Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2003 • Vol 19 • No 7

A

SSOCIATION

B

ETWEEN

S

OCIAL

S

UPPORT

AND

H

EALTH

O

UTCOMES

: A M

ETA

-

ANALYSIS

Hsiu-Hung Wang,1 Su-Zu Wu,1 and Yea-Ying Liu1,2

1College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, and 2Institute of

Human Resources Management, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between social support and health outcome variables, and the effect size of social support on health outcomes. Meta-analysis was used to synthesize the primary studies identified initially from a computer search of the literature in Taiwan. Through preliminary screening related to the inclusion criteria, 165 dissertations and theses and 43 journal articles were included in this study. Finally, 182 primary studies, including 145 dissertations and theses and 37 journal articles, were retained after eliminating outliers of each outcome variable to achieve homogeneity. Based on Smith’s four modes of health, 16 health outcome variables were used. Health status, physical symptoms and responses, psychologic symptoms and responses, and depression were categorized as clinical variables. Role function and behaviors and role burden were categorized as role-function variables. Physical adjustment, psychosocial adjustment, adjustment of life, coping behavior, and stress were categorized as adaptive variables. Health belief, health promotion behavior, quality of life, well-being, and self-actualization were categorized as eudemonistic variables. Other than physical adjustment, social support could significantly predict all health outcomes (p < 0.0001). The results provided information not only on the magnitude of the sample size required to achieve statistical significance between social support and each outcome variable as a measure of health in future studies, but also on strategies to guide further intervention programs and to evaluate their effectiveness.

Key Words: social support, health, meta-analysis, effect size (Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2003;19:345–51)

Received: March 27, 2003 Accepted: May 14, 2003 Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr. Hsiu-Hung Wang, College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, 100 Shih-Chuan 1st Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan. E-mail: hhwang@kmu.edu.tw

Social support, in addition to its buffering effect, is considered to influence health directly [1–6] and to be capable of enhancing health [7–9]. Social support affects health in three ways: by regulating thoughts, feelings and behavior to promote health; by fostering an individual’s sense of meaning in life; and by facilitating health-promoting behaviors [1]. Weiss

proposed that an individual needs a set of relationships over the course of life, and that all these relationships are necessary for well-being [10]. Lack of social support may adversely affect health. Although a direct effect of social support on health has been asserted, the causal connections between these phenomena must be further examined [11].

Health care scholars have agreed that social support is a multidimensional construct with different types or kinds of social support. Emotional, appraisal, informational, instrumental, and tangible support are considered essential dimensions of social support [12, 13]. Some scholars have defined social support as relational provisions [10], interpersonal transactions

[14], or an individual perception about the adequacy or availability of different types of support [9]. In this study, social support was broadly identified as a multiple construct involving several theoretical components, including support network resources, supportive interactions, and perception or belief of support [15].

The literature has demonstrated that health is an important outcome measure for individuals with stressful life events. A variety of indicators of health have been presented in empirical studies. The indicators of health used in previous studies depended o n h o w h e a l t h w a s d e f i n e d . H e a l t h i s a multidimensional construct. The most useful concept of health is the one proposed by Smith [16], who identified four viewpoints. The conceptualization of health was based on these four modes: clinical, role-function, adaptive, and eudemonistic. The clinical mode is defined as absence of signs or symptoms of disease or disability and identified by medical science. The role-function mode is defined as performance of social roles with maximum expected output. The adaptive mode is defined as the individual maintaining flexible adaptation to the environment and interacting with the environment to maximum advantage. The eudemonistic mode is defined as exuberant well-being. Although social support and health have been major concepts in a number of research studies over the past decades, the influence of social support on health still appears to be inconclusive. Using meta-analysis on research studies may effectively address the relationship between social support and health. Meta-analysis, a quantitative method for summarizing existing studies, is defined as an analysis of analyses, that is, pooled results of several studies are analyzed to provide a systematic, quantitative review of their data [17]. Meta-analyses use statistical techniques to estimate effect size, and the magnitude and direction of the association between variables [5]. The purpose of this study was to use a meta-analysis to examine the relationship between social support and health, and to predict the effect of social support on health outcome variables.

M

ATERIALSANDM

ETHODSIn the preliminary examination of the literature, a computer search using the key words “social support”

and “health” was carried out. This identified 773 studies in the National Journal Articles Information Network and the Dissertations and Theses Information Network in Taiwan, dating back to 1984. Of these, 676 dissertations and theses and 97 research articles were examined.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: primary research study published in a peer-reviewed journal or unpublished dissertations and theses; measurement of social support; correlation of social support with outcome variables under the indicators of health; research data included correlations and at least one health outcome variable; and examination of the measures of social support and health variables for reliability and validity.

After preliminary screening, 208 primary studies, including 165 dissertations and theses and 43 research articles, met the inclusion criteria. All primary studies were published between 1984 and 2001. A coding sheet was designed to extract relevant information from each study. This consisted of a study identification number, inclusion criteria, characteristics of the publication, characteristics of the author(s), characteristics of the subjects, methodologic characteristics, descriptive data, and correlational data. Each outcome variable was examined according to the coding sheets. To ensure the reliability of the coding, 20 primary studies were randomly selected and then simultaneously coded by two coders. Inter-coder agreement was 98% of all coding items.

A summary table, made up of the variables, study number, sample size, correlation coefficient, and p value, was established to calculate the effect size of each outcome variable. To ensure the validity of this study, classification of health outcome variables based on Smith’s model of health [16] was evaluated by two experts; there was 95% agreement on categori-zation. The DSTAT computer program was used for analysis [18]. Correlation coefficients were used to determine the unweighted effect size (g). Based on sample size and unweighted effect size, every outcome variable was examined for its homogeneity between studies. Outliers of each variable were eliminated to achieve a homogenous state (p > 0.05), then the weighted effect size (d) of each health variable was determined. There were 182 primary studies, including 145 dissertations and theses and 37 journal articles, which were retained after outliers of each outcome variable were eliminated.

R

ESULTSSubject age in primary studies ranged from 15 to 83 years. Sample size ranged from 23 to 4,049. Of the 208 primary studies, 13 did not state gender distribution; in the remaining 195 studies, there were 1,735 females (42.85%) and 2,314 males (57.15%). In the 75 primary studies (36.1%) that listed chronic diseases, 9.6% of subjects had diabetes, 9.1% had heart disease, 7.2% had cancer, 5.8% had hypertension, and 2.9% had stroke. All primary studies were cross-sectional. Most studies (85.6%) used convenience sampling and 14.4% used random sampling to recruit subjects. All studies used questionnaires for data collection.

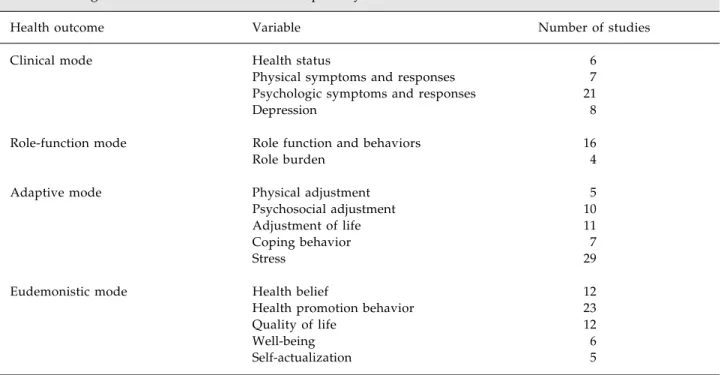

Based on Smith’s four modes of health [16], 16 health outcome variables were used. Health status, physical symptoms and responses, psychologic symptoms and responses, and depression were categorized as clinical variables. Role function and behaviors and role burden were categorized as role-function variables. Physical adjustment, psychosocial adjustment, adjustment of life, coping behavior, and stress were categorized as adaptive variables. Health belief, health promotion behavior, quality of life, well-being, and self-actualization were categorized as eudemonistic variables (Table 1).

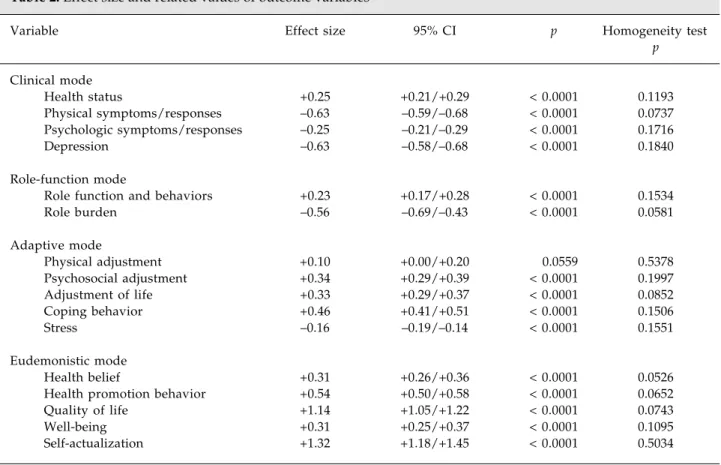

Other than the effect of social support on physical adjustment (p > 0.05), all the effect sizes of social support were significantly correlated with health outcome variables (Table 2). Social support had significantly positive effects on health status, role function and behaviors, psychosocial adjustment, adjustment of life, coping behavior, health belief, health promotion behavior, quality of life, well-being, and self-actualization. On the contrary, social support had significantly negative effects on physical symptoms and responses, psychologic symptoms and responses, depression, role burden, and stress.

D

ISCUSSIONThe findings indicated that individuals who obtained higher levels of social support might have more positive health status, role function and behaviors, psychosocial adjustment, adjustment of life, coping behavior, health belief, health promotion behavior, quality of life, well-being, and self-actualization. The individuals who obtained higher levels of social support might have less physical symptoms and responses, psychologic symptoms and responses, depression, role burden, and stress. As in Cohen’s study [19], social support

Table 1. Categorized health outcome variables in primary studies*

Health outcome Variable Number of studies

Clinical mode Health status 6

Physical symptoms and responses 7

Psychologic symptoms and responses 21

Depression 8

Role-function mode Role function and behaviors 16

Role burden 4

Adaptive mode Physical adjustment 5

Psychosocial adjustment 10

Adjustment of life 11

Coping behavior 7

Stress 29

Eudemonistic mode Health belief 12

Health promotion behavior 23

Quality of life 12

Well-being 6

Self-actualization 5

had a large effect on quality of life and self-actualization, while it had moderate effects on physical symptoms and responses, depression, role burden, coping behavior, and health promotion behavior, and a small effect on health status, psychologic symptoms a n d r e s p o n s e s , r o l e f u n c t i o n a n d b e h a v i o r , psychosocial adjustment, adjustment of life, stress, health belief, and well-being. These results provided information not only on the magnitude of the sample size required to achieve statistical significance between social support and each outcome variable as a measure of health in future studies, but also on strategies to guide further intervention programs and to evaluate their effectiveness.

A previous meta-analysis of 21 primary studies (that included only journal articles) published in the USA found that social support had a moderate effect on positive mood state (d = 0.54) and quality of life (d = 0.43), and a small effect on negative mood state (d = –0.34), depression (d = –0.32), and level of functioning (d = –0.31) [20]. In contrast, this study, using primary studies published in Taiwan,

categorized more diverse health outcome variables. In general, the findings of this study validate the previous study that social support can influence health outcomes. Smith’s characterization of health is hierarchical, ranging from the clinical mode, representing more traditional aspects of health, to the eudemonistic mode, embracing the relative, holistic concepts of well-being [16]. Our findings indicate that social support could effectively influence all levels of health outcome from clinical to role-function and adaptive modes to the eudemonistic mode.

Weiss asserted that social support is important because through it, society organizes the individual’s thinking and acting [21]. “Positive social support provides a context for learning effective coping strategies and for feedback to correct inappropriate action” [22]. The presence of social support may enhance motivation to engage in health promotion behaviors by meeting social interaction needs [23,24]. Both the main effect and buffering effect of social support have been hypothesized in previous studies [22,25]. The main effect of social support refers to that

Table 2. Effect size and related values of outcome variables

Variable Effect size 95% CI p Homogeneity test

p Clinical mode Health status +0.25 +0.21/+0.29 < 0.0001 0.1193 Physical symptoms/responses –0.63 –0.59/–0.68 < 0.0001 0.0737 Psychologic symptoms/responses –0.25 –0.21/–0.29 < 0.0001 0.1716 Depression –0.63 –0.58/–0.68 < 0.0001 0.1840 Role-function mode

Role function and behaviors +0.23 +0.17/+0.28 < 0.0001 0.1534

Role burden –0.56 –0.69/–0.43 < 0.0001 0.0581 Adaptive mode Physical adjustment +0.10 +0.00/+0.20 0.0559 0.5378 Psychosocial adjustment +0.34 +0.29/+0.39 < 0.0001 0.1997 Adjustment of life +0.33 +0.29/+0.37 < 0.0001 0.0852 Coping behavior +0.46 +0.41/+0.51 < 0.0001 0.1506 Stress –0.16 –0.19/–0.14 < 0.0001 0.1551 Eudemonistic mode Health belief +0.31 +0.26/+0.36 < 0.0001 0.0526

Health promotion behavior +0.54 +0.50/+0.58 < 0.0001 0.0652

Quality of life +1.14 +1.05/+1.22 < 0.0001 0.0743

Well-being +0.31 +0.25/+0.37 < 0.0001 0.1095

Self-actualization +1.32 +1.18/+1.45 < 0.0001 0.5034

which directly benefits well-being by fulfilling basic social needs and social integration [26]. The buffering effect refers to support that protects individuals from the potentially harmful influences of acutely stressful events and enhances their coping abilities [26]. Social support was hypothesized to have a main effect on health outcomes in this study; however, a buffering effect and its possible mechanism should be examined in future studies.

Various operational definitions and instruments used as measures of social support and health in primary studies might make findings difficult to i n t e r p r e t . H o w e v e r , t h e u s e o f m u l t i p l e operationalizations of social support (the predictor variable) and health (the outcome variable) provides an opportunity to capture a broader extent of the variables and facilitate construct validity [27]. The methodology of this study raised several concerns. First, locating studies for inclusion was difficult. The inclusion criteria relied primarily on the types of data analysis in the primary studies, and clues to the methods of data analysis were not generally recognizable from the titles or abstracts of the studies. As research questions often involved correlational and regression analyses secondary to the primary analyses, some potential studies had to be hand-searched to identify related studies. The second concern was the lack of complete data provided by primary studies. Pieces of data were extracted from various studies to create the dataset for this analysis. Although meta-analysis for research integration cannot take the place of primary studies to address causal relationships, it may provide useful guidelines for the direction of new primary research [27]. Future study should focus on testing causal models and explaining interrelations among social support and significant outcome variables of health. A comprehensive intervention design may help to verify the effectiveness of social support on health. Using social support as a strategy to promote individuals’ health should be the subject of future study in this area.

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors thank the National Science Council, Taiwan, for funding this research (NSC-89-2314-B-037-165).

R

EFERENCES1. Callaghan P, Morrissey J. Social support and health: a review. J Adv Nurs 1993;18:203–10.

2. Friedman MM. Social support sources and psychological well-being in older women with heart disease. Res Nurs Health 1993; 16:405–13.

3. Keeling DI, Price PE, Jones E, Harding KG. Social support: some pragmatic implications for health care professionals. J Adv Nurs 1996;23:76–81.

4. Logsdon MC, McBride AB, Birkimer JC. Social support and postpartum depression. Res Nurs Health 1994;17:449–57. 5. Smith CE, Fernengel K, Holcroft C, et al. Meta-analysis of the

associations between social support and health outcomes. Ann Behav Med 1994;16:352–62.

6. Yates BC. The relationships among social support and short-and long-term recovery outcomes in men with coronary heart disease. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:193–203.

7. Fink SV. The influence of family resources and family demands on the strains and well-being of caregiving families. J Nurs Res 1995;44:139–46.

8. Friedman MM, King KB. The relationship of emotional and tangible well-being among older women with heart failure. Res Nurs Health 1994;17:433–40.

9. Nelson G. Women’s life strains, social support, coping, and positive and negative affect: cross-sectional and longitudinal tests of the two-factor theory of emotional well-being. J Community Psychol 1990;18:239–63.

10. Weiss RS. The provisions of social relationships. In: Rubin Z, ed. Doing unto Others —Joining, Modeling, Conforming, Helping, Loving, 1st ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974:17–26. 11. Sauer WJ, Coward RT. The role of social support networks in

the care of the elderly. In: Sauer WJ, Coward RT, eds. Social Support Networks and the Care of the Elderly, 1st ed. New York: Springer, 1985:3–20.

12. House JS. Work Stress and Social Support. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1981.

13. Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med 1981;4:381–406.

14. Kahn RL, Antonucci TC. Convoys over the life course — Attachment, roles, and social support. In: Baltes BP, Brim OG, eds. Life-Span Development and Behavior, 1st ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1980:253–86.

15. Vaux A, Harrison D. Support network characteristics associated with support satisfaction and perceived support. Am J Community Psychol 1985;13:245–68.

16. Smith JA. The idea of health: a philosophical inquiry. Adv Nurs Sci 1981;3:43–50.

17. Conn VS, Armer JM. A public health nurse’s guide to reading meta-analysis research reports. Public Health Nurs 1994;11:163–7. 18. Johnson BT. DSTAT — Software for the Meta-Analytic Review of Research Literatures, 2nd ed. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993.

19. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 1st ed. New York: Halsted Press, 1977.

20. Wang HH. A meta-analysis of the relationship between social support and well-being. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1998;14:717–26.

21. Weiss RS. The fund of sociability. Transactions 1969;6: 36–43.

22. Gonzalez JT. Factors relating to frequency of breast self-examination among low-income Mexican American women. Cancer Nurs 1990;13:134–42.

23. Orem DE. Nursing: Concepts of Practice, 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

24. Maida CA. Social support and learning in preventive health care. Soc Sci Med 1985;21:335–9.

25. Lindsey-Davis L. Illness uncertainty, social support, and stress in receiving individuals and family care givers. Appl Nurs Res 1990;3:69–71.

26. Stewart MJ. Integrating Social Support in Nursing, 1st ed. Newbury Park, California: Sage, 1993.

27. Hall JA, Rosenthal R, Tickle-Degnen L, Mosteller F. Hypotheses and problems in research synthesis. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis, 1st ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1994:17–28.