▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆▆

………

An Investigation of Knowledge Sharing from a Social

Capital Perspective: How Social Capital and Growth

Needs Affect Tacit Knowledge Acquisition and Individual

Satisfaction

Shu-Chen Yang and Cheng-Kiang Farn

Department of Information Management,

National Central University, Taiwan

Accepted in March 2006

Number:0506015ˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍˍ Abstract

This study examines the effects of social capital and growth needs on individual knowledge acquisition within software project teams through the adoption of a multi-informant questionnaire approach. The results indicate that social capital is helpful in tacit knowledge acquisition, which in turn leads to higher satisfaction. In particular, the relationship between affect-based trust and team satisfaction is not significant but mediated by tacit knowledge acquisition. The effect of affect-based trust on tacit knowledge acquisition is not contingent on growth needs. However, the relationship between shared values and tacit knowledge acquisition is stronger among individuals who possess a low level of growth needs. Several managerial implications and limitations are proposed.

Keywords: Growth needs, multi-informant, social capital, satisfaction, tacit knowledge acquisition

……… 1. Introduction∗

Kogut and Zander (1996) argue that knowledge sharing is more efficient and frequent inside a firm than in the market as coordination, communication, and learning are facilitated by employee identity. Particularly in project based organizations, such as software development firms, knowledge sharing usually occurs within each project team, rather than across the whole organization, as tasks and objectives may differ among project teams. Hence, the issue of how to efficiently share knowledge among team members becomes of primary concern to project managers even though knowledge sharing – particularly tacit knowledge sharing – in project teams has not been

Shu-Chen Yang, Department of Information Management,

National Central University,Taiwan,No.300, Jhongda Rd., Jhongli City, Taoyuan County 320, Taiwan. Tel.: 886-3-422-7151 ext. 66548 Email: henryyang@mgt.ncu.edu.tw; Cheng-Kiang

Farn, Department of Information Management, National Central

University, Taiwan.

sufficiently investigated or understood (Koskinen, Pihlanto, & Vanharanta, 2003).

Tacit knowledge is shared only through intrinsic motivation, such as sociability and friendship (Osterloh & Frey, 2000). That is, tacit knowledge sharing between individuals is socially driven. Individuals may take advantage of social relationships to easily acquire tacit knowledge from others. Recently, several researchers have become increasingly interested in social capital in organizations (e.g., Bolino, Turnley, & Bloodgood, 2002; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Social capital may facilitate organizational value creation through the process of knowledge dissemination and combination (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Individuals may also benefit from social capital embedded in the social network in which they are members (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Kostova & Roth, 2003). For example, individuals may acquire tacit knowledge from others through trusting relationships to accomplish their jobs and meet their developmental needs.

The primary goal of this study is to investigate the relationship between individual social capital and tacit

knowledge acquisition within software project teams. Personal needs may also be met through the acquisition of know-how and experience with others that lead to higher individual satisfaction. Judge, Thoresen, Bono and Patton (2001) suggest that individual satisfaction is highly positively related to professional job performance. Achievement motivation may be a determinant of whether social capital is mobilized for the acquisition of tacit knowledge from others. Hence, we also examine the effect of tacit knowledge acquisition on individual satisfaction and include growth needs as a moderator. We adopt a multi-informant questionnaire approach. That is, respondent social capital is reported by the individual and by members within the project team to avoid self-reporting bias.

2. Conceptual Arguments and Research Model

2.1 Tacit Knowledge Acquisition and Satisfaction

Knowledge is defined as a justified belief that improves an entity’s capacity for effective action (Nonaka, 1994). Nonaka (1994) addresses two dimensions of human knowledge: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge can be formally and systematically articulated and disseminated in certain codified forms, such as manual or computer files (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Tacit knowledge, however, is knowledge of a personal quality (Nonaka, 1994) that is deeply rooted in action, experience, thought, and involvement in a particular context (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Even though it determines behavior, tacit knowledge can be so ingrained that individuals lack full awareness that they possess it (Koskinen et al., 2003). The ability to ride a bicycle, knowledge of an expert baseball player, and the ability to debug computer programs are all examples of tacit knowledge. Most tacit knowledge is difficult to convert into explicit form to make it easier to transfer (Berman, Down, & Hill, 2002). Nonaka (1994) suggests that tacit knowledge is transferred through sharing metaphors or experiences during social interaction without substantial knowledge loss. Thus, the efficiency of tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing is highly dependent on social networks (Käser & Miles, 2002).

Tacit knowledge is similar to the concepts of skill (Berman et al., 2002), practical know-how (Koskinen et al., 2003), or experience. Individuals are often reluctant to share their tacit knowledge with others because of the

potential risk of losing an advantage and the lack of a proper reward mechanism (Osterloh & Frey, 2000). However, individuals must acquire task-related knowledge from other members in a highly task-dependent group to perform their jobs (Van Der Vegt, Emans, & Van De Vliert, 2000). For innovative teamwork in particular, such as software development, most task-related knowledge is tacit in nature and is crucial for performance enhancement (Käser & Miles, 2002).

Tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing cannot be measured directly due to its intangible nature (Berman et al., 2002). Choi and Lee (2003) consider the analysis of organizational knowledge sharing and acquisition from explicit versus tacit-oriented perspectives. The explicit-oriented perspective corresponds to knowledge sharing and acquisition through codified forms, whereas the tacit-oriented perspective corresponds to knowledge sharing and acquisition through interpersonal interaction. Individuals acquire tacit knowledge and personal experience only through a tacit-oriented approach that emphasizes social networks. In this study, tacit-oriented knowledge acquisition is used as a surrogate for tacit knowledge acquisition.

For the task completion of software development projects, individual team members seldom possess all of the necessary skills, and need to acquire knowledge from various sources, such as technical documents or other team members. Much of the knowledge about software development, such as debugging and system analysis skill, is highly tacit in nature and is only acquired and shared through interpersonal interaction. Individuals may meet their personal and professional needs through the acquisition of know-how and experience from others as tacit knowledge is a potential source of competitive advantage. For example, an individual’s programming capabilities will improve with the easy acquisition of various debugging skills from others in the software project team. Thus, tacit knowledge acquisition during teamwork performance leads to personal satisfaction. Van Der Vegt et al. (2000) further distinguish between job satisfaction and team satisfaction as individuals may be satisfied with their jobs but not with their team members. An individual’s easy acquisition of know-how and experience from other team members improves the social relationship and the individual’s level of satisfaction toward those members. In addition, individual developmental needs are satisfied when there is easy

acquisition of tacit knowledge in the job, which leads to increased job satisfaction. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Tacit knowledge acquisition positively affects

team satisfaction.

H2: Tacit knowledge acquisition positively affects job

satisfaction. 2.2 Social Capital

2.2.1 The nature of social capital

Social capital can be conceptualized as a set of resources that is derived from the social network in which social actors are located (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Like other forms of capital, social capital is considered a valuable asset for social actors that range from individuals to firms (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Social capital is analyzed from both structural and relational perspectives (Kostova & Roth, 2003). Based on the structural view, social capital provides value by virtue of relationship configurations among social actors. However, the network structure itself only creates opportunities for the leverage of the social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002). The relational aspect of social capital addresses the nature of the social relationship, such as trust and trustworthiness (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). The quality of relationships among social actors provides the motivational source of social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002). For example, an individual is willing to help others out of commitment to a shared good instead of self-interest.

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) suggest that different aspects of a social context are considered in terms of the relational, cognitive, and structural dimensions of social capital. This three dimensional framework is employed to investigate the relationship between social capital and intra-organizational phenomena (e.g., Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998; Bolino et al., 2002). Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) consider social capital to be essential for the dissemination of knowledge within organizations. Bolino et al. (2002) propose that social capital is an important resource for individuals that work together. Nonaka (1994) also suggests that the sharing of tacit knowledge between individuals may be facilitated by joint activities. Although social capital is jointly owned by all actors that are involved in a relationship, individuals also benefit from the personal “goodwill” that results from

good relationships with others (Adler & Kwon, 2002). In this study, we argue that individual social capital is helpful in the acquisition of tacit knowledge within the software project team.

2.2.2 Relational dimension of social capital

The relational dimension of social capital can be conceptualized as the assets that are created and leveraged through ongoing relationships, such as respect and friendship, that influence behavior (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). This dimension describes the extent to which there is an affective quality to the relationship among social actors (Bolino et al., 2002). These affective qualities are manifested by trust, norms, obligations, and identification (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). In this study, we focus on the trust quality because it has received much attention in recent organizational and management research. Furthermore, trust is also an important dimension of Leana and Van Buren’s (1999) definition of social capital.

Higher trust facilitates social exchange, communication, and cooperation between individuals, and also enhances teamwork performance (McAllister, 1995). When individuals begin to trust others, they become more willing to share their resources as they know that others may someday reciprocate and their interests will not be sacrificed (McAllister, 1995). That is, as trusting relationships develop, actors build up goodwill that is valuable for other actors in the social network (Adler & Kwon, 2002). It is reasonable that individuals are willing to share their tacit knowledge with others who have a reputation of trustworthiness. Thus, trustworthy individuals also easily acquire tacit knowledge from others through personal interaction and mentoring within a team.

Trusting behavior may be motivated by strong emotion toward others and by rationale for why others merit trust (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). McAllister (1995) terms these two foundations of trust as “affect-based trust” and “cognition-based trust”. Individual needs additional information and rational evidence about others for the development of cognition-based trust (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). However, affect-based trust is based on the emotional ties that link individuals, such as friendship, love, or care (Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995). In this study, affect-based trust is employed to characterize the relational dimension because relational social capital represents the affective quality of interpersonal relationships (Bolino et al., 2002). Individuals are willing

to share their tacit knowledge with trustees even if there are no extrinsic benefits to be reaped from sharing. Osterloh and Frey (2000) also suggest that sociability and friendship are the most important factors that influence tacit knowledge sharing. Moreover, a trustworthy individual can build up goodwill with which to secure benefits from others. It is reasonable to argue that individuals easily acquire tacit knowledge from other members when they are considered trustworthy in their respective project teams. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Affect-based trust between an individual and team

members positively affects tacit knowledge acquisition.

In essence, affect-based trust may be considered as a friendship between individuals (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). It is intuitive to argue that individuals who work with friends express more co-worker satisfaction toward them. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H4: Affect-based trust between an individual and team

members positively affects team satisfaction. 2.2.3 Cognitive dimension of social capital

According to Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), the cognitive dimension of social capital can be conceptualized as a common understanding among social actors through shared language and narratives. This cognitive quality is embodied in attributes, such as shared vision or shared values that facilitate individual and collective actions and common understanding of proper actions and collective goals (Tasi & Ghoshal, 1998). A higher level of cognitive social capital gives group members a common perspective that enables them to develop similar perceptions and interpretation of events. Where shared understanding exists, members within the same group more easily share and acquire knowledge and resources (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998).

According to Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), cognitive social capital reflects a common understanding among social actors through shared language and narratives across the whole organization. Shared values that describe shared perceptions and interpretation of organizational practices and polices is employed to embody the concept of common understanding in our study. When members have similar interpretation of how tasks should be

performed collectively, they more easily exchange task-related know-how and experiences without teamwork misunderstandings. In addition, shared values between individuals lead to the formation of mutual identification that facilitates tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing within a social network. Accordingly, tacit knowledge may be easily acquired through the establishment of shared understanding between individuals. We propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Shared values between an individual and team

members positively affect tacit knowledge acquisition.

Common understanding and shared values may also facilitate the development of trusting relationships between individuals (Brashear, Boles, Bellenger, & Brooks, 2003). Morgan and Hunt (1994) also suggest that shared values inspire individuals to be more committed to interpersonal relationships. Affect-based trust involves care and concern for the interests of others (McAllister, 1995), which implies the existence of common values. With collective values, team members are willing to make emotional investments in their relationships, as they expect cooperation without misunderstanding, and will not be hurt by others’ pursuit of self-interest. Hence, we propose:

H6: Shared values between an individual and team

members positively affect affect-based trust. 2.2.4 Structural dimension of social capital

Finally, the structural dimension of social capital can be conceptualized as the overall pattern of relationships among social actors (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). It is also considered as the extent to which actors in a social network are connected (Bolino et al., 2002). Social interaction among actors is employed to represent the structural dimension of social capital in this study. Frequent social interaction provides actors with the opportunity to get to know one another and create shared understanding (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). As individual attributions that concern the motives for others’ behavior are the foundations of affect-based trust, individuals gather sufficient information through frequent social interactions to make confident attributions (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). Hence, we propose:

H7: Social interaction positively affects the

development of affect-based trust between an individual and team members.

3. Research Methods Social interaction also plays a critical role in the

shaping of a common set of values among group members (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Through the process of social interaction, actors realize others’ values about how things should be done and are likely to create a new set of shared values based on common understanding. Therefore, we propose:

3.1 Sample

This research was carried out in 2 universities, UA and UB. Individuals who took courses with teamwork projects were candidates for our study. In these courses, students were divided into several groups and each group was asked to perform certain software projects. Nine courses in two universities satisfied our selection criteria. We invited the candidates to participate in our study toward the end of these courses. Of these selected courses, six were courses with teamwork graduation projects and three were courses with teamwork term projects. We used a student sample for three reasons. First, the tasks of the projects groups, i.e. software development, were the same as the field population we aimed to generalize. Second, the tasks for every sample within each project group were highly interdependent. Third, we could control extraneous factors (for example, each respondent in our student sample were involved in a project team from the beginning to the end) within the student sample to enhance internal validity. This would have been difficult to accomplish in real field settings because of the complicated multi-informant research design. In other words, a student sample was chosen to ensure control over extraneous sources of variation in tacit knowledge acquisition and individual satisfaction.

H8: Social interaction positively affects the development

of shared values between an individual and team members.

2.3 Growth Needs

Social capital is a valuable resource with which to secure benefits for individuals (Adler & Kwon, 2002). However, the efficiency of the mobilization of social capital depends on whether individuals are willing to oblige. For example, individuals with low achievement motivation may not actively ask for friends’ assistance for their own development. Accordingly, individual growth needs moderate the relationship between social capital and tacit knowledge acquisition. Hackman and Oldham (1980) suggest that growth needs are a personal attribute that refer to the extent to which individuals respond to their jobs with high levels of motivation. That is, individuals with high growth needs desire achievement and self development by meeting challenges and exercising workplace autonomy. This implies that individuals with high growth needs are good at the mobilization of social capital to achieve individual and organizational objectives. In a highly task-dependent group, such as a software project team, members must acquire greater assistance from others to perform their jobs (Van Der Vegt et al., 2000). Arguably, individuals with high growth needs actively take advantage of their social capital to acquire tacit knowledge for task completion. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H9a: Growth needs positively moderate the relationship

between affect-based trust and tacit knowledge acquisition.

H9b: Growth needs positively moderate the relationship

between shared values and tacit knowledge acquisition.

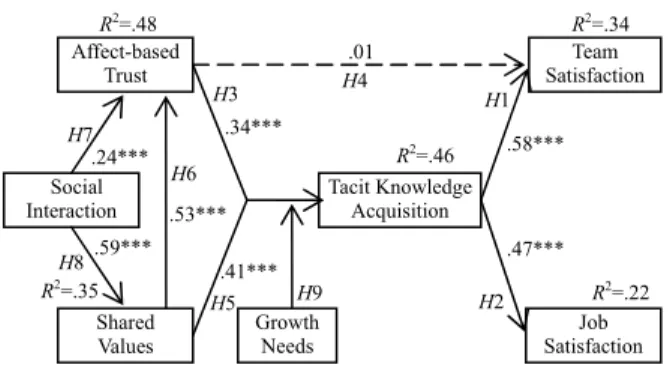

Our research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Model

3.2 Measurement

All constructs were adapted from pre-validated measures in previous related studies (see Appendix). All items used to measure the research constructs except

R2=.22 .47*** .58*** H9 .41*** .59*** .24*** .53*** H6 H4 H8 H7 H5 H3 H2 H1 Social Interaction Affect-based Trust R2=.48 Team Satisfaction R2=.34 .01 .34*** R2=.46 Tacit Knowledge Acquisition R2=.35 Shared

Values Growth Needs Satisfaction Job

χ2(df)=297.239(128), CFI=0.961, NFI=0.933, RMSEA=0.077

The figure also shows the structural model results with Maximum Likelihood estimation. R2 represents the variation

explained in endogenous constructs. *p<.1. **p<.05. ***p<.01.

Growth Needs were evaluated on seven-point Likert scales that ranged from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (7)”. Items for Growth Needs from Hackman and Oldham (1980) were evaluated on seven-point scales that ranged from “would like to have this to a moderate degree (or less)” (coded 1) to “would like to have this to a great degree” (coded 7). As the lowest degree may have confused respondents, we employed an eight-point scale that ranged from “do not like at all” (coded 1) to “like this to a great degree” (coded 8) for Growth Needs.

All items were translated into Chinese with modification by researchers and four MIS doctoral students who all had an average of five years of actual experience of system development. A pilot test was also conducted to ensure the language content was accessible.

3.3 Research Design

A multi-informant design was employed to measure social capital. As individual social capital is embedded in the relationship with other team members, it is unreasonable to gather data of social capital solely from an individual’s point of view. That is, social capital should be reported by both the individual and other team members. However, it is impractical to ask each respondent to report others’ social capital in a team of five or more members. To reduce the respondents’ task to a more manageable size, each respondent was asked to report the social capital of Sn randomly selected members

other than him. The number Sn is as follows to manage

the complexities: Sn is the greatest integer that is less

than or equal to 0.5Gn. Gn represents the size of the team.

For example, Sn is 3 in a team with seven members. This

design ensures that an individual’s social capital is evaluated by at least half of the other team members and he must also evaluate the social capital of at least half of the other team members.

In this design, we have to collect the lists of all members in each of the participating teams, and each questionnaire was tailored to include the random selection process. As an individual’s social capital was reported by several randomly selected team members, all members in a team had to participate in our study to gather sufficient data for each member’s social capital. If any one member did not participate, the data of the fellow members that they had been assigned to evaluate were discarded.

3.4 Data

Two hundred and fifty-nine students from 52 teams agreed to participate in our study through the mediation of course instructors and team leaders. To reassure respondents of confidentiality, all questionnaires were administered in the presence of a researcher or an assistant. Thus, each respondent’s evaluation about other team members’ social capital was not to be disclosed after completion of the questionnaire. Of the 259 students, 36 responses were discarded because of insufficient social capital data, missing values, or invalid responses. The remaining respondents (N = 223) were from 52 teams that ranged in size from three to seven people, with an average team size of 4.98 people (SD = 0.87). Sixty-five percent of the respondents were men and the average age was 21.6 years (SD = 1.27). Sixteen percent of the respondents were graduate students and 83.9 percent of the respondents were senior undergraduate students. With regard to task types, 54.7 percent of respondents were from courses with team homework or term projects and 45.3 percent of respondents were from courses with graduation projects. 4. Analyses and Results

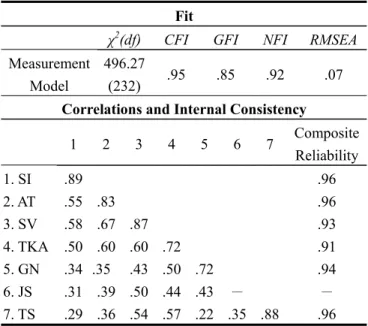

4.1 Measurement Model

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the operationalization. We modeled all the research constructs as seven correlated first-order factors. As Job Satisfaction was measured by a single item scale, the measurement error was constrained to zero. We used EQS for Windows 5.3 with the Maximum Likelihood estimation to estimate the measurement model. As shown in Table 1, the CFA results in a chi-square statistic of 496.27 with 232 degrees of freedom. As the chi-square is less than three times the degrees of freedom, a good fit is implied. Furthermore, the values on other goodness of fit indexes also show a relative good fit between measurement model and the data.

We also assessed construct reliability through calculation of composite reliability that assesses whether the specified indicators are sufficient in their representation of their respective latent factors. As Table 1 shows, these estimates of composite reliability range from .91 to .96. Also presented in Table 1 are the average variance extracted (AVE) estimates, which assess the

amount of variance captured by the construct’s measure relative to measurement error. The AVE estimate of .50 or higher indicates validity for a construct’s measure. All estimates are well above the cutoff value that suggests acceptable convergent validity. To assess discriminant validity among the constructs, we calculated the squared inter-construct correlations for each pair of constructs and compared them to the AVE estimate for each construct. As shown in Table 1, all AVE estimates for each construct are greater than the squared inter-construct correlations, which support discriminant validity.

Table 1. Measurement Model Results Fit

χ2(df) CFI GFI NFI RMSEA

Measurement Model

496.27

(232) .95 .85 .92 .07

Correlations and Internal Consistency

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Composite Reliability 1. SI .89 .96 2. AT .55 .83 .96 3. SV .58 .67 .87 .93 4. TKA .50 .60 .60 .72 .91 5. GN .34 .35 .43 .50 .72 .94 6. JS .31 .39 .50 .44 .43 - - 7. TS .29 .36 .54 .57 .22 .35 .88 .96

Note. 1. SI=Social Interaction; AT=Affect-based Trust; SV=Shared

Values; TKA=Tacit Knowledge Acquisition; GN=Growth Needs; JS=Job Satisfaction; TS=Team Satisfaction. 2. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct

was illustrated in the diagonal of correlation matrix.

4.2 Structural Model

Figure 1 also presents the structural model results with Maximum Likelihood estimation. The chi-square is less than three times the degrees of freedom and the values on all other fit indexes also show a relative good fit between the structural model and the data. With the exception of the Affect-based Trust to Team Satisfaction path, all hypothetical paths are statistically significant, and the percent of variation explained in endogenous constructs ranges from 22 percent to 48 percent.

The results indicate that seven of the eight hypothesized paths are significant. The hypothetical relationships among the three dimensions of social capital are supported. It indicates that Social Interaction

positively affects both Affect-based Trust and Shared Values. In addition, when team members hold Shared Values, Affect-based Trust is more likely to develop.

Hypotheses for the proposed effects of social capital are also presented in Figure 1. Both Affect-based Trust and Shared Values positively affect Tacit Knowledge Acquisition, as predicted in hypotheses 3 and 5. Furthermore, hypotheses 1 and 2 that predict the positive effects of Tacit Knowledge Acquisition on Job Satisfaction and Team Satisfaction are both supported. However, the path from Affect-based Trust to Team Satisfaction (hypothesis 4) is not significant. It is obvious that the relationship between Affect-based Trust and Team Satisfaction is mediated by Tacit Knowledge Acquisition.

4.3 Moderating Effects

We employed moderated hierarchical regression analysis to identify moderating effects without the result of information loss from the artificial transformation of a continuous variable into a qualitative one in the subgroup analyses (Szymanski, Troy, & Bharadwaj, 1995). This method is used to determine which of the following models is most appropriate: (a) Model 1: Y = b0 + b1X +

b2Z + b3XZ and (b) Model 2: Y = b0 + b1X + b2Z. Y is the

dependent variable, X is the independent variable, and Z is the moderator variable. To identify the best-fit and most parsimonious model, we examined the change in R squared from Model 1 to Model 2. If the difference is statistically significant, then (1) the interaction model (Model 1) is the best fitting model, and (2) post-hoc examination of the interaction effects is appropriate (Szymanski et al., 1995). A best fitting interaction model implies the moderating effect of variable Z.

In Table 2 we present the results of the moderating effects of growth needs. The items for each scale used in the moderated hierarchical regression analysis were averaged to produce a composite score for each respondent. With Tacit Knowledge Acquisition as the dependent variable, Affect-based Trust as the independent variable, and Growth Needs as the moderator, we found no significant change in R squared between Models 1 and 2 (as shown in Table 2, △R2 = .004, F ratio = 1.240, p >.1), which indicates that Growth Needs Strength does not moderate the relationship between Affect-based Trust and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition. Thus, hypothesis 9a is not supported.

For Shared Values, the result indicates a significant difference between Models 1 and 2 (as shown in Table 2,

△R2 = .015, F ratio = 5.009, p <.05). Thus, Model 1 is the more parsimonious model and indicates the moderating effect of Growth Needs on the relationship between Shared Values and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition.

To examine the form of the moderating effect, we plotted two slopes for each best-fitting regression equation -one at one standard deviation above the mean of Growth Needs and the second at one standard deviation below the mean. As shown in Figure 2, the graphical depiction is contrary to hypothesis 9b. It reveals that the relationship between Shared Values and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition is stronger among individuals that report low levels of Growth Needs than among individuals that report high levels of Growth Needs. To examine the differences in Tacit Knowledge Acquisition across Growth Needs levels for higher and lower Shared Values, 223 responses were divided into four groups according to the quartile of Shared Values and performed further regression analyses in both the highest and lowest groups. The results indicate that the relationship between Growth Needs and Tacit Knowledge Acquisition is significant only in the lowest Shared Values group.

Table 2. Hierarchical Regression Results Y = TKA; Z = GN X = AT β R2 △R2 F ratio for △R2 Model 1 AT 0.696*** GN 0.488*** AT×GN -0.352 .375 - - Model 2 AT 0.451*** GN 0.302*** .371 .004 1.240 X = SV Model 1 SV 1.059*** GN 0.986*** SV× GN -1.113** .355 - - Model 2 SV 0.423*** GN 0.279*** .340 .015 5.009**

Note. AT=Affect-based Trust; SV=Shared Values; TKA=Tacit

Knowledge Acquisition; GN=Growth Needs.

; SV=Shared Values; TKA=Tacit Knowledge Acquisition; GN=Growth Needs.

*: p<.1. **: p<.05. ***: p<.01. *: p<.1. **: p<.05. ***: p<.01.

We summarize all the research results in Table 3. Table 3. Summary of the Research Results

Hypotheses Results H1: TKA Æ TS Supported H2: TKA Æ JS Supported H3: AT Æ TKA Supported H4: AT Æ TS Not Supported H5: SV Æ TKA Supported H6: SV ÆAT Supported H7: SIÆ AT Supported H8: SI Æ SV Supported

H9a: ABT × GN Æ TKA Not Supported

H9b: SV × GN Æ TKA Not Supported

Note. SI=Social Interaction; AT=Affect-based Trust; SV=Shared

Values; TKA=Tacit Knowledge Acquisition; GN=Growth Needs; JS=Job Satisfaction; TS=Team Satisfaction.

5.8 5.5 5.2 4.9 4.6 4.3 4.00 0 0 0 0 0 0 -1SD 1SD Shared Values T ac it K now le dge A cq ui si tion Low GN High GN

a Low score = one standard deviation below the mean; high

score = one standard deviation above the mean.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Overall, the findings strongly support the claims that social capital is helpful in individual tacit knowledge acquisition, which leads to higher personal satisfaction toward a job and team members. Moreover, the results are partially contingent on individual growth needs. Affect-based trust and shared values have significant effects on tacit knowledge acquisition. This is consistent with Adler and Kwon’s (2002) arguments that the quality Figure 2. Moderating Effect of Growth Needsa

of social relationships provides the motivational source of social capital. With positive motivations, individuals are willing to share their tacit knowledge, which implies that tacit knowledge acquisition is easier as a result of good interpersonal relationships. We also found that tacit knowledge acquisition that is facilitated by social capital is positively related to individual satisfaction and the proposed relationships among three dimensions of social capital are clarified. When members in the same team frequently interact socially and hold similar values, they are willing to make considerable emotional investment in their relationships. Moreover, frequent social interaction between social actors facilitates the development of shared values and friendship. In short, strong social connections are prerequisites for a high quality of interpersonal relationships.

The results suggest that the development of social capital has two managerial implications. First, project managers need to foster the formation of an informal social network among team members to promote tacit knowledge sharing. Knowledge sharing is the most effective way to increase values of knowledge utilization, which enhances group competitiveness. Especially in a software project team, tacit knowledge sharing is critical for system success because individual team members rarely possess all the necessary skills and capabilities for software development, while most of the skills and capabilities are tacit in nature. Second, social capital that is rooted in an individual’s social network within a project team facilitates the acquisition of tacit knowledge and increases satisfaction. Higher satisfaction toward jobs and team members may lead to lower individual turnover intentions and higher organizational commitment that are critical for organizational functions. Thus, investment in the creation of social capital is an effective way to enhance a team member’s intrinsic motivation that also enhances team performance.

We are unable to confirm that affect-based trust serves to enhance individual satisfaction toward other team members. This finding is interesting as it contradicts our common intuitions about interpersonal friendship. We must be cautious in our interpretation of this result because more than half the respondents are from short-term project teams of semester courses. With short-term teamwork, individuals may be satisfied with the team’s cooperation even if they have not yet established close emotional ties with other members.

Friendship needs to be cultivated over a significant period of time. However, our analysis suggests that the relationship between affect-based trust and team satisfaction is mediated by tacit knowledge acquisition. That is, friendship facilitates tacit knowledge acquisition by increasing the belief that individuals can easily carry out their own jobs and satisfy the thirst for knowledge through mutual assistance that leads to higher satisfaction toward team members. For project managers, it is important to explain the significance of tacit knowledge sharing to all subordinates and provide certain mechanisms to facilitate tacit knowledge sharing among team members and to strengthen the effects of social capital. Individuals will not be satisfied with teamwork without tacit knowledge acquisition despite the existence of strong friendship.

In addition to the main effects, our results also indicate the moderating effects of growth needs. First, the relationship between affect-based trust and tacit knowledge acquisition is not moderated by individual growth needs. This result implies that friendship is also a prerequisite for effectiveness of tacit knowledge acquisition even though one’s growth needs are low. One possible interpretation is that individuals with low growth needs may tend to exchange tacit knowledge with their friends to achieve group objectives for a shared good, rather than self-development. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the relationship between shared values and tacit knowledge acquisition is stronger among individuals that report low levels of growth needs than among individuals that report high levels of growth needs. Further analyses show that growth needs are positively related to tacit knowledge acquisition among individuals whose values are less congruent to those of team members. This relationship is not significant between individuals whose values are highly congruent with those of team members. The results indicate that mutual understanding is an overwhelmingly facilitating factor for tacit knowledge acquisition, especially for individuals whose growth needs are low. For project managers, these results imply that the cultivation of common understanding and shared values among team members is fundamental for tacit knowledge sharing. Team members with highly congruent values tend to share and acquire tacit knowledge effectively. If shared values are not easily established, then individuals with high growth needs facilitate tacit knowledge sharing and acquisition within project teams.

The findings of this study demonstrate that each dimension of social capital facilitates the creation of other dimensions, which poses an interesting question: how is social capital derived and accumulated within project teams or organizations? This suggests that future research should attempt to identify factors, such as organizational attributes and individual characteristics, to enhance our understanding of the derivation and accumulation of social capital. Another area of future research involves the extension of this work to group or organizational levels. Later studies can explore the effects of collective social capital on knowledge sharing in organizational settings. Cross-level comparison may help further elaborate the relationship between social factors and knowledge sharing and acquisition within organizations.

Future research may be conducted with limitations of this study in mind. First, our results must be viewed in light of our limited student sample that may compromise its generalizability. Indeed, students that work in course assigned project teams are not comparable to personnel from professional software development teams in three aspects. (1) The project duration is usually longer for professional teams than for student teams. Thus, the social network development and interpersonal interaction will be different between the two types of software project teams. (2) The skills and knowledge that are involved in the professional teams are more advanced than in student teams. Professional team members may need more tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing to complete their tasks than student team members. (3) Members’ interpersonal and career pressures are vastly different and lead to different forms of social behavior that significantly affects knowledge sharing. Future studies could improve the generalizability of findings by conducting field research with personnel from business firms or nonprofit organizations. Second, our results are restricted to software project teams that are highly knowledge-intensive. The research questions should be further examined in other kinds of project teams to clarify our understanding about the effects of social capital. Third, the measures of the three dimensions of social capital were first applied in our studies. Other broader conceptualizations and possible measures of social capital should be proposed and examined, and an overall stronger measurement system for social capital would enhance research in the area.

References

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of

Management Review, 27(1), 17-40.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS

Quarterly, 25(1), 107-136.

Berman, S. L., Down, J., & Hill, C. W. L. (2002). Tacit knowledge as a source of competitive advantage in the national basketball association. Academy of

Management Journal, 45, 13-31.

Bolino, M. C., Turnley, W. H., & Bloodgood, J. M. (2002). Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 27, 505-522.

Brashear, T. G., Boles, J. S., Bellenger, D. N., & Brooks, C. M. (2003). An empirical test of trust-building processes and outcomes in sales manager-salesperson relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, 31(2), 189-200.

Choi, B., & Lee, H. (2003). An empirical investigation of KM styles and their effect on corporate performance.

Information & Management, 40, 403-417.

Ganzach, Y. (1998). Intelligence and job satisfaction.

Academy of Management Journal, 41(5), 526-539.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work design. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review.

Psychological Bulletin, 127, 376–407.

Käser, P. A. W., & Miles, R. E. (2002). Understanding knowledge activists’ successes and failures. Long

Range Planning, 35, 9-28.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning. Organization

Science, 7(5), 502-518.

Koskinen, K. U., Pihlanto, P., & Vanharanta, H. (2003). Tacit knowledge acquisition and sharing in a project work context. International Journal of Project

Management, 21, 281-290.

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2003). Social capital in multinational corporations and a micro-macro model of its formation. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 297-317.

Leana, C. R., & Van Buren, III, H. J. (1999). Organizational social capital and employment practices. Academy of Management Review, 24, 538-555.

Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a social reality.

Social Forces, 63(4), 967-985.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24-59.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing.

Journal of Marketing, 58, 20-38.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage.

Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organizational Science, 5(1), 14-37.

Osterloh, M., & Frey, B. S. (2000). Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms.

Organization Science, 11(5), 538-550.

Szymanski, D. M., Troy, L. C., & Bharadwaj, S. G. (1995). Order of entry and business performance: An empirical synthesis and reexamination. Journal of

Marketing, 59, 17-33.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of

Management Journal, 41(4), 464-476.

Van Der Vegt, G., Emans, B., & Van De Vliert, E. (2000). Team members’ affective responses to patterns of intragroup interdependence and job complexity.

Journal of Management, 26(4), 633-655.

Appendix

Social Interaction (adapted from McAllister, 1995; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998)

1. This person frequently initiates a chat with me. 2. I frequently initiate a chat with this person.

3. In general, I frequently interact with this person after classes.

Affect-based Trust (adapted from McAllister, 1995) 1. We have a sharing relationship. We can both freely

share our ideas, feelings, and hopes.

2. I can talk freely to this person about difficulties I am having at schoolwork and know that he will want to listen.

3. We would both feel a sense of loss if we could no longer work in the same team.

4. If I shared my problems with this person, I know he would respond constructively and caringly.

5. I would have to say that we have both made considerable emotional investments in our relationship.

Shared Values (adapted from Brashear et al., 2003)

1. I feel that my personal values are a good fit with those of this person (deleted).

2. This person has the same values as I have with regard to fairness about work assignment in our team. 3. This person has the same values as I have with regard

to goals of our team.

4. In general, my values and the values held by this person are very similar (deleted).

Tacit Knowledge Acquisition (adapted from Choi & Lee, 2003)

1. It is easy to get fact-to-face advice from other team members.

2. My knowledge can be easily acquired from other team members.

3. Informal dialogues and meetings are used for knowledge acquisition in this team.

4. Knowledge is acquired by one-to-one mentoring in this team.

Job Satisfaction (adapted from Ganzach, 1998)

1. In general, I am very satisfied with my task in this team

Team Satisfaction (adapted from Van Der Vegt et al., 2000)

1. I am satisfied with other team members.

2. I am pleased with the way other team members and I work together.

3. I am very satisfied with working in this team. Growth Needs (adapted from Hackman & Oldham, 1980) Each respondent was asked to indicate the degree to which one would like to have each characteristic present in his (her) assignment. The characteristics were …

1. Stimulating and challenging task.

2. Chances to exercise independent thought and action in my task.

4. Opportunities to be creative and imaginative in my task.

5. Opportunities for personal growth and development in my task.

6. A sense of worthwhile accomplishment in my task. Biographical Notes

Shu-Chen Yang is a doctoral student at the Department of Information Management of National Central University. He received an MBA in MIS from National Central University. His research interests include knowledge management, social capital, online marketing strategy, and supply chain management. He has published in Psychology & Marketing.

Cheng-Kiang Farn is a professor at the Department of Information Management of National Central University. He received his Ph.D. in management from UCLA. His research interests include e-Business, knowledge management, supply chain management, and cross cultural issues in the applications of IT. He has published in Information and Management, Psychology &

Marketing, Journal of Business Ethics, Computers in Human Behavior, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Journal of Government Information, The International Journal of Psychology, International Journal Production Research, International Journal of Production Research,