1

TRADE ON THE HAN RIVER AND ITS

IMPACT ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT C. 1800-1911

Ts’ui-jung Liu*

This monograph was originally a Ph.D. dissertation completed at Harvard University in May 1974. Later, it was published by the Institute of Economics, Academia Sinica, in the Institute’s Monograph Series, Number 16 (March 1980), 293 pages. (In the following text, notes of each chapter are rearranged under each page and Chinese characters are inserted in the text.)

To the memory of late Professor Li Tsung-tung 李宗侗 (1895-1974) who first guided me on the way of historical research.

__________

*The author was an Associate Research Fellow of the Institute of Economics, Academia Sinica, when this monograph was published.

2

Acknowledgements

This monograph is my doctoral dissertation submitted to the Committee on the degree of Ph.D. in History and East Asian Languages at Harvard University in May 1974. It has not been revised since then mainly because I was occupied with other works during these years. Now that Dr. Tzong-shian Yu, Director of the Institute of Economics, Academia Sinica, has offered me this opportunity of publishing it as a monograph in the Institute’s Monograph Series, I first hesitated about whether it should be published without revision. Considering the time needed for a thorough rewrite, however, I finally decided to let it be printed as it was except for correcting some typing mistakes and adding a Chinese abstract. This is just like leave a footprint on a long way that a student of economic history has committed to stagger along. On this occasion, I wish to express my gratitude to all persons whose kindness and generosity have benefited me a great deal. Especially, my deep gratitude is due to Professor Line-sheng Yang, who supervised my work, provided resourceful advice and warm-hearted encouragement every time when I sought for his instruction. My deep gratitude is also due to Professor John K. Fairbank, Dwight H. Perkins, and Kwang-ching Liu for their criticisms on chapters of my manuscript. To my friends, Miss Beatrice Spade and Mr. Richard Jung, I owe their assistance in improving my English.

My thanks also go to the Harvard-Yenching Institute and Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for generous awards of fellowships which supported me through six years of study at Harvard. To the staff of Harvard-Yenching Library, I wish to express my thanks and remembrance.

I wish to dedicate this monograph to the memory of late Professor Li Tsung-tung since I was not able to express my sorrow in words when I learned of his death in the early spring of 1974.

Ts’ui-jung Liu November 1978

3 CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES, MAPS, AND PLATES MEASUREMENT UNITS

CHAPTER

1 INTRODUCTION: GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2 NAVIGATION ON THE HAN RIVER AND ORGANIZATION OF WATER

TRANSPORT SYSTEM

3 PRODUCTION AND TRADE OF CASH CROPS 4 DEVELOPMENT OF HANDICRAFT INDUSTRIES 5 MARKETING SYSTEM AND ECONOMIC CHANGE 6 CONCLUSION

APPENDIX: NOTES ON THE GRAIN TRADE IN THE HAN RIVER AREA BIBLIOGRAPHY

LIST OF TABLES, MAPS, AND PLATES Tables

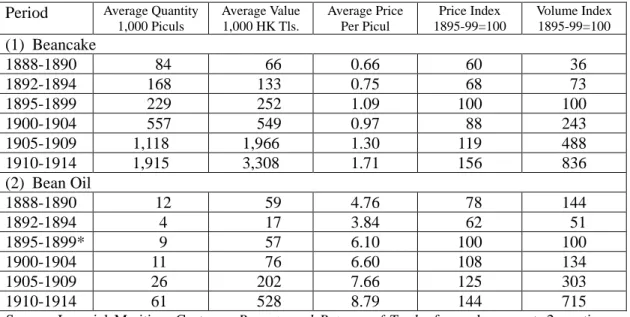

Table 1: Exports of beans from Hankow, 1893-1914

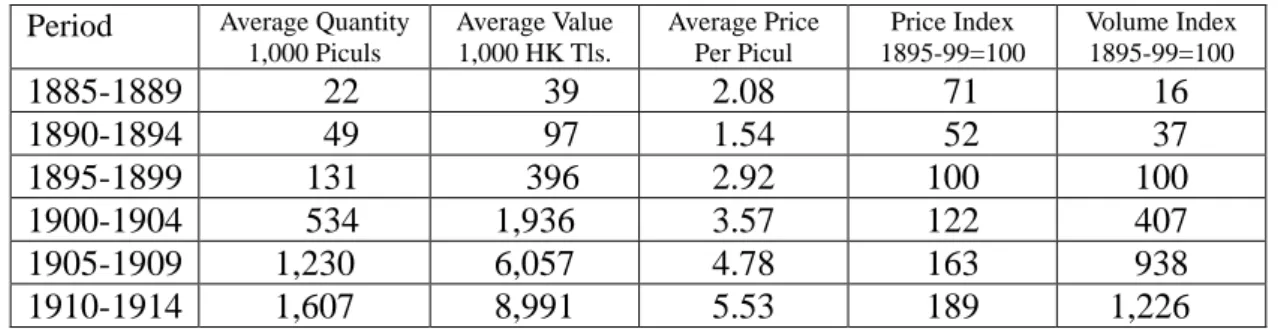

Table 2: Exports of beancake and bean oil from Hankow, 1888-1914 Table 3: Sesame seed exported from Hankow, 1885-1914

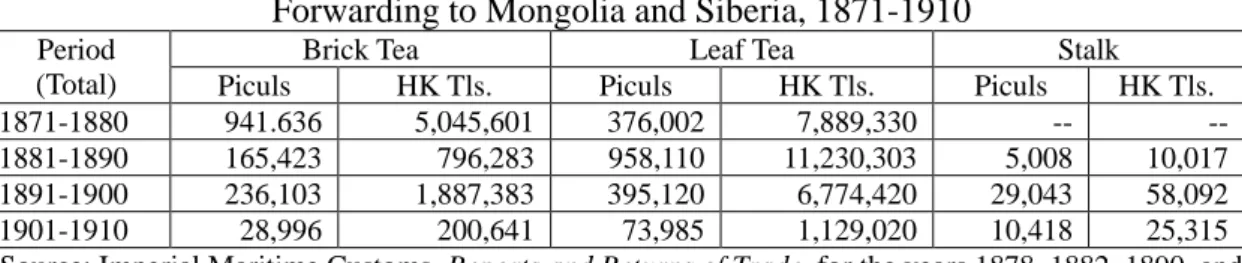

Table 4: Tea transported up the Han River to Fan-ch’eng for forwarding to Mongolia and Siberia, 1871-1910

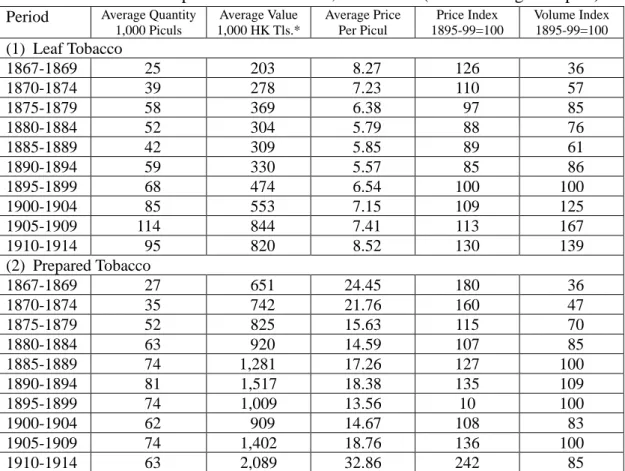

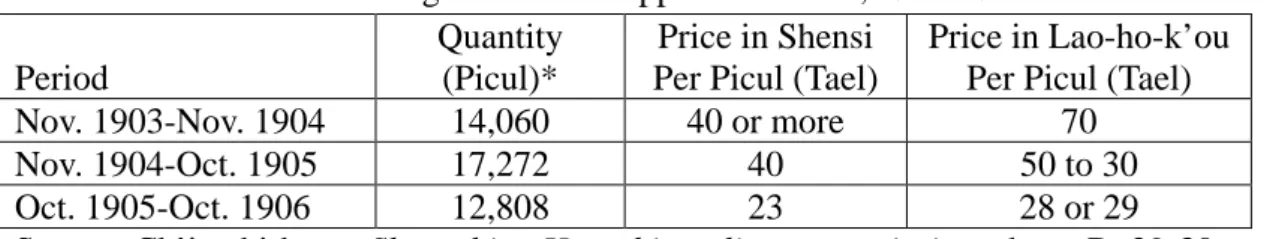

Table 5: The leaf tobacco imported into Shensi, 1904-1906 Table 6: Tobacco exported from Hankow, 1867-1914

Table 7: Turmeric exported from Ch’eng-ku via the Han River, 1904-1906 Table 8: Fungus from the upper Han River, 1904-1906

Table 9: Fungus exported from Hankow, 1904-1906 Table 10: Fungus exported from Hankow, 1867-1914

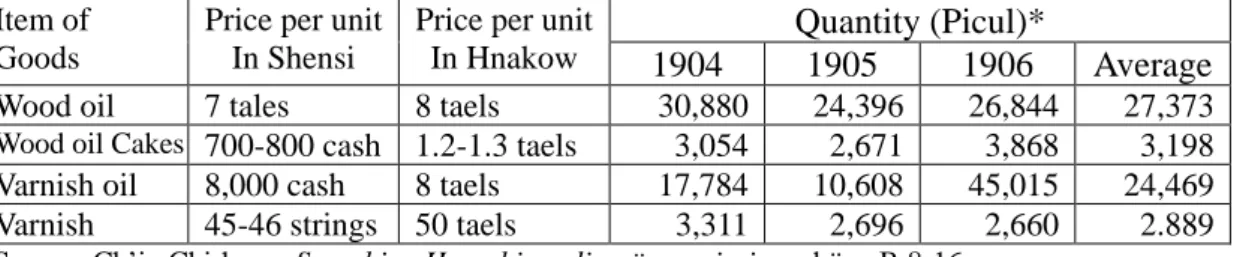

Table 11: Exports of wood oil, wood oil cakes, varnish oil, and varnish from southern Shensi, 1904-1906

Table 12: Exports of wood oil, varnish, and vegetable tallow from Hankow, 1867-1914

Table 13: Varieties and prices of cloth produced around Hankow, c. 1900 Table 14: Raw cotton exported from Hankow, 1877-1914

4

Table 15: Raw cotton imported into southern Shensi through the likin customs, 1904-1906

Table 16: The cotton cloth of Hupeh imported into southern Shensi, 1904-1906 Table 17: Exports of the native cotton cloth from Hankow, 1867-1914

Table 18: Raw silk, tangled silk, and refused cocoon exported from southern Shensi, 1904-1906

Table 19: Ramie exported from Hankow, 1867-1914

Table 20: Paper and paper-mulberry bark exported from southern Shensi, 1904-1906 Table 21: Exports of paper from Hankow, 1867-1914

Table 22: Gypsum exported from Hankow, 1867-1914 Table 23: Gypsum imported into southern Shensi, 1904-1906

Table 24: Number of markets in the rural areas in prefectures along the Han River Table 25: Ratio between the villages and the market towns in Nan-yang hsien, Honan,

1904

Table 26: Average population per market town in Han-chung-fu, c. 1900 Table 27: Average population per market town along the lower Han River area,

c. 1910

Table 28: Commodities imported into and exported from southern Shensi via the Han River, 1904-1906

Table 29: Commodities imported and consumed in Ning-ch’iang chou, c. 1900 Table A-1: Exports of rice from Hankow, 1886-1909

Table A-2: Exports of wheat from Hankow, 1898-1911

Maps

Map 1: Administrative Centers in the Han River Area Map 2: The Han River and its Tributaries

Map 3: The distribution of market towns in Ying-shan hsien

Map 4: The distribution of market towns in Tsao-yang hsien, c. 1910 Map 5: the distribution of market towns in Han-ch’uan hsien, c. 1900 Map 6: Market towns in western part of Ning-ch’iang chou

Plates

Plate 1: Types of boats

5 MEASUREMENT UNITS

Capacity

1 sheng 升 = 1.0355 liters 10 sheng = 1 tou 斗 10 tou = 1 shih 石Weight

1 liang 兩 = 37.3 grams 16 liang = 1 catty 100 catties = 1 picul 120 catties = I shih 石Length

1 ch’ih 尺 = 32 centimeters 10 ch’ih = 1 chang 丈 180 chang = 1 li 里 1 li = 0.5 kilometerArea

1 mou 畝 = 0.16 acre 100 mou = 1 ch’ing 頃These are the Ch’ing standard units. See Wu Ch’eng-lo, Chung-kuo tu-liang-heng

shih (Shanghai, 1957), pp. 122, 234-235.

6

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION:

GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Han 漢 River rises from the Po-chung 嶓冡 Mountain in southwestern Shensi and empties into the Yangtze River, draining an area comprising modern southern Shensi, southwestern Honan, and all of Hupeh lies north of the Yangtze. Conventionally, the area through which the Han River flows is called Han-chiang liu-yü 漢江流域 (the Han River basin).

For this study, the Han River will be taken as the axis about which cities, towns, and villages revolved playing their roles in production and trade. To define the Han River basin area by prefectures during the nineteenth century, it was composed of Han-chung 漢中 and Hsing-an 興安 in Shensi; Yün-yang 鄖陽, Hsiang-yang 襄陽, An-lu 安陸, and Han-yang 漢陽 in Hupeh, situated along the main course of the Han River; Nan-yang 南陽 in Honan, Shang-chou chih-li-chou 商州直隸州 in Shensi, and Te-an 德安 in Hupeh along the major tributaries of the Han River. Moreover, other prefectures in Hupeh, such as Wu-ch’ang 武 昌 , Huang-chou 黃 州 , and Ching-chou 荊州, situated along the Yangtze, and Ching-men chih-li-chou 荊門直隸 州 located between the Han and the Yangtze, were in the periphery of the Han River basin economic and trade area (see Map 1).

To be sure, it is impossible to give equal emphasis to each place in the area. But this study will not present an economic history of any particular locality. Instead, the focus will be on the dynamic function of the Han River in creating economic units along its trade route. The easier a place could communicate with the trading centers along the Han River, the easier it could send out its products and receive those from outside. In other words, the magnitude of importance of a locality depended on the specialties that it produced or trade and the distance from it to the Han River.

Provincial boundaries divided the Han River region into three separate areas, but culturally the Han River basin had much in common. Although administratively, the upper Han River area belonged to Shensi, geographically, this part was different from northern Shensi. The climate and soil along the upper Han River were more similar to those of the Yangtze valley than to the loess plains to the north.1 __________

1

G. B. Cressey compares the upper Han River valley with the basin of Szechwan, see China’s

Geographical Foundations (New York, 1934). Earlier Chinese observers tend to compare the

Han-chung valley with the lower Yangtze valley, see Wang Shih-chen, Shu-tao i-ch’eng-chi (in

Yü-yang san-shih-liu-chung, 1703-1704), A: 23; Wang Chih-yin, Han-nan yu-ts’ao (in Shan-hsi-chih chi-yao, 1827), p. 11.

7

Source: L. Richard, Map of China (Shanghai, 1908).

More significantly, the influx of immigrants into the upper Han River highlands in the late eighteenth century made this part of Shensi all the more closely related to Hupeh.2 One local official, Yeh Shih-cho 葉世倬 (1751-1823), remarked in the early nineteenth century, “Now I come to Ch’in 秦 (i.e., Shensi) as if I were still in Ch’u 楚 (i.e., Hupeh). The mountains of Ch’in are mostly tilled by people from Ch’u.”3 It is also notable that the emigrants from Wu-ch’ang and Huang-chou had their own guild halls (hui-kuang 會館) set up in Shih-ch’üan 石泉.4 This indicates that people from these prefectures were in such a large number that they no longer had to rely on the provincial guild hall. Both the population composition and pattern of production were remolded by these immigrants coming from Hupeh. This historical development brought the upper and lower Han River areas closer together in spite of their being administratively separated into two provinces.

The Han River area was chosen as the focus of this study for the following considerations:

__________

2

Ping-ti Ho, Studies on the Population of China, 1368-1953 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), pp. 149-158.

3 Hsü Hsing-an fu-chih (1812), 7: 39. The official was the prefect of Hsing-an. 4 Shih-ch’üan hsien-chih (1849), 1: 18b-19.

8

whole area together. Before the coming of the railroad, cheap transportation was water-borne, and the Han River provided a natural highway network between the south, the north, and the northwest China. This function of the Han River was important both to the long-distance trade to Mongolia, Siberia, and Central Asia. In response to the stimulus of such trade, agriculture and handicraft industry in the region made definite advances. Therefore, a study of this region must be more than a study of local economic conditions in a vacuum. On the contrary, the study must explore the local developments in light of the complex and intricate interactions between trade and commerce on local, regional, national and international levels.

(2) At the mouth of the Han River stood a great distributing center, Hankow. To be sure, in the seventeenth century, Hankow was already ranked as one of the four largest commercial centers in China and it controlled a vast sphere of domestic trade.5 The opening of the port to foreign trade in 1861, however, brought in goods from modern industrial countries and modified the economic life in the hinterland to a certain extent. Steamship navigation on the Yangtze River speeded up movements of goods;6 this development had the effect of sending in and drawing out a larger amount of commodities to and from the hinterland. The Han River was one of major trade routes connecting with the Yangtze, and the two interacted supplementally and competitively to each other. Obviously, the conditions of trade in Hankow affected those along the Han River and consequently, a study of the Han River basin area must explore the relationships of a dominant commercial center with its major trade and commercial arteries.

From the year 1683 onward, an era of peace and prosperity lasting about one hundred years occurred during the Ch’ing dynasty. During that era, the common people enjoyed frequent exemption from the land tax and they were freed from compulsory labor services.7 The population doubled and more persons reached honorable old age.8 Arable lands were reclaimed and extended, new seeds and new crops were introduced, and productivity was great enough to keep pace with the population growth.9 Moreover, merchants were active and various commodities were __________

5 Liu Hsein-t’ing, Kuang-yang tsa-chi, in Ts’ung-shu chi-ch’eng ch’u-pien (Changsha, 1937), ts’e

2959: 177. The other three centers are Peking, Soochow, and Fo-shan.

6 For an early history of steamship navigation on the Yangtze River, see Kwang-ching Liu, Anglo- American Steamship Rivalry in China, 1862-1874 (Cambridge, Mass., 1962).

7 Ping-ti Ho, Studies on the Population of China, pp. 210-212; cf. Liu Ts’ui-jung, “Ch’ing-ch’u

Shen-chih K’ang-hsi nien-chien chien-mien fu-shui te kuo-ch’eng,” The Bulletin of the Institute of

History and Philology, Academia Sinica, (hereafter CYYY), 32.2 (1967): 760-769. 8 Ping-ti Ho, Studies on the Population of China, pp. 270, 214-215.

9 Ping-ti Ho, Studies on the Population of China, chap. 8; Dwight Perkins, Agricultural Development in China, 1368-1968 (Chicago, 1969), chapters. 2, 3. 4.

9

court in the field of foreign trade.11 Owing to the influx of silver, prices rose but they went up only moderately because there was great demand for money in business transactions.12 The living standard seemed to be improving and the attitude toward spending seemed to be justified under the conditions of prosperity. As pointed out by Professor Yang, a sixteenth-century scholar Lu Chi 陸楫 (1515-1552) advocated a concept comparable to the modern policy of “spending for prosperity.”13 This sixteenth-century advocate of spending has successors in the eighteenth century. For instance, Ku Kung-hsieh 顧公燮 (c. 1780) said, “If there are thousands of people who spend lavishly, there will be other thousands whose livelihood is provided. If one wishes to change the lavishness of thousands of people making them become austere, he will thus deprive the other thousands of their livelihood.”14 While Lu Chi was a native of Shanghai, Ku Kung-hsieh was a native of Soochow. Both of them were familiar with the riches that were brought forth by the economic development in that area from the sixteenth century on. With this background, it is perhaps not surprising that they had such an unconventional attitude that did not conform to the traditional ethic of frugality.

If the living standards of the most developed area in the lower Yangtze area are compared with those in other less developed areas, differences naturally emerge.15 Nevertheless, it seems likely that the living standards in the Han River area also improved in the eighteenth century. For Instance, the T’ien-men hsien-chih 天門縣志 (Gazetteer of T’ien-men county, 1765) remarked,

___________________

10 For Shansi merchants, see Lien-sheng Yang, Money and Credit in China (Cambridge, Mass.,

1971), pp. 81-84; Terada Takanobu, Sansei Shōnin no kenkyū (Kyoto, 1972); this book deals mainly with Shansi and Shensi merchants in Ming times, cf. review by Yang Lien-sheng in Shih-huo yüh-k’an, new series, 3.2 (May, 1973): 88-95. The Han-k’ou Shan-shan-hsi hui-kuan chih (1896) provides information about active Shansi and Shensi merchant groups in Hankow, cf. Niida Noboru, “Shindai no Kankō San-Sen kaikan to San-Sen hō (girudo),” Shankai keizai shigaku, 13.6 (Sept. 1943): 1-23. For Hui-chou merchants, see Fujii Hiroshi, “Shinan shōnin no kenkyū,” Tōyō gakuhō, 36.2 (Sept., 1953): 32-60. For salt merchants, see Ping-ti Ho, “The Salt Merchants of Yang-chou: A Study of Commercial Capitalism in Eighteenth Century China,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 17 (1954): 130-168. For other merchant groups, see Fu I-ling, Ming-Ch’ing shih-tai shang-jen chi shang-yeh tsu-pen (Peking, 1956).

11 Ch’üan Han-sheng, “Mei-chou pai-yin yü shih-pa shih-chi Chung-kuo wu-chia ke-ming te

kuan-hsi,” CYYY, 28 (1957): 517-550.

12 Yeh-chien Wang, “The Secular Trend of Prices during the Ch’ing Period,” Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 5.2 (Dec. 1972): 361.

13 Lien-sheng Yang, “Economic Justification for Spending: An Uncommon Idea in Traditional China,”

in the author’s Studies in Chinese Institutional History (Cambridge, Mass., 1961), pp. 70, 72-74.

14

Ku Kung-hsieh, Hsiao-hsia hsien-chi chai ch’ao (in Han-fen-lou mi-chi, Shanghai, 1917), chüan A: 27.

15 Wang Yeh-chien, “Ch’ing-tai ching-chi ch’u-lun,” Shih-huo yüh-k’an, new series, 2.11 (Feb. 1973):

1-20. In this essay Wang divided China into three major regions based on the different levels of economic development that they achieved in the Ch’ing period.

10

houses and clothing of people were simple and austere; now there are more and more great mansions and people clothe themselves in silk. Regardless of their social classes, men and women all try to rival each other with luxuries and ornaments. Previously, it was the custom to entertain guests with only five dishes; but now even a normal dinner must be prepared by exhausting all the delicacies of the waters and lands.16

Similar comments on the tendency towards a luxurious style of living among the common people are also found in other local gazetteers of districts in the Han River area.17 Although the tone of these comments are not all in favor of conspicuous consumption, these at least reveal that under the traditional economic framework most people were better-off during the eighteenth century than before.

Meanwhile, the traditional economy underwent changes as the tendency of specialization and commercialization developed. Two key documents provide basic information about the area and its trade.18 One is “Shih-huo-k’ao 食貨考” (Treatise on economy) in Hu-pei t’ung-chih kao 湖北通志稿 (Draft gazetteer of Hupeh) by Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng 章 學 誠 (1738-1801). The other is Shan-ching Han-ching liu-yü

mao-i-piao 陝境漢江流域貿易表 (Tables of trade on the Han River in Shensi) by

Ch’iu Chi-heng 仇繼恆 (1855-1935). The first document consists of four sections: (a) major market towns in Hupeh, (b) commodities gathered at the Hankow market, (c) various production activities that inhabitants of each district were engaged in and (d) taxation on commerce and changes in prices (unfortunately, the price data for the year 1795 are no longer available).19 This document presents the economic conditions in Hupeh at the end of the eighteenth century when the Ch’ing empire still enjoyed her last moments of prosperity. The second document consists of two parts: one on commodities imported into southern Shensi and the other on exports from southern Shensi via the Han River. The data in this document were based on the 1904-1906

likin records gathered in Pai-ho 白河, an entrepot between southern Shensi and Hupeh.

In addition, Ch’iu Chi-heng, who was superintendent of the likin bureau, made revealing comments on the current situation of the trade and proposals for economic improvements.20 This document clarifies the economic conditions that existed in ___________

16 T’ien-men hsien-chih (1765 ed., 1922 reprint), 1: 43.

17 Hsiang-yang fu-chih (1760), 6:3; Chu-shan hsien-chih (1807), 1:26b; Chu-hsi hsien-chih (1867),

14:2b-3; Shih-ch’üan hsien-chih (1849), proclamations at the end of last ts’e: 2b-3.

18 Professor Lien-sheng Yang pointed out these two documents to me in a conversation about my

thesis topic.

19 Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng, Chang shih-chai hsien-sheng i-shu (1910), 1: 15b-19b.

20 Ch’iu Chi-heng, Shan-ching Han-chiang liu-yü mao-i-piao, in Kuan-chung ts’ung-shu (1934-

1935), ts’e 47-48.

11

as a starting point and a guideline for combing out useful information from local gazetteers and other source materials.

Chang Hsüeh-cheng described in some detail the phenomenon of specialization and commercialization taking place in Hupeh in the late eighteenth century. Chang had the following remarks on the economic situation in prefectures along the lower Han River.21

In Han-yang-fu 漢陽府, which was in a swampy area, fishing was a flourishing activity, especially in Han-ch’uan 漢川 and Mien-yang 沔陽 districts. Moreover, some inhabitants were engaged in transport services. The Han-ch’uan people steered their boats, known as man-kan 滿幹 (literally, “full of energy”), up to Shensi and Szechwan. The people of Huang-p’i 黃陂 and Hsiao-kan 孝感 pulled wheel-barrows during slack seasons of farming. Those who pulled the wheel-barrows were called

erh-pa-shou 二把手 (the substitutive hands)22 in the sense that they used their own hands for work normally done by mules and horses. In addition, many of the Hsiao-kan people were tailors.

In Te-an-fu 德安府, the livelihood of people in An-lu 安陸 and Ying-shan 應 山 depends on the abundance of jujubes and pears, and in Ying-ch’eng 應城, on profits from gypsum. In Sui-chou 隨州, which was more hilly than normal for farming, farm products were nevertheless sufficient and mountain products were also adequate for subsistence (wen-pao 溫飽, or warm and well-fed). On top of this, cotton and cloth were produced for sale. In Yün-meng 雲夢, which was near Hsiao-kan, the conditions were about the same.

In An-lu-fu 安陸府, most of the people in Chung-hsiang 鍾祥 earned their living as boatmen. T’ien-men 天門, a swampy area, produced an abundance of fish and clams. Profits there were also obtained from growing rushes, reeds, water chestnuts, and water lilies.23 The inhabitants of Ching-shan 京山 were usually distinguished between those living in villages located in hilly regions and those located near lakes. The hill people were industrious in farming; the lake people were skillful in catching the fry of fishes. In Ch’ien-chiang 潛江, people used water to make bark paper, which in turn was used for making umbrellas.

The geographic location of Hsiang-yang-fu 襄陽府 made the prefecture into a __________

21 Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng, 1: 18-19.

22 Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China (Cambridge, 1965), vol. 4, pt. 2, p. 273 note (e) says that erh-pa-shou-che is a modern northern colloquial expression. The mention of this term by Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng suggests that it was already in use during the eighteenth century.

23 Water-lilies were also grown widely in Huang-chou-fu and they were very profitable, see Chang

Hsüeh-ch’eng, 1: 18. Evariste Huc noted the utility of water-lilies when he traveled in Hupeh in the late 1840’s, see L’empier Chinois, English translation (London, 1855), II, p. 310.

12

engaged in commerce. Hsiang-yang produced peaches, gages, rinkins (lin-ch’in 林 檎),24

walnuts, pears, chestnuts, and jujubes. Its cabbages and watermelons were especially good. A great amount of cotton was produced in Tsao-yang 棗陽 along with rice and geese. Nan-chang 南漳 produced abundant firewood, millet, fruits, and vegetables. There were no extremely rich or poor people. Ku-ch’eng 穀城 was known as a gathering center of mountain goods, but it declined gradually because the Hou-ho 後河 river suffered from a build-up of silt. In Lao-ho-k’ou 老河口, the biggest town in Kuang-hua 光化 district, even scholars could not avoid being engaged in trade. The people of I-ch’eng 宜城 were skillful boatmen; they steered the wu-ts’ang-ch’iu-tze 五艙秋子 (five-chambered ell-shaped boats) up to Han-chung and Hsing-an, and down to Hankow. In Chün-chou 均州, tiles and porcelain jars were sometimes produced in local kilns. As the T’ai-ho 太和 Mountain was within the boundary of Chün-chou, people there gathered profits by offering their services to pilgrims who came to visit temples on the mountain.

In Yün-yang-fu 鄖陽府, there were many mountains. The population had remained small until the eighteenth century when immigrants into the area became numerous. The people who cultivated paddy-fields in Yün-yang were mostly immigrants. They were self-sufficient in food and cloth. Special products produced by Yün-his 鄖西 included lichens (shih-erh 石耳), mushrooms, deer’s sinews, and bear’s paws. These all helped provide the people a living. In Chu-hsi 竹谿, where various kinds of grain were grown, there were also turquois mines (lü-sung-shih 綠松 石).25

But the mines were closed down by the government because excavation was difficult. From mountainous Chu-shan 竹山, the furs of badgers and foxes were collected for trade. In Fang-hsien 房縣, where paddy-fields were quite fertile and commodities quite cheap, there were also salt-peter mines. But the mines were officially closed down. In addition, every district in Yün-yang-fu produced fungus, maize, and charcoal.

Such was the situation of commerce and specialization in prefectures along the lower Han River by the end of the eighteenth century. As for the upper Han River area, commercialization in the agrarian sector of the economy also grew during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. According to Yen Ju-i 嚴如熤 (1759-1826),

Each household in the mountains usually keeps a dozen pigs. The pigs are either sold to travelling merchants or driven to market by peasants themselves.

___________

24 The term “rinkins” is adopted from Shih Sheng-han, A Preliminary Survey of the Book Ch’i-Min Yao-shu (Peking, 1962), p. 54.

25 According to Chang Hung-chao, the term lü-sung-shih appeared only in the Ch’ing dynasty, see Shih-ya (Peking, 1927), p. 68.

13

The money made from selling pigs provides the mountain households with salt, cotton cloth, and financial means for the expense of funerals, weddings, and festivals. The pigs gathered at markets are then shipped down the river to Hsiang-yang and Hankow. This is one of the major trades of the mountain households. Just as growing tobacco, turmeric, and medicinal herbs are a supplement to the livelihood of households in the plains, so raising pigs is a supplement to the livelihood of households in the mountains.26

Raising pigs was a by-product of growing maize, for people did not know how to preserve maize over a period of years, so they used it to brew liquor and used the dregs to feed the pigs. In addition to growing various products on farms, opportunities for working in fungus plantations, iron factories, paper mills, timber operations and charcoal plants were available in the mountains.27

This, then, illustrated the multiple activities in the traditional agrarian economy. The study would seem more concrete, if the percentages of population engaging in various production activities could be estimated. But available records do not allow such a calculation. Furthermore, it should be noted that the normal economic life might be disturbed during war times, as when the Han River area was overrun during the White Lotus Rebellion (1795-1804) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864). With this background, this study will discuss the trade on the Han River and its impact on economic changes in the Han river area during the period roughly from 1800 to 1911, when the Ch’ing empire was no longer at her peak. In the following chapter, I shall first survey the conditions of navigation on the Han River and the organization of water transport system that governed the operations of this trade route. Subsequently, I shall discuss the developments in production and trade of cash crops and handicraft industries. Moreover, I shall describe and analyze the structure and operation of the rural marketing system and its effect on economic changes. Finally, the concluding chapter will be devoted to weaving together themes that have been put forward during the course of this study. Data on grain trade will be included in an appendix.

__________

26 Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan (1822), 8: 13b-14. 27 Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan (1822), 9: 2b.

14 Trade on the Han River

CHAPTER 2

NAVIGATION ON THE HAN RIVER AND

ORGANIZATION OF WATER TRANSPORT SYSTEM

The first part of this chapter will present a survey of the conditions of navigation on different stretches of the Han River and the types of boats used on them. It is hoped that such a survey may help us understand the capacity and limitations of this waterway and hence its function in the circulation of goods. The second part of this chapter will discuss the organization of the water transport system that governed the working of this trade route.

Navigation on the Han River

While much of the Han River is navigable, conditions along the waterway differ greatly. From its central source waters in the Po-chung Mountain to Hsin-p’u-wan 新鋪灣 in Mien-hsien, a distance of 23 km., the Han River is not navigable. From Mien-hsien to Han-chung, a distance of 55 km., the river is narrow allowing only rafts and small boats engaged in local transport to ply up and down its waters. From Han-chung to Hankow, the Han River is navigable for a distance of 1,171 km. (see Map 2).1

According to Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng, boats belonging to the people of Han-ch’uan were known as man-kan and they could be employed upriver as far as Shensi. Chang also said that the I-ch’eng boatmen steered their five-chambered

ch’iu-tzu boats up to Hsiang-an and Han-chung and down to Hankow.2 Yen Ju-i noted that from Han-chung downstream, boats carrying up to a capacity load of 100 piculs could navigate the river freely.3 In August 1868, James A. Wylie (1808-1890), a British missionary, traveled on the Han River. He was on board a local boat from Ch’a-chen 茶鎮 to Shih-ch’üan, but at the latter spot he engaged another boat for going to Hankow.4 This evidence seems to suggest that there was no particular point __________

1 The mileages are those given in the Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao included in the Shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao (the Ministry of Economic Affairs, 1939), I, pp. 1-5. In Nishikawa Niichi, Chōkō kōun to ryūiki no fugen (Shanghai, 1925), chap. 2, mileages are given in terms of li. See also

Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan (1822), 5: 4-6. The mileage in li given in this source is longer than those by Nishikawa.

2 Chang Hsüeh-ch’eng, Chang shih-chai hsien-sheng i-shu (1910), 1: 18a; 18b. 3 Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan, 5:4.

4 A. Wylie, “Notes of a Journey from Ching-too to Hankow,” Proceedings of Royal Geographical Society, 14.2 (June 1987): 181.

15

for changing boats along the route between Han-chung and Hankow. However, records of the 1920’s and 1930’s indicated that Lao-ho-k’ou, which was located about midway on the Han River, was used as a point for transfer. From this point up, the Han River flowed over a stony bed and there were over a hundred dangerous rapids which only boatmen of the upper river knew how to avoid. From Lao-ho-k’ou, a boat from downstream going up had much more difficulty than one from upstream going down.5

Map 2: The Han River and its Tributaries

Source: Shui-t’ao ch’a-k’an pao-kao hui-pien (The Ministry of Economic Affairs, 1939), I.

There were various types of boats plying on the Han River (see Plate 1). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Shensi boats which traveled to Hankow directly were known as huo-liu-tzu 火溜子, or “fire clippers”. They were small with a carrying capacity of only 50 to 60 piculs. During the high water level period, the huo-liu-tzu boats plied between Han-chung and Hankow, conveying oak bark, straw rope, and paper downstream and cotton yarn, ironware, and sundries upstream.6

__________

5

Nishikawa Niichi, p. 65. Also see, Chüeh-tzu (pseudonym), “Han-shui san-ch’ien-li yu-chi,” in

Hsin-yu-chi hui-k’an hsü-pien (Shanghai, 1923), 21: 6. 6

Imperial Maritime Customs, Decennial Report, 1882-1891 (Shanghai, 1893), p. 185; Mizuno Kōkichi, Kankō (Tokyo, 1907), p. 207; Tōa dōbunkai, Shina shōbetsu zenshi (Tokyo, 1916), IX, pp. 330-331.

16

Plate 1: Types of Boats

1. and 2. Pien-tzu 3. Ya-shao

4. and 5. Ch’iu-tzu 6. K’ua-tzu

17

Other boats belonging to boatmen of Shensi might take Hsing-an or Lao-ho-k’ou as their terminal point. In the 1930’s, when navigation on the upper Han River had become almost impossible due to disorders, the recollections of old boatmen revealed that at the times when river transport had prospered the number of boats at anchor in Hsing-an usually reached 2,000.7 Investigations done by Li Yi-chih 李儀祉 (1881-1938) and others during the 1930’s revealed that five main types of boats were used on the upper Han River. (1) The p’ing-t’ou lao-kua 平頭老頢, or “flat-headed wild-goose”, had a carrying capacity of 100 piculs and was suitable for carrying both passengers and cargoes. (2) The ch’iu-tzu 秋子, or “ell-shaped” boats, had an average carrying capacity of 100 to 300 piculs although the largest ones could carry up to 1,000 piculs. (3) The o-erh 鵝耳, or “goose-ear,” normally had a carrying capacity of 300 to 400 piculs, although the largest ones could carry 800 piculs. (4) The ya-shao 鴨艄, or “duck-shaped stern,” had an average carrying capacity of 400 piculs with the largest ones of this type being able to carry 600 piculs. (5) The so-tzu 梭子 or “shuttle-shaped” boats, had a carrying capacity of 200 to 800 piculs. Other small boats were known as hua-tzu 划子, or “rowers,” and their carrying capacity also varied.8 Generally, construction of boats plying on the upper Han River was slightly different from those on the lower part of the river. The bottoms of these boats were flat and thick.

Normally it took seven days to go from Han-chung to Hsing-an, and one month to go the same distance in the opposite direction. From Han-chung to Lao-ho-k’ou, it took half a month and for the opposite direction two months.

Very little is known about boating along the upper Han. Few Chinese records were kept on this subject, but foreign travelers attracted by the unusualness of Chinese junk described them in some detail. Boat travel along the upper Han River was described by a famous American geologist, Bailey Willis (1857-1949), who sailed from Shih-ch’üan to Hsing-an in May, 1904. He said:

A houseboat on the Han is a large bateau with the broad, flat bow which experience dictates for boats to stem swift currents, alike among all races of rivermen. Occasionally here the bow is ornamented by a canoe-like upturn, and the stern is distinguished by two great curves wings, which give the model lines of grace that it otherwise lacks. Two-thirds are covered by bamboo matting, enclosing the dwelling places of the captain and his family and the compartment for cargo. The foredeck is open for poling, sculling, and steering with the bow oar; the poop is high and from it the helmsman overlooks the boat and river, but he does not command the course. The responsibility rests on the bow pilot who swings a big oar to turn the boat this __________

7 Li Yi-chih, “Han-chiang hang-yün ch’ing-hsing chi cheng-li i-chien,” in Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao, pp. 90-91. For the decline of navigation on the upper Han River during the early

Republican period, see also Ho Ch’ing-yün, Shan-hsi shih-yeh k’ao-ch’a-chi (Taipei, 1971), p. 47.

18

way or that way where the waters dash and foam over rocks and shallows. …… I had not seen any boats as large as ours, seventy feet over all, afloat on the river, and watched with interest to see how she might be handled. Two heavy sculls, thirty feet long, are pivoted on out-riggers, one on each side to propel the boat. They are worked by three men each, one man standing out on a springboard. Our captain, the bow pilot, mounted a bale of reeds and seized the big bow oar, and off we went with the current.9

Mr. Willis and his companions enjoyed three relaxing days on this part of the Han River, which he compared with the Hudson and the Rhine. In May, the water level was high and the trip was a pleasant one. However, at other times when the water level was low, navigation on the upper Han was often interrupted. Moreover, in order to pass through the rapids it was necessary to hire extra crewmen to walk along the banks pulling junks with ropes made of bamboo. For instance, one hundred men were required to pull a boat through the most dangerous waters along the Golden Gorge (Huang-chin-hsia 黃金峽).10 On some occasions, if the water was shallow, it was necessary to discharge the boat’s cargo before proceeding along the river. In such a situation the cargo had to be divided up and carried by small boats or else moved by laborers along the bank to the next spot where the larger boats could be reloaded.11 The lower part of the Han River, although flowing mostly through a flat plain, was not smooth during the whole course. According to an early nineteenth-century record, between Lao-ho-k’ou and Sha-yang 沙 洋 there were “running sands” (p’ao-sha 跑沙), which appeared very often during summer and autumn and a boat could be buried if it did not escape in time.12 The dangerousness and difficulty of navigation along this region was also noted by Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905) in March, 1870.13 Below Sha-yang, the Han River descend into a plain, and the course was tortuous. Junk navigation on the lower Han River depended mainly on the speed of the water and the direction of the wind. Sails were used when the wind was favorable; otherwise, only sculls were used to propel the junk downstream. Going upstream between Chung-hsiang and Lao-ho-k’ou, if the wind was unfavorable, it was also necessary to pull boats from the river bank as was the case on the upper part of the river.14

The native Hupeh vessels plying the Han River also had various names. In the

__________

9 Bailey Willis, Friendly China, Two Thousand Miles Afoot among the Chinese (Stanford, 1949), pp.

271-271; for the comparison of the Han River and other rivers, see p. 269; p. 275.

10

Ch’iu Chi-heng, Shan-ching Han-chiang liu-yü mao-i-paio, in Kuan-chung ts’ung-shu (1934- 1935), chüan A: 1.

11 Li Yi-chih, p. 91. This practice was known as t’i-t’an (to lift over rapids). 12 Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan, 5: 6a-b.

13 Ferdinand von Richthofen, “Letter on the Province of Hupeh” (Shanghai, 1870), p. 2 14 Shina shōbetsu zenshi, IX, pp. 351-356.

19

late nineteenth century, some of the major kinds of vessels included:15

(1) Ya-shao 鴨艄

This type of boat was built in Han-yang, Sha-shih 沙市 (or Shasi), and Hsiang-yang. They were known as the Huang-p’i 黃陂 ya-shao, Lo-shan 螺山

ya-shao, and other names according to the locales to which they belonged. Their

carrying capacity was usually from 70 to 100 piculs. The largest ones could carry 500 or 600 piculs and these were mostly owned by natives of Huang-p’i. The ya-shao boats were employed upstream to the upper part of the Han River but not as frequently as the ch’iu-tzu boats. They carried rice, sundries, paper, salt, and medicine upstream and yellow soybean, sesame seed, various cereals, fungus, and straw ropes downstream.

(2) Pien-tzu 艑子

This kind of skiff belonged to the Chung-pang 鍾幫 (a group of Chung-hsiang and T’ien-men natives) and the Fu-ho-pang 府河幫 (a group of Te-an-fu natives). There were Huang-p’i pien-tzu and Hsiang-yang pien-tzu. The Hsiang-yang pien-tzu could carry 100 to 250 piculs. They usually plied between Hankow and Lao-ho-k’ou, sometimes carrying passengers as far as Hunan and Kiangsi. Goods shipped upstream were rice, cotton yarn, cotton cloth, paper, salt, and sugar. Those shipped downstream were yellow soybean, sesame seed, tobacco, fungus, and medicine. The Huang-p’i

pien-tzu plied on the Han River as well as on the Pien-ho 便河, a canal connecting

Hankow and Shasi. On the Han River, their cargoes were tobacco, raw varnish, and fungus.

(3) Ch’iu-tzu 秋子

This type of boat appeared on the upper part of the river most frequently. Among them were Yen-ho 晏河 ch’iu-tzu, Yün-yang ch’iu-tzu, Kun-ho 滾河 ch’iu-tzu, Ku-ch’eng ch’iu-tzu, Chün-chou ch’iu-tzu, and wai-p’i-ku 歪屁股, or “wry stern”, Each was named after the locale to which it belonged or after a particular feature of its construction. The carrying capacity of the largest ch’iu-tzu boats was 1,000 piculs, and of the smallest ones 70 to 80 piculs. However, 300 piculs was the normal capacity. The Yen-ho, Ku-ch’eng and wai-p’i-ku ch’iu-tzu shipped various grains, the Yün-yang

ch’iu-tzu crried medicine and mountain goods, while the Chün-chou and Kun-ho ch’iu-tzu conveyed grains and mountain goods. The boats ch’iu-tzu belonged to

Lao-ho-k’ou, Yün-yang and Ku-ch’eng, and plied between Hankow and Yün-yang. A __________

15 The description of these boats is mainly based on the Shina shōbetsu zenshi, IX, pp. 326-330. In

Imperial Maritime Customs, Decennial Report, 1882-1891, pp. 184-185, there is also a brief account on boats visiting the Han River. Types mentioned in these two sources are almost the same. For a discussion on the wai-p’i-ku boat which plied on the upper Yangtze River, see Joseph Needham,

Science and Civilization in China (Cambridge, 1971), IV, pt. 3, pp. 430-431. The structure of this type

20

small passenger boat carried 3 to 4 passengers with a crew of four or five while a large one carried 7 to 8 passengers with seven to eight crew members.

(4) P’ai-chiang 排槳 or P’ai-tzu 排子

This type of boat belonged to Lao-ho-k’ou. The carrying capacity ranged from 30 to 40 piculs to 200 piculs. Between Hankow and Lao-ho-k’ou, they carried foreign cotton yarn, cotton pieces, sundries, and medicine upstream and various grains, oils, fungus, and varnish downstream.

(5) Man-kan 滿幹

These boats were built in Han-yang. They were used to carry both passengers and cargoes and plied between Hankow and Fan-ch’eng.

Usually it took 14 to 15 days to go downstream from Lao-ho-k’ou to Hankow; 24 to 25 days to go in the opposite direction.16 It was quite certain that there had more traffic on this part of the Han River than on the upper part. If the amount of traffic on this section were known, it would be possible to project an estimate about the total trade on the Han River. However, available information does not give us a full picture. In March 1870, von Richthofen traveled on the Han River up to Fan-ch’eng. He counted up to five hundred boats lying at anchor at Sha-yang which he considered the most important trade center between Hankow and Fan-ch’eng.17 In April 1894, a very strong freshet occurred in the Han River, and it was estimated that four hundred vessels were lost.18 A much more detailed account was made by a group of Japanese students during the summer of 1915. They traveled from Lao-ho-k’ou to Hankow and recorded the number of boats they saw within fifteen to thirty minutes after leaving each place except the last part of the journey from Hsien-t’ao-chen 仙桃鎮 to Hankow. The total number of boats going up and down the river when they counted was 443 and the number of those lying at anchor at various places reached 598. But these figures did not include boats plying between Hsien-t’ao-chen and Hankow. It is said that there remained a great number of junks plying along this stretch of the river, although this part had been opened to steamship navigation since 1898.19 This evidence seems to indicate that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at least 500 junks plied up and down the lower Han River every day.

Besides the Han River itself, a score of its tributaries were also navigable.20 Among them, the T’ang-pai-ho 唐白河 and the Tan-chiang 丹江 stood out as inter-provincial waterways. The T’ang-pai-ho indicates two rivers, T’ang-ho 唐河 and __________

16 Mizuno Kōkichi, p. 204. Also see Gaimusho Tsūshokyoku, Shinkoku jijō (Tokyo, 1907), I, p. 984. 17

Ferdinenty von Richthofen, “Letter on the province of Hupeh,” p. 2.

18

Imperial Maritime Customs, Reports and Returns of Trade, 1894 (Shanghai, 1895), pt. 2, p. 109.

19 Shina shōbetsu zenshi, IX, pp. 351-356.

21

Pai-ho 白河, which joined before emptying into the Han River near Fan-ch’eng. Both rivers were navigable by small boats all year round. Although the Pai-ho was larger in size the T’ang-ho was more important in terms of commerce because it led up to She-ch’i-shen 賖旗鎮, which served as an entrepot for the transport of merchandise between the northern and the southwestern provinces before the coming of the railway.21 From She-ch’i-shen to Chou-chia-k’ou 周家口 it was only 380 li by land and water, and Chou-chia-k’ou was situated on the route north to K’ai-feng 開封 and Peking. Although Chou-chia-k’ou was not directly connected by water to the Han River, before the Peking-Hankow railway was built through Honan, there was a good and much used road often crowded by thousands of carts making their way between Chou-chia-k’ou and Hankow.22

The Pai-ho, on the other hand, led up to Nan-yang 南陽. From there overland roads reached Ho-nan-fu 河南府 (where Lo-yang was located) and further north to Shansi and Mongolia. This route was well traveled by Shansi merchants and von Richthofen encountered many of them who were able to speak Russian to him.23 The activities of the Shansi merchants will be mentioned later when we deal with the tea trade, but we may note here that their ability to speak Russian was due to their long experience in trading with Russians at Kiakhta since the early eighteenth century.24 Honan boats were also of different types. Two of them plied as far as Hankow; otherwise Fan-ch’eng was used as a terminal. The two types of boats plying to Hankow were: (1) The K’ua-tzu 舿子 which belonged to the Ho-nan pang, the Pai-ho

pang, and the Ts’ang-t’ai 蒼台 pang. These boats carried goat skins, tobacco leaves,

cow hides, medicine, straw ropes, and oak barks. The carrying capacity of boats of the Ho-nan pang ranged from 80 to 250 piculs, but 100 piculs was the most common load. Those of the Pai-ho pang carried from 70 to 300 piculs while those of Ts’ang-t’ai

pang carried 70 to 100 piculs. (2) The p’ai-tzu boats belonged to Honan but

sometimes were registered in Fan-ch’eng. Their carrying capacity ranged from 50 or 60 piculs to 200 piculs. They plied between Hankow, Fan-ch’eng, and Lao-ho-k’ou __________

21

For a brief account on navigating conditions on the T’ang-ho and Pai-ho, see the Hsiang-yang

hsien-chih (1873), 1: 25-26. For the position of She-ch’i-chen, see Ferdinand von Richthofen, “Report

on the Provinces of Honan and Shansi” (Shanghai, 1875), p. 3; T. W. Kingsmill et al., “Inland Communication in China,” Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, new series, 28 (1893-1984): 20. For the decline of She-ch’i-chen, see Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao, pp. 59-60.

22

T. W. Kingsmill et al., “Inland Communication in China,” pp. 19-20.

23

Ferdinand von Richthofen, “Letter on the Provinces of Chili, Shansi, Shensi, Sz’chwan” (Shanghai, 1872), p. 12.

24

A recent study on the Russo-Chinese trade in the eighteenth century is by Clifford M. Foust,

Muscovite and Mandarin, Russia’s Trade with China and its Setting, 1727-1805 (Chapel Hill, 1969).

This book is mainly based on Russian sources. About the problem of language, Foust says, “… by and large the Russians never mastered Chinese, and it was said that the Chinese use of Russian was grating to the Slavic ear.” p. 214.

22

and the southwestern part of Honan province. The upstream cargoes were sundries, cotton yarn, cotton cloth, and medicine. The downstream cargoes were beans, tobacco, hides, oils, and medicine.25

The Tan-chiang originates in the Ts’in-ling 秦 嶺 mountains and flows southeastward to join the Han river at Hsiao-chiang-k’ou 小江口 in Kuang-hua hsien 光化縣, Hupeh. This river was navigable as far as Lung-chü-chai 龍駒寨 during all seasons and up to Shang-chou 商州 during the summer and autumn when water levels were high enough. In addition to these two places, Ching-tzu-kuan 荊紫 關, situated further down the river, was also a shipping mart. From these three places overland roads led to Sian. According to von Richthofen, it took five days to reach Lung-chü-chai from Sian and two more days to go by land to Ching-tzu-kuan if the river was not in good condition for navigation. Then, it took about four days to follow the Tan-chinag to Lao-ho-k’ou. Based on this information, the trip from Sian to Hankow could be made in about 20 days, but it took 40 to 60 days to make a trip in the opposite direction.26

The navigating conditions on the Tan-chiang were recorded by Liu Hsien-t’ing 劉獻廷 (1648-1695) in the late seventeenth century. Since he elsewhere referred to the Ch’ing government’s abortive plan of cutting a canal from Hsiang-yang to T’ung-kuan 潼關 for transporting rain in 1693, his record must be related to this plan.27 According to Liu Hsien-t’ing, the Tan-chiang navigation was as follows:28

Distance (li) Boats Used (ch’ih) Carrying Capacity (shih) Hsiang-yang to Hsiao-chiang-k’ou, 280 Length Width 100 or 150* Hsiao-chiang-k’ou to Ching-tzu-kuan, 265 30 6 15 or 20 Ching-tzu-kuan to Hsü-chia-tien, 115 20 3 10 or 15 Hsü-chia-tien to Lung-chü-chai, 220 7 or 10 *In the high water level period.

In addition to the necessity of changing boats on the way, there were 363 small and large rapids along the river according to the same source. Under these circumstances, navigation on the Tan-chiang was not easy. However, following the precedent of 1693 __________

25 Shina shōbetsu zenshi, IX, p. 330. In the Kankō, pp. 207-208 and the Decennial Report, 1882-1891, p. 185, only the P’ai-tzu of Honan is mentioned. In Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao,

p. 62, eight types of boats plying on the T’ang-pai-ho are mentioned; among them there are neither

P’ai-tzu nor K’ua-tzu, but there are Pien-tzu, Ch’iu-tzu, and Ya-shao. But these did not belong to

natives of Honan; they were from the lower Han River or even Hunan.

26

Ferdinand von riththofen, “Letter on the Provinces of Chili, Shansi, Shensi, Sz’chuan,” p. 35.

27

Liu Hsien-t’ing, Kuang-yang tsa-chi (Ts’ung-shu chi-ch’eng ch’u-pien, tse 2958-2960), p. 112. For other attempts to cut canals connecting the Han River and the Yellow River area during other dynasties, see Huang Sheng-chang, “Li-shih-shang Huang-Wei yü Chiang-Han chien shui-lu lien-hsi ti kou-t’ung chi ch’i kung-hsien,” Ti-li hsüeh-pao, 28.4 (Dec. 1962): 320-335.

28

23

the Ch’ing government used this waterway frequently to transport grain from Hupeh to Shensi either for famine relief or for military supply.29 In 1900 when the Ch’ing court fled to Shensi during the Boxer uprising and the siege of Peking, even grain from Kiangsu and Chekiang was sent to Shensi by this route.30 Moreover, copper purchased in Yünnan and Japan along with lead purchased in Hankow were also transported by this route to the Shensi mints.31

The conditions of navigation on the Tan-chiang might be improved to some extent by digging out stones frequently as Yen Ju-i noted in the early nineteenth century.32 Unfortunately, there was no information on the number of boats engaged in the government and private commercial transportation. In times of need, Hupeh usually sent 100,000 piculs of rice to Shensi.33 According to Liu Hsien-t’ing, 1,000 boats with a carrying capacity of 100 piculs each would be needed, and at least five times that number of smaller boats would be necessary to transfer the rice further up the river. Since we do not know how many round trips each boat could make, it seems futile to try to speculate further about the real number of boats. Suffice it here to say that the Tan-chiang was a well-used waterway and important in connecting the southern and the northwestern provinces of China.

As for the other navigable tributaries of the Han River, they served mainly in inter-district communication. Among this category, the Yün-ho 溳河, also known as Fu-ho 府河, should be mentioned briefly. This river flowed through Te-an-fu, Hupeh, and was a major communication route between places in the prefecture and Hankow. In the Te-an fu-chih 德安府志 (The gazetteer of Te-an prefecture, 1888), nothing about navigating conditions on the Yün-ho was mentioned, although it was said that the river was the main one in the prefecture.34 According to an investigation by the Peking-Hankow railway survey group during 1936-37, navigation on the Yün-ho might be divided into two sections. From Sui-chou 隨州 to T’ao-jen-ch’iao 道人橋, boats with a carrying capacity of 80 to 90 piculs could ply between this stretch of water from May to August; and from T’ao-jen-ch’iao to Hankow, boats with a carrying capacity of 200 piculs could ply during the same period. In other months, __________

29

Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fang pei-lan, 5: 22-25. Wang Hung-chih, Tso Tsung-t’ang p’ing hsi-pei

hui-luan liang-hsiang chih ch’ou-hua yü chuan-yün yen-chiu (Taipei, 1972), pp. 135-136. For usage of

the Han River in transporting grain in earlier period, see Ch’üan Han-sheng, T’ang-Sung ti-kuo yü

yün-ho (Shanghai, 1946), p. 46. 30

Ch’ing Te-tsung shih-lu (Taipei reprint, 1964), 472: 7; 473: 30b.

31

Hu-pu tse-li (1874), 37: 12b; 22; 26b; 44b; 46. The transport of copper and lead on the Tan-chiang is also mentioned in Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fan pei-lan, 5: 14.

32 Yen Ju-i, San-sheng pien-fan pei-lan, 5: 14. 33

Ibid. 34

Te-an fu-chih (1888), chüan 2, deals with rivers, but it contains names of places by which the rivers pass and gives little information about navigation on them. This is the usual style of chapters on rivers in most of the local gazetteers.

24

only small boats with a carry capacity of 20 to 30 piculs could be used. Going downstream, from Shi-chou to Hankow, it took five days in the high water level period; otherwise, it took ten days. Going upstream, it required ten to twelve or thirteen days. Moreover, it was necessary to use extra laborers on the banks to pull boats when going upstream. Usually, a boat could make seven to ten round trips during a year. There were eight local groups of ship owners who specialized in transportation along the Yün-ho with a total number of boats amounting to 1,900.35 To perceive a more precise idea about junk navigation on the Han River and its tributaries, it is necessary to know the number of boats in existence. It seems likely that there was an increase in number of boats during the late nineteenth century, although it is difficult to know the exact proportion of increase. According to the 1908-1915 Japanese investigations, the number of the ya-shao boats belonging to the Huang-p’i and Hsiao-kan groups totaled about 20,000; the pien-tzu boats belonging to the Chung-hsiang, Tien-men, and An-lu groups numbered about 12,000 to 16,000; the

ch’iu-tzu boats belonging to the Lao-ho-k’ou, Ku-ch’eng, and Yün-yang groups

numbered around 2,000; while the number of the Honan and Shensi groups were unknown.36 During 1936-1937, the Peking-Hankow railway survey groups found that there were in total 50,000 boats serving the Han River. They belonged to the following groups:37

Honan (the T’ang-pai-ho) group: 15,000 boats; Hsiang-yang and Ku-ch’eng groups: 5,000 boats; Hsi-ch’uan (on the Tan-chiang) group: 10,000 boats; Lao-ho-k’ou group: 5,000 boats;

Huang-p’i, Hsiao-kan, chung-hsiang, and T’ien-men groups: 5,000 boats; Hsing-an, Han-chung, and Yün-yang groups: 10,000 boats.

This information shows that boats from the T’ang-pai-ho made up about three-tenths, those from the Tan-chiang about two-tenths, and those from various places on the Han River about half of the total number. Comparing the number of boats belonging to various places along the Han River shows that the number in 1908-1915 was greater than that of 1936-1937. Junk navigation on the Han River reached its height during the late nineteenth century. During the early Republican period, navigation declined mainly due to the instability and disorder in the Han River area according to Li __________

35

P’ing-Han t’ieh-lu ching-chi tiao-ch’a tsu ed., Lao-ho-k’ou chih-hsien ching-chi tiao-ch’a (Tokyo, 1937), pp. 313-315. The original survey was published in Chinese in 1936. Since the Chinese edition was not available in the Harvard-Yenching Library, the Japanese translation was consulted.

36 Shina shōbetsu senshi, IX, pp. 326, 327, 328.

25 Yi-chih and surveys done in the 1930’s.38

The Han River was navigable for about 1,200 km and the total length of its twenty navigable tributaries amounts to about 3,250 km.39 Although some of the tributaries are not navigable during the period of low water level and although they differ in size, these rivers together with the Han River itself really form an extensive network of waterways in the interior of China. Before modern technology was applied to improve the waterways for navigation, there were indeed many natural limitations, but water transport had the definite advantage of being cheaper than land transport.40 Within the framework of traditional economy, the role of the water transport played in the circulation of commodities cannot be overrated.

Organization of the Water Transport system

Studies on the organization of the water transportation system have been done by Japanese scholars for part of the Yellow River, Fukien, Kiangsu, Chekiang, Kiangsi and Hunan provinces.41 These studies show that there were certain general characteristics in the organization of people engaged in water transportation as well as local particularities. In general, there were a certain number of brokers known as

ch’uan-hang 船行 (boat brokers) or p’u-t’ou 埠頭 (“fort heads”) at each important

shipping mart. The function of a boat broker was similar to that of a ya-hang 牙行, that is, he served a middle-man between a ship owner (ch’uan-hu 船戶) and a guest-merchant (k’e-shang 客商). The booker had to be a person who was not a degree holder and he had to have property of some value. He had to obtain a license issued by the pu-cheng-ssu 布政司 (commissioner of revenue) of the province. Every month he had to present to the local yamen a report of his business activities which included names and addresses of guest-merchants and ship owners, passport numbers, and the amount of cargo shipped under contracts negotiated by him during the period. Each year he paid a fixed amount of tax, ya-t’ien-shui 牙帖稅, to the government.42 __________

38

Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao, pp. 27, 83.

39

Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao, pp. 1, 27-30.

40

According to Ferdinand von Richthofen, “Report on the Provinces of Honan and Shansi,”. P. 7, the cost of freight by land is form 20 to 40 times as high as the usual standard on rivers which are easily navigable. According to the Han-chiang shui-tao ch’a-k’an pao-kao, p. 96, during the 1930’s. the cost of freight for one ton of cargo by boat is 20.3 yüan from An-k’ang to Lao-ho-k’ou, while it costs 237.5

yüan by motorcar.

41 Some major studies are: Imahori Seiji, “Shindai iron i okeru Kōka no suiun nit suite,” Shigaku kenkyū, 73 (April 1959): 23-37; Katō Shigeshi, “Shindai Fukken Kōso no senkō nit suite,” in Shina keizaishi kōshō (Tokyo, 1952), II, 585-594; Yokoyama Suguru, Chūgoku kindaika no keizai kōzō

(Tokyo, 1972), pt.3, “Unsōgyō no kikō” (Organization of transportation), pp. 147-210.

42 In the above-mentioned Japanese studies, the most generally quoted passage is from the Ta-ch’ing

lü-li tseng-hsiu t’ung-ts’uan chi-ch’eng (1895), 15: 1. For more detailed discussion on brokers, see

Lien-sheng Yang, “Government Control of Urban Merchant in Traditional China,” the Tsing-hu Journal

26

The sum of the tax paid by brokers of every sort was trivial compared with the land tax which was the main source of revenue of the Ch’ing government by the late nineteenth century. However, the purpose of requiring reports from the brokers was to prevent illegal activities in commerce.43 Available records showed that in practice, reports of the boat brokers really served as a basis for intelligence. For instance, in 1778, investigations in a notorious case of jades smuggled from Yeh-erh-ch’iang 葉耳 羌 in Chinese Turkistan to Soochow involved several provinces. According to a memorial of Ch’en Hui-tsu 陳輝祖 (1732-1783), governor of Hupei, boat brokers in Hankow and Fan-ch’eng provided useful information about merchants who hired boats.44

To serve efficiently as an agent between ship owners and guest-merchants, the brokers prepared contracts in which the following items were included: (1) the names and native places of the ship owner and guest-merchant, (2) the items in the cargo, (3) freight charges, (4) the destination of the ship, (5) the responsibilities for compensation, (6) the responsibilities for paying native customs duty, (7) the commission for the broker, (8) the names and signatures of the broker and the ship owner, and (9) the date.45

A style sheet of a contract dated May 15, 1887, is shown on the following page (see Plate 2). It was prepared by a broker in Hankow. A pien-tzu boat belonging to a ship owner from Hsiang-yang was hired by a guest-merchant bound for Lao-ho-k’ou. The cargo entrusted to the boat consisted of trunks of books and clothing, with miscellaneous items carried by the passenger himself. The ship owner guaranteed to keep the cargo dry. If there was any damage, he would redeem the owner of the goods on the basis of their price in the originating port at the time of departure. The freight charge was 26 strings and 500 cash of the chiu-pa-ta-ch;ien 九八大錢 or “980 cash string.”46 Twenty strings and 500 cash of this amount paid to the ship owner while the broker acted as witness and the remaining amount of 6 strings was to be paid en route. The freight charge did not include the native customs duties. The passenger paid duties on his own belongings while the ship owner paid ship fees. However, fees for worshipping the river gods along the way were included in the freight charge. In addition, each passenger had to pay 60 cash per day for food on the boat. In this contract the amount of the commission for the broker was not indicated.

__________

43

Also see Lien-sheng Yang, “Government Control of Urban Merchant,” pp. 193-199.

44

Shih-liao hsün-k’an (Taipei reprint, 1963), p. 544. The case involved is the Kao P’u ssu-yün-yü-shih-an (the case of smuggling jades by Kao P’u).

45

Yokoyama Suguru, p. 159.

46

For a discussion on the “980 cash string”, see Lien-sheng Yang, Money and Credit in China (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1952), p. 35.

27

Plate 2: A style sheet of contracts prepared by boat brokers

Source: Tōa Dōbenkai, Shina keizai zensho, IV, p. 455.

According to another source, the commission for the boat brokers in Hankow was normally 13 percent of the freight charge, but it could go up as high as 16 percent. The commission was received directly from the ship owner and not from the guest-merchant.47 The rate of commission originally set by the Ch’ing government for every place was 3 percent.48 In practice, however, it was often higher than the official rate. For example, in 1804, when Fukien brokers required a commission of 10 to 20 percent, it was considered too high. Therefore, the Fukien official regulations set the rate at 6 percent. In 1871, Kiangsu brokers exacted as much as 30 to 40 percent and so the officials passed regulations setting a maximum charge of 12 percent.49 The rate of __________

47 Mizuno Kōkichi, p. 211; also see Shinkoku jijō, I, 987. 48

Yokoyama Suguru, pp. 154-155. It is mentioned that in the T’ien-t’ai chih-lüeh, chüan 1 and the

Hu-nan sheng-li ch’eng-an, chüan 23, the official rate of commission was set at 3 percent. 49

Yokoyama Suguru, p. 154, the Fu-chien sheng-li, chüan 22; and the Chiang-su sheng-li hsü-pien, item of the year 1871, are quoted.

28

the commissions in Hankow were higher than the official ones of Fukien and Kiangsu. However, the Hankow rates available dated from the 1900’s, and this decade witnessed the most inflationary phase during the Ch’ing dynasty.50 the actual value of the commission at Hankow might not have been too high. While the Hankow rate might have exceeded the officially set rates in other provinces, even the highest rate in Hankow, i.e., 16 percent, did not exceed some of the exorbitant commissions sought by brokers in Fukien and Kiangsu.

During the 1900’s, there were 23 well-known boat brokers in Hankow. Twelve of them were in charge of the water transport between Hankow and Hunan, and the other eleven specialized in the transportation on the Han River.51 Due to the scarcity of information, nothing can be said about the boat brokers at other shipping marts along the Han River.

As for the organization of the ship owners and their relationships with the crewmen, we also have very little information recorded for the Han River waterway. As mentioned above, boats belonged to different groups defined by their locales. According to the Hsia-k’ou hsien-chih (1920), there were four guild halls (kung-so 公 所) established in Hankow by the ship owners of different local groups. The Hsiao-i kung-so 孝 邑 公 所 was set up by the Hsiao-kan group in 1863. The Ho-nan ch’uan-pang kung-so 河南船幫公所 was set up by the Nan-yang, Hsin-yeh 新野, and T’eng-chou 鄧州 groups in 1874. The Huang-p’i kung-so 黃陂公所 was established by the group from Huang-p’o in 1883. The Shang-ch’uang kung-so 商船 公所 was established by the Han-chung, Hsing-an, and Yün-yang groups in 1903.52

Although no further information about the functions of these guilds was recorded in the same gazetteer, it seems likely that they were not very different from those of water transport organizations at other places. Imahori Seiji found that the ship owners’ guild at Nan-hai-tzu 南海子, a shipping mart in the middle part of the Yellow river, had the following roles: (1) to manage the wharves, (2) to take charge of the administrative matters involved in water transport, such as registration of ship owners and crewmen, and to serve as an agent between the guild members and the officials, (3) to arbitrate disputes, and (4) to promote public welfare.53 As the guild system was a common phenomenon in the pre-modern Chinese society, 54 these functions of the ship owners’ guild might also be applicable to those founded in Hankow.

__________

50

Yeh-chien Wang, “The Secular Trend of Prices during the Ch’ing Period (1644-1911),” the

Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 5.2 (December

1972) : 361.

51 Mizuno Kōkichi, pp. 209-210; also see Shinkoku jijō, I, 987. 52

Hsia-k’ou hsien-chih (1920), 5: 28; 29; 31. 53

Imahori Seiji, pp. 31-31.

54 For general studies on this subject see, Ho Ping-ti, Chung-kuo hui-kuan shih-lun (Taipei, 1966); Negishi Tadachi, Chūgoku no girudo (Tokyo, 1953).

29 Trade on the Han River

CHAPTER THREE

PRODUCTION AND TRADE OF CASH CROPS

In general, grains were the staple of farm production. In the nineteenth century, food supply in the Han River area was at least sufficient during normal years (see appendix). This was the basis on which the production of cash crops developed. As mentioned before, along the upper Han River, the cash income of farming households in the valley depended on growing a few mou 畝 (1 mou = 0.16 acre) of tobacco, turmeric, or medicinal herbs, while those in the mountains relied on rearing pigs. Thus, even in the remote mountains, peasants devoted some effort to producing cash income. In local gazetteers, there is usually an entry of huo-shu 貨屬, or “commercial goods,” in the section dealing with local products. Occasionally, specialties of certain villages or towns are also mentioned. The general impression is that the peasants were market oriented, although the intensity of marketing varied in different places and cannot be measured precisely.

In this chapter there will be no attempt to analyze land utilization and cash income of individual farms because this sort of information is almost non-existent for the period and region under study. Instead, the focus will be on notable cash crops, which were produced in the Han River area and were transported over the Han River. Some cash crops were produced on the plains while others were produced in the mountains. The items to be discussed in this chapter are beans, sesame seed, tea, tobacco, turmeric, fungus, and other mountain products such as wood oil, varnish, and vegetable tallow.

Both qualitative and quantitative data will be used to describe and analyze the tendency of development. Although the development of each crop involved different places and followed a slightly different pattern, general trends can be observed. On the one hand, the progress of commercialization was accelerated during the late nineteenth century owing to the new developments in processing industry that called for a larger demand for raw materials. Thus, despite fluctuations in prices, the exported volumes of soybeans, sesame seed, tobacco leaf, wood oil, and vegetable tallow were increasing. On the other hand, the development of certain products, which supplied mainly the domestic market, was limited because the demand was rather stable. The production levels of fungus, varnish, and prepared tobacco indicated this tendency. Foreign merchants were involved in some way with the trade of most