HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTlONS JN DEPRESSION: INVESTlGATION OF ONE POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN :臺灣師範大學教育心理輿輔導學系

心理學報,民帥, 28 期, 251-284 頁

• 251

Helplessness and Self-Blame Attributions in

Depression: Investigation of one Possible Resolution

of This Paradox

Am

ong College Students in Taiwan

Li-chuan Wu

Depr自sed per品ns often feel helpless to change their environrnent, and at the sarne time blame themselves for being the cause of misfortune旬 Paradoxi且IIy. 出ey believe 出ey have no effed on events, and in another 盟n盟 they believe 出ey have powerful effects. The p呻啤 of 出is 削y W:品 to examine a 悶。,lution of this paradox 吋ered by Janoff~Bulman's mo:l.el of self~bl自由 attributions for depression which distinguishes between "behavioral self~blame" and "characterological 盟If~blame". 1n 出i5 study. college students in Taiwan were administered three Chinese versions of instrumen恆, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Attributional Style Questionnaire -- a measure of help1essne詣,

and the Self-Blame Scale. of 1443 students who returned surve戶, a stratifîed 詛mple of l∞o participants was ana1yzed.

Six res且rch hypotheses were derived from Janoff-Bulman's model. Correlational evidence supported four of the six. 80th genera1記lf-blame and helplessness were signifi-cantly p個itively correlated with depre回ion. These findings support 抽出Beck's and SeIign祖n's mo:l.els of depression, and support the existence of the paradox of belief in which depr臼sed persons feel 出自 help1ess and self-blame about 恤E 詛me event.

As predicted by Janoff-Bulman's mo:l.el, charactero1ogical self-blame was signifi-cantly ∞rrelated wi出 depression and helplessness. However, contr且可 to predictions,

behavioral 且匠 ~blame was 刮目 significantly p閏itive!y ∞πelated 咐th depression and he!p 1essne且 τhus, findings of 出is study 別pported Janoff-B世man's mode! of self-bl缸ne wi血 regard to assumptions about characterologi,且1 self-b1ame, but not wi血 regard to

ass山nptions aoout behaviora1 self-hlame.

Addition剖 exploratory multiple-regression analyses found 出at helplessness and

char-aderolo刮目l 記lf-bl血ne were signifi目前 pr'甜icto周 of depression. Each uniquely pr吋icted

about 5% of the variance in depression. However, behavioral self-bl目ne,accounted for

on1y a trivial. amount of u吋que variance. Additional1y, depression and ch且racterologi且l self -blame were signifi阻nt predictors of helple自ne盟, uniquely explaining 5% and 4% of 出e varian間, respectively. Again, behavioral 能lf-bl缸ne accounted for only a 仕ivial amount of unique va討ance﹒ Results of 出is study provide support for an assocîation between charaderological self-blame, helplessne品, and depression. Implica tions and lîmi ta -tions of these findings, as weI1 as suggestions for further research are discu

• 252 • 教育心理學報

INTRODUCTION

Why do p田ple who feel helpless and powerless think that whatever they try wil1

fail? How can they feel 田 powerful in their helplessness? How can individuals

blame themselves for outcomes over which they have no control? Depres扭d persons often feel helpless to change their environment, and at the same time assume responsi-bility for the outcomes of negative events. Paradoxically, they believe they have no effed on events, and in another sen居 they believe they have powerful effects.

Selig-man's learned helple扭扭扭 model of depression and 區ck's ∞gnitive model of

depres-sion result in a paradoxical situation. It is propo8吋 that a view of depressed persons as both helple自 and self-blaming is theoretically paradoxical. This research is intend吋

to examine one po盟ible re田lution and the c1inical impli且tions of this paradox.

Seligman's helplessness model which holds that depression involves a feeling of helplessness in which depressed persons' learn that outcomes are independent of

respon盟s CBarnett & Gotlib, 1990; Brown & Siegel, 1988; Hiro恤, 1974; Lester, 1989; Seligman, 1975). Furthermore, the attribution-based second generation of helplessness

th凹ry CAbramson, Se1igman,

&

Teasdale, 1978) proposed a reformulated learned help-lessness mooeI. This m吋el proposes that a negative explanatory or attributional s可lecan precipitate the development of depression (Gong

&

Harnmen,

1980; Peterson,

Schwar缸, Seligman, 1981; Peter田n & Seligman. 1984) or have a substantial impact on individual's coping and posttraumatic adjustment (Meyer & Taylor. 1986). Additionally,Beck (1967, 1976) proposed that dpression is charaderized by negative 盟ts. selt-blame, and self-punishment and depres盟d individuals inte叩ret their experience in terms of continuing self-blame, personal deficiency, and negative expectations. Abramson and Sackeim (1977) pointed out that when combined, Seligman's 1四med helplessness m吋el

of depression and Beck's cognitive model of depression constitute a paradox. They have proposed that to view depressed persons as both helpless and self-blaming is

th臼reti也l1y paradoxi且1.

Abramson and Sackeim (1977) and Peterson (1979) explored 田me possible resolu-tions of this paradox. 臼le possible 扭曲lution of the paradox, and the focus of the

p扭扭nt study

,

is Janoff-Bulman's m吋el of self-blame attributions. Janoff-Bulman (1979) believed that "characterological" 但HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTIONS lN DEPRESSION: lNVESTIGATION OF ONE

pOSSIBLE RE叩LUTIONOF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS 的 TAIWAN

253

instance

,

"It happened to me because 1 am the 四rt of per田n to whom such things happen." This distinction is u盟ful in that it resolves the contradictory evidence that self-blame can be a predictor of good coping among accident victims (Janoff-Bulman & Wortman, 1977), can be as臨iated with more effective post-rape adjustment (J anoff-Bulman, 1979), while at the same time being commonly considered a correlate of depression. Janoff-Bulman (1979) suggests that behavioral 盟lf-blame may promote a general belief in one's ability to avoid a recurrence of negative outcomes and effect positive outcomes in the future, which is an adaptive respon扭﹒ Characterological self blame, conversely, involves focusing more on the past and what it was about them that rendered them deserving of the negative outcome for which they are blaming themselves, which is a maladaptive response (lv咀ller, & Porter, 1983). 1n the case of rape,

for instance,

a woman can blame herse1f for having walked down a str自t alone at night or for having let a particular man into her apartπlent (behavioral 盟1f -blame) ,or she can blame herse1f for being "t∞ trusting and unable to say no" or a "careless

per田n who is unable to stay out of trouble" (characterological self-blame). The biggest differences 世tween the self-blame attributions may be captur,吋 through the use of a controI1ability dimension. Because p田ple can exert control over behavior but can do so far less over their personality, these categories of blame differ in control1 a-bility (Carver, Ganellen, & Behar-Mitrani, 1985; Weiner, 1974). Besides the perceived controllability dimension, the other two dimensions of signifiCance distinguishing these two types of -self-blame are the stable-unstable and global-specific dimensions which contribute to peræiv,吋 control. Behaviorally attributed bad events were s的1 as more control1able and their cau盟s less stable and less global than were characterologically attributed bad events and their causes (Peterson et al., 1981). Ch可acterological attribu-tions for bad events were more global and stable than behavioral attribuattribu-tions.

A munber of studies have found that self-blame and helplessness contribute inde-pendently. to depression CBeck, -Rush, Shaw & Eme可, 1979; 區ck & Weishaar, 1989;

Coleman & Beck. 1981; Wener & Rehm, 1975). However, a review of the literature (Abramson & Sackeim, 1977; Pe胎r田n, 1979) reveals very few studies that have been

254 • 教育心理學報

located that empirically tested how J anoff - Bulman' s 盟lf-blame attributions model can

扭曲lve the paradox in depression. Therefore, the present study is. designed as an exploration of the role of Janoff-Bulman self-blame model in resolving the depression paradox and to determine whether characterological self-blame is a distinguishing char-acteristic of dep扭扭吋 individuals.

To understand self-blame attributional styles in depressed students have both th臼

retical and clinical implications. If the m吋el presented in this study can be suppor紐d,

theoretically, it. implies that attributions may influence adjustment. The findings could

刮目 identify potentially useful clinical interventions, and have implications for coun-selors who work with victims or depressed p凹ple. Treatment strategies typical1y emphasize providing a nonjudgmental atmosphere for victims that actively discourages self-blame. If, however, behavioral self-blame is as田ciated with greater f田1ings of control and better functioning, counselors might n自d to reconsider this treatment strat egy CFrazier, 1990). Coun盟10rs might increase clients' sense of controllability and encourage appropriate

,

adaptive self-blame.Purposes of This Study

The pre世nt study examines the features of this po自ible incompatibility. between views of depression. The study has several major purposes: (a) to examine the empir-ical existence of the paradox; (b) to place particular emphasis on a reso1ution of the paradox of helplessness and self-blame in depression by examining Janoff-Bulman's model of self-blame attributions for depression; (c.) to test the usefulness of the distinc-tion 出tween two 句rpes of self-blame, behavioral 盟lf-blame and charactero10gical self-blame, in the area of depression, and Cd) to test whether behavioral self-blame attribu-tions has a positive, adaptive function.

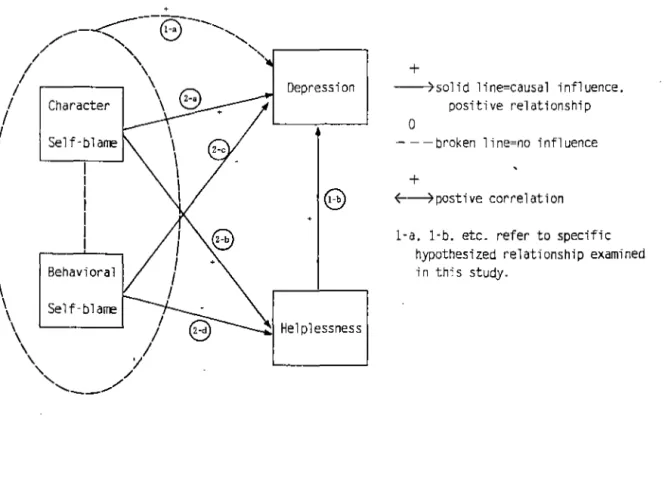

A Diagram of the final hypothesized resolution of the paradox in depression, . based on J anoff- Bulman m吋el, is presented in Figure 1. This model was used in the current study to examine the paradox and al田 investigate the possible resolution for the paradox with a Taiwanese 旦mple. Specifically, the r自由rch questions and hypothe-ses in this study were:

1. Research hypotheses examining empirical existence of the paradox: The id盟

to examine the paradox is by investigating the relationships among self-blame a仕ribu

tions, helplessness and depression.

Hypothesis l-a. There is a significant positive 扭曲ciation betw田n general 盟:lf

blame attributions 且nd depression.

Hypothesis l-b. . There is a significant positive association between helplessness. and depression.

2. Research hypotheses testing the resolution for the paradox: The 血可

research question prop田ed to investigate Janoff-Bulman's m吋el by dividing self-bl訕訕e

into characterological 阻'lf-blame, and behavioral 盟lf-blame.

Slon.

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF -BLA阻 ATTRIBUTIONSIN DEPRESSION: 的VESTIGATION OF ONE POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS 的 TAIWAN

• 255

Hypothesis 2 -b. Characterological 扭lf-blame is positively ass田iated with helpless-ness.

Hypothesis 2-c. Behavioral 盟lf-blame is not significant1y associa扭d with depres-slOn.

Hypothesis 2-d. Behavioral self-blame is not significantly associated with helpless-ness.

In addition to the six hypothe盟s describE吋 abo嗨, the foIIowing exploratory

扭扭arch questions were al田 examined: Among the盟 three variables (charaderological self - blame, beha vioral 盟lf-blame, or helplessness) which predicts the greatest (highest) unique amount of the variances in depression? Which of these three variables (charac-terological self-blame, behavioral 盟lf-bl扭扭, or depression) predicts the most unique amount of the variances in helplessness?

Depr巴ssion

+

一一一→ solid line=causal influenc巴. positive relationship

O

- - - broken 1 i n巴=no influence +

G

←→ p叫ive 帥的tiHelpl 巴ssness

l-a. l-b. etc. refer to specific hypoth巴sized relationship examined in this study.

• 256 • 教育心理學報

METHODOLOGY

Participants

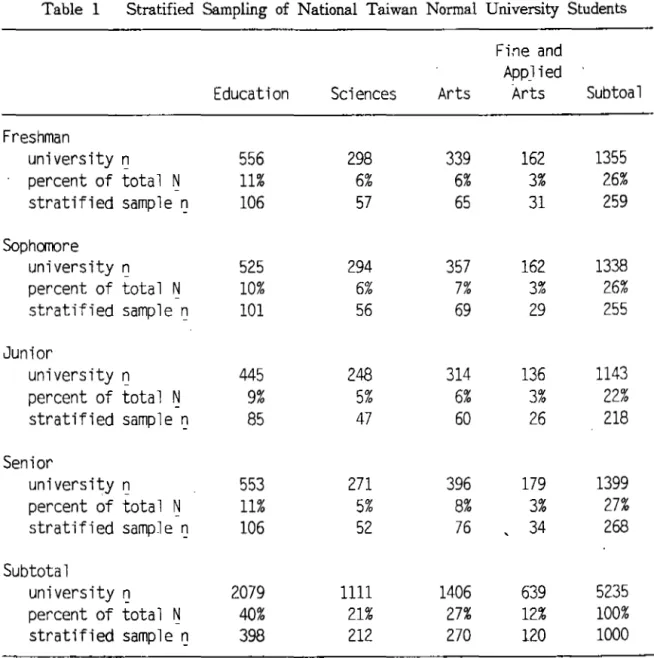

Participants in this study ∞nsisted of 1000 students chosen from the NationaI Taiwan Normal University (NTNU). The university in the first semestεr of 1993 had an enrollment of approximately 5235 undergraduate students. The university population consists of 16 groups based on ∞llege 血1d grade variables. These are pre盟nted in T

a:

ble 1. For the p叮pose of representativeness of the selected sample two c1assification variables,

col1ege and grade,

were u盟d to stratify the 田mple. Table 1 presents thes仕atified 盟mpling of NTNU students. 1n order to obtain a final sample of 1000 partic-ipants, it was necessary to distribute more than this number of packets. Survey

pack-ets were distributed 臼 1443 undergraduates enroll吋 in NTNU.

Students participation was voluntary ,!-nd students were assured that their

respon盟s would reIl1.ain anonymous. Inspecting: the da臼 from all participants revealed that respon盟s from 49 of the 1443 were not usable due to careless, incomplete, or haphazard responding. The final valid 盟mple contained 1394 students. A random pr世e

dure was used to e1iminate ca堅s from each cell and reduce the final 田mple to 1000 students in the correct proportions required for stratification.

Instruments

students were administered a survey packet which contained the translated Chinese versions of thr,自 instruments: the B血k Depression 1nventory, the Attributional Style Questionnaire

,

and the Self-Blame Scale. An臼臼blished standardizecl Chinese translation of Beck Depression 1nventory was available CKo,

1989). The remaining two instruments were translated into Chinese by the author.kck Depression Inventorγ (BDI)

The Beck Depression 1nventory CBDI; Beck, 1967) is a 21-jtem self-report inven-tory used to m目sure depth of depression. Participants are asked 臼 read 21 multiple choice items, and each item consists of four statemen缸, scored on a range from 0 to 3. Participants are directed to ∞mplete each item in terms of how they felt "during the past week, inc1uding today." A total sco呵, ranging from 0 to ,63, is obtained by summing the items. The greater the score, the greater the 盟veri可 of depression. 1n this study

,

a standardiz世 Chinese translated ver剖on (BDI-C) was used (Ko,

1989). The Chine盟 version of the Beck Depression Invent。可由DI-C; Ko,

1989) is a 21-itemself-rep叮t invento叮T, adapted from the BD!. The content, format, and scoring of the BDI-C were the same as the original BD!. Ko (1989) ∞nducted reliabili句T and validity studies of the BDI -C and rep叮ted that the instrument exhibited high internal consis-tency reliabîlity as measured by Cronbach's alpha (.89) and 刮目 had good concur問nt

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTIONS IN DEPRESSION: INVESTIGATION OF ONE 257 • POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS 的 TAIWAN

Table 1 Stratified Sampling of National Taiwan Normal U世ve自ity Students Fine and

AppJ ied

Education Sciences Arts Arts Subtoal

Freshman university 可 556 298 339 162 1355 percent of total

N

11% 6% 6% 3% 26% stratified sample n 106 57 65 31 259 Sophαnore university 可 525 294 357 162 1338 perce門t of totalN

10% 6% 7% 3% 26% stratified sample ~ 101 56 69 29 255 Junior university ~ 445 248 314 136 1143 percent of total ~ 9% 5% 6% 3克 22克 stratified sample n 85 47 60 26 218 Senior university ~ 553 271 396 179 1399 percent of totalN

11% 5 克 8% 3克 27% stratified sampJ 巳 q 106 52 76 34 268 Subtotal university 門 2079 1111 1406 639 5235 percent of totalN

40% 21% 27% 12% 100% stratified sample ~ 398 212 270 120 1000The Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ)

The Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Peterson et al., 1982) is

a

12-item盟lf-adminis胎red questionnaire which as盟S揖s Seligman's conceptua1i詛tion of p宙間ived

control Oearned helple宙間ss). 四le ASQ consists of 12 hypotheti臼1 situations with. six of the situations describing bad outcomes and six describing g回吋 outcömes. Su吋ects

are asked

to

respondto

questions fol>owing each situation that tap the intemal/exter-nal, s阻ble/uns且ble,血d globallspecific dimensions of attributions.. A number ofdiffer-ent suhscale scor自 and ∞nsturcts can be derived from the ASQ. For this study only the hopelessness composite s∞re was used. 1n this study the hopelessness construct was ∞nsidered equivalent to helplessness. Although there may be important dîfferences in nuance, a close reading of Seligman and other's writings indicate that the terms

• 258 • 教育心理學報

can be used interchangeably for the pu可0盟 of this study. In the current study, the

ASQ was translated into Chinese (ASQ-C) for use by the Taiwan 且mple. It is

included in this study as a measure of helple田ness. The translation pr∞ess involved forward and backward translations with evaluations of linguistic and psychological content by bilingual professionals in counseling psychology. A two-way reverse transla-tion method was used to es個blish reliabili可. There is a high level of similarity

betw阻n the扭 two translations, thus providing eviden白 for the accuracy of 甘anslation.

General1y speaking, the con扭I祉, format and scoring of the ASQ-C were the same as the original ASQ. The evaluation of cross-cuItural e中ivalence of the 廿血slated version

was achieved through the administration of 胎出 the original and the translated

Chinese forms of the ASQ 扭扭扭nior Taiwanese college students majoring in

Eng1ish. The 扭quence of administration was counterbalanced. Very high correlations were ob個ined betw自n the English and Chinese forms for each scale , ranging from ~

= .79 to ~ = .94. They provided evidence for the translation equivalence. The 且me

sample of 30 students was u盟d to ob臼in data for test-retest correlations. The ASQ-C was administer吋 ase∞nd time three weeks later. These correlations ranged from a low of r

=

.62 臼 a 品igh of I=

.92. The intemal consistency reliabili句T as measured by Cronbach's alpha ranged from ~=

.36 to I =且9. The盟 findings suggest low inter-nal reliability for the individual attributiointer-nal dimensions, but higher reliabilities oncomposi妞缸。æs. The results of the ASQ-C are consistent with the r自ults reported by Peterson et al., (982) and P,目前回n and SeIigman (984), who noted 出at 出ese

composite sc刮目 of the ASQ have consistently proved to be more reliable and valid than the individual dimension scores due to the greater num世r of items involved. Only the Hopelessn四s ∞mposite score is used in this study 臼 measure helplessness. For this ∞mposite the ∞叮"elations between the ASQ and the ASQ-C was r

=

.94. and Cronbach's alpha coefficient for reliabiIity was .87. Additionally, it also showed a test-retest reliability coefficients of .90.Janoff-Bulmans Self-Blame Instrument (SBI)

The Self-Blame Instrument (SB!) was a 4-item self-report instrument which

as扭扭es Jano叮咀咀lman'sm吋el of self-blame attributions. It was developed for a particular re盟arch s旭dy by Janoff-Bulman. The SBr consists of 4 hypothetical scenar-ios

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTlONS IN DEPRESSION: INVESTlGATlON OF ONE POSSlBLE RESOLUTION OF THlS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS 的 TAlWAN

259 believe that you could avoid what happened in this 固堅?" Self-blameπ扭曲叮es were summed across the four scenarios.

In the pre盟nt study

,

the author adap胎d Janoff-Bulman's self巾lame instrumentwith several revisions made and translated into Chinese (SBS-C) for !l Taiwan sample.

Thr田 m吋or modifications have been made in the SBS-C. The first change is to change scenarios from four to eight to generate more cult叮a11y appropriate scenarios.

The 且∞nd modification is to clarify and elabora扭 the characterological and behavioral self-blame items for respondents. The third change is to change the way of scoring. Both 'test-retest and c扭扭icient alpha reliabi1ity coefficients were calculated to estimate the reliability of the SBS-C. A group of 42 Edu'目tional Psychology and Counseling

majors were administered the SBS-C. Two w四ks la尉, 38 were available 出 complete

the SBS-C again. It shows that retest reliabi1ity c叫ficients over two w甜{s for the

SBS-C subscal,田 ranged from r=.70to t=.88.The internal consistency of the SBL

C was asses且d by calculating coefficient alpha based on the first 盟mple of 42

partici-pants. 1t shows that c田fficients for characterological 扭扭-blame 血d beha吋oral

self-blame were satisfactory.

Da ta Collection Procedures

The survey packet was administered in a classrl∞m setting to groups of students at the regular tirtie and location of their c1ass meetings. To reduce the impact of assessment r田ctivity and order effects, the order in which the instruments was changed to ∞ntrol for re呵。n盟 bias. The participants returned the packet after they finished in their classes.The instruments t∞k about thirty to fifty minutes to

complete. Data was electronically coded using an IBM PC 串串top computer, and

analyzed using the SPSS statistical package for the IBM Windows environment.

RESULTS

In this study, a stratified 田mple of 1000 college students was administered three Chinese versions of instruments (BDI -C

,

ASQ-C,

and SBS-C). Data were available for each participant concerning 20 scale and subscale scores. Although not all of the扭 曲旭 are relevant to the specific research questions posed in this study,

means and standard deviations for all subscales are provided in Table 2 for the reference of otherresearchers who may be interes胎d in establishing norms for TaiwaIie田∞llege

students on th自e scales. Separate normative da阻 for men and women are pro吋ded.

Because of the large sample si揖 and statistical power to detect differenceS, only mean differenæs significant at the p < .001 level are reported. Table 2 sho

w'

s that there was only one significant gender difference regarding a variable of 可自ific interest to the research qu自tions in this s個dy. Women were significantly more 1ikely to make behavioral self-blame attributions. Interestingly there were no significant gender differ-enæs in depression.教育心理學報

• 260 •

Tests of Research

H

ypotheses()f the six hypotheses in this study, the first two examine the empiri臼1 existence the paradox, that is, do per田ns who are depressed tend to f曲1 both helpless and themselves for negative events? .The four remaining hypotheses test a possible for the paradox. To perform hypothesis tests, Pearson product~moment correla~

目前吋 out. of blame ωlution tions were and Number of Standard Deviation

,

Possible Range of Values,

of the Scales Administered in This Study The Mean, Items Table 2 Wαnen (n "" 675) Men (n "" 325) scale range M SO 問 SO

t

Scale/Subscale nH nu .可 ln 川 qu 門 V RU4I P 』 qH rvds nyF 自由」 戶』 nvFs nυ+Lnv ne uk 白」 hU F」 MV en n 口 T4 .84 3.45* - .69 .45 . - .05 .26 -1.22 -2.55 -2.32 1.25 1.57 6:23 .68 .78 .98 1.49 .73 .66 .84 1.28 1.87 1. 76 10.35 4.43 4.05 4.07 8.13 4.84 5.11 4.94 10.05 12.56 14.89 " 6.44 .79 .80 1.09 1.60.77

.69 .91 1.33 2.04 1.86 10.70 4.60 4.02 4.10 8.12 4.85 5.06 4.79 9.85 12.72 14.7o -

63 A 『 A 斗,可 i14 可 JS 勻,, 7/1 止可',寸,, 7' , 14 門/」門/』 一『 E 』 EE---F 1414 可 i? 』 141414 門 thJqd Attributional Style Questionnaire Internal Negative Stable Negative Global Negative Hopelessness (HPLSð ) Internal Posiitive Stable Positive Global Positive Hopefulness Composite Negative Composite Positive Composite Positive Minus Composite Negative (OEPq) -2.02 2.52 2.33 2.73 1.98 -18 - 18 -1.18 -3.56背 .56 .73 3.42 1.71 .64 .79 3.37 1.53 0-5 0-5 - .99 - .98 .82 .96 2.25 2.17 .87 .98 2.19 2.1 。- 5 0-5 -1.26 -3.67 肯 - .35 -1.90 .87 .58 .60 .62 2.14 3.27 2.36 2.97 .94 .66 .69 .72 2.07 3.12 2.35 2.89 。- 5 。- 5 0-5 0-5 Self-BlaπE General (GSBð )Blame of the Other、

Blame of

Enviro門ment

Blame of Chance Char,acter‘ological Se lf -B 1 ame ( CSB司) Behavioral Self-Blame (BSBð) Oeservingness (OES) Avoidance (AVO) Scale Self-Blame

司 variable involved the hypothese testing

HELPLE岱NESSAND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTIONS IN DEPRESSION: lNVESTIGATION OF ONE

POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARAÐOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

Research Hypotheses on Examining the Paradox

- 261

甘le existence of the paradox would be 叩pport吋 by finding of a significant pos卜 tive ∞rrelation among self-blame attributions, helplessness and depr,自sion. Results are shown in the top row of Table 3. Hypothesis l-a predicted that there would be a significant positive correlation between general 揖lf-blame attrîbutîons and depre品ion.

The result indic1ites that this hypothesis was supported, I :;:: .17, 2 < .001. However, a correlation of .17 is actual1y fairly low. 1n a smaller 盟mple, it would not have bE割l

significant. Thus, the support for hypoth田is l-a was not ve:可 strong. Hypothesis 卜b

predicted that there would be a significant positive association between helplessness and depression. This hypothesis was also supporb吋, r =詣, 2 < .001. Therefore find-ings of the present study pro吋de tentative support for the existence of the "depressive paradox."

Research Hγpotheses Testing:

A

Resolution For The ParadoxThe 扭∞nd 盟t of re盟arch questions proposed to investigate Janoff-Bulman's model of self-blame by dividing self-blame into characterological self-blame, and

behavioral 揖lf-blame. The first two rows of Table 3 provide a test for hypotheses 2-a and 2-b

,

namely,

that characterological 盟lf-blame would be significantly positively associated with depression C2-a) and helplessness C2-b). Results show that characterolog-ical self-blame was significantly positively correlated with depressîon,

~ = .34,

e

<.00

1,

and was al曲 significantly positively coπe旭ted with helple申n前已空=品, 2 <.001. Thus

,

both hypothe扭s received strong support.T'able 3 Correlations Testing the Depr'四sion Paradox, and a Possible Re血lution

DEP HPLS 由3 臼B B詔 DES AVQ

區pression Helplessness General Char、acter Behavior Deserv- Avoidance Self-Blame Self-Bl 研E Self-Bl 部e ingness

DEP Depression .33會 .17宵 .34會 .17會 .31會 -.19* HLPS Helplessness .25會 .36會 .25有 .39會 -.18會 但B Gene內 1 Self-Blame .52會 .63* .28世 -.01 已B Character Self-Blame .39有 .51會 -.20會 BS8 Behavior Self-Blame .35:"" .07 DES Deservingness -.30* AVQ Avoidance Note. N=lα)() 會 p

<

.∞l• 262 • 教育心理學報

J anoff-Bulman's model predicts that behavioral self-blame would not be signifi-cantly 扭曲ciated with depression (hypothesis 2-c) or helple品ness (hypothesis 2-d). However, results shown in the top two rows of Table 3 indicate that behavioral self-blame was found to be significantly positively correlated with depression, "!:

=

.17, and with helplessness,空= .25. Thus, these results fai1 to support an important element ofJano缸-Bulman's model, that behavioral self-blame can be distinguished from charadero-logical self-blame in regard to association with helplessness and depression.

The va1idity check for the Janoff-Bulman's self-blame attributions model: It is

po盟ible to u盟 the "區servingness" and "Avoidance" (perceived avoidability) subscales

from the SBS 臼 provide a validity check for Janoff-Bulman's self-blame mode1.

Ac∞rding to the model, per田ns high in characterological 盟lf-blame should al回 e油ibit high levels of "De盟rvingness" and low in "Avoidance" of blame. Conver阻ly,

the model predicts that per自由 high in behavioral 盟lf-blame should tend to exhibit high levels "Avoidance" and low levels of "De前vingne盟" for blame. The final group

of ∞rrelations shown in Table 3 provides mixeâ support for these checks on validity. Characterological self-blame

,

as e}中配ted, was significantly positively ∞付elated with deservingness ("!: =品,:e

<.001) and significantly negatively 扭曲ciated with avoidance(~= -.凹,

:e

< .001). However, contra可 to expectation behavioral self-blame was not associated with avoidance, and was significantly positively associated with de盟rvingness (r

=

.35,::e

< .001). These results call into question the validity of either the construct of behavîoral self-blame itself, or the accuracy of measurement in this study.Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses

Finally

,

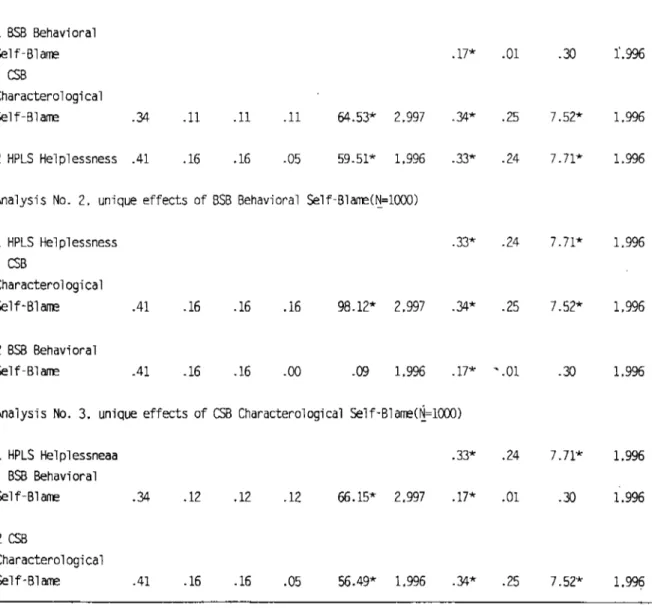

two 位:plo阻torγ 阿盟!arch questions w它re p叮叩吋臼 de但rmine whichvari-ables are the best unique predictors of depression and helplessness. Two sets of hierar-chical multiple regression analyses w叮e ∞'nduded. In the first, depression was the criterion, with charac胎rological se1f-blame, behavioral self-blame, and helplessness as the predic的rs. In the 醫∞nd, helplessness was the criterion, with characterological

self-blame,世havioral self-blame, and depression as the predidors.

The first r曲詛咒h question was pursued with a set of three hierarchical

regres-sion analy臨 U甜 to predict depression. Each of the thr自 a田lyses was identical

,

eXI臼pt that the 腔中聞自 of entry for the three predictor variables was varied so that each was en恆red-last în one of the three analyses. The last step of the hierarchical regression pro吋des a test for the unique varian白 accounted for by that predictor, after accounting for the variance associated with the other two predictors.

Results of the first 盟t of regression are shown in Table 4. The increment in R 2 in the last step of each analysis indicates the unique variance accounted for by the

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRffiUTIONS IN DEPRESSION: INVESTIGATION OF ONE POSSlBLE RESOLUTlON OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

263

Table

4

Hierarchical Multiple Regr自sion Predicting Depression from Characterolo~ gical Self~ B1ame, Behavioral Self~ Blame, and HelplessnessIncrenent F

St叩 N urrt:Jer R R2 Adj. R2 i n R2 chang陪 (df) 「 Beta t (df) Analysis No. 1. uniq肥 effects of HLPS Helplessness (~~1000)

1 BSB Behavioral

Self-Bl 創刊E .17會 .01 .30 1.叩6

已B

Charact巴rologi cal

Self-Blaræ .34 .11 .11 .11 64.53會 2.997 .34有 .25 7.52會 1.996 2 HPLS Helplessness .41 .16 .16 .05 59.51會 1.996 .33會 .24 7.71會 1.996 Analysis No. 2. unique effects of BSB Behavioral Self.Bl 創世 (N=lαXl)

1 HPLS Helplessness .33會 .24 7.71會1. 996 已B Char、acterolo日 ical Self-Bl 研E .41 .16 .16 .16 妞 .12會 2.997 .34企圖 25 7.52* 1.996 2 BSB Behavioral Self-Bl 出E .41 .16 .16 .00 .的1. 996 .17* 、 .01 .30 1.996

的alysis No. 3. unique effects of CSB Characterological Self引冊(也=1000)

1 HPLS Helplessneaa .33會 .24 7.71* 1.996 BSB Behavi ora 1 Sel f-Bl 副Te .34 。 12 .12 .12 66.15會 2.997 .17* .01 .30 1.996 2 臼B Characterological Self-Blaræ .41 .16 .16 .05 自 .49會 1.996 .34有 學 25 7.52* 1.996 育 p < .∞l

variable entered at that step, after controlling for the variance of the bl,囚k two vari~ ables entered in the previous step. Table 4 shows that helplessness uniquely accounted for 5% of the variance in depression, characterological self~blame also uniquely accounted for 5% of the varian個 in depression~~ both statistically increments, whereas behavioral self~blame was not a significant unique predictor of depression. Taken together

,

the three variables account for 16% of the variance in depression.. 264 • 教育心理學報

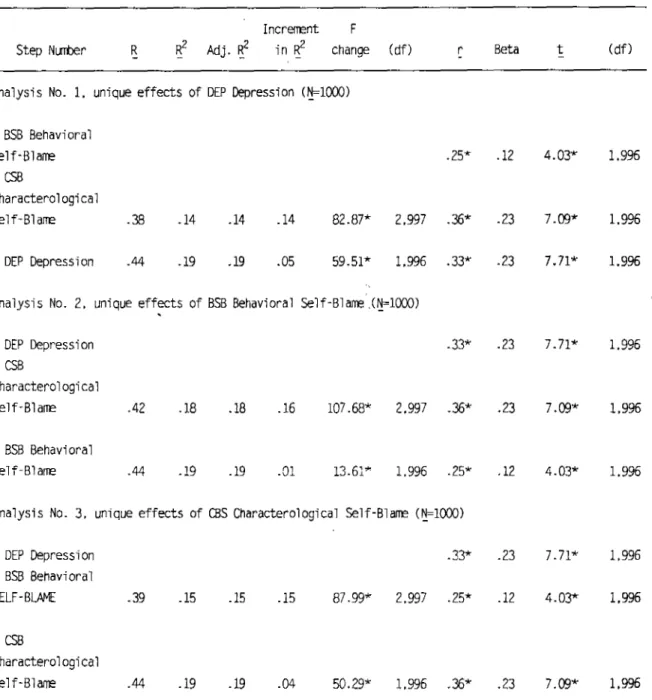

Table 5 Hierarchical Multiple Regression Predicting Helple盟ne盟 from Characterolo-gical Self-B1ame, Behavioral Self-Blame, and Depression

Increrænt F

Step N叩tJer R R2 Adj. ~2 in R2 change (df) 「 Beta t (df)

Ana1ysis No. 1. unique effects of DEP 峙「自sion (fi=1000) 1 BSB Behavioral Se1f-Blarre .25肯 .12 4.03會 1.996 已B Charactero1ogical Self-B1aπE .38 .14 .14 .14 82.87* 2.997 .36會 .23 7. 四會 1.996 2 DEP DepresSion .44 .19 .19 .05 59.51* 1.996 .33會 .23 7.71會 1.996

Analysis No. 2. unique effects of BSB Behavioral Self-Blarre , (~=1α氾)

1 DEP Depression .33* .23 7.71會 1.996 白自 Characterologica1 Self-B1aræ .42 .18 .18 .16 107.68* 2.997 ,苟安 .23 7. 的會 1.996 2 BSB Behaviora1 Self-B1aræ .44 .19 .19 .01 13.61 哄 1.996 .25會 .12 4.03* 1.996

的 a1ys;s No. 3. unique effects of 臼S Charactero1ogical Self-Bla肥(也=1帥)

1 DEP Depression .33會 .23 7.71曹 1.996 BSB Behavioral SELF-BLA陀 .39 .15 .15 .15 87.99會 2.997 .25會 .12 4.03有 1.996 2 臼8 Charactero1ogica1 Self-Slarre .44 .19 .19 .04 50.29* 1.由6 .36會 .23 7. 個# 1.四6 育12.

<

.∞1Results of the second set of hierarchical regression analyses used to predict help-lessness are' shown -in Table 5. 臼læ again, multiple analyses were performed to allow a different predictor to enter the equation in the final step. Table 5 shows that behav-ioral self-blame uniquely ac∞unted for 1 % of the variance in helplessne臣, charactero-logical se1f-blame 4% and depre品ion uniquely ao∞unted for 5% of the varian但 in

help-le血ness. Taken together the three predictors accounted for 19% of the variance in-help-lessness. The findings indicate that, although al1 three are statistically signifi臼nt

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTIONS IN DEPRESSION: INVESTIGATION OF ONE POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

265 •

predictors, characterological 盟lf-blame is much more useful than behavioral self-blame in predicting helplessness.

DISCUSSION

Research Hypotheses and Exploratory Questions

The first two hypothe盟s concerned the empirica1 existence of the paradox in the beliefs of depr扭扭d per四個﹒The first hypothesis provided a test for Beck's cognitive model of depre品ion. General 盟lf-blame exhibited- a statistically significant ∞甘elation

with dep扭扭ion,空= .17). Although statistical1y significant, this level of a臨巨iation is low in practi臼1 但rms, accounting for less than 3% of the variance in depre品ion. The盟 results provide 田me slight confirming evidence for Beck's (1967) cognitive model of depression which propo盟s self-blame as a prima可 f田t叮e of the depressed

per田n. The findings in the current study are consistent with tho扭扭ported by

Bordieri 血d Kilbury (1991), Laxer (1964), Tas目前(1982) , and W,田rner (1980) who found that self-blame was a自由iated with depression.

Additionally,自me studies reported that self唱blame was related to p∞r adjust-ment and was viewed as a maladaptive resp聞自 CAbrams & Finesing缸, 1953; Biener,

1983; 包rdieri , Comninel, & Drehmer, 1989; Heinemann, Bulka, & Smetak, 1988; Taylor, Lichtman, & W,∞d, 1984). However, although most p四ple think that 揖1f bla間 is psychologi臼11y 也maging, some researches claim 出at se}f-blame may be a

positive psychological 口leChanism and a自由iated with go吋 coping and better

adjust-ment in 田me situations involving acddents, serious illness, or trauma CBrewîn, 1982, 1985; Chodo宜, Friedman, & Hamburg, 1964; Janoff-Bulman & Lang-Gunn, 1988; Janoff-Bulman & Wortman, 1977; Kaze & Bu祉, 1988; Miller & Ross, 1975; Schulz & Deck前,

1985; Taylor et aI., 1984; Tennen, Affleck, Allen, McGrade, & Ra包an, 1984; Peter四n et 且, 1981; Timko

&

Janoff-Bulman, 1985; Wortman&

Dintzer, 1978).甘le second hypothesis provided a 悟到 for Seligman's learned helplessness model of dep把自ion. Helplessne串 exhibited a s個tisti臼lly significant p田itive correlation with

depression (r

=

.33). The result pro吋de ∞nfirming eviden自 for Seligman's (975)learned helpl自sness m吋el of depr晶sion which p叩開盟s that feeling of helplessness

can precipitate the development of depression. This result is ∞nsistent with findings

repor區d in pre吋叫s studies which supported the depression model of learned helpl自s

ness, showing that depressed individua1s perceive themselves as exercising little control over their environment CBauer, 1987; Klein & Seligman, 1976; Miller & Seligm缸, 1975: Oliver & Wi11iams

,

1979). However,

this finding of the current s• 266 • 教育心理學報

support in this study, namely, depressed per血ns tend to blame themselves for events over which they feel no controI. Participants who scored high on general self-blame showed higher levels of depression, and those who scored hîgh on helplessness 刮目

scored high on depression. However, the relationship between general self-blame and depression is weak. 甘1e obtainecl data tends to support the empirical existence of the paradox and suggests that depres阻d individuals may have a tendency

to

hold them-selves responsible for 盟emingly uncontrollable events. As Abramson and Sackeim (l977} pointed out,

there is logical incompatibility these beliefs. Nevertheless,

evidence for this paradox was obtained by this study. These findings are similar to other research which suggests that the paradox exists and is manifested empirically (四ro臼& SeIi g-man, 1975: Lester, 1989; Peterson, 1979). Additionally, some studies have found evidenæ of the existence of this paradox in nonc1inical undergraduate populations (Garber & Hollon,

1980) and in a child clinical population (Kerman,

1981).The next four hypo出自由 (from 2-a to 2•d) concerned the 扭曲lution for the para-dox suggested by Janoff-Bulman. Hypothe配s 2-a and 2-b pro吋ded a test for

Janoff-Bulman's 盟lf-blame 、nlOdel wi th regard to characterological 堅lf-bl缸醋.

Charaderolo-gical 盟lf-blame exhibited statisticalIy significant correlation with depression and help

、 lessness.

Thep時間1t resuIts demonstrated that characterologi回1 self-blame is apparently an important charaderistic of depression and helplessness

,

provicling partial confirming evidenæ for Janoff-Bulman's (1979) self-bl缸ne atiributions model of depression that proposes the characterological 記1f-bl目ne as a maladaptive response and associate with depression and helplessness, but 世havioral 盟lf-blame as an adaptive respbnse. This finding is consistent with the results reported in previous studies (Ander田n, Horowitz,

& French, 1983; Hindin, Zautra, & Reich, 1984; Manne & Sandler, 1984; Meyer & Taylor,

1986),

which showed characterological se1f-blame as a concomitant of depres-sion or helplessness. Specifically, Janoff-Bulman (1979) found that depressed femaleundergraduates reported more characterologi且l 盟lf-bl缸ne than did nondepressed

female undergraduates. Peterson et a1., (1981) survey'剖 undergraduates 叫th a re兩吋

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRffiUTlONS IN DEPRESSION: INVEST!GATION OF ONE POSSIBLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

267 •

self-blame had a weak association with depression and helplessne盟, Janoff也ulman's

hypothesis appears dis∞nfirmed with regard to behavioral 扭:lf-blarr靶 which is

propo盟d 扭曲 adaptive response and won't be associated with depression or

helpless-扭扭﹒The findings of this study are simi1ar to those reported by Carver et aL (1985) who found that both characterological self-blame and behavioral 盟lf- blame measured by Janoff-Bulman's (1979) measure of self-blame were positively correlatedwith depres-sion in a survey of undergraduates. However, these researchers also found a relatively low correlation (r

=

.19) between behavioral self-blame and depression.The findings of the eurrent study are similar to those which show a positive rela-tionship 世tw田n behavioral self-blame and depression or p∞r adjustment. For exam-ple, Meyer and Taylor (1986) reported that behavioral self-blame was 自由ciated with

p∞,r adjustment among rape victims. Results of the pre盟nt study are inconsistent with those reported by Affleck et al吋(1 987) , Cr∞g and Levine (1987), Janoff-Bulman

(1979, 1981, 1982), Peterson et al., (981), Tennen et al., (1984), Tennen, Affleck, &

Gers趾nan, (1986); and Timko and Janoff-Bulman (1985), who claimed that 加havioral

self-blame might be an adaptive respon盟 and ass血iated with 世tter coping. For exam-ple, Peter田n et 此, (1981) found that blame directed at their own behaviors correlated with lack of depressive symptoms. Tennen et aI., (1984) found that children who explained the onset of their disease in terms of their behavior were rated by their physicians as coping better with dia世tes than were children who explained the on世t m 扭rms of genetic inheritance. Janoff-Bulman (1982) found that 出havioral 盟lf-blame

by victims was associated with high self-esteem and perceptions of future avoidabi1ity

of the victimization. 1n addition, Timko and Janoff-Bulman (1985) found similar results among breast 臼.ncer patients. Women who believed. that they were 、behavioral1y respon-sible for their conditions were s配n as adjusting better than . were those who made characìerological self-blame attributions.

Considering all the results found in this study for the last fo叮 hypotheses, find-ings suppor阻d Janoff-bulman's model of self-blame regarding assumption a出ut charac-terological self-blame, but not regarding assumptions about behavioral 盟lf-blame. The current study found partial support

268

.

教育心理學報is adaptive preci盟ly for this r曲曲n.

Studies examining Janoff-Bulman's mode1 of two types of self-b1ame have been inconsis-tent. Some studies suppor胎dJanoff-Bu1man's (1979) differentiation between behaviora1 se1f-blame and characterological self-b1ame (FolleUe & Jacob田n, 1987; Janoff-Bulman

,

1979,

1982; Janoff-Bulman & Wortman,

1977; Peterson et a1.,

1981; Valdez,

1985) but 叩medid not (Carver et a1.,

1985; Frazier,

1990; Kaze & B叮t, 1988). Sp四ifically, Kaze and Burt (1988) surveyed rape victims, but didn't distinguish between behaviora1 blame and charactero1ogical self-blame. Meyer and Taylor (1986) did distinguish betw田n these two 甘pes of self-b1ame, but the two 句rpes of blame were not directIy 扭扭扭甜. Bordieri and Ki1bury (1991) examined thee討回t of different 句中esof self-b1ame attributions on per臼ivedrehabilitation outcomes

,

and the results suppor扭d Janoff-Bu1man's (979) differentiation of se1f-b1ame aUributions. The findings are diversified.Regarding the two exploratory research questions, results from hierarchical regres-sion analyses showed that helples叩ess and charadero1ogical 盟lf-blame were significant predictors of dep扭扭ion. Each unique1y predicted about 5% of the vari扭扭 in depres-sion. However

,

behaviora1 self-blame was not, a significant pr甜ictor and accounted for only a trivial amount of unique variance. In addition, depression and characterological self-blame were significant predictors of helplessness,

uniquely 由中laining 5% and 4% of the variance, respectively. Again, behavioral 盟:lf-b1ame ac∞unb吋 for only a triv-ial amount of unique varian田. The results demonstrated that characterologi回l 扭lfblame was a much stronger predîctor of the depression and he1p1essness than t的av

ioral self-b1ame, which only accounted for a trivial amount of unique variance. These findings are similar to those reported by Carver et a

1.

(1985)who found that only the effects attributable to charaderological self-b1ame, compared with behavioral self blame,

accounted unique1y for significant varian自 in depression and only characterolog-ical self-blame is a significant predictor in depression.Summary and Interpr它tation of Findings

Considering the findings of this study as a who1e, several important inferences can be drawn.

First, the resu1ts of the current study are mixed as to whether behaviöral self-b1ame and charac但rologica1 self-b1ame are different ∞ns廿uc缸, or in fad not different.

臼1 the one hand, the behavioral self-b1ame had a ve可 10wa自由iation wi出 dep自由ion

and was not significant predictor of depressio血, but the charaderologi回1 self-blame had a stronger correlation with dep甜甜on and was a significant predictor ofdepres-sion. Additionally, the two m且sured constructs were m吋era紐1y corre1ated in' this

study (r == .39). 四le 1ack of overlap indic~血色 the measure may a臨ess different

constructs. Further

,

behavioral 盟lf-blame had no co甘elation with avoida.n臣, butchar-acterological 盟lf-blame had a significant1y negatively a自由iation with avoidance. Thus, there is 宙間 evidenæ of construct validi句T. 臼1 the other hand, the va1idity check for

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRlBUTlONS IN DEPRESSION: INVESTlGATlON OF ONE POSSlBLE RESOLUTlON OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

• 269 •

correlations for this construct were not as exp回紐d. It is not po自ible to concIude on the basis of this study whether behavioral self-blame does, or does not exist in the sense - that undergraduate students think of themselves in this way. The lack of evidenæ in this study may be due to f1awed measurement techniques, or to 、 an ac臼al ab盟nce of the construct as p曲ple think about themselves.

Second

,

the findings in this study suggest that internal attributions for negativeoutcomes are ass∞iated with increased depression and helpless扭扭﹒ The results are

consistent with the findings of pre吋ous 扭扭arches (Kerm血, 1981; Kupier, 1978;

Sweeney et al., 1986). However, the exact roles that the internal and external attribu-tional dimension play in depression and its treatm叩t are uncertain CBanks & Goggin, 1983; Phares, Wilson, &阻yver, 1971).

Third

,

predictors in this study accol1nted for a relatively small amount of thevari-ance in depression. The predictors chosen for this study were 盟lected to test the

Janoff-Bulman's m吋el. It is po盟ible that a more complete 盟t of predictors would

"have a higher degree of relationship to depression. Findings of this study suggest

that dep扭扭ion is probably a complex phenomenon that is determined by a large

number of variables, rather than any single variable, or small set of variables.

Fourth, it was surprising to find that behavioral self-blame had a weak positive relationship with depression and helplessness. Why were the obtained results not consis-tent with those reported by Janoff-Bulman (1979) who found behavioral self-blame was an adaptive response? Why did participants in this study respond with numerically higher 口扭曲 ratings of behavioral 盟lf-blarne rneasure compared to characterological self-blame? The盟 questions are crucial,出cause a basic finding of this study d田s not agree with expectations based on the model this research attempted to examine. Consideration of the findings, and the results of debriefing interviews with 盟veral of the p叮ticipants in this re盟arch suggests nine possible explanations for this

discrep-血cy. Each is pre盟nted in the paragraphs below: (1) The discrepancy in findings is due

to

problems with the measurement of behavioral self-blarne. The Beha吋oral Self-Blame Subscale requires fairly abstract cau盟1 judgments. Perhaps the greatercomplex-ity 血d abs甘action of this concept and the greater difficulty of the judgments result in greater measurement er

• 270 教育心理學報

response in this way, because Chinese are relatively rule oriented and co吋ormist (Wi1田n, 1981) and, generally speaking, education is moralistical1y oriented. (3) It may be difficult for participants 臼 differentiate charaderological self-blame and behavioral self-blame. For ex缸nple, one participant asked whether "1缸y" is an asp配t of charac-ter or a behavior? Qui但 a few researchers (Abbey, 1987: Porter, 1983) have poin起d

out the ∞n臼ptual difficulty of distinguishing between behavioral self-blame and charac-terological self-blame. For example, if we consistently do 田me behaviors, then many

per田ns would view these behaviors as representing a trait. Behaviors with cross-situa-tional consistency and high stabili可 across time imply an asp配t of "character". While some behaviors are considered as unchanging, on the other hand 田me charader traits are viewed as changeable. For example, if one is considered reluctant

to

trust, thatper田n still may be 盟en of quite 個pable of learning

to

trust under the right circum-stances. Janoff-Bulman (1979) mentioned that may be behavioral self-blame reported by participants "∞-occu甘ed with characterological self-blame, and blaming 0間'sbehaviors was thus an extension of blaming one's character. It may be difficult

to

blame one's charac但r without blaming 0間's benavior, yet it may be very po自ible 臼

blame one's behavior without blaming one's charac但:r." (4) Participants might ∞nfuse

the ∞n自pts self-blame

,

causality,

and responsibility. When one t賠lieves s/he is the "cause" of a problem, it does not necessarily follow that this per田n will blame himself Iherse1f for it,

or assume responsibi1i可 (Shaver & Drown,

1986). The possibility of being an unwitting, a血idental cause of a problem al10ws oneto

escape blame. However,

daily e)中eri扭曲 shows that m叩y persans who accidentally cause a problem,

nevertheless 扭扭 responsibi1ity for attempting to repair the situation. (5) Related tomeasurement problems with behavioral 世lf-blame, perhaps the con扭quences of the

scenarios are not serious (negative) enough. Participants may not have felt a strongly negative reaction

to

the hypothetical situations, and tend吋 to mlDlmlze theconse-quences of the sc且nario. (6) Another way the seriousness of the scenario could have been minimized, was the hypothetical versus real nature of the situations presented. Mil1er, Klee, and Norman (1982) and Mi1ler and Porter (1983) pointed out that

HELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRffiUTIONS IN DEPRESSION; INVESTIGATION OF ONE • 271 POSSffiLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAlWAN

盟lf-blame. Although this may be true, it may al四 be very rare 叩d difficult for Taiwan students to a血。mplish. It is likely that many students who f,自1 behaviora1ly blameworthy will 刮目 f自1 some degree of charaderological self-blame. (8) It is possi-ble that J血off-Bulm缸's model only fits ærtain 句pes of subj缸站, such as victims, but not neces盟rily all depressed persons (Timlo & Janoff-Bulman, 1985). (9) FinaIly, there

is the possibili甘 that the construd of behavioral 盟lf-blame d田S not exist. The

construd has been questioned by prominent researchers CShaver & Drown, 1986). Nine

po品ible r扭曲ns that the findings of this study did not support the part of Janoff-BuIman's model which propo盟d "behavioral 盟lf-blame" as a construct distind from " charaderological 盟lf-blame." Many of these reasons are not mutually exclusive, and more re盟arch is needed to needed to dete口nine which one, or ones, explain the find-ings of this study.

Limitations of the Study

Many of the nine po自ible reasons discussed in the preceding section why J anoff-Bulman's model was not fully suppor但d by the findings of this study stem from

meth吋ologìca1 limitations described as below. (1) Threats to gereralizabi1ity: (a) The

阻mple of students was al1 from NTNU, who may not be representative of the typical college student. (b) Another important consideration relating

to

the generali且bili可 of findin直s is the degr扭扭 which the scenarios pre田nted to participants were r叩resen且tive of the gen由于al situations. (2) Measurement problems: (a) construd validity 叩d

low in但mal reliability of the measure, e甲ecially the Beha吋oral Self-BIame Subscale. (b) all measures were su甸回ti而且lf-repor臼. (3) Statistical problems : (a) 甘也 relation

ships between variables were examined with ∞πelation副 methods. This study could

not exami阻 the causal nature of t扭扭 relationships. 的 The large number of subjects provide a great amount of statistical power. Therefore correlations that. were rather trivial in 區rms of pr缸tical significance

,

were nevertheless statistically significant. In addition,

even though many more correlations achieved signifi臼n峙 "than would have世en exp田ted by chance,回me were probably statistical artif配ts. This "highlights the need

to

replicate the findings reported here 回吋er different conditions Ce.g., with differ-ent populations, different predic如凹, cri胎r站, etc.).Implications for Clinical Practice

Dweck (1975) noted that therapeutic attempts to alter attributions from charac胎ro

logical

to

世havior self-bl叩1e m叮 be c1ini個lly adaptive for 出e individual. Although the findings of this study did not pro吋de support for the adaptive function of behav-ioral self-blan靶, the importan且 these findings have for interventions designed to help出e depres盟d per田n is worth further discussion. Examination of a depr晶扭d individual

ba盟d on an understanding of paradoxi臼1 realities can heighten the therapist's appr田i

• 272 • 教育心理學報

The findings of this study supported the relationships among se1f-blame attributions, helplessness, and depression. Results suggest that therapy which emphasizes cognitive

restructuring, changing attributions, and providing the 盟n盟 of control for the

depres副 individual might be v叮 effective CKavan & Dowd, 1984; McMu11in, 1986; Valins & Nisbe仗, 1971).

Results of this study have suggested an association between characterological se 1f-blame and helple盟ness in depression. The împortance of cognition factors in depre自lon

is supported. Recognition of this import扭扭 has had therapeutic implications (Freeman, Pretzer, Fleming, & Simon, 1990; Teasdale, 1989). Results of this study suggest that Seligman's (1 975) ∞ntrol-oriented strategies may be appropria起 for depressed perso帥, who扭 self-blaming does not imply high per由l ived control. Thus, how to -provide c1ients with a sense of control and decrease the f自lings of helplessness becomes very

impor個nt. An intervention aimed at emphasizing personal control, building upon initial small successes and choiæs one has might be therapeutic with c1ients (Peter田n, 1982).

Further,區ck's (1967) cognitive model emphasizes cognitive restructuring of the depressed individua1.、 Further research is needed to advanæ knowledge about the rela-tionship among 配1f-blame attribution, helplessness and depression, and to apply this knowledge in order to increase the individual mental health.

Findings of this study suggest that attributions may influence adjustment, the implication for c1inical practice concerns the quality and content of therapist interven-tions

,

and in training therapists to be more sensitive to clients' internal attributions and se1f-blaming pattern, and realize how these impact c1ient functioning. Successful therapists may need to address hannful,

self"7blaming and destructive attitudes andbehaviors, and assist c1ients to develop a healthier s可le of attributions. Mor由ver, Janoft也ulman 血d Lang-Gunn (1988) not吋 that self-blame attributions may be more malleable and directly modifiable than per田nality or character, and may thus 世血

important preliminary step in helping c1ients to cope with the feelings of helple自ne臣,

Leading p臼'P1e not to f阻1S on their nonmodifiable character

,

may increase per田ivedfuture avoidabili句T of negative events and per臼ived ∞ntrol in general.甘1Ís is espe-cially impor阻nt for depressed clients who gener.

Suggestions for Future Research

One of the m閏t definitive statements that 臼n be made about the present study is that its findings rai盟 far more questions than are answered. Thus, there are lots of questions which could be explored further. Below are some suggestions for 扣扭扭

research.

回回LESSNESSAND SELF -BLA岫 ATTRmUTJONSIN DEPRESSION: 的VESTIGATIONOF ONE POssmLE RESOLUTION OF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS 的 TAIWAN

• 273 •

The first suggestions for future research are based dirl配tIy on the limitations of this study. Results need to be extended to other samples to improve gen~rali血bility.

Further testing of measurement methods for self-blame, especially behavio~al self-blame, are needed.

More re盟arch is n田ded to e)中lore and test Janoff-Bulman's m吋el. Future stud-ies could ex缸nine the effect of different types of 盟lf-blame attrîbutions on adjustment to various forms of victîmîzation.

Central to Janoff-Bulman's model is the distinction betw田n characterological 盟lf

blame and behavioral se1f咱 blame. This study did not support such a distinction for college students in Taiwan. More research is needed, especial1y to examine what

combinations of characterological 叩d behavioral 哩]f-blame might be ~st adaptive.

Recal1 that Janoff-Bulman (1979) pointed out that behavioral self-blame is adaptive only in the relative absence of characterological self-blame. This proposition needs further testing. Such studies wil1 face the challenge of devising instruments which can measure the difference in t扭扭句rpes of self-blame, if differences exist. Further research is needed to es包blish the relation of both types of self-blame to depre品ion

and helplessness in different populations 揖lec阻d on the basis of age, educational level, gender, ar.d ethnîci甘.

An further research, and experimental study could 世 conduc紐d on a non-clinical

poppulation or a clinical population at胎mpting 臼 teach su甸回ts how to distinguish

k御自n characterological 扭]f-blame and 出havioral self-blame. The experimen個l

gioup would then be fol1owed up to determine if their level of coping had improved. Crîteria to measure improvement would not only include self-report instruments but

剖田 consist of a significant others' rating and behavior index.

Characterological 扭lf-blame is an interesting target for research in itself.

Charac-胎。logi也1 self-blame has only recently been investigated as a correlate of depression, and results from this study suggest that characterological self-blame was as potent a predîctor of depression as helple自ness﹒ Future study mîght wel1 address thîs 品ue.

Carver et aI., (1985) found that the tendency 臼 generali揖 from a single fai1ure to a

broader 扭n自 of per田nal inadequacy, which is similar to characterological self-blan時,

is an impor阻nt part of the phenomenology of depressîon. The relationship between charaderological self -b

• 274 • 教育心理學報

terological self-b1ame have not been re1ated to the attributiona1 dimensions of intema1-ity. stabiIity. globality (Abramson et a1.. 1978), and controllabili可(Janoff -Bulman, 1979). Making the阻 links would help to c1arify the meaning of the two 句rpes of 揖lf

blame. 'Of cour妞. more study is need 扭扭扭扭 how the cognitive proces盟s of

depressed per自由 differ from th。但 of nondepressed persons (Coyne, Aldwin, &

』且rus, 1981; 臼'yne & Got1ib, 1983: Got1ib & Beatty, 1985).

The results of the present study are ∞rrelational 血d provide little information about cau血1 relationships. The世 resu1ts c1ear1y establish the need for studies which can es區.blish 且usal relationships and al田 leave 叩en the possibility 出at there are cognitive pr自ur田,rs of depression (l..ewin田hn, Steinmetz. Larson, & Frar甚至lin, 1980. Additionally. further re盟arch is needed

to

identify more preci盟1y what factors may possib1y predi中ose a per田n to develop depression (Bre吋n, 1985; J anoft也lulman .&Hecker, 1988). Therefore. other variables thought

to

be significant risk fadors for depression al田 should be inc1uded in fu個re studies, such as tota1 life stress,且tisfaction with s回ial supports, negative life events, etc. (Cochran & Hammen, 1985; Hammen & Cochra

n..

1981; Hammen, Krantz, & C田hran, 1981; Hammen & Mayol, 1982; Robins & Block, 1989; Smurthwaite, 1989; Sowards, 1986). Finally, more research is needed to examine 扭曲1utions of the paradox in depression. Lester (1989) pointed out that patients with both ∞mponent symptoms of the paradox may be ,especially1ikely 臼 contemplate suicide and see suicide as the on1y r自pon盟 in the life situation

in which they feel t的出 blameworthy and powerless. Mor田ver, Abramson and Sackeim

(1977) mentioned that the paradox is functional in that perhaps self-blame and

helpless-扭扭 be1iefs tend to 1essen the seriousness of one-another. This issue is worth further empirical investigation. In addition

,

is the paradox,

a sp四ific feature of depressiC?n ora general phenomenon, highlighted in depressive m仗xl s且tes? Abr缸n個n and Sackeim

(1977) pointed out some research suggests normal individuals may have the

phenomenon of the p訂adox but it is not as compe1ling as it is in the case of

depres-sion. Thus, the generali句r of the paradox 叩d 扭扭扭nt is an issue for future

扭扭arch. Mor凹ver. there is litt1e research to test any of the p田sible re田lutions of the p訂adox pre扭nted by Abramson and Sackeim (1977), and Lester (1989).

CONCLUSION

甘le pu中ose of this study was

to

investigate the paradox of the helplessness and self-blame in depression by examining Janoff-Bulman's model of self-self-blame attributions for depression which distinguishes betw回n "behavioral se1f-b1ame" and "charaderological self-blame". In the present study, college students in Taiwan were administered three Chine睦 versions of instruments-the Beck Depression Inventory which measures depression,

the Attri-butional S可le Questionnaire which measures helplessness, and the Self-Blame Scale whichrr世asures general self-blame, characterological self• blame and behavioral self-blame. of 1443 students who retumed surveys

,

a stratified sample of 1000 participants was analyzed. Six 扭曲arches hypotheses were derived from lanoff-Bulman's model and were examinedHELPLESSNESS AND SELF-BLAME ATTRIBUTIONS IN DEPRESSION: 的VESTIGATIONOF ONE PûSSIBLE RE叩LUTIONOF THIS PARADOX AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS IN TAIWAN

• 275 •

through use of Pearson product-moment coπelation 叩aly:盟sand multiple-regr自sion

血aly-ses.

Correlational eviden田 support four of the six hypothe盟s. The first two

hypothe-扭S ∞ncerned 出e empiri田1 existence of the paradox ìn the 出liefs of d叩ressed per自由﹒ The first hypothesis provided a 扭st for 區ck's cognitive model of depression.

General 且lf-blame exhibi胎d a statistically significant correlation with 也pression, but this level of association is low in practical terms

,

accounting for 1自s than 3% of the variance . in depression, The finding provides slight confirming evidence for B缸k's (1967) cognitive model of depre自ion which postulates that self-blaJ祖 is a significant maladaptive characteristic of depressed per田間﹒ The. second hypoth臼is pro吋ded a test for Seligman's learned helplessness m吋el of depr自sion. Helple盟n自s exhibit出 asignif-i回nt positive relationship with depression. This finding provided support for Se

lig-man's learned helple品ness model of. depre自ion that views depres揖d individuals as

perceiving themselves as exercising little ∞ntrol over their environment. Taken together these results supported the empi討回1 existence of the paradox in which

depres盟d per田間 f自1 helple扭曲d 盟lf-blame about the same event.

The next fo叮 hypothe盟s concerned a re抽lution for the paradox suggested by

Janoff-Bu1man. As predicted by Janoff-Bulm缸's (1979) model, characterological

self-bla口時 e油ibited a statistically significant correlation with depression and helple自n臼s.

The pre盟nt results- suggested that characterological self-blame is apparently an

impor-崗位 characteristic of depression and helple品ness, providing confirming eviden田 for

Janoff-Bulman's self-blame atlributions m囚:lel of depression with regard to charac阻[0-logical 自lf-blame. This m吋el proposes characterological 扭lf-blame as a maladaptive

response 晶晶ciated with depression and helple品自由.

The last two hypotheses

,

provided a 扭st for Janoff-Bulman's self-blame modelwith regard 胎 behavioral 盟lf-blame. Behavioral 盟lf-bl由ne 自由ibit吋 a weak but

statisticaIly significant correlation with depression. Although statisticalIy significant, this level of a目前iation is low in practi也1 terms