National Chiao Tung University

Institute of Social Research and Cultural

Studies

Thesis

Imagining the Prostitute:

A Genealogy of Cinematic Representations of Power

Student: Nicholas Barkdull

Advisor: Prof. Joyce C.H. Liu

Imagining the Prostitute:

A Genealogy of Cinematic Representations of Power

研究生:白洛克 Student: Nicholas Barkdull

指導教授:劉紀蕙 Advisor: Joyce C.H. Liu

國 立 交 通 大 學

社 會 與 文 化 研 究 所

碩 士 論 文

A Thesis

Submitted to the Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies College of Humanity and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master

in

Social Research and Cultural Studies June 2014

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

Imagining the Prostitute:

A Genealogy of Cinematic Representationsof Power

Student: Nicholas Barkdull Advisor: Prof. Joyce C.H. Liu

Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

This research will attempt to find Taiwanese cinematic uses of the ‘sex worker,’ and the implications contained within those uses in order to offer a nuanced alternative to common dichotomies which render discussions of the sex worker reductive. I will offer this alternative by tracing back cultural symbols which are rooted in history and society. Contemporary (mainly post-2000) Taiwanese cinema will be used as a frame for a genealogical analysis of these images of the sex worker. This genealogy will find threads connecting a complex network of ever-changing power relationships surrounding sex work through the metaphors of sex worker roles within films, which tell of a latticework of power that takes place along the axes of history, culture, and political economics.

Acknowledgements

I owe my deepest gratitude to many individuals, but first and foremost my advisor, Professor Joyce C.H. Liu, who carefully read every draft of this thesis and worked with me closely every step of the way. The amount of effort she put into guiding me is staggering, and this thesis would certainly not have been possible without her help.

I would also like to thank my committee members. Thank you to Professor Earl Jackson, for helping me form my initial ideas and for working with me throughout the entire process. Thank you to Professor Shie Shizong for the wealth of useful and honest suggestions during my proposal.

In addition, I would like to thank Professor Ding Naifei for meeting with me and sharing her views in the initial stage of this process. I would like to thank Professor Chu Yuan-Horng for providing me with a wealth of ethnographical research and meeting with me to discuss it. I would like to thank Matthew Borgard for his help in editing. Finally, my thanks goes to National Chiao-Tung University for allowing me the resources and environment to study as well as the scholarship that allowed me to complete this process.

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT ... i

Acknowledgements ...ii

Table of Contents ... ..iii

Introduction: A New Way of Looking ... 1

The Problem ... 1

Background ... 2

The Feminist Schism ... 2

The Violent Male Gaze ... 4

Methodology ... 6

Structure of the Research ... 10

Chapter 2: Commodity and Power ... 17

A Time of Freedom: The Sex Worker as Literal Commodity Object ... 20

A Time of Love: A Lack of Certainty in Cold War Taiwan ... 27

A Time of Youth: A Complex Subjectivity Requiring Complex Resistances ... 34

Conclusions: A Semiosis Overlaid on the Topology of Taiwan ... 44

-Chapter 3: The Brothel Prostitutes of Monga and Days Looking at the Sea: Fundamental Shifts in Power Through Modernity ... 49

Echoing the Past, Contextualizing the Future ... 51

Days Looking at the Sea: The Powers of Adoption, Family Law, and Patrilineality... 53

Monga: Gangster Norms Coping with Femininity ... 64

Conclusions: Power Resistances Evolving with Society ... 77

-Chapter 4: Location on the Margins: Migrants and Sex Workers in The Fourth Portrait and Stilt ... 83

Migrant Wives and Imagined Borders ... 83

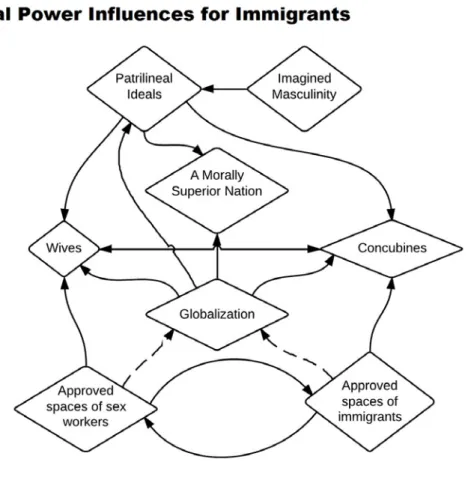

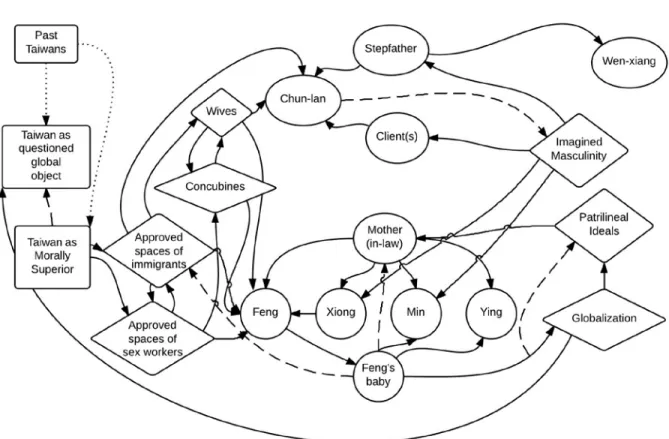

Concubines, Wives, Prostitutes ... 86

Migrant Chinese Brides: Mothering Across the Impassable Strait ... 89

MailOrder Brides from Vietnam: Commodities, Laws, and InLaws ... 102

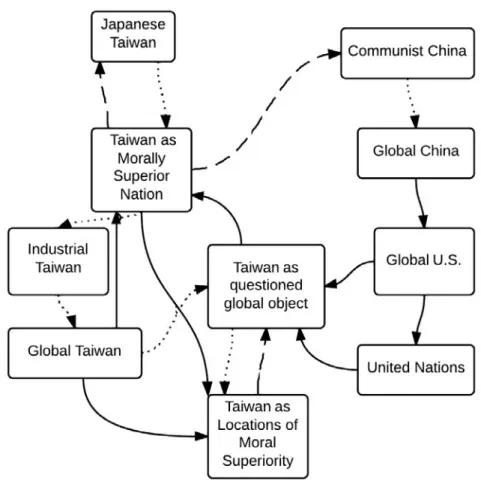

Conclusions: Taiwan as the Location of Legitimacy ... 114

Conclusion: Redefining the Grids, Redefining Power ... 119

Taking Back the Body ... 122

Shifting Centers of Power ... 124 -iii

What Can Be Concluded, and What Cannot ... 129

Appendix 1: Figures ... 130

Appendix 2: Films Analyzed in this Thesis ... 137

Bibliography ... 139

Chinese Sources: ... 139

English Sources: ... 139

Introduction: A New Way of Looking

The Problem

Taiwanese law currently defines penalties for sex work (according to the current law existing since the 1991, and especially after the presidency of Chen Shui-Bian starting in 2000, before which licensed prostitution existed in small numbers).1 Likewise, feminists, activists, and academics are locked in a battle either advocating the abolishment of prostitution or the

establishment of sex work as a legitimate form of work (or some slight variations, such as decriminalization). However, for all of these opinions there seems to be a lack of satisfactory definitions (many literally never define what sex work is), research (there is much speculation about sex workers but few interviews and ethnographies outside of government care facilities), and humanity (the sex worker becomes a concept in these debates, rather than a person). The first task of this research, therefore, is to briefly read between the lines of these sources for a

Taiwanese institutional answer to the question: “What is sex work?” Since these (law, academics, and activists) are the major cultural institutions that define the deviancy or legitimacy of sex workers, it is worthwhile to use their discussions to supplement the discussion of film sources.

The mirror on the other side of these institutions is cinema, which reacts to the former’s definitions of sex work and in turn redefines them. The representations by film are not simply a reflection of sexual deviance, but are instead a web of societal and historical influences that combine to send a message. The second question of this research is therefore: “How are sex workers represented in Taiwanese films, and why?” and the third question is “What are the 1

Hung (2009: 21-22) points out that licensed prostitution existed for around 40 years since the KMT left China, and that Chen began a campaign against the practice as mayor of Taipei in 1997. By that time there were only 128 licensed prostitutes in the city (page 35).

1

Chou (2007) points out that licensed prostitution may technically still exist, but the Taipei Licensed Prostitutes Management Act of 1973 drastically decreased the practice through conditions which were hard to fulfill, “(e.g. death of brothel owner results in the brothels' closure as brothel ownership and location is non-transferable),” and Chen’s 1997 actions put the nail in the coffin in Taipei.

- 1 -

implications of (all of) these definitions about Taiwanese society?” This last question is almost the same as asking “why?” in the first, but it is important because it follows the original question through to conclusion. It is the difference between knowing, for example, that prostitution is used in Chung Mong-Hong’s (鍾孟宏) The Fourth Portrait (第四張畫) to show the struggle of a migrant to properly take care of her child (answering “why?”) and asking what that means for borders and citizenship in Taiwan (answering “what are the implications?”).

Background

Originally, the first question of this thesis was, simply, “What is a sex worker?” It

quickly became obvious that this should be defined by Taiwanese sources, and the first examined were the law and academic sources. Through these institutions, a two-sided debate emerged between Taiwanese abolitionists of sex work and advocates of sex work as work.

The Feminist Schism

An essay by Yenlin Ku (顧燕翎) (2008) tells about her role in Taiwanese feminist activism and how she believes feminists can work with the state. She led the Awakening Foundation, a feminist group that emerged in the late 1980s and began the fight against

prostitution by first campaigning against child aboriginal prostitutes. She is thus one of the first modern “abolitionists,” and the others that have followed share similar roots.

Ku’s opposes of the advocates of sex work as work, not only in her position on sex work, but also in her stance on government and gender. Where feminists like Josephine Ho (何春蕤) and Yin-Bin Ning (甯應斌) claim that the state is causing problems for sex workers through a structure of patriarchy, Ku puts her faith in this structure and asserts that changing it from within

will help women. Ho and Milwertz (2008) (speaking about Ho’s opinion) say that feminists like Ku are separate from the feminists on the other side of the schism because they work with the state, they do not wish to challenge patriarchal gender/sex norms, and they do not condone sex work.

There are, of course, exceptions to this “feminist schism,” but many juridical and institutional definitions (NGOs, activist groups) are defined by this divide. Outside of Taiwan, the debate is historically and socially different, but this same general feminist schism can be applied to the most common views presented.

It should be noted that this schism has influenced a body of academic and juridical work which is polemic due to the focus of discrediting feminists on the other side. The method of genealogy (discussed in detail below) is therefore used as a different angle in this thesis, slicing into the false dichotomy by discovering the genesis of the present day. The result is an answer that goes beyond a simple binary which reduces the sex worker down to a nameless, faceless, non-human entity; or at times an answer that does so intentionally to demonstrate why this is a flawed worldview. The use of different filmic roles attempts to demonstrate the varied aspects and varied forms of sex workers, while the use of reduction down to a commodity body object is used to demonstrate the ease with which power adapts to control that object.

Examining sex worker roles in cinema with a genealogical approach therefore does not fall into these same schism categories. Instead of seeing messages that are “pro” or “anti” prostitute and/or state, much more dynamic characters emerge. The stories of migrants are revealed, as figured in Chung Mong-Hong’s (鍾孟宏) The Fourth Portrait (第四張畫) or Yin-Chuan Tsai’s (蔡銀娟) Stilt (候鳥來的季節). The genealogical impact of history on the modern girl is revealed as in Hou Hsiao Hsien’s (侯孝賢 )Three Times (最好的時光). Or the different

roles and definitions of authority, group law, and masculinity are revealed as in Doze Niu’s (鈕 承澤 ) Monga (艋舺).

Juridical and academic definitions of sex work can therefore be used as a starting point to see which films contain women defined this way and why, but they cannot be adhered to past that. After the initial definition, the films and characters contained within begin to speak for themselves, and for the society and history which they represent. These representations are the main focus of this project. The views of the feminist schism are therefore the first question to be problematized by this thesis, but the discussion quickly evolves beyond this starting point.

The Violent Male Gaze

Film, however, is fiction, and although the selected films in this thesis are intentional social commentaries or histories by their respective directors, the films themselves are also a topic of debate. Here, too, genealogy can be used to create a more complete picture; otherwise the message becomes misinterpreted as one of victimization or condemnation because of a patriarchal male gaze which is too easily attributed to films by certain authors. To give a solid understanding of this issue, an example serves best.

In Heather Griffiths’s 2010 paper about prostitution in cinema, she talks about several prostitute archetypes that evolved in Hollywood cinema from the 1960s to 1990s. With each archetype, the prostitute, she says, is always presented as evil and needs to be redeemed. She is therefore forced to atone for her actions through abuse against her. Her theory is that this is part of a justification for violence against all women. She explains that in the sixties the archetype was “redeemed bad girl,” and that she was given either punishment through death, or redemption through marriage. In the seventies, the archetype was “prostitute as victim,” where the woman

was systematically victimized with violence instead of being punished or redeemed by the filmmaker. In the eighties, she was the “hooker with a heart of gold,” and was emotionally, rather than physically, abused with jokes and satirical slapstick violence. The nineties had two archetypes. One was the “Galatea,” which repeated the sixties pattern, but forced the woman to also repent for her poor upbringing as well as for being a prostitute. The other was the “strong prostitute,” which may seem like a break from the tradition of “forced atonement,” but in reality she is still forced to make up for her wrongs through violence despite choosing her profession willingly. Griffiths bases these archetypes on perpetuation through profit, which she cites as an idea taken from Horkheimer and Adorno.

Heather Griffith’s paper tries to explain only why these films are sexist by creating several categories, and placing each film, by decade, neatly into these categories. She does not explore why prostitutes were placed in these films and what their stories say about society. In other words, her methodology is the opposite of genealogy. Instead, she takes her own

interpretation of Laura Mulvey, who asserted that the camera has a male, voyeuristic, and aggressive gaze, and attempts to fit these films into that premise. She does this by including 40 films, but only shortly summarizing a few as examples of each category she has created. Her research therefore becomes a shallow, two-dimensional glance at decades worth of prostitute films in only a few short pages.

This automatic victimization and claim of misogyny is what the genealogical method will try to counter. Certainly patriarchy can be part of a genealogy. Certainly sex workers are

sometimes victims, face challenges, or are the object of a male gaze in some films, and these are all part of a genealogy too. But they are not the whole picture or the entire explanation—

patriarchy is far from the only construction that impacts our world. Otherwise, by this sort of

definition, making a film that produces productive dialog about sex workers would be impossible. The idea of a universally-applied violent male gaze is therefore the second idea to be

problematized by this thesis. However, these two questions—the feminist schism and the violent male gaze—need not be brought up again and again. This thesis is not a dialogue with the two theories, but instead an alternate way of viewing. The weaknesses of dichotomy and/or a monopolar structural view will naturally be revealed throughout the course of the paper.

Methodology On Genealogy

“Genealogy is history in the form of a concerted carnival” (Foucault 1977: 161).

The genealogical method that this thesis will use is inspired by Foucault and partially by Nietzsche. Foucault applies the methodology very effectively in much of his work, but he also speaks specifically about it when he examines Nietzsche:

From these elements, however, genealogy retrieves an indispensable restraint: it must record the singularity of events outside of any monotonous finality; it must seek them in the most

unpromising places, in what we tend to feel is without history—in sentiments, love, conscience, instincts; it must be sensitive to their recurrence, not in order to trace the gradual curve of their evolution, but to isolate the different scenes where they engaged in different roles (Foucault 1977: 140)

This is the goal of this thesis—to use genealogy to isolate the different scenes in which the sex worker engages in different roles without making them conclude in a “monotonous finality” or an over-generalized explanation. The premise is that cultural conceptions about “the oldest profession in the world”—prostitution—are also erroneously seen as “without history.” The images of the prostitute are often clichéd, and people often have a strong stance on the matter. The sex worker seems like a timeless figure, but she is not.

However, the sex worker is not some Platonic archetype, because, “The world we know is not this ultimately simple configuration where events are reduced to accentuate their essential traits, their final meaning, or their initial and final value. On the contrary, it is a profusion of entangled events” (Foucault 1977: 155). Thus, the assertion of this thesis is simple: If the

historical and societal influences that lead to a director positioning a sex worker in his or her film are examined, then a rich and unique story with its contextual implications will emerge for each of these characters. That is exactly what will be done in the following chapters.

However, there is a singular theme that emerges by performing this genealogy, and it can even be put into a single word: power. But the power relationships that emerge throughout this thesis are by no means singular, do not have a singular source or influence, and do not have a singular cause or effect. It could also be said that the object of power in this thesis is a singular thing: body. But again, bodies do not have singular form, and the power over them is in no way singular. Foucault has a lengthy quote on this topic in Discipline and Punish, which is

nevertheless a priceless insight:

But the body is also directly involved in a political field; power relations have an immediate hold upon it; they invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs. This political investment of the body is bound up, in accordance with complex reciprocal relations, with its economic use; it is largely as a force of production that the body is invested with relations of power and domination; but, on the other hand, its constitution as labour power is possible only if it is caught up in a system of subjection (in which need is also a political instrument meticulously prepared, calculated and used); the body becomes a useful force only if it is both a productive body and a subjected body. This subjection is not only obtained by the instruments of violence or ideology; it can also be direct, physical, pitting force against force, bearing on material elements, and yet without involving violence; it may be calculated, organized, technically thought out; it may be subtle, make use neither of weapons nor of terror and yet remain of a physical order. (Foucault 1995: 25-26)

It is my theory that the commodity body object of the sex worker fits perfectly into this explanation—that the body is tied up in economy and power, and that it is productive, subjected, and a base of resistance—and so I will explore the power relationships that place her in different societal points. However, I would like to add a new angle on this process with the use of films.

When talking about power, Foucault speaks in terms of a gaze operating with a technology of grids. Specifically, he mentions these grids four times in The Birth of the Clinic. His idea is connected with a system of classification, taxonomy, or episteme—in medicine, doctors begin their examination with a series of categories and groups, relating to yet differentiating from one another:

‘The knowledge of diseases is the doctor’s compass; the success of the cure depends on an exact knowledge of the disease’; the doctor’s gaze is directed initially not towards that concrete body, that visible whole, that positive plenitude that faces him—the patient—but towards intervals in nature, lacunae, distances, in which there appear, like negatives, ‘the signs that differentiate one disease from another, the true from the false, the legitimate from the bastard, the malign from the benign’ [13]. It is a grid that catches the real patient and holds back any therapeutic indiscretion. (Foucault 1994: 8)

By relating the characteristics of disease (or whatever is being examined) to one another, the gaze develops and is allowed to know and see, and therefore power over the object develops— ”the gaze that sees is a gaze that dominates” (Foucault 1994: 39).

This is by no means invalid. In fact, this thesis recognizes the grid and employs it to certain ends. For instance, a grid (and it is “a” grid because systems of classification are

malleable and thus the gaze shifts) overlaid on Taiwanese society reveals certain things like the box in the grid called “mail-order bride” being related to the box labeled “sex worker” or “sex worker” being related to categories of “hygiene.” In fact, the most macroscopic grid that is utilized by the gaze for power in this example could be said to be that of the false dichotomy constructed by the feminist schism—one box labeled “good,” and the other “bad.”

However, I have a new way of looking at this grid. This is because when talking about power, speaking in terms of a “grid” could be misleading (however usefully it is employed for the purposes of power). A grid is generally composed of squares or parallelograms, with each individual point equidistant from the others. Geometrically speaking, society is more like a latticework of molecules. Each molecule is composed of atoms, each of which has unique

properties. If an individual body is plugged into this relationship in place of the atom, the properties of the body cause variances in the energy potential, and power will form connections according to the lowest energy potential, meaning the bonding distance between individuals will vary, deforming the shape of the latticework. This means that society is anisotropic—the

properties of society vary in different directions along different axes in multiple dimensions. So it is unrealistic to examine a body—here the sex worker—according to one single point, or even along the y-axis of history. Adding the x-axis of culture is still not enough. The addition of the z-axis of political economy (and possibly even further axes) is required, because the difference in the quality of power between the x and y axis is different than between the y and z axis is different than between the z and x axis. This latticework, stacked in three dimensions according to the energy potential of power, forms the surfaces of the crystal of a society, and that society’s orientation forms according to the energy potential between the surfaces and other societies, forming an uneven grain. Therefore, one cannot find a weak point and crack the latticework along a flat plane. One can only pick an orientation in the x,y,z axes and analyze the bonds leading to other points in the latticework, or one can pull along an axis and examine the surface that emerges along the separation and how this surface differs when the structure is pulled apart along a different axis. By using film, I am using the hyperbole of fiction to more easily locate an x,y,z point in this latticework and pull along the various axes to record the results.

However, this latticework is not completely chaotic, and finding trends in these cultural sources is still useful. There are rules to these power relations—the grids which the gaze uses do exist—and the competing bonds can be traced back genealogically—they are simply not

symmetrical lines with ninety-degree angles. Furthermore, this latticework still takes place on top of the various grids which have been constructed—influencing the gaze and power—and

these will still be taken into consideration (through, for example, the grid of society which differentiates “masculine” from “feminine” under the gaze of “gangster law”).

Structure of the Research

This research will be conducted through a genealogical analysis of Taiwanese cinema, structured in three body chapters with an introduction and conclusion. Throughout the chapters, the broader, global sex work definitions will come from the UNAIDS definition and other conventional (dictionary) definitions. For more specific theory on Taiwanese law and history, Hans Tao-Ming Huang and the laws themselves will be used. For analysis of cinema, semiotic theories will be applied to uncover historical and societal elements (martial law, globalization, historical metaphors etc.) and then the wide variety of scholars most appropriate for those topics will be cited for further understanding. In this way, the cinematic views will be linked to history, politics and society, forming a picture inspired by Foucault’s genealogical methodology, which he uses in such places as The Birth of Biopolitics, The History of Sexuality, Discipline and

Punish, The Birth of the Clinic, etc.

Cinema is a perfect answer for the approach of genealogy because it is a perceived reflection of reality by directors who wish to convey important aspects of that reality—ideas such as gender roles, marginalization, identity, modernity, and citizenship are magnified for examination, and at the same time stereotypes can be subverted by a director’s detailed

articulation. Thus, the main portion of this research will closely examine sex workers, women, immigrants, femininity, and masculinity in modern, globalizing Taiwan (to name only a few influences and roles of the sex worker).

The three chapters on Taiwanese cinema will be organized loosely and somewhat

ironically by “type” of sex worker (to juxtapose the “types” and show the differences between them) to illustrate at a glance that “sex worker” does not mean one specific thing. The

individuals within the types vary—the first cinema chapter only contains one sex worker, a courtesan, but the brothel sex workers in the next chapter serve as stark contrasts for each other, and the migrant sex workers in the third chapter are represented by a mainland spouse who sometimes engages in sex work and a mail-order bride. In other words, the topics will be broad groupings in which the directors will respond in their own unique and varied ways.

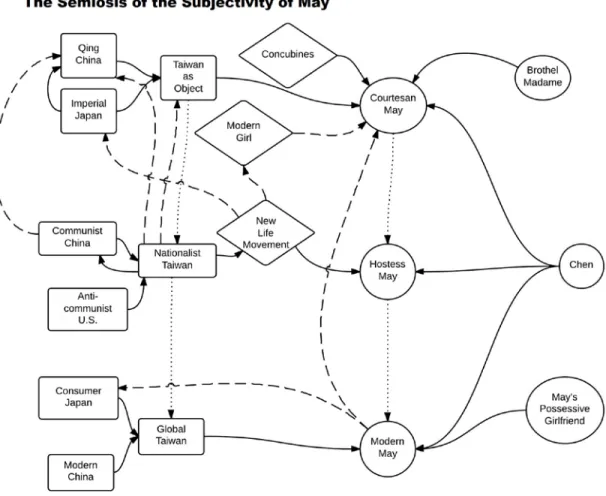

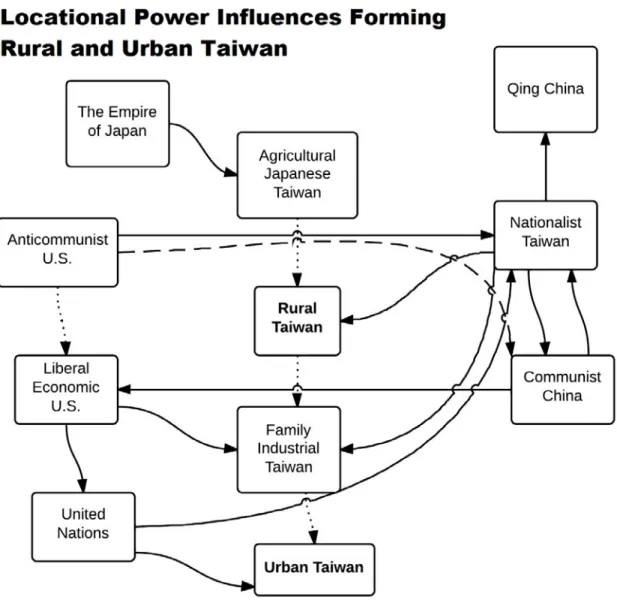

The first cinema chapter (Chapter 2 of this thesis) examines the commodity of sex workers and the influence of power over this commodity which form the semiosis of her subjectivity. It uses the example of the perceived history of females in Taiwan, with their subjectivity being rooted in the symbol of the sex worker in Hou Hsiao Hsien’s (侯孝賢 )Three

Times (最好的時光). In his 1911 segment the woman is objectified and traded as a courtesan.

She is explained through the metaphor of the objectification of Taiwan by the Japanese and the Qing dynasty. In fact, she wishes to stop being a courtesan and become a concubine, which can clearly be seen as a parallel—the status of women reflects the status of Taiwan, and this is confirmed by Chen’s (2008) interview with Hou, in which he says politics are told through individual stories in his film. Hou’s movie is also a memory. One theory that will be explored is that this 1911 story is the common perception of women’s status in the past (it is very simple and clear about the idea that the courtesan is not free and neither is Taiwan), and that is what

influences views that evolve in the other segments of the movie. In the 1966 segment, the woman is seldom outside a pool hall. It will be argued that this is the accepted space of a woman whose job is to be looked at, and also the space in which life can be lived separate from the confusing political background of the times. In this segment she and the male lead seldom speak, and this

may reflect cultural memories about the confusion of what could be done or said about the future under the KMT police state. Compulsory military service is a major part of this segment, and it brings to the forefront the past of World War II and the present of the Cold War, as well as the fading dream of retaking the mainland. This was also an uncertain situation, where Taiwan served visually as a forward base against communism, but was not allowed by the U.S. and the international community to inflame the PRC by acting.

The 2005 segment is presented as a question against the background of those historical memories of the roles of women and the subjectivity which they construct for the character in the present day. The modern woman in Taipei, though physically liberated from being a courtesan and a concubine, and given a voice in the modern era, still struggles with the very recent history when this was not the case. On top of that, she faces the new challenge of how to express herself in a newly consumerist society where she is still not free from societal norms against

homosexuality. Now she is an active exhibitionist, where previously she was forced into that role, and she tries to use this for further progress. She wears a tattoo of a Japanese yen, a symbol of her role in a globalized world with an uncertain future (Japan has been experiencing “The Lost Decade”). She seeks to be an activist by singing songs and making poems on her blog. Set on the background of the rest of the film, technology, capitalism, democracy, and history truly collide in this segment.

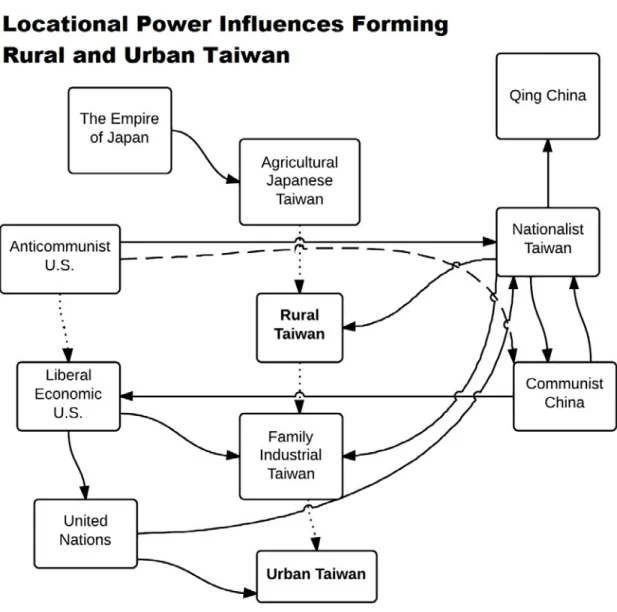

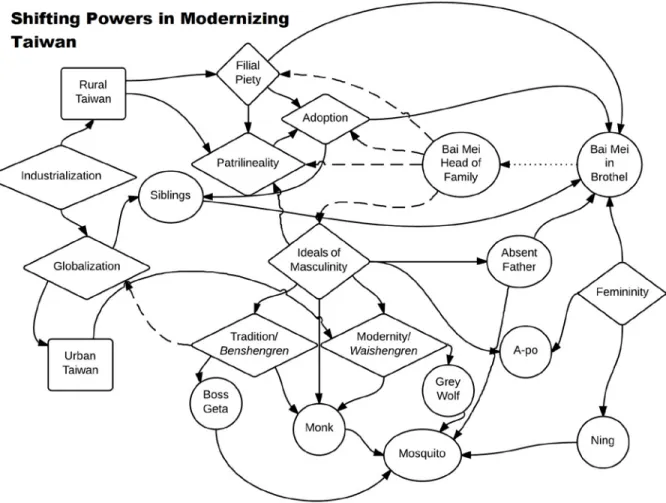

In the next chapter, the focus will move to the illegal, brothel sex worker in Doze Niu’s (鈕承澤 ) Monga (艋舺), contrasted with Tung Wang’s (王童) Days Looking at the Sea (看海的 日子). Days Looking at the Sea was produced previously to 2000, but Monga references the film through parallel imagery, so it will be used as a genealogical source to examine Monga. That being said, while Monga’s brothel scenes visually mirror Days Looking at the Sea, each

addresses the issue of the brothel sex worker in a unique way shaped by the way in which power is constructed and shaped around the socio-economic situation of Taiwan. These two times are only a decade apart but cover a world of difference. They are thus discussed together because of the contrasting views they take of society. Monga examines Taiwan’s gang culture (or what will be dubbed “gang law”) conflicting with femininity, brought to a crisis by incoming Mainland gangs. The focus is on brotherhood as it is equated with femininity and a shared identity of Taiwanese-ness—both a modern view of the director from the globalized perspective and a perception of the 1980’s as Taiwan was becoming more global. Days Looking at the Sea, on the other hand, is looking back at the 1970’s, when local, familial identity took precedent. Another important difference is that Monga addresses power according to the law of gang culture and

Days Looking at the Sea addresses power from filial values (what will be called “family law”).

Aside from those questions, masculine roles in Monga will be examined as a comparison and contrast to the sex worker roles to see how gangsters’ cultural attitudes may glorify and/or condemn aspects of gang life, and why this dichotomy cannot realistically apply as they want it to because of the complexity of the latticework of power relationships. In Monga, the gangsters try to represent such seemingly conflicting themes as masculinity, brotherhood, and loyalty in the face of a changing world in which Chinese gangs from the mainland try to invade Taipei with Western guns. The conflict of identity between Taiwanese (and how that idea manifests) and Chinese is a driving question of the film that seems to be left unanswered, or even deemed as unanswerable. The sex worker comes to represent the main character’s debate over whether to embrace feminine attributes to heal his lack (his lack of a father and his lack of security—the chapter will explain in more detail) or side with uncompromising machismo. This debate, as well as their struggle to side with Taiwanese tradition or Chinese modernity, is extended to all

gangsters.

The final cinema chapter will be about migrant sex workers in Taiwan. It will begin by examining Chung Mong-Hong’s (鍾孟宏) The Fourth Portrait (第四張畫, 2010). This film presents a migrant from mainland China who becomes a citizen by marrying a Taiwanese man and who makes her living by working in a jiudian (酒店). She is not the main character (her son is) but her job and her migrant status are central to the boy’s story. Through this film, the themes of socioeconomic class in Taiwan are explored through her work, as well as the problems of a migrant bride with an abusive husband and the lack of legal options she has to solve them. Her status and the stigma surrounding it shape the life of the boy in the film, who struggles to adapt to living with her and his step-father after his biological father dies. The mother struggles with her job and her inadequate husband to try to take care of the child, and a message about Taiwanese society and poverty becomes clear through this situation.

The final section about migrants regards Yin-Chuan Tsai’s (蔡銀娟) Stilt (候鳥來的季 節). In Stilt, the history of familial norms in Taiwan will be explored to present a struggle to identify what the roles of men and women have become in the modern era. A man is a successful businessman but seen as a bad son; his wife cannot get pregnant and continue the family name. His brother is tough (manly) but the trait is killing him through alcoholism, and his own wife is a mail-order bride from Vietnam. Each character faces historical expectations about masculinity, femininity, and sexuality and in the end provides their own solution to the historical norms, which each go counter to expectations. The focus here will be on the mail order bride from Vietnam. Throughout the beginning of the film, her character is silent, often sitting passively in a pure white dress—a beautiful object to be looked at. However, about halfway through the film, she receives a letter from her love back in Vietnam, and suddenly she becomes much more than

just a passive object. Through her character, the stigma surrounding paid-for migrant brides is explored (and the question of how and whether it is different from legally-sanctioned sex work or normal marriage, bringing the themes back to the first chapter’s exploration of power and commodity). Her mother-in-law constantly questions her value, saying she cannot speak the language, cannot cook or clean, and makes no money. Through this, the roles of a migrant wife in Taiwan are further explored. In the end she becomes pregnant and bears a son soon after her husband succumbs to his alcoholism and dies. Her brother-in-law, who is sterile, and his wife adopt the child, allowing her to return to her love and her life in Vietnam. Through the birth of the child, Taiwanese patrilineal society, citizenship, and tradition are further explored.

It is apparent even by the length and complexity of this summary that through each of these films there can be seen an allegory that goes much further than the simple question of “Is sex work right or wrong?” In some films the allegory is local, dealing with class, gender, or citizenship. In other films the allegory is broader, dealing with national legitimacy, identity, border, and the history of sovereignty. Through this complex web of varied reasons for

positioning sex workers in films, it should be a clear conclusion that the figure of the sex worker is far more important than simple questions of morality or patriarchy. It is a problem which cannot be dichotomized. The genealogy will also reveal that each of these characters does indeed reflect one single realistic image of a sex worker that could be found at some place and time in Taiwan. This will therefore be a history—one which happens to be chronological even though it was not the reasoning behind structuring the chapters—but not a complete one. The purpose of this history will be to reveal that a different approach is needed past making absolute or universal statements. This history will reveal the latticework of power, which is constantly changing and

adapting, and is therefore useful if we wish to change and adapt our own bodies to it as well.

Chapter 2: Commodity and Power

Sex workers are commodities by the definitions examined in this thesis. This is not meant to be a negative judgment, but simply a product of how sex workers are often defined. The Joint UN Programme on HIV and AIDS probably reflects the most idealism, and it states, “For the purposes of this document, sex workers are defined as ‘female, male and transgender adults and young people who receive money or goods in exchange for sexual services, either regularly or occasionally, and who may or may not consciously define those activities as income-generating.’” Here, at first glance, the commodity is “sexual services,” but where do these sexual services come from? From the body, of course. The body therefore becomes a commodity—a use-value which has exchange value, and it does not matter whether this use-value comes directly, in the form of satisfying a need, or indirectly, in the form of a means of production (Marx 1887: 26). Therefore, a sewing machine is a commodity because it is a means of producing clothes. A calculator produces calculations and is therefore a commodity, and of course the word “calculator” in the past referred to a person and not a machine. Bodies, minds, and labor can therefore be commodities. The only place that Marx at first appears to contradict this is where he defines a commodity as “an object outside us” (Marx 1887: 26), but this does not actually

exclude bodies. It only supports the idea that when a sex worker is defined as a commodity, she becomes an object, and furthermore she becomes an object “outside us”—outside of subjectivity. At first glance, this seems to exclude a sex worker from controlling her own commodity,

however, she does not sell “herself,” she sells her body as an object. And that is what is being sold, not literally the sexual services, because there are no sexual services without body—the labor put into a commodity determines (in part) its value (Marx 1887: 29), and in this example,

sexual services are the labor which is being put into the commodity of the body in order to give it value. Therefore, a body can both be used for sex and exchanged for other commodities or money, and this is sex work.

To be clear, Taiwanese sources differ on the definition of sex work, but retain the idea of the sex worker as a commodity. However, this statement should not be shocking. The purpose of stating it is actually to introduce a series of other questions: “Are all bodies commodities?” At certain times, yes. Any laborer has use-value and exchange value, so she is sometimes considered a commodity. This idea aligns with Marx when he points out that labor power can be directly sold as a commodity (but only if it is offered on the market as a commodity—it is often used for other things such as increasing the value of another commodity, as discussed above) (Marx 1887: 117). “Are all instances of sex traded for money, goods, or services considered sex work?” Here, it really depends on definitions. According to the above definition, it looks like this is the case. Taiwanese definitions are similar:

The Criminal Code, first adopted in the 30’s in mainland China, in its most recent incarnation (not counting amendments) in 1979 states, “A person who for purpose of making a male or female to have sexual intercourse or make an obscene act with a third person induces, accepts, or arranges them to gain shall be sentenced to imprisonment...” (Criminal Code of the Republic of China 2013: Article 231). The Social Order Maintenance Act enacted in 1991, Article 80, defines a sex worker as “any individual who engages in sexual conduct or cohabitation with intent for financial gains” (J.Y. Interpretation No. 666 2009). (Pause for a moment here: Cohabitation with intent for financial gains? Does this include wives? This will be an important question later.) Article 2 of the Child and Youth Sexual Transaction Prevention Act of 1995 defines “sexual transaction” as “sexual intercourse or obscene act [sic] for a

consideration.” Finally, (abolitionist) academics have similar definitions: “For the purposes of this paper, prostitution is defined as exchange of personal interaction of a sexual nature for payment. This personal interaction may range from flirting, dancing, and drinking to sexual intercourse” (Hwang and Bedford 2003: 202).

So, then, are we all considered sex workers at some point or another? Interesting question. However, defining a sex worker as a commodified body object is not the main point in itself, but rather it is the question of who (or what) controls this commodity—this body—“In fact nothing is more material, physical, corporal than the exercise of power” (Foucault 1981: 57-58). To trace this question reveals the important power dynamics underneath the surface of all representations of the sex worker—He who has the gold makes the rules. Herein lay the roots of one side of the false dichotomy surrounding sex workers—that they are morally reprehensible. Nietzsche pointed out the power dynamic when he traced back genealogical origins of morality, saying that good is etymologically equivalent to noble, and bad to common (Nietzsche 1996: 14-15) (in German, of course—the case for similar power dynamics existing in Taiwan will be made throughout the thesis through the influence of Western law, common concepts of hygiene, etc.). He also asserted that good is associated with the conquering race, bad with the native (Ibid: 15-17), and along with this idea that “the wealthy” and “the owners” are the meaning of arya, and that to the Greeks, the truth is the powerful (Ibid: 15). Most importantly, he linked the very concept of guilt to economy: “For example, have the previous exponents of the genealogy of morals had even the slightest inkling that the central moral concept of ‘guilt’ [Schuld] originated from the very material concept of ‘debt’ [Shulden]? Or that punishment as a form of repayment has developed in complete independence from any presupposition about free will or the lack of it?” (Ibid: 44).

Indeed, the idea that this commodity (the sex worker, intentionally dehumanized here with my apologies to illustrate the point) has been at the center of a wide variety of social power struggles should not be surprising, and is evident in virtually any film with a prostitute character.

A Time of Freedom: The Sex Worker as Literal Commodity Object

Three Times (最好的時光) is a 2005 movie directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢) and written by Chu Tien-wen (朱天文). May (Shu Qi) fulfills the portrayal of commodity power dynamics in her role as a courtesan who serves Chen (Chang Chen) in the second segment of the film: A Time of Freedom. Before this title is revealed, however, it is contextualized as ironic— none of the characters are free. The opening scene shows a man, heavily framed by sliding doors with wooden panels on glass, forming a parallel grid that gives the visual impression of a cage or a prison cell. Little light shines through the doors in the background which repeat these parallel lines, and the interior is therefore darkened and the colors muted. When he lights the small flame, however, the lighting increases subtly, becoming warmer and more colorful. May is shown, again with the grid of window panels behind her and her own disembodied voice singing the song which will repeat throughout the segment. The voice gives the impression a wailing

mourner. In this scene she pours hot water for Chen when he appears, adding reason to the heavy, cage-like framing and the anguished song—her position is total subservience. The two speak in inter-titles—they are not given a voice of their own, further signifying the powerlessness of every person who (tries to) speak in the segment. Only after these elements are introduced does the title of the segment fade onto screen over the image of a desk set next to yet another window, this time a small, dim opening with the parallel, horizontal and vertical lines crossing over a layer of fogged glass, beyond which is only another layer of the same glass. The objects on the

desk further repeat these lines and heavily frame a potted plant with a small cluster of white flowers at the top, and the plant in turn frames the title, which in Chinese is “Freedom Dream.” Here the flowers, struggling to reach higher out of their pot, can represent the situation of May, the courtesan dreaming of freedom, looking out of her dimly lit cage through the foggy and obscured glass only to see the bars of the second layer.

She plays the lyre for customers, and her job is for her carefully practiced song to be heard. When she plays, she is not given the power of being an active performer or an artist. She appears in the foreground, blurred by the focal point of the camera, which is symbolically focused on the men drinking tea around a table. She is separated from the men by a physical space, which is a signification of the metaphorical space between the courtesan and the world of men. Even the courtesan sitting at the table with the men is separated by look. She is looking downward, never at the men, with her hands folded in her lap, and clearly her job is to look only at the tea cups and refill them when they are empty. Except Chen, the men do not look at either woman, do not take in May’s performance actively as an audience does at a concert, but rather continue their conversation making her part of the atmosphere. Chen himself only looks at May with a sideways glance, his body never facing her, as if he is dividing a small part of his attention from the world of men to be interested in her. The song she is playing is not her own; it is a song she has been taught to play, and it is the sound of tradition—she is, again, not the artist of this song or the author of anything, but a socially positioned piece of entertainment being acted upon but never acting. With analysis, her position is clear, but the power dynamics of her position are conveyed when she takes on the metaphor of another power dynamic—that of the island of Taiwan.

In this segment, Chen is an activist visiting both Japan and China. This takes place in

1911 during the revolution to overthrow the Qing dynasty, but at the time Taiwan was under the rule of the Japanese empire. By making China a strong republic (by ousting the Qing dynasty) it was hoped that it would fight back against colonizers like Japan. The Society to Restore China’s Prosperity had a secret oath among all of its members (one of which was of course Sun Yat-Sen): “Expel the barbarians [that is, the Manchus], revive China, and establish a republic” (Rhoads 1975: 39-40 brackets in text). However, China and Japan were not looking at Taiwan during this situation, the same way the men, the holders of power in that social dynamic of the tea house, do not look at May. The physical space that separates them is analogous to the physical seas that separate Taiwan from the rest of Asia, in a position that never allows Taiwan to act, but only to be acted upon. This all happens in the background of May’s situation, outside of the heavy frames of the dimly-lit windows. She, as a courtesan, also has a master. Taiwan’s is Japan, and hers is the madame of her brothel. While Taiwan is trying to turn to China for freedom from Japan, May is trying to turn to Chen for freedom from her brothel.

She subtly reveals her desires to Chen when she asks about the health of his son while she is braiding his hair. The implied subtext is that she wishes to be part of Chen’s family, but he is already married. It is significant that she is braiding his hair during this scene, because it is both a gesture that she cares about him intimately and a further representation of her role. She is positioned behind him, unseen by him, serving him in a domestic task. This is the role of the concubine she wishes to be (and since he is married she could only hope to be his concubine)— “Both wives and concubines were brought into the household as sexual partners and producers of heirs, but wives were expected to manage domestic tasks, while concubines were themselves managed” (Watson and Ebrey 1991: 241). Thus caring about his son and braiding his hair are meant as gestures that she is willing to fulfill this subservient role. This would not be a problem,

for it is also revealed that A-mei, a fellow courtesan, is going to be sold as a concubine because she is pregnant by Mr. Su. The conflict is revealed through the negotiations over A-mei. May says her madame wants three hundred liang for the girl, but the Su family is only willing to give two hundred. The scenes where this negotiation happens remind that, “The language of gifts and reciprocity was used for wives; the idiom of the marketplace was used for concubines and maids” (Watson and Ebrey 1991: 239). A-mei is being traded from a courtesan to a concubine—she is at this point literally a commodity object. This is even more defined when A-mei’s replacement comes to the tea house to be trained. The young girl appears to be with her father, who is

probably selling her, and she is a depressingly young ten years old. The madame looks her over, feels her chest, her arms, and her behind, and says, “She has good bone structure. But she is a little skinny.” This signifies once again both the commodification as body object of Taiwan’s women at this time—the madame is examining her as if she is evaluating the quality of a product—and emphasizes the fact that the courtesans are there to be looked at (a theme that continues all-throughout the film).

Daughter selling was common in Taiwan much more recently than 1911, especially to become wives, to “lead in” the birth of a son, or to become sex workers (see Wolf 1972: Chapter 11, “Girls Who Marry Their Brothers”), but other women could be bought (as seen above) and sold as well:

The literature suggests that a man could "sell" both his wife and his concubines (see, e.g., McGough 1976:126-27; J. Watson 1980b:231-32; for earlier periods see Ebrey 1986:11, 12). For example, he could pawn his wife or give her away in payment of a debt (for examples see Hershatter and Ocko in this volume). […] It is ironic indeed that wives and concubines may have been more vulnerable to pawning and resale than indentured servants. (Watson and Ebrey 1991: 242)

In an attempt to show that he is a good person, but at the same time demonstrating the irony that he has to do so according to the power constructions surrounding the commodity of women, Chen offers to pay the difference for A-mei to be bought, prompting May to say, “In

your articles, you always criticize the taking of concubines.” Chen replies that he does disapprove of the practice, but in A-mei’s case he feels compelled to help. So while the Qing regime needs to be changed or else China will be too weak and inactive to take Taiwan back from Japan, Chen’s ideas also need to be changed before May can become his concubine. The only difference is that Chen’s problem with taking May as a concubine is noble on his part (unrealistically for a man at his time, but it is a filmic imagination) while the Qing is seen as an inept ruler. In the context of the film, Hou may be foreshadowing (or “post-shadowing,” because the 1966 segment of the film comes before this one) the undesirable coming of the police state of the KMT after Japanese rule. However, forgetting that, taken only in historical context, without looking to the future (which is probably unrealistic considering this portion of the film is entirely positioned to give context to the other two) rejoining China under the Qing is a power dynamic analogous to joining Chen’s household as a concubine.

May adds more context to this power dynamic metaphor in a conversation with A-mei. She begins by saying, “Mr. Su is honorable, his father is also very understanding. You are lucky.” Her next words reveal that in reality A-mei is only lucky because it could be worse. She says, “You will be married tomorrow, your life will change. You will have to rise early to serve your in-laws. Always defer to the first wife. Be humble and never behave willfully.” This is the true power dynamic which happened in Taiwanese households. The reason A-mei’s future father-in-law being understanding is “lucky” is because it means he may treat her less severely if she does not fulfill her role. During this exchange, A-mei appears to be on the verge of tears, and May’s face mirrors her in sorrowful sympathy. Both of them, as women, understand the cultural signifiers that come along with the word “marriage.” She is stepping out from under the rule of the brothel’s madame and into the rule of her in-laws’ household.

As if to call attention to the metaphor to the Taiwan situation, Chen visits May again and says, “Mr. Liang says China will not be ready to help us free ourselves from Japan for another three decades.” And in regards to her own freedom, May says that Madame is seeking a new girl to replace her, and has asked her to stay longer. Now the allegory is complete. Sexual freedom does not exist for her, and even her highest hope, to be a concubine, is pointed out to be a bleak role by her own words. For obvious reasons such as language difference, the continuing rule of the Qing emperor, and the mainlanders’ idea that the Taiwanese were part of the Japanese Empire and therefore could not be fully trusted (as seen, for example, in several places in Wu Zhuo-liu’s Orphan of Asia), reunification was not a great alternative to Japan’s rule. However, like Taiwan under Japan, May cannot choose the alternative. She is forced to wait indefinitely until her madame lets her go.

Clearly, May, as commodity and as sex worker, articulates one possible role of the prostitute. Taken alone, this segment could be misconstrued as a statement against prostitution because it is male violence against women. However, it is important to remember that it is one historical moment, placed in-between two other filmic imaginings of times that come after. What this demonstrates is both that the past of the sex worker influences the future (for all women, as will be shown later and therefore this film cannot be seen as a perpetuation of symbolic male violence against women by victimizing a prostitute) and that when power dynamics change, the entire situation and form of the sex worker changes as well. This is the significance of pointing out that it is not as important that a sex worker is a commodity, but who controls—has power over—that commodity. In this situation it is the madame, serving the male clients.

The other two segments do not contain sex workers (unless the above definition by Hwang and Bedford is taken literally—“For the purposes of this paper, prostitution is defined as

exchange of personal interaction of a sexual nature for payment. This personal interaction may range from flirting, dancing, and drinking to sexual intercourse”—then the pool-hall girl in the 1966 segment is a sex worker, and the modern incarnation of May may be as well, which says something else about the influence of 1911 May in itself) but they do contain women that have internalized the courtesan along with the social symbol of female, and this is partially expressed by the fact that the characters are played by the same actress (Shu Qi) with the same name (May). This argument is justified first by reality—by the fact that, while this 1911 story may seem to be far in the past and evidence of the archaic misogynistic practices of distant history, by 1930, the number of concubines actually increased over previous years (Wang 2000: 168), and the practice was not widely looked down upon until more recently. This means that there are still former concubines, courtesans, and comfort women living today. Furthermore, it is important to

remember that the writer of this film is a Taiwanese female and she is almost certainly speaking about a past that influences her subjectivity. The other justification is given by the ideas of de Lauretis as she speaks about the subjectivity as “a woman” which Virginia Woolf describes from her experiences:

…how does ‘I’ come to know herself as ‘a woman,’ how is the speaking/writing self en-gendered as a female subject? […] By certain signs, Woolf says; not only language […] but gestures, visual signs, and something else which establishes their relation to the self and thus their meaning, ‘I was a woman.’ That something, she calls ‘instinct’ for lack of a better word. In order to pursue the question, I have proposed instead the term ‘experience’ and used it to designate an ongoing process by which subjectivity is constructed semiotically and historically. (de Lauretis 1984: 182)

The last line is most important here. Subjectivity is constructed semiotically and historically. Therefore, the past subjectivities of May as “a woman” influence her future subjectivities, and this becomes what de Lauretis above calls “experience.” This “experience” continues throughout the other segments of the film.

A Time of Love: A Lack of Certainty in Cold War Taiwan

The 1966 segment of the film (A Time of Love in English) actually comes first, but the silence of May in this segment (having quite a bit of on-screen time but very few lines of dialogue) and the uncertainty of the two protagonists leaves the question of why it is this way, and the 1911 segment is the answer.

In the beginning, Chen is drafted into the military, so he leaves a note for Haruko, the girl he likes, at the pool hall. In it he says, “I failed the university entrance exam twice. My mother has died. I have no idea what the future holds.” Of course he would be uncertain about the future because this takes place after World War II, during the Cold War, while Taiwan was serving as a temporary military base for the U.S. in the Vietnam War (one base was located in Kaohsiung, which is the same location of this segment), and during martial law in Taiwan. The 1911 courtesan further expresses why this is confusing—her “dream of freedom” has been fulfilled, but just as hers was a dream that included becoming a concubine, this 1966 story’s power dynamic has also shifted. Individual Taiwanese are thus still acted upon instead of being powerful actors.

The name of the island itself at this time also expresses the confusion of national identity: “After the Nationalist retreat in 1949, Taiwan's identity in English was divided among the names ‘Formosa’, ‘Taiwan’ and variations on China, such as ‘Free China’ and ‘Nationalist China’” (Harrison 2005: 15). The international political significance reaches even further:

In the 1950s and 1960s, this was referred to as the Formosa Problem, in which the US-supported nationalist government on Taiwan was recognized as the legitimate government of China, and held the China seat at the United Nations and the UN Security Council, while the Communist government of the mainland was excluded from international bodies and not recognized by many governments around the world. Many US observers at the time recognized the absurdity of non-recognition of the PRC and understood the hypocrisy of supporting a dictatorial regime on Taiwan called Free China in the name of democracy and freedom. (Harrison 2005: 44)

These elements are not explicit or at the forefront of the characters’ minds, but they are

part of the setting of a very specific historical moment. Charles Warner articulates this concept extremely well:

Throughout “A Time For Love,” Hou stages action, mostly pool playing, in front of doorways, interframing his actors but also underlining the division of interior and exterior space. The outside is often filmed in soft focus or rendered opaque with cigarette smoke. Not unlike his offscreen staging of historical events in City of Sadness, here Hou ruminates on windows and doorways as the spaces through which (official) history impinges on daily existence. If in the earlier film these thresholds set off a private sphere in which political realities can be discussed under the radar of the KMT, in “A Time for Love” they delimit a space in which time is slowed and suspended, in which locals and drifters can seek respite from the whirlwind of social change occurring just outside. (2006)

To add further context to this idea of characters set in a historical moment, the KMT took control of Taiwan 1945, but faced resistance and responded with force, resulting in the eventual 228 massacre in 1947, something Hou Hsiao-hsien is very conscious of, as evidenced by City of

Sadness. He is also a Hakka, who escaped from the civil war in the mainland by coming to

Taiwan in 1948. This places his point-of-view in a unique position. The name “Free China” discussed above also expresses this concept: “The name ‘Free China’ suggests the global

struggle against Communism and Cold War geo-politics, while it effaces the distinction between people who identify as natives of Taiwan, benshengren, and the post-1949 mainland refugees

(waishengren)” (Harrison 2005: 2).Hou would then technically be waishengren, however he was

only a year old when arriving in Taiwan a year before the KMT retreat from the mainland and his Hakka heritage would place him in alliance with the Hakka benshengren of Taiwan. Despite both of these ideas, this segment of his film, which is expressed as a fond memory, takes place in Kaohsiung (further away from the KMT governmental and cosmopolitan center of Taipei) and the actors speak in Taiwanese (not Hakka). There is a linguistic separation between waishengren, the speakers of Mandarin, and the Taiwanese speaking benshengren. Hou’s nostalgic

remembrance of a Taiwanese identity in this segment can again be explained by the 1911 segment of the film, and the violent Other which tried to rule Taiwan: “Japanese rulers imposed

discriminatory policies of separating the local Taiwanese. This encouraged Hoklos [Taiwanese speakers] and Hakkas to form a new collective identity—for the first time Han Chinese in Taiwan saw themselves as a distinctive ethnic group different from the Japanese” (Shih and Chen 2010: 90, brackets my own). Again, as expressed by the metaphor of the 1911 courtesan, Taiwan left Japanese rule only to be governed by a new master. The KMT replaced all of the privileged Japanese official positions with mainlanders, were suspected to be corrupt and inept (by causing inflation and unemployment), and finally put down the rebellion of the benshengren resulting in an estimated 10-20 thousand casualties during and after the 228 incident in 1947 (Shih and Chen: 91-92). After that, and for a period of time until just before Hou’s City of

Sadness breached the topic in 1989, the 228 incident was taboo in Taiwan.

Although efforts to erase 228 from the public consciousness were an attempt to diminish this ethnic tension, the problem later became a central Taiwanese question. This segment of

Three Times could be considered a continuation of the idea of “indigenisation,” since it is a

retrospective look at “the best times.” Yang and Chang explain the concept of indigenisation further:

Indigenisation is arguably the single most important cultural and political development in Taiwan during the past three decades. The process began in the late 1970s in the realm of literary production. During this time, fictional tales that reflected local conditions and grassroots

sensitivity began to gain ascendency over genres transplanted from China after 1949. In the 1980s and early 1990s, indigenisation went hand-in-hand with protests for democracy and the quest for ethnic and social justice, and contributed to the formation of contemporary party politics in Taiwan. Unfortunately, indigenisation also provoked backlashes from civil war migrants and their offspring, who often felt excluded. (2010: 109)

This film is no exception to the idea of a quest for ethnic and social justice. The conflict of Taiwanese identity becomes Hou’s metaphor for the freedom of women in Taiwan (entirely rooted in the power-dynamic that surrounds the courtesan), the confusion and uncertainty he experienced in his youth, and the continuation of that uncertainty in the present day.

The way this all relates to the 1911 courtesan is through the shifting of power given as - 29 -

metaphor for governmental shifts in power between the two sections of the film. The Cold War backdrop of Taiwan is again an allegory for what happened to that courtesan. However, just because Hou presents all of this as metaphor does not mean it had no real effect on actual, historical sex workers—the exact opposite is the case. In fact, after Japanese rule, the 1911 depicted version of the prostitute came under debate. Under the Japanese, these courtesans were legal, but clearly not free. They were a commodity controlled by more powerful forces. When the power of Japan left the island, the laws shifted, but this shift was neither a complete change nor a conscious liberation of women in any sense. It was more of an evolution of power.

The change in opinion during the Post-War Nationalist Period was due to the New Life Movement, for which Taiwan was already primed by Japanese rule and their use of hygiene to control the population.

The New Life Movement was the first state-sponsored campaign to reform people’s everyday lives in modern China. Chiang Kai-shek launched the movement in 1934 in Nanchang, the location of his military headquarters. He defined “New Life” in terms of the traditional moral doctrines of propriety, righteousness, integrity, and conscience (li, yi, lian, chi), but, as the first step in this movement to revive national morality, Chiang chose to focus on disciplined and hygienic behavior. (Liu 2013: 30)

This strict focus on hygiene can be seen from the accounts of informants talking about regular house inspections for cleanliness during the Japanese period in Taiwan in Hill Gates’s ethnography Chinese Working Class Lives: Getting By in Taiwan. In fact, the New Life

Movement took influence directly from the Japanese: “When the modern Japanese police system was introduced into China by Yuan Shikai in the early 1900s, the police managed almost all aspects of social life, such as law enforcement, maintenance of order, public health, charity, political censorship, and correction of undesirable conduct (Reynolds 1993, 162–164)” (Liu 2013: 47-48). Liu gives the accounts of several authors who all essentially say, to varying degrees, that the New Life Movement was central to the formation of a new cohesive state. However, when the nationalists moved to Taiwan they needed to assert this cohesion on the

island. They did this by relying on the image of moral superiority of their culture over the Japanese:

…the police authority in Taiwan had already undertaken this task in the immediate aftermath of Taiwan’s returning-to-China in 1945. Reasoning that ‘our Taiwanese countrymen were allowed under the Japanese occupation to wallow in immorality which must be rectified’ (Taiwan Police

Administration, 1946, cited in Lin 1997: 111), the new Chinese nationalist government launched

in 1946 an island-wide police modus operandi to outlaw hostesses and prostitutes (Lin 1997: 112). (Huang 2006: 239)

It is counter-intuitive, but the eventual licensing of prostitution years later under the nationalists was also in line with this ideology. They still wished to abolish prostitution, but with two approaches. The first was through the law, and the other was through attacking the source of the problem using social welfare, which could only be done through licensing and then taking stock of sex workers and regulating their hygiene, income and social opportunities, and discouraging them from the practice (Huang 2006: 240).

The influences of this use of moral hygiene to control a population and enforce an imagined common identity through the use of a police state are also clearly present in the Criminal Code brought over and adapted from republican period China, in which, until 1999, there existed in the prostitution article a category called “woman of respectable family” (liangjiafunu). If a woman was practicing prostitution she could be put into the category of “accustomed to immoral sexual behavior” and her brothel owner would not be prosecuted for a prostitute that was not of a “respectable family” (The Council of Grand Justices of the Judicial Yuan, Interpretation no. 718 [delivered in 1932], cited in Huang 2006: 239). In other words, it appears that the law itself said that policemen and courts should use their own judgment when it comes to sex workers, because they fall into two different categories. There are those that have good families and should continue to carry on that decent family name, so a brothel owner should be punished for leading such a girl astray. On the other hand there are those that are just “accustomed” to what they do. They are a lost cause, a bad seed, perhaps from a bad family, so

corrupting them is of no consequence.

The meaning of this can be unpacked into several statements. According to this,

prostitution was legally defined as something which violated ideals of “respectable family” until the turn of the last century. A woman was thus expected to serve her family by being morally upright, which prostitution violated. Huang points out that a woman in the sex trade was a

woman who was not married (a sexual deviant). The “woman of a respectable family” label, then, references both her duty to her father and to her (potential) husband. The duality of this, the “accustomed to immoral sexual behavior” label, implies that once a daughter has gone too far astray and become “accustomed” to immorality, at some point it is clear that she is not fit for the only decent role for a woman (marriage to a man) and there is no helping her.

In other words, 1966 May (remember: same actor, same name) is not a courtesan because the KMT is not an empire, using institutions (legally sanctioned brothels) to control the

population, but rather a police state, using the idea of moral superiority of a constructed community (Taiwanese as Free Chinese) and the power relationships of family to control the population. By 1966, the KMT had been licensing prostitutes for a short time, but they had also gone through much effort to suppress the courtesan/geisha houses of the Japanese period and turn prostitutes into hostesses, which at least appeared to be more moral (Huang 2006: 239). 1966 May is part of this “cleaner” version of entertainment, being a hostess in a pool hall. Hou’s metaphors of politics, therefore, are extremely apt for discussing sex workers.

This power shift is what causes the confusion and silence of the protagonists, and that, in turn, is what eventually informs the metaphor of the courtesan. The formation of a Taiwanese identity and this segment, as mentioned above, begin after the end of World War II, which means May and Chen are part of the first generation of youth to experience a life outside of Japanese