Quantitative Restrictions and Foreign Investment

in a Monetary Economy

Chi-Chur Chao

Department of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Eden S. H. Yu*

Department of Economics and Finance, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Abstract

This paper examines the welfare effect of foreign investment under quantitative restric-tions for a host country with a cash-in-advance constraint. This constraint results in a diver-gence between the consumer virtual prices and the world prices. If the cash required for pur-chasing exportable goods exceeds that of the importable, additional foreign investment can widen the price divergence and, thus, reduce welfare. This result is contrary to the conven-tional view that foreign investment is non-immiserizing under quantitative restrictions. On the other hand, if the cash requirement is larger for buying importable goods, foreign investment can still promote welfare.

Key words: foreign investment; quantitative restrictions; cash in advance JEL classification: F11; F21; E10

1. Introduction

The welfare effect of foreign investment under restricted trade measures has been extensively studied. For example, Brecher and Diaz Alejandro (1977) have shown that capital inflows in the presence of tariffs can reduce the welfare of a small open economy due to the subsequent fall in imports. It is, however, notable that the amount of imports is not affected by foreign investment when quantitative trade re-strictions, e.g., quotas and voluntary export restraints (VERs), are in place. As shown by Dei (1985a, 1985b), additional foreign investment in the presence of quantitative restrictions unambiguously improves welfare for the host economy, as a result of a reduction of rental payments to foreign capital.

Over the past few decades, non-tariff barriers, especially quantitative restric-tions, have been increasingly employed for a variety of reasons as well stated by

Received June 7, 2001, accepted December 13, 2001.

*Correspondence to: Department of Economics and Finance, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee

Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong. Email: efedenyu@cityu.edu.hk. We are indebted to two anonymous refe-rees for many insightful comments and suggestions.

Yarbrough and Yarbrough (2000, Ch. 7). It is not uncommon for countries to en-counter difficulties in removing such trade barriers, which are mostly politically mo-tivated. As a result of the difficulties, foreign capital inflows have been regarded as a second-best device for correcting, albeit partially, the trade barrier-induced distor-tions. The striking result of welfare-enhancing foreign investment by Dei is derived in the context of a pure exchange economy. Such an economy differs vastly from our real world in which money is used as a medium of exchange.

Thus, it is worthwhile to re-examine the welfare effect of foreign investment in a monetary economy characterized by a generalized cash-in-advance (CIA) con-straint [Palivos and Yip (1997a, 1997b)]. We find that in such an economy, addi-tional foreign investment under quantitative trade restrictions can be immiserizing. Our result stands in sharp contrast to that of Dei. The rationale for our result is sim-ple. Capital inflows promote the production of the importable sector, thereby lower-ing its domestic prices and worsenlower-ing the existlower-ing CIA-induced distortion in con-sumption. If the induced distortionary effect dominates the gain from reduced pay-ments to foreign capital, capital inflows result in lower welfare.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a model for a small open, monetary economy with quantitative restrictions. The model is then utilized to ex-amine the welfare implications of foreign investment. The critical level of foreign investment that determines whether welfare is enhancing or reducing is also identi-fied. Section 3 offers concluding remarks.

2. The Model

Consider an economy which produces two goods by using foreign capital in addition to domestic factors. Let good 1 be the exportable and good 2 the importable. An import quota or a VER is in place. Consumers purchase both goods in the amount of D and 1 D . In this monetary economy, consumers need cash in ad-2

vance for making transactions. Following Palivos and Yip (1997a, 1997b), a gener-alized CIA constraint is postulated as follows:

M D p D p1 1+ 2 2 2≤ 1 φ φ

,

(1)where p is the price of good i and i M is the cash balances held by consumers. According to (1), the purchase of good i must be financed by cash in a minimum amount determined by φ , where i 0≤φi≤1. This CIA constraint is a generalization of the formulations in Stockman (1981) and Lucas and Stokey (1987). The con-straint generates a consumption distortion, measured by the relative sizes of φ and 1

2

φ . The special case that φ =1 φ2 simply implies non-existence of consumption dis-tortion. Generally, we should have φ ≠1 φ2 for a variety of reasons and regulations. For example, foreign aid can be tied to the purchases of imports, and the government provides export credits to promote exports. Unequal φ 's are typical of developing i economies and also verified by empirical studies [Palivos and Yip (1997a)].

subject to the CIA constraint so as to minimize their total spending M

D p D

p1 1+ 2 2+ for a given level of utility u(D1,D2)≥u.This yields the follow-ing expenditure function: E[(1+φ1)p1,(1+φ2)p2,u]≡ min{p1D1+p2D2+M:

u D D

u( 1, 2)= and φ1p1D1+φ2p2D2 =M

}

. By virtue of the linear homogeneity in prices, we can rewrite the expenditure function as:E[(1+φ1)p1,(1+φ2)p2,u]=) , , 1 ( ) 1

( +φ1 e pv u , where pv≡ p(1+φ2)/(1+φ1) represents the CIA-distorted do-mestic price ratio, or simply the virtual price of good 2 relative to good 1. Notice that p is relevant for consumers only and v p equals the marginal rate of substitu-v tion between goods 2 and 1 in equilibrium. When φ =1 φ2, then pv = , where p

1 2/ p

p

p = and p1=1. By Shephard’s lemma, E1=(1+φ1)e1 =D1and E2 =

2 2 1)

1

( +φ e =D , where E and i e denote the partial derivatives with respect to the i th

i arguments in E(⋅) and e(⋅).

The production side of the model is represented by the revenue function: = ) , , 1 ( p K

R max{X1+pX2:(X1,X2)∈T(K)}, where T(⋅) represents the produc-tion technology and K is the total capital employment including domestic endow-ment K and foreign capital K−K. Here R2(=∂R/∂p) is the domestic production of good 2, and RK(=∂R/∂K) is the domestic rate of return on capital. For simplicity, other production factors in fixed supplies are suppressed in the revenue function.

The equilibrium conditions for the economy can be described by the national budget constraint and the goods-market clearing condition. The national budget con-straint is: ) )( , , 1 ( ) )( 1 ( ) , , 1 ( ) , , 1 ( ) 1 ( +φ1 e pv u =R p K +M + −ω p−p* Q−RK p K K−K , (2) where M is the stock of money supply, Q is the imports subject to quantitative re-strictions, and p* is the world price of the importable. Equation (2) states that the

total spending on goods and the holding of money equals net income, which consists of production revenue and money endowment plus rent retention from imports mi-nus rental payments to foreign capital. As pointed out by Anderson and Neary (1992) and Lahiri and Raimondos (1995), ω is the fraction of quota rents captured by for-eigners, where ω=0 in the case of import quotas and ω=1 for VER.

We turn to the goods market. In equilibrium, consumer demand for good 2 is met by its domestic production and foreign supply:

Q K p R u p e v = + + ) (1, , ) (1, , ) 1 ( φ1 2 2 , (3)

where the import level, Q, is pre-determined under quantitative restrictions.

The equilibrium conditions in (2) and (3) have two endogenous variables, u and p , for a given K. The welfare effect of an increase in foreign capital can be obtained by totally differentiating (2):

dp e Qdp dR K K du eu K 2 1 2 1) ( ) ( ) 1 ( +φ =− − −ω − φ −φ , (4)

where 0eu> , denoting the inverse of the marginal utility of income. The welfare effect depends on the change in the rental payments to foreign capital, the quota

rents lost, and the direction and degree of the CIA distortion. When φ > , the 2 φ1 virtual price of good 2, pv= p(1+φ2)/(1+φ1), exceeds the free trade price of good 2, p*, i.e., pv>p>p*. A rise (fall) in p widens (narrows) the price gap, leading to a welfare loss (gain) captured by the last term of (4).

The change in p plays a crucial role in (4) determining the welfare effect of for-eign investment. To delineate the effect, we totally differentiate the goods-market equilibrium condition in (3): dK R dp R e du e2u 2 22 22 2K 1) [(1 ) ] 1 ( +φ + +φ − = , (5)

where 0e2u> , 0e22< , and R22>0. Notice that R2K>(<)0 when good 2 is

capi-tal (labor) intensive relative to good 1. Substituting (5) into (4) and utilizing dK

R dp R

dRK = K2 + KK , we obtain the effect of an increase in foreign capital on the

domestic price of good 2:

∆ − + + =(1 1)eu[R2K (e2u eu)(K K)RKK] dK dp φ , (6)

where 0RKK ≤ and, as shown in the Appendix, ∆<0 is necessary for stability. There are two forces in determining the changes in p: an inflow of foreign capital expands the production of good 2 and hence lowers its price when good 2 is capital intensive relative to good 1 (R2K >0). On the other hand, the higher income via the reduced payments to foreign capital (i.e., RKK ≤0) pushes p up. In general, the price effect of foreign investment is indeterminate.

Our main task is to assess the welfare effect of foreign investment. Substituting (6) into (4) and using the reciprocity condition, R2K =RK2, we obtain:

∆ + − + − + − − = {( ) 2 ( ) [(1 2) 22 22] 2 } 2K K K RKK e R QR K R K K dK du φ ω ∆ − +(φ1 φ2)e2R2K

.

(7) The first bracketed term on the right-hand-side of (7) captures the welfare effect of foreign investment in the absence of the CIA constraint. As shown by Dei (1985b, eq. 12), this effect is positive under quantitative restrictions attributable mainly to the fall in rental payments to foreign capital. The second term of (7) represents the welfare effect of the CIA constraint, which is positive (negative) depending on whether φ1<(>)φ2.Consider first the case that φ >2 φ1 , in which the virtual price, ) 1 /( ) 1 ( +φ2 +φ1 = p

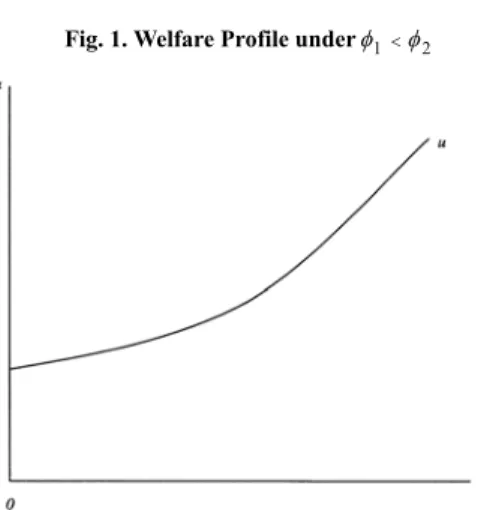

pv , exceeds the world price, p*. If foreign investment lowers p via the direct supply response, the price gap, pv−p*, shrinks. This effect rein-forces the welfare gain of foreign investment. Hence, welfare is an increasing func-tion of K, as depicted in Figure 1. This suggests that for φ > , the optimal level of 2 φ1 foreign capital is free trade in capital, i.e., foreign capital flows in until the domestic rate of capital return equals the world rate.

Fig. 1. Welfare Profile underφ1<φ2

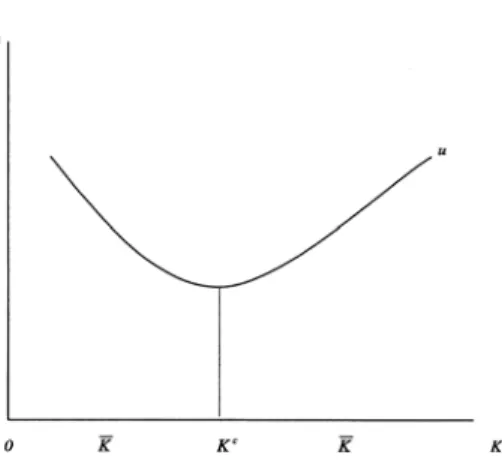

Secondly, when φ > , the virtual price is below the world price [Palivos and 2 φ1 Yip (1997b)]. The fall in p widens the price gap, generating a consumption loss, as indicated in the second term of (7). This loss can mitigate, offset, or even dominate the gain arising from the reduction in rental payments to foreign capital as indicated in the first term of (7). Hence, whether additional foreign investment is wel-fare-improving or reducing depends on the level of K relative to a critical level of capital, Kc, which is solved by setting du/dK=0 in (7):

]} ) 1 [( { ] ) [( 1 2 2 22 2 22 22 2 e Q R R e R R K Kc− = K φ −φ −ω K + KK +φ − . (8)

In fact, this Kc gives a minimum of welfare, which can be proved by checking the

curvature of the welfare function. Following the technique used by Neary (1993), we substitute (8) into (7) to yield:

∆ − − + + − = {R22K RKK[(1 2)e22 R22]}(K Kc) dK du φ . (9)

Hence, under φ > , we have 1 φ2 du/dK<(>)0 if K<(>)Kc, implying that u is a convex function of K. Figure 2 provides a graphical illustration: when K increases, welfare declines initially, reaches a minimum at the critical point Kc, and then starts to rise. Note that the larger the gap between φ and 1 φ in (8), the higher the 2 Kc.

Furthermore, Kc can be larger or smaller than K, as depicted in Figure 2, depend-ing on whether φ − is bigger or smaller than 1 φ2 ωQ/ e2 in (8). Consequently, for

c

K

K<(>) , additional foreign investment lowers (increases) welfare. This suggests that zero inflow of foreign capital is optimal if K<K<Kc, whereas free trade in capital is optimal if K<Kc<K. On the other hand, when Kc<K, the optimal policy is also free trade in capital.

Fig. 2. Welfare Profile underφ1>φ2

Note that under φ > , immiserizing foreign investment occurs when initial 1 φ2

foreign capital is not so large in the host economy (specifically, K<K<Kc). This welfare implication appears to have a bearing on some developing countries, which export non-durable and import durable goods together with the fact that the cash required for the purchase of the non-durable exceeds that of the durable (i.e.,

2

1 φ

φ > ). It follows that these countries may no longer rely on using foreign capital as a second-best device to correct the distortion caused by quantitative trade restric-tions.

3. Concluding Remarks

This paper has considered a small open economy with quantitative restrictions on imports and a cash-in-advance constraint in consumption. These constraints re-sult in a divergence between the consumer virtual price and the world price of im-portable goods. Additional inflows of foreign capital may widen the price gap, thereby reducing national welfare, when the cash required for the transaction of ex-portable goods exceeds that of the imex-portable. This result is contrary to the conven-tional view that foreign capital is welfare-improving under quotas and VERs. Nev-ertheless, when the cash needed for buying importable goods exceeds that of the exportable, additional foreign investment enhances welfare. In this case, attracting foreign capital may still be used as a second-best device to correct trade distortions.

It is worthwhile to mention that the price effect, which narrows the CIA distor-tion, plays a crucial role in our welfare analysis. However, this price mechanism disappears in the case of tariffs, because domestic prices of importable goods in the host economy are fixed by the world prices and tariff rates. Thus, the traditional re-sult of Brecher and Diaz Alejandro (1977) on the welfare effect of foreign invest-ment remains.

Appendix

Following Dei (1985b), the adjustment of the domestic price of the importable is: p&= αZ2(p), where the dot denotes a time derivative, α is a positive constant, and )Z2=(1+φ1 e2−R2−Q is the excess demand for good 2. A necessary and

sufficient condition for stability is dZ2/dp<0. Using (4) and (5), we can obtain where / ) 1 ( /dZ2= + 1 eu ∆ dp φ ∆=(1+φ1){eu[(1+φ2)e22−R22]− e2u[(φ −2 φ1)e2+ ]} )

(K−K R2K +ωQ . Hence, stability requires ∆<0.

References

Anderson, J. E. and J. P. Neary, (1992), “Trade Reform with Quotas, Partial Rent Retention, and Tariffs,” Econometrica, 60, 57-76.

Brecher, R. A. and C. F. Diaz Alejandro, (1977), “Tariffs, Foreign Capital and Immiserizing Growth,” Journal of International Economics, 7, 317-322. Dei, F., (1985a), “Welfare Gains from Capital Inflows under Import Quotas,”

Eco-nomics Letters, 18, 237-240.

Dei, F., (1985b), “Voluntary Export Restraints and Foreign Investment,” Journal of International Economics, 19, 305-312.

Lahiri, S. and P. Raimondos, (1995), “Welfare Effects of Aid under Quantitative Trade Restrictions,” Journal of International Economics, 39, 297-316. Lucas, R. E. Jr. and N. Stokey, (1987), “Money and Interest in a Cash-in-Advance

Economy,” Econometrica, 491-513.

Neary, J. P., (1993), “Welfare Effects of Tariffs and Investment Taxes,” in Theory, Policy and Dynamics in International Trade, W.J. Ethier, ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palivos, T. and C. K. Yip, (1997a), “The Effects of Import Quotas on National Wel-fare: Does Money Matter?” Southern Economic Journal, 63, 751-760.

Palivos, T. and C. K. Yip, (1997b), “The Gains from Trade for a Monetary Economy Once Again,” Canadian Journal of Economics, 30, 208-223.

Stockman, A. C., (1981), “Anticipated Inflation and the Capital Stock in a Cash-in-Advance Economy,” Journal of Monetary Economy, 387-393. Yarbrough, B. V. and R. M. Yarbrough, (2000), The World Economy, Harcourt