國立交通大學

英語教學研究所碩士論文

A Master Thesis

Presented to

Institute of TESOL,

National Chiao Tung University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of

Master of Arts

阿拉伯人與美國人問候用語之探討

“Hello” or “Salaam?” Greetings by Arabs and Americans

研究生:美麗克

Graduate: Malak Ismail Kirdasi

指導教授:鄭維容

Advisor: Dr. Stephanie W. Cheng

Abstract

Greetings are often people's first impressions of one another; therefore, learning how to greet someone appropriately is important in making a good first impression and avoiding pragmatic failures. Many studies have been conducted on the speech act of greetings, and greetings in different cultures. However, very few numbers have been examined the relationship between the contextual variables (e.g., gender and social distance) and greeting strategies. Moreover, while previous researches have been done on Arabs greeting strategies or Americans greetings strategies, no previous study put Arabs and Americans greetings in comparison.

This study aims to compare between greeting strategies used by Arabs and Americans in terms of oral speech and body language. In addition, some contextual variables, such as gender, social distance, and situations have been put into test in order to examine to what extent these variables could influence the use of greeting strategies.

Three different data collection methods have been used in the purpose of achieving the goals of the study. The first one was the natural observation of some occasions and gatherings, where people naturally tend to use greeting strategies. The second data collection method was using the DCT questionnaire, which included 6 situations with different variables. A total of 60 participants of both Arabs and Americans group took part in the questionnaire. Afterwards, an interview with 18 participants, from both groups, has been held to understand the participant's perceptions about greeting strategies.

The results showed that both Arabs and Americans used oral speech strategies more than body language in greetings. However, Americans tended to use more oral speech than Arabs in general, and Arabs used more body language strategies than Americans. The results also showed

the differences in the greeting’s patterns used by Arabs and Americans in both oral speech and body language. While Arabs mostly used the routine greeting strategies, Americans tended to use variety of strategies and language. However, according to their culture, Arabs used many body language strategies, in which, some of them Americans avoided to use.

Overall, the number and the use of greeting strategies differed between Arabs and Americans. Moreover, the contextual variables, such as gender, social distance and situations played an important role in influencing the choice of the greeting strategies in general.

Acknowledgment

Regardless the efforts of a person, the success of any project depends largely on the encouragement and guidelines of many others. I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to the people who have been instrumental in the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I would like to show my greatest appreciation and deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Stephanie W. Cheng. I can’t say thank you enough for her tremendous support and help. I feel motivated and encouraged every time I attend her meeting. Without her encouragement, guidance and persistent help this thesis would not have been possible

I would also like to express the deepest appreciation to committee members, Dr. Sheue-Jen Ou, and Dr. Yueh-Ching Chang, for their assistance and guidance. Thanks to all the committee members for the useful comments, remarks and engagement in this thesis. Also, I like to thank the participants in my survey, who have willingly shared their precious time during the process of interviewing.

During this journey, many people have also shown their great support and help to me. All the respect and gratitude to my teachers in the TESOL department, Dr. Lin, Lu-Chun, Dr. Chang, Ching-Fen, and Dr. Sun, Yu-Chih, as well as all my classmates who made me feel like having a big loving family.

I would like to thank my loved ones, who have supported me throughout entire process, both by keeping me harmonious and helping me putting pieces together. Thanks to my dear friends, Janda, Elma, Maryam, Nadia, Jana and Nicole, who have been always there for me helping, supporting, and cheering me up when feeling really down. I will be grateful forever for your love.

Last but not least, all thanks and gratitude go to my best friend and beloved husband, Ashraf Milhim, for his love, kindness and support he has shown during the past four years it has taken me to finalize this thesis. Without him, I could never been where I am today in the first place. Furthermore I would also like to thank my parents and the whole family for their endless love and support.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... i

Acknowledgment ... iii

List of Tables ... viii

List of Figures ... ix

Chapter One: Introduction ... 1

Background and Rationale ... 1

Purpose of the Study ... 2

Research Questions ... 3

Significance of the Study ... 3

Chapter Two: Literature Review... 4

Conversational Routines and Speech Acts ... 4

What is conversation? ... 5

Conversational routine. ... 7

What is speech act? ... 8

The Speech Act of Greeting ... 9

Definition of greetings. ... 10

Greetings and body language. ... 12

Greetings in religious and other occasions... 17

Greetings in Different Cultures ... 19

Greetings in American English. ... 22

Greetings in Arabic culture. ... 25

Politeness Theory ... 27

What is politeness? ... 27

Politeness and gender. ... 28

Greetings and politeness. ... 29

Social Distance... 31

Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatic Failure in Greetings ... 32

Chapter Three: Methodology ... 36

Settings. ... 37 Participants. ... 37 DCT Questionnaire ... 38 Participants. ... 38 Instruments. ... 40 Interviews ... 44

Data Collection Procedures ... 44

Data Analysis ... 45

Chapter Four: Results ... 49

Comparison of Greeting Strategies by Arabs and Americans through Observation ... 49

Arabs in Christmas and Thanksgiving. ... 49

Americans in Ramadan and Eid. ... 51

Comparison of Greeting Strategies by Arabs and Americans through DCT Questionnaires ... 52

Number of strategies. ... 52

Use of strategies. ... 53

Use of strategies by gender. ... 59

Use of strategies by social distance. ... 67

Use of strategies by situation. ... 70

Summary of Findings ... 82

Chapter Five: Discussion ... 85

Oral Greeting Strategies by Arabs and Americans ... 85

Number of strategies. ... 85

Use of strategies. ... 87

Contextual variables. ... 91

Religious and other occasions. ... 94

Pragmatic failure. ... 95

Body Language ... 97

Gender differences. ... 98

Cultural and religious conflict... 99

Other Actions ... 102

Life in Taiwan ... 103

Summaries... 105

Implications for Classroom Use ... 106

Limitations of the Current Study and Considerations for Future Research ... 107

References ... 109

Appendices ... 112

Appendix A: Consent Form ... 112

Appendix B: Demographic Survey ... 113

Appendix C: Questionnaire Form ... 114

Appendix D: Interview Questions ... 120

List of Tables

Table 3.1 Arabs and Americans’ Demographic Information………39

Table 3.2 The relationship Between Variables and Situations ……….…41

Table 3.3 The Categories of Coding Scheme for DCT………..47

Table 4.1 Number of Strategies Used by All Groups for each Situation………..…....53

Table 4.2 Overall Use of Three Major Categories by Arabs and Americans………....54

Table 4.3 The Preferred Oral Speech Strategies by Arabs and Americans………..…..56

Table 4.4 The Use of Body Language Strategies by Arabs and Americans………..….57

Table 4.5 The Use of Other Strategies by Arabs and Americans………...58

Table 4.6 The Use of Oral Speech Strategies by Arabs and Americans Females and Males……….60

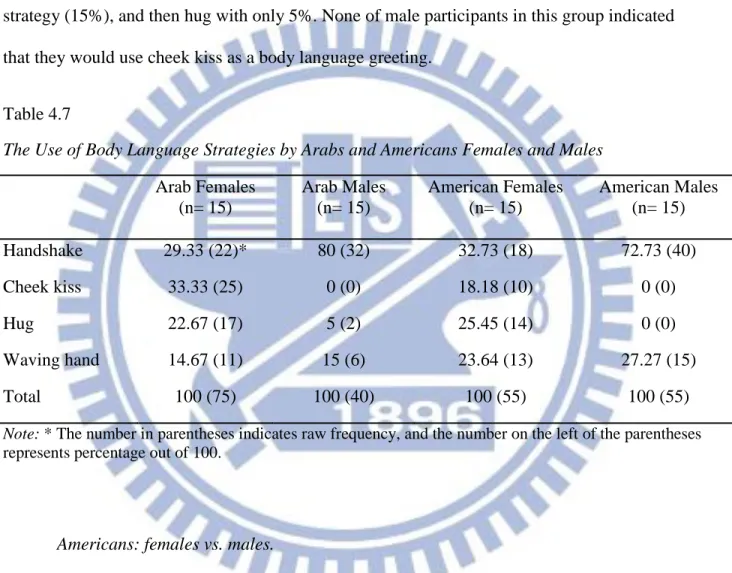

Table 4.7 The Use of Body Language Strategies by Arabs and Americans Females and Males…...61

Table 4.8 The Use of Oral Speech Strategies by Social Distance for Arabs and Americans……….68

Table 4.9 The Use of Body Language Strategies by Social Distance for Arabs and Americans…...69

Table 4.10 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 1………70

Table 4.11 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 2………...72

Table 4.12 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 3………...75

Table 4.13 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 4………....77

Table 4.14 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 5………..….78

Table 4.15 The Overall Use of Strategies by Arabs and Americans in Situation 6……….…..81

List of Figures

Figure 2.1 Japanese bowing……….…...14

Figure 2.2 Muslim prayer movements………...14

Figure 2.3 Time Magazine’s cover talking about Obama’s bowing………..…..16

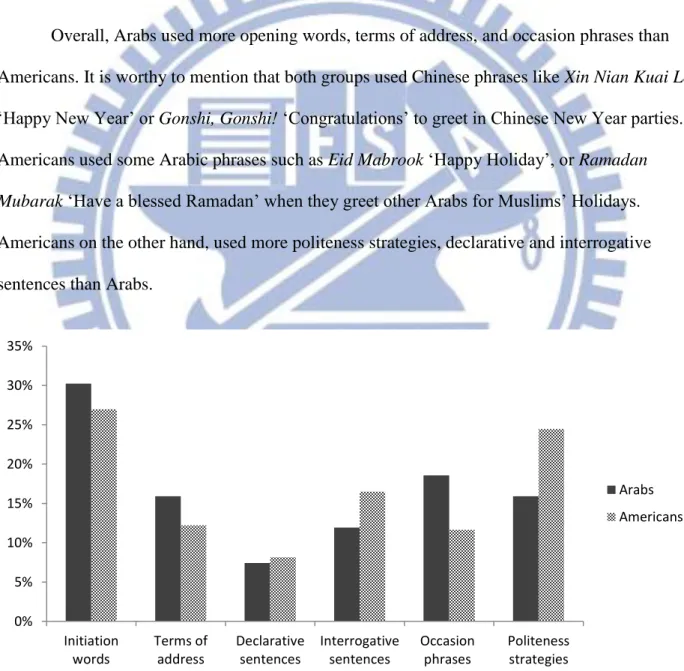

Figure 4.1 The use of oral speech strategies by Arabs and Americans………....55

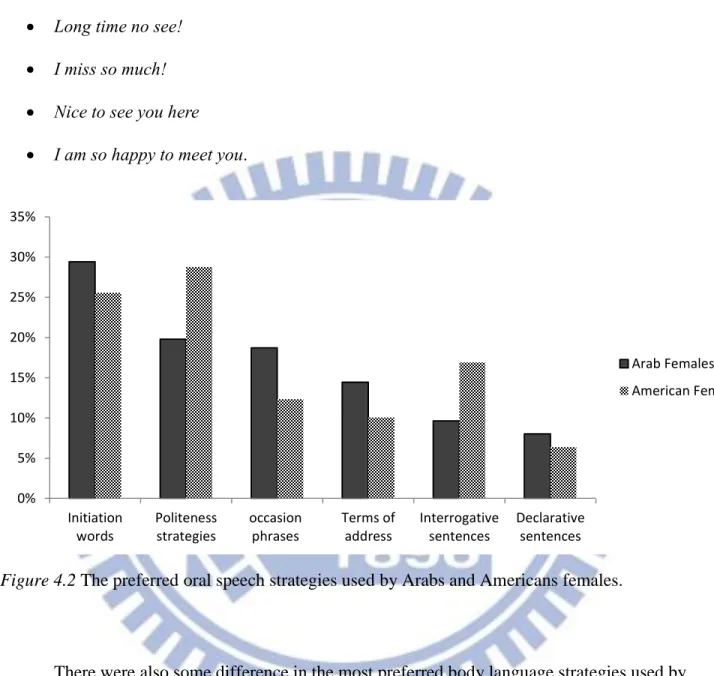

Figure 4.2 The preferred oral speech strategies used by Arabs and Americans females…………...64

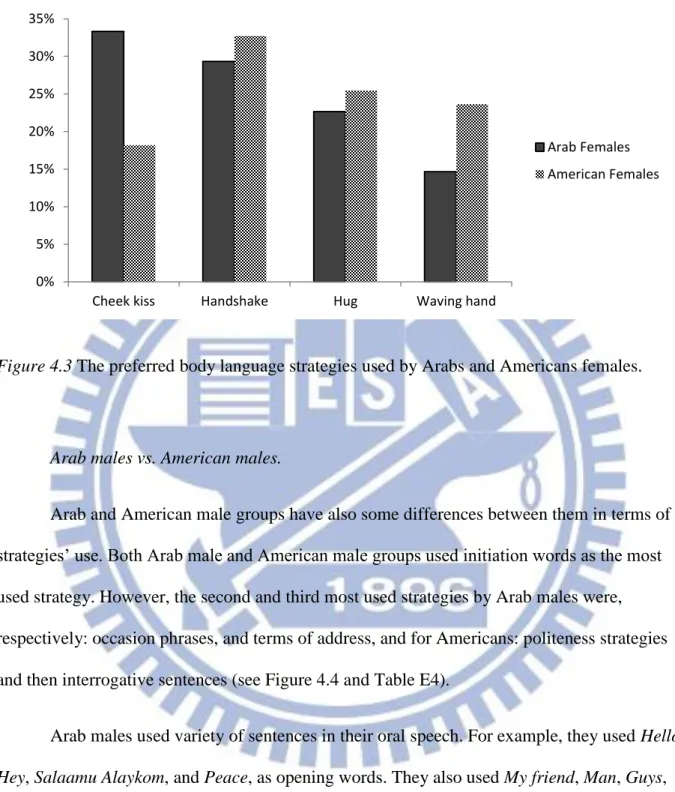

Figure 4.3 The preferred body language strategies used by Arabs and Americans females………...65

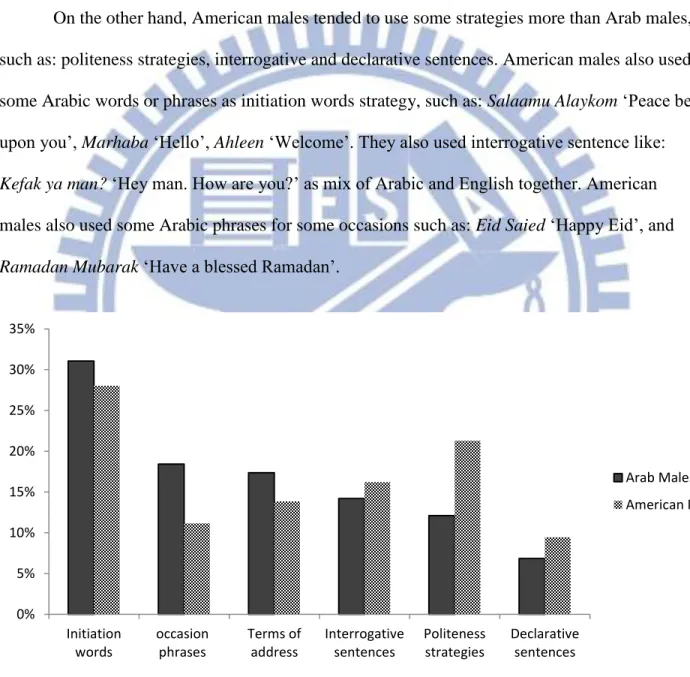

Figure 4.4 The preferred oral speech strategies used by Arabs and Americans males………66

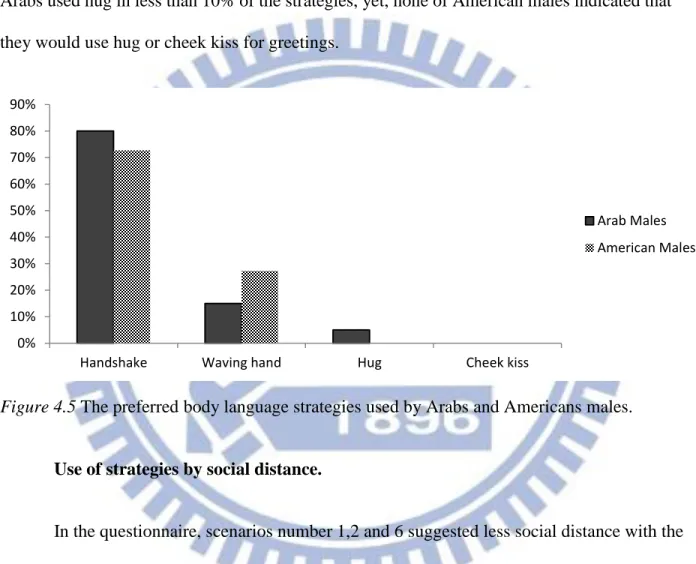

Figure 4.5 The preferred body language strategies used by Arabs and Americans males…………...67

Figure 4.6 The use of all strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 1……..73

Figure 4.7 The use of all strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 2……...74

Figure 4.8 The use of all strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 3……...76

Figure 4.9 The use of all strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 4……...78

Figure 4.10 The use of strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 5……..…80

Figure 4.11 The use of all strategies by Arab and American males and females for Situation 6….…82 Figure 5.1 Emirati student refused to shake hands with French Foreign Minister………..101

Chapter One Introduction

Background and Rationale

Language is the most typical human act and the most common way to interact among people. It goes through naturally and essentially into virtually everything in a given speech community from greeting an acquaintance to making a scientific research out to the moon. It evolves the simplest terms that interactants often employ when sending and receiving a message through various channels of communication, including verbal and nonverbal forms (Ervin-Tripp, 1971). As it has been considered the global language, English is being learned as a second language by a dramatic increasing number of students from all over the world. Communicative competence should be the goal of L2 learning because without such knowledge and ability there will be confusion and misinterpretation for both L1 and L2 students. The purpose of acquiring conversational competence is to overcome these problems. Conversations usually begin with greetings and then progress through various ordered moves (Yusuf, 1986).

Greeting is a socially significant event in universal terms, and like other major speech acts, its realization is language specific. Greetings consist of a single speech act or a speech act set. Successful greetings may be simple or complex, phatic or meaningful, formulaic or creative. Bodman, Carpenter, and Eisenstein (1995) found that “even relatively advanced non-native English speakers experience difficulty with various aspects of American greetings on both productive and receptive levels” (p. 101-102). They also added that challenges for cross-cultural communication would range from lexical choices to substantial diversity in cultural norms and values; therefore, “pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatic failure may occur in cross-cultural greeting encounters” (p. 102).

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to highlight English greeting strategies used by native speakers of English (i.e., Americans) and non-native speakers of English (i.e., Arabs). One aim of the study is cross-cultural realization of speech act of greetings. The other is linguistic realization of greetings, as all the participants have to speak and orally interact in English.

The issue of translatability across cultures or the culturally equivalent terminology as the example of greeting discourse was intuitively addressed in Davies (1987). The Arabic marhaba (said to greet a visitor to the house), for instance, seems to Davies to be untranslatable, or when welcome is used, as an English equivalent, it “would sound rather quaint or stilted” (Davies, 1987, p. 80). Many other words or phrases in Arabic language would not make much sense if being translated literally into English. More obvious formulaic expressions, which propose extreme difficulty for terminologists when considered cross-culturally, are religious phrases, such as Merry Christmas and Hajon maqbul wa Thenbon maGfur (‘May God accept your pilgrimage and forgive your sin’, said to someone who is about to go or has just come from a pilgrimage to Mecca) (Alharbi & Al-Ajmi, 2008). Therefore, the study also aims to offer a closer look at the intercultural pragmatic failure among different cultures in greetings performance, especially in some religious occasions.

The focus of the study is not limited to one aspect; rather, the study investigates different variables in real-life situations, such as gender, social distance, religious and cultural background. To gain the most authentic results, I used various data collection methods. I started with natural setting observations, then moved to DCT open-ended questionnaire (based on the natural observation results), and ended with interviews with participants.

Research Questions

I want to address two main research questions in this study, focusing on the intercultural interaction and the contextual variables, such as gender, familiarity, and different situations.

The research questions are:

1. How do Arabs and Americans perform greetings in English in terms of oral speech and body language?

2. How do contextual variables (e.g., gender, social distance, and situations) influence intercultural greeting performance by Arabs and Americans?

Significance of the Study

Conversational openings are very important to the rest of the conversation because it is during the openings that speakers evaluate each other and decide in what way the interaction can be further developed. The present study is significant because it explores an area of intercultural pragmatics that has not, to the best of my knowledge, been sufficiently explored, especially at this topic and target groups. It is hoped that the study will bridge the gap in literature and, thus, enrich the field of intercultural pragmatics.

Chapter Two

Literature Review

This research emphasizes on dynamic face-to-face interaction between Americans and Arabs when greeting in English from a sociolinguistic perspective. This chapter mainly introduces the most important and relevant literature, including conversation routines, speech acts, greetings, politeness theory, and second language acquisition and pragmatics failure.

This chapter starts with defining conversation and conversational routines, and then moves to speech acts and greetings. Topics such as: Conversational routines and speech acts, the speech act of greetings, greetings and religion, Politeness Theory and greetings in different cultures are discussed. This chapter further discusses the relations among greetings, politeness and gender, social distance, and ends with examples of pragmatic failure and misunderstandings of greetings in different cultures.

Conversational Routines and Speech Acts

Starting the conversation is a frequent and useful speech act in daily communication. While first language learners can easily acquire their own cultural greeting rituals, second language learners need to learn the language and culture to understand the appropriate ways of starting a conversation. Yusuf (1986) claimed that one of the weaknesses of ESL students is the inability to start conversations. She further argued that there are many things prevent or

discourage ESL learners from initiating conversations; for example, ESL learners feel embarrassed to start a conversation with native speakers, or the strict directions they learn in school about initiating conversations with native speakers. The greeting routines ESL students

learn at school (e.g., Hello, how are you? I am fine, thank you, and you?) does not always imply the real usage of greetings, or they may sound awkward for native speakers in casual

conversation. However, after more than a quarter century has passed since English has become one of the most popular languages worldwide, I wonder if the previous claims are still true; and whether second language learners of English still have the barriers of starting conversations with native speakers.

What is conversation?

Conversation is often described as ranging somewhere between casual talk in everyday settings and spoken interaction in general. This use of the term “conversation” as a catchall for any type of spoken discourse is common usage. Among different speech events, conversation is the most prevalent form of discourse, accounting for more than 90 percent of all spoken language, and is considered the essence of spoken discourse (Svartvik, 1980). It has to take in

consideration when analysing the conversation that it exists within a social context and interactions between people which determines the purpose of the conversation and shapes its structure and features.

In her book, The Language of Conversation, Pridham (2001, p. 2), provided a definition for conversation and the different settings where it can occur:

Conversation, therefore, is any interactive spoken exchange between two or more people and can be:

face-to-face exchanges – these can be private conversations, such as talk at home within the family, or more public and ritualized conversations such as classroom talk or question time in the houses of parliament;

broadcast materials, such as a live radio phone-in or a television chat show.

G. Brown and Yule (1983, p. 21) defined the conversation as a structure event existing of encounters, and they divided the conversation’s functions as transactional or interactional, adopted from Lyons (1977). Transactional conversation is when the focus of the encounter is to transfer information; then the language used is primarily “message oriented,” while interactional conversation is when the focus of the encounter is to establish and maintain social relationships. Jakubowska (1999, p. 19) expanded the concept of interactional conversation and provided three phases of an encounter:

During an encounter, one or more phases may occur. Three kinds of phase can be distinguished: an opening phase, a central phase, and a closing phase. Opening and closing are highly conventionalized and always have interactional character; the former consist of exchanges in which interlocutors acknowledge each other’s presence and establish their social roles during the conversation; in the latter, the conversation is brought to an end.

The present study focuses on greetings as a conversational opening in interactional conversation. Greetings or conversational openings could affect the rest of the speech. Therefore, it is very important to learn not only what to say, but also how to perform greetings. Especially when there are some social roles that may control the appropriate way to exchange greetings, one might want to avoid making mistakes that may lead to pragmatic failures between interactants.

Conversational routine.

Conversational routines are used in many social events in our daily life for native speakers and L2 speakers. Coulmas (1981, p. 2) described conversational routines as a set of tools which individuals employ in order to relate to others in an accepted way. Knowing which words may be used, speakers need to understand the appropriate situations to use them. Aijmer (1996, p. 27) suggested that conversational routines emerge and become conversationalized as a result of successful linguistic behavior being repeated in similar situations and becoming an established pattern over time. In pragmatic terms, the speaker’s knowledge of appropriate linguistic behavior is described as a frame or “hypothesis about speakers’ stereotypic knowledge of situation and how this knowledge is organized in the long-term memory” (Aijmer, 1996, p. 27). The frame contains all the information about a speech act or routine that is required for the speaker to use it appropriately.

Some researchers proposed that conversational routines in second language acquisition are often picked up before their function is fully understood, and they are used to smooth the progress of social interaction. For example, Hakuta (1974) reported his observation of a five-year old native Japanese speaker learning English in the United States, and found evidence for

"learning through rote memorization of segments of speech without knowledge of the internal structure of those speech segments" (1974, p. 31). In another study of routines in child language acquisition, Wagner-Gough (1975) noted that her subject heavily relied on routines and patterns to communicate and integrated them into his speech. Hanania and Gradman's (1977) study on an Arabic speaker living in the United States showed that in the beginning her English output consisted mainly of memorized items that are commonly used in social contexts with children. They noted that the girl was using the expressions without recognizing the individual words

within them and was unable to use the words in new combinations. In addition, Fillmore (1976) found her subjects used routines and patterns frequently and from an early stage, suggesting that the routines are learned first for social interaction, and the desire to be involved with target language speakers seems to underlie the L2 learners’ use of routines. Greetings, in general, can vary from structured conversational routines to very complex rituals. ESL learners can easily pick up the conversational routines from English textbooks and classroom environment;

however, in order to acquire the authentic and more complex language of greetings, you have to go deep into the culture to learn. The current study examines the use of strategies in different situations, which in some; simple routine greetings will not fit into the context.

What is speech act?

Frake (1964) defined speech acts as utterances or utterance sets with an interpretable function. Some examples of the routines that can mark the borders of episodes are; promises, jokes, apologies, greetings, requests, or insults. Speech acts, unlike functions, are cultural units, and must be discovered by focusing not only on the language, but also on the culture and people themselves (Frake, 1964). Austin (1962) also defined speech acts as acts performed by utterances such as giving orders or making promises. They may be a direct or an indirect utterance (a word, phrase, sentence, number of sentences or gesture and body movement) that serves a function in communication such as thanking and apologizing (Hatch, 1992).

Searle, J. R. (1969) identified four basic categories of speech acts: utterances,

propositional utterances, illocutionary utterances, and perlocutionary utterances. He (1975, p. 64) maintained that ordinary conversational requirements of politeness normally make it awkward to issue flat imperative sentences (e.g., leave the room) or explicit performatives (e.g., I order you to leave the room), so people resort to indirect means to their illocutionary ends (e.g., I wonder if

you would mind leaving the room). Searle, J. R. (1979) further claimed that speech acts perform five general functions: declarations (e.g., I now pronounce you husband and wife),

representatives (e.g., it was a warm sunny day), expressives (e.g., I’m really sorry), directives (e.g., don’t leave anything behind), and commissives (e.g., we’ll not disturb you).

Speech acts include real-life interactions and require not only the knowledge of the language but also the appropriate use of that language within a given culture to minimize

misunderstandings (Hatch, 1992; Lindfors, 1999); this is in line with Celce-Murcia and Olshtain (2000) claimed that learners need to be aware of discourse differences between L1 and L2 to insure the proper acquisition of pragmatic competence.

Greeting is one of the most commonly used speech acts that people perform in daily interactions. However, performing greetings in special occasions (e.g., New Year or Christmas) differs from the daily routine, where different greeting strategies might be used.

The Speech Act of Greeting

Nowadays linguists agree that people do not use language just to exchange information efficiently; in addition to the informational content, language users also employ communicative strategies that are suitable for the contexts in which the exchange is made. It is difficult to generalize differences in impolite and polite non-verbal behavior since such differences vary greatly across cultures. For example, greeting exchange is a social ritual which makes

communication between members of the society possible. Though greetings are often treated as a spontaneous emotional reaction to bring together or separate people, they carry their own social message, and highly conventionalized for the most part (Greere, 2005).

Definition of greetings.

According to Aijmer (1996), greeting represents an acknowledgment of the relationship between two individuals. It is an act of communication in which human beings intentionally make their presence known to each other, to get attention, and to suggest a type of relationship or social status between individuals or groups of people coming in contact with each other.

Brown, I. C. (1963) noted the place of greetings in the large context of culture: “It is the way we greet friends or address a stranger, the admonition we give our children and the way they respond, what we consider good and bad manners, and even to a large extent, what are consider right and wrong” (p. 26). Brown’s wide scope of definition seems to put the whole greeting concept in a big container, while other researchers provide simpler definitions.

Searle, J. R. (1969) considered greetings corresponded to some part of rituals or

sometimes formulated to go along with the speech act and in its rules in the speech community. His definition of greetings is shown below:

Greetings are a much simpler kind of speech act, but even here some of the distinctions apply. In the utterance of 'Hello' there is no propositional content and no sincerity condition. The preparatory condition is that the speaker must have just encountered the hearer, and the essential rule is that the utterance counts as a courteous indication of recognition of the hearer (p. 64-65).

In his definition, Searle simplified the context and usage of greetings, which may not be the case in different occasions. I would agree with the point that greeting is a common speech act which can be easier to learn that some other speech acts. However, rather than our daily routine greetings, this type of speech act could be very complex in some situations and occasions.

Later, in his book Relations in Public, Goffman (1971) proposed three generalizations in interpreting greeting behavior: (a) exchanges serve to reestablish social relations, (b)

acknowledgement of a differential allocation of status, and (c) when greetings are performed between strangers, there is an element of guarantee for safe passage (p. 74). Firth S. (1973) also referred to greeting phenomena as ritual with verbal and non-verbal forms. Verbal forms include one of three linguistic units: question (How are you?), interjection (Hello/ hey) or affirmation (Good morning), whereas non-verbal forms are composed of body languages such as hand shake, kisses, and hug. I think that these two authors provided good definitions of greeting types and greeting functions.

Laver (1981) viewed greeting exchanges as having three components: formulaic phrases, address forms, and phatic communion or small talk (e.g. Nice day for this time of year). Laver applied the notion of routine to all three categories, thus proposing that greeting exchanges as a whole are routine rituals. In short, greetings are composed of several interlinking behaviors: (1) salutation or the verbal linguistic form, (2) term of address, (3) body language, and (4) social context. In his definition, Laver tended to treat ‘term of address’ as a separate greeting strategy or behavior, while in most studies- including the current one- this element considered as part of verbal linguist form. That is because one can simply use only the term of address to perform greeting to another (e.g. Mark!).

After reading through the literature, I would define greeting as a human behavior aims to acknowledge people’s presence, show respectful, share cultural rituals, and simply start a

conversation. Greetings can be very simple (e.g. our daily routine greetings) or very complex (e.g. religious or public occasions). They also could be consist of only one single strategy, or combined of different greeting strategies in same conversation. In addition to the oral greetings,

the present study will also focus on body language between Americans and Arabs, because both groups are from different cultural backgrounds which might require different body languages when greeting.

Greetings and body language.

When greeting, people use different forms of body languages. For example, they bow, rub noses, shake hands, kiss, or raise their eyebrows. People in different cultures use different body languages. For example, Polynesians rub each other’s backs or sniff each other’s breath, East Africans might spit on the ground in a greeting, and Tibetans used to stick out their tongues. Some New Guinean tribesmen pat each other on the rump. Not long ago, Westerners learnt elaborate ways of removing their hats with a flourish or even threw themselves face-down on the ground in front of their superiors. There is hugging of heads, clasping of knees, kissing of feet, touching of shoulders – even today (Lundmark, 2009).

It might seem easy to say hi and to say bye. However, the matter of meeting and leaving tends to be a complicated act. The rituals of approaching and departure seem infused with etiquette and custom, no matter which culture you belong to. If misperformed, one might end up in trouble or embarrassed. What seems entirely natural in one culture can be a strange behavior in another.

Kissing as a greeting has been used ceremoniously depends on the cultural setting. As the New Zealand ethnologist R. W. Firth (2004, p. 19) put it:

American and English people who might exchange a kiss in private greeting may refrain from such intimacy in public. But this is a highly cultural matter – a Frenchman in office

may bestow a kiss on another on a formal public occasion when he would not do so at an informal private meeting.

In many societies, such as some Arab countries and Scandinavia, eye contact is highly expected when greeting. In other cultures, for example in Japan, some indigenous American societies, or among many Australian Aborigines, it is considered impolite to look at someone straight in the eye, especially superiors and elders (Bauml & Bauml, 1997). Waving is a common way of greeting or farewelling each other at a distance. Japanese students (usually female) are often seen waving vigorously at each other at very close proximity – even closer than a handshake or a bow would require – shouting in greeting (or screaming, as the case may be) hisashiburiiiiiiiiiii! ‘It’s been a long time!’ although it might have been a very short period since they last saw each other. More commonly, however, waving is a substitute for touching the other person when you cannot reach him. Much like a blow-kiss when you are too far away for a real kiss, you wave when physical distance prevents you from grasping or clasping or touching the other person (Lundmark, 2009).

Bowing is part of many greeting rituals. A bow can be as quick and easy as a slight nod of the head, or as long and complex as a Chinese kowtow. In some countries, bowing is a veritable science in itself. In Japan, bowing is done not only in business and social settings, but also in religious, sport, traditional arts, school and many other situations (see Figure 2.1). The bow is also an essential part of the Japanese tea ceremony. Bowing is so ingrained in Japanese people that they even bow when speaking on the telephone. Moreover, the bow is often

inextricably linked to a word or phrase. For example, to say arigato- gozaimasu ‘thank you’ without bowing would seem very strange, if not unthinkable, to a Japanese person (Lundmark, 2009).

Figure 2.1 Japanese bowing.

On the other hand, bowing is not an appropriate way of greeting in Arabic culture because bowing is one of the special moves they do when they perform their praying to God. They consider bowing is not for another human beings, but only exclusive for Allah ‘God’ (see Figure 2.2). Therefore, in an intercultural communication between Arabs and Japanese, cultural misunderstanding may occur.

As an example for cultural misunderstanding, on April 1, 2009 in London, president Obama bowed to Saudi King Abdullah while he was greeting him (see Figure 3), what aroused anger among American society, especially that, later same day, he just nod his head to Queen Elisabeth II, which made many people looked at his bowing as he was ‘paying his obey for money’. Not to be deterred by the criticism that followed, Obama bowed later in 2009 to the emperor of Japan. However, at that time, some people said that he was trying to show respect to other people’s culture, yet; many other people still couldn’t accept this greeting act from

American president. Even in Arabic countries, people and media criticized Obama’s bowing, and considered it as ‘inappropriate way to perform greeting’, while in Japan they said that Obama was not bowing correctly, and he looked like he was apologizing instead of greeting (he bowed in more than 45 degrees). Obama at least has learned not to bow to Saudi royals; two months after his April 2009 prostration, he avoided repeating the mistake.

Veteran White House reporter Keith Koffler (2012), wrote an article titled ‘Obama Has Bowed Eight Times as President’ saying:

American presidents, who have been put in charge of a democratic nation that specifically broke from royalty, particularly should not bow to kings and queens. We need our presidents to appreciate and be polite to other cultures and leaders. But the president of the United States is the leading political figure in the world. He must command respect. Let others bow to him.

Figure 2.3 Time Magazine’s cover talking about Obama’s bowing.

Other ways of greetings, such as handshake, which spread gradually throughout the second half of the 19th century, became the preferred greeting all over Europe. A few notable ones include the East African variety: a gentle slap of the palms, followed by cupping the hand and grasping each others’ fingers. The Mexican model is a conventional handshake followed by flicking the palm upwards and grabbing hold of each others’ thumb. Another African variant, popular among the Bantu people and others in the south, is a conventional handshake which ends with the joined hands being raised into the air, and letting go at the top (Lundmark, 2009).

“In May 2008, a Muslim man in Sweden lost both his apprenticeship and pay when he refused to shake hands with the company’s representative, a woman. He claimed that his religion

did not allow him to touch females outside his immediate family” (Nyheter, 2008, May 23). This is one of many examples where cultural misunderstanding takes place not only in private meetings, but also in some public occasions. For example, Emine Erdogan, the wife of Turkish prime minister, did not allow the French minister to kiss her hand in a public political occasion. While kissing ladies hands is a polite protocol in France, it is not an acceptable act of greeting among some groups of Muslims.

Greetings in religious and other occasions.

American Holidays.

Christmas Day is an annual commemoration ofthe birthof JesusChrist, celebrated generally onDecember 25th as areligiousandculturalholidayby billions of peoplearound the world ("Christmas," n.d.). Popular modern customs of the holiday includegift giving,Christmas music, an exchange ofChristmas cards,churchcelebrations, aspecial meal, and the display of variousChristmas decorations, including Christmas trees,Christmas lights,nativity

scenes,garlands,wreaths,mistletoe, andholly.

Christmas and holiday greetingsare a selection of goodwillgreetingsused around the world to address strangers, family, coworkers or friends during theChristmas and holiday

season, which spans an approximate time-frame from late November to January. Holidays of this season generally includeChristmas,New Year's Day, Hanukkah,and Thanksgiving. Some greetings are more prevalent than others, depending on theculturalandreligiousstatus of any given area. Typically, a greeting consists of the word "Happy" followed by the holiday, such as Happy New Year or Happy Hanukkah, although the phrase Merry Christmas or Season's Greetings can be a notable exception (Marling, 2001).

In the United States, the collective phrase Happy Holidays is often used (mainly by stores) as a generic cover-all greeting for all of the winter holidays: Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa; however, the phrase is not widespread in other countries. The greetings and farewells Merry Christmas and Happy Christmas are traditionally used inNorth America, theUnited Kingdom, IrelandandAustralia, commencing a few weeks prior to Christmas (December 25) of every year. The phrase is often preferred when it is known that the receiver is aChristianor celebrates Christmas. The nonreligious often use the greeting as well; however, in this case its meaning focuses more on the secular aspects of Christmas, rather than theNativity ofJesus (Marling, 2001; Young, 2004).

Arab Holidays.

In the Arabic-Islamic world, both the Arabic language and the Muslim faith are often viewed as inseparable parts of the same Arab Muslim identity, as mentioned in the words of Abdo A. Elkholy “The Arabic language is an inseparable part of Islam” (Turner, 1978, p. 109). As Stewart Desmond (1968) explained, “ the Arabic language is more than the unifying bond of the Arab world; it also shapes and molds that world” (p. 14). Since Arabic is the language of the Qur’an and Muhammad, the Messenger of God, “it has an even greater effect on its speakers than other languages have on their speakers” (Desmond, 1968, p. 14). Speakers of Arabic and those who read it via their devotion to the Qur’an recognize the language as directly dispensing Allah’s word and law, as well as the words of the earliest disciples of those pronouncements. This lexicon is the rich and varied body of hundreds, perhaps thousands of religious expressions which form a unique feature of the Arabic language, including insha’ Allah ‘God willing’, alhamdulillah ‘Praise be to God’, subhan Allah ‘Glory be to God’, masha Allah ‘It is

the will of God’, baraka Allahu fik ‘May God bless you’, jazaka Allah khayr ‘May God reward you’, fi amanillah ‘God with God’, inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un ‘From God we come and to Him is our return’ and a multitude of others.

There are two main holidays (or Eid) for Muslims all over the world, one comes after month Ramadan called Eid al Fitir, and the other one comes after the big pilgrim to Mecca in Suadi Arabia (Hajj), called Eid al Adha. In these two occasions, Muslims usually exchange greetings and perform special religious rituals. Phrases like Eid Mubarak, Ramadan Kareem, Hajjan Mabroor, and Happy Eid, are widely used by all Muslims –even the ones who does not speak Arabic as the first language.

Greetings in Different Cultures

Fieg and Mortlock (1989) attempted to generalize the utility of greetings initially as influences of social factors, and then pointed out cross-cultural differences, such as how each culture’s cosmological views influence the meaning of their speech act. The theoretical concerns then revolve around notions of culture and provide underlying explanations of purpose. Greeting, in short, is a speech event with pragmatic meaning and the meaning, in turn, is affected by cultural perspectives.

Saying “good + time of day” is a common greeting among Indo-European languages. The Germans say guten Tag, the French say bonjour, the Italians say buon giorno, the Spaniards buenos dias, the Macedonians dobar den (in most Slavonic languages, dobro means ‘good’), the Poles dzien´ dobry, and so on. But other cultures and languages don’t use this form of greeting at all. The Chinese, for example, commonly say Have you eaten? as a greeting. The normal Arab

greeting is Peace be upon you. The Masai ask How are the children?, and the New Zealand Maori encourage you to Be well (Lundmark, 2009).

According to P. Brown and Levinson (1978 ), one of the principal means of expressing politeness is through greetings. Greetings in many languages may include questions about the addressee's health such as How are you? Such questions are largely ritualistic and need not be answered sincerely. In English, they are often not answered at all. In Malay, greetings are elaborate and such questions must be answered.

Different from Germans’ greetings where in informal situations, one is normally greeted by a simple Hallo! ‘Hello!’ or Guten Tag! ‘Good Day!’, Californians seem to prefer to begin the communicative interaction with What’s up? or How is it going? In accordance with Knuf and Walter (1980), I believe that ritualized greeting formulas are different from sincere inquiries about a person’s well-being. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that such a conversational starter is much more context-sensitive and thus more susceptible for emotional traits than the German openings. In Peru, too, people normally come into contact by using formulas in the form of Cómo está? ‘How are you?’ with older or hierarchically higher interlocutors and likewise Cómo estás? or Qué tal? ‘What’s up?’ when addressing close acquaintances or younger people.

Greeting expressions constitute an important part of the polite language. By greeting, the speaker indicates his attitude toward the addressee, or starts a conversation with him. For

example, in China, greeting expressions can be divided into different types. One is called ‘interactive’, for instance, chi le ma? ‘Have you eaten yet?’, shang nar qu ia? ‘Where are you going?’. They are not real questions, but are used as a friendly salute. This type of greeting carries a sense of informality and intimacy; it is often used among familiar acquaintances.

Another type assumes the form of giving regards to others; typical examples of which are ni hao! ‘How are you? ’ or nin zhao? ‘Good morning’. The third type of greetings uses expressions of paralanguage, such as facial expressions, gestures, or some prosodic sounds. The usual form of this type of greeting used in China is nodding and smiling. Implications of such greeting vary according to social status of the speaker, as well as the relationship between the two. Generally speaking, women prefer this type for the sake of dignity and staidness, whereas men can use it to display an air of reserve. This type shows distance and indifference between acquaintances, and therefore, it is often used to strangers.

A large scale study on greetings, entitled “Cross-cultural realization of greetings in American English” was conducted by Eisenstein Ebsworth, Bodman and Carpenter (1995). The participants were divided into different groups based on their native languages, such as American English, Spanish, French, Hindi, Japanese, Chinese, Russian, Greek and other languages, in order to analyze greetings. The study shows that the difference of the usage of greetings was recognized when the choice of a special topic such as the family occurred in a conversation. American English speakers tend to ask about the well-being of the hearer and all members of family, but for Arabs, Iranians and Afghans the greeting would only involve male family members, indicating that different cultures have different rules of greetings’ usage. Russians, Ukrainians and Georgians were surprised when they were asked about their well beings, because they expect that these greetings performed when they meet a good friend. Therefore, they would wonder about the reasons which make people greet a person they do not even know well.

Ebsworth (1992 ) also indicated that greetings can be seen in the different ways which cultures choose to perform these speech acts. Greetings in American or British English are often produced by a serial turn taking of the communicative partners. It was recognized that American

greetings have a greater variety because Americans make use of more creative language. Compared with Afghans, it was found that people of this speech community greet each other simultaneously and overlap each other by producing for instance similar questions about well-being. They also use a full greeting every time they meet during the day so that a “greeting on the run” would never occur in Afghanistan (e.g., wave to somebody when you pass by and say ‘Hi’ without stopping to chat with him) as it can be fine for Americans. These facts already show that greetings as part of cross-cultural communication may vary from lexical choices to

substantial differences in cultural norms and values.

Regardless the differences in languages and cultures, when it comes to perform greetings, many variables may influence the person’s choice of greeting strategy, starting from gender, social status, social distance, age difference, occasion, and religious or ethnical background.

Greetings in American English.

Every society has its own particular customs and ways of communications. People in the United States come from different backgrounds with regional and temperamental differences. It is difficult to make generalizations about American manners and customs. Therefore, when one reads that Americans do so and so or think so and so, we need to keep in mind that not all Americans do so. One of the examples is greetings exchange.

Greetings in American English consist of a range of linguistic and non-verbal choices which may include a simple wave or smile, a single utterance, or a lengthy speech act set which can involve complex interactional rules and take place over a series of conversational turns.

Nodoushan (2007) provided some examples and explanations for the most common used greetings in American English. He divided the greetings into two different types based on time:

in time-free and time-bound, and suggested that English greetings could be displayed as the following:

1. Time-free greetings: How do you do? Hello. How are you? Hi. How are you? Glad to meet you!

(it’s) Good to see you (again)! (How/Very) Nice to see you (again)! Long time no see you!

(Ah, X [any first name or honorific]) just the first person I wanted to see/was looking for/was after.

2. Time-bound greetings Daily formal greetings: Morning: Good morning. Afternoon: Good afternoon. Evening: Good evening. Day: Good day.

Night: Good night. Seasonal (in)formal greetings:

Happy New Year! Happy Anniversary!

Happy Easter!

Happy Birthday (to you)!

Many happy returns (of the day)! (A) Merry Christmas (to you)!

Many happy returns (of your birthday)!”

Nodoushan (2007) also claimed that Americans tend to be more informal in their daily life greetings. Except on official occasions such as reception of distinguished guests, American society has a certain amount of informality in introductions and greetings. On most occasions one need not be ‘particularly conscious of social status, Americans generally ignore it’ (p. 359). In spite of the informality, however, there are rules of good manners and social patterns that should be followed. There are rules of introducing people to each other. A younger person is generally introduced to an older person, a man to a woman, a guest to the host or hostess, and a person to the group (Nodoushan, 2007).

The most common greeting for acquaintances meeting on the street is "Hello." It can be used as formal and informal greeting depend on the sentence it comes within. For example, if you meet your friends and greet them with Hello guys! It will be considered informal, while when you meet your boss for example and say Hello Mr. Green! It will be a more formal greeting. Other more formal greetings are Good morning, Good afternoon, and Good evening. These greeting (except "How do you do?") are often followed by the question How are you?. Though in a question form, the greeting of How are you? only requires a brief replies such as Just fine. How are things with you?. This may cause miscommunication in a situation when a patient comes to see a doctor; the receptionist asks How are you? and he answers just fine! when

the receptionist actually wants to know more details about his health condition to write down on his report.

However, in spite of the informality, Americans are not completely devoid of customs that show consciousness of social distinction. One is likely to use somewhat more formal language when talking to superiors or people with higher social status. For example, the less formal Hello (without terms of address) is an acceptable greeting for an employee (when greeting his employer), the employee is more likely to greet with more formal greeting like Hello, Mr. Adversin, whereas the employer may reply Hello, Jim or even Hi, Jim.

The custom of hand shaking varies among different culture groups. In general, hand shaking is mostly reserved for formal occasions. When men are introduced, they generally shake hands, but women shake hands less frequently. For example, when women meet each other for the first time they generally do not shake hands unless one is an especially honored guest. If a man and a woman are being introduced to each other, they may or may not shake hands. If they do, woman always extends her hand first. For acquaintances meeting on the street, if a person does not shake hands when he meets and old acquaintance, he is not regarded as impolite. He may compliment the acquaintance and consider him as a member of his own group (Nodoushan, 2007). Kissing-related greetings, such as kissing on the cheek or kissing hand, are less common among Americans. Hand kissing is only observed in “absolutely formal situations on certain occasions” (Nodoushan, 2007, p. 359).

Greetings in Arabic culture.

In Muslim society, the most common verbal greeting is assalamu‘alaykum ‘peace be upon you’. This is, according to the Qur’an, how you will be greeted by the angels as you enter

Paradise, and it is also the way you greet your fellow humans. The most common reply is alaykum as-salam, ‘and upon you, too, peace’. However, one of the guidance in Qur’an is that “when you are greeted with a greeting, greet with one fairer than it” (Surat An-Nisa', 86), which means that you are invited to redouble the greeting back and out-greet the greeter, as in

wa‘alaykum as-salam wa-rahmatullahi wabarakatuhu, which means ‘and on you be peace, and also God’s mercy and also His blessing’ (Lawrence, 2006).

In the Arab culture, an adult usually should greet each individual in the whole group even if there is only one person in the group who is known to him. In situation where one person walks by or meets a group, greeting not only is to maintain solidarity with the whole group but also is viewed as a social etiquette with a religious obligation. In Arabic culture, if a passer-by does not say Hello to the group he will be criticized publicly. However, greetings are largely optional if people have previous conflict or tense relationship with each other. In addition, a greeting is also optional when the group is made up of two, so one may simply greet one to the exclusion of the other.

The custom of hand shaking in Arabic countries varies from one country to another. When men are introduced, they generally shake hands. Women shake hands if they are familiar with each other, or if the other part is an important (female) guest. However, even today, in most cases, when a man and a woman are being introduced for the first time, they almost never shake hands due to their religious beliefs. The same holds true with regard to kissing-the-cheek custom; however, kissing the cheek is very common if two females greet each other.

Politeness Theory

Politeness is an area of interactional pragmatics which has experienced an explosion of interest over the past quarter of a century and in which empirical studies have proliferated, examining individually and cross-culturally languages and language varieties from around the world (Hickey & Stewart, 2005).

What is politeness?

In his own book ‘Politeness,’ Richard Watts (2003, p. 1) described how hard it is to define politeness:

Most of us are fairly sure we know what we mean when we describe someone’s behavior as ‘polite’. To define the criteria with which we apply that description, however, is not quite as easy as we might think. When people are asked what they imagine polite

behavior to be, there is a surprising amount of disagreement. Some people feel that polite behavior is equivalent to socially ‘correct’ or appropriate behavior; others consider it to be the hallmark of the cultivated man or woman. Some might characterize a polite person as always being considerate towards other people; others might suggest that a polite person is self-effacing. There are even people who classify polite behavior negatively, characterizing it with such terms as ‘standoffish’, ‘haughty’, ‘insincere’, etc.

Politeness manifests itself in social interaction and is conditioned by the socio-cultural norms dictated by the members of a society who negotiate their intentions by means of verbal and non-verbal actions (Félix-Brasdefer, 2008). The majority forms of politic behavior consist of highly routinised sequences whose function is to regulate the lines taken in the interaction order and to ensure overall face maintenance. This is the case with greeting sequences, leave-taking

sequences (e.g., saying goodbye), request and acceptance sequences, apology sequences, addressing other interactants, etc. These sequences have a regulatory force in facework, contributing to the reproduction of politic behavior (Watts, 2003).

In this perspective, the politeness markers can be labeled together with speech acts such as greetings, farewells, jokes, compliments and congratulations as supportive interchanges belonging to “the ritualization of identificatory sympathy,” “rituals of ratification” (Goffman, 1971, p. 65, 67), which function as displays of reassurance between interlocutors and provide signs of involvement in and connectedness with another person in society. Thus, rather than redressing a negative face-threat, the display of verbal energy in these situations constitutes an act of doing positive face (Lakoff, 1973, p. 298), as it emphasises goodwill to bring the

interaction to a successful end.

Politeness and gender.

At a stereotypical level, politeness is often considered to be a woman’s concern, in the sense that stereotypes of how women in general should behave are in fact rather a prototypical description of white, middle-class women’s behavior in relation to politeness. That is, teaching and enforcement of ‘manners’ are often considered to be the preserve of women. Femininity, that set of varied and changing characteristics which have been rather arbitrarily associated with women in general, and which no woman could unequivocally adopt, has an association with politeness, self-effacement, weakness, vulnerability, and friendliness. This manifests itself in the type of language practices which Lakoff described as ‘talking like a lady’ (Lakoff, 1975, p. 10).

Women’s linguistic behavior is often characterised as being concerned with co-operation (more positively polite than men) and avoidance of conflict (more negatively polite than men).

This characterization is based on the assumption that women are powerless and display their powerlessness in language; these forms of politeness are markers of their subordination.

However, stereotypes of gender have been contested for many years by feminists and have themselves been changed because of the changes in women’s participation in the public sphere. We can therefore no longer assume that everyone has the same ‘take’ on a stereotype, or that they share assumptions with others about what a particular stereotype consists of. Mills (2003) discussed in her book the complex relations between gender and politeness and argued that although there are circumstances when women speakers, drawing on stereotypes of

femininity to guide their behavior, will appear to be acting in a more polite way than men, there are many circumstances where women will act just as impolitely as men.

Greetings and politeness.

Politeness is one of the most important aspects of human communication: human beings can only exist in peace together if certain basic conventions of politeness are observed (Rash, 2004). Since Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson first developed the theory of linguistic politeness, most sociolinguistic studies have looked at politeness in terms of "face" (Hartung 2001, p. 214). Social cohesion depends upon awareness and consideration of the "face needs" of others. Each participant in human society has two types of face need: a "positive face need" and a "negative face need". The positive face need is “the positive consistent self-image or

‘personality’ (crucially including the desire that this self-image be appreciated and approved of) claimed by interactants” and the negative face need is “the basic claim to territories, personal preserves, rights to non-distraction - i.e. to freedom of action and freedom from imposition” (Brown & Levinson 1987, p. 61). Positive politeness attends to a person's positive face needs and includes such speech acts as compliments, invitations and greetings. It expresses good-will and

solidarity. On the other hand, negative politeness attends to a person's negative face needs and includes indirectness and apologies. It expresses respect and consideration (Holmes, 1995, p. 154).

Interactants in a communicative act great to respect the face needs of others. Failure to do so is seen as an intrusion into another's personal space or territory; as a "face threatening act" (FTA) (Lüger, 2001, p. 6). FTAs include threats, insults, criticism and orders. The negative effect of an FTA may be reduced or totally eliminated by a variety of types of corrective "face work". Such "face-redressive" or "face-saving" work may involve linguistic indirectness, such as modal verbs, particles or hedges, as in Wouldn't you like to close the window?. An FTA may also be mitigated by an apology, as in I'm sorry to bother you, but would you please close the

window?.

As with politeness in general, greetings can be analyzed within the framework of theories of face. When we approach our fellows, we are entering their personal space, or their territory. This can be interpreted as an FTA, particularly if we remain silent, as silence is naturally experienced by human beings as disconcerting: breaking a silence, as in greeting, is a sign of friendly intent (Züger, 1998, p. 29). A greeting, if performed correctly, that is with appropriate words, tone of voice and body language, can attenuate the force of a potential FTA. Some people are aware of the face-saving function of greetings: one greets to show that one wishes to

establish a relationship in a non-threatening atmosphere. This is also referred to as "phatic communication" (Crystal, 1987, p. 427). Züger (1998) documented two aspects of greeting: (1) Initialphatik ‘initial phatic communication’ or ‘initial greeting’, and (2) Terminalphatik ‘terminal phatic communication’ or ‘leave-taking’. A greeting exemplifies how a phatic communication act may be "other-oriented" or "self-oriented" (Laver 1975, p. 223). Self-oriented greetings may

include declarative statements, such as My legs weren't made for these hills; other-oriented greetings often contain a question, like How are you? or comments, such as That looks like hard work (Laver, 1975, p. 223). Holmes (1995) believed women to be more other-oriented than men, as exemplified in their greater readiness to accept apologies. She claimed that this is because women feel more responsible for social harmony than men; that they are more interested in finding common ground and establishing solidarity (Holmes, 1995, p. 188). In Switzerland, as elsewhere, it is women who tend to perform the very important task of teaching greeting conventions to their children.

Social Distance

As other variables play an important role in the speech act of greeting, the element of social distance has no less significant role in here. Familiarity and intimacy between people would affect all kind of speech acts they use among them (Blum-Kulka, S. & Olshtain, E., 1984). Social distance between people, their relative status, and the formality of the context all together influence the choice of appropriate speech forms (Holmes, 2008: 273). Migge (2005), revealed that greetings play an important role in defining the nature of social relationship. When people greet family members or close friends, they tend to use less formal speech, and less number of greeting strategies; they can directly engage to a conversation without using long and formal openings.

According to Migge (2005), greetings that convey less social distance are usually consist of less formulaic utterances, and the verbal content of the adjacency pairs implies a great degree of familiarity or a closer relationship. Moreover, one can notice the less social distance between two interlocutors when they exchange personal information (e.g. about their state of health) and directly relate to each other using pronominal forms of address. She also suggested that in

everyday situations, like in daily greetings between neighbors, classmates or people who regularly meet each other and maintain a cordial, yet formal relationship, they tend to use less greeting strategies (usually only three sequences), and more formal language. People also tend to use more politeness strategies when they greet someone they are not very familiar with (Migge, 2005). In the current study, I used social distance as one of the research variables in order to elicit more authentic results that are closer to real life situations.

Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatic Failure in Greetings

In the context of a foreign language, “the more speakers understand the cultural context of greetings, the better the society appreciates them, and the more they are regarded as well behaved” (Schleicher, 1997, p. 334).

Intercultural communication is perceived as being somewhat problematic, given the varied cultures that come into contact with one another. Misunderstanding and communication breakdown are said to mark many intercultural encounters as participants rely on the norms of their mother tongue and native culture to interpret meaning.

The term 'pragmatic failure' is borrowed from Thomas (1983) and is said to occur on any occasion on which the hearer perceives the force of the speaker's utterance as other than the speaker intended s/he should perceive it. In a natural setting this may lead interlocutors to serious misinterpretations of each other's intentions and in the most dramatic cases to communication breakdowns.

Greeting is one of the functions in language that establishes a platform for acceptance creating a positive social bond between interlocutors. When it is not performed well, it can result in confusion, awkwardness, and hostility. Dissimilar interactional styles between two languages

can lead to misunderstandings and negative stereotypes, including such widely-held false assumptions that Spaniards are rude and English speakers are hypocrites (Ballesteros, 2001).

The following two examples are the notion of pragmatic failure involving formulaic language. In United States, a lot of foreigners are annoyed by the apparent insincerity of some Americans who say they would like to invite someone to lunch, but never really do so (Wolfson, 1981). What happens is that the foreigners do not realize the formulaic nature of such

expressions like We must have lunch together some time, or its more recent variant Let's do lunch which belong to some Americans' repertoire of leave-taking formulas such as: See you, So long, Take care, etc., and these expressions do not signal the speaker's commitment to have lunch with the hearer. Pragmatic failure occurs because the hearer assigns the force of the invitation to an utterance whose intended force is a friendly leave-taking. In other words, the intended force of the utterance as a formulaic leave-taking is mistaken for a (non-formulaic) invitation.

The second example quoted by Fillmore (1984) contains two separate anecdotes about the use of the American English formula I thought you'd never ask. It's a fairly innocent teasing expression in American English, but it could easily be taken as insulting by people who did not know its special status as a routine formula. In one case a European man asked an American woman to join him in the dance, and she, being playful, said, I thought you'd never ask. Her potential dancing partner withdrew his invitation in irritation. In another case a European hostess offered an American guest something to drink, when he, unilaterally assuming a teasing

relationship, said, I thought you'd never ask. He was asked to leave the party for having insulted his host (Fillmore, 1984, p. 129-130).

Another difference concerning the way of greeting can be seen in Puerto Rico, where greeting a friend has a high significance, which means that conversations are always interrupted when a friend passes by. Americans would be confused by this behavior because they always feel that their first obligation is to the person they are having a conversation with and when a friend would like to talk to one of the speakers, he or she would have to wait just outside the listening distance until the conversation has come to an end.

Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1986) examined possible causes for pragmatic failure in learner’s inter-language. They aimed to capture the types of misunderstanding which occur when two speakers “fail to understand each other’s intentions,” especially when one of these speakers is a second language learner, whose different linguistic and cultural background may play a key role in such misunderstanding (p. 49). The authors examined the semantic formulas employed in native and non-native requests. One of the most remarkable results of their analysis involved “length of utterance” which is the number of words used in each sequence. Opposing to the expectations, they discovered that the learners in their study used more external modification, and thus more words, than the native speakers to convey their requests. Such findings were surprising as one would normally expect that learners, who have more limited linguistic means, would be less verbose than native speakers, and they would naturally have a tendency to talk less.

Using “too many words”, Blum-Kulka and Olshtain claimed, was an important factor leading to pragmatic failure. Exmaples from their data revealed that excessive talk by learners was often inappropriate, overly-informative, irrelevant, and confusing. The present study also examines the response length and possible explanations for increases in response length are discussed. While the findings clearly are not comparable with the results of studies on length of

utterance, some of the discussion regarding learner verbosity can be considered her, particularly discussion of how learner’s responses vary from native speakers, and may lead to pragmatic failures.

In the area of cross-cultural pragmatics, it has been always difficult for researchers to capture the authenticity, creativity and richness of natural speech while trying to control the many variables inherent in language use so that data from different individuals can be

meaningfully compared (Eisenstein,1995). Ebsworth (1992) & Bodman – Eisenstein (1988) have come up with an approach that combines natural observation and elicited data in their researches. In this study I adopted their data collection method.

I started with observing greetings among natives and non-natives as they occurred in natural discourse with different occasions. On the basis of these natural data, an open-ended questionnaire was designed containing six situations in which different kinds of greetings typically occurred. After analyzing the data collected from the questionnaire, a group of participants were selected based on their answers, and interviewed to stimulate more explanations about their responses to the different scenarios in the questionnaire.