公有地悲劇的再探:英國中世紀公有地制度對於二十一世紀全球治理的啟示 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Acknowledgements This has not been the easiest thing to do, but I have enjoyed the process very much thanks to a great many people who helped me along the way. I would like to thank, first and foremost, my thesis adviser Prof. Ho-Ching Lee (李河清) of National Central University for the many inspirations—academic, professional, and bigger than life—that brought me to write this topic. I would like to thank my two committee members, Prof. Ai-Ching Yen (顏愛 靜) of National Chengchi University and Prof. Tze-Luen Lin (林子倫) of National Taiwan University, for their timely efforts to my cause. They have all made my endeavors much easier and more fruitful.. 治 政 I regret that due to urgent requirements needed for大 my future military service, I am 立 compelled to finish my thesis in a very compressed timeframe. I am aware that there are ‧ 國. 學. many places that I could have done much better, but could not do so, time-wise. I would like. ‧. to thank my respectable committee members again for such generous understanding and. sit. y. Nat. support. I am sincerely grateful for them bearing with me on such tight time schedule to. io. er. finish. However, I take full and sole responsibility for any errors and mistakes in this paper.. al. n. Furthermore, I would also like to thank many teachers who provided me valuable insights and suggestions along. iv n C the way: Yves Turbingen h e nProf. gchi U. of University of British. Colombia, Prof. Yia-Ling Liu ( 劉 雅 靈 ) of National Chengchi University, Prof. Eric Chen-Hua Yu (俞振華) of National Chengchi University, and Prof. Ching-Ping Tang (湯京平) of National Chengchi University (listed in chronicle sequence of courses taken with these professors). I would like to thank those who gave suggestions, critiques, and encouragements to my different chapters during various seminars: Prof. Chang Teng-Chi (張登及), Prof. Yu-Tai Tsai (蔡育岱), Hui-Yin Sung (宋蕙吟), Sheng-Chih Terence Wang (王聖智) , Szuning Ping (平思寧), and Szu-Hsien Lee (李賜賢). Additionally, I would like to thank Prof. Chia-Hsiung Chiang (姜家雄) for supporting me greatly in recruiting me to be his teaching assistant, which I found to be an inspiring i.

(3) experience. This one-year experience has encouraged my aspiration to become a professor one day. I would also like to thank my fellow peers who supported me emotionally and physically day in and day out: Xavier, Tony, Uri, Geobert, Barry, and most of all, Charlotte. I would also like to thank those who studied and traveled together with me under supervision of Prof. Ho-Ching Lee: Tracy, Linyun, Potsang, Ya-Hsu, and Yu-Tzu. I would also like to thank my support groups for constant understanding and encouragement: the counselor team of Victory Church Youth Fellowship, NMUN2011, YAIC, EDP Staff of 2008-2010, TWYCC, my high school soccer teammates, and my college classmates.. 治 政 Last but not the least, I would like to thank my two大 roommates—Rodman and Rexi— 立 who accompanied me through this long journey by accepting who I am and how I am at ‧ 國. 學. home. I would like to thank Rexi, John, and Joyce who helped my borrow research related. ‧. books that my school didn’t have, which made my research possible. I would like to thank. sit. y. Nat. Rose for always being there for me when I lock myself out of the research room. I would also. io. al. er. like to thank the fantastic places that allowed me to work on my master thesis: my. n. postgraduate research rooms, the school library’s social science branch, and McDonald’s Dehe Branch.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Most importantly, I am grateful for the love and support from home. I could not have dreamed for a better family: Dad, Mom, my younger sister. Finally, I thank God for his amazing guidance and grace. I could not have done this without Him.. Shou-Tao Liang (Joseph) January 29, 2013 in Muzha. ii.

(4) English Abstract As identified by Elinor Ostrom, a third approach to collective action on common resource management was the “community”. This important finding seemed to have been timely for contributing to academic debates on the issues of “democratic deficiency” and the “human security” aspects of bottom-up approaches in overall global governance. In recent years, modern-day enclosure movements in places around the world have led to international peasantry movements. Interestingly, the empowerment of individuals and communities these movements are fighting for are nothing new. Just as Ostrom has shone in some of her cases, it was how agrarian human society functioned at the local level before the industrial. 治 政 revolution—with some kind of communal decision making 大 process in place to decide on 立 essential issues impacting peasants’ livelihood activities and where most people affected were ‧ 國. 學. involved in the process. Choosing the same “commons” Garret Hardin alluded to as a. ‧. “tragedy”, I asked the center question of the paper: What light can the British medieval. sit. y. Nat. commons, as a historical case and a long-enduring institution, shed on community-based. io. er. institutions and even global governance today? From the case, I argue that local communities. al. and individuals should be given social, economic, and even political empowerment and. n. iv n C recognition for the livelihood institutions depend on. This study shows that when local h ethey ngchi U and national authorities decide not to support this empowerment and give recognition, it brings tragedy to those whose livelihoods depended on the institution. Learning from the institutional shortcomings of the British commons, I hope to point out useful implications to global governance of today. Key words: common-pool resource management, CPR, governance, global governance, commons, British medieval commonfields, historical institutionalism. iii.

(5) Chinese Abstract (中文摘要) 埃莉諾.奧斯特羅姆(Elinor Ostrom)指出,針對集體行動來處理公共資源管理的第 三個途徑正是「社區」。此重要學術創建剛好貢獻全球治理由下而上之論述中的「民主 赤字」和「人類安全」之討論。近年來,世界各地發生現代圈地運動,造成了一股全球 性的農民反動。有趣的是,這些反動中所訴求的個人和社區層次之賦權卻非新鮮事。正 如奧斯特羅姆在他的研究案例中就已經展現了,個人層次的賦權正是工業革命前,農業 社會的運作模式─由某種社區共同決策的治理型態來處理日常之經濟行為,並且大多數 人都參與決策程序中。我選擇了蓋瑞.哈登(Garrett Hardin)比喻為「悲劇」的英國公有 地制度來當研究案例,提出本文的核心研究問題:英國中世紀公有地制度,作為一個歷. 治 政 史的案例和長期持續的制度,如何能成為社區治理,乃至於全球治理的借鏡?經案例分 大 立 析,我主張地方社區和個人應被賦予社會、經濟和政治上的權利與認可,以維繫他們賴 ‧ 國. 學. 以維生的地方制度。本研究顯示,當地方或國家政府決定不再給予權利和認可時,那些. ‧. 依賴該制度維生的人將終遭致悲劇。本文點出英國公有地制度的缺陷,並希望藉此用以. sit. y. Nat. 借鏡今日的全球治理。. io. n. al. er. 關鍵字:公共資源管理、治理、全球治理、公有地、英國中世紀公有地、歷史制度論. Ch. engchi. iv. i Un. v.

(6) Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................... I ENGLISH ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................ III CHINESE ABSTRACT (中文摘要) .................................................................................... IV CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 1.1 RESEARCH BACKGROUND AND RESEARCH QUESTION ...................................................... 1 1.2 RESEARCH APPROACH AND METHOD ................................................................................ 7. 政 治 大 ............................................................................................... 11 立. 1.3 RESEARCH STRUCTURE ..................................................................................................... 9 1.4 RESEARCH CONSTRAINTS. 1.5 USE OF TERMINOLOGY .................................................................................................... 12. ‧ 國. 學. CHAPTER II: HISTORICAL CASE STUDY—THE MEDIEVAL BRITISH. ‧. COMMONFIELDS................................................................................................................ 15. Nat. sit. y. 2.1 THE ORIGINAL “TRAGEDY” OF THE BRITISH COMMONS—A HISTORICAL. n. al. er. io. MISUNDERSTANDING ............................................................................................................ 15. i Un. v. 2.2 LITERATURE REVIEW ON THE MEDIEVAL BRITISH COMMONS AND COMMONFIELDS ....... 17. Ch. engchi. 2.2.1 The Initiation........................................................................................................... 19 2.2.2 The Daily Workings ................................................................................................. 23 2.2.3 The Collapse ........................................................................................................... 26 2.3 REGIONAL DIFFERENCES OF BRITISH COMMONFIELD SYSTEMS ...................................... 30 2.4 ARGUING A NEW CASE: THE REAL TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS .................................... 36 CHAPTER III: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE—HISTORICAL INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS ON THE BRITISH COMMONS ..................................................................... 41 3.1 LITERATURE REVIEW ON HISTORICAL INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS ................................... 41 3.2 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK OF EXPLAINING CONTINUITY AND CHANGE ............................. 50 v.

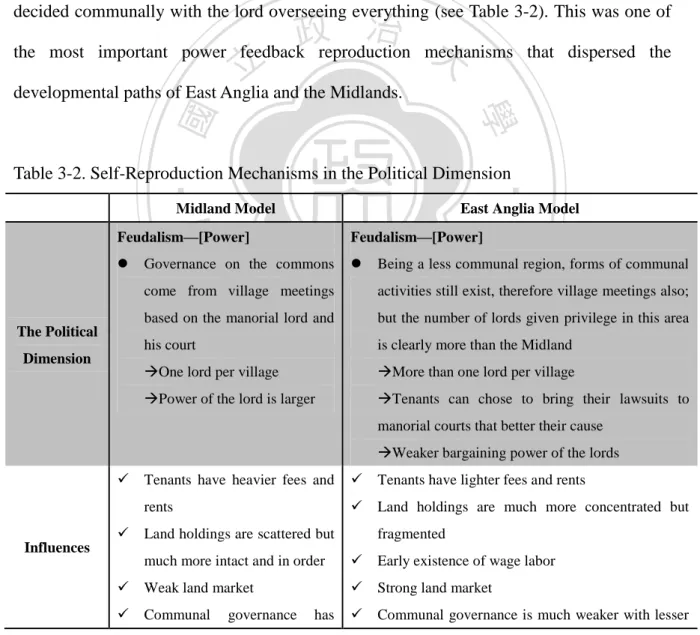

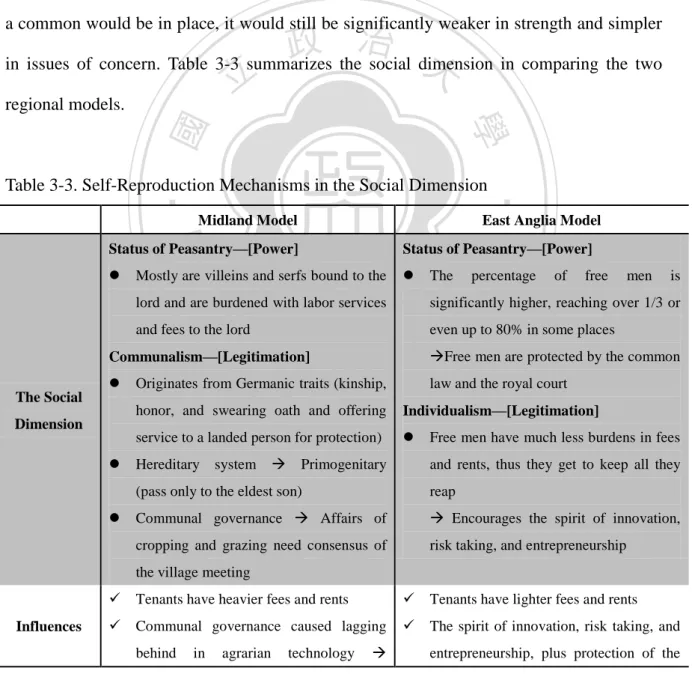

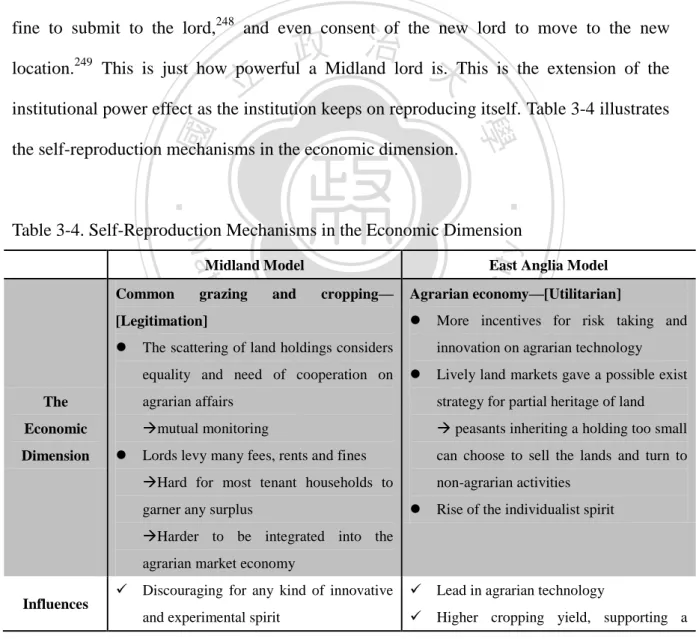

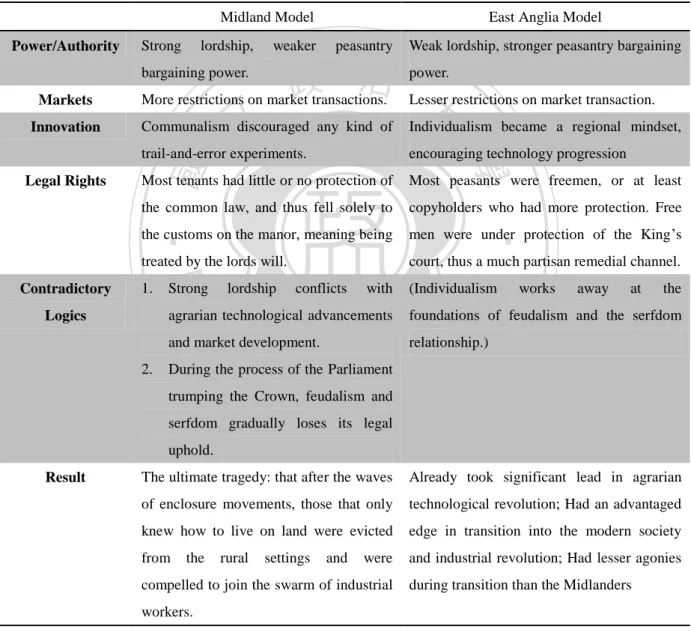

(7) 3.2.1 Self-reproduction Mechanisms ................................................................................ 50 3.2.2 Research Framework .............................................................................................. 55 3.3 ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................ 56 3.3.1 Identifying Factors of Continuity ............................................................................ 56 3.3.2 Identifying Factors of Change ................................................................................ 69 3.4 DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS ...................................................................................... 72 CHAPTER IV: THE BRITISH MEDIEVAL COMMONS AS A CPR INSTITUTION?75 4.1 LITERATURE ON COMMON-POOL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT (CPR) ................................ 75. 政 治 大 S F CPR ............................................ 79. 4.2 CHARACTERISTIC DISCREPANCIES OF THE BRITISH COMMONS AND CPR CASES ............ 78. 立. 4.3 HOW THE BRITISH COMMONS CAN. TILL IT IN WITH. ‧ 國. 學. 4.4 THEORIZING THE COLLAPSE OF THE BRITISH COMMONS FROM A CPR VIEWPOINT ......... 85 4.5 POLICY IMPLICATIONS ..................................................................................................... 90. ‧. CHAPTER V: BACK TO THE FUTURE—POLICY IMPLICATIONS TO THE 21ST. y. Nat. er. io. sit. CENTURY .............................................................................................................................. 92 5.1 PROBLEMS ON THE BRITISH COMMONS ........................................................................... 92. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. 5.2 COMPARING DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE MIDLAND AND EAST ANGLIA MODELS .......... 94. engchi. 5.3 POLICY IMPLICATIONS FROM THE CPR PERSPECTIVE TO GLOBAL GOVERNANCE TODAY 99 5.4 FURTHER RESEARCH SUGGESTIONS .............................................................................. 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 102. vi.

(8) Chapter I: Introduction. 1.1 Research Background and Research Question Global governance has become a major catchphrase of many researches and studies in international politics over the past decade. Given the realist conventional understanding in international relations—the anarchic characteristics of the international system, states are the only major actors, security of the state and its survival as the core objective of state actions—the emergence of global governance related studies posed a great challenge to. 政 治 大 phenomena that scholars and practitioners alike find new and interesting—retreat of the state, 立 existing theories.1 Since the 1990s, many factors have contributed to the rise of certain. ‧ 國. 學. weakened sovereignty, scores of new actors in the international arena, interdependence of interstate relations, globalization, and democratization.. ‧. With the end of the Cold War, fall of the Soviet Union, and democratization of East. Nat. sit. y. European and other countries around the world, the bi-polar power struggle has ceased to be. n. al. er. io. the simple structural background of the world. In the United Nations, more Security Council. i Un. v. backed peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention tasks have been passed, and economic. Ch. engchi. liberalist policies have become a major trend sweeping across national level policy implementation as well as in the supranational level organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In short, state sovereignty have been challenged reoccurringly and the old state-versus-market/ Keynesian-versus-Neoliberalism debate is hotter than ever.2 These changes gave way to many discussions about the role of the government and its function of governing. After finding widespread exceptions between what “ought to be” and 1. Deborah D. Avant, Martha Finnemore & Susan K. Sell. 2010. “Who Governs the Globe?” in Who Governs the Globe?, eds. Deborah D. Avant, Martha Finnemore & Susan K. Sell.( Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 2 2 Thomas G. Weiss, “Governance, Good Governance and Global Governance: Conceptual and Actual Challenges,” Third World Quarterly 21, no. 5 (2000): 795-814. 1.

(9) what actually “is”, the concept of “governance” appeared. The concept of governance at the state level, as defined by James Rosenau, is “not synonymous with government”. 3 It “encompasses the activities of governments, but also includes the many other channels through which ‘commands’ flow in the form of goals framed, directives issued, and policies pursued”. 4 It “also subsumes informal, non-governmental mechanisms whereby those persons and organizations within its purview more ahead, satisfy their needs, and fulfill their wants”.5 Thus, Rosenau clearly points out that governments do not necessarily govern, and the need for governance may be filled in by other actors, just like how he termed his edited volume Governance Without Government.. 治 政 Global governance, on the international level, is not 大an aggregate sum of sovereign 立 government actions put together. Two things stand out to be mentioned here. First, the types 6. ‧ 國. 學. of actors involved in “governance” are many. They include intergovernmental organizations international. non-governmental. organizations. (INGOs),. ‧. (IGOs),. and. transnational. sit. y. Nat. corporation (TNCs), as well as subnational actors such as local governments,. io. er. non-governmental organizations (NGOs), communities, and individuals. Sovereign states are no longer the sole player. Second, the notion of “good” governance has been edging towards. al. n. iv n C what can be called as more “human-centered” as compared to “state-centered” ones. h e n gfocuses, chi U. This notion includes “accountable, efficient, lawful, representative and transparent”,7 and thus enabling “the human development idea” of—“equality of opportunity, sustainability and empowerment of people”8 It also ties in with Rosenau’s observation that authority is in “bifurcation”—people give authority no longer according to “tradition”, but based on 3. James N. Rosenau, “Governance, Order and Change in World Politics,” in Governance Without Government: Order and Change in World Politics, eds. James N. Rosenau and Ernst-Otto Czempiel. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 4. 4 James N. Rosenau, “Governance in the Twenty-first Century,” Global Governance 1, no. 1 (1995), 14. 5 Rosenau, Change in World Politics, 4. 6 Peter Willets, Non-governmental Organizations in World Politics: The Construction of Global Governance. (London; New York : Routledge. 2011). 7 Thomas G. Weiss, “Governance, Good Governance and Global Governance: Conceptual and Actual Challenges,” Third World Quarterly 21, no. 5 (2000): 808. 8 Weiss, Conceptual and Actual Challenges, 807. 2.

(10) “performance”9 or “recognition”10 and not only the ability to “control”.11 Global governance is not global government: it is not top-down, not hierarchical, not coercive in nature; it is carried out by an array of actors on many levels in the form of formal and/or informal rules, norms, mechanisms, and activities; it is concerned with solving issues of collective action regarding public goods and services on multi-levels; it is an aggregation of cooperation from state government, intergovernmental authorities, the civil society, and the private sector.12 However, as good as it sounds, global governance is not without criticism. Issues of transparency, legitimacy, representation, participation, and democratic deficiency have. 治 政 constantly been brought up concerning intergovernmental 大 regimes. We find this apparent in 立 many issue areas like international trade at conferences of the World Trade Organization 13. ‧ 國. 學. (WTO),14 international and national finance at Group of 20 meetings,15 and especially in the. sit. y. Nat. Change (UNFCCC).16. ‧. global climate negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate. io. al. er. Moreover, we are witnessing a slowdown in the progress of multilateral intergovernmental/supranational level negotiations in the recent decade. WTO’s Doha round. n. iv n C has achieved no significant breakthroughs 2001. Right now bilateral and regional free h e since ngchi U 9. James N. Rosenau,. 1995. “Sovereignty in a Turbulent World.” In Beyond Westphalia? State Sovereignty and International Intervention, eds. Michael Mastanduno and Gene Lyons. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 191-227. 10 Avant, Finnemore & Sell, 2010. 11 See Stephen D. Krasner, 1999. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press). 12 Weiss, 2000; Willets, 2011; Margaret P. Karns and Karen A. Mingst. 2004. International Organizations: The Politics and Processes of Global Governance. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.. 13 Jan A. Scholte, 2002. “Civil Society and Democracy in Global Governance”, Global Governance 8 (3): 281-304; Fisher, Dana R., and Jessica Green. 2004. Understanding Disenfranchisement: Civil Society and Developing Countries’ Influence and Participation in Global Governance for Sustainable Development. Global Environmental Politics 4 (3): 65–84. 14 Michael Strange. 2011. “Discursivity of Global Governance: Vestiges of ‘Democracy’ in the World Trade Organization.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 36(3): 240-256. 15 Fen Osler Hampson and Paul Heinbecker. 2011. The "New" Multilateralism of the Twenty-First Century. Global Governance 17 (3):299-310. 16 Fisher and Green, 2004; Dana R. Fisher. 2010. “COP-15 in Copenhagen: How the Merging of Movements Left Civil Society Out in the Cold.” Global Environmental Politics 10 (2): 11-17. 3.

(11) trade agreements are filling in the gap. UNFCCC’s climate negotiations have been stuck in the post-Kyoto framework on binding-or-not emission reduction targets since 2007, and just postponed this job last year at COP18 until 2015. It is the European Union, individual states and local cities that are going ahead with real action. All in all, it seems that the top-bottom approach has met major setbacks on various pending contemporary issues. Seemingly, they might not clear up in the near future. Scholars have long supported some sort of bottom-up approach. Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink paved way for a difference pathway to look at non-state actors in the international arena, enabling more systematic analysis of the agency of transnational. 治 政 advocacy networks, and explaining how and why it works. 大 Dana Fisher and Jessica Green 立 hoped for a better participation of the civil society (and developing countries) in global 17. ‧ 國. 學. governance, thus they developed a model to explain and typify why certain groups are. ‧. weaker than other in policy influence. They believe that as long as these “disenfranchisement”. sit. y. Nat. exists, global governance for sustainable development will be limited.18 Thomas Weiss,. the. al. importance. n. emphasize. io. to. of. Ch. non-state,. er. Tatiana Carayannis, and Richard Jolly went even further to invent a “Third” United Nations non-secretariat(the. n engchi U. iv. “Second”. UN),. policy-influencing, professional individuals and experts from NGOs, think tanks, and the academia.19 Fisher, after the events of COP15 at Copenhagen, even criticized how the civil society was “left out in the cold” (2010).20 However, there are more radical genres in “bottom-up” approaches. In my own attendance of the UNFCCC 16th Conference of Parties (COP16) in Cancun, Mexico, I. 17. Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink. Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998. 18 Fisher and Green, 2004. 19 Thomas G. Weiss, Tatiana Carayannis, and Richard Jolly. 2009. “The ‘Third’ United Nations.” Global Governance, Vol., 15, No. 1, pp. 123-142; on the “First” UN, see Inis L. Claude Jr., "Peace and Security: Prospective Roles for the Two United Nations", Global Governance, Vol. 2, No. 3 (1996), pp. 289-298. 20 Fisher pointed reasons due to over registration, poor conference planning and a paradox of civil society conference “outsiders”, the radical protestors, causing conference “insiders”, the pacifists, unable to participate in the conference. Therefore, it wasn’t exactly fault on the governments’ side. 4.

(12) witnessed a gathering of the famous transnational grass-root social movement called “La Via Campesina”. La Via Campesina is consisted of small to middle-sized farmers, poor peasants, rural women, and indigenous communities from America, Africa, Asia, and Europe seriously concerned about their farming rights, community rights, and food sovereignty being attacked by the local/national governments and/or corporate interests. They “defend small-scale sustainable agriculture as a way to promote social justice” and “strongly oppose corporate driven agriculture and transnational companies that are destroying people and nature”.21 They view all solutions brought up by UNFCCC as fraudulent and false promises. They only believe in the people and people’s solutions to their collective action and public goods. 治 政 problems. The approaches mentioned before talk about how 大 actors in the civil society can 立 influence policy making with the authorities. But this approach hopes to reclaim the authority ‧ 國. 學. in its own affairs and make its own decisions.. ‧. Interestingly enough, this community’s/people’s view has academicals support with. sit. y. Nat. empirical evidence. Elinor Ostrom (1990) and her colleagues studied common-pool resource. io. al. er. (CPR) management for years, and found that many community-based CPR institutions have. n. successfully managed their common goods for over centuries.. Ch. n engchi U. iv. 22. Moreover, this. community-based, bottom-up approach has been nothing new historically. The English medieval commonfield systems serve as interesting examples. The English medieval commonfield was made famous by Garrett Hardin’s 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons”. In the article, he leads the reader to “picture a pasture open to all”.23 In the economic sense of marginal utility of gains, it is in fact a good bargain to keep on adding to one’s own herd. Therefore, when all herdsmen act freely on self-interest, it 21. La Via Campesina. 2011. “The International Peasant's Voice.” In http://viacampesina.org/en/index.php/organisation-mainmenu-44.posted. Last updated 09 February 2011. 22 Elinor Ostrom, 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York, NY.: Cambridge University Press. 23 Garrett Hardin. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Science, Vol. 162: 1243-1248. Reprinted in Managing the Commons 2nd ed. eds., John A. Baden and Douglas S. Noonan. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1998), pp. 3-16. The pages mentioned in this paper are all from this print and not the 1968 original print. 5.

(13) causes overgrazing and thus the tragedy: “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”.24 However, Susan Jane Buck Cox argued that the tragic logic proposed by Hardin never did happen in history.25 Not only did it not happen, the British commonfields actually operated for hundreds of years. Hence, Buck suggests that the communal courts of medieval England manors could be a “remedy” to the “ruins” of commons governance of today. 26 More scholarly works build into the conventional wisdom of the British commons. Barrington Moore in his famous book “Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy” argued that due to the enclosure movements, the peasantry class in Britain was effectively dissolved, thus contributing to the development of democracy in England. The process of the. 治 政 enclosure movements and start of the industrial revolution大 was also linked by Douglass North 立 and Robert Thomas in their book “The Rise of the Western World”—that the release of ‧ 國. 學. abundant and cheap labor from the countryside caused by the enclosure movements was a. ‧. great contributing factor to the transformation of production during the “revolution”. What. sit. y. Nat. became of the lives of the mass proletariats was vividly depicted by social critics and writers. io. al. er. alike, like Charles Dicken in his famous series “The Christmas Carol”. Interesting enough, three similarities of enclosure movements during the late medieval. n. iv n C to early modern periods and that of today loud to me: (1) there is plain peasantry agony h ering ngchi U and disillusion towards the governance structure, local, national and even intergovernmental alike; (2) we find strong structural constraints at work with the victims suffering greatly from weak agency and bearing great despair; (3) we find many a failure in the original governing/institutional design, in which if they were better designed in the first place may lessen or even avoid the horrendous situations of the affected people originally depending. 24. Hardin. 1968. Susan Jane Buck Cox, 1985. “No tragedy on the commons.” Environmental Ethics, Vol. 7 (Spring): 49-61. In the rest of the paper, I will mention Susan Jane Buck Cox as “Buck” due to the fact that in later publications she dropped “Cox” and used only “Buck”. See Buck’s affiliations page at http://www.uncg.edu/psc/FacultyVita/Buck%202012.pdf. 26 Buck, 1985, p. 61. 6 25.

(14) their livelihoods on these institutions that went wrong. It is from personal experiences and academic encounters of class readings that I finally came to this research question. I share Buck’s take at the commons and ask the overall question of this paper: What light can historical long-enduring institutions shed on community-based institutions and even global governance today? In other words, what can be done to alleviate the agony in the impacted communities? What was the cause of the agony? What can be done to change it? For empirical evidence, I introduce my historical case for reference: the case made famous by Garret Hardin—The Tragedy of the Commons.27 I argue that not only was the. 治 政 British commons not a “tragedy”, but had lasted for centuries, 大 and largely fits in with the 8 立 long-enduring CPR principles that Ostrom derived from her research of many case studies. I ‧ 國. 學. support this point by analyzing both internal and external factors contributing to continuity. ‧. and change of the British commonfield systems using historical institutional analysis.. y. Nat. Moreover, I also argue that the fall of the British commons was not an “inevitable” result. er. io. sit. of the enclosure movement and industrialization,28 but infringement of certain foundational. al. principles for the CPR to work self-sustainably. Examining the fall of a once successful. n. iv n C community-based institution can bring h forth lessons for today’s e n g c h i U governance in the subnational level, and even for global governance itself.. 1.2 Research Approach and Method My research will basically conduct via literature analysis and case study comparison. Literature materials are mostly second-hand (or more) information due to the nature of my case selection and availability of literature here in Taiwan. The approach to support my research question will be historical institutionalism.. 27 28. Hardin. 1968. Buck, 1985. 7.

(15) Historical institutionalism is one of the schools of New Institutionalism. Historical institutionalists tend to see institutions as historical legacies of past conflicts and constellations that are dynamic and changes temporally. They see institutions as embodying constraints that restrict individual decision from a “macro-process” perspective. Historical institutionalists tend to be more willing to embrace the concept of path-dependency, but are torn between debates of evolutionary (incremental) and revolutionary (punctuated) change.29 Further explanations with be given in Chapter 3.1. This brings a question in order: Why choose historical institutionalism? First, because the British commonfield system is an institution embedded against a web of intermixed. 治 政 political, economic, and social contexts, and embodying 大 various groups of actors and 立 individuals mixed and matched with various causal relationships. Hence, historical ‧ 國. 學. institutionalism lends many insights to such a complex research issue.. ‧. Second, the emphasis on longer stretches of time and time sequence is one of the grand. sit. y. Nat. traditions in social sciences, for “[c]ausal analysis is inherently sequence analysis”.30 From. io. al. er. Marx and Weber to Polanyi and Schumpeter, these giants adopted historical approaches, lending them an acute view to their observation on how the social world is. For Pierson,. n. iv n C “[a]ttentiveness to issues of temporality aspects of social life that are essentially h ehighlights ngchi U invisible from an ahistorical vantage point”; “Placing politics in time can greatly enrich our. understanding of complex social dynamics”.31 For an institution that has been in operation for several centuries, an approach that takes vast periods of time seriously is in order.32. 29. John L. Campbell, Institutional Change and Globalization (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 27. 30 Rueschemeyer D., Stephens E.H., Stephens J.D., Capitalist Development and Democracy (Chichago: University Chicago Press, 1992), p. 4. 31 Paul Pierson , Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 2. 32 Also considering the “laggard” characteristic of events and their potential influences, that the influences are not instantly felt and seen but become more visible after a length of time. See James Mahoney and Daniel Schensul, “Historical Context and Path Dependence”, in Robert E. Goodin and Charles Tilly eds., The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis (Oxford, England ; New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 457. 8.

(16) Third, that historical institutionalism is a better encompassing approach to integrate the other two approaches, simply accepting parts of the behavior assumptions of the rational-choice approach (the “logic of instrumentality/ consequence”) with restrictions and acknowledging influence of social scripts, cognitive constraints, and social legitimacy to individual actions (the “logic of appropriateness”) under a “choice-within-constraint” path dependent approach.33 Hall and Taylor seemed to support a similar view in arguing that historical institutionalism embodies both the “calculus approach” and the “cultural approach”;34 and Ikenberry seemed to appreciate that historical institutionalism can strike a balance between the “rationalist” approach being “too thin” (too much agency) and the. 治 政 “constructivist” approach being “too thick” (not enough大 agency). I understand that this 立 view is not without debate, but this is not the focus of this paper, therefore I will leave this at 35. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. that.. sit. y. Nat. 1.3 Research Structure. io. al. er. As mentioned, my research question is “What light can the British medieval commonfields, as a historical long-enduring institution, shed on community-based. n. iv n C institutions and even global governance h today?” i U structure is illustrated in Table e n g cMyhresearch 1-1 below. My independent variable is the institutional designs of two different regional models of the British commonfields. My dependent variable is the general livelihoods of the peasantry in the region. There are many factors that account into explaining the general. livelihood outcome, which will be the main focus in Chapter 3. In Chapter 4, I utilize Ostrom’s common-pool resource management literature to make sense of how the. 33. Peter A. Hall, and Rosemary C. R. Taylor, “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms”, Political Studies, Vol. XLIV (1996), pp. 936-957. 34 Hall and Taylor, 1996, p. 939; Peter A. Hall and Rosemary C. R. Taylor, “The Potential of Historical Institutionalism: A Response to Han and Wincott”, Political Studies, Vol. 46 (1998), pp. 958-962. 35 G. J. Ikenberry. 1994. History’s Heavy Hand: Institutions and the Politics of the State. Paper presented at conference on The New Institutionalism, University of Maryland, Oct. 14-15, pp. 5-6. 9.

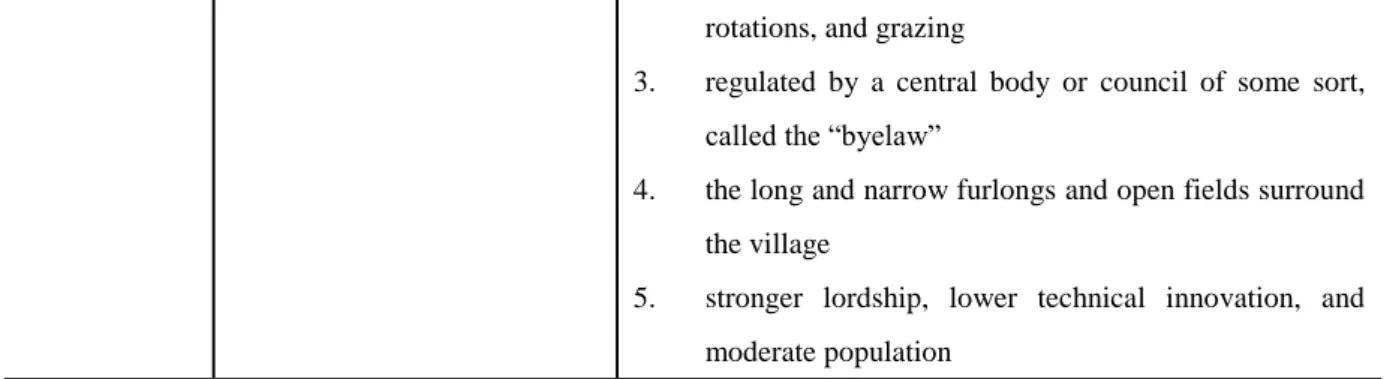

(17) institutional design is flawed and should be changed. That is where I draw lessons and implications to modern day global governance.. Table 1-1. Research Structure Independent. Intervening Variables. Dependent. Variable. Variable. Institutional. Self-reproduction mechanisms. General livelihood. designs. ˙. Power explanation: Manorial lordship power versus Tenant. outcomes. bargaining power; Extent of legal protection of rights and. peasants. of. liberties ˙. Utilitarian explanation: Lively agrarian markets and land. 政 治 大 explanation: Communalism. markets; Incentive for risk taking. 立 Individualism; development of agrarian technology. 學. Critical Junctures Magna Carta of 1215. ˙. Civil Wars and 1688 Glory Revolution. Initial Conditions. er. io. sit. Nat. Presentations of lords in a village. ‧. ˙. ˙. versus. y. Legitimation. ‧ 國. ˙. al. Below, I provide an overview of this paper. In Chapter One, I will introduce the research. n. iv n C question, research framework, and research I point out that calls for trusting the h e nmethods. gchi U people and taking a bottom-up approach is nothing new, both historically and academically. I will also mention my research constraints and define the use of terminology. In Chapter Two, I introduce the historical case study of the medieval British commons and commonfield systems, discuss the misunderstandings of the British commons in conventional wisdom, and explain the initiation, the daily operations, and collapse of the British medieval commons. The center question unique to this chapter is “Was the British commons a “tragedy” or “triumph”? Retracing historical facts from historians and relevant records, I redraw the image of the so called champion model of the British medieval 10.

(18) commonfields, compare regional differences of the commonfield systems, and argue a new case: that peasants who lived on the commonfield systems suffered the most when the institution collapsed, hence, the “real” tragedy of the commons therein. In Chapter Three, I review the historical institutional analysis literature, and apply it to analyze the British commonfields system by identifying its factors contributing to continuity (hence its success as seen by some scholars,) and change. The core questions in this chapter are “What caused the commonfields institution to reinforce itself?” “What caused it to break down?” Drawing on the idea that positive feedback loops contribute to institutional reproduction mechanisms to explain change and negative feedback to disrupt reproduction. 治 政 and thus implying change, I analyze the historical case and大 briefly discuss the implications. 立 In Chapter Four, I review the CPR literature and Ostrom’s eight long-enduring CPR ‧ 國. 學. principles, point out the discrepancies of how the historical “commons” differ from the. ‧. theoretical “commons” in CPR literature, and examine how the British commonfield system. sit. y. Nat. can still fit with Ostrom’s principles. Finally, I explain, in light of CPR literature, how the fall. io. er. of the British commonfield system was not an inevitable turn of events, but sophisticatedly. al. intertwined with the socio-economic context—external forces, as well as internal factors,. n. iv n C impeded the eight principles—resultedhin the collapse ofUthe commonfield system. I support engchi these analyzes with findings from chapter 3. In Chatper Five, I discuss the implications of this historical case to modern cases of community-based institutions, attempt a dialogue with current literature and theories, point out how the British medieval commonfields can be a lesson to local as well as global governance in the 21st century, and derive my policy implications with conclusions and further research directions.. 1.4 Research Constraints The main constraint to my research is the availability of the British medieval 11.

(19) commonfield systems literature. The literature on the British commons is itself not complete due to three main of reasons: First, is that the literature is still in the process of construction and discovery. Records of this centuries-old institution were kept with punctuation due to many reasons, including the impact of the Black Death in 1349-50, decline of the population, fires and break-out of wars. The second reason was that it wasn’t until recent years that the British decided to start to rediscover their own historical institutions because they suddenly realized that so little was left of it to study and trace. Therefore, in the endeavor hoping to unveil the causal reasons or enabling conditions of the rise, triumph, and fall of the British commons, I do hope to dig up. 治 政 as much literature as possible while acknowledging the 大 limitation of available data as just 立 explained. ‧ 國. 學. A third reason is the availability of first hand historical data is largely limited here in. sit er. io. 1.5 Use of Terminology. y. Nat. by other scholars.. ‧. Taiwan. Without needed funds, I cannot but rely mainly on second-hand research published. al. n. iv n C Hardin’s use of “the commons” was restricted, which I will get back to shortly. h enarrowly ngchi U. Before I go on, I should bring attention to the use of terminology of “commons”. The discussions of “commons” in this paper are focused on the historical socio-economic agrarian arrangements in medieval and post-medieval England and not the concept of “commons” or “public goods” in economy. Now let me explain the “historical” commons more clearly. The British common fields system is basically a pre-industrial-revolution English socio-economic arrangement. It was the only way to make a living for most of the population in medieval England. Peasants are bound to manorial lands with service duties as serfs or villeins. The common fields system was the comprehensive arrangement of cropping, grazing, and gathering activities. The village is nucleus in appearance, meaning that all the buildings 12.

(20) and houses are built together, usually surrounding the village church, and all the fields surround the village. Land usage in this arrangement is differed by the physical environment, functions, and rights of usage. These include arable fields, commons proper (rough grazing land, marshlands, woodlands, and wastelands), and the demense (land which agrarian production goes to the manorial lord or the King, but worked by tenants who owe service of 2-3 days work a week to the lord or King). My usage of the commons is broader than Hardin’s use of the “common meadow” and “grazing grass” as the resource unit in concern. It basically includes the whole common field system as a socio-economic arrangement in which the “common meadow” is embedded. 治 政 within. My reason is that since “the commons” arrangement 大 could not exist without the 立 socio-economic context of the common field system, including the manorial lord, the ‧ 國. 學. manorial court, the village council, the open arable fields, the way of cropping, grazing, and. ‧. gathering…etc. All this fall upon a central theme and core resource unit: the land. The rights,. io. er. viewing the British common fields as a CPR institution.. sit. y. Nat. rules, and regulations are concern the use of land. This is the exact focus of this study:. In sum, “the commons” can be used as only mentioning the “common land” or. al. n. iv n C “common meadow”, as Hardin used it h in its “grazing” rights e n g c h i U and function (see Chapter 2.1 on. this). It can also be a shortened synonym of the broader “common field system” as I have intended to use, but just to immunize the confusion, I will keep on using “common field system” throughout this paper as much as possible. The difference of definition is essential to keep in mind and hopefully not be confused about. Another more important note is that the commons in the historical context is quite different than that in current theory or conventional wisdom. Ostrom’s and others scholars’ literature on “common-pool resource management (CPR)” is actually an extension of Hardin’s misunderstanding or misuse of parody (see Chapter 2.1 for more). Hardin later admitted that what he regretted using the “commons” to illustrate his concept. He said that he 13.

(21) should have coined the title “The Tragedy of the ‘Unmanaged’ Commons”.36 The wide known theoretical understanding of “the commons”, or CPR, is that the resource system has “open access” or not have “exclusion/excludability”, meaning hard to exclude other users, and has “substractability” of resource units, meaning that a person using the resource would diminish the availability of the resource for another person. 37 This historical British commons does not adhere to the first characteristic of “open access”, as Hardin himself later noted. That being said, I did intend to allude to the “misuse” understanding of “the commons” in my thesis title on purpose. In the following chapter, I will introduce the original tragedy that Hardin made known to. 治 政 the world, and its historically based evidence. 大 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. 36. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. From Hardin’s personal communication with John A. Baden on 5 October, 1994. See John A. Baden, “Preface: Overcoming the Tragedy” in John A. Baden and Douglas S. Noonan eds., Managing the Commons, 2nd Ed. Bloomington, Indiana, US: Indiana University Press, p. xvii; see also, Hardin’s own article in 1994: Garrett Hardin, 1994. “The Tragedy of the Unmanaged Commons”, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Vol. 9, No. 5, p. 199. 37 Ostrom, 1990, p. 32; Elinor Ostrom, Roy Gardner, and James Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, and Common-pool Resources. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, p. 6-7; Susan J. Buck. 1998. The Global Commons: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, pp. 4-5; David Feeny, Fikret Berkes, Bonnie J. McCay, and James M. Acheson. 1990. "The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty-Two Years Later", Human Ecology, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 3-4. 14.

(22) Chapter II: Historical Case Study—The Medieval British Commonfields. 2.1 The Original “Tragedy” of the British Commons—A Historical Misunderstanding In this section, which I need to stress, I do not tend to challenge the theoretical contributions of “The Tragedy of the Commons”—illustrating the problem of collective action in which individual interests conflicts with collective interests will deductively cause ruin to all. Here, I only wish to point out that the use of such a parody was historically inappropriate.. 政 治 大. In Hardin’s 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Hardin first credits William. 立. Foster Llyod’s 1832 publication—Two Lectures on the Checks to Population—for providing. ‧ 國. 學. inspiration of the commons concept.38 Hardin, then, leads the reader to “picture a pasture open to all”.39 In this “pasture” parable, he did not clearly mention a specific context, place. ‧. or history.40 The reason he mentioned this was to give an example to illustrate the danger of. y. Nat. sit. no control on the growth of population. As his argument goes, “[a]s a rational being, each. n. al. er. io. herdsman seeks to maximize his gain…This utility has one negative and one positive. i Un. v. component”: the positive utility is near +1, but the negative is only a fraction of -1.41 In the. Ch. engchi. economic sense of marginal utility of gains, it is in fact a good bargain to keep on adding to one’s own herd. However, when all herdsmen act freely on self-interest, it causes overgrazing and thus the tragedy: “…the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd. And another; and another… But this is the conclusion reached by each and every rational herdsman sharing a commons. Therein is the tragedy. Each man is 38. Hardin, 1968, p. 6. Hardin put the date as “1833”, but in footnote 7 in Buck, she put the date as 1832 as it was republished in Garrett Hardin and John Baden, ed., Managing the Commons (San Francisco: Freeman, 1977). See Buck, 1985, p. 51, footnote 7. 39 Hardin, 1968, p. 6. 40 Buck, 1985, p. 51. 41 Hardin, 1968, p. 7. 15.

(23) locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”42. In the 1985 article by Susan Jane Buck Cox, “No Tragedy on the Commons”, she tried to point out the misconception and misuse of the original medieval British field-system concept made famous by Hardin. Her main argument was that the “tragedy” from the “inherent logic of the commons” in which “each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain” as Hardin illustrated never did resolve in the consequence of overgrazing. 43 In medieval. 治 政 England, manorial courts of village communities, where 大 the chief lord and all the villagers 立 were represented, regulated the common rules of cropping and grazing of the fields.. 44. ‧ 國. 學. Therefore, overgrazing caused by the egoistic behavior of the “economic man” would not. ‧. have happened. Hence, Buck suggests that the all-inclusive communal courts of medieval. y. sit. io. er. Buck puts it:. Nat. England manors could be a “remedy” to the “ruins” of commons governance of today.45 As. “Perhaps what existed in fact was not a “tragedy of the commons” but rather a. al. n. iv n C triumph: that for hundreds of years—and perhaps thousands, although written records do heng chi U not exist to prove the longer era—land was managed successfully by communities.”46. When concluding at the end of her article, Buck views the British medieval commons as quiet a success as a long-lived institution. This raises questions for the researcher: How were the common fields managed over the long period of time? How did it manage to last for so long? How was it successful to be considered a “triumph”? Why was it a historically inappropriate parody (not a “tragedy”)? And what really caused its demise? I devote the rest 42 43 44 45 46. Hardin, “The Tragedy”, 7. Buck, 1985, p. 51. Buck 1985. Buck 1985, p. 61. Buck 1985, p. 60. 16.

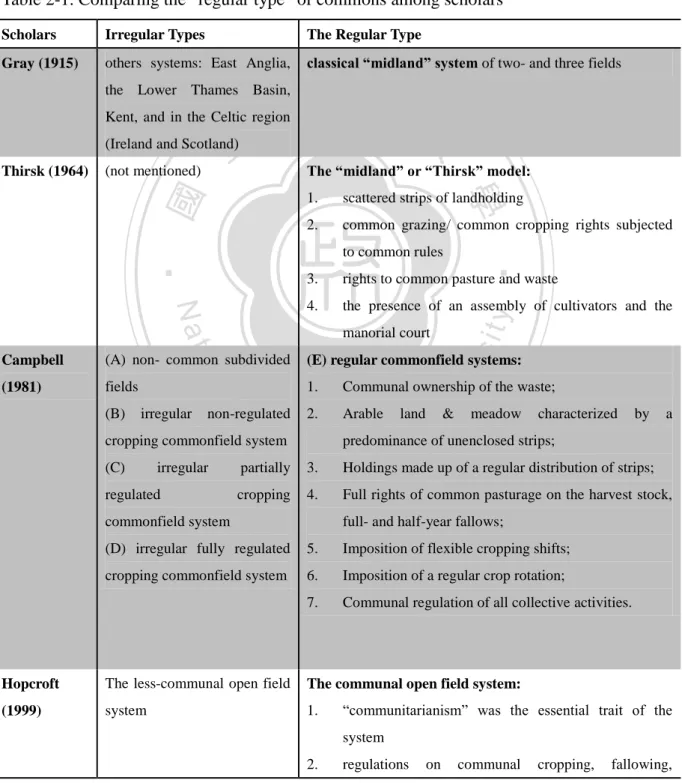

(24) of this chapter to deal with the questions above.. 2.2 Literature Review on the Medieval British Commons and Commonfields The study of the medieval and post-medieval English commons has been slow. It wasn’t until about a century ago when scholars realized that there was not only one field system, but various “systems”.47 In 1915, it was Howard Levi Gray who published his classical work English Field Systems that marked a beacon in the contemporary English common-fields literature.48 Gray made an important contribution to the literature and the understanding of the. 治 政 commons system in manifolds: (1) identifying the plurality 大 English field systems; (2) 立 distinguishing other separate systems in East Anglia, the Lower Thames Basin, Kent, and ‧ 國. 學. in the Celtic region (Ireland and Scotland) from the classical “midland” system of two- and. ‧. three fields; 49 (3) proposing two main factors as cause of the variations between. sit. y. Nat. systems—ethnic settlement as primary, and the physical environment as secondary. 50. io. er. While the first two has been largely accepted, confirmed and expanded by other scholars, the third on reasons causing system variation is still under debate.51. n. al. 47. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Howard Levi Gray, English Field Systems (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1915); Alan R. H. Baker, “Howard Levi Gray and English Field Systems: An Evaluation”, Agricultural History 39, no. 2 (April 1965):87. 48 Alan R. H. Baker , “Howard Levi Gray and English Field Systems: An Evaluation.” Agricultural History , Vol. 39, No. 2 (April, 1965), pp. 86-91.; Bruce M. S. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins—the Regional Dimension”, in The Origins of Open Field Agriculture, ed. T. Rowley (London: Croom Helm, 1981), pp. 112-113; B. K. Roberts, “Field Systems of the West Midlands”, in Studies of Field Systems in the British Isles, ed. Alan R. H. Baker and Robert A. Butlin (Cambridge, England: University Press, 1973), 188-190; Joan Thirsk, 1967. “Preface to the Third Edition.” In C. S. Orwin and C. S. Orwin eds., The Open Fields (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), p. vi. 49 The “two- and three field system” meant total sectors of land-use rotation: two-field system meant two fields in rotation and 1/2 would be left fallow each year, meaning leaving the land to rest and not produce any crop; three-field system meant three in rotation and 1/3 stood fallow each year. However, it was later discovered that the rotation may not have followed in units of “fields”, but smaller units consisting of “strips” call the “furlong”. This implied that a two-field system could adopt a three-course rotation. See Rosemary L. Hopcroft, 1999. Regions, Institutions, and Agrarian Change in European History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 16-17; Alan R. H. Baker and Robert A. Butlin, “Conclusion: Problems and Perspectives”, in Baker and Butlin, Studies of Field Systems, p. 622. 50 Baker, “An Evaluation”, 87; Baker and Butlin, “Conclusion”, 624-625; Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112. 51 Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112-113, 118-129; Hopcroft, Regions, pp. 28-41; Baker and Butlin, “Conclusion”, pp. 627-656. 17.

(25) Thirsk, in her 1964 article “The Common Fields”, defined the “classic model”52 or the “midland model” 53 of the common field system in four essential characters: (1) scattered strips of landholding for each cultivator, implying a sharing of both good and bad lands; (2) common grazing of animals and common cropping on arable fields and meadows are subjected to common rules of cultivation, organized into systems of two- or three-field systems; (3) cultivators enjoy rights to common pasture and waste (unused land) for grazing of stock and gathering of timber, peat, and other commodities; (4) the presence of an assembly of cultivators, embodying disciplinary powers, oversees the working of the system—the manorial court, or when involving more than one manor in a township, a village meeting.. 治 政 However, as Thirsk notes herself, not大 all characters may exist at the 立 學. ‧ 國. same time.55. 54. Campbell, in a 1981 article titled “Commonfield Origins—the Regional Dimension”,. ‧. made a more detailed refinement of commonfield elements into 14 attributes and. sit. y. Nat. categorized the common fields into 5 main categories according to the consisting attributes.. io. al. er. Campbell’s finding, in short, was that the structure of the lordship and its will makes a huge difference on the commonfield systems: strong lordship was associated with the. n. iv n C regular commonfield system, lower technical and moderate population; weaker h e ninnovation, gchi U lordship was associated with the irregular commonfield systems, higher technical innovations, and populations to the two extremes.56 The original commons, extracted from British pre-industrialization society, according to 52. “Classic” in the sense of the two- or three-field systems understood even before Gray’s 1915 work. In view of the past hundred-year literature on the common field system study, it is safe to say that all the literature were aimed at identifying the original “norm”—the classical or midland model—and other alternative models that existed: characteristics of variation(what and how), boundaries of variation(where), and most importantly, what caused the difference(why)? 53 Campbell labeled Thirsk’s definition the Midland system the “Thirsk model”. See Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112. 54 Joan Thirsk, “The Common Fields”, Past & Present, no. 29 (December 1964): 3; Hopcroft, Regions, 20 55 Thirsk, “Common Fields”, 4. It should be reasonable to conjuncture here, that when Hardin wrote his influential article, the “commons” he had in mind when writing was approximated to this model—the most widespread understanding of the common field system. 56 Campbell, “Commonfield Origins” 128-129. 18.

(26) Buck, did not meet its doom due to individual excessive exploitation caused by the paradox of collective action, (and thereby creating the “tragedy”) but ceased to remain a functional “social institution” after the industrial revolution and the huge social change it incurred.57 The communal commons held on to function at large, before industrialization, because community councils, consisting of all the stakeholders who possess right to use the commons, were established to govern the collective use of both cropping, grazing, and other communal activities. The four observations of Thirsk apply here fully. Being in a pre-industrialized society with pre-modern bureaucracies in the Weberian sense, the common field system, governed by “shared norms and rules” of a community council with no modern sovereign. 治 政 state entity at the middle, survived many centuries. 大 In this sense, the commons was 立 considered a success by Buck. 58. ‧ 國. 學. Below, I will go into a little deeper into the historical context of this communal. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.2.1 The Initiation. ‧. socio-economic institution by reviewing its initiation, its daily working, and final collapse.. The rise of the British commonfields is still being debated.59 While the reasons of. al. n. iv n C initiation of the institution or how thehsystem took on its e n g c h i Uphysical looks are varied, several. historical facts are clear. After the Norman Conquest of the England in 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, or William the Conqueror, granted titles and knighthoods to a few thousands, and with it, the honors to lands. These lands, as documented in the earliest census—the Domesday Book—in 1086,60 were pretty much matching to mostly all arable lands know today. This implies that the peoples working these lands before the Conquest knew pretty 57. Buck, 1985, pp. 58-60. Buck, 1985, p. 60. 59 Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112-113, 118-129; Hopcroft, Regions, 28-41; Baker and Butlin, “Conclusion” 627-656. 60 The Domesday Book is a “far-reaching census” ordered by William the Conquer in 1086 aimed at recording lands, resources, tenures and people in England at the time. The results were later compiled into a volume known as the “Domesday Book”. In short, it was the best snapshot a historian could wish for at the time. See Amt (2001): 74. 19 58.

(27) much what they were doing. Some documents even imply that the commonfield system could be traced up to the eighth century. However, due to the fact that time is harsh on these historical evidences, what we know today is still limited. Here, I try to put some of it back together for us to have a better glance and understanding. As mentioned afore, Gray made three contributions to this field. Two of them concern our discussion here: the identification of plurality in the English field systems and the proposition of two main factors as cause of the variations between systems—ethnic settlement as primary, and the physical environment as secondary.61 Hopcorft, in her book, supported Gray’s ethnic explanation. Arguing in light of a. 治 政 “path dependency” explanation and considering high transactions costs once a whole 大 立 socio-economic system would incur if changed halfway, Hopcroft proposes a possible 62. ‧ 國. 學. interpretation: evidence suggests that “wherever certain Germanic groups settled in large. ‧. numbers, communal open fields systems later emerged. This suggests that they imported. sit. y. Nat. into those regions the cultural precursors of the communal system.”63 This is not to say. io. al. er. that the systems were brought in “full-fledged”, but evolved according to the new. n. environment through time. Having done extensive research in England, the Netherlands,. i n France, German lands, and Sweden,C Hopcroft postulates: U hengchi. v. “It is quite possible that they may have taken a particular regular form in parts of northern Europe, We may surmise that both familial and community organizations were strong in the face of severities of winter in the inland areas of northwestern Europe. In turn, strong village communities may have worked to maintain the regular nature of and division and inheritance rules, assuming that they operated on democratic or both democratic and hierarchical principles. We then can imagine that groups maintained these customs when they. 61. Baker, “An Evaluation”, 87; Baker and Butlin, “Conclusion”, 624-625; Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112. 62 Hopcroft, Regions, 35-36, 38-41, 46-51. 63 Hopcroft, Regions, 40. 20.

(28) migrated to other regions and that these customs later facilitated the emergence of communal open field systems across the plains of Europe.”64. C. S. Orwin and C. S. Orwin detested against Gray’s plurality argument, and believed that “wherever you find evidence of open-field farming and at whatever date, it is sufficient to assume that you have got the three-field system at one stage or another”65. They assumed that practical cooperation and collaboration was a sensible method of insuring survival in primitive conditions when the pioneer farmers arrived in the newly settled lands.66 Due to the fact that “the animals, men, and the equipment needed for to make an effective plough-team were beyond the resources of individual peasants”, 67. 治 政 pioneer families had to cooperate. In short, the Orwins believed 大 that the open fields system 立 was a result due to necessity of survival and limited resources, and the physical look took ‧ 國. 學. as such since the beginning.. ‧. However, Thirsk, coining the four core elements of the midland/champion model, sees. sit. y. Nat. the contrary. She notes that the system may not have taken such a look from the start, but a. io. er. natural development of many factors; not all characters existed at the same time: “The oldest element in the system is in all probability the right of common grazing over. al. n. iv n C pasture and waste. It is the residue of more extensive rights which were enjoyed from time he ngchi U. immemorial, which the Anglo-Saxon and later Norman kings and manorial lords curtailed, but could not altogether deny. By the sixteenth century we are familiar with commons that were enjoyed by one township alone.”68. Thirsk believed that the common rights and regulations, along with the subdivided fields, came from the impetus of population growth: it created the need to regularize land 64. Hopcroft, Regions, 40-41. Orwin and Orwin, Open Fields, 127. 66 Baker and Butlin, “Conclusion”, 625. 67 Ibid., 626. 68 Thirsk, “Common Fields”, 4. It should be reasonable to conjuncture here, that when Hardin wrote his influential article, the “commons” he had in mind when writing was approximated to this model—the most widespread understanding of the common field system. 21 65.

(29) holdings and layout, to ensure even access to water, and to protect the crops from beasts; communal rotation was introduced to rationalize the disposition of fallow lands, and communal grazing rights were established on the fallow strips. 69 The partition and subdivision of landholding into many parcels and strips, seen by Thirsk, was the result of partition among heirs from inheritance through generations, and the pressure of increased population as afore mentioned. All this proceeded in gradual stages in time. Summarized later by Bruce Campbell, Thirsk views the classical midland model representing “the ultimate stage in a long process of evolution, other English fields systems reflecting the effects of local and regional peculiarities of environment, settlement history, population. 治 政 density, and agrarian economy, upon the evolutionary process.” 大 立 However, Campbell disagrees with Thirsk’s theory of commonfield evolvement. First, 70. ‧ 國. 學. Campbell believes that under increasing population, large changes like redrawing layouts. ‧. of land and communal rotation would cause huge risks of low or no yields at all for farmer. sit. y. Nat. families. In a context of communal regulations and village consensus with an increasing. io. al. er. number of affected parties, changes, such as proposed by Thirsk, would have been faced with immense resistance and would not have likely come from the organized peasant. n. iv n C societies. Hence, a higher authority (such Parliament acting upon enclosure) would h easnthe gchi U. be needed to carry out such a reconstruction of socio-economic arrangements. 71 Additionally, if pressure from population increased, technical innovations to agricultural methods would have been more responsive to increased demands than the rearrangements of land usage. However, just as shown above, a regular commonfield system would also be slow in adopting or experimenting new agriculture technologies due to the communal consensus character.72. 69 70 71 72. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”,115, 118. Exerted from Campbell, “Commonfield Origins”, 112. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins” 119-120. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins” 120-122. 22.

(30) A third point would be that “[i]nnovations such as substitution for fodder crops for bare fallows, flexible rotations, and the stall-feeding of livestock, would have been incompatible with a fully regularized commonfield system.” Moreover, the increase of production from technology change would exempt the need for restructuring land use.73 Forth, Campbell found that the regular commonfield system generally did not exist in areas with too dense or too scarce a population due to the reason of population pressure on the economy. If the population was too sparse, there was no need for rationalization of land holding and layout; a more consolidated and enclosed land use would be reasonable with a more extensive form of agriculture. On the contrary, if too many people, the resistance of. 治 政 change make restructuring impossible. 大 立 Whatever the reason for the initiation of the commonfield system, either ethnic or for 74. ‧ 國. 學. survival, the system remained and stuck on. How it took shape was another myth, either from. ‧. natural development to respond from population pressures or from order of a higher authority,. sit. y. Nat. but are now irrelevant to our main quest for answers. This communal style of living sunk in.. io. al. n. socio-economic institution.. er. In the next section, I discuss how the commonfield system runs daily as a long lasting. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 2.2.2 The Daily Workings How did the commonfields operate on a daily basis? In the communal open field system (or the regular commonfield system), “communitarianism” was the essential trait of the system. A communal way of socio-economic life was the order: “Strips of land were cropped individually yet were subject to communal rotations and (typically) communal regulation of cropping….This meant that each farmer was required to. 73 74. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins” 122-123. Campbell, “Commonfield Origins” 123-125. 23.

(31) follow the same time schedule for planting, harvesting, and fallowing his strips in the open fields (although the choice of crops was not always constrained). In addition…villagers had to allow the village herd to graze on their land at times: on the fallow field and on the arable fields after harvest.”75. It was clear that as a farmer in a township adopting the communal open field system, he would have to follow regulations on communal cropping, fallowing, rotations, and grazing. But where do the rules come from? Hopcroft writes: “All of this was regulated by a central body or council of some sort, called the byelaw in England…. This council was responsible for coordinating cropping, harvesting, grazing, and. 治 政 field rotations as well as appointing village shepherds and 大 fence keepers.” 立 Bylaws, as afore mentioned by Buck, are rules of the villages. They regulate almost all 76. ‧ 國. 學. aspects of the agrarian economy activities. How were they made?. ‧. “…evidence points unequivocally to the autonomy of village communities in. sit. y. Nat. determining the form of, and the rules governing, their field systems. They made their. io. al. er. decisions in the light of their own circumstances and their own requirements. In villages which possessed no more than one manor, matters were agreed in the manorial court, and the. n. iv n C decisions sometimes, but not always,hrecorded on the court e n g c h i U roll. Decisions affecting villages. which shared the use of commons were taken at the court of the chief lord, at which all the vills were represented. In villages where more than one manor existed, agreement might be reached at a village meeting at which all tenants and lords were present or represented.”77. This account implies that some kind of consent was to be reached at these institutions of gatherings which were attended by the all stakeholders or representative of the stakeholders. What about rule breaching? “[The byelaw] was also responsible for sanctioning those who violated the rules. If 75 76 77. Hopcroft, Regions,17-18. Hopcroft, Regions, 18. Joan Thirsk, “Field of the East Midlands”, in Baker and Butlin, Studies of Field Systems, 232. 24.

(32) admonishment by the village council was not enough, seigneurial law and the seigneurial court further enforced agricultural rules. Such regulation and enforcement served to maintain the system, because unless all farmers followed the rules the entire field system would break down.”78. Hence, if village bylaws weren’t enough to enforce the norms and punishments, the court of the feudal lord will intervene and defend its authority and order. “Village governance typically worked in conjunction with manorial officials, and vice versa.” In short, byelaws depended on the feudal lordship’s manorial court for deterring and punishing noncompliance of the peasants.79. 治 政 However, who were the peasants? What was their大 relationship with the lordship? 立 Most of the peasants were customary tenants, meaning that they are either personally ‧ 國. 學. bound to the lord in some way (as villeins or serfs), or that their farmed land belonged to. ‧. the manor (hence, they are not freeholders). Customary tenants had to be responsible for. sit. y. Nat. both the lord’s land and his own. In addition, there were other obligations of feudal. io. er. payments and dues in kind, fees, and services. “These often included money rents for using the land, mandatory fees for the usage of manorial facilities—the mills, ponds, ovens, etc.”,. al. n. iv n 80 C as well as taxes of land or goods transfer others taxes. Tenants are also subjected to h eandn g chi U the manorial courts and limits of mobility and other behavior.81 In sum, lords control the land which tenants live on and are tied to. Hence, the influence of the feudal lord “pervades all aspects of life, economic and social”.82. Therefore, this brings one to ask: “How much freedom of decision were the medieval peasants entitled to?” This is a very fair and insightful question. Peasants at this time are not all a serf or “villain”. In general, they can be separated by the types of relationship they have 78 79 80 81 82. Hopcroft, Regions, 19. Hopcroft, Regions, 26. Hopcroft, Regions, 26. Hopcroft, Regions, 65. Hopcroft, Regions, 26. 25.

(33) with the manorial lord. Those who do not own labor service or marriage fines are “free men”. Free men are not under reign of the manorial lord, so they are mainly not the subject of manorial records in which we draw most of our understanding of the agrarian arrangements of the day. If the rights of a free man are impeded upon, he can bring a lawsuit upon the breacher at the royal court, or appeal to the royal justices who travel around the country. Those that fall under the manorial court are unfree tenants, including villeins and customary tenants.83 These tenants are presented at the court/village meetings when community matters are discusses in which bylaws are issued on common grazing and cropping affairs. 84 When disputes arise, villagers were able to serve as jurors and pledges. 85 Hence, these types of. 治 政 participation, gives some extent of legitimacy to the lord’s大 court and village meetings. 立 Why did the British common fields system fail? And how?. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.3 The Collapse. sit. y. Nat. The first and foremost reason is the enclosure movement. The term “enclosure” actually. io. al. er. has three meanings to it: “[1]The enclosure of the great open fields characteristic of midland agriculture;[2] the enclosure of regular town of village commons;[3] the nibbling away of. n. iv n 86 C forest, moor, and other waste land…”.h The situation inU e n g c h i the third meaning has already been. happening since the increase of population from 12-14th centuries.87 By the 13th century, most of the best land has been taken, which leaves naturally lesser arable land left to develop. This implications of this last activity is least impacting to other peasants. However, the situation of the second meaning, the enclosure of the town or village. 83. According to Dyre, “villein” meant “an unfree tenant, holding by a servile tenure”, or in other words, in a “villeinage”. A “customary tenant” is a person holding land under the customs of a manor. This means that such a holding is enforced through the manorial lord’s court, excluding common law, and the person is considered under servitude. “Neif”, is a person born into servility. See Dyre, 2002, p. 140. 84 Dyre, 2002, p. 142. 85 Dyre, 2002, p. 145. 86 John Clapham. 1949/1963. A Concise Economic History of Britain: From the Earliest Times to 1750. London: Cambridge University Press, p. 194 87 Ibid., p. 123. 26.

數據

Outline

相關文件

• P u is the price of the i-period zero-coupon bond one period from now if the short rate makes an up move. • P d is the price of the i-period zero-coupon bond one period from now

• Extension risk is due to the slowdown of prepayments when interest rates climb, making the investor earn the security’s lower coupon rate rather than the market’s higher rate.

• A delta-gamma hedge is a delta hedge that maintains zero portfolio gamma; it is gamma neutral.. • To meet this extra condition, one more security needs to be

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

The first row shows the eyespot with white inner ring, black middle ring, and yellow outer ring in Bicyclus anynana.. The second row provides the eyespot with black inner ring

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the