Vol. 25, No. 2, June 2013, 257–280

Reorienting Taiwan into the Chinese Orbit:

Power Analysis of China’s Rise in Promotion

of China’s One-China Principle in International Structures

Scott Y. Lin*National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan

Being the second largest economy with the largest foreign exchange reserves, not only has China joined most international governance mechanisms, but it is also expected to carry more responsibility in international governance, especially after 2008. As more doors open for China, the country develops more power resources. Therefore, its longstanding One-China Principle shows no signs of wavering but will be advanced as China’s participation in international governance continues to expand. One significant consequence of China’s accelerating integration into international governance is the continual forcing of Taiwan into China’s orbit. Heretofore, the greatest pressure on Taiwan has been a growing number of global agents acknowledging Taiwan as an integral part of China. With China’s more prominent global role, that pattern gradually threatens to become an “international consensus” that conditions Taiwan’s development. This paper carefully uses a dyad of concepts of power analysis to measure the process of China’s promoted power in and through international governance for building structures, wherein the application of the One-China Principle is reorienting Taiwan into the Chinese orbit.

Keywords: power analysis, structural power, power, governance, China, Taiwan, One-China Principle

Introduction: An Ongoing China Fever within Taiwan’s Politic

The renowned ancient Chinese military treatise by Sun Tzu, The Art of War, stated that “supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.” The following story plays out this scenario: China is winning in the battle for Taiwan without fighting.

On October 4, 2012, former Taiwan Premier Frank Hsieh ( ) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), a pro-independence party, embarked on his groundbreaking trip to China. As one of the DPP’s top leaders, who recognized “constitutional One-China ( )” as encompassing his recent advocacy for a “constitutional consensus ( )” and “one Constitution, two interpretations ( ),” Hsieh’s five-day visit to China was a strong political symbol both globally and domestically.

*E-mail: scottlin@nccu.edu.tw ISSN 1016-3271 print, ISSN 1941-4641 online © 2013 Korea Institute for Defense Analyses http://www.kida.re.kr/kjda

In fact, Hsieh’s trip to China was merely one of a series of stories representing Taiwan’s shifting China and foreign policies from constructing a “Taiwan entity” into accepting “One-China.” Back in May 2008, when President Ma Ying-jeou and his pro-unification Kuomintang Party (KMT) returned to power in Taiwan after eight rocky years of DPP’s pro-independence rule led by former President Chen Shui-bian, tensions across the Taiwan Strait were greatly reduced by Ma’s acceptance of a One-China vision, resulting in continuing improvement in Cross-Strait relations. In the past four years, Taiwan and China have not only resumed their negotiation agenda but have signed eighteen agreements, largely covering direct Cross-Strait flights, opening Taiwan’s doors to Chinese tourists, food safety, financial supervisory cooperation, mutual judicial assistance, joint combating of crime, trade agreements in an Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA), investment protection, and Renminbi clearing in Taiwan.

In addition, Ma’s recent re-election has further accelerated Cross-Strait negotia-tions in the 2012 post-election period. On March 22, 2012, President Ma sent former KMT chairman, Wu Poh-hsiung, to meet with former Chinese President Hu Jintao in Beijing at the annual forum between the KMT and the CCP (Chinese Communist Party), during which Wu raised a proposal to define Cross-Strait relations as “one country, two areas (Taiwan Area and Mainland Area, ).” Despite no new developments, this definition was the first time that Ma made the concept “official” to his Chinese counterpart and signaled the ongoing reinterpretation of “One-China.” Because President Ma, in the election campaign in October 2011, publicly announced that Taiwan was prepared to sign a peace treaty with China within the next decade, local media and scholars speculated that this political gesture was intended to pave the way for both sides to enter Cross-Strait political negotiations within the One-China framework.1Consequently, for both the DPP and the KMT, the interpretation of “One-China” has become a pivotal point for their political futures.

These recent developments signal that, with China’s rise being a reality, Taiwan’s domestic politics has been caught up in a China fever that reorients it to the work of interpreting “One-China.” One notable feature of this reorientation is that the position of Taiwan seems to be falling into the Chinese orbit. Thus, why and how China is able to take advantage of its ever-growing power to reorient Taiwan to accept the One-China vision is a research question for this study.

Some scholars have noted that China’s overwhelming military and economic power is a key point causing Taiwan to accept the One-China vision. Accordingly, Taiwan’s freedom of action continues to erode and will be sacrificed for a stable international governance structure.2 However, a limitation of the above explanation is that the analytic viewpoint largely starts from realism or neorealism and considers power coming only from a particular agency—an agent-centered concept, in this case China—and omits the social interactions between power and international governance. In recent studies, some scholars have attempted to mix social constructionism and neoinstitutionalism to explain how the idea of One-China was constructed in institution-alizing agencies’ One-China policies.3 However, this explanation tends to emphasize power coming from institutionalization—a structure-centered concept, in this case, the One-China vision—and ignores how an agent’s rising ability and personality continually influence other agents’ perceptions of structures. Both approaches presume power is accessed unilaterally, either at the agent level or at the structure level, and lack sensitivity in diagnosing the unceasing social interactions between agents and

structures. The problem with these singular concepts of power is that they make it difficult to measure how China has been able to take advantage of structures to exercise power over Taiwan after 2008 when it was relatively difficult to do so before 2008.

Thus, this paper will use power analysis derived from a dyad of concepts, including (1) an agent’s power in (2) international governance4 composing structural power phenomena, to argue that Beijing’s longstanding One-China Principle (OCP), a political formula indicating “there is only one China in the world, Taiwan is an inalienable part of China, and the government of the PRC is the sole legal government representing the whole of China,”5will be further advanced as China’s power resources continue to expand and, more importantly, to satisfy the expectations of international governance after the 2008 financial crisis, forcing Taiwan to be pulled into orbit around China. The analysis will consist of four parts. First, while many international relations (IR) studies have already explained how and why countries manage power in and through international governance composing structures, these achievements will be examined in relation to power analysis. Second, the historical background and international interactions of the application of the One-China vision to different One-China policies will be illustrated. Third, because the globalization trend has involved China more deeply in the global community, a dyad of concepts of power analysis will measure Beijing’s increasing power in and through its favorable international governance and will explain its stricter application of the OCP to the international structures. Last, a measurement from power analysis will help reconsider the Taiwan issue in the era of globalization.

Theoretical Framework:

Power Analysis of Structural Power Phenomena in the IR Debates

For the theoretical framework, qualitative data are analyzed to reconsider important IR theory debates about structural power, which has largely been exclusively studied in terms of interactions between powerful countries instead of considering social relations between agencies and governance mechanisms. In the IR field, the perspective of international anarchy is materially important in the pursuit of international orders and norms, both of which comprise international structures. During such building processes, military power is always emphasized as a state’s ultimate power to control other countries and to effect a set of favorable international structures.6This military-centric perspective of formulating state power, however, draws on only one dimension of power, neglecting the greater picture of other relevant types of power in structures. Because this singular and biased definition is challenged in explaining outcomes of post-Cold War international security issues,7 a broader consideration of power, dependent on human relationships or governance, is brought into the discussion of power analysis.

Waltz was the first scholar to posit that, in an anarchical international system, international structures are a “set of constraining conditions” that act “through socialization of the actors and through competition among them.”8Criticizing Waltz’s structural realism, Guzzini later advances the concepts of power and their implication in the formation of international structures. Power in social relations, as expanded by Guzzini,9must be understood in accordance with international governance that shapes international structures. As a result, power phenomena exist both in terms of agential

interactions and governance effects, composing the structural power phenomena. Guzzini categorizes IR’s studies of structural power phenomena into three areas: indirect institutional power, non-intentional power, and governance’s impersonally empowering effects.10 Indirect institutional power is based on a relational concept that explains how power can be observed in regimes’ agenda setting, which simulta-neously constructs normative structures. Thus, a state needs to improve its power in a given social relation by either quantitative improvement of relevant power resources or qualitative change in the environment that defines relevant power resources. Second,

non-intentional power refers to a dispositional concept that also develops in global

networks but is perceived as an unintended effect of an agent’s inherent character. Such unintended outcomes are largely attributed to a state’s personality or hegemony, which is able to shape security, trade, political, and knowledge structures.

Finally, impersonally empowering effects are not located at the level of agents but in the interactions of international governance; therefore, this structural power phenomenon must be regarded as governance effects rather than an agent’s power. This type of effect involves a positional concept that indicates biased international governance interactions that systematically give advantages to certain agencies because of their special positions or roles in the system. These positional advantages allow the agencies benefitting from them to build favorable links between epistemic bases and power resources, thereby reproducing and strengthening international structures. In other words, social interactions of international governance “mobilize rules for agenda setting that privilege specific agencies; that is, the agency’s actual power in a bargain is fostered by the system’s governance.”11 Guzzini especially emphasizes the concept of impersonally empowering effects is not just “systematic luck” but stems from a series of social reproductions that must be “understood as a ritual of power that not only rests on those who benefit from the system but also needs all those who, via their conscious or unconscious practices, help to sustain it.”12

However, Guzzini is not satisfied with the above three distinct discussions of structural power phenomena for power analysis of structures. Rather, he asserts a comprehensive and coherent power analysis must encompass a pair of concepts— power and governance—in which power is reserved as an agent concept and governance represents effects of social interactions. In his conceptualization, power is regarded as an agent’s “capacity for effecting, that is, transforming resources, which affects social relationships,” whereas governance “includes both the social construction of options … and the routine mobilizing of bias that affects social relationships.”13As a result, the concept of power can account for the first two discussions of structural power phenomena—indirect institutional power and non-intentional power—and the concept of governance applies to the rest of the discussion of structural power phenomena: impersonally empowering effects. Therefore, focusing on social inter-actions among agents’ inter-actions, feedbacks, and structures allows conceptualization of power analysis integrating a dyad of concepts between agents’ power and governance norms. Thus, a complete power analysis must be regarded as an intersubjective one. “Individual power, understood as ability, is couched in an environment that is not just any objective regime or a position in the market/balance of power but an intersubjective realm where rituals of power continually set the stage.”14 That is, structural power phenomena lie both in the social interactions of agents and in the governance norms that result from these interactions. They continually construct (and deconstruct) so-called structure, which must be analyzed from the above-mentioned dyadic concepts

of power analysis: the social interactions between an agency’s actual power/social patterning and its embedded governance mechanism’s social construction/ritualized bias.

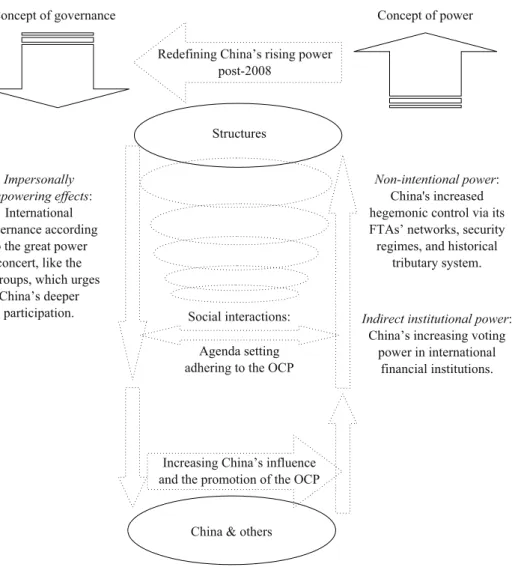

Moreover, by recognizing Wendt’s constructivism, Guzzini’s recent work again stresses the importance of a dyadic approach to analyzing agent-governance relations. “The choice of a dualist ontology, respecting both agency and [governance] structure, is carried out through a threefold conceptual split: at the level of action (between identity/interests and behavior), at the level of structure (between a macro- and a micro-structure) and in their feedback relation (between constitutive and causal links).”15From this conceptual apparatus, “constructivist theories tend to understand power as both agential [e.g., indirect institutional power] and intersubjective (including non-intentional and impersonal power), and they are also more attuned to questions of open or taken-for-granted and ‘naturalized’ legitimation processes.”16 Hence, modern social theories of power analysis—including Foucault’s structural power from knowledge building process,17Bourdieu’s structural power from cultural production,18 and Lukes’ three-dimensional view of overt, covert, and structural power19—are considered in Guzzini’s conceptual work on power analysis. Figure 1 and Table 1

present this conceptualization of power analysis including the three discussions of structural power phenomena. Thus, the discussion of power analysis for today’s international structures becomes possible. This typology provides a concrete theoretical foundation for the analysis of the OCP in current international structures.

Historical Background: The Evolution of the One-China Vision

As indicated, “meanings are derived from the pertinent contexts in which the concept has been used;”20therefore, power analysis must take into account the societal back-ground that evolves from a structure’s history. To analyze the effect of China’s rising power and favorable governance effects on its OCP in the international structure, reviewing the historical background of the One-China vision is necessary.

At the end of World War II, the government of the Republic of China (ROC), as arranged by the Cairo Declaration in 1943 and the Potsdam Declaration in 1945, legally took over Taiwan from a surrendered Japanese government and officially restored Taiwan to Chinese territory. As a result, both Mainland China and Taiwan Island belonged to one country, the ROC, until the end of the 1940s, when the Chinese Civil War took place. In 1949, the ROC government, ruled by the KMT, lost the civil war and retreated to Taiwan; at the same time, the CCP triumphantly took control of the Chinese mainland and founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC). However, both the ROC and PRC governments still claimed de jure sovereignty over all Chinese territories, including Taiwan and the mainland, despite the former’s de facto adminis-trative control being limited to Taiwan and the latter’s to mainland China. Both sides insisted on being recognized as the legitimate government of China, a situation that evolved into an international diplomatic competition to represent China. Consequently, a pact allowing only one government, either the ROC or the PRC, to represent China internationally not only informed the two governments’ foreign policies but also caused other countries to establish diplomatic relations with either the ROC or the Table 1. A Dualist Power Analysis Covering Three Discussions of Structural Power Phenomena Power analysis Agent’s Power couched in Governance Effects

including composing structural power phenomena Structural power

Indirect institutional Impersonally

phenomena

effects Unintended effects empowering effects resulting from

Power effects Agent’s power Agent’s power Governance’s arrangements Starting point A relational concept A dispositional A positional concept

concept

Analytic point Agent Agent Governance mechanism

Ability to influence Diffusion from an Governance’s Power resources agenda setting agent’s hegemony systematic

PRC. Since then, a One-China vision emerged, subsequently moving Cross-Strait relations into a “stage of a vague legal nature—neither international, nor domestic.”21

This One-China vision has been consistently followed by the PRC government despite several attempts at adjustments from the ROC side, such as creating “Two-Chinas” or “One-China, One-Taiwan,” beginning in the 1990s. The PRC’s adherence to One-China further evolved into the political formula of the OCP, indicating Taiwan is an inalienable part of the PRC.22 Most agents, therefore, referred to this OCP to shape their diplomatic relations with the PRC and ROC. Accordingly, different under-standings of One-China existed, resulting in different One-China policies upheld by various institutions. As a result, the Taiwan issue remained ambiguous, as did the tangled relations resulting from different understandings of One-China and the evolution of multiple One-China policies. During the process of PRC’s integration with the global community, four periods define the advances of the China vision and the One-China policies.

Battle for Chinese Representation in the United Nations

Since the establishment of the PRC in 1949, attempts by the Soviet Union alliance to replace the ROC with the PRC in the United Nations (UN) were consistently blocked by the United States (U.S.) alliance until 1971. At that time, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2758, through which the PRC succeeded the ROC. As a result, the PRC government was recognized as “the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations,” and the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek were expelled “from the place which they unlawfully occup[ied] at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.”23This UN Resolution was broadly considered to be the UN One-China policy—part of the UN standards—that applied to all UN bodies’ membership chapters. In the UN standards, the PRC replaced the ROC and was recognized as the only legal government to represent China, including Taiwan.24 Most other non-UN-related global institutions also followed the UN standards and questioned the ROC’s qualification as a legal state, accordingly downgrading the ROC’s status or disqualifying its representatives.25

Rapprochement with the United States

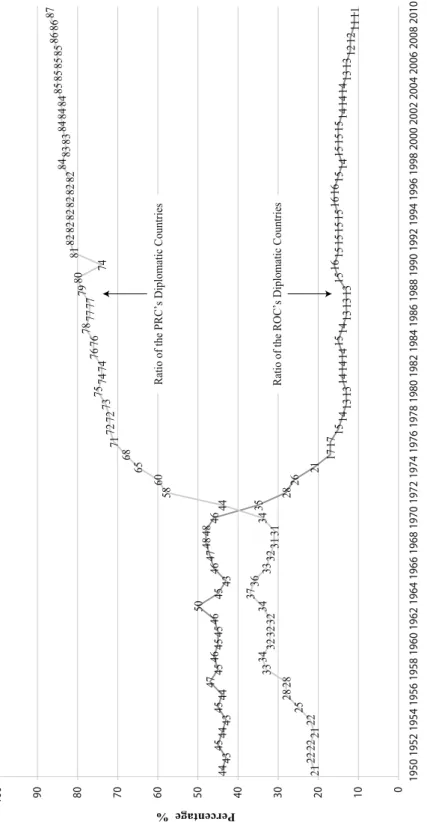

Following the ROC’s loss of a seat in the UN in 1971, increasingly more countries terminated their diplomatic relations with Taipei (see Figure 2) and established new ties with the PRC based on different versions of One-China policies that appeared in their communiqués.26Among these, starting from 1972, the PRC’s rapprochement with the United States—the main ally and supporter of Taiwan after the Maoist Revolution—adjusted America’s One-China policy and systematically reconstructed the knowledge system of One-China.

Three key documents embody the U.S. interpretation of One-China that informs Washington’s One-China policy: the Shanghai Communiqué of 1972, the Normalization Communiqué of 1979, and the August 17 Communiqué (on arms sales) of 1982.27 These documents include six important points: First, the U.S. One-China policy was initially meant to help settle or resolve Taiwan’s status; second, the United States emphasized the process of peaceful resolution rather than the outcome (unification or independence) of Taiwan’s future; third, the United States only “acknowledged”

Figure 2.

The Relationship between the ROC’s Diplomatic Countries and the PRC’s Diplomatic Countries (1950–2010)

Source

the One-China vision on both sides of the Taiwan Strait; fourth, the United States did not “recognize” the PRC’s sovereignty over Taiwan; fifth, the United States did not recognize Taiwan as a sovereign country either; and finally, the United States considered Taiwan’s sovereign status to be undetermined. Although influenced by the PRC’s OCP, the U.S. One-China policy persisted in its different interpretation of One-China, resulting in the formation of America’s Taiwan Relations Act (TRA). Some scholars therefore highlight the U.S. One-China policy together with the TRA as the most renowned examples in which an agency’s different diplomatic interpretation of One-China has been institutionalized.28

The End of the Cold War and the Tiananmen Crackdown

Both the end of the Cold War and the Tiananmen crackdown in the late 1980s cultivated the international soil for a reconsideration of the PRC’s essentially authoritarian regime, consequently contributing to China’s slowed integration process with the outside world. However, also beginning in the late 1980s, Taiwan’s democratization proposed a new basis for the ROC’s legitimacy, which was rooted in Taiwan and altered the dynamics of the One-China competition.

As a result, a new voice arose to push for changes in the One-China vision.29 Not only did former Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui (1988-2000) re-characterize Cross-Strait relations as “special state-to-state ties” in 1999, followed by former President Chen Shui-bian’s (2000-2008) “one country on each side” of the Strait in 2002, but in the 2000s several U.S. scholars and Congressmen, such as Wolfowitz,30 Kristol,31and Andrew and Chabot,32also joined the debate by critically questioning the U.S. One-China policy in a strong defense of democracy in Taiwan. All these moves were perceived by Beijing as promoting Taiwan independence, causing an Anti-Secession Law to be passed by the Chinese government in March 2005, the first time China’s OCP was officially upheld by a law. Article 2 of the Anti-Secession Law states that “[t]here is only one China in the world. Both the mainland and Taiwan belong to one China…. The state shall never allow the ‘Taiwan independence’ secessionist forces to make Taiwan secede from China under any name or by any means.”33As Beijing’s long-standing OCP was codified by formal legislative action— together with its previous two white papers, the Taiwan Question and Reunification of China in 1993 and the One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue in 2000—the PRC’s policy version of the OCP was ultimately articulated literally.

The 2008 Olympic Games and Financial Crisis

However, to some extent, global attention shifted from China’s hesitancy in political reform to its rapid economic growth, reinvigorating Chinese integration into the world. Holding the 2008 Olympics Games in Beijing was a milestone in the recovery of China’s reputation, with the enhancement being unexpectedly prolonged by the financial crisis later the same year. Thus, a more integrated China with more of a stake in international governance leveraged its stronger bargaining power to influence Taiwan’s China policy.

In 2008, Taipei, confronting a more difficult economic and political environment, revived its previous One-China policy—the 1992 Consensus34—to make Taiwan compatible with a different international structure that admitted, even urged, China’s

deeper participation in global political and financial governance. Despite several remaining disputes concerning the legitimacy of the 1992 Consensus in Taipei’s politics,35 the Consensus, presented as the KMT’s interpretation of One-China,36 was created to protect the ROC Constitution,37which also rested on the underlying hypothesis of “One-China.” As a result, the 1992 Consensus agrees with the current Taiwanese government’s vision of One-China, concluding that “both sides recognized that there is only one China but they are entitled to have different verbal interpretations of its meaning.”38 From the ROC’s perspective, the 1992 Consensus agrees on the One-China vision but disagrees with what China refers to, affirming Taipei’s ROC instead of Beijing’s PRC. That is, “One China with different interpretations,” as expressed by Taiwan’s current One-China policy.

To sum up, along with the PRC’s integration process, the One-China vision has gradually concerned most agencies of international governance, all of which have their own One-China policies in accordance with their different understandings. Despite the PRC’s rigid and unequivocal OCP, these agencies’ One-China policies have continued to be vague on the sensitive question of One-China. At the same time, however, their ambiguous approach to interpreting One-China has allowed for transformation of their One-China policies to align with the PRC’s rising power and favorable governance effects on structures, especially after 2008.

Power Analysis: Beijing’s Favorable Governance Effects

on China’s Rising Power and the Promotion of the OCP

Since 2008, issues arising from the global financial crisis have gradually changed the fundamental international structures. As Western hegemony continues its decline due to sovereign debt and credit problems, the leadership in Beijing grows more confident in dealing with the global financial turmoil at home, and a rising China is further expected to play a more important role in building new financial governance mechanisms globally.39 These new frameworks conducive to China’s increasing influence have systematically pulled international agencies’ One-China policies towards alignment with the PRC’s OCP. Thus, these favorable governance effects on China’s rise have created more structures for the world to learn about the Taiwan issue. These structures have further secured Taiwan’s China and foreign policies still consistent with the One-China vision since 2008. A dyad of concepts of power analysis covering three discussions of structural power phenomena from Stefano’s idea, mentioned earlier, can explain this evolution.

China’s Indirect Institutional Power for Structures and the OCP

One explanation of structural power phenomena in the IR debates affirms that a state must either improve its relevant quantitative power resources or change its agenda qualitatively to redefine relevant power resources and establish a favorable international structure. China has realized increasing power, especially through the post-2008 financial institution-building process.

Indeed, China has the leading seat of voting power in the newly established regional financial governance architecture. After the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis, the countries of East Asia shared a common need to promote regional financial

cooperation in addressing their financial problems. In May 2000, the Finance Ministers’ Meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Plus Three (ASEAN+3 or APT)40announced the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI),41which allowed the multilateral Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) to assist in averting financial crises. In February 2009, after years of conversation, finance ministers from APT countries agreed to establish a US$120 billion emergency fund. Establishing this fund was a huge step in building the AMF, to which both China42and Japan contributed 32 percent and South Korea contributed 16 percent, with the remaining 20 percent being picked up by the 10 members of ASEAN.

This arrangement indicates how far China has come since the beginning of its charm offensive during the Asian crisis a decade earlier. China’s rise and consequent eclipse of Japanese influence on regional financial cooperation were clearly on display, and the United States was not involved. Compared to the other regional institutions China had already joined, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), China’s presence in the AMF arrangement—as well as its voting weight as a ratio of its contribution relative to that of other powers, especially the US and Japan—has increased from under half to near parity.

The same story of China also appears in global financial mechanisms, especially in the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In the WB, after its former President Robert Zoellick appointed in 2008 the first Chinese economist, Justin Yifu Lin, as the senior vice president and chief economist, the Development Committee of the WB further approved the voting power reform plan in April 2010, again recognizing China’s rising economic power by increased its voting power from nearly three percent to more than four percent (4.42 percent). This move promoted China from the sixth-largest shareholder to the third-largest, behind only the United States (15.85 percent) and Japan (6.84 percent).

Similar developments also occurred in the IMF. In November 2010, the IMF approved a historic reform proposal to boost the voting power of large emerging economies, elevating China to the fund’s third spot behind the United States and Japan. According to the proposal, China’s quota share in the IMF rose from the previous 3.72 percent to 6.39 percent, with its voting rights increasing from 3.65 percent to 6.07 percent. This reform also enabled China to be represented on the IMF’s 24-member executive board, which previously had only been occupied by such developed countries as the United States, Japan, Britain, France, and Germany.43 In July 2011, in line with China’s increasing influence in the fund, the IMF for the first time appointed a deputy managing director from China. This economist, Zhu Min, was the first Chinese person to sit on the IMF’s board. Along with the previous appointment of Justin Yifu Lin to the WB, these positions not only reflected recognition of China’s growing economic power in the world but also established a trend of promoting Chinese voices to the highest echelons of the Bretton Woods institutions, which had been dominated by the Western hemisphere and underpinned the global economic and financial order since the end of World War II. This trend is also institutionalized by recent reform projects of the Bretton Woods institutions that seek to include more voices from developing countries, especially China, ensuring promotion of China’s institutional power resources will continue.

China’s stronger economic power and higher international position set strong precedents by improving its voting weight and giving China stronger institutional power in regional and global financial governance. In the regional financial governance

structures in East Asia, the ADB, established in 1966, used to be the only regional monetary institution. A traditional formulation of the ADB still allows Taiwan to retain its membership, partly due to strong support from the United States,44under the compromise name of “Taipei, China.” However, Taiwan never received new loans from the Bank after losing its UN seat to the PRC in 1971.45These arrangements still align with the PRC’s One-China vision, in which Taiwan is subject to China and in which China ideally enjoys the sole privilege of loaning to “its province of Taiwan.” In addition, a newly developing financial institution of the AMF demonstrates a scenario that allows even less room for Taiwan’s participation.

In the spirit of the CMI, the AMF essentially operates along the lines of the regional structure of the APT, which increasingly has been a major platform for discussions of regional governance projects.46Given that China is an influential member in the APT structure in terms of its growing capital size, Taiwan is not allowed to join the APT because of the prerequisite of sovereignty for membership, nor is Taiwan allowed to join the AMF, which is based on the APT structure. This architecture clarifies the APT’s One-China policy, which has been absorbed in the new Asian financial governance projects,47especially the AMF.

On the other hand, in the global economic and financial realm, both the WB and IMF consistently uphold the UN standards, although U.S. power was behind these two Washington-based groups when they protected Taiwan’s membership until 1980, almost a decade after Taiwan was expelled from the UN.48Being continuingly subject to the umbrella of the UN standards, influenced by China’s stronger voting power and higher administrative positions, both the WB and IMF show no signs of adjusting their One-China policies that favor the PRC. All these developments reveal that emerging international structures are being indirectly formed by China’s increasing power. These structures relegate Taiwan’s sovereign status as subject to China so unilaterally and influentially that other international governance institutions take for granted the knowledge sources from Beijing.

China’s Non-Intentional Power for Structures and the OCP

Non-intentional power refers to a state’s dispositional property of diffuse global resources that non-intentionally or unconsciously contribute to the function of international structures. In the case of China’s increasing influence on the promotion of the OCP, an understanding of China’s accelerated international trade process and security regime formulation is needed to analyze how it advances China’s non-intentional power and the application of the OCP in international structures.

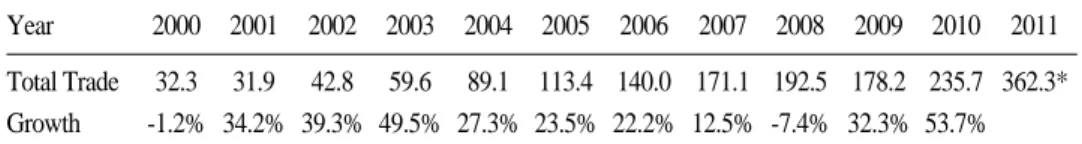

As noted previously, the APT is becoming the main infrastructure for many regional governance projects, among which China’s establishment of a free-trade agreement (FTA) with ASEAN illustrates how deeply this region has come to depend on China. Negotiated since November 2001, the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA) has been fully operative since 2010. In fact, trade between China and ASEAN has risen at a dramatic pace since 2000, increasing nearly eleven times from 2000 to 2011, as indicated in Table 2, which also shows the growing economic interdependence between China and ASEAN. Table 3 indicates that the share of total ASEAN trade with China has grown from 2.1 percent in 1993 to 11.6 percent in 2009, making China the largest trading partner of ASEAN—beyond the European Union (EU; 11.2 percent), Japan (10.5 percent), and the United States (9.7 percent). In addition, total

China-ASEAN trade is expected to continue to grow with the full operation of CAFTA.

Shifting attention from the CAFTA region to the entire world, China’s involve-ment in these FTAs indicates that its interests lie more with local geographic con-cerns. Table 4 shows China’s FTA networks, including 10 signed agreements and nine proposed projects. Of the 19 networks, however, more than half of them are located in the Asian Pacific or South Asia regions, both of which are areas geo-graphically related to China’s national security. In this regard, the development of closer trade relationships introduces the issue of security.

Through years of reform and opening-up policies, China realized that its national interests have been increasingly well-incubated by participating in international gover-nance and institutionalizing the rules of global institutions. In addition, the health of China’s relationship with boundary countries gives China an opportunity not only to play a more important role in the game ruled by the traditional U.S.-Japan alliance but Table 2. China-ASEAN Total Trade during 2000-2011 (in US $ billions)

Year 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Total Trade 32.3 31.9 42.8 59.6 89.1 113.4 140.0 171.1 192.5 178.2 235.7 362.3* Growth -1.2% 34.2% 39.3% 49.5% 27.3% 23.5% 22.2% 12.5% -7.4% 32.3% 53.7% * Trade size has risen more than eleven times from 2000 to 2011

Source of Data: ASEAN Trade Database, various issues.

Table 3. Share of ASEAN Trade with Selected Trade Partner Countries/Regions

also to institutionalize its own rules and interests aggressively through the economic integration process, in FTAs in particular.

The gradual institutionalization of China’s economic cooperation with countries in the Asian Pacific and South Asia indicates the convergence of China’s national interests with those of other nations and the dilution of U.S. strategic unilateralism in Asia. Especially as the United States and EU encounter difficulty in dealing with the current economic and financial turmoil, Asian countries are looking for regional approaches to relief. Therefore, the mutual interests of China and its neighbors, initially built on trade benefits, have been expanded to security concerns that draw more attention to Asian regional cooperation and integration to stabilize the currently Western-based financial crisis. Recent developments include China’s call for an expansion of economic cooperation and dialogue on other regional security issues by agreeing to work together with its neighbors, Japan in particular, to establish an “East Asian Community” that will bring about the birth of the first regional security council.49

As Cheow indicates, the rise of China’s influence and power in East Asia has reshaped this region into a new security environment that resembles the ancient Chinese tributary system effective in China’s Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties.50 This tributary system is a hierarchical arrangement in which China considers itself the central heart in the region and provides tangible favors to its sur-Table 4. The Free Trade Agreements of China

Country FTA Partner Region Status

China ASEAN Asian Pacific Signed

New Zealand Asian Pacific Signed

Singapore Asian Pacific Signed

Hong Kong Asian Pacific Signed

Macau Asian Pacific Signed

Taiwan Asian Pacific Signed

Australia Asian Pacific In negotiation

Korea Asian Pacific In consideration

Japan-Korea Asian Pacific In consideration

Pakistan South Asia Signed

India South Asia In consideration

Gulf Cooperation Council West Asia In negotiation

Chile America Signed

Peru America Signed

Costa Rica America Signed

Iceland Europe In negotiation

Norway Europe In negotiation

Switzerland Europe In consideration

Southern African Customs Union Africa In negotiation Source of Data: China FTA Network.

rounding tributary states, which in turn pay their intangible respect and goodwill to the Chinese emperor. Examples of the regional FTA networks and security regimes support Cheow’s interpretation of China’s tributary system.

The establishment of CAFTA in Southeast Asia is now associated with the Shanghai Co-operation Organization in China’s northwest; its FTA relationship with such southwest neighbors as Pakistan and India; its intention to set up a trilateral FTA with its two northeast neighbors, Japan and Korea; and its interest in FTAs with two western Pacific powers, Australia and New Zealand. Once these regional structures are institutionalized, with favorable agreements reached, the Chinese tributary system will be formalized. These Sino-oriented cooperation and security regimes may also serve as a collective constraint on potential “trouble-makers.” Taiwan, in China’s view, is one of these targets.51 Therefore, considering China’s growing economic and diplomatic power gained from global attraction to China’s domestic market, its FTA networks with regional markets, its importance in key regional security regimes, and its re-emerging Chinese tributary system, most global agencies stay away from China’s “internal affairs,” the Taiwan issue in particular. While Taipei shows interest in any FTA proposals or blocs, most states show indifference towards or hesitate to consider the applications, except China52 and the nations recognizing Taipei,53 largely because FTA relationships involve affirmations of Chinese sovereignty.

For example, as a precedent for other FTAs, the recent Taiwan-Singapore FTA talks based on Singapore’s interpretation of One-China—which labels Taiwan as a World Trade Organization (WTO) member rather than a nation—still arouse Beijing’s concern. An official in the Singapore Trade Office in Taipei, addressing this issue in an interview in October 2012, said, “the right to trade is repeatedly learned regarding China’s sovereignty, even though we also learn that the WTO’s Article 24 enables any WTO member to conclude FTAs with other members.” Local media believed the Taiwan-Singapore FTA was in line with China’s core interests, and both Taipei and Singapore must have briefed Beijing concerning this alignment.54As a result, this Sino-oriented environment unintentionally causes Beijing’s OCP to be acknowledged as an “international (manipulated) consensus” in most global and regional economic and security interactions, even though different versions of One-China policies still exist in diplomatic statements. In this structure, Taiwan’s proposals for more interna-tional space, including building and joining FTAs as well as other global supports, are categorized as trouble making and are perceived to decrease global and regional stability. This stance also reflects Lukes’ three-dimensional view of power,55 in which China takes control of learning channels and other agencies are unconsciously socialized into accepting, believing, and even supporting Beijing’s hegemonic OCP.

Meanwhile, the recent row over China’s increasingly assertive behavior in its claim to the South China Sea has alarmed several ASEAN countries and tarnished the image of China’s peaceful rise. Taiwan, though stationing garrisons on two major islands in the South China Sea, still has difficulty in taking advantage of these territorial disputes to promote Taiwan’s status and participation equal to other stakeholders in projects to help resolve the disputes. In general, two approaches have been discussed regarding the South China Sea issue: the ASEAN-proposed multilateral forum that would use the existing regional institutions and the Chinese-preferred bilateral nego-tiations among involved countries. Some parties have also suggested inviting the US military back into the ASEAN region for balance against China.56 Among these, Taiwan has less room to argue its “rights” in the territorial issue because most

regional institutions and stakeholders still consistently align with the PRC’s OCP. Ironically, the improved Cross-Strait ties appear to have “convinced” and “educated” all countries concerned, including the United States, that Taipei is accepting the OCP and collaborating with Beijing in asserting and defending “Chinese interests” in the South China Sea.57These interactions constitute “updated” knowledge of Taiwan’s status in international governance that systematically limits Taiwan’s international space. For example, in the recent dispute between Taipei and Manila over the killing of a Taiwanese fisherman in the South China Sea by a Filipino coast guard vessel in May 2013, the Philippine government was suggested by its One-China policy not to convey Manila’s apology to Taipei, but to Beijing, as well as to the people of Taiwan, symbolizing Taiwan’s limited international space.

Governance’s Impersonally Empowering Effects on Structures and the OCP Impersonally empowering effects, the last of the three structural power phenomena, are characterized as a byproduct of governance effects, beginning in international governance arrangements and giving certain actors unique positions or roles to maintain the function of governance effectively. This positional approach to structural power phenomena argues that a globally established political order tends to normalize some powerful countries’ arbitrariness through knowledge systems that discipline thought processes and instruct action-choice lists. Given that the inherent international order benefits some great powers, it is important to address how China, as an influential power, manipulates conscious governance bias to affect outcomes in ways conducive to its OCP—beginning with China’s great power acting on the UN Security Council and concluding with its involvement in the Kissinger model, the G20 governance model, and the potential G2 governance model.

The UN Security Council is designed to maintain the balance of the great powers of World War II and has endorsed the formation of the current international power structure. According to Article 27 of the UN Charter, five countries (Permanent-5), including China, enjoy permanent membership on the UN Security Council, which grants members of the Permanent-5 veto power to prevent the adoption of any sub-stantive draft resolution from the Council. As the Chinese representative since its succession to the ROC’s seat in the UN in 1971, the PRC has cast its veto only six times, making it the least frequent user of the veto among the Permanent-5.58However, two of its vetoes were used to condemn the target countries’ diplomatic relationships with Taiwan, including a veto in 1997 against Guatemala and another in 1999 against Macedonia. These instances point to the PRC’s resolve to use its veto power to safeguard its OCP.

In fact, in the 1970s, China’s great power role compelled it to join in a strategic triangular game of great power balance among Washington, Beijing, and Moscow. This structure has been called the Kissinger Model, in which China was appointed to play a strategic role in the great power concert, even though it always disavowed its great power position and instead claimed to be from the Third World camp in opposition to the other two superpowers. However, once the strategic game was launched in the great power concert, no members, including China, could “be wished away: whether there is peace or war, security or insecurity in the world political system as a whole, is determined more by the leading groups within these powers than it is by any others.”59As a result, moves towards negotiation and cooperation among the

great powers were also expected to serve the interests of the great powers them-selves instead of the interests of the global community as a whole. Thus, little room existed for the topics of democracy and humanitarian principles. As a consequence of the Kissinger Model during the 1970s, the dynamics of the great power concert induced the United States to abandon its anti-communist ally, the ROC, and to recognize a communist enemy, the PRC. Therefore, the PRC’s One-China vision was considered favorably, with little concern for friendship and justice in its structure.

Furthermore, this principle of balance of power and its byproduct of a concert of powers introduced some international governance mechanisms managed by the G-groups, especially the G20 and the G2. Established in 1999, the G20, comprised of 20 major economies, has become the main economic council, managing about 85 percent of the global economy. China is also included in the group and is always expected to have a wider role in the governance structure, especially when tackling

Figure 3. Power Analysis of China’s Rising Power, Favorable Governance Effects, and the Promotion of the OCP in International Structures

the current financial crisis, because it has the second largest economy with growing foreign exchange surpluses.60 Meanwhile, another governance structure, the G2, considered a special relationship between today’s two largest powers, the United States and China, has been proposed according to great power concert theory. Despite rare governmental statements released from officials of both powers, the proposal of G2 has arisen primarily in US academic circles, especially after 2008. It has been particularly advocated by three former US national security advisors, Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Brent Scowcroft;61 an influential U.S. historian, Niall Ferguson;62 and two former WB economists, Robert Zoellick and Justin Yifu Lin.63

These academics’ opinions indicate that the stability of global affairs requires a cooperative partnership between the two great powers; therefore, without a reliable G2 structure, the efforts of all other international governance mechanisms, including the UN, IMF, WB, WTO, and G20, will not be productive.64Issues subordinate to the promotion of a better G2 structure will be handled only to satisfy the two great powers’ own interests so as to safeguard the larger interests of their relations: a Table 5. Power Analysis and Related Concepts to the OCP

Concepts of power analysis of structural power phenomena:

China’s Indirect China’s Governance’s

Institutional Power Non-Intentional Impersonally

for Structures Power for Structures Empowering Effects

on Structures

Resources of China’s stronger voting The global attraction China’s great power

power/governance power and higher of China’s domestic role in the

used by China administrative positions market, FTA networks, great-power-governance

in the financial importance in security structure that follows

institution-building regimes, and the the balance-of-power

process re-emerging Chinese doctrine

tributary system

Advances of the The UN standards are The Sino-oriented Beijing’s arbitrariness

OCP promoted to safeguard environment in its OCP for the

the adoption of the unintentionally causes Taiwan issue is made

OCP in international the OCP to be acceptable by the

interactions acknowledged as an great-power-governance

international consensus structure

in most international interactions

Impacts on Most governance Taiwan’s proposals for The Taiwan issue is

Taiwan’s status institutions take the more international space expected to be resolved

knowledge sources of are categorized as by the great power

the OCP for granted trouble-making that will concert more in

regarding Taiwan’s essentially decrease accordance with the

sovereign status as global and regional promotion of special

subject to China stability interests of the great

powers than those of Taiwan

structure of global stability. In this new Sino-American power-sharing structure, China’s influence is encouraged to grow enough to satisfy both the Chinese and international governance while the U.S. authority keeps its influence large enough to ensure that China’s power is not misused.65

These governance effects urging China’s deeper participation in global affairs after 2008 also explain why China found it relatively easy to promote itself in the abovementioned governance mechanisms, like the AMF, IMF, WB, FTAs, and security networks, in comparison to the pre-2008 phenomena in which China’s rise was not quickly recognized.66The Taiwan issue, always one of China’s core interests and a main obstacle to U.S.-China relations, is expected to be resolved by this great power concert in accordance with the special interests of the great powers more than those of Taiwan. Following the balance-of-power doctrine, a tendency towards a great-power governance structure that functions in favor of the two great great-powers’ interests is expected while Beijing’s arbitrariness in its own OCP concerning the Taiwan issue is made acceptable by this structure.

Identifying these critical issues in the debate on power analysis creates an intel-lectual foundation for thinking about the social interactions between agencies and international governance mechanisms. The above two concepts of power resources and the concept of governance effects used by China to advance application of its OCP in international structures that ensure the shifting of Taiwan into the Chinese orbit are summarized again in Figure 3 and Table 5.

Conclusions: Reorienting Taiwan into the Chinese Orbit

By focusing on the dyadic concepts of power analysis, this theoretical survey facili-tates analysis of the social relationships between agencies and governance effects. The operation of structures lies in the social relationships of the agencies and in the governance norms resulting from these interactions. For agencies, although each is eager to build its own power capacity in the social relationships of structures, these interactions drive governance effects, such as norms and knowledge, on structures that privilege specific great powers. Thus, resources to pursue an agent’s increasing power are gained not only from its efforts but also from its favorable governance effects. These interactions consequently contribute to three structural power phenomena, including indirect institutional power and non-intentional power of an agent, as well as impersonally empowering effects couched within the governance environment.

This power analysis also shows that China’s power has been promoted in and through its favorable international governance mechanisms, especially after 2008. The three structural power phenomena further show that Taiwan’s status in international structures has been gradually patterned on China’s OCP in accordance with Beijing’s rising power and favorable governance effects. The influence of these phenomena on the advanced application of the OCP in the international structures determines the range and scope of Taiwan’s exercise of power, as well as its limited entry into international governance. As a result, Beijing’s friendly structures in promoting the OCP since 2008 have educated Taipei that Taiwan’s policies must not only serve the Taiwanese nationalist constituencies but also, more importantly, satisfy the mechanisms of international governance that privilege some specific great powers. During Taiwan’s 2012 presidential election, although Beijing and Washington did not publicly endorse

President Ma, it was an open secret that both China and the United States preferred Ma’s One-China approach (the 1992 Consensus) to Cross-Strait relations, even though the Consensus was domestically criticized for its lack of legitimacy and transparency. Today, as previously mentioned, both Taiwan’s DPP and KMT parties have even been reoriented to the work of interpreting “One-China” for Taiwan’s further admission to international governance, forcing it to fall within the Chinese orbit. This structural shift should be recognized as having been accelerated by the effects of both Beijing’s rising power and its favorable governance mechanisms since 2008, rather than being regarded as the effects of power competition between Taipei and Beijing.

This recognition further provides a number of avenues for future research. For example, although the results of this research suggest Beijing’s OCP has been advanced as China’s power continues to expand in and through its favorable interna-tional governance mechanisms, any conclusion and finding from this paper should be treated as only preliminary. In this paper, the discussion of China’s rise during its promotion of its OCP in international structures is limited to explaining only why and how China has been able to use its structural power resources since 2008 to reorient Taiwan towards accepting One-China. Thus, further research should investigate how Taiwan adjusts itself for this reorientation both internationally and domestically. In addition, it is possible that the international space that two OCP followers—Hong Kong and Macau—enjoy, such as FTAs and visa waiver programs, would be referred to in accommodating Taiwan in the international structures adhering to the OCP. Thus, any future research projects comparing different practices of the OCP would be beneficial.

As China’s OCP becomes the international consensus and reorients Taiwan into the Chinese orbit, another study for Taiwan from The Art of War is: “As water shapes its flow in accordance with the ground, so an army manages its victory in accordance with the situation of the enemy.”

Notes

1. See http://www.agile-news.com/news-1152261-The-media-said-one-country-two-or-Taiwan -to-promote-cross-strait-political-negotiations-signals.html.

2. Robert Sutter, “Why Taiwan’s Freedom of Action Continues to Erode,” PacNet, no. 30, May 26, 2011, http://csis.org/publication/pacnet-30-why-taiwans-freedom-action-continues -erode; Bruce Gilley, “Not So Dire Straits: How the Finlandization of Taiwan Benefits U.S. Security,” Foreign Affairs 89, no. 1 (2010): 44–60; Charles Glaser, “Will China’s Rise Lead to War? Why Realism Does Not Mean Pessimism,” Foreign Affairs 90, no. 2 (2011): 80–91; Daniel Blumenthal, “Rethinking U.S .Foreign Policy towards Taiwan,” Foreign Policy, March 2, 2011, http://shadow.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2011/03/02/ rethinking_us_foreign_policy_towards_taiwan; and Paul V. Kane, “To Save Our Economy, Ditch Taiwan,” The New York Times, November 10, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/ 2011/11/11/opinion/to-save-our-economy-ditch-taiwan.htm?_r=2.

3. Der-Yuan Wu, The International Construction and Function of “One China (with Different Interpretations)”: The Perspective of Institutionalism and Constructivism (Taipei: Institute of International Relations of National Chengchi University Press, 2009).

4. Here, according to Guzzini (1993), the concept of international governance refers to the processes of social interactions more than the roster of participants.

(2000),” February, 2000, http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2005-07/27/content_17613.htm. 6. Hans J. Morgenthau and Kenneth W. Thompson, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (New York, NY: Knopf, 1985); John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York, NY: Norton, 2001); Ashley Tellis et al., Measuring National Power in the Postindustrial Age: Analyst’s Handbook (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2000).

7. John Lewis Gaddis, “International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War,” Interna-tional Security 17, no. 3 (1992/93): 5–58; The End of the Cold War and InternaInterna-tional Relations Theory, eds. Richard Ned Lebow and Thomas Risse-Kappen (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1995); Controversies in International Theory: Realism and the Neoliberal Challenge, ed. Charles W. Kegley, Jr. (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1995).

8. Kenneth N.Waltz, Theory of International Politics (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1979), 74. 9. Stefano Guzzini, “Structural Power: The Limits of Neorealist Power Analysis,” International

Organization 47, no. 3 (1993): 443–78. 10. Ibid., 450. 11. Ibid., 474. 12. Ibid., 472. 13. Ibid., 471. 14. Ibid., 476.

15. Stefano Guzzini and Anna Leander, “Wendt’s Constructivism: A Relentless Quest for Synthesis,” in Constructivism and International Relations: Alexander Wendt and His Critics, eds. Stefano Guzzini and Anna Leander (London: Routledge, 2006), 81–82. 16. Stefano Guzzini, “The Concept of Power: A Constructivist Analysis,” Millennium—Journal

of International Studies 33, no. 3 (2005): 507–8.

17. Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Trans. A. Sheridan (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1995).

18. Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993).

19. Steven Lukes, Power: A Radical View, Second Edition (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

20. Guzzini, “The Concept of Power,” 516.

21. Pasha L. Hsieh, “The Taiwan Question and the One-China Policy: Legal Challenges with Renewed Momentum” (Research Collection School of Law, Paper 13, 2009) 61, http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/13.

22. Chinese Government’s Official Web Portal.

23. United Nations General Assembly, “Restoration of the Lawful Rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations,” Resolution 2758, Session 26: 2, October 25, 1971, http://www.undemocracy.com/A-RES-2758%28XXVI%29/page_1/rect_485,223_914,684. 24. Therefore, “Taiwan” or “ROC” does not appear as a member country in any UN-affiliated agencies. Whenever Taiwan is referred to in the agencies, the designation of “Taiwan, Province of China” is used.

25. First, in 1974, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) listed Taiwan as “Taiwan, Province of China” because ISO accepted the UN standards. Most countries, firms, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academic institutions adhered to the ISO guidelines. Second, in 1979, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) renamed the ROC’s Olympics Committee the “Chinese Taipei Olympics Committee,” thereby recognizing it only as a provincial body, and no longer allowed the use of the ROC’s national anthem and flag at the Olympic Games because the Olympic Charter allowed only independent states recognized by the international community to use their national flags, emblems, and anthems. Most sporting events referred to the IOC guidelines, which were then introduced to other international forums, events, and competitions. Third, the World Trade Organization

(WTO) accepted Taiwan’s application for membership as the government on behalf of “the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu” in 2002. This flexible application bypassed the issue of sovereignty because mostly the WTO still adhered to the UN standards but also allowed membership as a “customs territory.” However, “Chinese Taipei” is used very often when official documents within the WTO refer to the “the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu.”

26. According to Wu (The International Construction and Function of “One China (with Different Interpretations),” 157–58), there are three different versions of One-China policies appearing in the joint communiqués, including One-China with different interpretations, One-China without mentioning the Taiwan issue, and One-China with mentioning Taiwan as a part of China.

27. The concept of the U.S. One-China policy was not discussed in the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979. See Kan, 2011: 8.

28. Wei-Jen Hu, The Evolution of the U.S. One-China Policy from Nixon to Clinton (Taipei: Commercial Press Taiwan, 2011); Wu, The International Construction and Function. From Wu’s observation (pp. 131–58), the Canada-PRC Joint Communiqué in 1970, stressing that Canada “takes note of” Beijing’s One-China position and stating that Taiwan is part of the PRC, was the first “One-China with different interpretations” model. This communiqué successfully resolved a dilemma of recognizing Beijing diplomatically while maintaining a flexible relationship with Taipei. This Canadian model was then adopted by at least 30 countries, especially the United States (the most complete version), the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, the Netherlands, and Korea. 29. Shirley A. Kan, “China/Taiwan: Evolution of the ‘One China’ Policy—Key Statements

from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei.” (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, January 10, 2011), 1, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30341.pdf. 30. Paul Wolfowitz, “Remembering the Future,” The National Interest (Spring 2000): 35–45. 31. William Kristol, “Embrace Taiwan,” The Washington Post, December 4, 2001,

http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-480414.html.

32. Robert E. Andrew and Steve Chabot, “Two Congressmen Look at ‘One China,’” Heritage Foundation, February 6, 2004, http://www.heritage.org/research/lecture/two-congressmen -look-at-one-china.

33. Tenth National People’s Congress, “Full Text of Anti-Secession Law,” People’s Daily Online, March 14, 2005, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200503/14/eng20050314_ 176746.html.

34. The 1992 Consensus was reached in a meeting in Hong Kong, October 28–30, 1992, between Taipei’s Strait Exchange Foundation and Beijing’s Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait. See Kan, 2011: 45.

35. Taiwan’s main opposition party, the DPP, challenged the 1992 Consensus for being with no any legitimization process.

36. Ying-jeou Ma, “Taiwan’s Approach to Cross-Strait Relations,” Working Paper of the Aspen Institute, January 2003, 37, http://www.ciaonet.org/wps/may01/may01.pdf. 37. The ROC Constitution, drafted by the KMT, was adopted on December 25, 1946, when

the KMT government was still based in Mainland China. 38. Ma, “Taiwan’s Approach,” 30.

39. Robert C. Altman, “Globalization in Retreat: Further Geopolitical Consequences of the Financial Crisis,” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (July/Aug. 2009): 2–7.

40. In 1992, ASEAN consisted of a trade bloc agreement among ten countries, including Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Subsequently, the ASEAN members expanded this agreement to include three other East Asian countries—China, Japan, and South Korea—resulting in ASEAN Plus Three (APT).

Chiang Mai, Thailand, May 6, 2000, http://citrus.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/projects/ASEAN/ASEAN+3/ +3AS20000506E%20Joint%20Statement%202nd%20AFM+3.htm.

42. US$34.2 billion came from the Chinese mainland and US$4.2 billion from Hong Kong, China.

43. The IMF reform expanded its 24-member executive board’s membership from five coun-tries—the United States, Japan, Britain, France, and Germany—to 10 countries with the addition of China, India, Brazil, Italy, and Russia.

44. The ABD has a similarly weighted voting system in which both the United States and Japan hold the largest proportion of shares at 12.756 percent, each dominating China’s 6.429 percent.

45. Although Taiwan has received no new loans since 1971, when the PRC took over the Chinese seat at the UN, the ABD did not grant the PRC membership until 1986, “purportedly due to the increased financial burden that would entail on Bank resources, but also partly due to strong [U.S.] congressional opposition to such a move,” according to Robert Wihtol, The Asian Development Bank and Rural Development: Policy and Practice (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), 102.

46 Phillip Y. Lipscy, “Japan’s Asian Monetary Fund Proposal,” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs 3, no. 1 (2003): 102.

47. Four primary duties, including monitoring capital flows, regional surveillance, swap networks, and training personnel, are conducted by the CMI-related projects and coordinated by the APT members.

48. Taiwan initially joined the WB and IMF as “China” in Washington, D.C. on December 18, 1956, and had a share representing all of China prior to the PRC’s joining and taking both seats in April 1980, just one year after the United States established diplomatic relations with the PRC. Since Taiwan was ejected, it has not applied to return.

49. David M. Lampton, The Three Faces of Chinese Power: Might, Money, and Minds (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008), 110–111.

50. Eric Teo Chu Cheow, “Asian Security and the Reemergence of China’s Tributary System,” China Brief 4, no. 18 (September 2004), http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache= 1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=3676.

51. Sheng Lijun, “China-ASEAN Free Trade Area: Origins, Developments and Strategic Motivations,” ISEAS Working Paper: International Politics & Security Issues Series 1, 2003, http://www.iseas.edu.sg/ipsi12003.pdf; Kevin G. Cai, “The China–ASEAN Free Trade Agreement and Taiwan,” Journal of Contemporary China 14, no. 45 (2005): 585–97.

52. Taiwan and China have signed a quasi-FTA pact, the ECFA, which is similar to the FTA pacts between Hong Kong and China and between Macau and China. The pact subjects Taiwan to the PRC’s One-China vision.

53. Except China, so far only four FTAs include Taiwan along with five of its diplomatic allies: Panama, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

54. Ernest Z. Bower and Charles Freeman, “Singapore’s Tightrope Walk on Taiwan,” ABS-CBN News, August 19, 2010, http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/insights/08/18/10/singapores -tightrope-walk-taiwan; Ralph Jennings, “How Taiwan is Benefiting Economically from Recent Thaw in Ties with China,” The Christian Science Monitor, May 23, 2011, http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2011/0523/How-Taiwan-is-benefiting -economically-from-recent-thaw-in-ties-with-China.

55. Lukes, Power: A Radical View.

56. Evelyn Goh, “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies,” International Security 32, no. 3 (2007/08): 113–57.

57. See http://www.chinapost.com.tw/editorial/taiwan-issues/2011/11/24/323797/p2/Row-over .htm.

times, the UK 32 times, France 18 times, and China seven times (once by the ROC and six times by the PRC).

59. Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1977), 298–99.

60. Geoffrey Garrett, “G2 in G20: China, the United States and the World after the Global Financial Crisis,” Global Policy 1, no. 1 (2010): 29–30.

61. Edward Wong, “Former Carter Adviser Calls for a ‘G-2’ between US and China,” The New York Times, January 2, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/12/world/asia/12iht -beijing.3.19283773.html.

62. Niall Ferguson, “Niall Ferguson Says U.S.-China Cooperation is Critical to Global Economic Health,” The Washington Post, November 17, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/ wp-dyn/content/article/2008/11/16/AR2008111601736.html.

63. Robert B. Zoellick and Justin Yifu Lin, “Recovery: A Job for China and the US,” The Washington Post, March 6, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/ 2009/03/05/AR2009030502887.html.

64. Garrett, “G2 in G20,” 30–31.

65. Hugh White, The China Choice: Why America Should Share Power (Melbourne: Black, 2012).

66. Ngaire Woods, “Global Governance after the Financial Crisis: A New Multilateralism or the Last Gasp of the Great Powers?” Global Policy 1, no. 1 (2010): 51.

Notes on Contributor

Scott Y. Lin is an assistant research fellow and assistant professor at the Institute of Interna-tional Relations of NaInterna-tional Chengchi University at Taipei, Taiwan. He has received his Ph.D. from Rutgers University (USA) in 2012 and published two academic books and several journal articles, mostly regarding the impacts of globalization on Taiwan and China. He is currently working on his research project, which explores the dynamics of globalization that have integrated China into the global community and stimulated a transforming concept of sovereignty in Taiwan, causing changes in the Cross-Strait relations.