國 立 交 通 大 學

科技管理研究所

碩 士 論 文

創投業與經濟發展的關係

‐

以台灣與土耳其為例

Venture Capital, a pass to prosperity: The Cases of

Taiwan and Turkey

研 究 生 :穆特魯

指導教授:虞孝成 教授

創投業與經濟發展的關係

‐

以台灣與土耳其為例

Venture Capital, a pass to prosperity: The Cases of

Taiwan and Turkey

研 究生:穆特魯

Student: Hasan Mutlu

指導教授:虞孝成 教授

Advisor: Dr. Hsiao-Cheng Yu

國 立 交 通 大 學

科 技 管 理 研 究 所

碩 士 論 文

A thesis

Submitted to the Institute of Management of Technology College of Management

National Chiao Tung University In partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

Master of Business Administration. June 2007

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

Venture Capital, a pass to prosperity: The Cases of

Taiwan and Turkey

Student: Hasan Mutlu Advisor: Dr. Hsiao-Cheng Yu

Institute of Management of Technology National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

What brings prosperity is a complex question and has many dimensions; venture capital is a factor that affects it and this study is focused on how venture capital industry helps a nation to archive prosperity. The main advantage of venture capital has been providing the necessary assistance to entrepreneurs, whom Porter (1990) places in the heart of a nation’s competitive advantage.

Some countries had successfully developed venture capital industries and utilized it for the benefit of their economy. The statistics show that venture capital backed companies contributed a significant amount to the U.S economy. Taiwan whom copied the Venture Capital structure of USA has also developed a strong Venture Capital industry. Taiwanese Venture Capital backed companies had grown to be one of the biggest companies in the country and they contribute significant amount both to the GDP and employment of the country. However, not every country is successful to establish their venture capital industries. There have been numerous studies conducted to understand the difference of venture capital development between countries. This study aims to utilize the previous studies to determine which factors affect the level of venture capital in a country, and in the light of these factors to understand the difference between the diverse development path of venture capital industries in Turkey and Taiwan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Yu for his motivation and helping me to finish my thesis.

I would also like to thank my parents for raising me up and for their continuous support throughout my life. Knowing and feeling that they are always there makes everything easier. I would like to thank my brother as well to force me to apply for the scholarship, so that I could write this thesis to finish my MBA degree.

Finally, I would like to thank Yin Ling for her support, motivation and suggestions, so that I wrote the thesis faster.

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT ... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... ii Figures ... v Tables... vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION...‐ 1 ‐ 1.1 Motivation...‐ 1 ‐ 1.2 Research Methodology ...‐ 4 ‐ CHAPTER 2. VC’S CONTRIBUTION TO PROSPERITY ...‐ 5 ‐ 2.1 Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth ...‐ 5 ‐ 2.2 Venture Capital as a facilitator ...‐ 8 ‐ 2.3 Venture Capital Contribution to USA Economy...‐ 11 ‐ 2.4 Venture Capital Contributions to Taiwan’s GDP and Employment Market ...‐ 15 ‐ CHAPTER 3. VC INDUSTRY IN TAIWAN ...‐ 18 ‐ 3.1. History of Taiwan VC industry...‐ 18 ‐ 3.2. Current trends and situation of VC...‐ 19 ‐ Fundraising ...‐ 19 ‐ Investments...‐ 20 ‐ Exits ...‐ 24 ‐ 3.3. VC regulations in Taiwan ...‐ 26 ‐ CHAPTER 4. VENTURE CAPITAL IN TURKEY ...‐ 32 ‐ 4.1 History of VC in Turkey ...‐ 32 ‐Actors in the Turkish Venture Capital Market ...‐ 33 ‐ 4.3 Regulations concerning VC ...‐ 34 ‐ CHAPTER 5. LITERATURE REVIEW OF FACTORS THAT AFFECT VC...‐ 37 ‐ 5.1 VC driving forces ...‐ 37 ‐ 5.2 Additional Factors on Demand Side ...‐ 47 ‐ 5.2.1 Industry Structure ...‐ 50 ‐ 5.2.2 Cultural Influence ...‐ 51 ‐ CHAPTER 6. COMPARING THE FACTORS THAT AFFECT VC IN TURKEY AND TAIWAN ...‐ 55 ‐ 6.1 Exit Opportunities ...‐ 55 ‐ 6.2 Labor Market Rigidity...‐ 58 ‐ 6.3 Economic Variables...‐ 59 ‐ 6.4 Innovation Capacity ...‐ 60 ‐ 6. 5 Government Policy and Support...‐ 62 ‐ 6.6 Industry Structure ...‐ 63 ‐ 6.7 Cultural Influences ...‐ 66 ‐ 7. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ...‐ 69 ‐ 8. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...‐ 73 ‐ REFERENCES...‐ 76 ‐

Figures

Figure 1: Comparison of VC Industry, Taiwan and Turkey ...‐ 3 ‐ Figure 2: Research Approach...‐ 4 ‐ Figure 3: VC Backed Companies Crate Job and Wealth ...‐ 13 ‐ Figure 4: Wage Growth in Venture Intensive Industries Vs. Nonventure Intensive Industries USA ...‐ 14 ‐ Figure 5: Newly Raised Capital and Accumulated Total Capital, 1984‐2005 ...‐ 20 ‐ Figure 6: Number and Amount of Investment, 1996‐2005...‐ 21 ‐ Figure 7: Accumulated Venture Capital Investments by Industry & Amount of Investment, 1984‐2005...‐ 22 ‐ Figure 8: Accumulated Venture Capital Investments by Stage & Number of Investments, 1984‐2005...‐ 23 ‐ Figure 9: Taiwan’s IPO Market & Exits, 2005 ...‐ 25 ‐ Figure 10: The Theoretical Framework of variables to be studied ...‐ 47 ‐ Figure 11: Stock Market Performance; Turkey and Taiwan...‐ 56 ‐ Figure 12: Cultural Dimensions, Turkey and Taiwan...‐ 66 ‐ Figure 13: Findings...‐ 72 ‐

Tables

Table 1: Economic Benefits of VC Backed Companies USA...‐ 12 ‐ Table 2: Capital Size of Venture‐Backed Listed Companies in Taiwan, 2005...‐ 15 ‐ Table 3: Taiwan Venture Capital Industry’s Contribution to Local Job Market, 2005 ...‐ 17 ‐ Table 4: Taiwan Venture Capital Industry’s Contribution to National Income, 2005 ...‐ 17 ‐ Table 5: The Previous studies and the variables that they have studied...‐ 46 ‐ Table 6: Taiwan Venture‐Backed IPOs by Industry, 2005 ...‐ 57 ‐ Table 7: Labor Rigidity Index ...‐ 58 ‐ Table 8: GDP Growth, Taiwan and Turkey...‐ 59 ‐ Table 9: Interest Rates, Turkey and Taiwan ...‐ 60 ‐ Table 10: Gross domestic expenditure on R&D, Turkey and Taiwan...‐ 61 ‐ Table 11: Total Number of Patents, Turkey and Taiwan...‐ 61 ‐ Table 12: Weight of Industry Sectors, Turkey ...‐ 64 ‐ Table 13: Weight of Industry Sectors, Taiwan...‐ 65 ‐ Table 14: Self Employment, Turkey and Taiwan ...‐ 67 ‐CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the life on earth, the only rule has been competition; the effort of being better and prevail. This is the golden rule of survival. Many creatures evolved into different abilities to be better off in this fierce competition. They developed different abilities which will make them more competent. Similar to all live beings, human being is also at the same race. Everybody is on a chase to make their lives better. Likewise in personal case, the nations are also in a competition for well being of their people. Each nation has the desire to reach prosperity and provide the best to its citizens. The nations have also developed different strategies to reach this goal. Even though, there are many reasons to be explored to understand a nation’s level of prosperity, and what brings prosperity is a complex question, it is shown by many studies that venture capital (VC) is a factor that influences nations’ competitive advantage and helps to reach prosperity.

1.1 Motivation

The OECD Growth Project recommended increasing access to high-risk finance to stimulate firm creation and entrepreneurship, one of the main drivers of growth and productivity performance (OECD, 2001). However, countries have had varied success in channeling funds, particularly venture capital, to early-stage firms in high-growth sectors. On the supply side, this may be due to a lack of funds, risk-averse attitudes and/or the absence of equity investment culture. On the demand side, there may not be a sufficient pool of entrepreneurs and investment-ready small firms. Countries need to first determine where financing gaps

exist and assess all possible supply and demand factors which may be contributing to market failures in terms of access to venture capital.

The United States has the oldest and one of the largest venture capital markets in the world. Not only does the United States have an entrepreneurial and risk-taking culture, small firms have benefited from a continuum of venture finance provided by business angels, private funds and public equity schemes. But US venture funding, as in most other OECD countries, has suffered from the recent global downturn in technology and financial markets. The United States and other OECD countries need to re-evaluate and redirect government venture capital initiatives to assure their continuing contributions as market conditions change. And as the market becomes more global, countries need to enhance their ties to international venture capital flows, which are a source of both finance and expertise (OECD, 2004).

Another vivid example of a success story is Taiwan Venture Capital Industry. According to Taiwan Venture Capital Association (tvca, 2006), Taiwan’s venture capital industry is the third most active venture capital market in the world behind the US and Israel. Many national governments, including those of Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Israel, Germany, Switzerland, France, and China are highly interested in the successful venture capital model of Taiwan’s venture capital. The government-led development of Taiwan’s venture capital industry has been the subject of many studies and discussions in many Asia Pacific countries such as China, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand and others seeking to develop their own venture capital industries through the implementation of incentive systems (tvca, 2006). Taiwan venture capital industry supported companies that became one of the biggest in the country and they later successfully went public including D-Link, United Semiconductor Corp., Acer, ZyXEL, Macronix, Inventec, TSMC, Winbond, Accton, MediaTek, BenQ, Altek, and Radiant Opto-Electronics.

On the other hand, Turkey had been away from the trend going on about venture capital. The following figure shows how Turkey is legging in this industry comparing to Taiwan.

Figure 1: Comparison of VC Industry, Taiwan and Turkey

Source: TVCA (2006), CMB Turkey, VC Company Portfolios

Even though Turkey is taking measures to adapt its economy to global competition, there is no effort observed to support venture capital industry. The motivation for this thesis comes from the unique success of Taiwanese venture capital industry and whether it can be a model for Turkey. Especially, since the banking sector is the dominant financial sector in Turkey, problems encountered led to great difficulties in industry that depend on bank credits and guarantees for their operations. Since the crises, access to finance has been a major problem especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Venture capital might be a solution to this problem encountered by SMEs in Turkey. This thesis will try to understand the differences between two countries regarding the factors that effect venture capital formation, and then conclude the results that affect the difference between two countries to

suggest ways for Turkish government to improve the current situation of venture capital industry in Turkey.

1.2 Research Methodology

First, the contribution of venture capital will be introduced using previous studies from the literature, and then statistical data will be demonstrated to support the literature. To understand the main driving forces of venture capital, the previous studies will be brought in. Then, according to the findings from the literature, the comparison of two countries Turkey and Taiwan will take place. The secondary data will be used to analyze the variables that are found in literature review. The following figure summarizes the research approach.

Figure 2: Research Approach

Conclusion

Data Gathering: Yearbooks, Journals, Websites of VCs in Turkey, Statistical Institutes Analysis of data according to literature review Literature Review: Journals, Thesis Dissertations, and ReportsCHAPTER 2. VC’S CONTRIBUTION TO PROSPERITY

2.1 Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth

Entrepreneurship is a multidimensional concept, the definition of which depends largely on the focus of the research undertaken. An entrepreneur can fulfill different functions (Fiet, 1996). Hébert and Link (1989) distinguish between the supply of financial capital, innovation, allocation of resources among alternative uses and decision-making. They use the following definition of an entrepreneur which encompasses the various functions: "the entrepreneur is someone who specializes in taking responsibility for and making judgmental decisions that affect the location, form, and the use of goods, resources or institutions" (Hébert and Link, 1989). Wennekers and Thurik (1999) give an alternative definition in which they focus on the perception of new economic opportunities and the subsequent introduction of new ideas in the market. These definitions from the world of economics differ from those in the management world. In their description of the difference between entrepreneurs and managers, Sahlman and Stevenson (1991) use the following definition: "entrepreneurship is a way of managing that involves pursuing opportunity without regard to the resources currently controlled. Entrepreneurs identify opportunities, assemble required resources, implement a practical action plan, and harvest the reward in a timely, flexible way". (Verheul et al., 2001)

Many studies have shown that there is a link between entrepreneurship and development. The question of why some nations are rich and others are poor has been at the center of economic debate for over two centuries. While some dominated discussion of economic development focused on and emphasized the importance of such factors as foreign aid and government planning, it is now widely agreed that the entrepreneur is the prime driver of economic progress (Kasper and Streit, 1998; Leff, 1979).

Even though it is difficult to measure the direct effect of entrepreneurship, intermediate variables or linkages can be used to explain how entrepreneurship influences economic development. Moreover, there is no universal accepted theory of development Leibenstein (1968) point to two important elements in the process. First, per capita income growth requires shifts from less productive to more productive techniques per worker, the creation or adoption of new commodities, new materials, new markets, new organizational forms, the creation of new skills, and the accumulation of new knowledge. Second, part of the process is the interaction between the creation of economic capacity growth and demand growth takes places. The entrepreneur as a gap-filler and input-completer is probably the prime mover of the capacity creation part of these elements of the growth process.

On the one hand, when entrepreneurs see opportunities in the service sector that give them higher returns, they move to this sector accordingly. Moreover, some entrepreneurs have relocated their production out of the economy in order to reduce the demand for the territory's relatively scarce resources (Tan, 1992).

Kirzner (1973) contended that a unique feature of entrepreneurship lies in its alertness and opportunity exploitation. In the market process, the opportunity that human agents are alert to is monetary profit. The role of the entrepreneurs, as Kirzner argues, arises out of their "alertness to hitherto unnoticed opportunities". They proceed through their alertness to discover and exploit situations in which they are able to sell for high prices that which they can buy for low prices. Alertness implies that the actor possesses a superior perception of economic opportunity. In this sense, Kirzner's mode of entrepreneurship broadly encompasses the functions of a gap filler or routine entrepreneurship (Leibenstein, 1968).

Extending Kirzner's insights to the catching-up process, Cheah (1992) has contended that entrepreneurs in latecomer economies "increase knowledge about the situation, reduce the

general level of uncertainty over time and promote market processes which help to reduce or to eliminate the gap between leaders and followers". For Cheah, these entrepreneurial activities include "arbitrage, speculation, risk taking, adaptive innovation, imitation as well as planning and management efforts in response to market signals".

In his analysis Porter (1990) states that four interrelated sets of factors or conditions determine the competitive strength of nations and thereby the possibilities for sustained productivity growth. These four sets of factors make up the so-called national “diamond”. The four determinants are:

• Factor conditions. Porter distinguishes basic factors (e.g. natural resources and cheap, unskilled labor) from advanced factors (highly skilled personnel, modern networks infrastructure);

•Demand conditions. These have three main elements: the nature of buyer needs (e.g. sophisticated instead of basic), the size and the pattern of growth and the existence of mechanisms by which a nation’s domestic preferences are transmitted to foreign markets; • Related and supporting industries. The presence of internationally competitive supplier and related industries stimulates rivalry and partial cooperation;

• The structure and culture of domestic rivalry. This encompasses a wide scope such as opportunities provided to possible new entrants, the nature of competition between incumbent firms, dominant business strategies and management practices.

The relevance of Porter’s diamond can be summed up in one sentence: “Invention and entrepreneurship are at the heart of national advantage” (Porter, 1990). More specifically, Porter’s “diamond” can help investigating the interface between entrepreneurship and

National factor creation mechanisms affect the pool of knowledge and talent. Supplier industries provide crucial help or are the source of new entrants. Domestic rivalry creates a good “incubation environment” for entrepreneurs, but it can also be a mechanism by which entrepreneurship contributes to growth. Finally, feedback mechanisms are relevant because entrepreneurship can enhance the quality of the factor conditions through the learning process which starting a business provides (Wennekers, Thurik, 1999).

2.2 Venture Capital as a facilitator

Leff (1979) claims that entrepreneurship was clearly essential if the investment, innovation, and structural changes required for economic development were to be achieved. But both on the supply and on the demand sides, entrepreneurship seemed to constitute a serious problem for the underdeveloped countries. According to Leibenstein (1968) this is because of the deficiencies of organized factor and product markets in "obstructed, incomplete and `relatively dark' economic systems, thus the entrepreneurship requirements per unit of incremental output would appear to be higher in underdeveloped than in more-developed economies.

Here comes the importance and the main advantage of Venture Capital. Venture Capital facilitates the economical contribution of entrepreneurs who has difficulty to finance their ideas and VC give them the chance to realize their goals. The following example is an example how Capital Venture makes difference.

“A software engineer at the government contractor EG&G, Don Brooks had been working on computer systems for the Idaho National Engineering and Environment Laboratory, a Department of Energy facility, when he suddenly had a brainstorm that he knew would help

him as well as others solve an all-too-common problem. Using the "gopher" technology that had long made the exchange of files and programs across mainframe devices possible, in 1991 Brooks developed a way for one computer to access data stored on another and to interact with that information. As he publicized his innovation among his fellow employees and across the computing community, people admired the quality of his work. In fact, in head-to-head comparisons, his software program garnered ratings far superior to those of Mosaic, a similar tool then under development at the University of Illinois. Reviewers of Brooks's prototype raved about its ease of use and reliability. The engineer felt certain that, with EG&G's backing, his idea would soon be a major success in the marketplace.

But his hopes were not realized. Four years later, another company working on the same technology went public to great acclaim and fanfare. The firm? Netscape Communications, under the leadership of Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark. Because its new product was based on the Mosaic technology developed at the University of Illinois, Netscape became embroiled in a messy intellectual-property dispute. Despite these challenges, on its first day of trading, Netscape soared to a market capitalization of $2.1 billion.

Why did Andreessen and Clark succeed where Brooks failed? Part of the answer lies in the role of Netscape's initial financiers, the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. While Brooks struggled to interest EG&G in backing his concept (EG&G considered Brooks's idea outside its core business), Kleiner Perkins moved decisively to fund the fledging Netscape, realizing that market timing was critical to the success of the new venture. In addition to providing financing and advice on product development, marketing, and finance, Kleiner introduced Netscape to key Silicon Valley players, as well as the investment banking teams at Morgan Stanley and Hambrecht & Quist. Even more telling is that Jim

and could have easily financed the firm himself. Instead, he understood the value that Kleiner Perkins could bring to Netscape. Lacking such assistance, Brooks soon fell far behind his rivals.

Like Brooks, most high-technology entrepreneurs are convinced that their ideas hold immense promise. Often, their excitement is well founded. An innovative product or new service concept may have enormous market potential and may far outperform competitors' alternatives. Moreover, the intellectual talents of the founding team may be stellar.” (Gompers and Lerner, 2001)

However, many of these entrepreneurs discover they need to attract money to fully commercialize their concepts. Thus they must find investors -- such as their own employer (if the idea was created while on staff), a bank, an "angel" financier, a public stock offering, or some other source. But potential investors often greet entrepreneurs' business plans with skepticism, or worse, turn them down entirely. Alternatively, some investors demand a large equity stake in the project and tight control rights in exchange for a modest sum of money. Before the emergence of the venture capital market, the vast majority of entrepreneurs seeking financing from traditional sources failed to realize value from their ideas. Indeed, many product or service innovators privately (and sometimes publicly) referred to investment professionals as "vulture capitalists." These entrepreneurs' frustrations are understand-able: Most financiers do not understand the fragile growth process that start-ups experience.

But entrepreneurs themselves have also contributed to their own financing problems. Many of them simply don't have a clear picture of the risks inherent in their business models -- risks that pose some serious concerns for potential investors -- or they lack a thorough understanding of the four basic problems that can limit financiers' willingness to invest

capital: Uncertainty about the future, information gaps, "Soft" assets, volatility of current market conditions.

All companies must grapple with these difficulties, but young, emerging enterprises are particularly vulnerable to them, as these problems limit their ability to receive value from their ideas and innovations. (Gompers and Lerner, 2001)

First of all, there is a broad literature which derives a comparative advantage of venture capital-backed companies with respect to their growth rates. A possible reason for this advantage could be the fact that venture-backed companies are more innovative than non-venture backed companies (Kortum and Lerner, 1998). Although Engel and Keilbach (2002) deny this for Germany, Engel (2001) derives a higher growth rate of venture capital backed companies in Germany that could be attributed to the superior managerial advice of VC companies (Keuschnigg and Nielsen, 2000). Another positive aspect of the managerial advice of VC companies is the higher survival rate of venture-capital-backed start-ups. The advice of VC companies should help start-ups avoid making managerial mistakes that could threaten their existence. (Fehn and Fuchs, 2003)

Lerner (1995) claims that venture capital organizations are increasingly understood to play a role distinct from that of other capital providers. Because they gain a detailed knowledge of the firms that they finance, these inside investors can provide financing to young businesses that otherwise would not receive external funds. The contribution of entrepreneurs to the economy is facilitated by venture capital organization.

2.3 Venture Capital Contribution to USA Economy

American economy. The dollars and cents contribution of the venture capital industry goes well beyond the objective economic contribution. It continually reinforces America’s entrepreneurial spirit. And in so doing, the venture capital industry becomes a catalyst for change. Venture capitalists, many of whom are successful former entrepreneurs themselves, shepherd new business men and women to reach their full potential.

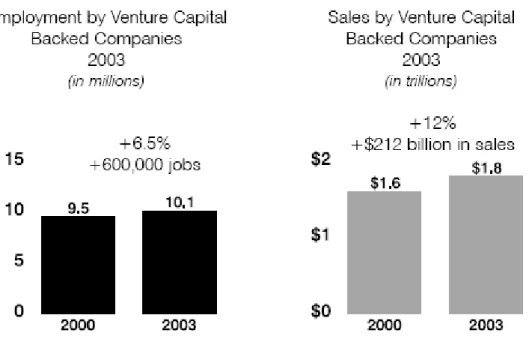

In the report the statements were shown statistically. According to the NVCA report venture capital funded companies were directly responsible for more than 10 million jobs and $1.8 trillion in sales in 2003. This corresponds to 9.4 percent of total U.S. private sector employment and 9.6 percent of company sales.

Table 1: Economic Benefits of VC Backed Companies USA

Source: NVCA (2004)

This is impressive given that venture investment was less than two percent of total equity investment for most of the past 34 years.

Venture capital backed firms create jobs at a significantly faster rate than their nonventured counterparts. Venture backed firms increased their employment base by 6.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, while overall total private sector employment dropped by 2.3 percent during the same time period. The Global Insight analysis shows that ventured firms were only mildly impacted by the recession. The venture capital job creating engine is not limited to one segment of the economy. It permeates the entire American economy. NVCA (2004) examined

venture capital backed companies. Ventured companies in biotechnology posted an employment gain of 23 percent and healthcare products grew by 16 percent between 2000 and 2003. Only two industry sectors: computer hardware and services and semiconductors, experienced net job losses for venture backed firms between 2000 and 2003.

Figure 3: VC Backed Companies Crate Job and Wealth

Source: NVCA (2004)

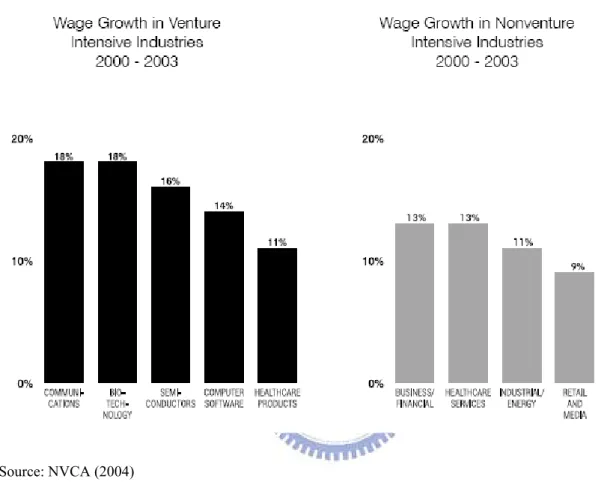

The TVCA (2004) study shows that venture capital firms tend to cluster in fast growing and higher paying industries. The graphs below show the wage growth for those industries that have a high intensity of venture capital investment and those industries with a low intensity of venture capital investment. Those firms with a higher intensity of venture capital tend to be firms that also have a higher wage growth. The data show that wages paid by venture capital backed firms grew by 12 percent between 2000 and 2003, compared to a national wage growth rate of 11 percent. As the graph below illustrates, the 5 venture-intensive industries

with the most rapid wage gains are communications, biotechnology, semiconductors, computer software, and healthcare products.

Figure 4: Wage Growth in Venture Intensive Industries Vs. Nonventure Intensive Industries USA

Source: NVCA (2004)

Several venture capital intensive industries posted substantial wage increases in the last three years. Wages in biotechnology and communications each jumped by 18 percent between 2000 and 2003. Other fast growing industries measured by 2000 to 2003 wage growth rates were semiconductors, computer software, and healthcare. (NVCA, 2004)

2.4 Venture Capital Contributions to Taiwan’s GDP and

Employment Market

According to TVCA (2006), Taiwan’s venture funds have made accumulated investments in excess of NT$ 188 billion in emerging technology companies. With the guidance and financial assistance of their venture investors, a large percentage of the companies eventually transformed into the investment targets of institutional investors. Therefore, venture funds play a crucial role in directing the flow of private equity into the domestic technology industry. Looking solely at venture-backed listed companies, venture funds have helped create capital formation of NT$ 2.07 trillion, which was 18.6% of Taiwan’s GDP in 2005. According to the same report, if the thousands of pre-IPO companies that venture funds have invested in over the years were added into the calculation, the resulting total would far surpass these figures.

Table 2: Capital Size of Venture‐Backed Listed Companies in Taiwan, 2005

Source: TVCA, 2006

Through analyzing data on venture-backed IPOs, we can achieve a deeper understanding of the contributions venture funds have made to Taiwan’s GDP and employment market.

1. Contributions to Taiwan’s GDP

According to TVCA (2005) survey results, Taiwan’s venture funds have made accumulated investments in 408 TSEC and OTC-listed companies. Subtracting the 40 companies that

delisted or merged with another companies after going public, Taiwan’s venture funds have helped 368 companies go public on the TSEC and OTC over the past two decades.

In the past twenty years, Taiwan’s venture funds have made over 10,000 investments in several thousand companies. Of these, only a small percentage eventually went public. Employing cost-benefit considerations, TVCA (206) used the turnover volume of venture-backed listed companies’ shares to represent the industry’s contribution to Taiwan’s GDP.* According to the statistics published by Securities and Futures Bureau, the total turnover volume of venture-backed companies listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation (TSEC) and Over-the-Counter Market (OTC) in 2005 was NT$ 5.34 trillion, or roughly 48% of Taiwan’s GDP in 2005. In other words, venture funds’ accumulated NT$ 139 billion investments in domestic enterprises has transformed into a market scale of NT$ 5.34 trillion, or nearly half of Taiwan’s GDP. From these figures, the effectiveness of investments made by Taiwan’s venture funds can clearly be seen.

2. Contributions to Taiwan’s Employment Market

According to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting, and Statistics (DGBAS) under the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s labor force totaled 10.04 million in 2005. Venture-backed listed companies employed 321,469 persons in 2005, or 3.2% of the labor force. Given that the majority of accumulated venture capital investments flowed into the manufacturing industry, a more accurate picture can be painted with a closer look at the industrial sector’s labor force. According to DGBAS statistics, the industrial sector employed 2,429,902 persons in 2005. Therefore, venture-backed listed companies employed 13.23% of the industrial labor force. In other words, one out of every 7.5 people employed in the industrial sector directly or indirectly owes their job to the venture capital industry.

Table 3: Taiwan Venture Capital Industry’s Contribution to Local Job Market, 2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

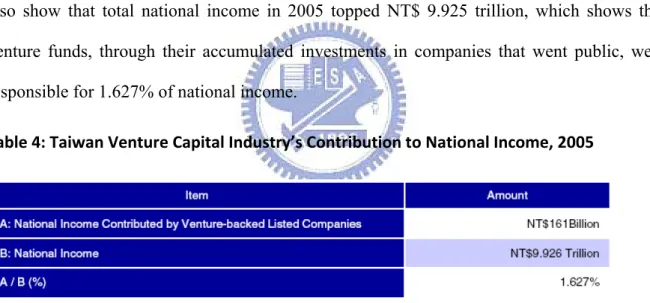

DGBAS statistics show that industrial sector employees earned an average monthly wage of NT$ 41,872 in 2005. Venture funds have therefore generated NT$ 161.5 billion in income for the employees of venture-backed listed companies in the industrial sector. DGBAS statistics also show that total national income in 2005 topped NT$ 9.925 trillion, which shows that venture funds, through their accumulated investments in companies that went public, were responsible for 1.627% of national income.

Table 4: Taiwan Venture Capital Industry’s Contribution to National Income, 2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

The above analysis makes it clear that domestic venture funds have made invaluable contributions to GDP, employment, and national income in Taiwan. Taiwan’s venture funds have played a crucial and active role in developing the economy over the past two decades. (TVCA, 2006)

CHAPTER 3. VC INDUSTRY IN TAIWAN

3.1. History of Taiwan VC industry

In order to spur growth in domestic industries, the Government of Republic of China (ROC) imported the American venture capital model into Taiwan in 1980. The ROC government hoped to use the successful American venture capital experience as a blueprint to develop Taiwan’s technology industry. Taiwan’s first venture fund was established in 1984. How Taiwan’s first venture fund performed is unclear; it took a decade for results to begin showing and to reach the expansion stage. Taiwan’s technology industry took off in 1990 and began playing an increasingly key role in the global technology market. In particular, the domestic information, electronics, semiconductor, telecommunications, and opto-electronics industries flourished. The sustained development and stabilization of Taiwan’s capital market further propelled the domestic venture capital industry into an era of rapid growth. The period between 1995 and 2000 proved to be a golden era for the domestic venture capital industry. In 1996, four venture funds made it into the “Top 20 Returns on Investment” and “Top 10 Most Profitable” lists in Business Weekly’s poll of Taiwan’s top 500 service companies. Between 1995 and 2000, the number of venture funds increased from 34 to 170 while capital under management rose from NT$ 18.7 billion to NT$ 151.2 billion. During these five years, venture funds achieved average Earnings Per Share (EPS) of NT$ 1.7, a remarkable achievement in such a short period of time. Aided by the rapid development of the technology industry, Taiwan’s venture capital industry blossomed. However, the industry has yet to recover from the recession that crippled the global economy in 2000. Since then, both capital raised and the number of new funds established each year have fallen; performance has also suffered. In the past five years, Taiwan’s venture capital industry has faced many

unprecedented challenges. Following is a breakdown of the current state of the industry and recommendations. (TVCA, 2006)

3.2. Current trends and situation of VC

Fundraising

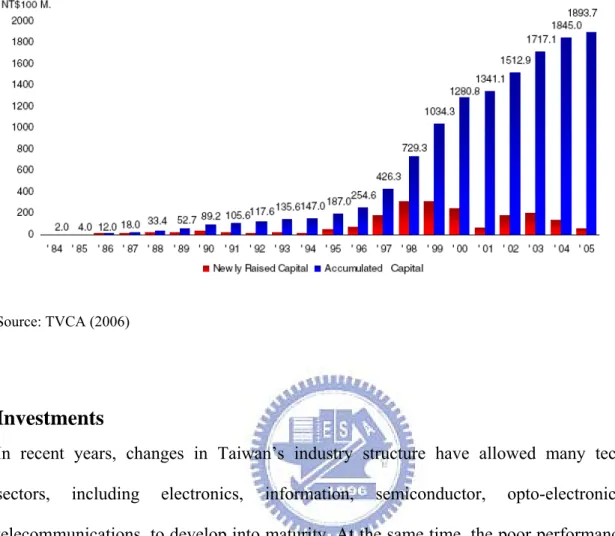

Since 2000, the global economy has been going to a recession and domestic investor confidence has plummeted. The elimination of a 20% tax credit for shareholders of venture funds that had been in place since 1983 further exacerbated fundraising difficulties. Just seven funds were established in 2001, a 78% decline from the previous year. Between 2000 and 2004, the majority of new funds were established by financial holding companies and corporations. During this period, 60 funds with total capital under management of NT$ 16.7 billion were formed. However, the overall domestic operational environment remained poor, and only nine funds were set up in 2005, the lowest number in a decade (excluding 2001). In 2005, a number of funds discontinued operations. Total capital under management decreased by NT$ 7.193 billion (due to either funds being discontinued or decapitalized, a 185% increase over the NT$ 3.879 billion that was decapitalized between 1984 and 2004. Therefore, newly-raised capital fell from NT$ 12.79 billion in 2004 to NT$ 4.87 billion in 2005(1). The NT$ 4.87 billion was a ten-year low, and just 16% of 1999 levels. Clearly, the domestic venture capital industry is stagnating. If improvements don’t transpire soon, the industry might begin shrinking.

Figure 5: Newly Raised Capital and Accumulated Total Capital, 1984‐2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

Investments

In recent years, changes in Taiwan’s industry structure have allowed many technology sectors, including electronics, information, semiconductor, opto-electronics, and telecommunications, to develop into maturity. At the same time, the poor performance of the capital market compounded by plummeting EPS in the stock market means that it is difficult for investment prices to satisfy the expectations of both buyers and sellers. These factors combined have created a shortage of suitable investment targets. Below, the overall investment environment, investments by industry, investments by region, and investments by stage in 2005 are summed up.

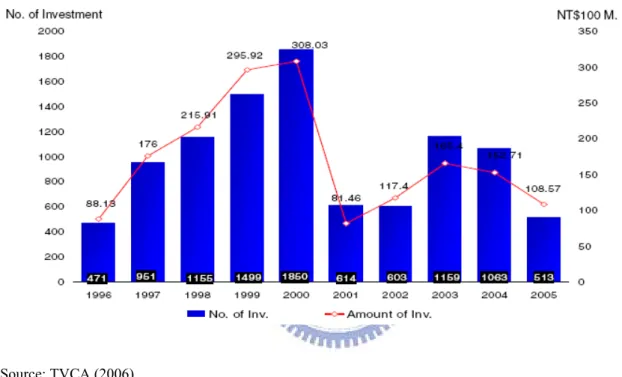

1. Overall Investments

Venture funds invested a total of NT$ 10.86 billion in 513 portfolio companies in 2005. Both numbers were down from 2004, during which NT$ 15.27 billion was invested in 1,063 companies. The number of investments in 2005 was a ten-year low, while the amount of

investment was the lowest since 1997 (excluding 2001). Investment activities in Taiwan decreased during 2005 due to a number of factors, such as lack of suitable investment targets, exit obstacles, and the discontinuation of funds, etc.

Figure 6: Number and Amount of Investment, 1996‐2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

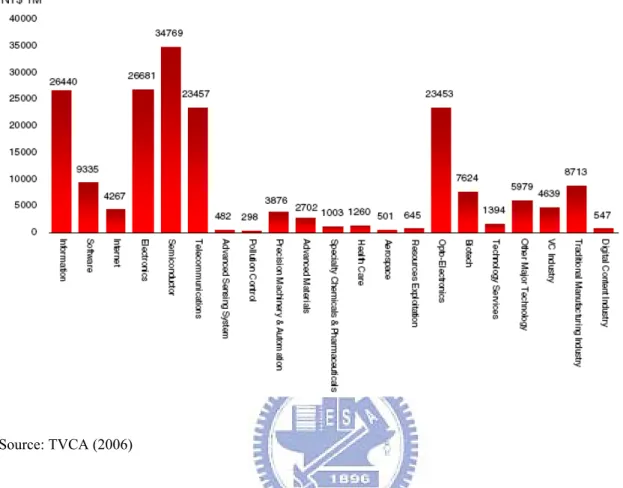

2. Investments by Industry

In 2005, the opto-electronics (17.52% of total investments amount), traditional manufacturing (17.36%), electronics (11.89%), semiconductor (11.18%), biotechnology (7.93%), telecommunications (6.72%), and information (5.52%) industries accounted for 78% of all investments. Compared with 2004 levels, investments in the opto-electronics, electronics, semiconductor, telecommunications, and digital content industries plummeted by,

Figure 7: Accumulated Venture Capital Investments by Industry & Amount of Investment, 1984‐2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

However, investment in the traditional manufacturing, biotechnology, software, and Internet sectors were up by, respectively, 94%, 30.5%, 143.7%, and 337.3%. Sectors that venture funds have traditionally focused on in the past, such as opto-electronics, semiconductor, and electronics, have more or less reached maturity. Although these sectors continue to receive the bulk of venture fund investments, there is not much growth projected in these sectors. The domestic digital content industry, on the other hand, is still immature, small in size, and fiercely competitive. Venture funds therefore view this industry conservatively, which is reflected in the amount of investment that flows into this sector. The biotechnology, software, and Internet industries have performed poorly in the past few years. Nevertheless, despite the overall investment amount plummeting, investments in these particular industries went up in 2005, perhaps indicating that the tide is turning for these industries. Of particular note,

2005, the sector received the second highest amount of investments among all sectors, with only the opto-electronics industry receiving more. It is clear that the advantages of and opportunities available in the traditional manufacturing industry have succeeded in capturing the attention of venture investors.

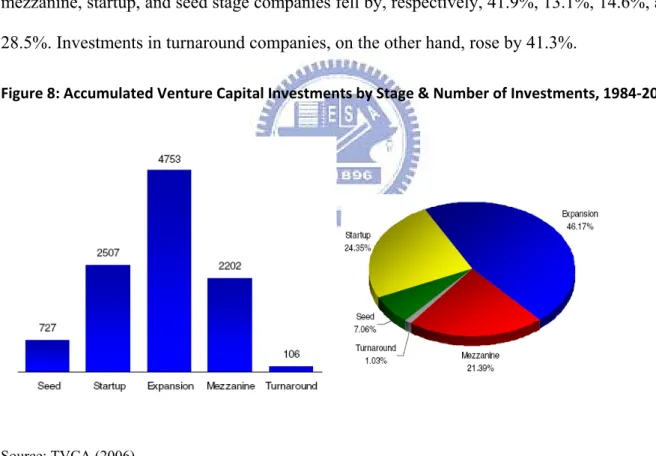

3. Investments by Stage

In 2005, expansion stage companies received 42.29% total investment amount, followed by mezzanine companies (26.95%), startup companies (20.69%), seed companies (8.06%), and turnaround companies (2.02%). Compared with 2004 levels, investment amount in expansion, mezzanine, startup, and seed stage companies fell by, respectively, 41.9%, 13.1%, 14.6%, and 28.5%. Investments in turnaround companies, on the other hand, rose by 41.3%.

Figure 8: Accumulated Venture Capital Investments by Stage & Number of Investments, 1984‐2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

In 2004 and 2005, expansion stage companies received, respectively, 51.7% and 42.29% of total investment amount. In 2004, mezzanine, startup, and turnaround stage companies received, respectively, 22.1%, 17.2%, and 1% of all investments. In 2005, investment amount

20.69%, and 2.02%. Meanwhile, investments in seed stage companies remained constant at around 8%. Venture funds continue to focus the majority of their investments in expansion stage companies. Spurred by signs that the domestic stock market is rebounding, the rates of return of mezzanine stage companies have begun climbing. Therefore, venture funds have started to increase their investments in mezzanine stage companies while at the same time considering investments in turnaround stage companies and mergers and acquisitions. In the future, the domestic venture capital industry will likely develop in the direction of the private equity sector. (TVCA, 2006)

Exits

According to Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation (TSEC) and Over-The-Counter Market (OTC) statistics, a total of 70 companies went public in 2005, with 13 listed on TSEC and 57 on OTC. Compared with 126 IPOs in 2004, the number of IPOs in 2005 fell to 70 by 44.4%. It was the fewest in years, and also marked the biggest year-to-year decline. Thus, venture funds’ performance and exits from investments were adversely affected. The decline can be attributed to several factors. First, in 2005, a great number of Taiwan owned enterprises chose to list on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Second, the Taiwan’s stock market didn’t present bullish during the year. Third, companies delayed their IPO plans due to new underwriting regulations.

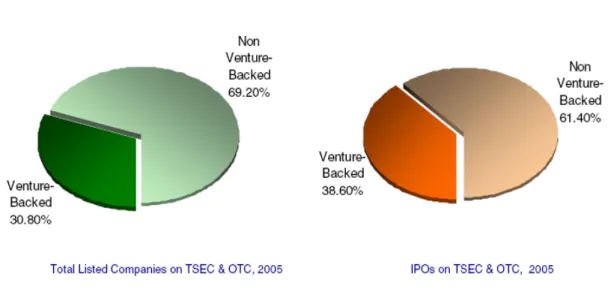

Figure 9: Taiwan’s IPO Market & Exits, 2005

Source: TVCA (2006)

In 2005, venture-backed IPOs accounted for 53.8% of all TSEC IPOs, 35.1% of all OTC IPOs, and 38.6% of all domestic IPOs. A total of 54 technology companies went public on the with 9 listed on TSE and 45 on OTC in 2005. Of the 9 TSEC IPOs, 6, or 66.7%, were venture-backed; of the 45 OTC IPOs, 17, or 37.8%, were venture-backed. From these statistics, it is clear that technology companies remain the focus of venture capitalists. However, compared with previous years, the proportion of VCs’ investments in technology companies has fallen, while that in the traditional manufacturing and service sectors has risen. Overall, IPO performance in 2005 was negatively affected by a spate of factors, including cross-strait instability, soaring prices of natural resources, the trend of Taiwan-based enterprises listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and new regulations related to stock underwritings. Plans for IPOs were altered and delayed time and time again as companies waited for cross-strait relations to stabilize before going public. Therefore, in the next one to two years, the number of IPOs will likely increase, which is a good news for domestic venture capital industry. (TVCA, 2006)

3.3. VC regulations in Taiwan

As a direct result of this change, the "Regulations Governing Venture Capital Investment Enterprises" was also eliminated and replaced on May 23, 2001 with the Regulations "Scope and Guidelines for Venture Capital Investment Enterprises" which governs the formation and operation of venture funds. Under the new regulations, applications for the establishment of new venture funds became the jurisdiction of Department of Commerce under the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA). A prospective venture fund with business scope described in Article 3 of the new regulations with capital commitments from banks, insurance companies, securities firms, financial holding companies, or pension funds needs to take the additional step of applying for a recommendation from the Industrial Development Bureau (IDB) under MOEA. Said banks, insurance companies, and securities firms can only invest in the venture fund if the recommendation is granted by the government. Venture funds that wish to apply to the NT$ 100 billion venture capital fund investment project of the Development Fund under Executive Yuan for capitals need to submit an application to the Trust Department of the International Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and wait for the approval of the Investment Review Committee of the Development Fund. Applicants approved by the Committee can then officially set up a venture fund and commence investment activities in accordance with the Development Fund’s guidelines and regulations. The investment scope set by the Development Fund, which previously limited investee funds to investing in the manufacturing industry, has now been relaxed to include the service industry.

Since 2005, responsibility for overseeing and governing the venture capital industry officially shifted from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) to MOEA. The government hopes that this move will breathe new life into the industry. On March 31, 2006, MOEA completed a draft amendment of “Scope and Guidelines for Venture Capital Investment Enterprises” to relax

restrictions on venture capital fund sources, allowable investment targets, and usage of idle capital. The Council for Economic Planning and Development (CEPD) is also assessing the feasibility of venture capital funds incorporating in the form of limited partnerships. The resulting draft bill will be evaluated by the Executive Yuan, and if passed, will greatly benefit domestic venture funds during the fundraising process, and bring domestic venture fund regulations into line with those of other nations with developed venture capital industries. Government policies and the industrial environment are the main factors that affect the development of the domestic venture capital industry in Taiwan. Current laws and regulations affecting the industry are summed up below:

The Revised “Scope and Guidelines for Venture Capital Investment Enterprises” has Allowed Venture Funds to Develop in Multiple Directions

In 2005, jurisdiction over venture capital investment enterprises (funds) shifted from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) to the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA). Following a number of negotiation sessions between Taiwan Venture Capital Association (tvca) and the MOEA, the Executive Yuan formally announced a draft revision to the “Scope and Guidelines for Venture Capital Investment Enterprises” (Scope) on March 31, 2006. The main revised points are as follows:

1. Jurisdiction over venture capital investment enterprises (funds) shifts from MOF to MOEA, while the appointed office overseeing venture capital-related matters shifts from the Development Fund under Executive Yuan to the Industrial Development Bureau (IDB) under MOEA.

2. Prospective venture funds with capital commitments from banks, insurance companies, securities firms, financial holding companies, or pension funds now need to apply for a recommendation from IDB (previously from TVCA).

3. Restrictions governing the scope of venture capital investments are eliminated. In the future, venture funds won’t face restrictions on industries of investment targets.

4. Restrictions on the usage of idle capital are eliminated, while regulations governing venture funds’ investments in public companies are relaxed.

While prospective venture funds with capital commitments from financial institutions or pension funds now need to apply for a recommendation from IDB, it remains unclear which office is responsible for various other aspects of fund formation until IDB makes final decisions about the guiding process and enforcement rules. Before that the prospective venture funds can seek assistance from either IDB or tvca. In addition, the elimination of investment restrictions on venture funds and the relaxation of venture funds’ idle capital usage as set forth in the revised “Scope and Guidelines for Venture Capital Investment Enterprises” allows and encourages domestic venture funds to develop in the direction of private equity placement.

B. Draft Amendments to the “Financial Holding Company Act” will Impact Venture Funds’ Fundraising Activities

The promulgation of the Financial Holding Company Law in 2001 allowed financial holding companies to invest in venture funds. Over the past five years, domestic financial holding companies have invested over NT$11 billion in venture funds. Over the past three years, financial holding companies have become the main source of capital for venture funds. However, in 2005, the Financial Supervisory Commission pushed forth draft amendments to

the “Financial Holding Company Act.” A number of scholars and analysts feel that “venture capital” has no relation to the finance industry, and therefore “venture capital investment enterprises” should be listed in Article 37 of the Act under industries that financial holding companies cannot invest in, rather than in Article 36 under industries financial holding companies can invest in. If this amendment is passed, securities firms held by financial holding companies will begin to decrease their investments in venture funds, which would deal a heavy blow to the venture capital industry since it is already facing a capital shortage. The venture capital industry hopes to stage negotiation sessions with the government, and amend laws in ways that would benefit, rather than harm, the future of the industry.

C. Revisions to Regulations Governing Directors’ and Supervisors’ Deposited Shares will Aid Venture Funds in Exiting Their Investments

As an investment specialist, a venture fund assume a seat on its portfolio company’s Board of Directors or as the company’s supervisor in order to provide the company with management and operation guidance until it is ready to go public. The role it plays is different from that of general company management. After the portfolio company goes public, venture funds can exit their investment by selling their shares in the company when the timing is right. With the proceeds from the sale, the fund can then invest in another early-stage company. According to the securities depository regulations, once a venture fund attains a seat on its investee company’s Board of Directors, a certain percentage of its shares in the company becomes non-transferable for a period of four years, while a smaller percentage of the shares may never be transferred or sold. These shares are deposited with the Taiwan Depository and Clearing Corporation (TDCC, formerly the Taiwan Securities Central Depository Company), where they will remain for the restricted period. In general, venture funds have a fixed life of around seven years. In many cases, at the time when the funds are closed, it is unable to regain

custody of the deposited shares from TDCC. In other words, the current legal structure is an exit obstacle for venture funds.

The Taiwan Venture Capital Association (tvca) has on multiple occasions related these difficulties to the government, and its efforts were rewarded on May 3, 2006 when “Directions Relating to Article 3, Paragraph 1, Subparagraph 4 of the GreTai Securities Market Criteria Governing Review of Securities Traded on Over-the-Counter Markets” was amended. The major revisions to the regulation are as follows:

1. Before the regulation was amended, the directors and supervisors and major shareholders of a company could begin to reclaim 20% of their deposited shares two years after the company becomes listed on Over-The-Counter Securities Market (OTC), and 20% more in each successive six-month period. Under the amended regulation, the directors and supervisors and major shareholders of a company can reclaim all of their deposited shares after the company has been listed on the OTC Market for two years as long as the company does not violate any of its listing terms and maintains a pre-tax profit margin of 3%.

2. Because the objectives of legal-setting 1) the minimum percentage of shares that directors and supervisors of a company must hold and 2) the mandatory depositing of shares differ, and also because these two regulations have different target groups and of calculation bases, the revision eliminated the minimum percentage of shares that directors and supervisors must hold.

3. Although restrictions governing deposited shares after a company lists on the OTC market have been relaxed, the regulations governing deposited shares prior to listing on the OTC Market have become more stringent. According to the revised regulation, any shares that are additionally issued to directors, supervisors, and main shareholders for any reason, including

Corporation (TDCC) for the period starting on the day that the application for listing is first filed and ending on the day that the company officially lists on the OTC market. The shares cannot be pledged or transferred during this period.

In summary, revisions to the regulations governing the deposited shares of companies’ directors and supervisors will benefit those companies’ management with outstanding performance and fulfillment of loyal duties. The length of time that shares owned by directors and supervisors of companies must remain in deposit has been halved from four years to two. The minimum percentage of shares that directors and shareholders must hold has also been eliminated. In other words, venture funds will face an easier time divesting of their long-term securities assets, which is extremely helpful when a fund closes. Generally speaking, the revised regulations will be very beneficial for venture funds in exiting investments and overall performance. (TVCA, 2006)

CHAPTER 4. VENTURE CAPITAL IN TURKEY

4.1 History of VC in Turkey

Regulation concerning venture capital is first set in 1993, however due to the reason that will be mentioned later there was no VC Company found until 1996, when Vakıf VC was established with an available fund of 500 billion TL (6 million US dollars). This money was provided by the government-owned Vakıf Bank. It has been the recipient of more than 500 project applications since its launch in 1996 and has made investments in three of these. All three of the firms that Vakıf VC invested in were small startup firms that are technology-based. Two of these portfolio firms were located in a technopark within a university, while the other one operated out of a free trade zone. İş VC was established towards the end of 2000, but has not made any investments for a period of time. This lack of movement can in part be put down to the volatility of the Turkish economy caused by the recession which began in February 2001, and the devaluation of the currency by 100% in one year. This recession and devaluation had cooled a lot of the interest that was beginning to build in the VC. Many of the large family owned conglomerates were beginning to show interest in establishing VC firms prior to the recession, but then bankers and investors were super cautious and as such the VC would not have to be impatient for that time.

After the markets in Turkey recovered and the trust to Turkish economy increased, Is VC start to invest on start up and mezzanine companies, and became the largest VC Company with 150 million USD capitals raised.

In 2004, another actor entered to Turkish VC market, which is formed by The Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchange of Turkey and government-owned Halk Bank. The

4.2 Current status of VC industry

The present state of affairs does not present a very pretty picture; however, the dimensions of the VC are as follows:

Currently there are only 3 registered VC firms in Turkey (founded in 1996, 2001, 2004) | Total capital raised by these three VC funds is US$131m (186.6mTL)

| The number of companies invested by these three VC funds is 10.

| 2 IT, 2 software, 1 internet, 1 chemical, 1 machinery, 1 car rental, 1 retail, 1 trade show organizer.

| Total investment is US$64m (91.1mTL)

Actors in the Turkish Venture Capital Market

Business Angels: There is no accurate data available showing the extent to which business

angels’ invests in innovation companies in Turkey. It is however common knowledge that wealthy business people do invest in other companies at the behest of the entrepreneurs. The entrepreneur informally approaches the business person and if the business person recognizes that there is potential profit in the venture then they may choose to invest.

VC firms: At the present time there are only there officially registered VC firms in Turkey.

These are Vakıf and İş VC partnerships and KOBI VC established by Vakıf Bank, İş Bank, and Halk Bank, respectively.

Corporate VC: Corporate VC is a relatively new phenomenon for Turkey. Of the companies

that carry out VC activities, few, if any has an actual VC department. The VC investments that take place are done in an ad hoc manner on a very informal level. As a result of this it is

impossible to know how many firms are conducting VC operations and also the funds available. (Cetindamar, 2003)

4.3 Regulations concerning VC

The regulations concerning Venture Capital in Turkey are first introduced in 1993 on the Communiqué of Capital Markets Board of Turkey (CMB). According to the regulation the venture capital was divided in to three parts; venture capital investment funds, venture capital investment cooperation and venture capital management companies. The right to decide and audit their operations was given to Capital Markets Board of Turkey. However, at the time the regulation set the minimum initial capital to 9 million USD, and registered capital limit to 27 million USD, according to the currency rate of the time. The amounts set by the communiqué were considered to be so high and didn’t attract any investors at that time (Tuncel, 1995). In 1998 the starting capital is changed to 2 million USD and investment field were deregulated. However, there was a condition that the venture capital companies should offer at least 49% of its shares to the public. (The first year 10% of the shares, until the end of the third year 30%, and after five years 49%). This regulation was found impractical by many investors. Investors considered that it is difficult to take a newly found venture capital company to IPO, after its first year of establishment.

In 2004, another change made to facilitate the venture capital conditions in Turkey. The new regulation allowed the pension funds to invest on venture capital companies under some circumstances. According to the new communiqué the requirements for foundation was set as following;

According to the regulations venture capital investment trusts are a form of collective investment institutions, directing issued capital toward venture capital investments which are

defined as long-term fund transfers, through investing in capital market instruments issued in primary markets by the entrepreneur companies already established or to be established, with the aim of obtaining capital or interest gains.

As in investment trusts, There is no restriction on the founders accept for certifying that they have not been subjected to any legal prosecution due to bankruptcy or another disgraceful offence. Legal persons as well as real persons can be founders of a VC.

Some of the portfolio restrictions for VCs are about;

· Investing in the companies in which major shareholders or directors of the VC has a share of at least 10%.

· Investing in securities of non-entrepreneur companies in the second market. · Investing in other VC.

As in the case of investment trusts, investors buy shares of a VC in the stock exchange. In return they are paid dividends at the end of the years. They may also sell their shares in the exchange and receive capital gains anytime they want.

After being approved by the CMB the article of incorporation of the VC is announced in the Turkish Commercial Registry Journal. As well as that; they have to prepare prospectus in the case of issuance and public offering of the shares. Besides, important developments about the VCs and their monthly portfolio tables including their assets and net asset value per share are announced to the investors in the bulletin of the stock exchange. Finally their annual and semiannual financial statements have to be audited by a certified external auditor.

The disclosure liabilities, portfolio restrictions and the listing requirement for the VCs ensure the protection of the investors. VCs are exempt from the Corporation Tax in Turkey. (CMB, 2007)

CHAPTER 5. LITERATURE REVIEW OF FACTORS

THAT AFFECT VC

5.1 VC driving forces

Despite this wide recognition of venture funds as key players underlying a country’s entrepreneurial performances, there are huge differences across industrialized countries in the relative amounts invested in VC. VC intensity is relatively high in the USA and Canada for instance, whereas it is very low in Japan. The diversity of national financial systems is undoubtedly one important factor underlying these international differences. Black and Gilson (1998) find a linkage between countries’ financial system and VC market. Active stock market is more appropriate to strong venture capital market than bank market because of the potential for VC exit through an IPO. An active VC market requires a liquid stock market. Other factors also play an important role, as shown by Gompers and Lerner (1998), Jeng and Wells (2000) and Sherlter (2003). With a panel dataset of 21 countries Jeng and Wells show that labor market rigidities, the level of Initial Public Offerings (IPO), government programs for entrepreneurship, and bankruptcy procedures explain a significant share of cross country variations in VC intensity.

According to Black and Gilson (1998), active stock market is important for strong venture capital market because of the potential for VC exit through an Initial Public Offering. IPO is considered as being a very important determinant of VC. It is the strongest driver of VC according to Jeng and Wells (2000) because it reflects the potential return to VC funds. Gompers and Lerner (1998) take it as a proxy for fund performance but cannot find any significant effect in their multivariate regressions. It seems that the IPO variable is strongly

Product (GDP), which is also a proxy for exit opportunities. GDP and Market Capitalization Growth (MCG) are part of the impact of IPOs and therefore turn out to be not significant for Jeng and Wells (2000). However the reverse is true for Gompers and Lerner who find a positive and significant impact of Equity Market Return and GDP on VC but no impact of IPO. Higher GDP growth implies higher attractive opportunities for entrepreneurs, which lead to a higher need for venture funds. Schertler (2003) uses either the capitalization of stock markets or the number of firms listed as measure of the liquidity of stock markets. He finds that liquidity of stock market has a significant positive impact on VC investments at early stages. However, as Jeng and Wells (2000), he finds that the growth rate of the stock market capitalization does not have significant impact on VC investments at early stages.

For Jeng and Wells (2000), getting the basic legal and tax structures into place appears to be an important factor influencing VC. Gompers and Lerner (1998) also recognize the importance of government decisions on the private equity funds. The labor market legislation is typically put in place to protect employees from arbitrary, unfair or discriminatory actions by employers. Some authors argue that venture financing can suffer from the rigidity of the labour market in Europe (e.g. Ramón and Marti, 2001). Jeng and Wells (2000) show that it does not significantly influence total VC but affects negatively the early stage of VC investment. According to Shertler (2003), labor market rigidities are significant and positive. That can be the result of differences in the labor-capital ratio of high-technology enterprises. He also argues that high-technology enterprises operating in rigid labor markets may demand more capital than comparable high-technology enterprises operating in flexible labor markets. With the clarification of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) prudent man” rule of 1979, the share of money invested by pension funds had risen to more than 50 %. Jeng and Wells (2000) find that the level of investment by private pension funds in VC is a

use a proxy for the amendment of the “prudent man” rule to show the impact of pension regulation and reach a similar conclusion. After 1979, the additional capital provided by pension funds led to a dramatic shift in commitments to VC.

Concerning the impact of the Capital Gains Tax Rate (CGTR) on VC activity, Gompers and Lerner (1998) show that a decrease in CGTR has a positive and important impact on commitment to new VC funds. In fact, they confirm the result of Poterba (1989) who built a model of decision to become an entrepreneur. He found that decreases in CGTR might increase the raising of VC funds not through stimulation of the supply side (i.e., the potential fund providers) but rather on the demand side. Indeed, decreases in CGTR often encourage entrepreneurship and thus the desire of people to create their own firm and to engage in R&D activities. Anand (1996) also highlights the fact that the level and composition of investments appear to be negatively affected by increases in the CGTR but investments in one industry may be affected by myriad of other factors like technology shifts, tastes, etc.

Both industrial and academic R&D expenditures are significantly related to venture capital activity at the State level in the model of Gompers and Lerner (1998). For them, the growth VC fundraising in the mid-1990s may be due to increases in technological opportunities. Shertler (2003) tests the number of employees in research and development and the number of patents as the approximation of the human capital endowment. He finds a positive impact of the number of R&D employees. Also, he highlights that the coefficients of the patent variable are positive and highly significant.

Concerning government programs for entrepreneurship, a main rationale of direct government intervention in the VC industry is the stimulation of economic growth.

to the VC industry. Some scholars have also focused on the micro determinants of VC. For Gompers and Lerner (1998) the individual firm performance and reputation, measured with the firm age and size, positively impact the capacity to raise larger funds. Hellmann and Puri (2000) use a probit model to show that the strategy of a company is one of the determinants of VC investment when controlling for the age of the company and its industrial sector. If the strategy is an innovative one (the company is the first to introduce a new product or service on the market), it has a higher probability to benefit from VC compared to companies that follow an imitation strategy (the company uses existing technologies to develop and improve products and processes). They also find that innovating companies are able to raise VC earlier in their life cycle than companies with a strategy of imitation. In other words, their analysis suggests that VC is stimulated by technological opportunities. However there is less evidence of such a relationship at the aggregate macroeconomic level.

In a nutshell, there are several potential determinants of VC. Some of them can be measured qualitatively or quantitatively at the macro level whereas others like the fund reputation and the strategy of the venture funded firms are microeconomic factors.

Romain and Pottelsberghe (2004) first develop a theoretical model which takes into account the factors that affect the demand and supply of VC. These factors include the growth of GDP, short-term and long-term interest rates, several indicators of technological opportunity, and of entrepreneurial environment. Second, they exploited a panel dataset composed of countries over an eleven years period. Third, they investigate to what extent the level of entrepreneurship and of labor market rigidities affect the impact of the GDP growth rate and the stock of available knowledge on VC intensity. The results showed that interest rates significantly influence VC intensity. The countries with lower labor market rigidities benefit from a higher impact of the GDP growth rate and the available stock of knowledge on the

relative level of VC. Higher levels of entrepreneurship – i.e., the percentage of people being involved in the creation of nascent firms – induce a positive and significant relation between the R&D capital stock and VC intensity. (Romain and Pottelsberghe, 2004)

A viable exit mechanism is extremely important to the development of a venture capital industry. Furthermore, an exit mechanism is essential to the entrepreneur for two reasons. First, it provides a financial incentive for equity-compensated managers to expend effort. Second, it gives the managers a call option on control of the firm, since venture capitalists relinquish control at the time of the IPO (Black and Gilson (1998). Jeng and Wells (2000) focused on IPOs as an exit mechanism for the following reasons. While there are many mechanisms to liquidate a fund, the literature shows that the most attractive option is through an IPO. A study conducted by Venture Economics 1988 finds that US$1.00 invested in a firm that eventually goes public yields a 195% average return or an average cash return of US$1.95 over the original investment for a 4.2-year average holding period. The same investment in an acquired firm only provides an average return of 40% or a cash return of only 40 cents over a 3.7-year average holding period. Also, if regaining control is important to the entrepreneur, IPOs are clearly the best choice, given that the other option, trade sales, frequently entails loss of control. Trade sales are sales of a startup company to a larger company also referred to as a strategic buyer.

Increased volume of IPOs should have a positive effect on both the demand and supply of venture capital funds. On the demand side, the existence of an exit mechanism gives entrepreneurs an additional incentive to start a company. On the supply side, the effect is essentially the same; large investors are more willing to supply funds to venture capital firms if they feel that they can later recoup their investment. (Jeng and Wells, 2000)