Chinese EFL Learners’ Perceptions of

Grammatical Difficulty

Li-Ju Shiu

National Chi Nan University jujushiu@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper reports on the findings of the study that investigated grammatical difficulty from Chinese EFL learners’ perspectives. A questionnaire, designed to explore learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty, was administered to 277 EFL learners in two universities in the central part of Taiwan. The results indicate that Chinese EFL learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty are influenced by factors related to their second language (L2) knowledge, L2 grammar learning experience, and L1 knowledge. It was also found that learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty included reference to syntactic, semantic, and/or pragmatic levels. However, overall, this group of Chinese EFL learners perceived learning of the 20 target features at the syntactic level to be relatively easy. Notwithstanding, learners perceived syntactic features that require more extensive use of metalanguage to describe their formulation as more difficult to learn than those that can be described more simply. The finding that the learners tend to perceive grammar learning at the syntactic level to be relatively easy might be, in part, because of their years of de-contextualized, form-oriented L2 learning experience. The questionnaire findings, however, are less informative about learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty at other levels (e.g., semantic, pragmatic level) due to the limitations of its design.

Key Words: English grammar learning, learner perceptions, grammatical difficulty

INTRODUCTION

The selection of target grammatical features for second language (L2) instruction is a matter of special importance for L2 teachers and researchers (Doughty & Williams, 1998). For example, it would be helpful if teachers knew what language features are potentially more difficult for their learners as this would provide useful information as to when and how they might be taught (e.g., later in the learners’ development and/or more intensively). However, identifying which L2 grammar features are more challenging for learners is not an easy task. The second language acquisition (SLA) literature suggests that grammatical difficulty can be determined from psycholinguistic perspectives (e.g., developmental sequences) or linguistic perspectives (e.g., inherent complexity of grammatical structures). Nonetheless, while these theoretical accounts contribute to our understanding of the issue of grammatical difficulty, they are all “objective” accounts proposed by L2 theorists or researchers. Research on grammatical difficulty from the learners’ perspective is still thin on the ground. The current study is an attempt to fill this research gap by investigating the issue of grammatical difficulty from the perspective of Chinese EFL learners. Specifically, it investigates which grammatical features Chinese EFL learners perceive as easier, and which as more difficult, to learn, and why some features are perceived to be more or less difficult to learn than others. The findings of the study provide several pedagogical implications that are useful for L2 teachers in general and EFL instructors teaching in Taiwan in particular.

GRAMMATICAL DIFFICULTY AND SECOND

LANGUAGE LEARNING

The SLA literature reveals various approaches to defining “grammatical difficulty.” For example, Krashen (1982) puts forward an intuitively appealing idea of “easy rule” and “hard rule,” but fails to make the distinction explicit. Green and Hecht (1992) distinguish easy rules from hard rules by the extent to which the rules can be articulated. DeKeyser and Sokalski (1996) and Berent (1985) consider grammatical difficulty in relation to comprehension and production. They argue that some grammar structures are easy to comprehend, but difficult to produce, whereas others are easy to produce, but difficult to comprehend. Larsen-Freeman (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999; Larsen-Freeman, 2003a, 2003b) discusses grammatical difficulty in terms of linguistic form, semantic meaning, and pragmatic use. According to Larsen-Freeman, a grammar feature can be easy with respect to one aspect, but difficult with respect to another. For example, the form of the English passive is easy to learn, but its use is more difficult for learners.

DeKeyser (2003) distinguishes objective difficulty from

subjective difficulty. Objective difficulty concerns the linguistic

factors that contribute to the learning difficulty of the structures in question. Subjective difficulty, on the other hand, takes individual learner differences into consideration. One example of objective difficulty is to determine grammatical difficulty in relation to the inherent complexity of rules; that is, the more complex the rules of a grammar form are, the more difficult they are for L2 learners to learn (Housen, Pierrard, & Van Daele, 2005; Hulstijn, 1995; Hulstijn & de

Graaff, 1994). DeKeyser (2003) defines subjective difficulty as, “the ratio of the rule’s inherent linguistic complexity to the student’s ability to handle such a rule” (p. 331). In this regard, “what is a rule of moderate difficulty for one student may be easy for a student with more language learning aptitude or language learning experience” (p. 331). One example illustrating subjective difficulty is to determine grammatical difficulty from L2 learners’ perspectives (Scheffler, 2009).

Still other researchers have characterized grammatical difficulty in terms of students’ correct use of the features (e.g., Ammar & Spada, 2006; Doughty & Varela, 1998; Spada, Lightbown, & White, 2005; Williams & Evans, 1998). Grammar features are considered more difficult to learn if many students have difficulty using them correctly. For example, the learning of the third person possessive determiner (his/her) is considered difficult for Francophone students learning English as an L2 because it has been frequently observed that the students tend to have difficulty using the feature correctly (Ammar, 2008; Lyster, 2004; Lyster & Izquierdo, 2009; J. White, 1998). Another example is English past tense -ed. It has been observed that accurate use of this feature is problematic for many L2 learners (Ellis, 2007; Ellis, Loewen, & Basturkmen, 2006; McDonough, 2007).

Grammatical difficulty has also been discussed in relation to the degree of salience of forms in the input. Based on the presumption that attention plays an essential role in L2 learning (e.g., Doughty, 2001; Long, 1996, 2007; Swain, 2005), L2 researchers argue that the more salient a form is, the more likely it is to be noticed and processed, and consequently acquired. Salience of a grammar form is often discussed with reference to the “accessibility” and “availability”

of the target form; the former is primarily contingent upon various linguistic attributes of the form, while the latter concerns the frequency of the form in the input to which learners are exposed (Collins, Trofimovich, White, Cardoso, & Horst, 2009; Goldschneider & DeKeyser, 2005; Skehan, 1998). According to Goldschneider and DeKeyser (2005), a grammar form would be more salient if the form is phonetically sonorous or stressed, semantically straightforward, morphologically predictable, and belongs to a syntactic category that is more easily recognized.1

L2 learners’ “developmental readiness” is another criterion used by L2 researchers to determine grammatical difficulty. The bulk of research on the acquisition of certain language structures suggests that many forms are learned in predictable stages (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 2000; Meisel, Clahsen, & Pienemann, 1981; Pienemann, 2005; J. White, 1998). Thus, it is often assumed that a feature would be difficult to learn if learners are not developmentally ready to learn it. The observation with regard to whether a feature is “early” or “late” acquired has also been used to define grammatical difficulty; features that tend to be acquired early (e.g., English progressives) are often considered to be “easy” to learn, while those that tend to be acquired late (e.g., English simple past) are often considered to be “difficult” features (Collins et al., 2009).

In addition, the more frequently a form appears in the input, the more likely it is to be noticed, and thus acquired.

“Negative transfer” resulting from L1-L2 differences may cause a certain degree of difficulty in L2 grammar learning.

Discussion of grammatical difficulty resulting from “L1 transfer” can be traced back to the 1960s. Stockwell, Bowen, and Martin (1965) proposed the notion of “hierarchy of difficulty,” which postulates that the degree of difficulty corresponds to the degree of difference between the target language and the learners’ native language, and that the more differences there are between the two languages, the more difficult the target language will be for L2 learners. Language transfer has long been a focus of discussion in the literature (e.g., Gass & Selinker, 1992; Kellerman & Sharwood-Smith, 1986; Odlin, 1989, 2003; Selinker & Lakshamanan, 1992), and the impact of L1 transfer on L2 learning has been a point of investigation in FFI studies (e.g., Izquierdo & Collins, 2008; Lightbown & Spada, 2000; Spada & Lightbown, 1999; L. White, 1991). Both theoretical accounts and empirical studies of language transfer indicate that L1 transfer may moderate the rate of L2 learning.

The foregoing discussion indicates that determining grammatical difficulty is not an easy task.

RESEARCH EXPLORING L2 LEARNERS’

PERCEPTIONS OF GRAMMATICAL DIFFICULTY

To my knowledge, Scheffler’s (2009) study is the only study that explored grammatical difficulty from L2 learners’ perspective. Scheffler investigated the effectiveness of L2 instruction in relation to grammatical difficulty from the perspective of Polish EFL learners. A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to two groups of advanced second- and third-year college EFL students (n = 50, each

group).2

Scheffler found that overall this group of Polish learners did not consider learning of the 11 target grammar areas to be difficult, although some of them were considered to be more difficult to learn than the others. The highest mean score for the 11 grammar areas is 3.5 and the lowest mean score is 2. Based on their mean scores, the 11 grammar areas are ranked (from least to most difficult) as follows: adjectives and adverbs→pronouns→nouns→articles→passive voice →reported speech → conditional sentences → modal verbs → -ing forms and infinitives→prepositions→tenses (comprising tense and aspect). According to Scheffler, these advanced L2 learners tended to perceive learning of the 11 target grammar areas to be easy because they had a good knowledge of English grammar, which were taught using an explicit P-P-P type of instruction. Scheffler speculated that The questionnaire asked one group of learners to rate the difficulty of 11 target grammar areas from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “very easy” and 5 indicating “very difficult.” These 11 areas were selected because the respondents were taught with them in their classroom instruction at the time of the study. The other group was asked to assess the effectiveness of L2 instruction that they had experienced for learning of the target 11 grammar areas. The questionnaire completed by the latter group used the same scale, with 1 indicating “not useful at all” and 5 indicating “very useful.” Because the findings regarding learners’ perceptions of the usefulness of L2 instruction are not related to the current study, only the results with regard to the learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty are discussed below.

the ranking results might be in part due to the L1-L2 (Polish vs. English) differences. However, Scheffler also noted that it was not clear to what extent the learners’ L1 might have influenced their perceptions of grammatical difficulty.

Scheffler’s study provided us with some interesting information concerning L2 learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty. However, the study has several limitations. For example, it involved only a small number of advanced EFL participants. The findings are not applicable to other L2 populations. Besides, because “grammar areas” were used in the questionnaire, it is not clear which individual grammar features that learners would perceive more or less difficult to learn when the features were placed in the same grammar area. Moreover, it remains unclear why some features were considered to be more or less difficult to learn than others. These questions deserve further investigation.

The current study is an attempt to address these questions. Following Scheffler (2009), the current study explored university-level EFL learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty by use of a questionnaire. The research questions motivating the current study are: 1. Which features of English grammar do university-level Chinese EFL learners perceive as easier, and which as more difficult, to learn?

2. Why do Chinese EFL learners perceive some of the selected features to be more or less difficult to learn than the others?

METHOD

ParticipantsThe study was conducted in two universities in the central part of Taiwan. Although it was desirable to carry out the study in more universities, due to some practical constraints (e.g., budget, time), a decision was made to carry out the study only in two universities that were somewhat advantageous for the researcher in terms of their locations. The study involved 277 EFL learners, who were drawn from seven intact English classes, including five English reading classes and two English listening-and-speaking classes. The reading and listening-and-speaking classes were primarily intended for first year students; however, senior students who had previously failed these two courses could take them as well. The selection of the classes was based mainly on the instructors’ willingness to have their class participate in the study. Four English instructors showed interest; thus, the students in the seven classes taught by these four instructors were invited to participate in this study.

To maximize the homogeneity of the sample, out of the 293 students enrolled in the seven classes, 16 were excluded. Participants were excluded if (1) they were non-first-year students, (2) they were international students, and/or (3) they had spent more than one year in an English-speaking country. As a result, the number of participants for the questionnaire data analysis was reduced to 277. Among the 277 first-year students, 116 were male and 161 were female. The participants were from the following academic majors: humanities (43.3%, n = 120), social science (21.7%, n = 69), and science (35%, n = 97). The majority of the participants spoke Mandarin Chinese as

their mother tongue. The average age of the participants was 18 years, ranging from 17 to 20. At the time of data collection, the participants had studied English for 8.8 years on average, with the range between 5 and 13 years (SD = 2.16). Participants’ English proficiency levels ranged from beginning to advanced levels. The participants’ English proficiency levels were inferred from their scores of (1) the English subject in the Joint College Entrance Examination, as reported in the questionnaire, (2) the English proficiency tests (e.g., GEPT), if taken and reported in the questionnaire, and (3) a proficiency test developed by Fotos (1991)3 that they received for other research projects. Most

of the participants reported that they had received several years of grammar-based instruction in high school. In the questionnaire, the participants were asked how often they were taught grammar in junior and senior high school. Results show that 31.9% of the students indicated “very often”, 46.5% indicated “often” in junior high and 50.5 % indicated “very often” and 38.8% indicated “often” in senior high.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in the current study consists of three sections. Section 1 asks for the participants’ biographical information, including sex, age, prior EFL learning experience, informal exposure to English, and English test scores. Section 2 comprises 20 closed-ended questions, each of which represents a different grammatical feature. The selection of the target features was primarily based on three criteria: (1) they are covered in the high school teaching

3 The proficiency test, developed by Fotos (1991), is a cloze test, which was

syllabus, (2) they are considered more or less problematic for Chinese EFL learners based on my own EFL teaching experience, and (3) they are morphological and/or syntactic in nature. Using these criteria, I reviewed a number of English textbooks and grammar books used in high school in Taiwan. I also consulted with several high school English teachers. The language features selected for this study are presented in Table 1. A review of SLA literature shows that the selected features can be more or less difficult to learn for L2 learners (for discussion of learning of individual features, see, for example, Ammar & Lightbown, 2005; Izumi & Bigelow, 2000; Izumi & Lakshmanan, 1998; Larsen-Freeman, Kuehn, & Maccius, 2002; Mackey, 1999; Master, 1994; McDonough, 2004, 2007; Revesz & Han, 2006; Shirai, 2004; Zhou, 1992).

Table 1

Target Features for the Questionnaire ‧present perfect ‧simple past ‧negation ‧modal auxiliaries ‧countable/uncountable nouns ‧passives ‧articles ‧unreal conditionals ‧embedded questions ‧third person -s ‧clauses ‧present progressive ‧prepositions ‧adjective comparatives ‧past progressive ‧infinitive ‧wh-questions ‧participial constructions ‧question tags ‧real conditionals

In Section 2 of the questionnaire, parts of speech are used to describe each grammar structure. To help the participants understand the parts of speech, two sample sentences using the target structure were provided, with the target structure underlined (for example,

I have finished the job. I have washed my father’s car.). The

participants were asked to indicate the degree of difficulty using a six-point Likert scale, with 1 standing for “Not at all difficult” and 6 standing for “Extremely difficult.” “Not at all difficult” indicates that the student had learned the structure quickly after a short explanation and some practice. “Extremely difficult” indicates that the student does not expect to ever understand the structure fully, even with extensive explanation and practice. The participants were asked to base their rating on their prior grammar learning experience. Figure 1 illustrates what Section 2 looks like.

Not at all difficult Extremely difficult 1 Present perfect • I have finished • I the job. have washed 1 my father’s car. 2 3 4 5 6

2 Simple past -ed • She looked • I

very happy yesterday. talked

1 to my teacher two days ago.

2 3 4 5 6

Figure 1

Examples for the Items in Section 2

Four features of English grammar (third person -s, passives, articles, and present perfect) were selected for Section 3, which was designed to explore reasons for the ease or difficulty of learning these

features from the Chinese EFL learners’ perspectives. These four features were selected because they have been observed to be problematic for Chinese learners to use based on my own teaching experience and that of my colleagues. I also wanted to select features that are considered difficult for these learners to eventually master even though some are taught earlier in their EFL instruction (e.g., third person -s and articles) than others (e.g., passives and present perfect). These four features have also been observed to be problematic for L2 learners to learn (e.g., Ayoun & Salaberry, 2008; Collins, 2002; Dulay & Burt, 1974; Ellis, 1990; Hinkel, 2002; Izumi & Lakshmanan, 1998; Kim & McDonough, 2008; Master, 1994; Muranoi, 2000). Figure 2 illustrates Section 3.

Section 3. Please indicate whether the selected target grammar structures have been

more or less difficult for you to learn, and then please explain why. 1. I think that “third person -s” has been ____ for me to learn.

___ (1) not at all difficult ___ (2) a little bit difficult ___ (3) difficult ___ (4) very difficult

(Sample sentences for “third person -s” →He lives in Taipei. The woman works at

the hospital.).

The reason for my choice is that

Figure 2

To help the participants better understand the questionnaire, a Chinese-English bilingual version of it was provided. The participants were invited to answer the reflective questions in any language they felt comfortable using.

The internal-consistency reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by computing Cronbach’s alpha. The results showed that, overall, the questionnaire has a high degree of reliability, Cronbach’s alpha .93.

RESULTS

To examine students’ perceptions of the grammatical difficulty of the 20 features represented by the closed-ended items, the items were ranked in ascending order based on the value of their mean scores. I examined and compared the items in the lower ranking with those in the higher ranking to explore what might explain the grammatical difficulty ranking. The quantitative data obtained from Section 3 were calculated for their frequencies. The qualitative data were analyzed to address the question of why Chinese EFL learners perceive some of the target features to be more or less difficult to learn than the others.

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics, item-remainder correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha for each item. The 20 items are ranked by their mean scores (from lowest to highest).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics of the Questionnaire

Items n M SD Mode Skewa

Reliability Corrected item total correlation Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted Negation 277 1.17 .57 1 4.37 .54 .93 Third Person -s 277 1.24 .57 1 3.00 .55 .93 Present Progressive 276 1.29 .65 1 2.95 .65 .93 Simple Past -ed 277 1.32 .71 1 2.92 .64 .93

Wh-questions 277 1.47 .80 1 2.18 .64 .92 Modal Auxiliaries 277 1.50 .88 1 1.99 .59 .93 Adjective Comparatives 276 1.76 .83 1 .98 .65 .92 Articles 276 1.82 1.09 1 1.56 .54 .93 Passives 277 1.84 .96 1 1.07 .73 .92 Past Progressive 277 1.88 1.10 1 1.24 .60 .93 (Un)countable Noun 277 2.00 1.11 1 1.07 .55 .93 Present Perfect 277 2.00 1.08 1 1.14 .58 .93 Question Tags 277 2.04 1.05 2 1.08 .64 .92 Infinitives 276 2.11 1.08 2 .96 .71 .92 Clauses 277 2.35 1.20 2 .78 .66 .93 Embedded Questions 277 2.51 1.14 2 .50 .64 .92 Prepositions 277 2.87 1.40 2 .43 .62 .93 Real Conditionals 277 3.06 1.34 3 .31 .62 .93 Participial Construction 277 3.11 1.40 3 .30 .66 .92 Unreal Conditionals 277 3.32 1.28 3 .13 .61 .93 Note. a Standard error of skewness is .15.

continuum from 1 to 6), while three remaining items have a mean score of around 3. The lowest mean score of the 20 items is 1.17, and the highest is 3.32. A reading of standard deviations indicates that the range of the standard deviations is small (from .57 to 1.14) and that less difficult features (i.e., features with lower mean scores) tend to have a smaller standard deviation than more difficult features (i.e., features with higher mean scores). Positive skewed distributions are observed on students’ responses to all but the item “unreal conditionals.” 4

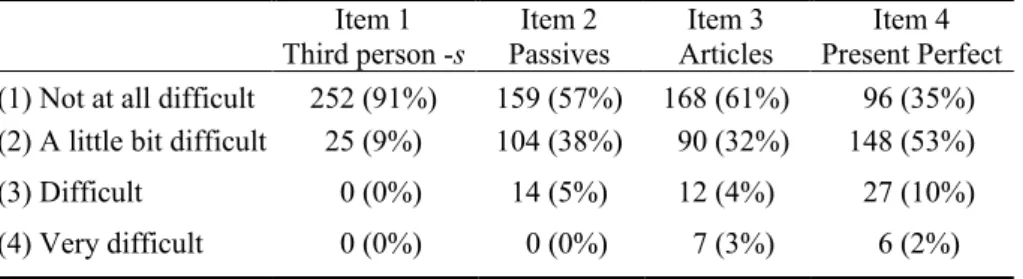

Table 3 shows the frequencies of the students’ responses for each item in Section 3. As Table 3 indicates, few students considered learning of the four selected features to be difficult. However, the frequency results also suggest that these four features were not perceived to be equally easy to learn. The findings match those obtained from Section 2.

This positively skewed response distribution suggests that, on the whole, this sample of Chinese college EFL learners did not perceive any of the 20 target features to be very difficult, although some of the features were perceived to be more difficult than the others.

Table 3

Frequency Counts of Students’ Responses in Section 3 Item 1

Third person -s Passives Item 2 Articles Item 3 Present Perfect Item 4 (1) Not at all difficult 252 (91%) 159 (57%) 168 (61%) 96 (35%) (2) A little bit difficult 25 (9%) 104 (38%) 90 (32%) 148 (53%) (3) Difficult 0 (0%) 14 (5%) 12 (4%) 27 (10%) (4) Very difficult 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 7 (3%) 6 (2%)

The analysis of the qualitative data showed that learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty can be examined with reference to the syntactic, semantic, and/or pragmatic levels. It was found that the students who considered the four target features to be easy to learn were mostly referring to the syntactic level. Many students commented that third person -s or passives is easy to learn because formulation of the feature requires a simple rule of thumb. Here “rule of thumb” refers to overly simplified grammar rules used to help learners to learn the formation of grammar structures. To illustrate, a rule of thumb for the syntactic constituents of English be-passive might be something like, “the passive is composed of an auxiliary be and a past participle.” A rule of thumb for the syntactic constituents of third person -s might be something like, “add -s to the base form of a verb that follows a singular subject.” Likewise, articles and present perfect were perceived to be easy to learn for the same reason. However, the students who considered the target features to be a little bit difficult or difficult to learn were often referring to the semantic or pragmatic level. For example, some students commented that the present perfect is difficult for them to learn because it is too abstract for them to understand. A number of students who considered the passives to be difficult to learn reported that they are not clear when to use the passives. Similar comments were made by some students with regard to learning of the articles.

The qualitative data also showed that students’ impression of their teachers’ grammar instruction exerts some influence on their perceptions of grammatical difficulty. For instance, some students commented that they considered the present perfect to be easy to learn because their teachers taught this feature very well. Similar comments

were made for learning of the passives. Moreover, some students are aware of the influence of L1 on their learning of the grammar features. For example, several students commented that Mandarin Chinese does not have the present perfect, so this tense is conceptually difficult for them. Similar comments were made by some students who reported that they are not always clear on how to use the present perfect. Some students stated that the passives are easy to learn because the passive sentences are easy to understand if they are translated into Mandarin.

Overall, the comments associated with the syntactic level appeared most frequently in the students’ remarks, in which the syntactic constituents of the target features were often presented in overly simplified “formulas,” (for example, “be + P.P. (past participle)” (symbolizing the passive construction)), or basic “rules of thumb.”

DISCUSSION

The first Research Question asks which features of English grammar university-level Chinese EFL learners perceive as easier, and which as more difficult, to learn. The quantitative data of the questionnaire suggest that, on the whole, this sample of Chinese EFL learners did not perceive any of the 20 target features to be very difficult, although some of the features were perceived to be more difficult than the others. The quantitative findings obtained from Section 3 were in line with this finding. This finding might be, in part, due to the fact that the questionnaire explores difficulty primarily at the syntactic level, and English learning at this level tended to be

perceived as relatively easy by this group of learners because of their years of de-contextualized, form-oriented L2 learning experience. In the questionnaire, the target features are presented via the use of parts of speech and illustrative sentences in which they are highlighted (e.g.,

I have finished

Although the learners tended to perceive the learning of the 20 target features to be easy, some of the features were perceived to be easier than others. Because the descriptive statistics of the questionnaire show that the mean score differences for some features are small, only the six features with the lowest mean scores and the six features with the highest mean scores are discussed here. The six features ranked as “least difficult” in the questionnaire are negation,

the job.). This format emphasizes the syntactic aspect

of the target features, which might have predisposed the learners to reflect upon their prior learning of that aspect of the target features. The findings of the qualitative data support this speculation, showing that most of the learners’ comments were about learning of the syntactic level of the target features. The qualitative data also suggest that learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty at the syntactic level might be confined to learning of the basic rules of thumbs that are needed for the formation of syntactic constitution of the target features. In this research context, it is not uncommon to see that English language teaching in high school often focuses on the development of grammatical knowledge about English. The students’ reports in the questionnaire also confirmed that grammar is frequently taught in EFL instruction in senior and junior high school. Thus, given their many years of form-oriented L2 learning experience, the learners tended to consider learning syntactic constituents and their associated rules of thumb to be relatively easy.

third person -s, present progressive, simple past -ed, wh-questions,

and modal auxiliaries, while the six features ranked as “most difficult” are clauses, embedded questions, prepositions, real

conditionals, participial construction, and unreal conditionals. An

examination of the features in these two groups suggests that they can be distinguished from each other by the extent of the metalanguage needed to formulate a basic rule of thumb. In the “least difficult” group, all of the features, except for wh-questions, can be formulated comparatively simply. To illustrate, the basic rule of thumb for the formulation of the present progressive might be something like, “to form a present progressive verb, use be plus V-ing.” However, the formulation of wh-questions needs more extensive use of metalanguage than that needed for the formulation of the other five features in the “least difficult” group. One reason why these learners perceived wh-questions to be easy to learn might be that their perceptions were biased by the sample sentences (i.e., “What is your

name?” and “Where do you live?”) used for this feature as these two

sentences are not only taught early in EFL instruction but also frequently learned as “chunks” (that is, these two sentences were learned/memorized as fixed word strings). Therefore, the learners were familiar with the sample sentences and perhaps the type of wh-questions they presented. Such familiarity might have influenced their judgment.

If we examine those features in the “most difficult” group, all of the features, except prepositions, require considerably more use of metalanguage in the rules of thumb that explain their formulation. For example, the basic rule of thumb for real conditionals is something like, “to form real conditionals, write an if-clause and a result clause.

Use present tense in the if-clause, and use present/future tense or modal auxiliaries plus base form of the verb in the result clause.” Even more metalanguage is required to explain the formulation of “tenses” and “clauses.” Prepositions, on the other hand, do not require as much use of metalanguage because in terms of their syntactic constituents (e.g., preposition + noun phrase) they are comparatively simple. However, learning of this feature depends largely on memorization as there are few useful basic rules of thumb to explain their use. This might distinguish this feature from the other five features. In short, the questionnaire ranking results suggest that, generally speaking, learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty are associated with the amount of metalanguage needed to formulate a basic rule of thumb for the features in question; the less metalanguage needed for their formulation, the less difficult they are to learn as perceived by this group of learners, and vice versa. Some researchers (e.g., Housen et al., 2005; Hulstijn, 1995; Hulstijn & de Graaff, 1994) claim that there is a positive correlation between grammatical difficulty and the inherent complexity of rules. The finding of the current study suggests that from the perspective of L2 learners, the positive correlation between the two holds.

However, the questionnaire ranking findings of the present study are not shared by Scheffler’s (2009) study, which, to my knowledge, is the only study that used a similar approach to explore L2 learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty. Comparing Scheffler’s results with those of the present study, both groups of EFL learners tended to perceive prepositions to be more difficult to learn, and articles and passive voice to be less difficult to learn. However, whereas the Polish EFL learners perceived tenses to be the most

difficult to learn, the Chinese EFL learners considered conditional sentences to be the most difficult to learn. One speculation for the discrepancy is that it might be in part due to the difference in the learners’ L1 (Mandarin Chinese vs. Polish). The influence of L1 on L2 learning has been extensively documented in the literature (e.g., Izquierdo & Collins, 2008; Lightbown & Spada, 2000; Spada & Lightbown, 1999; L. White, 1991). The qualitative data of the current study also suggest that learners’ L1 knowledge plays a role in influencing learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty. Thus, it seems reasonable to suppose that the discrepancy might be in part due to the difference in the learners’ L1. However, how the features of the two languages might have influenced the learners’ perceptions, and thus caused the discrepancy, remains unclear as the two studies did not provide us with sufficient information regarding how learners’ L1 would influence their perceptions of grammatical difficulty for individual grammar features. Besides, the fact that there are no other studies of this kind with which to compare the results of these two, it remains unclear whether the ranking differences are due to L1 influence or other factors (for example, the differences in the two groups’ general L2 proficiency (varied proficiency levels vs. advanced level)). More empirical investigation into learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty is warranted.

The second Research Question asks: Why do Chinese EFL learners perceive some of the selected features to be more or less difficult to learn than the others? Analysis of the qualitative data indicates that learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty can be examined with reference to the syntactic, semantic, and/or pragmatic levels. The finding on the one hand supports Larsen-Freeman’s (2001

and elsewhere) argument that grammatical difficulty should be examined in relation to linguistic form, semantic meaning, and

pragmatic use. On the other hand, it suggests that learners’

perceptions of grammatical difficulty are associated with their knowledge of L2 syntactic constituents, semantics and pragmatics. The reason that the comments associated with grammar learning at the syntactic level appeared most frequently in the students’ discussions of grammatical difficulty might be because their previous form-oriented grammar learning experiences made them more likely to draw on this domain of knowledge than on semantic or pragmatic knowledge in their discussion of grammatical difficulty. Nonetheless, it is also possible that the fact that the questionnaire used emphasized the syntactic aspect of the target features made it less likely for students to consider other domains of language use or knowledge in their discussion.

The finding that learners’ impression of their teachers’ instructional methods contributes to learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty suggests that L2 teachers play an important role in determining whether learners perceive the learning of grammar to be easy or not. In addition, the finding that some students are aware of the influence of L1-L2 differences on their use or their understanding of the meaning of the selected features suggests that grammatical awareness associated with L1 influence may somewhat impact learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty at different aspects (e.g., syntactic, semantic, pragmatic). In other words, the influence of learners’ L1 on their perceptions of grammatical difficulty can be examined with reference to syntactic, semantic, and/or pragmatic levels. However, as the current study included only

four grammar features in its qualitative inquiry, further empirical investigation comprising comprehensive grammar features is needed in order for us to get a better understanding of in what way and to what extent learners’ L1 may influence their perceptions of grammatical difficulty. In sum, the qualitative findings suggest that learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty are influenced by factors related to their L2 knowledge, L2 grammar learning experience, and L1 knowledge.

CONCLUSION

This exploratory study set out to investigate the issue of grammatical difficulty from Chinese EFL learners’ perspectives. The findings of the current study indicate that Chinese EFL learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty are influenced by multiple factors. While learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty included reference to syntactic, semantic, and/or pragmatic levels, overall, this group of Chinese EFL learners perceived learning of the target features at the syntactic level to be relatively easy. Notwithstanding, learners perceived syntactic features that require more extensive use of metalanguage to describe their formulation as more difficult to learn than those that can be described more simply. The findings, however, must be interpreted in light of limitations with regard to the research design and the research instrument used. The current study was conducted in an EFL context where the learners’ L1 is primarily Mandarin and their L2 learning is primarily grammar-oriented. Therefore, the findings may not be applicable to other L2 learner populations. Besides, they cannot be generalized to grammar

features other than those investigated in the study. Moreover, due to the fact that the questionnaire did not distinguish grammatical difficulty in different senses (e.g., form, meaning, use), the questionnaire findings are informative only about learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty at the syntactic level.

The current study is one of the few studies that explored the issue of grammatical difficulty from L2 learners’ perspectives. More studies in a variety of learning contexts (for example, EFL, ESL, immersion programs), with learners of different age groups and L1s, and with different target features are warranted. Future studies could also respond to the limitations of the current study regarding the design of the questionnaire and, thus, is able to explore learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty at other levels (e.g., semantic, pragmatic levels) or in terms of comprehension and production. Also needed is research with different designs (e.g., interview) that explores in more depth as to what may influence learners’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty. Another promising research line is to compare students’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty with their actual grammar use in different tasks.

From a pedagogical perspective, the finding that learners perceive grammatical difficulty on different levels (syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic) suggests that when L2 learners describe features as easy or difficult to learn, it is essential for teachers to be aware of the level of learning difficulty that they are referring to. In addition, it is important for teachers to draw learners’ attention to all aspects of the challenges of learning language forms (e.g., syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects). This may be particularly important in instructional approaches that focus exclusively on one aspect of

language or another (e.g., form and meaning). Furthermore, for the students whose prior language experience is primarily form-oriented, L2 instruction should include opportunities for the communicative use of grammar features that learners have no difficulty verbalizing their rules, and that they perceive as easy to learn or to describe.

REFERENCES

Ammar, A. (2008). Prompts and recasts: Differential effects on second language morphosyntax. Language Teaching Research,

12(2), 183-210.

Ammar, A., & Lightbown, P. M. (2005). Teaching marked linguistic structure-more about the acquisition of relative clauses by Arab learners of English. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.),

Investigation in instructed second language acquisition (pp.

167-198). New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ammar, A., & Spada, N. (2006). One size fits all?: Recasts, prompts, and L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 543-574.

Ayoun, D., & Salaberry, M. (2008). Acquisition of English tense-aspect morphology by advanced French instructed learners.

Language Learning, 58(3), 555-595.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2000). Tense and aspect in second language

acquisition: Form, meaning and use. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Berent, G. (1985). Markedness considerations in the acquisition of conditional sentences. Language Learning, 35(3), 337-372. Celce-Murcia, M., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book:

Collins, L. (2002). The roles of L1 influence and lexical aspect in the acquisition of temporal morphology. Language Learning, 52, 43-94.

Collins, L., Trofimovich, P., White, J., Cardoso, W., & Horst, M. (2009). Some input on the easy/difficult grammar question: An empirical study. Modern Language Journal, 93, 336-353. DeKeyser, R. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty

& M. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language

acquisition (pp. 313-348). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

DeKeyser, R., & Sokalski, K. (1996). The differential role of comprehension and production practice. Language Learning,

46, 613-642.

Doughty, C. (2001). Cognitive underpinnings of focus on form. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 206-257). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C., & Varela, E. (1998). Communicative focus on form. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom

second language acquisition (pp. 114-138). Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (1998). Issues and terminology. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom

second language acquisition (pp. 1-11). Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Dulay, H., & Burt, M. (1974). Natural sequences in child second language acquisition. Language Learning, 24, 37-53.

Ellis, R. (1990). Instructed second language acquisition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Ellis, R. (2007). The differential effects of corrective feedback on two grammatical structures. In A. Mackey (Ed.), Conversational

interaction in second language acquisition (pp. 339-360).

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Basturkmen, H. (2006). Disentangling focus on form. A response to Sheen and O’Neill (2005). Applied

Linguistics, 27(1), 135-141.

Fotos, S. (1991). The cloze test as an integrative measure of EFL proficiency: A substitute for essays on college entrance examinations? Language Learning, 41(3), 313-336.

Gass, S., & Selinker, L. (Eds.). (1992). Language transfer in

language learning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Goldschneider, J. M., & DeKeyser, R. M. (2005). Explaining the “natural order of L2 morpheme acquisition” in English: A meta-analysis of multiple determinants. Language Learning,

55(Suppl. 1), 27-77.

Green, P., & Hecht, K. (1992). Implicit and explicit grammar: An empirical study. Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 168-184.

Hinkel, E. (2002). Why English passive is difficult to teach (and learn). In E. Hinkel & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on

grammar teaching in second language classrooms (pp.

233-259). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Housen, A., Pierrard, M., & Van Daele, S. (2005). Structure complexity and the efficacy of explicit grammar instruction. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.), Investigations in instructed

second language acquisition (pp. 235-269). Brusells, Belguim:

Hulstijn, J. (1995). Not all grammar rules are equal: Giving grammar instruction its proper place in foreign language teaching. In R. Schmidt (Ed.), Attention and awareness in foreign language

learning (pp. 359-386). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.

Hulstijn, J., & de Graaff, R. (1994). Under what conditions does explicit knowledge of a second language facilitate the acquisition of implicit knowledge? A research proposal. AILA

Review, 11, 97-112.

Izquierdo, J., & Collins, L. (2008). The facilitative role of L1 influence in tense-aspect marking: A comparison of Hispanophone and Anglophone learners of French. Modern

Language Journal, 92, 350-368.

Izumi, S., & Bigelow, M. (2000). Does output promote noticing and second language acquisition? TESOL Quarterly, 34, 239-278. Izumi, S., & Lakshmanan, U. (1998). Learnability, negative evidence

and the L2 acquisition of the English passive. Second Language

Research, 14(1), 62-101.

Kellerman, E., & Sharwood-Smith, M. (Eds.). (1986).

Cross-linguistic influence in second language acquisition. London:

Pergamon.

Kim, Y., & McDonough, K. (2008). Learners’ production of passives during syntactic priming activities. Applied Linguistics, 29(1), 149-154.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language

acquisition. London: Pergamon.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2001). Teaching grammar. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 251-266). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2003a). Teaching language: From grammar to

grammaring. Boston: Thomson & Heinle.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2003b). The grammar of choice. In E. Hinkel & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on grammar teaching (pp. 105-120). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Larsen-Freeman, D., Kuehn, T., & Maccius, M. (2002). Helping students make appropriate English verb tense-aspect choices.

TESOL Journal, 11(4), 3-9.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2000). Do they know what they’re doing? L2 learners’ awareness of L1 influence. Language

Awareness, 9(4), 198-216.

Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie & T. Bhatia (Eds.),

Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). San

Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Long, M. (2007). Recasts in SLA: The story so far. In M. Long (Ed.),

Problems in SLA (pp. 75-116). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Lyster, R. (2004). Differential effects of prompts and recasts in form-focused instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition,

26, 399-432.

Lyster, R., & Izquierdo, J. (2009). Prompts versus recasts in dyadic interaction. Language Learning, 59(2), 453-498.

Mackey, A. (1999). Input, interaction and second language development: An empirical study of question formation in ESL.

Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 557-587.

Master, P. (1994). The effect of systematic instruction on learning the English article system. In T. Odlin (Ed.), Perspectives on

pedagogical grammar (pp. 229-252). New York: Cambridge

University Press.

McDonough, K. (2004). Learner-learner interaction during peer and small group activities in a Thai EFL context. System, 32, 207-224.

McDonough, K. (2007). Interactional feedback and the emergence of simple past activity verbs in L2 English. In A. Mackey (Ed.),

Conversational interaction in second language acquisition (pp.

323-338). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Meisel, J., Clahsen, H., & Pienemann, M. (1981). On determining developmental stages in natural second language acquisition.

Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 3, 109-135.

Muranoi, H. (2000). Focus on form through interaction enhancement: Integrating formal instruction into a communicative task in EFL classrooms. Language Learning, 50(4), 617-673.

Odlin, T. (1989). Language transfer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Odlin, T. (2003). Cross-linguistic influence. In C. Doughty & M. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 436-486). New York: Blackwell.

Pienemann, M. (2005). An introduction to processability theory. In M. Pienemann (Ed.), Cross-linguistic aspects of processability

theory (pp. 1-60). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Revesz, A., & Han, Z. (2006). Task content familiarity, task type and efficacy of recasts. Language Awareness, 15(3), 160-179. Scheffler, P. (2009). Rule difficulty and the usefulness of instruction.

Selinker, L., & Lakshamanan, U. (1992). Language transfer and fossilization. In S. Gass & L. Selinker (Eds.), Language transfer

in language learning (2nd ed., pp. 196-215). Philadelphia: John

Benjamins.

Shirai, Y. (2004). A multi-factor account for form-meaning connections in the acquisition of tense-aspect morphology. In B. VanPatten, J. Williams, S. Rott, & M. Overstreet (Eds.),

Form-meaning connections in second language acquisition (pp.

97-122). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. M. (1999). Instruction, L1 influence and developmental readiness in second language acquisition.

Modern Language Journal, 83, 1-22.

Spada, N., Lightbown, P. M., & White, J. (2005). The importance of meaning in explicit form-focused instruction. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.), Current issues in instructed second

language learning (pp. 199-234). Brussels, Belgium: Mouton

De Gruyter.

Stockwell, R. P., Bowen, J. D., & Martin, J. W. (1965). The

grammatical structures of English and Spanish. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language

teaching and learning (pp. 471-481). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

White, J. (1998). Getting the learners’ attention: A typographical input enhancement study. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.),

Focus on form in classroom language acquisition (pp. 85-113).

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

White, L. (1991). Adverb placement in second language acquisition: Some effects of positive and negative evidence in the classroom.

Second Language Research, 7, 133-161.

Williams, J., & Evans, J. (1998). What kind of focus and on which forms? In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in

classroom second language acquisition (pp. 139-155).

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Zhou, Y. (1992). The effect of explicit instruction on the acquisition of English grammatical structures by Chinese learners. In C. James & P. Garrett (Eds.), Language awareness in the

classroom (pp. 254-277). London: Longman.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Li-Ju Shiu is an instructor in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at the National Chi Nan University. Her research interests include (instructed) second language acquisition, learner beliefs about second language learning, and second language assessment. Dr. Shiu has been involved in research projects investigating the effect of form-focused instruction on second language learning. Participating in a research project directed by Professor Nina Spada, the author is currently doing research on the validation of measures of second language knowledge. Her other current research focuses on (1) exploring learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of grammatical difficulty, and (2) investigating the efficacy of corrective feedback in second language writing.