English Mixing in Advertising in Taiwan:

A Study of English-Literate Readers’ Attitudes

Jia-Ling Hsu

National Taiwan University

This study provides an attitudinal sociolinguistic profile of English mixing in advertisements in Taiwan by investigating the general public’s attitudes towards English mixing in advertising and the socio-psychological features English in advertising has acquired in Taiwan.

The data of this study were collected from a questionnaire survey administered to 425 subjects of various ages, education levels, and occupations. Frequency counts were performed to analyze the data.

Results indicate that various types of English-mixed advertising copy are positively received, and code-mixed copy is far more acceptable than monolingual English copy. Socio-psychologically, internationalism is the most conspicuous feature English has acquired in advertising in Taiwan. However, the specific socio-psychological effects of English vary with different degrees of English mixing in advertising copy and advertised product type. While monolingual English copy yields a greater sense of internationalism than code-mixed copy, code-mixed copy mainly signifies trendiness and cuteness. Using English in advertising imported products helps to promote consumers’ confidence in these products. However, this positive effect of English does not extend either to the promotion of consumers’ confidence in domestic products or to their acceptance of extensive and difficult English, due to the general public’s low English proficiency.

Key words: English mixing in advertising in Taiwan, English-literate readers’ attitudes, socio-psychological features, advertised product type

1. Introduction

English is the foremost linguistic vehicle for the homogenization of global advertising discourse (Bhatia & Ritchie 2006:530) and it is the most frequently used advertising language in non-English speaking countries (Piller 2003:175). English mixing has become a worldwide development in global advertising and has been studied extensively by, for example,Alm (2003), Baumgardner (2008), Bhatia (1992, 2000, 2001, 2006), Bhatia & Ritchie (2006), Chen (2006), Dimova (2012), Gao (2005), Gerritsen et al. (2000, 2007a, 2007b), Hamdan & Hatab (2009), Hilgendorf (2010), Hilgendorf & Martin (2001), Lee (2006), Martin (1998, 2002, 2007, 2008), Petery (2011), Ustinova (2006), among many others. However, the majority of the studies conducted so far are based on textual analyses. Empirical studies investigating consumers’ attitudes toward English mixing in advertising are relatively scarce (Leung 2010).

Leung (2010) conducted a survey of 278 local Chinese residents in Hong Kong to explore their attitudes towards Chinese-English mixing in print ads. The results show that most code-mixed ads could be understood and code-mixed copy could best advertise convenience products and shopping products. Furthermore, code-mixing was preferred by young and educated people.

Other research on consumers’ attitudes toward the use of English in advertising has been conducted by advertising and marketing professionals. However, the purpose of their research is not to develop a sociolinguistic profile of the impact of English mixing on consumers, but to test the marketing effectiveness of using English on consumers in advertising by comparing the use of standardized English ads with the ads that have been adapted to the local languages. For example, Gerritsen et al. (2000) conducted an attitudinal study of 30 Dutch men and 30 Dutch women across two age groups. The results revealed that all subjects showed a negative attitude toward the use of English in TV commercials and a reduced degree of comprehension of the commercials. Gerritsen et al. (2007b, quoted in Hornikx et al. 2010:172) used highly educated young women from Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain as subjects and examined the effectiveness of English vs. a local language, such as Dutch or German, in print ads. The results showed that for three out of the four ads tested, no significant difference was found in the attitudes toward the languages under test. In Hornikx et al. (2010), 120 working Dutch participants, aged from 20 to 63, with various educational backgrounds, viewed a number of Dutch car ads containing English slogans ranging from easy to difficult. The result indicated that easy English slogans were better assessed than the difficult ones and the extent of difficulty to which the English slogans were comprehended affected participants’ preference for English. It was therefore suggested that business should employ easy English. Puntoni et al. (2008) showed that 64 Dutch-French-English trilingual participants found their local languages more emotionally appealing than English in advertising.

The above review indicates that most of the attitudinal research discussed is concerned with testing the marketing effectiveness of “standardizing ads by using the English language” (Hornikx et al. 2010:185). Investigation of consumers’ attitudes towards English mixing in a sociolinguistic approach is relatively rare.

Building on a sociolinguistic framework, this study addresses the following two issues: (1) the general public’s attitudes towards the various levels of English mixing in advertising; (2) the socio-psychological effects of English in advertising in Taiwan.

2. Methodology

numerous linguists have provided definitions for “code-mixing,” (Bokamba 1989, Muysken 2000, Ho 2007), this study follows Kachru’s definition (1986:64) as cited in Hsu (2008:156)—English mixing is broadly defined in this paper as the transfer of English words, phrases, and sentences into Chinese at inter-sentential and intra-sentential levels.

The corpus of data of this study was drawn from a survey in the form of questionnaires conducted to a sample of 425 subjects in Taiwan, consisting of 189 males and 236 females, aged from 14 to 87. These subjects were composed of students, housewives, retired people, and professionals from 49 occupations. Their level of education ranged from junior middle school to doctoral degrees. The minimum qualification required of these subjects to be termed “English-literate”was that they needed to have at least two years of formal English education in order to be able to comprehend the survey patterns of English mixing in the questionnaires, such as the simple English vocabulary “happy,” and “easy,” which abound in advertisements in Taiwan.1 For detailed demographic information about the subjects, please see Appendix 1.

The questionnaire consisted of five sections: demographic information of subjects, sociolinguistic features of English in advertising, subjects’ attitudes toward English mixing in advertising, subjects’ attitudes toward linguistic factors at work in English-mixed advertising, and subjects’ attitudes toward the general trend of using English in advertising. For the detailed questionnaire design, please see Appendix 2.

The first section elicited subjects’ demographic information, such as their gender, age, level of education, occupation, and dialects spoken at home.

The second section explored “the invisible socio-psychological features which English has acquired in the process of being used in global advertising” as postulated by Bhatia (2001:211) and Bhatia & Ritchie (2006:536). According to Bhatia, the invisible socio-psychological features can be classified into the threshold features which can best be characterized as general, but critical features. Once these threshold features are acquired, the subsets of their related features, proximity zones, become accessible. The threshold features include internationalism and standardization, future

and innovation, competence, etc. The proximity zones or subsets of features include standards of measure, Westernization, quality, and so on. For detailed information on

these features, please see Table 6. For the exact design of this section of the questionnaire, please see A3 in Appendix 2.

1 English-literate readers in this paper do not refer to English-proficient readers but subjects who know

at least some basic English vocabulary, as opposed to English-illiterate readers, who cannot speak, read, or write English at all. I investigated the attitudes of 520 readers toward English mixing in advertising in Taiwan; the readers included 425 subjects who knew English and 95 subjects who didn’t know any

In the questionnaire, out of a multiple-choice format adapted from the framework proposed by Bhatia and Bhatia and Ritchie as discussed above, subjects were requested to pick freely the threshold socio-psychological features and their subsets of features which subjects consider are associated with them via the use of English in advertisements.

The third section of the questionnaire tested Martin’s hypothesis (2002:385) that “The degree to which a unit of discourse is Anglicized…is bound to have important socio-psychological effects, particularly in the case of advertising,” by examining subjects’ attitudes towards a cline of English mixing in advertising in Taiwan. Martin (2002:385) introduces a cline of code-mixing advertising as a possible means for describing code-mixed ads, regarding the proportion of English vs. non-English from a structural perspective, to focus on “the syntactic properties of the English components eventually contained therein.” According to Martin (2002:385), the cline ranges from English monolingual, through sentential, phrasal, and isolated lexical substitution by English, then through phrasal and isolated lexical substitution by the host language, and to host language monolingual. That is, the cline includes respective monolingual copy at both ends, with the percentage of English elements decreasing from one end to the other.

In this section of the questionnaire, ten questions composed of three levels of the use of English were posed to elicit participants’ attitudinal responses, and these questions were copied from local newspaper ads, such as United Daily News and

China Times, and a TV commercial. Before the subjects were requested to provide

responses to the specific verbal text in each individual question, they needed to first look at the pictures of ads with general verbal and non-verbal text (pictures 1-3 in Appendix 2). In this case, they were requested to get a mental map of what the visual text and general wording were about before focusing on the specific verbal text given in each question.

On the lexical level, Chinese text mixed with English lexis, namely, terminology such as RAM, and common words such as “happy,” was tested. Common words were further respectively categorized into adjectives (such as “easy”), verbs (such as “think”), adverbs (such as “very”), nouns (such as “time”), prepositions (such as “off”), and conjunctions (such as “or”). On the sentential level, Chinese text mixed with English sentences such as “Come on, baby” and slogans such as “Trust me; you can make it” was tested. On the discourse level, English monolingual advertising copy was tested. For the exact verbal text being tested, please see A to D in Appendix 2. Following each question, five grades of attitudinal choices on a Likert scale were provided: “completely acceptable,” “acceptable,” “neutral,” “unacceptable,” and

“completely unacceptable.” Subjects were requested to make a choice for each question.

In addition, this part of the questionnaire surveyed subjects’ general attitudes toward English monolingual copy vs. various types of code-mixed copy.

The fourth section of questions examined how subjects’ attitudes towards advertisements involving English mixing might be influenced by the following linguistic factors: (1) whether using English in advertisements helps to enhance consumers’ confidence in the advertised products; (2) whether increasing the number of English words in advertisements helps to enhance consumers’ confidence in the advertised products; (3) whether using difficult English vocabulary in advertisements such as “unassailable beauty” affects readers’ interest in reading the advertisements or their degree of acceptance of the advertisements; (4) whether linguistic errors found in advertisements such as “enableing the disable” affect the acceptability of the advertisements. For the verbal text of this section of pictures, please see pictures 4-6 in Appendix 2. Regarding this section of the questionnaire design, please see E, G, and H.

The last part of the questionnaires investigated subjects’ attitudes towards the general trend of using English in advertising. Please see I of the questionnaire in Appendix 2 for reference.

Frequency count was conducted for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1 The general public’s attitudes toward survey patterns

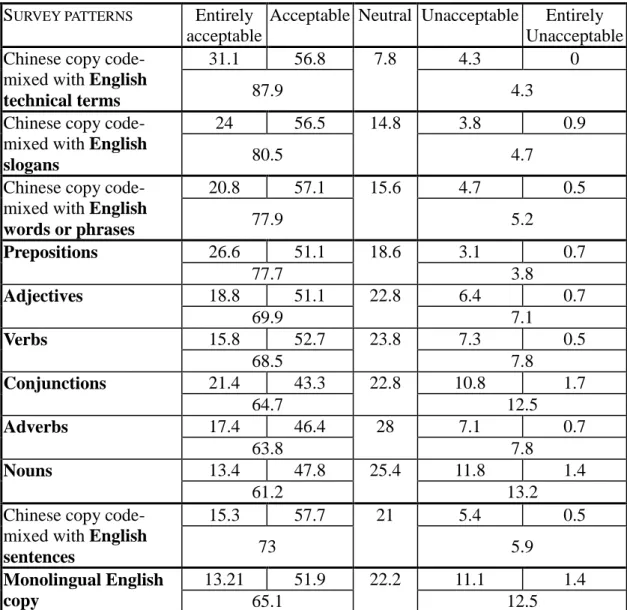

In general, asTable 1 indicates, all the survey patterns under test are well received, with their acceptability rates ranging from 65 percent up to 88 percent. Among these patterns, Chinese copy mixed with English terminology has the highest degree of acceptability, and English monolingual copy, the lowest.

Regarding English common words mixed with Chinese copy, as underlined in the following examples, prepositions in “50% off” and “taibei vs. niuyue” ‘Taipei vs. New York’ are the most acceptable. Following in a descending order are adjectives, “chuangye hen easy, jiameng hen happy” ‘To start the business is very easy; to join the franchise is very happy’; verbs, “xinshiji come, toupixue go” ‘The new century comes; one’s dandruff goes’; and conjunctions, “zeng bacun shengridangao or jiweijiu” ‘to give you free an eight-inch birthday cake or a cocktail drink’. Adverbs, “dameilezhaji very cui very nen” ‘Domino’s fried chicken is very crispy and very tender’, and nouns, “jiranyongyou Power, zuodejueding yinggaishiyou Power” ‘Since you have the power, the decisions you make should also be of power’ have the lowest

frequency.

Table 1. Percentage of acceptability of the cline of Chinese-English code-mixed patterns

SURVEY PATTERNS Entirely

acceptable

Acceptable Neutral Unacceptable Entirely Unacceptable Chinese copy

code-mixed with English

technical terms

31.1 56.8 7.8 4.3 0

87.9 4.3

Chinese copy code-mixed with English

slogans

24 56.5 14.8 3.8 0.9

80.5 4.7

Chinese copy code-mixed with English

words or phrases 20.8 57.1 15.6 4.7 0.5 77.9 5.2 Prepositions 26.6 51.1 18.6 3.1 0.7 77.7 3.8 Adjectives 18.8 51.1 22.8 6.4 0.7 69.9 7.1 Verbs 15.8 52.7 23.8 7.3 0.5 68.5 7.8 Conjunctions 21.4 43.3 22.8 10.8 1.7 64.7 12.5 Adverbs 17.4 46.4 28 7.1 0.7 63.8 7.8 Nouns 13.4 47.8 25.4 11.8 1.4 61.2 13.2

Chinese copy code-mixed with English

sentences 15.3 57.7 21 5.4 0.5 73 5.9 Monolingual English copy 13.21 51.9 22.2 11.1 1.4 65.1 12.5

This result partly contradicts the original working hypothesis of this paper based on the discourse analysis conducted by Hsu (2008). According to Hsu (2008:166), in a total of 1265 Chinese-English code-mixed advertisements, among the 5185 English components, excluding terminology and proper nouns such as company names and brand names, common nouns have the highest frequency (7 percent), followed by adjectives (2 percent), verbs (1 percent) and adverbs (0.0027 percent). As to prepositions and conjunctions, their occurrences are too minimal to be counted.

Based on the distribution of these common words, it was hypothesized that the extent of popularity of English common words correlates positively with their frequency in ads. According to this hypothesis, nouns and adjectives should receive the highest degree of acceptability in this attitudinal study, and adverbs, prepositions

and conjunctions, the least. However, partly contrary to the original expectation, prepositions are the most popular linguistic category and nouns, the least popular. It is suspected that prepositions such as ‘off’ and ‘vs.’ are brief in form, easy to read, and unusual in usage, which conveys a fresh feeling and easy comprehensibility to the readers. By contrast, the nouns that appeared in the survey, such as lobby and shopping, seem to be bland and ordinary to the subjects. For a valid explanation, further analysis is needed.

Concerning adverbs, as was hypothesized, they receive the second lowest degree of acceptability. However, they still have a relatively higher extent of acceptability than expected. The account is given below. The survey pattern used in the questionnaire was taken from a TV commercial. Whether subjects had viewed this TV commercial influences their degree of acceptance of this pattern. Among those who had not viewed this TV commercial, the percentage of acceptability and that of unacceptability of this usage are roughly the same, 34.7 percent vs. 30.6 percent. By contrast, among those who had seen this commercial, the rate of acceptability as opposed to that of unacceptability is 67.7 percent vs. 4.6 percent. Such an overwhelming statistical discrepancy indicates the immense impact of TV commercials in promoting viewers’ positive attitudes toward the linguistic forms of advertising language under test. This result corresponds to Holmes’ observation that when it comes to language change, exposure to new linguistic forms on television can “soften people up” by presenting new forms employed by celebrities (2008:224).

As to monolingual English copy, it is least acceptable among all the survey patterns. An explanation will be provided in Section 3.2.4.

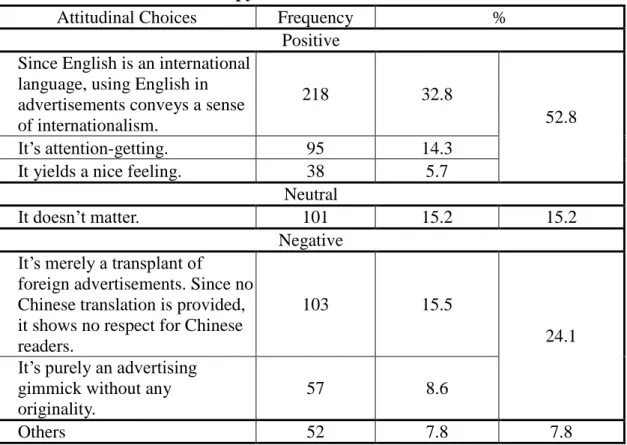

When it comes to subjects’ general attitudes toward the various degrees of mixing English components in advertisements, Table 2 shows that on monolingual English copy, more than half of the responses are positive, holding that using such English copy provides a sense of internationalism and is attention-getting. On the contrary, most of the negative responses, comprising one fourth of the total feedback, view such ads, with no Chinese translation provided, as a transplant of foreign advertisements into Taiwan’s market, showing no respect for Chinese readers.

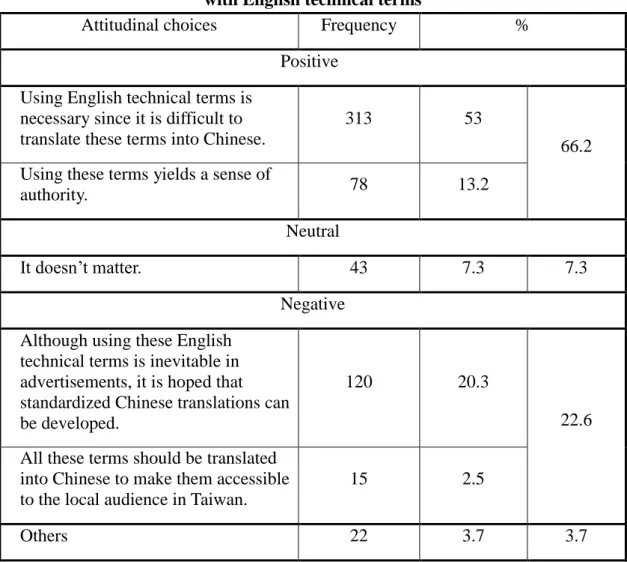

On Chinese copy mixed with English technical terms, according to Table 3, two thirds of the responses consider that using English terms yields a sense of authority, and such use is inevitable because translating all these technical English terms into Chinese poses a great deal of difficulty. By contrast, only around one fifth of the feedback holds that more terms should be translated into Chinese.

Table 2. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices towards monolingual English copy of advertisements*

Attitudinal Choices Frequency %

Positive Since English is an international

language, using English in advertisements conveys a sense of internationalism.

218 32.8

52.8

It’s attention-getting. 95 14.3

It yields a nice feeling. 38 5.7

Neutral

It doesn’t matter. 101 15.2 15.2

Negative It’s merely a transplant of

foreign advertisements. Since no Chinese translation is provided, it shows no respect for Chinese readers.

103 15.5

24.1 It’s purely an advertising

gimmick without any originality.

57 8.6

Others 52 7.8 7.8

*Due to rounding errors, the total is less than 100%.

The above analysis shows that using English terminology mainly helps to fill the lexical gap in the native language, namely, Chinese, a purpose also noted in Hong Kong, where mixing English terms in ads of convenience products and shopping products is considered “more informative to consumers” and serves as “an emotional buffer to replace the unwanted Cantonese words with emotive meaning” such as condom and underwear (Leung 2010:55).

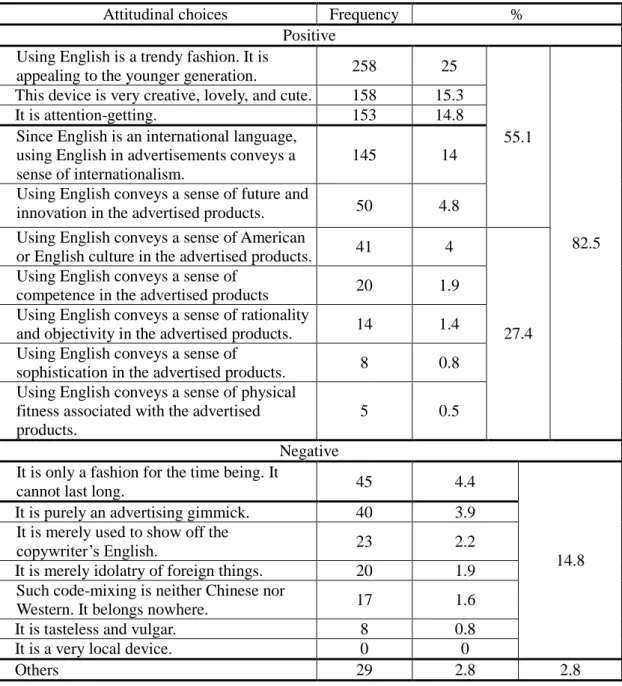

Concerning Chinese copy code-mixed with English common words and phrases such as ‘summer sale’, Table 4 shows that 55 percent of responses indicate that mixing English in such a manner is a trendy fashion, creative, lovely, cute, attention-getting, and appealing to the younger generation. 27 percent of responses suggest that such mixing yields a variety of socio-psychological effects, with internationalism being the most prominent. Compared with a total of 83 percent positive comments, only 15 percent of responses are negative.

Table 3. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices towards Chinese copy mixed with English technical terms

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Positive

Using English technical terms is necessary since it is difficult to translate these terms into Chinese.

313 53

66.2 Using these terms yields a sense of

authority. 78 13.2

Neutral

It doesn’t matter. 43 7.3 7.3

Negative

Although using these English technical terms is inevitable in advertisements, it is hoped that standardized Chinese translations can be developed.

120 20.3

22.6

All these terms should be translated into Chinese to make them accessible to the local audience in Taiwan.

15 2.5

Others 22 3.7 3.7

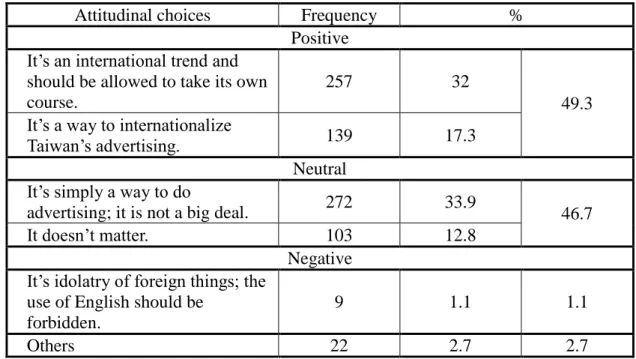

Lastly, Table 5 indicates that on subjects’ attitudes toward the general trend of using English in advertising, 95 percent of responses are either positive or neutral, with roughly similar percentages, compared with a very limited number of negative responses. Positive comments hold that using English in advertising is an international trend and should be allowed to take its own course, and that such advertising helps to internationalize Taiwan’s market. The neutral responses treat the use of English in advertising as merely a way of doing advertisements—it is no big deal.

Table 4. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices toward Chinese copy mixed with English words and phrases*

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Positive Using English is a trendy fashion. It is

appealing to the younger generation. 258 25

55.1

82.5 This device is very creative, lovely, and cute. 158 15.3

It is attention-getting. 153 14.8

Since English is an international language, using English in advertisements conveys a sense of internationalism.

145 14

Using English conveys a sense of future and

innovation in the advertised products. 50 4.8

Using English conveys a sense of American

or English culture in the advertised products. 41 4

27.4 Using English conveys a sense of

competence in the advertised products 20 1.9

Using English conveys a sense of rationality

and objectivity in the advertised products. 14 1.4

Using English conveys a sense of

sophistication in the advertised products. 8 0.8

Using English conveys a sense of physical fitness associated with the advertised products.

5 0.5

Negative It is only a fashion for the time being. It

cannot last long. 45 4.4

14.8

It is purely an advertising gimmick. 40 3.9

It is merely used to show off the

copywriter’s English. 23 2.2

It is merely idolatry of foreign things. 20 1.9

Such code-mixing is neither Chinese nor

Western. It belongs nowhere. 17 1.6

It is tasteless and vulgar. 8 0.8

It is a very local device. 0 0

Others 29 2.8 2.8

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

The above frequency analysis indicates that survey subjects display largely positive attitudes toward the various types of English-mixed copy in advertisements. On the whole trend of development, with the exception of very few negative responses, the overwhelming majority remain neutral or positive.

Table 5. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices towards the trend of using English in advertisements

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Positive It’s an international trend and

should be allowed to take its own course.

257 32

49.3 It’s a way to internationalize

Taiwan’s advertising. 139 17.3

Neutral It’s simply a way to do

advertising; it is not a big deal. 272 33.9 46.7

It doesn’t matter. 103 12.8

Negative It’s idolatry of foreign things; the

use of English should be forbidden.

9 1.1 1.1

Others 22 2.7 2.7

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

3.2 The socio-psychological effects English has developed in advertising in Taiwan

When it comes to the socio-psychological effects English is capable of conveying in advertisements in Taiwan, several pieces of evidence will be presented cross-referentially to arrive at an overall understanding. These pieces of evidence are concerned with, on the one hand, the specific threshold features English transmits in various types of advertisements, and on the other hand, how various factors, such as the type of advertising copy, the type of advertised products, and certain linguistic factors, come into play in influencing the impact of English usage on the readers.

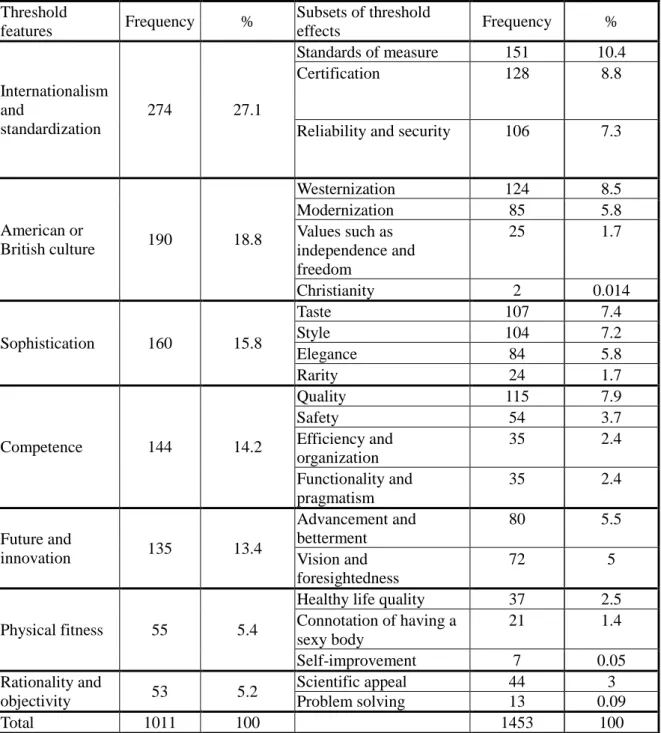

3.2.1 The threshold features and their subsets of features

In terms of what threshold socio-psychological characteristics English is capable of transmitting in advertising in Taiwan, Table 6 indicates that internationalism and

standardization and American or British culture are the two most prominent

socio-psychological features English has developed. Less pronounced features include

future and innovation, competence, and sophistication. Physical fitness as well as rationality and objectivity are least recognized.

Table 6. Percentage of the threshold socio-psychological effects English has transmitted in advertising in Taiwan*

Threshold features Frequency % Subsets of threshold effects Frequency % Internationalism and standardization 274 27.1 Standards of measure 151 10.4 Certification 128 8.8

Reliability and security 106 7.3

American or British culture 190 18.8 Westernization 124 8.5 Modernization 85 5.8 Values such as independence and freedom 25 1.7 Christianity 2 0.014 Sophistication 160 15.8 Taste 107 7.4 Style 104 7.2 Elegance 84 5.8 Rarity 24 1.7 Competence 144 14.2 Quality 115 7.9 Safety 54 3.7 Efficiency and organization 35 2.4 Functionality and pragmatism 35 2.4 Future and innovation 135 13.4 Advancement and betterment 80 5.5 Vision and foresightedness 72 5 Physical fitness 55 5.4

Healthy life quality 37 2.5

Connotation of having a sexy body 21 1.4 Self-improvement 7 0.05 Rationality and objectivity 53 5.2 Scientific appeal 44 3 Problem solving 13 0.09 Total 1011 100 1453 100

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

This result confirms Bhatia & Ritchie’s comment that English is “best suited to convey American or British culture” (2006:538), but it contradicts Takashi’s observation that English does not index Americanization or Westernization in Japanese advertising (1990a, 1990b, 1992, quoted in Piller 2003:175).

On the subsets of these threshold features, standards of measure, certification,

Westernization, quality, reliability and security (authenticity in Bhatia’s term), taste,

more than 100 times. On the other hand, the least noticed features, rated with less than 25 occurrences, include values such as independence and freedom, problem-solving,

self-improvement, and lastly Christianity, which has only two occurrences. As

opposed to the prominent features such as standards of measure and Westernization, most of the least recognized features, especially Christianity, pertain essentially to Western cultural values. The low frequency of these features suggests that although the threshold feature American or British culture is recognized as the second most prominent feature, its subset of features, which underlie the cultural essence, themes, and roots of Western civilization, are those that English has failed to acquire in Taiwan. This finding contradicts Bhatia & Ritchie’s prediction (2006:537) that once certain threshold features are acquired, their subsets of features will become automatically accessible. This result also differs from Martins’ observation (1998:321) that in French advertising, American English functions to convey concepts such as freedom and adventure.

3.2.2 Advertising copy

In examining the socio-psychological features developed in the various types of advertising copy, internationalism is the most conspicuous feature transmitted in advertisements with monolingual English copy, consisting of 33 percent of responses, as shown by Table 2. Attention-getting is the second most frequent positive feature noted by the public.

By contrast, for advertisements code-mixed with simple English words or phrases such as “easy” “happy,” and “summer sale,” Table 4 shows that being lovely, cute,

creative and attention-getting along with being trendy, appealing to the younger generation are the most distinguishing features English has developed (a total of 55

percent). Internationalism, the most distinct feature in the monolingual English copy of advertisements, constitutes only 14 percent of responses in this type of advertisements.

The statistical difference revealed by the comparison of the monolingual English copy and the copy mixed with simple English words suggests that the socio-psychological effects English is capable of developing vary with different types of advertising copy. Other than attention-getting, a feature shared by both types of advertising copy, monolingual English copy yields a greater sense of internationalism than copy code-mixed with simple English vocabulary.

Mixing simple English vocabulary is regarded as a trendy fashion that appeals to young people and that conveys a sense of cuteness, loveliness and originality. Mixing English to appeal to young people seems to be a global advertising strategy also noted

in Hong Kong, Germany, and Japan. In Hong Kong, code-mixing in advertising is preferred by young people more than other age groups (Leung 2010:49). Piller observes that in German advertising, “. . . English is portrayed as the language of . . . the young, cosmopolitan business elite” (2003:176). In Japan, by using English loanwords extensively in advertisements, Japanese advertisers utilize students’ and young people’s positive attitudes toward English and the international value associated with English to create an attention-getting effect and to “cater to young people’s desires” to be cosmopolitan (Takashi 1990b:335-336).

3.2.3 Product type

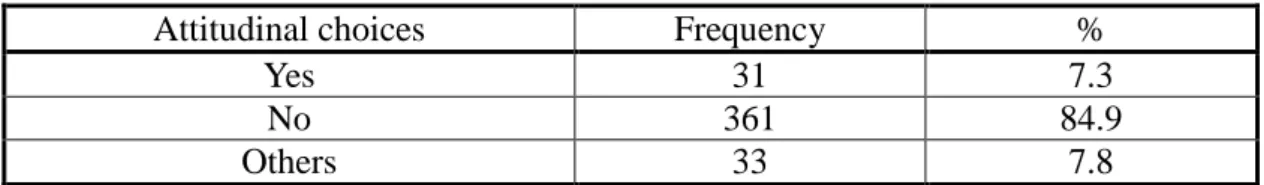

In addition to the influence coming from the advertising copy, the type of advertised products also affects the socio-psychological effects English is capable of transmitting in advertisements.2 Table 7 reveals that when asked whether using English in advertisements can help to enhance readers’ confidence in products imported from abroad or marked by technological innovation, 53 percent of the subjects hold that using English does help to promote their confidence in these products as opposed to 38 percent who disagree. However, when it comes to domestic products, such as local real estate properties or fitness centers, 85 percent vs. 7 percent of the subjects provide negative feedback, as revealed by Table 8.

Table 7. Percentage of subjects who feel English in ads does or does not enhance their confidence in products featuring fashion, technology, or imports

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 225 53

No 163 38

Others 37 9

Table 8. Percentage of subjects who feel English in ads does or does not enhance their confidence in local products

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 31 7.3

No 361 84.9

Others 33 7.8

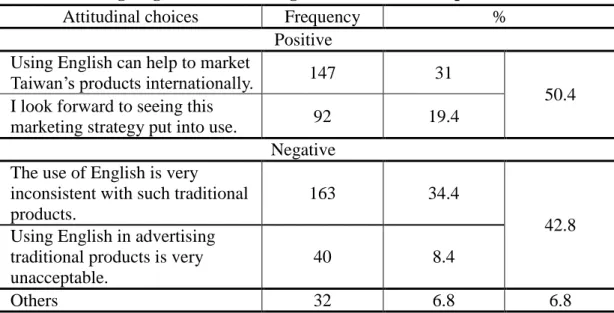

Furthermore, Table 9 shows that, in regard to whether traditional Chinese products, such as Chinese medicine, can be advertised in English (please see F of the

2 According to Business Dictionary.com (September 11, 2012), product type refers to a grouping of

similar kinds of manufactured goods or services. In this paper, product type refers to advertised products imported from abroad as opposed to those domestically manufactured.

questionnaire in Appendix 2 for reference), negative responses outnumber favorable responses to a huge extent (46 percent to 25 percent). Concerning the possibility of using English to advertise Chinese traditional products, Table 10 shows that almost half of the subjects take an approving attitude because using English can help to market traditional products globally; however, a slightly lesser number of the subjects disapprove because of the cultural incompatibility and the stylistic incongruity between the advertising language and the product type.

The statistical discrepancy between acceptability and unacceptability rates revealed by Table 9 seems to validate Jain’s observation (1989:43) that English as a language symbolizing internationalism, modernization, and industrial and technological innovations is not consistent with locally and culturally sensitive products .

Table 9. Percentage of subjects’ degree of acceptance of using English in advertising traditional Chinese products such as Chinese medicine*

Degree of acceptability Frequency %

Entirely acceptable 12 2.8 25.4 Acceptable 96 22.6 Neutral 121 28.5 Unacceptable 163 38.4 45.9 Entirely unacceptable 32 7.5 Total 424 100

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

Table 10. Frequency of subjects’ attitudinal choices towards the possibility of using English in advertising traditional Chinese products

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Positive Using English can help to market

Taiwan’s products internationally. 147 31

50.4 I look forward to seeing this

marketing strategy put into use. 92 19.4 Negative

The use of English is very inconsistent with such traditional products.

163 34.4

42.8 Using English in advertising

traditional products is very unacceptable.

40 8.4

Others 32 6.8 6.8

also witnessed in other cultures. Krishna & Ahluwalia (2008) note that in India, the advertising effectiveness of different language formats (e.g., the local language vs. English or a mix of the two languages) varies with different product types. When the advertised product is a foreign luxury item, such as chocolate, an English slogan is more favorably evaluated than a Hindi slogan. By contrast, when the advertised product is a necessity, such as detergent, a Hindi slogan is more favorably assessed. Therefore, English is associated with sophistication whereas Hindi has a stronger association with in-group belongingness. In Japan, Japanese rather than English terms are used in advertising traditional Japanese items (Takashi 1990b:332). In Hungarian advertising, using English expresses modernity whereas “the absence of English is linguistically associated with tradition” (Petery 2011:21).

The above analysis suggests that English in Taiwan symbolizes internationalism and standardization, Westernization, authenticity, and quality. Using English in advertisements tends to contribute to customers’ having more confidence in advertised products of foreign imports or of technological innovation. This benefit of English, however, does not extend to domestic products, especially traditional types of products, due to their local characteristics and cultural constraints.

3.2.4 Linguistic factors

Likewise, the enchanting power of English does not extend to subjects’ acceptance of lengthy use of English in advertisements. Tables 11 and 12 reveal that when it comes to whether increasing the number of English words may help to promote subjects’ confidence in advertised products, a roughly equal number of negative responses are elicited, no matter what type of products they are, or where they are manufactured. Hence, as previously discussed, the extent to which English helps to enhance readers’ confidence in advertised products varies with product type. English works far better with technological advanced products and foreign imports than with domestic products. However, increasing the number of English words in advertisements does not help but tends to inhibit readers’ confidence in the advertised products, regardless of the product type.

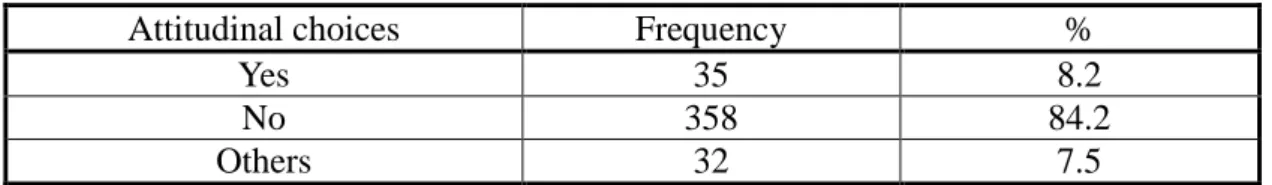

Table 11. Subjects’ responses to whether more English words in ads enhance their confidence in products featuring fashion, technology, or imports*

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 35 8.2

No 358 84.2

Others 32 7.5

Table 12. Subjects’ responses to whether more English words in ads enhance their confidence in local products

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 23 5.4

No 375 88.7

Others 25 5.9

Two more pieces of evidence demonstrate the psychological barrier caused by readers’ English language barriers. The first one deals with the impact of linguistic factors on the acceptance of certain advertisements. The second is drawn from frequency analysis of subjects’ acceptance of the monolingual English copy of advertisements.

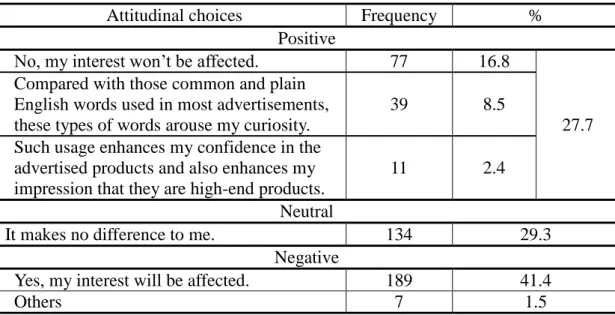

Tables 13, 14, 15 and 16 show that linguistic factors such as the number of English words and the level of difficulty of English words used in advertisements both affect readers’ interest in continuing to read the advertisements and their acceptance of the advertisements. However, English grammatical or spelling mistakes such as “enableing the disabled” do not entail negative effects. To illustrate, when asked whether English errors have ever been identified in advertisements, more than two fifths of subjects, i.e., 41.3 percent, cannot tell whether there are any mistakes, while 37.7 percent of subjects claim that they have identified errors. This relatively higher frequency of subjects’ being unable to identify any mistakes seems to point to the readers’ generally low level of English proficiency.

Table 13. Subjects’ responses to whether difficult English words will affect their interest in reading the ads or their acceptance of the ads*

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Positive

No, my interest won’t be affected. 77 16.8

27.7 Compared with those common and plain

English words used in most advertisements, these types of words arouse my curiosity.

39 8.5

Such usage enhances my confidence in the advertised products and also enhances my impression that they are high-end products.

11 2.4

Neutral

It makes no difference to me. 134 29.3

Negative

Yes, my interest will be affected. 189 41.4

Others 7 1.5

Table 14. Percentage of subjects’ identification of improper or mistaken English usage in ads*

Subjects’ choices Frequency %

I cannot tell if there are any errors. 175 42.2

Yes, I have noticed some errors. 160 38.6

No, there are no errors. 78 18.8

Others 2 0.5

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

Table 15. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices concerning whether English mistakes affect their degree of acceptance of the ads

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 164 39

No 257 61

Table 16. Percentage of subjects’ attitudinal choices concerning whether the amount of English words used may affect their degree of acceptance of the ads

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Yes 238 56.5

No 183 43.5

When further inquired whether the identification of English mistakes may affect their acceptance of the advertisements, 61 percent as opposed to 39 percent of the subjects hold that it makes no difference. However, when asked whether the number of English words used in advertisements may affect their interest and acceptance of advertisements, 56 percent of subjects respond affirmatively and 43 percent negatively.3 Furthermore, when asked whether employing difficult vocabulary such as “unassailable beauty” in advertisements may affect their interest in reading the ads, 41 percent of the subjects reply affirmatively and 17 percent negatively.

This part of the analysis suggests that due to the readers’ overall low level of English proficiency, English mistakes in advertisements in general are either unidentified by or of no concern to them. However, when the English text is lengthy and the vocabulary used is difficult, readers’ interest in reading English-mixing advertisements tends to be inhibited.

The above finding leads to the issue of whether the degree of comprehension of English affects the appreciation of English in advertising. Some studies such as Baumgardner (2008:38) and Blair (1997:75, quoted in Baumgardner 2008:38) argue

3 This question was designed as a simple “yes-no” question. However, open-ended follow-up questions

were also designed to elicit subjects’ underlying reasons for their answers to the “yes-no” question. Results of qualitative analysis of the categories of subjects’ reasons provided the statistical information listed in Table 16.

that in Mexican and Japanese advertising, when English is employed as a language display, whether a reader understands it or not does not matter, since the foreign language is primarily utilized to add prestige to the advertised products.

However, scholars such as Gerritsen et al. and Hornikx et al. hold different views. Gerritsen et al. (2000:28) find that participants’ appreciation for the use of English in six partly or completely English TV commercials broadcast in the Netherlands increases when they have higher comprehension.

Hornikx et al. (2010:169) observe that easy English slogans are better appreciated than difficult slogans. In addition, the degree of difficulty in comprehending the English slogans affects participants’ preference for English. When English is easy to understand, it is preferred to Dutch. When it is difficult to understand, Dutch equivalents are appreciated as much as English.

Similarly, in China, although English is not used for communicating information about advertised products, for impressing the audience that the products are of good quality, only English lexical items rather than complete English sentences are used, lest the information concerning the advertised products should not be conveyed successfully (Gao 2005:834).

In Hong Kong, according to Leung (2010:54), code-mixing is a quite common language phenomenon and English mixing in advertising does not cause difficulty to audiences. However, in mixing English terms in print advertisements, advertisers mainly choose single simple English words, understandable to and acceptable by the general public.

All the above studies seem to be in line with the results of the present research, which argues that the degree of difficulty of English words and the length of English text do affect non-native speakers’ comprehension of English, which in turn affects their preference for the use of English in ads and consequently for the advertised products.

This observation is further supported by a previous finding, i.e., the frequency analysis of the monolingual English copy of advertisements. As discussed in Section 3.1, among the cline of English use, monolingual English copy receives the lowest degree of acceptability. This lowest frequency suggests again the psychological barrier induced by the language barrier of the readers.

Lastly, all the factors discussed above—the threshold features, advertising copy, advertised product type, and linguistic factors—interact in contributing not only to all the above observations but also to the results shown in Tables 17 and 18, which in turn validates the generalizations made so far. When surveyed regarding the most preferred copy of advertising language, as revealed by Tables 17 and 18, subjects’ preferences vary depending on where the products are manufactured. When it comes

to products imported from abroad, 88 percent of the responses prefer the use of English in advertisements, 77 percent among which are made for the code-mixing type of language, whereas 11 percent choose monolingual English copy. Among the various types of code-mixed copy, Chinese copy mixed with English terminology is most preferable (40 percent). Following in a descending order are Chinese copy mixed with English words and Chinese copy mixed with English sentences.

Table 17. Percentage of subjects’ preferences for the most effective advertising copy if the advertised products are manufactured abroad*

Attitudinal choices Frequency %

Chinese copy mixed with English

technical terms

184 40.2

76.8

87.9 Chinese copy mixed

with English common words

100 21.8

Chinese copy mixed with English sentences 68 14.8 Monolingual English copy 51 11.1 11.1 Monolingual Chinese copy 24 5.2 5.2 5.2 Others 31 6.8 6.8 6.8

*Due to rounding errors, the total is more than 100%.

Table 18. Percentage of subjects’ preferences for the most effective advertising copy if the advertised products are manufactured domestically*

Attitudinal Choices Frequency %

Monolingual Chinese

copy 204 44.9 44.9 44.9

Chinese copy mixed with English common words

120 26.4

48.6

49 Chinese copy mixed

with English technical terms

63 13.9

Chinese copy mixed

with English sentences 38 8.4 Monolingual English

copy 2 0.04 0.04

Others 27 5.9 5.9 5.9

On the other hand, for domestic products, monolingual Chinese copy is held to be the best advertising copy, rated with the highest frequency (45 percent of responses). In spite of such primary preference, almost half of the total choices favor code-mixing type of language, with Chinese copy mixed with simple English words as the most preferred copy (26.4 percent). Second and third in the order are Chinese copy mixed with English terminology and Chinese copy mixed with English sentences.

A cross-referencing comparison of the results as revealed in Tables 17 and 18 highlights several socio-psychological effects worth discussing. First, a similar order of code-mixed copy preferred by the subjects occurs in both tables, i.e., Chinese copy mixed with lexis such as common words or technical terms, followed by Chinese copy mixed with sentences, followed by monolingual English copy. Such descending order of advertising copy indicates that the greater the degree of English is mixed in the copy, the less preferable and acceptable the copy is. Once again, this part of the analysis shows that due to the subjects’ underlying psychological barrier stemming from their language barrier, the amount of English words used does affect their preference for English-mixed advertisements.

By the same token, concerning the most effective advertising copy for products manufactured abroad, owing to the public’s general psychological barrier in processing lengthy English text, 77 percent of the subjects’ choices indicate a preference for code-mixed copy as opposed to 11 percent which favor monolingual English copy, although monolingual English copy transmits a greater sense of internationalism in foreign imports than code-mixed copy. Such a preference accords with the result of the subjects’ attitudinal survey as previously demonstrated, where monolingual English copy receives the lowest degree of acceptability.

Furthermore, the comparison shows that where the advertised products are manufactured determines subjects’ preference for the most ideal advertising copy. When it comes to foreign imports, 88 percent of subjects’ choices demonstrate a preference for the use of English, with more than three quarters of them favoring English mixing. Conversely, for domestic products, the percentage for the use of English, i.e., mainly mixing, drops to less than half; roughly the other half of the responses prefer no use of English at all. Such a discrepancy in statistics once again suggests that using English in advertising products manufactured abroad does entail a sense of internationalism and authenticity, which in turn gives the readers a sense of psychological security about the advertised products. For local products, the power of English is constrained to a large extent.

Due to the same psychology, subjects view Chinese copy mixed with English technical terms as the most preferred copy for products imported from abroad whereas Chinese copy mixed with simple vocabulary is the second preference for local

products. As previously discussed, English terminology yields a sense of authority in the advertised products. Therefore, as to advertised products manufactured from abroad, in order for the subjects to feel secure with a feeling of authority, authenticity and internationalism in the products, without being bothered with reading lengthy English, two-thirds of the subjects’ choices are made for the mixing of English terminology as the most preferred type of language. Such a result is again consistent with subjects’ attitudinal choices as demonstrated in Section 3.1, where such usage receives the highest degree of acceptability among various levels of the use of English.

By contrast, for local products, Chinese copy mixed with simple English words representing a trendy fashion and featuring cuteness has become the second best advertising copy, next to monolingual Chinese copy.

The cross-referencing analysis of all the above results suggests that for the majority of the general public in Taiwan, who are not proficient in English or who are equipped with a minimal level of English literacy, to process the information contained in the advertisements using only English may pose language and psychological barriers to them. However, if English is mixed to a limited extent and the English vocabulary used is either very simple such as “happy” or “easy” or very professional such as technical terms, people feel secure with and attracted to these advertisements. Thus, on the one hand, they have less difficulty in processing the information contained in the advertisements. On the other hand, they can enjoy the socio-psychological effects brought about by the use of English.

In short, all the cross-referenced pieces of evidence presented above indicate that the socio-psychological effects English is capable of generating correlate with different types of advertising copy and different types of advertised products. On an underlying level, the interplay of the former two factors and readers’ language barrier of English, as witnessed by their psychological barrier in processing lengthy English text and difficult words, contributes to the readers’ attitudinal preferences.

4. Conclusion

A copywriter comments about marketing in Ecuador, “people still think that what comes from abroad is better, and if it’s in English—it’s even better” (Alm 2003:152). This quote indicates how English, as the unprecedented global marketing language, has cast its glamour on consumers across different languages and cultures. As witnessed by the findings of this study, English is overwhelmingly popular in Taiwan, although this result contrasts sharply with the observation made by Gerritsen et al. that Dutch subjects show a negative attitude toward the English used in TV commercials (2000:17).

By exploring consumers’ underlying psychology, consistent findings of the present research show that English conveys the following socio-psychological effects to the general public in Taiwan: attention-getting, internationalism, premium quality, authenticity, and the trendy taste of the younger generation. However, specific socio-psychological effects of English mixing correlate with different extents of English mixing in advertising copy and advertised product type. Furthermore, this appeal of English is culturally and linguistically confined.

In conclusion, this research answers two of the questions raised by Hornikx et al. (2010:182) concerning to what extent the use of English is an effective choice, namely, how well it is received by consumers, and how the degree of difficulty of the English use affects consumers’ preference for English, a research issue receiving little attention. It further answers the question Martin (2002:399) posits regarding how consumers’ attitudes toward code-mixing may be determined by the proportion of English in code-mixed advertising copy. It confirms Bhatia & Ritchie’s observation of the unduplicated role of English in rendering the socio-psychological functions unique to English in global advertising (2006:518). In addition, it provides empirical sociolinguistic evidence of how consumers respond to global marketing strategies of mixing English employed by advertisers.

Overall, the present study, by investigating consumers’ attitudes toward English mixing in advertising, can be added to a growing body of research pointing to “universals in the use of English in non-English contexts” (Bhatia 1992, 2000, 2001, 2006, quoted from Baumgardner 2008:44). Finally, more empirical research is recommended to assess consumer’s attitudes toward English mixing across cultures. This will provide insights into whether linguistic and cultural variations may affect the socio-psychological effects English can transmit to consumers.

Appendix 1. Demographic profile of the surveyed subjects

Frequency Percentage

TOTAL NUMBER OF SUBJECTS 425

VARIABLES GENDER Male 189 44.5 Female 236 55.5 AGE 14-20 70 16.5 21-30 129 30.4 31-40 93 21.9 41-50 103 24.2 51-60 20 4.7 61-70 5 1.9 71-80 4 0.9 81-90 1 0.2 LEVEL OF EDUCATION Junior high 14 3.3 Senior high 80 18.8 Junior college 35 8.2

Technical (Vocational) college 57 13.4

College and university 161 37.9

Master’s Degree 65 15.3 Doctoral Degree 13 3 OCCUPATION* Students 98 23 Teachers 64 15 Businessmen 40 9.4 Government employees 32 7.5 Service sector 20 4.7 Homemakers 18 4.2

Insurance salesmen/real estate agents 18 4.2 Journalists/magazine editors/mass

media workers 12 2.8

Electronics/information engineers 11 2.6

Policemen 4 0.09

Dentists/doctors/psychiatrists 4 0.09

Dialects spoken at home

Mandarin Chinese 398 55.7

Southern Min 265 37.1

Hakka 34 4.8

Other dialects 17 2.4

Note: Among the 49 occupations surveyed in this study, only those with four or more subjects are listed in the table.

Appendix 2. The questionnaire design 敬啟者: 這是一份關於台灣媒體廣告上使用英文之現象的學術問卷調查,感謝您撥冗作答。 現今在台灣雜誌、報紙媒體上常會出現使用英文的現象。本問卷之目的希望瞭解:(1)一般讀者對於媒體廣告上使 用英文之態度、看法。(2)有何潛在因素可能影響到讀者對於媒體廣告上使用英文之接受程度。 在以下的問卷中,您將會先看到 2 頁的平面廣告,請瀏覽後再回答。不論您是否懂英文或喜歡英文,相信您的忠 實回答將有助於我們瞭解此一議題之全貌。再次感激您的合作。 國立台灣大學外文系副教授 胥嘉陵

一. 性 別________ 年 齡________ 教育程度________ 職 業________ 如(亦)為學生, 請填就讀學校 __________________________ 科系_________ 級別_________ 在家說何種方言? (可複選) □國語 □閩南 □客家話 □其他(請說明)________ 貳. A. 1. 您對國外產品廣告全部以英文刊登, 如圖 1, 之接受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 2. 您個人對此類廣告之看法? (可複選) □很能引人注意 □予人好感 □無所謂 □純粹宣傳花招, 無新意 □只是將國外廣告原版移植臺灣, 無中文翻譯, 不尊重臺灣讀者 □因英文是國際語言, 使用英文予人國際化感受 □其他(請說明)_______________________________________________________ 3. 全版英文廣告對您而言具有哪些吸引力?下列有 8 大項原因, 您可複選這 些原因, 另外如果您勾出某一大項, 其中之小項原因亦請您選出. (a) □ 產品具未來性及創新性, 例如: □前瞻性 □進步性 請舉一類產品為例說明(可參見問題一之選項): ______________________________ (b) □ 產品含英美文化代表之意義, 例如: □現代化 □基督教文化 □獨立自由之價值觀 □西化 請舉一類產品為例說明(可參見問題一之選項): ______________________________ (c) □ 產品予人國際化及規格統一化之印象, 例如: □規格統一化 □產品認証 □可靠性 請舉一類產品為例說明(可參見問題一之選項): ______________________________ (d) □ 產品予人理性與客觀感, 例如: □以科學為訴求 □解決問題 請舉一類產品為例說明(可參見問題一之選項): ______________________________ (e) □ 產品予人能力卓越之信賴感, 例如: □高效率有組織 □高品質 □功能強大 □安全性 請舉一類產品說明(可參見問題一之選項): __________________________________ (f) □ 產品予人複雜精密之設計感, 例如: □優雅 □風格 □品味 □稀有 請舉一類產品說明(可參見問題一之選項): __________________________________ (g) □ 產品予人健身, 強健體魄之印象, 例如: □予人性感體魄的聯想 □自我提昇 □健康生活品質 請舉一類產品說明(可參見問題一之選項): __________________________________ (h) □ 其他, 例如: ____________________________________________________ 請舉一類產品說明(可參見問題一之選項): __________________________________ B. 1. 您對廣告中中文夾雜許多英文術語, 如圖 2, 或 DVD, CD, RAM 等現象之接受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 2. 您對此類廣告之看法如何?(可複選) □因這些術語很難翻成中文, 所以使用英文原文是必然現象 □雖曰英文術語之使用不可避免, 但仍希望能多些標準化本土翻譯 □這些術語應全翻成中文, 使之本土化 □這些術語之使用予人權威信賴感 □無所謂 □其他 (註:如果問題二第 3 小題之選項原因也適合您, 請您直接參照填寫) _____________________________________________________________________ 3. 您覺得這類型廣告較適合何種產品?請舉一例說明 _____________________________________________________________________ C.

1. 您對中文廣告中夾雜兩三個英文單字如「smart, super, sorry, yes, no, ok」或夾雜片語如「VIP, summer sale」等之

接受程度為何?(請參考圖 3) (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 2. 您對此類廣告之看法如何?(可複選) □使用英文是流行趨勢, 對年輕族群很有吸引力 □引人注目 □很有創意, 俏皮活潑 □產品予人國際化及規格統一化之印象 □產品予人複雜精密之設計感 □產品予人理性與客觀感 □產品予人能力卓越之信賴感 □產品具未來性及創新性 □產品含英美文化代表之意義 □產品予人健身, 強健體魄之印象

□賣弄英文 □崇洋媚外 □很俗氣 □很本土 □純粹宣傳花招, 不足可取 □中英夾雜, 不中不西, 不倫不類 □一時風尚而已, 不可能長久使用 □其他________________________ 3. 您覺得此類廣告適合何種產品, 請舉一例說明 _____________________________________________________________________ 4.

(a) 在此類廣告中, 如果夾雜之英文單字以形容詞出現, 例如:「創業很 Easy 加盟更 Happy」、「基隆到那霸最 High 歡 樂價」、「名牌家電說 Free 就是 Free」, 對此類廣告句子的接受程度為何? (請單選)

□完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由

_____________________________________________________________________

(b) 如果夾雜之英文單字以名詞出現, 例如:「兩性發燒 Time」、「既然擁有 Power, 做的決定也該是有 Power 的」、 「凱悅飯店般大 Lobby, 到新光三越站前店 Shopping」、「除了 Love, 懷孕的妳還需要溫柔的“Dove”」, 您對此 類廣告句子的接受程度為何? (請單選)

□完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由

_____________________________________________________________________

(c) 如果夾雜之英文單字以動詞出現, 例如:「會笑的顏色 Show 出陽光般的妳」、「心靈重建, 從 Think 開始」、「新世 紀 Come 頭皮屑 Go」、「像您可以 Download 網路的美食情報或用掃描器記錄報章雜誌美食報導」, 您對此類廣告 句子的接受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由 _____________________________________________________________________ (d) 如果夾雜之英文單字以介係詞出現, 例如: 「50% off」、「台北 v.s 紐約」、「隔離飾底乳 v.s.遮暇筆」, 您對此類廣 告句子的接受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由 _____________________________________________________________________ (e) 如果夾雜之英文單字以連接詞出現, 例如:「訂位十五人以上贈 8 吋生日蛋糕 or 雞尾酒」、「新航獎勵計劃, 即送 上香港 or 東京 or 新加坡經濟艙來回免費機票」, 您對此類廣告的接受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由 _____________________________________________________________________ (f) 如果夾雜之英文單字以副詞出現, 例如:「達美樂炸雞 Very 脆、Very 嫩」 ,您對此類廣告的接受程度為何? (請單 選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由 _____________________________________________________________________ 請問是否從電視中看過以上的廣告?□是 □否

(g) 如果夾雜之英文以句子出現, 例如:「青少年保健宣導巡迴活動. Come On Baby」、「Enjoy life, so easy」、「中國時 報消費快樂行. Let’s Go」, 您對此類廣告句子的接受程度為何? (請單選)

□完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由

_____________________________________________________________________ D.

1. 您對中文廣告中出現英文口號, 例如:「Just call me. Be happy」、「Just Do It」、「Trust me, You can make it」之接 受程度為何? (請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 不論選擇為何, 請說明理由 _____________________________________________________________________ 2. 如果您可以接受此類廣告方式, 您覺得那些類產品適合如此刊登, 請舉一例說明 ______________________________________________________________ E. 1. (a) 您基本上是否同意如果產品為時尚, 現代科技, 精品, 或國外之產品則英文之出現會增進您對產品之信心? □是 □否 □其他 (請說明: ____________________________________) 不論選擇為何, 請說明原因 _____________________________________________________________________ (b) 此類廣告英文字數愈多者愈會增進您對廣告產品之信心? □是 □否 □其他 (請說明: ____________________________________) 不論選擇為何, 請說明原因 _____________________________________________________________________ 2.

□是 □否 □其他 (請說明: ____________________________________) 不論選擇為何, 請說明原因 _____________________________________________________________________ (b) 此類廣告英文字數愈多者愈會增進您對廣告產品之信心? □是 □否 □其他 (請說明: ____________________________________) 不論選擇為何, 請說明原因 _____________________________________________________________________ F. 1. 如果是中國傳統本土之產品, 如食品之肉粽, 豆漿, 中藥, 中醫, 旗袍使用英文產品名稱, 口號, 或說明, 您的接 受程度為何?(請單選) □完全接受 □可以接受 □無所謂 □難以接受 □完全不能接受 2. 您對這種可能性之看法如何? □有助產品國際化 □樂觀其成(請說明原因_______________________________________________) □這類傳統產品跟英文之使用非常不搭調(請說明原因_____________________) □很難接受(請說明原因_______________________________________________) □其他(請說明: ____________________________________________________________________) G.

1. 在廣告中您是否發現過夾雜之英文有拼字或文法使用錯誤之情況, 如圖 4 ,「Roaming Beer Around The Word」 應為 Roaming Around in The World of Beer, 如圖 5, 「Enableing The Disable」應為 Enabling The Disabled, 「Grand Open」應為 Grand Opening?

□是 □否 □看不出來 2. 如果發現類似以上英文出錯之情況, 是否會影響到您對於這類廣告之接受程度? □否(請說明理由_____________________________________________________) □是(請說明如何影響_________________________________________________) H. 1. 廣告中英文用字之多寡, 是否會影響到您對這類廣告閱讀之興趣或接受程度? □否(請說明原因_____________________________________________________) □是(請說明如何影響_________________________________________________) 2. 廣告中英文用字之難易度, 例如, 出現不認識或困難之英文廣告詞, 如圖 6 中 unassailable beauty 之字眼之使用, 是否會影響到您對這類廣告繼續閱讀之興趣或接受程度?(可複選) □不會(請說明原因__________________________________________________) □無所謂 □會(請說明如何影響________________________________________________) □反而會增加我對這廣告產品的信心, 強化其為高級產品的印象 □比起平淡無奇之英文用字, 也許這類用字反而會勾起我的好奇心 (請說明如何引起好奇心_________________________________________) □其他(請說明______________________________________________________) I. 您覺得媒體廣告中, 不論是國外或本國產品使用英文是(可複選) □使臺灣國際化之方法 □國際潮流所趨, 順其自然 □崇洋媚外, 應該禁止廣告中英文之使用 □無所謂 □只是宣傳手法,無傷大雅 □其他(請說明_______________________________________________________) J. 如果產品為國外製造者則何種廣告型式表達效果最佳? □全部以英文刊登 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文術語 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文單字 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文句子 □全部以中文刊登 K. 如果產品為國內製造者則何種廣告型式表達效果最佳? □全部以英文刊登 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文術語 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文單字 □以中文為主, 夾雜英文句子 □全部以中文刊登