INTRODUCTION

The Japanese eel Anguilla japonica is a catadromous fish that spawns in the open ocean west of the Mariana Islands, 14° N, 142 to 143° E (Tsukamoto 2006) and grows in freshwater (Tesch 2003). During a period of 4 to 6 mo, the larvae, leptocephali, drift with the North Equatorial and Kuroshio Currents to east Asia, meta-morphose into glass eels on the continental shelf, and become elvers in the estuary (Cheng & Tzeng 1996). The elvers then spend approximately 4 to 10 yr growing as yellow eels in rivers (Tzeng et al. 2000, Han et al. 2003a), before metamorphosing into silver eels and mi-grating back to the spawning ground to spawn and die.

In recent years, otolith growth patterns and chemical compositions have provided detailed chronologies of habitat use for individual eels (Campana 1999). Because otolith strontium:calcium (Sr:Ca) ratio levels are correlated with the ambient salinity, they are used

to trace the salinity life history of the eels (Tzeng et al. 1997, Campana 1999). The eel’s life history strategy is not only complicated but plastic; some of the American Anguilla rostrata, European A. anguilla and Japanese eels may skip the freshwater phase and grow up in brackish water and seawater until the silver eel stage (Tzeng et al. 1997, 1999, 2000, Tsukamoto et al. 1998, Jessop et al. 2004). The eel also has different migratory contingents and should be regarded as a facultatively catadromous fish (Tsukamoto & Arai 2001, Tzeng et al. 2002a, 2003, Jessop et al. 2004). Although the migra-tory behaviour of the eel is well documented, differ-ences in habitat preference between the sexes are still poorly understood.

The sex composition of wild anguillid eels in each habitat varies widely, ranging from almost all males to predominantly females (Matsui 1972, Oliveira 1999, Oliveira et al. 2001, Tzeng et al. 2002a, Tesch 2003, Han & Tzeng 2006). The uneven distributions of sexes

© Inter-Research 2007 · www.int-res.com *Corresponding author. Email: wnt@ntu.edu.tw

Sex-dependent habitat use by the Japanese eel

Anguilla japonica in Taiwan

Yu San Han, Wann Nian Tzeng*

Institute of Fisheries Science, College of Life Science, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 106, ROC

ABSTRACT: The Japanese eel Anguilla japonica is a catadromous fish, but it has recently been dis-covered that the use of freshwater habitat at the yellow eel stage is facultative. To determine if habi-tat use by Japanese eels differs between the sexes we examined the strontium:calcium (Sr:Ca) ratios in otoliths of 221 eels by electron probe micro-analyzer to reconstruct their environmental history. Eels were collected from the Kaoping River estuary of southwestern Taiwan from 1998 through 2005. The habitat use of yellow phase eels was divided into 3 types according to the life history pattern of the otolith Sr:Ca ratios: Type 1 (freshwater resident), Type 2 (brackish water resident with a fresh-water preference) and Type 3 (brackish fresh-water resident with a seafresh-water preference). Habitat use differed significantly between male and female silver stage eels. Females were classified predomi-nantly as Type 2 or 3 while males were classified predomipredomi-nantly as Type 1 or 2. Consequently, female yellow stage eels preferred an estuarine habitat while males preferred a freshwater habitat. In addi-tion, the mean otolith Sr:Ca ratios in the region 200 to 400 µm from the primordium (which corre-sponds to the period of sex differentiation) were higher in females than in males. This indicated that the sex differentiation of the eel might be related to habitat use, i.e. brackish water eels tended to dif-ferentiate as females and freshwater eels as males.

KEY WORDS: Japanese eel · Otolith Sr:Ca ratio · Sex-dependent habitat use · Sex differentiation

in habitats must result from either different habitat choices made by each sex or from considerable effects on sex differentiation by the habitat in which they grow. The sexual differentiation of the eel is labile and thought to be environmentally determined and to occur at the yellow eel stage around 15 to 35 cm (Mat-sui 1972, Colombo & Grandi 1996, Krueger & Oliveira 1999). Individual growth rate (Helfman et al. 1987, Holmgren & Mosegard 1996), population density (Par-sons et al. 1977, Krueger & Oliveira 1999, Tesch 2003, Han & Tzeng 2006), temperature (Holmgren 1996), lat-itude (Helfman et al. 1987) and river type (Sinha & Jones 1967, Oliveira et al. 2001) are possible extrinsic cues. In some studies the higher percentage of males found in estuarine habitat than in freshwater has led to the suggestion that higher salinity water might favour male development (Sinha & Jones 1967, Helfman et al. 1987, Tesch 2003). However, many studies observed the opposite distribution, with males predominant in freshwater and females predominant in brackish water (Sinha & Jones 1967, Holmgren 1996, Kotake et al. 2003, 2005). In estuarine habitats the changes in salin-ity are highly variable and eels can choose the pre-ferred salinity microhabitat (Han et al. 2003b). The migratory behavior of some eels between freshwater and seawater habitats further disturbs the possible effect of salinity on sex determination. Thus, the use of chronologies of salinity history recorded in the otoliths of individual eels as revealed by Sr:Ca ratios (Tzeng et al. 1997, Campana 1999) may enable an assessment of whether habitats with different salinity will affect eel sex determination.

This study aims to identify different strategies of habitat selection by Japanese eels of different sex by analyzing otolith Sr:Ca ratios and assess the potential effect of different habitat use by juvenile eels on their future sex determination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection. Wild Japanese eels Anguilla japonica were collected monthly with eel traps in the estuary of the Kaoping River in southwestern Taiwan (22° 40’ N, 120° 50’ E) during the period from 1998 to 2005 (Fig. 1). The eel pots were set at the bottom of the riverbank in the estuary where, influenced by both the freshwater and tide action, the salinity varied from 0 to 30 ‰. Total length (TL, ±1 mm) and body weight (BW, ± 0.1 g) of individual eels were measured. The sex and developmental stage of each eel were determined by visual inspection or by histological examination when possible (Han et al. 2003a).

Otolith preparation for Sr:Ca ratio analysis. A total of 221 Japanese eels, which were selected from

batches collecting in the late autumn and winter when most silver eels occurred, were used for otolith analy-sis. This included 39 silver males, 2 yellow males, 64 yellow females, 87 silver females, and 29 juveniles of unknown sex. Sagittal otoliths, the largest of the 3 pairs of otoliths in the inner ear, were used for Sr:Ca ratio analysis and age determination. The procedure for preparation of the otolith for Sr:Ca ratio analysis fol-lowed Tzeng et al. (1997). Briefly, otoliths were dried in the air, embedded in Epofix resin, ground and polished until the core was exposed. For electron probe micro-analysis the polished otoliths were coated with carbon under a high vacuum evaporator. Using an electron probe microanalyser (JEOL JXA-800M), strontium (Sr) and calcium (Ca) concentrations (wt%) in the otolith were measured from the primordium to the edge of otolith at intervals of 10 µm with an electron beam 5 µm in diameter. The accelerating voltage was set at 15 kV and probe current at 5 nA. The peak concentra-tion of Sr was counted for 90 s with background mea-surements for 20 s on each side. The peak concentra-tion of Ca was counted for 20 s and each background for 10 s. Strontianite (SrCO3, USNM-R10065) and

cal-cite (CaCO3, USNM-36321) from the Department of

Fig. 1. Anguilla japonica. Sampling location in the estuary of the Kaoping River in southwestern Taiwan. The inset

Mineral Sciences, National Museum of Natural His-tory, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, were used as the standards to calibrate the concentration of Sr and Ca in the eel otolith. After microchemistry analysis, the otolith was polished to remove the carbon layer, and etched for 1 to 2 min with 5% ethylene dia-mine tetra-acetate (EDTA, pH = 7.4) to reveal the an-nular marks for age determination (Tzeng et al. 1997). The annuli, metamorphosis and elver checks were determined using a transmitted light microscope.

Previous studies had identified divergent migratory contingents of Japanese eel for samples coming from upstream of rivers and lakes, estuary and marine habi-tats. For the freshwater type of the eel the Sr:Ca ratios in the otolith beyond 150 µm from primordium to the edge fluctuated between 0 and 4 ‰ (Tzeng et al. 2003). In contrast, the ratios in the otoliths of the brackish water type of the eel in the layer approximately 150 µm from primordium to the edge can be greater than 4 ‰ with a maximum of 10 ‰. Therefore, the Sr:Ca ratio of 4 ‰ was used as the boundary to discriminate freshwa-ter and brackish wafreshwa-ter habitats. Based on this the eel was classified into different migratory contingents.

Data analyses.Differences in frequency distribution of the wild Japanese eels among habitat contingents were tested for significance by the chi-square test of homogeneity using χ2 contingency table. Differences

in the mean age, TL and BW among eel groups of unknown sex, yellow and silver females and silver males were examined by 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison tests. The differ-ence of the mean otolith Sr:Ca ratios for each sex between 200 and 400 µm and beyond the elver check were measured by Student’s t-test for paired compar-isons.

RESULTS

Otolith Sr:Ca ratio patterns

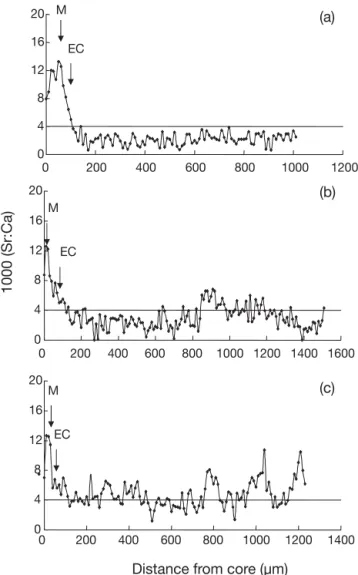

The Sr:Ca ratios in Japanese eel otoliths before the elver stage, approximately 0 to 150 µm from the pri-mordium, were similar among individuals, indicating that the migratory environmental history was similar among individuals during the marine leptocephalus stage (Fig. 2). However, otolith Sr:Ca ratios beyond the elver stage varied markedly and were classified into 3 types of migratory contingents (Fig. 2) described as follows.

Type 1 (freshwater resident): > 90% of Sr:Ca ratios in the otolith beyond the elver check fluctuated below 4 ‰, indicating that the eels after elver stage had been migrating to freshwater habitat to grow until metamor-phosis into the silver eel stage (Fig. 2a).

Type 2 (brackish water resident with freshwater preference): 50 to 90% of Sr:Ca ratios in the otolith beyond the elver check were lower than 4 ‰, indicat-ing that the eels after elver stage had been migratindicat-ing between freshwater and brackish water, but showed a freshwater preference (Fig. 2b).

Type 3 (brackish water resident with seawater pref-erence): > 50% of Sr:Ca ratios in the otolith beyond the elver check were higher than 4 ‰ indicating that the eels after elver stage had been migrating between freshwater and brackish water, but showed a brackish preference (Fig. 2c). M EC 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1000 (Sr:Ca) M EC M EC 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400

Distance from core (µm) (a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 2. Anguilla japonica. Temporal changes in the Sr:Ca ratios of otoliths from different migratory contingents col-lected from the estuary of the Kaoping River. (a) Type 1: water resident; (b) Type 2: brackish water resident with fresh-water preference; (c) Type 3: brackish fresh-water resident with seawater preference. M: metamorphosis from leptocephalus to glass eel; EC: elver check from glass eel to elver. Silver

Sex-dependent habitat use in the Kaoping River estuary

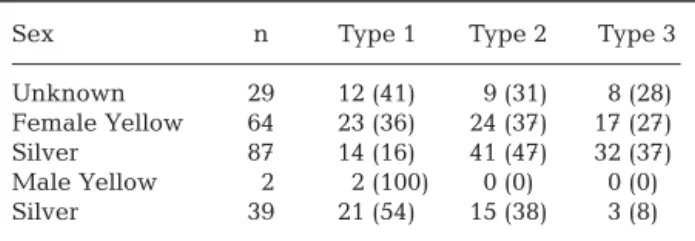

From 1998 through 2005, a total of 221 Japanese eels collected in the Kaoping River estuary were analysed (Table 1). More silver stage eels were chosen to trace their whole environmental life history. The mean age, TL and BW were largest in silver eel females and low-est in the silver males (age: F = 23.2, df = 3, p < 0.001; TL: F = 110.2, df = 3, p < 0.001; BW: F = 76.7, df = 3, p < 0.001) (Table 1). The distribution of the 3 types of life histories of the eels varied between sexes (Table 2). Sil-ver stage males and females differed significantly in habitat use (χ2 = 22.52, df = 2, p < 0.005) (Table 2).

There was no significant difference between females of yellow and silver stages (χ2 = 7.91, df = 2, 0.01 < p <

0.025) (Table 2). Male silver eels predominated in the Type 1 (54%) and Type 2 (38%) contingents and silver females were dominant in the Type 2 (47%) and 3 (37%) contingents (Table 2).

Habitat-related sex determination between sexes

Sex differentiation of the eels occurs during the juve-nile stage at around 15 to 35 cm for Japanese, American and European eels in temperate waters (Matsui 1972, Helfman et al. 1987, Kruger & Oliveira 1999). This cor-responded approximately to the region of eel otoliths 200 to 400 µm from the primordium, as evaluated by back-calculated growth histories from annual otolith in-crements (Tzeng et al. 2000). The mean Sr:Ca ratio of female Japanese eels was significantly higher (p = 0.001) than for males during the supposed eel sex-dif-ferentiated period (Table 3). Mean otolith Sr:Ca ratios beyond the elver check also differed between the sexes, with higher mean values occurring for females than for males (p < 0.001). The mean otolith Sr:Ca ratios between 200 and 400 µm and beyond the 150 µm from the primordium were not significant in both the male (p = 0.308) and female (p = 0.437).

DISCUSSION

Life history scans of otolith Sr:Ca ratios have vali-dated that yellow stage Japanese eels occupy habitats that include freshwater and brackish water with some eels migrating between the 2 habitats (Fig. 2). The diverse life history strategies of Japanese eels indi-cated that freshwater residence of eels during the growth phase is opportunistic, not obligatory (Tsuka-moto & Arai 2001, Kotake et al. 2003, 2005). The rivers in Taiwan, however, are mostly small without stable freshwater input and, thus, most eels may be com-pelled to grow in the estuary (Tzeng et al. 2002a). The catch experience of local fishermen indicates that Japanese eels are seldom caught in the middle and upper reaches of the Kaoping River and many weirs along the river may block the upstream migration of the eels. Thus, most of the Japanese eels are forced to concentrate in the estuary of Kaoping River (Han & Tzeng 2006). Consequently, most individual eels analysed in this study should come from the estuarine stock. The fluctuat-ing salinity in the Kaopfluctuat-ing River estu-ary (0 to 30 ‰), from almost freshwater up from the sandbar of the estuary to near seawater down from the bridge of the estuary (Fig. 1), provides diverse microhabitats for the eels to select. Because silver stage eels have almost finished their entire continental life Table 1. Anguilla japonica. Mean (± SD) age, total length (TL) and body weight

(BW) of eels used for otolith Sr:Ca ratio analysis and collected in the Kaoping River estuary during 1998 to 2005. Yellow males were excluded from the analy-sis due to the low sample size. A: silver male; B: yellow female; C: silver female;

D: unknown sex

Sex n Age (yr) TL (mm) BW (g)

Male Yellow 2 3.0 ± 0.0 35.9 ± 0.32 52.8 ± 2.7 Silver 39 5.8 ± 1.3 54.5 ± 7.2 246.8 ± 101.1 Female Yellow 64 4.8 ± 1.3 45.7 ± 8.8 146.9 ± 104.7 Silver 87 6.4 ± 1.1 62.2 ± 7.4 432.2 ± 191.6 Unknown Yellow 29 3.8 ± 0.7 34.7 ± 7.7 57.1 ± 44.6 Tukey HSD D < B < A < C D < B < A < C D < B < A < C test results

Table 2. Anguilla japonica. Number and percentage composi-tion (in parentheses) of life history types (%) between sexes. Type 1: freshwater resident; Type 2: brackish water resident with freshwater preference; Type 3: brackish water resident with seawater preference; number in the parentheses

indicat-ing percentage of each contindicat-ingent for each eel stage

Sex n Type 1 Type 2 Type 3

Unknown 29 12 (41) 9 (31) 8 (28) Female Yellow 64 23 (36) 24 (37) 17 (27) Silver 87 14 (16) 41 (47) 32 (37) Male Yellow 2 2 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) Silver 39 21 (54) 15 (38) 3 (8)

Table 3. Anguilla japonica. Comparison of mean ± SD Sr:Ca ratios (‰) (range) between sexes in otolith regions of 200 to 400 µm (the region corresponding to the period of sex differ-entiation of the eel) from the primordium and that from elver

check to the otolith edge (>150 µm)

Sex 200–400 µm >150 µm

Male 0.26 ± 0.11 (0.10–0.55) 0.27 ± 0.09 (0.16–0.54) Female 0.34 ± 0.14 (0.16 –0.59) 0.35 ± 0.08 (0.18–0.50)

stage, their otolith Sr:Ca ratios represent their whole environmental life history. Most (84%) silver females showed brackish water preference (Types 2 and 3, Table 2). In contrast, the majority (54%) of silver males preferred the freshwater habitat (Type 1, Table 2). A significant difference also existed between sexes for the mean Sr:Ca ratios. Beyond the elver stage, the mean otolith Sr:Ca ratio of female eels was higher than for males. Consequently, male and female Japanese eels showed different habitat preferences, with males preferring a freshwater habitat and females favouring a brackish water one.

The Sr:Ca ratios at the otolith edge of silver female Japanese eels, which recorded their latest salinity his-tory, showed a significant preference for seawater (Han et al. 2003b). Differences in sex ratio, on the other hand, were found between different growth habitats. For ex-ample, the proportion of male silver American eels was inversely related to the amount of lacustrine habitat in a Maine river system. Eels migrating from lacustrine habitats were predominately female whereas eels mi-grating from fluvial habitats were predominately male (Oliveira et al. 2001). Higher percentages of male Euro-pean eels have also been found in small Welsh streams than in large rivers (Sinha & Jones 1967). It is generally accepted that female and male anguillid eels have evolved different life history strategies, with male eels exhibiting a time-minimizing growth strategy by ma-turing as soon as possible at a smaller size, while fe-males maturating with a size-maximizing growth strat-egy so as to attain higher fecundity (Vøllestad & Jonsson 1986, Helfman et al. 1987, Tzeng et al. 2002b, Han & Tzeng 2006). Different habitat use by eels of each sex might reduce conspecific competition and, thus, have an adaptive advantage.

In addition to the salinity-related habitat preference differences between sexes, the sex determination of young juvenile stage Japanese eels may also have been affected by salinity. The mean Sr:Ca ratios dif-fered significantly between sexes, not only beyond the elver stage, but also during the time period in which eel sex determination occurred. This indicated that the habitat use not only differed between the sexes but the habitat itself also might affect eel sex determination, e.g. high salinity habitats promote female sex differen-tiation and freshwater habitats promote male sex dif-ferentiation. The environmental sex determination has been demonstrated in many species (Docker & Bea-mish 1994) and evolves when an environmental factor is more advantageous to one sex than to the other, as is the salinity factor in the case of the eel. However, many other environmental factors that might affect anguillid eel sex determination are also reported. Individual eels experiencing rapid growth in the juvenile stage before sex differentiation tend to develop as males, whereas

those that grow slowly initially are more likely to develop into females (Helfman et al. 1987, Holmgren & Mosegard 1996). Males tend to predominate at high environmental densities while females predominate at low density (Krueger & Oliveira 1999, Tesch 2003, Han & Tzeng 2006). High temperature conditions have also been proposed to favour development as males (Holm-gren 1996). One study showed that the proportion of female migratory silver American eels tends to increa-se with latitude (Helfman et al. 1987). However, the interrelated environmental factors that might be responsible for sex determination in eels make it diffi-cult to evaluate their relative contribution and domi-nance. Kotake et al. (2003, 2005) studied the migratory history of the Japanese eel in the Amakusa Islands and Mikawa Bay of Japan by otolith Sr:Ca ratios. They found a high percentage of females in seawater and brackish waters and more males in rivers. In the coastal areas of Japan feeding conditions are better and the population density is lower than in the streams. These factors are used to explain the habitat-dependent sex determination of the Japanese eel. In the Kaoping River of Taiwan, seawater eels are rare compared with the findings for eels in the Amakusa Islands and Mikawa Bay of Japan (Kotake et al. 2003, 2005). This may be due to the difference in habitats: marine habitats in the sampling sites of Japan, but estuarine habitats in Taiwan. The sex ratio of the Japanese eel in the Kaoping River estuary was strongly skewed towards females, which was believed to be due to the low-density effect (Han & Tzeng 2006). Even so, Japanese eels living in the estuary with diverse salinity habitats clearly show significant habi-tat-dependent sex determination. This infers that the sex of an eel is probably determined by multiple condi-tions instead of by solely one factor. Salinity, density and other environmental factors may all contribute to the sex determination of the eel.

Kotake et al. (2005) reported that after sex determi-nation more females may tend to move to marine or brackish water habitats, while males may remain in the freshwater until the spawning migration. In the present study, the percentage of freshwater (Type 1) females was slightly higher in the yellow stage than in the silver stage, while the percentage of brackish wa-ter (Types 2 and 3) females was slightly lower in the yellow stage than in the silver stage. However, no sig-nificant difference was found. In addition, mean otolith Sr:Ca ratios between 200 and 400 µm and beyond the elver check are similar for each sex, indicating that the sex-differentiated individuals may tend to stay in simi-lar habitats without showing a sex-dependent differ-ence on habitat shift.

In summary, Japanese eels of undetermined sex in the Kaoping River estuary tended to develop as

females in a brackish water habitat and as males in a freshwater habitat. Sexually differentiated individuals continued to show a sex-specific habitat preference. Phenotypic-dependent sex determination in Japanese eels may have evolved as an adaptation to a spatially heterogeneous habitat. The sex determination of the eel may be facultative and determined by multiple environmental factors, which vary among habitats. More studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of how extrinsic factors affect sex determination in eels and subsequent habitat selection.

Acknowledgements. This study was financially supported by the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC 94-2313-B-002-070) and the Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (94 AS-14.12-FA-F1(5)). The authors are grate-ful to Dr. Y. Iizuka of Academia Sinica, Taiwan for the elec-tron Probe microanalyser technique help and Mr. B. M. Jes-sop of Canada for reviewing a draft of the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

Campana SE (1999) Chemistry and composition of fish otoliths: pathways, mechanisms, and applications. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 188:263–297

Cheng PW, Tzeng WN (1996) Timing of metamorphosis and estuarine arrival across the dispersal range of the Japan-ese eel Anguilla japonica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 131:87–96 Colombo G, Grandi G (1996) Histological study of the

devel-opment and sex differentiation of the gonad in the Euro-pean eel. J Fish Biol 48:493–512

Docker MF, Beamish FWH (1994) Age, growth, and sex ratio among populations of least brook lamprey, Lampetra aepyptera, larvae: an argument for environmental sex determination. Environ Biol Fishes 41:191–205

Han YS, Tzeng WN (2006) Sex ratio as a means of resource assessment for the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica: a case study in the Kaoping River of Taiwan. Zool Stud 45: 255–263

Han YS, Liao IC, Huang YS, He JT, Chang CW, Tzeng WN (2003a) Synchronous changes of morphology and gonadal development of silvering Japanese eelAnguilla japonica. Aquaculture 219:783–796

Han YS, Yu JYL, Liao IC, Tzeng WN (2003b) Salinity prefer-ence of silvering Japanese eel Anguilla japonica: evidence from pituitary prolactin mRNA levels and otolith stron-tium:calcium ratios. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 259:253–261 Helfman GS, Facey DE, Stanton HL, Bozeman EL (1987)

Reproductive ecology of the American eel. Am Fish Soc Symp 1:42–56

Holmgren K (1996) Effect of water temperature and growth variation on the sex ratio of experimentally reared eels. Ecol Freshw Fish 5:203–212

Holmgren K, Mosegaard H (1996) Implications of individual growth status on the future sex of the European eel. J Fish Biol 49:910–925

Jessop BM, Shiao JC, Iizuka Y, Tzeng WN (2004) Variation in the annual growth, by sex and migration history, of silver

American eels Anguilla rostrata. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 272: 231–244

Kotake A, Arai T, Ozawa T, Nojima S, Miller MJ, Tsukamoto K (2003) Variation in migratory history of Japanese eels, Anguilla japonica, collected in coastal waters of the Amakusa Islands, Japan, inferred from otolith Sr/Ca ratios. PSZN I: Mar Ecol 142:849–854

Kotake A, Okamura A, Yamada Y, Utoh T, Arai T, Miller MJ, Oka HP, Tsukamoto K (2005) Seasonal variation in the migratory history of the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica in Mikawa Bay, Japan. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 293:213–221 Krueger W, Oliveira K (1999) Evidence for environmental sex

determination in the American eel, Anguilla rostrata. Env-iron Biol Fishes 55:381–389

Matsui I (1972) Unagigaku: eel biology. sha Kosei-Kaku, Tokyo

Oliveira K (1999) Life history characteristics and strategies of the American eel, Anguilla rostrata. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 56:795–802

Oliveira K, McCleave JD, Wippelhauser GS (2001) Regional variation and the effect of lake:river area on sex distribu-tion of American eels. J Fish Biol 58:943–952

Parsons J, Vickers KU, Warden Y (1977) Relationship be-tween elver recruitment and changes in the sex ratio of silver eels Anguilla anguilla L. migrating from Lough Neagh, Northern Ireland. J Fish Biol 10:211–229

Sinha VRP, Jones JW (1967) On the age and growth of the freshwater eel (Anguilla anguilla). J Zool 153:119–137 Tesch FW (2003) The eel. Blackwell Science, Oxford Tsukamoto K (2006) Spawning of eels near a seamount: tiny

transparent larvae of the Japanese eel collected in the open ocean reveal a strategic spawning site. Nature 493:929 Tsukamoto K, Arai T (2001) Facultative catadromy of the eel

Anguilla japonica between freshwater and seawater habi-tats. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 220:265–276

Tsukamoto K, Nak I, Tesch WV (1998) Do all freshwater eels migrate? Nature 396:635–636

Tzeng WN, Severin KP, Wickström H (1997) Use of otolith microchemistry to investigate the environmental history of European eel Anguilla anguilla. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 149: 73–81

Tzeng WN, Severin KP, Wickström H, Wang CH (1999) Stron-tium bands in relation to age marks in otoliths of European

eel Anguilla anguilla. Zool Stud 28:452–457

Tzeng WN, Lin HR, Wang CH, Xu SN (2000) Differences in size and growth rates of male and female migrating Japa-nese eels in Pearl River, China. J Fish Biol 57:1245–1253 Tzeng WN, Shiao JC, Iizuka Y (2002a) Use of otolith Sr:Ca ratios to study the riverine migratory behaviors of Japan-ese eel Anguila japonica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 245:213–221 Tzeng WN, Han YS, He JT (2002b) The sex ratios and growth strategies of wild and captive Japanese eels Anguilla japonica. In: Small B, MacKinlay D (eds) Developments in understanding fish growth. Symp Proc Int Congr Biol Fish, Vancouver, Canada, p 25–42

Tzeng WN, Iizuka Y, Shiao JC, Yamada Y, Oka H (2003) Iden-tification and growth rates comparison of divergent migra-tory contingents of Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica). Aquaculture 216:77–86

Vøllestad LA, Jonsson B, (1986) Life-history characteristics of the European eel Anguilla anguilla in the Imsa River, Nor-way. Trans Am Fish Soc 115:864–871

Editorial responsibility: Otto Kinne (Editor-in-Chief), Oldendorf/Luhe, Germany

Submitted: July 4, 2006; Accepted: October 16, 2006 Proofs received from author(s): April 20, 2007