DOI:10.6245/JLIS.2016.421/700

Contextual Design Methods

for Information Interaction in the Workplace

Ben Heuwing

Information Science, University of Hildesheim, Germany E-mail: heuwing@uni-hildeheim.de

Thomas Mandl

Information Science, University of Hildesheim, Germany E-mail: Mandl@uni-hildesheim.de

Christa Womser-Hacker

Information Science, University of Hildesheim, Germany E-mail: womser@rz.uni.hildesheim.de

Established methods from user-centered design can be applied to the design of systems that support information interaction in the workplace. In order to gather data about current work practices, a number of different methods have been proposed in studies on information needs and information seeking behavior, including work-shadowing (Görtz, 2011), diary studies (Elsweiler et al., 2010), in-depth interviews (Kuhlthau, 2003) and questionnaires (Lim, 2009). These methods can be adapted and enhanced to apply them to elicit requirements for complex information systems in professional contexts such as information retrieval and large-scale information analysis. Results of fundamental information behavior research have the potential to guide these more focused studies, for example, as indicators of which dimensions of the context of use should be considered. In addition, results of several projects in similar work contexts can be analyzed as case studies to generate generalizable insights into the information behavior of a community of practice.

This contribution presents and compares methods which can be used to elicit information about users in the workplace, and to analyze and to create requirements based on these results, especially from scenario based design (Rosson & Carroll, 2002) and contextual design (Holtzblatt et al., 2004). Examples for the application of these design methods will be taken from two projects. The first project investigates the potential of usability related information as a knowledge resource in organizations. The second project is an ongoing, interdisciplinary research project in the area of

digital history. Both projects demonstrate ways to investigate contexts of information use in organizations to create new information structures and to define requirements for information systems.

Case 1: Interviews with Usability Engineers & Scenario Based Design

Results of usability studies in organizations are a valuable information resource which can be used beyond the scope of current development projects (Rosenbaum, 2008). Usability information is currently mostly collected in the form of long reports which are difficult to access and apply to new contexts when needed. With few exceptions (e.g. Hughes, 2006), organizations who conduct usability studies for their own products do not have much experience in making use of their collected usability information. Proposals from research have been put forward to structure usability problem descriptions for the comparative evaluation of usability methods, e.g., the User Action Framework (Andre et al., 2001). However, these information structures have not been targeted at the needs of usability engineers when managing their usability information and require considerable efforts when applied in practice because of their complexity (Hornbæk & Frøkjær 2008:511).

Because of this, semi-structured interviews with eight internal usability engineers from different companies were conducted in order to gather information about the current application and reuse of the results of their everyday work, conducting and documenting usability studies and communicating the results within their company. In this context, the observation of participants would have been difficult because the work of conducting a user study usually takes several weeks. In addition, there were concerns regarding the privacy of the data that were collected in the user studies. Because of this, at the beginning of an interview the participants selected a case in which they had recently reused usability information. The interviews then followed this case as a scenario. This approach helped to increase external validity and to elicit concrete details of information use. During most interviews, concentrating on the example scenario provided useful and situated results, even though some participants tended to switch among different projects. After the scenario-based part of the interview was completed, participants were asked more specific questions about additional possible use cases for usability information derived from the research literature. The results were partly transcribed and analyzed regarding possible scenarios of the use of internal usability information and the chances and obstacles connected with each. Based on these cases, three problem scenarios (Rosson & Carroll, 2002) for different personas were created to summarize the results. Claims analysis (Rosson & Carroll, 2002) of each activity in these scenario helped to identify potential improvements during search and information analysis in a transparent way. These requirements were summarized as activity scenarios describing possible solutions.

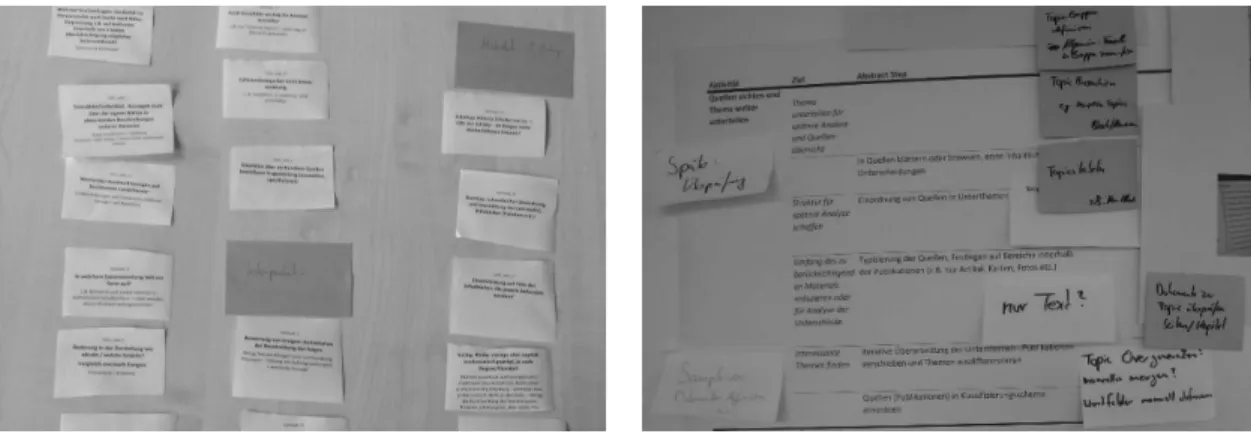

Fig 1: Visualization during the group discussion: Examples of use cases for usability information (left column), metadata needed to search for information (center) and useful information types (right).

In contrast to interaction requirements, the definition of which metadata should be made available does not lend itself readily to analysis and presentation in the form of scenarios because they can only present exemplary paths of navigating through an information structure. Therefore, a conceptual analysis of the interviews (Blandford & Attfield, 2010) was used to identify important concepts. Focus groups in two organizations helped to discuss these concepts (see example in Fig 1) and to prioritize them using the nominal group technique (Gorman & Clayton, 2005).

Based on the combined results from contextual interviews and focus groups, a facetted navigation was created and implemented as an interactive prototype. Rapid prototyping of an interactive, facetted search interface was facilitated by the Simile Exhibit Framework.[1] This prototype served as input for an evaluation study later in the process (Heuwing et al., 2014).

The user centered process used in this project therefore combines ways of knowledge construction with contextual methods for design. However, direct participation of the user group could have improved the definition of requirements. A way of enabling participation based on empirical results in the context of requirements elicitation for text analysis is presented in the following case study.

Case 2: Contextual Inquiry and Participative Design

in the Digital Humanities

In the ongoing project “Children and their world”, historians need a research infrastructure to search for and to analyze texts within a large corpus of digitized textbooks. The textbooks were

used in German schools during the 19th and the early 20th century. The goal of the project is to

implement and offer new technologies, while also considering existing real-world processes and behaviors of historians.

Contextual interviews were conducted to better understand sense-making behavior (Pirolli & Card, 2005) of historians, i.e., how they proceed from retrieval of sources to the interpretation of texts and to the generation of new arguments and conclusions. In general, for a contextual inquiry study it is preferable to observe users doing their usual, routine work tasks (Holtzblatt et al., 2004). However, the process of historical research takes too long to be easily observable. An alternative, which has been proposed in the literature, is the reenactment of an artificial situation in order to understand information behaviors during similar processes (schraefel et al., 2004). However, our research interest was not focused on a single activity but rather on the larger process of retrieval, analysis and publication. During the research process of historians, documents and other artifacts are created. Retrospective, contextual interviews could be conducted based on these artifacts. Five historians recounted strategies and behaviors during a recent or ongoing research project. Being at their workplace provided them with the possibility to fall back on the artifacts created during their projects to enable better recollections. A major advantage of this approach was the possibility to also take probes of the documents, i.e., copies of documents and screenshots of tool use, for later analysis.

Figure 2: Examples of the affinity diagramming activity (left) and the collaborative annotation of activity models (right)

Analysis of the results was conducted collaboratively by our interdisciplinary project team that consisted of information scientists, computational linguists and two historians as representatives of the user group. Instead of putting the historians in a role of passive users whose behavior is being observed, they actively participated in the analysis of the results during two workshops and helped

to define user needs and requirements. As a preparation for the workshops, important concepts from the domain were extracted from the results of the interviews. During the first workshop, the concepts identified were discussed and sorted by the interdisciplinary project team in an affinity diagramming activity (Figure 2). This helped to shape a common terminology between team members and started discussions on the relationship between text analysis, representation of concepts at a lexical level, and the background knowledge needed to contextualize these concepts.

In addition, important activities identified in the interviews were used to create a general activity model of text analysis. In the subsequent workshop, this model was used to discuss specific requirements in the project using a method called “walk the model” (Holtzblatt et al., 2004). Participants discussed the relevance and transferability of established research activities to the corpus-based, partially automated text-analysis.

Based on the collected requirements, an interactive prototype was created providing access to the complete corpus. Implementation of the interface of the prototype was relatively lightweight based on Apache Solr as a retrieval engine and on a templated standard interface provided with the Solr-Distribution.[2] The prototype was also used in smaller, interdisciplinary cooperative experiments, which help to further refine requirements in the project. Evaluation of this prototype helped to validate the usefulness of the text-mining methods. A summative evaluation of the tools is planned and will incorporate measures from interactive information retrieval and strategies from the evaluation of exploratory search interfaces.

Discussion and Conclusions

Contextual information in the workplace, especially the joint discussion of example documents, helps to increase understanding of the basic requirements of information tasks. In both cases discussed in this extended abstract, users were specialists from different disciplines. In both cases, scenario-based and contextual methods provided insights into the actual informational processes of these expert users and counterbalanced their existing, normative preconceptions about how to structure and use their information. At the same time, their direct input on the design of information structures and systems proved to be important for the generation and prioritization of ideas.

It has been demonstrated that methods from the area of user centered design (Holtzblatt et al., 2004; Rosson & Carroll, 2002) can be applied to understand information seeking in the workplace. However, they have to be adapted and enhanced with forms of group discussion and participation to provide results which are actionable for the design of complex information systems and to enable

interdisciplinary communication. Insights from information behavior research can be employed to guide contextual methods from user centered design and to focus on contextual aspects which are important for the design of information systems.

However, the methods described here may lack some of the rigor of the ethnographic methodologies they have been derived from and cannot be a direct substitute in terms of generalizability and transparence. Therefore, the results cannot themselves be directly generalized to create new models of information behavior in a professional field because they do not systematically take into account more possible dimensions of influence on information behavior such as power relations within an organization in the cognitive work analysis (Fidel & Pejtersen, 2004).

Instead, for scientific projects in the information sciences, the strategies described can be conceptualized as action research (Wilson & Streatfield, 1981), or more specifically, as design research (e.g. Feinberg, 2012). For this, rapid prototyping of interfaces which enable access to data structures is essential. Comparative analysis of several case studies can help to generalize results and to provide broader models of information behavior in the workplace for a community of practice.

Notes

[1] http://www.simile-widgets.org/exhibit [2] http://lucene.apache.org/solr;

https://cwiki.apache.org/confluence/display/solr/Velocity+Response+Writer

References

Andre, T. S., Hartson, H. R., Belz, S. M., & McCreary, F. A. (2001). The user action framework: a reliable foundation for usability engineering support tools. International Journal of Human Computer Studies,

54(1), 107-136.

Blandford, A., & Attfield, S. (2010). Interacting with information, Synthesis lectures on human-centered

informatics. San Rafael, CA:Morgan & Claypool

Elsweiler, D., Mandl, S., & Kirkegaard, L. B. (2010). Understanding Casual-leisure Information Needs: A Diary Study in the Context of Television Viewing. Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Information

Interaction in Context, IIiX ’10, USA, 25-34. doi:10.1145/1840784.1840790

Feinberg, M. (2012). Information studies, the humanities, and design research: Interdisciplinary opportunities. Proceedings of the 2012 iConference, iConference ’12, USA, 18-24. doi: 10.1145/2132176.2132179 Fidel, R., & Pejtersen, A. M. (2004). From information behaviour research to the design of information

Gorman, G. E., & Clayton, P. (2005). Group discussion techniques. In G. E. Gorman, P. Clayton, S. J. Shep & A. Clayton (Eds.), Qualitative Research For The Information Professional: A Practical Handbook (pp. 143-159). London, England: Facet.

Görtz, M. (2011). Social software as a source of information in the workplace: Modeling information seeking

behavior of young professionals in management consulting. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/

urn:nbn:de:gbv:hil2-opus-1539

Heuwing, B., Mandl, T. & Womser-Hacker, C. (2014). Evaluating a tool for the exploratory analysis of usability information using a cognitive walkthrough method. Proceedings of the 5th Information

Interaction in Context Symposium, IIiX ’14, USA, 243-246. doi:10.1145/2637002.2637033

Holtzblatt, K., Wendell, J. B., & Wood, S. (2004). Rapid contextual design: A how-to guide to key techniques

for user-centered design. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Hornbæk, K., & Frøkjær, E. (2008). Comparison of techniques for matching of usability problem descriptions.

Interacting with Computers, 20(6), 505-514.

Hughes, M. (2006). A pattern language approach to usability knowledge management. Journal of Usability

Studies, 1(2), 76-90.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (2003). Seeking meaning: A process approach to library and information services Second Edition. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Lim, S. (2009): How and why do college students use Wikipedia? Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 60(11), 2189-2202.

Pirolli, P., & Card, S. (2005). The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology as identified through cognitive task analysis. Proceedings of International Conference on Intelligence

Analysis, 5, USA, 2-4.

Rosenbaum, S. (2008). The future of usability evaluation: Increasing impact on value. In E. L.-C. Law, E. T. Hvannberg & G. Cockton (Eds.), Maturing Usability, Human-Computer Interaction Series (pp. 344-378). London, England: Springer.

Rosson, M. B., & Carroll, J. M. (2002). Usability engineering: Scenario-based development of human-computer

interaction. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann

Hughes, G., Mills, H., Smith, G., & Frey, J. (2004). Making tea: Iterative design through analogy. Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, USA, 49-58. doi: 10.1145/1013115.1013124

Wilson, T. D., & Streatfield, D. R. (1981). Action research and users’ needs. In I. Friberg (Eds.), The 4th