The impacts of benefit plans on employee

turnover: a firm-level analysis approach

on Taiwanese manufacturing industry

Chun-Hsien Lee, Mu-Lan Hsu and Nai-Hwa Lien

Abstract Employee turnover is a serious problem and the question of how to retain highly talented and valued people is very important. Previous employee turnover studies were mostly focused on the individual level but rarely from the standpoint of the business or firm. This study examines the impacts of four kinds of benefit plans on firm-level employee turnover issues, namely, retirement fund, pension, severance pay and fringe benefit. The present study uses the Census Bureau Employment Movement Survey of the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics in Taiwan. The two models used to examine the overall manufacturing industry were: (1) the inducement model which tests the ‘with or without’ effect; and (2) the investment model which tests the ‘the more the better’ effect. Results reveal that, with respect to the firm’s employee turnover rate, retirement fund and fringe benefits are negative while severance plans are significantly positive. These results are consistent with the transaction costs theory that total expenditure on these plans to retain employees (bureaucratic cost) is less than the market arrangements (transaction cost). In addition, the impact of pension plans is negative in respect of employee turnover in larger or more highly educated firms, but positive in firms with a lower educational level. Moreover, the firm size is negative while the firm’s average employees’ educational level is positive with respect to the workforce leaving their jobs. These results are consistent with the perspective of resource-based theory and human capital theory. Incidentally, this study also reveals insignificant differences between the ‘with or without’ effect and the ‘the more the better’ effect existing as a sub-group industry rather than across the entire industry.

Keywords Employee turnover; benefit plans; pension; severance pay; fringe benefit.

Introduction

Employee turnover refers to the movement of employees out of an organization (Bohlander et al., 2001). Mobley (1982) defines employee turnover as the common voluntary cessation of membership in an organization by an individual who receives monetary compensation for participating in that organization. This definition primarily focuses on separation from an organization rather than on accession, transfer, or other

The International Journal of Human Resource Management ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2006 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals DOI: 10.1080/09585190601000154

Chun-Hsien Lee (corresponding author), Assistant Professor, Graduate and Institute of Human Resource and Knowledge Management, National Kaohsiung Normal University, 116, Ho-Ping 1st Rd, Lingya 802, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (tel: þ 886 7717 1930 ext. 2404; e-mail: cslee@nknucc.nknu.edu.tw); Mu-Lan Hsu, Dean, College of Management, Professor, Department of Business Administration, Shih Hsin University, Taiwan (tel: þ886 2 2236 8225 ext. 3301, 3302; fax: þ 886 2 2236 7151; e-mail: mulan@cc.shu.edu.tw); Nai-Hwa Lien, Assistant Professor, Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University, Taiwan (tel: þ 886 2 2363 0231 ext. 3743; e-mail: lien@mba.ntu.edu.tw).

internal movements within an organization. Researchers and practitioners alike are interested in this issue. Managers are primarily concerned because of the personnel costs incurred when employees voluntarily quit. Scholars are interested in turnover because it is an important criterion and reflects a critical motivated behaviour, one that may provide insight into volitional behaviour (Barrick and Zimmerman, 2005). The study of employee turnover by management often remains one of their core tasks since the management wants to reduce it or maintain it at an acceptable level (Fitz-enz and Davison, 2001).

Employee turnover contributes to the potential benefits and disadvantages for organizations. The positive ramifications include displacement of poor performance, infusion of new knowledge and technology, reducing labour costs when facing stiffer competition, maintaining ties with exiting employees and providing new business ventures, or enhancing promotional opportunities for the remaining staff. The negative effects cover economic costs, productivity losses, impaired service quality, lost business opportunities, increased administrative burden and loss of morale among the remaining staff (Griffeth and Hom, 1994). However, employee turnover costs are not only monetary but the company may have also lost the ‘knowledge’ possessed by the departing employee (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2001). Facing competitive challenges, knowledge is not only at the core of competence but is also a value-created mechanism. The knowledge that is embodied in human beings (as human capital) and in technology has always been central to companies’ visibility and economic development. Harnessing new technologies and innovation will be the source of long-term employment and productivity growth for companies and countries in a knowledge-based economy (Noe et al., 2002). Since knowledge resides in people, a critical issue for companies operating in the new economy is retaining their valued employees. Human capital theory suggests that because the knowledge, skills and abilities that people bring to organizations have enormous economic value to the organization, they need to be managed in the same strategic manner that other economic assets (e.g. land, financial capital) are managed. Additionally, resource-based theory (Barney, 1991) proposes that those resources which are rare, inimitable and non-substitutable provide sources of sustainable competitive advantage for the organization. A firm’s ‘human resource deployments’ have the potential to meet these conditions and thus provide the firm with an advantage in terms of its human, social and intellectual capital in order to gain a competitive advantage (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

That is, employee turnover is viewed as having critical negative impacts not only on the development of the employee’s technical competence and skills levels but also on the morale of the remaining employees and the image of the company (The Institute of Singapore Labour Studies, 2001). Although Glebbeek and Bax (2004) tested the hypothesis that employee turnover and firm performance have an inverted U-shaped relationship, they revealed a curvilinear relationship; high turnover was harmful, but the inverted U-shape was not observed with certainty. However, most studies point towards a negative relationship between employee turnover rate and firm performance (e.g. Ostroff, 1992; Huselid, 1995; Allgood and Farrell, 2000; McElory et al., 2001; Lausten, 2002).

Since the primary employee turnover cost is the cost flow of intellectual capital, which resides in people, the question of how to retain human resources has become one of the leading challenges for organizations to overcome. Many studies focus on investigating the personnel antecedents from a psychological perspective; others explore the management or incentive practices effects on employee turnover. The current economic climate highlights the importance of benefit packages offered to employees. Benefits are designed to safeguard employees and their families against problems due to sickness, accidents or retirements. Firms that offer attractive benefit packages tend to retain talented

employees and reduce employee turnover. Employee benefits constitute an indirect form of compensation intended to improve the quality of the work and the personal lives of the employees (Milkovich et al., 2005). It is clear that benefits are no longer a ‘fringe’ but rather an integral part of compensation package. Additionally, since most benefits (almost 80 per cent) are voluntarily provided by employers, benefits become both a significant cost and an employment advantage to employers, while also providing the needed psychological and physical assistance to the employee (Bohlander et al., 2001). Employees rely on benefits such as healthcare, insurance, fringe benefits and pensions for economic security and personal well-being, while employers are believed to use benefits as a means of achieving important objectives, such as attraction, retention and the consequent organizational effectiveness.

Notably, a search in October 2005 for articles published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals with ‘employee turnover’ as the subject heading found 1,140 studies from the PsycINFO database and 4,491 articles from the ABI/INFORM Complete (ProQuest) database. However, most employee turnover studies have been conducted in organizational sciences which focus on the topic of individual-level predictors and examine the cognitive processes that precede an employee’s decision to leave a firm (Shaw et al., 1998). Little research has examined the impact of human resource management practices on employee turnover. Employee turnover is clearly consequential for organizations. It has been suggested that some solutions to problematic turnovers may be linked to the manipulation of organizationally controlled variables. Thus, an argument can be made for the importance of examining employee turnover as a firm-level variable (Bennett et al., 1993).

Hence, this study investigates the effect of benefit plans on employee turnover from the firm-level perspective. The studies using this approach are also rare in human resource management research typology (Wright and Boswell, 2002). This study attempts to explore what types of benefit plans influence the employee turnover rate and whether the firm size, location and firm employees’ educational attainment moderate the effects of those benefit plans.

Theoretical background and literature review Employee turnover research

The turnover criterion includes various dimensions with the most obvious being whether it is voluntary or involuntary. However, this classification may fail to fully consider the complexity of reasons behind the turnover decision. Additionally, there are many problems with turnover measurement (Campion, 1991) and lack of agreement on the definition of ‘voluntary’ because it depends on who you ask as to why the employee left his or her job. Central to this study is voluntary employee turnover; hence, we adopt the Maertz and Campion (1998) definition: ‘voluntary turnover is where management agrees that the employee had the physical opportunity to continue employment with the company, at the time of termination’. Voluntariness conveys that there was no impediment to continued employment from physical disability or from corporation management, such as non-mandatory retirement, quitting for family resettlement, or quitting for a self-perceived more desirable job. That is, employee turnover implies individual choice, even though the employee may know to stay is extremely costly.

Most studies are focused on individual-level approach and can be broadly divided into two main streams: behavioural intentions and job search mechanisms (Steel, 2002). Studies on behavioural intentions are most notably focused on the intention to quit or stay, primarily investigating the relationships among predictors and personnel characteristics,

such as employees’ satisfaction with their jobs, organizational commitment, job search, comparison of alternatives, withdrawal cognitions and quit intentions. Moreover, the moderators of employee turnover include work environment, job content, stress, work group cohesion, autonomy, leadership, distributive justice and promotional chances. Some demographic attributes, such as tenure, number of children, age, educational level and gender, are also significant predictors of turnovers (Griffeth et al., 2000). Another approach is the job search mechanisms, explaining the individual job separation decision-making process. Lee and Mitchell (1994) and Lee et al. (1996) proposed the job unfolding model, from the job-searching and decision-making perception. Additionally, Mitchell et al. (2001) demonstrated the job embeddedness model, which illustrates employees who are embedded in their jobs by contextual ties. The employee turnover intentions depend on the embedded factors and the ease with which ties can be broken. However, relatively few studies of this literature have examined the determinants and consequences of employee turnover at the firm level (Shaw et al., 1998; Wright and Boswell, 2002). In relation to all numerous employee turnover studies, contemporary research from the business or firm level is scarce.

Regarding the employee turnover firm-level studies, researchers explored a set of interrelated human resource policies designed to enhance work performance and decrease leaving rates. It was found that firms should provide a series of promotional steps that continually expand the employees’ firm-specific skill sets and reward them with higher pay. In exchange, employers gain a loyal and stable workforce with high levels of firm-specific skills, amortizing the quasi-fixed cost of employment over many years of employee tenure (Batt et al., 2002). Arthur (1994) was the first to examine the effects of human resource practices on firm performance, and proposed two distinct empirical approaches: control and commitment systems. He revealed that employee turnover would be significantly higher with control systems than with commitment systems. Through the accommodation of commitment-enhancing human resource management (HRM) systems, employees maximize their own interests and their own financial and psychological outcomes, and remain with organizations when overall self-interest is maximized by staying. Briefly, the firm-level studies are classified into exploring the impacts of macro human resource practice grounding or micro human resource practices implementation on employee outcomes (turnover and productivity) and corporate financial performance (Wright and Boswell, 2002). Macro approach results revealed that high performance work practices (Huselid, 1995), and high involvement in work practices (Guthrie, 2001) induce economically and statistically significant effects on both the employee and organization (Huselid, 1995). Additionally, Youndt et al. (1996) implied the control perspective and proposed three HRM patterns corresponding with two dimensions, knowledge of cause – effect relations and standards of desirability. Lepak and Snell (1999), furthermore, based on their research on the human capital theory resource-based view of the firm and also transaction cost economics to ground the commitment perspective human resource architecture of the four employment modes and derive relevant relationship-management practices. Some other studies also examine and to some extent modify their approaches in order to make their findings more valid (e.g. Lepak et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2003; Lepak and Snell, 2002; Kulkarni and Ramamoorthy, 2005). Results show that the strategic value and uniqueness of human capital differs across these four employment modes; additionally, each employment mode is associated with a particular type of HR configuration; adopting fit practices promotes both employee and organizational performance. Hence, both the control perspective and commitment perspective accentuate the contingency fit to enhance performance.

Results of micro firm-level research, employee skills, organizational structures, average pay, benefit plans, health assurance practices, benefits as a percentage of payroll, job ladder length, percentage pay growth, importance of seniority for core job filling, high skills emphasis, employee participation in decision making and in teams, incentives such as high relative pay and employee security are consistently negative and significantly related to voluntary workforce turnover (Huselid, 1995; Shaw et al., 1998; Batt, 2002; Fairris, 2004); however, incentive compensation systems may actually encourage employees with a poor performance to leave a firm (Huseld, 1995). Whereas electronic monitoring, working time (Shaw et al., 1998), below-average industry or area wage, pension inducement and the skills of the core workforce are very transferable to firms in other industries, internal promotion was very or extremely important and also (Fairris, 2004) positively related to employee turnover. Notably, Chang and Cheng (2002) investigated the links between HRM practices and the firm performance of Taiwan’s high-tech firms located in Hsinchu Science-based Park (HSIP). They found that the more comprehensive a firm’s benefits are, the more significant the effects are on firm performance; in addition, the benefit plans significantly decreased employee turnover whether firm’s cost strategy or differentiation strategy was utilized. Apart from the financial payments, HSIP firms also provide employees with services benefits such as child-care facilities, dormitories and medical care. Benefits plans are also significant and negative in relation to employee turnover. This finding would support the contention that systematic efforts to set up a well-developed benefits package are especially important to high-tech firms trying to employ and retain a highly qualified workforce.

Benefit plans

Benefit plans refer to that part of the total compensation package (other than the pay for time spent on work) that is provided to the employee in whole or in part by payments from the employer (Milkovich et al., 2005); in addition, benefits are group membership rewards that provide security for employees and their family members. Benefit plans are ordinarily conceptualized in two ways. The narrow definitions of benefit plans include employer-provided retirement, health, welfare and fringe benefits. Moreover, some social insurance programmes should also be included to satisfy the broader definition of employee benefits. In particular, benefit satisfaction includes not only the types and levels of specific benefits received, but also satisfaction with the way the benefit system operates, especially from the perspective of international justice (Williams et al., 2002). Employee benefits protect employees from risks that could jeopardize their health and financial security. They may also provide services or facilities that many employees find valuable. In addition, benefit plans that are designed to increase in value over time encourage employees to remain with their employer (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2001), consequently, they have a moderating effect on firm productivity, irrespective of industry or firm size. Moreover, the effect is greater in small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) than in large firms (Tsai and Wang, 2005).

Briefly, the impacts of benefit packages on organizational effectiveness occur through screening (helping the firm attract and retain more able employees) and motivation (helping to elicit superior performance) (Baron and Kreps, 1999). Benefit plans can enhance satisfaction, sustain loyalty, retain frontline workers, improve service quality and discourage employees from leaving (Griffeth and Hom, 1994; Dreher et al., 1988; Bennett et al., 1993; Dawn, 1993); these effects are more apparent in high-tech firms (Gionfriddo and Dhingra, 1999). In particular, those firms where benefits were a higher percentage of total labour costs, and those firms whose benefit packages were described

to be of higher quality experienced less attrition (Bennett et al., 1993). Additionally, retirement fund plans, medical plan offers and the benefits of choice plans promote the effect of benefit plans on decreasing employee turnover (Dawn, 1993). Pension coverage was associated with a greater reduction in worker turnover in large firms than in small firms; however, controlling worker characteristics can virtually remove any association between firm size and labour turnover for workers not covered by any pension plans (Even and Macpherson, 1996). Similarly, Miller et al. (2001) examined Maquiladora (i.e. American-owned plants in Mexico) and found that attendance and seniority rewards did not positively predict turnover, but fringe benefits explained the unique turnover variance and savings plan contributions negatively predicted turnover.

Transaction cost theory

Transaction cost theory demonstrates how the combination of bounded rationality and opportunism creates the prospect that costly negotiating and monitoring costs may accompany exchanges conducted within the market. The rationale for the existence of any management practice is its efficiency compared to the set of available alternatives. In other words, the transaction cost explanation is one of comparative efficiency. According to transaction cost theory applied to human resource management, the analytical framework has two sides: first, the administrative mechanism whose efficiency is the issue and second, the dimensions of interactions that determine how efficiently a particular administrative mechanism performs. If a transaction is sufficiently continuous or frequently generates concern for the efficient uses of resources involved, two dimensions determine the best mode of governing the transaction: (1) the uncertainty associated with executing the transaction; and (2) the uniqueness or specificity of the assets associated with the goods or service transacted (Walker and Weber, 1984). In other words, the cost of performing the benefit plans (cost of internal government) and the benefit from the employee staying when performing these plans are the main issues to be concerned with. Otherwise, the cost of arranging with the external labour market and the cost of the employee leaving without performing benefit plans are considered. Finally, the values of the present and the future also need to be included, for example the current cost may induce future benefits or reduce future costs.

From the transaction cost theory perspective, the adoption of a strategic approach to HRM can minimize the costs involved in controlling internal organizational exchanges. These costs stem from the need to establish, monitor and enforce a ‘myriad of implicit contracts between employers and employees’ designed to protect the organization from the members’ self-interest or opportunism. In theory, the adoption of a strategic approach to HRM should allow a firm to adopt more streamlined governance systems when the nature of the work process is such that employee loyalty and/or firm-specific knowledge, skills and abilities are highly valued (Bamberger and Meshoulam, 2000). In an effort to identify the most efficient form of organizing employment, firms either rely upon the market to govern a transaction, or they govern this process internally (Lepak and Snell, 1999).

Pension, pay for retirement fund plans and employee turnover

Transaction cost theory highlights the firms’ focus on securing the most efficient form of organizing employment. Firm-specific investments incur costs of monitoring and securing compliance, so that firms strive to minimize the ex ante and the ex post costs associated with managing employment (Lepak and Snell, 2002). A firm’s decision to invest in benefit plans to retain valued employees will lead to a reduction in transaction

costs. Otherwise, some benefit plans are shared responsibilities between employer and employee, such as pension plans. Thus, employees also consider the transaction costs and benefits while deliberating over whether to leave a firm or not.

Pension plans are tied to job investment, an essential basis for commitment and retention. Research on commitment similarly conceives of compliance or calculative commitment as identification based on extrinsic inducements. Commitment leads the employees to become bound to a firm because they have personal investment in it and fear losing those investments (Mathieu and Zajac, 1990). Employee turnover studies found that the perceived costs of quitting reduced the number of resignations.

There are two types of pension plans: defined contribution and defined benefit plans. Defined contribution plans are the most straightforward type. For each pay period, the firm makes a contribution to the employee’s pension account, which is owned by the worker. The money in the account is invested in interest-bearing securities of some sort, sometimes chosen by the worker and sometimes dictated by the employer or some other organization, like a union. With a defined benefit plan, the worker is promised a specific benefit, irrespective of the amount that is in the fund. The employer makes up all shortfalls to the fund using some formula (Milkovich et al., 2005). Pay for the retirement fund is the indicator representing pension plans in this study; in addition, the practical pension disbursement is also included in this study. The retirement fund implies future security; however, the practical pension disbursement indicates a firm’s ability to pay which in turn will strengthen the organization’s commitment and trust.

Firms adopt retirement funds and pension disbursements (internal management costs, bureaucratic costs) to reduce the costs of employee turnover (market arrangement costs, transaction costs). On the other hand, for the employee, the amount of pension increases with tenure; thus, retirement fund and pension disbursement increase work stability and career security; that is, they reduce employee turnover. Moreover, the practical pension disbursement also represents the firm’s ability to pay; thus, it is a firm’s favourable financial signal to strengthen employee retention. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a: The incidence of retirement fund is negatively related to the employee turnover rate.

Hypothesis 1b: The average amount contributed to the retirement account by the employer is negative in relation to employee turnover rate. Hypothesis 2a: The incidence of pension performed is negatively related to the

employee turnover rate.

Hypothesis 2b: The average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account is negative in relation to employee turnover rate.

Severance plans and employee turnover

Severance pay is often granted to employees upon termination of employment. It is a matter of agreement between an employer and an employee (or the employee’s representative) and is usually based on the length of employment for which an employee is eligible upon termination. Severance pay is not required by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) but it is regulated by Taiwan’s Labor Law. The latest information from the 2002 US Severance and Strategy Survey from Mercer Human Resource Consulting (www.imercer.com) reveals trends in severance offerings. The amount of the severance package depends largely on the employee’s rank and the organization’s size; larger employers tend to have greater severance benefits than smaller companies.

Kodrzycki (1998) examined the effect of severance pay on job search and found that severance packages tend to considerably prolong joblessness. Workers receiving severance pay were estimated to remain jobless between 16 and 61 per cent longer than workers who received no severance pay. In addition, severance benefits caused the displaced workers to delay or otherwise reduce the intensity of their job search. Unlike unemployment insurance, severance arrangements are voluntary on the part of employers and fully funded by them; thus, severance packages play a positive role in providing added resources for displaced workers.

The firm adopts severance pay to terminate employment relations at its own initiative. This is termed functional employee turnover. In other words, according to the transaction cost theory, if the bureaucratic costs of internal hierarchical arrangements are higher than the transaction costs of external marker arrangements, severance pay is given. Otherwise, the current cost of severance implementation also reduces the future cost if the employment relation is not terminated (i.e. the purpose of severance pay is to separate the employee). Moreover, from the employee’s perspective, higher severance pay is an incentive for job separation or job transfer. Severance pay being given is perhaps also a warning indicating a future business crisis; thus, it also influences employee separation. Hence, the related hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3a: The incidence of severance performed is positively related to the employee turnover rate.

Hypothesis 3b: The average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account is positive in relation to employee turnover rate.

Fringe benefit plans and employee turnover

Fringe benefit plans are voluntary offerings by the firm. Expenditures on fringe benefits contribute to employee retention through increasing job satisfaction. Most of these practices are service offerings, such as employee assistance programmes (EAPs), counselling services, child and elder care, food services, travel, on-site health services, etc. More fringe benefit plans induce more job satisfaction and lead to lower rates of employee turnover. However, the costs of fringe benefit plans are the securing employee costs (bureaucratic cost). The purpose of adopting fringe benefit plans is to retain the employee in order to reduce the market arrangement costs (transaction costs). In addition, only members of the firm share the fringe benefit plans; thus, the employee would balance the utility of fringe benefits or job separation when deciding to leave or to stay. More fringe benefit plans increase the utility of staying and leaving costs; thus, decreasing employee turnover. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 4a: The incidence of fringe benefit performed is negatively related to the employee turnover rate.

Hypothesis 4b: The average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer is negative in relation to employee turnover rate.

Methods Data sources

Secondary data consisting of the Census Bureau Employment Movement Survey (EMS) datasets, collected by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics

(DGBAS) in Taiwan is adopted in this study. This survey is conducted from February to March of each year, and is designed to describe the workforce mobility and organization of work of the previous year. The dataset covers the firm’s workforce mobility information (such as accession and separation), the company’s background (such as industry, the number of employees and workforce demography) and the application of HR practices specified on the compensation and benefit packages (such as regular earning adjustments scale, employed pay for premium, employed pay for retirement fund, redundancy payment, employed pay for welfare fund and other welfare disbursements). EMS is an annual survey that randomly chooses the firms each year as representative samples. However, since DGBAS is regulated by statistical laws in Taiwan, DGBAS could not provide detailed information for longitudinal or extended analyses. Hence, the EMS datasets are only suitable for cross-sectional analysis.

The EMS target populations for industry sector firms are classified into nine types; this study primarily examines the impacts of benefit plans on manufacturing industry firms. Moreover, not every organization adapts the HR practices. In a company with more than ten employees, the owner will be likely to take care of HR issues (Mathis and Jackson, 2003). Firms composed of fewer than ten employees were removed from this analysis. In addition, HR practices in state-owned firms are regulated by the government, and are relatively different from the private firm’s HR practices derived from strategic considerations; thus, state-owned firms are also removed from this analysis.

Measures

The dependent variable in the study is the per firm employee turnover rate and is defined by the US Department of Labor as below.

Turnover rate ¼ Number of seperations Total number of employed workers

Benefit practices are the examining antecedents of employee turnover rate in this study. The chosen variables from EMS datasets are the retirement fund, pension, severance pay and fringe benefits. A more detailed description of the measurement variables are illustrated below.

1 1RF: with retirement fund (RF ¼ 1); without (RF ¼ 0).

ARF: the average amount contributed to the retirement fund or account (per employee, NT $).

2 PEN: with pension performed (PD ¼ 1); without (PD ¼ 0).

APEN: the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account (per retired employee, NT $).

3 SEV: with severance pay performed (SEV ¼ 1); without (SEV ¼ 0).

ASEV: the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (per retired employee, NT $).

4 FB: with fringe benefit performed (FB ¼ 1); without (FB ¼ 0).

AFB: the average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer (per employee, NT $).

Three control variables are covered in this study, namely, firm size, firm location and firm employees’ average educational attainment. The number of participants (usually the number of employees1) is the main measure of firm size in most studies which investigate the relationships between size and employment-related variables (e.g. HR practices).

Firm location is classified into four areas and nominated by category. The firm employees’ average educational attainment is the transformed index.2 The index is calculated from each category weight multiplied by the number of workers in this classification, and then the total amount is summed. In order to standardize by firm size, this index is also divided by the firm size. The employees’ average educational attainment index is defined below:

EDU ¼

Xj i¼1

ðWeighti£ niÞ

Firm size j: the number of employees’ educational attainment category ni: the number of employee in category i

Model specification

Four benefit plans are the dependent variables: retirement fund, pension disbursement, severance pay and fringe benefit. Two models are examined: inducement model and investment model. The inducement model tests the differing impacts with or without benefit plans. The investment model examines the effects of the average amount of benefit plan payments on employee turnover. In other words, the inducement model tests the impacts of with or without, while the investment model tests the impacts of the more, the better. The two models are presented as follows:

Model 1: Inducement model

Turnover rate ¼ f (control variables, RF, PEN, SEV, FB) Model 2: Investment model

Turnover rate ¼ f (control variables, ARF, APEN, ASEV, AFB)

Data where the employee turnover rate equals zero are removed; and then the others are transformed by natural logarithm to reduce the biased estimates due to data censoring. The firm size, firm location and employees’ average educational attainment are treated as the control variables. In the following regression analysis, firm size (the total number of employees in the firm) is transformed by natural logarithm because the original values are positively skewed; firm location is recoded into four dummy variables (group of other places is the reference); firm employees’ average educational attainment is transformed by Z score. Additionally, the average amount of each benefit plan disbursement is transformed by natural logarithm of the original value plus one. Both models used ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate the coefficients. In addition, the Chow test is also used in this study to test for pooling together or separating analysis. Results

The Chow test first examines the consistency on pooling datasets for the years 2000 and 2001 as one. Results nullify both Model 1 (inducement model) (F ¼ 2.4853) and Model 2 (investment model) (F ¼ 2.2696) statistically significantly; namely, pooling the two-year datasets for subsequent analysis is validated.

Of the 5,169 manufacturing industry firms covers in this study, 84.69 per cent (n ¼ 4,378) had retirement funds, 35.50 per cent (n ¼ 1,810) provided pensions, 24.9 per cent (n ¼ 1,287) had severance pay, and 55.4 per cent (n ¼ 2,863) adopted fringe benefits. Additionally, firm locations were, 21.6 per cent (n ¼ 1,155) in Taipei

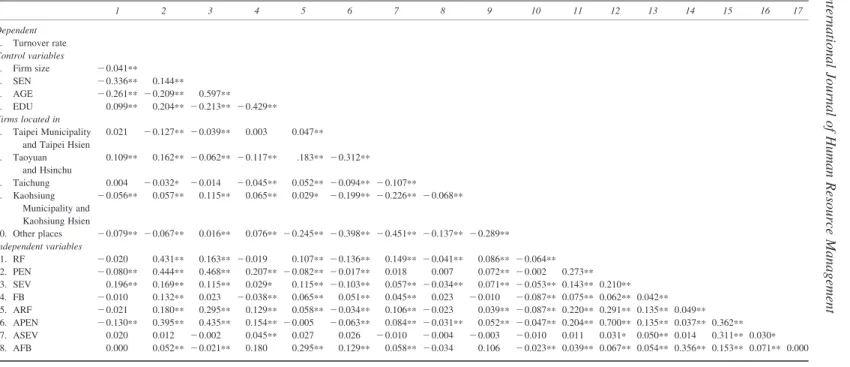

Municipality and Taipei Hsien, 26.1 per cent (n ¼ 1,350) in Taoyuan and Hsinchu, 3.1 per cent (n ¼ 162) in Taichung, 12.6 per cent (n ¼ 653) in Kaohsiung Municipality and Kaohsiung Hsien. Table 1 reports the correlation coefficients of the variables. The employee turnover rate is negatively related to a statistically significant level (at p , 0.01 level) with pension performed (PEN), the average amount of pension disbursement per employee (APEN), firm size, average employees’ seniority (SEN) and average employees’ age (AGE). On the other hand, the employee turnover rate is positively correlated significantly (at p , 0.01 level) with inducing severance pay performed (SEV), firm employees’ average educational attainment (EDU) and firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu. Incidentally, firm size is positively correlated significantly (at p , 0.01 level) with retirement fund (RF), pension performed (PEN, severance pay performed (SEV) and fringe benefit performed (FB), the average amount of contributed to the retirement fund by the employer per employee (ARF), average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account per employee (APEN) and the average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer per employee (AFB). Table 2 presents the cross-analysis by firm location and shows that the employee turnover rate in Taoyuan and Hsinchu is higher than in other locations; in addition, firm employees’ average educational attainment in Taoyuan and Hsinchu is also the highest.

Empirical model analysis

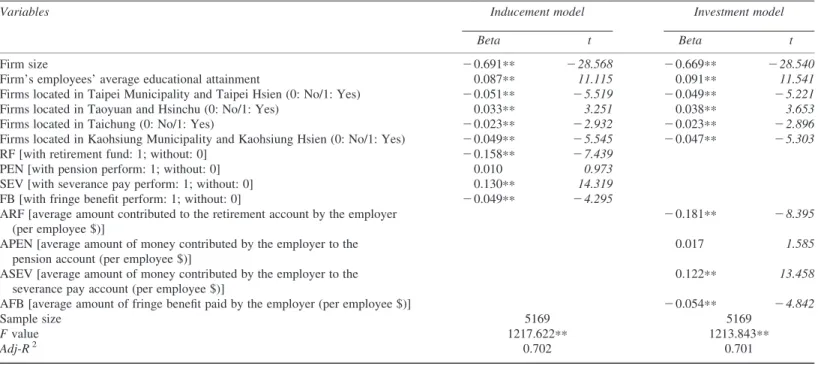

Hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses were used to test the hypotheses. First, a controlled model containing all control variables (i.e. firm size, firm location and firm employees’ average educational attainment) was seen to be statistically significant (F ¼ 1924.07, p, 0.01, adj-R2¼ 0.69); all control variables are non-collinear (all tolerance values are not less than 0.1). Firm size (b ¼ 2 0.46, p , 0.01) and firm employees’ average educational attainment (b ¼ 0.09, p, 0.01) are statistically significant. Notably, firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu, containing the highest density of high-tech firms in Taiwan, are positively (b ¼ 0.020, p ¼ 0.054) related to employee turnover to a fairly significant level. Furthermore, regression is conducted by removing the variable of employees’ average educational attainment. This model is further supported by the fact that (F ¼ 2164.73, adj-R2¼ 0.68) firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu are significantly positive (b ¼ 0.044, p , 0.01) as to employee turnover rate. This result was drawn from a cross-analysis, as shown in Table 2, where firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu have higher employees’ average educational attainment and employee turnover rate than firms located in other locations. Most high-tech industry firms in Taiwan are located in this area. Hence, this indirectly supports the idea we stated before that the employee turnover rate is higher in knowledge-based or high-tech firms. The two-model regression analysis result is shown in Table 3. The inducement model (F ¼ 1,217.622, p , 0.01, adj-R2¼ 0.702) and investment model (F ¼ 1,213.843, p , 0.01, adj-R2¼ 0.701) are both statistically significant. The effects of retirement fund (RF) and fringe benefits (RB) are negatively correlated with employee turnover, whereas severance pay (SEV) is positively correlated with employee turnover to a statistically significant level ( p , 0.01). These results support Hypotheses 1a, 3a and 4a. In addition, the effects of the average amount contributed to the retirement account by the employer (ARF) and the average amount of fringe benefits paid by the employer (AFB) are negatively related to a statistically significant level ( p , 0.01), whereas the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (ASEV) is positively related to a statistically significant level ( p , 0.01). Hence, these results support Hypotheses 1b, 3b and 4b.

Table 1 Correlations among variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Dependent 1. Turnover rate Control variables 2. Firm size 2 0.041** 3. SEN 2 0.336** 0.144** 4. AGE 2 0.261** 2 0.209** 0.597** 5. EDU 0.099** 0.204** 20.213** 20.429** Firms located in 6. Taipei Municipality and Taipei Hsien

0.021 2 0.127** 20.039** 0.003 0.047** 7. Taoyuan and Hsinchu 0.109** 0.162** 20.062** 20.117** .183** 20.312** 8. Taichung 0.004 2 0.032* 2 0.014 2 0.045** 0.052** 20.094** 2 0.107** 9. Kaohsiung Municipality and Kaohsiung Hsien 2 0.056** 0.057** 0.115** 0.065** 0.029* 2 0.199** 2 0.226** 2 0.068** 10. Other places 2 0.079** 2 0.067** 0.016** 0.076** 20.245** 20.398** 2 0.451** 2 0.137** 20.289** Independent variables 11. RF 2 0.020 0.431** 0.163** 20.019 0.107** 20.136** 0.149** 2 0.041** 0.086** 20.064** 12. PEN 2 0.080** 0.444** 0.468** 0.207** 20.082** 20.017** 0.018 0.007 0.072** 20.002 0.273** 13. SEV 0.196** 0.169** 0.115** 0.029* 0.115** 20.103** 0.057** 2 0.034** 0.071** 20.053** 0.143** 0.210** 14. FB 2 0.010 0.132** 0.023 2 0.038** 0.065** 0.051** 0.045** 0.023 2 0.010 2 0.087** 0.075** 0.062** 0.042** 15. ARF 2 0.021 0.180** 0.295** 0.129** 0.058** 20.034** 0.106** 2 0.023 0.039** 20.087** 0.220** 0.291** 0.135** 0.049** 16. APEN 2 0.130** 0.395** 0.435** 0.154** 20.005 2 0.063** 0.084** 2 0.031** 0.052** 20.047** 0.204** 0.700** 0.135** 0.037** 0.362** 17. ASEV 0.020 0.012 2 0.002 0.045** 0.027 0.026 2 0.010 2 0.004 2 0.003 2 0.010 0.011 0.031* 0.050** 0.014 0.311** 0.030* 18. AFB 0.000 0.052** 20.021** 0.180 0.295** 0.129** 0.058** 2 0.034 0.106 2 0.023** 0.039** 0.067** 0.054** 0.356** 0.153** 0.071** 0.000 Notes:

1 Turnover rate and firm size are transformed by natural logarithms. 2 n ¼ 5169. ** p , 0.01; * p , 0.05. The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Location n (%)a Employee turnover rate (%) (SD) Firm employees’ average educational attainment index (SD) With retirement fund (%)b With pension perform (%)b With severance pay (%)b With fringe benefit (%)b Taipei Municipality 1115 33.38 3.056 840 286 262 672

and Taipei Hsien (21.6) (0.5749) (0.6346) (75.3) (25.7) (23.5) (60.3)

Taoyuan and Hsinchu 1350 40.07 3.192 1265 535 354 799

(26.1) (0.6016) (0.7036) (93.7) (39.6) (26.2) (59.2)

Taichung 162 32.56 3.179 124 42 43 100

(3.1) (0.3850) (0.4647) (76.5) (25.9) (26.5) (61.7)

Kaohsiung Municipality 653 32.82 3.047 606 288 215 353

and Kaohsiung Hsien (12.6) (0.5863) (0.5686) (92.8) (44.1) (32.9) (54.1)

Other places in Taiwan 1889 27.98 2.7983 1543 659 413 939

(36.5) (0.3014) (0.5251) (81.7) (34.9) (21.9) (49.7)

Notes:

1 n is the number of firms in dominated location. The number of total firms is 5,169.

2athe percentage of firms in dominated location;bthe percentage of firms adopted categorical benefit plan in dominated firm’s location.

Lee et al.: Impacts of benefit plans on employee turnover 1963

Table 3 Regression analysis of inducement and investment model

Variables Inducement model Investment model

Beta t Beta t

Firm size 2 0.691** 2 28.568 2 0.669** 2 28.540

Firm’s employees’ average educational attainment 0.087** 11.115 0.091** 11.541

Firms located in Taipei Municipality and Taipei Hsien (0: No/1: Yes) 2 0.051** 2 5.519 2 0.049** 2 5.221

Firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu (0: No/1: Yes) 0.033** 3.251 0.038** 3.653

Firms located in Taichung (0: No/1: Yes) 2 0.023** 2 2.932 2 0.023** 2 2.896

Firms located in Kaohsiung Municipality and Kaohsiung Hsien (0: No/1: Yes) 2 0.049** 2 5.545 2 0.047** 2 5.303

RF [with retirement fund: 1; without: 0] 2 0.158** 2 7.439

PEN [with pension perform: 1; without: 0] 0.010 0.973

SEV [with severance pay perform: 1; without: 0] 0.130** 14.319

FB [with fringe benefit perform: 1; without: 0] 2 0.049** 2 4.295

ARF [average amount contributed to the retirement account by the employer (per employee $)]

2 0.181** 2 8.395

APEN [average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account (per employee $)]

0.017 1.585

ASEV [average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (per employee $)]

0.122** 13.458

AFB [average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer (per employee $)] 2 0.054** 2 4.842

Sample size 5169 5169

F value 1217.622** 1213.843**

Adj-R2 0.702 0.701

Notes:

1 Dependent variable is employee turnover rate and transformed by natural logarithm. 2 Beta is the standardized coefficient.

3 *p , 0.01;* p , 0.05;†p , 0.10. The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Inducement model analysis

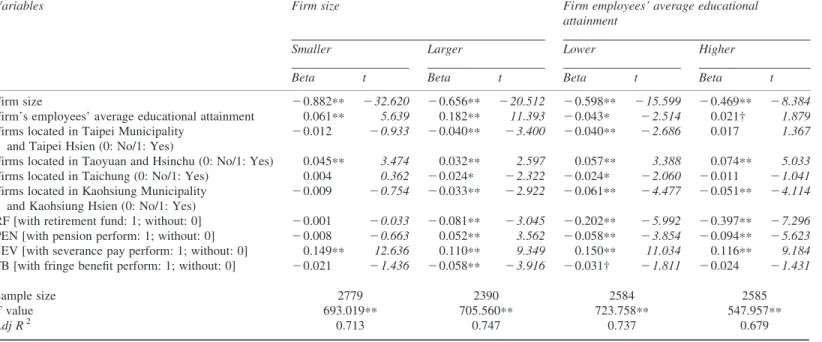

Moreover, the inducement models significantly differ between the larger and smaller firm sizes (F ¼ 87.16, p , 0.01). Thus, the separated regression (i.e. by firm size) was manipulated and the results are presented in Table 4. For the smaller size firms, the effects of severance pay performed (SEV) is positive significantly (at p , 0.01 level). For the larger size firms, the effects of with retirement fund (RF) and with fringe benefit performed (FB) are negative; whereas, with pension performed (PEN) and with severance pay performed (SEV) are positive significantly (at p , 0.01 level). Comparing the standardized regression coefficient, the effect of severance pay in smaller firms (b ¼ 0.15, p , 0.01) is higher than in larger firms (b ¼ 0.12, p , 0.01). Moreover, the effects of retirement fund or pension on employee turnover are only significant for larger firm sizes. That is, a larger sized firm has abundant resources to utilize employee retaining HR practices to reduce the costs of the market arrangement (transaction costs). Hence, Hypothesis 3a is supported in smaller sized firms; Hypotheses 1a, 2a and 3a are supported in larger sized firms.

The F value of the Chow test (F ¼ 24.97, p , 0.01) also supports the inducement models of higher and lower employees’ average educational attainment firms being significantly different. Interestingly, in both sub-groups, the effects of there being a retirement fund (RF) or pension (PEN) are negative; nevertheless, severance pay provision (SEV) is positive to a statistically significant level (at p , 0.01). Comparing the standardized regression coefficient, the negative effect of retirement fund provision (RF) in firms with higher average employees’ educational attainment is greater than in firms with lower average employee educational attainment. The effects of fringe benefit provision (FB) on decreasing employee turnover are more useful in firms with lower average employee educational attainment.

Additionally, severance pay performed (SEV) in firms with higher average employee educational attainment caused more employees to leave than in firms with lower average employee educational levels. The reasons for this can be explained from the employee’s perspective. First, higher educational level employees have more job opportunities; thus, leaving the existing firm not only involves the costs of unemployment but also yields higher severance pay. Otherwise, severance pay being given is a sign of a business crisis; thus, it also increases employee turnover, especially for those with higher proportions of human capital workforce. As expected, the effect of pension provision (PEN) is negatively correlated to a statistically significant level in firms with higher average employee educational attainment. Notably, the positive effects to a statistically significant level are present in firms with lower average employee educational attainment. This is because the less knowledge-oriented firms would be eliminated through market competition, that is, pension provision encourages employees, especially those with less competent or older workforces, to leave the firms with lower average employee educational attainment firm more early. Hence, Hypotheses 1a, 3a and 4a are supported in firms with both lower and higher employee educational levels. Hypothesis 2a is only supported in firms with higher employee educational levels.

Investment model analysis

The investment model significantly differs according to firm size when measured by the Chow test (F ¼ 56.99, p , 0.01). Thus, individual regression analysis was used and the results are shown in Table 5. In the smaller sized firms, the effects of the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (ASEV) is positive significantly (at p , 0.01 level). In the larger sized firms, the effects of

Table 4 Regression analysis of inducement model

Variables Firm size Firm employees’ average educational

attainment

Smaller Larger Lower Higher

Beta t Beta t Beta t Beta t

Firm size 2 0.882** 2 32.620 2 0.656** 2 20.512 2 0.598** 2 15.599 2 0.469** 2 8.384

Firm’s employees’ average educational attainment 0.061** 5.639 0.182** 11.393 2 0.043* 2 2.514 0.021† 1.879

Firms located in Taipei Municipality and Taipei Hsien (0: No/1: Yes)

2 0.012 2 0.933 2 0.040** 2 3.400 2 0.040** 2 2.686 0.017 1.367

Firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu (0: No/1: Yes) 0.045** 3.474 0.032** 2.597 0.057** 3.388 0.074** 5.033

Firms located in Taichung (0: No/1: Yes) 0.004 0.362 2 0.024* 2 2.322 2 0.024* 2 2.060 2 0.011 2 1.041

Firms located in Kaohsiung Municipality and Kaohsiung Hsien (0: No/1: Yes)

2 0.009 2 0.754 2 0.033** 2 2.922 2 0.061** 2 4.477 2 0.051** 2 4.114

RF [with retirement fund: 1; without: 0] 2 0.001 2 0.033 2 0.081** 2 3.045 2 0.202** 2 5.992 2 0.397** 2 7.296

PEN [with pension perform: 1; without: 0] 2 0.008 2 0.663 0.052** 3.562 2 0.058** 2 3.854 2 0.094** 2 5.623

SEV [with severance pay perform: 1; without: 0] 0.149** 12.636 0.110** 9.349 0.150** 11.034 0.116** 9.184

FB [with fringe benefit perform: 1; without: 0] 2 0.021 2 1.436 2 0.058** 2 3.916 2 0.031† 2 1.811 2 0.024 2 1.431

Sample size 2779 2390 2584 2585

F value 693.019** 705.560** 723.758** 547.957**

Adj R2 0.713 0.747 0.737 0.679

Notes:

1 Dependent variable is employee turnover rate and transformed by natural logarithm. 2 Beta is the standardized coefficient.

3 ** p , 0.01;* p , 0.05; † p , 0.10. The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Variables Firm size Firm employees’ average educational attainment

Smaller Larger Lower Higher

Beta t Beta t Beta t Beta t

Firm size 2 0.874** 2 33.331 2 0.363** 2 7.269 2 0.648** 2 20.400 2 0.563** 2 15.393

Firm’s employees’ average educational attainment 0.061** 5.717 0.021† 1.901 0.184** 11.485 2 0.039* 2 2.290

Firms located in Taipei Municipality and Taipei Hsien (0: No/1: Yes)

2 0.012 2 0.893 0.023† 1.812 2 0.038** 2 3.243 2 0.037* 2 2.519

Firms located in Taoyuan and Hsinchu (0: No/1: Yes)

0.046** 3.495 0.086** 5.844 0.034** 2.775 0.062** 3.677

Firms located in Taichung (0: No/1: Yes) 0.004 0.340 2 0.011 2 0.995 2 0.025* 2 2.390 2 0.023* 2 1.977

Firms located in Kaohsiung Municipality and Kaohsiung Hsien (0: No/1: Yes)

2 0.008 2 0.695 2 0.047** 2 3.815 2 0.031** 2 2.740 2 0.060** 2 4.389

ARF [average amount contributed to the retirement account by the employer (per employee $)]

2 0.008 2 0.354 2 0.525** 2 10.350 2 0.094** 2 3.439 2 0.236** 2 6.982

APEN [average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account (per employee $)]

2 0.009 2 0.793 2 0.072** 2 4.311 0.057** 3.841 2 0.053** 2 3.467

ASEV [average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (per employee $)]

0.145** 12.296 0.111** 8.823 0.101** 8.601 0.145** 10.676

AFB [average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer (per employee $)]

2 0.022 2 1.504 2 0.030† 2 1.897 2 0.053** 2 3.638 2 0.045** 2 2.687

Sample size 2779 2390 2584 2585

F value 690.114** 723.252** 718.254** 549.814**

Adj R2 0.714 0.752 0.735 0.680

Notes:

1 Dependent variable is employee turnover rate and transformed by natural logarithm. 2 Beta is the standardized coefficient.

3 ** p , 0.01;* p , 0.05; † p , 0.10. Lee et al.: Impacts of benefit plans on employee turnover 1967

the average amount contributed to the retirement account by the employer (ARF) and the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account (APEN) are negative; however, the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (ASEV) is similarly positive significantly (at p , 0.01 level). Notably, the effects of investment on retirement fund (ARF) and pension performed (APEN) are only significant for the larger firm size. Comparing the standardized regression coefficient, the effect of expenditure on severance pay (ASEV) in smaller sized firms is higher than in larger sized firms. That is, Hypothesis 3a is supported in smaller sized firms; Hypotheses 1b, 2b and 3b are supported in larger sized firms.

The F value of the Chow test (F ¼ 15.31, p , 0.01) also supporting the investment models of firms with higher and lower average employee educational attainment are significantly different. In both sub-groups, the effects of the average amount contributed to the retirement account (ARF) and the average amount of fringe benefit paid by the employer (AFB) are negative significantly (at p , 0.01 level), whereas the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the severance pay account (ASEV) is positive significantly (at p , 0.01 level). In addition, the average amount of money contributed by the employer to the pension account is significantly (APEN) positive in firms with lower average employee educational attainment but negative in firms with higher average employee educational attainment. Hence, Hypotheses 1b, 3b and 4b are supported in both firms with lower and higher employee educational levels. Hypothesis 2b is only supported in firms with higher employee educational levels.

Additional analysis

From the above regression analysis the results of inducement and investment models reveal some interesting phenomena: the adjusted coefficient of determination and the standardized regression coefficient of these two models are non-significantly different. The effects of ‘with/without’ (inducement model) and ‘the more the better’ (investment model) seem also to be non-significantly different. However, from the transaction cost theory perspective, the investment model is hypothetically more beneficial than the inducement model. Thus, additional analysis examines whether there are differences between the inducement model and the investment model.3 The result reveals the residual sum squared (SSE) for the full model is 5436.27, SSE of restricted model is 5,488.92 and the F statistic (F ¼ 4.9907); thus, these significantly (at p , 0.01 level) reject the null hypothesis (i.e. non-difference between two models).

However, when examining electronic firms in the manufacturing industry, the SSE of the full model is 1,364.72 and SSE of the restricted model is 1,367.31; thus, it is non-significant (F ¼ 0.27) to reject the existing differences between the two models (at p , 0.01 level). Hence, the impacts of ‘the more the better (investment model)’ is not significantly different from the ‘with or without (inducement model)’ in regard to employee turnover. These results rather contrast with transaction cost perspective but are consistent with Barringer and Milkovich (1998) propositions explored from the institutionalization perspective.

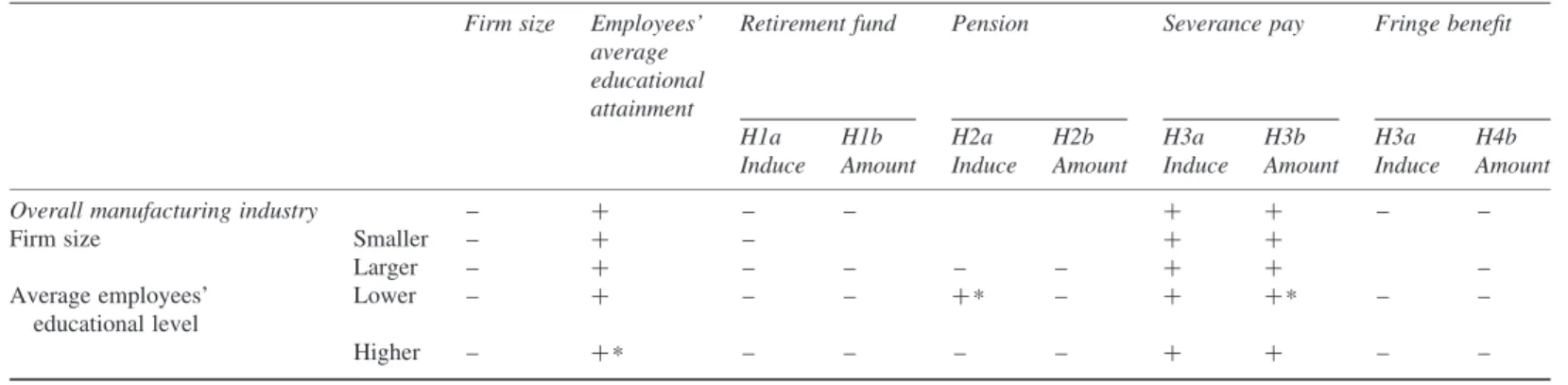

Conclusion

The hypotheses testing results are summarized in Table 6. Most hypotheses are supported statistically significantly; interestingly, three results are different from the hypothetical settings but supported significantly indeed. The employees’ average educational attainment is generally positive in relation to employee turnover; however, this effect is negative in firms with higher average employee educational attainment. This could be

Table 6 Summaries of hypotheses testing results

Firm size Employees’ average educational attainment

Retirement fund Pension Severance pay Fringe benefit

H1a H1b H2a H2b H3a H3b H3a H4b

Induce Amount Induce Amount Induce Amount Induce Amount

Overall manufacturing industry – þ – – þ þ – –

Firm size Smaller – þ – þ þ

Larger – þ – – – – þ þ – Average employees’ educational level Lower – þ – – þ * – þ þ * – – Higher – þ * – – – – þ þ – – Notes:

1 þ means positive to employee turnover rate; – means negative to employee turnover rate. 2 Blank means non-significant supported.

3 *indicates the effect is significant but the signal is reversed with hypothesis setting.

et al.: Impacts of benefit plans on employee turnover 1969

explained by resource-based theory, wherein higher human capital inventory is also the magnet for retaining employees in order to accumulate its own human capital. According to the resource-based theory, a larger sized firm has relatively abundant capability and capacity to adopt various HR practices, thus, enhancing employee retention and reducing employee separation. In addition, human capital theory highlights that employees with high educational levels prefer transferring jobs to accumulate and enhance self-owned human capital. Thus, firms with higher average employee educational attainment often experience higher levels of employee separation. Moreover, this also could be explained from the social capital theory perspective, the resource reflecting the characters of social relations within the organization are realized through the members’ levels of good collective orientation and shared trust (Leana and van Buren, 1999). That is, the value of knowledge creation is not only derived from individual human capital. The greater the value of the individual human capital embedded in the social capital of an organization, the greater the value of intelligence is created. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1996) make the important point that knowledge is created and expanded through social interaction. The returns from knowledge, facilitated by social capital, are subject to increasing returns (Dess and Shaw, 2001). That is, higher average employee educational attainment is the firm’s social capital and it also offers the human capital accumulating platform for the employee. The theory that firm size is negative in relation to the employee turnover rate is also supported by the results of this study; this is consistent with the resource-based theory perspective, the larger sized firm has abundant resources to use in retaining or attracting employees through employing HR practices, thus reducing the employee turnover rate.

This study draws the following conclusions. First, nearly 90 per cent of the firms in the Taiwan manufacturing industry implement retirement funds; almost half of the firms offer fringe benefit plans. About 35 per cent of the firms provide a pension and nearly a quarter of them offer severance pay. Second, the number of employees (firm size) significantly influences the implementation of benefit plans. Results reveal that relatively more employees have benefit plans in larger firms than in smaller firms. The average amount of money contributed to benefit plans also increases with increasing firm size. This finding is consistent with the resource-based theory perspective that a firm possessing abundant resources would allocate more to employee retention practices. Third, this study also finds some phenomena particular to firms located in the Taoyuan and Hsinchu districts, where there is a high concentration of knowledge-based and high-tech firms in Taiwan: higher average employee educational attainment means a higher employee turnover rate, and a higher proportion of firms providing benefit plans. Fourth, the empirical results reveal that firm size is negatively correlated with the employee turnover rate, which is consistent with the resource-based theory perspective. The employees’ average educational attainment is positively related to employee separation. However, this is not supported in higher human inventory firms. The reason can be explained from the social capital theory, but this is out of the scope of this study and is best left for future research.

Moreover, the effect of retirement fund is negative while the effect of severance pay is significant and positive to the employee turnover rate. However, the negative effects of fringe benefits are not totally supported in this study, especially in smaller sized firms. That is, fringe benefit plans are shared by membership. The costs of fringe benefits per employee decrease with increasing numbers of employees. That is, the costs of fringe benefits performed on each employee are higher in smaller sized firms. In the smaller sized firm, the bureaucratic costs of internal management with fringe benefits are higher than the costs of market arrangement, thus the effects of fringe benefits are not significant

in smaller sized firms. Hence, the firm decreases its expenditure on fringe benefit plans, thus the effect of fringe benefits on the employee turnover rate is not significant. Pension payments are also only supported in part; especially since there is a significant but positive effect (opposite to the proposed hypothesis) in firms with lower average employee educational attainment. The reason could be illustrated by the current value of the pension being perceived by the employee as higher than the future value of staying. Thus, pension payments increase the number of employees leaving and reduce the risks of uncertainty in the future. The effects of retirement fund and pension provision are not significant in this study. The costs of retirement funds or pensions are relatively higher than the costs of severance pay or market arrangements (severance pay). Additionally, the ability to pay pensions for smaller sized firms is less than for larger sized firms. Moreover, the retirement fund is bound with tenure; the survival risks of smaller sized firms are also relatively higher than those of larger sized firms. Hence, the effects of these two benefit plans are not significant.

The above research indicates that investments such as pay and benefits in the human capital of an organization reduce voluntary turnover. Strategic human resource management studies also suggest that commitment-enhancing HRM systems reduce turnover (Arthur, 1994). An investment-focused HRM strategy subsumes HRM practices to ensure a high quality human capital pool. Primary and certainly the most visible among an organization’s investments are its compensation and benefit packages. High pay promotes retention since employees’ self-interest is maximized by staying, and it promotes organizational self-interest through attraction and retention of a superior workforce (Williams and Dreher, 1992).

Moreover, offering fringe benefit plans significantly decreases employee turnover. This effect may be due to ‘job lock’: suffered by workers who are unable because of pre-existing conditions, for example, to attain fringe benefits should they quit their present job (Fairris, 2004). In addition, the provision of pension benefits is somewhat negatively related to workforce turnover; this lends support to the theory that the back-loading of benefits through pension plans reduces workforce turnover.

Finally, although additional analysis shows that the effects of ‘the more the better (investment model)’ are significantly different from the ‘with or without (inducement model)’ for the overall manufacturing industry analysis, in relation to the sub-manufacturing industry (i.e. electronic firms), the differences in the two models are non-significant. Contrary to the amount perspective of transaction cost theory, institutionalization somewhat dominates benefit plan implementation. Benefit plans have two unique aspects which distinguish them from other HR practices. First, there is the question of legal compliance (Noe et al., 2002) thus, government or law regulates the firm to adopt benefit plans coercively, such as a minimum proportion being paid into a retirement account or the pension disbursement mechanism. This is referred to as coercive isomorphism (Scott, 2001). Otherwise, the second unique aspect of benefit plans is that firms so commonly offer them that they have come to be institutionalized (Noe et al., 2002). This is the result of the industry or organizations’ tacit agreements (normative isomorphism), such as severance pay provision; or because firms mimic others to reduce risks of uncertainties (mimetic isomorphism), such as fringe benefit provision (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). That is, from the institutional theory, organizations are as they are for no reason other than the fact that they are bound to legitimize the organization. The organization tends to become isomorphic with the accepted norms for organization of a particular type or with contextual conditions (Scott, 2001). Hence, coercive isomorphism (regulated by law or government) and mimic isomorphism (following other firms’ behaviours) dominate the benefit plan implementations of the firms. Institutionalization

maybe exists in the sub-industry but not in the broad industry; this is to some extent supported in this study; however, inclusive exploration requires further study.

Research limitations and directions for future research

This study uses secondary data to investigate the empirical issues. Government surveys are regulated by related statistical law to protect the data supplier’s privacy. DGBAS cannot provide more firm business information. Moreover, the selected variables in this study are restricted by data frames. Some variables do not appropriately represent compensation or benefit practices. Most selected variables are specific as to benefit practices rather than compensation. In addition, EMS is a government survey, so that information on regulated practices may be exaggerated, such as the pay for retirement funds or the premium. The reliability of the survey information is therefore somewhat questionable.

Otherwise, many other factors, such as management practices, staffing and placement practices, training and development practice, or incentive pay practices influence employee turnover. The industry context is also an important factor affecting this issue. In the future, employee turnover research can be extended to analyse the workforce cross-industry turnover.

Finally, it should be mentioned that appropriate employee turnover is beneficial to firm performance. The issues surrounding how HR practices can affect employee turnover, which then affects financial performance, is another possible future research option. The purpose of human resource management is to convert workforce performance into corporate financial performance. Furthermore, the question of how to retain talented and valued employees to contribute to firm performance is rather critical in our current knowledge-based society.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on drafts of this manuscript. In addition, the first author gratefully acknowledges the instruction and helpful comments of Professor Joseph S. Lee at the Graduate Institute of Human Resource Management of National Central University in Taiwan.

Notes

1The definition of the number of employees by DGBAS is those white and blue-collar workers on the payroll at the end of the survey time, including full-time and part-time workers, permanent workers, temporary workers under projects, contract workers, students working under cooperation programmes between industries and schools (excluding those who do not work for a full month), and apprentices with pay. Also included are those who are temporarily on leave, such as going abroad on business trip, training, transfer, military training or education, illness, vacation, marriage and child delivery. However, excluded are: (1) employers participating in the operation without pay, own-account workers and unpaid family workers; (2) members of boards of directors, supervisors and advisors not actually participating the operation; (3) those who are drafted for military service with partial pay (such as rations in kind, rent subsidies and utilities allowances); (4) contracted workers outside the factories and paid by piece of work.

2The EMS questionnaire is designed to include seven nominal classifications to ask how many employees in each category. In order to convert into one indicator, each category is given a different weight. Those people who are illiterate or under elementary school level are nominated as one, junior high school level is nominated as two, senior high school and senior vocational school level as three, vocational college level as four, collage or university level as five, and above graduate school level as six.

3 Entering all variables (including control variables) of inducement and investment model, which is referred to as the full model (FM), the inducement model is referred to as the restricted model (RM). The distinct parameters, variables of the investment model, to be estimated in the reduced model are smaller than the number of parameters to be estimated in the full model. The null hypothesis is that all distinct parameters are equal to zero. Hence, if the null hypothesis is not rejected, then the restricted model, inducement model, will have to be chosen. Therefore, we can conclude that organizational practices are institutionalized, which is supported by the institutional theory perspective. The effects of ‘the more the better (investment model)’ is not significantly different from the ‘with or without (inducement model)’.

References

Allgood, S. and Farrell, K.A. (2000) ‘The Effect of CEO Tenure on the Relation between Firm Performance and Turnover’, Journal of Financial Research, 27(3): 373 – 90.

Arthur, J.B. (1994) ‘Effects of Human Resource Systems on Manufacturing Performance and Turnover’, Academy of Management Journal, 37(3): 670 – 88.

Bamberger, P., and Meshoulam, I. (2000) Human Resource Strategy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Barney, J.B. (1991) ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’, Journal of Management, 17: 99 – 120.

Baron, J.N. and Kreps, D.M. (1999) Strategic Human Resource Management: Framework for General Mangers. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Barrick, M.R. and Zimmerman, R.D. (2005) ‘Reducing Voluntary, Avoidable Turnover through Selection’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1): 159 – 66.

Barringer, M.W. and Milkovich, G.T. (1998) ‘A Theoretical Exploration of the Adoption and Design of Flexible Benefit Plans: A Case of Human Resource Innovation’, Academy of Management Review, 23(2): 305 – 24.

Batt, R. (2002) ‘Managing Customer Services: Human Resource Practices, Quit Rates, and Sales Growth’, Academy of Management Journal, 45(3): 587 – 97.

Batt, R., Colvin, A.J.S. and Keefe, J. (2002) ‘Employee Voice, Human Resource Practices, and Quit Rates: Evidence from the Telecommunications Industry’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55(4): 573 – 95.

Bennett, N., Blum, T.C., Long, R.G. and Roman, P.M. (1993) ‘A Firm-Level Analysis of Employee Attrition’, Group and Organization Management, 18(4): 482 – 500.

Bohlander, G., Snell, S and Sherman, A. (2001) Managing Human Resources (12th edn). Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing.

Campion, M.A. (1991) ‘The Meaning and Measurement of Turnover: A Comparison of Alternative Measures and Recommendations’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(2): 199 – 212.

Chang, P.L. and Chen, W.L. (2002) ‘The Effect of Human Resource Management Practices on Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from High-Tech Firms in Taiwan’, International Journal of Management, 19(4): 622 – 31.

Dawn, G. (1993) ‘How Companies Fund Retiree Medical Benefits’, Personnel Journal, 72(11): 78 – 86.

Dess, G.G. and Shaw, J.D. (2001) ‘Voluntary Turnover, Social Capital, and Organizational Performance’, Academy of Management Journal, 26(3): 446 – 56.

DiMaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983) ‘The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields’, American Sociology Review, 48(2): 147 – 60. Dreher, G.F., Ash, R.A. and Bretz, R.D. (1988) ‘Benefit Coverage and Employee Cost: Critical

Factors in Explaining Compensation Satisfaction’, Personnel Psychology, 41(2): 237 – 54. Even, W.E. and Macpherson, D.A. (1996) ‘Employer Size and Labor Turnover: The Role of

Pensions’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 49(4): 707 – 28.