023) -.158*** (.046) -.163*** (.043) .041* (.016) .042** (.016) Income .132*** (.020) .123*** (.020) -.032 (.043) -.057 (.043) -.004 (.013) .003 (.013) -.034 (.026) .003 (.025) .040*** (.010) .039*** (.010) Gender -.162*** (.042) -.159*** (.042) -.058 (.091) -.049 (.090) -.040 (.028) -.043 (.028) -.002 (.055) -.013 (.052) -.016 (.020) -.015 (.020) Age .055*** (.010) .058*** (.010) -.012 (.021) -.004 .021 -.009 (.006) -.012† (.006) -.030* (.013) -.043*** (.012) .008† (.005) .008† (.005) Country .275*** (.052) .591*** (.112) -.215*** (.034) -1.058*** (.063) .045† (.025) Degree of Freedom 2507 2507 2507 2191 2191 2191 2341 2341 2341 2336 2336 2336 2479 2479 2479 *** <0.001, ** <0.01, * <0.05, † <0.1

Table 2: Democratic Values and Participation (Combined Sample)

Interest in Politics Support for Representation

Dislike Strong Leader Voice Political Action

M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 Constant 2.345*** (.039) 1.930*** (.132) 1.987*** (.132) 12.978*** (.103) 11.921*** (.373) 12.082*** (.373) 7.858*** (.077) 6.917*** (.271) 6.729*** (.268) .186*** (.035) .145 (.123) .125 (.123) .342*** (.027) -.032 (.094) -.068 (.094) Buddhism -.115* (.051) -.082† (.049) -.043 (.050) -.358** (.134) -.270* (.133) -.133 (.135) -.078 (.100) .029 (.098) -.138 (.098) .087† (.045) .092* (.045) .078† (.046) -.031 (.035) -.025 (.035) -.049 (.036) Atheism -.064 (.048) -.109* (.047) -.111* (.047) .025 (.127) -.014 (.126) -.016 (.126) .059 (.095) .058 (0.92) .062 (.091) -.015 (.043) -.030 (.043) -.029 (.043) -.117*** (.034) -.121*** (.033) -.120*** (.033) Folk/Dao -.230*** (.050) -.165*** (.049) -.056 (.056) -.494*** (.137) -.420** (.137) -.019 (.158) .419*** (.101) .532*** (.099) .040 (.114) .039 (.045) .051 (.045) .012 (.052) .004 (.035) .033 (.035) -.035 (.040) Education .193*** (.025) .188*** (.025) .277*** (.074) .267*** (.073) .119* (.054) .128* (.053) .025 (.023) .027 (.024) .063*** (.018) .067*** (.018) Income .045** (.015) .049*** (.015) .182*** (.042) .202*** (.042) .267*** (.031) .245*** (.030) .037** (.014) .036* (.014) .057*** (.011) .055*** (.011) Gender -.277*** (.032) -.279*** (.032) -.157† (.089) -.163† (.088) .134* (.064) .139* (.063) -.101*** (.030) -.100*** (.030) -.069** (.023) -.068** (.023) Age .020** (.007) .019* (.007) -.008 (.021) -.015 (.020) -.053*** (.015) -.045** (.015) .005 (.007) .006 (.007) .024*** (.005) .025*** (.005) Country -.149*** (.039) -.536*** (.107) .655*** .078 .054 (.036) .093*** (.028) Degree of Freedom 2508 2508 2508 2274 2274 2274 2304 2304 2304 2510 2510 2510 2508 2508 2508 *** <0.001, ** <0.01, * <0.05, † <0.1

Table 3: Taiwanese Beliefs and Democratic Commitment

Formal and Private Groups

Interest in Politics Dislike Strong Leader Voice Political Action

M1 M2 M1 M2 M1 M2 M1 M2 M1 M2 Constant 1.255*** (.114) -.238 (.267) 2.327*** (.077) 1.774*** (.175) 8.480*** (.142) 7.624*** (.341) .355*** (.074) .302† (.181) .463*** (.058) .053 (.138) Buddhism -.161 (.132) -.067 (.127) -.194* (.089) -.116 (.083) -.348* (.165) -.219 (.159) -.067 (.086) -.046 (.086) -.143* (.067) -.103 (.066) Atheism -.377** (.141) -.445*** (.136) -.142 (.095) -.241** (.090) .050 (.176) -.063 (.170) -.184* (.092) -.212* (.092) -.135† (.072) -.163* (.071) Folk/Dao -.361** (.123) -.204† (.119) -.219** (.083) -.116 (.078) -.199 (.155) -.056 (.150) -.130 (.080) -.107 (.081) -.117† (.063) -.059 (.062) Education .267*** (.048) .211*** (.032) .247*** (.065) .038 (.033) .061* (.025) Income .176*** (.029) .088*** (.019) .118*** (.036) .033† (.020) .094*** (.015) Gender -.096 (.065) -.235*** (.043) .128 (.083) -.110* (.044) -.077* (.033) Age .059*** (.015) .004 (.010) -.082*** (.019) .003 (.010) .016* (.008) Degree of Freedom 1302 1302 1303 1303 1102 1102 1305 1305 1303 1303 *** <0.001, ** <0.01, * <0.05, † <0.1

Table 4: Korean Beliefs and Democratic Commitment

Trust in NGOs Trust in People Voice Political Action

M1 M2 M1 M2 M1 M2 M1 M2 Constant 2.900*** (.038) 3.070*** (.181) 1.489*** (.028) 1.479*** (.132) .126*** (.036) .133 (.173) .300*** (.028) .085 (.132) Buddhism -.015 (.054) -.012 (.055) -.110** (.040) -.120** (.040) .131* (.052) .123* (.053) .001 (.040) -.018 (.040) Atheism .027 (.047) .019 (.047) -.125*** (.034) -.130*** (.035) .045 (.045) .034 (.045) -.111*** (.034) -.111*** (.035) Folk/Dao .529* (.255) .537* (.255) -.060 (.186) -.085 (.187) .160 (.245) .120 (.245) -.014 (.188) -.073 (.186) Education -.039 (.037) -.009 (.027) .006 (.035) .054* (.027) Income .033 (.021) .033* (.016) .037† (.021) -.015 (.016) Gender -.028 (.041) -.047 (.030) -.090* (.039) -.056† (.030) Age -.013 (.009) .006 (.006) .005 (.009) .028*** (.006) Degree of Freedom 1203 1203 1203 1203 1204 1204 1204 1204 *** <0.001, ** <0.01, * <0.05, † <0.1