國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

以框架理論為本之漢語情緒動詞詞彙語意分類研究

A Frame-based Lexical Semantic Categorization of

Mandarin Emotion Verbs

研究生:洪詩楣

指導教授:劉美君教授

以框架理論為本之漢語情緒動詞詞彙語意分類研究

A Frame-based Lexical Semantic Categorization of

Mandarin Emotion Verbs

研 究 生:洪詩楣

Student: Shih-mei Hong

指導教授:劉美君

Advisor: Mei-chun Liu

國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics College of Humanity and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master of Arts

June 2009

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

以框架理論為本之漢語情緒動詞詞彙語意分類研究

學生:洪詩楣 指導教授:劉美君

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班 摘 要

本研究以Fillmore和Atkins (1992)所提出的框架語意理論(Frame semantics)及 Liu 和Chiang (2008)提出的「中文動詞語意網之架構」為本,探討漢語中的情緒 動詞並進行分類。過去的學者從許多不同的角度分析情緒動詞 (例如Levin 1993, Tsai et al 1996, Chang et al 2000, Liu 2002, Lai 2004, and Berkeley FrameNet

Project),皆對情緒動詞的研究奠下了基礎。然而,過去的研究多只著重在數個 或小部份的情緒動詞,因此未能盡可能全面廣泛地呈現情緒動詞語意及語法上 的表現。此外,對於情緒動詞事件中的主語角色,過去研究大多只提到情緒感 知者(Experiencer)及刺激物(Stimulus)這兩種,然而Liu (2009)在研究中,經情緒 動詞語意、語法及句式特質提出第三種主要的主語角色: 情緒引動者(Affecter)。

1. Experiencer-oriented (Experiencer as subject) a. Transitive:我欣賞/羨慕/討厭他。 b. Intransitive: 我很害怕/高興/沮喪。 2. Stimulus-oriented (Stimulus as subject)

a. Intransitive – an attributive property: 這本書很恐怖/枯燥/有趣。 b. Transitive – an affective impact: 這本書很吸引/感動/激勵我。 3. Affecter-oriented (Affecter as subje ct)

他惹火/激怒了我。 ‘He infuriates/irritates me. ’

採用Liu (2009)三個主要參與角色的看法,本研究以中研院現代漢語平衡語料 庫為主要語料來源,觀察並考量情緒動詞的參與者角色、語法表現、事件結構、 共現特徵及語意訊息等因素,對漢語情緒動詞進行更深入的語法和語義研究,並 依Liu (2009)所建構認知動詞的概念基模,對漢語情緒動詞進一步做全面階層性的 分類。在分類上,本研究著重語法及語意上的互動,將漢語情緒動詞分類至由上 至下最多四層不同層次的框架中。這四個層次分別為「主框架」、「首要框架」、 「基本框架」以及「微框架」(Liu and Chiang 2008)。值得注意的是,這些框架有 著共同的概念基模。此外,同一階層的框架間雖然相 互差異,但每一個次框架都 共同繼承上一個母框架的語意及 語法句式特質。在此研究之中,漢語情緒動詞所 建立的語意框架結構乃由「情緒主框架」以及承繼於其的四個首要框架、九個基 本框架和多個微框架所組成。如下圖所示:

經由上述的分類之後,漢語情緒動詞的特性得以清楚展現,例如情緒事件構成的 面向、框架與框架間的階層性與關聯性、每個框架語意及語法上的差異以及 情緒 近義詞彙的區分等等。 簡言之,本研究主要觀察漢語情緒動詞在實際語料中所呈現的語意、語法特 點,以情緒動詞共有的概念基模,對漢語情緒動詞做進一步全面的分類 ,企盼能 為漢語情緒動詞的研究提供另一完整清楚的解釋與分析 。

A Frame-based Lexical Semantic Categorization of

Mandarin Emotion Verbs

Student: Shih-mei Hong

Advisor: Dr. Mei-chun Liu

Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

Adopting Frame Semantics proposed by Fillmore and Atkins (1992) and the Framework of Mandarin VerbNet by Liu and Chiang (2008), this study aims to explore Mandarin emotion verbs and classify the verbs into a hierarchical structure. A great number of studies have been investigated the behavior of emotion verbs from different perspectives (e.g. Levin 1993, Tsai et al 1996, Chang et al 2000, Liu 2002, Lai 2004, and Berkeley FrameNet Project ). However, most of the previous studies only looked at a small portion or part of the whole field of emotion verbs. Additionally, previous researches only mentioned Experiencer and Stimulus as the two main or frequently subject roles of emotion verbs. However, Liu (2009) explored the lexicalization patterns of Mandarin verbs of emotion and proposed a third type of subject: Affecter.

1. Experiencer-oriented (Experiencer as subject) a. Transitive:我欣賞/羨慕/討厭他。

wo xinshang/xianmu/taoyan ta

‘I admire/envy/dislike him. ’ b. Intransitive: 我很害怕/高興/沮喪。

wo hen haipa/gaoxing/jusang

‘I am very frightened/pleased/depressed .’ 2. Stimulus-oriented (Stimulus as subject)

a. Intransitive – an attributive property: 這本書很恐怖/枯燥/有趣。

‘The book is frightening/boring/ interesting.’

b. Transitive – an affective impact: 這本書很吸引/感動/激勵我。

zhe ben shu hen xiyin/gandong/jili wo

‘The book attracts/touches/encourages me .’ 3. Affecter-oriented (Affecter as subject)

他惹火/激怒了我。

ta rehuo/jinu le wo

‘He infuriates/irritates me.’

This study, adopting Liu’s (2009) three-way distinction proposal, aims to explain and interpret the specific and heterogeneous properties in syntax and semantic of Mandarin emotion verbs and provide a systematical categorization based on the syntax-to-semantics correlations of Mandarin emotion verbs by applying a frame-based and corpus-based analysis. The emotion verbs are categorized into four different layers of frames. They are, from top to down, Archiframe, Primary Frame, Basic Frame, and Micro-frame (Liu and Chiang 2008). Though the frames show diversities, they all share a same conceptual schema postulated with a set of core frame elements. Besides, all children or lower frames inherit the semantic and syntactic properties of the father or upper frame. The hierarchical frame structure of Mandarin emotion verbs in this study includes one Emotion archiframe, four primary frames, nine basic frames, and several micro-frames. The structure is illustrated as below:

The categorization displays some characteristics of Mandarin Emotion verbs, such as perspectives on viewing emotional events, the interrelationship among the frames, and the distinctions of near-synonym sets of verbs.

Briefly speaking, this study tries to categorize Mandarin Emotion verbs by the conceptual schema and the syntactic and semantic properties s hown through corpus observation and attempts to provide a complete and well -organized explanation and analysis.

致謝 時間彷彿仍停留在入學的那一刻 ,怎知三年一晃眼就過去了 ,我也順利地完成 了碩士論文。攻讀碩士學位的這三年,著實讓我成長了不少!除了知識層面的獲取之 外,更令人驚訝的是我在處事及能力上的成長 。這一切都得謝謝我的指導老師 —劉 美君教授。謝謝老師當初邀請我參與國科會研究計畫 ,讓懵懂無知的我在一次次的 會議中真正了解做研究的方法;謝謝老師嚴格的要求,讓我在處理事情時思緒更為 周全;謝謝老師深而切的鞭策,讓我在一次次的淚水中面對自我的缺點,勇敢成長! 也因為老師的鼓勵與支持 ,我得以有機會和老師一起出國發表會議論文 ,甚至完成 了從來不敢奢望的留學夢 。因此即便跟隨老師的日子中淚水多過於笑容 ,我仍非常 樂意、慶幸自己有機會走過。說再多句謝謝我想都不足以表達我對老師的感謝 ,但 我仍要不免俗的說聲謝謝老師,因為您,所以我得以蛻變成長!也謝謝連金發老師及 鄭縈老師,謝謝兩位老師在仔細審閱完論文後給予學生的意見與建議 ,您們的意見 使我的論文更加完善。三位老師的用心與付出 ,學生由衷感謝。此外,我也要就讀 期間所有教導過我的老師們(林若望、劉辰生、許慧娟、潘荷仙、Paul Portner 等教 授)誠摯地說聲謝謝,謝謝老師們為我開啟了語言學的大門 ,讓我看到語言學中各 領域的奧妙與可愛之處,也為我的論文打下了根基 。 除了老師們之外,我也要謝謝辛苦的系辨助理 :雅玲、旅櫻、曉玲及怡吟。謝謝 妳們在學術甚至是生活上的 種種協助。尤其是曉玲還曾在我跌傷時 ,犧性自己寶貴 的下班時間帶我去看醫生 。 在學習、研究的過程中,總有許多一起奮鬥的同伴 。謝謝老是不吝於幫我解惑 的佳音學姊、璦羽學姊、子玲學姊以及Peter學長;謝謝一同在304努力的同學及學弟 妹們:雯靜、Fenny、佩瑜、若梅、蔓婷、彥甫以及柏宏,謝謝你們總在我累到不行 時貼心地為我加油打氣 。尤其要謝謝與我同甘共苦的舜佳(喵),那些個兩人一同深 夜還留在304打拼的日子,以及那在Boulder四個多月的時光,是我永遠都不會忘記 的回憶; 謝謝我那群可愛到不行的同學:惠瑜、鈴宓、佳霖、佳芬、縉雯、Joanna還 有美玲,因為有妳們,研究所生活才不枯橾;謝謝我可愛的室友們:青樺、佳貞、 佳君還有秀,謝謝妳們不時的加油關心 ,然後總是及時來個寢聚讓我消消課業上的 壓力;也謝謝我身邊所有的朋友 :複合式的朋友麗筠、其實很貼心的汶珀、體貼溫柔 的柏蒼、帶我「趴趴造」紓解壓力的沛宏、一貫溫柔貼心支持鼓勵我的 涵宇,以及 總是持續關心我的怡碩 、阿龍及肥仔。 最後,我更要謝謝我最摯愛可愛的家人 ,謝謝爸爸媽媽無怨無求的付出 ,即便 再如何辛苦也要咬著牙讓我完成學業與夢想 ;謝謝姊姊與弟弟的支持與陪伴 ,讓我 有傾訴的對象。謝謝我最親愛的家人,在我最疲憊沮喪的時候,你們永遠是我心中 的避風港,也是最大的支柱與動力 。 僅將這本碩士論文獻給我最愛最愛的爸媽 及外婆,還有在天上的外公及爺 爺。

Table of Contents

Chinese Abstract ... ... ... ... i

English Abstract ... ... ... ... ii

Acknowlegement... ... ... ...vi

Table of Contents ... ... ... ... viii

Tables and Figures……… ………..xi

Chapter 1 Introduction... ... ... 1

1.1 The Background ... ... ... 1

1.2 The Issue: Emotion Verbs ... ... ...1

1.3 Scope and Goal ... ... ... 4

1.4 Organization of the Thesis ... ... ...6

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... ... ... 7

2.1 Terms Used in the Previous Studies ... ... 7

2.2 Typological Studies of Emotion Verbs ... ... 8

2.2.1 Alternation-based Approach ………..……….… 8 2.2.2 Frame-based Approach ………..……… 10 2.2.3 Corpus-based Approach ……….………12 2.2.3.1 Tsai et al (1996) ... ... ...12 2.2.3.2 Chang et al (2000) ... ... .15 2.2.3.3 Liu (2002) ... ... ... 17 2.2.3.4 Lai (2004) ... ... ... 21 2.3 Summary ... ... ... ....28

3.1 Database ... ... ... ...29

3.2 Theoretical Framework ... ... ... 30

3.2.1 Frame Semantics………... ...30

3.2.2 Framework of Mandarin VerbNet ……… ………. 31

3.3 The Methodology... ... ... 32 Chapter 4 Findings ... ... ... ...34 4.1 Event Types ... ... ... 34 4.2 Transitivity ... ... ... .42 4.3 Alternations ... ... ... 46 4.3.1 Stative-Causative alternation………..….………46 4.3.2 Active-Passive alternation………..………48 4.4 Subject Roles ... ... ... 49 4.5 Participant Roles ... ... ... 54

4.5.1 The Causee of Emotion Events/States: Experiencer, Affectee …..….…55

4.5.2 The Cause of Emotion Events/States: Stimulus, Reason, Content, Prior Act.………..………..……… 56

4.5.3 The Causer of Emotion Events/States: Affecter ………...….……59

4.5.4 The Target of Emotion Events/States: Target_entity, Target_situat ion, Target_act, Target_empathy, Target_possible situation, Beneficiary ..59

4.5.5 The Response of Emotion Events/States: Result ………..….…..63

4.5.6 Other Attributes or Non -core roles of Event Events: Topic, Expressor, Act, Degree……… ..………...…….….….….….….…63

4.6 Syntactic Patterns of the Verbs with the Participant Roles ... 65

Chapter 5 Analysis ... ... ... ...76

5.1 Conceptual Schema of Emotion Archiframe ... ... 76

5.2 Taxonomy of the Frames ... ... ...79

5.2.1 Layer 1: Archiframe (Emo tion frame)……….….….…….…. 80

5.2.2 Layer 2: Primary Frame ……… ….….….….….….82

5.2.2.1 Exp-Oriented Frame ... ... 83

5.2.2.2 Exp-Oriented with Target Frame... ...85

5.2.2.3 Stimulus-Oriented Frame ... ... 87

5.2.2.4 Affect-Oriented Frame ... ... 88

5.2.2.5 Brief Summary ... ... ...90

5.2.3 Layer 3: Basic Frame……… ….….…….….…….91

5.2.3.1 The Basic Frames under Exp -Oriented Frame ... 97

5.2.3.1.1 Happy-Sad Frame ... ... 98

5.2.3.1.2 Regret-Sorry Frame... ... 101

5.2.3.2 The Basic Frames under Exp -Oriented with Target Frame ...103

5.2.3.2.1 Content-Contented Frame ... ... 104

5.2.3.2.2 Love-Hate Frame ... ... 106

5.2.3.2.3 Envy-Pity Frame ... ... 108

5.2.3.2.4 Worry-Fear Frame... ... 110

5.2.3.3 The Basic Frames under Stimulus -Oriented Frame ... 112

5.2.3.3.1 Stimulus-Attributive Frame ... ... 113

5.2.3.4 The Basic Frames under Affect -Oriented Frame ... 114

5.2.3.4.1 Attract-Comfort Frame ... ... 115

5.2.3.4.2 Bother-Irritate Frame ... ... 116

5.2.4.1 The Micro-frames under Regret-Sorry Frame ... 122

5.2.4.2 The Micro-frames under Love-Hate Frame ... 123

5.2.4.3 The Micro-frames under Stimulus-Attributive Frame ... 125

5.2.4.4 The Micro-frames under Bother-Irritate Frame ... 128

5.2.4.5 The Micro-frames under Emotion Archiframe……….129

5.3 Overview of the Frames ... ... ... 129

5.4 Summary ... ... ... ..134

Chpater 6 Conclusion……… .………..135

References... ... ... ... 137

Tables and Figures

Lists of Tables

Table 1: 12 Children Frames of the Emotions Frame and Lexical Units in Each Child

Frame ... ... ... ... 11

Table 2: The Syntactic Distribution of Gaoxing and Kuaile ... ... 12

Table 3: The Contrastive Distribution of Type A and Type B Verbs. ... 16

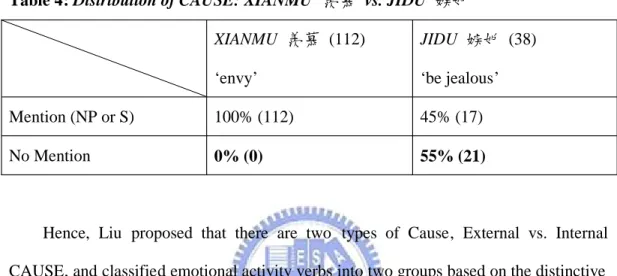

Table 4: Distribution of CAUSE: XIANMU 羨慕 vs. JIDU 嫉妒 ... 20

Table 5: Interaction between Criteria and Psych Predicates ... ... 21

Table 6: Three Types of Psychological Predicates in Terms of CAUSE ... 22

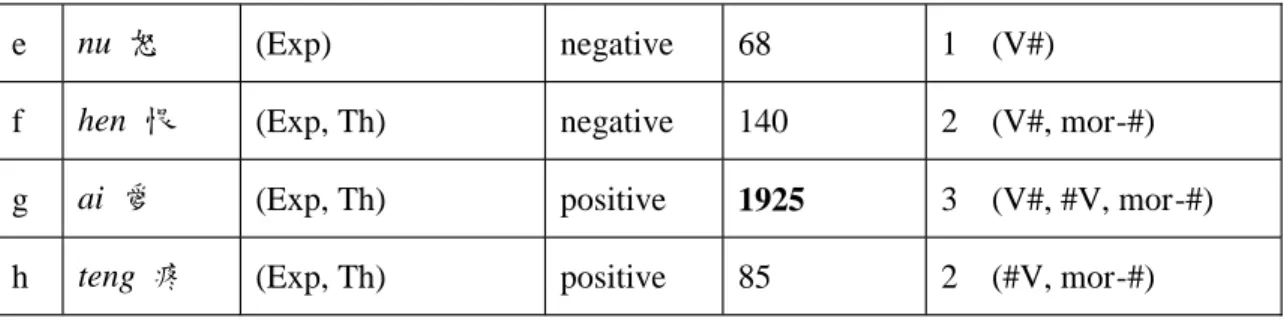

Table 7: Adverbials for Agentivity ... ... ... 25

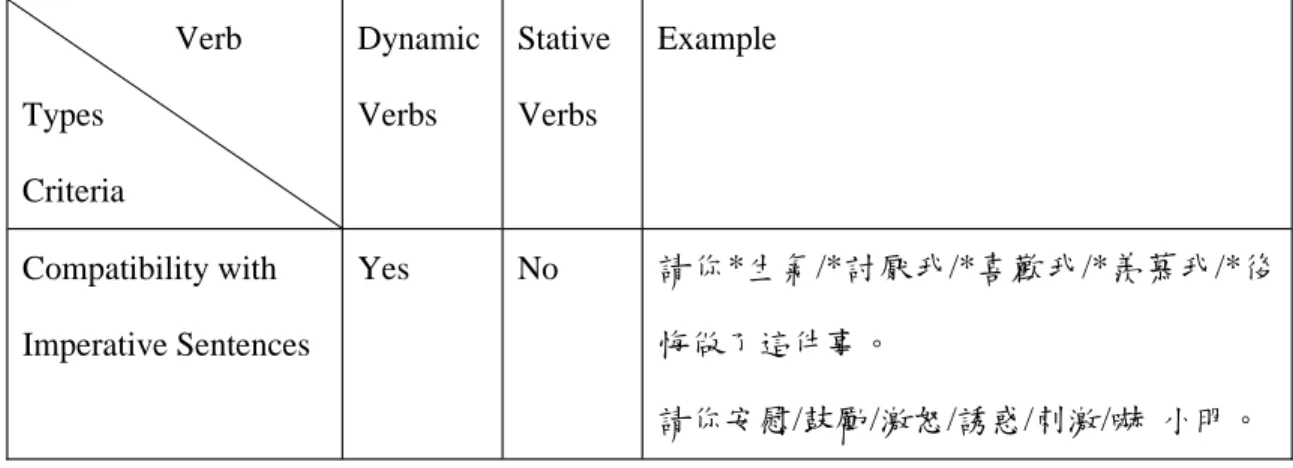

Table 8: The Distinctions between Dynamic Verbs and Stative Verbs ... 34

Table 9: Summary of the Basic Frames under the Emotion Archiframe ... 119

Table 10. Two Micro-frames under the Regret-Sorry Frame ... ... 123

Table 11. The Distribution of Grammatical Functions of Love -Hate Verbs... 123

Table 12. Micro-frames under the Love-Hate Basic Frame ... ... 124

Table 13. Multiple Frames of 煩 FAN ... ... ... 125

Table 14. Multiple Frames of 無聊 WULIAO ... ... 126

Table 15. Micro-frames under the Stimulus -Attributive Basic Frame... 126

Table 16. Morphological Make-up of Verbs in Stimulu-headed Micro-frame ... 127

Table 17. Overview of the Frames in Mandarin Emotion Archi -frame ... 130

Table 18. Defining patterns in archiframe, primary frames, and basic frames ... 132

Lists of Figures

Figure 1. The Twelve Frames and Their Relations under Emotions Frame in Framenet 10 Figure 2: Two Conceptual Frames used in describing emotional activities. ... 18Figure 4. Conceptual Schema of the Emotion Archiframe ... ... 78

Figure 5. The Primary Frames under Emotion Archiframe ... ... 83

Figure 6. The Basic Frames under Emotion Archiframe ... ... 96

Figure 7. The Basic Frames under Exp -Oriented Primary Frame ... . 97

Figure 8. The Basic Frames under Exp -Oriented with Target Frame ... 103

Figure 9. The Basic Frames under Stimulus -Oriented Primary Frame ... 112

Figure 10. The Basic Frames under Affect -Oriented Primary Frame ... 114

Figure 11. The Micro-frames under the Emotion Archiframe ... ... 129

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 The Background

In recent years, the study of lexical semantics has been paying more and more attention and become a centra l research area in linguistics. Lexical units are regarded as a platform displaying the interaction betw een syntax and semantics. Verbs, as the core of lexicon, have drawn especially much attention. A number of studies have investigated and classified verbs in a systematical way via the verbal semantics. (Chiang 2006, Hu 2007, Levin 1993, Liu 1999, Liu 2002, Tsai et al. 1998). As two pilots, Levin (1993) classified English verbs with a diathesis alternation approach while Liu (2002) focused on Mandarin verbs. In the field of Mandarin verbal semantics, however, there are still some issues that need more invest igations: 1) what is the interdependency between syntactic presentations and semantic properties, i.e. what do syntactic pattern tell us about verbs meaning and 2) is there semantic hierarchy? In other words, is the verbal categorization hierarchical or no t? To fill these gaps, this study focuses on Mandarin emotion verbs to provide a frame -based solution to Mandarin verbal semantics.

1.2 The Issue: Emotion Verbs

Emotion verbs are defined in FrameNet (http://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/ ) as an

Experiencer has a particular emotional State, which may be described in terms of a Stimulus that provokes it, or a Topic that categorizes the Stimulu s. Levin (1993:189)

mentioned that the most frequently arguments of emotion verbs (psych -verbs) are experiencer and stimulus. In terms of the expression of these two arguments, psychological (or emotion) verbs in English can be divided into four classes: verbs of

to Levin’s analysis, subject types (or roles) and transitivity are two main diversities encoded in English emotion verbs, as examples below:

(1) Subject types of English emotion verbs a. Expeirencer as Subject

He admired the painting.

b. Stimulus as Subject

The new toys amused the children.

(2) Transitivity of English emotion verbs a. Transitive with Experiencer Subject

He admired the painting.

b. Transitive with Stimulus Subject

The new toys amused the children.

c. Intransitive with Experiencer Subject

Megan marveled at her beauty .

d. Intransitive with Stimulus Subject

The painting appeals to Malinda.

As for Mandarin emotion verbs, the variety of subject roles and transitivity are also equally applicable in Mandarin. However, Mandarin emotion verbs are much more heterogeneous. For example, there shows a great diversity of the subject and the transitivity of Mandarin emotion verbs.

(3) Subject types of Mandarin emotion verbs a. Experiencer as Subject

我很生氣他騙我。

wo hen shengqi ta pian wo

I very angry he deceived me

‘I am very angry that he deceived me.’ b. Stimulus as Subject

這個遊戲很有趣。

zhe-ge youxi hen youqu

this-CL game very interesting ‘This game is very interesting.’ c. Agent-like role as Subject

他激怒了秀蘭。

ta jinu le Xiulan

he anger PERF Xiulan ‘He angered Xiulan.’

(4) Transitivity of Mandarin e motion verbs a. Transitive with Experiencer Subject

我很喜歡他。

wo hen xihuan ta

I very like him

‘I like him very much.’

b. Intransitive with Experiencer Subject 我很生氣。

wo hen shengqi

c. Transitive with Stimulus Subject 這個遊戲吸引許多人。

zhe-ge youxi xiyin xuduoren

this-CL game attract many people ‘This game attracts many people. ’ d. Intransitive with Stimulus Subject

這個廣告太誘人。

zhe-ge guanggao tai youren

this-CL advertisement too alluring ‘This advertisement is too alluring. ’ e. Transitive with Agent-like Subject

我激怒了他。

wo jinu le ta

I anger PERF him ‘I angered him.’

Due to the heterogeneity of Mandarin emotion verbs, some questions arise: what are the unique semantic properties lexicalized in Mandarin emotion verbs, i.e. the syntax-to-semantics correlation? W hat would be a unified approach to distinguish and categorize the different classes of emotion verbs ?

1.3 Scope and Goal

The scope of this study focuses on the verbs depicting emotional states or events. The verbs in question include 生氣 shengqu ‘angry’, 氣 qu ‘anger or be angry’, 惱火

fanzao ‘annoyed’, 煩 悶 fanmen ‘mopey’, 驚 訝 jingya ‘surprise’, 失 望 shiwang

‘disappoint’, 滿 意 manyi ‘be satisfied’, 服 氣 fuqi ‘submit’, 不 滿 buman ‘be dissatisfied’, 爽 shuang ‘comfortable’, 不 爽 bushuang ‘uncomfortable’, 不 平 buping ‘protest’, 不捨 bushe ‘unwilling to give up’, 不服 bufu ‘unwilling to accept’,

高興 gaoxing ‘be glad’, 快樂 kuaile ‘be happy’, 尷尬 ganga ‘be embarrassed’, 羞愧

xiukui ‘be ashamed’, 窘困 jiongkun ‘be embarrassed’, 激動 jidong ‘be flushed’, 難過 nanguo ‘be sad’, 悲哀 beiai ‘be sad’, 痛苦 tongku ‘pain’, 悲傷 beishang ‘be sad’,

悲痛 beitong ‘be painful’, 哀痛 aitong ‘sorrow’, 苦惱 kunao ‘worry’, 不安 buan ‘be discomfort’, 吃驚 chijing ‘be amazed’, 振奮 zhenfen ‘inspire’, 消沈 xiaochen ‘be downhearted’, 為難 weinan ‘be awkward’, 洩氣 xiequ ‘be discouraged’, 沮喪

jusang ‘be depressed’, 陶醉 taozui ‘be intoxicated’, 憂愁 youchou ‘be worried’, 著急 zhaoji ‘be anxious’, 感興趣 ganxingqu ‘be interested in’, 安慰 anwei ‘comfort or be

comforted’, 無聊 wuliao ‘be bored’, 愛 ai ‘love’, 喜愛 xiai ‘like’, 喜歡 xihuan ‘like’, 愛好 aihao ‘love’, 熱愛 reai ‘love’, 喜好 xihao ‘like’, 討厭 taoyan ‘detest’, 厭惡

yanwu ‘detest’, 恨 hen ‘hate’, 痛恨 tonghen ‘hate’, 羨慕 xianmu ‘envy’, 妒忌 duji

‘jealous’, 嫉妒 jidu ‘jealous’, 同情 tongqing ‘sympathize with’, 憐憫 lianmin ‘pity’, 憐惜 lianxi ‘take pity on’ 後悔 houhui ‘regret’, 懊悔 aohui ‘repent’, 懊惱 aonao ‘be remorseful’, 痛悔 tonghui ‘regret’, 悔恨 huihen ‘regret’, 自責 zize ‘be remorseful’, 惋惜 wanxi ‘feel sorry’, 內疚 neijiu ‘be guilty’, 愧疚 kuijiu ‘be ashamed’, 慚愧

cankui ‘be shamed’, 遺憾 yihan ‘feel sorry’, 擔心 danxin ‘worry’, 擔憂 danyou ‘be

anxious’, 憂慮 youlu ‘be anxious’, 焦慮 jiaolu ‘be anxious’, 煩惱 fannao ‘worry’, 苦 惱 kunao ‘worry’, 怕 pa ‘fear’, 害怕 haipa ‘fear’, 畏懼 weiju ‘be afraid of’, 懼怕

jupa ‘be afraid of’, 掛心 guaxin ‘be concerned with’, 牽掛 qiangua ‘be concern about’,

掛念 guanian ‘concern about’, 關心 guanxin ‘be concerned with’, 關切 quanqie ‘be concerned with’, 在 乎 zaihu ‘care about’, 在 意 zaiyi ‘care about’, 吸 引 xiyin

‘attract’, 刺激 ciji ‘stimulate’, 引誘 yinyou ‘seduce’, 迷惑 mihuo ‘confuse’, 誘惑

youhuo ‘seduce’, 誘人 youren ‘alluring’, 累人 leiren ‘exhausting’, 有意思 youyisi

‘interesting’, 令人興奮 ling ren xingfen ‘exciting’, 有趣 youqu ‘interesting’, 無趣

wuqu ‘boring’, 煩人 fanren ‘annoying’, 嚇人 xiaren ‘fearful’, 可怕 kepa ‘terrible’,

感人 ganren ‘touching’, 迷人 miren ‘charming’, 吸引人 xiyinren ‘inviting’, 可愛

keai ‘lovable’, 可笑 kexiao ‘laughable’, 可恨 kehen ‘detestable’, 可憐 kelian ‘pitiable

or sympathize with’, 惹惱 renao ‘anger’, 安撫 anfu ‘pacify’, 撫慰 fuwei ‘console’, 慰問 weiwen ‘console’, 鼓勵 guli ‘encourage’, 激勵 jili ‘encourage’, 鼓舞 guwu ‘inspire’, 折磨 zhemo ‘torment’,打擾 darao ‘disturb’, 打攪 dajiao ‘disturb’, 煩擾

fanrao ‘bother’, 擾亂 raoluan ‘disturb’, 折騰 zheteng ‘torment’, 觸怒 chunu ‘arouse

the anger of’, 惹火 rehuo ‘provoke’, 激怒 jinu ‘anger’, 感動 gandong ‘touch’, 打動

dadong ‘move’, 嚇 xi ‘frighten or frightened’ and so on.

The goal of this study is to classify the Mandarin emotion verbs into frames on the basis of corpus observation and to represent a systematic analysis and categorization of the verbs from grammatical perspective. Moreover, it aims to depict the interrelationship of different emotion frames in a clear way. This study may lead to a better understanding of Mandarin emotion verbs as well as Mandarin verbal semantics.

1.4 Organization of the Thesis

The thesis is organized as follows. Chapter one is a general introduction of the thesis. Chapter two reviews previous studi es related to emotion verbs. Chapter three briefly describes the database and the framework adopted in the study . Chapter four presents the findings motivating this research. Based on the findings, chapter five proposes a frame-based analysis of Mandarin emotion verbs. Finally, chapter six concludes the study and suggests future research topics. Finally, the conclusion of this study and suggestions of future research topics are given in chapter seven.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

This chapter reviews previous studies on emotion verbs as a foundation of the research. A variety of studies have looked at emotion verbs. The verbs discussed, however, are not always referred to as ‘emotion verbs’ in the literature. Therefore, the terms used in pervious works will be briefly listed in section 2.1 in advance. Researches on emotion verbs from different perspectives with diverse approaches will be introduced in the following sections. Section 2.2 introduces the studies on the typology or categorization of emotion verbs in different approaches (Levin 1993, Tsai et al 1996, Chang et al 2000, Liu 2002, and Lai 2004, Berkeley FrameNet Project). Section 2.3 summarizes the chapter and points out the direction of this study.

2.1 Terms Used in the Previous Studies

‘Emotion verbs’ are frequently viewed as a sub-class or sub-type of ‘mental verbs’, or ‘psych verbs’ by some researchers. For example, Croft mentioned that “the class of mental verbs (also known as ‘psych verbs’) includes verbs of perception, cognition and emotion” (1993: 55). Additionally, FrameNet defined the Mental_activity frame : ‘In this

frame, a Sentient_entity has some activity of the mind op erating on a particular Content or about a particular Topic. The particular activity may be perceptual, emotional, or more generally cognitive. ’ As to Mandarin, Mei et al (1993) classified mental predicates

into three sub-classes: cognition verbs, affectio n or emotion verbs, and will verbs. The related terms used in previous studies are briefly listed: ‘mental verbs/predicate ’ (Vendler 1972; Huang 1982; Sweetser 1990; Croft 1991, 1993; Wierzbicka 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka 2002; Su 2002, 2004 ), ‘psychological or psych

Chen 1994, Hana 1996, Yang 2000, Lai 2004). The terms ‘emotion verbs/words/domain’ used in this study are also used in Chang et al (2000), Liu (2002), Les Bruce (2003), Lin (2006), Hsiao (2006, 2007) , and Berkeley FrameNet Project. In addition to studies explicitly on the whole class of verbs in question, there are also studies focusing on only one or two emotion verbs, for example, Tsai et al (1996).

2.2 Typological Studies of Emotion Verbs

Recently, some researchers tried to investigate the typology or categorizations of emotion verbs in different approaches. To introduce these approached in a clear way, the approaches will be organized in divided part s.

2.2.1 Alternation-based Approach

Levin (1993) is a pioneering work on English verb classes and diathesis alternations. Diathesis alternations, by definition, refer to alternations in the expression of arguments, sometimes accompanied by changes of mea ning (Levin 1993:2). It is believed that the grammatical construction is encoded in the lexicon, i.e. the meaning of a verb. Therefore, Levin divided English Psych-verbs, verbs of psychological state , into four sub-classes in terms of transitivity and their expressions of arguments.

Amuse verbs: transitive verbs whose object is the experiencer and whose subject

is the cause of the change.

Admire verb: transitive verbs with experiencer -subject.

Marvel verb: intransitive, experiencer as subject, express the stimulus/object of

emotion in a PP headed by one of a variety of prepositions.

Appeal verb: the least in four subclasses; intransitive, taking the stimulus as subject

In addition to verbs classes, Levin also presented detailed alternation patterns to test the properties of each class of verbs. Take the Amuse type verbs for example. (Here only part of the used alternations in her study is listed.)

(5) *Causative Alternation (most verbs): a. The clown amused the children. b. * The children amused (at the clown). (6) Middle Alternation:

a. The clown amused the little children. b. Little children amuse easily.

(7) PRO-Arb Object Alternation1:

a. That joke never fails to amu se little children. b. That joke never fails to amuse.

This alternation-based framework provided an important criterion to distinguish the properties of verbs. However, some of these verbs included in this class should be further distinguished, and Levin herself also agreed with the argumentation (Levin 1993:191). She further stated Grimshaw ’s (1990) argumentation:

For instance, Grimshaw (1990) argues that some of these verbs, such as amuse, allow the subject/stimulus argument to receive an agentive inter pretation, while others, such as concern, do not; this distinction could be the basis for further subdivision of these verbs. (Levin 1993:191)

1

Levin (1993:38) explained the PRO -arb object alternation:

Moreover, Liu (1996) mentioned that “a purely alternation-based approach may not be adequate for categorizing and describing Mandarin verbs because of the typological and parametric variations among languages. ”

2.2.2 Frame-based Approach

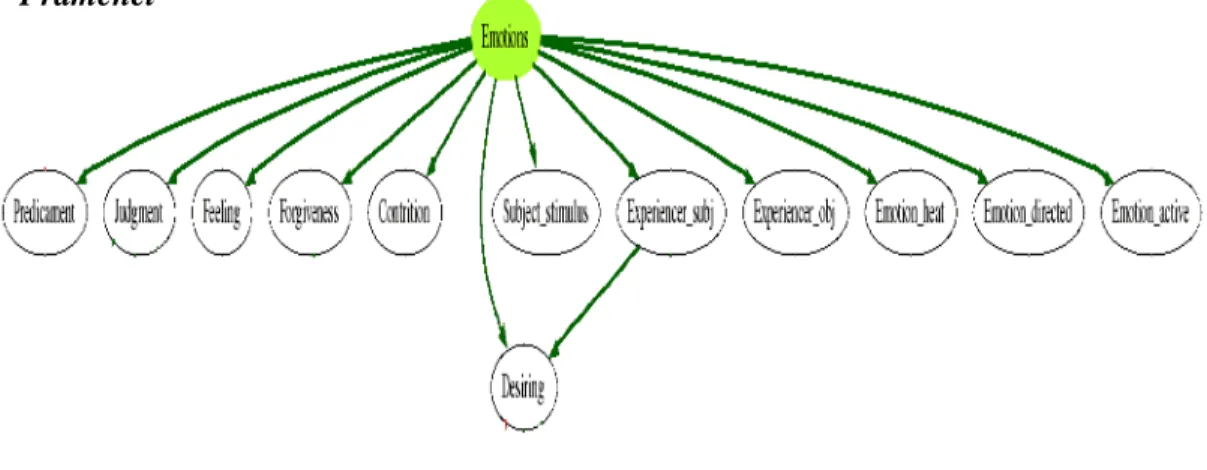

In FrameNet (http://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/) , an on-line English lexical resource based on frame semantics and supported by corpus evidence, shows the hierarchical relationship ( i.e. ‘generation’ in FrameNet) between the parent frame Emotions with its children frames. The Emotion frame has 12 children frames with “Using2” relationship: Predicament frame, Judgments frame, Feeling frame, Forgiveness frame, Contrition frame, Desiring frame, Subject_stimulus frame, Expereience_subject frame, Experience_object frame, Emotion_heat frame, Emotion_directed frame, and Emotion_active frame. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship schema of the Emotion frame with the twelve children frames; Table 1 presents some lexical units in each child frames.

Figure 1. The Twelve Frames and Their Relations under Emotions Frame in Framenet

2‘Using’ is one of the ‘frame-to-frame relations’ given in FrameNet. It is a presupposition relation. ‘A using B’ means ‘A presuppos es B as background.’ When a frame uses part of background information

(E.g. some core semantic frame elements ) of another frame, the two frames are having a using relationship.

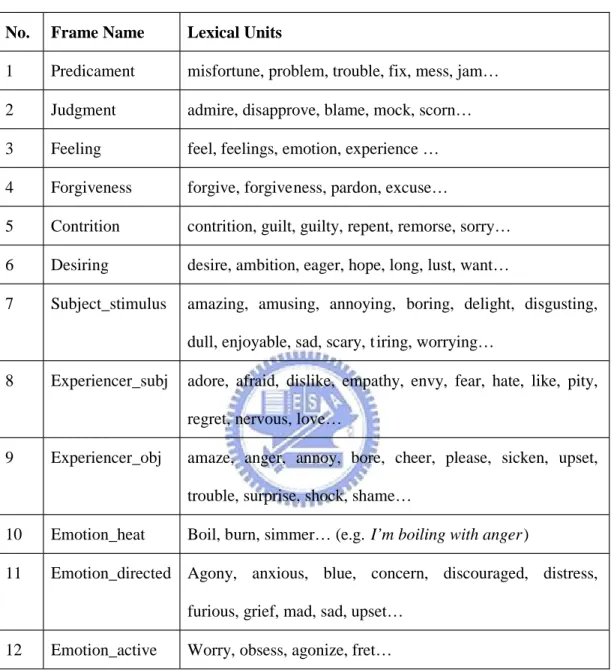

Table 1: 12 Children Frames of the Emotions Frame and Lexical Units in Each Child Frame

No. Frame Name Lexical Units

1 Predicament misfortune, problem, trouble, fix, mess, jam… 2 Judgment admire, disapprove, blame, mock, scorn… 3 Feeling feel, feelings, emotion, experience … 4 Forgiveness forgive, forgiveness, pardon, excuse…

5 Contrition contrition, guilt, guilty, repent, remorse, sorry… 6 Desiring desire, ambition, eager, hope, long, lust, want…

7 Subject_stimulus amazing, amusing, annoying, boring, delight, disgusting, dull, enjoyable, sad, scary, t iring, worrying…

8 Experiencer_subj adore, afraid, dislike, empathy, envy, fear, hate, like, pity, regret, nervous, love…

9 Experiencer_obj amaze, anger, annoy, bore, cheer, please, sicken, upset, trouble, surprise, shock, shame…

10 Emotion_heat Boil, burn, simmer… (e.g. I’m boiling with anger)

11 Emotion_directed Agony, anxious, blue, concern, discouraged, distress, furious, grief, mad, sad, upset…

12 Emotion_active Worry, obsess, agonize, fret…

FrameNet proposed a significant analysis to present the range of semantic and syntactic combinatory possibilities of each word in each of its senses . Moreover, they organized clear frame -to-frame relationships. However, FrameNet did not clarify a explicit hierarchy of the frames. In addition, the analysis based on English lexicon may not be adequate or equivalent to Mandarin Chinese.

2.2.3 Corpus-based Approach

With the development of corpus and data, a number of studies attempted to investigate the properties of Mandarin emotion verbs and categorizing t he verbs from a corpus-based approach.

2.2.3.1 Tsai et al (1996)

In response to the need of fine-tuning verbal semantics, Tsai et al (1996) observed and differentiated a near-synonyms pair to manifest the argument that syntactic contrasts can be predicated from lexical semantics and underlines the importance of interactions between semantics (lexical semantic properties) and syntax (syntactic behaviors).

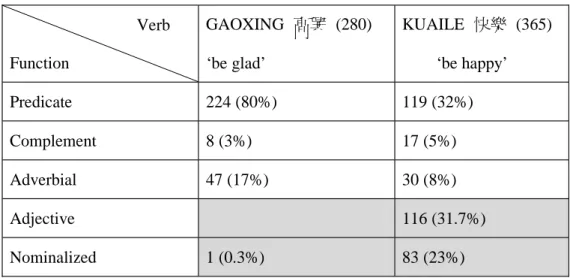

The near-synonyms pair of emotional state verbs , gaoxing 高興 and kuaile 快樂, are semantically similar. Observing the corpus distribution of these two verbs , however, Tsai et al found gaoxing and kuaile are syntactically distinct in many ways and then proposed that the verbs can be differentiated according to their syntactic distribution:

Table 2: The Syntactic Distribution of Gaoxing and Kuaile Verb Function GAOXING 高興 (280) ‘be glad’ KUAILE 快樂 (365) ‘be happy’ Predicate 224 (80%) 119 (32%) Complement 8 (3%) 17 (5%) Adverbial 47 (17%) 30 (8%) Adjective 116 (31.7%) Nominalized 1 (0.3%) 83 (23%)

Gaoxing is typically used as a predicate ( gaoxing takes sentential objects while kuaile cannot.), but barely or never used as adjective (0%) or a noun or nominal

modifier (0.3%); contrarily, kuaile shows a much higher frequency of nominalization (23%) and adjectival using (32%). As examples below:

(8) Transitive predicate:

他們都很高興/*快樂創刊號終於出來了。

tamen tu hen gaoxing/*kuaile chuangkanhao zhongyu chu lai le.

they all very glad/*happy initial issue finally publish PERF/CRS

‘They are all very glad/*happy that the initial issue is published finally. ’

(9) Adjective:

如何做個*高興/快樂的上班族。

ruhe zuo ge *gaoxing/kuaile de shangbanzu

how do CL *glad/happy DE worker ‘How to be a *glad/happy worker ’

(10) Nominalized:

人有追求*高興/快樂,逃避痛苦的本能。

ren you zhuiqiu *gaoxing/kuaile, taobi tongku de benneng

people have seek *glad/happy, evade pain DE instinct

‘People have instinct to seek *gladness/happiness and evade pain ’

Tsai et al proposed that these syntactic contrasts are systematically accounted for with lexical features <change of state> and <control>.

(11) Change-of-state:

a. 客人高興/*快樂了會賞你錢。

keren gaoxing/*kuaile le, hui shang ni qian

customers glad/*happy PERF will give you money

‘Customers would give you money if they have become glad/*happy. ’ b. 他們談得正高興/*快樂。

tamen tande zheng gaoxing/*kuaile le

they chat PROG glad/*happy

‘They are chatting gladly/*happily. ’ c. 從此不再快樂/*高興。

congci buzai kuaile/*gaoxing

frome-now-on no-longer happy/*glad

‘No longer being happy/*glad from now on. ’

(12) Control:

a. 生活快樂/*高興最重要。

shenghuo kuaile/*gaoxing zui zhongyao

life happy/*glad most important

‘Life be happy/*glad is what really matter. ’ b. 別高興/*快樂!

bei gaoxing/* kuaile

don’t glad/*happy ‘Don’t be glad/*happy!’ c. 你應該高興/*快樂才對。

ni yingai gaoxing/* kuaile cai dui

‘You should be glad/*happy and only then it is right. ’ d. 為他高興/*快樂。

wei ta gaoxing/* kuaile

for he glad/*happy

‘Being glad/*happy for him.’

Hence, they divided emotional stative verbs semantically into two groups: homogeneous state verbs which are characterized as <-change of state, -control> and result state verbs characterized as <+change of state, +control> .

Tsai et al (1996) offered convincing evidence that syntactic behaviors can be predicted based on lexical semantics, but it seems that the dichotomous distinction cannot account for the whole semantic field of emotional predicates by only looking at two verbs. Moreover, the semantic features proposed above are general factors which pertain to eventivity. They are too broad to explain the unique b ehavior of the particular class of emotional verbs (Liu, 2002:79).

2.2.3.2 Chang et al (2000)

Chang et al (2000) followed Tsai et al’s dichotomous study mentioned above, and then re-examined a succinct difference over a broader range — the whole semantic field of verbs of emotion. In the study, they first categorized emotional verbs into seven subfields, i.e. Happiness, Depression, Sadness, Regret, Anger, Fear, and Worry; then they revised Grandy’s (1992) definition of a semantic field to propose that there are two covering terms that form a Contrast Pair (Type A and B) that define each semantic field. And then they thoroughly examined the seven contrast pairs of subfields of emotional verbs and predicted that the other verbs being members of the field will behave like

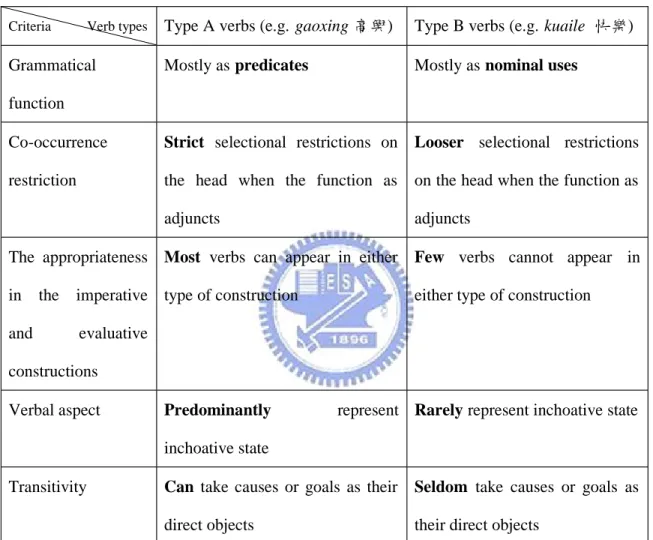

Chang et al examined the contrasts between the two types based on five distributional syntactic criteria. They found that type A and type B verbs can be characterized as below:

Table 3: The Contrastive Distribution of Type A and Type B Verbs

Criteria Verb types Type A verbs (e.g. gaoxing 高興) Type B verbs (e.g. kuaile 快樂) Grammatical

function

Mostly as predicates Mostly as nominal uses

Co-occurrence restriction

Strict selectional restrictions on the head when the function as adjuncts

Looser selectional restrictions on the head when the function as adjuncts

The appropriateness in the imperative and evaluative constructions

Most verbs can appear in either type of construction

Few verbs cannot appear in either type of construction

Verbal aspect Predominantly represent inchoative state

Rarely represent inchoative state

Transitivity Can take causes or goals as their direct objects

Seldom take causes or goals as their direct objects

From the above contrast, Chang et al generalized that type A verbs are preferred for indicate transition while type B verbs are preferred for homogeneity. What kind of reason drives the grammatical differences? They conclude that the grammatical contrasts derive from their morphological structures. A VV compound is double-headed and does not elaborate. Therefore, in VV compounding, the concept of an event is not so

clear. It is common morpho-lexical strategy in Mandarin to link two antonyms or synonyms to form the conc ept of ‘kind’ or ‘property’, and therefore it is natural for VV compounds to be chosen as the representation of homogeneity.

Hence, verbs of emotion are morphologically separated by Chang et al into Non-VV compound and VV compound. Type A verbs are Non-VV compound, while type B verbs are VV compound.

Type A: gao xing 高興(non-VV), nan guo 難過(non-VV), hou hui 後悔(non-VV), shang

xin 傷心(non-VV), sheng qi 生氣(non-VV), hai pa 害怕(non-VV), dan xin 擔心

(non-VV)

Type B: kuai le 快樂(VV), tong ku 痛苦(VV), yi han 遺憾(AN or VO), bei shang 悲傷 (VV), fen nu 憤怒(VV), kong ju 恐懼(VV), fan nao 煩惱(VV)

Chang et al (2000) extended range of the study to seven subfields of emotion verbs, and further proposed a morphological -makeup explanation, but these seven types of verbs were still not enough or adequate to present the heterogeneous properties of Mandarin emotion verbs (see Chapter 4). Besides, there is a flaw in their analysis: the verb yi han 遺憾 judged as a AN or VO compound is located in the type B, i.e. VV compound verbs. Liu (2002:79) pointed out “the morphological account is at best an observation associated with and resulted from a deeper semantic relation. It fails to explain the semantic driving force for the paradigmatic variation.”

2.2.3.3 Liu (2002)

Different from Tsai et al (1996) and Chang et al (2000), Liu (2002) looked at near-synonyms pairs of emotion activity verbs, XIANMU 羨慕‘envy’ and JIDU 嫉妒‘be jealous of’, and found that CAUSE is a crucial parameter in the event structure of

conceptualizing emotional activities. The event can be perceived as a self -motivated action with the Expeirencer coded as an actor projecting an internal state towards a Target or Stimulus. (e.g. 我羨慕他。wo xianmu ta ‘I envy him.’) It can also be perceived as a caused state with the Experiencer being coded as a Causee undergoing a change affected by a Causer. (e.g. 他讓我羨慕。ta rang wo xianmu ‘He makes me envious.’)

Figure 2: Two Conceptual Frames used in describing emotional activities. a) SELF-MOTIVATED ACTION

b) CAUSED STATE

Liu mentioned that these two conceptual frameworks may be conflated into a three-stage causal chain: Causer arouses an emotional state in the Experiencer toward a Target.

Based on the causal frameworks, Liu highlighted the crucial role of CAUSE as a semantically essential variable . Liu found that the CAUSE may be encoded as an NP-object, an NP-subject, a preposed NP-Goal, a clausal object, or a preposed clausal-subject and found the CAUSE form is often overtly marked in a sentence (1 3). However, there are also cases where the role CAUSE is not overtly mentioned (1 4).

(13) a.我 非常 嫉妒[NP 他的成功]。

wo fenchang jidu ta de chenggong

I unusually JIDU he De success ‘I am very jealous of his success. ’

b.對[NP他的成功] 我 非常 嫉妒。

dui ta de chenggong wo fenchang jidu

to he De success I unusually JIDU ‘Of his success, I am very jealous. ’

c. 我 羨慕 [CP他會說不同的語言]。

wo xianmu ta hui shui butong de yuyan

I XIANMU he can speak not same De Language ‘I envy that he can speak different languages.’

(14) a. 你 只會 嫉妒。

ni zhi hui jidu

you only can JIDU

‘You are only capable of bei ng jealous.’

b. 被 貪婪 嫉妒所 緊縛

‘Tightly bound by greed and jealousy. ’

Examining distribution of CAUSE between the verbs, XIANMU 羨慕‘envy’ and

JIDU 嫉妒‘be jealous of’, Liu found that an obvious skewing in the frequency of overtly

marked CAUSE.

Table 4: Distribution of CAUSE: XIANMU 羨慕 vs. JIDU 嫉妒

XIANMU 羨慕 (112) ‘envy’ JIDU 嫉妒 (38) ‘be jealous’ Mention (NP or S) 100% (112) 45% (17) No Mention 0% (0) 55% (21)

Hence, Liu proposed that there are two types of Cause, External vs. Internal CAUSE, and classified emotional activity verbs into two groups based on the distinctive role CAUSE. Externally caused verbs are more controllable and more justifiable; internally caused verbs are less control and less justifiable.

Liu also showed that other sets of emotional verbs also support her finding, such as verbs of anger (SHEGQI 生氣 vs. FENNU 憤怒), verbs of fear (HAIPA 害怕 vs.

KONGJU 恐懼), verbs of sadness (SHANGXIN 傷心 vs. BEISHANF 悲傷), and verbs of

depression (NANGUO 難過 vs. TONGKU 痛苦). Finally, Liu utilized MARVS (the Module-Attribute Representation of Verb Semantics) (Huang et al. 2000, Chang et al. 2000) to specify the event module and role module of externally and externally caused emotional activity verbs.

Liu (2002) clearly presented the interaction between syntactic behavior and semantic properties. The three-stage causal chain proposed in her study provided a simple and useful cognitive schema of conceptualization of emotion events. Therefore,

following Liu’s study, we will propose an extended and elaborated causal schema based on the causal relation established in the study (see section 5.2).

2.2.3.4 Lai (2004)

In this paper, Lai attentively observed the syntactic realizations or constructions of three set of verbs, trying to explore the subtle distinctive features and meaning in Chinese emotion (psychological) predicates. In order to single out representative verbs for convincing investigation , Lai selected verbs with four criteria: the argument structure, the meaning of verbs, the frequency of occurrence, and the morphological structures. Three most frequently used monosyllabic psych verbs and their most-used bi-syllabic counterparts were finally selected for further examination . The selected emotion verbs are愛 ai ‘love’, 喜歡 xihuan ‘like’, 氣 qi ‘angry or get angry’, 生氣

shengqi ‘get angry’, 怕pa ‘fear or be afraid’ and 害怕haipa ‘be afraid’. Although did not be selected, the verb 嚇 xia ‘frighten’ is put into the following discussion in the study.

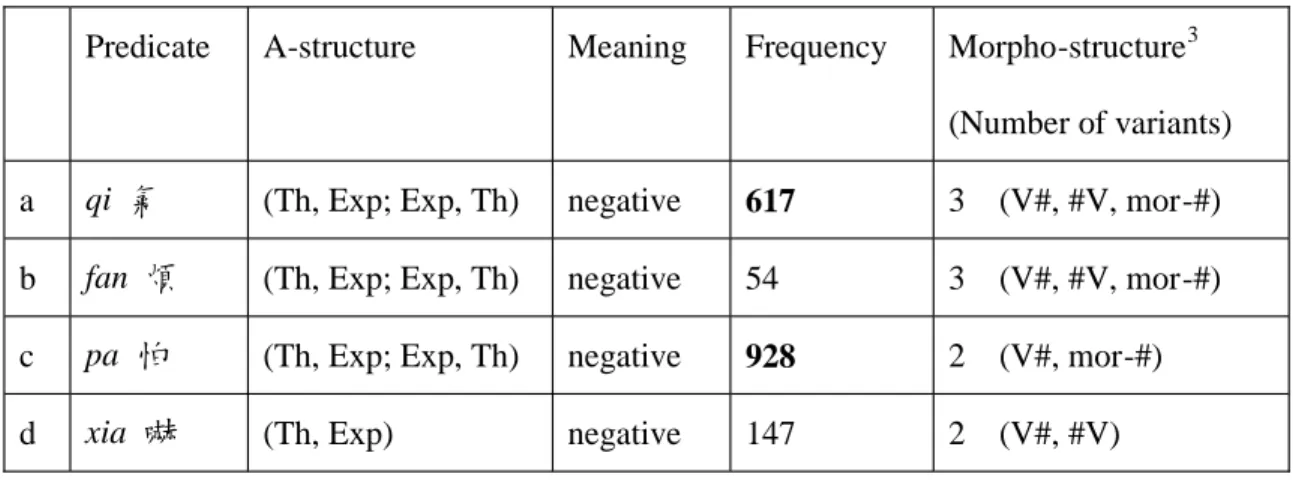

Table 5: Interaction between Criteria and Psych Predicates

Predicate A-structure Meaning Frequency Morpho-structure3 (Number of variants) a qi 氣 (Th, Exp; Exp, Th) negative 617 3 (V#, #V, mor-#) b fan 煩 (Th, Exp; Exp, Th) negative 54 3 (V#, #V, mor-#) c pa 怕 (Th, Exp; Exp, Th) negative 928 2 (V#, mor-#) d xia 嚇 (Th, Exp) negative 147 2 (V#, #V)

3

According to Lai (2004:50), “Morph -structure” is “morphological structure,” referring to components of a compound. The symbol “#” stands for the psych predicates listed in the first column. “V” stands for a

e nu 怒 (Exp) negative 68 1 (V#) f hen 恨 (Exp, Th) negative 140 2 (V#, mor-#)

g ai 愛 (Exp, Th) positive 1925 3 (V#, #V, mor-#)

h teng 疼 (Exp, Th) positive 85 2 (#V, mor-#)

Considering a sentence like (15), Lai found that there are two readings deduced from the same clause, as (16) illustr ates.

(15) 他氣他媽媽

ta qi ta mama

he anger he mother

(16) a. ‘He was angry with his mother. ’(Exp, Th) b. ‘He made his mother angry.’ (Th, Exp)

The meaning coded in (15) can be either ‘he was angry with his mother ’ or ‘he made his mother angry’. Lai proposed that the concept [CAUSE] is the distinguishing factor. The conflation of [CAUSE], m ore precisely, the incorporating CAUSE into the predicate happens in a construction with Theme as the subject . Therefore, Lai further divided the psychological or emotion verbs into groups by CAUSE:

Table 6: Three Types of Psychological Predicates in Terms of CAUSE

Conflation Remarks Examples Argument Structure

1

No [CAUSE]

-愛 ai ‘love’, 恨 hen ‘hate’, 怕 pa ‘fear’

2

[CAUSE]

Free expression

煩 fan ‘worry’, 氣 qi

‘anger’, 嚇 xia ‘frighten’

[Theme, Experiencer]

3 Fixed expression 怕+人 pa+ren ‘fear+people’ [Theme, Experiencer]

Lai pointed out that there is an overlap of the verb attributes between the first type and the third type. For example, 怕 pa ‘fear’ is generally a verb with the Experiencer as the subject. When collocating with 人 ren ‘people’, however, it coerces the concept [CAUSE]. The argument structures of the types are also discussed: the argument structure of [-CAUSE] type is [Experiencer, Theme] while the argument structure of [CAUSE] type is [Theme, Experiencer]. What need to be pay more attention is that the argument structure of the first type [ -CAUSE]怕 pa ‘fear’ originally is [Experiencer, Theme], but becomes [ Theme, Experiencer] in the third type coercively when taking the object 人 ren ‘people’. Based on the observation, Lai divided emotion verbs into three types: Theme-Subject predicates (e.g. 嚇 xia ‘frighten’), Experiencer-Subject

predicates (e.g. 愛 ai ‘love’, 喜歡 xihuan ‘like’, 生氣 shengqi ‘get angry’, and 害怕

haipa ‘be afraid’), and amphibious predicates (e.g. 氣 qi ‘angry or get angry’, and 怕 pa ‘fear’). Verbs of the third type are treated as amphibious p redicates because they can

be regarded as Theme-Subject or Experiencer-Subject. Verb types and corresponding examples are illustrated in (17):

(17) Three Types of Psychological Predicates a. Theme-Subject predicates

他嚇了我一跳

ta xia le wo yi tiao

‘He just frightened me.’ b. Experiencer-Subject predicates

他愛小華

ta ai Xiao Hua

he love Xiao-Hua ‘He loved Xiao-Hua.’

c. Amphibious predicates 他氣他媽媽

ta qi ta mama

he angry/ anger he mother

‘He was angry with his mother.’(Exp, Th) ‘He angered his mother. ’ (Th, Exp) 他很怕人

ta hen pa ren

he very fear/ make fear people ‘He was afraid of people.’ (Exp, Th) ‘He was very frightening.’ (Th, Exp)

After selecting and categorizing verbs, Lai next presented the syntactic realizations of the seven verbs from corpus observation in detail, and tried to point out the subtle differences on meanings among these verbs by looking into the construction in which verbs can or cannot occur. In other words, they tried to explore the interaction s between constructions and meanings of emotion verbs.

Take the agentivity of 愛 ai ‘love’ and 怕 pa ‘fear’ for example. The sentences in (18) may raise a question: what factors can differentiate 愛 ai ‘love’ and 怕 pa ‘fear’ since both of them take gradable adverbials and both have the Experiencer as the subject?

(18) a. 我漸漸(地)愛上貓。

wo jianjian (di)ai shang mao

I gradually love up cat ‘The cats grew on me.’ b. 我漸漸(地)怕貓。

wo jianjian (di)pa mao

I gradually fear cat

‘I feel scared of cats gradually. ’

To answer the question, Lai found that the diversity of agentivity between the two verbs can be a key. Lai adopted four adverbial phrases, including 全心全意 chuan-xin

chuan-yi ‘dedicatedly’, 故意 gu-yi ‘deliberately’, 考慮 kao-lu ‘intentionaly’, and 不

自禁地 bu zi-jin di ‘uncontrollably’ or 不由自主地 bu you zi-zhu di ‘spontaneously’, to test the agentivity of verbs. The collocational relation between adverbs and emotion verbs are shown in table (7).

Table 7: Adverbials for Agentivity

Adverbial 愛 ai 喜 歡 xihuan 怕 pa 害 怕 haipa 氣 qi 生 氣 shengqi 1 chuan-xin chuan-yi + + — — + —

Ex.: 小明全心全意愛著小華。 xiao-ming chuan-xin chuan-yi ai-zhe xiao-hua ‘Xiao-Ming loves Xiao-Hua wholeheartedly.’

2 gu-yi — — — — + —

Ex.: 他故意要氣小華。 ta gu-yi yao qi xiao-hua ‘He angered Xiao-Hau on purpose.’

3 kao-lu — — — — + —

Ex.: 我考慮要氣陳小姐。 wo kao-lu yao qi chen-xiao-jie ‘I am considering if I will make Miss Chen angry deliberately .’ 4 bu zi-jin di

bu you zi-zhu di

+ + + + — —

Ex.: 我不自禁地害怕他。 wo bu zi-jin di haipa ta ‘I cannot help but fear him. ’

When adding a adverbial phrase 全心全意 chuan-xin chuan-yi ‘dedicatedly’, the sentences with 愛 ai ‘love’ is grammatical while the sentence with 怕 pa ‘fear’ become odd, as (19) presents:

(19) a. 我全心全意愛貓。

wo chuan-xin chuan-yi ai mao

I dedicatedly love up cat ‘I love cats dedicatedly.’ b. *我全心全意怕貓。

wo chuan-xin chuan-yi pa mao

I dedicatedly fear cat

Based on the contrast, Lai claimed that the SubExp (Experiencer as the subject) of 愛 ai ‘love’ is active and capable of taking the initiati ve in doing something to the ObjTh (Theme as the object) but the SubExp of 怕pa ‘fear’ lacks this attribute and is passive.

In addition to transitivity, Lai also categorized and observed the patterns exhaustively by characteristics of transitivity (comple ment variants), modifier, event structure, causative constructions, resultative constructions and so on to figure out the subtle distinctive features and meanings among Mandarin emotion (psychological) predicates.

Lai (2004) tried to off all possible con structions of the seven psychological predicates and to sort out subtle meanings coded in the constructions. This study actually did a detailed and impressive observation and prominently demonstrated the relationship between form and meaning. However, ther e are still some flaws in the study. First, Lai divided the seven verbs into three types, and included the verb 怕 pa ‘fear’ among the type of amphibious predicates because 怕 pa ‘fear’ is coerced to germinate the concept of [CAUSE] when collocating with an obje ct 人 ren ‘people’. What arises our question is the two readings of (17b) 他很怕人 ta hen pa ren ‘he very fear/ make fear people’. Does (17b) actually have the meaning He was very frightening? Testing several native speakers of Mandarin, we do not find the readin g. Besides, it would have been more persuasive if the author had explained among verbs in first type, why only 怕 pa ‘fear’ could be an amphibious predicate? Second, only seven emotion predicates are observed and examined in this study. Although these verbs are representative to a certain extent, they still cannot represent all emotion verbs and fail to examine a difference and to provide an explanation over the whole semantic field of verbs of emotion. For example, what are the differences in syntactic realizations and semantic

properties between high frequency verb such as 高興 gaoxing ‘be glad’ or 快樂 kuaile ‘be happy’4and the seven discussed verbs in this paper? Third, the study presented all possible syntactic constructions of each verb from a variety of perspectives ; however, no defining pattern or construction5 of each type of verbs is provided to capture the distinguishing meanings from type to type, and to establish a criterion for verb classification.

2.3 Summary

Emotion verbs in different languages have been investigated from various perspectives and a number of studies focused on emotion verbs from a typology perspective (Levin 1993, Tsai et al 1996, Chang et al 2000, Liu 2002, and Lai 2004, Berkeley FrameNet Project ). Levin’s (1993) study based on a diathesis approach; FrameNet settled the English emotion verbs in a frame-based approach. As to corpus-based approach, Tsai et al 1996, Chang et al 2000, Liu 2002, and Lai 2004 all provided detailed observation and finding between lexical meaning and syntactic behavior. Though a considerable number of studies have been de dicated to the unique behavior of emotion verbs, most of the previous studies only looked at a small portion or part of the emotion verbs. What needed is a comprehensive and integrated study of the whole class members . This paper takes up the task and aims to explain and interpret the specific and heterogeneous properties in syntax and semantic of Mandarin emotion verbs, and to provide a systematic account for the syntax -to-semantics correlations of Mandarin emotion verbs by applying a frame-based analysis.

4

Frequency of 高興 gaoxing ‘be glad’ and 快樂 kuaile ‘be happy’ are both higher than 500. The frequency of 高興 gaoxing ‘be glad’ is 667, and 快樂 kuaile ‘be happy’ is 938.

5

A defining pattern is a syntactic pattern relevant to a certain frame or type of verbs. O nly verbs which can fit into the defining pattern can be classified as belonging to the frame or type. This notion is corresponding to the theoretical assu mptions of Construction Gramm ar (Goldberg 1995, 2006) that regards constructions as form-meaning pairs.

Chapter 3

Database, Theoretical Framework and Methodology

This chapter contains the database, frameworks and methodology which are utilized and adopted in this study. The database from which we obtain corpus is introduced firstly. The frameworks adopted to help the analysis will be presented next. Lastly, the methodology including the steps of research will be briefly described.

3.1 Database

The analysis in this study is based on corpus data . The analyzed data mainly come from Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese , simplified as Sinica Corpus (http://www.sinica.edu.tw/SinicaCorpus/). Sinica Corpus is a freely online corpus with part-of-speech tagging. It is the first balanced Chinese corpu s and the data are extracted from texts with topics in society, life, literature, philosophy, science and art. The size of present corpus (version 4.0) is 7,949,851 million words. Other resources utilized in this research are: t he FrameNet (http://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/), an on-line English lexical resource based on frame semantics and supported by corpus evidence; the Chinese Word Sketch (http://wordsketch.ling.sinica.edu.tw/), a corpus management tool and sketch engine which provides grammar -wise co-occurrence statistics; the Academia Sinica Bilingual Ontological WordNet (Sinica BOW,

http://bow.sinica.edu.tw/), an English-Chinese bilingual wordnet and a bilingual lexical access to SUMO; the web research engine Google (http://www.google.com.tw/), and the translation software - Dr. Eye 8.0.

3.2 Theoretical Framework

In this study, the analysis is based on the theory of frame semant ics by Fillmore and Atkins (1992) and the classification is based on a frame taxonomy proposed in Liu and Chiang (2008).

3.2.1 Frame Semantics

Frame semantics, which is proposed by Fillmore an d Atkins (1992), is a semantic theory based on the notion of cognit ive frames or knowledge schema . It can be thought of as a concept with a script. As Fillmore and Atkins (1992:76-77) noted:

In such theories, a word ’s meaning can be understood only with re ference to a structured background of experience, beliefs, or practices, constituting a kind of conceptual prerequisite for understanding the meaning. Speakers can be said to know the meaning of the word only by first understanding the background frames that motivate the concept that the word encodes. Within such an approach, words or word senses are not related to each other directly, word to word, but only by way of their links to common background frames and indications of the manner in which their meaning highlight particular elements of such frames.

Fillmore and Atkins suggested that each frame should contain some core frame elements that comprise the concept of this frame. They took the commercial transaction frame for example and pointed that Buyer, Seller, Goods, and Money are four essential elements in any commercial event scene. In this way, word senses can be distinguished by their highlighted frame elements and background knowledge.

The concept of frame semantics has been put into practice that Fillmore and others scholars constructed an on-line lexical resource for English based on frame semantics and this database is named FrameNet in which a frame is defined with its essential

Frame Elements and the syntactic patterns with the frame elements are listed in the annotation data of each lemma in the frame.

3.2.2 Framework of Mandarin VerbNet

In this paper, we will mainly adopt the framework proposed in Liu and Chiang (2008). To capture the different scopes of semantic specification and degree of lexical granularity inherent in different frames, a multi -layered hierarchical taxonomy distinguishing the varied scopes of frames according to the syntax -to-semantics correspondence is proposed. There are four layers of frames: Archiframe > Primary frame> Basic frame > Microframe. The lower-layered frames are subframes of the higher-layered frames.

As their illustration, an archiframe corresponds to a broad semantic domain that provides a maximal scope of background information for a unique event type. Pr ecisely speaking, an archiframe is distinguished along a relatively broad and self -containing conceptual schema with a default set of participant roles (i.e. frame elements). A primary frame represents a major relational subpart of an archi-frame, i.e. a primary frame is defined as a subpart of the archi -schema with a unique set of core frame elements. A basic frame highlights a particular participant role or relation within the upper frame, i.e. the primary frame. In order words, basic frames are distingui shed according to syntactically expressed patterns of foregrounding or backgrounding certain frame elements. A basic frame may be further divided into microframes. A microframe is distinguished according to role -internal specifications of frame elements.

According to Liu and Chiang, each frame is specified with a definition, a unique set of frame elements, frame -level basic or defining patterns (grammatical expressions of core Frame Elements), a subpart of conceptual schema, and representative lemmas.

3.3 The Methodology

To capture and analyze the interaction between syntactic behaviors and semantics properties of Mandarin emotion verbs, four steps are followed.

Step 1: Finding the Mandarin emotion verbs

We made reference to the English database FrameN et to find the emotion-relevant frames and lexical items included in these frames. Based on the lexical items in FrameNet, equivalent Mandarin lemma s were obtained through Sinica BOW and Dr. Eye. The linguistics intuition then helped to sieve out the unrelated words from the equivalent lemma, and to add some related but neglected lexicons. During the analysis, some emotion verbs which were not found in this step would be put into examination as well.

Step 2: Collecting the corpus data

After determining the lemmas, we searched and collected sentences with targeted emotion predicates in Sinica Corpus and Chinese Word Sketch. Linguistics intuition also did help in this step. Additionally, the search engine Google was used sometimes to prove or verify the intuition.

Step 3: Observing and examining the data

To examine explicitly the syntactic presentations and semantic features of emotion verbs, we observed the verbs particularly in their 1) grammatical function, 2) syntactic categories, 3) frame elements (participant roles of an event), 4) syntactic patterns or structures, and 5) grammatical collocations.

Finally, the previous findings, i.e. the unique frame elements, syntactic patterns and functions of observed verbs, were treated as criteria to analyze and categorize emotion verbs into separated class or groups.

Chapter 4 Findings

This chapter aims to present and describe some findings obtained during corpu s observation. Both syntactic and semantic representations of Mandarin emotion verbs will be delineated, including 1) event types, 2) transitivity, 3) alternations, 4) subject roles, 5) participant roles and 6) syntactic patterns of the verbs with the part icipant roles. The six findings will be introduced respectively in Section 4.1 to Section 4.6. A summary of this chapter will be given in Section 4.7. Based on all the findings, the Mandarin emotion verbs can be further analyzed and categorized into different levels and frames (See Chapter 5).

4.1 Event Types

Tang T.-C. (2000:14-15) suggested a criteria for the distinctions between dynamic verbs and stative verbs: Compatibility with Imperative Sentences , Collocation with Benefactive Role, Collocation with Patient Role, Functioning as Complements of Verbs of Intention, and Functioning as Complements of Verbs of Causation .

Table 8: The Distinctions between Dynamic Verbs and Stative Verbs Verb Types Criteria Dynamic Verbs Stative Verbs Example Compatibility with Imperative Sentences Yes No 請你*生氣/*討厭我/*喜歡我/*羨慕我/*後 悔做了這件事。 請你安慰/鼓勵/激怒/誘惑/刺激/嚇 小明。

Collocation with Benefactive Role Yes No 替他*生氣/*討厭我/*喜歡我/*羨慕我/*後 悔做了這件事。 替他安慰/鼓勵/激怒/誘惑/刺激/嚇 小明。 Collocation with Patient Role Yes No 你給我*生氣/*討厭我/*喜歡我/*羨慕我/* 後悔做了這件事。 替他安慰/鼓勵/激怒/誘惑/刺激/嚇 小明。 Functioning as Complements of Verbs of Intention Yes No 他想要*生氣/*討厭我/*喜歡我/*羨慕我/* 後悔做了這件事。 他想要安慰/鼓勵/激怒/誘惑/刺激/嚇 小 明。 Functioning as Complements of Verbs of Causation Yes No 要他*生氣/*討厭我/*喜歡我/*羨慕我/*後 悔做了這件事。 要他安慰/鼓勵/激怒/誘惑/刺激/嚇 小明。

Based on the criteria, Mandarin emotion ve rbs can be divided into dynamic and stative verbs.

In addition to the criteria proposed by Tang T.-C. (2000), previous literature argued that aspectual properties serve to convey event types of sentences (Vendler 1967, Smith 1997, Van Voorst 1988, Levin & Rappaport 2005). In this study, we notice that Mandarin emotion verbs display a variation of aspectual properties that helps to examine and further verify the event types of verbs. The aspectual variations are illustrated as below:

(20) Collocation with the PROGRESSIVE aspectual marker 正在 zhengzai/在 zai a. *我正在高興你對我吐露心聲。

wo zhengzai gaoxing ni dui wo tulu xinsheng

I PROG glad you to I tell thoughts

‘I am glading that you told me your thoughts. ’

*黃樹剛正在後悔劫機行為但不正在後悔反共。

Shu-Gang Huang zhengzai houhui jieji xingwei dan bu zhengzai houhui fangong

Shu-Gang Huang PROG regret hijack an airplane but not PROG regret Anti-Communism

‘Shu-Gang Huang is regretting for his hijacking an airplane but is not regretting for Anti-Communism.’

*他在喜歡打網球。

ta zai xihuan da wangqiu

he PROG like play tennis ‘He is liking to play tennis. ’

*爸爸正在害怕坐飛機。

baba zhengzai haipa zuo feiji

father PROG fear travel by airplane ‘Father is fearing to fly in an airplane. ’

*這個運動在累人。

zhe ge yun dong zai leiren

this exercise PROG tiring ‘This exercise is tiring people.’

*票價在很嚇人。

piaojia zai hen xiaren

ticket fare PROG very frightful

‘The ticket rare is frightening people very much. ’

b. 他現在正在安慰著我。

ta xianzai zhengzai anwei zhao wo

he now PROG comfort I ‘He is comforting me now.’

飢餓和勞累在折磨他

jie he laolei zai zhemo ta

hunger and tiredness PROG torment he ‘Hunger and tiredness is tormenting him. ’

她在引誘我犯罪。

ta zai yinyou wo fanzui

she PROG seduce I commit a crime ‘She is seducing me to commit a crime. ’

這個小孩正在激怒他的媽媽。

zhege xiaohai zhengzai jinu ta de mam a

this-CL child PROG anger he DE mother ‘This child is angering his mother. ’