CHAPTER FOUR DISCUSSION

The findings of the present study will be further interpreted in this chapter. I will first address the issues of second language acquisition in section 4.1. Next, I will discuss some linguistic issues in section 4.2. Finally, I will summarize the main points of this chapter in section 4.3.

4.1 SLA Issues

The study of SLA discusses a variety of topics such as the influence of L1 on L2 acquisition (cf. Schachter 1983, Ringbom 1987, Ard and Homburg 1992, Laufer &

Eliasson 1993, Gass & Selinker 1992, 2001), the effects of a critical period on language acquisition (cf. Johnson & Newport 1989, Bialystok & Hakata 1999, Flege 1999), and the existence of UG (cf. White 1989, Kaltenbacher 2001), etc. In this section, I will only focus on the role of L1 in L2 acquisition and the effects of methodology.

4.1.1 L1 Transfer

There have been many studies on the influence of L1 on SLA (cf. Schachter1983, Ringbom 1987, Ard and Homburg 1992, Laufer & Eliasson 1993, Gass & Selinker 1992, 2001). As concerned with the similarities between L1 and L2, Ringbom (1987) and Ard & Homburg (1992) claim that because of the existence of the similarities, L2 learners can focus on differences between the two languages, thereby facilitating learning. As for the differences between L1 and L2, Laufer and Eliasson (1993) claim that L2 learners tend to avoid the differences between L1 and L2 and apply their L1 knowledge to the acquisition of L2. In this study, I will examine how similarities and

differences between Chinese and English quantificational scope interpretations influence Chinese-speaking learners’ acquisition of English QNPs.

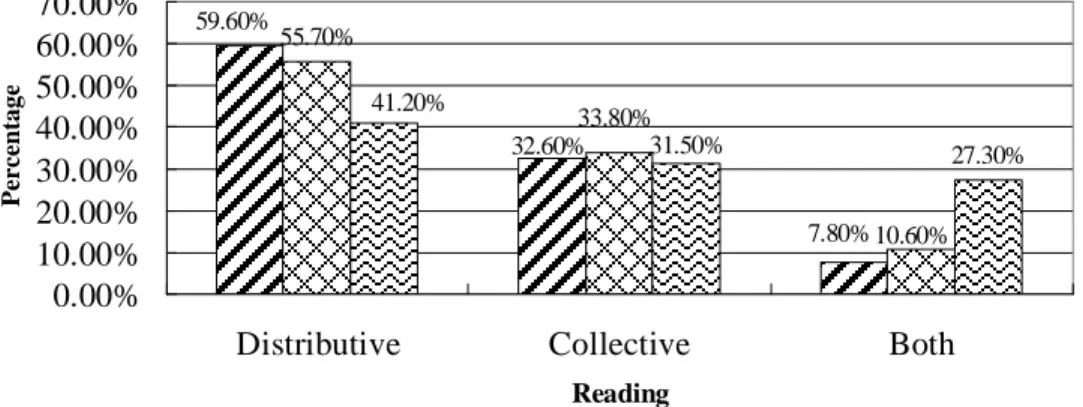

As discussed in Chapters One and Two, English exhibits scope ambiguity more freely than Chinese and linearity is a strong principle assumed by most Chinese in their understanding of scope, which is not relevant for English speakers to interpret QNPs. That is to say, Chinese speakers prefer the preceding QNP to have a wide scope interpretation more than English speakers do. In what follows, let us see whether L1 plays an influential role in Taiwanese students’ acquisition of English QNPs. Our subjects’ interpretations of sentences with a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP are shown in Figure 4-1:

55.70%

27.30%

32.60%

7.80%

59.60%

33.80%

10.60%

31.50%

41.20%

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

High School Students College Students English Speakers

Figure 4-1: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP1

As can be seen in Figure 4-1, more than fifty percent of the subjects in the experimental groups chose the distributive reading and the high school students preferred the distributive reading more than the college students. Compared with the

1 The percentages were derived by summing up all the frequencies of one reading of one group in both tasks and then dividing the summed-up frequencies by the number of each group.

English control group, the two experimental groups had higher percentages of choosing the distributive reading and were less aware of the ambiguous reading of the test sentences. The Chi-square test showed that the differences between the two experimental groups and the English native controls were significant (χ2 = 102.148, p < 0.001). Posterior comparisons further indicated that the English learners significantly differed from the English speakers in the distributive and ambiguous readings, shown in the gray areas in Table 4-1:

Table 4-1: A Comparison of Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with a Universal QNP preceding an Existential QNP

Reading

Groups Distributive Collective Both

E1 vs. E2 0.039 ± 0.080 0.012 ± 0.076 0.028 ± 0.047 E1 vs. NE 0.184 ± 0.092 0.011 ± 0.087 0.195 ± 0.073 E2 vs. NE 0.145 ± 0.093 0.023 ± 0.088 0.167 ± 0.075

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

Table 4-1 indicates that the high school students, low English achievers, did not exhibit any significant differences from the college students, high English achievers, in the three readings. However, the two experimental groups significantly differed from the English native controls in the distributive and ambiguous readings. That is, the experimental groups had higher preferences for the distributive reading and the English native controls indeed were more aware of the ambiguous reading. Evidently, the linearity principle was more relevant for the experimental groups than for the English speakers while they were interpreting sentences in which a universal QNP preceded an existential QNP. Accordingly, L1 was influential for our high school students and college students to interpret English QNPs.

The above analyses show that L1 had some influence on the English learners’

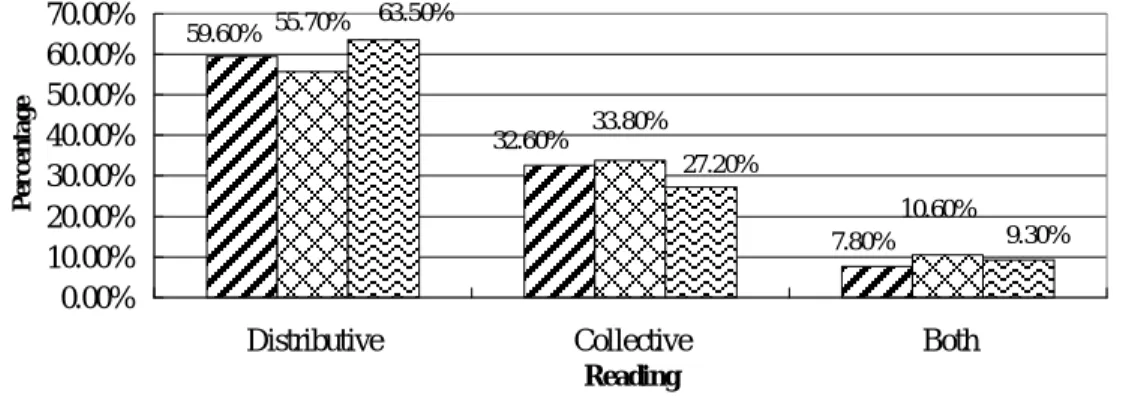

interpretations of English QNPs. However, one question arises. Did our English learners apply their L1 knowledge to interpreting English QNPs or they were at the interlanguage stage? If they applied their L1 knowledge of QNPs to interpret English QNPs, there would be no differences between our English learners’ interpretations of English QNPs and the Chinese speakers’ interpretations of Chinese QNPs. If the English learners were at the interlanguage stage, the linearity principle would be less relevant for them than for Chinese speakers. Let us look at Figure 4-2, which compares the English learners’ interpretations of English QNPs with the Chinese speakers’ interpretations of Chinese QNPs:

7.80%

59.60%

32.60%

10.60%

33.80%

55.70%

9.30%

27.20%

63.50%

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

High School Students College Students Chinese Speakers

Figure 4-2: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP

Figure 4-2 reveals that compared with the Chinese speakers, the high school students and the college students had lower percentages of the distributive reading and higher percentages of the collective reading. However, the Chi-square test indicated that the differences were not significant (χ2 = 9.035, p> 0.05)2. That is,

2 If the contingency table is 3 x 3, χ2 must be greater than 9.488; then, the difference will be significant.

our English learners’ interpretations of English QNPs were similar to our Chinese speakers’ interpretations of Chinese QNPs.

Table 4-2 gives us a more detailed description of the similarities between the three groups’ interpretations of QNPs, where the Chi-square values were derived from the three groups’ readings:

Table 4-2: Chi-Square Values for Subjects’ Interpretations of QNPs with a Universal QNP preceding an Existential QNP

Problem-Solving Task Picture-Selection Task Type

Group SA3 SP DO Da SC OC SA SP DO Da SC OC

N1 2.045 2.089 1.047 3.783 0.263 1.047 5.889 0.488 0.750 0.000 3.369 0.212 E1

vs.

NC N2 2.512 0.563 0.000 2.056 1.047 0.549 1.800 1.993 0.869 0.900 5.778 0.421 N1 4.084 5.753 1.607 0.223 5.885 4.145 2.392 0.464 0.450 1.015 0.667 1.950 E2

vs.

NC N2 1.262 1.560 1.607 0.467 2.813 2.013 5.954 3.170 1.049 0.000 5.444 0.830

* If the contingency table is 2 x 3, χ2 must be greater than 5.991; then, the difference will be significant.

Table 4-2 indicates that in response to every question, our high school students and college students did not exhibit any significant difference from the Chinese native controls. That is, our high school students’ and college students’ interpretations of English QNPs were similar to the Chinese speakers’ interpretations of Chinese QNPs.

However, the English learners’ interpretations of QNPs were different from the English control group’s. This implies that the English learners have applied their L1 knowledge to interpreting English QNPs.

After discussing the subjects’ interpretations of QNPs in the sequence of a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP, let us see whether the linearity principle

3 SA: simple active constructions, SP: simple passive constructions, DO: double object constructions, Da: dative constructions, SC: subject control constructions, OC: object control constructions

was also relevant for the English learners to interpret English sentences where an existential QNP preceded a universal QNP, as shown in Figure 4-3:

6.90%

19.20%

74.20%

6.70%

24.80%

74.30%

18.80%

50.00%

25.20%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

High School Students College Students English Speakers Figure 4-3: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with an Existential QNP

Preceding a Universal QNP

As shown in Figure 4-3, more than seventy-four percent of our high school students and college students preferred the collective reading, which was twenty-four percent more than the English speakers’ percentage of the collective reading.

Therefore, English learners’ liked the collective reading more than the English native controls. Similar to what Figure 4-1 shows, Figure 4-3 also indicates that our English learners were less in favor of the ambiguous reading than the English control group.

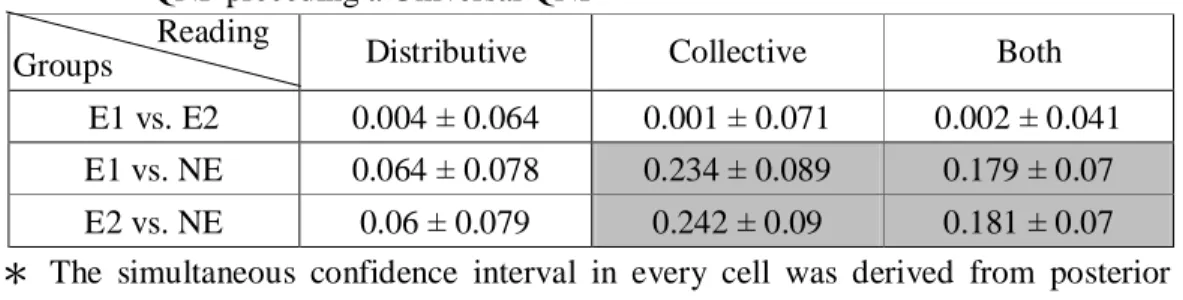

According to the Chi-square test, the differences I just described between the English learners and English speakers were significant (χ2 = 132.816, p < 0.001). Posterior comparisons show more group differences, as in Table 4-3:

Table 4-3: A Comparison of Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with an Existential QNP preceding a Universal QNP

Reading

Groups Distributive Collective Both

E1 vs. E2 0.004 ± 0.064 0.001 ± 0.071 0.002 ± 0.041 E1 vs. NE 0.064 ± 0.078 0.234 ± 0.089 0.179 ± 0.07 E2 vs. NE 0.06 ± 0.079 0.242 ± 0.09 0.181 ± 0.07

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

The gray areas in Table 4-3 show that our experimental groups’ collective and ambiguous readings were significantly different from the English native controls’

while they interpreted sentences with an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP.

In addition to the reason of the linearity principle, the two experimental groups’ high percentage of choosing the collective reading may be due to the constraint4 on the occurrence of existential QNPs (like yige and sange) in the subject position in Chinese (Hudson 1986, Lee 1986) 5. In the present study, two-thirds of the English test sentences where an existential QNP preceded a universal QNP had an existential QNP in the subject position, and this sequence is ungrammatical in Chinese when you does not precede the existential QNP.

4 Hudson (1986) and Lee (1986) claim that Chinese generally does not allow an indefinite NP in the subject position unless the subject is preceded by you ‘exist, have’

5 I also did an experiment to prove Hudson’ (1986) and Lee’ (1986) claims. In my experiment, you was inserted to all the Chinese test sentences with an existential QNP in the subject position; therefore, there were 8 test sentences in the problem-solving task and 8 sentences in the picture-selection task.

Table (i) The Percentage of Three Readings in Both Tasks Reading

Task Distributive Collective Both

The Problem-Solving Task 5 % 95 % 0

The Picture-Selection Task 0.8 % 95 % 4.2 %

Table (i) shows that in the two tasks when you preceded an existential QNP, ninety-five percent of the Chinese speakers chose the collective reading.

In order to demonstrate that the violation of such sequence might make our English learners choose the collective reading more than the English native controls, let us compare the similarities and differences among the four groups of subjects with respect to their interpretations of sentences with an existential QNP in the subject position. The percentages shown in Figure 4-4 were obtained by excluding double object and dative constructions, in which existential QNPs were not in the subject position:

82.70%

3.30%

17.70%

30%

13.30%

80.40%

6.30%

10.80%

6.50%

88.30%

8.30%

52.30%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

High School Students College Students Chinese Speakers English Speakers

Figure 4-4: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with an Existential QNP in the Subject Position

In Figure 4-4, we can see that the percentages of our English learners’ and the Chinese native controls’ collective readings increased to more than eighty percent, which were much higher than the English native controls’. The Chi-square test showed that the English learners responded significantly differently from the English native controls (χ2 = 104.077, p < 0.001). However, they did not exhibit any significant differences from the Chinese native controls in interpreting sentences with an existential QNP in the subject position (χ2 = 7.985, p > 0.05). As shown above, their percentages of the collective readings were high and their percentages of the collective readings for sentences with an existential QNP in the subject position were

higher than those for sentences with an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP, which included double object and dative constructions (E1: 80.40 % & 74.30 %; E2:

82.70 % & 74.20 %; NC: 88.30 % & 78.60 %). The fact that our English learners and Chinese native controls tended to choose more collective readings might have to do with their preference for having you preceding existential QNPs in the subject position. No differences between our English learners and Chinese control group were found significant, but there were significant differences between the English learners and English speakers, showing that the English learners indeed have applied their L1 knowledge to interpreting English QNPs.

Figure 4-5 presents our English learners’ and Chinese native controls’

interpretations of QNPs; double object and dative constructions were considered this time:

18.80%

74.30%

6.90%

19.20%

6.70%

74.20%

16.70%

78.60%

4.70%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

High School Students College Students Chinese Speakers

Figure 4-5: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP

The Chi-square test indicated that our subjects were not significantly different from each other in interpreting QNPs (χ2 = 3.586, p > 0.05). Table 4-4 gives us a more detailed description of the similarities between the three groups’ interpretations of QNPs:

Table 4-4: Chi-Square Values for Subjects’ Interpretations of QNPs with an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP

Problem-Solving Task Picture-Selection Task Type

Group SA SP DO Da SC OC SA SP DO Da SC OC

N1 0.000 1.839 3.452 2.276 2.211 2.946 0.675 0.142 2.049 5.534 0.262 3.545 E1

vs.

NC N2 0.000 5.782 0.511 3.125 1.015 0.750 0.750 0.000 1.196 2.811 0.403 1.607 N1 0.000 2.171 2.000 1.610 4.341 1.875 0.750 0.867 0.304 0.621 2.512 2.182 E2

vs.

NC N2 0.511 5.782 2.813 1.050 2.045 0.262 2.512 2.813 5.513 2.861 4.555 1.607

* If the contingency table is 2 x 3, χ2 must be greater than 5.991; then, the difference will be significant.

Table 4-4 indicates that our experimental groups did not respond differently from the Chinese native controls. That is to say, our English learners seemed to rely on their L1 knowledge in interpreting English QNPs.

The above analyses show that L1 knowledge was quite influential to our subjects when interpreting English QNPs. In other words, it is hard for L2 learners to acquire the interpretations of QNPs in their target language.

4.1.2 Methodology Effect

The effect of methodology, as it has been widely considered by second language researchers (Cook 1993, Crane & Thornton 1998), is another concern of the present study. In the present experiment, two tasks were designed: a problem-solving task (PRS) and a picture-selection task (PIS). In this section, I am going to discuss whether there was any task effect.

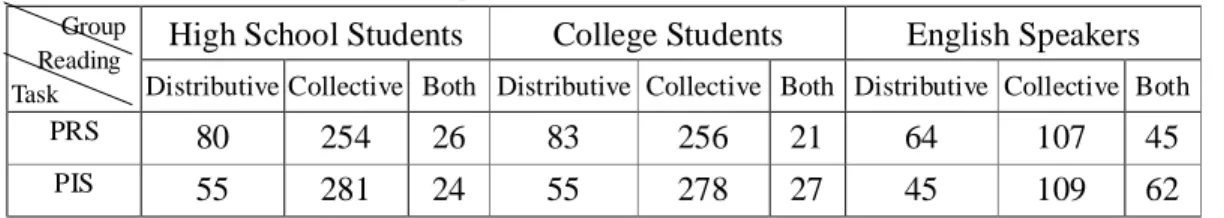

Presented in Table 4-5 are the subjects’ readings in the two tasks in which the test sentences contained a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP:

Table 4-5: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP (frequency counts)

High School Students College Students English Speakers

Group Reading

Task Distributive Collective Both Distributive Collective Both Distributive Collective Both

PRS 250 93 17 241 86 33 123 57 36

PIS 158 163 39 160 157 43 55 79 82

As we can see in Table 4-5, for each group the frequency of the distributive reading in the PRS task was higher than that in the PIS task and the frequencies of the collective and the ambiguous readings were higher in the PIS task than in the PRS task.

Presented in Table 4-6 are the subjects’ interpretations of sentences with an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP:

Table 4-6: Subjects’ Interpretations of Sentences with an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP (frequency counts)

High School Students College Students English Speakers

Group Reading

Task Distributive Collective Both Distributive Collective Both Distributive Collective Both

PRS 80 254 26 83 256 21 64 107 45

PIS 55 281 24 55 278 27 45 109 62

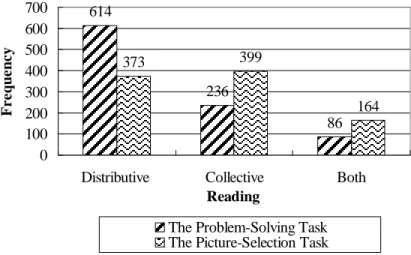

Even though the sequence of QNPs was different from that shown in Table 4-5, we got similar results that for each group the frequency of the distributive reading in the PRS task was higher than that in the PIS task and the frequency of the collective reading was higher in the PIS task than in the PRS task. By summing up the frequencies, we can get the Chi-square values and the frequencies of readings of each task with the sequence of a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP, as shown in Figure 4-6:

614

236

86

373 399

164

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Distributive Collective Both Reading

Frequency

The Problem-Solving Task The Picture-Selection Task

Figure 4-6: Frequency Counts of Each Reading for the Sequence of a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP

As can be seen in Figure 4-6, the frequency of the distributive reading of the PRS task was higher than that of the PIS task and the frequencies of the collective and of the ambiguous readings in the PRS task were lower than those in the PIS task.

Chi-square revealed that the two tasks were significantly different in the distributive reading, in the collective reading, and in the ambiguous reading (χ2 = 147.575, p <

0.001; ψ of the distributive reading = 0.279 ± 0.054, ψ of the collective reading = 0.196 ± 0.052, ψ of the ambiguous reading = 0.083 ± 0.038) when a universal QNP preceded an existential QNP.

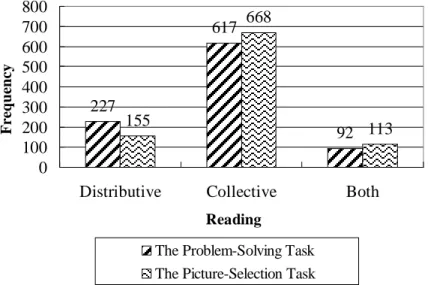

Figure 4-7 presents the frequency counts of readings for the sequence of an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP:

227

617

155 92

668

113 0

100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Frequency

The Problem-Solving Task The Picture-Selection Task

Figure 4-7: Frequency Counts of Each Reading for the Sequence of an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP

Similar to the findings shown in Figure 4-6, it was found that compared with the frequencies of readings in the PIS task, the frequency of the distributive reading in the PRS task was higher and those of the collective reading and ambiguous reading were lower. Chi-square and posterior comparisons showed that the two tasks were significantly different in the distributive reading, in the collective reading, but not in the ambiguous reading (χ2 = 17.746, p < 0.001; ψ of the distributive reading = 0.077± 0.046, ψ of the collective reading = 0.055 ± 0.053).

The above analyses showed that there were methodology effects on our subjects’

interpretations of English QNPs. As for the sequence of a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP, there were task effects on the subjects’ choices of the three readings.

With respect to the sequence of an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP, the two tasks differed in the distributive and collective readings.

4.2 Linguistic Implications

In this section, I would like to see if there is any construction effect on EFL

learners’ interpretations of QNPs and to see if the construction effect (if any) on the EFL learners were different from that on the English native controls. Besides, I will discuss the sequence effect on the readings of QNPs.

4.2.1 Construction Effect

As discussed in Chapter Two, Aoun and Li (1989) state that simple active, simple passive, dative, and object control constructions containing more than two QNPs are ambiguous in English and that simple passive, and dative constructions with more than two QNPs are ambiguous in Chinese. Kuno et al. (1999) claim that syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, and idiosyncratic factors can help determine the quantifier scope interpretations of a given sentence. All these researchers agree that syntax has influence on the subjects’ interpretations of QNPs.

Figure 4-8 illustrates our English learners’ readings of different constructions with a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP:

37.5%

5.8%

75.8%

67.9%

22.9%

9.2%

51.3%

11.3%

16.7%

77.5%

17.5%

19.2% 6.7%

69.2%

11.7%

62.5%

27.1%

10.4%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

Simple Active Simple Passive Double Object

Dative Subject Control Object Control

Figure 4-8: English Learners’ Interpretations of Constructions with a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP

As Figure 4-8 shows, the percentage of the distributive reading of the double object construction was higher than that of the other syntactic constructions, especially higher than that of the dative construction. As for the percentage of the collective reading of these constructions, the dative construction was ranked top 1.

Moreover, compared with the percentages of the distributive and of collective readings of other constructions, we found that the distributive reading and the collective reading did not differ much in the simple passive construction (13.8 %).

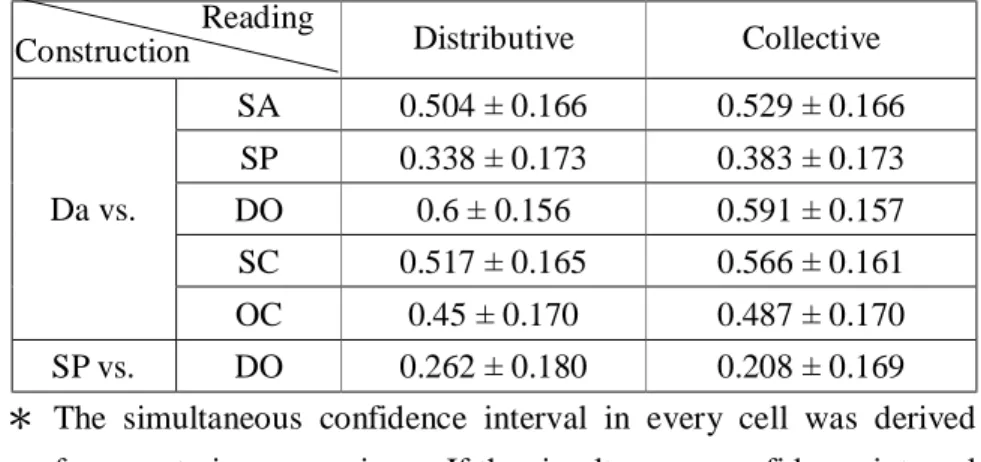

The reason why the simple passive construction with two QNPs is ambiguous might be due to the slight difference between the two readings of the simple passive construction. Chi-square indicated that there was a significant difference in the readings of these constructions (χ2 = 280.957, p < 0.001). Posterior comparisons further provide us with the similarities and differences between these constructions, as can be seen below:

Table 4-7: Posterior Comparisons of the Readings Shown in Figure 4-8 Reading

Construction Distributive Collective

SA 0.504 ± 0.166 0.529 ± 0.166

SP 0.338 ± 0.173 0.383 ± 0.173

DO 0.6 ± 0.156 0.591 ± 0.157

SC 0.517 ± 0.165 0.566 ± 0.161

Da vs.

OC 0.45 ± 0.170 0.487 ± 0.170

SP vs. DO 0.262 ± 0.180 0.208 ± 0.169

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

As can be seen in Table 4-7, the distributive and collective readings of the dative construction were significantly different from the readings of the other constructions.

For the dative construction, the following QNP had a wide scope interpretation, but

for the other constructions, the preceding QNP had a wide scope interpretation. In addition, the distributive and collective readings of the simple passive construction significantly differed from those of the double object construction. The reason for the differences between the simple passive and the double object constructions was that the subjects’ preference for the preceding QNP to have a wide scope interpretation in the simple passive construction was not as strong as that in the double object construction. Posterior comparisons also showed that all the six constructions did not display any difference in the ambiguous reading.

Figure 4-9 illustrates our English learners’ readings of different syntactic constructions containing an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP:

1.7%

80.8%

5.4% 4.2%

2.5%

95.8%

27.5%

9.2%

63.3%

13.8%

51.7%

10.0%

38.3%

88.3%

7.5%

11.7%

78.8%

9.6%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

120.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Perventage

Simple Active Simple Passive Double Object

Dative Subject Control Object Control

Figure 4-9: English Learners’ Interpretations of Constructions with an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP

In Figure 4-9, we can see that the percentage of the distributive reading of the dative construction was higher than that of the other constructions and that except the dative construction the percentage of the collective reading of the other five constructions, especially of the simple active construction, was high. For the English learners, the English dative construction with an existential QNP preceding a

universal QNP was indeed ambiguous, because some of the subjects chose the distributive reading (51.7 %) and some chose the collective reading (38.3 %). Since we discussed in section 4.1 that our English learners seemed to have applied their L1 knowledge of QNPs to interpreting English QNPs6, their interpretations of English QNPs might reflect their L1 knowledge of Chinese QNPs. Accordingly, the subjects’

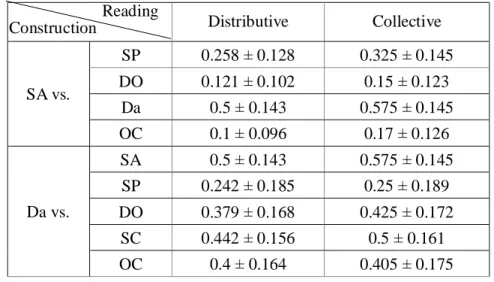

interpretations of QNPs in the dative construction were predicted by Aoun and Li (1989), who claimed the dative construction with two QNPs in Chinese was ambiguous. The Chi-square test showed that the readings of these constructions were significantly different (χ2 = 296.353, p < 0.001). Posterior comparisons showed more detailed information of these differences:

Table 4-8: Posterior Comparisons of the Readings Shown in Figure 4-9 Reading

Construction Distributive Collective

SP 0.258 ± 0.128 0.325 ± 0.145

DO 0.121 ± 0.102 0.15 ± 0.123

Da 0.5 ± 0.143 0.575 ± 0.145

SA vs.

OC 0.1 ± 0.096 0.17 ± 0.126

SA 0.5 ± 0.143 0.575 ± 0.145

SP 0.242 ± 0.185 0.25 ± 0.189

DO 0.379 ± 0.168 0.425 ± 0.172

SC 0.442 ± 0.156 0.5 ± 0.161

Da vs.

OC 0.4 ± 0.164 0.405 ± 0.175

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

6 58.3 % of the Chinese native controls chose the distributive reading of the dative construction, 31.7%

of them chose the collective reading, and 10 % chose the ambiguous reading. Their interpretations of Chinese QNPs in the dative construction were not different from the English learners’ interpretations of English QNPs in the English dative construction.

As presented in Table 4-8, the distributive and collective readings of the simple active construction were significantly different from those of the simple passive, double object, dative, and object control constructions, because the linearity principle had stronger influence on the simple active construction than on the others. Similar to the dative construction containing a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP, the dative construction here also exhibited significant differences from the other constructions in the distributive and collective readings.

From the above discussion, we know that the readings of the dative construction were significantly different from the other constructions, regardless of the sequence of QNPs. The reason why the following QNP in the dative construction had a wide-scope interpretation than the preceding QNP might be the derivation of the dative construction from the double object construction (Aoun & Li 1989).

Now let us discuss the construction effect on the English native controls’

interpretations of QNPs, as shown in Figure 4-10:

69.4%

75.0%

56.9%

26.4% 29.2%

16.7%

54.2%

31.9%

54.2%

13.9%

23.6%

6.9% 12.5%

12.5%

33.3%

9.7%

33.3%

40.3%

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

80.00%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

Simple Active Simple Passive Double Object

Dative Subject Control Object Control

Figure 4-10: English Native Controls’ Interpretations of Constructions with a Universal QNP Preceding an Existential QNP

Figure 4-10 shows that the preceding universal QNP had a wide-scope interpretation in the simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions; however, the following existential QNP had a wide-scope interpretation in the simple passive and dative constructions. Compared with the English learners’ ambiguous readings of QNPs in the constructions shown in Figures 4-8 and 4-9, the English native controls’ ambiguous readings of QNPs were higher.

Chi-square showed that the differences in readings between these constructions were significant (χ2 = 142.658, p < 0.001). Posterior comparisons presented in Table 4-9 showed that the distributive and collective readings of the simple passive construction and of the dative construction were significantly different from those of the simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions:

Table 4-9: Posterior Comparisons of the Readings Shown in Figure 4-10 Reading

Construction Distributive Collective

SA 0.403 ± 0.306 0.375 ± 0.314

DO 0.555 ± 0.291 0.473 ± 0.282

SC 0.43 ± 0.305 0.445 ± 0.292

SP vs.

OC 0.264 ± 0.241 0.278 ± 0.270

SA 0.417 ± 0.302 0.583 ± 0.288

DO 0.569 ± 0.286 0.681 ± 0.253

SC 0.444 ± 0.301 0.653 ± 0.265

Da vs.

OC 0.278 ± 0.269 0.486 ± 0.312

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

The simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions had similar readings. The readings of the simple passive and dative

constructions were also similar. Furthermore, the ambiguous readings of all the constructions were not different.

Now let us discuss the similarities and differences in the readings of QNPs in different constructions, as shown in Figure 4-11:

8.3%

56.9%

27.8%

63.9%

22.2%

20.8%

18.1%

70.8%

11.1%

26.4%

4.2%

69.4%

23.6%

73.6%

2.8%

30.6%

66.7%

2.8%

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

80.0%

Distributive Collective Both

Reading

Percentage

Simple Active Simple Passive Double Object

Dative Subject Control Object Control

Figure 4-11: English Native Controls’ Interpretations of Constructions with an Existential QNP Preceding a Universal QNP

Similar to the previous findings, Figure 4-11 shows that the preceding QNP of the simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions had a wide-scope interpretation and that the following QNP of the simple passive and dative constructions had a wide-scope interpretation for the English native controls.

The Chi-square test indicated that the differences between these constructions were significant (χ2 = 193.498, p < 0.001), as shown in Table 4-10:

Table 4-10: Posterior Comparisons of the Readings Shown in Figure 4-11 Reading

Construction Distributive Collective

SA 0.486 ± 0.286 0.431 ± 0.317

DO 0.458 ± 0.296 0.5 ± 0.307

SC 0.541 ± 0.263 0.528 ± 0.302

SP vs.

OC 0.541 ± 0.263 0.459 ± 0.314

SA 0.611 ± 0.271 0.597 ± 0.262

DO 0.583 ± 0.281 0.666 ± 0.251

SC 0.666 ± 0.247 0.694 ± 0.244

Da vs.

OC 0.666 ± 0.247 0.625 ± 0.258

* The simultaneous confidence interval in every cell was derived from posterior comparisons. If the simultaneous confidence interval includes the number, zero, it means there is no significant difference.

The results shown in Table 4-10 are similar to those given in Table 4-9. The distributive and collective readings of the simple passive and dative constructions were significantly different from those of the other constructions. Furthermore, the English native controls’ interpretations of QNPs in the simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions were similar and they also had similar interpretations’ of QNPs in the simple passive and dative constructions.

As discussed above, there was a construction effect on the subjects’

interpretations of QNPs and the construction effects on the English learners and on the English native controls was not the same. However, for all the subjects, the following QNP in the dative construction had a wide-scope interpretation. Aoun and Li’s (1989) claim that the dative construction is derived from the double object construction may be the reason for the following QNP in the dative construction to have a wide-scope interpretation. I assume that there might be some derivation impact on the subjects’ interpretations of QNPs in the derived constructions. My assumption

could also be supported by the English native controls’ preference for the following QNP in the simple passive construction, which is derived from the simple active construction, to have a wide scope interpretation. For the English learners, even though the preceding QNP in the simple passive construction had a stronger wide-scope interpretation than the following QNP, a high percentage of the wide-scope interpretation of the preceding QNP in the simple active, double object, subject control, and object control constructions was not obtained in the simple passive construction. Therefore, there may be some derivation impact on the subjects’

interpretations of QNPs in the dative and simple passive constructions. But further research will be necessary.

Many researchers (cf. Huang 1983, May 1985, Aoun & Hornstein 1985, Aoun &

Li 1989, Hornstein 1995) discuss the (non-) ambiguity of QNPs in syntactic constructions. However, as shown in Figures 4-8, 4-9, 4-10, and 4-11, we can only see that the preceding QNP in some constructions had a stronger (not absolutely) wide-scope interpretation than the following QNP and that the ambiguity property of some syntactic constructions (like the simple passive construction) was more conspicuous than others.

4.2.2 Sequence Effect

The effect of the sequence of QNPs is another concern of this study. The sequences of QNPs discussed in the study were a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP and an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP. In this section, I am going to discuss the sequence effect on the English learners’ and English native controls’ interpretations of QNPs.

Presented in Figure 4-12 are the English learners’ interpretations of QNPs:

74.20%

57.60%

33.20%

9.20%

19.00%

6.80%

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

80.00%

Preceding Wide Following-Wide Ambiguous Reading

Percentage

U + E E + U

Figure 4-12: English Learners’ Interpretations of QNPs in Different Sequences

In Figure 4-12, we can see that in both sequences of QNPs, especially when an existential QNP was the preceding one, the preceding QNP had more a stronger wide-scope interpretation than the following QNP. Besides, the percentage of the wide-scope interpretation of the preceding QNP in the sequence of an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP was higher than that of the preceding QNP in the other sequence7. In contrast, the percentage of the wide-scope interpretation of the following QNP in the sequence of a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP was higher than that of the following QNP in the other sequence. Chi-square and the posterior comparisons showed that the differences between the two sequences in the wide-scope interpretation of the preceding QNP and in the wide-scope interpretation of the following QNP were significant (χ2 = 91.064, p < 0.05; ψ of the wide scope interpretation of the preceding QNP = 0.166 ± 0.078, ψ of the wide scope

7 In the sequence of an existential QNP preceding a universal QNP, the wide-scope interpretation of a preceding existential QNP was the collective reading; the wide-scope interpretation of the following universal QNP was the distributive reading. In the sequence of a universal QNP preceding an existential QNP, the wide-scope interpretation of a preceding existential QNP was the distributive reading; the wide-scope interpretation of the following universal QNP was the collective reading.

interpretation of the following QNP = 0.142 ± 0.072). Therefore, there was a sequence effect on the English learners’ interpretations of QNPs.

However, the sequence effect discussed above on the English learners’

interpretations of QNPs was gone in the dative construction, in which the following QNP had a stronger wide-scope interpretation than the preceding QNP.

Shown in Figure 4-13 is the sequence effect on the English native controls’

interpretations of QNPs:

27.30%

31.50%

41.20%

24.80%

50.00%

25.20%

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

Preceding-Wide Following-Wide Ambiguous Reading

Percentage

U + E E + U

Figure 4-13: English Native Controls’ Interpretations of QNPs in Different Sequences

Similar to the sequence effect on the English learners’ interpretations of QNPs, the preceding QNP had a stronger wide-scope interpretation than the following QNP in each sequence for the English native controls. The percentage of the wide scope interpretation of the preceding existential QNP was higher than that of the preceding universal QNP. However, the percentage of the wide-scope interpretation of the following QNP in the sequence of an existential QNP as the preceding one was lower than that of the following QNP in the other sequence. The Chi-square test demonstrated that the difference between the two sequences in the wide-scope

interpretations of the preceding QNP was significant (χ2 = 7.178, p < 0.05; ψ of the wide scope interpretation of the preceding QNP = 0.088 ± 0.083). Accordingly, the sequences displayed significant differences in the English native controls’

interpretations of QNPs.

However, the sequence effect on the English native controls’ interpretations of QNPs was gone in the simple passive and dative constructions, in which the following QNP had a stronger wide-scope interpretation than the preceding QNP.

Figures 4-12 and 4-13 show that there was a sequence effect on the subjects’

interpretations of QNPs.

4.3 Summary of Chapter Four

In this chapter, I have further interpreted the findings of the present study. In section 4.1, SLA issues, such as L1 transfer and methodology, have been discussed. It was found that the high achievers and low achievers did not exhibit any significant differences in interpreting QNPs because their L1 knowledge was influential. It was found that compared with the frequencies of the readings in the PIS task, the frequency of the distributive reading in the PRS task was higher and those of the collective reading and ambiguous reading were lower; therefore, a methodology effect on the subjects’ interpretations of QNPs was obtained. In section 4.2, I have discussed two linguistic issues, the construction effects and the sequence effects. There were construction effects and the construction effects on the English learners and on English native controls were not the same. Besides, a sequence effect on the subjects’

interpretations of QNPs was found. In the next chapter, I will report the limitations of the present study and suggest some topics for further research.