Social Support and Depressive Symptoms Among Displaced

Older Adults Following the 1999 Taiwan Earthquake

Chie Watanabe,

1

,4

Junko Okumura,

2

Tai-Yuan Chiu,

3

and Susumu Wakai

2

This longitudinal study examines changes in depressive symptoms among displaced older Taiwanese adults (N= 54, M = 68 years), and the impact of various social supports for them at between 6 and 12 months after an earthquake. The average depression score between 6 and 12 months follow-ing the earthquake was unchanged and kept high score. Child and extended family support levels related to depressive symptoms after 6 months. In contrast, after 12 months, significant factors asso-ciated with a lessening of the depressive symptoms were social support from the extended family and neighbors, and social participation. Intervention to promote increased social networks and social par-ticipation, within their new environment in a temporary community, is highly recommended for older adults.

KEY WORDS: older adults; displaced people; depression; natural disaster; Taiwan.

The Taiwan Chi-Chi earthquake magnitude 7.3 on Richter Scale struck central Taiwan at 1:47 a.m. on September 21, 1999. The death toll was 2,471 with 11,305 injured. According to national statistics, 4,700 families were living in temporary housing 5 months after the earth-quake (Department of Accounting and Statistics, 2000).

It is often reported that older adults are particularly vulnerable to the negative psychological effects of disas-ter (Phifer & Norris, 1989; Raphael, 1986) and that re-located people are more distressed than other survivors (Bland et al., 1997; Gleser, Green, & Winget, 1981). Such findings suggest that older relocatees may be an espe-cially important population for research and intervention.

1Department of Social Gerontology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

2Department of International Community Health, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

3Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taiwan.

4To whom correspondence should be addressed at Department of Social Gerontology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan; e-mail: fwnc9944@ mb.infoweb.ne.jp.

After the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Japan, about 40% of older families who were accommodated in tem-porary housing found that reconstructing new relation-ships was difficult for them after the loss of lifelong communities (Tanida, 1996). Kaniasty and Norris (1993) reported that the direct impact of disaster, that of per-sonal loss, had an intense but usually a short-term effect on older adults’ depressive symptoms. In contrast, com-munity destruction and loss of social support systems as-sociated with the disaster created long-term psychological distress.

Several studies have found that social support lessens the impact of traumatic stress (Bolin & Klenow, 1983; Tyler & Hoyt, 2000). However, to be used, the support must be of an appropriate form from an appropriate source (e.g., Cohen & Mckay, 1984). According to Kaniasty and Norris’s study on depression at recovery phase after dis-aster, only nonkin support and social embeddedness were significantly related to depression (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993). The present study examined the impact of var-ied sources of postdisaster social support on depression, longitudinally, among displaced old adults in an Oriental society.

63

Method

Participants

Ju-Shan town situated in Nan-Tou county (central Taiwan), was selected as the study site. The city was se-lected because it was severely damaged by the earthquake and the proportion of elderly population was relatively high compared with other areas. There was a 0.18% mor-tality rate attributed to the earthquake in this community (Department of Accounting and Statistics, 2000). For the following 2 months in Ju-Shan, 125 temporary houses were built for those who lost their homes following the earthquake. One year later, 312 displaced people were still living in them.

The participants were all individuals over 55 years old who had been evacuated and were living in tempo-rary housing (displaced group). A comparison group of similarly-aged adults was randomly selected from the area adjacent to the temporary housing.

In April 2000, 6 months postearthquake; data were collected from 56 displaced older adults and 48 nondis-placed ones. The second phase of data collection was con-ducted during September and October, 12 months postearthquake. Because half of the original nondisplaced participants moved to live with their families or relatives before the initiation of phase 2, no follow-up was con-ducted of the comparison group. Of the displaced group, 54 (96%) were successfully re-interviewed. Two partici-pants had moved out of temporary housing. Mean age of the 54 participants was 68.1 years (SD = 9.5). Sixteen participants (29.6%) were living alone. Their religion was either Buddhism (25.9%) or traditional belief (Chinese folk-religion; 59.3%). In phase 2, 12 (22.5%) of the 54 respondents, had started reconstructing their houses, and 9 (16.7%) decided to move to another place to live with their children. Thirty-three respondents (61.1%) did not have firm plans for their future housing. Before interview-ing them, we asked family members if participants had any symptoms like dementia or any psychiatric disease history before the earthquake. If the participants lived alone, we asked their primary health nurse working in their commu-nity. No cases were excluded from this study on the basis of previous disorders.

Procedure

Questionnaires were developed in Mandarin Chinese. Face-to-face interviews following a structured questionnaire were carried out in participants’ homes. The interviews were done by one of the authors and

one local interviewer who was trained a day prior to the survey.

Instruments

Resource Loss

The questionnaire included measures of personal loss (death or severe injury experienced by family or close friends), house loss (totally or partially), social activity loss (including working status), physical health impair-ment, and financial loss. These questions were answered in a form of “yes” or “no.”

Social Support

Levels of social support were measured using the So-cial Support Scale (Noguchi, 1998) that has been used ex-tensively to measure perceived social support among older people in Japan. The Cronbach’s alpha of the original ver-sion was .89. The scale was translated from Japanese to Chinese and confirmed by back translation. The scale has 12 items and three dimensions: emotional, instrumental, and negative supports. Five sources of support were as-sessed: spouse, child living with participant (coresident child), child living separately from participant (nonres-ident child), extended family, and neighborhoods. The total support scores, which included emotional and instrumental support, were analyzed as an independent variable. The social support score ranged from 0 to 8 points.

Social participation was examined by seeking re-sponses regarding working status (whether working or not and type of job), the number of social activities pated in, and their frequency (number of times of partici-pating in a week).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) developed by Zung (1965). The SDS has 20 items to quantify the severity of current depressive symptoms. The Chinese version has been used in several studies, and its validity established (Leung, Lue, Lee, & Tang, 1998). Based on the pretest results, we had to delete two items from the original SDS: (1) loss of sex-ual desire and (2) suicidal rumination. When we conducted pretests on 20 participants, most of them strongly objected to the item on loss of sexual desire, in spite of assurances that their privacy was protected. As Leung et al. (1998)

Table 1. Depressive Score and Social Support, Social Participation by Phase (N= 54) Phase 1a Phase 2a M SD M SD Depressive scoreb 41.4 7.64 40.9 6.42 Social support Spouse supportc 2.26 3.21 2.37 3.39 Coresident child supportc 2.69 3.50 2.41 3.46 Nonresident child supportc 3.89 3.26 4.39 3.21 Extend family supportc 1.94 2.76 2.54 2.63 Neighbor support 1.50 1.97 3.44 2.06***

n % n %

Social participationd

Yes 18 32.1 20 37.0

No 38 67.9 34 63.0

Note. Depressive score was tested by paired t test and the social support

scores were done by Wilcoxson signed rank (paired) test because of differences in their distribution.

aPhase 1 : 6 months after the earthquake; phase 2 : 12 months after the earthquake.

bDepressive score: modified SDS score.

cIf there were no support providers, it was scored as “0.”

dIf the respondent participated in any social activities or was working, it was defined as “yes.”

*** p< .001.

indicated, Chinese people, especially older adults, perceive sex-related issues as something shameful, and they are embarrassed by speaking about sex to others. Also, some respondents were very nervous and worried about being a burden for the family. Therefore, it was considered ethically unacceptable to ask, “I feel that oth-ers would be better off if I were dead.” The coefficient alpha of the modified SDS Chinese version was .85.

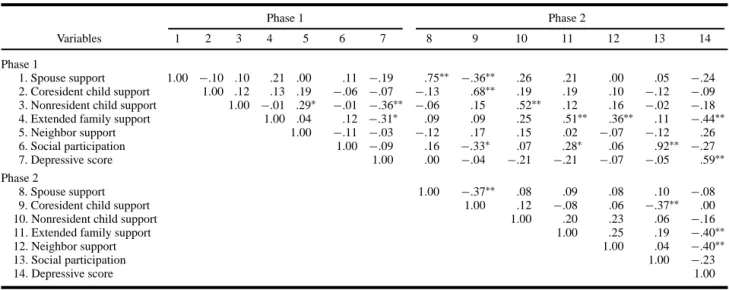

Table 2. Zero Order Speaman’s Rank Correlations Among Social Support and Depression Measures (N= 54)

Phase 1 Phase 2

Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Phase 1

1. Spouse support 1.00 −.10 .10 .21 .00 .11 −.19 .75∗∗ −.36∗∗ .26 .21 .00 .05 −.24 2. Coresident child support 1.00 .12 .13 .19 −.06 −.07 −.13 .68∗∗ .19 .19 .10 −.12 −.09 3. Nonresident child support 1.00 −.01 .29∗ −.01 −.36∗∗ −.06 .15 .52∗∗ .12 .16 −.02 −.18 4. Extended family support 1.00 .04 .12 −.31∗ .09 .09 .25 .51∗∗ .36∗∗ .11 −.44∗∗

5. Neighbor support 1.00 −.11 −.03 −.12 .17 .15 .02 −.07 −.12 .26

6. Social participation 1.00 −.09 .16 −.33∗ .07 .28∗ .06 .92∗∗ −.27

7. Depressive score 1.00 .00 −.04 −.21 −.21 −.07 −.05 .59∗∗

Phase 2

8. Spouse support 1.00 −.37∗∗ .08 .09 .08 .10 −.08

9. Coresident child support 1.00 .12 −.08 .06 −.37∗∗ .00

10. Nonresident child support 1.00 .20 .23 .06 −.16

11. Extended family support 1.00 .25 .19 −.40∗∗

12. Neighbor support 1.00 .04 −.40∗∗

13. Social participation 1.00 −.23

14. Depressive score 1.00

∗p< .05.∗∗p< .01.

Results

Depressive Symptoms and Social Support by Phase

In phase 1, the data confirmed that the displaced group had significantly higher depressive symptoms than the nondisplaced group (M= 41.4, SD = 7.64 vs. M = 35.5, SD = 7.90), t(102) = 3.8, p < .001. The mean de-pressive scores of the displaced group at phases 1 and 2 were not significantly different from each other, t(53)< 1. At phase 2, the mean score of social support by neigh-bors was significantly higher than at phase 1 (Z = −4.25,

p< .001), although other levels of social supports did not

change (Table 1).

Relation Between Conditions Affected by the Earthquake and Depressive Symptoms

Of the resource loss variables, only personal loss was associated with a higher level of depressive symp-toms and this was true only at phase 1, t (52) = −2.22,

p< .05.

Relation Between Social Support and Depressive Symptoms by Phase

Table 2 shows the correlations between the social support measures and depressive symptoms. Table 3 presents the results of the partial correlation analysis by phase. At phase 1, correlations were adjusted for age and personal loss. Family supports, received from child

Table 3. Partial Correlations Among Social Support Measures and Depression Score (N= 54) Depressive score Phase 1a Phase 2b Phase 1 Spouse support −.21 −.17

Coresident child support −.28∗ −.18 Nonresident child support −.29∗ −.01 Extended family support −.34∗ −.45∗∗

Neighbor support .05 −.13

Social participation −.10 −.35∗ Phase 2

Spouse support −.16

Coresident child support −.01

Nonresident child support −.07

Extended family support −.34∗

Neighbor support −.45∗∗

Social participation −.31∗

aAdjusted for age and personal loss.

bAjusted for age, personal loss, and depressive score (phase 1).

∗p< .05.∗∗p< .01.

living with participant, child living separately, and ex-tended family were each negatively associated with de-pressive symptoms: the higher the level of family support, the lower the level of depressive symptoms.

At phase 2, correlations were also adjusted for the phase 1 depressive score. Levels of social support received from extended family and neighbors and social partici-pation were each negatively associated with the level of depressive symptoms. Contrary to the result at phase 1, support received from children was unrelated to the level of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

On average, depression scores did not change be-tween 6 and 12 months after the earthquake. Although we failed in following up with the nondisplaced group in phase 2, at phase 1 the depression scores of that group were significantly lower than those of displaced partici-pants. Also, as compared to the previous studies that de-termined depressive status of older adults by using a sim-ilar instrument (Leung et al., 1998; Lu, Liu, & Yu, 1998), these displaced older adults experienced depressive symp-toms for a longer period of time than older adults typically do in Taiwan. Considering these facts, we assumed that the experience of displacement challenged older adults’ recovery from disaster-related psychological distress.

According to Parker (1977), relocation after natural disasters may lead to disruption of familiar neighborhood networks and impairment of effective support networks.

Our study revealed that neighbor support increased sig-nificantly 6–12 months after the earthquake. We therefore think that it takes a certain time to develop support systems within temporary housing situations.

The benefits of social support varied across time and according to the source of support. In the short term (6-month postearthquake), higher levels of child and ex-tended family support were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, in the longer term (12-month postearthquake), higher levels of support by extended family and neighbors and social participation were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms. Antonucci (1985) indicated that the presence of family support does not necessarily have a substantially posi-tive impact, but its absence may be detrimental. Family support plays an important role in regulating and main-taining the standard of living (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993). Because family support has both instrumental and emo-tional functions, it would be essential for older adults to receive such support during the acute and early-recovery phases to meet their basic human needs. Family support is routinely observed as a filial obligation to elderly peo-ple in Taiwanese culture (Kao & Stuifbergen, 1999; Shyu, Archbold, & Imle, 1998). In Taiwan, the older population (65-year old and over) has been rapidly increasing. How-ever, family support systems have been fading out because the family structure has changed under “modernization” (Department of Accounting and Statistics, 1998). Such change makes it more difficult to provide appropriate sup-port to older victims at a community level and became a serious issue after the earthquake.

In contrast, social participation and social support by extended families and neighbors would play a more im-portant role in promoting mental health in later phases of recovery. By these supports, positive thinking and self-esteem are promoted, and victims can eventually attain better psychological status and well-being (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993). Also, the development of spontaneous sup-port systems within the community, such as social net-works of neighborhoods, homeowners’ associations, reli-gious groups, and social clubs is considered to empower the elderly and to reduce stress (Eynde & Veno, 1999). Similarly, an intervention to promote social networks and social participation in the temporary community for the older adults by relief organizations and local authorities is highly recommended so that the displaced older adults can attain better quality of life. In conclusion, although the sample size was not large enough to generalize the results, our longitudinal study suggests that it would be valuable to develop social support systems for older adults who must live in temporary communities following natural disasters.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Prof. Ichiro Kai, Dr Osamu Kunii, and Ms Hu-Shu-Hui for their helpful comments.

References

Antonucci, T. C. (1985). Personal characteristics, social support and social behavior. In R. H. Binstock & E. Shanas (Eds.), Handbook

of aging and social sciences (2nd ed., pp. 94–128). New York: Van

Nostrand Reinhold.

Bland, S. H., O’Leary, E. S., Farinaro, E., Jossa, F., Krogh, V., Violanti, J. M., et al. (1997). Social network disturbances and psychological distress following earthquake evacuation. Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease, 185, 188–194.

Bolin, R., & Klenow, D. J. (1983). Response of the elderly to disaster: An age-stratified analysis. International Journal of Aging and Human

Development, 16, 283–296.

Cohen, S., & Mckay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, J. E. Singer, & S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (pp. 253–268). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Department of Accounting and Statistics. (1998). The survey of status of

elderly population in Taiwan [Chinese]. Taipei: Ministry of Interior

of the Republic of China.

Department of Accounting and Statistics. (2000). The social aid and

placement of refugee in 921 big quake analysis [Chinese]. Taipei:

Ministry of Interior of the Republic of China.

Eynde, J. D., & Veno, A. (1999). Coping with disastrous events: An empowerment model of community healing. In R. Gist & B. Lubin (Eds.), Response to disaster: Psychosocial, community, and

eco-logical approaches (pp. 167–192). Philadelphia: Brunner Mazel.

Gleser, G., Green, B., & Winget, C. (1981). Prolonged psychosocial

effects of disaster: A study of Buffalo Creek. New York: Academic

Press.

Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (1993). A test of the social deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 64, 395–408.

Kao, H. F., & Stuifbergen, A. K. (1999). Family experiences related to the decision to institutionalize an elderly member in Taiwan. Social

Science and Medicine, 49, 1115–1123.

Leung, K. K., Lue, B. H., Lee, M. B., & Tang, L. Y. (1998). Screening of depression in patients with chronic medical diseases in a primary care setting. Family Practice, 15, 67–75.

Lu, C. H., Liu, C. Y., & Yu, C. Y. (1998). Depressive disorders among the Chinese elderly in a suburban community. Public Health Nursing,

15, 196–200.

Noguchi, Y. (1998). Social supports for the elderly people: Concept and measurement [Japanese]. Shakai-Rounengaku, 34, 37–48. Parker, G. (1977). Cyclone Tracy and Darwin evacuees: On the

restora-tion of the species. British Journal of Psychiatry, 130, 548– 555.

Phifer, J. F., & Norris, F. H. (1989). Psychological symptoms in older adults following natural disaster: Nature, timing, duration, and course. Journal of Gerontology, 44, 207–217.

Raphael, B. (1986). When disaster strikes. How individuals and

commu-nities cope with catastrophe. New York: Basic Books.

Shyu, Y. L., Archbold, P. G., & Imle, M. (1998). Finding a balance point: A process central to understanding family care giving in Taiwanese families. Research in Nursing and Health, 21, 261–270. Tanida, N. (1996). What happened to elderly people in the great Hanshin

earthquake? BMJ, 313, 1133–1135.

Tyler, K., & Hoyt, D. R. (2000). The effects of an acute stressor on depressive symptoms among older adults: The moderating effects of social support and age. Research on Aging, 22, 143–164. Zung, W. W. K. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of