台灣僧尼的親屬支持系統 : 以南部某寺院為中心 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) ABSTRACT Unlike what most people believe, Buddhist monasteries rely not only on laymen’s financial support but also on the supports of families and relatives of monks and nuns. In addition, Buddhist renunciation does not always cut off the relationship of a monk or nun with their families. On the contrary, most of monks and nuns in my research remain close contacts with their families and relatives. It is believed that once a person joins the Order, he or she can rely fully on the monasteries’ financial, emotional and medical supports. However, this is not true in all Buddhist monasteries in Taiwan. Mutual dependency between monks or nuns and their families and relatives is the main focus of this research. With lack of supports of different aspects from the monasteries, monks and nuns will have to turn to their families and relatives for helps when needed. Therefore, keeping close and positive relationship with families and relatives is important to some monks and nuns.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. This research aims at: 1. finding out the kin relationships of monks and nuns; 2. looking at the mutual dependency between monks and nuns and their families or relatives; 3. comparing the ideology and reality of monastic life and Buddhist institution (monasteries). In order to achieve the above goals, I will look at possible. Nat. y. sit. n. al. er. io. causes that might affect the relationship between monks and nuns with their families and relatives. Moreover, although not intended, the reasons of renunciation will be discussed in this paper. Different from Buddhist monasteries in other countries and traditions, Taiwanese monasteries can be privately owned by monks, nuns, or laymen. Because of this fact, and because it determines whether monks and nuns will get necessary supports from the monasteries or not, so types of Buddhist monasteries in Taiwan will be discussed, too.. Ch. engchi. ii. i n U. v.

(3) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. First, I want to thank my parents. Without their helps, I would never even have the chance to get into the graduate program. Although they did not really understand what my study was about, they still gave me their greatest supports. Also to my siblings, I have my gratitude for their encouragement while I was writing my master thesis. To my thesis advisor, Dr. Hsun Chang, and oral exam committee members, Dr. Meei-Hwa Chern and Dr. Hwei-Syin Lu, I thank them for their professional helps. Dr. Chang helped me to find an interesting research topic that I really believed worth of doing it. All three of them also provided me with several useful references that led me to the right research direction. They have always been busy, so I thank for their patience in reading and correcting my thesis paper.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Lastly, I have my sincere gratefulness to all my informants and research subjects. I really thank those venerable bhikshu and bhikshuni for their willingness to share their life stories with me. Without their helps and generosity to spare time for me, I. Nat. y. sit. n. al. er. io. would never be able to finish this research. Moreover, during my stay at Tainan doing interviews, Ms. Chun-Xiu Wu was kind enough to provide me with room and food in her house. Thank you all for your kind helps!. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................... iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF DIAGRAMS…………………………………………………………………………………………………..VI Chapter One: Introduction ............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Research Motivation and Background ............................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose of the Study........................................................................................ 2 1.3 Reviews on Literatures and Related Studies .................................................... 4 1.4 Research Methodologies ............................................................................... 12 1.5 Chapter Layout ............................................................................................... 14 1.6 Transliteration ................................................................................................ 17 Chapter Two: About C.F.S. ............................................................................................ 18 2.1 The Founder ................................................................................................... 19 2.2 Lineage ........................................................................................................... 22 2.3 The Abbot ....................................................................................................... 23 2.4 The People of C.F.S. ........................................................................................ 27 2.5 Background of the Monastic Members ......................................................... 34 2.6 Daily Life in the Monastery ............................................................................ 39. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 2.7 Cares for the Sangha ...................................................................................... 44 2.8 C.F.S.’ Code of Conduct .................................................................................. 48 2.9 Monastic Economy ......................................................................................... 51 Chapter Three: Different Perspectives on Kin Relations of Monks and Nuns ............. 56 3.1 Social Perspectives on Extrafamilial Alternative: ........................................... 56 3.2 What might affect kin relations of monks and nuns? .................................... 61 3.3 Kin Relations of Nuns in Fan Tsung’s research ............................................... 67 3.4 Substitutions of Family and Kin in the Monastery ......................................... 68 3.5 Why need helps? ............................................................................................ 71. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 3.6 Social Changes................................................................................................ 73 3.7 Filial Piety ....................................................................................................... 76 3.8 Gender, Birth Order and Marital Status ......................................................... 89 3.9 Monastic Rules and Prohibitions on kin relations of Monks and Nuns ......... 93 Chapter Four: Kin Relations of Monks and Nuns in Real Cases ................................... 96 4.1 Nuns Who Have No Marriage Before ............................................................. 97 4.2 Monk Who Have No Marriage Before.......................................................... 112 4.3 Monks Who Had Marriage Before ............................................................... 116 iv.

(5) 4.4 Other Cases .................................................................................................. 127 4.5 Reasons to Support ...................................................................................... 135 4.6 From Secular Family to Monastic Family ..................................................... 137 4.7 The Supports to Families from Monks and Nuns ......................................... 139 4.8 Types of Monastery...................................................................................... 140 Chapter Five: What About now? ................................................................................ 147 5.1 The Changing Monastic System in Taiwan ................................................... 147 5.2 The Changing Kin Relations of Monks and Nuns ......................................... 151 5.3 Systemization: Caring for Monks and Nuns in Taiwanese Monasteries ...... 155 5.4 Further Research .......................................................................................... 159 Chapter Six: Summary and Conclusion ...................................................................... 161 REFERENCES CITED..................................................................................................... 167. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

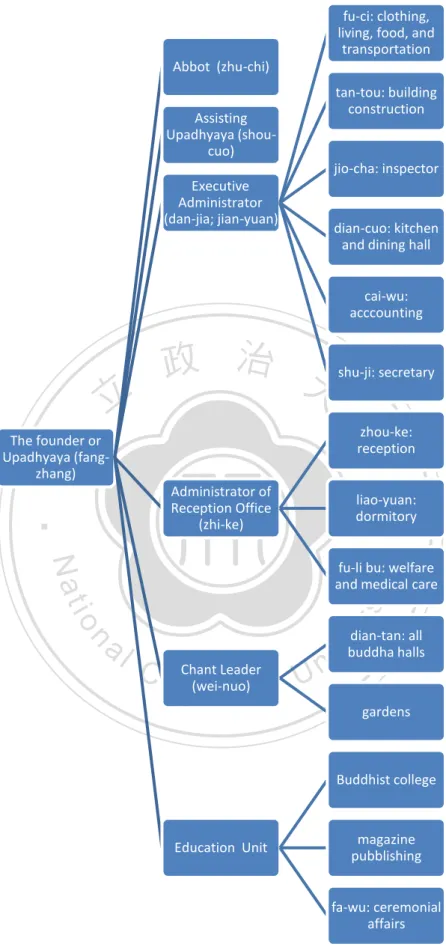

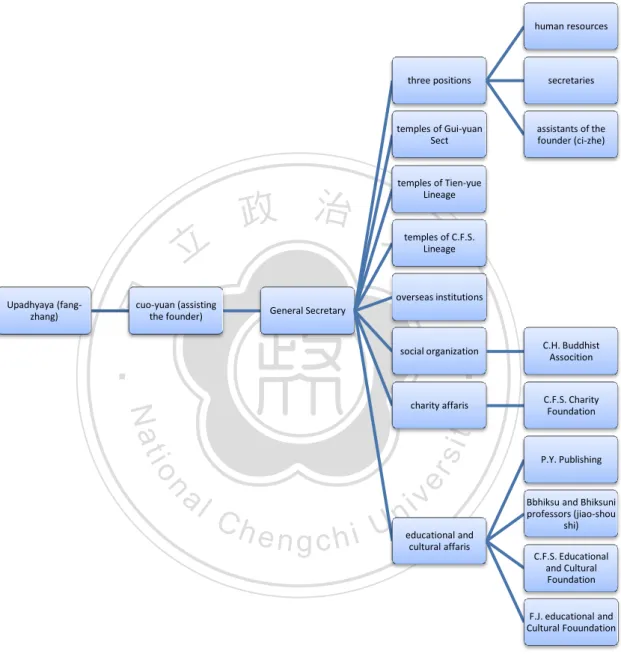

(6) LIST OF DIAGRAMS. PAGES. Diagram 1: C.F.S. management structure at the monastic level ......................... 165 Diagram 2: C.F.S. management structure at the organizational level ........................ 166. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(7) Chapter One: Introduction 1.1 Research Motivation and Background Sherry B. Ortner mentioned in her book that a monastery not only relied on its’ own income and lay supporters’ donations but also the supports from family members of those monks.. 1. According to Ortner, by sending children to the. monastery, a family could solve their problem of property division because each of the children could get more property when less of them were in line of inheritance.. 政 治 大 paying the living costs for their son in the monastery. It was a custom in Sherpas 立. When a family sends a son to the monastery, then the family became responsible for. monasteries that families and relatives were also responsible for the living expenses. ‧ 國. 學. of their relatives in the monasteries. Unlike Sherpas monastic system, monasteries in. ‧. Chinese monastic system provide food and room for their monastic members as the. sit. y. Nat. basic welfares for them. In Chinese monastic system, whether a monk’s relative is. io. er. willing to support the monastery depends on several factors because Chinese and Sherpas societies are quite different in many aspects. Furthermore, Ortner did not. al. n. v i n Cresearch, mention much about nuns in her not sure whether a nun got h e n gsocwehwere i U. the same financial helps from their relatives like those monks or not. In my research about the kin relations of monks and nuns, I will discuss more about the supports from lay families to nuns. Different from what most of people think about monastic life, most of monks and nuns maintain close relationships with their relatives after entering monasteries, and the mutual dependency between the monastery and lay supporters can also be found between monks or nuns and their relatives. Such a relationship of mutual dependency has always been existed, but most people focus only on the dependent 1. Sherry B. Ortner: Sherpas through their rituals, 1978. 1.

(8) relationship between the monastery and lay supporters. According to Buddhist philosophies, renunciation brings great merits to families of monks and nuns, and in addition to that, making offerings to monks and nuns generates merits for the lay supporters, too. By taking supports from lay supporters, monks and nuns have the obligations of generating merits for them in return. Therefore, not only sending children to the monasteries can help solving family problems but also generating merits for the family at the same time. Ortner’s study was among Sherpas group in the mountain areas of Nepal where. 政 治 大 Tibetan Buddhism, most of them focus more on the religious perspective. By using 立 these people practiced Tibetan Buddhism. Although there are many studies on. Ortner’s work as the starting resource of this thesis, my focus is on the kin relations. ‧ 國. 學. of monks and nuns after joining the Order in Taiwanese monasteries where two. ‧. societies have many differences in social ethics, values, religions, and so on. I will also. sit. y. Nat. look into the mutual dependency between relatives and these monks and nuns in. io. er. Taiwanese monasteries. There are a great number of monks and nuns rely fully or partly on their family’s supports at different levels despite whether they reside in the. al. n. v i n C hmonks and nuns U monasteries or not. In return, many have ever given helps to their engchi relatives during their monastic lives. Ideally, a Chinese monastic system should. provide good welfares to take care of its monastic members, but ideology is always different from the reality in one way or another.. 1.2 Purpose of the Study As mentioned above, the relatives of monks and nuns play an important role in supporting monastic institutions indirectly. Unlike ideal Chinese monastic system, monasteries in Sherpas society do not provide four types of supports to their 2.

(9) monastic members.2 Theoretically, a monastery should provide these four types of supports to their sangha members, but indeed, most of the Chinese Buddhist monasteries only provide partial supports of these four. Therefore, financial supports from relatives are important for monks and nuns to maintain their monastic lives. In Fan Tsung’s study, most of nuns in her research actually suffered from material deficiency and the feeling of insecurity about being old and sick.3 Most of the monasteries in Taiwan give allowances to their monastic members every month, but the amount of money might not be able to cover all necessary. 政 治 大 research results, medical expense is the greatest concern of monks and nuns who are 立 expenses especially when these monks and nuns have medical needs. From my field. in need. There were cases that sick or old monks and nuns had been requested by. ‧ 國. 學. the monastery to leave. In other cases, relatives of monks and nuns have to take over. ‧. the responsibility of taking care the sick monk or nun for the monastery instead. Such. y. sit. io. er. members.. Nat. an incident reflects poor medical care of Taiwanese monasteries to their monastic. The kin relations of monks and nuns can be quite different from the majority’s. al. n. v i n Cthat expectation. Most people believe requires one to cut off all secular h erenunciation ngchi U ties including relationship with families. In reality, most of monks and nuns still keep close relation with their families after entering the monasteries. In most of time, relatives of monks and nuns provide greater security for them than religious institutions. Although Buddhist philosophies encourage people to detach from all attachments, maintaining relationships with relatives is allowed within Buddhist monastic system.4 People’s stereotypical concepts about monastic life would affect. 2. Four Types of Support (si shi gong yang 四事供養): Food, clothing, bedding, and medicine (These are what a monk or a nun would need for their basic living.) 3 Fan Tsung, Moms, Nuns and Hookers: Extrafimiliar Alternatives for Village Women in Taiwan, 1986. 4 Tambiah, 1970, pp.67. 3.

(10) the kin relations of monks and nuns. Monks and nuns who chose to cut off all secular ties, like their motivations of becoming monks and nuns, were mostly not for religious reasons. Furthermore, keeping a positive and close relationship with relatives can be vital for monks and nuns because most of their monastic lives must rely on the supports of their relatives. The support might not be financial, but when one wants to join the Order, other relatives in the families have to share their lay responsibility to their natal or married families. Thus, monks and nuns who have the permissions from their families to join the Order will have less family burdens. 政 治 大 In order to find out real facts about Chinese monastic system in Taiwan and kin 立. afterward than those whose family is against to the decision.. relations of monks and nuns, there are three research focuses in my thesis:. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 1. To find out the kin relations of monks and nuns;. y. sit. io. er. relatives;. Nat. 2. To look at the mutual dependency between monks or nuns and their. 3. To compare the ideology and the reality of monastic life and religious. al. n. v i n institutions. What typesC of supports should the h e n g c h i Umonastery provide to their monastic members (the ideal perfect monastic system)? Does this ideal system being carried out within the monasteries in Taiwan?. 1.3 Reviews on Literatures and Related Studies There is not much study focuses on the relationship between monks and nuns and their families. One PhD thesis that had a section in discussing kinship relationship of was a research done by Fang Tsung in the early seventies of Taiwanese society. Most of the studies on Buddhism in Taiwan or other traditions focus more on the theoretical and philosophical perspectives. Many published biographies of monks 4.

(11) and nuns do not talk about their relationship with families much into details. One can find studies on the relationship between the monastery and their laymen, politics, society, or a social structure as a whole, but only a few of them ever mentions about the importance of monks’ and nuns’ families. The following books and articles are most helpful to my research topics. Although not all of them have direct relationship with the topic that I have been doing, they are great religious historical background books that I can use. There are four types of resources that have been used in this particular study:. 1.. 政 治 大 Anthropological studies on Buddhism; 立. 2. Historical or archival studies on Buddhism;. 4. Other related materials.. Nat. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 3. Buddhist texts;. io. a. Anthropological studies on Buddhism. al. er. The followings are primary materials that I have used in my thesis:. n. v i n In the first type of resource,C Sherry B. Ortner was U h e n g c h i one of the scholars who did her. studies among Sherpas from an anthropological perspective in the early years. Her first study on Sherpas was between September 1966 and February 1968.5 In her. study, she pointed out that the Sherpas family had a tradition of sending at least one child to the monastery when necessary so that each of his/her other kids could get more inheritance from them. Due to this reason, the family of those monks who had been sent to the monasteries had the responsibility to support their kid’s living expenses at the monastery. In another word, the monastery did not have the full financial responsibility in supporting its members. This finding brings us to a reality 5. Sherry B. Ortner: Sherpas through their rituals, 1978. 5.

(12) that a monastic community does not rely only on their own income and laymen’s support but also on the families of those monks and nuns. In supporting the monastic community, not only these people gain merits but also resolving the problem of division of inheritance. In Ortner’s second book on Sherpas, she tried to answer the following questions; first, why at the very first, did those Sherpas found their monasteries?; second, how did various structural and historical forces come in actions by a particular person at a particular time?; lastly, how were the abstract dynamics of structure and history. 政 治 大 the interactions between the internal and external forces of Sherpas society, and 立. transformed into human activity with intentions.6 In this book, she tried to analyze. how these forces push them to change their cultural schemas and to find a solution.. ‧ 國. 學. Another anthropologist who did a detailed research on Baan Phraan Muan village. ‧. of Northeast Thailand was S. J. Tambiah.7 In this particular study, he noted that it. sit. y. Nat. was legitimized of a monk to assist their parents when they were in need of material. io. er. help or when they were ill. Even though his monkhood and his secluded life suggested his departure and separation from his family, but it was not wrong to have. al. n. v i n C The close relations with their parents. pointed out the fact that a monk was h ebook ngchi U allowed to maintain close relations with his parents when needed.. Shiu-kuen Fan Tsung did a research on women who were outside of the normative family system, particularly Buddhist nuns and professional prostitutes in Taiwan. Her fieldworks had been taken place in a Hakka village between the summers of 1973 and 1974. Fan Tsung’s PhD thesis was later published in 1986 with her thesis topic, Moms, Nuns and Hookers: Extrafamilial Alternatives for Village Women in Taiwan. She tried to find out the reasons for woman’s choice to stay 6 7. Sherry B. Ortner: High Religion, 1989. S. J. Tambiah: Buddhism and The Spirit Cults In North-East Thailand, 1970. 6.

(13) outside of the normal family system. In Fan Tsung’s discussion about nuns in this Hakka village, she did look at nuns’ kinship relations, and that was very close to what I wanted to find out when I did my own deep interviews with the informants. In Welch’s The Practice of Chinese Buddhism 1900-1950, he provided the readers a clear picture about Buddhist monastic system and Buddhist practice in China.8 In this book, I was able to find out some influences of the Chinese monastic system on Taiwanese monastic system, especially when I focused my study on a monastery which its founder was from China after 1949. Welch mentioned in the book that he. 政 治 大 practice, and these differences were also found by me when studying Taiwanese 立 found many differences between ideal and reality, past and present, theory and. Buddhism in practice, too. The book could be divided into two parts: the monastic. ‧ 國. 學. system and the individual Buddhist. In the first part, Welch gave detailed descriptions. sit. y. Nat. different aspects would be taken cared in a personal level.. ‧. on monastic institutions, a picture from an institutional level; for the second part,. io. er. An anthropological material that had been used in my study was Stephen F. Teiser’s The Ghost Festival in Medieval China. Part of the study focused on the. al. n. v i n C son relationship between mother and of the death of the mother. Certain U h eatntheg time i h c ceremonies should be held by the son after the death of his mother in order to save the mother from bad rebirth. As most of other similar works, they drew their attention mostly on the relationship between mother and son only. This was also the case in Alan Cole’s works. Both focused on the kin relation between mother and son especially after the death of the mother. I have also used a few books of anthropological studies on Chinese kinship system. Two of them are very useful in helping me to understand about family in Chinese society. In Baker’s Chinese Family and Kinship, he focused his study on pre-twentieth 8. Holmes Welch: The Practice of Chinese Buddhism 1900-1950, 1967. 7.

(14) century’s China, and his field research was mainly done in rural China.9 There were two primary discussions about Chinese kinship system in his book: lineage and ancestor worship. Both topics were also important when we talked about pseudo-family structure within the Chinese monastic system. Another anthropological study on Chinese kinship is Paul Chao’s Chinese Kinship (1983) . Chaos’ work was mainly based on historical documents not field work. He tried to find out the relationship between ancestral worship and filial piety in Chinese family system. In addition to that, he wanted to tackle problems like the lineage, clan,. 政 治 大 filial piety, and other aspects about social life in China that had not been discussed 立. village, organization, the concept of the soul, the social importance of ancestor cults,. much before.. ‧ 國. 學. In Li’s “The Mother-Daughter Complex: Gender Identity and Subjectivity of. ‧. Taiwanese Buddhist Nuns”, she discussed different conceptions and expectations of. y. Nat. Buddhist nunhood between parents and the younger generations of nuns whose. er. io. sit. educational level were higher than before.10 At the same time, what were their conflicts with their mothers due to the difference between their educational levels?. al. n. v i n Li also talked about the functionCof the conflict between h e n g c h i U mothers and daughters in a. changing patriarchal society. Lastly, she explored the transmission of gender identity between mothers and daughters within the last fifty years from both psychological and cultural perspectives. Another article of Li, “Buddhist Women and Women’s Buddhism – the Gender Studies in Buddhism in these two decades (2002)”, she provided several Chinese and English research works on the study of Buddhist women. It was in her article that I found several useful second hand resources related to my topic. 9. Hugh D. R. Baker: Chinese Family and Kinship, 1979. Yu Chen Li: “Mother-Daughter Complex: Gender Identity and Subjectivity of Taiwanese Buddhist Nuns”, 2002. 8 10.

(15) b. Historical or archival studies on Buddhism In this category, Alan Cole’s two works studied the relationship between mother and son, and paternal relationships by finding out clues from those Buddhist texts of the Mahayana tradition.11 His research method was mainly archival. However, his topic of research could also be grouped into the first type of my resources. He noted that the family values served as an effective connection between the monasteries and the private families, and behind that, it was this mutual dependency between these two institutions.12 I focus my study also on the mutual dependency of these. 政 治 大 monks and nuns and their families, but Coles’ emphasis was between mothers and 立. two institutions, but it is different in the subjects of this dependency. My focus is on. sons but not necessary monks. Such a mutual dependency mentioned in Cole’s work. ‧ 國. 學. was only one of the results but not the original purpose of the compositions of these. ‧. texts.. sit. y. Nat. A sub-category was those works about Buddhist histories in Taiwan. Charles B.. io. er. Jones’ Buddhism in Taiwan (1999) divided history of Buddhism in Taiwan into three periods: the Ming and Qing Dynasty from 1660-1895, the Japanese colonial period. al. n. v i n C h to the modern U from 1895-1945, and the retrocession period from 1945 to 1990. He engchi provided valuable biographies on many Buddhist leaders in his later part of discussion. A similar work from the above was written in Chinese by Canteng Jiang on the Buddhist history of Taiwan from 1662 to 2008.13 He divided his book into three periods: from Ming Zheng period to the end of Qing Dynasty (1662-1894), the Buddhist history of Taiwan during Japanese colonial period (1895-1945), and from 11. Alan Cole: Mothers and Sons in Chinese Buddhism, 1998 and Text as Father : Paternal Seduction in Early Mahayana Buddhist Literature, 2005. 12 Family value, in here, was the obligation to hold Buddhist ceremonies by the son after the death of his mothers in order to save the mother from bad rebirth. This was an act to show his filial piety. 13 Canteng Jiang: Taiwan Fojiao Shi (臺灣佛教史-The History of Buddhism in Taiwan), 2009. 9.

(16) retrocession to modern period (1945-2008). Jiang’s book had great materials collections where one could get much historical information from his work. Both Jiang’s and Jone’s books provided good historical background of Taiwanese Buddhism, and these historical facts were important because Taiwanese monastic system had been influenced greatly by both monks that were from mainland China after 1949, and Japanese Buddhist monastic systems. Therefore, both works were helpful in providing background information on the historical developments of Buddhism in Taiwan.. 政 治 大 looked through most of his works in trying to find out the real monastic life in the 立 Gregory Schopen was a Pali scholar, and he did many Pali textual studies. I. Buddha’s time, and the possible traces of Buddhist teaching about the proper. ‧ 國. 學. relationship between monks and nuns with either their relatives or laymen. One of. ‧. his articles, “Filial Piety and the Monk in the Practice of Indian Buddhism: A Question. sit. y. Nat. of Sinicization (1984)”, dealt with the question whether the ideology or virtue of filial. io. er. piety had long existed since the early Buddhism, or it was brought up to Buddhism by the influence of Chinese family ethics after the it spread to China. Schopen used Pali. al. n. v i n evidences to prove that monks C and nuns dedicated the h e n g c h i Umerits to both live and. deceased parents as an act of filial piety. His other works also dealt with Buddhism in practice in the early Buddhist history, so these works gave us pictures about what were theories and what were the realities in early monastic lives.. c. Buddhist texts The third type of resources used in this thesis is Buddhist texts and any type of Buddhist literatures. These include Buddhist sutras, the vinaya (Ex. Dharmaguptaka vinaya), or Buddhist canons mainly of the Mahayana tradition. The purpose of using these materials is to find out what is the proper relation (according to Buddha’s 10.

(17) teachings) a monk or a nun should maintain with their lay family members. For example, in the Dharmaguptaka vinaya, the bhikshuni precepts indicated that it was improper to accept donations (Ex. cloth) from an unrelated householder.14 For what reason accepting donations from a related householder is not against the vinaya is what should be looked into. From the information of this type of resources, I found what was ideal in the Buddhist monastic system in order to compare them from what was real in Taiwanese monastic system. Moreover, a few books were studies on Buddhist monastic disciplines such as Shih Neng Rong’s An Investigation on the. 政 治 大 the Present Sangha Order (2003), these works helped us to understand what was 立. Vinaya's Monastic Discipline, Chinese Monastic Regulations, and their Significance in. ideal monastic system, and matters on daily monastic lives.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. d. Other related materials. sit. y. Nat. The last category includes all secondary materials such as related theses, papers,. io. er. articles, biographies of monks and nuns, online resources, and C.F.S.’ publications. In Hillary Crane (2007), “Becoming a nun, becoming a man: Taiwanese Buddhist nuns’. al. n. v i n Ch gender transformation”, her conversations with nuns at Zhi Guang Monastery engchi U. showed the close relations between nuns and their families (the families established by marriage).15 Some of these nuns had a hard time leaving their family burden behind. Although her article was on gender issue, it provided great first hand information that were close related to the topic of this thesis.. M.A. or Ph.D. thesis Many thesis papers that I had used were about the interactions between 14. 15. Karma Lekshe Tsomo: Sisters in Solitdue: Two Traditions of Buddhist Monastic Ethics for Women: pp.37, 1996. Hillary Crane’s article was published by Religion periodical: pp.117-132 (2007). 11.

(18) Buddhist ethics and the ethics of traditional Chinese society. These focus on the relations between mother and son (similar to Alan Cole’s study) or between parents and children (the issue of filial piety). Therefore, these theses became great resources in dealing with issues on the conflicts between social norms or ethics and the choice of entering the monastery.. Biographies Lastly, biographies of monks and nuns provide some background information of. 政 治 大 mostly not in details, talked about their families, or mentioned their relationships 立 why they chose to become monks or nuns as their life career. They sometimes,. with their families after becoming monks and nuns.. sit. y. Nat. Deep Interview. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 1.4 Research Methodologies. io. er. My research focuses on one monastic institution which I called it C.F.S. This code name is the abbreviation of the name of the institutions. I intend to call it a monastic. al. n. v i n institution but not a monasteryC because C.F.S. has several h e n g c h i U branch temples in both. Taiwan and overseas, and different non-profit foundations. Its main temple is located in Tainan County of Taiwan. I had conducted deep interviews with ten informants between the winter of 2009 and the summer of 2010 in Tainan, Kaohsiung and Taipei. The names of all my interview informants are anonymous, and these informants are either tonsured at C.F.S., or being visiting monastic members of C.F.S. However, a few of them left C.F.S. after my interviews with them.16 Out of the ten cases, five of them were with monks and five of them were with nuns. They age between the early 16. My interviews with informants had been conducted while they were still monastic members of C.F.S., I did not ask them their reasons of leaving the monastery later. The information about their leaving was heard from other nuns that I know from C.F.S. 12.

(19) thirties and late sixties. In addition, these monks and nuns are ordained bhikshu and bhikshuni, so none of them are novice member. In all fifteen cases, including five extra cases, their years of monastic lives vary from five to more than thirty years. I classified these informants into two categories: had marriage or had no marriage before entering the monastery. Most of my monk informants had married with children before becoming monks. I had no intention to conduct all interviews with monks who have marriages before, but most of the monks in C.F.S. have married with children before becoming monks. Surprisingly, they were cooperative with my. 政 治 大 of my nun informant had marriage before entering the monastery because most of 立. questions, and were willing to share their life stories with me. On the contrary, none. nuns who had married before entering the monastery were unwilling to talk about. ‧ 國. 學. their past.. ‧. In addition to those ten cases, I included five extra cases which I did not conduct. sit. y. Nat. formal interview with them, but I had their information from other informants or. io. er. from my own previous conversations with them. Four out of these five additional cases are about nuns, and one of them is about a monk. Two members of the five. al. n. v i n cases had married with childrenC before entering the monastery. They are all currently hengchi U residing in different temples of C.F.S.. Participant Observation Participant observation is another research methodology that I have used in my thesis. I became a monastic member of C.F.S. since 2004, and before I was tonsured, I had stayed at C.F.S.’ main temple for about eight months as a prospect member. As a monastic member of C.F.S., I was able to spend more time with my informants even before writing this thesis. During my stay at C.F.S., I had several unintentional conversations with other monastic members, and my conversations with them later 13.

(20) became my informal interview information of my thesis. Also because that reason, I was able to involve in the natural environment that I had chosen to be my research subject for a long period of time.. Archival Analysis As mentioned above, there are four kinds of textual materials that I have used as my references. They are anthropological studies on Buddhism, historical studies on Buddhism, texts of Buddhism and other related archival materials such as. 政 治 大. biographies, master and PhD theses and religious publications.. 立. 1.5 Chapter Layout. ‧ 國. 學. In the opening chapter, I give a brief introduction to my research, purposes and. ‧. reasons for doing this research topic and my research methodologies. I have total of. sit. y. Nat. fifteen interview cases included in my research, both monks and nuns, and there is. io. er. the brief background information about these informants in this section. In chapter two, I will talk about the religious institution where I have done my. al. n. v i n C habout C.F.S. The chapter research at. There are detailed facts has been divided into engchi U. nine parts. First, there is a brief introduction about the background of the founder of C.F.S., his daily works and personal Buddhist practices. Second, I move on to the dharma lineage of C.F.S., and the readers must tell the different lineages between monks and nuns in C.F.S. Third, I want to talk about the abbots or abbesses of C.F.S.’ main and branch temples. How much power they have in making decisions for the whole religious institution, what are their qualifications and how they are selected to serve this position? The authority of abbot or abbess of the main temple is never greater than the authority of the founder. Indeed, the charismatic soul leader of C.F.S. is still the founder. Fourth, the discussion will be on people of C.F.S.; I will show the 14.

(21) power structure or management structure at both monastic and organizational levels. In this section, whether years of ordination have any effect on power ranks or not will be answered. Next, it is about background information of C.F.S. monastic members, their motivations to join the Order and the qualification required to join the Order. Sixth, this is a part in describing daily life at the monastery, and the following section is about what kind of cares and welfares that are provided by C.F.S.’ monasteries to their monastic members. Eighth, the section deals with the codes of conduct in C.F.S. beside Buddhist vinaya, each monastery will have its own. 政 治 大 C.F.S. The list tells us how C.F.S. is supported financially. 立. regulations that all members should follow. Lastly, there is a list of types of income of. In chapter three, I will look at different perspectives on relationship between. ‧ 國. 學. Buddhist monks and nuns with their relatives. First, what are the social perspectives. ‧. on the choice of joining monastic life in Taiwan? Next, I want to talk about some. sit. y. Nat. possible effects that might alter or affect the relationship between monks and nuns. io. er. with their families. There are three main possible effects that are discussed: social and personal attitude toward Buddhist renunciation, motivation of renunciation and. al. n. v i n CThird, the importance of blood relation. didU a great research on Buddhist h e nFangTsung i h c nuns in the early seventies in a Hakka village of Taiwan, she provided good. information to this research, and some of her listed facts can still be applied to today’s situations. Therefore, this section is about her results on nuns’ kin relations. Fourth, Buddhist renunciation requires one to leave the family system, however, Buddhist monastic system reestablishes another pseudo-family system within its own religious institution. Fifth, I deal with the reasons why monks and nuns might need helps from their lay families. Next, there are many social changes that might affect kin relation not only to the majority but also monks and nuns. Seventh, this section is about filial piety from both Confucius and Buddhist perspectives, and their conflicts 15.

(22) between two philosophies. The following section discusses whether gender, birth order and marital status of a prospective monk or nun have any effect on their families’ acceptant level for their life choices. Last, I want to find out whether there is any monastic rule or prohibition according to Buddhist disciplines on kin relations of monks and nuns or not. In chapter four, it includes my fieldwork results. There are total of fifteen real cases; six of them are monks and nine of them are nuns. All informants have been categorized into two groups according to their marital status before entering the. 政 治 大 information of the other five cases was collected from my previous or unintended 立 monastery. Ten out of fifteen cases had deep interviews with me, and the. conversations with them or from other monastic informants. Then, I will move on to. ‧ 國. 學. reasons for why these relatives are willing to give supports to their monastic relatives.. ‧. In the sixth section, there will be discussion on pseudo-kinship terms used by monks. sit. y. Nat. and nuns to address each other in the monastery. Following that, there are many. io. er. monks and nuns who also provide supports to their lay relatives when they need, and there are a few cases among my informants who have ever given helps to their. al. n. v i n C h Many monks and families after entering the monastery. nuns ever took leave from engchi U the monastery in order to take care of another sick family member. Lastly, I will define three different types of monastery according to Welch’s definitions. Kin relations of monks and nuns can be very different if their residential monastery belongs to different types of monastery.. In chapter five, I want to discuss some changes in Taiwanese monastic system, and why that is important in affecting kin relations of monks and nuns. Furthermore, the role of education in changing the social status of these monks and nuns and the change of kin relations of monks and nuns today will also be included. Third part of this chapter looks into the monastery’s cares for its monastic members, and what 16.

(23) determines a monastery will have a good monastic system. Lastly, there is a part about what are some related topics that worth conducting further researches because my research is unable to give answers to all these potential questions. Chapter six is the summary and conclusion of this thesis.. 1.6 Transliteration All the Chinese terms in my thesis have been transliterated according to official Chinese Pinyin system, except for terms that have already been done in another form. 政 治 大 Chinese terms are in traditional Chinese. 立. by previous scholars or authors. Chinese characters followed by transliterated. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 17. i n U. v.

(24) Chapter Two: About C.F.S. How close a monk or a nun remains with their families after entering the monastery sometimes depends on the rules, the view of the founder or the person who is in power of decision making of the monastery on this specific relationship. It is important to know about the background information of the monastery before engaging interviews with its members. Monasteries in Taiwan have high individuality. Unlike monasteries in Theravada tradition, it seems that the rules of the monasteries in Taiwan are more or less likely to be set by the founder whereas the rules in. 政 治 大. monasteries of Theravada tradition are mostly based on their precepts. One of the. 立. reasons for that possibility might be the nature of the monastery itself. What I mean. ‧ 國. 學. the nature is in Welch’s categorization on different types of monasteries.17 Most of the monasteries in Theravada tradition are more like large public monasteries in. ‧. China. Even if some of them are not large public monasteries, they accept members. y. Nat. sit. from other monastic community to reside at their monasteries. Therefore, they can. n. al. er. io. also be called hereditary public monasteries. In these two types of monasteries, if. i n U. v. the power is not on the hand of one person, or a group of people who are close to. Ch. engchi. each others for some reasons, then individual rules of the monasteries and decisions will be made by the majority. In this way, their monastery’s code of conduct is less likely to be changed easily, and no one can get special treatment. For this specific topic, one can see different level of acceptance on one single issue among monasteries in Taiwan. For instance, keeping close relationship with one’s family is permitted by one monastery but not necessarily by the other. On the other hand,. 17. There are three types of monastery mentioned by Welch in The Practice of Chinese Buddhism 1900-1950. They are hereditary temples (zi-sun miao 子孫廟), large public monasteries (shi-fang cong-lin 十方叢林), hereditary public monasteries (zi-sun cong-lin 子孫叢林). I will talk about these three types of monastery in chapter four. 18.

(25) monasteries of Theravada tradition have higher consistency, and their main goal is not violating any precept. Moreover, monks are allowed to learn and stay from one monastery to another as long as the monk has a good reputation. On the contrary, it is difficult for monks and nuns to get permission to stay at monasteries which they are not tonsured at. Since the monastic system varies from monastery to monastery in Taiwan, the background of the founder or the person who are in charge should also be taken into consideration when conducting this particular research.. 2.1 The Founder Background:. 立. 政 治 大. In the present age, the old Chan master is said to be the great practitioner, who. ‧ 國. 學. has achieved highly in both Chan and Tantrism.18 He is among the fortieth posterity. ‧. of the Lin-ji Chan sect, a disciple in the direct line from the venerable Xu-yin in Mt.. sit. y. Nat. Fu-chiu, who is the ninth generation of the old Chan master Pen-zhou’s Dharma. io. sect.. al. er. lineage. Besides, the old Chan master also takes the Dharma lineage of Gue-yang. n. v i n C hin 1915. He joinedUthe monastery and started his The old Chan master was born engchi. schooling as a novice when he was seven years old. He graduated from the. Department of Literature of Hu-nan University when he was twenty-one, and in the same year he received full ordination at Gui-yuan Monastery in Han-yang.19 After that, he spent three years in wandering around, visiting exhaustively the skillful masters in the mountains. During that period, he practiced Tantrism under the great Tantric master, and studied Buddhist logic and Sanskrit in Jiang-yang Monastery in Tibet. At the age of twenty-four, he became the abbot of Lei-yin Monastery in Mt. 18. The old Chan master is the founder of C.F.S. He is known to people as the old Chan master. According to the old Chan master himself, Hu-nan University was previously called Yue-lu shu-yuan (嶽麓書院). 19 19.

(26) Fu-chiu; at twenty-eight, he took up the post of abbot of Fan-yin Monastery in Mt. Tian-yue. While wandering in northern Thailand in 1941, the master met an Indian ascetic and a Tantric practitioner by chance, and he passed on the ancient Brahmin Tantrism to the master.. The old Chan master came to Taiwan in 1948 as the consequence of an unexpected recruitment into the army. After having served the army for about ten years, he resumed his monkhood and lived a life of austerity. He had made the. 政 治 大 Tainan County. In 1971, he resided at Gu-yan Chan Monastery where he served as 立 round-the-island wandering twice. In 1964, the master instructed at a monastery in. the abbot and started his career of monastic education. In 1973, he became the. ‧ 國. 學. second abbot of C.F.S.’ main temple.20 In the next year he established, abiding by his. ‧. master’s order, C.F.S. lineage to widely spread out the Dharma lineage.. sit. y. Nat. From 1991 onwards, at the request of the devotees, the old Chan master has. io. er. been establishing centers and monasteries in every urban area. Nowadays there are twenty-seven temples affiliated with the Association of C.F.S. throughout the country.. al. n. v i n On the other hand, to complyCwith the needs of the h e n g c h i U times, the old Chan master. devotes himself to the activities of social welfare, carrying out the Bodhisattva’s vow and practice of loving kindness, compassion, rejoicing and equanimity. Combining the force of seven Buddhist assemblages, the master has founded C.H. Buddhists Association, the Foundation of C.F.S. Charity, the Foundation of C.F.S. Culture and Education, and C.H. Broadcaster. Starting from 1999, the old Chan master has been giving religious talks on television. In order for the Buddha’s teachings to spread all over the world, he makes 20. C.F.S. is an anonymous name for the monastery that I have done my research with. The complete name for this Buddhist institution should be C.F.S. United Merit Foundation because it has many temples and non-benefit foundations. To be short, I will call it C.F.S. 20.

(27) great efforts in integrating various mass media such as magazine, broadcasting, internet, audiovisual dissemination and so on. In particular, the master aspires to spread the doctrines of Wisdom in his whole life. He has been writing for the younger generation to explore the meanings of the Buddha’s teachings, and so far more than eighty works have been published.. Daily Works The old Chan master of C.F.S. spends most of his time in the main temple and. 政 治 大 sangha and lay disciples in recent years. Although he had already passed on his 立 the branch temple in Kaohsiung. Due to his old age, he rarely gives lecture to both. authority and position as an abbot, he still has the authority of making major. ‧ 國. 學. decisions of the monastery. Usually, he will go to his office at the C.H. Broadcaster. ‧. every morning until lunch time. Now, he takes only lunch meal every day, but he. sit. y. Nat. would intake some liquid food if needed. After his office hours, he spends most of his. io. er. private time in writing. Any lay disciple who wants to talk to the founder has to make appointment first with his secretary, and this is even true for his own sangha disciples.. al. n. v i n C h of the monastery People from the managing departments will report to him during engchi U his morning office hours. Secondary matters of the monasteries will be handled by the managing department of the monastery. He did not personally tonsure his direct. sangha disciples for many years, and other respected elder monks or nuns will perform novice ordination ceremonies for him. In addition, new member of the monastery can choose the second character of their dharma names. The first character indicates the dharma lineage, and people from the same monastery will have the same first character. The founder’s later sangha disciples do not have a close relationship with him like those who have been ordained for many years because he no longer educates them one by one. It is hard for him to recognize every 21.

(28) new sangha disciple. His sangha disciples who reside in other branch temples do not have a chance to see him that often, too.. Personal Practices The old Chan master practices both Chan and Tantrism. According to him, Chan practice is still his major focus on the path to Buddhahood, so tantric practice is additional helps on the way. Furthermore, he no longer attends any dharma ceremonies in the main temple, except for special occasions and large Tantric dharma ceremonies.. 立. 2.2 Lineage. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. The old Chan master himself belongs to the fortieth generations of Lin-ji Chan. ‧. sect (臨濟禪宗) and the ninth generation of Tien-yue (天岳) Dharma lineage of. y. Nat. Venerable Pen-zhou (本晝). The founding Chan masater of Lin-ji Chan sect (臨濟禪宗). er. io. sit. was Chan master Yi-xuan (義玄), and the founding Chan master of Tien-yue (天岳) lineage, Chan master Dao-min (道忞 1596-1674), was the thirty-first generation of. al. n. v i n Lin-ji Chan sect (臨濟禪宗). TheC following is the ancestor spectrum of Tie-yue (天岳) hengchi U lineage:. Mu-chen Dao-min (木陳道忞)→ Tien-Yue Pen-zhou (天岳本晝)→ Yua-guo Wei-zhen(元果惟真)→ Miao-yun Heng-hou(妙雲恆厚)→Dao-ti Yong-zhi (道體用 智)→An-zhou Ning-xin (安照寧心)→Da-din Qin-fa (大定勤法)→Zhi-zhen Yue-ji (智正 月季)→Pin-fan Xu-yin (平凡虛因)→ the founder of C.F.S.. The old Chan master was tonsured by Chan master Xu-yin (虛因 1867-1967). Monks and nuns of C.F.S. belong to four different dharma lineages actually. Most the nuns 22.

(29) who follow the old Chan master belong to the second generation of C.F.S. lineage, and this lineage was established by the old Chan master in Taiwan around 1960. Monks belong to Tien-yue (天岳) lineage. Besides, there are nuns in G. Y. Temple belong to the Gui-yuan (歸元) lineage but not C.F.S. lineage, and because their dharma lineage is different from nuns of C.F. S. lineage, they reside in a monastery which belongs to their own lineage. One can tell which lineage the monk or the nun belongs to by looking at the first Chinese character of the monk’s or the nun’s dharma names. Only monks or nuns who belong to the same dharma lineage will. 政 治 大 Gui-yuan sect do not have the same first Chinese character for their dharma names 立. have the same first Chinese character in their dharma names. Therefore, nuns from. as nuns of C.F.S. lineage. Another Gue-yang (溈仰) lineage had passed onto a monk. ‧ 國. 學. called Z.C. in 1990, but he left C.F.S. for his own Buddhist practices long ago. Monk. ‧. Z.C. belonged to Tien-yue (天岳) lineage at the time of his novice ordination, but. y. Nat. since he took over the responsibility of passing on another lineage, so all his tonsure. n. er. io. al. 2.3 The Abbot. sit. disciples belonged to Gue-yang (溈仰) lineage, too.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Main Temple: C.F.S. has several branch temples in different locations. Its main temple is located in Tainan, and its abbot is Ven. Z. X., a monk who has been ordained for almost thirty years. Currently, he is in his sixties. The old Chan master passed the position to him on the first of January in 2008. He had a degree in civil engineering, and got an honorary doctoral degree in meditation from University of Kelaniya Sri Lanka. For many years, his job is mainly giving Buddhist lectures, and so far, he has been invited to Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Australia to lecture. 23.

(30) Besides lecturing, he has served for many positions such as director of the Chinese Buddhist Society, director of C.F.S. Cultural and Educational Foundation, director of C.F.S. Charity Foundation and director of Chinese Buddhist Temples Association. Currently, he is also the principal of the C.F.S. Buddhist College and the publisher of C.F.S. Magazine. The abbot’s personal practice is Chan medication. He focuses his Buddhist study on Diamond sutra and the vinaya. Besides his major studies, he is familiar with the teachings given by the old Chan master. During the dharma ceremony of feeding the. 政 治 大 Thus, he also practices Tantrism for this purpose. 立. hungry ghost (Yien-ko 燄口), he sometimes acts as the vajra master of the ceremony.. ‧ 國. 學. Abbots or abbesses of the branch temples:. ‧. In C.F.S. for the past thirty-eight years, the old Chan master was the abbot of all. y. Nat. C.F.S.’ temples, so there was only one abbot for all its temples. Therefore, the. er. io. sit. executive administrator (Gian-yuan 監院 or Dan-jia 當家) was the highest position in all branch temples. That was the time when those branch temples were small in. n. al. Ch. 21. both size and the number of member in residence.. engchi. v i n Now, these small branches had U. been built into larger temple (Ci 寺) in recent years, so the old Chan master decided to select abbots for these larger branches. There are two branches having abbesses now. One is Prajna Monastery in Kaohsiung and Big Cloud Monastery in Taichung. However, if there is no qualified person to be the abbot or abbess of larger branch temples, then the position will remain empty. Both Prjana Monastery and Big Cloud Monastery are nunneries, and they both belong to C.F.S. lineage. The abbess of Big Cloud Monastery is in her mid forties. She. 21. We call these small size of branch temples lecture hall (Jiang-tan 講堂) in Chinese. 24.

(31) is from a farming family in Pingtung. She was ordained by the old Chan master as a novice about sixteen years ago. Before becoming the abbess of the monastery, she was responsible for human resources department of C.F.S., and was the assisting upadhyaya (Shou-zuo 首座) of Prajna Monastery.. Authority of the abbot According to the common regulations of the monastic community (Chang-zhu Gue-yue 常住規約) published by C.F.S., the major responsibilities of an abbot are. 政 治 大 the main temple is greater than the abbot or abbess of branch temples because the 立. leading the sangha and managing temple’s properties. The authority of the abbot of. managing department of the main temple can decide who and how many people. ‧ 國. 學. would transfer to the branch temples. To my knowledge, the abbot does have right to. ‧. most decisions of C.F.S.’s main temple. However, he still does not have the right in. sit. y. Nat. making critical decision on important issues at an organizational level. For example,. io. er. he has no right to decide whether C.F.S. should establish its own Buddhist college or not. Such a decision is always made by the old Chan master. Moreover, he cannot. al. n. v i n Cahnew building in theUmain temple or not. All the decide whether they should have engchi. constructional decisions will and has to be made by the old Chan master. The abbot can make secondary decisions. It is hard to decide what a primary decision is and what a secondary decision is. It depends on whether the old Chan master wants to intervene with these matters or not. This is different from the authority of an abbot in China. According to Welch, the abbot has rights to appoint all senior officers, to confer all the higher ranks, to punish or reward the member, and to decide how to spend the monastery’s income.22 The authority of the abbots in China seems to be greater than the abbot of C.F.S. However, there is one similarity for sure, and that is 22. Welch, 1967, pp.145-151. 25.

(32) the remaining authority of the previous abbot or abbots. Welch pointed out one critical observation that showed how Chinese familial system had well established in the monastery.23 The abbot of the monastery in China had to consult the previous abbot for opinions when they had to make important decisions, especially when it was an economical matter. There was usually at least one previous abbot in most of the monasteries. To Welch, the current younger abbot would consult the previous elder abbot on important questions “as if he were the grandfather in a large Chinese family”, and he believed that this was influenced by the Chinese family system.. 政 治 大 Taiwan. In most of time, the abbots and abbesses will inform and report what had 立 Such a circumstance also exists in not only in C.F.S. but also many monasteries in. happened in the monasteries to the old Chan master once awhile. The old Chan. ‧ 國. 學. master, the previous abbot, will have the most charismatic characteristics in the. ‧. monastery. Both sangha and lay disciples’ focus is always on the old Chan master.. sit. y. Nat. Therefore, there is not much information about the background of the abbot or. io. er. abbess on C.F.S.’s website, but you can find detailed introduction to the old Chan master on its website and publications. This is usually the case in many other. n. al. monasteries, too.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Qualifications There were five qualifications said by Welch that one should have in order to be chosen as an abbot: past administrative experience, being an expert in Vinaya and be faultless himself, ability to teach Buddhist doctrine and texts, good connections with lay supporters (though not necessarily), and a will to serve.24 These qualifications are also part of the considerations of the old Chan master in choosing a 23. Welch,1967, pp.145-151.. 24. Welch, 1967, pp.151-152. 26.

(33) new abbot. However, not all the abbots of C.F.S. are able to teach Buddhist doctrine and texts or be an expert in Vinaya. The teaching job relies mostly on professor monks and nuns in the monastery. Besides that, the other three qualifications are prerequisites for being an abbot in C.F.S. Since selection of an abbot in C.F.S. is usually not democratic, the old Chan master has his own considerations when selecting a new abbot. In addition, there is no specific requirement on years of monastic life. However, when one is experienced with administrative jobs in the monasteries, he or she must have spent years in monastic life.. Selection of an abbot. 立. 政 治 大. The abbot of C.F.S.’ main temple is selected by the old Chan master himself.. ‧ 國. 學. Sometimes, the abbot or abbess of a branch temple is selected by members of the. ‧. temple, but it only happened once in Prajna Monastery. In the main temple of C.F.S.,. sit. y. Nat. the abbot can be a monk despite it is a nunnery with different lineage. This can never. io. er. be happened the other way around in which there can never be an abbess in a bhikshu monastery. As a hereditary public monastery, the position of abbot would. n. al. i n Cishnot tonsure in C.F.S. never be given to a member who engchi U. v. 2.4 The People of C.F.S.. Management structure: In the tradition large public monastery in China, there are forty-eight positions or jobs in the management of a monastery. The main temple of C.F.S. or other branches is really not that large comparing to these monasteries. Thus, they do not have so many positions. On the other hand, C.F.S. has many sub-institutions besides its main temple, so the management structure of C.F.S. has two levels: at the monastic level 27.

(34) and at the organizational level.. At the Monastic Level: The old Chan master or upadhyaya (fang-zhang he –shang 方丈和尚) is always in the highest rank in the monastery. There are six departments directly under upadhyaya. First, abbot is responsible to lead the sangha and manage all the monastery’s properties. Second, assisting upadhyaya (shou-zuo 首座) helps out upadhyaya to manage all monastic matters. Assisting upadhyaya also serves to. 政 治 大 texts to both the sangha and the public. Third, executive administrator (jian-yuan 監 立 educate all the sangha members, so he or she has to teach Buddhist doctrine and. 院 or dang-jia 當家) is responsible for land management, arranging sangha’s. ‧ 國. 學. Buddhist practices, and enforcing all policies set by the monastery. Under executive. y. Nat. following six jobs:. ‧. administrator’s supervision, there are many members who are responsible for the. er. io. sit. a. Fu-ci (副寺): people who serve for this job have to take care of clothing, living, food, and transportation matters. There are two sub-groups under. al. n. v i n this job. wui-ku (外庫) C is responsible to buy anything that is needed in the hengchi U. monastery. The sangha member can also ask them to buy personal things for them because they might not have time to go to the market. Another. ku-tou (庫頭) take care of the storage room. They have to make sure things in the storage room are well organized. Anyone who needs, for example toilet papers, can go ask them for it. All fruits and flowers needed for all Buddha halls will be prepared by them, too. They also have to divide fruits and food donations for all members every day. b. Jian-ci or Jou-cha (監寺;糾察): They will make sure every monastic member follows the rules and attend Buddhist practices all together. Therefore, they 28.

(35) act as inspectors. c. Tang-tou (堂頭): Tang-tou has to take care all constructional matters. For instance, when the construction workers are working on a new temple’s building, he or she is the one to watch over them. In addition, Tang-tou is responsible for maintaining the buildings. d. Dian-cuo (典座): There are two sub-groups under this job. First, xiang-ji (香 積) have to cook all three meals a day. The other is xin-tang (行堂) who serve as waiters in the dining hall.. 政 治 大 accounting, calculating the budget, and assisting to manage monastery’s 立. e. Finance (cai-wu 財務): The finance department is responsible for. properties.. ‧ 國. 學. f. Secretary (書記 shu-ji): Secretaries have to manage database of the. ‧. monastery, to record and save lay supporter’s information in the computer,. sit. y. Nat. to take down everything discussed during conferences and put them into. io. er. written documents.. Fourth, administrator of reception office (zhi-ke 知客) supervises the reception. al. n. v i n C hThe reception department department (or guest department). is the first place engchi U. where a guest or lay supporters will visit before going to other places of the temple. Therefore, they have to answer guests’ questions, to accommodate lay guests or monks and nuns from other monasteries, to arrange bedrooms for their sangha members, to keep lay guest’s dormitories and sangha members’ residences clean, to answer all the phone calls and contact with outside, and the monastic members’ benefits and welfares. In addition, they are responsible to announce all importance events to the sangha by writing them down on the bulletin board. There are three departments under the supervision of administrator of reception office: 29.

(36) a. Zhou-ke (照客): People who are in this department will take shift to work in the office. There are morning and afternoon shifts. During these shifts, they have to answer phone calls, contact with the outside if needed, clean the office, accommodate all guests, and update bulletin board. b. Liao-yuan (寮元): They have to make sure residences of the sangha members are clean. Before when members had to burn woods for hot water, this was also the job of liao-yuan. c. Department of Welfare (Fu-li bu): There will be one person responsible for. 政 治 大 sells Buddhist books, food and souvenirs. All the incomes of this bookstore 立 taking care of the bookstore located beside the reception office where it. pay for sangha’ medical bills and welfare expenses.. ‧ 國. 學. The fifth position directly under upadhyaya is the chant leader (wei-nuo 維那) who. ‧. arranges all dharma ceremonies and ritual services for lay people who request for it,. sit. y. Nat. caring for all Buddha halls and ancestral ash altar, and decorating the Buddha halls.25. io. er. There are two departments under the chant leader’s responsibilities: a. Buddha halls (dian-tan 殿堂): People who are responsible for these Buddha. al. n. v i n C h and decorationsUbefore all kinds of ceremony. halls have to do preparations engchi. b. Garden (hua-pu 花圃). Last position is the education unit which has four departments: a. Buddhist college: C.F.S. Buddhist College is located in the main temple in Tainan, and the college accepts both male and female lay or sangha students. Strictly speaking, it does not have age limit if you want to study in the college. One does not have to pay for tuition fee or living cost except for your own spending. However, there is one rule that lay students have to join 25. This position is like the head rector in the church, but the chant leader in Buddhist monastery has far more complex responsibilities than a head rector in the church. 30.

(37) the Order within half a year study at the college. If one does not want to join the Order, then he or she must leave the college. There is no entrance exam to the college. The number of student decreases and the age of new student increases in these years. Moreover, these students have different educational background, and most them are looking forward to join the Order before entering the Buddhist college. Although C.F.S. has its own Buddhist college, but not every member has the chance to study in the college because the monastic positions are always under a condition of. 政 治 大 Magazine: A monthly publication called Fuo-yin was first published by the 立 human resources shortage.. b.. old Chan master in the late 1972. It had published a total number of 272. ‧ 國. 學. issues before its publication stopped. C.F.S. Magazine, on the other hand,. ‧. was first published on March, 29, 1989. It is also a monthly-based. sit. y. Nat. publication except for the combined issue of January and February. Until. io. er. December of 2009, there were 243 issues being published. In addition, this magazine is free for people who request for it. Thus, it is usually the way. al. n. v i n Cthe that people know about from all over the world. h emonastery ngchi U. c. Ceremonial affairs (Fa-wu 法務): This position is responsible for all kinds of activity in the monastery. Fa-wu has to set up academic schedule of the monastery, and the person who serves this position will call a meeting with the abbot and supervisors of other departments. The management structure can be illustrated by diagram 1.. Selection criteria: The old Chan master not only chooses abbots or abbesses for the main and branch temples but also their executive administrators and people of finance 31.

(38) department. In addition, monks or nuns who serve for positions of C.F.S. Buddhist College are also appointed by the old Chan master. Although the administrator of reception office and the chant leader are at the same power rank with the executive administrator and the abbot, the latter two can choose people to serve for the first two positions with their own will. All other lowest positions of the monastery will rotate their positions in a three-month base, and members who are at the branch temples can also ask for a change to go to another branch temple or back to the main temple during job rotation, too. The abbot, the executive administrator, the. 政 治 大 should take which position or be transferred to a branch temple. C.F.S.’ branch 立. administrator of reception office, and the chant leader together will decide who. temples do not have so many positions as the main temple because they are small in. ‧ 國. 學. size and number of sangha member. Their basic positions will be rotated in a. ‧ sit. y. Nat. At Organizational Level:. io. er. two-week base.. Besides Buddhist temples, C.F.S. has many non-profit foundations, radio. al. n. v i n C orh overseas. Thus, there station, and bookstores in Taiwan is another management engchi U. structure at the organizational level. Moreover, there are many sangha members of C.F.S. who work not at temples but at these non-profit or profitable institutions. The highest in rank at organizational level is also upadhyaya (fang-zhang 方丈). Next to upadhyaya is the position called cuo-yuan (座元). Cuo-yuan works as the assistant of upadhyaya, so whenever upadhyaya is unavailable, cuo-yuan can represent him.26 Currently, no one is at this position. Under cuo-yuan, the general secretary (mi-shu zhang 秘書長) administers the following institutions and positions: 26. Both cuo-yuan 座元 and assisting upadhyaya 首座 help to assist with upadhyaya 方丈和尚, but cuo-yuan is in higher in ranks of hierarchy. 32.

(39) a) Three positions: human resources arrangement, secretaries, assistants of upadhyaya (ci-zhe 侍者). b) Institutions: i. Educational and Cultural Affairs: P.Y. Publishing, F.J. Educational and Cultural Foundation, C.F.S. Educational and Cultural Foundations, F.T. Buddhist College (this college was closed), and bhikshu and bhikshuni professors (jiao-shou shi 教 授師). ii. Charity Affairs: C.F.S. Charity Foundation. 政 治 大. iii. Social Organization: C.H. Buddhist Association iv. Overseas institutions. 立. vi. all temples of Tien-yue lineage. ‧. vii. all temples of Gui-yuan sect. 學. ‧ 國. v. all temples of C.F.S. lineage. sit. y. Nat. C.F.S. has one radio station and J.H Enterprise, but these two institutions were not. io. er. included in this management structure. I believe they are independent institutions. C.F.S.’ general secretary is also the general manager of both C.F.S. Broadcasting and. al. n. v i n C h structure at theUorganizational level can be J.H. Enterprise now. The management engchi illustrated by diagram 2.. Ranks: monastic years and power ranks The number of years of a monk or a nun since the bhikshu or bhikshuni ordination is called jie-la (戒臘) in Chinese. The longer the jie-la you have the higher in sangha rank you are at.27 This sangha rank is different from ranks in management. 27. In Chinese Buddhism, a monk or a nun who reach the age of twenty years old can apply for higher ordination, and it is called Three Platform Ordination (shan-tan da-jie 三壇大戒). The three platforms mean three different types of precept that a monk or a nun accept: sramanera or sramanerika, bhikshu or bhikshuni, and lastly bodhisattva precepts. Monk or nun who is eligible to take these 33.

(40) structure because the longer the jie-la you have does not guarantee you with a higher position in the management structure. People who have longer jie-la are the elders within the monastic community. They are seemed to have higher wisdom and more experienced with Buddhist practices, so all members will respect them. In C.F.S., members who have more than thirty years of jie-la can retire from all monastic jobs, and spend their time on their own will. Before when the number of sangha member is sufficient to fulfill all monastic positions, members who have more than twelve years of jie-la is exempted from positions in the kitchen because jobs in the kitchen. 政 治 大 decreasing but C.F.S. is expanding. 立 2.5 Background of the Monastic Members. 學. ‧ 國. are toilsome. This is not the case now because the number of sangha member is. ‧. The main temple of C.F.S. has some monks and mostly nuns. This is never the. y. Nat. case in monasteries in China. According to Welch’s descriptions of monasteries, it is. er. io. sit. either a monastery for monks or a nunnery. It’s very unlikely to have both sangha28 living in the same monastery. However, there are many monasteries having both. al. n. v i n CTaiwan. sangha in the same monastery in should be more than three hundred U h e nThere i h gc monks and nuns who had been tonsured by the old Chan master.29 The number of. nuns exceeds the number of monks. Monks and nuns of C.F.S. can also tonsure his or her own disciples. Therefore, there are sangha members of different dharma generations living in one monastery. Furthermore, there are sangha members from. precepts will go to the monastery where it holds the ordination ceremony. 28 bhikshu and bhikshuni sangha. 29 The recently published (April, 2010) pamphlet on brief introduction about C.F.S. and C.F.S. Special Issue of Thirty Years indicated that the number of the old Chan master’s tonsure disciple was over three hundred, but I believe the number should be more than they indicated. Many statistics provided by C.F.S. in any form is not that accountable. One is not sure whether the number of its member indicates the old Chan master’s tonsure disciples or all members currently residing in its temples. Even if they clearly indicated that, the number seems to be inaccurate. 34.

數據

相關文件

• One technique for determining empirical formulas in the laboratory is combustion analysis, commonly used for compounds containing principally carbon and

The oxidation number of oxygen is usually -2 in both ionic and molecular compounds. The major exception is in compounds called peroxides, which contain the O 2 2- ion, giving

Teachers may consider the school’s aims and conditions or even the language environment to select the most appropriate approach according to students’ need and ability; or develop

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive

Courtesy: Ned Wright’s Cosmology Page Burles, Nolette & Turner, 1999?. Total Mass Density