從全球整合行銷觀點檢視台灣觀光行銷溝通 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 從全球整合行銷觀點檢視台灣觀光行銷溝通 Examining the Tourism Marketing Communication Program of Taiwan from the Globally Integrated Marketing Communication Perspective. Student: 林珮君 Pei-Chun, Lin Advisor: 張郁敏 Dr.治 Yuhmiin, Chang. 大. 學. 國立政治大學 國際傳播英語碩士學程. Nat. A Thesis. sit er. io. al. y. 碩士論文. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政. n. iv n C U h eMaster’s Submitted to International in International n g c h iProgram Communication Studies National Chengchi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master in International Communication Studies. 中華民國九十八年八月 II.

(3) Acknowledgement It’s strange to write this acknowledgement one year after the accomplishment of my thesis. However, when start thinking what to write, I found what happened last summer was still deeply imprinted in my memory. I would like to give my sincere gratitude to those who have supported me during those stressful days when I was busy writing my thesis and, at the same time, preparing for my oncoming exchanged life to Japan. First of all, I would like to thank my dear advisor, Dr. Yuhmiin, Chang, for her ceaseless support, both academically and mentally. Her suggestions for my thesis always inspired me to think deeper and further, helping me overcome the difficulties I encountered; her advice for my exchanged life as well as for my future also served as a great encouragement to keep me moving on. I would also like to give my gratitude to the evaluation committee members, Prof. I-Huei, Cheng, and Prof. Huiling, Chen, for their insightful suggestions.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. In addition, I would like to thank all IMICS members, for their company making my graduate student life unforgettable. It is also because of their personal sharing that encourages me to pursue my studying overseas to experience a different world as they did. I will remember those good old days when we were together and look forward to our next reunion someday, somewhere around the world.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. i Un. v. I would also like to thank Mr. Su for his always being by my side, listening to my complaint and encouraging me by finishing his thesis much earlier than mine (ha, it did work). I also want to thank my dear friends, who might not be around me most of time but always give me support during those difficult times.. engchi. Last but not least, I would like to thank my family, for their trust and constant support for any of my decision in my life. Home is always the place I feel safe and relieved. 爸爸媽媽,謝謝你們一直以來對我的支持和鼓勵,未來我會更努力的。. Pei-Chun, Lin Oct., 2010. III.

(4) Abstract Tourism industry, one of the most rapid growing economic activities around the world, brings countries foreign exchange and creates million jobs. Due to the huge profit involved, more and more countries recognize the importance of tourism marketing and start to include it into their national development plan, so does Taiwan. However, little attention has been paid in the academic field to Taiwan’s tourism promotions on a global basis. Therefore, this research aims at analyzing how Taiwan manages and integrates its tourism marketing communications in its three main target regions—Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, and Europe and America—from the perspective of Globally Integrated Marketing Communication (GIMC), and uses the. 政 治 大. current campaign “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009” as the subject. Following the IMC Audit proposed by Duncan (2002), this case study conducts. 立. document analysis and in-depth interviews with Tourism Bureau to investigate how. ‧ 國. 學. Taiwan integrates its global communication either vertically across marketing disciplines or horizontally across countries. In addition, the level of standardization. ‧. across marketing disciplines is compared, and suggestions for employing GIMC model are also provided. The finding can be summarized into three points:. sit. y. Nat. al. er. io. 1. Either within each region or across regions, the strategies Tourism Bureau. n. employs are close to globally integrated strategy, but with different level of. Ch. vertical and horizontal integrations.. engchi. i Un. v. 2. The proposition, which suggests that public relation, sales promotion, and direct marketing are more difficult to standardize compared to advertising, is not supported in the case of “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009.” 3. The application of GIMC to tourism marketing in this case suggests that strategy should be the guiding principle for integration; and the classification of GIMC strategy should be adjusted and made based on a continuum approach.. Keywords: Globally Integrated Marketing Communication (GIMC), Taiwan Tourism, Vertical Integration; Horizontal Integration. IV.

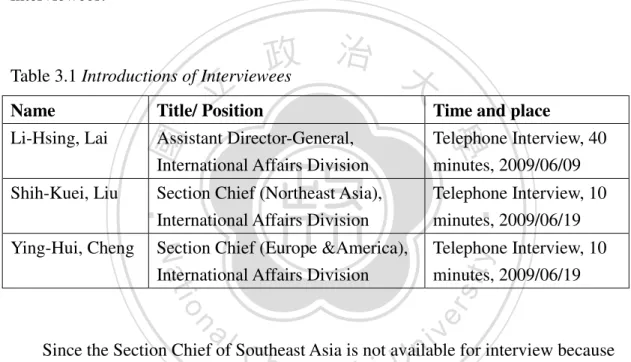

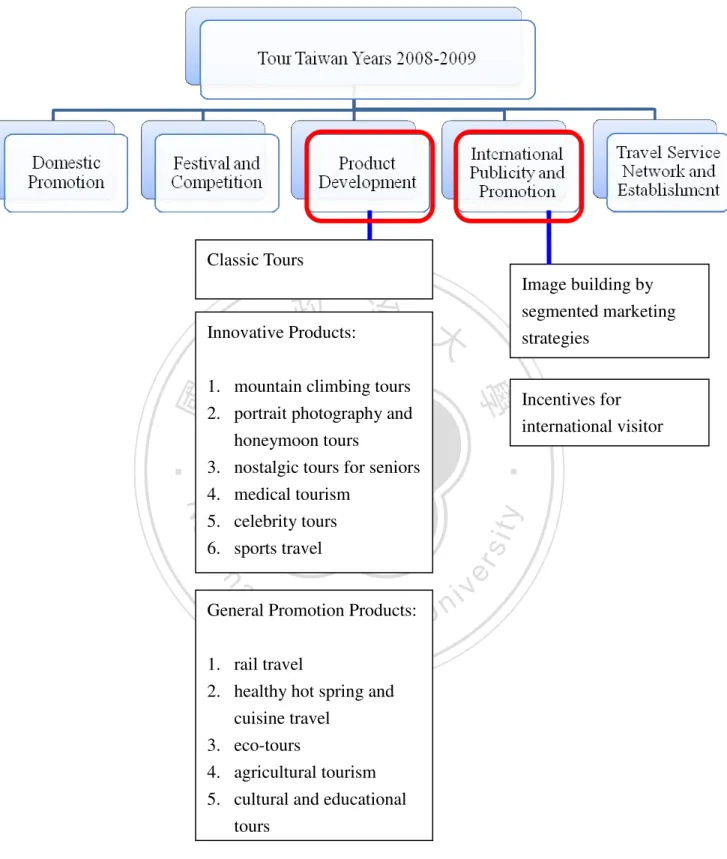

(5) TABLE OF CNTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Research Background ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Research Purpose............................................................................................................ 3. 2. Literature Review....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Tourism industry ............................................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 Definition of Tourism ............................................................................................... 5 2.1.2 Characteristics of tourism industry ........................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Tourism Destination Branding ................................................................................. 9. 政 治 大. 2.2 Tourism Destination Marketing .................................................................................... 12. 立. 2.3 GIMC............................................................................................................................. 15. ‧ 國. 學. 2.3.1 Definition................................................................................................................ 15 2.3.2 Standardization vs. Adaptation ............................................................................... 20. ‧. 3. Research Method ..................................................................................................... 37. y. Nat. sit. 3.1 Case Study ..................................................................................................................... 37. n. al. er. io. 3.2 Case study: Data Collection .......................................................................................... 38. i Un. v. 3.2.1 Research Scope: Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009 ................................................... 38. Ch. engchi. 3.2.2 In-depth Interview .................................................................................................. 38 3.2.3 Data Analysis.......................................................................................................... 39. 4. Analysis.................................................................................................................... 42 4.1 Background of “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009” ......................................................... 42 4.2 Target Market of “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009” ...................................................... 46 4.3 The Objectives of Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009 ........................................................ 48 4.4 Brand Positioning, CIS and Slogan ............................................................................... 49 4.5 GIMC Strategy: Within Region..................................................................................... 53 4.5.1 Northeast Asia (Japan and Korea) .............................................................................. 53 4.5.2 Southeast Asia (Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia) ............................................ 67 V.

(6) 4.5.3 Europe and America ............................................................................................... 78 4.6 GIMC Strategy: Across Regions ................................................................................... 91 4.6.1 Horizontal Integration across Regions ................................................................... 91 4.6.2 Level of Standardization across Marketing Disciplines ......................................... 94. 5. Summary and Discussion......................................................................................... 97 5.1 Summary ....................................................................................................................... 97 5.2 Managerial Implications .............................................................................................. 106 5.3 Limitations and Suggestions........................................................................................ 109 5.3.1 Research Limitations ............................................................................................ 109. 政 治 大 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................... 111 立. 5.3.2 Suggestions for Future Research .......................................................................... 109. ‧ 國. 學. APPENDIX 1. Advertising ........................................................................................ 118 APPENDIX 2. Public Relation (PR) ......................................................................... 128. ‧. APPENDIX 3. Website of Tourism Bureau .............................................................. 132. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. APPENDIX4. Interview Outline ............................................................................... 137. Ch. engchi. VI. i Un. v.

(7) 1. Introduction 1.1 Research Background Can a country be marketed? Can we manage and treat a country like a brand of product? This question may be difficult to answer since “Sell a country?” may become the first problematic issue encountered. However, more and more people nowadays start to relate the concept of brand not only with products or companies but also with countries. Indeed, countries, like consumer brands, also need to compete with other country brands for reputation, tourists or investments. Thus, branding. 治 政 becomes an effective way to differentiate themselves from 大 others. With this emerging 立 phenomenon of country branding around the world, it is generally agreed by ‧ 國. 學. academics as well as practitioners that countries can be branded and marketed as other. ‧. consumer goods or services (e.g., Ham, 2001; Kotler, 2002), although there exist. sit. y. Nat. some fundamental differences in between.. io. er. Based on the idea of country as a brand, Anholt (2003) developed a “Nation. al. Brand Hexagon.” According to this model, “the nation brand is the sum of people’s. n. iv n C perceptions of a country across six h areas of national competence, including tourism, engchi U export, governance, investment and immigration, culture and heritage, and people (Anholt, 2005, p.297).” Among the six dimensions of the hexagon, tourism is often the most visible promoted aspect of the nation brand and the images formed from tourism promotion of country have a much stronger impact on people’s perceptions toward a country as a whole (Anholt, 2003). Indeed, tourism industry is one of the most rapid growing economic activities around the world. It can benefit a country by increasing its foreign exchange and also. 1.

(8) creating job opportunities. According to World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC)1, the contribution of Travel and Tourism to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is expected to reach 9.5% (US$10,478 billion) and create near 300 million jobs opportunities by 2019. In addition, World Tourism Organization (WTO)2 forecasts the international tourist arrivals are expected to reach nearly 1.6 billion by 2020, indicating the great potential tourism contributes to the development of national economy. Since the huge profit involved in tourism industry, more and more countries recognize the importance of tourism marketing and start to include it into their national development plan. For example, in 1999 New Zealand promoted its tourism. 治 政 brand by implementing the campaign, “100% pure New 大Zealand,” which has been 立 considered as one of the most successful destination branding activities (Morgan et al., ‧ 國. 學. 2002). Back to Taiwan, in 2002 the Administrative Yuan proposed “Doubling. ‧. Tourists Arrivals Plan,” which aimed at doubling the tourist arrivals to 2 million and. sit. y. Nat. raising the total numbers of visitor arrivals up to 5 million in 2008. However, the plan. io. er. failed by only reaching 3.84 million in 2008, although it has grown by 3.4%. al. compared to the previous year. The government attributes the failure mainly to the. n. iv n C global financial crisis, which decreases willingness and ability to travel h epeople’s ngchi U. around. In fact, according to WTTC, growth of tourism in a few years is expected to slow down, but it also stresses that this expansion is still healthy given the economic difficulty and in the future the contribution of tourism will still increase. Concerning the current global economy, Taiwan government revises the goal down to 4.25 million tourist arrivals in 2009, and thus launches the latest plan, “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009.” With global economic recession, competition between each country for attracting 1. World Travel and Tourism Council http://www.wttc.org/. 2. World Tourism Organization http://www.unwto.org/index.php 2.

(9) tourists becomes even violent. How to develop an effective and powerful strategy to market countries becomes a critical issue for many nation leaders. Moreover, marketing countries needs to consider the complexity of international settings and global communications. Therefore, the application of Globally Integrated marketing communications (GIMC) may be seen as an effective way to address this issue. GIMC, the modification and extension of Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC), coordinates not only the vertical dimensions of promotion disciplines (i.e. advertising, brand management, public relation, etc.) as in IMC, but also the horizontal dimensions in terms of organizations and countries (Grein and Gould, 1996). In this. 治 政 way, GIMC may have the potential for strategically managing 大 global promotions of 立 countries. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 1.2 Research Purpose. sit. y. Nat. Given the increasing importance of tourism industry to national economy, this. io. er. research aims at analyzing to what degree the global communications of Taiwan’s. al. tourism brand is integrated during the current campaign “Tour Taiwan Years. n. iv n C 2008-2009” from the perspective ofhGIMC. By doingU e n g c h i so, two purposes are served. On one hand, the deficiencies of the marketing strategy can be detected and improved in the future. Although Taiwan government has tried to promote Taiwan as an island of tourism since 2000 by proposing “Taiwan’s New Tourism Development Strategies for the 21st Century,” little attention has been paid to the global communications of Taiwan tourism in the academic field. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the current structure of Taiwan’s tourism industry as well as its marketing strategies and executions. In this regard, these analyses can serve as the basis and suggestions for Taiwan’s tourism policy in the future. On the other hand, the current research also tries to bridge the gap in academic 3.

(10) filed by exploring the application of GIMC to tourism destination marketing. Since GIMC is a much newer concept, it receives insufficient discussions either in theory or in practice. Besides, until now there is no research examining country tourism promotions from the perspective of GIMC. Therefore, by conducting a case study on Taiwan’s global promotions of tourism industry, this research also hopes to contribute to the literatures of GIMC.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 4. i Un. v.

(11) 2. Literature Review The literature review in this study is divided into three sections. The first section mainly focuses on the characteristics of tourism industry and how they pose a challenge for tourism destination marketing, in which the branding of tourism destination is also included. In the second section, the past literatures on tourism marketing are examined, especially the global promotions of a tourism destination brand. Thirdly, the framework of GIMC as well as its applicability on destination marketing is proposed.. 立. 學. ‧ 國. 2.1 Tourism industry. 政 治 大. 2.1.1 Definition of Tourism. One of the most enduring definitions of tourism was proposed by Burkart and. ‧. Medlik, who viewed tourism as “the temporary short term movement of people to. y. Nat. io. sit. destinations outside places where they normally live and work, and their activities. n. al. er. during their stay at these destinations (Briggs, 1997, p.3).” More specifically, the. Ch. i Un. v. definition by WTO suggests that tourists are people who “travel to and stay in places. engchi. outside their usual environment for more than twenty-four hours and not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes not related to the exercise of an activity remunerated from within the place visited.” From the above definitions, it is inferred that tourism involves people, time, and space movement from one destination to another. For international tourism, the focus of this study, the destination to go should be a place outside people’s countries. Tourism industry is a multidimensional and comprehensive industry, in which several sectors and organizations are involved. In general, it comprises three main sectors: 1) tourism products suppliers, including accommodations, restaurants, 5.

(12) transportation, and tourist attractions; 2) travel agents and tour operators; and 3) destination marketing organization like National Tourism Office in each country (Tsao, 2001). Since the purpose of this study is to figure out how Taiwan promotes its tourism brand and how these promotions are coordinated across countries, the main focus would be on the third sector, that is, the destination marketing organization of Taiwan—Taiwan Tourism Bureau.. 2.1.2 Characteristics of tourism industry When people choose a destination, actually they are purchasing a “product.”. 治 政 However, this product cannot be seen, touched, or felt 大 as making the purchase 立 decision. This intangibility of tourism product at the time of purchase evaluation and ‧ 國. 學. consumption makes it an experience product (Cai, Feng, and Breiter, 2004). Similarly,. ‧. Tsao (2001) suggested that what tourism provides is more like a service than a. sit. y. Nat. product and indicated that tourism industry contains the characteristics of service. io. er. industry, including intangibility, inseparability (production and consumption must. al. n. exist at the same time), heterogeneity (variability of service quality), and. i n Cstored). perish-ability (products cannot be U hengchi. v. Other than the characteristics of service industry aforementioned, tourism industry also possesses its own uniqueness. Many researchers have pointed out the complexity of destination products and stakeholders involved as the distinction of tourism industry (e.g., Buhalis, 2000; Morgan et al., 2002). Just like what is mentioned before, tourism industry is a multidimensional and comprehensive industry. It is a composite product consisting of different components, including accommodation, tourist attractions, arts, entertainment and cultural venues, and the natural environment (Morgan et al., 2002). Furthermore, Buhalis (2000) categorized all the components involved in tourist destination as six As—attractions, 6.

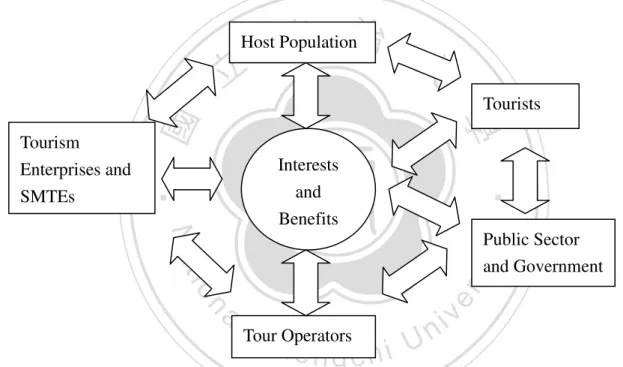

(13) accessibilities, amenities, available packages, activities, and ancillary services3. Therefore, a destination can be regarded as a combination of all products, services and ultimately experiences provided locally. Due to the complexity of destination product, destination marketers have little control over destination marketing because too many stakeholders are involved, including governments, tourism agencies, environmental groups, trade association, and local residents as well as tourists (Morgan et al., 2002). Similarly, Buahlis (2000) proposed a dynamic wheel of tourism stakeholders as illustrated in Figure 2.1.. 政 治 大. Host Population. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Interests and. ‧. Nat. Benefits. io. sit. y. Public Sector and Government. n. al. er. Tourism Enterprises and SMTEs. Tourists. Ch. Tour Operators. engchi. i Un. v. Figure 2.1 The Dynamic Wheel of Tourism Stakeholders Source: Buhalis (2000) With both characteristics in service industry as well as the uniqueness in tourism. 3. Attractions (natural, man-made, artificial, purpose built, heritage, special events). Accessibility (transportation system comprising of routes, terminals and vehicles) Amenities (accommodation and catering facilities, retailing, other tourist services) Available packages (pre-arranged packages by intermediaries and principals) Activities (all activities available at the destination and what consumers will do during their visit) Ancillary services (services used by tourists such as banks, telecommunications, post, newsagents, hospitals, etc.) 7.

(14) industry itself, tourism destination marketing faces several challenges. First of all, the intangibility of tourism products manifests the importance of destination image, especially for the first-time-visitors, who rely totally on second sources to make destination choices. Indeed, it is widely acknowledged by academics and practitioners that destination image does influence people’s perceptions and behaviors related to destination choices (e.g., Kolter et al., 1993). Therefore, Strategic image management (SIM) has been used by many countries to maximize the effectiveness of marketing efforts and also to make sure the images selected and presented are in the strongest possible way (Day et al., 2001). In addition, Gunn (1972) classified images into two. 治 政 types—organic and induced images. Organic images are 大formed from sources like 立 television, books, school lessons or fiends’ experiences, which are not related to the ‧ 國. 學. official tourism information while induced images are derived from the exposure to. ‧. the destination marketers’ promotion efforts such as travel brochures or. y. sit. io. er. Tourism Bureau.. Nat. advertisements. In this study, the focus is on induced images created by Taiwan. al. Another challenge destination marketers have to deal with is the politics- and. n. iv n C image-related problems result fromhthe complexity ofU e n g c h i tourism products as well as the number of stakeholders (Buahlis, 2000; Morgan et al., 2002). It is suggested that destination marketing must satisfy the needs of all stakeholders in terms of supply and demand side. On the supply side, Gunn (2002) indicated that collaboration is essential for successful tourism planning and development, especially the collaboration between public and private organizations. On the demand side, destination marketers have to take into account the heterogeneity of different target groups and design messages based on the core value of the destination but also related to each segments. Both the cooperation of public and private sectors and the creation of a uniform, consistent message pose challenges for destination marketers. 8.

(15) Faced with the characteristics of tourism industry derived from service sector and from tourism itself, IMC seems to be an effective way to solve these problems. According to McArthur and Griffin (1997), different product types demand different communication tools and techniques, and thus the emphasis given by different sectors on the utilization of IMC also vary accordingly. Among all the sectors, IMC seems to be more important within the service context, in which the need to create a consistent and uniform image due to the intangibility of service sector can be accomplished by IMC (e.g., Duncan, 2005; Grove, Carlson, and Dorsch, 2007). On one hand, IMC provides a mechanism that can heighten the tangibility of the service products by. 治 政 coordinating various promotion disciplines (e.g. advertising, 大 direct marketing, sales 立 promotions, etc.) to maintain a clear and consistent message (Nowak and Phelps, ‧ 國. 學. 1994). On the other hand, the databases IMC stresses can also help target the. sit. y. Nat. Schultz, Tannenbaum, and Lauterborn, 1993).. ‧. consumers more effectively and foster customer intimacy (Nowak and Phelps, 1994;. io. er. Therefore, it could be inferred that IMC also serve as an effective means to. al. manage and market tourism destination, in which the need to create consistent image. n. iv n C as in service sector and to deal withhcomplex stakeholder e n g c h i U relationships specifically in tourism marketing may be better addressed by IMC.. 2.1.2 Tourism Destination Branding Due to the complexity of tourism marketing and also the increasing competition caused by globalization, every country has to figure a way to differentiate itself from other global competitors. Other than using IMC in destination marketing as mentioned above, the creation of a destination brand is another way to address these problems. In fact, several researchers agreed that branding is a good start for destination marketing and also a good way to maintain destination image (e.g., Kotler et al., 1999; Morgan 9.

(16) et al., 2002).” Morgan et al (2002) even suggested that “branding is perhaps the most powerful marketing weapon available to contemporary destination marketers confronted by increasing product parity, substitutability and competition (p.336).” Indeed, nowadays the concept of branding is widely accepted for marketing a country other than marketing a consumer product (e.g., Ham, 2001; Kotler and Gertner, 2002). According to The American Marketing Association, a brand refers to “a name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or a combination of them intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competition.” Brand differentiates a product from the others by providing not just the. 治 政 function of the product but also the social and emotional 大values with it, and the values 立 added could be seen as brand equity. This concept can also be applied to the context ‧ 國. 學. for marketing a tourism destination. Morgan et al. (2002) emphasized that the key to. ‧. successful destination is the development of brand saliency, which creates an. sit. y. Nat. emotional link with the potential visitors through campaigns like “I love New York”. io. er. (Baker and Cameron, 2008). Shimp et al. (1993) also applied the concept of “brand. al. n. equity” to “country equity,” referring to the emotional values resulting from. i n Cwith consumers’ association of a brand a country. U hengchi. v. In the past some researchers have done their studies on country brands, among which Anholt (2003) has summarized the related ideas and developed a “Nation Brand Hexagon” as illustrated in Figure 2.2. According to this model, “the nation brand is the sum of people’s perceptions of a country across six areas of national competence, including tourism, export, governance, investment and immigration, culture and heritage, and people (Anholt, 2005, p.297).” Among the six dimensions of the hexagon, tourism is often the most visible promoted aspect of the nation brand. Therefore, compared to other dimensions, the images formed from the tourism promotion of country have a much stronger impact on people’s perceptions toward a 10.

(17) country as a whole (Anholt, 2003). Indeed, Morgan and Pritchard (2005) also pointed out that tourism “supports and leads the development of a place brand by creating celebrity and emotional appeal” which can also contribute significantly to other aspects of the country brand like residents, investors, and the whole country development. However, it should be recognized that tourism brand, although leading the development of the country brand, still should be viewed as part of the country brand.. Tourism. 立. Governance. 學. Nation Brand. Culture and. Investment and Immigration. Figure 2.2 Nation Brand Source: Anholt (2003). n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Heritage. ‧. ‧ 國. People. Export 治 政 大. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Similar to the contribution of IMC, destination branding also echoes and helps address the challenges posed by the characteristics of tourism marketing. In fact, the core of IMC is also for brand building. According to Duncan (2002), “IMC is a process for managing customer relationships that drive brand value.” The objective of IMC is to create and sustain long-term brand relationships by conveying consistent brand messages to the target audiences. Again, this shows IMC may contribute to the context of building tourism destination brand.. 11.

(18) 2.2 Tourism Destination Marketing The past studies on tourism destination marketing mainly focused on three dimensions—destination image, consumer behaviors of tourists, and tourism marketing strategy. Due to the importance of destination image on tourists’ perceptions and behaviors, it has been a widely research subject in the past literatures. Some researchers defined destination images and developed different typologies (Gunn, 1972; Echtner and Ritchie, 1991), others have studied how destination images influence consumer behaviors (e.g., Echtner and Ritchie, 1991; Hanlan and Kelly,. 治 政 2005); and still some on the image selection and management 大 for destination (Day et 立 al., 2001). ‧ 國. 學. Consumer behavior studies in tourism mainly focus on how people search for the. ‧. destination information and how their destination choices are influenced. Several. sit. y. Nat. researches have examined tourism consumer behavior in detail (e.g., Buhalis, 2000;. io. er. Cai, Feng, Breiter, 2004; DiPietro et al., 2007). Specifically in Taiwan, Chen, Jung,. al. and Chen (2004) have studied the purchasing behaviors and revisit intention of. n. iv n C tourists from China. Chan (2006) has the travel experiences of Japanese h eanalyzed ngchi U tourists in Taiwan. Since tourism marketing is a more challenging form of marketing, many researchers have dedicated to the studies on tourism marketing strategy. Several destination brands have been studied by way of case study, including New Zealand (Morgan et al., 2002, 2005), Wales (Morgan and Pritchard, 2005), United Kingdom (Wang, 2005), and Scotland (Page, Steele, and Connell, 2006). In Taiwan, most of the researches on tourism marketing strategy focus on festivals (e.g. Yang, 2005) and place marketing like Kaushiung city (Chen, 2005) or Kenting town (Wu, Chu, and Tsai, 2004) instead of viewing Taiwan as a whole tourism brand. Yu (2007), however, 12.

(19) has done a case study on Taiwan destination brand from the IMC’s perspective, but with more focus on organization than on messages across countries. The review of literatures on tourism marketing reveals that only a few has focused on country as a tourism destination brand and even fewer discussed the coordination of tourism promotions across different countries. Besides, the analysis of the promotion materials from the destination marketer’s point of view is scarce compared to that from the tourist’s side. Therefore, more research on how destination marketers promote their tourism brands on a global scale is needed. Just like what is mentioned above, some researchers have analyzed the global. 治 政 promotions of destination brands like New Zealand, Wales, 大 Scotland, and the United 立 Kingdom and these case studies could serve as the foundation for the current research ‧ 國. 學. For example, Morgan et al. (2002) studied the first ever global branding initiative of. ‧. New Zealand—100 % Pure New Zealand, which was launched from July 1999 to. sit. y. Nat. February 2000. They found out the theme of “100% and purity” is echoed in all the. io. er. visuals and the copy of the promotional materials from global advertising, public. al. relation events, direct marketing, and even websites. They further pointed out that the. n. iv n C conveyed a sense of experiencing award-winning website (www.purenz.com), h e n gwhich chi U the country rather than merely a site encounter, played an important role in the campaign by complementing other advertising, public relations activities and other media. A more recent example of tourism marketing is on how adventure tourism has been promoted in Scotland and the way it has been represented in photographic. images (Page et al., 2006). In this study, the brochures for Scotland produced in 2004 as well as the materials screen-grabbed from the tourism websites are examined. Using the methodology devised by Schellhorn and Perkins (2004) and Dyer (1982), this study content analyzed image’s component parts, which can be further divided 13.

(20) into four elements: products, props, settings, and actors. The result revealed that the imagery was not coherent throughout all areas of Scotland and clearly lack of consistency in the design of each area’s brochure, layout, messages, and images, which resulted from an unclear strategy. From the above two examples, the role of strategy seems to outstand that of execution. It shows that New Zealand successfully coordinated its global promotions across different countries and thus conveyed a consistent themes (100% and pure) through advertising, public relations, or website, although the detailed executions differed. On the other hand, from the case of Scotland, the inconsistency in imagery. 治 政 and messages of the promotional brochures caused by 大 lack of cooperation between 立 public sectors and private sectors also reinforces the need for a clear adventure ‧ 國. 學. tourism strategy. Therefore, it can be inferred that the key success factor of a global. ‧. tourism promotion lies in its coordination of strategy more than of execution. As long. sit. y. Nat. as the execution revolves around the core idea of the campaign, synergies can be. io. er. achieved and strong, consistent massages can be created. Indeed, this concept seems. al. to correspond to what Therkelsen (2003) found a “glocal approach” employed by. n. iv n C Danish Tourist Board when examining branding strategy in 2000. He h eitsnnational gchi U. argued that certain meaning and images can be shared across cultures while some only understood by a certain group of people. Therefore, a glocal approach can help destination marketers gain the advantage of economies of scale by standardizing some universal images as a global platform which conveys a consistent, recognizable identity for the destination, but meanwhile allow room for local adaptation for different markets. Again, what matters for an effective global promotion of a destination is strategy rather than execution. In sum, the review of these former studies reveals that only a few treat countries as destination brands on a global scale, among which some focus only on one of the 14.

(21) marketing communication tools (most of them on global advertising) or on the demand side rather than from the destination marketers’ point of view. Besides, none of them uses IMC as the theoretical foundation to examine tourism destination marketing. Given the above reasons, it is adequate to combine IMC with tourism destination marketing to fill the academic gap in both fields. Furthermore, to better examine the global communications of Taiwan tourism brand, the current research decide to use GIMC proposed by Grein and Gould (1996) as the theoretical framework. In the following section, GIMC will be further illustrated.. 2.3 GIMC. 立. 2.3.1 Definition. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. The concept of Globally Integrated Marketing Communication (GIMC),. ‧. proposed by Grein and Gould in 1996, is the modified extension of Integrated. sit. y. Nat. Marketing Communication (IMC). It combines IMC with the theories of international. io. er. marketing to explain global communications of multinational corporation companies.. al. n. GIMC contains not only the coordination of promotion disciplines as in IMC but also. C hacross countries. U n i further emphasizes the coordination engchi. v. Before going further to GIMC, we need to look back at IMC from which it is developed first. According to American Association of Advertising Agencies’ Integrated Communications Committee, IMC is “A concept of marketing communications planning that recognizes the added value in a program that integrates a variety of strategic disciplines” (see Gould, Lerman, & Grein, 1999, p.8). The purpose of IMC is to coordinate all of the communication disciplines (i.e. advertising, sales promotions, public relations, etc.) so that synergies can be achieved and to ensure that consistent messages reach the target audience (Novak and Phelps, 1994). Synergy refers to “an interaction of individual parts that results in the whole 15.

(22) being greater than the sum of those parts (Duncan, 2002).” However, Duncan further pointed out that in order to achieve synergy, a company must integrate more than marketing communications, such as relationships with employees and customers. Therefore, he defined IMC as “a cross-functional process for creating and nourishing profitable relationships with customers and other stakeholders by strategically controlling and influencing all messages sent to these groups and encouraging data-driven, purposeful dialogue with them (p.8).” Since a company faces various customer segments and stakeholders, a consistent “one voice, one look” message may not be able to be used and well-connected to multiple audiences. Thus, some scholars. 治 政 propose “strategic consistency,” which means that different 大 messages can be made for 立 various target audiences but the big brand image remains constant. In this way, ‧ 國. 學. synergies can still be created even though multiple audiences are targeted and. ‧. different executions are used (Duncan, 2002; Novak and Phelps, 1994). Actually, this. sit. y. Nat. is similar to what Therkelsen (2003) called “glocal approach” mentioned above.. io. al. er. The concept and practice of IMC has been widely discussed in the past. n. literatures, and generally three levels of integration are proposed (Novak and Phelps, 1994):. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 1) One Voice Marketing Communication This view emphasizes the creation of one single theme and image. In other words, all advertising, sales promotions, public relations, direct marketing convey the same brand image and identity. 2) Integrated Communication This view suggests that marketing communications should simultaneously establish an image which directly influences consumer behavior. Under this perspective, all marketing communications are not exclusive but integrated to achieve both communication and behavioral objectives. 16.

(23) 3) Coordinated Marketing Communication Campaigns This view stresses the need to coordinate activities of different marketing communications. Unlike “one voice” strategy, the coordinated communications are not necessarily based on single theme or unifying brand positioning when delivering to multiple audiences. In addition, this perspective corresponds to the American Association of Advertising Agencies’ definition as well as Duncan’s. In defining GIMC, Grein and Gould (1996) suggested that the first and third definitions listed above seem more applicable because both two can be applied to the international setting, that is, standardization and adaptation, the major aspects of. 治 政 international marketing strategy. Both one voice and coordinated 大 communications can 立 be applied to the standardized strategy, which tries to create a uniform image in all ‧ 國. 學. markets. However, the coordinated communication in particular applies to the. ‧. adaptive strategy since synergies can still be attained in messages to multiple. sit. y. Nat. audiences while one-voice communication may not work in all markets. This suggests. io. er. that coordinated communication applies to not only one-voice, standardized strategy. al. but also adaptive strategy. Therefore, Grein and Gould (1996) proposed that the third. n. iv n C definition should dominate the first,hindicating that either e n g c h i U standardization or. adaptation can be viewed as integrated strategy as long as through which synergies can be created. Wind (1986) had the similar idea, pointing out that synergies are not just limited to standardized strategy but may also be achieved through “non-standardized but integrated strategies.” Thus, GIMC strategy follows what Wind (1986) described as “Think globally, act locally.” The core idea of GIMC is that it contains both vertical and horizontal dimensions (Tortorici, 1991). Vertical integration involves coordination of different marketing disciplines (i.e. advertising, public relations, sales promotions, etc.), which are the basis of IMC. The major difference between IMC and GIMC lies in their focus on 17.

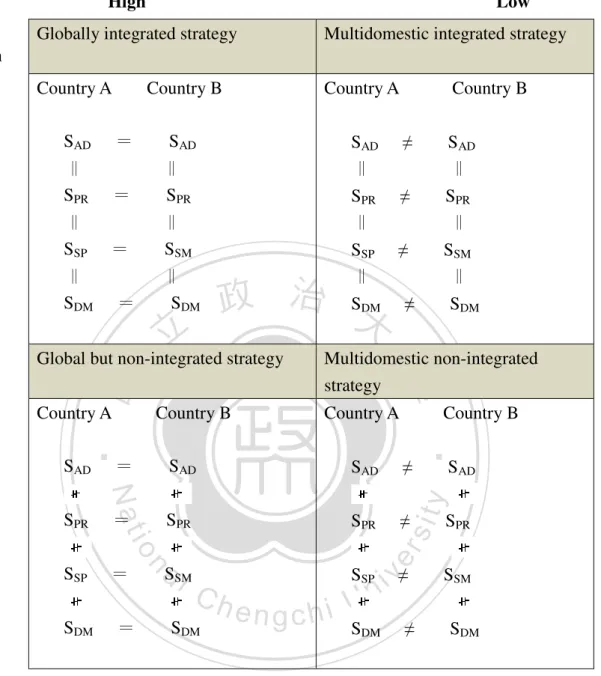

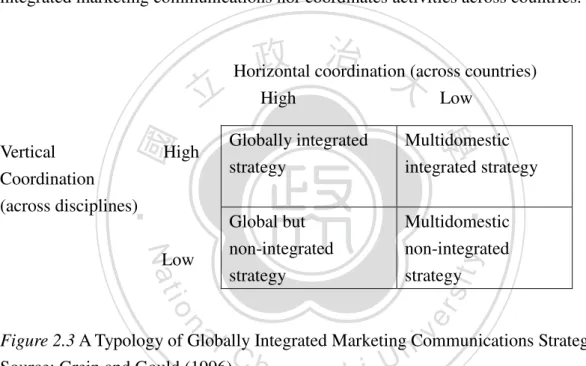

(24) horizontal dimension. In GIMC, horizontal integration concerns coordination of communications not only across divisions of organizations as in IMC but also across countries (Grein and Gould, 1996). Simply put, the linkages across countries are further examined and emphasized by GIMC. Based on this view, Grein and Gould (1996) defined GIMC as: “……a system of active promotional management which strategically coordinates global communications in all of its component parts both horizontally in terms of countries and organizations and vertically in terms of promotion disciplines. It contingently takes into account the full range of standardized versus adaptive. 治 政 market options, synergies, variations among target populations 大 and other 立 market-place and business conditions (p.143).” ‧ 國. 學. In addition, Grein and Gould (1996) also suggested that GIMC takes a. ‧. contingency approach to global promotion, and thus the degree of standardization for. sit. y. Nat. promotion depends on many factors within and outside the companies such as the. io. er. firm’s international experiences, the nature of the products, or the competitors’. al. strategies (Cavusgil et al., 1993). Based on Jain’s (1989) research, Grein and Gould. n. iv n C (1996) categorized these factors into 1) horizontal factors which include hthree e n types: gchi U target audience, market position, nature of the product, and the environment; 2) organization factors like agency-client relationship, agency structure, and individual managerial differences; and 3) vertical factors including marketing mix and overall promotion like advertising, sales promotion, and public relations. Influenced by factors outside and within companies, the level of coordination and integration varies both horizontally and vertically. In general, international communications strategies fall into four categories as shown in Figure 2.3. Companies with high level of coordination across promotion disciplines and countries are following a globally integrated strategy. The second possibility is a multidomestic 18.

(25) integrated strategy, which involves integrated promotion disciplines within a country but not coordinates strategies across countries. The third possibility is a global but non-integrated strategy, which suggests that a firm coordinates its global strategy without integrating the marketing communications within a country. An example would be a firm decide to standardize its advertising worldwide but fails to coordinate the advertising with public relations, sales of promotions, etc. The fourth one is multidomestic non-integrated strategy. A Company using this strategy neither uses integrated marketing communications nor coordinates activities across countries.. io. Global but non-integrated strategy. Multidomestic non-integrated strategy. n. al. Multidomestic integrated strategy. y. sit. Nat. Low. Globally integrated strategy. er. High. ‧. Vertical Coordination (across disciplines). 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. Horizontal coordination (across countries) High Low. i Un. v. Figure 2.3 A Typology of Globally Integrated Marketing Communications Strategies Source: Grein and Gould (1996). Ch. engchi. Although Grein and Gould (1996) has pointed out that either standardization or adaptation could be considered as a globally integrated strategy, and the degree of standardization depends on several internal and external factors, they didn’t specify the criterion for distinguishing standardized strategy from the adaptive one. This causes confusion when people come to decide whether a strategy is of high coordination or low coordination since the concept of standardization and adaptation is not clear. What determines the degree to which a strategy can be viewed as coordinated should be specified so that the model of GIMC can be put into practice. 19.

(26) Therefore, to fill out this gap, in the following section the research includes the discussion related to standardization versus adaptation in the past literatures.. 2.3.2 Standardization vs. Adaptation 2.3.2.1 Advertising The debate between standardization and adaptation in international marketing has been going on for more than four decades without a consensus. The issue of standardization was first raised by Elinder in 1961 with reference to adverting (Jain, 1989) and until now advertising continues to be the focus in this field. There are three. 政 治 大. basic approaches to global adverting—standardization, adaptation, and a combination. 立. of both (compromise school and contingency perspective) (Kanso, 1992; Onkvisit and. ‧ 國. 學. Shaw, 1990). They are as follows: 1) Standardization. ‧. According to Levitt (1983), standardization is defined as “selling the same. y. Nat. io. sit. product the same way everywhere.” Advocates of standardization assume that. n. al. er. markets are converging and consumers around the world are becoming homogenized. Ch. i Un. v. due to technology and increased communication (Levitt, 1983). They believe the. engchi. basic human physiological and psychological needs are still the same. Thus, advertising campaigns can be successfully transferred to another country and that standardized themes can create unified brand images worldwide. The benefits of employing standardization in advertising are many. The two major ones are cost savings and consistent brand image (Melewar and Vermmervik, 2004). By standardizing advertising worldwide, costs are reduced for economics of scale. It also helps convey consistent and uniform image worldwide so that brand recognition is built. Other advantages include sharing of successful experiences and simplified planning, coordination, and control for organizations (Buzzel, 1968; Kanya, 2000). 20.

(27) Duncan and Ramparasad (1995) also found that single brand image is the main reason for multinational companies to employ standardized advertising. 2) Adaptation Proponents of adaptation posses the opposite view to standardization, arguing that cultural differences do exist and contradicting Levitt’s (1983) propositions of homogenization of markets and consumers. Other than cultural differences, there are still many factors that prevent standardization from working successfully and effectively, such as different economic development, political and legal system, technological environment, and consumer values and lifestyles (e.g., Boddewyn et al.,. 治 政 1986; Cavusgi et al., 1993). Due to these differences, it大 is necessary develop adaptive 立 advertising. ‧ 國. 學. 3) Compromise. ‧. Unlike the extreme approaches of standardization and adaption possess,. sit. y. Nat. compromise school propose a contingency point that views standardization versus. io. er. adaptation as a continuum. Proponents of this school recognize local differences but. al. also to some degree believe advertising standardization is possible and desirable. n. iv n C (Onkvisit and Shaw, 1990). Thus, global can fall anywhere on a spectrum h e nadvertising gchi U form totally standardized to totally localized (Moriarty and Duncan, 1991).The degree to which the companies take standardized or adaptive approach depends on the situation. Such strategy, somewhere between complete standardization and adaptation, makes this school a contingency approach to global advertising. However, the definition of a standardized advertisement remains unresolved. Some take more strict approach, saying that an advertisement is global only if it is unchanged in all countries except for translation (Onkvisit and Shaw, 1990). On the other hand, some take more flexible position like Harries and Attour (2003), who suggested that standardization can be adapted to market conditions. Melewar and 21.

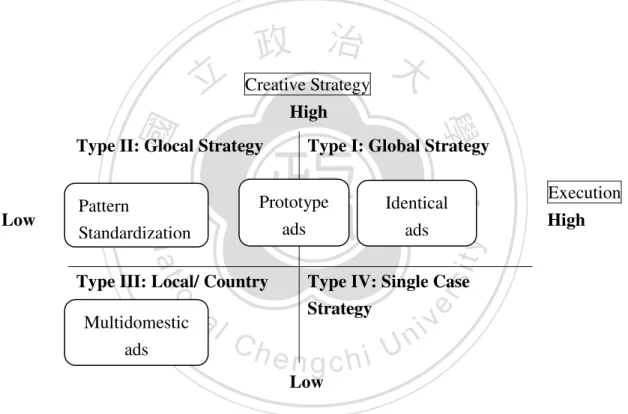

(28) Vemmervik (2004) reviewed the former literatures and concluded that the visual element (picture) seems to be the most important elements from a standardization perspective. Melewar and Vemmervik (2004) also pointed out that a corporation can standardize the market strategy (i.e. advertising objectives, target segment and position, final market decision, etc.), but it doesn’t mean that tactics (i.e. advertising themes, market layout, media selection, etc.) must be standardized. This is similar to Duncan and Ramparasad’s (1995) definition of standardization, which is “keeping one or more than the three basic components of multinational advertising. 治 政 campaign—strategy, execution, and language”—the same. 大 In their study, strategy is 立 the creative selling proposition, and execution refers to actual elements and their ‧ 國. 學. structure in ads. Language is considered a separate element because there are. ‧. situations when all executional elements of a multinational ad are standardized except. sit. y. Nat. the language. They found that creative strategy was often standardized in. io. er. multinational advertising campaigns, while execution was only sometimes. al. standardized, and language and nationality were rarely standardized.. n. iv n C Based on Duncan and Ramaprasad’s (1995), Wei and Jiang (2005) h e nwork gchi U. proposed a model of international advertising strategies focusing on two dimensions of standardization: creative strategy and execution. Here creative strategy refers to “a policy or guiding principle that specifies the general nature and character of message to be designed.” On the other hand, execution is defined as “a selection of advertising appeals, copy, and illustrations to execute the chosen creative strategy.” Different combinations of strategies and execution suggest four categories: global strategy, glocal strategy, local/ country specific strategy, and single case strategy as shown in Figure 2.4.. 22.

(29) Creative Strategy High Type II: Glocal Strategy Highly Standardized Strategy Adapted Execution Low Type III: Local/ Country Specific Strategy Adapted Strategy Adapted Execution. Type I: Global Strategy Highly Standardized Strategy Highly Standardized Execition. High. Type IV: Single Case Strategy Adapted Strategy Highly Standardized Execution. Low. Execution. 政 治 大. Figure 2.4 A Model of Dynamics between Standardization in Creative Strategy and in Execution Source: Wei and Jiang (2005). 立. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. 1) Global strategy. sit. y. Nat. A global strategy refers to advertising which is highly standardized in both. io. er. creative strategy and execution in all markets. Advertising messages including themes,. al. positioning, illustrations, and copy remain unchanged, except for the translation. n. iv n C needed. Simply put, this is “one voice, look” for a global market. However, a h eone ngchi U research done by Hite and Fraser in 1988 indicated that only 10% of U.S. companies adopted this strategy worldwide (Wei and Jiang, 2005). 2) Glocal strategy A glocal strategy highly standardizes the creative strategy but leaves room for adaptation in execution. The term “glocalization,” which combines globalization and localization, identifies the spirit of “think globally, act locally.” According to Hite and Fraser (1988), the majority (54%) of U.S. companies pursued a glocal strategy. 3) Local/ Country Specific Strategy Local/ country specific strategy represents that both creative strategy and 23.

(30) execution are adapted to the local market. This strategy, exactly the opposite of global strategy, employs “one voice for each market” and takes cross-cultural differences into considerations. In Hite and Feaser’s (1988) study, about 34% of U.S. companies used local/ country strategy. 4) Single Case Strategy Single case strategy localized the creative strategy but standardized the execution. Wei and Jiang (2005) pointed out that his strategy is a special case and rarely used in real practice. Thus, it was excluded from their study. Wei and Jiang (2005) used this model of global advertising strategies to. 治 政 examine Nokia’s advertising campaigns in U.S. and China, 大 and found a glocal 立 strategy was employed. They pointed out that culture is a key external factor that ‧ 國. 學. influences the degrees of standardization at the strategy and execution levels.. ‧. Furthermore, the result also showed that culture seems to have a greater impact on. sit. y. Nat. execution than on creative strategies, which also echoes the former research proposing. io. al. Duncan and Ramaprasad, 1995; Tai, 1997).. er. that strategic decisions are more likely to be standardized than tactical decisions (e.g.,. n. iv n C Johansson (2002) also suggested the best strategy is often to start with a h ethat ngchi U. basic creative concept that has proved successful in a leading market, and then allow local managers to adapt the theme to local markets and local media. He divided international advertising into global advertising and multidomestic advertising. According to Johansson, global advertising is more or less uniform across many countries, often, but not necessarily, in media vehicles with global reach while multidomestic advertising is international advertising deliberately adapted to particular markets and audiences in message and/or creative execution. He specifically categorized global advertising into three types: 1) Identical ads, in which only language voiceover is changed and copy translation is added while the overall 24.

(31) structure remains the same; 2) Prototype ads, in which the voiceover and the visual may be changed to avoid language and cultural problems; the ads may also be reshot with local spokespeople but still using the same visualization; 3) Pattern standardization, in which the positioning theme is unified but the actual execution of the ads differs between markets. Among the three types, Johansson (2002) suggested that pattern standardization has become the most common approach among practitioners since it employs a unified positioning theme but still allows creativity flexibility at the local level.. 立. 政 治 大. Creative Strategy. Prototype. Identical. ads. ads. n. al. ads. Type IV: Single Case Strategy. er. io. Type III: Local/ Country Multidomestic. High. y. Nat. Standardization. Execution. sit. Low. Pattern. Type I: Global Strategy. ‧. ‧ 國. Type II: Glocal Strategy. 學. High. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Low. Figure 2.5 Combination of Wei and Jiang’s model and Johnssan’s typology of global advertising. Compared Wei and Jiang’s model of international advertising strategy with Johansson’s typology, we can see that the former focuses more on the structure of standardized strategy while the latter goes deeper to executions of standardization. Both two help us develop a clearer picture toward what and how global advertising means and represents. As shown in Figure 2.5, identical ads fall into the quadrant of 25.

(32) global strategy; prototype ads and pattern standardization into the quadrant of glocal strategy, with prototype ads closer to the global strategy since they have the same visualization. What is in common is that they all view standardization versus adaptation as a continuum instead of an either/or question, and they determine the degrees of standardization based on the same criterion—strategy and execution (tactics). What’s more, the role of strategy seems more important than executions when distinguishing whether the ads are standardized or not. As long as the strategy remains the same, the ads can be viewed global, belonging to either global or glocal strategy.. 治 政 Although the discussion related to standardization大 and adaptation mainly focuses 立 on advertising field, some scholars also tried to apply them to other marketing ‧ 國. 學. communications like public relations, sales promotions and direct marketing. The. Nat. y. ‧. following sections provide the summaries of these researches.. io. sit. 2.3.2.2 Public Relations (PR). n. al. er. The role of public relations is to use communication to build relations with. Ch. i Un. v. strategic publics that shape and constrain the mission of the organizations (Grunig et. engchi. al., 1995). The debate on whether public relations can be global and practiced in different countries is similar to the debate between standardization and adaption in advertising. Public relations scholars who possess ethnocentric perspectives have argued that public relations practices should be no different from their own culture (e.g., Illman, 1980). On the other hand, scholars who maintain polycentric perspectives have argued that public relations practice should vary from country to country (e.g., Botan 1992; Huang, 1997). Therefore, some scholars proposed the middle-road approach suggesting that the ideal model for international PR lies somewhere in between (Vercic, J. Grunig, and L. 26.

(33) Grunig, 1996). They argued that effective public relations share 10 generic principles4 across cultures even though the specific variables (e.g., political system, economic system, culture, extent of activism, level of development, and media system) should be taken into consideration when being applied in different nations (Rhee, 2002). The global public relations theory has been examined in the former researches and those generic principles are found to be applicable in other countries (e.g., L. Grunig, J Grunig, and Vercic, 1998; Kaur, 1997; and Huang, 1997). Similarly, Anderson (1989) took a flexible approach, defining global public relations as “an overall perspective on a program executed in two or more national markets and recognizes the. 治 政 similarities among audiences while necessarily adapting 大to regional differences 立 (p.413).” ‧ 國. 學. Witnessing the wide discussion on advertising concerning globalization, Ovaitt. ‧. (1988) suggested that PR people can learn from the experiences of global marketing. sit. y. Nat. and advertising, although PR is arguably more culturally bound than either two. One. io. er. of the most important lessons stated by Ovaitt (1988) is that whether the company. al. pursues a high degree of program standardization or not, the benefit of standardizing. n. iv n C management process and planning h systems around theUworld can be expected such as engchi international transfer of skills or sharing of inspirations. He pointed out that there have been more and more PR managers recognize this concept and try to implement certain basics for their practices worldwide. Although few researches have discussed the standardization and adaption of the 4. 1. PR is involved in strategic management. 2. PR is empowered by dominant coalition or by a direct reporting relationship to senior management. 3. PR function is an integrated one. 4. PR is a management function separate from other functions. 5. PR unit is headed by a manager rather than a technician. 6. The two-way symmetrical model of PR is used. 7. A symmetrical system of internal communication is used. 8. Knowledge potential for managerial role and symmetrical PR. 9. Diversity is embodied in all roles. 10. An organization context exists for excellence. 27.

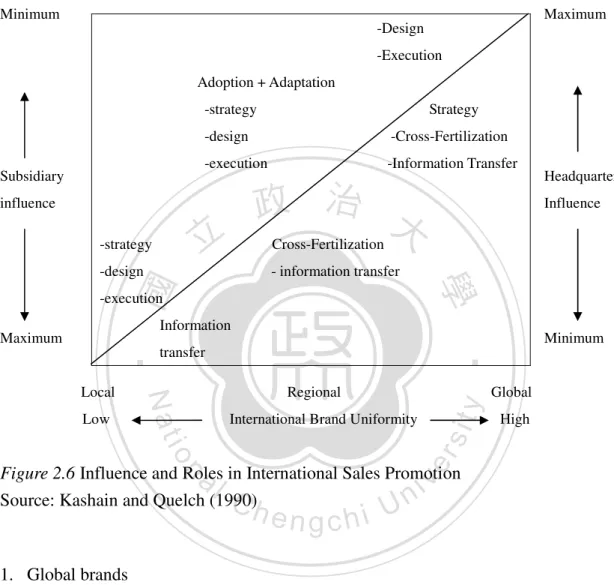

(34) public relations, it is inferred that some principles can be standardized while some should be kept local. Ovaitt (1988) proposed that the public relations, like advertising, can also view standardization versus adaptation as a continuum and thus a global PR program needs not be highly controlled without any room for local creativity. He also pointed out that the strategies of the public relations can be shared and implemented in different ways in different cultures, which seems to correspond to the glocal strategy discussed in the previous section—standardization of strategy and the adaptation of execution. Therefore, the current research would suggest that public relations, similar to advertising context, can also be examined from two main. 治 政 aspects—strategy and execution. As long as the main theme 大 of the PR program 立 remains the same worldwide, it can be counted as a global PR activity despite how it ‧. ‧ 國. 學. is executed.. 2.3.2.3 Sales Promotion. y. Nat. io. sit. Traditionally sales promotion has been considered as a local activity because the. n. al. er. purpose of sales promotion is to “motivate local consumers and members of the trade. Ch. i Un. v. to act—to try the product, repurchase it, buy more, switch brands, and so forth. engchi. (Kashani and Quelch, 1990, p. 38).” Economic development, market maturity, regulations and laws, and people’s perceptions toward promotional incentives vary from country to country and these are all factors that keep sales promotion a relatively local affair. However, with the increasing costs and complexity of sales promotions worldwide, and the trend of establishing uniform brand images, managers in multinational corporations companies start to consider the possibility of employing a standardized strategy in all markets (Kashani and Quelch, 1990). Despite the debate of keeping sales promotion either a local activity or a more standardized strategy, Kashain and Quelch (1990) proposed a contingency approach, 28.

(35) suggesting that the degree of coordination across countries depends on whether the brand is local, regional, or global. As shown in Figure 2.6, three possible scenarios in international sales promotion are proposed.. Minimum. Maximum -Design -Execution Adoption + Adaptation -strategy. Subsidiary. -design. -Cross-Fertilization. -execution. -Information Transfer. 政 治 大. influence. 立. -strategy. Strategy. Influence. Cross-Fertilization. ‧ 國. - information transfer. 學. -design. -execution. Information. transfer. io. al. y. sit. International Brand Uniformity. Global High. er. Low. Regional. Nat. Local. Minimum. ‧. Maximum. Headquarter. v. n. Figure 2.6 Influence and Roles in International Sales Promotion Source: Kashain and Quelch (1990). Ch. engchi. i Un. 1. Global brands When the brand is positioned as a global brand, the influence of headquarter is the largest and thus standardized strategy is often used. The headquarters here are responsible for developing an overall promotional strategy to guide the general activities of local management. These guidelines help protect the integrity of the brand across different markets and convey a consistent message to consumers worldwide. However, it is emphasized that the promotion designs and executions are still better left for the local government even though headquarter decides the strategy. 29.

(36) 2. Regional brands The overall objective of regional brands is to create brand harmonization instead of standardization, and thus it is more like adaptive approach. The role of center is to help cross-fertilization across countries while the country managers are responsible for handling adoption and adaption to see what should be adopted from the region and how they are adapted to local condition. 3. Local brands With local brands the degree of local influence on promotional decisions is at its maximum, and the need for central coordination is nonexistent. The center’s task for. 治 政 the local brands is simply information transfer. All the 大 promotion strategy and 立 executions are left for the local government. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 2.3.2.4 Direct Marketing. According to Direct Marketing Association (DMA), the definition of direct. y. Nat. io. sit. marketing is “an interactive system of marketing which uses one or more advertising. n. al. er. media to affect a measurable response and/or transaction at any location.” The. Ch. i Un. v. basics practices of direct marketing include catalogues, direct mails, telemarketing,. engchi. and so on. Because of the nature of itself, direct marketing has been considered traditional and nationalistic (Shultz, 1994; Spiller and Cambell, 1994). Direct marketing relies on lists, postal services, and some types of financial payments, which requires an understanding of local market and thus everything is supposed to be tailored to specific target audience. However, due to the development of technology like Internet databases, efficient postal services, growing use of credit cards, and quick transportation and delivery services, direct marketing is growing fast as a global market (Light and Somasundaram, 1994; Mehta, Grewal, Sivadas, 1996; Shultz, 1994). 30.

(37) Topol and Sherman (1994) conducted a research on how firms developed their direct marketing strategy when entering another foreign country and found that the majority of firms (80%) would like to modify their direct marketing strategy, among which only 6% plan to launch a whole new strategy. Only 20% would like to follow the original strategy in another country. This suggests that international firms prefer adaptive strategy to standardized strategy when employing direct marketing in another country. Furthermore, the research also showed that catalogues (43%) and direct mails (41%) would be the most popular means when expending their businesses, followed by foreign distributors (33%), direct selling (23%), print (13%), telemarketing (11%),. 治 政 and magazines (10%). The emphasis on cooperating with 大foreign distributors also 立 implied the need for direct marketers to understand the local market. ‧ 國. 學. As what is mentioned above, communication technology has made direct. ‧. marketing become a global business. Shultz (1994) called the new communication. sit. y. Nat. technology as “information superhighway,” built up by Internet, satellite, and cable. io. er. system, and it has gradually changed direct marketing into a global concept as well as. al. a global activity. He further suggested that the biggest change of direct marketing. n. iv n C would be from “outbound to interactive.” past, direct marketers sent out the h e nIngthe chi U information by mails or telephones and then passively waited for the consumers to reply, which were one-way, outbound communication. However, technology like online databases can help direct marketer easier target the prospects, get consumer insights, and interact with them. In addition, products and services are available on the Internet so that consumers worldwide can have purchases whenever they want, not when the marketers want to sell. In this way, the process has become two-way and interactive communication. On the other hand, it also helps overcome the barriers for direct marketers like entering a foreign country (Mehta et al., 1996). From the former literatures, we can see that communication technology has made 31.

(38) direct marketing, which used to be local and national, to become global. However, the adaptive strategy seems to be more applicable because of the nature of direct marketing itself. Since not many researchers have focused on the global strategy of direct marketing, it is not easy to specify what a standardized or adaptive direct marketing strategy is. Nevertheless, through the research done by Topol and Sherman (1994), one thing is sure that some parts of the direct marketing can be standardized while some have to be adaptive when the firms enter another country. In addition, these firms also reported that the idea of “think globally, act locally” was practiced in their direct marketing strategies, suggesting the use of a glocal approach as mentioned. 治 政 in other communication tools. Therefore, the current research 大 suggests that the same 立 criterion, strategy and execution, used in advertising and other promotion disciplines ‧ 國. 學. to decide whether they are globally coordinated may also work in direct marketing as. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Summary. ‧. well.. al. The review of the past literatures on standardization seems to suggest that. n. iv n C strategy versus execution can servehas an appropriate U e n g c h i criterion to distinguish the. degree to which the promotion disciplines (i.e. advertising, public relations, sales promotion, and direct marketing) are coordinated on a global basis. However, Duncan (2002) proposed that when doing IMC planning, many strategies need to be considered, including “message strategy,” “creative strategy,” “media strategy,” and “promotional strategy,” so which strategy is to be examined in this study? Since the current research tries to analyze the coordination of all marketing communication tools instead of comparing only one discipline, “message strategy” seems to be more applicable than the others. Furthermore, the concept of “strategically consistency” in message strategy pointed out by Duncan (2002), which suggests that consistent brand 32.

(39) image as well as the core value of the brand is maintained even when different messages are delivered to various target audiences, also supports the idea that position of strategy outstands executions as inferred in the past literatures discussed above. In fact, this corresponds to the concept of GIMC in which either standardized or adaptive approach can be seen as a coordinated strategy as long as synergy can be created. Therefore, the current research suggests that message strategy is the main element which determines whether the promotion disciplines are globally coordinated or not. That is to say, as long as the brand image reflected from the strategy in all promotion disciplines is standardized across countries, it could be considered as a globally. 治 政 integrated campaign even though the execution varies 大 across countries. 立 Based on this idea, the modified framework of GIMC is proposed and shown in ‧ 國. 學. Figure 2.7. Supposed that a firm is going to enter country A and B, a globally. ‧. integrated strategy would be to coordinate all the strategy across all the promotion. sit. y. Nat. disciplines as well as across countries. Secondly, if the firm only coordinates the. io. er. strategy across promotion disciplines in a single country but without coordinating. al. them across countries, then it would be a multidomestic integrated strategy. The third. n. iv n C possibility would be global but non-integrated in which the firm employs the h e n g cstrategy, hi U uniform strategy in country A and B but does not coordinate the strategy across promotion disciplines. Lastly, mulitdomestic non-integrated strategy would be that in country A and B different strategies are employed and they are not coordinated across promotion disciplines within a country. It should be emphasized again that only strategy is taken into account while deciding whether the marketing activities are coordinated or not.. 33.

(40) Horizontal coordination (across countries) High. Low. Globally integrated strategy. Multidomestic integrated strategy. Country A. Country B. Country A. SAD. SAD. ≠. SAD. SPR. SPR. ≠. SPR. SSM. SSP. ≠. SSM. High. SAD. =. SPR. =. SSP. =. ∥ ∥. ∥ ∥. ∥. ∥. =. SDM. ∥ ∥. SDM. 立. 政 治 S大. Global but non-integrated strategy. ∥. SDM. Multidomestic non-integrated strategy Country A. Country B. SAD. SAD. ≠. SPR. SPR. SPR. ≠. SSP. =. n. Ch. SDM. i Un SSP. engchi. sit. io. aSSM l. er. =. SAD. y. =. ‧. ‧ 國. Country B. SAD. =. ∥. 學. Country A. SDM. ∥. ≠. DM. Nat. Vertical Coordination (across disciplines). ∥. Country B. v≠. SDM. ≠. Low. Figure 2.7 Modified GIMC typology Source: Adapted from Grein and Gould (1996) Note: SAD : Message Strategy of Advertising; SPR : Strategy of Public Relations SSP : Message Strategy of Sales Promotion; SDM : Strategy of Direct Marketing. 34. SPR. SSM SDM.

(41) Based on this modified GIMC framework, the research question is proposed:. RQ1: From the point of view of GIMC, what marketing strategy is Taiwan Tourism Bureau employing to build Taiwan Tourism Brand during “Tour Taiwan Years 2008-2009?” RQ1-a: How well does each market integrate the marketing communication tools (i.e., vertical integration)? RQ 1-b: How well do the countries within and across region(s) integrate the marketing communication tools (i.e., horizontal integration)?. 立. 政 治 大. In addition, the past literatures also revealed that different elements in promotion. ‧ 國. 學. mix involve different level of standardization (Moriarty and Duncan, 1991; Birnik and. ‧. Bowman, 2007). Some elements are easier to standardize while some are not. For. sit. y. Nat. example, advertising, compared to sales promotion, is closer to the standardized end. io. er. of the spectrum (Boddewyn and Grosse 1995; Moriarty and Duncan, 1991). However,. al. no research has focused on other communication tools like public relations and direct. n. iv n C marketing, which have been considered as more localU activities. Therefore, based on hen gchi the former literatures, the current research proposes that sales promotion, public relations, and direct marketing, compared to advertising, are more difficult to standardize as shown in Figure 2.8. By examining the international promotion strategy of Taiwan tourism, the research questions can also be tested.. 35.

(42) RQ2: Are public relations, sales promotions, and direct marketing more difficult to standardize worldwide than advertising in the case of Taiwan Tourism Brand?. Easier ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- more difficult Sales Promotions. Advertising. Public Relations Direct marketing. 政 治 大. Figure 2.8 Standardization Spectrum Source: Adapted from Moriarty and Duncan (1991). 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 36. i Un. v.

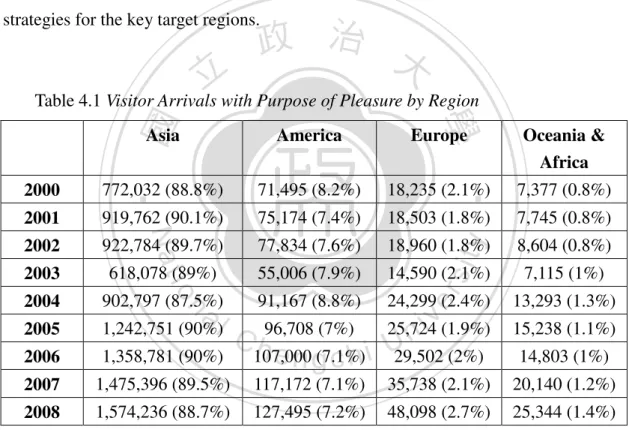

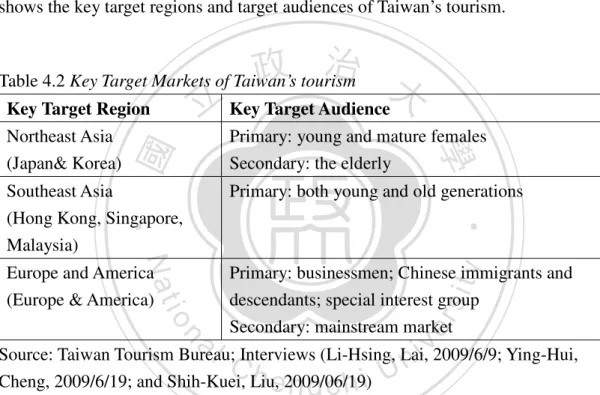

數據

相關文件

Resources for the TEKLA curriculum at Junior Secondary Topic 2 Marketing Mix Strategies and Management – Extension Learning Element1. Module

Topic BAFS Elective Part - Business Management Module – Marketing Management M09: Marketing Strategies for Goods – Marketing Mix.. Level S5

BAFS Learning and Teaching Example As at April 2009 The marketing promotional plan objective is to expand the local business into the North American market. Step 1:

To explore different e-learning resources and strategies that can be used to successfully develop the language skills of students with special educational needs in the

Explore different e-learning resources and strategies that can be used to successfully develop the language skills of students with special educational needs in the..

Biases in Pricing Continuously Monitored Options with Monte Carlo (continued).. • If all of the sampled prices are below the barrier, this sample path pays max(S(t n ) −

地方觀光文化產業,係以地方特色作為「地方行銷」的賣點,各國基於觀光

As a result banks should be so proactive as if they are doing the marketing job to make their employees feel the importance of internal marketing, who can only in