行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

有憂鬱傾向與外向偏差問題之國、高中生自我認同發展與心

理健康之間的關係

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC93-2413-H-002-011- 執行期間: 93 年 08 月 01 日至 94 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立臺灣大學心理學系暨研究所 計畫主持人: 雷庚玲 計畫參與人員: 吳英璋(協同主持人)陳坤虎(博士班研究生) 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 94 年 10 月 31 日

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

█ 成 果 報 告

□期中進度報告

有憂鬱傾向與外向偏差問題之國、高中生

自我認同發展與心理健康之間的關係

計畫類別:█ 個別型計畫

□ 整合型計畫

計畫編號:NSC 93-2413-H-002-011

執行期間:九十三年八月一日 至

九十四年七月三十一日

計畫主持人:雷庚玲

共同主持人:

計畫參與人員:吳英璋(協同主持人)陳坤虎(博士班研究生)

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):█精簡報告

□完整報告

處理方式:除產學合作研究計畫、提升產業技術及人才培育研究計畫、列

管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢

執行單位:台灣大學心理系

中

華

民

國

九十四

年

十

月

三十一

日

台灣國、高中生自我認同發展與憂鬱傾向之間的關係

Erik Erikson 的心理社會發展理論以「自我認同」為青少年期最重要的發展要務。其中又

特別強調認同的連續性與同一性(亦即:「認同確定感」)。Chen, Lay, 和 Wu (2003a)根據 Cheek

(1989)對於認同需求(亦即:「認同重要感」)的實徵測量方法與對認同面向的區分,而設計 出對個人、社會、與形象認同之「認同重要性」與「認同確定性」之測量,並發現在青少年 早、中、晚三個不同階段,青少年所注重的認同面向各有消長。Erikson 提出認同概念的初始 目的,乃冀望於能將認同概念用以解釋心理病理的發展。本研究團隊亦承襲 Erikson 之認同理 論的初始目的,欲藉「認同重要性」與「認同確定性」的理論與測量,一方面探討青少年之 認同特性與心理病理指標間的關係,一方面做為後續輔導工作的媒介。本研究並欲檢驗「認 同落差」之概念。從一般的通俗想法來看,「認同重要性」與「認同確定性」愈高,則應會有 較正向的心理健康。但本研究認為,當青少年的「認同重要性」與「認同確定性」之落差太 大時,反而可能使高認同重要性變成一危險因子。本研究共對台北縣市兩所學校之國一生 1397 人與四所高中的高一生 1971 人做全年級有關認同重要性、認同確定性,正向與負向心理健康 指標等之普測,並以迴歸分析,檢視「認同重要性」、「認同確定性」與「認同落差」對憂鬱 及各項心理病理指標的貢獻。本研究發現在分別排除「認同重要性」或「認同確定性」對於 憂鬱的影響後,青少年的憂鬱傾向的確與「認同落差」有負向關係,但這項發現卻不如在大 學生的研究中顯著,這項結果或許與青少年特定發展趨勢有關。本計畫並已經將各校(共六 校)的大樣本施測結果回饋予各校輔導室。並在下一年度的研究中,將「認同重要性高、確 定性低,對青少年心理發展反而可能有負向影響」的假說,實際用於輔導計畫中。本研究雖 亦收集到「外向偏差」及其他心理病理行為的普測資料,但由於結案報告篇幅所限及部份分 析結果與理論推演之爭議仍多,故暫不呈現。 關鍵詞:自我認同重要性、自我認同確定性、個人認同、社會認同、形象認同、認同發展、 青少年、認同落差、青少年心理健康

Self-Identity and Depression of

Junior High and High School Students in Taiwan

Abstract

Erik Erikson postulated that identity formation is the main developmental task during

adolescence. The current study is to examine how three features of self-identity, namely, identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy, are related to adolescent mental health. In the Early Adolescence Group (N = 1397), the junior high school students designated as the

Non-Depressed Group (N = 1238) demonstrated higher identity firmness and lower identity discrepancy than those designated as the Depressed Group (N = 152). Three multiple regression analyses indicated that aspects of identity discrepancy were slightly better predictors for depressive symptom than were aspects of identity importance or identity firmness. Findings of the Early Adolescence Group were then replicated in the Middle Adolescence group (N = 1971). Those high school students designated as the Non-Depressed Group (N = 1771) demonstrated higher identity firmness and lower identity discrepancy than those designated as the Depressed Group (N = 198). However, findings from the Middle Adolescence Group indicated that identity discrepancy was not a better predictor than identity firmness on depressive symptom measured by CES-D. In conclusion, the present study yielded that identity firmness and discrepancy are better predictors for depressive symptoms than identity importance. However, identity discrepancy did not seem to be a more powerful predictor than identity firmness as shown in the college sample. Specific

developmental trend during adolescence is discussed to explain the disparity of age differences.

Key words: Identity Firmness, Identity Importance, Personal Identity, Social Identity, Image Identity, Adolescence, Identity Discrepancy, Adolescent Mental Health.

Self-Identity and Depression of Junior High and High School Students in Taiwan: A Normative Approach

Adolescence is usually regarded as a transitional stage between dependent childhood and independent adulthood. Adolescence also is often viewed as a stage with heightened risk for future development (Adams, Gullotta, & Markstrom-Adams, 1994). Previous studies have suggested that adolescence is a particularly vulnerable period in terms of psychological adjustment (Adams, Bennion, Openshaw, & Bingham, 1990; Irwin, 1987; Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1988). Erik Erikson (1953, 1968) not only postulated that identity formation is the main

developmental task during adolescence but also believed that the quality of identity formation plays a role in developmental psychopathology. Recent studies also found that identity firmness and the discrepancy between identity importance and identity firmness are valid predictors of mental health indexed by various psychological symptoms among college students in Taiwan (Chen, Lay, Wu, 2003a, b; Chen, Lay, Wu, & Yao, 2005b, Chen, Lay, Soong, & Wu, 2005c). To validate the theoretical and empirical findings in Chen et al (2005b), the main goal of the current study is to downward extend the findings to the stages of early and middle adolescence. Specifically, the present study attempted to investigate the predictability of self-identity (i.e., identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy) on depressed symptom among junior high and high school adolescents.

Self-identity and Mental Health

According to the Eriksonian identity theory, a more confirmed sense of identity is more likely to lead to positive mental health (Erikson & Erikson, 1950; Jahoda, 1958) and/or optimal psychological functioning (Waterman, 1992). Specifically, Erikson (1968) emphasized that the feeling of self-continuity and sameness in one’svalues, beliefs, and goals promotes positive psychological growth. The Eriksonian approach in self-identity suffered from lack of quantifiable data. Cheek and his colleague later used questionnaires to assess the needs for defining the sense of self; yet this assessment did not catch the ideas of “continuity”and “sameness”that were postulated in Erikson’s identity theory.

Deriving from Cheek’s(1989)research,Chen,Lay, & Wu (2005a) developed measurements for“identity importance” and “identity firmness”centered on aspectsofpersonal,social,and image identity. The concept of identity importance is adopted from Cheek and his colleagues (Cheek & Briggs, 1982) that describes the individual needs in defining oneself. The

“Questionnaire of Identity Importance”(1st, 2nd, & 3rdeditions) (QII-I, II, & III) has preserved some items used in Cheek’s original assessment. Meanwhile, identity firmness is an integration of Erikson’s (1953) idea of “self-continuity”and “sameness”and Waterman’s (1984) conception of “clear delineation of self-definition”that represents individuals’“certainty”of self-identity. Specifically, identity firmness is defined as having a clearly delineated self-definition comprised

of those goals, values, abilities and beliefs to which the person is unequivocally committed. The self-definition, in turn, helps individuals to experience their daily life and encounter social demands. Although each individual may inevitably live in different temporal-spatial contexts, he/she still can have a sense of personal continuity and sameness that gives him/her a direction,

purpose, and meaning in life (Chen el al., 2005a). To further operationalize the construct of identity-firmness, Chen et al. created the“Questionnaire of Identity Firmness”(1stedition) (QIF-I) and asked subjects to answer questions regarding their feeling of firmness (i.e., whether and to what extent they are certain about a series of particular aspects of their lives) with regard to goals, values, and beliefs. QIF-I consists of three subscales, namely personal, social, and image

identities. By comparing among the aspects of personal, social, and image identity of junior high, high school, and college students over “identity importance”and “identity firmness,”Chen et al. found differential orientations of identity aspects among adolescents of different ages.

Specifically, younger adolescents are more concerned with “image identity”than their older counterparts. Meanwhile, the sense of continuity and sameness of older adolescents are stronger than that of their younger counterparts in all three aspects of identity firmness.

In addition to the concepts of identity importance and identity firmness, Chen et al. (2005b) adopts theEriksonian conceptof“balance between two oppositenotions”and proposed a third concept of “identitydiscrepancy,”which is defined empirically as the disparity between the standardized score of identity firmness and that of identity importance. For the concept of “identity importance”being a personal desire to fulfill an ideal-self in each aspect of identity development, and the “identity firmness”asthe individuals’assessment of the degree of certainty of self-continuity and sameness, “identity discrepancy”reflects the incongruence between the desire to fulfill a particular aspect of identity need and the current evaluation of the certainty of the same identity aspect.

Three studies have investigated the relations between the three identity indices (i.e., identity importance, identity firmness, identity discrepancy) and mental health. Chen et al. (2003b) found that college students in the High Identity Firmness group were generally at a lower risk for mental health problems. In the same study, individuals in the Low Identity Firmness group were found to be more likely to suffer from symptoms related to anxiety and depression (measured by SCL-90R). In a second study, Chen et al. (2003a) indicated that adolescents with higher scores on identity firmnessdemonstrated higher“self-esteem,”“positiveself-efficacy”and “subjective well-being”and lower“negative self-efficacy”than those with lower scores on identity firmness. These two studies implied that identity firmness is a good predictor for positive mental health and may help individuals toward positive personal growth. Additionally, Chen et al. (2005b)

demonstrated that identity discrepancy predicted psychological symptoms even better than did identity firmness in nine of the ten subscales of SCL-90R (e.g., depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, obsessive-compulsive). The results of the same study also indicated that identity importance tended to be positively correlated with psychological symptoms (e.g., Interpersonal Sensitivity) in the neurosis group, but negatively correlated with psychological symptoms in the healthy-control group; statistical analyses indicated the magnitude of correlation between identity importance and psychological symptoms was significantly different between the neurosis and the healthy-control group. For the healthy-control individuals, the more one cares about his identity needs the less likely he is going to have psychological symptoms. On the contrary, for the individuals in the neurosis group, the higher score in the measure of identity importance predicts a

stronger tendency of psychological symptoms.

The goals and analytical strategies of the present study

The present study attempts to replicate the findings of Chen et al. (2005b) with younger adolescents. That is, this study tests the relations between the three features of self-identity and depression during the periods of early and middle adolescence. Specifically, junior-high and high school students with different degrees of risk for depressed symptom are identified according to the results of mental health screening tests conducted in 6 schools located in the Metropolitan Taipei area. Portney and Watkins (2000) reported that the most general evidence supporting construct validity can be obtained by using the “known groups method”to distinguish individuals who are known to have the proposed trait and those who do not. Therefore, by comparing between the “non-depressed group”and the “depressed group”on the three identity features (identity importance, identity firmness, identity discrepancy), the present study intends to investigate whether the

constellation of these three identity features within an essentially normal non-depressed group differs from the pattern demonstrated in a high-risk group. The identity characteristics that only occur in the high-risk group may be indicative of psychological maladjustment.

Besides the analyses of group differences, multiple regression analyses of the three aspects of identity (i.e., personal, social, and image identity) are implemented to predict the depression index. By comparing the results of multiple regression analyses using identity importance, identity

firmness, or identity discrepancy as the predictor variable, the present study intends to demonstrate whether identity discrepancy is a more effective predictor to depression than identity importance and identity firmness. Another set of regression analyses will also be implemented after removing the subjects who are both low in identity importance and identity firmness. According to the logical derivation and the results stated in Chen et al. (2005b) that used college students as subjects, it is anticipated that the predictability of identity discrepancy will increase considerably with this partial data set.

There is a widely accepted rule-of-thumb in regression analysis, which states that one can never include a variable in the analysis whose scores are completely dependent on the scores of another variable(s) included in the analysis. In the present study, identity discrepancy equals to the standardized z score of identity importance minuses the standardized z score of identity firmness. Therefore, a skepticism can easily emerge in putting the three identity indices altogether in one regression analysis. However, the present regression analysis is designed exactly for partialing out the effect from the variance that overlapped with that of identity discrepancy. Moreover, the three variables are all designated as predictor variables; no plausible causal conclusion will be derived among the three identity indices.

Moreover, the present study also attempts to explore the role of identity importance on

depression. Therefore, following the analytic strategies in Chen et al. (2005b), the present study will calculate the simple correlations between the degree of identity importance and depressed score within each group.

The Early Adolescence group: Junior High School Students (7thgrade)

Subjects. A total of 1397 7thgrade students from two different schools in Taipei participated in this study. Among them, 744 students (53.2% male and 46.8% female, Mean age = 13.16) were from a junior high school located in Wan-Hwa District in Taipei and 653 students (49% male and 51% female, Mean age = 13.01) were from another junior high school located in Da-An District in Taipei.

Measures

Questionnaire of Identity Importance, 1stedition (QII-III). Items of QII-I are revised and translated into Chinese from Cheek’s (1989) “Aspects of Identity Questionnaire”(AIQ), which evaluates the needs for defining the sense of self, namely, identity importance. The third edition of QII-III derived from Chen et al. (2005a) were administered in this study. On a Likert’s scale, ranging from 1 to 5 (not important to extremely important), subjects indicated the extent to which each item is important in defining their own identity characteristics. QII-III contains a total of 30 items, including 10 items of personal identity (e.g., “my dreams and imagination”), 10 items of social identity (e.g., “my popularity with other people”), and 10 items of image identity (e.g., “my academic performance”).

Questionnaire of Identity Firmness, 3rdedition (QIF-III). The QIF-III derived from Chen et al. (2005a) assesses the sense of identity firmness. QIF-III applies a form of two-stage questions. Each subject first responds to a yes-no question on whether he/she is like the description of the items (e.g., “I can’t control my future directions”versus “I can control my future directions”). Then, subjects continue to rate on how certain they are to the statement checked in the first stage (range from 1 to 4). QIF-III contains a total of 30 items, including 10 items in each of the personal, social, and image identity subscale.

Scores of Identity Discrepancy (ID). Each identity discrepancy score is calculated by subtracting the standardized z score of QIF-III from that of QII-III.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D was developed by Radloff (Radloff, 1977) and has been widely used in identifying adult depression in both clinical (Weissman et al., 1977) and community (Roberts & Vernon, 1983) settings. The CES-D consists of 20 items with a four-point rating scale ranging from “0”(new or few) to “3”(usually). The Chinese version of CES-D was originally translated by two psychiatrists and found to be applicable among adolescents (Yang, Soong, Kuo, Chang, Chen, 2004).

Results and Discussion

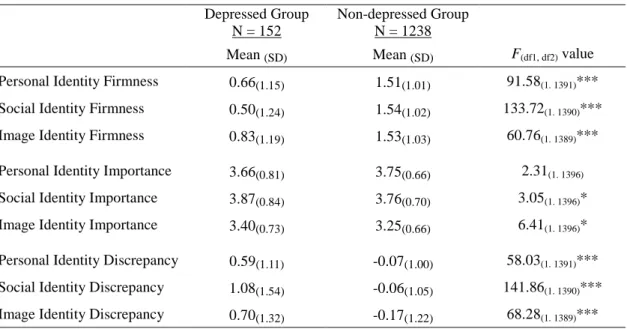

Among the 1397 7thgrade adolescents participating in the early-adolescence group, 152 subjects were assigned to the depressed group and 1238 subjects to the non-depressed group based on their CES-D scores. Because there was no report about the optimal cutoff point for the CES-D among adolescents in Taiwan before, we followed Garrison et al. (1991) by adopting the top 10% students as screening positive for depression in the present study. Three separate one-way ANOVA’s using the three aspects of identity firmness as the dependent variables yielded significant main effects of group difference in personal, social, and image identity. Three separate one-way ANOVA’s using the three aspects of identity importance as the dependent variables yielded significant main effects of group difference in social and image, but not for personal identity. Another three separate

ANOVA’s using the three aspects of identity discrepancy as the dependent variable also yielded significant main effects of group difference for personal, social, and image identity. Table 1 lists the mean and SD for each identity aspect of each group. The results of group differences in identity firmness and identity discrepancy are similar with the results found in Chen et al. (2005) that among college students scores of identity firmness in the pathological group were significantly lower than the healthy-control group, while scores of identity discrepancy significantly higher.

Table 1: Group Comparisons on Aspects of Identity Firmness, Importance, and Discrepancy in the Early adolescence

Group

Depressed Group N = 152

Non-depressed Group N = 1238

Mean(SD) Mean(SD) F(df1, df2)value

Personal Identity Firmness 0.66(1.15) 1.51(1.01) 91.58(1. 1391)***

Social Identity Firmness 0.50(1.24) 1.54(1.02) 133.72(1. 1390)***

Image Identity Firmness 0.83(1.19) 1.53(1.03) 60.76(1. 1389)***

Personal Identity Importance 3.66(0.81) 3.75(0.66) 2.31(1. 1396)

Social Identity Importance 3.87(0.84) 3.76(0.70) 3.05(1. 1396)*

Image Identity Importance 3.40(0.73) 3.25(0.66) 6.41(1. 1396)*

Personal Identity Discrepancy 0.59(1.11) -0.07(1.00) 58.03(1. 1391)***

Social Identity Discrepancy 1.08(1.54) -0.06(1.05) 141.86(1. 1390)***

Image Identity Discrepancy 0.70(1.32) -0.17(1.22) 68.28(1. 1389)***

***p < .01, **p < .01, *p < .05

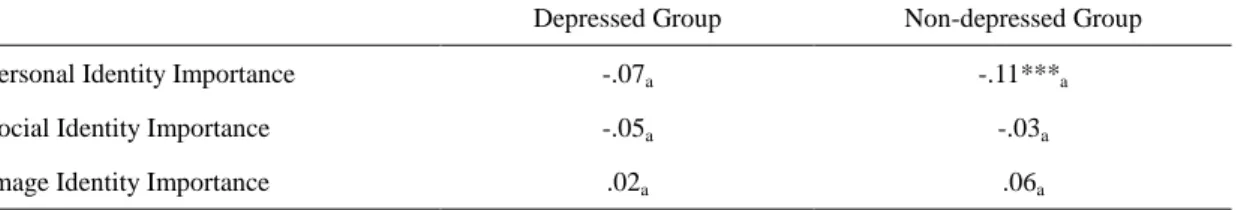

To compare the predictability of each feature of identity (i.e., importance, firmness, discrepancy) on depressed symptom, multiple regression analyses were conducted on depressed symptom using the personal, social, and image identity aspect of identity importance, firmness, and discrepancy as predictor variables. The results indicated that the three aspects of identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy significantly predict depressed symptom respectively. Table 2 indicates that identity discrepancy is not a better predictor of depressed symptom than identity firmness (explained variance: 20% vs. 22%). In another set of regression analyses (see the fourth to sixth column in Table 2) that has removed the subjects whose scores of identity importance and identity firmness were both lower than the means in any one identity aspect, the explained variance of identity discrepancy in predicting depressed symptom did increase considerably (20% up to 28%). Accordingly, identity discrepancy revealed to be a slightly better predictor for depressed symptom than identity firmness (explained variance: 24% vs. 28%).

Table 2: Explained Variance in Multiple Regression Predicting Depression from Identity Importance, Identity Firmness,

and Identity Discrepancy

(N=1380) (N=695,deleting LL) Predictive Variables Identity

Importance Identity Firmness Identity Discrepancy Identity Importance Identity Firmness Identity Discrepancy Depression .03*** .22*** .20*** .09*** .24*** .28***

*** p < .01 **p < .01 *p < .05

Next, the study calculated the simple correlations between the degree of identity importance and depressed score within each of the two groups. Personal identity importance was found to have a significant negative correlation of -.11 (p < .001) with the depressed score in the non-depressed group (see Table 3). However, group differences of correlation were not found significant after z transformation between identity importance and the depressed score in the three aspects of identity.

Table 3: Simple Correlation between Identity Importance and Depressed Symptom of Each Aspect of Identity in the

Depressed versus the Non-depressed Group

Depressed Group Non-depressed Group

Personal Identity Importance -.07a -.11***a

Social Identity Importance -.05a -.03a

Image Identity Importance .02a .06a

Correlations with different subscripts differ significantly at p < .10.

***p < .001 (two-tailed)

The Middle Adolescence group: High School Students (10thgrade)

Method

Subjects. A total of 1971 10thgrade students from four different high schools in Taipei participated in this study. Among them, 416 female students (Mean age = 15.75) were from a major female high school located in the Taipei city, 541 male students (Mean age = 15.83) were from a major male high school located in the Taipei city. Another 231 students (49.2% male and 50.8% female, Mean age = 15.73) were from a community high school located in the Taipei city, and 783 students (51.9% male and 48.1% female, Mean age = 15.95) were from another

mixed-gender major high school located in the Taipei county.

Measures

Like the measurements used for the early adolescence group, the booklet of questionnaires contains QII-III, QIF-III, and CES-D.

Results and Discussion

Among the 1971 adolescents participating in the middle adolescence group, 198 subjects were assigned to the depressed group and 1771 subjects to the non-depressed group based on their CES-D scores. Three separate one-way ANOVA’s using the three aspects (i.e., personal, social, and image) of identity firmness as the dependent variables yielded significant main effects of group difference in personal, social, and image identity. Three separate one-way ANOVA’s using the three aspects of identity importance as the dependent variables yielded a significant main effect of group difference in social identity, but not for personal and image identity. Another three separate ANOVA’s using the three aspects of identity discrepancy as the dependent variable yielded

significant main effects of group difference for personal, social, and image identity. Table 4 lists the mean and SD for each identity aspect of each group. The results of group differences in identity firmness and identity discrepancy are similar with the results found in Chen et al. (2005) that among college students scores of identity firmness in the pathological group were significantly lower than the healthy-control group, while scores of identity discrepancy significantly higher.

Table 4: Group Comparisons on Aspects of Identity Firmness, Importance, and Discrepancy in the Middle adolescence Group Depressed Group N = 198 Non-depressed Group N = 1771

Mean(SD) Mean(SD) F(df1, df2)value

Personal Identity Firmness 0.59(1.02) 1.41(1.04) 110.59(1. 1968)***

Social Identity Firmness 0.90(1.15) 1.68(0.95) 112.86(1. 1967)***

Image Identity Firmness 0.45(0.98) 1.15(0.98) 90.10(1. 1967)***

Personal Identity Importance 3.98(0.65) 3.94(0.59) 0.70(1. 1969)

Social Identity Importance 3.99(0.76) 3.87(0.62) 5.97(1. 1969)*

Image Identity Importance 2.98(0.78) 2.90(0.64) 2.67(1. 1969)

Personal Identity Discrepancy 0.74(1.19) -0.07(1.05) 104.32(1. 1968)***

Social Identity Discrepancy 0.85(1.45) -0.09(1.14) 111.52(1. 1967)***

Image Identity Discrepancy 0.73(1.52) -0.08(1.33) 64.21(1. 1967)***

***p < .01, **p < .01, *p < .05

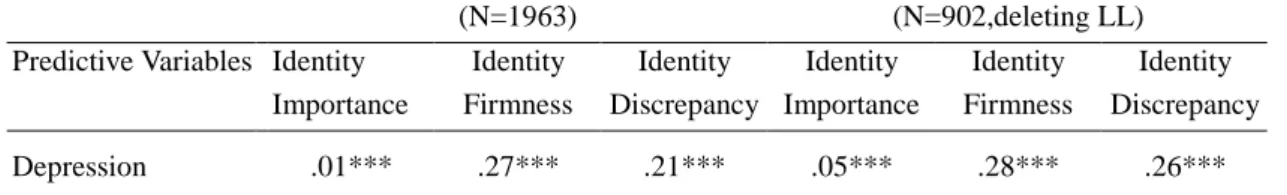

As in the early adolescence group, to compare the predictability of each feature of identity (i.e., importance, firmness, discrepancy) toward depressed symptom, multiple regression analyses on the depressed symptom were conducted using the personal, social and image identity aspect of identity importance, firmness, and discrepancy as predictor variables. The results indicated that the three aspects of identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy significantly predict depressed symptom respectively. Table 4 indicates that identity discrepancy is a not better predictor of depressed symptom than identity firmness (explained variance: 21% vs. 27%). In another set of regression analyses (see the fourth to sixth column in Table 5) that has removed the subjects whose scores of identity importance and identity firmness were both lower than the means in any one identity aspect, the explained variance of identity discrepancy in predicting depressed symptom did increase considerably (21% up to 26%). However, identity discrepancy did not reveal to be a better predictor for depressed symptom than identity firmness (explained variance: 26% vs. 28%). This result is different from Chen et al. (2005b), which indicated that identity discrepancy has a higher prediction power than identity firmness in most of the psychological symptoms assessed by SCL-90R, including depressiveness.

Table 5: Explained Variance in Multiple Regression Predicting Depression from Identity Importance, Identity Firmness,

and Identity Discrepancy

(N=1963) (N=902,deleting LL) Predictive Variables Identity

Importance Identity Firmness Identity Discrepancy Identity Importance Identity Firmness Identity Discrepancy Depression .01*** .27*** .21*** .05*** .28*** .26***

Note. LL = Low identity importance and Low identity firmness in any aspect of identity (Chen et al., 2005b)

*** p < .01 **p < .01 *p < .05

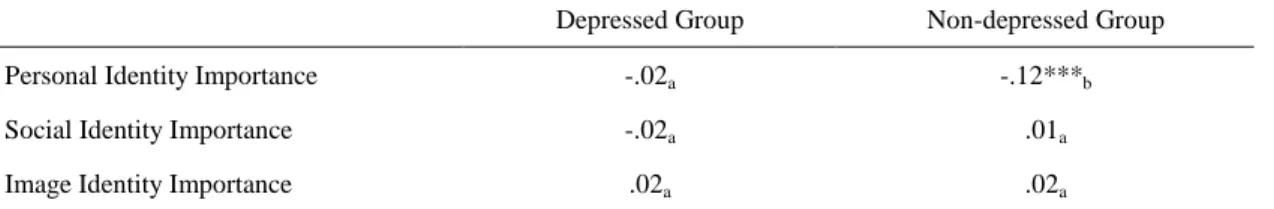

Again, the study calculated the simple correlations between the degree of identity importance and depressed score within each of the two groups. Personal identity importance was found to

have a significant negative correlation of -.12 (p < .001) with the depressed score in the

non-depressed group (see Table 6). Besides, group differences of correlation (p < .10) were found marginally significant after z transformation between identity importance and the CES-D score in the aspect of personal identity. That is, in the non-depressed group, individuals that receive higher scores in the personal identity importance subscale were less likely to be depressive. This trend coincides with the findings in college students (Chen et al., 2005b).

Table 6: Simple Correlation between Identity Importance and Depressed Symptom of Each Aspect of Identity in the

Depressed versus the Non-depressed Group

Depressed Group Non-depressed Group

Personal Identity Importance -.02a -.12***b

Social Identity Importance -.02a .01a

Image Identity Importance .02a .02a

Correlations with different subscripts differ significantly at p < .10.

***p < .001 (two-tailed)

General Discussion

The goal of this study is to replicate the empirical findings of Chen et al. (2005b) in a younger population of adolescents. Chen et al. (2005b) suggested that the identity firmness of college students may serve as a protective factor, identity discrepancy as a risk factor, and identity

importance as a moderating factor for healthy development. The present study and the findings in Chen et al. (2005b) indicated that throughout the different stages during adolescence, students with depressive tendency are significantly lower in identity firmness and higher in identity discrepancy compared to other students. Although the present and previous studies both did not indicate the mechanism of the group differences, the theoretical bases of identity firmness directs us to interpret the results as feelings of sameness and continuity in personal, social, and image aspects being necessary for healthy psychological development even from the first year of junior high school. The present study also revealed that depressive junior high and high school students tend to have higher scores in social and image identity importance. This finding is contrary to results in Chen et al. (2005b), which did not find group difference in identity importance. However, Chen et al. (2005a) did indicate that compared to college students, junior high and high school students have higher needs in using social and image terms for defining themselves. The present results thus may indicate that although it is normal for students in early and middle adolescence to have higher concern in social and image issues, overemphasis in social and/or image identity may be signs of maladjustment at least for internalizing problems. Alternatively, the group sizes for the depressed and non-depressed group in this study were quite uneven. Future studies need to adjust the sample size more carefully in replicating the current finding.

This study also found identity firmness and discrepancy are better predictors for depressive symptoms than identity importance. However, identity discrepancy did not seem to be a more powerful predictor than identity firmness as shown in the college sample. The next question would be whether it is necessary to create a variable of identity discrepancy in addition to the

existing two indices of identity importance and identity firmness. We tend to suggest that the concept of identity discrepancy is still useful for therapeutic purpose. Subjects are more likely to become aware of their own need and perspective in terms of personal, social, and image identity issues while the concept of discrepancy is introduced to them. The currently ongoing project of identity intervention in our laboratory will soon be able to verify or tease out this possibility.

In both age groups, the negative correlation between personal identity importance and

depression are significant in the non-depressed group but not in the depressed group. This trend is similar to findings from college students just that Chen et al. (2005b) not only found significant between-group difference in the magnitude of correlations but also indicated the valence of correlations reversed. The developmental differences of the patterns of correlation between

identity importance and psychopathology in the healthy-control and the pathological groups suggest that during the years of adolescence, identity importance gradually become more powerful toward moderating the effect of self-identity on depression.

Reference

Adams, G. R., Bennion, L. D., Openshaw, D, K., & Bingham, C. R. (1990). Windows of vulnerability: Identifying critical age, gender, and racial differences predictive of risk for violent deaths in childhood and adolescence, Journal of Primary Prevention, 10, 223-240. Adams, G. R., Gullotta, T. P., & Markstrom-Adams, C. (1994). Adolescent life experiences. Pacific

Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing company.

Cheek, J. M., & Briggs, S. R. (1982). Self-consciousness and aspects of identity. Journal of

Research in Personality, 16, 401-408.

Cheek, J. M. (1989). Identity orientations and self-interpretation. In D. M. Buss & N. Canter (Eds.),

Personality Psychology: Recent Trends and Emerging Directions (pp. 275-285). New York:

Springer-Verlag.

Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., & Wu, Y. C. (2005a). The development differences of identity content and exploration among adolescents of different stages. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 47,249-268. Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., Wu, Y. C., Yao, G. (2005b). Adolescent mental health and self-identity: The

function of identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy. Paperr presented at

the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., Soong, W, T., & Wu, Y. C. (2005c). The positive identity intervention

program leads to positive mental health in Chinese college students. Paper presented at the

Fourth International Positive Psychology Summit, Washington, DC.

Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., & Wu, Y. C. (2003a). Sense of identity firmness and positive mental health. Paper presented at the Second International Positive Psychology Summit, Washington, DC. Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., & Wu, Y. C. (2003b). Sense of identity firmness and emotional disorder.

Paper presented at the 3rd Congress of Asian Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions (ASCAPAP), Taipei, ROC.

Erikson, E. H. (1950/1953). Childhood and Society. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. Erikson, E. H. (1968/1994). Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. Erikson, J. M., & Erikson, E. H. (1950). Growth and crises of the “healthy personality.”In M. J .E.

Senn (Ed.), Symposium on the healthy personality (prepared for the White House Conference, 1950) (pp. 91-146). New York: Josiah Macy, Jr., Foundation.

Irwin, C. E. (1987). Adolescent social behavior and health. In W. Damon (Ed.), New Directions for

Child Development (Vol. 37, pp. 1-12). San Francisco: Jossy-Bass.

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., & Bachman, J. G. (1988, January 13). University of Michigan national news conference, Washington, DC.

Waterman. A. S. (1984). The Psychology of Individualism. New York: Praeger.

Waterman, A. S. (1992). Identity as an aspect of optimal psychological functioning. In G.R. Adams, T. P. Gullotta, & R. Montemayor (Eds.). Identity formation during adolescence, Vol.4: