1

The Relationship of “Tax-Exemption” and “Community Benefit

Service” of Not-for-Profit Hospitals

Yi-Cheng Ho, Ph.D.

Professor,

Department of Public Finance, National Cheng-Chi University E-mail: yho@nccu.edu.tw

Jenn-Shyong Kuo, Ph.D.

Professor,

Department of Accounting, National Taipei University Email: jennkuo@mail.ntpu.edu.tw

Abstract

Purpose: the government often indirectly subsidizes nonprofit organizations by tax

benefit to encourage their engaging in community benefit service. This paper discusses the association between community benefit service expenditure and the tax exemption interest of not-for-profit hospitals in Taiwan. The findings of this paper can help understand the effect of tax benefit to encourage not-for-profit hospitals to engage in community benefit service.

Method: in this paper, we use the 2006-2010 data of 44 not-for-profit hospitals in

Taiwan to estimate panel data fixed effect model in the analysis of the association between the tax exemption interest and the expenditure of medical juridical persons (no-for-profit hospitals) on uncompensated care services and educational research activities or community benefit service with controlled hospital characteristics and environmental characteristics.

Results: regression results show that tax exemption interest has a negative

relationship with uncompensated care services spending, a positive relationship with and educational research and development spending, and no significant relationship with and community benefit service spending.

Conclusion: the public and authorities generally consider the main purpose of

granting not-for-profit hospitals tax benefit is to encourage medical social activities such as providing free medical care to healthcare have-nots rather than improve research momentum or educational quality, and educational research activities indirectly related to community benefit. Empirical results show that gaining tax exemption interest can make a positive contribution to not-for-profit hospitals in engaging in educational research activities, but is in a reverse relationship with uncompensated care services. Tax exemption interest and total expenditure of community benefit service are not significantly related possibly because the providing of community benefit service by the not-for-profit hospitals is mainly affected by other factors or the tax-free status has nothing to do with the providing of community benefit service.

2

Introduction

Not-for-profit hospitals play the role of complementing government functions in many countries through the provision of uncompensated care services. Many countries also generally encourage not-for-profit hospitals in the medical-related public service through tax benefit, that is, community benefit service. Tax benefit and community benefit service are two important characteristics of not-for-profit hospitals. In this paper, we discussed the association between the community benefit service and tax exemption interest of not-for-profit medical institutions (hospitals) in Taiwan.

To encourage not-for-profit hospitals to engage in the public social services, Taiwan’s government developed preferential provisions for not-for-profit hospitals in tax law (including business income tax, sales tax, land value tax, itemized deductions of

consolidated income tax). Article 46 of Medical Law (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2009) provides the obligations of not-for-profit hospitals, that is, the minimum level of the engagement of not-for-profit hospitals in community benefit service.

In recent years, the tax-exempt status of not-for-profit hospitals is controversial around the world (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466). Some public opinions in Taiwan also argue that earnings of not-for-profit hospitals should be contributed back to the society; in particular, some not-for-profit hospitals failing to provide community benefit service in accordance with Medical Law aroused the public conspicuous (Taiwan Healthcare Reform Foundation, 2009; Chiu, 2011; Yang, 2011). Controversies over the tax benefit of not-for-profit hospitals can be

summarized as follows: firstly, regarding the social functions of not-for-profit

hospitals, in prior times, not-for-profit hospitals obtained resources from donations or financing and provided families lacking in medical care services, playing the role of charitable organization. The majority of their patients were patients of poor healthcare (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324; Rushton, 2007: 662-675). In other words, not-for-profit hospitals provide free social services that can be provided by the government; therefore, the

government will provide not-for-profit hospitals with various subsidy policies such as tax benefit, rewards or subsidies as the indirect or direct incentives to hospitals to engage in charitable medical service (Sanders, 1995: 446-466). However, with the changing economic environment, social insurance based health insurance becomes

3

increasingly popular; the main service subjects of not-for-profit hospitals have expanded from those of poor healthcare to general public. The major source of funding hospitals has changed from donations to medical income of commercial activities. Therefore, the social role of not-for-profit hospitals has changed from the role of charity to the social and commercial role (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324).

Secondly, in economic theory, because the medical activities often have external interests and the characteristic of merit good, if left to the market mechanism to operate, there will be insufficient supply of society as a whole. Therefore, the

Government will promote the provision of medical activities through indirect or direct subsidies or tax relief. In addition, due to the information asymmetry between doctors and patients, not-for-profit hospitals do not aiming to maximize profits and the

remaining profits cannot be distributed to investors in the form of dividends. The remaining profits cannot be used in the operation of hospitals, and the patient-doctor relationship is relatively transparent. Therefore, they can provide higher medical service quality and the patients can be better protected. Moreover, it is legally provided that not-for-profit hospitals cannot distribute earnings and cannot issue securities and raise funds. Therefore, the fund-raising capabilities are not sufficient. However, tax benefit allow not-for-profit hospitals to accumulate more earnings for investment in equipment (Hansmann, 1981: 54-100). As mentioned above,

not-for-profit hospitals can reduce medical market’s information asymmetry and the agency relationship between donators and managers, resulting in market failure (Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324; Rushton, 2007: 662-675). However, as far as policy effects are concerned, the direct subsidies can better promote medical institutions to provide charitable medical service as compared to indirect tax reliefs (Sanders, 1995: 446-466; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324). In addition, tax benefit can provide not-for-profit hospitals with fewer charitable medical services to win competitive advantages, resulting in unfair competition of the medical care market to cause market inefficiency (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324).

4

nonprofit organizations, therefore, accounting records are not complete (Sanders, 1995: 446-466), and income cannot be accurately and reasonably used as the basis for taxation (Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324). However, with the advancement of medical technology, hospitals should configure expensive medical equipment. The income of not-for-profit hospitals mainly comes from the medical goods or services, and the operations tend to become commercial. Moreover, in recent years, accounting authorities and governments across the world have formulated the accounting

processing principles for nonprofit organizations and medical institutions, for example, the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board 116 and 117 journals (FASB, 1993) and Taiwan’s “Principles for the Preparation of Financial Reports of Medical Juridical Persons” (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2008). Therefore, the problem of inability to calculate taxation has ceased to exist (Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324).

Through the above descriptions of the tax exemption causes and changes in the environment of not-for-profit hospitals, we should rethink the policy objectives of not-for-profit hospitals tax benefit and whether tax relief policies can effectively encourage them to provide medical charity? Are tax exemption effects meeting expectations?

Regarding the effects of not-for-profit hospitals engaging in social work, the working effects are mainly measured by charitable medical care or free medical care. In recent years, medical social insurance covers a wider range, and the demand of medically poor on charitable health care reduces. The range of social work is further expanded to medical education and research, namely, the community benefit service in wide sense. Studies on the factors affecting not-for-profit hospitals to engage in community benefit activities can be divided into the following types: firstly, hospital features to discuss the impact of proving community benefit activities by hospitals, for example, physical capacity (for example, number of beds, the number of health care workers, etc.), wealth (for example, annual income, property, funds, etc.), fiscal capacity (for example, medical income, total income, etc.), medical service prices (for example, nurse average salary), being a teaching hospital and the establishment of emergency room etc. (Bryce, 2001: 24-39; Gaskin, 1997; Frank and Salkever, 1991: 430-445; Frank, Salkever and Mitchell, 1990; Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139; Kim, McCue, and

5

Thompson, 2009: 383-402); secondly, regarding market environmental characteristics, discussions are about the impact of lack of medical insurance on community benefit activities. Relevant studies often adopted the unemployment rate of residents, recurring income and the percentage of population aged above 65 years old in the areas of the not-for-profit hospitals (Rosko, 2004: 229-239; Gaskin, 1997; Frank, Salkever and Mitchell, 1990; Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139; Kim, McCue, and Thompson, 2009: 383-402); thirdly, regarding government policies and control, studies have explored the benefits of governmental uncompensated healthcare pool (Thorpe, 1988: 344-353; Gaskin, 1997; Spencer, 1998: 53-73) or tax-exemption status of not-for-profit hospitals (Clement, Smith, and Wheeler, 1994: 159-179; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324; O'Dnell and Martire, 2009; IHSP, 2012).

Regarding discussions on association between the not-for-profit hospitals’ tax-exempt status and the provision of community benefit service, there will be two analysis methods: 1) to directly compare the tax exemption interest derived from tax benefit and community benefit service expenditure amount of not-for-profit hospitals; 2) with controlled hospital characteristics and market characteristics, to analyze the existence of positive association between tax exemption interest and community benefit service spending. Community benefit service amount and types provided by not-for-profit hospitals will vary from its capacities and regional demands. Most of the past studies adopted the first way of analysis to compare tax exemption interest and providing community benefit service of not-for-profit hospitals across the country or specific states, for example, Clement, Smith and Wheeler (1994: 159-179), O'Donnell and Martire (2009) and IHSP (2012). According to authors, the second way of analysis is seldom at present. Therefore, by using Taiwan’s not-for-profit hospitals as examples, in this study, we compute tax benefit of tax exemption interests including business income tax, property tax and donation tax deduction etc. The community benefit activities can be divided into uncompensated care services expenditure

(uncompensated care services spending), educational research and development expenditure (education research spending) and community benefit service spending.

Currently, the world’s governments often use tax benefit to encourage not-for-profit hospitals to engage in community benefit service. Whether the measure of tax benefit

6

to encourage not-for-profit hospitals to engage in community benefit service can be a major basis for government policy and law amending is also one of the purposes of this study.

In this paper, we used the 2006-2010 panel data of 44 not-for-profit hospitals in Taiwan. We applied the fixed effect regression analysis to review the association between tax exemption interest and the provision of community benefit service expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals with controlled hospital characteristics and environmental characteristics. The article features include: firstly, this paper is the first article in Taiwan to estimate the derived tax expenditure of tax benefit to not-for-profit hospitals, namely, tax exemption interest enjoyed by not-for-profit hospitals. The amount of tax benefit include business income tax and land value tax, and donation deduction benefits, and the consideration of tax exemption is relatively complete; secondly, community benefit services include uncompensated care services expenditure and education research spending. In this paper, we used the annual cash expenditure rather than annual expenditure to measure the resources actually input in the community benefit services by not-for-profit hospitals; thirdly, in this paper, we also explored the association between tax exemption interest and community benefit service expenditure in the case of not-for-profit hospitals.

Research Method

1. Data Source

There are 55 not-for-profit hospitals in Taiwan. After deleting samples of closure (1 hospital), preparation (7 hospitals), and official operation period below three years (2 years) and incomplete financial reports (1 hospital), finally, we used the data of 44 not-for-profit hospitals during the five-year period from 2006 to 2010. After the elimination of missing values, unbalanced panel data of a total of 218 observations were used in this study. The financial data used in this study were taken from the financial reports of not-for-profit hospitals audited by accountants; tax interest data were calculated based on the financial reports of not-for-profit hospitals, medical resources management geographic information system of the Ministry of Health, not-for-profit hospitals’ cadastral transcripts (building transcripts), the announced premium and the progressive starting premium provided on the websites of relevant county and city governments, and the statistics of the financial taxation data center;

7

the regional (market) characteristic data were taken from National Statistics – county and city government statistics database and the statistics of medical institutions’ current status and medical service amount.

2. Variable Definitions 1) Dependent variable

To review the effect of the government to encourage not-for-profit hospitals to engage in community benefit service by tax benefit, we used the annual expenditure of the not-for-profit hospitals on community benefit services such as charitable health service. In practice, the range of community benefit service is very wide, and the generated values include the tangible and intangible benefits. No matter measuring the community benefit service from the definition perspective or the benefit perspective, it will be faced with many inherent limitations, and accurate calculation is not easy (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466). Hence, we used the available and quantifiable financial data for analysis and study. The definitions and items of the community benefit service of Taiwan’s medical juridical persons (hospitals) were developed in reference to the provisions of Article 46 of Medical Law (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2009) and Principles for the Preparation of Financial Reports of Medical Juridical Persons (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2008). 1

According to Article 46 of Medical Law (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2009), the community benefit service required by Ministry of Health for the not-for-profit hospitals include research and development, personnel training, health education and medical relief, community health services and other social services. The first three services are summarized in the accounting item of “education and research expenses” according to Principles for the Preparation of Financial Reports of Medical Juridical Persons; the last three services are summarized in the accounting item of

“uncompensated care services expenses”. In theory, education research expenses are for educational research and development activities relating to community benefit service. They refer to the training courses and research projects with the direct

1In Taiwan, not-for-profit hospitals (medical institutions) are usually established by medical juridical persons. Therefore, the two terms are exchangeable and alternatively used in this paper.

8

benefits to the community rather than for profit. The expenses are not for the

necessary training or salary of medical personnel of the hospitals or activities having a long term or indirect positive impact on the community. However, in practice, such educational research and development activities directly related to community benefit (Article 46, Medical Law) are often confused with the research and development and talent training activities of teaching hospitals (Article 97, Medical Law). As a result, the expenses for the activities of the teaching hospitals are often included in the education research expenses for community benefit service; 2 secondly,

uncompensated care services activities, in theory, refer to the necessary medical service to people with poor medical resources, for example, making up for the lack of medical aid, and the prevention and control of infectious diseases (Kuo et al., 2006: 440-448; Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139). In this paper, we believe that uncompensated care services activities are closer to community benefit service in concept and the correlation is more direct.

In this paper, the expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals on community benefit service can be divided into three annual cash expenditure amounts including the

“uncompensated care services spending”, “education research spending” and the addition of the above two items, and the “community benefit service spending”. Although, Article 46, Medical Law 46 allows not-for-profit hospitals to recognize on an accrual basis for expenses relating to community benefit service, the annual expenses are not necessarily equal to the actual annual expenditure amount. The public expect the not-for-profit hospitals to regularly, routinely and actually participate in uncompensated care services activities and educational research activities. Most of related mechanisms of foreign countries also measure the level of the community benefit service of not-for-profit hospitals by actual cash spending.

2) Independent variable

independent variables can be divided into three major categories including the variables of hospitals tax exemption interest, variables of hospitals characteristics

2

Article 97, Medical Law (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2009) provides: 1. Teaching hospitals should budget for research and development and talent training annually, and the percentage of the budget against the annual total medical income should not be below 3%.

9

(total income, debt ratio, prior net interest rate) and regional characteristic variables (unemployment rate, market concentration).

(1). Hospitals tax exemption interest variables

governments generally encourage not-for-profit hospitals to carry out charitable medical service by subsidies such as tax reduction and exemption to provide free medical service to people lacking in medical resources, making up for the

governmental or market functions (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Sanders, 1995: 446-466; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324; Rushton, 2007: 662-675). Briefly speaking, the proactive purpose of the government providing tax benefit to nonprofit hospitals is to provide them with momentum for charitable medical service. Therefore, as far as policy purpose is concerned, an effective policy of tax incentive should be able to encourage hospitals to generate positive impact on community benefit service expenditure by enjoying tax exemption interest. With Texas of the United States as an example, Texas Health and Safety Code (1995) proposes four criteria for the amount of not-for-profit hospitals engaging in charitable medical service and community benefit service. One criterion is that community benefit service expenditure should be more than the tax exemption interest (including income tax, franchise tax, sales tax and consumption tax etc.) (Bryce, 2001: 24-39). This suggests hospitals enjoy more tax exemption interests as regarded by the public and the community should provide more community benefit service. Based on the above analysis, we believe, with reasonable policies of tax benefit, tax exemption interest and community benefit service expenditure should be positively correlated to a considerable degree.

According to Taiwan’s tax law, tax benefit of not-for-profit hospitals include business income tax, sales tax, land value tax, property tax and donation deductions. Since all hospitals, clinics and nursing homes are exempted from sales tax and thus the incentive is not exclusively for not-for-profit hospitals, it is eliminated in the estimation of the tax exemption interest of not-for-profit hospitals. Moreover,

Property Tax Ordinance (Ministry of Finance, 2007) provides that only charitable and relief organizations and businesses are exempted subject to the decision of local government. The handling varied from local governments during the data period. At present, only a few affiliated hospitals established by religious juridical persons enjoy the status of tax exemption of property tax. Such hospitals were not considered in this

10

paper as well. 3 Therefore, in this study, the tax exemption interests as tax benefit to

not-for-profit hospitals include business income tax exemption, land value tax exemption and donation deductions.

In this study, we estimated the tax exemption interests of the not-for-profit hospitals due to the tax-exempt status by computing the potential tax burden (Clement et al., 1994: 159-179; Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324), that is, the tax not-for-profit hospitals or donor should pay if having no tax benefit. Relevant source of law and computation methods of the tax benefit are elaborated as follows: firstly, in the respect of business income tax, the source of law for tax exemption is the 13th

subparagraph, 1st paragraph of Article 4 of the Income Tax Law (Ministry of Finance,

2011). 4 Such as tax exemption interest is a permanent difference in accounting. The

income tax expenses (benefits) represent adjusted permanent difference in financial reports without adjusting the temporary difference’s tax. The multiplication of the current surplus or deficit of the financial report and the current tax rate is the

unadjusted permanent and temporary differences’ tax burden (hereinafter referred to unadjusted differences’ tax burden). Therefore, by subtracting income tax expenses (benefits) and the tax amount with adjusting differences, if the annual tax rate is unchanged and the permanent differences come only from the income tax reductions, we can get the tax implied by the permanent differences, that is, the tax exemption benefit of business income tax of not-for-profit hospitals. If not-for-profit hospitals are at a loss and the tax exemption interests are negative, then tax exemption interest is zero. The business income tax was 25% in 2006 to 2009 and was reduced to 17% in 2010.

Secondly, in the respect of land value tax, the legal source of exemption from land

3The 2nd subparagraph, 1st paragraph of Article 15 of the Property Tax Ordinance (Ministry of Finance, 2007)provides: “for a registered private charitable and relief organization, if not for the purpose of making a profit, upon the completion of the registration of juridical person, the houses for the sole direct use of the business of the organization should be exempted from property tax.”

4The13th subparagraph, 1st paragraph of Article 4 of the Income Tax Law (Ministry of Finance, 2011)provides: “the educational, cultural, public welfare and charitable institutions or organizations in line with the criteria provided by the Executive Yuan should be exempted from income tax on their income and the income of their affiliates.”

11

value tax is the provision of the fifth subparagraph, the first paragraph of Article 8 of Land value tax Exemption Rules (Ministry of Finance, 2010). 5 The qualifications

for tax exemption can be summarized into two points: 1) the land should be held by not-for-profit hospitals; 2) the land is used for medical cause. In this study, when calculating tax exemption interest, we inquired the addresses of medical institutions and organizations owned by not-for-profit hospitals from the “Ministry of Health Medical Resources Management Geographic Information System” and applied to Land Office for cadastral transcripts (building transcripts) to get information

including the land plot number, building coverage area, building use, building owner and property right registration date. We first calculated the area covered by the buildings owned by not-for-profit hospitals for medical use (square meter). By multiplying the unit medical land area with the announced land price of the county or city (NTD/square meter), we can get the total land price of the not-for-profit hospital. After accommodations, based on the progressive starting price of the land as

announced by the local tax collection authority, we can compute the multiple

relationships of the total land price and the progressive starting land price to input into the tax rate equation to get the land value tax exemption interest.

Finally, regarding donation deductions, after making donations to not-for-profit hospitals, the donator can enjoy the deduction from the taxable income to a certain degree, therefore, donation deduction is also one of the expenditure of tax-exempt status of not-for-profit hospitals given by the government (Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324). The donation-generated tax exemption interest is the multiplication of the donation deduction with the applicable income tax marginal tax rate (Gentry and Penrod, 2000: 285-324). Firstly, in the respect of legal source: the donation income of

5(Ministry of Finance, 2010) the fifth subparagraph, the first paragraph of Article 8 of Land value tax Exemption Rules provides: “private hospitals, blood donation organization, charities and other nonprofit causes established with the approval of the competent authorities to promote the public interest not for the interest of the same industry, classmates, clan members or other specified people are exempted from the land value tax for the land specifically for the causes. However, to promote the causes for the public interest, except those approved by the Municipality, County (City) competent authorities upon the application of the local tax collection authorities, such an organization or cause should be a registered juridical person or established by a juridical person, and the land exempted from tax should be owned by the juridical person.”

12

not-for-profit hospitals may come from natural persons or juridical persons. For natural persons, tax benefit comes from the provisions of the first sub- item, the second item, the first Paragraph of Article 17 of the Income Tax Law (Ministry of Finance, 2011), the donation made by the natural person to not-for-profit hospitals is one of the deduction items listed in the Comprehensive Income Tax Law; 6 for

juridical persons, according to the fourth paragraph of Article 11 of the Income Tax Law (Ministry of Finance, 2011), the donations of juridical persons made to the organizations of public interest and foundations (not-for-profit hospitals) can be listed as the annual expenses or losses, and thus income tax burden will be reduced. 7

Secondly, tax exemption interest determines the income tax rate applicable to the donation amount and donor: due to limit of data type, we cannot know the donation amount of the natural person and the juridical person, and the income tax marginal tax rate applicable to the natural person. Therefore, after computing tax benefit of

donation reduction, with not-for-profit hospitals as the units for computation, we multiplied the donation income of not-for-profit hospitals with the average tax rate of the year (including comprehensive income tax and business income tax) in the

estimation of tax benefit of donation reduction. The data of average income tax rate of the year came from the Financial and Fiscal Data Center. The average income tax rate was 18.33%, 18.66%, 18.09%, 18.51% and 15.14% respectively in 2006 to 2009.

The tax exemption interests derived from the above three tax benefit are tax exemption interests of not-for-profit hospitals against other private medical institutions, namely, the government allows not-for-profit hospitals to have

tax-exempt status spending. Where, business income and land value tax exemption interest can be directly attributed to not-for-profit hospitals; regarding the tax exemption interest of donation deductions, it can be indirectly attributed to

6Section 1 of the 2nd item, the first paragraph of Article 17 of the Income Tax Law(Ministry of Finance, 2011): “deductions: 1. donations: the amount of donation of any taxpayer or his or her spouse and supported family member to educational, cultural, public interest, charitable organization or groups should not exceed 20% of the comprehensive income.”

7The 2nd Subparagraph, the first subparagraph, of Article 36 of the Income Tax Law (Ministry of Finance, 2011) “II. In addition to the donations provided in the preceding clause, the donation to any institution or group as provided in the fourth paragraph of Article 11 should not exceed 10% of the total income.”

13

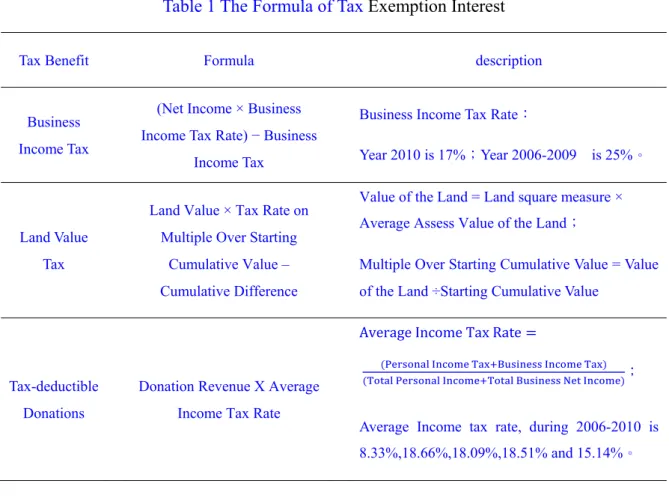

not-for-profit hospitals through donors. The computation of the relevant tax exemption interest is listed as shown in Table 1.

In sensitivity analysis, to increase the tax exemption interest of sales tax, we

established three proxy variables for tax benefits according to the direct attribution of tax exemption interest to not-for-profit hospitals: 1) tax exemption interest 2, tax exemption interest of all tax benefit. Besides the above mentioned business income tax, land value tax and donation deductions, we added the sales tax exemption interest; 2) tax exemption interest 3, we calculated the tax exemption interest that can be

directly attributed to not-for-profit hospitals, namely, tax exemption interest includes the tax benefit of sales tax, business income tax and land value tax; 3) tax exemption interest 4, tax benefit of not-for-profit hospitals that are not applicable to other private medical institutions. That is the added tax exemption interest of business income tax and land value tax. We elaborated on the legal source and computation method of sales tax exemption in sensitivity analysis.

(2) Variables of hospitals characteristics

Variables of hospitals characteristics can be categorized into variables of hospital capacity and debt structure. Firstly, in the capacity of hospitals, variables can be divided into the variables of the fiscal capacity and the physical capacity. Most studies have found that higher capacity of not-for-profit hospitals can lead to stronger

capability of providing community benefit service (Frank and Salkever, 1991: 430-445; Bryce, 2001: 24-39; Rosko, 2004: 229-239; Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139). However, some studies also suggest that they are significantly and negatively correlated (Rosko, 2002: 352-379; Magnus, 2004: 46-58) or not significantly

correlated (Frank, Salkever, and Mitchell, 1990: 159-183). The variables of physical capacity used in past studies include number of beds, total number of full-time

employees or number of employees per bed. The proxy variables of the fiscal capacity include medical income or net medical income (Bryce, 2001: 24-39). Where, number of beds is most commonly used as the physical capacity indicator of hospitals. However, as samples of this study include medical inspection centers (for example: cancer prevention inspection center, etc.), number of beds or number of medical staffs are not appropriate variables to measure the capacity of hospitals. In this study, we

14

used total income and prior net interest rate as the proxy variables of the capacity of the not-for-profit hospitals. Relevant explanations are as follows: (a). total income: total income is the addition of the total medical income and the income of

non-medical activities. As the total income is always positive and far greater than zero, we used the natural logarithm of total income in regression. The regression coefficient of the variable of total income is expected to be positive in this paper. In sensitivity analysis, we used total medical income and net medical income as the proxy variables; (b). Prior net profit rate: net profit measures the financial earnings of the operations of the medical institutions. On the premise that not-for-profit hospitals are engaged in the medical service for the public interest, it can be inferred that community benefit service can make positive contribution to not-for-profit hospitals. According to the income effect theory, it can be inferred that higher financial earnings level of the not-for-profit hospitals can result in more capacity and willingness to provide community service activities. The two are expected to have positive correlation, and thus, the effect is positive. Although the dependent variables of the regression analysis of this study are educational research and development expenditure and

uncompensated care services spending, educational research and development expenses and uncompensated care services expenses are parts of medical costs. To reduce the possible internality, this study used the prior net profit rate (the percent of prior period surplus or deficit against the total net medical income) to measure the financial earnings of the medical institutions (profitability), and the regression coefficient is expected to be positive. Secondly, in the debt structure respect, this study used the debt ratio to measure the degree. Debt ratio: the measurement of the financial leverage and solvency of medical institutions. To avoid high debt to cause high risk of insolvency, not-for-profit hospitals will pay off interest and due debt by earnings in priority, and thus crowding out the resources of community benefit service for free medical service. In other words, debt has a negative impact on community service activities (Magnus et al., 2003: 7-17; Kuo et al., 2006: 440-448; Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139; Kim, McCue, and Thompson, 2009: 383-402). In this paper, the debt ratio is measured by the division of total debt by total assets, and it is expected that debt ratio and community benefit service expenditure have a negative relationship. (3). Regional characteristic variables

15

not-for-profit hospitals will provide more community service activities on the premise that the principles of the operations of not-for-profit hospitals are altruistic. Indicators to measure the residents’ demand on community benefit service include

unemployment rate, regular household income and medical market concentration. The measurement of unemployment rate and medical market concentration can be

illustrated as follows: firstly, unemployment rate: for the unemployed, in addition to the impact of loss of fixed income on the capability of paying off medical expenses, they also lack in medical insurance provided by the employer. Therefore, it is

expected that residents of areas of higher unemployment rate have higher demand on free medical service. Past literature pointed out unemployment rate has a significant and positive impact on free medical service expenditure (Rosko, 2002: 352-379, 2004: 229-239; Magnus et al., 2004: 46-58); some other studies suggested that the two are not significantly correlated (Kuo et al., 2006: 440-448). In sensitivity analysis, we used the average household regular income or average household disposable income as the proxy variables. It is noteworthy, after the implementation of the health care insurance in Taiwan, the insurance coverage has expanded to cover the low income people and the unemployed who were insufficient in terms of medical insurance to substantially reduce the demand on free medical service; secondly, medical market concentration (HHI): if the medical industry’s market concentration is higher, medical institutions of monopoly power can make monopoly profit through the force of the market. In this case, they have more resources to engage in community benefit service; on the contrary, when the medical market concentration level is lower, the

competition among medical institutions will be higher, and the profits of medical institutions will be reduced to lower community benefit service spending. Therefore, it is expected that market concentration and community benefit service expenditure have a positive correlation. Past empirical studies have pointed out that HHI and free medical service are positively correlated (Rosko, 2004: 229-239), or HHI and free medical service are not significantly correlated (Frank and Salkever, 1991: 430-445). However, some studies suggested that HHI and community benefit service

expenditure were significantly and negatively correlated (Kuo and Ho, 2007: 128-139). In this study, we used Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) to compute market concentration by adding up the square of the number of beds of the individual medical institutions against the total number of beds of the medical institutions. HHI

16

is between 0 and 1, when HHI is closer to 1, the concentration of the beds in the medical region is higher, and the monopoly of the medical institution is higher; on the contrary, when HHI is closer to 0, the competition of the medical institutions in the medical region is higher.

3) Empirical model

Based on the above illustrations and variable definitions, the empirical model can be written as the following:

where, i is the not-for-profit hospital (i = 1, 2,..., 44). t is the year (t= 95, 96,.., 99). Dependent variable yitj is the expenditure of No. i not-for-profit hospital No. t year on

No. j community benefit service, yitj are uncompensated care services expenditure,

education research expenditure and community benefit service expenditure

respectively. Regarding independent variables, tax bntit is tax exemption interest. In

this study, the tax benefits include the addition of profit business income tax, land value tax and donation deduction (tax exemption interest 一); hospital financial characteristic variables include total income (tr), debt ratio (db_rt) and prior net interest rate (lgebt_rt); market characteristic variables include local unemployment rate (ue_rt) and market concentration (hhi). The data used in the empirical analysis of this study are the unbalanced panel data. To ensure the consistency and freedom from biasedness of the regression coefficient, we used fixed effect model for regression analysis to control the characteristics of the not-for-profit hospitals that cannot be observed and change over time.

4) Summary of statistics

Table 2 illustrates the descriptive statistics of relevant variables of 44 not-for-profit hospitals in 2006-2010. Where, the 2006 year data of two hospitals were absent, we used a total of 218 observations of the samples. Firstly, regarding the expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals on community benefit service, the average annual expenditure on uncompensated care services is 45.6 million NTD, the average annual expenditure on education research is 111.3 million NTD, and the average annual expenditure on

17

overall community benefit service is 156.9 million NTD. Education research expenditure accounts for about 70% of the overall community service spending. In addition, the standard deviations of the expenditure on three community benefit services are greater than the average value, suggesting that the differences of not-for-profit hospitals in community service activities are great; secondly, the average annual value of tax exemption interest of not-for-profit hospitals from tax benefit is 130.8 million NTD, being higher than uncompensated care services expenditure or education research expenditure and slightly lower than community benefit service spending. It is noteworthy that the maximum value of tax exemption interest is 0, suggesting some not-for-profit hospitals do not enjoy tax exemption interest from tax exemption. It may be because of the concurrence of operational losses, medical land not in line with the land value tax exemption conditions or lack of donation income. Table 3 illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficient,

independent variables with highest correlation coefficient are tax benefit and prior net interest rate at 0.4132, the correlation coefficients among other independent variables are lower than 0.41, suggesting that the collinearity of independent variables is not serious.

Experimental Results

1. Regression analysis results

In this study, we applied the panel data fixed effect model in regression analysis by using uncompensated care services expenditure, education research expenditure or community benefit service expenditure as dependent variables to conduct the regression analysis of the tax exemption benefit and medical institutions

characteristics and regional characteristic variables. Tax exemption interest consists of the tax benefit of business income tax, land value tax and donation deductions. In this paper, we used the pooled-data model and panel data model in analysis before

applying the long term panel data to estimate the fixed effect model and random effect model. In addition, by establishing the cluster of not-for-profit hospitals to control the appearance of the same hospital in different years may result in the non-independent effect to underestimate standard deviation of regression coefficient (Petersen, 2009: 435-480). The regression analysis results are as shown in Table 4.

18

random model. In this paper, we adopted the artificial regression approach (Arellano, 1993: 87-97; Wooldridge, 2002: 290-291) to test the null hypothesis that it is unable to observe the externality of the effect of specific not-for-profit hospitals. The regressions of Sargan-Hansen statistics (following X2 distribution) in uncompensated

care services expenditure, education research expenditure and community benefit activities expenditure are 330.30, 192.43 and 265.04 respectively, and the three regression equations reject the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level. That is, the fixed effect model is relatively reasonable; secondly, in the comparison of the fixed effect model and pooled-data model, we adopted F-test to test the null

hypothesis that the specific effect of all not-for-profit hospitals is zero. As shown in Table 4, the F statistics in uncompensated care services spending, education research expenditure and community benefit service expenditure are 43.77, 28.34 and 50.49 respectively, and three regression equations reject the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, that is, the estimation results of the fixed effect model are better. Accordingly, in this study, we only listed the results of the panel data fixed effect model.

19

Regarding the tax exemption interest of not-for-profit hospitals from tax benefit, firstly, the regression coefficient of uncompensated care services expenditure and tax exemption interest (standard deviation) is -0.0534 (0.0023), and, at 1% significance level, it supports that tax exemption interest and uncompensated care services

expenditure are reversely correlated. Namely, for the gain of each NTD tax exemption interest, the uncompensated care services expenditure of not-for-profit hospital will reduce by 0.0534 NTD. The regression coefficient of tax exemption interest is opposite to the expectations of this study, suggesting the inconsistency with the expectations of the public and the government in offering the not-for-profit hospitals with tax exemption benefits; secondly, regarding the education research expenditure regression, tax exemption interest regression coefficient (standard deviation) is 0.0419 (0.0183), and supports at 5% significance level the positive correlation of tax

exemption interest and education research spending. This suggests that gain of each 1 NTD of tax exemption interest can result in the increase in education research

expenditure of NTD 0.0419; thirdly, regarding the regression of community benefit service spending, tax exemption interest regression coefficient (standard deviation) is -0.0115 (0.0189), which is not consistent with the expectations of the public. However, it cannot reject the null hypothesis at 10% level that regression coefficient is zero, suggesting that there is no significant linear relationship between tax exemption interest and community benefit service spending. This is possibly caused by the fact that the qualifications to enjoy the tax-exemption status and community benefit service of the not-for-profit hospitals are not correlated. Regarding the total community benefit service expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals, it can be

determined by the factors other than tax exemption interest, or the amount is fixed.

Concerning characteristics variables, firstly, regression coefficients of the total income in three regression equations are positive. Moreover, in the regression

equation of uncompensated care services expenditure and community benefit service spending, at 10% significance level, it supports that total income and uncompensated care services expenditure and community benefit service expenditure are positively correlated as inferred in this paper. This suggests more total income of not-for-profit hospitals can result in greater fiscal capacity. Although it has no significant impact on education research spending, it can significantly increase uncompensated care

20

services expenditure and community benefit service spending, which are the same with the previous empirical results (Frank and Salkever, 1991: 430-445; Bryce, 2001: 24-39; Rosko, 2004: 229-239; Kuo et al., 2006: 440-448). Fiscal capacity has more significant impact on uncompensated care services spending, education research expenditure and hospital capacity are not significantly correlated. Secondly,

regression coefficients of the prior net interest rate in three regression equations are negative; it reaches 5% significance level in terms of community benefit service spending, which is not consistent with conclusions of this research. The empirical study results suggest that higher prior net interest rate can result in better profitability and the community benefit service expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals will reduce. This is the same with the findings of Frank and Salkever (1991: 430-445) and Kuo et al.(2006: 440-448); thirdly, the regression coefficients of debt ratio in regression equations are negative, which are consistent with the inferences of this study. However, the three regression equations cannot reject the null hypothesis that debt ratio regression coefficient is zero at 10% significance level. The results are the same with the findings of Kuo et al. (2006: 440-448).

Regarding regional characteristic variables, firstly, regression coefficients of unemployment rate in the three regression equations are positive. However, they cannot at 10 % significance level the null hypothesis that regression coefficient is zero. The empirical results suggest that local unemployment rate has no impact on

not-for-profit hospitals in terms of uncompensated care services, education research or community benefit service resources. This is possibly because the health insurance implemented in Taiwan covers the people originally lacking in medical insurance; secondly, the regression coefficient of the medical market concentration (HHI) in regression equation in terms of uncompensated care services expenditure is positive as expected. It rejects the null hypothesis that regression coefficient is zero at 5% significance level. This suggests that higher market concentration of the not-for-profit hospitals can result in higher monopoly profits of medical institutions. Not-for-profit hospitals have more resources in uncompensated care services spending, which is consistent with findings by Rosko (2004: 229-239). Regarding the regression

equations of education research expenditure and community benefit service spending, regression coefficient of the medical market concentration cannot reject the null

21

hypothesis that coefficient is zero at 10% significance level.

2. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the validity of empirical results, we also conducted sensitivity analysis. Firstly, in the respect of the cover range of tax exemption interest, we defined the tax exemption benefits from two perspectives, one is to increase the tax exemption interest of sales tax, and the other is whether the tax reduction benefit can be directly attributed to not-for-profit hospitals.

According to the provisions of the third subparagraph, the first paragraph of Article 8 of the value-added and non-value-added sales tax law (hereinafter referred to as sales tax law), medical institutions are exempted from sales tax on medical service,

medicine, patient accommodation and food. 8 Although the tax incentive is for all

private medical institutions, not-for-profit hospitals are also entitled to the tax benefit, which is also a part of tax spending. When calculating the potential tax burden, we assumed that the medical service and goods provided by not-for-profit hospitals are taxable. The benefit of sales tax exemption is the multiplication of net medical income with the current sales tax rate (5%).

Regarding the attribution of tax exemption interest, sales tax, business income tax and land value tax exemption interests can be directly attributed to not-for-profit hospitals. The donation deduction tax exemption interest is directly attributed to the donor to allow the not-for-profit hospitals to get the donation income indirectly. According to the classification of the above two dimensions, we proposed three proxy variables of tax exemption interest: 1) tax exemption interest 2: tax benefit include the exemption of sales tax, business income tax, land value tax and donation deduction; 2) tax

exemption interest 2: tax benefit include sales tax, business income tax, land value tax; 3) tax exemption interest 4: tax benefit include business income tax, land value tax. The regression equations of tax exemption interest and uncompensated care services

8According to the provisions of the third subparagraph, the first paragraph of Article 8 of the value-added and non-value-added business tax law (Ministry of Finance, 2011):““cording to the provisions of the third subparagraph, the first paragraph of, medicine, patient accommodation and food.”

22

spending, education research expenditure and community benefit service expenditure are as shown in Table 5. To save space, we listed only the regression coefficients of tax exemption interest. According to Table 5, the tax exemption interest regression coefficients are the same with those as shown in Table 4. The regression coefficient of the regression equation of uncompensated care services expenditure is significantly negative. The regression coefficient of the regression equation of the education research expenditure is significantly positive. In the case of community benefit service spending, it cannot reject the null hypothesis that the coefficient is zero at 10% significance level. Other control variables with regression coefficient up to the 10% significance level are all the same with the results as shown in Table 4.

Secondly, regarding the function types of regression equations, this study also considered the non-linear relationships in between benefit and uncompensated care services spending, education research expenditure and community benefit service spending. Therefore, we added in the three regression equations the second order item of tax exemption interest to check the existence of the second order relationship between the tax exemption interest and community benefit activities spending. The empirical results of the panel data fixed effect model show that the first order items of three regression equations in terms of the tax exemption interest are the same with those as shown in Table 4. The regression coefficients of the second order items of the tax exemption interest are all positive. However, neither the second order items nor the first order items of tax exemption interest can reject the null hypothesis that coefficient is zero at 10% significance level.

Thirdly, regarding the measurement of other control variables, we attempted to use different proxy variables. Firstly, regarding the capacity of the medical institutions, we used total medical income and total net medical income to replace total income in the measurement of the capacity of not-for-profit hospitals; secondly, for regional characteristic variables, we used the household regular income and household disposable income to replace unemployment rate to measure the community demand on community benefit service. We used different control variables in estimation, and the results are the same with those as shown in Table 4.

23

In summary of the above regression results and sensitivity analysis, we believed that tax exemption interest from tax-exempt status and uncompensated care services expenditure are in a reverse relationship. This suggests that the tax benefit of the government for not-for-profit hospitals have not increased the uncompensated care services spending, instead, the expenditure has been decreased. This is contrary to the expectation of the public. In addition, tax exemption interest and education research expenditure are positively correlated as expected. However, education research expenditure is mainly to achieve the standardization of teaching hospitals by Ministry of Health, and the community has not been directly benefited. It is a community benefit service in broad sense. Finally, tax exemption interest and community benefit service expenditure have no significant relationship. The total amount of the

community benefit service expenditure of not-for-profit hospitals may be affected by factors other than tax exemption interest.

Conclusion and Suggestions

In this paper, we explored the association of the tax exemption interest and

community benefit services such as the uncompensated care services in the case of Taiwan’s not-for-profit hospitals. Community benefit service such as uncompensated care services is of public goods by nature. The government often indirectly subsidizes the community benefit service by tax benefit to make up for the government failure and market failure. Traditionally, not-for-profit hospitals mainly provide charitable medical services to people of poor healthcare. In recent years, as the coverage of social medical insurance expands, the function of not-for-profit hospitals to provide charitable medical service has been gradually taken place. Therefore, the range of the community benefit service becomes increasingly wider: community health building, public hygiene and medical and health knowledge promotion, etc.

In this study, we used the 2006-2010 non-panel data of 44 not-for-profit hospitals in Taiwan for analysis. According to the statistical survey, on average, education research expenditure accounts for more than 70% of community benefit service spending, suggesting that not-for-profit hospitals tend to invest in educational research activities. The regression analysis results by using the fixed effect model

24

suggest that tax exemption interest and education research expenditure are

significantly and positively correlated while the relationship between tax exemption interest and uncompensated care services expenditure is significantly negative. The regression coefficients of the two regression equations in the case of tax exemption interest are close. This may be caused by the fact that uncompensated care services expenditure is for free activities. Although such activities can help improve the reputation of the hospital, it will reduce operating earnings and thus is not conducive to the survival in the medical market. The education research expenditure is an investment by nature. For example, investment in human resources investment, equipment and apparatus can help improve medical service quality and operation of the hospital. Therefore, not-for-profit hospitals tend to invest more resources in educational research activities, and reduce uncompensated care services activities spending. In addition, regression results show that tax exemption interest and

community benefit service expenditure have no significant correlation. This is maybe caused by the fact that the legally recognized qualifications to enjoy tax benefit of the not-for-profit hospitals are not based on community benefit service but the juridical person characteristics and the percentage of expenditure against revenue (70%) or community benefit service expenditure is affected by other factors; or total

expenditure amount is fixed. The regression results of uncompensated care services expenditure and community benefit service expenditure are not consistent with the purpose of providing tax benefit to for-profit hospitals tax benefit to encourage them to engage in uncompensated care services activities. Although the regression results of the educational research activities expenditure are consistent with expectation, the contribution of educational research activities to community health is indirect and thus it is a community benefit service in broad sense.

According to the analysis of the community benefit service items and the empirical results of this study, we proposed the following suggestions on the law and regulation of community benefit service: first, the tax free status should be determined by amount of service instead of organization identity. At present, Taiwan’s tax law recognizes the tax free status of not-for-profit hospitals by identity and the percentage of expenditure against revenue. It may lead to the lack of significant and positive correlation between tax exemption interest and community benefit service. We

25

proposed to use the business amount of the community benefit service of the medical institutions as the basis for the recognition of tax free status. In this way, it can strengthen the incentives to not-for-profit hospitals to engage in uncompensated care services activities, and expand the range of the medical institutions providing

community benefit service to profit-making medical institutions. Second, we

proposed to redefine the range and level of community benefit service: At present, the range of the community benefit service as listed in Article 46 of the Medical Law 46 is very wide. Not all the items are in line with the connotations of the community benefit service. We classified the items into the following two types as illustrated below: the first category is the uncompensated care services activities including medical relief, community medical service and other social services. The service items can be illustrated according to No. 30-1 of the Measures for the Implementation of the Medical Law. 9 (1). To provide expenses relating to the medical service,

transportation, auxiliary equipment, care and rehabilitation for the poor family, the underprivileged family or homeless patients, which is the charitable medical service to medically deprived people by nature. It is the free medical service traditionally important to not-for-profit hospitals, and is of public goods by nature. Regarding medical services of (2). community medical healthcare, health promotion and community feedback etc., they are medical services of community public health and the promotion of hygienic knowledge to help improve the health quality of

community residents, and thus having externality. Regarding (3). Convenience services and the implementation of the international medical help in cooperation with government policy, compared with the above said charitable medical service and public health medical service, they are extended service items and in the broad sense of community service, and thus their contribution to the improvement of the

community benefit is relatively indirect. Hence, we believed that the traditional

9 Measures for the Implementation of the Medical Law (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2010), Article 30-1 provides social medical service items including:expenses relating to the medical service, necessary transportation, auxiliary equipment, care, rehabilitation, burial service or other special needs of the poor family, the underprivileged family, the dependentless or homeless patients; expenses relating to the comforting of the patient or family; expenses relating to community medical healthcare, health promotion and community feedback etc.; expenses relating to convenient social service; expenses relating to the implementation of international medical help in cooperation with governmental policy.

26

charitable medical services should cover the expenses relating to the medical service, transportation, auxiliary equipment, care and rehabilitation of the poor family, the underprivileged family, the dependentless or the homeless patients. Medical services including community medical healthcare, health promotion and community feedback are characterized by public goods and externality, and should be the major items qualifying for tax free status of the medical institutions. Hence, we proposed that (1) and (2) should be listed as the core items of community benefit service of the medical institutions. Activities such as convenient services and the implementation of the international medical help in cooperation with government policy make indirect contribution to the community, and the range of the community has been expanded to the international level. We proposed to classify core items ((1) and (2)) and (3) as general community benefit services.

The second type of educational research and development activities include activities of research and development, talent cultivation, health education etc. Such activities include the internship, training and medical expertise improvement of medical service personnel as well as the purchase and updating of medical equipment and instruments. These activities, by nature, are investment in human capital and instrument and

equipment. Although they can enhance the medical service quality of the community residents in the long term, the contribution to the immediately need medical services of the residents is indirect. Therefore, they should be classified in the broad sense of community benefit service. We proposed to combine the first type uncompensated care services activities and the second type educational research and development activities as the community benefit service in broad sense. When developing the tax exemption regulations, we should provide the amounts of general and broad

community benefit services for medical juridical persons separately.

In addition, Article 46 of the Medical Law 46 requires not-for-profit hospitals to implement “research and development, talent cultivation, health education” activities, and Article 97 of the Medical Law 97 provides that teaching hospitals should engage in “research and development and talent cultivation” activities each year. The two kinds of activities should be apparently different by nature. The former, as provided in Article 46 of the Medical Law, means the medical care activities that can directly

27

benefit the community residents. The later, as provided in Article 97 of the Medical Law, means the academic research and development and improvement of medical expertise, which cannot immediately address the needs of the poor people. Although the connotations of the activities as provided in two articles are different, these two kinds of activities can hardly be distinguished in practice. Moreover, the competent authorities do not require the separate listing of the two kinds of activities in the financial reports of medical juridical persons. The expenditure of the second type activities is often mistakenly listed as that of the first type activities. For this, the competent authorities should expressly define the differences in the activities as provided in Articles 46 and 97 and require medical juridical persons to list the expenditure separately in the financial reports to facilitate the report analysts in reading and interpretation of the financial reports.

Due to limits of data structure and variable definition, the limitations of the empirical results of this paper should be noted: firstly, community benefit service benefits should be tangible and intangible, in this study, we measured the tangible benefit by pricing or cost and neglected the intangible external benefits such as the impact of altruistic people of the medically deprived getting charitable medical service, the preventive injection of epidemic vaccines to reduce the spread of diseases, and the reduction of the probability of getting diseases by promoting public health and disease prevention knowledge. The measurement of community benefit service in this study tends to be underestimated. Secondly, in the computation of the tax exemption interest derived from tax benefit, in this study, we used the concept of potential tax burden to estimate the tax exemption interest of the not-for-profit hospitals, namely,

not-for-profit hospitals or donors’ tax to pay without tax benefit. In this way, the behavioral change of not-for-profit hospitals in tax levying is not taken into

consideration. if the income of not-for-profit hospitals will be reduced without the tax benefit, as the income effect can reduce the supply of community benefit service to reduce medical cost and increase not-for-profit hospitals’ income, it may increase tax exemption interest. The estimation method used in this study may underestimate tax exemption interest amount; thirdly, in the computation of the tax benefit derived from business income tax exemption, in this study, we use the subtraction of the unadjusted after-tax net income by income tax expenses (benefit). Since the business income tax

28

rate was reduced from 25% to 17% in Taiwan, if the income tax expenses (benefit) can be deferred, the actual amount of tax exemption interest can be affected. Fourth, in the computation of land value tax exemption interest, in this study, we used Ministry of Health and Welfare Geographic Information System to search for the addresses of not-for-profit hospitals, and estimated the land value tax area by the covering area of each building without reviewing all the places for medical cause by floor. Therefore, it may overestimate the land value tax exemption interest. Fifthly, this paper is based on not-for-profit hospitals as the measurement basis; some medical juridical persons have a number of branches and affiliated institutions which may operate differently. However, as the financial reports are the disclosed information about the juridical person as a whole, we cannot analyze the hospitals individually. In particular, the branches located in different regions may face different community benefit service demands and thus the tax exemption interests may be different.

29

Reference

Arellano, M.

1993 “On the Testing of Correlated Effects with Panel Data”, Journal of

Econometrics, 59: 87-97.

Bryce H. J.

2001 “Capacity Considerations and Community Benefit Expenditures of Nonprofit Hospitals,” Health Care Management Review, 26 (3): 24-39.

Clement, J. P., D. G. Smith, and J. R. C. Wheeler (1994), “What Do We Want and What Do We Get from Not-For-Profit Hospitals?” Hospital & Health Services

Administration, 39(2), 159-179.

Frank, R. G. and D. S. Salkever (1991), “The supply of charity services by nonprofit hospitals: motives and market structure.” RAND Journal of Economic, 22(3), 430-445.

Frank, R. G., D. Salkever, and J. Mitchell (1990), "The supple of charity services by nonprofit hospitals: motives and market structure." The Rand Journal Economics, 22, 430-445.

Gentry, W. M., and J. R. Penrod (2000), “The Tax Benefits of Not-For-Profit Hospitals,” The Changing Hospital Industry: Comparing Not-For-Profit and

For-Profit Institutions, NBER Conference Report Series, 285-324, Chicago and

London: University of Chicago Press.

Hansmann, H. B. (1981), “The Rationale for Exempting Nonprofit Organizations from Corporate Income Taxation,” Yale Law Journal, 91(1), 54-100.

30

Judge, G., Griffith, W., Hill, R., and Lee, T. (1980), Theory and Practice of

Econometrics, New York, NY: Wiley.

Magnus SA, DG Smith, and JR Wheeler (2003), “Agency Implications of Debt in Non-for-profit Hospital: a Conceptual Framework and Overview,” Research in

Healthcare Financial Management, 8, 7-17

Magnus SA, DG Smith, and JR Wheeler (2004), “The Association of Debt Financing with Not-For-Profit Hospitals' Provision of Uncompensated Care,” Journal of

Health Care Finance, 30(4), 46-58.

Petersen, M. A. 2009. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. The Review of Financial Studies, 22 (1): 435-480.

Rosko, Michael D. (2002), “Factors Associated with the Provision of Uncompensated Care in Pennsylvania Hospitals,” Journal of Health & Human Services

Administration, 24(3), 352-379.

Rosko MD (2004), “The Supply of Uncompensated Care in Pennsylvania Hospitals: Motives and Financial Consequences,” Health Care Management Review, 29(3), 229-239.

Rushton, Michael (2007), “Why Are Nonprofit Exempt from the Corporate Income Tax,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(4), 662-675.

Sanders, Susan M. (1995), “The ‘Common Sense’ of the Nonprofit Hospital Tax Exemption,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 14(3), 446-466.

Spencer, C. S. (1998). "Do uncompensated care pools change the distribution of hospital care to the uninsured?" Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 23(1): 53-73.

31

Kim, T. H., M. J. McCue, and J. M. Thompson (2009), “The Relationship of Financial and Mission Factors to the Level of Uncompensated Care Provided In California Hospitals,” Journal of Healthcare Management, 54(6), 383-402.

Thorpe, K. E. (1988). "Uncompensated care pools and care to the uninsured: lessons from the New York Prospective Hospital Reimbursement Methodology." Inquiry 25(3): 344-353.

Wooldridge, J.M. 2002. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

O'Donnell, H. and R. Martire (2009). An update: An analysis of the tax exemptions granted to non-profit hospitals in Chicago and the metro area and the charity care provided in return. Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. available at

http://www.ctbaonline.org/All%20Links%20to%20Research%20Areas%20and% 20Reports/Health%20Care/Executive%20Summary%20and%20Charts_Final.pdf access at 2013/05/30.

The Institute for Health & Socio-Economic Policy (IHSP) (2012). Benefit from charity care: California not-for-profit hospitals. Report # 510-2732246. available at http://nurses.3cdn.net/2c18b9633089481d2c_qrm6yn2ci.pdf, access at