(2009)

Asian Social Work and Policy Review, Volume 3, pp.51-62

Pre-edited versionSocial Citizenship Rights and the Welfare Circle Dilemma – Reflections from the Attitudinal Findings of Two Chinese Societies

Chack-Kie Wong Professor

Social Work Department

The Chinese University of Hong Kong Shatin, Hong Kong

China

Kate Yeong-Tsyr. Wang Professor

Graduate Institute of Social Work, National Taiwan Normal University

Ping-Yin Kaun Associate Professor Department of Sociology National Chengchi University Abstract

This paper places social citizenship momentum into the context of squaring the welfare circle for examination. Citizenship is a powerful world-level organizing principle especially by the minority groups for their claim of equal treatment. The squaring of welfare circle refers to the need of the governments to constrain their budgets but also meet the rising demands from and needs of their people. This comparative study looks at the attitudinal findings of two Chinese societies of Hong Kong and Taiwan to see whether or not the cultural factor can mitigate the momentum of social citizenship rights and the demand side of the welfare circle. Implications for social policy are also discussed.

welfare

Introduction

This paper places social citizenship momentum into the context of squaring the welfare circle dilemma for examination. It explores whether or not the attitudinal findings of a comparative study of two Chinese societies, Hong Kong and Taiwan, can generate insights about factors that mitigate the momentum of social citizenship and the demand side of the welfare circle. Social citizenship momentum is conceptualized as a gap between high ideals of social citizenship rights and relatively low use of practicing social citizenship rights. The squaring of the welfare circle refers to the need of governments to constrain their budgets but also meet the rising demands from and needs of their people, while simultaneously maintaining popular legitimacy (George and Miller, 1994; George and Taylor-Gooby, 1996; Bonoli, George and Taylor-Gooby, 2000). In theory, the ideal practice gap generates momentum that begins to narrow the gap due to the powerful and moral appeal of social citizenship on the basis of egalitarian principles (Faulks, 2000; Lister, 2007). The rights-based concept of citizenship, in which the concept of social citizenship is one of its three components (Marshall (1950), first emerged historically in the European experience of state formation (Wong, 1999:97). It has become powerful with the development of the liberal tradition (Faulks, 2000:3). Of course, it does not deny that social citizenship can be simply a self-interested act, legitimized through the claim of citizenship rights. For example, even theorists on the left of the ideological spectrum such as Offe and Habermas are critical about the rights-based concept of social citizenship because they are demoralizing. Offe (1996:110) warns about the danger of institutions based on rights as being transformed into “nothing more than welfare-maximizing machines” even where they are just or reasonable. Habermas

(1992:10-11) criticizes that the existing institutions of the welfare state promote the passive dependency on welfare; there is a ‘clientalisation’ of the citizen role.

However, in the history of citizenship, citizenship as part of the global discourse of human rights and social citizenship, in particular, has been very powerful as a world-level organizing principle in legal, scientific, and popular conventions in the post war period (Soysal, 2001:67). It is particularly for the minority groups; that citizenship in general and social citizenship in particular provide them the moral ammunition for the claim that their unequal treatment is in fact an encroachment of their rights. In this light, citizenship rights become the benchmarks which the minorities can use to argue for equal treatment and basic human rights (Faulks, 2000:3). According to Marshall (1950:8), social citizenship rights is about the range of guarantees “from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live a life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society.” However, social citizenship rights require resources or actions for their implementation. As van Steenbergen’s (1994:3) states, it is the requirements of an active or even an interventionist state. The current reality of economic globalisation keeps the active state more constrained; hence, national governments in Western welfare states find it harder than before to ‘square the welfare circle’ (George and Miller, 1994; George and Taylor-Gooby, 1996; Bonoli, George and Taylor-Gooby, 2000),.

The squaring of the welfare circle dilemma reflects the drastic social and economic changes welfare states are now facing: aging populations, shifting labour markets, economic globalization, and weakened family structures. The ability to square the welfare circle is not only about additional resources but also about managing public expectations. In this light, the welfare circle dilemma connects to

citizenship momentum as the latter is likely to fuel the demand side of the welfare circle dilemma. It is also the case that citizenship momentum and the demand side of the welfare circle can be mitigated if public expectations are moderated by cultural factors such as the belief about the personal and family responsibility of welfare.

Despite the powerful and moral appeal of social citizenship, it is inherently limited by contextual constraints. This is the theoretical source of the recent ascendance of the pessimism over the application of social citizenship in the European Union - many observers see it as the decoupling of economic integration and social security (Faist, 2001; Schmitter and Bauer, 2000; Streeck, 1996:64). Schmitter and Bauer’s (2000:1) observe that, “the European Union has made only fitful and erratic progress in defining its social citizenship” as compared with “the resounding (if rather vacuous) commitment in the Treaty of Maastricht to political citizenship”. Even in social democratic Nordic countries like Finland and Sweden, social citizenship rights are weaker than before; changes were introduced in both countries in the 1990s to tightly link earnings-related benefits to contributions, thus diminishing the role of universal benefits (Timonen, 2001:29).

However, it is fairly important to determine whether this pessimistic view about the application of social citizenship rights is confined to non-western societies. Of course, non-Western societies are varied; they range from low-income societies in Africa and sub-Indian Continent to wealthier tiger economies in East Asia. In this article, we choose two tiger economies, Taiwan and Hong Kong, both are Chinese societies for close scrutiny. A review of literature finds that these two societies are wealthy but have less mature welfare systems in terms of social expenditure, the scope of provisions and the generosity of benefits, compared to their western counterparts (Jacobs, 1998; Lin, 1999; Walker & Wong, 2005). In other words, they

are likely to face the rising demands for social welfare like other advanced industrial societies embedded in the welfare circle dilemma; for example see the case of Hong Kong as illustrated in Wong (2008).

But these two Chinese societies have a Confucian tradition. Confucianism does not see individuals as atomistic, autonomous beings with enforceable claims against the state and their community; instead, individuals are people in the context of a social network within which that rights and responsibilities arise (Nuyen, 2002: 134). Hence, the idea of citizenship primarily for the protection of individual rights is not part of the Chinese philosophical tradition (Goldman and Perry, 2002:1; Wong, 1999). In Hong Kong, the encouragement of the Chinese to adhere to their cultural tradition has been part of the government policy; specifically, it means that people should be discouraged from relying upon social welfare; their sense of family responsibility should be strengthened; and government should assign a greater role in meeting the need of social welfare to the family and the third sector (Chau and Yu, 2005:32-34; Walker and Wong, 2005:215). Similar emphasis on family responsibility as a benign excuse for minimal or limited intervention by the government is also evident in Taiwan (Hwang and Hill, 2005:160; Lin, 2006). Given these facts, are the Chinese societies of Hong Kong and Taiwan different from the West in terms social citizenship rights and the welfare circle dilemma? Does it mean that the momentum for social citizenship rights loses its place? It is the aim of this article to look at these questions through the use of a comparative study of attitudinal findings of Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The contributions of the cultural factors

general and specific ideas (Higgins, 1981). As Hill (2006:11) suggests, one must determine whether the claim of some measure of universality in a comparative analysis of social policy “may only be applied in a static way to one society at one point of time”. Hence, the Chinese context should be a good testing ground to determine whether the momentum of social citizenship rights and the demand side of the welfare circle are counteracted in different cultural contexts, where people believe more in self-reliance, families and responsibilities over rights.

Taiwan and Hong Kong are rich Chinese societies; both have high GDP per capita (US $25,191 and 15,668 respectively in 2005).i Their high economic standards have an added value. According to the convergence theory, industrialization, urbanization and high economic standards as their manifested feature are likely to fuel rising demands for social welfare (Mishra, 1977:33-42; Rimlinger, 1971; Hill, 2006:17-18). In other words, the study of these two wealthy Chinese societies can highlight the contribution of cultural factors.

Despite the fact that Hong Kong and Taiwan are both Chinese societies, they have different political and welfare systems. The political system of Hong Kong, being a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, is much less democratic than Taiwan in terms of electing the head of government and members of the legislature. However, both societies have similar levels of social expenditures as a share of the GDP (Hong Kong, 10.1% and Taiwan, 11.1%, 2005).ii In terms of the nature of its welfare system, Hong Kong is more residually-oriented in social policy, following a neo-liberal trajectory (McLaughlin, 1993; Walker & Wong, 1996; Wong, 2008), whereas Taiwan has followed a corporatist path in its welfare regime development (Goodman & Peng, 1996; Hill & Hwang, 2005). In other words, they are both good testing grounds for determining the power of culture, assuming that both

societies have the same cultural heritage of Confucianism, with a particular emphasis on the values of self-reliance, family, and responsibility over rights (Chau & Yu, 2005; Fukuyama, 1997; Milner, 1999; Sen, 1997; Walker & Wong, 2005).

The findings of the comparative study will have significant theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, it will verify whether Confucianism or similar cultural values such as Victorian values and American values which share similar moral tone, is a countervailing force to the egalitarian moral power of social citizenship and as a brake to the demand side of the welfare circle. Practically, it will indicate that Chinese societies or societies with similar cultural backgrounds are more advantageous than their Western counterparts in terms of mitigating the demand for social welfare fueled by social citizenship rights and the demand side of the welfare circle.

The two opinion surveys and measurement

Both the Taiwan and Hong Kong surveys used a similar set of questions on social citizenship, but the Hong Kong survey had a longer questionnaire that covered all the three dimensions of citizenship; however, only the questions on social citizenship are used here for comparison. The Hong Kong study was undertaken in 2002; it used face-to-face interviews with 712 adults, ages 18 and above, who were selected using a stratified random sampling method. The sample was representative of the larger population in terms of key variables, including age, household income, gender, and occupation, all listed in the 2001 population census. The Taiwan study was undertaken in 2005, it used telephone interviews due to its shorter questionnaire, only social citizenship questions were asked. Proportional allocation sampling was used to select respondents from Taipei City and Taipei County, since the social-economic

characteristics of these two areas were relatively comparable with those of Hong Kong. In the end, a sample size of 1,029 adults, ages 18 and above, was achieved. Both studies aimed at responding to two types of statement: “Citizens should have rights (or responsibilities) in a specified area” and “In practice, Hong Kong/Taiwan people have rights (or responsibilities) in a specified area”. The first statement is designed to elicit the perception of an ideal, while the second, a perception of the actual practice of social citizenship in each respective Chinese society. In Hong Kong, five components of social citizenship include work, basic education, a guarantee of basic living standards, parental care of children and government making good use of public money at both ideal and practice levels. However, the Taiwan survey adds the “care of parents” component into the social citizenship concept because of its filial piety value.

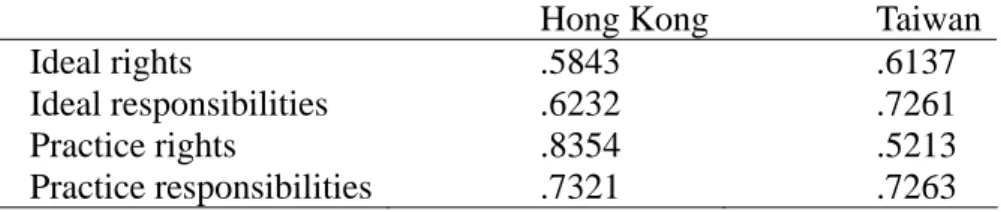

Despite this inclusion, their respective tests by alpha reliability are acceptable or satisfactory, except for the somewhat low values of .5213 in practice rights in Taiwan and .5843 in ideal rights in Hong Kong. Apart from these, the values of the other six variables are respectable, for example, .7321 in practice responsibilities and .8354 in practice rights in Hong Kong (Table 1). These statistical findings reflect that the scales used by both studies, despite their different completion times, are real social citizenship constructs. The exact wordings of each component of all social citizenship variables have been reported in the findings session.

Table 1. Alpha Reliability of Social Citizenship Variables

Hong Kong Taiwan

Ideal rights .5843 .6137

Ideal responsibilities .6232 .7261

Practice rights .8354 .5213

The findings

The findings of each study are summarized in tables 2 and 3. Table 2 presents the frequencies of the responses to the five or six components of social citizenship on both ideal and practice levels (i.e., in terms of expectation and practice) and along two dimensions (i.e., that their rights and responsibilities).

The first column on the ideal level between rights and responsibilities is viewed first. The frequencies of the first three components, work, basic education and a guarantee of basic living, are all on high levels, while rights are matched with responsibilities in both societies. For the next three components (two for Hong Kong), parental care of children, children caring for parents and government making good use of public money/everyone should have the responsibility of paying taxes, there are more ideal responsibilities than ideal rights. In summary, on an ideal right-responsibility level, the two Chinese societies somewhat expect more responsibilities or are somewhat “rights deficit”.

Among ideal levels of rights, a proportion of respondents in both societies believe their right to ask the government to take care of their children is relatively low, compared to other components of rights and ideal responsibility levels (75.2% in Taiwan and 41.4% in Hong Kong on the ideal right level; 96.3% in Taiwan and 97% in Hong Kong on the ideal responsibility level). The results show that people in both societies have some ambivalence towards expecting government assistance in taking care of their children. These societies are evidently experiencing a responsibility-surplus phenomenon; the right-responsibility gap is widened even further in the case of Hong Kong (97% responsibility versus 41.4% right), which favors the government. Family values within Chinese culture can still be found, however, it is more prevalent in Hong Kong than in Taiwan for parents to ask the

government for help in caring for their children.

On the second column, between the rights and responsibilities of the two Chinese societies, a more complicated picture than the first column is seen. For work, both societies perceive themselves as having more practice rights than practice responsibilities; perhaps people regard themselves as not hardworking enough. On the level of responsibility, the statement is as follows: “Everyone should have the responsibility to work for one’s own living”. This may indicate that Taiwan and Hong Kong are still dominated by a traditional work ethic; people see themselves as having a greater right to a job than working hard enough for their own living.

However, one still can find differences between these two societies in the work component. Fewer respondents in Hong Kong (43.4% in Hong Kong, compared to 68.7% in Taiwan) think their right to work has been fulfilled. This may be because in 2002, Hong Kong had a higher unemployment rate of 7.3%, compared to Taiwan’s 2005 rate of 4.4%.

For the next four components (three for Hong Kong), basic education, guarantee of basic living, care of children and care of parents, there are more practice responsibilities than practice rights indicated; for instance, on both right and responsibility, the Chinese in both societies experience a responsibility surplus, which includes more responsibility on the part of the people and less on the part of the government (12.9% in Taiwan and 27% in Hong Kong for practice rights asking for government assistance in childcare, compared with 61.5% in Taiwan and 62.8% in Hong Kong in practice responsibility in terms of having the duty for child care).

As mentioned before, a question on the care of elderly parents was not included on the Hong Kong questionnaire, but the Taiwan response pattern is very similar to that of the right and responsibility of child care; more responsibility is needed to fill

the right-responsibility gap. This gap may indicate that people view themselves as having less right in relation to agents of the state for either child care or the care of elderly parents and more responsibility for these two family responsibilities. This finding should have significant implications on the relationships in the welfare circle dilemma. The squaring of the welfare circle indicates that people expect more rights. This theoretically generates demand for social welfare. If the Chinese people expect more responsibilities than rights in relation to family care, either for children or for elderly parents, then cultural factors will seemingly mitigate the pressure on the welfare circle.

For the last component, “government making good use of public money/everyone should have the responsibility of paying taxes”, people comprising these two Chinese societies offered different responses. Taiwan Chinese people see themselves as having a rights surplus. Perhaps this is a result of the political experience of a western-style democracy at work. The Hong Kong Chinese people are on the opposite side of the spectrum–they see themselves as having more responsibility through the payment of taxes. In return, due to a lack of political democracy, they do not have the right in practice to pressure government on the prudent use of public money. In a nutshell, there is generally a greater responsibility surplus than a right surplus in practice social citizenship for these two Chinese societies.

[Inset Table 2]

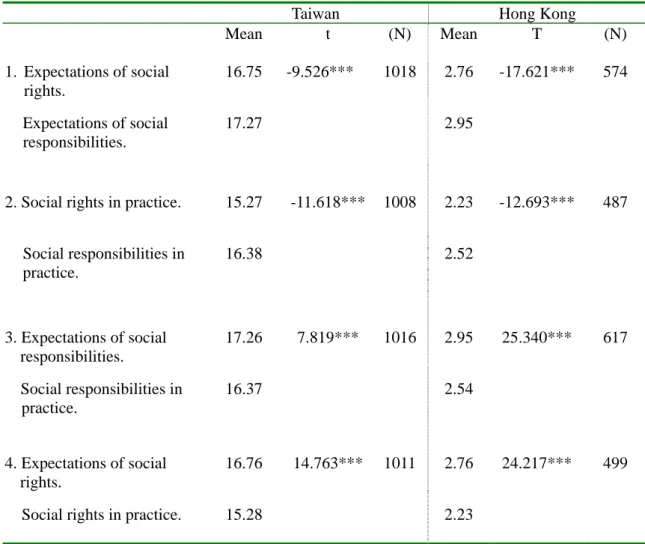

Table 3 provides another angle for viewing the same two sets of data. However, by aggregating all frequencies of the five or six components of the levels of social

right or social responsibility into the mean and then comparing them by using a t-test, it has been found that people living in both Taiwan and Hong Kong exhibit similar orientations towards social citizenship. On an ideal level, they take upon themselves more social responsibilities than social rights; on the practice level, they have more practice social responsibilities than practice social rights. When studying expected social rights and practice social responsibilities, they have more practice social responsibilities; between practice and expected social rights, they have more practice social rights. All t-tests conducted on the above pairs are found to be statistically significant.

The findings from Taiwan and Hong Kong both support the optimistic view that social citizenship rights will retain momentum due to their strong moral power for social equality. However, the moral power of social citizenship rights is likely to be constrained by social citizenship responsibilities on both ideal and practice levels.

In conclusion, the findings of aggregate statistical analyses by t-testing shown in Table 3 are clear and straightforward – people in these two Chinese societies are similar in terms of matches between social citizenship practice and expectations; it is found in the Hong Kong and Taiwan surveys that the Chinese people normally have a rights deficit and a responsibility surplus. Both societies attained higher than expected scores for social citizenship rights and lower practice social citizenship rights. This ideal practice gap provides a momentum for narrowing the gap. Both societies also have a responsibility surplus; this means that the value of responsibility in principle serves as a brake to the welfare circle dilemma, on the demand side of the relationship, underlying Western welfare states.

Conclusion and reflections for social policy

In both Taiwan and Hong Kong, the empirical findings of opinion surveys on social citizenship are found to be similar despite their different political and welfare systems. Taiwan is more democratic than Hong Kong; its welfare system has followed the corporatist path whilst Hong Kong is more residual-oriented. However, both societies have similar levels of social expenditures as a share of GDP. Now, we have two Chinese societies, both with similar findings on family values in caring, albeit it is more prevalent in Hong Kong than in Taiwan for parents to ask the government for help in caring for their children. Nevertheless, the identification of the family values strengthens the claim that the cultural factor plays a role in mitigating the momentum of social citizenship rights and the demand side of the welfare circle – the Chinese expect more responsibilities than rights in relation to family care, either for children or for elderly parents. The empirical findings also confirm that social citizenship right does not lose its momentum despite the strong traditional values of responsibility, family and self-reliance that these Chinese societies have.

Perhaps this comparative study cannot confirm whether the immature welfare systems, in terms of social expenditures, are a result of these attitudinal orientations or, as suggested by some observers, that their governments simply use their cultural legacy as a “convenient excuse, with persuasive historical and cultural camouflage, to filter responses to social welfare needs” (Walker and Wong, 2005:215). For example, social assistance recipients in Hong Kong are required to undertake community services in exchange for their benefits in order to preserve the self-reliance value (Social Welfare Department, 1998). The Taiwan government is particularly harsh towards their employable social assistance recipients, even though they do not have

any earning, the government still calculates their earnings based on the level of official minimum wage. Apparently, this policy initiative aims to create hardship in the camouflage of encouraging self-reliance. Nevertheless, within the comparative study of the two Chinese societies, all are considerably wealthy but have lower levels of social expenditures, confirming the claim that the demand side of the welfare circle dilemma can be somewhat lightened, if a cross-cultural analysis is taken. Greater wealth being brought to the Chinese does not necessarily result in comparable social welfare as Western welfare states have attained, as predicted by the convergence theory of industrialization and urbanization. Hence, the cultural factor is something that requires attention if squaring the welfare circle is a significant policy goal, especially in today’s globalised economy.

Perhaps this study needs to explore further about economic influences and investigate mainland Chinese to see whether they exhibit similar welfare orientations in terms of mitigating the momentum of social citizenship rights and the demand side of the welfare circle. Of course, that would be an added value. However, the comparative analysis of Hong Kong’s and Taiwan’s attitudinal data have already provided adequate empirical evidence pointing to the merits of cultural legacy as a countervailing force to the powerful momentum articulated by the universal appeal of social citizenship rights, especially in the case of child and elderly care.

From a practical vantage point, it seems that both Chinese societies have a greater chance of striking a proper balance between social rights and social responsibilities; their citizens have responsibility surplus attitudes and beliefs. So, what does this reflect on social policy?

First of all, European pessimism over the application of social citizenship is perhaps a temporary setback or a reflection of the inherent nature of social citizenship

heightened by economic globalization. Momentum is still present, even in its most “hostile” ground; Chinese people are said to have an aversion to the welfare state (Chau & Yu, 2005; Walker & Wong, 2005:215). In other words, the momentum for social citizenship rights is still a driving force for social equality, in spite of the fact that it needs to adjust to different social realities.

Second, the Chinese cultural heritage of self-reliance, family, and responsibility is not necessarily contradictory to the belief of universal appeal of social citizenship rights for social equality (Wong and Wong, 2005). Nevertheless, the Chinese people are still the beholders of a cultural heritage that believes in social responsibility. This co-existence has significant policy implications. It will shed light on squaring the welfare circle, as the demand side can be countervailed by the traditional values of responsibility, family, and self reliance.

Last, but not the least, it is important to realize that cultural heritage can be eroded by institutional arrangements. There are cultural heritages similar to Confucianism, such as Victorian values and American values that are also found in the West. However, they are no longer sufficiently valued to allow for the avoidance of pitfalls in welfare systems. This raises a warning signal for the erosion of traditional cultural heritage.

It is noteworthy that culture is variable, not fixed and long-lasting. Problems facing mature Western welfare states today may not necessarily be replicated in the future for Chinese and other non-Western societies if appropriate cultural variables are identified and are well-integrated into welfare systems. For instance, in order to tackle the moral hazard of welfare dependence, the Singaporean government has introduced the Work Bonus and Workfare Income Supplement in 2006 and 2007, respectively, to encourage inactive low-skilled workers to enter and stay in the workforce because

work, through these policy initiatives, will be made financially worthwhile (Poh, 2007). As mentioned in above, Hong Kong and Taiwan have made policy initiatives to avoid moral hazard for the sake of preserving their cultural heritage.

Similar policy initiatives are also found in the West. For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit of the United States is an initiative that aids low-income workers. The thrust of this policy initiatives is an attempt to align rights with responsibility. These types of government aid, or a right, reinforce the belief that work, or responsibility, is matched with earning, a better deal than welfare. In summary, it takes policy changes on the part of the state to establish institutional arrangements that keep cultural heritage alive in new social and economic contexts.

Table 2. Comparison of Taiwan’s and Hong Kong’s respondents’ views on social rights and social responsibilities for ideal and practice levels (% of agree/strongly agree).

Ideal level Practice level

Right Responsibility Right Responsibility

Right/responsibility Taiwan Hong Kong Taiwan Hong Kong Taiwan Hong Kong Taiwan Hong Kong 1. Everyone should have

the right to a job/ Everyone should have the

responsibility

to work for one’s own living.

92.7 95.3 94.7 96.0 68.7 43.4 46.6 39.2

2. Everyone should have the right to basic education/ Parents should have the responsibility of providing basic education to their children.

98.0 97.5 98.0 99.3 86.3 83.1 85.6 84.2

3. Everyone should be guaranteed basic living needs/ Everyone should be responsible for

guaranteeing one’s basic living needs.

96.6 87.8 98.8 96.3 31.8 39.7 43.4 48.7

4. Parents have the right to ask for government assistance for the care of children/ Parents have the duty to care for their children.

75.2 41.4 96.3 97.0 12.9 27.0 61.5 62.8

5. Adult children have the right to ask for government assistance for the care of parents / Adult children have the duty of caring for their parents

75.0 - 97.5 - 13.6 - 34.5 -

6. Everyone has the right to expect government to make good use of public money/ Everyone has the

responsibility of paying taxes

98.8 81.8 93.6 89.3 72.7 25.2 63.4 55.3

Notes: 1. For Taiwan’s data, four-point scales from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” are used to answer questions about expectations of society. Questions on the practice of social rights and responsibilities are also evaluated using a four-point scale, from “most people”, “half and half”, “few” to “none”.

2. For HK’s data, five-point scales, from “strongly disagree”, ”disagree”, ”fair”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”, are used to answer questions about expectations for social rights and responsibilities. Questions on the practice of social rights and responsibilities are evaluated using a three-point scale, from “most people”, “half and half”, “few” to “none”.

-

Table 3. Comparisons between expectations and practice and rights and responsibilities between Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Taiwan Hong Kong

Mean t (N) Mean T (N) 1. Expectations of social rights. 16.75 2.76 Expectations of social responsibilities. 17.27 -9.526*** 1018 2.95 -17.621*** 574

2. Social rights in practice. 15.27 2.23

Social responsibilities in practice. 16.38 -11.618*** 1008 2.52 -12.693*** 487 3. Expectations of social responsibilities. 17.26 2.95 Social responsibilities in practice. 16.37 7.819*** 1016 2.54 25.340*** 617 4. Expectations of social rights. 16.76 2.76

Social rights in practice. 15.28

14.763*** 1011

2.23

24.217*** 499

Note:

1. For Taiwan’s data, four-point scales, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, are used to answer questions about expectations of social rights and responsibilities. Questions on the practice of social rights and responsibilities also use a four-point scale, from “most people”, “half and half”, “few” to “none”.

2. For HK’s data, five-point scales, from “strongly disagree”, ”disagree”, ”fair”, “agree”, “strongly agree”, are used to answer questions about the expectations of social rights and responsibilities. Questions on the practice of social rights and responsibilities are on a three-point scale, from “most people”, “half and half”, “few” to “none”.

References:

Bonoli, G.., George, V. & Taylor-Gooby, P. (2000), The future of the Welfare State in

European Welfare Policy: Squaring the Welfare Circle, George V & Taylor-Gooby, P., ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Chau, R. C. M. & Yum, W. K. (2005), ‚Is welfare unAsian?’ East Asian Welfare

Regimes in Transition From Confucianism to Gobalisation, Bristol: Policy Press.

Faist, T. (2001), ‘Social citizenship in the European Union: Nested membership’,

Journal of Common Market Studies, 39,1,37-58.

Faulks, K. (2000), Citizenship, London: Routledge.

Fried, C. (1978), Right and Wrong, London: Harvard University Press.

Fukuyama, F. (1997), The Illusion of Exceptionalism, Journal of Democracy, 8,3, 146-149.

George, V. and Miller, S. (1994), Social Policy Towards 2000, London: Routledge.

George, V. and Taylor-Gooby, P. (1996), European Welfare Policy Squaring the Welfare

Circle, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Goodman, R. & Peng, I. (1996), ‘The east Asian welfare states: Peripatetic learning, adaptive change, and nation-building’, Welfare States in Transition, Esping-Andersen, G., (ed.) London: Sage.

Goldman, M. and Perry, E. J. (2002), ‘Introduction: political citizenship in modern China’, in M. Goldman and E. J. Perry (eds.), Changing Meanings of Citizenship in Modern China, Cambridge, MA: Harvanrd University Press.

Habermas, L. (1992) ‘Citizenship and national identity: some reflections on the future of Europe. Praxis International 12:1-19,

Higgins, J. (1981), State of Welfare – Comparative Analysis in Social Policy, Oxford: BBP & MR.

Prentice-Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Hill, M. & Hwang, Y. S. (2005), ‘Taiwan: What kind of social policy regime?’ In Walker, A. & Wong, C.K. (eds.) East Asian Welfare Regimes in Transition, From Confucianism to Globalisation, Bristol: Policy Press.

Jacobs, D. (1998), Social Welfare Systems in East Asia: A Comparative Analysis

including Private Welfare, London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.

Lin, K. (1999), A Cultural Interpretation of Confucian Welfare Cluster. Tempere: Tempere University Press.

Lin, W.I. (2006), Social Welfare in Taiwan, Taipei: Wu-Nan.

Lister, R. (2007), ‘Inclusive citizenship: Realizing the potential’, Citizenship Studies, 11,1,49-61.

Marshall, T.H. (1950) Citizenship and social class and other essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mclaughlin, E. (1993), ‘Hong Kong: A residual welfare regime’,. Cochrane, A. & Clarke, J.,

(eds.) Comparing Welfare States, London: Sage.

Milner, A. (1999), ‘What’s happened to Asian values?’ Beyond the Asia Crisis.

Goodman, D. & Segal, G., (eds.), accessed on June 9, 2006, from

www.anu.edu.au/asianstudies/values.html.

Mishra, R. (1977), Society and Social Policy, London: Macmillan Press.

Nuyen, A.T. (2002). ‘Confucianism and the idea of citizenship’, Asian Philosophy, 12, 2, 127-39

Offe, C. (1996), Modernity and the State, Cambridge: Polity.

Poh, J. (2007), ‘Workfare: The fourth pillar of social security in Singapore’, Ethos, 3, October, Singapore: Civil Service College.

Russia, New York: Routledge.

Schmitter, P. C. & Bauer, M. W. (2000), A (modest) Proposal for Expanding Social

Citizenship in the European Union, European University Institute, August.

Sen, A. (1997), ‘Human rights and Asian values: What Lee Kuan Yew and Le Peng don’t understand about Asia’, The New Republic, accessed on June 9, 2006, from

http://www.sintercom.org/polino/polessays/sen.html.

Social Welfare Department (1998), Support for Self-Reliance Report on Review of the

Comprehensive Social Security Assistance Scheme, Hong Kong: Social Welfare Department, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Soysal, Y.N. (2001), ‘Changing citizenship in Europe: Remarks on post-national membership and the nation state’, in Fink, J., Lewis, G.. & J. Clarke, (eds.) Rethinking European Welfare, London: The Open University and Sage.

van Steenbergen, B. (1994), The condition of citizenship: An introduction. The Condition

of Citizenship, B. van Steenbergen, (ed.) London: Sage.

Streeck, W. (1996), ‘Neo-voluntarism: A new European social policy regime?’ Marks, Scharpf et. al, (eds.) Governance in the European Union, London: Sage.

Timenon, V. (2001), Earning welfare citizenship: Welfare state reform in Finland and Sweden. Taylor-Gooby, P. (ed.) Welfare States under Pressure, London: Sage.

Walker, A. & Wong, C. K. (1996), ’Rethinking the western construction of the welfare State,’, International Journal of Health Services 26,1, 67-92.

Walker, A. & Wong, C. K. (2005), East Asian Welfare Regimes in Transition, From

Confucianism to Globalisation, Bristol: Policy Press.

Wong, R. B. (1999), ‘Citizenship in Chinese history’, in M. Hanagan, and C. Tilly (eds.)

Extending Citizenship, Reconfiguring State, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Wong, C. K. & Wong, K. Y. (2005), ‘Expectations and practice in social citizenship: Some insights from an attitude survey in a Chinese Society’, Social Policy and

Administration, 39, 1,19-34.

Wong, C.K. (2008), ‘Squaring the welfare circle in Hong Kong, lessons for governance in social policy’, Asian Survey, XLVIII, 2, 323-342.

i

Source of figure – Department of Investment Services, Republic of China Taiwan (u.d.) accessed on 21 November 2008

http://investintaiwan.nat.gov.tw/en/env/stats/per_capita_gdp.html ii