Teacher Professional Development: In-service

Teachers’ Motives, Perceptions and Concerns about

Teaching

CHAN Kwok-wai

Hong Kong Institute of Education

Abstract

This paper reports a survey study of in-service teachers’ motives, perceptions and concerns about teaching. Three motives were identified for their choosing of teaching as a career, viz. Intrinsic/Altruistic, Extrinsic/Job condition and Influence from others. Of the three motives, it was mostly Intrinsic/Altruistic motive which caused them to join the teaching profession. For the concerns, the teachers under study demonstrated a higher proportion of “concern for pupils” than “concern with self ”, suggesting they had progressed to a higher stage of professional development. The teachers were generally inclined towards the constructivist conceptions about teaching and learning. Nevertheless, they were pressurized by the tight teaching schedule and examination system, hence they still relied on didactic teaching and required students to memorize or recite what were taught in class.

Key words

Motives, Perceptions, Concerns, Professional development, In-service teachers

摘要

本論文報導一個調查在職教師的教學動機、看法和關注結果。選擇教學作為職業的動機,可分為內在 / 利 他,外在/工作條件和他人的影響。其中持內在/利他動機的人數最多。至於教師的關注焦點,“關注學生” 比“關注自己”的人數較多,顯示受調查的教師已進展到較高的專業發展階段。調查中的教師具信心、投 入,一般傾向於建構主義,然而,受壓於緊湊的教學程序和考試制度,仍然倚靠傳統的講學方法和需要學 生背誦和記憶課堂內所學。關鍵詞

動機、看法、關注焦點、專業發展、在職教師Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal《香港教師中心學報》 , Vol. 3

INTRODUCTION

The quality and performance of teachers are always considered as determining factors for the success of educational changes. Since the 1980s, the decline in quality of teachers has become an issue of concern to the education sector (Ballou & Podgursky, 1997; Education Commission, 1992). Scholars and educators have identif ied several major problems faced by recruitment and retention in the teaching profession, such as the teaching profession fails to attract bright young people (Murnane, 1991), a disproportionate share of higher ability teachers leave teaching to pursue for other careers (Ballou & Podgursky, 1997; Murnane, 1991), and the under-representation of both qualified minority teachers (Newby, Smith, Newby, & Miller, 1995) and males in the primary school teaching force (Johnston, Mckeown, & McEwen, 1999).

The first few years of teaching seem to be critical for novice or beginning teachers. Studies showed that a fairly high proportion of teachers leave the teaching profession in the early years of teaching and that some potential teachers do not join the teaching profession (Ingersoll, 2001; “Teacher Shortages”, 2001). In US, about one-fourth of teachers leave by the end of their second year (National Center for Education Statistics, 1992; cited in Smith, 1997). Some of them leave the teaching profession with disappointment and a sense of helplessness during these period. Several reasons may account for their leaving of the teaching profession, viz. the attractiveness of the teaching work which is related to their motives of taking up teaching as a career, the lack of support (assistance) related to their concerns about teaching, their perception about teaching before and after joining the teaching profession, which eventually may strengthen their desire to stay in the profession or to leave with disappointment and dissatisfaction.

It is obvious that the quality of teaching force is not governed only by the qualification, pedagogical knowledge and teaching skill of teachers, but also their enthusiasm, dedication and commitment in teaching. It is also determined by the motives of teachers to join the teaching team and how they perceive teaching as a career. At the same time, the teachers’ behaviour and teaching performance may also be influenced by their conceptions about teaching and learning and their confidence to teach.

Thus it is important to examine all these psychological constructs of teachers. The present study aims to study the professional development of in-service teachers from beginning to experienced teachers through investigating psychological constructs of in-service teacher education students in a tertiary institute of Hong Kong. The examined psychological constructs included in-service teachers’ motives in joining the teaching profession, their perception/conception about teaching and learning before and after taking up teaching and their focus of concerns in teaching. It is hoped that the results would provide valuable information to teacher educators and school authorities to assist professional development of teachers to promote their qualities and retain quality teachers in the teaching profession.

RELATED LITERATURE

The professional development of teachers can be considered in two aspects: cognitive and affective, both of which are important in determining teachers’ efficacy. The cognitive aspect refers to acquisition of pedgagogical knowledge and improved instructional skill, which will help teachers’ classroom teaching and management. In some way, this is influenced by the teachers’ beliefs and conceptions about teaching and

learning, for example, the role of teacher and pupils and the preferred way of teaching and learning.

The teachers’ commitment and dedication to the teaching career is an important affective component in teacher development. Probably they are influenced by the motives in taking up teaching as a career, the confidence level and concerns in teaching. Qualified teachers lacking the motives to teach often have little enthusiasm and driving force in their work. When a teacher has taught for sometime, work may become routinized. Consequently, interest decreases and the teacher fails to work to his/her full capacity and becomes less effective. In concrete terms, the result is lack of planning, resistance towards change and general negligence.

Researchers are keen to find out the reasons that may have affected students’ perceptions and career choices. There have been research literature on the views of student teachers (e.g. Johnston et. al, 1999; Reid & Caudwell, 1997), the career intentions of undergraduates and high/secondary school leavers and their perception of the teaching profession (e.g. Hutchinson & Johnson , 1994; Kyriacou & Coulthard, 2000). All these studies have helped teacher educators understand student teachers’ motives to teach.

Numerous studies on the motives of teachers entering the teaching profession have been conducted in US and Britain; however, few have been conducted in Asian countries (Yong, 1995). Research on prospective teachers in the US and Britain show that their major motives in choosing a teaching career are both altruistic and intrinsic. However, the study conducted by Yong (1995) shows that extrinsic motives were the determinants for teacher trainees entering into teaching in Brunei Darussalam. The results do not lend support to earlier research studies in Western countries. In a study of non-graduate pre-service teacher education students

in enrolling in the teacher education program were mainly extrinsic.

While the motives to choose teaching as a career is influential upon individual’s performance in classroom teaching, teachers’ concerns about teaching are often studied in the stages of teacher development. Fuller (1969) conceptualized teacher development around concerns expressed by teachers at different points in their professional experiences. She believed that concerns were reflective of strong motivators and of areas of great interest to the teacher (Heathcoat, 1997). Fuller’s (1969) model of concerns has been widely used in teacher education institutes as illustration of different stages of teacher professional development. In her studies, Fuller (1969) identified two categories of concerns - concerns with self and concerns with pupils. Student teachers and teachers in their first year consistently showed concerns with self (e.g. class management, acceptance by pupils and others), which are related to survival in the classroom. As teachers progressed along, teachers become increasingly concerned with their ability to manage the teaching tasks and their influence on pupils’ learning and development. That is, experienced and effective teachers tend to focus their concerns on pupils’ needs and development. Later, Fuller reorganized her early model of teacher development and theorized that teacher concerns could be classified into three distinct categories: “self concerns” which center around the individual’s concern for their own survival related to their teacher preparation program, including their teaching experience; “task concerns” which focus upon the duties that teachers must car ry out within the school environment; and “impact concerns” which are related to one’s ability to make a difference and be successful with his/her students and the teaching/learning process (Fuller, 1969; Fuller, Parsons, & Watkins, 1974). Fuller (1969) believed that as pre-service teachers moved

to task, then finally to impact concerns. Similar kinds of concerns changes are expected to be found in in-service teachers as they progress in the periods of teaching. The categories of teachers’ concepts hypothesized by Fuller (1969, 1974) have been demonstrated and partially supported in some other researchers’ work (Chan, 2002; Furlong & Maynard, 1995). It was reported that pre-service and beginning teachers have greater self concerns than those exhibited by in-service and experienced teachers (Adams, 1982; Kazelskis & Reeves, 1987). Teacher educators need to have a knowledge of pre-service and novice teachers’ concerns and to address their concerns in order to decrease the rates of attrition of teacher candidates within their progress (O’connor & Taylor,1992). Whether there is a cultural or social difference is also an interesting area of investigation.

Related to the teachers’ concer n is their confidence to teach. Weinstein (1989, 1990) has found that pre-service teachers in US are unrealistically optimistic about teaching before teaching practice. Although they agree with the concern of experienced teachers on class discipline, they are optimistic in handling class teaching and lay much value on teacher-pupils relationship. O’Connell’s (1994) study indicated that the first year teaching was not what the novice teachers expected and many of the previous beliefs and optimism had broken in face of the reality. Therefore, the degree pre-service teachers are prepared for teaching are reflected from the confidence and optimistic view held. The changes in confidence and optimism toward teaching before and after taking up teaching can be reviewed from the teachers’ perceptions. The information gathered would provide useful feedback to teacher educators and teacher education students to evaluate the adequacy and effectiveness of the program for professional development of teachers.

Another important component in teachers’ professional development is teachers’ conceptions about

teaching and learning. Researchers have suggested that teachers’ conceptions about teaching and learning are beliefs driven, and are related to teachers’ instructional decisions, teaching behaviour and actions in the classroom (Caldehead, 1996; Flores, 2001; Richardson, 1996). A teacher’s educational beliefs or conceptions may influence his/her judgement about what kind of knowledge is essential, the ways of teaching and learning and the methods of class management to be adopted. That is, teachers’ beliefs and hence their conceptions about teaching and learning can guide pedagogical decisions and practices (Ennis, Cothran, & Loftus, 1997; Wilson, Readence, & Konopak, 2002). Research has also suggested that teacher education students’ beliefs are well established by the time they begin a teacher education program and that these beliefs about teaching are formed during the apprenticeship of observation in their former days of schooling (Lortie, 1975). There are varied opinions and findings as regards whether the teachers’ beliefs and conceptions about teaching and learning can be altered by training and experiences gained in teacher education programs (e.g. Tillema, 1997). Therefore, examining teachers’ conceptions about teaching and learning (such as their views about pedagogy, the role of teacher and students, the relative importance of theory versus practice, the usefulness of teacher education program to their teaching, etc.) would provide valuable feedback to teacher educators and program designers on the effectiveness and impact of the teacher education program on pre- and in-service teachers’ professional development.

OBJECTIVES

The present study aims to examine the motives, conceptions and concerns of in-service teachers in the process of professional development. Based on the purpose of the study, several research questions were drawn.

Research Questions

1. What are the motives of in-service teachers in choosing teaching as a career?

2. What perceptions/conceptions are held by in-service teachers before and after taking up teaching?

3. What are their concerns about teaching?

4. Are there any significant differences in teachers’ motives to teach and concerns about teaching with respect to their demographic characteristics?

Method

A questionnaire was administered to 246 in-service teacher education students of a tertiary institute in Hong Kong. The questionnaire contained 80 items, to be rated on a five point Likert scale: from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Based on the theoretical concepts and research findings on teachers’ motives, concerns, perceptions/conceptions about teaching and learning as mentioned in the Related Literature section, items were written to measure these variables and grouped into four areas. Area 1 consisted of 21 items intended to measure the motives of the participants to take up teaching as a career. Areas 2 and 3 each consisted of 19 items, intended to examine the psychology of the participants before and after taking up teaching. The assessed psychology of the particpants included the confidence to teach, their perceptions/conceptions about teaching and learning, related to the constructivist and traditional views about teaching, pedagogy, teacher-pupils relationship and class management. Area 4 consisted of 21 items intended to examine the concerns in teaching, which targeted at students’ learning and development, the teaching tasks and the teachers themselves. Before completing the questionnaire, participants were asked to supply their demographic

characteristics including their gender, age, elective or subject, teaching experiences and level (primary or secondary) taught in school.

Participants

The participants were in-service teacher education students enrolled in the Two-year Part-time Postgraduate Diploma of Education (PGDE) and the Three-year Mixed Mode Bachelor of Education (MMBEd) program. There were 80 students (32.52%) from the PGDE program and 166 (67.48%) from the MMBEd program. Of those who had indicated their gender (N = 203), 64 were male (31.5 %) and 139 were female (68. 5%). The age ranged from 20 to 36 and above, mostly around 20-25 (38.5%) and 26-30 (34.6%). For teaching experiences, they ranged from less than 1 year (4.7%) to more than 20 years (6.8%), most of them around 1-5 years of teaching experiences (61.3%). There were 58 students teaching at primary and 186 at secondary level, with 2 teaching at post-secondary level.

Data Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis using Maximum Likelihood and Oblimin Rotation was applied to the rated response items (Areas 1 and 4) of the questionnaire to determine the number and nature of factors accounting for the motives to take up teaching as a career; and the focused concerns perceived by the in-service teachers. Psychometric properties (reliability Cronbach alphas) of the motives and concerns factors or subscales identified were then computed. Multivariate analysis (ANOVA) was also applied to investigate if there was any significant difference of the identified factors or s u b s c a l e s w i t h r e s p e c t t o t h e d e m og r a p h i c characteristics of the participants.

Results

1.

Motives to Teach

With eigen-value of 1 as the cut-off and scree-plot test, three factors were extracted accounting for an accumulative percentage of variance equal to 51.11%. The first factor accounts for a variance of 24.03%, the second factor 17.32% and the third one 9.76%.

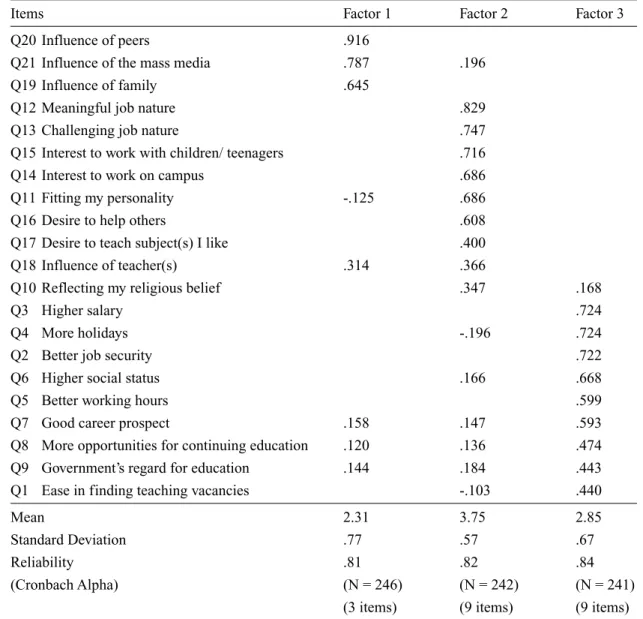

According to the nature of items, factor 1 was labeled “Influence from others”, factor 2 was labeled “Intrinsic/ Altruistic” and factor 3 was labeled “Extrinsic/Job condition”. The factor structure and the mean, standard deviation and reliability (Cronbach alpha) of the extracted factors are given in Table 1.

Table 1 Factor Structure, Mean, Standard Deviation and Reliability of the Motives in Choosing Teaching as a Career Pattern matrix (Maimum Likelihood and Oblimin Rotation)

ANOVA was applied to analyze the motives of in-service teachers to take up teaching with respect to their demographic variables. Significant difference was found at .05 level between programs of study, age and teaching experiences. For programs of study, significant difference was found in the second motive to teach, that is, “Intrinsic/Altruistic” motive (PGDE: mean = 3.64, SD = .52; MMBEd: mean = 3.80, SD = .58), (F (1, 240) = 4.34, p<.05; t (240) = -2.08, p<.05). For age groups, signif icant difference was found in the motive “Influence from others” and the difference was found between two age groups (20-25: mean = 2.49, SD = .73; 26-30: mean = 2.20, SD = .73), (F (3, 230) = 2.81, p<.05; t (169) = 2.59, p<.05). For teaching experience, signif icant difference was found in the motive “Influence from others” (F (5, 229) = 2.40, p <.05) and this was found between the following groups of teaching

experiences (1-5 years versus 6-10 years and 1-5 years versus 16-20 years). In the former case, (1-5 years: mean = 2.39, SD = .69; 6-10 years: mean = 2.05, SD = .75, t (181) = 2.67, p <.05); and in the latter case, (1-5 years: mean = 2.39, SD = .69; 16-20 years: mean = 1.82, SD = .69, t (153) = 2.65, p< .05). There was no significant difference in the motives to teach across gender, elective groups and levels taught.

2.

Perceptions/Conceptions before and after

taking up teaching

The perceptions/conceptions of in-service teachers before and after taking up teaching were analyzed in several domains, the frequency counts and percentages were given in Tables 2.1 and 2.2 respectively.

The results in Tables 2.1 and 2.2 show the confidence, optimism and commitment expressed by the in-service teachers under study, as well as their perceptions/ conceptions about class management, the relative importance of theory versus practice, the preferred ways of teaching and learning.

3. Concerns about Teaching

With eigen-value of 1 as the cut-off and scree-plot test, two factors accounting for an accumulative percentage of variance equals to 35.37%. The first factor accounts for a variance of 22.75%, and the second factor 12.62 %.

According to the nature of items, factor 1 was labeled “concerns with pupils” and factor 2 was labeled “concerns with self ”. The factor structure and the mean, standard deviation and reliability (Cronbach alpha) of the extracted factors are given in Table 3.

ANOVA was applied to examine if there was any significant difference in the concerns displayed by in-service teachers with respect to their demographic

variables. No significant difference was found in their concerns across programs of study, age, sex, elective groups, and levels taught.

DISCUSSION

Three factors were extracted from factor analysis of the item responses representing the sampled in-service teachers’ reasons to join the teaching profession. These three factors accounted for the motives of the in-service teachers to choose teaching as a career. The three motives were “Influence from others”, “Intrinsic/ Altruistic” and “Extrinsic/Job conditions”. In terms of the mean values of the three factors (see Table 1), the in-service teachers under study chose teaching as a career mostly due to the “Intrinsic/Altruistic” motive (mean = 3.75, SD = .57), next, the “Extrinsic/Job condition” (mean = 2.85, SD = .67) and last the “Influence from others” factor (mean = 2.31, SD = .77). That is, the in-service teachers joined the teaching profession mainly due to the fact that they liked to work with children and adolescents; they liked to help others and found the work meaningful and challenging, and suited their personality.

Material rewards such as salary, stability, holidays, and easy to find a job as contained in the “Extrinsic/Job condition” factor were not as important and determining as the “Intrinsic/Altruistic” factor in their choice of teaching as a career. “Influence from others” such as teachers, parents, peers and mass media, though influential, was not as decisive when compared with the previous two factors.

The result was similar to some of the findings reported in Western countries, but differed from that of the Young’s (1995) and Chan’s (1998) findings of pre-service teachers. The difference was probably due to t h e d i ff e r e n t c o m p o s i t i o n a n d d e m og r a p h i c characteristics of the samples in the studies including their educational qualification. In the present study, the teacher education students were in-service teachers of either university graduate status or non-graduate teachers holding Certificate of Education qualification

(qualified teacher status), the latter group continued to upgrade their qualification to university graduate status through part-time study. In Young’s (1995) and Chan’s (1998) study, the sample, however, consisted of pre-service non-graduate teacher education students enrolled in a certificate course. These students usually could not enter university although they got Advanced level subjects passes and hence they often consider teacher education as an alternate means of continuing further study and they might not be intrinsically or altruistically motivated in joining the teaching profession.

ANOVA study showed that a significant difference at .05 level was found in the motives to teach between programs of study, age and teaching experiences. Both PGDE and MMBEd students had mean value of “Intrinsic/Altruistic” motive above the mid-point of a five-point scale (PGDE, mean = 3.64, MMBEd, mean = 3.80 showing their relatively high interest to teach children and adolescents. The difference between the two groups was possibly due to their different background. The MMBEd students had destined to take up teaching after completing their Certificate course (a full-time two or three year sub-degree programs, designed to prepare non-graduate teachers for primary and junior secondary level teaching) some years before they got enrolled in the MMBEd program while the PGDE students could have other career options after university graduation besides teaching. Younger people might not have made up their mind at an early stage of choosing teaching as a career and they might have been more influenced by others such as their former teachers, parents, peers and media when they eventually joined the teaching profession. This might account for the differences in the motive “Influence from others” between age groups. Similar effect might be found due to different teaching experiences. Those with more

teaching experiences, usually also older ones were more matured, stable in thought and decision making, hence less influenced by others in joining teaching profession. This was reflected by the relatively lower mean score of the elder groups (mean = 2.20) and more experienced group (mean = 1.82) in the factor “Influence from others” in comparison with the younger (mean = 2.49) and less experienced group (mean = 2.39).

Referring to the perceptions/conceptions held by the sampled in-service teachers before taking up teaching, as shown in Table 2.1, the teachers tended to be confident about their class teaching (57.7% confident versus 16.2% lack of confidence) and optimistic (55.7% felt optimistic in the first teaching versus 13.0% not optimistic) when they took up the first teaching, the result was similar to the findings by Weinstein (1990) study of pre-service teachers that they tended to be optimistic at their beginning of teaching practice. Table 2.1 suggests that the sampled in-service teachers have their own ways of teaching based on their beliefs and conceptions rather than followed the practice of their former primary and secondary teachers (53.8% reported they did not follow the practice of their former teacher to teach their students and only 15.1% did) or existing teachers in the schools they taught (42.2% indicated they did not follow the practice of the existing teachers versus 19.1% who did). The result was somewhat different from the “apprenticeship of teaching” notion put forward by Lortie (1975) although some individuals of the sample did follow this practice. As for class management, the in-service teachers appeared to be in favour of rewards over punishment (50.4% ag reed versus 10.9% disagreed). A majority of the teachers (63.8%) did not want to be severe towards students. Many of them (67.9%) agreed that if they were dedicated to teach and care for students, they would be accepted by students. However, there were mixed views among the teachers about whether they should be friendly, lenient and

relaxed; the percentages of agreement and disagreement in these perspectives were quite close when class discipline and management were concerned (Table 2.1 refers).

For the conceptions about learning and teaching, more teachers in the sample believed the role of teacher is to facilitate students’ learning (51.6%) instead of direct teaching/transmission of knowledge (13.1%). 35.1% of the teachers did not agree that direct teaching is more effective than students’ construction of knowledge while 20.0% held opposite view. It was interesting to find that the majority (44.0%) remained neutral in this conception. That is, while some teachers were in favour of the constructivist conception of learning and teaching, others remained undecided or neutral towards the views. Further reflection of the varied teachers’ conceptions about teaching and learning was reflected from their responses towards the statement “students need not recite the subject knowledge the teachers taught”. The percentages of those who disagreed and agreed to this view were not widely different (33.4% versus 26.8%). Similarly, they won’t totally ignore the importance of educational theories in comparison with subject matter knowledge and many of them agreed that the program in the Institute helped their teaching.

For the perceptions/conceptions held by the in-service teachers after they took up teaching, it was delightful to find that their confidence and commitment to teach increased as shown in Table 2.2 (confidence increased: 68.3%, commitment increased: 66.3%). However, it is worthy to point out that student’s attitude and misbehavior in learning, as well as the performance and behaviour of existing teachers in the school did influence teachers’ commitment to teach. In other words, while the teachers were dedicated to teach, the school management side and the education authority should empower teacher’s commitment with support and provision of sound learning atmosphere.

Many of the teachers in the sample after taking up teaching still agreed to use rewards and approval in class management, they also tended to be caring and friendly towards students despite some agreed that being friendly and caring might not reduce the students’ misbehaviour and class discipline problems. While many teachers were in favour of the constructivist conceptions of teaching and learning, considerable number of them held the views that allowing students to construct knowledge by themselves were idealistic and impractical. This view exists both before and after taking up teaching. Possibly the influence of the assessment and examination system, the tight teaching schedule, the large students number in class, all these factors caused teachers to be cautious and not readily give up the didactic mode of teaching and allows students to construct their knowledge. Besides, many teachers in the sample agreed the program offered by the Institute helped their teaching; this reinforced the conception that the teachers enrolled in teacher education program not only for the sake of acquiring qualified teacher status and upgrade their qualification but also had the will to continue their professional development with further learning.

The result in Table 3 supports the hypothesis and findings of Fuller (1969) that two major concerns were detected within teachers, one “concern with pupils” and the other “concerns with self ”. Comparing the means of the two factors, factor 1 “concerns with pupils” has a higher mean score (4.06) than factor 2 “concerns with self ”. The finding is similar to previous research reports that pre-service and beginning teachers have greater self concerns than those expressed by the experienced in-service teachers and that in-in-service teachers’ task concerns are higher than their self concerns (e.g. Kazelskis & Reeves, 1987; Maxie, 1989). Two implications arise. First, it is a positive sign to find our teachers care and concern more with pupils than their

are placed on the top priority and what the teachers do mainly is for the good and well being of the students. The teachers in the sample might have been more conscious about their impact on the development of students, that is, many of them have reached the final stage of professional development proposed by Fuller (1969, 1974). As well, many of the teachers are committed, dedicated and work for the benefits of the students and they inclined to be student-centered. Second, viewed at a different angle, there might be troublesome factors related to students’ learning, e.g. students’ low or lack of motivation to learn, disruptive behaviour and class discipline problems. All these aroused teachers’ anxiety and concerns that “pupils’ cases” was put as priority concerns/issues. If that is the case, then the education authority, parents and teachers should work collaboratively to solve the problem and teacher education institutes should equip teachers with more knowledge and techniques to handle the problem cases and relieve their worry and concerns.

For “self concerns”, this included the language competency and information technology competence, the teaching technique, teaching schedule progress, use of media and which class to teach; some of these are concerns for survival, and some are task concerns. As the sample comprised teachers of different age and teaching experiences, it is no wonder why both types of concerns were found. Notice that with the recent educational reform and changes put forward by Education and Manpower Bureau (EMB), the language bench mark test and information technology competency requirement had caused much anxiety and concerns within teachers. Teachers were pressurized to handle such many requirements and reformation changes besides normal teaching and non-teaching duties within a short duration. This cannot be neglected as it has a strong psychological impact on teachers. Additional training and support are

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study identified three motives and two concerns of a sample of in-service teachers in Hong Kong. The three motives were: “Intrinsic/Altruistic”, “Extrinsic/Job condition” and “Influence from others”. Of the three motives, the in-service teachers under study were mostly influenced by the “Intrinsic/Altruistic” motive in joining the teaching profession. They were inclined to help children and adolescents in their development through teaching their interested subjects. They indicated that teaching was meaningful, challenging and fitting their personality or religious beliefs. Consequently, it is expected they care more about the well-being and learning of their students than extrinsic values attached to the job condition, such as salary, holidays, status, ..etc.

The “Intrinsic/Altruistic motives” would help the teachers remain in the teaching profession with persistence and enthusiasm and not to give up teaching readily. Such expectations were reinforced with the concerns expressed by the teachers under study, who demonstrated a higher proportion of “concern for pupils” than “concern with self ”. The phenomenon suggested the Hong Kong in-service teachers under study had progressed to a higher stage of professional development, according to the theoretical framework of Fuller (1969) and others (Buhendwa, 1996; Kazelskis & Reeves, 1987). However, the higher proportion of teachers’ concerns about “class discipline”, “the students’ learning motivation”, “intellectual, moral and value development of students” should not be neglected as it raised an alarming sign to the negative learning attitude and misbehaviour displayed by increasing number of students. The solving of these problems obviously requires cooperative effort of teachers, parents, community and the education authority.

The present study found that the Hong Kong in-service teachers under study were conf ident and committed to their teaching; their confidence and

commitment increased after they took up teaching. This is an encouraging finding. Nevertheless, teachers should not be overloaded as they have been facing with countless educational reform and requirement all the time, which might cause teachers exhausted, and eventually burnt out. The Hong Kong in-service teachers in the sample in general were self-improving, always tried to upgrade not only their education qualification but also the efficacy of their teaching work through attending teacher education program which they considered useful and functional in helping their teaching. The Hong Kong in-service teachers were generally inclined towards the constructivist conceptions about teaching and learning, agreeing to provide more opportunities for students to discuss and that the teacher’s role is a facilitator of students’ learning rather than transmitter of knowledge. Being exposed to both the Chinese and Western culture and philosophy, Hong Kong teachers had gradually changed to be more democratic and inclined to adopt the constructivist approach to teaching and learning. However, being pressurized by the tight teaching schedule and examination system, the Hong Kong teachers would not entirely give up didactic teaching and they still require students to memorize or recite what were taught in class. Recitation or memorization is not bad if considered as rehearsal to enhance memory in information processing of knowledge, a foundation for further learning and application. This accounts for a considerable number of teachers who agreed that students should recite or memorize what they were taught in class. In summary, the Hong Kong teachers under study were found to be confident, committed and caring for their students’ learning and development. They had a positive sense about teaching and learning. While they tended to conceive lear ning and teaching in a constructivist manner, they were also practical and realistic in practice in order to adjust to the present education and examination system.

References

Adams, R.D. (1982). Teacher Development: A Look at Changes in Teacher Perceptions and Behaviours Across Time.

Journal of Teacher Education, 33(4), 40-43.

Ballou, D. & Podgursky, M (1997). Teacher Pay and Teacher Quality. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Buhendwa, F.M. (1996, June). Stages of Concerns in Pre-service Teacher Development: Instrument Reliability and Validity

in a Small Private Liberal Arts College. Paper presented for the Conference of the National Ventere on Postsecondary

Learning at University park, PA. 50 p.

Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers: Beliefs and Knowledge. In D.C. Berliner, & R.C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of Educational

Psychology (pp. 709-725). New York: Macmillan.

Chan, K.W. (1998). The Role of Motives in the Professional Development of Student Teachers. Education Today, 48(1), 2-8.

Chan, K.W. (2002). The Development of Pre-service Teachers: Focus of Concerns and Perceived Factors of Effective Teaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education and Development, 5 (special issue 1), 17-40.

Education Commission (1992). Education Commission Report No. 5: The Teaching Profession. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Ennis, C.D., Cothran, D.J., & Loftus, S.J., (1997). The Influence of Teachers’ Educational Beliefs on Their Knowledge Organization. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 30 (2), 73-86.

Flores, B.B. (2001). Bilingual Education Teachers’ Beliefs and Their Relation to Self-reported Practices. Bilingual Research

Journal, 25(3), 275-299.

Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns for Teachers: A Developmental Conceptualization. American Educational Research Journal,

6(2), 207-226.

Fuller, F.F., Parsons, J.S., & Watkins, J.E. (1974, April). Concerns of Teachers: Research and Reconceptualization. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research association, Chicago, IL. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 091439).

Furlong, J., & Maynard, T. (1995). Mentoring Student Teachers: The Growth of Professional Knowledge. London: Routledge.

Heathcoat, L. H. (1997). Teacher’s Early Years: Context, Concerns, and Job Satisfaction. D.Ed. Dissertation, North Carolina State University.

Hutchinson, G., E, & Johnson, B. (1993/1994). Teaching as a Career: Examining High School Students’ Perspectives.

Action in Teacher Education, 15(Winter), 61-7.

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher Turnover, Teacher Shortages, and the Organization of Schools. Seattle: Center for the Study of Teacher and Policy. University of Washington.

Johnston, J., Mckeown, E., & McEwen, A. (1999). Primary Teaching as a Career Choice: the Views of Male and Female Sixth-form Students. Research Papers in Education, 14(2), 181-197.

Kazelskis, R., & Reeves, C.K. (1987). Concern Dimensions of Pre-service Teachers. Educational Research Quarterly, 11

(4), 45-52.

Kyriacou, C., & Coulthard, M. (2000). Undergraduates’ Views of Teaching as a Career Choice. Journal of Education for

Teaching, 26(2), 117-126.

Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Maxie, A.F. (1989, March). Student Teachers’ Conceptions and the Student Teaching Experience: Does Experience Make

a Difference ? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San

Francisco, CA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 308164).

Murnane, R. J. (Ed.) (1991). Who Will Teach? Policies That Matter. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. National Center for Education Statistics. (1992, Nov.). Teacher Attrition and Migration (Issue Brief No. NCES-IB-2-92).

Washington, D.C.: Author (ERIC Document No. ED 352356).

Newby, D., Smith, G., Newby, R., & Miller, D. (1995). The Relationship Between High School Students’ Perceptions of Teaching as a Career and Selected Background Characteristics: Implications for Attracting Students of Color to Teaching. Urban Review, 27(3), 235-249.

O’Connell, R. F. (1994). The First Year of Teaching: It’s not What They Expected. Teaching and Teacher Education.

10(2), 205-17.

O’Connor, J., & Taylor, H. P. (1992). Understanding Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Concerns to Improve Teacher Recruitment and Retention. Teacher Education Quarterly, 19(3), 19-28.

Reid, I., & Caudwell, J. (1997). Why Did Secondary PGCE Students Choose Teaching as a Career ? Research in Education,

58, 46-58.

Richardson, V. (1996). The Role of Attitudes and Beliefs in Learning to Teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.). Handbook of Research

on Teacher Education, (2nd ed., pp. 102-119). New York: Macmillan.

Smith, S. L. (1997). A Comparison of Concerns and Assistance Received for Concerns Perceived by First-year and

Second-year Teachers. D.Ed. Thesis, University of Houston.

Teacher Shortages Worst for Decades (2001, August, 28). BBC News Online. Retrieved September 4, 2001, from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/education/newsid_1512000/1512590.stm

Tillema, H. H. (1997). Promoting Conceptual Change in Learning to Teach. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education,

25(1), 7-16.

Weinstein, C.S. (1989). Teacher Education Students’ Preconceptions of Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 53-60.

Weinstein, C.S. (1990).Prospective Elementary Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching: Implications for Teacher Education.

Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(3), 279-290.

Wilson, E. K., Readence, J.E., & Konopak, B.C. (2002). Pre-service and In-service Secondary Social Studies Teachers’ Beliefs and Instructional Decisions about Learning with Text. Journal of Social Studies Research, 26(1), 12-22. Yong, C.S. (1995). Teacher Trainees’ Motives for Entering into a Teaching Career in Brunei Darussalam. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 11(3), 275-80.

Young, B. (1995). Career Plans and Work Perceptions of Pre-service Teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(3), 281-292.