台灣的原住民族權利與司馬庫斯案件 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 台灣的原住民族權利與司馬庫斯案件 Indigenous Rights in Taiwan and the Smangus Case. 研究生:芮大衛 指導老師:卜道教授. 政 治 大 國立政治大學. 學. ‧ 國. 立. Student: David Charles Reid Advisor: Dr. David Blundell. 社會科學學院亞太研究英語碩士學位學程. ‧. 碩士論文. er. io. sit. y. Nat A Master’s Thesis. n. a l Master’s Program ini vAsia-Pacific Studies Submitted to the International n C U Collegehof Social Sciences engchi National Chengchi University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. 中華民國九十九年四月 April, 2010.

(3) ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the current development of indigenous rights in Taiwan based on a study of the Atayal community of Smangus in Hsinchu County. The research focuses on a case study of the Smangus Beech Tree Incident, a legal case related to the use of wood from a wind-fallen tree. The case began in 2005, the same year that Taiwan passed the Indigenous Peoples' Basic Law. The events are also placed in the broader context of the modern indigenous rights movement which had its beginnings in Taiwan in the early 1980s and the more than century long history of conflict between the Atayal and the state. Smangus has developed a unique community with a cooperative system of management that draws from both the Atayal tradition and ideas. 政 治 大. from the modern world. Ecotourism is the main economic foundation for the community. The development of Smangus and their assertion of their rights in the. 立. Smangus case provides an example of how indigenous peoples can regain greater. ‧ 國. 學. control over the lands which they consider to be their traditional territory. The thesis then looks at co-management of Aboriginal-owned national parks in Australia. The. ‧. final chapter considers how the co-management model could be adapted in Taiwan and gives recommendations for policy makers.. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Keywords: indigenous rights, Taiwan, Atayal, natural resources management. Ch. engchi. i. i n U. v.

(4) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must express my gratitude to Dr David Blundell for serving as my advisor on this thesis. His wisdom and guidance throughout the entire process has been essential to the quality of the end result. Thanks to Dr Tang Ching-ping and Dr Shih Cheng-feng for serving on the thesis committee. I am glad to have two such distinguished scholars offering their advice to me. Many thanks to the people of Smangus, especially Lahuy Icyeh and Icyeh Sulung. My classmate Ben Goren assisted me in the early stages of this research and coproduced the video Stumped: Smangus and the Spirit of Self-determination. Ben also. 政 治 大. gave me helpful feedback and advice during the writing of the thesis. Another. 立. classmate Sandy Ho took me on a trip to Smangus and introduced me to the Atayal. ‧ 國. encouragement.. 學. village of Qingquan. I am also grateful to Patty Lee for her friendship and. ‧. Dr Lin Yih-ren was the first person I interviewed about the case. I interviewed him again as the thesis neared completion. On both occasions he was very helpful and. sit. y. Nat. offered many insights.. er. io. Thanks to the other people who gave their time to be interviewed: Chiang Bien, Lin. al. Chiang-I, Lin Shu-ya, Lai Tsung-ming, Pisuy Masou, Kung Wen-chi and Yohani. n. v i n Isqaqavut. Their many insights haveCadded great value and depth to this thesis. hengchi U. Also thanks to the staff at the Forestry Bureau, especially Shawna Wu. The staff of Kung Wen-chi's office were also very helpful. Boris Voyer arranged the interview with Yohani. Yapasuyongu Akuyana discussed some of the ideas with me.. ii.

(5) Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................i Acknowledgements........................................................................................................ii Chapter One – Introduction............................................................................................1 1.1 Overview..............................................................................................................1 1.2 Scope of study......................................................................................................3 1.3 Methods................................................................................................................4 Chapter Two – Defining indigenous peoples and indigenous rights..............................7 2.1 Defining indigenous peoples................................................................................7 2.2 The international movement for indigenous rights..............................................9 2.3 The politics of identity in Taiwan.......................................................................11 2.4 Indigenous rights movement in Taiwan.............................................................16 2.5 Some examples in Taiwan..................................................................................20 Chapter Three – Atayal culture and Smangus...............................................................25 3.1 Atayal people......................................................................................................25 3.2 History and culture of the Atayal.......................................................................26 3.3 Atayal claims and conflict over territory............................................................29 3.4 Defining traditional territory..............................................................................31 3.5 Contemporary Atayal culture.............................................................................34 3.6 Christianity and the Atayal.................................................................................37 3.7 Migration story and origins of Mrqwang group and Smangus..........................37 3.8 Smangus community and village environment..................................................38 3.9 Smangus cooperative and ecotourism................................................................42 Chapter Four – case study.............................................................................................47 4.1 Conflict between Atayal and government agencies...........................................47 4.2 Indigenous rights to land and resources.............................................................47 4.3 Opinions of policy makers.................................................................................50 4.4 Smangus Beech Tree Incident............................................................................52 4.5 Interviews and Smangus blogs...........................................................................53 4.6 Perspective of the chief......................................................................................54 4.7 Perspective of the Forestry Bureau....................................................................55 4.8 The court hearings..............................................................................................56 4.9 Smangus community uniting with other groups................................................58 4.10 Conflict between Smangus and the state..........................................................59 4.11 Smangus assertion of sovereignty....................................................................62 4.12 Final summary of the Smangus case................................................................64 Chapter Five – Co-management in Australian National Parks.....................................65 5.1 Australian Aborigines and land rights................................................................65 5.2 Kakadu and Uluru-Kata Tjuta national parks....................................................65 5.3 Co-management in Kakadu and Uluru...............................................................67 Chapter Six – Conclusions and recommendations.......................................................71 6.1 Realising indigenous rights................................................................................71 6.2 Taking the co-management model to Taiwan.....................................................73 6.3 Indigenous peoples as custodians of the land....................................................76 References.....................................................................................................................79 Appendix I....................................................................................................................89. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(6) The Forestry Act.......................................................................................................89 Appendix II.................................................................................................................107 Indigenous Peoples' Basic Law..............................................................................107 Appendix III................................................................................................................115 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.........................115 Appendix IV...............................................................................................................129 Time line of events.................................................................................................129. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

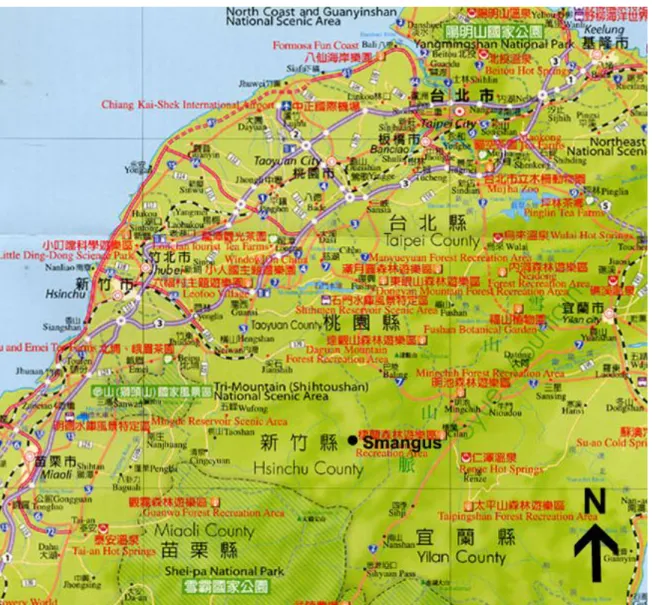

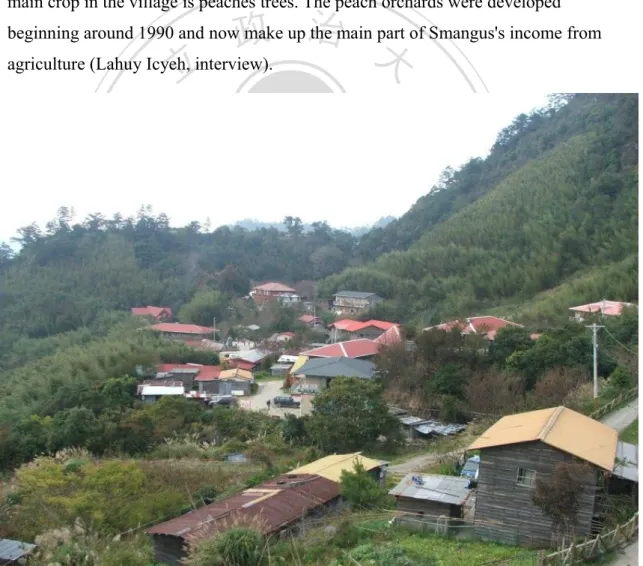

(7) CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview The indigenous peoples of Taiwan and Orchid Island are currently recognised as members of 14 ethno-linguistic groups. They are the inheritors of a cultural heritage that can be traced back more than 6,000 years to the beginning of the Neolithic period on Taiwan. This population of 430,000 people currently makes up about two percent of the Taiwan population (Council of Indigenous Peoples, 2007). Taiwan's contemporary indigenous rights movement had its beginnings in the early 1980s (Chiang, 2004: 41-42; Hsieh, 1994a: 408-410). Since the lifting of Martial Law in 1987 there has been significant development of indigenous rights in parallel with. 政 治 大. Taiwan's democratisation. In the past decade this movement has led to the drafting and. 立. passing of a number of laws which promote and protect the rights of Taiwan's. ‧ 國. 學. indigenous peoples. The cornerstone of this legislation is the 2005 Indigenous Peoples' Basic Law (IPBL).. ‧. Taiwan passed the IPBL in January 2005. The law aims to protect and promote the rights of Taiwan's indigenous peoples in accordance with the standards of the United. Nat. sit. y. Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The IPBL. er. io. represented a significant landmark in the development of indigenous rights in Taiwan. However, the high aspirations of the IPBL do not match the reality of practice by. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. government institutions or the expectations of indigenous peoples. To better. engchi. understand how the IPBL works in practice this thesis makes use of a case study of Smangus in Hsinchu County. Smangus is a community of Atayal people located at an altitude of 1,500 metres in the mountains of Jianshi Township of Hsinchu County. The Atayal are the second largest indigenous group in Taiwan. They follow a system of traditional law inherited from their ancestors known as the gaga. The Smangus Beech Tree Incident relates to events that took place in September and October 2005. A beech tree fell across the road to Smangus during a typhoon. The Forestry Bureau later removed the most valuable timber. The Smangus community held a meeting and asked three men to bring the remaining parts of the tree back to the village. The three Atayal men from Smangus 1.

(8) village were subsequently charged with theft of forestry products under the Forestry Act. The three men were found guilty in the initial court hearings in the Hsinchu District Court and High Court. In December 2009 the Supreme Court sent the case back to the High Court for review. On 9 February 2010 the High Court found the three men were found not guilty bringing an end to the four year long legal battle. Although the case eventually reached a satisfactory conclusion it highlights the weakness of the law in Taiwan in upholding indigenous rights, particularly in regard to rights to land and natural resources. It provides an example of conflict between national law and the traditional law of indigenous peoples. It is also part of an ongoing conflict between the state and the Atayal people over rights to land and resources that can be traced back to the late nineteenth century. In the present time, the state is. 政 治 大 government over the lands which indigenous peoples have lived on for many 立 generations and claim as their traditional territory. Indigenous peoples as the original represented by the Forestry Bureau which exercises the authority of the central. ‧ 國. 學. sovereign owners of the land seek to reclaim their rights to use natural resources from the land according to their traditional law and customs.. ‧. The Smangus Beech Tree Incident and subsequent legal case highlight the weaknesses. y. Nat. that exist in applying laws that recognise indigenous rights in practice. The reasons for. sit. this include lack of clear legal definitions of indigenous peoples' traditional customs. er. io. and territory and differences in language and world view. Further legislation and. al. n. v i n C h makers form part the situation. Recommendations for policy e n g c h i U of the conclusion of the. changes in the way institutions deal with indigenous peoples are necessary to improve thesis.. This thesis explores in detail the contemporary situation of indigenous rights in Taiwan, in particular the ongoing conflict over rights to land and natural resources. It also seeks to find the key reasons why the IPBL has not matched its aspirations in practice and ways that indigenous people can assert their rights by drawing on their culture and traditions. The key research questions are: How can indigenous people assert their rights to land and resources? Should they do this through the legal system, negotiation involving all stakeholders or adopt other approaches? To further understand how indigenous peoples can gain control over the management 2.

(9) of their lands the thesis also looks at the case of two Aboriginal-owned national parks in the Northern Territory of Australia. These national parks are operated under a system of co-management. The final chapter then considers how a system of comanagement could be adopted in Taiwan. This thesis provides a substantial examination of the contemporary situation of indigenous rights in Taiwan. Although there already a number of book chapters, articles and theses on this topic in English, indigenous rights are cast in a new light by the 2005 IPBL and the policies of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government from 2000 to 2008. It also includes the first case study of the Smangus community in English. Hence this thesis intends to provide the most up to date analysis of the present situation of Taiwan's indigenous peoples.. 1.2 Scope of study. 立. 政 治 大. The focus of this study is the period from 2005 to the present. This time period covers. ‧ 國. 學. two important events. First the IPBL was passed in January 2005 creating a new framework for indigenous people to argue for their rights. It focuses on the. ‧. community of Smangus in Hsinchu County and the case regarding use of wood from a. Nat. sit. with the not guilty verdict passed down by the High Court.. y. wind-fallen tree in 2005. The subsequent legal case came to an end in February 2010. er. io. While the study is focused on recent events it also covers the historical background of. al. n. v i n C h over the past 400Uyears. The ethnic structure of Chinese, Japanese and Europeans engchi indigenous peoples in Taiwan and the settlement and colonisation of Taiwan by. Taiwan is complex. Where I make reference to ethnic or linguistic groups within. Taiwan I use specific terms to describe these groups. Where I use the term Taiwanese it applies to the all the people living in the political entity of Taiwan. There are two major political parties in Taiwan. The Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang (KMT) first came to Taiwan in 1945 as the de facto occupying power after the Japanese surrendered at the end of World War II. In 1949 the KMT fled en masse from China to Taiwan following the loss of the civil war in China to the Communists, relocating the national capital from Nanjing to Taipei and re-establishing the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan. The KMT ruled Taiwan under Martial Law. 3.

(10) until 1987. Following the end of Martial Law and the death of Chiang Ching-kuo in 1988, native Taiwanese Lee Teng-hui became President. He implemented numerous reforms that facilitated a shift from one-party dictatorship to democracy and in 1996 was re-elected President in Taiwan's first direct presidential election. The DPP was officially founded in 1986, quickly becoming the main opposition party as the practice of democracy developed in Taiwan. Taiwan experienced its first democratic transition of power in 2000 when DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian was elected President, allowing the DPP to gain control of the executive branch of government. The indigenous policies implemented by the DPP in the period 2000 to 2008 represent a new approach from the previous policies of the KMT. The KMT reclaimed control of the executive again in 2008 with the election of Ma Ying-jeou as President.. 政 治 大 speaking peoples of Taiwan and Orchid Island. They are the peoples officially called 立 yuanzhuminzu (indigenous peoples) by the government of Taiwan. There are 430,000. The indigenous peoples whose rights are the subject of this study are the Austronesian. ‧ 國. 學. people officially recognised as indigenous in Taiwan, making up 1.9 % of the population (Council of Indigenous Peoples, 2007).. ‧. Historically, Taiwan's indigenous peoples were categorised according to a “nine. y. Nat. tribes” model which was based on studies by Japanese ethnographers. However, there. sit. are now 14 officially recognised ethno-linguistic groups. There is also a movement for. er. io. the Pingpu (plains) peoples to recover and reclaim their identity. The number of. al. n. v i n C identity in Taiwan U the future. Issues related to indigenoush e n g c h i and definitions of. groups and criteria for being identified as indigenous in Taiwan may change further in indigenous peoples will be further discussed in Chapter Two.. More specifically this thesis focuses on the Atayal people, an ethno-linguistic group that live in the mountainous areas of northern Taiwan. It includes a case study of the Atayal community of Smangus. More details about the Atayal and Smangus are provided in Chapter Three and Chapter Four of this thesis.. 1.3 Methods A case study of the Smangus Beech Tree Incident forms the core part of the thesis. It is centred around the incident involving a wind fallen beech tree occurred in. 4.

(11) September and October 2005 and the subsequent legal case which ended with a not guilty verdict from the High Court in February 2010. It also looks at Smangus as a community in the broader context of Atayal culture and contemporary society in Taiwan. Research on the case includes a literature review, key informant interviews, review of related Internet websites and field observations. The Smangus case is not the only case where indigenous rights have been contested in Taiwan's courts. However, there are a number of reasons why Smangus was chosen for the case study in this thesis. The Smangus case occurred in the same year that the IPBL was passed meaning that is one of the first substantial tests of the IPBL in Taiwan's courts. The case attracted attention and support from academics and NGOs so it was well observed and also reported in the media.. 政 治 大. The Smangus community also has some special characteristics. It is a remote village. 立. where the people maintain a strong sense of self reliance and independence. The. ‧ 國. 學. people of the village seek to actively pass on their language and cultural traditions to future generations. At the same time the village has been open to outside influences and has adopted a system of cooperative management and ecotourism as the economic. ‧. base of the village. There has also been ongoing contact with academics, particularly. y. Nat. in a mapping project to define the community's traditional territory. Hence, there is. sit. documentation and expert witnesses to support Smangus's claims of traditional. n. al. er. io. territory (Lin Yih-ren, interview).. i n U. v. The experience of Smangus is different from other indigenous communities in Taiwan.. Ch. engchi. A limitation of the case study method is that while it can make descriptive inferences to other cases it can't establish causal relationships (Gerring, 2004). It may not be possible for every indigenous community to replicate the model of Smangus. However, they can certainly learn important lessons from it and adopt these to their own unique circumstances. To obtain a deeper understanding of the Smangus case I have conducted interviews with a number of people who have been involved in or observed the development of the case. I have also interviewed several people in government who play key roles in the formulation of Taiwan's indigenous policies to learn more about the important issues in the broader field of indigenous rights. 5.

(12) Most interviews were recorded with a digital audio recorder and several of the interviews were video recorded. In addition to the recording some basic notes were made at the time of the interviews with more detailed notes or transcriptions later made from the recordings. A few of the interviews were recorded by hand written notes only. For the people of Smangus Mandarin is a second language. They may not be able to fully explain concepts related to the gaga (Atayal traditional law) and traditional territory in that language. Hence my ability to understand some of these concepts through interviews is somewhat limited. These interviews form the basis of a qualitative study. The case study is focused on events that have happened from September 2005 to the present so it is expected that interviewees can reliably provide detailed and accurate accounts of these events. Some. 政 治 大. interviewees also supplied additional materials at the time of the interview and these. 立. were kept and filed.. ‧ 國. 學. I have made three trips to Smangus to conduct interviews and learn about the local conditions. The first two trips were for one day only in December 2007 and April 2008. During these visits there was only time to conduct interviews and have a brief. ‧. tour of the village area. In August 2009 I spent two days in the village. The longer. y. Nat. visit enabled me to see a wider variety of things in the village and gain a better. sit. understanding of how everything works. I also had time to hike to the grove of old. n. al. er. io. trees. I have also been able to learn more about the broader situation of indigenous. i n U. rights in Taiwan by attending several conferences and protests.. Ch. engchi. v. There are large bodies of literature related to the international issue of indigenous rights and the ethnology of the peoples of Taiwan. In the area of contemporary indigenous rights in Taiwan the availability of published materials in English is more limited, but cover all the major events of the past few decades. The Smangus community blog also provides an important resource for study. Because of my limited ability to read Chinese only a few documents written in Chinese have been used as references.. 6.

(13) CHAPTER TWO – DEFINING INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND INDIGENOUS RIGHTS 2.1 Defining indigenous peoples In a study of indigenous rights it is important to establish a definition of indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples are generally the peoples and cultures that existed before the. European expansion and colonisation of the globe that began in the sixteenth. century. Indigenous peoples include the peoples variously referred to as indigenous, Aborigines, tribes, First Nations, ethnic minorities, natives or other terms in different parts of the world. A United Nations study describes indigenous peoples as follows. Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a. 政 治 大. historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that. 立. developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors. ‧ 國. 學. of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their. ‧. ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in. y. Nat. accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal. er. io. sit. systems (UN, 1995 quoted in Anaya, 1996: 5).. However, in many cases the people identified as indigenous today are not the original. n. al. i n U. v. inhabitants of the land. The indigenous peoples themselves often displaced or. Ch. engchi. assimilated previously existing cultures during earlier migrations and the transition from Paleolithic to Neolithic periods. It is also important to consider that the societies of indigenous peoples are not static. Even in pre-modern times they were undergoing change and evolution due to a variety of factors. In the Americas and Oceania it is relatively easy to distinguish the historical moments at which the indigenous peoples began to have contact with outsiders. In other parts of the world the point of demarcation between the original peoples and the subsequent arrival of colonisers or settlers is often less distinct. Furthermore, the arrival of colonisers or settlers on their lands brought about even more fundamental changes in the societies and way of life of the original inhabitants. The indigenous cultures we 7.

(14) observe today can still be considered to represent a continuum from the past though. Indigenous peoples are usually seen as having connections to land and territories. However, this view is also somewhat problematic. In many cases they have been forcefully displaced from their lands. In some cases they may have maintained contact or still identify with their traditional lands even though they are no longer living on those lands. In other cases they may have resettled in new areas and recognise these new areas as their own lands. A second issue is voluntary migration, primarily from isolated or rural areas to urban areas. This may be driven by economic factors or for better access to education, healthcare and other services. Most government policies are formulated based on the view that indigenous peoples are resident on their traditional territories and don't take into account that a large. 政 治 大. percentage of indigenous peoples may have migrated to urban areas. The United. 立. Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) does not mention. ‧ 國. 學. the words city, urban or migration (Watson, 2009). This thesis is focused on indigenous peoples living on lands which they consider to be their traditional territory. The issue of indigenous peoples in urban areas and migration of indigenous peoples is. ‧. a subject that needs further research.. sit. y. Nat. Blundell (2008) discusses issues of indigeneity and cultural heritage in the context of. io. er. Taiwan and Sri Lanka, in particular looking at the usage of the word “tribe”. Tribe means a hierarchical group organisation with “chiefs, nobility and commoners.” In. n. al. i n U. v. Taiwan the word used for indigenous groups, zu in Mandarin Chinese, is usually. Ch. engchi. translated as tribe. However, it really means “lineage” or “descent of clan”. Also indigenous groups of Taiwan are not necessarily tribal in terms of their social organisation. Hence, in Taiwan tribe is a misnomer applied to ethno-linguistic groups who are officially known as yuanzhuminzu, meaning indigenous peoples. Tribe is also used in Taiwan to refer to villages or communities of a few hundred people. This compounds the problem of mislabelling although this doesn't occur in Mandarin where the word buluo is used to refer to a village or community. A buluo is typically made up of tens or hundreds of people living in the same area and maintaining close relations and sharing of resources. Historically this has been the primary unit of social organisation of indigenous peoples in Taiwan. In this thesis I 8.

(15) use village to refer to the physical collection of houses and living space. Community refers to a group of people who share close social relations and common heritage. There is an additional term in Mandarin, qun, which is used to categorise ethnolinguistic groups into smaller groups that are still larger than a single village. The word qun translates as group and in this thesis will be translated as group or sub-group depending on the context. Hence the Mandarin Chinese terms for classifying indigenous peoples in Taiwan are accurate, but they are often translated into English incorrectly.. 2.2 The international movement for indigenous rights Indigenous rights refer to the rights of indigenous peoples, both individually and. 政 治 大 sovereign powers of their territory. As a result of settlement or colonisation they were 立 marginalised and lost their sovereignty. The indigenous rights movement is based on collectively. Indigenous peoples represent a continuous culture and were once the. ‧ 國. 學. reclaiming lost sovereignty and recognition of rights under the law. Anaya (1996) provides the most comprehensive overview of indigenous people and. ‧. international law. His work looks at indigenous peoples and the framework of. y. Nat. international law beginning from Europe's relations with the peoples of the Americas. sit. in the sixteenth century to the contemporary situation. The key argument of Anaya is. er. io. that international law has shifted from a discourse of sovereignty to human rights. Self. al. n. v i n C contemporary international He concludes by looking at theh framework of indigenous engchi U. determination is a key foundation of human rights that applies to indigenous peoples. rights including the institutions, procedures and key documents.. The legal framework, which Anaya has charted the development of, reached a landmark with the adoption of the UNDRIP by the United Nations General Assembly on 13 September 2007. Oldham and Frank (2008) analyse the process of the drafting of the UNDRIP and the final negotiations that led to its adoption. Indigenous people actively participated in the drafting process which took place over 23 years. This period corresponds with the emergence of the international indigenous peoples' movement focusing on the United Nations (UN). The movement began in the 1970s and expanded in the during the 1980s. The indigenous representatives did not see. 9.

(16) themselves as creating new rights, but sought affirmation of rights in existing treaties that had been denied to indigenous peoples. The UNDRIP doesn't actually define indigenous peoples. An official definition of indigenous peoples has not been adopted by any UN organisation. Definition and recognition of indigenous peoples is left up to individual states. A key point however is focusing on self-identification and identifying rather than defining (UN Permanent Forum, n.d.). Oldham and Frank (2008) make recommendations on the use of the UNDRIP by anthropologists. They say it merits anthropological analysis through contributions to the emerging anthropology of international institutions, law and human rights. Also anthropologists engaged in field work could report on the status and application of the. 政 治 大. UNDRIP. Messer (1993) also examines the links between anthropology and human. 立. rights. Anthropologists were once critical of human rights because of cultural. ‧ 國. 學. relativism, however they have now shifted to seeing human rights as setting minimum standards for human dignity. She suggests ways that anthropologists can contribute to human rights through their work. Another significant recent contribution to the. ‧. discussion about the relationship between anthropology and human rights comes from. sit. y. Nat. Goodale (2006).. io. er. Orlove and Brush (1996) consider the role that anthropologists can play in the promotion of the conservation of biodiversity through the participation of local. n. al. i n U. v. peoples, namely farmers and indigenous peoples. They write that anthropologists are. Ch. engchi. particularly well suited to the study of protected areas because of their commitment to long term field studies in remote areas and willingness to study not only the local population, but others such as government officials, biologists and NGO workers. Anthropologists have also engaged in debates over the future of protected areas as advocates for indigenous rights, cultural intermediaries and expert witnesses. Anthropologists have argued strongly for the participation of local peoples in the management of protected areas. These arguments may be based on social justice, human rights or pragmatic reasons. The most common research method used is the interview based longitudinal case study of local peoples and their interactions with outside groups such as the government, NGOs and the media.. 10.

(17) 2.3 The politics of identity in Taiwan Defining indigenous peoples in Taiwan is often intermeshed with politics. Taiwan's status as a nation is contested and national identity is very much a political battleground. During the 1990s President Lee Teng-hui promoted Taiwanese consciousness and localisation. This was a counter to the Chinese nationalism that had been a part of the authoritarianism during the years of Martial Law. Localisation was further promoted during the eight years that Chen Shui-bian was President. After Ma Ying-jeou became President in 2008 he again sought to return to a form of Chinese nationalism through the idea of Taiwanese being part of the Zhonghua Minzu (Greater Chinese Ethnic Nation). However, in spite of this numerous opinion polls show that the people of Taiwan still increasingly identify as Taiwanese rather than Chinese.. 政 治 大 Taiwan ensure that this trend is not something that will easily be reversed. 立. Democracy and the hostile attitude of the People's Republic of China (PRC) towards. Taiwan's indigenous peoples are in many ways marginalised by this debate. They are. ‧ 國. 學. the original peoples of the island and were here for thousands of years before the Dutch, Chinese and others started to settle on the island. The debate is largely a. ‧. contest between the Hoklo-speaking peoples who trace their roots on Taiwan back. y. Nat. four hundred years and the Chinese who arrived with the KMT after 1945 and became. sit. the ruling elite of the Republic of China on Taiwan, imposing their Chinese. er. io. nationalism on the Taiwanese people through the education system. The efforts to. al. v i n Ch taught them a form of Chinese culture that was divorced e n g c h i U from the Chinese cultural n. assimilate indigenous peoples through the education system and teaching of Mandarin. practices of the Hoklo and Hakka speaking peoples in Taiwan (Harrison, 2001: 69, 73). In the 1950s indigenous peoples realised that the Japanese or indigenous identities that had once been useful had become a political liability. Different communities chose to adopt the “Chinese” identity being promoted by the Nationalist (KMT) government because it was politically advantageous (ibid.: 74-75). Hence the indigenous peoples found themselves better accommodated by the politics of the KMT rather than the DPP which is often linked to a Hoklo-Taiwanese nationalism. In addition there is not the same history of conflict between indigenous peoples and the Chinese who arrived after 1945 as there is with the Hoklo-speaking peoples. With regard to the latter there has been 400 years of fighting over access to 11.

(18) land. This is further complicated by the fact that the Hoklo-speaking people intermarried with the Pingpu (plains peoples) (Brown, 2004). The indigenous groups that remain today are the peoples who have resisted assimilation with the Chinesespeaking settlers on Taiwan for 400 years. There are several competing theories on the origins of Taiwan's indigenous peoples. These theories may also be used to support certain political views or agendas. The southern origin theory, that the peoples migrated from the Philippines or Malaysia is used to distance Taiwan from China. It highlights the non-Chineseness of Taiwan, emphasising the uniqueness of Taiwan's peoples and negating the claims of the ROC and PRC to Taiwan (Stainton, 1999a: 29-32). The northern origin theory, that the peoples migrated to Taiwan from the area that is now southern China, is used to show. 政 治 大 37). Finally, the Austronesian Homeland theory is that Taiwan was the place of origin 立 of the Austronesian languages. This theory is a refinement of the northern origin the connections between Taiwan and China with China as the motherland (ibid.: 32-. ‧ 國. 學. theory suggesting early neolithic migrations from continental Asia followed by independent development in Taiwan. This theory places Taiwan at the centre and links. ‧. indigenous identity with Taiwan identity (ibid.: 37-41).. y. Nat. Current evidence and academic discourse gives greatest support to the Austronesian. sit. Homeland theory. This is based on analysis of linguistic and archaeological evidence. er. io. from Taiwan and the many islands of the Indian and Pacific oceans where. al. n. v i n C is primarily a lingustic one. Bellwood'shhypothesis i U based on the linguistic e n g cishlargely. Austronesian-speaking peoples are found (Bellwood, 2009). The idea of Austronesian view of Blust and supported by archaeological evidence (Paz, 1999: 151-152).. Blundell (2008) suggests the “idea of an ethnic continuum as a value deserving protection as an endangered heritage.” The Formosan-language speaking peoples of Taiwan represent a continuum from the origins of a language family extending back 6,000 years that now spans the Indian and Pacific Oceans. That the culture and knowledge of indigenous peoples has value as heritage implies that it is valuable not only to the peoples themselves, but as a living resource for the whole world to learn from. The historical position of Taiwan's indigenous peoples is one of a gradual loss of 12.

(19) sovereignty and rights as a result of European, Chinese and Japanese settlement and colonisation over four centuries. Hsieh (1994a: 404-406) divides the history of Taiwan's indigenous people into several periods according to their status. In the period up to 1624 they were the “only masters” as the only people living in Taiwan during this period were the indigenous Austronesian speaking peoples. From 1624 to 1661 they were “mostly masters”. The plains peoples who came under the rule of the Dutch and Spanish lost their superior position, but peoples in the other regions of Taiwan were unaffected. From 1661 to 1875, under the rule of Koxinga and the Qing (Manchu) dynasty, they were “half masters”. Indigenous peoples in the mountain areas and east coast retained their position of master while the plains peoples were assimilated into the dominant culture. From 1875 to 1930 they were “masters in fewer. 治 政 大and gradually established areas and then in 1895 the Japanese occupied Taiwan 立 control over the entire island. Indigenous people resisted rule by foreign powers, but areas”. In 1875 the Qing government began to extend its power into the mountain. ‧ 國. 學. were still eventually conquered. The Wushe Rebellion in 1930 marked the final major act of resistance, after which the indigenous people were completely conquered. The. ‧. final period from 1930 to the present is “lost position of master completely”.. y. Nat. The succession of colonial regimes on Taiwan have shaped the identity and position of. sit. Taiwan's indigenous peoples today. For the Atayal and other peoples that lived in the. er. io. high mountains it was not until the Japanese era that their position underwent a. al. v. n. massive change. External forces have tried to change the identities of these peoples. i n first to become Japanese andCthen to become Chinese. hengchi U. Indigenous memories of the Japanese era are mixed. Many express admiration for the Japanese while simultaneously remembering the oppression that they suffered. Simon (2006) contrasts the memories of the Truku people in Hualien with those of the “Native Taiwanese” (Hoklo and Hakka speakers). For indigenous people the Japanese era was important for identity formation because it positioned them as resisters against colonialism. The Native Taiwanese lived through the Japanese colonial period unlike those Chinese who arrived with the KMT after 1945. Memories of the Japanese era are central to their ethnic identity. They see the Japanese period as a symbol of modernity and Japanese education as a sign of higher levels of development than China at that time. 13.

(20) In the late 1940s and 1950s when Taiwan was under the rule of the Chinese KMT indigenous identity was in a state of flux. Harrison (2001: 51) argues that indigenous peoples didn't necessarily have Chinese identities forcefully imposed on them, but chose their identity to suit the circumstances. In the 1950s villages chose a “Chinese” identity because of the perceived political and social advantages. Harrison looks at the case of Ma Zhili. Ma was the son of a Fujianese man who fled to a Puyuma community in the hills to escape trouble with the government. Ma Zhili grew up speaking Hoklo and Puyuma. He attended a Japanese school where he became fluent in Japanese. He married the daughter of a Puyuma elite and became a “chief”. Ma was able to skillfully adopt these different identities for personal and political advantage under both the Japanese and Chinese regimes (ibid.: 62-63).. 政 治 大 indigenous peoples to have more opportunity to define themselves on their own terms. 立 The “nine tribes” model was based on the work of Japanese anthropologists in the late In the current era, democratisation and the indigenous rights movement have allowed. ‧ 國. 學. nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was an external imposition and previous self-identification was based at the village level. The indigenous identities that. ‧. subsequently came to exist were a result of the anthropological research that classified. y. Nat. them (ibid.: 55-56). The “nine tribes” model has been abandoned since 2000 and there. sit. are now fourteen officially recognised groups. Indigenous peoples in Taiwan are no. al. er. io. longer forced to accept the labels imposed on them by outsiders. Instead they are. v. n. increasingly able to self-identify and classification is now based on an emic viewpoint.. Ch. engchi. i n U. Blundell (2001) interviews a member of the Toda group. The Toda are a group of about 1,000 people in Hualien County and are classified as Atayal or Seediq. This member of the group asserts their right to recognition as a distinct group based on their self-identification. Achieving such recognition depends on the strength of the case that the people can make to the central government. The group needs evidence of its cultural heritage as well as a claim over territory. The latter is complicated by the fact many peoples were moved around during the Japanese era and may no longer inhabit their ancestral villages. There is also the need for some consensus or agreement within the group and the interviewee in this case acknowledges this is not entirely accepted by the group. 14.

(21) Identity is not something which is static, but changes due to both internal and external influences. Tradition varies from generation to generation. For example, the documentary film Amis Hip Hop (Tsai, 2005a) shows the age-set ceremonies in the Amis speaking community of Dulan in Taidong County. The young men use the latest pop music as part of their ceremony. They are not attempting to faithfully copy the dances of the older generations, but instead to prove themselves by being more outrageous than the previous age-set. However, they are still maintaining an important tradition even if the outward forms are different. Tradition essentially means to pass on knowledge and culture. It is rooted in what bonds together the community, while the outward expressions of those bonds adapt to the time and circumstances. Amis Hip Hop shows that identity is fluid rather than fixed; it reflects both continuity. 政 治 大 is not the same as that at the river's mouth, it is part of a continuous unbroken flow. 立 Similarly the cultures of Taiwan's indigenous peoples that we observe today should be and change. It is like the water in a river. Although the water at the source of the river. ‧ 國. 學. considered in the same way. Traditional customs and contemporary knowledge overlap in present day Taiwan. The age-set ceremonies in Dulan show this as do the. ‧. people of Smangus who draw upon both the gaga (Atayal traditional law) and modern. y. Nat. technology and ideas.. sit. Christianity is also linked to indigenous identity in Taiwan. In indigenous villages. er. io. throughout Taiwan the church usually occupies a prominent position. This is often a. al. n. v i n C U to Taiwan with the Dutch and speaking mainstream in Taiwan.hChristianity e n g c hfirsti came marker that distinguishes indigenous towns and villages from those of the ChineseSpanish in the seventeenth century. The Pingpu converted to Christianity whole. villages at a time in the 1860s and 1870s. They sought to ally themselves with foreign powers who they perceived as more powerful than the Qing regime (Brown, 2004: 5152). Mountain villages converted to Christianity on a large scale in the 1950s (Harrison, 2001: 76). Christianity is now seen as “a universal symbol of pan-Taiwan aboriginalism.” Indigenous peoples have appropriated Christianity as a symbol of power introduced from the West to help cope with the impacts of Chinese colonisation. It has become a symbol distinguishing indigenous people from those of Chinese heritage in Taiwan (Hsieh, 1994b: 194-195).. 15.

(22) Stainton (2002) describes the role that the Presbyterian Church has played in the support of indigenous peoples and their rights. Unlike their Catholic counterparts, all indigenous Presbyterian Churches have indigenous people serving as ministers. They preach a Christianity that is indigenised and incorporates many of the structures and functions of traditional culture. For many indigenous people religious and ethnic identity are overlapping constructs. Conversion was a means of deepening rather than changing identity. In the 1970s the Presbyterian Church began to preach about and promote the rights of both Hoklo-speaking Taiwanese and indigenous people against the KMT rule. The church resisted oppressive government policies by denouncing them as violations of God-given human rights.. 治 政 In the early 1980s, before a broad based political movement 大of indigenous peoples 立 under the same government system as all emerged, indigenous peoples lived 2.4 Indigenous rights movement in Taiwan. ‧ 國. 學. Taiwanese. The KMT dominated all political institutions and there was no organisation at the national level or of a single ethnic group that acted as a pressure. ‧. group or represented indigenous interests. There was a growing sense of relative economic depredation among indigenous peoples. Culturally there was a sense of lost. Nat. io. er. pluralism or the promotion of new ideas (Chiang, 2004: 40-41).. sit. y. identity amongst the educated. Martial law discouraged the expression of cultural. al. The 1980s and early 1990s were a period of intense political and social change in. n. v i n Taiwan as the nation emerged from C Martial Law to become h e n g c h i Ua democracy. This change reverberated among Taiwan's indigenous peoples. Taiwan missed out on the decolonisation process that took place in the 1950s and 1960s because of the Chiang Kai-shek's influential role in the United Nations and US support for his regime in the fight against Communism. When Taiwan began to democratise in the 1980s this was also the moment when international and transnational legal institutions were developing ways of promoting group rights. Both the Taiwan independence movement and the indigenous rights movement were able to tap into this discourse and activity to promote their rights and agendas (Simon, 2007: 234). Chiang (2004: 33) refers to an “energetic surge of ethnic awareness” among the Austronesian-speaking indigenous peoples. Hsieh (1994a: 408) refers to a “pan-ethnic 16.

(23) identity movement among Taiwan aborigines.” Concerned about the future of their people, young indigenous intellectuals united to search for a new identity and to enhance their power. The publication of the Gao Shan Qing magazine in 1983 and formation of the Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines (ATA) in 1984 are recognised as the starting points of the modern indigenous rights movement in Taiwan (Chiang, 2004: 41-42; Hsieh, 1994a: 408-410). The ATA was founded on 29 December 1984. It was the first pan-ethnic organisation of indigenous peoples made up mostly of intellectuals and graduates of Christian schools. In its early years it focused on opposition to policies of assimilation, criticising the Forestry Department, accusing Han people of invading indigenous peoples' lands and asking for land in the cities for urban indigenous people. In 1987. 政 治 大 1987 the ATA released a “Manifesto of Taiwan Aborigines”. Six of the seventeen 立 articles were related to land and territory. The demand for recognition of territory was. the group's focus shifted much more to the issues of land and territory. On 26 October. ‧ 國. 學. based on consciousness of rights the indigenous peoples should naturally have (Hsieh, 1994a: 410-412).. ‧. Although the movement developed in this period, it failed to challenge the power of. y. Nat. the KMT and the incumbent elites the KMT supported. Members of the movement. sit. contested elections, but were unable to win. They were seen as being a group of elites. er. io. without people (ibid.: 413-414). The strength of the KMT in indigenous communities. al. n. v i n C h opposed various to the present the Church has strongly e n g c h i U policies of the KMT and more. is further illustrated by looking at the case of the Presbyterian Church. From the 1970s. recently has been strongly linked to the DPP. In the 1970s many clergy and church elders were KMT members. This was necessary for the benefits it offered through. patronage, even though the church met with state repression and actively campaigned against the state for rights. In 1998 the DPP recruited two Presbyterian ministers to run for seats in the Legislative Yuan. Even though every indigenous Presbytery passed resolutions supporting them, both men lost. Furthermore the centrality of the church in the indigenous movement has weakened groups that are independent of the church. They, along with the DPP, often fall back on the church rather than develop independent organisational networks (Stainton, 2002).. 17.

(24) Hsieh (1994a: 413-415) says there were at least three elements limiting the ATA's capacity to expand its influence. First, the KMT and the state1 had firm control over the ethnic administration in indigenous communities. Second, the indigenous peoples are dispersed geographically throughout Taiwan. Third, there are many different ethnic groups that speak mutually unintelligible languages. Although many indigenous peoples can speak Mandarin, the concept of an ethnic political movement was not easily understandable for those peoples with different cultural traditions and languages living in dispersed locations. The resistance movement did however have the effect of making the existing elites who were connected with the KMT become more outspoken. They started to criticise unreasonable government policies and discrimination towards indigenous peoples.. 政 治 大 1990 the desire for self-government had moved into the indigenous mainstream and 立 become an orthodoxy (Stainton, 1999: 423). The idea of self-government was a The idea of “self-government” developed during the period from 1987 to 1990. By. ‧ 國. 學. utopian ideal, but it provided a way for indigenous peoples in Taiwan to regain power over their lands and livelihood (ibid.: 433). There are many practical problems related. ‧. to actually implementing indigenous autonomy, but it represents an aspiration of the. y. Nat. peoples to reclaim their sovereignty and control over land and resources.. sit. I-Chiang's 1991 statement to the United Nations in Geneva highlights some of the key. er. io. issues facing indigenous peoples as Taiwan emerged from martial law. Indigenous. al. n. v i n Ch under the control of the KMT and Chinese-speaking i U They were denied basic e n g c hpeoples. peoples were deprived of proper political participation as the political system was legal rights such as being able to register their own name. Outsiders undertook. development projects on indigenous lands without consent and indigenous peoples were economically marginalised (Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines, 1995). Through the 1990s the indigenous rights movement was unable to achieve its goal of autonomy but it made other important gains. Indigenous peoples were formally recognised in the constitution. These changes included reserved seats in the Legislative Yuan and the now abolished National Assembly. The 1993 constitutional amendments replaced the word shanbao (mountain compatriots), which indigenous 1 At this time the ROC on Taiwan was governed under a party-state system. As a result there was often little distinction between the KMT and the ROC government.. 18.

(25) peoples considered offensive, with yuanzhumin (aborigine or indigenous people). The 1993 amendments also guaranteed indigenous peoples right to political participation and government assistance for education, cultural preservation, social welfare and business undertakings. In 1997 this clause was further amended to include transportation, water conservation, health and medical care, economic activity and land (Stainton, 1999b: 430; Simon, 2007: 226). Stainton (1999b: 430) points out that the earlier amendment was general in nature, while the later amendment included matters that would be central to the formation of territorial self-government. Furthermore, Simon (2007: 226) notes that the use of yuanzhuminzu (indigenous peoples) in the 1997 amendments recognises collective rights in contrast to the previously used yuanzhumin (indigenous people) which is more concerned with. 治 政 (now known as the Council of Indigenous Peoples)大 was established in the Executive 立 Yuan. Although the powers of the Commission were severely downgraded from the individual rights in a liberal framework. In 1996 the Aboriginal Affairs Commission. ‧ 國. 學. original plan, its establishment acknowledged that Taiwan's indigenous peoples held a special position in the structure of the state (Stainton, 1999b: 427).. ‧. The most recent and substantial contribution to the field of indigenous rights in. y. Nat. Taiwan is Scott Simon's “Paths to Autonomy: Aboriginality and the Nation in Taiwan”. sit. (2007). It explores the changes in policy that took place after 2000 when Taiwan. er. io. experienced its first democratic transition of power from the KMT to the DPP. The. al. v i n indigenous rights movementC made gains under the DPP government, even h eimportant ngchi U n. DPP was the first party to pro-actively define a policy on indigenous rights. The though the KMT and its allies continued to garner a majority of the votes from. indigenous peoples. The progress made by the DPP ensures that whoever governs Taiwan in the future they will find it difficult to retract any of the rights “granted” under DPP executive rule (ibid.: 222-223). In September 1999 as part of his campaign to be elected President, Chen Shui-bian signed a “New Partnership Agreement” with indigenous representatives. It recognised indigenous peoples' natural rights and as the original owners of Taiwan. This was followed by a DPP “White Paper on Aboriginal Policy” in 2000. This paper shows the way in which aboriginal peoples were incorporated into the DPP's discourse. In many ways it was progressive, recognising that indigenous peoples had been harmed by loss 19.

(26) of territory and involuntary incorporation into the global capitalist system. The paper, written in a decolonisation framework had inherent sovereignty as a central concept. However, even though it discussed indigenous sovereignty and self-determination, the main problem was reduced to Taiwan's independence from China. The Taiwanese nation envisioned in the White Paper was made up of a wished-for alliance of indigenous peoples and “New Taiwanese”. The DPP's definition of “New Taiwanese” differed from that of Lee Teng-hui and Ma Ying-jeou which was inclusive of post1945 Chinese arrivals on Taiwan. Instead it defined it as meaning Taiwanese who were the descendants of indigenous women and male immigrants from China (ibid.: 230-232). In essence this is the Hoklo-speaking mainstream in Taiwan that makes up the majority of the DPP's electoral base. Although these people may have indigenous. 治 政 concludes, the DPP tried to incorporate indigenous peoples大 into a national imagination 立 not of their own making. Indigenous peoples were being used as part of a political ancestry they do not explicitly identify themselves as indigenous. Hence, Simon. ‧ 國. 學. discourse to construct a non-Chinese identity for Taiwan (ibid.: 232).. A number of pieces of legislation concerning indigenous peoples were passed while. ‧. the DPP controlled the executive from 2000 to 2008. The most important of these. y. discussed further in Chapter Four of the thesis.. er. io. sit. Nat. being the Indigenous Peoples' Basic Law (IPBL) passed in 2005. This will be. 2.5 Some examples in Taiwan a. n. v i l n Csome The final part of this chapter looks at cases which highlight the U h eimportant i h n c rights to land and resources. g for ongoing struggle of Taiwan's indigenous peoples Although the focus of this thesis is the Smangus community, similar cases have occurred elsewhere in Taiwan. Together these cases reflect an ongoing struggle by indigenous peoples to assert their rights and autonomy in the face of state intervention and control. The cases detailed here are all quite recent, but they need to be seen in a broader context of colonisation and settlement that dates back to the Dutch arrival on Formosa in 1624. More detail of the historical conflict between the Atayal and the state is given in Chapters Three and Four. Since the 1990s indigenous peoples have gained some rights and recognition from the government. However, the pattern of conflict between indigenous peoples and the 20.

(27) demands of capital and the state to gain control over lands and resources continues. Chi (2001) looks at the position of Taiwan's indigenous peoples from the perspective of environmental justice. Taiwan's political and economic system makes indigenous communities vulnerable to exploitation by the dominant Chinese-speaking mainstream. This directly attacks the rights of indigenous peoples to land and resources. A case that provides an example of how Taiwan's indigenous peoples suffer as a result of their economic marginalisation is the nuclear waste dump on Orchid Island2. The Yami (Tao) people of Orchid Island are somewhat isolated from the Taiwan mainland. They have experienced the least interference from outsiders of any of Taiwan's indigenous groups. The Japanese kept Orchid Island as a living anthropological. 政 治 大 significant changes on the island. In 1980 Taipower Company began constructing 立 what they told the locals was a fish cannery on the island. However, in 1982 it was. museum. It was not until the 1960s that the Taiwan government began to implement. ‧ 國. 學. discovered the site was a storage facility for nuclear waste (Arrigo, 2002). In 1987 after martial law was lifted the Yami began actively protesting against the. ‧. presence of nuclear waste on their island. In 1994 the Taipower Company agreed to. y. Nat. stop shipping nuclear waste to the island, although the storage facility was at full. sit. capacity by that time anyway. The payment of compensation to the residents of the. n. al. er. io. island created further problems with inappropriate infrastructure developments (ibid.).. i n U. v. The nuclear waste still remains on Orchid Island although the government is currently. Ch. engchi. seeking an alternative storage site.. The Truku people in Hualien traditionally occupied the mountain areas that now make up the Taroko National Park. They were pushed out into the foothills during the Japanese era and then to the base of the mountains by the ROC. In 1968 the ROC government began a system of registering Aboriginal Reserve Land. Loopholes in the law were exploited to allow non-indigenous Taiwanese to rent the land. Asia Cement took advantage of these loopholes to rent land from the Truku people in Hsiulin Township with the promise that it would be returned in 20 years. When the people 2 Orchid Island, or Lan Yu as it is known in Chinese, is currently the most commonly used name for the island. In the language of the Yami people it is Pongso no Tao. The island is also known as Botel Tobago.. 21.

(28) tried to reclaim their land after 20 years they found their property rights had disappeared. The Truku people began a long political and legal struggle to win back their land rights. In August 2000 they won a court case recognising their right to cultivate the land (Simon, 2002). The creation of the Taroko National Park in 1986 further excluded the Truku people from their traditional territory. Previously considered as part of the Atayal group, the Truku won official recognition as a separate group in January 2004. In 2004 the government put out tenders for commercial development of the Park without consulting the traditional owners. The response from the Truku caused the government to halt the bidding process. The Truku put forward a proposal for autonomy in 2006 in accordance with their rights under the IPBL. However, this has not been achieved and. 政 治 大. needs additional legislation, especially the Indigenous Autonomous Area Law which. 立. is still to be passed (Tsai, 2006). 3. ‧ 國. 學. Danayigu Ecology Park in Chiayi County, provides a successful example of ecotourism run by an indigenous community which has enabled the people to reclaim control over their traditional territory. The construction of a road into the area in the. ‧. late 1970s brought more visitors and the exploitation of fish in the river by outsiders.. y. Nat. This led to the collapse of the traditional systems the Tsou had used to manage fishing. sit. stocks. This eventually led to a grassroots response by the local community to protect. er. io. the environment. This effort had two key aspects. The first was implementing local. al. n. v i n C h form of tourismUto allow all the community second was economic development in the engchi regulations that could be enforced voluntarily by members of the community. The to gain some benefit from the fishing ban (Tang & Tang, 2001).. There are cultural and ecological costs associated with the development of Danayigu. These are associated mainly with the large numbers of tourists arriving in the area. A romanticised version of Tsou culture is presented to Taiwanese tourists in the form of traditional clothing and dance. This raises the question whether a restrictive model of cultural identity has been imposed on the Tsou or is it a positive reinforcement of cultural traditions that helps them resist the influx of global culture. Traffic from tour buses brings pollution and the roads are susceptible to landslides. These things harm 3 Hipwell (2007) uses the spelling Tanayiku. The Chinese name of the nearest village is Shanmei.. 22.

(29) agricultural crops and the harvesting of bamboo also detract from the pristine environment that attracts visitors to the area (Hipwell, 2007). Although there may be some costs associated with the development of Daniyigu, the overall outcome seems positive. Tang and Tang (2001) say that the Tsou of Danayigu have been able to attain negotiated autonomy based on mutually beneficial relationships with external stakeholders. Hipwell (2007) says that Danayigu represents a process of geopolitical resistance by the Tsou. Danayigu was devastated by the torrential rains associated with Typhoon Morakot in August 2009 bringing the community's experiment in ecotourism to an end. The Alishan Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) case provides a recent example of a case where the IPBL has proved to be ineffective. In June 2008 the Forestry Bureau and the. 政 治 大. Council of Agriculture announced the right to operate the Alishan Forest Railway had. 立. been transferred to the Hungtu Construction Company. The BOT project gave the. ‧ 國. 學. company the right to take over operations of the publicly owned mountain railway and undertake related development projects. These included plans for constructing new hotels and other improvements to the line. Under the terms of the contract the. ‧. company would return the railway and associated projects to the government after 30. y. Nat. years. A number of local groups, including the Tsou people, are opposed to the project. sit. because of concerns about its safety and impact on the local environment and. n. al. er. io. communities (Tsai, 2008).. i n U. v. The Tsou people said the project ignored their 30 year struggle for land rights. In 1976. Ch. engchi. a fire forced the people to relocate from the area near Jhaoping Station and they were never allowed to return. This land has now been allocated to Hungtu Corporation to construct a hotel in the BOT project. This is in contravention of Article 21 of the IPBL which states, “The government or private party shall consult indigenous peoples and obtain their consent or participation, and share with indigenous peoples benefits generated from land development, resource utilization, ecology conservation and academic researches in indigenous people’s regions”(Ministry of Justice, 2005). The Tsou claim neither the government or the Hungtu Corporation consulted with them prior to going ahead with the BOT project. The Tsou demand that the Forestry Bureau and company negotiated with the local people to develop a co-management. 23.

(30) mechanism (Tsai, 2008). The damage caused by Typhoon Morakot (2009) has created uncertainty over the future of the BOT project. The Smangus Beech Tree Incident provides a further example of indigenous peoples struggle for rights to land and resources. These rights are in theory protected by Articles 19 and 20 of the IPBL and Article 15 of the Forestry Act. This is examined in more detail in Chapter Four.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 24. i n U. v.

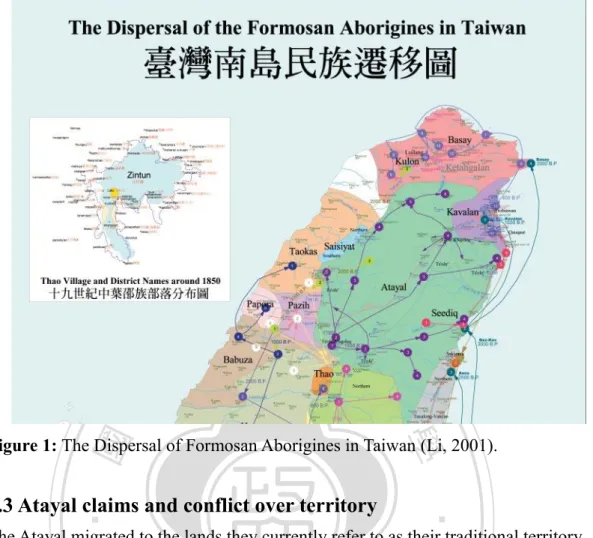

(31) CHAPTER THREE – ATAYAL CULTURE AND SMANGUS 3.1 Atayal people This thesis is based on a study of the Atayal community of Smangus. There is a need to define who the Atayal people are and to understand the broader context of Atayal culture before looking in more detail at Smangus. While Smangus shares many things in common with other Atayal communities, it also has some unique features. It is important to note that Atayal are defined based on the ethnographic present. The following quote from Kaneko expresses the dynamics of change and is worthwhile keeping in mind whilst reading this chapter.. 政 治 大. The written sources present the data as static entities, frozen in time and space.. 立. The dynamics of change which must have been at work in even this. ‧ 國. 學. conservative society through internal development and inter-ethnic and intraethnic contacts, fusions and dispersals in the course of the expansion process, and caused tangible divergences from the “norms,” are not visible in these. ‧. sources (Kaneko, 2009: 250).. sit. y. Nat. The Atayal group was originally defined by Japanese ethnographers based on their. io. er. field studies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The people are also known as Tayal or Daiyan, from the word in their own language for people. The. n. al. i n U. v. Atayal were one of the “nine tribes”, although this model of categorisation was. Ch. engchi. abandoned in Taiwan following the government's official recognition of five more indigenous groups between 2001 and 2008. The Truku and Seediq were formerly classified as part of the Atayal group. In 2004 the Truku were recognised as a separate group (Ko, 2004). Then in 2008 the Seediq also gained official recognition (Shih & Loa, 2008). Hence many references to Atayal in the literature from the twentieth century may also include the Truku and Seediq groups. All these groups can be considered to share some characteristics (Hsieh, 1994b: 186) and they all speak Atayalic languages. The Atayal population was 92,000 in the 2000 Census making up 23.1% of Taiwan's indigenous population (Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 25.

(32) 2002), however this was before the Truku and Seediq were separately classified. The Atayal traditionally live in the mountainous areas of Nantou, Taichung, Miaoli, Hsinchu, Taoyuan, Taipei, Yilan and Hualien counties. Many Atayal may have moved temporarily or permanently to major urban areas for work or education. How this has affected Atayal identity is a topic that needs further research. This thesis focuses on Atayal speakers who still live on their traditional territories. (Traditional territory is defined later in this chapter.). 3.2 History and culture of the Atayal The Atayal have been through many changes in the past century. At the beginning of the Japanese era they lived in small communities that were self reliant and they were. 治 政 lost their position. However, in present day Taiwan the Atayal 大are experiencing 立 their culture and reasserting their rights to something of renaissance, rediscovering. the only masters of their land. They were conquered by the Japanese in the 1920s and. ‧ 國. 學. manage land and natural resources.. Atayal people have historically lived in the mountains at altitudes above 1,000 metres. ‧. (Kaneko, 2009: 250). They migrated into the mountainous areas of northern Taiwan about 250 years ago (Li, 2004). (More details of the migration are given later in this. y. Nat. sit. chapter.) However, they have no ethnic memory of life other than in the high mountain. er. io. valleys to which they are fully adapted. They practiced swidden agriculture growing. al. millet, dry rice, beans and root crops. They also added to their diet by hunting and. n. v i n fishing. Millet was not only a stapleC part of their diet but had h e n g c h i U religious and cultural significance (Kaneko, 2009: 249-250).. Takekoshi (1996: 219-222) provides a description of the Atayal in the early Japanese era. This was a time when the Japanese had yet to establish control over the mountain areas and the indigenous peoples living there maintained their autonomy. He notes the Atayal were “extremely ferocious” and “attach great importance to head-hunting”. They lived in small tribes which were like one family under the patriarchal rule of a chieftain. The core belief of the Atayal is the gaga. This is a set of rituals and prohibitions inherited from the ancestors and held by the elders within patrilineal clan groups. The. 26.

(33) clan group that shares the same rituals and prohibitions is known as the qotux gaga (Kaneko, 2009: 252). The gaga is an all-embracing concept for the Atayal and it regulates almost all aspects of Atayal affairs (Piling Yapu, 2009a: 70). Atayal culture has been described as “acephalous, closed and dominated by rigid standards of conduct.” However, the migration from the homeland, aided by the adoption of firearms, which allowed the expansion of the Atayal into new territory shows that there must have been considerable adaptive flexibility. Gradual adaptation to new locations led to the development of new gaga. The knowledge contained in the quotux gaga was important as it was specialised to the environment in which the community lived. At high altitudes small differences in elevation or location could mean significant changes in the dates of specific agricultural activities Hence the. 政 治 大 maintain their agricultural systems in the high mountain environment (Kaneko, 2009: 立 253).. knowledge contained in the gaga was highly specialised and essential for the Atayal to. ‧ 國. 學. The Atayal believe that humans have an immortal spirit known as the utux. After death the utux leaves the body and sets out on a journey. The journey ends at the rainbow. ‧. bridge (hogo utux) where the ancestral utux are waiting at the other end. The utux is. y. Nat. requested to provide proof that they have lived according to the gaga, making them a. sit. true Atayal. For a man this means being a brave headhunter, for a women a skilled. er. io. weaver (ibid.: 254). Kaneko details the mortuary practices of the Atayal based on field. al. n. v i n C h by the Japanese and associated rituals were abolished e n g c h i U in the 1920s (ibid.: 252-278). studies in the 1950s and 1960s and Japanese historical records. The in-house burial. Facial tattooing is a distinctive feature of Atayal culture. Although this practice was eradicated by the Japanese in the 1930s, there are still a few elders surviving with facial tattoos. These elders offer a window to the past. Being tattooed marked coming of age and once men or women received tattoos they were able to marry. The tattoos also symbolised recognition by the community that a person was a true Atayal. It was necessary to obtain the approval of all community members in order to receive the tattoo. For men this meant proving themselves as a hunter, for women it meant skill in weaving. The facial tattoos represent “gaga on the face” and the diamond pattern represents the ancestral spirits. They are a bridge for communication between humans. 27.

數據

Outline

相關文件

21 Article 6(x): Where the financial sector is unduly protected from normal commercial and financial risks, serious prejudice in the sense of paragraph (c) of Article 5 shall

(四)雇主申請僱用獎助前,未依身心障礙者權益保障法及原住民

Article 40 and Article 41 of “the Regulation on Permission and Administration of the Employment of Foreign Workers” required that employers shall assign supervisors and

shall be noted. In principle, documents attached by the employer shall be affixed with the seals of application unit and owner. The application and list shall be affixed with

(4) A principal selection committee shall select in an open, fair and transparent manner a suitable person for recommendation under section 57 from candidates nominated in an open,

(4) A principal selection committee shall select in an open, fair and transparent manner a suitable person for recommendation under section 57 from candidates nominated in an open,

面向東南亞,尋求區域合作的價值與意義。如今當我們面對台灣原住民的「民族數學」研究時,尤其

IQHE is an intriguing phenomenon due to the occurrence of bulk topological insulating phases with dissipationless conducting edge states in the Hall bars at low temperatures