台灣EFL學生回應間接抱怨的研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(3) A STUDY ON TAIWANESE EFL LEARNERS’ RESPONSES TO INDIRECT COMPLAINTS. Presented to Department of English,. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 A Master Thesis National Chengchi University. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Suwen Ang June 2012.

(4) The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Suwen Ang defended on July 20, 2012.. ____________________________ Ming-chung Yu Professor Directing Thesis. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ____________________________ Chi-Yee Lin Committee Member. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. ____________________________ Chia-Yi Lee Committee Member. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Approved:. _________________________________________________________________ Chih Hsin Lin, Chair, Department of English.

(5) To The Honored Accredited Prestigious Teacher of NCCU The teacher who made magic happen My lifetime mentor. Dr. Ming-chung Yu 獻給我的恩師 余明忠教授. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(6) Acknowledgements My warmest thanks go to Dr. Ming-chung Yu, my advisor in the Department of English of National Chengchi University, who had introduced me the fascinating study of cross-cultural pragmatics and guided me throughout the research. He is a great teacher. He cares about students; he inspires and provokes deep thought.. 政 治 大. Throughout the past few years, he encouraged me and stood by me when I was stuck. 立. and in need of help.. ‧ 國. 學. My gratitude extends to other committee members, Dr. Chi-Yee Lin and Dr. Chia-Yi Lee, who spent time reviewing the paper and provided additional guidance to. ‧. this study.. sit. y. Nat. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Yuen-Mei Yin who encouraged me to pursue. n. al. er. io. graduate study. Thanks to her that I have the honor to be part of the ETMA program.. v. The learning from this program had expanded my view of language teaching and. Ch. engchi. i n U. helped me become a better elementary school English teacher.. I would like to extend my heart-felt thanks to my best friend, a model teacher, Kate Lu, for her tireless reminders and encouragement in the process of the work. She helped me with data categorization and review. Special thanks go to my cousin, Dr. Amy Wong, who allowed me to call her at 3am and never gave me up. Her encouragement kept me going throughout the process, and her everlasting support contributed to the completion of this work. Finally, I thank my parents for their unconditional love and support. They accept me as their beloved daughter though I am so slow in progress. iv.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... IV CHINESE ABSTRACT ............................................................................................ VIII ENGLISH ABSTRACT ........................................................................................... VIII CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1. 政 治 大. PURPOSE OF STUDY ..................................................................................................... 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY ...................................................................................... 4. 立. CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................... 5. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. SPEECH ACT THEORY .................................................................................................. 5 COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE.................................................................................. 7 BROWN AND LEVINSON’S POLITENESS FRAMEWORK ................................................ 11 CULTURE DIFFERENCE .............................................................................................. 13 PRAGMATIC TRANSFER ............................................................................................. 14 THE SPEECH ACT OF COMPLAINTS ............................................................................ 15 Previous Studies ................................................................................................... 15 VARIABLES OF INDIRECT COMPLAINTS ..................................................................... 16 Theme.................................................................................................................... 16 Social status .......................................................................................................... 17 Social Distance ..................................................................................................... 17 Gender Differences ............................................................................................... 18 RESEARCH QUESTIONS .............................................................................................. 18. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ............................................................... 19 PARTICIPANTS ........................................................................................................... 19 Targeted EFL Group ............................................................................................ 19 Cultural Baseline Groups ..................................................................................... 23 HIGH INTERNAL VALIDITY ........................................................................................ 24 INSTRUMENTS ........................................................................................................... 24 Discourse Completion Task (DCT) questionnaire ............................................... 25 Questionnaire design ............................................................................................ 26 Categorization of the strategy used ...................................................................... 29 PROCEDURES ............................................................................................................. 33 Data Collection and Coding Scheme.................................................................... 33. v.

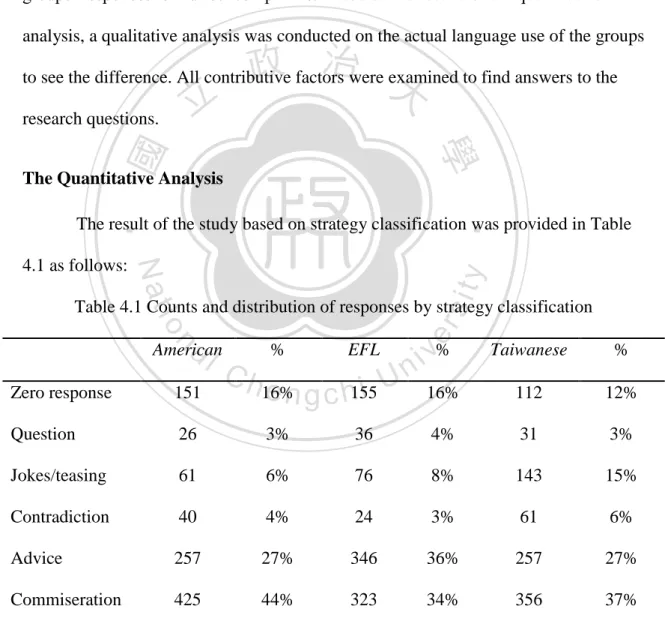

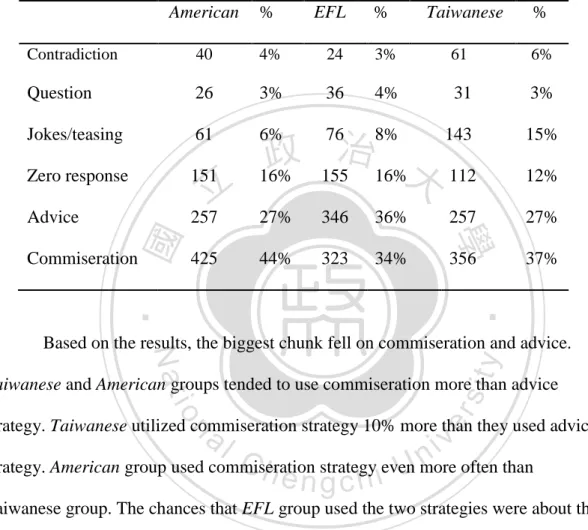

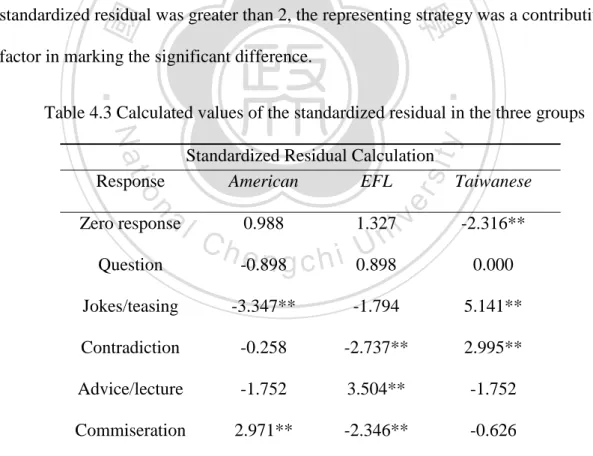

(8) Data analysis ........................................................................................................ 34 CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND FINDINGS ................................................... 45 THE QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS ................................................................................. 45 Statistical Analysis................................................................................................ 47 CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION............................................................................. 73 CONTRAST AND COMPARISON WITH THE FINDINGS IN PREVIOUS STUDIES................ 73 Take a Closer Look ............................................................................................... 75 THE NATIVE GROUPS ................................................................................................ 78 EFL GROUP ............................................................................................................... 79 A Contrast with Bulge Theory .............................................................................. 79 CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSION ............................................................................. 87 SUMMARY OF THIS STUDY ........................................................................................ 87 PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATION ..................................................................................... 88 LIMITATIONS ............................................................................................................. 88 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE STUDY ................................................................. 89. 學. . ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 . ‧. . REFERENCES ............................................................................................................ 90. Nat. sit. y. APPENDIX A ........................................................................................................... 96. al. er. io. APPENDIX B ......................................................................................................... 108. n. APPENDIX C ......................................................................................................... 120. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(9) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:台灣 EFL 學生對間接抱怨回應的研究 指導教授:余明忠先生 研究生:翁淑玟 論文提要內容:. 立. 政 治 大. 本研究主要在探討台灣的大學裡的英語學習者(EFL)在學習英文到全. ‧ 國. 學. 民英檢中級以上的程度後,面對間接抱怨的語言行為所採取的回應對策狀況。. ‧. 對照同樣情況下,以英文為母語的美國大學生,和以中文為母語的台灣大學生. sit. y. Nat. 所採取行的行為回應,了解文化是否會在語言學習過程中影響語言學習者的語. n. al. er. io. 言行為表現。研究者探索其語言表現,希望提供語言教育者課程設計的參考。. i n U. v. 研究的三組受試人分別為 40 位英語學習程度佳的台灣大學生,40 位以英語為. Ch. engchi. 母語的美國大學生,以及 40 位以中文為母語且以中文為學習主要媒介的台灣的 大學生。蒐集語言資料的工具是語言言談情境問卷(Discourse Completion Task,簡稱 DTC),依照收集到的語言資料進行分析。研究結果顯示:三組回 應間接報怨的表現習慣有很大的差異,台灣組的表現較為樂觀積極,會營造輕 鬆的氣氛並提醒繼續下一個生活步驟。美國組則謹慎小心,較會以了解與提供 事實解釋來安慰抱怨者。英語學習者回應的行為看起來好像與美國人的採用的 行為對策類似,但受到本身文化的影響,學習者在文字表達,有語用轉移的現 象,即語言學習者與台灣組在面對間接抱怨時所採用的用字及表達較為接近。 vii.

(10) Abstract. This study investigated Taiwanese university students’ response strategies to indirect complaints in English. The response differences were compared among those of native speakers of American English and those of Mandarin Chinese. Participants in the study were 40 learners of English living in Taiwan, 40 native speakers of. 政 治 大. American English living in the United States and 40 native speakers of Mandarin. 立. Chinese living in Taiwan. The learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) were. ‧ 國. 學. with an intermediate to high intermediate English proficiency level. By comparing and contrasting the data collected from native speakers of American English living in. ‧. the United States and native speakers of Mandarin Chinese living in Taiwan, we. y. Nat. io. sit. found the results informative for English course designers in Taiwan. The instrument. n. al. er. used in the study was Discourse Completion Task (DCT). Based on the collected data,. Ch. i n U. v. the researcher performed both qualitative and quantitative analysis and concluded that. engchi. the three groups responded significantly differently toward indirect complaints. Taiwanese tended to give advice to their interlocutors and they liked to maintain convivial atmosphere in communication. Americans commiserated their interlocutors mainly based on facts and sympathy. EFL learners were found to bear great similarity with Americans in strategy taking when responding to indirect complaints, but if comparisons were made on the actual wordings used by the three groups, the wordings that the EFL learners used resembled Taiwanese group’s preferences which might be a result of cultural influence. viii.

(11) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Living in a community, people find ways to negotiate with others for their desires and displeasure. When people share a mother tongue, they understand one another much easier, but even such is the case, there is no guarantee of smooth. 政 治 大 comprehending others turns out to be much more challenging. People have to use a 立 communication. But, when people speak different languages, communication and. ‧ 國. 學. common language as a communication tool. English is one of the commonly used languages around the world and it is often the tool used in communication for many. ‧. people.. sit. y. Nat. Sometimes people who have a good command of English got misunderstood.. io. er. In Taiwan and in many Asian countries, learning English in school has become. al. mandatory for elementary school students. English, as a global language, is now. n. v i n spoken by more non-native C speakers native speakers. Non-native speakers use h e nthan gchi U English as a tool to communicate with people around the world. There are risks: for even if non-native speakers know well the literal meaning and the grammatical structure of English yet if they are not aware of the allusive meaning behind the words; they might still experience a pragmatic failure. Misunderstanding may occur, and that might create troubles and difficulties in communication (Thomas, 1983). They are unable to carry on conversations as intended. Boxer (1993) reasoned a possible explanation for the misunderstanding: native speakers understand nonnative speakers have phonological, syntactic and lexical errors due to limited control 1.

(12) of English; but native speakers typically interpret errors of non-native speakers’ sociolinguistic offense as breaches of etiquettes rather than misuse or mal-transfer of different sociolinguistic rules. Therefore, it is necessary to show people from different backgrounds how to use English properly in contexts (Yu, 1996). Thus, one of the language teacher’s responsibilities is to introduce students how native speakers use their language and help them properly express themselves and carry on meaningful and sustainable communication as they want. Native speakers acquire sociolinguistic rules “naturally” in everyday. 治 政 大 the issue if they are taught with this information. Widdowson (1978) raised 立. conversation, but non-native speakers do not have access to such knowledge unless. sociolinguistic rules should be and could be taught. Researchers have found that. ‧ 國. 學. teaching sociolinguistic norms and rules are helpful for non-native speakers. It raises. ‧. language learners’ awareness in the speaking behaviors and patterns of native. sit. y. Nat. speakers and it helps language learners facilitate meaningful communication.. io. er. Why and how do interlocutors successfully converse with others? The basic. al. idea is that interlocutors obey certain principles to converse successfully; and these. n. v i n Cdifferent. principles in languages are somehow people in different languages h e n gHow chi U. observe the sociolinguistic principles and use the languages has become an interesting topic in the studies of pragmatics. “The main function of language is to use it in real communication rather than to learn the grammatical rules”, Widdowson (1978) properly defined the function of language. This exactly explained why the studies of pragmatics have played a vital part in language teaching for more than three decades. Many studies on pragmatics explore second language learners’ utterances of speech acts cross-culturally, like request, compliment, complaint, and refusal (e.g. 2.

(13) Blum-Kulka, et al. 1989; Kasper & Rose, 1999, 2002; Rose, 1992; Thomas, 1983; Yu, 1997, 1999). With all the speech acts compared, indirect complaint turns out to be a less studied domain but not a less dramatic speech act. Complaints are often thought as a negative evaluation in opinions. Yet Boxer (1993) observed native speakers’ language and found tacit values in indirect complaints. Indirect complaints built rapport solidarity like other well studied speech acts, and they often opened communication as a result. Boxer (1989) claimed that indirect complaints (IC) played a substantial role as conversation opener and built rapport solidarities. Through these. 治 政 no research focused EFL learners’ responses toward大 indirect complaints had been 立. studies, people observed how English had worked on its learners. However, little or. conducted in Taiwan. The lack of research on this topic motivated this researcher to. ‧ 國. 學. study on how English had worked on EFL students in Taiwan, and what could be. ‧. learned from the studies.. Nat. sit. y. Purpose of Study. n. al. er. io. The purpose of the study was to investigate EFL learners’ responses to indirect. i n U. v. complaints in Taiwan. By comparing and contrasting the findings of Boxer’s research. Ch. engchi. (1993) on the language behaviors of native speakers of English, this research should help English language program designers in Taiwan integrate sociolinguistic norms and values of different cultures and provide options of appropriate behaviors for language learners. The findings of this research should provide insight for language teachers when working on lesson plans for English learners in Taiwan. For with more properly designed programs attending to students’ own culture and targeted foreign culture awareness, learning a new language could be made illustratively easy and rewarding. 3.

(14) In this study, the researcher set up various contextual situations for university students to respond upon. In order to compare how exactly people of different cultures respond to some set situations, the researcher collected responses from native speakers of American English in the US and responses from native speakers of Mandarin Chinese in Taiwan to serve as baseline information. With a focus on indirect complaint (IC) interactions, a pedagogical implication would be established. Significance of the Study This research explored in depth English learners’ responses to indirect. 政 治 大. complaints. Boxer (1993) applied ethnographical research method of participating. 立. observation and recorded the responses of indirect complaints in a university. ‧ 國. 學. community on functions of gender, social status and social distance. All data were categorized in a place of fit. The findings provided researchers with a bird’s-eye view. ‧. of patterns and functions of the speech act in question. Based on the results of Boxer’s. y. Nat. sit. (1993) research, this study worked on contextual situations for students of one. n. al. er. io. common speech community and observed how the language learners affirmed or. i n U. v. rejected the choice of strategies when they were responding to indirect complaints in. Ch. engchi. utterances. This would provide language teachers with empirical information in instructing pragmatics for English learners.. 4.

(15) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Speech Act Theory Speech acts are speakers’ utterances, which convey meaning and make listeners do specific things (Austin 1962). The primary concept of speech acts is that. 政 治 大 determined by the context where multiple factors affect the speaker’s utterances. 立 various functions can be implemented by means of languages. Speech acts are. ‧ 國. 學. According to Searle (1975), when giving out a performative utterance, a speaker is simultaneously doing something. For example, when someone said, “I am. ‧. hungry,” he literally expressed his hunger and more importantly, he showed his. sit. y. Nat. intention for some food or even a request to have something to eat. Austin (1962). n. al. er. io. indicated that people performed three different kinds of acts when speaking.. i n U. v. 1. Locutionary acts: they referred to the utterances used, which were the. Ch. engchi. literal meanings. They’re acts of saying.. 2. Illocutionary acts: they referred to the intention that speakers had or the effects that the utterances wanted from the listeners. They were often used to perform certain functions and needed to be performed ‘intentionally’ (Searle, 1979). They’re acts in saying. 3. Perlocutionary acts: they referred to the results or effects produced by means of speakers’ illocutionary acts. They’re acts by saying.. A speaker can use different locutionary acts to achieve one illocutionary force or 5.

(16) use one locution for many different purposes. For instance, when someone asking, “Can you pass the salt?”; he/she had the literal meaning concerning the listener’s ability to pass salt while the illocutionary act was to request the listener to pass the salt for the speaker. If the illocutions caused listeners to do something, they were perlocutionary acts. In short, the purpose of the speech act was for the listener to pass the salt. The locutionary act caused the illocutionary force that the speaker wanted the utterance to have on their listeners. One could perform his/her intention indirectly by using illocutionary acts to provoke perlocutionary acts. The illocutionary acts in Austin’s original framework were what subsequent researchers. 治 政 大 called pragmatic called speech acts, illocutionary force, or what Thomas (1995) 立 force. Today most attention has especially focused on illocutionary acts, the. ‧ 國. 學. speakers’ actual purpose of utterances. Illocutionary acts are categorized by. ‧. language functions or by their intents (Hymes, 1962; Austin, 1962).. sit. y. Nat. Austin (1962) classified speech acts into five types, and later Searle (1969). io. er. refined the typological system (here written in brackets):. al. n. 1. Directives (Verdictives): an intention to get the listener to do something,. i n C such as request, command, h advice, and invitation. engchi U. v. 2. Declaratives (Exercitives): the exercising of power and rights or a completion of a change by the correspondence between the utterance and the illocutionary force, as in appointing, warning, and ordering. 3. Commissives (Commissives): an action that the speaker undertakes or commits to do something by announcing an intention, like promising. 4. Expressives (Behabitives): a psychological expression that shows the sincerity condition about certain affair, such as complaint, apology, gratitude, or congratulation. 6.

(17) 5. Assertives (Expositives): a reference to the truth of the expressed utterance, as in argument or statement.. Austin (1962) pointed out that speech acts must meet felicity conditions to carry out the intended function. In order to make illocutionary acts successfully performed, Searle (1969) suggested four necessary conditions: they were preparatory condition, sincerity condition, propositional content condition, and essential condition. Communicative Competence. 政 治 大. Communicative competence is a concept originated by Dell Hymes (1972) to. 立. contrast with linguistic competence founded by Noam Chomsky (1965). Hymes. ‧ 國. 學. defines communicative competence as the ability to use a language appropriately in different social contexts. In other words, it is the ability to judge on how, when, where. ‧. and to whom one should talk. According to Hymes (1972), a speech act is the smallest. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. follows:. sit. unit of speech in a speech behavior. Details of the speech units were illustrated as. i n U. v. 1. Speech community: the community that shares linguistic and cultural rules.. Ch. engchi. 2. Speech situation: the type of situation, for example, a ceremonial situation, a fighting situation, etc. 3. Speech event: the actual physical event, such as a speech at a party. 4. Speech act: the smallest unit within a speech event, such as a request, a joke, or greetings. (Hymes, 1972, pp. 59-60). 7.

(18) Furthermore, Hymes provides a useful schema for analyzing components of speech behaviors with the acronym SPEAKING: S: scene or setting (e.g., formal vs. informal) P: partner (the relationship between hearer and speaker) E: end (goal of the speech) A: act (sequence of the speech act) K: key (manner, e.g., sarcastic or friendly) I: instrumentation (e.g., oral or written). 治 政 大 G: genre (e.g., poetry, political speech) 立 N: norm of the culture in speech behavior. (Hymes, 1972, pp. 64-65). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. In studying the speech act of responses to indirect complaints, we followed. Nat. sit. y. Hyme’s ideas. The main setting in this research was a speech community of a. n. al. er. io. university, and the speech situations were events of students’ daily life experience and the speech acts were responses to indirect complaints.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Foreign language learners maybe eloquent speakers in target language when communicating with others, after all they have acquired and mastered grammatical and linguistic accuracy yet they may still face serious troubles; without knowing sociolinguistic rules of the target language, learners run the risk of being misunderstood for not saying the right thing at the right time. As a result, there has been a movement encouraging studies on sociolinguistic rules and these studies help enhance communicative competence of the language learners. A vital part of the ongoing movement is on various studies of speech act. Empirical studies have 8.

(19) contributed significantly to avoid cross cultural miscommunication. Studies of different culture backgrounds are popular in English, Spanish, and Japanese, yet little attention has been paid to native Chinese speakers’ language behavior (Yu, 1999). With the intention to understand how people communicate with others, it is essential to know the mechanism behind the utterance. As Grice (1975) said, people’s exchanges of utterances are not disconnected. They were connected by some general principles, with these principles the interlocutors could recognize the purposes of conversation and carry on meaningful conversation. He proposed four categories. 政 治 大. known as ‘Cooperative Principle’. The four categories were Quantity, Quality, Relation and Manner.. ‧ 國. 學. Quantity -. 1. Make your contribution as informative as required. 2. Do not make your contribution more informative than. ‧ y. required.. 1. Do not say what you believe to be false.. io. sit. Nat. Quality -. 立. n. al. er. 2. Do not say what you lack adequate evidence.. Ch. i n U. Relation -. Be relevant.. Manner -. 1. Avoid obscurity of expression.. engchi. v. 2. Avoid ambiguity. 3. Be brief. 4. Be orderly. (Grice, 1975, pp. 45-46). In Grice’s words, people adhere to these principles to make their conversation effective. In one hand, Grice’s Cooperative Principle explains what people said; in 9.

(20) the other hand, it allows hearers to infer what people meant. According to Leech (1983), “it helps to account for the relation between sense and force”. However, he claimed Grice’s Cooperative Principle (CP) could not explain why people were often so indirect in saying what they meant, and what kind of relation lay in between sense and force when non-declarative types of sentences were used. To solve the problems of building up the bridge of the missing links with real language use, Leech proposed ‘Politeness Principle’ (PP) to complement for Grice’s Cooperative Principle (CP). In addition to regulating the textual goal and. 政 治 大 friendly relations among the interlocutors. There were 6 maxims of PP, and the 立. interpersonal goal, PP aimed to maintain the cooperative social equilibrium and. ‧ 國. 學. formulation of these maxims followed one general rule – “to minimize the expression of impolite beliefs and to maximize the expression of polite beliefs” (Leech, 1983).. ‧. The six maxims were:. y. Nat. (b) maximize benefit to other. n. al. Ch. er. io. sit. 1) Tact Maxim – (a) minimize cost to other. i n U. 2) Generosity Maxim – (a) minimize benefit to self. engchi. v. (b) maximize cost to self 3) Approbation Maxim – (a) minimize dispraise of other (b) maximize praise of other 4) Modesty Maxim – (a) minimize praise of self (b) maximize dispraise of self 5) Agreement Maxim – (a) minimize disagreement between self and other (b) maximize agreement between self and other 6) Sympathy Maxim – (a) minimize antipathy between self and other 10.

(21) (b) maximize sympathy between self and other. (Leech, 1983, p.132). Leech’s politeness maxims were important in performing speech act. According to Leech (1983), giving others advice implied processing superior knowledge. People need to beware of not violating the Modesty and Approbation Maxims and being considered impolite. Indeed the terminology of the maxims was confusing. It was criticized for unconstrained numbers of maxims (Brown & Levinson, 1987). If all. 治 政 大 pattern of language use maxims. Brown & Levinson claimed that every discernible 立. regularities in language use had specific maxims, there would be an infinite number of. did not require a maxim or principle to produce it, and they said their production. ‧ 國. 學. model on individuals’ linguistic politeness was universal.. Nat. sit. y. ‧. Brown and Levinson’s Politeness Framework. io. er. Brown and Levinson’s (1987) politeness framework was influential. The core. al. concept was the notion of face, which was mainly derived from Goffman. Goffman. n. v i n C hvalue that one andUothers assumed in a particular (1967) put it as a positive social engchi. contact. Face could be lost, and it could be saved too. In interactions, people defend their own faces and protect others’ faces. Based on Goffman’s concept of face, Brown and Levinson declared that face is a public self-image that everyone wants to claim for himself. It is comprised of two aspects: positive face and negative face. Positive face is individuals’ wants to be ‘desirable’, and negative face is individuals’ wants to be ‘unimpeded’ by others (Brown & Levinson, 1987). Basically, any rational individual would cooperate to maintain faces of the interlocutors. However, there are chances that the positive face or the negative face of the interlocutors be threatened. 11.

(22) These acts are called “face threatening acts” (FTAs). Rational individuals would try to avoid or minimize the imposition caused by FTAs. And there are repressive strategies. The core concept in the framework is positive politeness and negative politeness (Yu, 2003). So through interactions, the positive politeness is to maintain harmonious relationship of the speakers and hearers, and the negative politeness is to avoid impeding on people’s freedom of action. Politeness in Chinese Society. There was criticism that Brown & Levinson’s politeness framework may not cover the communication in Eastern culture (Gu, 1990;. 政 治 大 Mianzi is one’s achievement ascribed 立 by others in the community, the prestige or Lii-Shih, 1994; Mao, 1994). Face in Chinese society consists of mianzi and lian.. ‧ 國. 學. reputation of a person. Lian, on the other hand, is people’s respect for someone with good moral (Mao, 1994). Both of them came through the interactional process to the. ‧. public community but not to an individual. Chinese do not focus much on individual’s. Nat. sit. y. desires or needs, but rather they focus on the harmony of the community as a result of. n. al. er. io. behaviors of the group. Chinese are satisfied in the recognition or respect from the. i n U. v. community that they belong to and not so much on the wants to be unimpeded or on. Ch. engchi. their desire for freedom of action. Gu (1990) proposed Chinese limao to be equivocal with the Western politeness. There are four elements and two principles underlying limao in Chinese society. The four elements are “respectfulness, modesty, attitudinal warmth and refinement,” and the two principles are “sincerity and balance”. The politeness concept in the Chinese society is more on sincere behavior and on the reciprocal behaviors but less on the individual face work as proposed by Brown and Levinson. Lii-Shih (1994) also noticed that Chinese emphasized more on the desire of being approved. Some face threatening acts actually satisfy the hearers’ face wants 12.

(23) and are called “face-satisfying-acts” (FSAs). For Chinese, if the speaker concerns a lot about the hearer’s benefits, their giving out advice to the hearer is considered a FSA. Different from the Westerner’s idea, the less indirect and the less ambiguous the utterance is, the more polite it appears to the Chinese people (Lii-Shih, 1994). There are at least three differences observed from Brown & Levinson’s model: 1) Face in Chinese society is a public image that is interdependent with their community rather than a self-image responding their wants and desires.. 政 治 大. 2) Some FTAs in Brown & Levinson’s ideas are actually FSAs in Chinese if they. 立. are done sincerely.. ‧ 國. 學. 3) Politeness is defined to satisfy individual’s wants and not impede other’s freedom and this is also norms and values in Chinese society.. ‧. (Gu, 1990, p. 242). n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. i n U. v. Brown & Levinson’s politeness framework cannot comprehensively explain the. Ch. engchi. norms and values of Chinese society. In other words, culture difference cannot be ignored. Culture Difference Besides the discrepancies in face and politeness framework in the Western and the Eastern cultures, there are two distinct culture values: individualism and collectivism.. 13.

(24) Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose. Everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and their immediate family. Collectivism as its opposite, pertains to societies in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups… (Hofstede, 1991, p. 51) American culture is considered individualism. They emphasize individual identity over group identity. People in the individualism culture are of self-orientation,. 政 治 大. independent self, to hold out-group values. Group benefit is not the priority, and their. 立. way of speaking to in-groups and out-groups are similar (Scollon & Scollon, 1995).. ‧ 國. 學. Chinese, on the other hand, is considered collectivism. They emphasize ‘we’ over ‘I’ and group obligations are placed above individual wants and desires (Ting-Toomey,. ‧. 1994). People in collectivistic culture hold group’s values and norms as guideline for. y. Nat. io. sit. everyday doctrine. They hold in-group values and their ways of speaking to ‘in-. n. al. er. group’ and ‘out-group’ are different. Pragmatic Transfer. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Beebe, Takahashi, and Uliss-Weltz (1990) defined pragmatic transfer as a transfer of L1 sociocultural competence in performing L2 conversation. Koike (1996) proposed that learners would transfer their L1 pragmatic knowledge when performing speech acts in L2. They may produce inappropriate utterances especially when they encountered relatively difficult speech act. Thomas (1983) named such inappropriate pragmatic transfer as “pragmatic failure”. He divided the failure into two aspects: pragmalinguistic failure and sociopragmatic failure. Pragmalinguistic failure occurs when the learners use an inappropriate linguistic form to express their intention in a 14.

(25) target language context. ‘Teaching-induced errors’ might be the reason for such failure. Learners were trained to react to a certain situation with a certain response that influenced their performance in the long run (Kasper, 1982). Sociopragmatic failure results from inappropriate transfer between discrepant socio-culture norms and value systems. The breakdowns in cross-cultural communications and the phenomena of pragmatic transfer were worth exploring (Zegarac & Pennington, 2000). The Speech Act of Complaints Complaints are an expressive category of speech act. The disapproval is. 政 治 大. directed to an addressee held responsibilities for perceived offense. It is typically a. 立. conflictive act (Leech, 1983) or a face-threatening act (FTA) (Brown and Levinson,. ‧ 國. 學. 1987). In contrast, indirect complaints are expressions of dissatisfaction to an interlocutor about someone or something that is not present (Boxer, 1993). It is not so. ‧. much a FTA. It can be employed by the speaker as an attempt to establish solidarity. y. Nat. sit. with the addressee. The speaker’s chance of building relationship successfully. n. al. er. io. depends on the addressee’s willingness to participate through the give and take of. i n U. v. negotiation. Boxer (1989) classified such speech acts as ‘openers’— the speech. Ch. engchi. behavior, which functions in a manner to indicate a desire to establish commonality with the addressee. It can be a subtle indicator of shared feeling or mutual interest to initiate a topic of conversation. Previous Studies. Boxer (1989) investigated the usefulness of indirect complaints (ICs). Her research subjects included students, professors, administrative and support staff and their family members from the community of a university in Pennsylvania. She collected spontaneous conversation through observations of participants and found responses in six types: (a) zero response; (b) response 15.

(26) requesting elaboration; (c) response in the form of jokes or teasing; (d) contradiction or explanation; (e) response in the form of advice or lecture; (f) commiseration. While Boxer aimed to identify formulaic responses, she emerged no such patterns. For example, the most possible responses of commiseration, which accounted for 52 % of the corpus, were highly varied in structure and intent. The results of her study confirmed findings of earlier research: equality of status is a common characteristic of ICs. In addition to that, she found that most commiseration responses occurred among status equals with neither minimal nor maximal social distance.. 政 治 大 responses toward them, i.e. IC 立 exchanges, for a long time. Her research discussed the In fact, Boxer had conducted research on indirect complaints and people’s. ‧ 國. 學. functions of gender, social distance and social status. She claimed that there were stronger indicators of theme choice than did social status (Boxer, 1993). Men and. ‧. women used different ICs and for different purposes; in order to have satisfactory. Nat. sit. y. responses, men and women strategically would choose their addressees and topics. n. al. er. io. before they voiced their complaints. In response to ICs, men and women also used. i n U. v. different strategies to continue or terminate the conversation in their ways. Boxer’s. Ch. engchi. research provided rich baseline information from the side of American English speakers. Variables of Indirect Complaints Theme. In analysis of the content of ICs, Boxer emerged three themes with distinct focus on (1) self, (2) other, and (3) situation. The focus of an IC could be on oneself (e.g., “Oh, I’m so stupid”), on another person or persons (e.g., “He’s such an idiot!”), or on any personal and impersonal situation. The last category is divided into. 16.

(27) two subgroups: a) type A situation, a situation IC with a personal focus; b) type B situation refers to that of impersonal focus. Social status. The concept of social status is on the relative position or standing of interlocutors within the specific context of a conversational exchange. In Boxer’s research, she found that IC theme and relative social status of the interlocutors were weaker than that of IC theme and gender. It pointed to some tentative conclusions about rights and taboos. Among the status equals, commiseration and contradiction were the two most frequent responses to indirect. 政 治 大 interactions of equal status— 立 students in the universities.. complaints. To limit the scope of the research, the present study focused on the. ‧ 國. 學. Social Distance. The concept followed Wolfson’s Bulge theory (1988) with the categories of ‘friends’, ‘strangers’ and ‘intimates’. These are not discrete. ‧. categories but were points along a social distance continuum. If ‘total strangers’ was. y. Nat. io. sit. at one end of the continuum, then ‘friends’ fell near the middle, and ‘intimates’ was at. n. al. er. the opposite end from ‘strangers’. Wolfson (1988) examined the realization of. Ch. i n U. v. compliments. Her research found two extremes of social distance, minimum and. engchi. maximum, called forth similar behavior, which meant status-equal, intimates and strangers, had the most solidarity-establishing speech behavior. Boxer (1993a) countered the theory with the data collected from the speech act of indirect complaints. In her study, the Bulge was not in the middle (i.e., among friends and acquaintances), but was skewed toward to one side (strangers), or the other side (intimates). In contradistinction to compliments and invitations, her conclusion was that some rapport-inspiring speech behaviors almost occurred as frequently among interlocutors of extreme social distance as they did among friends and acquaintances. The present 17.

(28) study was focusing on the responses to indirect complaints, thus the result should be relevant to Boxer’s findings. Gender Differences. Men and women expressed differently when voicing complaints and when responding to complaints. Women normally commiserated much more than men and they tended to be more supportive to complainers. In terms of gender, Boxer claimed that a large number of ICs were between females. She attributed the outcome to reasons from data collection procedure and possibly the gender of the researcher. Therefore, in this study, a discourse completion. 政 治 大 The results should provide insight 立on the difference of responses from males and. questionnaire was designed with a consideration of the gender issue in all situations.. ‧ 國. 學. females alike.. ‧. Research Questions. The research questions of this study were:. sit. y. Nat. io. er. 1. How were the EFL students’ responses to indirect complaints different from those of native speakers of American English, and those of native Chinese. n. al. speakers in Taiwan?. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2. How did they respond when the social distances of the speakers and the hearers varied?. 18.

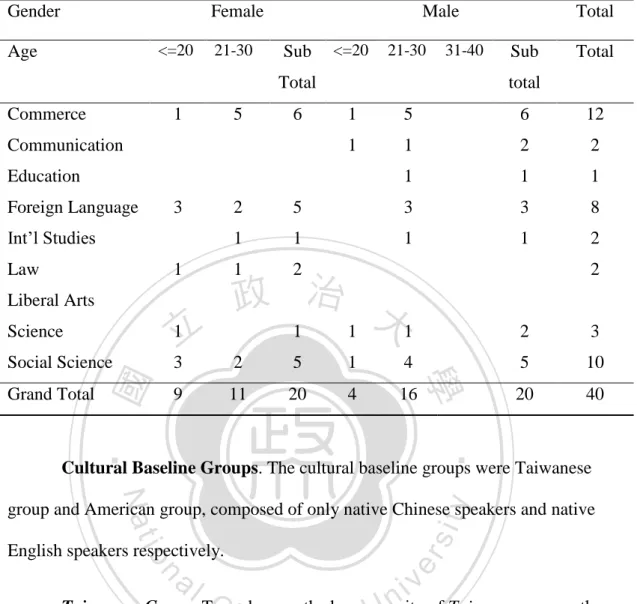

(29) CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY This chapter describes the research design of this study. The first section reveals the information of the participants. The second section explains the reason for using discourse completion task (DCT) as the instrument and discloses the controlled. 治 政 大 the methods for data procedure of data collection. The fourth section describes 立. variables and the context situations plotted in the task. The third section delineates the. analysis. The fifth section provides the reliability of the coding among the inter-raters.. ‧ 國. 學. Participants. ‧. The participants in this study were composed of three groups: 40 native. y. Nat. sit. speakers of Chinese living in Taiwan (Taiwanese), 40 English-as-a-Foreign-. n. al. er. io. Language learners (EFL) living in Taiwan, and 40 native speakers of English living. i n U. v. in the United States (Americans). In each group, the numbers of male and female. Ch. engchi. participants were kept equal. A total of 120 participants were included in the study. They were 20 male and 20 female native speakers of Chinese, 20 male and 20 female EFL learners, and 20 male and 20 female native speakers of English. Targeted EFL Group. To eliminate chances of miscommunication raised because of participants’ insufficient language proficiency (Hinkel, 1997), all participants of EFL group were English learners of intermediate to high-intermediate English proficiency level as attested by the General English Proficiency Test (GEPT). 19.

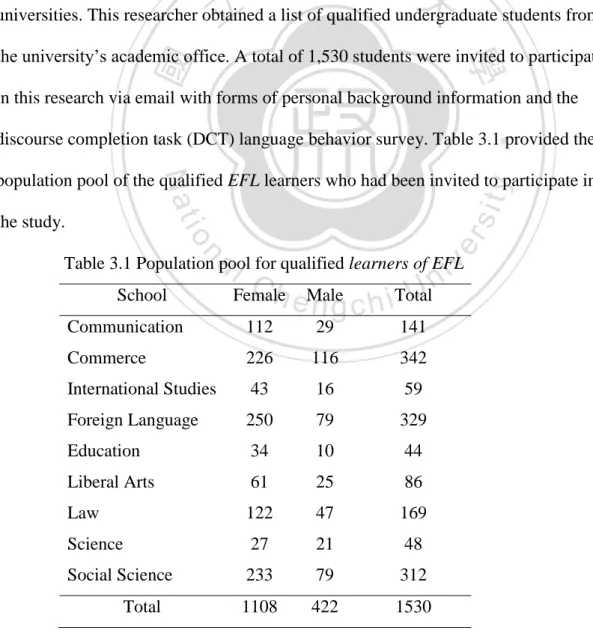

(30) conducted by Language Training and Testing Center (LTTC) in Taiwan, or by equivalent standard tests, i.e., Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC), Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) from Educational Testing Service (ETS), or International English Language Testing System (IELTS) conducted by the British Council. To ensure that the participants in this study were homogenous, none of them ever had pragmatics training, and all of them were from a common speech community, a university in Taiwan. In Taiwan, all undergraduate students are required to pass at least one English. 政 治 大 universities. This researcher obtained 立 a list of qualified undergraduate students from. standardized test in addition to their academic requirement to graduate from. ‧ 國. 學. the university’s academic office. A total of 1,530 students were invited to participate in this research via email with forms of personal background information and the. ‧. discourse completion task (DCT) language behavior survey. Table 3.1 provided the. Nat. sit er. io. the study.. y. population pool of the qualified EFL learners who had been invited to participate in. n. al. i n C U Female h eMale n g c h iTotal. v. Table 3.1 Population pool for qualified learners of EFL School Communication. 112. 29. 141. Commerce. 226. 116. 342. International Studies. 43. 16. 59. Foreign Language. 250. 79. 329. Education. 34. 10. 44. Liberal Arts. 61. 25. 86. Law. 122. 47. 169. Science. 27. 21. 48. Social Science. 233. 79. 312. 1108. 422. 1530. Total. 20.

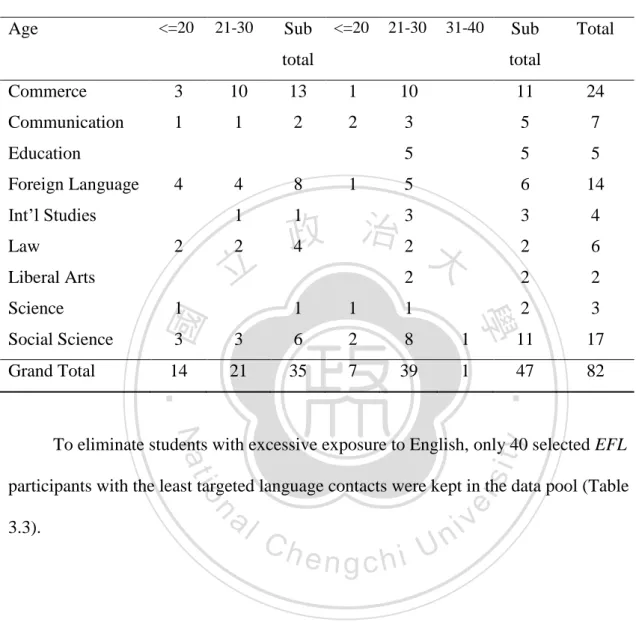

(31) To make sure that the EFL participants were of a group with least targeted language influence, a concern raised by Blum-Kulka & Olshtain (1986), all participants were required to declare their English learning experience in the personal background information sheet. The participants were asked if they had regular contacts with English speaking foreigners, and if they had ever stayed in an English speaking country. If they did have regular contacts with English speaking foreigners, participants had to declare the frequency of their contacts. If they did live in an. 治 政 were kept as the EFL subjects in those participants with minimum foreign influence 大 立 English speaking country, the length and reasons for their stay were declared. Only. this study.. ‧ 國. 學. Within the survey period, a total of 82 EFL students (35 females and 47 males). ‧. out of 1530 potential participants (5.36%) had responded to the questionnaires. Table. sit. y. Nat. 3.2 provided a summary of background of the 82 participants for this language survey.. io. er. The responders were dominated by students from School of Commerce (29.3%), then. al. were followed by students from School of Social Science (20.7%) and then by. n. v i n C hLanguages and Literature students from School of Foreign (17.1%). Majority of engchi U survey participants were in their senior year (52.4%) and junior year (24.4%). Only 30.5% (n=25) of people responded that they had frequent exposure to English speaking friends (on the daily basis, n=4; on the weekly basis, n=14, on the monthly basis, n=7). Thirty participants (36.6%) responded that they had visited an English-speaking foreign country. Majority (60%) of them only stayed there for less than 3 weeks, and 7 people declared to have stayed aboard for more than 1 year. Surprisingly that, there were more than 72% (n=59) of the responders could also speak other foreign language (mainly Japanese, 31.7% or n=26) in addition to English. 21.

(32) Table 3.2. Summary of returned questionnaires from learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) group. Gender. Female <=20. Age. 21-30. Male Sub. <=20. 21-30. Total. 31-40. Sub. total. Total. total. Commerce. 3. 10. 13. 1. 10. 11. 24. Communication. 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 5. 7. 5. 5. 5. 5. 6. 14. Education Foreign Language. 4. Int’l Studies Law. 2. 3 治 政 4 2 大. 3. 4. 2. 6. 2. 2. 2. 1. 1. 1. 2. 3. ‧ 國. 1. 1. 3. 3. 6. 2. 8. 1. 11. 17. 14. 21. 35. 7. 39. 1. 47. 82. Nat. y. ‧. Grand Total. 1. 立. 1. 學. Social Science. 8. 2. Liberal Arts Science. 4. sit. To eliminate students with excessive exposure to English, only 40 selected EFL. n. al. er. io. participants with the least targeted language contacts were kept in the data pool (Table 3.3).. Ch. engchi. 22. i n U. v.

(33) Table 3.3. Background summary of the 40 selected learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) group. Gender. Female <=20. Age. 21-30. Male Sub. <=20. 21-30. 31-40. Total Commerce. 1. 5. 6. Communication. 3. Int’l Studies Law. 1. 1. 5. 6. 12. 1. 1. 2. 2. 1. 1. 1. 3. 3. 8. 1. 1. 1. 1. 2. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 2. 5. 1. 4. 5. 10. 9. 11. 20. 4. 16. 20. 40. ‧. ‧ 國. 5. 學. Grand Total. 2. 2. 1 立. Social Science. Total. 政 治 大 1 1 1. Liberal Arts Science. Sub total. Education Foreign Language. Total. Cultural Baseline Groups. The cultural baseline groups were Taiwanese. y. Nat. sit. group and American group, composed of only native Chinese speakers and native. er. io. English speakers respectively.. al. n. v i n Cmake Taiwanese Group. To sure the homogeneity of Taiwanese group, the U hen i h gc. Chinese version of questionnaires were distributed in a class studying local land. development and management class. Among those returned questionnaires, only those from respondents who declared that they had not taken additional English classes except the mandatory freshman English and had no regular foreign contacts, were accepted data pool in the baseline Taiwanese group. American Group. All members in this group were native speakers of American English. They were either with business major or minor, and none of them were of English major. 23.

(34) To make sure that gender difference was not the bias of the research, all three data groups were composed of 20 males and 20 females, a total of 40 participants in every group. The information acquired from the native speakers of Chinese (Taiwanese) was treated as the baseline to compare and contrast with the information acquired from the EFL group, as from the viewpoint of their own culture. The information acquired from native English speakers (Americans) was served as the baseline to compare and contrast with the EFL group, from the viewpoint of the targeted foreign culture of American English speakers.. 立. High Internal Validity. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. To ensure high internal validity of this study, all participants were university students. All participants were students from two discrete schools: (1) EFL and. ‧. er. io. Instruments. sit. Nat. students from a university in Oregon, U.S.A.. y. Taiwanese groups were from a university in Taipei, Taiwan, and (2) Americans were. al. n. v i n The instruments utilized forC this a personal data sheet and a h study e n gwere chi U. written Discourse Completion Task (DCT), a questionnaire with 24 scenarios. Personal data sheet. Surveys were most commonly used to obtain a snapshot of conditions and events at a single point (Cohen & Manion, 1985), the participants in this study were first asked to provide their background information (see Appendix 1). In this study, the personal data sheet for all EFL and Taiwanese participants included their age and gender, school major, experience in learning English as a foreign language, and the frequency of their contacts with English speaking foreigners. 24.

(35) The participants were also asked if they ever had experience living in or visiting an English speaking country, if so, their reasons and length of stay in the English speaking country. For native English speakers, only age, gender and school major were asked in the personal data sheets. Discourse Completion Task (DCT) questionnaire. Although using ethnographic data collection, such as field notes, participating observation and tape/video recording, etc., could help researchers collect authentic language data, it. 政 治 大 a comparatively short amount 立 of time. The advantage of applying elicitation methods. was through elicitation method that researchers could obtain large quantity data of in. ‧ 國. 學. was that through Discourse Completion Task (DCT) questionnaire, some variables could be controlled. In addition, as all data were written down in prints, discussion of. ‧. the similarity and difference could be extracted much clearer and easier. The major. Nat. sit. y. function of the DCT was to elicit a number of data with certain controlled variables in. n. al. er. io. a comparatively short period of time.. Ch. i n U. v. The open-ended DCT questionnaire was the most frequently and effectively. engchi. used method in pragmatics research to elicit respondents’ utterances (e.g., BlumKulka, House, & Kasper, 1989; Cohen & Olshtain, 1994). In this study, the DTC provided different contextual situations for respondents to respond if they were in the said case and the questionnaire provided self-extendable columns for respondents to fill in as much information as they would like to. In cases that participants preferred not to say anything, they could choose not to give any responses and keep their responses true to their speech style.. 25.

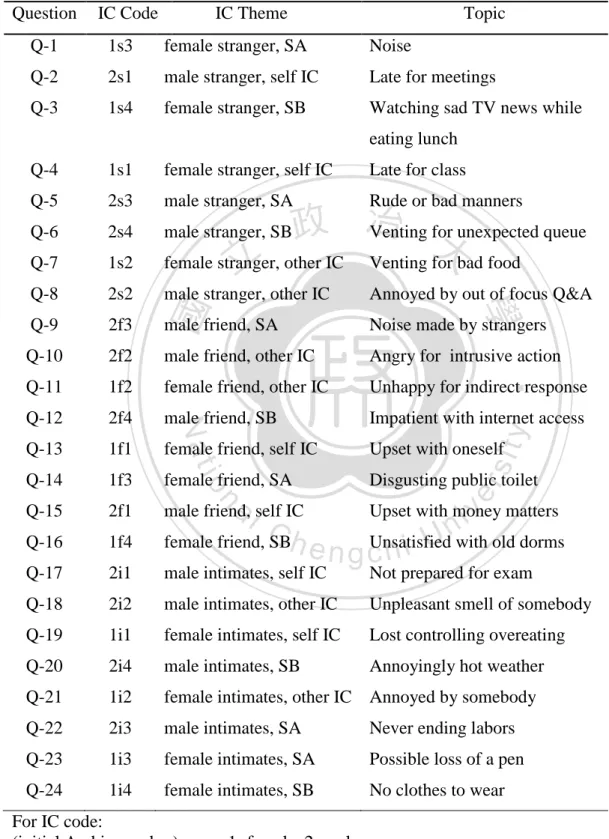

(36) In the DCT questionnaire, the scenarios were categorized by a number of episodes with a matrix of three variables: gender, social distance, and four indirect complaint (IC) themes from Boxer’s study (1993). The four themes were: (1) IC about oneself (self IC), (2) IC about others (other IC), (3) IC about situation with a personal focus (type A situation), and (4) IC about situation with impersonal focus (type B situation). The word “complain” was intentionally avoided throughout the questionnaire to evade bias in participants’ response choices (Beebe & Takahashi, 1989).. 政 治 大 discussion, it was agreed to be 立 a feasible tool to elicit a quantity of speech data in a Although validity of written DCT questionnaire had long been a topic of. ‧ 國. 學. comparatively short time. It might lack for authenticity in negotiation in one-turn imaginary DCT, yet Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) indicated that for research on cultural. ‧. comparisons of certain speech acts, stereotyped language use and character of. Nat. sit. y. responses could still be observed in a written DCT. Hence, this study adopted a. al. n. complaints.. er. io. written DCT to obtain stereotyped responses of the respondents to the indirect. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Questionnaire design. The questionnaire had two versions: one in English, one in Chinese. For the Taiwanese group, a Chinese version of the questionnaire was used to acquire the original culture baseline information; for the native speakers of English in the US and the EFL in Taiwan, an English version of survey was applied to draw out the real language use of the targeted language. The contextual situations and the wording used in the questionnaires were proof-read by native speakers of Chinese and English respectively and later on by two other bilinguals to make sure that all. 26.

(37) situations could be easily understood and no confusion could be caused among participants of different cultures. The fundamental concern of the questionnaire was that every situation was cross-culturally comparable and authentic not only for Taiwanese but for Americans alike, and no defects of this reason should be criticized. The DCT questionnaire was composed of 24 contextual situations. The situations were to reveal a systematic variation of two contextual variables-the gender of the speaker and a set social distance between the speaker and the hearer. All. 政 治 大. situational contexts were results of the interwoven of a gender and social distance. 立. with a theme of the indirect complaint (self IC, other IC, type A situation and type B. ‧ 國. 學. situation) as categorized by Boxer (1993). Gender was binary, and social distance concept followed Wolfson’s Bulge theory (1988) was triplet (strangers, friends and. ‧. intimates.) The theme was four kinds as categorized by Boxer (1993): self IC, other. y. Nat. io. sit. IC, type A situation and type B situation. These resulted in the construction of the. n. al. er. contexts. In this study, genders and themes were controlled variables to ensure that. Ch. i n U. v. there was no bias caused by them in responses. To be clear, they were not the topics of discussion in this study.. engchi. There were twenty-four contexts, being a result of 2 (gender) x 3 (social distance) x 4 (theme). In every context, the topic of the speech act in question was an issue of unpleasant situation easily detectable in school life. Every IC theme was designed to relate to a male or a female speaker of a designated social distance. In order to make the questionnaire less heavy loading for respondents, the final layout was a result of 24 reshuffled situations arranged with a first priority of 27.

(38) social distance and then with a consideration of a minimum page loads. A glance of the distribution of the questionnaire was spotlighted as Table 3-4. Table 3.4 A glance of themes and topics of the 24 scenarios in the DTC Question. IC Code. IC Theme. Topic. Q-1. 1s3. female stranger, SA. Noise. Q-2. 2s1. male stranger, self IC. Late for meetings. Q-3. 1s4. female stranger, SB. Watching sad TV news while eating lunch. Q-4. 1s1. female stranger, self IC. Late for class. Q-5. 2s3. male stranger, SA. Rude or bad manners. Q-6. 2s4. Q-7. 1s2. Q-8. 2s2. male stranger, other IC. Annoyed by out of focus Q&A. Q-9. 2f3. male friend, SA. Noise made by strangers. Q-10. 2f2. male friend, other IC. Angry for intrusive action. Q-11. 1f2. female friend, other IC. Unhappy for indirect response. Q-12. 2f4. male friend, SB. Impatient with internet access. Q-13. 1f1. female friend, self IC. Upset with oneself. Q-14. 1f3. female friend, SA. Q-15. 2f1. male friend, self IC. Upset with money matters. Q-16. 1f4. Q-17. 2i1. male intimates, self IC. Not prepared for exam. Q-18. 2i2. male intimates, other IC. Unpleasant smell of somebody. Q-19. 1i1. female intimates, self IC. Lost controlling overeating. Q-20. 2i4. male intimates, SB. Annoyingly hot weather. Q-21. 1i2. female intimates, other IC Annoyed by somebody. Q-22. 2i3. male intimates, SA. Never ending labors. Q-23. 1i3. female intimates, SA. Possible loss of a pen. Q-24. 1i4. female intimates, SB. No clothes to wear. 學. Nat. Disgusting public toilet. er. io. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 治 male stranger, SB政 Venting for unexpected queue 大bad food female stranger, other IC Venting for 立. al. n. v i n C female friend, SBh e h i U with old dorms n g cUnsatisfied. For IC code: (initial Arabic number) (middle English letter). 1=female, 2=male; s=strangers, f =friends, i =intimates; 28.

(39) (ending Arabic number). 1= self IC; 2= other IC; 3= personal focus (SA); 4= impersonal focus (SB). Categorization of the strategy used. In Boxer’s (1993) research, all responses were categorized into 6 types of strategies, and every response had only one place of fit. Discrimination of every strategy was crucial. Different from Boxer’s ethnographical approach (1993), this research used an open-ended DCT questionnaire. In a lot of cases, written responses might carry certain similarity yet with subtle differences; it was therefore important to have clear definition of the characteristics of. 政 治 大 definition was discussed 立by the inter-raters and described as follows:. every response strategy to keep classification consistent through the study. The. ‧ 國. 學. a) Zero response. Zero response is either to minimize or terminate an exchange (ibid). In this. ‧. research, the DCT questionnaire provided a blank line for participants to fill in. y. Nat. io. sit. reasons why they chose not to respond to the situation. This DCT tool. n. al. er. encouraged respondents to give reasons for their “zeroing” in response. Examples were:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1) EFL group (no response). “The girl just talked about her feeling. And sometimes sad news does ruin my appetite and mood. But I wouldn’t speak it out.” 2) Americans group (no response) “Nothing because it’s a rude comment and I don’t want to participate with it.” 3) Taiwanese group (no response) “他也把我的胃口和心情搞砸了.” 29.

(40) (Ta ie ba wo de wei kou he xin cing gao za le.) (He too ruined my appetite and mood.) b) Response requesting elaboration or question These responses took the form of questions requesting more elaboration or clarification from the speaker. These questions usually gave the addressee some chance to get information behind the utterance and in this way the addressee could gain some time to be more certain on how they should respond to speakers under those circumstances. Questions might also be used for the purpose of verifying validity of these complaints. Examples are: 1) EFL group. 立. 政 治 大. “Do you still expect another great expense in the month?”. ‧ 國. 學. 2) American group. ‧. “Hmm. Why is the weather keeping you from dressing up?” 3) Taiwanese group. y. Nat. er. io. sit. “你真的很期待這場音樂會嗎?” (Ni zhen de hen ci dai zhe chang yin yuei huei ma?). n. al. i (Are you really looking C forward to this concert?) n hengchi U. v. c) Response in the form of jokes or teasing. These responses were found when a light banter functioned to bring the interlocutors closer to each other. The respondents wanted to help the speaker step aside and to face the case with a less serious attitude. Examples of this strategy from each group were: 1) EFL group “Out bang[ing] them. When they are down and you ‘re still up, you win.”. 30.

(41) 2) American group “Better start cutting back on the beer. Haha.” 3) Taiwanese group “他可能怕你的工作太乏味, 所以找些事讓你做.” (Ta kenen pa ni de gongzuo tai fawei, suoyi zhao cie shi ran ni zuo.) (He might be worrying that your job was too boring so he helped find you something to keep busy.) d) Contradiction or explanation. 政 治 大 respondents might contradict the speakers with a truth statement of the golden 立 Sometimes, the utterance made was not accepted nor approved. The. ‧ 國. 學. rules, or accusation against the wrong attitude of the speaker, or an argument about whatever they thought differently. Examples of this strategy from each. ‧. group were:. sit. y. Nat. 1) EFL group. io. er. “But it’s not his fault. You didn’t leave anything as well.”. al. v i n C “They don’t ruin myhmood. i Uto know what’s going on in the e n gI feel c ha need n. 2) American group. world. ” 3) Taiwanese group “抱歉, 但不是所有的人都這樣.” (Baocian, dan bushi suoyou de ren dou zhe yang.) (I am sorry but not everyone is like that.) e) Responses in the form of advice or lecture These respondents wanted to help out by giving some advice to solve the problem. They might take the forms of giving advice, suggestions, lectures or 31.

(42) morals. As often was the case that the respondents voluntarily offered themselves or anything that they thought could be of help. Examples of this strategy from each group were: 1) EFL group “You have to talk to her much more directly.” 2) American group “If you don’t want to disturb the class, stop talking.” 3) Taiwanese group “就直接跟他們說他們很吵就好了.”. 政 治 大 (Jiou zhijie gen tamen shuo tamen hen chao jiou hao le.) 立. ‧ 國. 學. (Just tell them directly that they are making too much noise.) f) Commiseration. ‧. These responses were to show sympathy, understanding, agreement or. sit. y. Nat. reassurance to the speakers for their meaningful deeds. To differentiate. io. er. strategy of commiseration from strategy of advice, responses that showed. al. v i n C h function like suggestion, group; and responses carried extra voluntarily help engchi U n. understanding and assurance to make speakers feel better were kept in this. offering, moral lessons, etc., were categorized under strategy in form of advice or lectures. Examples of this strategy from each group were: 1) EFL group “We won’t come this restroom again.” 2) American group “I’m sorry but these things happen.” 3) Taiwanese group “沒關係. 反正剛剛也沒做什麼.” 32.

(43) (Mei guanxi. fanzheng gang gang yie mei zuo shemo.) (Never mind. We didn’t do much just now.) Procedures There were five main stages in this study: questionnaire design, pilot testing, data collection, coding, and data analysis. First, the questionnaire design was discussed in previous section. The second step was to pilot the questionnaire with small population and to make sure those questions could be answered as per the researcher’s wish. Third, the targeted participants completed the questionnaires.. 政 治 大 encoded. Finally, the collected data was analyzed through frequency counts and chi立 Fourth, the responses were reviewed and screened. Then valid responses were. ‧ 國. 學. square for further interpretation.. Data Collection and Coding Scheme. All valid questionnaires were encoded. ‧. according to the six types of strategy categorized by Boxer (1993) as described. The. sit. y. Nat. six types of responses were: (a) zero response; (b) response requesting elaboration; (c). io. er. response in the form of jokes or teasing; (d) contradiction or explanation; (e) response. al. v i n C h category, in otherUwords, all responses were would be assigned to one specific engchi n. in form of advice or lectures; (f) commiseration. Each response from the participants. mutually exclusive in one category. Furthermore, 20% of the data was randomly selected from each group and coded by a second rater to get the inter-rater agreement coefficients up to 85% at the least (Cohen, 1960). For the strategy categories, the inter-rater agreement coefficients in this research were 93%, 91% and 92 % respectively for American group, EFL group, and Taiwanese group.. 33.

(44) Data analysis. There were two phases in the quantitative analysis. Phase one—quantitative analysis. A statistical analysis software (Sigma Plot) was used to analyze the data obtained after the coding of the responses in the DCT. The results were also manually calculated and validated using formulas in Excel spreadsheet for error proof. Frequencies were counted and compared. Since the data collected in this study were nominal, a nonparametric chi-square was calculated to see if there was significant difference among the three groups. Phase two—qualitative analysis. Based on the actual wording used in the. 政 治 大. responses, qualitative analyses were conducted to see if there were similarity and. 立. difference in the three groups when they responded to indirect complaints and. ‧ 國. 學. toward people of different social distances. Sub-categories were established by the. a) Zero response. Nat. sit. y. ‧. contents and characteristics of the strategy in responses.. io. er. For those zero responses, participants explained the reasons why they chose to be silent in the space provided. The researcher reviewed the responses by the actual. al. n. v i n C h them into 6 sub-groups wording used and further sub-categorized under the category engchi U. “zero response”:. (1) Sub-group 1—agreement: the respondents generally agreed with what was said. They might feel that there was no need to say anything. Things had been or would be taken care of in due course or the speakers were excused and nothing should be said, or that what happened was common and it might happen to anyone so there was no need to say further. Or sometimes the respondents wanted to keep their response open for various situations, in their words, “it depends”; 34.

(45) extremes could be what they said, “No comments”. Or in some cases, the addressees just helped but not giving a word. Examples of reasons for agreement were: EFL group-“It will be quiet when the movie starts.” American group-“I wouldn't want to say anything as she is trying to minimize the disturbance, etc.” Taiwanese group-“他應該不是故意的,讓會議繼續. (ta yinggai bushi guyi de, rang hweiyi jixu.)” (He shouldn’t have. 政 治 大. done that on purpose. Let the meeting continue.). 立. ‧ 國. 學. (2) Sub-group 2—disagreement: the respondent disagreed with what was said. Sometimes speakers were just venting or complaining to the air,. ‧. or they were rude and impolite that the hearers didn’t want to respond. sit. y. Nat. in those circumstances and show their disagreement. The respondents. io. er. didn’t want to make a fuss of the situation and wouldn’t want to make. al. v i n C h don't know her. EFL group-“I e n g c h i U Maybe she is just venting.”. n. the speakers feel worse. Examples were:. American group-“I don't agree with her.” Taiwanese group-“她可以不要看. (ta keyi buyiau kan.)” (She doesn’t have to watch [the news].). (3) Sub-group 3—stay trouble-free: the respondents might want to avoid contacts. The speakers might be too provocative, and the hearers wouldn’t want to respond to get into troubles. The speakers might be in. 35.

(46) a bad mood talking to him/her might result in fights or troubles, so the respondents didn’t want to respond to the speakers. Examples were: EFL group-“The class has already begun. Any voice could interrupt the class.” American group-“I wouldn't want to further disturb the class.” Taiwanese group-“反駁會引起紛爭,那就算了吧. (fanbuo hwei yinqi fenzheng, na jiou suanle ba.)” (Contradiction might result in fights. Forget it.). 政 治 大 (4) Sub-group 4—awkwardness: the situation was awkward, embarrassing 立. ‧ 國. 學. for the respondents to give out any response. It might probably because the topics were personal, emotional or awkward; responding to the. ‧. speakers was weird considering the close friendship between the two. sit. y. Nat. parties. Examples were:. io. er. EFL group-“It is weird talking something in this time.”. al. v i n Ch U wuo renshi.)” (I know Taiwanese group-“主廚我認識. e n g c h i(zhuchu n. American group-“I would be embarrassed.”. the chef.). (5) Sub-group 5—not-my-case: “Not me.” “Not my case.” These things were not likely to happen to the respondents. The respondents might have no clues on how to respond toward it nor did they know how to help the speakers. Examples were: EFL group-“It's not my business.” American group-“I just can't think of a response to that” 36.

(47) Taiwanese group-“不知道該說什麼. (bu zhedao gai shuo shemo.)” (Don’t know what to say.). (6) Sub-group 6—busy, too-much-work, the topic was too common to discuss. The respondents were busy and they didn’t want to get involved with unnecessary conversations. They might not know the person too well. In other words, they were not familiar enough to respond to them. Examples were:. 政 治 大 American group-“[I] wouldn't want to start a conversation.” 立. EFL group-“If I don't know her, [then] I won't say anything.”. ‧ 國. 學. Taiwanese group-“我正準備去另一間電腦教室. (wuo zhen zhuenbei qu ling yijan diannao jiaoshi.)” (I am on my way to. ‧. another computer lab.). sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. b) Responses requesting elaboration or questions. i n U. v. Questions were cast to clarify things unclear to the respondents. They might be. Ch. engchi. questions checking if the speakers had tried something, or if the speakers were in need of any help? The response in this category was small in number and questions were obvious but different in directions so no subgrouping was established.. c) Jokes or teasing (1) For jokes or teasing response, four subgroups were established as based on the target been teased,: Teasing on the hearers themselves, examples were: “在我手上 (zai wuo shoushang.)” (It’s in my hand), “I. 37.

(48) know who took it! I did. So sit down and relax”, “hopefully my fat could be dried up as well”.. (2) Teasing on the speaker, the irritated person, examples were: “穿少一 點就 OK 了!!! (chuanshaoyidian jiou OK le.) ” (It’s ok to wear less.), “Are you falling in love?”, “You are mean”.. 政 治 大 speaker, the person initiated the irritation, examples were: “他是不知 立. (3) Teasing on someone not in the talks, who was the one irritating the. ‧ 國. 學. 道主題是什麼而已 (ta shi buzhidao zhuti shi shemo er yi)” (He just don’t know the topics are.), “When it costs more to keep the chamber. ‧. pots than to replace them”, “Maybe it’s indeed too hard for him to. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. figure it out”.. i n U. v. (4) Teasing on non-human materials or the situation happened, examples. Ch. engchi. were: “住宿費跟外頭租屋費一樣時 (zhusufei gen wuai tou zuwufei yiyang shi.)” (When the dorm costs as much as you rent outside), “Welcome to NCCU”, “It makes life more interesting”.. d) Contradiction and explanation For responses with contradiction or explanation, three subgroups were formed:. 38.

(49) (1) To contradict with a statement of truth, some golden rules were stated. Examples were: “That’s not true for everyone. Some people will always be inconsiderate”.. (2) Expression of disagreement on certain wrong doing or attitude of the speaker. Examples were: “You weren’t sitting at the desk. It’s an honest mistake”.. (3) Explanation on what the hearer thought not proper about the speaker, a. 治 政 different idea. Examples were: “It’s 大 hot. But the sun is definitely better 立 than a cold dark winter”.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. e) Advice, suggestion, lectures or morals. sit. y. Nat. There were responses from respondents who just wanted to help the speakers. io. er. out of the unhappy situations. These responses were categorized under the name of advice, lecture or moral lessons. Among these responses, a lot of them were advice. n. al. i n yet with different degrees ofC imposition. There were: hengchi U. v. 1) mild advice, like “you can …”,. “你可以跟她說你很忙,改天聊啊!(ni keyi gen ta shuo ni han mang, gaitian liao a!)” (You can tell her that you are busy and maybe chat some other time.). 2) strong advice sounding more direct as “you should”, “you have to”, “那你應該試著跟她談!(na ni yinggai shizhe gen ta tan!)” (You should try to talk to her.) 39.

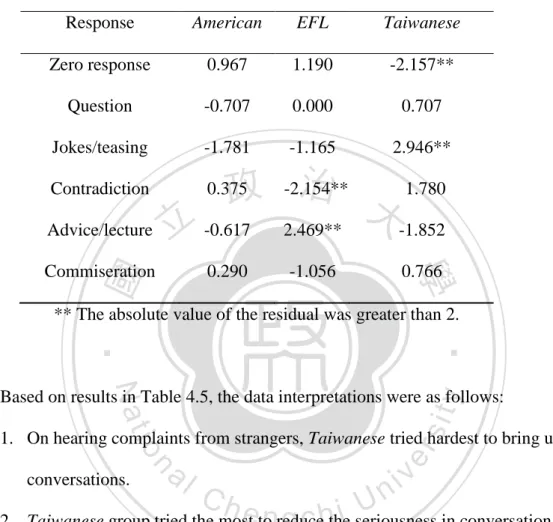

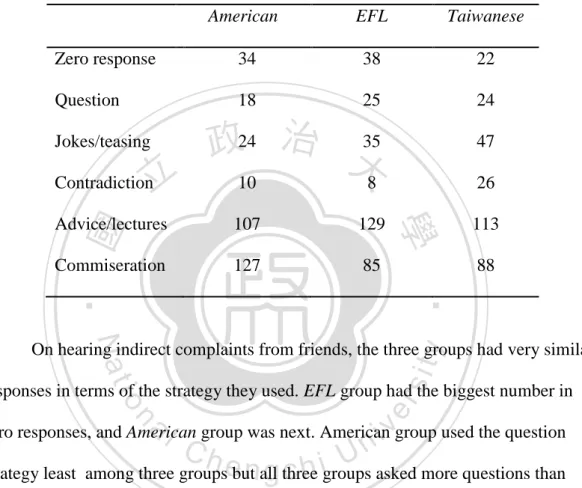

數據

相關文件

Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal experiences and opinions on familiar topics with elaboration. Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal

printing, engraved roller 刻花輥筒印花 printing, flatbed screen 平板絲網印花 printing, heat transfer 熱轉移印花. printing, ink-jet

Teachers may consider the school’s aims and conditions or even the language environment to select the most appropriate approach according to students’ need and ability; or develop

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

Writing texts to convey simple information, ideas, personal experiences and opinions on familiar topics with some elaboration. Writing texts to convey information, ideas,

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

We explicitly saw the dimensional reason for the occurrence of the magnetic catalysis on the basis of the scaling argument. However, the precise form of gap depends

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..