Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Journal of Psychosomatic Research Manuscript Draft

Manuscript Number: JPR-2009-288

Title: Disease-specific quality of life measures as predictors of mortality in Type 2 diabetic patients

Article Type: Full Length Article

Keywords: Type II diabetes; Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales; Health-related quality of life; prognosis; survival

Corresponding Author: Dr. Cheng-Chieh Lin, MD, PhD

Corresponding Author's Institution: China Medical University Hospital First Author: Tsai-Chung Li, PhD

Order of Authors: Tsai-Chung Li, PhD; Chiu-Shong Liu, MD, MPH; Chia-Ing Li , MPH; Cheng-Chieh Lin, MD, PHD

Abstract: Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to examine whether the disease-specific quality of life measures are independent predictors of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods: A cohort of 420 diabetic patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of a medical center. At baseline, the disease-specific measure of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales

complications. When the scales of DIMS were simultaneously considered, only symptom and social role fulfillment of the DIMS exerted a significant effect on mortality. Patients in the categories of the 2nd and 3rd quartile (worse status) had significantly increased risk compared to those in the category of the 4th quartile (best status) (for the symptom scale, RR: 13.10, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.75-62.50; RR: 5.49, 95% CI: 1.50-20.09, respectively; for the social role fulfillment scale, RR: 6.18, 95% CI: 1.10-34.87; RR:6.53, 95% CI: 1.40-30.57).

Conclusions: Our data suggest that the unique contribution of the HRQOL to mortality was independent of more objective health measures, such as diabetes control and complications.

Dear Editor,

We would like to submit a paper “Disease-specific quality of life measures as predictors of mortality in Type 2 diabetic patients”, to the Journal of Psychosomatic

Research as an original article. Prior studies exploring the relationship between

HRQOL and mortality have focused on patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, kidney disease, advanced age, and cancer. To our knowledge, none of the previous studies have examined the effects of disease-specific quality of life measures on mortality in diabetic patients. Only one study reported prediction of mortality in type 2 diabetes from quality of life using generic measures of SF-36. The objective of the present study was to examine the ability of disease-specific quality of life measures in predicting mortality in a Taiwanese, outpatient-based, diabetic sample.

The authors declare that the material in this paper has not been reported or publicated, not has it been submitted for publication elsewhere.

Your sincerely Dr. Cheng-Chieh Lin

Disease-specific quality of life measures as predictors of mortality in Type 2 diabetic patients

Tsai-Chung Lia,b,c, Chiu-Shong Liud, Chia-Ing Lie, Cheng-Chieh Lind*

Institute of Biostatisticsa, Institute of Chinese Medicineb& Biostatistics Centerc, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

Department of Family Medicined, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

Department of Medical Researche, China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan

Suggested running title: Predictive ability of Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale on mortality

Correspondence: Cheng-Chieh Lin

Address: China Medical University Hospital 2 Yu-Der Road,

Taichung, 40421, Taiwan, R.O.C., Tel: 886-4-2205-2121 ext 6079 Fax: 886-4-22032295 e-mail: tcli@mail.cmu.edu.tw

Word count for paper “Disease-specific quality of life measures as predictors of mortality in Type 2 diabetic patients”: Text, 2433 words; Abstract, 247 words; Reference section, 853 words; Tables, 502 words.

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to examine whether the disease-specific quality of life measures are independent predictors of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods: A cohort of 420 diabetic patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of a medical center. At baseline, the disease-specific measure of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales (DIMS), and clinical and biological marker variables were measured. DIMS domains included symptoms, diabetes-related morale, social role fulfillment, and well-being. Complications consisted of stroke, heart disease, visual impairment, amputations, kidney disease, cognitive impairment, and incontinence. Mortality data were collected from the national mortality register using personal identification numbers. Multivariate Cox’s proportional hazards models were used.

Results: The overall mortality was 10.9%. The DIMS scales of symptoms and well-being, and the total score were significantly associated with mortality, independent of age, gender, and complications. When the scales of DIMS were simultaneously considered, only symptom and social role fulfillment of the DIMS exerted a significant effect on mortality. Patients in the categories of the 2nd and 3rd quartile (worse status) had significantly increased risk compared to those in the category of the 4th quartile (best status) (for the symptom scale, RR: 13.10, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.75-62.50; RR: 5.49, 95% CI: 1.50-20.09, respectively; for the social role fulfillment scale, RR: 6.18, 95% CI: 1.10-34.87; RR:6.53, 95% CI: 1.40-30.57).

Conclusions: Our data suggest that the unique contribution of the HRQOL to mortality was independent of more objective health measures, such as diabetes control and complications.

Keywords: Type II diabetes; Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales; Health-related quality of life; prognosis; survival

Introduction

The medical world has recognized the importance of the centrality of the patient point of view in monitoring the quality of medical care outcomes. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) focuses on the impact of a perceived health state on the ability to live a fulfilling life [1]. HRQOL of people with diabetes can be influenced by a complex diabetes treatment regimen that includes dietary behavior, exercise, medication, glucose monitoring, and safety and preventive measures. Patients frequently feel that their lives are negatively affected due to diabetes, partly because they have to integrate and coordinate the various components of the treatment regimen into their normal life activities [2]. On the contrary, as the disease

progresses, the effect of diabetic complications and the resultant risk of adverse drug experiences would have an impact on the medical outcomes of these patients [3]. To maximize the quality of life for people with diabetes is to attempt to strike a balance between an individual patient’s needs and desires and the imperatives of disease management.

A growing body of research shows that self-perceptions of health are linked to mortality, even when more “objective” health measures, such as morbidity [4,5], social support [5], and health behaviors [6], are controlled. A great value of the self-assessment of health lies in these findings. The unique contribution of health

perceptions to mortality is substantial for both the general population [7-10] and adult-onset diabetes [11]. These studies used a single indicator measuring the self-assessment of health, and some of them, a wide range of psychosocial and well-being measures. Prior studies exploring the relationship between HRQOL and mortality have focused on patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [12-13], congestive heart failure [14], coronary heart disease [15-16], kidney disease [17], advanced age [18], and cancer [19-24]. For a population with a specific disease, a disease-specific instrument should be more capable of detecting subtle improvements in health resulting from treatment while a generic instrument is more applicable when measuring the complete spectrum of function, disability, and disease that is relevant to quality of life. To our knowledge, none of the previous studies have examined the effects of disease-specific quality of life measures on mortality in diabetic patients. The objective of the present study was to examine the effects of disease-specific quality of life measures on mortality in a Taiwanese, outpatient-based, diabetic sample.

Methods

Study subjects

During the period 1998-2000, a Diabetes HRQOL study was conducted, consisting of 510 diabetes outpatients recruited from China Medical University Hospital (CMUH). Outpatients with a diagnosis of DM (International Classification Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, abbreviated as ICD-9-CM; Code of 250) were included in this study. Predominantly, subjects received oral hypoglycemic agents as treatment. Those who agreed to participate signed the consent forms and were interviewed by our trained interviewers during their outpatient visits. Their mean age was 62.98 years, with a standard deviation of 9.95 years, and 67.25% of them were female. Information regarding hemoglobin A1C, blood glucose levels

before and after meals, creatinine, urine protein, electrocardiogram readings, conduction deficit, and brain computed tomography (CT), was abstracted from hospital records.

HRQOL measures

The Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale (DIMS) is a measure of HRQOL in type I and type II adult diabetic patients. The scale was developed after a literature review, and its domains included symptoms, diabetes-related morale (attitude

towards managing the disease), social role fulfillment, and well-being. The scale requires 15-20 minutes to complete. Items are scored according to the selected response, with high values representing less severe or less frequent symptoms, greater morale, greater social role fulfillment, and greater well-being. Item responses were simply summed. The processes used in the translation of the Chinese version DIMS have been reported [25]. Validation of the DIMS in our baseline survey suggests that Chinese DIMS is a reliable and valid instrument, and appropriate in clinical settings for Chinese with diabetes.

The Vital Status Ascertainment of all patients through December 2005 was determined via yearly linkage with the National Death Index (1998-2005) using gender, identification number, and date of birth. The precise date of death along with the date of entry was used to calculate the event time. Those who did not die were defined as censored and data were censored on December 31, 2005.

Diabetes Status at Baseline

electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram were evaluated.

Blood chemistry analyses were performed in the Clinical Laboratory of CMUH by a biochemical autoanalyser (Beckman Coluter, Lx-20, USA). Diabetic control was measured by hemoglobin A1C (glycosylated hemoglobin), using

Boronate affinity and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (reference range 4.6-6.5%). The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for HbA1C were 2.91% for a normal level, 1.79% for an intermediate level, and 1.09%

for a high level. Urinary creatinine (Jaffe’s kinetic method) were also measured on the autoanalyser. The inter-assay precision CV was <3.0% for creatinine concentration. The lowest detection limit was <10 mg/dL for urinary creatinine. Blood pressure measurements were obtained using mercury manometers. Duration of diabetes was defined as the time interval between the time point of first diagnosis and the time point of being recruited.

The electrocardiogram (EKG) readings (Cardiovit AT10, Schiller, Switzerland) determined ischemic change. Ischemic change was defined as: EKG readings of an abnormal ST-T wave (or non-specific ST-T change); elevation or depression of the isoelectric segment following ventricular depolarization and preceding ventricular repolarization, measured from the end of the QRS complex to the beginning of the T wave; left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with strain, manifesting primarily as an

increase in voltage (height of R wave) in those EKG leads that reflect left ventricular potentials; suspected ischemia; old myocardial infarction (MI) (code 412.00 from ICD-9), with a negative Q wave in those EKG leads; and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (code 410.90 from ICD-9), with a negative Q wave and S-T segment elevation in those leads.

Neuropathy was determined by conduction deficit, which was measured by Nerve Conduction Velocity (Viking Select, Nicolet, USA). Patients were defined as having DPN if they had paresthesia or hypesthesia in all four limbs or in the lower extremities; or they who had neurologic abnormalities, including an abnormal Achilles reflex and the absence of a sense of vibration in the lower extremities; or they had their motor-nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) in the tibial nerve ranged between 30 and 48 m/s or if their sensory-nerve conduction velocity (SNCV) in the median nerve (in the distal area) ranged between 35 and 55 m/s. Retinopathy was evaluated by a fundus check-up by a physician. Skin ulcer was also determined by physician check-up.

using Cox’s proportional hazards models, then, added age, gender, glucose control and complication (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, skin ulcer, and ischemic change). Second, we used the continuous variables of the DIMS scales to test linear trends. Finally, we examined the association of the DIMS scales simultaneously to mortality. The PHREG of SAS 9.01 was used to fit the proportional hazards models.

Results

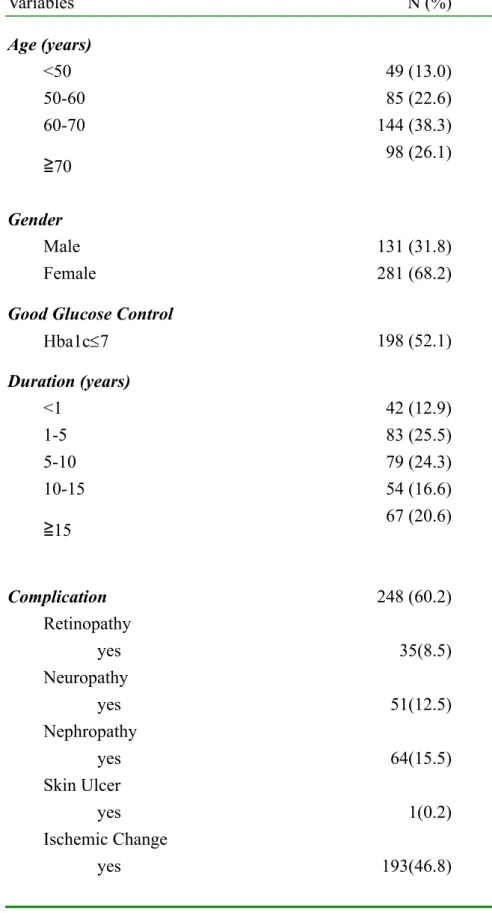

From August 1998 to March 2000, 510 patients were enrolled in the study. Since a personal identification number was needed to link with the National Death Index, those who didn’t provide a personal identification number or had missing information on the DIMS were excluded (n=90). The characteristics of 412 patients are shown in Table 1. A plurality of the study population was aged 60-70 years old (38.3%), and the group was predominantly female (68.2%). About half of them had good glucose control (52.1%) and 37.2% had more than 10 years of diabetes. Overall

complication prevalence was 60.2%. Specific complication conditions included retinopathy (8.5%), neuropathy (12.5%), nephropathy (15.5%), skin ulcer (0.2%), and ischemic change (46.8%).

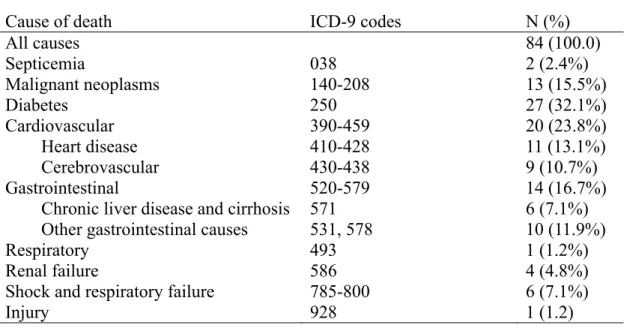

We documented 84 all-cause deaths (20.39%) during 17406 person-months (14060 for survivors and 3346 for decreased participants) of follow-up from 1998 to 2005. The main causes of death were diabetes, cardiovascular diseases,

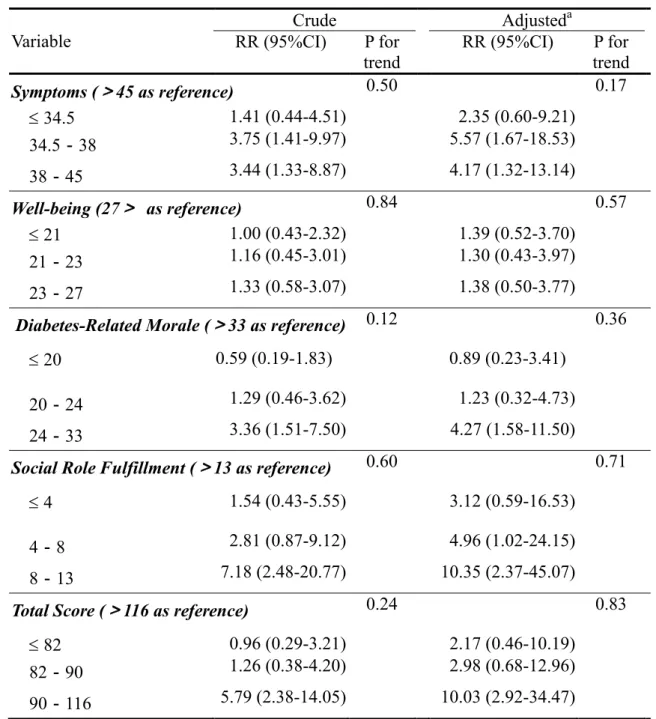

significant predictors of mortality (Table 3). After adjustment, they remained significant predictors. Compared with patients whose symptom scores were greater than 45, those whose symptom scores were 34-38, and 38-45 had RRs of 2.63 (95% CI, 1.18-5.85), and 2.46 (95% CI, 1.16-5.21), respectively; compared with patients whose diabetes-related morale scores were greater than 33, those whose

diabetes-related morale scores were 24-33 had a RR of 2.18 (95% CI, 1.06-4.47); compared with patients whose social role fulfillment scores were greater than 13, those whose social role fulfillment scores were 8-13 had RRs of 2.79 (95% CI, 1.20-6.44); and compared with patients whose total scores were greater than 116, those whose total scores were 90-116 had RR of 4.41 (95% CI, 2.04-9.5).

To further examine whether the independent relationship between DIMS scales and mortality, we performed a multivariate proportional hazards model by

simultaneously including 4 scales of the DIMS (Table 4). Symptoms and social role fulfillment were significant independent predictors of mortality. Compared with patients whose symptom scores were greater than 45, those whose symptom scores were 34-38, and 38-45 had RRs of 13.10 (95% CI, 2.75-62.5) and 5.49 (95% CI, 1.50-20.09), respectively. Compared with patients whose social role fulfillment scores were greater than 13, those whose social role fulfillment scores were 4-8 and 8-13 had RRs of 6.18 (95% CI, 1.10-34.87) and 6.53 (95% CI, 1.40-30.57), respectively.

Discussion

This study shows that disease-specific quality of life measures strongly predicted mortality in a cohort of persons with diabetes. After adjustment for age, gender, diabetic control, and complication status, scales of symptom, diabetes-related morale, social role fulfillment, and total score were strong and independent predictors of overall survival time. After simultaneously taking all scales into account, scales of symptom and social role fulfillment were the most informative variables that

improved the prediction of mortality besides the traditional clinical parameters. We observed the effects of symptom and social role fulfillment scales on mortality are independent from glucose control and complication because we had adjusted for the effects of glucose control and complication. The association between the symptom scale of the DIMS and mortality might be due to this symptom scale capturing some aspects of disease severity that glucose control and complication could not capture.

immune system and leave the individual more susceptible to opportunistic disease or cancer [26]. The other is that the conceptual definition of this scale reflects the level of life control. Thus, this predictive value of the social role fulfillment scale could be caused by a delay in taking health-protective and health-maintaining actions, due to the lack of control in the patient’s life. However, the current study was not up to the task of explaining these observed relationships.

The persistent effect of disease-specific quality of life measures on mortality amongst persons with diabetes, despite extensive disease severity controls, may be due to the inability of medical and social science to adequately model the complex, chronic, multiple interacting illnesses. The findings of our study do provide evidence that quality of life measures add finer-graded information about health related to survival. The predictive power of these measures confirms the importance of the centrality of the patient point of view - that is, what people say about themselves to health professionals - in monitoring the quality of medical care outcomes.

Previous studies indicated that pre-treatment HRQOL is a significant factor for survival time in cancer patients. Our finding that cross-sectional HRQOL in patients with diabetes is also a significant factor for survival outcome and this has also

important implications: the assessment of HRQOL in patients with diabetes should be integrated into clinical practice and evaluated periodically to adequately monitor the

outcome of regular follow-up visits. In addition, the independent predictive value of DIMS scales for these patients suggests that a better HRQOL score reflecting less symptoms and better social role fulfillment (e.g., less personal distress and/or social problems) would have better overall survival. In our opinion one of the therapeutic goals of HRQOL is to facilitate communication between patients and doctors and help doctors provide care based on patients’ symptoms in the aim to improve overall survival by controlling impact of disease and preserving or improving HRQOL.

A number of limitations should be noted in interpreting the results of this study. The diabetic patients in this study were recruited during their office visits and had relatively better glucose control. The predictive ability of the DIMS might be less in a diabetic population representing a more severe spectrum of disease. This might limit the generalizability of the results, but should not affect the internal validity. In addition, there exists the possibility of a DIMS measurement error. This kind of measurement error might be random or differential. If such a measurement error is independent of mortality, i.e., due to random error, the biased results in the effect may

measurement error jeopardizing the validity of our results should be small. In conclusion, HRQOL provides additional clinical information regarding disease course and outcome that is not captured by traditional indexes of clinical status. Scales of DIMS were strong predictors of mortality amongst persons with diabetes, and their predictive power was only slightly explained by age, gender, glucose control, and complication. When DIMS scales were simultaneously

considered, only symptom and social role fulfillment scales exerted an independent effect on mortality. The results show the clinical importance of the HRQOL and may facilitate interpretation by clinicians.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CCL and TCL designed the study and drafted the manuscript. CSL, and CIL carried out the study, participated in coordination and evaluation of data. TCL, and CIL carried out the data organization and performed the statistical analysis. CCL and TCL contributed to the study with their knowledge on field study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a 2-year grant from the National Council of Science, Taiwan (NSC 88-2314-B-039-009 and NSC 89-2320-B-039-004). The authors express their special thanks to the interviewers who participated in recruiting participants and data collection.

number of deaths from the main causes of death

Table 3. Crude and adjusted relative risks of five-year mortality for 4 scales and total score of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale amongst individuals with

non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Table 4. Multivariate relative risks of five-year mortality for 4 scales of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale amongst individuals with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

References

[1] Bullinger M, Anderson R, Cella D, and Aaronson N. Developing and evaluating cross-cultural instruments from minimum requirements to optimal models. Quality of Life Research 1993; 2:451-9.

[2] Hanestad BR, Albrektsen G. Quality of life, perceived difficulties in adherence to a diabetes regimen, and blood glucose control. Diabetic Med 1991; 8: 759-764.

[3] O’Connor PJ, Jacobson AM. Functional status measurement in elderly diabetic patients. Clin Geriatr Med 1990;6:865-882.

[4] Menec VH, Chipperfield JG, Perry RP. Self-perceptions of health: A prospective analysis of mortality, control, and health. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological sciences 1999; 54B (2): 85-93.

[5] McCallum J, Shadbolt B & Wang D. Self-rated health and survival: A 7-year follow-up study of Australian elderly. American Journal of Public Health 1994;

Longitudinal Study of Aging, 1984-1986. J Clin Epidemiol 1995; 48:375-87. [8] Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, et al. Self-rated health status as a health measure:

the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician

services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50:517-28.

[9] Sundquist J, Johannson SE. Self reported poor health and low educational level predictors for mortality: a population-based follow-up of 39,156 people in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 1997;51:35-40..

[10] Heistaro S, Jousilahti P, Lahelma E, Vartiainen E, Puska P. Self-rated health and mortality: a long-term prospective study in eastern Finland. J Epidemiol

Community Health 2001; 55:227-232.

[11] Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in people with diabetes. Am J public Health 1994;84:1775-9.

[12] Sprenkle MD. Niewoehner DE. Nelson DB. Nichol KL. The Veterans Short Form 36 questionnaire is predictive of mortality and health-care utilization in a population of veterans with a self-reported diagnosis of asthma or COPD. Chest 2004; 126(1):81-9.

[13] Domingo-Salvany A. Lamarca R. Ferrer M. Garcia-Aymerich J., et al. Health-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine 2002; 166(5):680-5.

[14] Konstam V. Salem D. Pouleur H. Kostis J, Gorkin L, et al. Baseline quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization in 5,025 patients with congestive heart failure. SOLVD Investigations Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction Investigators. Am J of Cardio 1996; 78(8):890-5.

[15] Bosworth HB. Siegler IC. Brummett BH. Barefoot JC, et al. The association between self-rated health and mortality in a well-characterized sample of coronary artery disease patients. Medical Care 1999; 37(12):1226-36. [16] Rumsfeld JS, MaWhinney S, McCarthy M Jr., Shroyer AL, VillaNueva CB,

O’Brien M et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Participants of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Processes, Structures, and Outcomes of Care in Cardiac Surgery. JAMA 1999, 281:1298-1303.

quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging-Clinical & Experimental Research 2002; 14(6): 499-508.

[19] Dharma-Wardene M, Au HJ, Hanson J et al. Baseline FACT-G score is a predictor of survival for advanced lung cancer. Quality of Life Reseach 2004; 13: 1209–1216.

[20] Efficace, F., Biganzoli, L., Piccart, M., et al. Baseline health-related quality of life data as prognostic factors in a phase III multicentre study of women with metastatic breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer 2004; 40, 1021–1030. [21] Fang, F. M., Tsai, W. L., Chiu, H., et al. Quality of life as a survival predictor

for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation, Biology, Physics 2004; 58, 1394–1404.

[22] Chau, I., Norman, A. R., Cunningham, D., et al. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer-pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trails using individual patients data. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2004; 22, 2395–2403.

[23] Kaplan MS, Berthelot JM, Feeny D, McFarland BH, Khan S, Orpana H, the predictive validity of health-related quality of life measures: mortality in a longitudinal population-based study. Qual Life Res 2007; 16:1539–1546

Masskouri F, Barbare JC, Bedenne L. Quality of life as a prognostic factor of overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from two French clinical trials. Qual Life Res 2008: 17:831–843.

[25] Li, T.C., Lin, C.C., Li, C.I. Validation of the Chinese-version Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales Among People with Diabetes. Qual Life Res 2003; 12 (12): 804.

[26] Eisdorfer, Carl and Francis Wilkie. “Stress, Disease, Aging, and Behavior.” In James E. Birren and K. Warner Schaie (Eds), Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Table 1. Distributions of age, gender, complications, glucose control and co-morbidity in the study sample

Variables N (%) Age (years) <50 49 (13.0) 50-60 85 (22.6) 60-70 144 (38.3) ≧70 98 (26.1) Gender Male 131 (31.8) Female 281 (68.2)

Good Glucose Control

Hba1c7 198 (52.1) Duration (years) <1 42 (12.9) 1-5 83 (25.5) 5-10 79 (24.3) 10-15 54 (16.6) ≧15 67 (20.6) Complication 248 (60.2) Retinopathy yes 35(8.5) Neuropathy yes 51(12.5) Nephropathy yes 64(15.5) Skin Ulcer yes 1(0.2) Ischemic Change yes 193(46.8)

Table 2. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes and observed number of deaths from the main causes of death

Cause of death ICD-9 codes N (%)

All causes 84 (100.0) Septicemia 038 2 (2.4%) Malignant neoplasms 140-208 13 (15.5%) Diabetes 250 27 (32.1%) Cardiovascular 390-459 20 (23.8%) Heart disease 410-428 11 (13.1%) Cerebrovascular 430-438 9 (10.7%) Gastrointestinal 520-579 14 (16.7%)

Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis 571 6 (7.1%)

Other gastrointestinal causes 531, 578 10 (11.9%)

Respiratory 493 1 (1.2%)

Renal failure 586 4 (4.8%)

Shock and respiratory failure 785-800 6 (7.1%)

Table 3. Crude and adjusted relative risks of five-year mortality for 4 scales and total score of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale amongst individuals with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Variable Crude Adjusteda RR (95%CI) P for trend RR (95%CI) P for trend Symptoms (>45 as reference) 0.50 0.17 34.5 1.41 (0.44-4.51) 2.35 (0.60-9.21) 34.5-38 3.75 (1.41-9.97) 5.57 (1.67-18.53) 38-45 3.44 (1.33-8.87) 4.17 (1.32-13.14) Well-being (27> as reference) 0.84 0.57 21 1.00 (0.43-2.32) 1.39 (0.52-3.70) 21-23 1.16 (0.45-3.01) 1.30 (0.43-3.97) 23-27 1.33 (0.58-3.07) 1.38 (0.50-3.77)

Diabetes-Related Morale (>33 as reference) 0.12 0.36

20 0.59 (0.19-1.83) 0.89 (0.23-3.41)

20-24 1.29 (0.46-3.62) 1.23 (0.32-4.73)

24-33 3.36 (1.51-7.50) 4.27 (1.58-11.50)

Social Role Fulfillment (>13 as reference) 0.60 0.71

4 1.54 (0.43-5.55) 3.12 (0.59-16.53)

4-8 2.81 (0.87-9.12) 4.96 (1.02-24.15)

8-13 7.18 (2.48-20.77) 10.35 (2.37-45.07)

Total Score (>116 as reference) 0.24 0.83

82 0.96 (0.29-3.21) 2.17 (0.46-10.19)

82-90 1.26 (0.38-4.20) 2.98 (0.68-12.96)

90-116 5.79 (2.38-14.05) 10.03 (2.92-34.47)

Table 4. Multivariate relative risks of five-year mortality for 4 scales of the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale amongst individuals with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Variable

Adjusted RRa(95%CI) P for trend

Scores of the DIMS

Symptoms (>45 as reference) 0.23 34 5.42 (0.99-29.69) 34-38 13.10 (2.75-62.50) 38-45 5.49 (1.50-20.09) Well-being (27> as reference) 0.60 21 0.67 (0.21-2.15) 21-23 0.88 (0.23-3.34) 23-27 0.67 (0.22-2.08)

Diabetes-Related Morale (>33 as reference) 0.03

20 0.21 (0.04-1.19)

20-24 0.32 (0.06-1.64)

24-33 2.37 (0.71-7.91)

Social Role Fulfillment (>13 as reference) 0.43

4 3.30 (0.48-22.50)

4-8 6.18 (1.10-34.87)

8-13 6.53 (1.40-30.57)