民族運動之結構與論述:蘇格蘭與法蘭德斯 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 2. Abstract 這篇論文研究歐盟兩個國家裏面的民族主義運動:蘇格蘭在英國與法蘭德斯在比 利時。這篇論文最重要的目標是研究這兩個政治運動的論述。更仔細來説,我們 想知道這兩個運動是否使用道德性的論點來説服選民。再加上此論文研究政治論 述與結構之間的關係。理論方面本文使用 David Miller 的 On Nationality。. Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………….2. 政 治 大. (1) Chapter One: General Introduction…………………………….………………....4. 立. (2) Chapter Two: Theory and Methodology………………………………………….6. ‧ 國. Literature Review………………………………………...……………6 A.. The Literature on Scotland and Flanders………………………...9. ‧. II.. 學. I.. Definitions……………………………………………………..……..11. y. Nat. io. sit. III. Theory: David Miller and Béland & Lecours………………….….....15. n. al. er. IV. Methodology…………………………………………………………22. Ch. i n U. v. A.. Discourse and Content Analysis………………………………..23. B.. References to Structural Conditions………………………….…25. C.. Assessing the Relevance of Representations of the Nation as an Ethical Community……………………………………………..26. engchi. (3) Chapter Three: Scotland……………………………………………...…………..28 I.. II.. Introduction……………………………………………………..……28 A.. Political Background……………………………………………28. B.. Linguistic and Cultural Situation……………………………….30. C.. Social Policy Development…………………….……………….32. Analysis of Discourse………………………………………………...35.

(3) 3. A.. SNP Discourse 1997-1999: The 1997 Referendum and General Election, and the First Scottish Parliamentary Election of 1999..36. B.. SNP Discourse 2001-2011: Hiatus from Ethical Social Policy Discourse and the Double Scottish General Election Victory….43. C.. SNP Discourse 2012-2013: Return to the 1990s Discourse for The Independence Referendum……………………………….……..50. D.. Summary..……………………………………………………....56. (4) Chapter Four: Flanders……………….………………………………………......60. A. B.. Linguistic and Cultural Situation………………….……………65. C.. Social Policy Development………………………….………….65. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Analysis of Discourse…………………………………………...……67. io. y. N-VA Discourse from 2003-2007: Early Days and Electoral Alliance…………………………………………………………71. al. n. B.. Discourse Pre-2003: The Evolution of the Flemish Nationalist Political Agenda towards Social Policy…………………...……68. Nat. A.. sit. II.. 政 治 大 Political Background……………………………………………60 立. Introduction…………………………………………………………..60. er. I.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. C.. N-VA Discourse from 2009-2014: Going at it Alone and Electoral Success……………………………………………………...…..81. D.. Summary..………………………………….…………….……..87. (5) Chapter Five: Conclusion…………………………………………….……..……91 Bibliography……………………………………………………………….……..97.

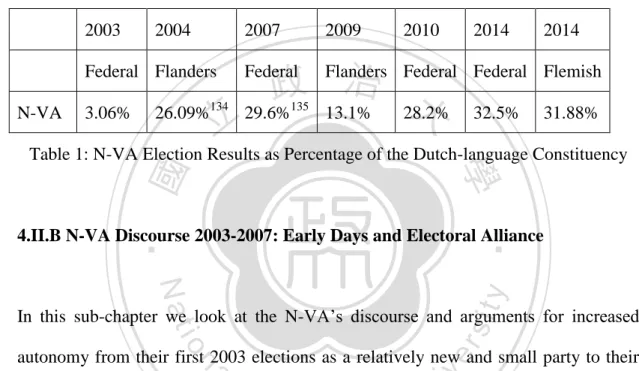

(4) 4. 1. Chapter One: General Introduction Nationalism is alive and well. Even in today’s globalised world. Indeed, even in the prime example of liberalism’s promise: the European Union. Regional nationalist movements are closer than ever to splitting up countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and Belgium. These movements persist and in some cases even grow more salient, despite the fact that authors such as Ernest Gellner have famously predicted the disappearance of nationalism after the Second World War. So how and why do some nationalism movements persist towards the end of the twentieth and. 政 治 大 minority rights not assuaged the fundamental nationalist demands for representation, 立. beginning of the twenty-first century? Have consociationalism, federalism and. the continuation of the national culture and recognition of the national language? In. ‧ 國. 學. our two case studies, Scotland and Flanders, this sure seems to be the case. After all,. ‧. they are both located in consolidated liberal democracies with extensive devolution of. y. Nat. powers, central representation and cultural rights. So why is it that these movements. er. io. sit. persist and continue to grow despite the fact that the nationalists’ traditional concerns have been assuaged? How can further our understanding of the fact that a large. al. n. v i n C h regions seems toUrespond to nationalist attempts proportion of the electorate in these engchi at mobilisation? The thesis will aim to answer these questions by looking into an aspect of national identity which seems to be overlooked in many of the field’s most influential theories: the idea of the nation as an ethical community. By looking at what nationalists claim about those aspects of national life with the most ethical character, social policy, the thesis will endeavour to ascertain whether the nationalists in our case studies are engaging in the representation of the nation as an ethical community. Based on the political salience and electoral support given to these nationalist actors we may then draw some meaningful conclusions with regard to the relevance of such representations..

(5) 5. The structure of the thesis will be as straightforward and lucid as possible. After engaging in a literature review to preface the research, we will briefly indicate where the current body of literature drops the ball on the cases we have selected; and introduce the theoretical framework and methodology. Thereafter, we will engage in two detailed case studies which will each consist of two major sections: an introduction of the political, cultural and social policy background of the case, and the analysis of nationalist discourse. Finally, we will conclude with a brief comparison of the cases and implications for nationalism studies.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(6) 6. 2. Chapter Two: Theory and Methodology 2.I Literature Review The cases of nationalism under scrutiny in this thesis, Scotland in the United Kingdom and Flanders in Belgium, were not selected to feature in this study by chance. They were chosen due to their shared relevance in challenging the traditional canon of literature on nationalism. From a reading of this literature, it becomes obvious that the great classical authors on the subject have not managed to satisfactorily explain the rise and persistence of nationalism in the cases at hand.. 政 治 大 There are several great scholars in the field of nationalism. One of these is the Marxist 立. historian Eric. J. Hobsbawm. In his two most influential works, The Invention of. ‧ 國. 學. Tradition (1983) and Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. ‧. (1990), he emphasises the role of political transformations. Hobsbawm views nations. sit. y. Nat. and nationalism as products of social engineering. The traditions on which the image. io. er. of the nation is built are elements which use history as a legitimator of action and cement of group cohesion.1 Indeed, these invented traditions are responses to new. n. al. Ch. situations which are based on references to old. engchi. v i n situations U. which are instilled in. citizens through primary education, public ceremonies, and mass production of public monuments.2 It is, according to Hobsbawm, through these means that nationalism becomes a substitute for social cohesion through a national church, some royal family. It has the potential to become what he dubs ‘a new secular religion’.3. 1. Umut Ozkirimli, The Theories of Nationalism, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 94.. 2. Ibid, 95.. 3. Ibid, 95..

(7) 7. Another great scholar of nationalism, Ernest Gellner, formulated his major theory in 1983. His description of nationalism can be captured in two major definitions. First, Gellner described nationalism to be a political principle which holds that the national and political units should be congruent.4 This is a definition which the thesis will hold as corresponding with the study in question. His second, more detailed, definition goes “nationalism is, essentially, the general imposition of a high culture on society, where previously low cultures had taken up the lives of the majority, and in some cases the totality, of the population … It is the establishment of an anonymous,. 政 治 大 above all by a shared culture of this kind.” This is a stage that the cases in question 立 impersonal society, with mutually substitutable atomised individuals, held together 5. have long surpassed, however, the general description of the situation is not too far off.. ‧ 國. 學. The problems arise in his 1996 revision and prediction towards the future. The fifth. ‧. and last stage of nationalism as described by Gellner is the post-industrial stage since. sit. y. Nat. 1945 where we are supposed to find a high level of satiation of the nationalist. io. er. principle, accompanied by general affluence and cultural convergence, leads to a diminution of the virulence of nationalism.6 This stage seems to have come and gone. al. n. v i n C h War. In the pastUdecades if anything we find a since the end of the Second World engchi. renewed spread, salience and support for nationalism, particularly sub-state nationalism.. Scholars like Anthony D. Smith combine primordial beginnings with modern functionalism in ethnosymbolism, which argues that myths and symbols that arose in. 4. Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 2006), 1.. 5. Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, 57.. 6. Ibid, 112..

(8) 8. antiquity are used today as ways of sustaining the nation. 7 According to Smith the “third wave of demotic ethnic nationalisms” since the 1950s is specific to the political-cultural conditions of the well-established industrial states to which they belong. They are considered by Smith as ‘autonomist’ rather than ‘separatist’, and he claims they emphasise cultural, social and economic autonomy within the political framework of the state they are part of.. Another famous modernist is Benedict Anderson, who, in his book Imagined Communities (Anderson, 1982), stresses the importance of the printing press in the. 政 治 大. mass dissemination of discourse which constructs of national identities and rousing. 立. people to serve their nations. Anderson is one of the few scholars on nationalism who,. ‧ 國. 學. despite indicating the nation is imagined, does not give a negative judgment on nationalism. To summarise Anderson’s argument on the rise of nationalism, one has. ‧. to keep in mind three important elements: a change in the conceptions of time, the. y. Nat. sit. decline of religious communities and dynastic realms, and the emergence of. al. n. never having met.8. er. io. print-capitalism which allows for people to imagine a national connection despite. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Michael Hechter, in his turn bases his approach on the ‘internal colonialism’ thesis. He argues that an exploitative and unequal relationship develops between periphery and core in such a way that the internal colony produces wealth for the benefit of areas closer to the core-state.9 The internal colonies are differentiated by particular. 7. Daniele Conversi, "Mapping the Field: Theories of Nationalism and the Ethnosymbolic. Approach,"Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations, ed. Athena S. Leoussi, Steven Grosby (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 21. 8. Umut Ozkirimli, The Theories of Nationalism, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 110. 9. Michael Hechter, Containing Nationalism, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 71..

(9) 9. cultural variables such as religion, language or ethnicity which exclude them from the superior positions. He goes on to argue that there is usually a cultural division of labour whereby the peripheries have low-status occupations and the core gets the high-status ones. Nationalism develops as a reaction to this concentration of power and resources at the centre. Hechter identifies three major conditions for group solidarity (which leads to nationalism) to occur. First, there needs to be sufficient economic disparity between individuals so that these individuals may view this inequality as unjust and a form of oppression. Second, as individuals have to. 政 治 大 And third, there needs to. recognise this oppression collectively, there is a need for sufficient communication within the oppressed group.. 立. be sufficient cultural. distinctiveness between periphery and core. In each case the maxim ‘the more. ‧ 國. 學. inequality, communication, or cultural difference; the more likely nationalist. Nat. io. er. 2.I.A The Literature on Flanders and Scotland. sit. y. ‧. mobilisation against the core’ applies.10. All of these approaches, however influential, share one drawback: they fail to account. al. n. v i n C nationalist sub-state where h e n g cmovements hi U. for the persistence of. these have already. assuaged linguistic, cultural, territorial and institutional concerns.. Indeed, as can be seen from his work, Gellner has little to say about sub-state nationalism, let alone modern sub-state nationalism. With regard to Scotland he merely mentions that the rise of nationalism there is contingent and instrumental, set. 10. Ozkirimli, Theories, 81..

(10) 10. off by the discovery of oil in the sea surrounding the Scots. Flanders and Catalonia are not at all mentioned and Quebec warrants but a passing mention.11 Smith, as mentioned in the literature review, views modern cases of sub-state nationalism as autonomist, not separatist, however the movements represented by the parties we discuss in the thesis, both the Scottish National Party and New Flemish Alliance have independence as their ultimate goal. Additionally, their discourse lacks the “cultural, literary, linguistic and historical”12 elements stressed by Smith. Hechter’s theory does not completely explain our cases either, Flanders as it is the. 政 治 大 and can economically be considered the ‘core’. Scotland for its 立. wealthier region, has higher GDP per capita and more highly educated workers than the rest of Belgium. 13. part is culturally and linguistically very similar to the rest of the UK. 14 And it has. ‧ 國. 學. many arguments that are based on Scotland’s oil wealth, rather than its relative. sit. y. Nat. rest of the UK.15. ‧. poverty, as its relative GDP per capita has reached a level comparable to that of the. io. er. Anderson, does make mention of the Scottish case, but is more interested in the failure of nationalism to take off in the nineteenth century than in their success in the. n. al. late twentieth and twenty-first.. Ch. 16. engchi. i n U. v. 11. David McCrone, The Sociology of Nationalism, (London: Routledge, 1998), 126.. 12. McCrone, The Sociology, 126.. 13. Eurostat, "General and Regional Statistics: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at Current Market Prices. by NUTS 2 Regions." Last modified March 03, 2014. Accessed June 5, 2014. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=nama_r_e2gdp&lang=en. 14. Michael Keating, Nations Against the State The New Politics of Nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia. and Scotland, (New York: Palgrave, 1996), 165. 15. Eurostat, “General and Regional Statistics”. 16. McCrone, The Sociology, 125..

(11) 11. Lieven de Winter, on the other hand, has examined the effect proportional representation may have on the electoral success of nationalist parties, finding that it seems more likely to dampen nationalist support.17 However, our two cases studies have enjoyed proportional representation for several decades, yet nationalist mobilisation in the form of electoral support seems to be on the rise.. Indeed, the cases selected have all reached post-industrial levels of development, have all been given some form of representation and self-government, and are set in states. 政 治 大 and development. The questions this thesis will ask are: What can help account for the 立 with different levels of cultural and linguistic diversity, and relative economic wealth. continued successful nationalist mobilisation? And what is the role of representations. ‧ 國. 學. of the nation as an ethical community? This is what the thesis will aim to find out, and. ‧. an analysis of nationalist discourse in the cases of Scotland and Flanders has the. sit. y. Nat. potential to provide us with an answer.. al. n. Nation or State?. er. io. 2.II Definition of the Terms. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Before we can embark upon the theoretical part of the journey, we first need to take a closer look at the confusion between ‘nation’ and ‘state’. In everyday speech ‘nation’ is often used as a synonym for state: for example, when someone refers to ‘newly developing nations’, they are more likely referring to states.. This usage is not exactly helpful when attempting to make useful statements about nationalism as it is discussed here, since one of the main issues we are dealing with. 17. Lieven de Winter, chap. 2 in Regionalist parties in Western Europe, ed. Lieven de Winter Huri. Tursan (London: Routledge, 1998)..

(12) 12. here is precisely the relationship between nations and states, and in particular the question of how a nation may strive to have its own state. When this question is posed, ‘nation’ must refer to a community of people with “an aspiration to be politically self‐ determining, and ‘state’ must refer to the set of political institutions that they may aspire to possess for themselves.”18. For example when we follow Weber’s statement that a state is a body that successfully claims a monopoly of legitimate force in a particular territory, we count. 政 治 大 multinational, in the sense that they claim a monopoly of legitimate force over several 立. states by checking how many such bodies there are.19 Some of these states will be. different nations. These are the cases that will be the focus of this thesis. The United. ‧ 國. 學. Kingdom is such a state; rather unusually, it is often referred to by public and. ‧. politicians alike as ‘the family of nations’. (This family includes England, Wales,. sit. y. Nat. Scotland, and Northern Ireland.) Rather less common are cases where one nation is. io. er. divided between two states. This was the case for the Germans before the reunification of 1990, and is still the case for the Koreans today. A third case occurs. al. n. v i n C h are scattered Uas minorities nationality engchi. where people of a single. in a number of. states—the position today of the Kurds in modern Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria. None of this would make sense if we did not understand ‘nation’ and ‘state’ in such a way as to make it an empirical question whether those who compose a nation are all united politically within a single state.. The confusion of nation and state is a common enough mistake encouraged by ordinary usage. The confusion of nationality and ethnicity, on the other hand, is more 18. David Miller, On Nationality, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 19.. 19. Max Weber, Politik als Beruf, (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1992), 4..

(13) 13. understandable, because here we are dealing with phenomena that are essentially of the same general type. Both nations and ethnic groups are bodies of people bound together by common cultural characteristics. However, there is a clear distinction made in contemporary literature. Put simply the ethnic group is defined more often than not by common descent, whereas the nation – as employed here – will be understood in a much less obviously visible way. A full and detailed definition of the nation will be provided below.. 政 治 大 group, similar caution has to be applied when considering nationalism. Again, in 立. Following from our careful distinction between nation and state, and nation and ethnic. everyday speech people tend to view nationalism exclusively in relation to states,. ‧ 國. 學. much like patriotism such as in the common misconception that nationalism or. ‧. patriotism in the United States is matter purely related to the Weberian state and its. sit. y. Nat. institutions. In yet other instances the confusion between nation and ethnicity is the. io. er. cause of confusion, for example in the case of the Serbian nationalism of figures like Slobodan Milošević, who in fact define the ‘nation’ ethnically. Anthony Smith has. n. al. Ch 20. dubbed this ‘ethnic nationalism’ .. engchi. i n U. v. In the study at hand, however, neither of these usages quite defines what we are after. After all, seen as the cases we will be discussing below are ‘nations’ as explained above (and as will be defined more clearly a little later), we need to understand nationalism as a phenomenon relating to nations as such. Patriotism on the other hand, will be taken to mean a feeling of affection or commitment to the state one is a member of. 20. Shu Yun Ma, "Ethnonationalism, Ethnic Nationalism, and Mini‐nationalism: A Comparison of. Connor, Smith and Snyder," Ethnic and Racial Studies, 13, no. 4 (1990): 527-541..

(14) 14. A third term that tends to cause confusion both in scholarly literature and common speech is ‘separatism’. Separatism refers more clearly to the intended goal of the movement described as such: complete separation from the state and thus the foundation of a new state. In this thesis we will use the word separatism as a possible characteristic of nationalist movements. Nationalist movements are by no means necessarily separatist, they could just as well be less radical in their demands. Generally, there are two terms used for these less radical denominations: autonomism and regionalism. These two concepts are very similar and appear to be used. 政 治 大. interchangeably in most of the literature.. 立. Social and National Citizenship. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. In this thesis we will take national citizenship to mean culturally, civically or. sit. y. Nat. territorially defined ‘belonging’ to a nation. Put differently, national citizenship. io. er. pertains to cultural elements such as language, national symbols, traditions, or arts and crafts. But it also pertains to purely civic elements such as a constitution, a flag or. al. n. v i n nationalCcitizenship also entails h e n g c h i U territorial. civil society. Finally,. belonging which. simply refers to the ‘homeland’ with all its particular geographic or natural characteristics.. Social citizenship, on the other hand, will be defined as it was coined by T.H. Marshall: “the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilised being according to the standards prevailing in society”21. More concretely,. 21. Thomas H. Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class (London: Pluto Press, 1950), 14..

(15) 15. this means the set of socio-economic rights and obligations held by members of the community, which pertain to instruments such as taxation, social benefits, social services. In the scope of the thesis social benefits and services will include income-maintenance. programmes. (such. as. pensions,. disability,. child. and. unemployment benefits), health care, public housing, and social care.. 2.III Theory. 政 治 大 movements and tensions in Europe seem to persist despite the fact that the concerns 立. The goal of this thesis is to shed light on as to why and how sub-state nationalist. generally described by the literature as being nationalists’ most fundamental concerns. ‧ 國. 學. have already been assuaged. The search for an answer to this question leads us. ‧. beyond most of the existing explanations. As is clear from a glance at the literature. sit. y. Nat. review, scholars of all manner of persuasions have formulated different theories on. io. er. what nationalism is and how it works. However, when we engage in an evaluation of each theory's applicability and explanatory merits in the selected cases, it becomes. n. al. Ch. obvious that a fresh approach is needed.. engchi. i n U. v. In today’s Europe there are some regions that characterise themselves as being culturally or linguistically different from the state they are a part of. Based on these cultural differences, a proportion of the population and politicians in this region would claim they are more than a mere ‘region’; they are a ‘nation’. Examples hereof are places such as Brittany, Flanders, Scotland, Bavaria, Wales, Catalonia, the Basque Country, and so on..

(16) 16. Among these ‘nations’ we find different degrees of cultural distinctiveness. And, according to most of the traditional literature, those nations that are most ‘different’ or have the strongest cultural identity, are most likely to be nationalist and demand some form of political autonomy. 22 Additionally, nationalist mobilisation is generally explained to occur in reaction to threats to national identity as such. However, when we take a closer look at some of the nationalisms found in Europe today, we find some cases, in which there is little linguistic diversity or cultural difference in the narrow sense of the word; while in other cases the rights of linguistic and cultural. 政 治 大 tension within these states has not faded away. Indeed, in some cases tensions have 立. identity are already constitutionally guaranteed. However, the sub-state nationalist. increased and nationalist movements have gained strength and increased electoral. ‧ 國. 學. support. So the question is: why do these nationalist struggles for autonomy persist,. ‧. despite the fact that traditional nationalist concerns have been assuaged?. sit. y. Nat. io. er. This study will argue that some sub-state nationalist struggles persist because many nations’ national identities and representations of national identity do not merely. al. n. v i n C hlinguistic, culturalUand territorial elements; but in include the traditionally described engchi. some cases are also perceived to include ethical elements. These ethical elements describe distinctiveness in an ethical dimension. That is to say that they represent the nation as an ethical community as explained by David Miller in his book On Nationality.. Miller argues that nations can be ethical communities in the sense that aside from deriving distinctiveness from common cultural practices (such as language), shared. 22. Umut Ozkirimli, The Theories of Nationalism, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 81..

(17) 17. belief and mutual commitment, being extended in history, being active in character, and occupying a particular territory; nations may also mark themselves off from other communities through sharing particular interpretations of what we owe our fellow nationals. Miller describes the nation as an ethical community in which members “recognise duties to meet the basic needs and protect the basic interests of other members”23. Indeed, in Miller’s view, each nation has a distinct public culture which determines “a set of ideas about the character of the community which also helps to fix responsibilities.” 24 For Miller this implies that in acknowledging a national. 政 治 大 members of the nation which one does not owe to other human beings. 立. identity, one is also acknowledging that one owes special obligations to fellow 25. This either. because they are simply not part of the nation or because they have a different idea of. ‧ 國. 學. what obligations are owed. This means that different nations can have different ideas. Nat. sit. y. ‧. about the kinds of obligations owed to fellow members.. io. er. Interpretations of the obligations owed to co-nationals can be fulfilled in any number of ways. In modern industrialised countries, obligations are most commonly fulfilled. al. n. v i n C h After all, socialUpolicy entails the actions that by means of different social policies. engchi. affect the well-being of members of a society through shaping the distribution of and access to goods and resources in that society.26 Ideas on social policy are said to be contained in interpretations of social citizenship. Social citizenship, defined as it was coined by T.H. Marshall, means: “the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage 23. David Miller, On Nationality, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 83.. 24. Miller, On Nationality, 68.. 25. Ibid, 49.. 26. Christine Cheyne, Mike O'Brien, and Michael Belgrave,Social Policy in Aotearoa New Zealand: A. Critical Introduction, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 3..

(18) 18. and to live the life of a civilised being according to the standards prevailing in society” 27 . More concretely, this means the set of socio-economic rights and obligations held by members of the community, which pertain to socio-economic instruments such as taxation, redistributive programmes such as unemployment benefits and family allowances, all manner of social services, pensions, education, health care, criminal justice and public transport. In short, the aspects of policy primarily concerned with human wellbeing and welfare.. 政 治 大 which in turn inform social policy preferences. More concretely, they help shape 立 Interpretations of obligations owed determine conceptualisations of social citizenship,. (among other things) different nations’ ideas on social policy and the limits of the. ‧ 國. 學. welfare state. For example, public opinion in different nations may have a distinct. ‧. idea of when a jobless person should receive unemployment benefits; or to which. sit. y. Nat. extent a richer co-national’s income should be taxed. To mention two extreme. io. er. examples, US public opinion seems to prefer limited government interference in the social economy and emphasises individual freedom and private initiative; whereas in. al. n. v i n C hopinion favours strong a country such as Sweden public government regulation and engchi U involvement in society and the economy as a way of ensuring equality.. By connecting traditional elements of nationality such as territory, history, culture, or language to understandings of social citizenship, nationalists are injecting an ethical element (what obligations one should fulfil) into the definition of nationality. They are representing the nation as an ethical community.. 27. Thomas H. Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class (London: Pluto Press, 1950), 14..

(19) 19. This nationalist injection of an ethical element into nationality is something seen less in national politics of fairly homogenous, unitary states. Instead, we can expect to see more ethical representations of the nation in multi-national states. Particularly, when two or more interpretations of social citizenship clash within one multi-national state, at least one of the groups in question is likely to feel they are being cut a ‘bad deal’. Indeed, they might even feel they need increased political autonomy in order to satisfy their conception of social citizenship; or in Gellner’s words to obtain congruence between the national and political unit. 28 It is at this point that the connection. 政 治 大. between ideas of social citizenship and nationality and the expression thereof become particularly relevant.. 立. After all, if interpretations of obligations owed to co-nationals in the shape of a. ‧ 國. 學. specific conceptualisation of social citizenship can be said to be part of national. ‧. identity, and this element of national identity is compromised (or perceived as such),. sit. y. Nat. sub-state nationalist politicians may be able to mobilise support on this basis, even if. io. al. n. safeguarded.. er. all the other elements of national identity have already been legally or institutionally. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. This last element is one that can be found in the work by Béland and Lecours in their 2008 book Nationalism and Social Policy: The Politics of Territorial Solidarity. In their study the authors examine several central claims about the nexus between nationalism and social policy by looking at three case studies: Quebec, Scotland and Flanders. Several of their claims are useful for the thesis’ research objectives. We will use these claims as a means of testing the nationalist discourse and employ them as a barometer to indicate the presence or absence of arguments relating to. 28. Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, 3..

(20) 20. conceptualisations of social citizenship; and thus the representation of the nation as an ethical community.. First, the thesis will gauge if social policy at any point becomes a major component of the effort of nationalist movements to build and consolidate national identity, and an important target for nationalist mobilisation.29 Although the relevance of social policy is less evident in nationalist politics than traditional markers of national identity such as culture and language, the thesis’ theoretical understanding is that it. 政 治 大 citizenship are used and. may be substantial. The thesis will establish if, like culture and language, conceptualisations of social. 立. viewed as markers of. distinctiveness and exclusiveness.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Second, as Béland and Lecours note “the focus of nationalist movements on social. sit. y. Nat. policy is not simply the product of economic self-interest, yet references to the. io. er. fairness of financial transfers between territorial entities become effective mobilisation strategies.”30 Although, some nationalist discourse may refer to actual. al. n. v i n C h in economic U structural differences, the differences interest are not necessarily the engchi. main driving force behind nationalist politics. Unlike what some traditional materialist and Marxist theories on nationalism seem to suggest.31 In order to test this, the thesis will look for references to fairness and justice in nationalist discourse. After all, references to such concepts would be indicative of an ethical characterisation rather than one of economic interest.. 29. d and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 23.. 30. Ibid, 25.. 31. For a full account of the major theories, see Umut Ozkirimli, Theories of Nationalism (Basingstoke,. UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 72-82..

(21) 21. A third and final statement lies close to the words used by Miller: “It is intrinsic to the nature of contemporary (sub-state) nationalism that it puts forward claims about the existence of a national unit of solidarity where co-nationals have a special obligation to each other’s welfare, a situation viewed as being best fulfilled by having control over social policy.”32 This essentially boils down to the representation of the nation as an ethical community. In order to verify the presence of such claims, the thesis will investigate if nationalism and social policies are framed in function of solidarity. 政 治 大 this specific sense and definition of obligation or solidarity into institutional duties, 立. within the national community. The goal for nationalists would be, then, to transform. rights, and redistribution.33 Put differently, the goal is to attain congruency between. ‧ 國. 學. the national community of obligation and the formal social policy schemes that put. Nat. sit. y. ‧. this solidarity into practice.. io. er. To reiterate, based on the theoretical understandings above, the thesis suggests that the presence of these three claims in the nationalist discourse to be analysed indicates. al. n. v i n that the nationalists in question C are in fact attempting U h e n g c h i to depict the nation as an ethical. community. This, together with their substantial electoral support, would seem to signify that some nations do view their national identity as incorporating an ethical element. And, moreover, this would seem to suggest that even if the traditional markers of national identity have already been safeguarded, the fact that the ethical aspect of national identity is compromised merits and allows for nationalist mobilisation.. 32. Beland and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 26.. 33. Ibid, 26..

(22) 22. 2.IV Methodology As stated earlier, the thesis’ main goal is to explore to why and how some sub-state nationalist movements and tensions in Europe seem to persist despite the fact that the concerns generally described by the literature as being nationalists’ most fundamental concerns have already been assuaged. The thesis’ theoretical understanding suggests that some nationalist movements continue to persist (or even grow) because there is an element to their national identity which they perceive as compromised by the state. More specifically, an ethical element which is concerned with the kinds of obligations. 政 治 大. deemed to be due by the nation as a community (formulated by elites and electorally. 立. affirmed by voters). In practice this would mean that there is a perceived discrepancy. ‧ 國. 學. between the obligations pursued in the existing social policy system and the obligations deemed relevant by the ‘nation’.. ‧. In order to establish the discursive ‘presence’ of an ethical community – covering at. Nat. sit. y. least the nationalist politicians in question and their supporters – we will analyse. n. al. er. io. nationalist discourse to see if it contains three particular nationalist claims relating to. i n U. v. social policy, informed by conceptualisations of social citizenship. Where present, the. Ch. engchi. representation of the ethical community will be considered to have some relevance as soon as they are subscribed to – implicitly or otherwise – by a substantial proportion of the electorate. This because the nationalists’ demands continue to be salient despite the fact that their traditional concerns of language and cultural rights have already been assuaged. It could therefore be said that the nationalists succeed in mobilising a significant proportion of the electorate, among other things, with their depiction of the ethical community as being compromised. All this will be done by means of content analysis of election manifestos of nationalist political parties. Additionally, the thesis will consider structural elements relating to social policy issues..

(23) 23. The study will consider data and events between 1997 and 2014. The year 1997 is a good base year due to the inclusion of many institutional – mostly decentralisation – that took place since then in the regions under scrutiny.. 2.IV.A Discourse and Content Analysis The discursive section of the study will in each case examine the major political parties and civil society organisations. The political parties will include the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA, Nieuw-Vlaamse. 政 治 大 campaign, we will consider their white paper on independence with regard to the 立. Alliantie). Additionally, as the SNP was and remains active in the Yes Scotland. upcoming referendum.. ‧ 國. 學. The phenomenon of nationalism is too complex to be taken at face value in a classical,. ‧. purely positivist quantitative content analysis approach. Language does not only have. sit. y. Nat. the ability to reflect social reality, it can also play a part in constructing it (Berger and. io. er. Luckmann, 1966). This holds particularly true in the case of the nation and nationalism (Sinardet and Morsink, 2014). Therefore, this thesis will opt for. al. n. v i n C h content analysis qualitative content analysis. Qualitative does more than merely count engchi U. words or extract objective content from texts. It allows us to examine meanings, themes and patterns that may be manifest or latent in political discourse with constant reference to the social, political and economic context in which the discourse was produced. As such we can keep track of the mutually constitutive to and fro of agency and structure – discourse and social reality. A qualitative approach will enable us to understand social reality in a subjective but scientific manner (Wildemuth and Zhang, 2009). Additionally, this method is more suitable for capturing the fundamentally ethical notions of obligation, justice, and fairness found in two of our three claims..

(24) 24. More specifically, the thesis will be using Philipp Mayring’s method of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2000; 2010). The advantage of Mayring’s approach is that it retains the advantages of quantitative content analysis such as pre-set rules of analysis, employing a clear model of communication, having categories (derived from our three theoretical claims) at the centre of the analysis, and the possibility to check for reliability and validity. However, essentially qualitative steps are added to deal with quantitative content analysis’ disconnection from context and weakness in justifying or explaining categories (Krippendorf, 1980). In particular the dual use of. 政 治 大 great potential to contribute to the study’s uniqueness of understanding. Firstly, main 立 inductive and deductive category development will be a qualitative method which has. categories and their definitions are formulated based on the theoretical background. ‧ 國. 學. and the research question. Then, the materials fitting these categories are analysed,. ‧. and where necessary the categories and/ or their definitions are revised and adapted.. sit. y. Nat. As the thesis will be employing qualitative analysis of the discourse, the units of. io. er. analysis are themes. As mentioned these themes will initially be selected deductively based on indications found in literature on nationalist movements and their discourse. al. n. v i n C h1995; Leith 2000).USpecial attention will be paid to (Béland and Lecours 2008; Miller engchi discursive elements referring to our three main claims. Each claim spawns several. themes which ascertain the presence of its essential message, but also at least one theme which would contradict the claim.. 1. Social policy may become a major component of the effort of nationalist movements to build and consolidate national identity, and an important target for nationalist mobilisation:34 reference to social policy, redistributive programmes,. 34. d and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 23..

(25) 25. public health care, education, criminal justice, social services, and issues of proportional representation in the central government. 2. “The focus of nationalist movements on social policy is not simply the product of economic self-interest, yet references to the fairness of financial transfers between territorial entities become effective mobilisation strategies”: 35 the fairness of financial transfers between territorial entities, and relative economic prosperity of the region. 3. “It is intrinsic to the nature of contemporary (sub-state) nationalism that it puts. 政 治 大 co-nationals have a special obligation to each other’s welfare, a situation viewed 立 forward claims about the existence of a national unit of solidarity where. as being best fulfilled by having control over social policy”:36 definitions of. ‧ 國. 學. solidarity, region specific socio-economic ideology, social policy preferences,. n. al. er. io. 2.IV.B References to Structural Conditions. sit. y. Nat. autonomy.. ‧. socio-economic values specific to the region, and regional economic interest in. i n U. v. Seen as we are also interested in the social, political and economic context in which. Ch. engchi. the discourse was produced, we will, where relevant, be analysing certain structural characteristics of the regions in question. Particularly important in this regard are elements such as government expenditure on social welfare (income-maintenance programmes and health and social services) on the one hand; and the structure of the economy (number of businesses to population ratio, proportion of government employees) on the other hand. But also certain realities of the political context may be. 35. Ibid, 25.. 36. d and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 26..

(26) 26. quoted to clarify the dominance or recurrence of certain themes in nationalist discourse. 2.IV.C Assessing the Relevance of Representations of the Nation as an Ethical Community As we would like to draw inferences with regard to the role of the representation of the nation as an ethical community (through the articulation of conceptualisations of social citizenship and thus obligations owed), we also need ways of assessing the relevance of these representations. This will be done by observing the popular and. 政 治 大 support for the parties who produce the ethical discourse. Generally speaking this will 立 political salience given to such discourse, more concretely by looking at the electoral. mean taking stock of the election results of these parties in the different elections. ‧ 國. 學. covered by the periods under scrutiny.. ‧. It is important to understand that the thesis does not focus on public opinion.. y. Nat. sit. Although we pay attention to public opinion in the form of election results, our. n. al. er. io. discussion about alleged ‘national values’ is centred on the discourse of nationalist. i n U. v. actors, which is not necessarily consistent with detailed public opinion data. What. Ch. engchi. matters most in this study is what nationalists say about national values and whether or not the public responds to them. This thesis is primarily about nationalism and nationalist mobilisation. Although it is clear that, in some cases, public opinion and socio-economic data does not confirm nationalist claims about the distinctiveness of their community, what matters to us is that politicians make these claims to begin with; and if and how they manage to mobilise popular support for their nationalist objectives despite the fact that the traditional elements of national identity have already been safeguarded..

(27) 27. Equally important to note is that this thesis does not claim to provide a comprehensive explanation of why some nationalist movements are more successful than others. Instead, we attempt to inform the issues of nationalism and nationalist mobilisation from a perspective of less well-known nationalist concerns such as ethical elements of national identity relating to social citizenship and social policy.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(28) 28. 3. Chapter Three: Scotland 3.I Introduction 3.I.A Political Background Scotland is one of the clearest cases of a stateless nation. As one of the early European states it secured its own monarchical and parliamentary institutions in favour of annexation by the English crown. Scotland maintained its autonomy until 1603 when the Scottish king James VI succeeded Queen Elizabeth I of England, thus uniting the crowns. Over a century later, in 1707, the two nations’ parliaments were. 政 治 大 consolidating Scotland and. also united creating a single state. Each side had its reasons to support the Union. The English were concerned with. 立. prevent any possible. Jacobite or French plots against England; whereas the Scots saw the Union as an. ‧ 國. 學. economic opportunity. After all, the Union would secure free trade with England and. ‧. a chance to expand together with the growing empire. Ever since 1707 Scottish. sit. y. Nat. nationalists have stressed that a great deal of bribery and intrigue needed to convince. io. the move.. al. er. the Scots parliament to vote its own adjournment in the face of popular opposition to. n. v i n C hone. Great BritainUis neither a unitary state nor a The result was a rather unorthodox engchi. federation, but a so-called ‘union state’.37 Despite having a unitary parliament, many elements of Scottish civil society and administration were retained including Scots law (at least for private law), the local administration system, and the educational system. Scotland currently has fifty-nine seats in the House of Commons out of a total of 650. Since 1998, however, the Scots have had a Scottish Parliament of their own – often referred to as the Holyrood – which has extensive authority over policy areas such as education, agriculture, the environment, health, local government, and justice. 37. Stein Rokkan, and Derek Urwin, Economy, territory, identity: Politics of West European peripheries,. (London: Sage Publications, 1983), chap. 1..

(29) 29. The Holyrood has 129 seats and the Scottish Government has 10 cabinet and 11 junior ministers. The Members of Scottish Parliament are elected through the additional member system. There are three major UK-wide political parties active in Scotland: the Scottish Conservatives, Scottish Liberal Democrat Party, and Scottish Labour. Additionally there are several parties that are only active in Scotland most importantly there are the Scottish National Party, the Scottish Greens, and the Scottish Socialist Party. Scotland’s heightened sense of national identity became political again starting from. 政 治 大 to explain this. First, there is the expansion of the state’s role in the everyday 立 the second half of the nineteenth century. Two important factors are generally quoted. economic and social issues; this posed the question of a Scottish administration.38. ‧ 國. 學. Secondly, there is the Irish Home Rule movement which gained the support from. ‧. Prime Minister William E. Gladstone in 1886, which put the Scottish issue on the. y. Nat. map.39 Initially, the Scottish home rule movement was associated with the radical. er. io. sit. wing of the Liberal Party, the Highlands’ land reform movement, and the industrial labour movement. Rising tensions were at their highest point right after the First. al. v i n C hthe cross-party Scottish As a consequence, Home Rule Association engchi U n. 40. World War.. from 1886 was revived in 1918. Despite parliamentary debates and votes, no progress. was made, and in 1922 the issue, once again, disappeared from the public eye. This was partially due to Labour and the unions’ renewed focus on class-related issues, and the Liberal Party’s political decline.41 The home rule movement’s frustration with the traditional parties became clear when in 1934 the Scottish National Party (SNP) was 38. Michael Keating, Nations against the state : the new politics of nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia,. and Scotland, (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 1996), 170. 39. Ibid, 170.. 40. Ibid, 170.. 41. Ibid, 170..

(30) 30. founded. Although the SNP’s share of the Scottish vote rose steadily from 1964 until 1974, no significant results were achieved throughout their golden decade. It wasn’t until the SNP’s breakthrough election result in 1974 that Labour was forced to organise a referendum a few years later on the question of a Scottish assembly. The 1979 referendum on devolution did not meet the required level of forty per cent support among the whole electorate – a requirement added at the last minute, but was nonetheless a turning point. As frustration among nationalists rose, the 1980s saw Thatcher and the Tories elected with minority support in Scotland. This contributed to. 政 治 大 Labour’s choice for Tony Blair as their new leader in 1994 is widely viewed as a 立. the growth of territorial sympathies in Scotland and around the UK.42 Furthermore,. move away from the Scottish image towards one more acceptable to southern English. ‧ 國. 學. voters.. ‧. Overall, the loss of empire eliminated a first element of shared identity, thus exposing. y. Nat. the weakness of British national identity. The weakening of Protestantism in a secular. er. io. sit. age is considered the demise of a second element of Britishness.43 The vacuum was swiftly filled by an ever stronger sense of Scottish national identity.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 3.I.B Scottish Language and Culture. Scotland harbours two indigenous languages Gaelic and Scots. Scottish Gaelic was isolated from Irish Gaelic in the fifteenth century and, although never reaching all of Scotland, is still widely spoken in the western Highlands. According to the 2011 Census only 1.1 per cent of the population of Scotland can speak Gaelic.44 Officially,. 42. Ibid, 172.. 43. Ibid, 172.. 44. National Records of Scotland, "2011 Census: Key Results on Population, Ethnicity, Identity,. Language, Religion, Health, Housing and Accommodation in Scotland - Release 2A." Last modified.

(31) 31. the language is not recognised as a national language in the United Kingdom (unlike Welsh), but the Scottish Parliament passed the 2005 Gaelic Language Act, founding a Gaelic language development body. The so-called BòrdnaGàidhlig may require Scottish public bodies and cross border bodies implementing carrying out devolved functions, to provide their services in Gaelic. Scots, on the other hand, is a Germanic language linked to English and was the official language of courts and law before the Union. After losing much of its prestige to English in the eighteenth century never really developed to the point of reaching ausbau status, in other words, although Scots. 政 治 大 never achieved full usage in literary, scientific and technical functions. 立. is sufficiently different from English to be considered a separate abstand language, it 45. Despite. being used in poetry and daily use by some, today Scottish people mostly identify. ‧ 國. 學. only with their distinct pronunciation of the English language. In fact, according to. sit. y. Nat. thus ceased to be a marker of Scottish nationality …”46. ‧. Michael Keating, as the two ‘Scottish’ languages made way for English, “language. io. er. Despite language being a less important part of Scottish nationalism, Scotland does have a strong cultural identity.47 In pre-Union Scotland the Highlands had a Celtic. al. n. v i n C h had its own variant and Gaelic tradition, and the Lowlands of Anglo-Saxon culture. In engchi U. the sixteenth century the Calvinist Reformation added elements not commonly found in the rest of Britain. Although Highland dress was banned for some time after the Union, it was revived and disseminated to the rest of Scotland by nineteenth century romanticism as tartanry and the iconic kilt. These sartorial elements are now found around Scotland and Scottish diaspora in military traditions, ceremonial occasions, September 26, 2013. Accessed June 6, 2014. http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/documents/censusresults/release2a/StatsBulletin2A.pdf. 45. Keating, Nations Against, 165.. 46. Ibid, 165.. 47. Ibid, 189..

(32) 32. but also in everyday dress. Another element of the Scottish cultural revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century concerns the kailyard school of literature. Kailyard authors such as Ian MacLaren, wrote sentimental popular literature depicting a wholesome, small-town Scotland free of the problems brought on by industrialisation. The same period also saw less stereotypically Scottish cultural production by greats such as Robert Burns and Walter Scott, followed by their twentieth century colleagues George Douglas Brown and McDougall Hay. However, it wasn’t until the 1980s that a renaissance of indigenous culture coincided. 政 治 大 be made between culture and nationalism. Initially, theatre companies such as 7:84 立 with the revival of nationalist sentiment. It was at this time that connections began to 48. and Black Cat, novelists – most notably James Kelman; and rock bands such as. ‧ 國. 學. Runrig and the Proclaimers, used their art to set social issues in a specifically Scottish. ‧. context. Since then culture has entered the political arena. The world-famous. sit. y. Nat. Edinburgh Festival has come under pressure to be more Scottish by including more. io. er. Scottish acts and providing Scottish side entertainment as such profiling itself as a Scottish festival combining Scottish and global culture. A similar discussion arose. al. n. v i n C h City of Culture inU1990. when Glasgow was elected European engchi 3.I.C General Development of Social Policy. The first decade of the twentieth century saw the birth of the British welfare state under Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Liberal). In 1908 the first foundation was laid out with the passing of the non-contributory Old-Age Pensions Act which protected the elderly poor. Three years later, in 1911, the National Insurance Act created contributory social insurance schemes covering parts of the population of the. 48. Keating, Nations Against, 189..

(33) 33. United Kingdom against sickness and unemployment. 49 Throughout the interwar period Westminster generally seemed to favour a significant yet gradual expansion of social policy. For instance, the Widows, Orphans and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act of 1925 covered all workers, aside from those who were enrolled in possibly more generous occupational schemes. Although there were improvements in the areas of social housing and unemployment benefits, the schemes did not cover all UK citizens. Consequently, pre-World War II British social policy did lay the foundation for a comprehensive social security system, but did not yet constitute an identity. 政 治 大 It was, however, not until Sir William Beveridge published his 1942 report entitled 立 building level of social protection.50. ‘Social Insurance and Allied Services’, that the idea of universal coverage was truly. ‧ 國. 學. considered. In his wartime report Sir Beveridge advocated the construction of a. ‧. unified social welfare state covering all UK citizens, thus protecting them against the. sit. y. Nat. five main social problems he identified to exist at that time: idleness, ignorance,. io. er. disease, squalor, and want. Although the plans were not considered for implementation until after the war, the immense Labour victory in the general election. al. n. v i n of 1945 brought about a wave C of social and economic h e n g c h i U reforms, giving shape to the modern British welfare state as we know it today. Most importantly, these reforms. included far-reaching nationalisation – of gas, electricity, railways, aviation, road transport, steel and coal, and the Bank of England – and the creation of the three main components of the British welfare state: the 1946 National Insurance Act and National Health Service Act, and the 1948 National Assistance Act. These three major pieces of legislation made for a complete overhaul of social policy in the UK. The old. 49. George Peden, British economic and social policy : Lloyd George to Margaret Thatcher, (New. York: P. Allan, 1991), chap. 2. 50. Ibid, chap.2..

(34) 34. fragmented system was replaced by the centralised National Insurance system, run by a ministry and operated from small, local branches all over the country. Additionally, there was the National Health Service (NHS). This organ, financed mainly through general taxation, provided free medical and hospital care to British citizens. According to the constitutional logic of the union-state, Westminster had to pass separate legislation to create the NHS Scotland, administered by the Scottish Office. However, as the system was completely created and funded by the central London administration, the social citizenship in question consisted of social rights and. 政 治 大 Moreover, a range of other social measures such as public housing, cash benefits, and 立. obligations defined in a British context; and granted and enforced by the British state.. the old-age pension further contributed to the spread of a distinctly British social. ‧ 國. 學. citizenship.. ‧. Important to note here is the use of the word ‘national’ in each of the major social. sit. y. Nat. policy organs. The loss of the empire and the superpower status that came with it. io. er. meant the loss of an important aspect of British national identity. The role of the British national social policy instruments has been, purposefully or otherwise, to. al. n. v i n C hsocial meaning to UBritish citizenship. Indeed, the provide political, symbolical and engchi new universalist welfare state created distinctly British institutions that impacted the. everyday life of the Scottish populace.51 First, British social policy created a system in which Scots and the rest of the United Kingdom would share similar economic, political and social interests in the functioning of the national welfare state. In other words, the construction of British universalist social programmes caused the social fates of Scottish people and the people of the other nations became increasingly intertwined. Second, aside from the previously described process of identity-building, 51. Lynn Bennie, Jack Brand & James Mitchell, How Scotland Votes (Manchester: Manchester Univ.. Press, 1997), chapter 2..

(35) 35. the social policies of Labour after 1945 also facilitated the incorporation of the sizeable Scottish working class population into post-empire Great Britain. 52 The new-born welfare state alleviated class-related grievances and narrowed the gap between somewhat poorer Scottish and slightly wealthier English populations, thus creating mutual social and economic interests in a British context. All in all British post-war social policy is a prime example of the nexus between nationalism and social policy as described by Béland and Lecours in their first of six claims on the subject: “In developed multinational countries, both the state and at. 政 治 大 competing national solidarities and identities”. 立. least one sub-state government are likely to use social policy to foster and promote 53. ‧ 國. 學. 3.II Discourse Analysis. ‧. sit. y. Nat. In this section of the case study we engage in a detailed analysis of party discourse as. io. er. found in political and election manifestos. More specifically, the analysis will focus on instances of discourse where the political party or nationalist organisation in. al. n. v i n C hNational Party andUthe Yes, Scotland Campaign – question – in this case, the Scottish engchi establish a connection between social policy preferences or interpretations of obligations to co-nationals on the one hand, and national identity on the other hand. In other words, we are looking for discourse containing elements of our three main theoretical claims. As we go over the different documents the thesis will indicate key political, economic or other structural conditions and events possibly relevant to the. 52. David McCrone, Understanding Scotland: The Sociology of a Nation (London: Routledge, 2001),. 15. 53. d and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 19..

(36) 36. discourse. This section will cover discourse published in the period between 1997 and 2013.. 3.II.A The 1997 Referendum and General Election, and the First Scottish Parliamentary Election of 1999. On the eve of the 1997 UK General Election the issue of a referendum on the creation of legislative assemblies in Scotland and Wales was one of the major election themes. 政 治 大 Party. The Labour Party - then called New Labour – ran their campaign with Tony 立 together with NHS waiting lists, class size, and internal divisions in the Conservative. Blair as front man and fully supported referendums on the creation of legislative. ‧ 國. 學. assemblies in Scotland and Wales. New Labour won the elections with a total of 419. ‧. seats, fifty-six of which were won in Scotland. The Scottish National Party saw its. y. Nat. popularity increase slightly receiving 22.1% of the popular vote, but not winning. er. io. sit. many constituencies.54. The Scotland Forward campaign was the main organization (movement) supporting a. al. n. v i n C hpromised by Labour. double yes vote in the referendum The campaign was endorsed engchi U by the Scottish National Party, but also by Scottish Labour, the Scottish Liberal. Democrats and the Scottish Green Party. The 1997 election campaign was seen by many in Scotland as an opportunity to engage in early campaigning for the referendum. In the end, a resounding Yes-Yes vote (74.3% on the question of a Scottish assembly and 63.5% on the issue of tax-varying powers) created the Scottish Parliament.. 54. The UK system for General Elections uses a first past the post system, therefore it is possible, as in. the case of the SNP in 1997, to enjoy widespread popular support but only return six out of seventy-one seats..

(37) 37. The 1999 first Scottish parliamentary elections saw the Scottish National Party set its highest electoral score since 1974, becoming the second largest party with thirty-five of 129 seats or 27.5% of the vote, second only to Scottish Labour which managed to win fifty-six seats. This legislature gave the SNP the opportunity to come to the forefront of Scottish politics as the main opposition party and gain much needed experience in matters of governance. In the run-up to these 1999 maiden elections, the political playing field was very much open.. 政 治 大 Enterprise, Compassion, and Democracy 立. ‧ 國. 學. From the Scottish National Party manifestos of this period we can clearly distil three. ‧. main values the Scottish National Party seems to ascribe to the people of Scotland.. y. Nat. The first two values – enterprise and compassion – are widely quoted in the 1997. er. io. sit. campaign; a third value – democracy - was added to the earlier two in the SNP’s 1999 manifesto Scotland’s Party.55 Indeed, in the 1997 documentation, these values are. al. n. v i n implied to have been dominant C in Scotland at a point U h e n g c h i sometime in the past,. 56. whereas. in 1999 the complete trinity of enterprise, compassion and democracy are said to be Scotland’s “real priorities”57.. From the analysis of the manifestos it seems that the trend away from references to the past and towards references to the present and the future continues throughout the 1999 manifesto. In the 1997 manifesto we find an introduction referring to the 55. Scottish National Party, “SNP Manifesto 1997: Yes We Can, Win the Best for Scotland”,. (Edinburgh: SNP, 1997), 4; Scottish National Party, “SNP Manifesto 1999: Scotland’s Party”, (Edinburgh: SNP, 1999), 3. 56. SNP, “1997”, 4.. 57. SNP, “1999”, 7..

(38) 38. continuing historical distinctiveness of Scotland as a nation in the realms of “law, education, administration and in sport.”58 The 1999 manifesto, however, focuses, as the title suggests, more on the SNP as embodying Scottish “needs and hopes” 59 and understanding Scotland’s specific “problems and possibilities”.60 All of this seems to point at claims that Scotland is somehow socially and economically different, and therefore requires a different kind of administration and social policy.. When we take a closer look at the manifesto, we see how the Scottish National Party. 政 治 大 the text even contrasts Scottish social compassion with “London” 立. appropriates the value of compassion as an intrinsically Scottish value. Sometimes, 61. , “Westminster”,. “Tory” (Conservative)62, or even “New Labour”63 policies, which are represented as. ‧ 國. 學. being incompatible with Scottish values and society. Of course, in the light of the. ‧. recent socio-political history this is not at all strange. The memory of the recent. sit. y. Nat. Conservative government under Major, but especially the 1979-1990 Thatcher. io. er. government, was still fresh in Scotland. Without ever gaining anything close to a majority of the vote in Scotland (between ten and twenty-two seats out of a total of. al. n. v i n C htwo consecutive U seventy-one Scottish MPs), these Tory governments had enacted engchi. policies of privatisation and retrenchment that were especially painful in Scotland, with its large public sector and unionised, over-manned industries, and above average unemployment. 64 The Scottish Office, which was created to adapt Westminster 58. SNP, “1997”, 6.. 59. SNP, “1999”, 1.. 60. Ibid, 1.. 61. SNP, “1999”, 3.. 62. SNP, “1999”, 4.. 63. SNP, “1999”, 3.. 64. Earl A. Reitan, The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair and the. Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979-2001 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 151..

(39) 39. policies to the Scottish context, was unable to do more than merely slow down the implementation of Thatcherite policies concerning health care and public housing.65 According to Béland and Lecours it was to some extent Thatcherism which “triggered a sense of social injustice and institutional vulnerability…”66 Thatcherism had the effect of laying bare the difference in socio-economic reality, needs, and preferences which existed between Scotland and England. An effect which, as this thesis will strive to point out continues to resound to this day.. 政 治 大 policy preferences we find on pages twelve and thirteen of the 1997 manifesto entitled 立. The most poignant example of appropriation of ‘social’ or even politically left core. Yes We Can. Win the Best for Scotland. In these pages the manifesto lists a number of. ‧ 國. 學. policies under the header “Working in a Better Scotland”, including full employment,. ‧. a reduction in business taxes, modernisation of transport and communications. y. Nat. infrastructure, introduction of a minimum wage, and higher taxation for higher. finishing this list, the manifesto states:. n. al. Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. incomes accompanied by tax cuts for low and middle income earners 67 . Upon. i n U. v. “These proposals are in keeping with the basic Scottish belief in progressive taxation and the sharing of responsibility according to the ability to pay.”68. 65. Nicola McEwen, “The Nation-Building Role of State Welfare in the United Kingdom and Canada”,. in Trevor C. Salmon & Michael Keating (eds.), The Dynamics of Decentralisation: Canadian Federalism and British Devolution, (Montreal/ Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Univ. Press, 2001), 76. 66. d and Lecours, Nationalism and Social Policy, 118.. 67. SNP, “1997”, 12-13.. 68. SNP, “1997”, 13..

(40) 40. This excerpt represents a prime example of a link being made between social or even ethical considerations on the one hand, and being Scottish on the other hand. Indeed, as is clear from this quote, the SNP goes further than simply identifying what would be beneficial for Scotland and Scottish people in particular (as opposed to what’s good for the rest of the UK or England), it explicitly connects Scots and Scotland with both a particular socio-economic policy – a system of progressive taxation – and a basic belief about who owes who what; an ethical characteristic. More specifically, Scottish people believe that those co-nationals who earn more should contribute more,. 政 治 大. and those who earn less, should have to pay less.. 立. Another aspect of the value of ‘compassion’ that is ascribed to Scotland and the. ‧ 國. 學. Scottish people, concerns the issue of poverty. The elimination of poverty through. ‧. social policies ranging from increased child benefits69 and investments in public. y. Nat. health70, to the abolishment of means testing for the elderly71 and the introduction of. er. io. sit. a cold climate allowance for purchasing domestic fuel72 is also repeated several times. This variety of social policies with the aim of eliminating poverty among young and. n. al. old is prefaced with the line. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. “Scotland in which poverty is eradicated and those in need are assisted to the maximum degree possible; the Scotland that all Scots want”73. 69. SNP, “1997”, 14.. 70. SNP, “1999”, 19.. 71. SNP, “1997”, 14.. 72. SNP, “1997”, 14 & SNP, “1999”, 20.. 73. SNP, “1997”, 14..

數據

相關文件

The first row shows the eyespot with white inner ring, black middle ring, and yellow outer ring in Bicyclus anynana.. The second row provides the eyespot with black inner ring

In this section, we consider a solution of the Ricci flow starting from a compact manifold of dimension n 12 with positive isotropic curvature.. Our goal is to establish an analogue

• One technique for determining empirical formulas in the laboratory is combustion analysis, commonly used for compounds containing principally carbon and

Teachers may consider the school’s aims and conditions or even the language environment to select the most appropriate approach according to students’ need and ability; or develop

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Students are asked to collect information (including materials from books, pamphlet from Environmental Protection Department...etc.) of the possible effects of pollution on our

In this paper, we illustrate a new concept regarding unitary elements defined on Lorentz cone, and establish some basic properties under the so-called unitary transformation associ-