State-owned Enterprise Reform in People’s

Republic of China

Kuo-Tai Cheng

Abstract

China’s transition from a planned to a market economy achieved remarkable success through a gradual approach. Such transition was accompanied by the transformation of public enterprises. This paper is to explore the reform of SOEs in PRC and its problems. The transformation of SOEs towards shareholding system corporation is aimed to clarify property rights and strengthen enterprise governance structure and internal management. Up to now, the biggest problem of SOE reform is the absence of the management subject of state property ownership, that is, to clearly define the ownership representative of state assets of enterprises. Another critical challenge has ideological chaos, nonstandard operation of shareholding system, old wine in new bottle and etc. In this study, the transformation of public enterprises has been more likely to be successful when achieved through a gradual approach, as ownership change has constraints, and preconditions such as supporting institutions, which takes time to establish and function in an emerging new market environment. It can be argued that the reform of SOEs stays at the heart and remains the most difficult task of China’s economic reform. Therefore, it is expected that the government will accelerate the transformation of the ownership system despite bankruptcies and unemployment, and that the new wave of SOEs and corporate-owned enterprises reform, featured as a shareholding cooperative system, is to sweep China in the next few years.

Keywords: State-owned enterprise, People’s Republic of china, Chinese Communist party, management, transition, ownership

1.Background

China was once considered as the cradle of civilization in the East. This large country has seen an enormous number of civil wars and developments in its

approximately five thousand years history. In the process, famous ideologies such as Confucianism and Taoism have occurred and have had great influence on the way the country was governed. The feudal state existed for thousands of years until the Jing dynasty, during which different European countries began to attack China and some occupied parts of the country. A capitalist revolution broke out and then was

overtaken by the 1949 revolution under the leadership of Mao Zedong. The People's Republic of China (PRC) was then established with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at the heart of the political system.

The CCP, with its absolute power, increasingly controlled the entire administrative system. The will of the party was superior to the rule of law;

consequently, the principle of legality played only a secondary role in administration. At all levels, party secretaries were usually the chiefs of the executives. The

domination of the party also meant excessive interference of the state in the economy, its over-bureaucratic centralisation and concentration of decision-making over

economic production. The government and its bureaucracies were directly involved in managing and running public enterprises - from making production plans and

investment, deciding on employment and market, to determining product

consumption and pricing. Such an over-interference (which separated production from market and management from economic accounting) has resulted in waste of human and material resources, sluggishness and ineffectiveness and inefficiency of the entire national economy.

As in most of the ex-socialist economies, all activities, including manufacturing, mining, service and banking in China in the pre-reform period, were in the state sector. Agriculture was largely collectivised and domestic trade was organized by

state-controlled marketing and distribution agencies. The allocation of labour, materials and financial resources was related to anticipated requirements for achieving predetermined supply objectives. Under this scheme, the production and consumption of products was coordinated. Nixson, Kirkpatrick& Cook (1998, p: 7) argued:

co-ordinate human resources with output requirements. Financial balances were concerned with the creation and distribution of money income. Finally, demand elasticities were estimated and used to balance supply and demand.

In principle, where imbalances were found, adjustments were made by the state either to supply (through increasing output, technological improvements or

substitution of inputs) or demand (curtailing wants or requirements).

The public administration of China is organized in three levels: a central level, a provincial layer, and a local apparatus. In 1997 there were 30 provinces or

provincial-level units, comprising 22 provinces, five autonomous regions, and three centrally-governed special municipalities. The lower level consists of 333

autonomous prefectures, counties, 2148 autonomous counties, cities and 697

municipal districts under city administration (Jiaqi, G. & Burns, J. P., 1997, p: 2). The basic level comprises townships and villages. Planning and macro decision-making are largely centralised in Beijing, but because the country is so big, operations and problem-solving are decentralised through provincial and local agencies. The size of this administrative structure has been enormous, reaching nearly 20 million political and administrative officials by 1982. By 1987, there were 98 government ministries and commissions at the central level.

The most distinctive characteristic of the growth in China is the development of non-state enterprises, the share of which increased from 22 percent to 57 percent. Between 1979 and 1993, most of the new Chinese firms are not private firms but local government firms, the majority of which are township and village enterprises (TVEs). The formation of TVEs initially depended on the success of agricultural reform, through the availability of excess rural labour, through savings from income, and through increased demand.

2. Size and Structure

Presently, China has 305,000 state-owned enterprises, excluding 24,000 financial enterprises (Liu & Gao 1999) (some indicates the number of SOEs is over 500,000 (eg. Beijing Review March 22-28 1999, SSB 1998)). Among the SOEs, 95 % of them are small or medium-sized units. Large SOEs only account for 5%, that is, around 16,000. By the end of 1995, the total assets of the 305,000 SOEs had only been 7472.1 billion Yuan (over 900 billion US$), of which non-production assets (for employee houses, schools and hospitals) account for 20%. This indicates that the state assets are too scattered among state enterprises. The total debts was 5176.2 billion Yuan (over 600 billion US$), the average ratio of debts to assets was 69.27% (Liu & Gao 1999).

In 1995 there were 87,900 state-owned industrial enterprises with own budget, accounting for 62% of the total assets of industrial enterprises. By the standard of SSB, there were 15,700 large and medium-sized industrial SOEs and 72,200 small ones (Wu 1999: 195). Liu and Gao (1999) state that, of all industrial enterprises, large enterprises accounts for 5%, medium-sized enterprises 13% and small enterprises 82%. OECF indicates that most of the state industrial enterprises are in mining and manufacturing industries. ‘According to SSB (1996), the number of mining and manufacturing state-owned enterprises is 69,500, of which the number of medium to large sized SOE is 14,800 (cited in OECF 1998:25)’. The total assets of all industrial enterprises are 4952.5 billion Yuan (about 6oo billion US$), among which the assets of state industrial enterprises are 3261.2billion Yuan (about 400 billion US$).

The industry of which assets are 100% of state includes post, airline, and

railway. The sector which has 90% or above of state assets includes petroleum (95%), electricity (91%), coal (90%). The sector which has over 75% state assets consists of metallurgy, finance, gas, water industries. The large SOEs cover industries of railway, post, airline, steel and iron, automobile, petroleum and financial fields. Their shares of taxes submitted to the state account for 85% of those by all SOEs ( Liu & Gao 1999).

In 1996, the total number of large industrial enterprises was 7057, of which SOEs account for 70.09 percent. The output value of the SOEs was 69.89%, assets accounting for 75.98% and 85.45% of employment of the 7057 industrial enterprises. For a long time, the investment rate in state economy has been very high, accounting for over 50% of the total investment. And the state enterprises cover a wide range of industries and sectors.

small as against several billions US dollars of assists of international SOEs. For example, in 1996, the assets of individual large SOE was only 0.692 billion Yuan (about 0.08 billion US$) on an average basis (Liu & Gao 1999). There is a long way to go towards the goal of economy of scale. The lack of economy of scale more obviously appears in the industries of automotive, machinery and steel. For example, in 1995, the total products of over 100 automotive plants were 1.5 million

automobiles. This figure is less than 20% of that produced only by American

Universal Automotive Company itself. Daqing Petroleum and Baoshan Steel are the two largest state enterprises of China, however, the scale of Daqing Petroleum is only about 1/15 of British Petroleum and the scale of Baoshan Steel is only 1/8 or so of Japanese Steel. China’s largest manufacturer of heavy equipment is the First Heavy Machinery Group whose total assets and sales are only equivalent to 1.79% and 0.45% separately of those of German Mannesmann in the same field (see Liu & Gao 1999).

Nevertheless the SOEs have remained a dominant sector and the bedrock of the economy in terms of their shares of employment and fixed assets. Although the government plans to convert all large and medium SOE into share-holding

corporations and to enliven small SOEs through acquisition, merger, leasing, sale, etc. The small SOEs are let to go to private sector or wherever they wish. The immediate visible change in industrial structure so far has been the multiplication of ownership forms. The corporatisation and ‘letting go’ are currently under way, there is a likely prospect for the future –a sharp reduction in the number of SOEs and COEs.

3. Importance of the SOEs

The importance of the SOE sector lies in its dominant status in economy in terms of government fiscal revenue, employment and key social service role. The SOE sector has dominated industrial production and China’s economy for over half a century. Even today, the industrial SOEs account for one third of national production, more than half of total assets, and over half of total investment (their share of total investment rose from 61% to 70% between 1989 and 1994, but decline thereafter). In terms of SOEs’ contributions, the SOEs, as a whole, absorb over half (over

two-thirds in the 1980s) of urban employment and provide about 70% government fiscal income.

was about 63% in 1992 and down to 55% in 1996 (OECF 1998: 31).This is because employment adjustment progressed in the SOE sector. Over 20 million of workers have been laid off from SOE since the mid-1990s, of which more than 10 million have difficulties in finding new jobs. Although the registered urban unemployment rate was only around 3% - 4%, but adding the surplus workers and layoffs in the SOEs, this figure goes right up to double digit. As Liu and Gao (1999) documents that the actual urban unemployment rate had been 18.9% by the end of 1997. And this rate was estimated to be 15.6% in 1998. The serious unemployment has therefore brought in enormous threats to social stability, which intensifies the dilemma of SOE reform and also constitutes a reason why the essential reform of SOEs has been delayed again and again.

Additionally, the importance of SOEs lies in their role in the provision of social security, which let the SOEs act as a social stabilizer. Workers in SOEs could

normally benefit major welfare services (from cradle to grave welfare), such as housing, children education and health care (more details later). OECF (1998) indicates the average amount of social security costs per SOE was 3% of sales revenue. Take housing for example, SOEs are responsible for offering house to employees with free or substantially subsidized rent, only accounting for 5% or so of employee wages. About 20% of the assets of the SOEs are non-production fixed assets, of which the most majority are houses for their employees (Liu & Gao 1999). The SOEs also have to put money in establishing and running schools and hospitals and provide nearly free health care and education for their employees. The Costs on employee health care on their own account for more that 15% of the total amount of wages paid to their employees (Liu & Gao 1999). Besides, employees also rely on the SOE for which they work for their pension. As such, each SOE is almost a mini-

welfare state.

4. Reform Phases of SOEs and Specific Reform

Measures

As mentioned earlier, prior to the reform, the SOEs were fully owned, funded and run by government. The enterprise did not have any decision-making power in production, investment or distribution. All their profits had to be submitted to the government while taking no responsibility for losses.

1980s to emphasis on reform the existing system in the 1990s.. The reform process so far has gone through four phases (based on Liu & Gao 1999, Zhang 1999).

The first phase is from 1978-1983. This is an experimental phase of SOE reform as the national reform emphasized on the agricultural sector which took the household contract responsibility system as the fundamental. The experiment of SOE reform was initiated in Sichuan province in October 1978. It involved a program of expanded enterprise autonomy which was introduced to six factories (SOEs). That is, after fulfilling state plans, these SOEs would have certain decision flexibility in production plans, product marketing, worker employment and technological innovation. They would also share the profits according to specified plan and above-plan profit retention rates. The number of SOEs in this experiment had increased to 100 in this province by the beginning of 1979. From 1980, the provincial government started to adopt a unified profit retention rate and at the same time, a change from profit remittances to taxes was experimented with some SOEs (Huang 1999). On the basis of Sichuan experiences, in 1979 the central government began its own experiment (similar to that of Sichuan) with eight firms in Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai, and announced a new responsibility system for profits and losses. The core of which was to allow SOEs to retain a share of profits, enjoy accelerated depreciation and sell above-plan output. The number of SOEs adopting this responsibility system rose to 6,600 in June 1980 and about 42,000 in early 1981. By 1983, almost all the SOEs had adopted this responsibility system (Huang 1999). To sum up, the core component of the SOE reform was to grant more autonomy and allow profit-sharing between enterprise and government. At this phase, the experimental SOE were allowed to retain 3% of their profits. This was a breakthrough of pre-reform relationship between state enterprises and government.

The second phase is from 1983 to 1987. The main focus of reform was on the adjustment and regulation of rights, responsibilities and benefits between enterprises and government. The major measures included two steps of ‘tax for profit’ and ‘the repayable loan for free grant’.

In distribution system, the profit and tax that the enterprise should submit to the state were combined into one item, the enterprise submitted a certain percentage of the sum to the state and retain the rest. In 1983, only 50% of the enterprise profit was combined with taxes, the other 50% of profits had to be completely submitted as state fiscal income. In 1984, this was changed to a combination of 100% of enterprise profits and taxes. The main purpose of which was to replace the previous co-existence of tax and profit remittance with a simple tax system and the SOEs could therefore pay taxes by following state regulations. Then ‘four taxes and two fees’ were

financed from budgetary grants, a 50% income tax, taxes on real estate, vehicle tax and adjustment tax’ (Huang 1999). On the basis of the tax for profits, in order to reduce the pressure on state fiscal investment in SOEs while strengthening control over the SOEs, the investment in enterprise fixed assets was changed from state fiscal grants into loans from the state bank. At the end of 1984, it was decided that all state investment would be on a repayable basis rather than free grant, allocated through the state banking system.

However, at the time when the central plan still controlled a dominant proportion of SOEs’ activities, the SOEs could hardly exercise autonomy. State intervention often took place as the conflicts often appeared in the objectives of the state plan and the SOEs. The reform of ‘bank loans for budgetary grants’ did not succeed because state banks could not effectively force unprofitable SOEs to repay the loans. ‘tax for profit’ on its own was not able to help realize enterprises’

self-operating, responsibility for profits and losses, and fair competition. This situation begged further reform of the SOEs.

The third phase is from 1987 to 1992. When no other alternative measures were found effective in reforming SOEs, Contract Responsibility System (CRS) which had been proved useful and successful in the agricultural sector was seen to be more acceptable at that time, partly because it could maintain state ownership. Furthermore, the CRS emphasized on responsibilities of SOEs while retaining the rights and

incentives of the enterprises. It was relatively stable since contracts were often signed for 3-5 years as one term, more often, a contract could be extended to a second term or more. So it was widely introduced into the state sector although shareholding holding system was allowed to be experimented with a limited number of SOEs. By mid 1987 the implementation of CRS had reached a climax. By the end of 1987, 78% of SOEs had implemented CRS (Wu 1999). The aim of adopting CRS was to separate property rights and operating rights. The contract subject was profits and taxes that the enterprise submitted to the state. From late 1987, most of the SOEs started to adopt the CRS. By 1992, nearly all large and medium-sized SOEs had adopted the CRS. Parker & Pan (1996) indicate that CRS covered 95% of SOEs by 1992. Thereafter CRS remained at the core of the SOE reforms until its weaknesses increasingly appeared and even hampered further reform of the SOEs in the early 1990s.

components- (i) a profit-sharing scheme, (ii) projects for upgrading the company’s technology and management, and (iii) a scheme for determining wages and bonuses that were contingent upon the company’s performance (Pyle, 1997: 96).

The implementation of CRS was to clarify the authorities and responsibilities of enterprises and their supervisory bureaux. It was aimed to reduce government

intervention in the operation of SOEs, and to make the enterprise financially

independent and focus on profit rather than on plan fulfillment (Fan 1994). However, CRS was not as successful as expected in comparison with that used in the

agricultural sector. Its by-products were seen in short-termism of SOE performance, which led to disorder in the economy and rising prices. It fell below the expectation of separating government and enterprises, also hampered the restructuring of the

economy and consolidated the existing system.

At this phase, two important laws in relation to SOE reform were approved. One was the Bankruptcy Law and the other was Enterprise Law. For the first three phases, the common feature of the reforms was that state-ownership remained unchanged. Reforms were based on the theory on separation of property rights and operating rights of enterprise, concentrating on the readjustment of income redistribution relationship between enterprises and government.

The fourth phase is from 1992 to present. This was marked by the milestones of Deng Xiao-ping’s (the ex-reform architect) ‘southern inspection speech’ and the 14th CPC (the Communist party of China) National Congress in 1992. Since 1992 the establishment of social market economy has been legitimized as the reform target. This signaled a breakthrough of political ideology which heavily impact the reform. The core component of the reform at this phase is the establishment of modern enterprise system. Autonomy and monitoring were two key elements of the reform. Monitoring became a new focus of the SOE reform because it was recognized the enterprises would hardly fulfill their full responsibilities if there were no effective monitoring (Zhang, 1999). The SOE reform has started to move away from the

adjustment of distribution relationship and authority reallocation between government and enterprise towards the system of property rights (ownership). The main form of this movement is shareholding system. For SOEs being turned into shareholding companies, it is not solely the state that exercises the rights for enterprise assets, but all shareholders (including individuals, other state or non-state entities). The main advantages of shareholding system are seen as below (IMF 1993): (1) separating government ownership from enterprise management; (2) mobilizing and rationalizing the allocation of financial resource; (3) providing greater financial and

Based on the theory that public ownership economy can be put into full play in a mixed ownership economy, reforms in the period from 1992 to 1997 emphasized experiment of establishing modern enterprise system (MES), and those for the period starting from 1997 involve radical ownership diversification on large scale. Especially, shareholding and share-cooperative system have been largely promoted through

reorganization of state assets although shareholding arrangements were on an experimental basis from the mid-1980s. By the end of 1996, 4300 SOEs had been converted into joint stock companies (FEER September 25, 1997: 15).

MES was officially defined to include four important aspects: (1) clearly

defined property rights, (2) clear-cut responsibility and authority, (3) separation of the function of government and enterprises and (4) scientific management. According to the system, the state is prohibited from direct intervention with enterprise

management. State enterprises, in turn, become legally responsible for

self-management, profits and losses, taxes-payment, assets maintenance and so on. As a result, in 1998, a new breakthrough was achieved in the separation of government administration from enterprise operation—State council component departments were cut from 40 to 29. Thus many industrial bureaux have been abolished, which

correspondingly reduce their intervention with commercial and entrepreneurial activities over enterprises. There appeared a trend that industrial ministries and bureaus developed into hybrid organisations. In relation to enterprises, some of these organizations performed functions of coordination and supervision similar to that of head offices of multi-divisional firms or conglomerates. They also performed regulatory functions covering all enterprises in the industry regardless of their ownership status. For example, many of the industrial bureaus have now been

transformed into holding companies covering enterprises they previously supervised. In recent years, reforms have been taken to reorganize state assets. The main policy approved in 1997 by CPC 15th Congress is ‘emphasizing the big and

liberalizing the small (some interpreted it as ‘holding the large SOEs and let the small go’’. In essence, this policy attempts to maintain about 1000 large SOEs through introduction of ‘modern enterprise system, which is dominated by the share-holding system. At the same time, the policy attempts to enliven the small- and medium-sized SOEs through sale, merger and bankruptcy, etc. Most large SOEs are transforming into shareholding companies and small SOEs are allowed to go wherever they wish and they can, including going into the private sector. In other words, ownership diversity is the main approach to small enterprise reform.

the government into a select number of large enterprises (in November 1997, six firms selected1). Second, to develop a modern enterprise system in large SOEs by the year 2010. ‘As part of the Ninth Five year Plan (1996-2000), the central government has selected 1000 SOEs to form the ‘Core’ of the ‘modern enterprise system’ (Smyth 2000). Third, to develop a number of enterprise groups in strategic sectors. A wave of conglomeration and enterprise mergers is thus sweeping across industries. ‘National corporations’ are the immediate result, because these corporations are expected to be the driving forces in the modernization of industry. 512 large enterprises of national and subnational levels were first targeted. ‘In 1997 alone, 3000 enterprises were merged and 15.5 billion yuan sate assets was reallocated (Smyth 2000: 723). Moreover a multitiered organizational network of state asset management bureaus,

state assets operating companies and sate asset supervisory committees emerge. In all, since the 1990s shareholding system dominant reform of SOE

transformation. The following three major forms of the SOE transformation have been employed.

1. Transforming to modern enterprise system

2. Developing into large group enterprises (hold the large SOEs)

3. Reorganization of small enterprises (sale to the non-state enterprises) (enlivening the small SOEs)

5. Public Enterprise Reform in China

China’s public enterprises (referred to as state-owned enterprises (SOEs)) used to reflect the former Soviet-model of industry since China followed a Soviet-type of socialism at its establishment in the 1950s. By the end of the 1950s, private firms had been largely eliminated in favour of SOEs and collective firms. In other words, the SOEs were owned, run and funded by the government and were not responsible for either profits or losses. This section explores China’s SOEs as a whole. First it examines the SOEs’ size and structure, then a section is devoted to economic and social roles of the SOEs, a third section looks at the SOE reforms phase by phase, and the fourth section is reviews SOEs performance. In the final section, the impact of SOE reform is examined in relation to labour.

Because the data is generated for different statistical purposes, different terms may be used to describe the SOEs. The data may be only able to describe a partial

1

picture of the SOEs under the terms of industrial SOEs, SOEs with independent accounting systems. China had 305,000 state-owned enterprises by the end of 1995 (excluding 24,000 financial enterprises), 87,900 of them independent accounting industrial SOEs. Of the 87,900 state-owned independent accounting industrial

enterprises which accounted for 62 per cent of the total assets of industrial enterprises, there were 15,700 large and medium-sized industrial SOEs and 72,200 small ones by the standard of SSB (1995) (Gao and Yang 1999; Liu & Gao 1999; Wu 1999). By the end of 1995, the total assets of the 305,000 SOEs had been only 7472.1 billion yuan (equivalent to over 900 billion US$), of which non-production assets (for employee houses, schools and hospitals) accounted for 20 per cent. This indicates that state assets were very much scattered among state enterprises. The total debts were 5,176.2 billion Yuan (equivalent to over 600 billion US$), the average ratio of debts to assets was 69.27 per cent (Liu & Gao 1999: 67).

Of all the SOEs, 95 per cent of them are small or medium-sized units. Large SOEs only account for 5 per cent. Of all industrial enterprises, large enterprises accounts for 5 per cent, medium-sized enterprises 13 per cent and small enterprises 82 per cent (Liu and Gao 1999). OECF indicates that most of the state industrial

enterprises are in mining and manufacturing industries. ‘According to SSB (1996), the number of mining and manufacturing state-owned enterprises was 69,500, of which the number of medium to large sized SOE was 14,800 (OECF 1998: 25)’.

The total assets of all industrial enterprises were 4,952.5 billion yuan (about 6oo billion US$), among which the assets of state industrial enterprises are 3,261.2 billion yuan (equivalent to about 400 billion US$). Nevertheless, the total number of

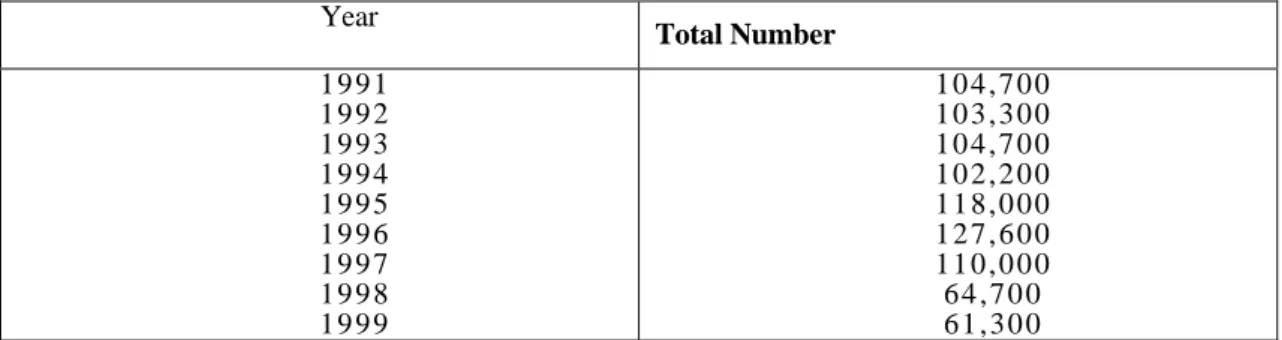

state-owned industrial enterprises has continually decreased through the reform process in the last decade, as Table 5.1 indicates. Between 1991 and 1999, the number of industrial SOEs had decreased by 40 per cent or so from 104,700 in 1991 to 61,300 in 1999.

Table 5.1 The total number of industrial SOEs (1991-1999) Year Total Number 1 9 9 1 1 9 9 2 1 9 9 3 1 9 9 4 1 9 9 5 1 9 9 6 1 9 9 7 1 9 9 8 1 9 9 9 1 0 4 , 7 0 0 1 0 3 , 3 0 0 1 0 4 , 7 0 0 1 0 2 , 2 0 0 1 1 8 , 0 0 0 1 2 7 , 6 0 0 1 1 0 , 0 0 0 6 4 , 7 0 0 6 1 , 3 0 0 Source: SSB (1996: 401; 2000: 407)

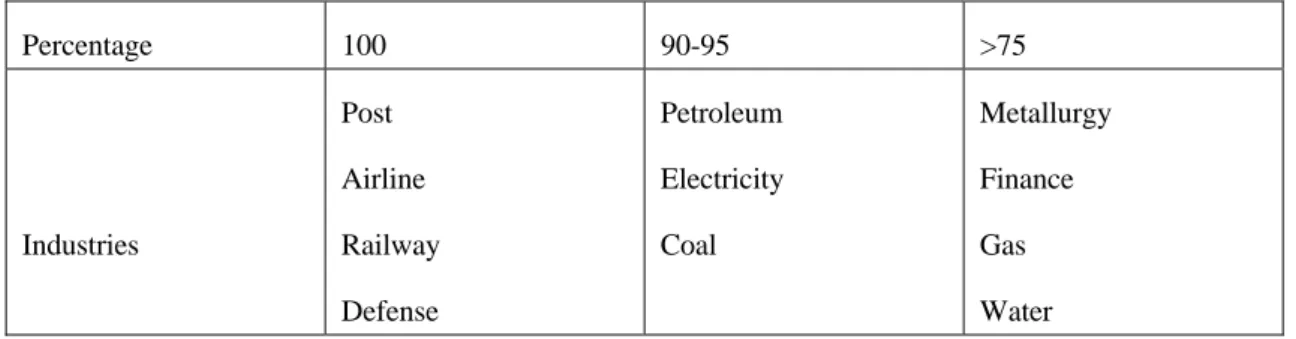

According to SSB (1995), industries of which assets are 100 per cent of the state include post, airline and railway. Industries with 90 per cent or above of state assets includes petroleum (95 per cent), electricity (91 per cent), coal (90 per cent).

Industries with over 75 per cent state assets include metallurgy, finance, gas, water industries, as Table 5.2 shows (Liu and Gao 1999: 101).

Table 5.2 Percentage of state ownership in industries (Unit: %)

Percentage 100 90-95 >75 Industries Post Airline Railway Defense Petroleum Electricity Coal Metallurgy Finance Gas Water Source: SSB (1995)

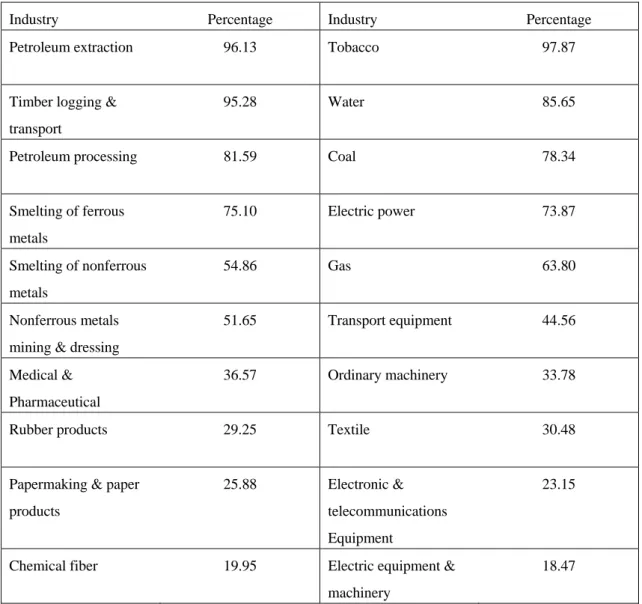

The large SOEs cover the industries of railway, post, airline, steel and iron, automobile, petroleum and financial fields. Their shares of taxes submitted to the state account for 85 per cent of the total taxes by all SOEs (Liu & Gao 1999). In terms of added value, the state-owned proportion in 32 out of 39 industries had accounted for more than 50 per cent by 1992. However, by 1997, this percentage had largely declined. Except that the state-owned proportion was still dominant (accounting for over 50 per cent) in 11 monopolistic and basic industries, and the value added by the state-owned part in the rest of the industries had gone down below 50 per cent. Table 5.3 shows the decline of value added by the state-owned part in the main industries in 1997. This also indicates the decline of state ownership in these industries due to market-oriented reform. By 1999 the share of state ownership had further declined.

Table 5.3 State-owned proportion of value-added in industries in 1997 (Unit: %)

Industry Percentage Industry Percentage Petroleum extraction 96.13 Tobacco 97.87

Timber logging & transport

95.28 Water 85.65

Petroleum processing 81.59 Coal 78.34

Smelting of ferrous metals 75.10 Electric power 73.87 Smelting of nonferrous metals 54.86 Gas 63.80 Nonferrous metals mining & dressing

51.65 Transport equipment 44.56

Medical & Pharmaceutical

36.57 Ordinary machinery 33.78

Rubber products 29.25 Textile 30.48

Papermaking & paper products

25.88 Electronic & telecommunications Equipment

23.15

Chemical fiber 19.95 Electric equipment & machinery

18.47

Source: Gao and Yang (1999: 249-250 adapted from SSB 1993-1998)

In 1996, the total number of large industrial enterprises was 7,057, of which SOEs accounted for 70.09 per cent. The output value of the SOEs was 69.89 per cent, assets accounting for 75.98 per cent and 85.45 per cent of employment of the 7,057 industrial enterprises. Until the late 1990s, the investment rate in the state-owned economy was high, accounting for over 50 per cent of the total investment. And the state-owned enterprises covered a wide range of industries and sectors.

goal of achieving significant economies of scale. The lack of economies of scale more obviously appeared in the automotive, machinery and steel industries.

Nevertheless, the SOEs have continued to be a key part and the bedrock of the economy in terms of their shares of employment and fixed assets. The government intends to convert all large and medium SOEs into share-holding corporations and to enliven small SOEs through acquisitions, mergers, leasing and sales. The small SOEs are allowed to go to private sector in a variety of forms. The immediate visible change in industrial structure so far has been the diversification of forms of ownership. The corporatisation and ‘letting go’ are currently under way, there is a likely prospect for the future – a sharp reduction in the number of SOEs and COEs.

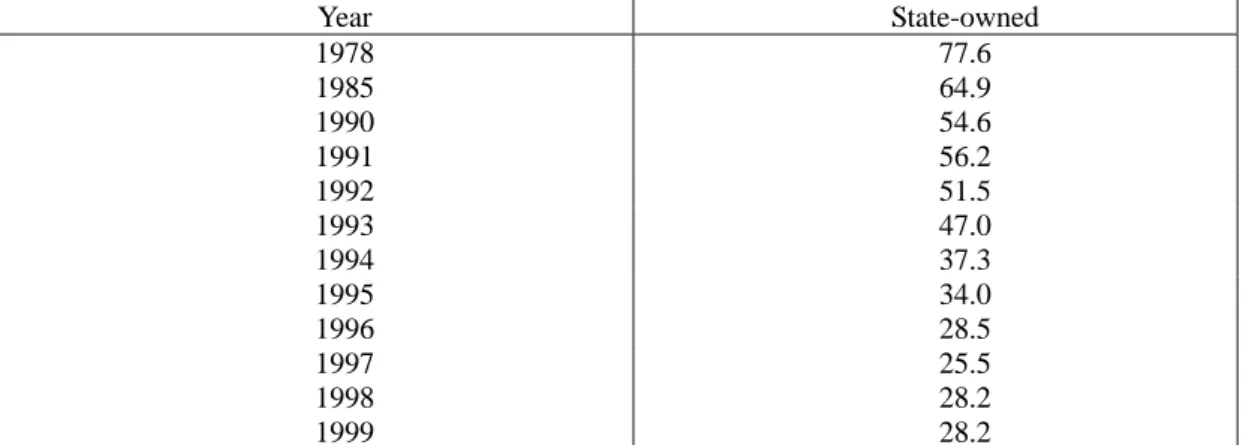

5. 1 SOEs are important

The importance of the SOEs lies in their dominant status in the economy in terms of government fiscal revenue, employment and key social service role. The SOEs as a whole have dominated industrial production and China’s economy for over half a century. Even today, the industrial SOEs account for one third of national production, more than half of total assets, and over half of total investment (their share of total investment rose from 61 per cent to 70 per cent between 1989 and 1994, but decline thereafter). In terms of SOEs’ contributions, the SOEs, as a whole, absorb over half (over two-thirds in the 1980s) of urban employment and provide about 70 per cent government fiscal income. Although the share of SOEs in the gross industrial output value was declining through the reform process, they still accounted for more than a quarter by 1999, as Table 5.4 indicates.

Table 5.4 Share of state ownership of industries in gross industrial output value (1978-1999) (Unit: %)

Year State-owned 1978 77.6 1985 64.9 1990 1991 54.6 56.2 1992 51.5 1993 1994 47.0 37.3 1995 1996 34.0 28.5 1997 1998 1999 25.5 28.2 28.2

5. 2. Role in employment

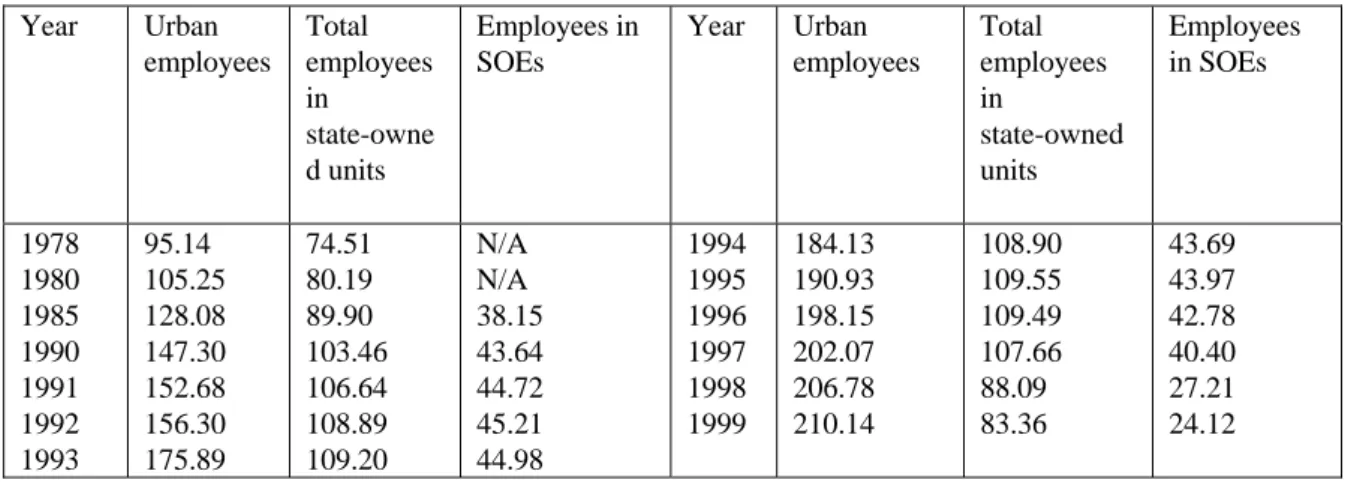

With regard to employment, between 1978 and 1991, the number of workers in the state-owned sector increased by 33 per cent to around 107 million (Parker & Pan 1996). Until 1997, this number remained and only decreased to 88 million in 1998 and 83 million in 1999. Of all the workers in the state-owned sector, the SOEs absorbed 40 million or so until 1997. Such a figure of employment in the SOEs only reduced to 27 million in 1998 and 24 million in 1999 (SSB 1998, 2000). The share of industrial employment of the SOEs is even higher than their share of fixed capital (65 per cent) until the late 1990s. The percentage of the urban working population employed in the state-owned sector was about 63 per cent in 1992 and down to 55 per cent in 1996 (OECF 1998: 31) due to employment adjustment in the SOE sector. ‘It is estimated that there are 15 to 37 million surplus workers in the SOEs’ (IIECASS 2000: 367). By 2000 more than 20 million workers have been laid off from the SOE sector since the mid-1990s, of which more than 10 million have had difficulties in finding new jobs.

Although the registered urban unemployment rate was only around 3 – 4 per cent, but adding the hidden unemployment (surplus workers and layoffs in the SOEs), this figure goes up to double digits. As Liu and Gao (1999) document, the actual urban unemployment rate was 18.9 per cent by the end of 1997. And this rate was estimated to be 15.6 per cent in 1998. Serious unemployment has therefore brought in enormous threats to social stability, which intensifies the dilemma of SOE reform, and also constitutes a reason why the essential reform of SOEs has been delayed again and again.

Table 5.5 Employment contribution of the state-owned sector (1978-1999) (unit: million) Year Urban employees Total employees in state-owne d units Employees in SOEs Year Urban employees Total employees in state-owned units Employees in SOEs 1978 1980 1985 1990 1991 1992 1993 95.14 105.25 128.08 147.30 152.68 156.30 175.89 74.51 80.19 89.90 103.46 106.64 108.89 109.20 N/A N/A 38.15 43.64 44.72 45.21 44.98 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 184.13 190.93 198.15 202.07 206.78 210.14 108.90 109.55 109.49 107.66 88.09 83.36 43.69 43.97 42.78 40.40 27.21 24.12 Source: SSB (1994: 84 &374; 1996:87; 1998: 127& 432; 2000: 408)

5. 3 Specific reform measures of SOEs

As mentioned earlier, prior to the reform which started in 1978, the SOEs were fully owned, funded and run by the government. The enterprise did not have any decision-making power over production, investment or distribution. All their profits had to be submitted to the government while taking no responsibility for losses.

The reform of SOEs has been aimed to release state enterprises from central planning administration, and adapt them to the market economy. In order to enhance efficiency and competitive capacity, a number of measures have been taken although there is no coherent blueprint for the measures. The approach to SOE reform, as a whole, is trial-and-error, from incremental reform ‘out of the system reform’ in the 1980s to an emphasis on reforming the existing system in the 1990s. The reform process so far has gone through a few phases outlined below (IMF 1993; Liu & Gao 1999; Zhang 1999).

5. 3. 1 The first phase 1978 to 1982-Experimental years with the

responsibility system

This was an experimental phase of SOE reform as the national reform

breakthrough from pre-reform relationship between state enterprises and government.

5. 3. 2 The second phase 1983 to 1986-Tax for profit and the CRS

The main focus of reform was on the adjustment and regulation of rights, responsibilities and benefits between enterprises and government. The major measures included two steps of ‘tax for profit’ with took place in 1983 and 1986 respectively, ‘the repayable loan for free grant’ and the nation wide implementation of the contracting responsibility system (CRS).

In the reform of the distribution system, the profit and tax that the enterprise should submit to the state were combined into one item, and the enterprise submitted a certain percentage of the sum to the state and retained the remainder. In 1983, only 50 per cent of the enterprise profits were combined with taxes, the other 50 per cent of profits had to be completely submitted as state fiscal income. In 1984, this was

changed to a combination of 100 per cent of enterprise profits and taxes. The main purpose of this was to replace the previous co-existence of tax and profit remittance with a simple tax system, and the SOEs could therefore pay taxes by following state regulations. Then ‘four taxes and two fees’ were levied on the SOEs. They included ‘annual fees for fixed assets and working capital financed from budgetary grants, a 50 per cent income tax, taxes on real estate, vehicle tax and adjustment tax’ (Huang 1999). However, the reform of ‘tax for profits’ fell short of expectation (Wu 1999).

In order to reduce the pressure on state fiscal investment in SOEs while strengthening control over the SOEs, investment in enterprise fixed assets was changed from state fiscal grants into loans from the state bank. At the end of 1984, it was decided that all state investment would be on a repayable basis rather than a free grant, allocated through the state banking system.

However, at the time when the central plan still controlled a dominant proportion of SOEs’ activities, the SOEs could hardly exercise autonomy. State intervention often took place as the conflicts often appeared in the objectives of the state plan and the SOEs. The reform of ‘bank loans for budgetary grants’ did not succeed because state banks could not effectively force unprofitable SOEs to repay the loans.

5. 3. 3 The third phase 1987 to 1992-Full implementation and

phasing out of the CRS

When no other alternative measures were found effective in reforming SOEs, the CRS which had been proved useful and successful in the agricultural sector was seen to be more acceptable at that time, partly because it could maintain state ownership. Furthermore, the CRS emphasized the responsibilities of SOEs while retaining the rights and incentives of the enterprises. It was relatively stable since contracts were often signed for 3-5 years; more often, a contract could be extended to a second term or more. So it was widely introduced into the state sector although the shareholding system was allowed on an experimental basis in a limited number of SOEs. By mid 1987 the implementation of CRS had reached a climax. By the end of 1987, 78 per cent of SOEs had implemented CRS (Wu 1999). The aim of the

adoption of the CRS was to separate property rights and control rights. The contract concerned profits and taxes that the enterprise submitted to the state. From late 1987, most of the SOEs started to adopt the CRS. By 1992, nearly all large and

medium-sized SOEs had adopted the CRS. Parker & Pan (1996) indicate that CRS covered 95 per cent of SOEs by 1992. Thereafter CRS remained at the core of the SOE reforms until its weaknesses increasingly appeared and began to hamper further reform by the early 1990s.

The most widely used form of CRS was Contract Management Responsibility System (CMRS). This system consists of three main elements: (i) the Contracted Management System (CMS), (ii) the Manager Responsibility System (MRS) and (iii) the Internal Contract System(ICS) (Pyle,1997:97). Among them the CMS was a formal contract between the CSE and the state which also had three main

components- (i) a profit-sharing scheme, (ii) projects for upgrading the company’s technology and management, and (iii) a scheme for determining wages and bonuses that were contingent upon the company’s performance (Pyle, 1997: 96).

The implementation of CRS was to clarify the authorities and responsibilities of enterprises and their supervisory bureaux. It was aimed at reducing government intervention in the operation of SOEs, and to make the enterprise financially

independent and focus on profit rather than on plan fulfillment (Fan 1994). However, the CRS was not as successful as expected in comparison with that used in the agricultural sector. Its by-products were seen in short-termism of SOE performance, which led to disorder in the economy and rising prices. It also fell below the

In summary, the first three phases constituted the first stage of transition of the SOEs. The common feature of this stage was that state-ownership remained

unchanged. Reforms were based on the theory of the separation of property rights and operating rights of enterprise, focusing on the readjustment of the income

redistribution relationship between enterprises and government. More efforts are seen directed to foster external competition to the SOEs and the development of the

competitive market. During this transition stage, the contracting system was at the heart of reform measures. Why did the contracting system have to be phased out and replaced by new measures (mainly the modern enterprise system (MES)) by the early 1990s? To answer this, it is necessary to look at the key features and weakness of the contracting system.

5. 3. 4 The fourth phase 1993 to 1997-The initial implementation of

MES and ownership divest

This was marked by the legalization of establishing the socialist market economy at the 14th CPC (Communist Party of China) National Congress in 1992 and the ‘Decision on Issues Concerning the Establishment of A Socialist Market Economy’ adopted by the Third Plenum of the Fourteenth Party Congress in November 1993. The legalization of a market economy signaled a breakthrough of political ideology which heavily impacted on the reform. The core component of the reform at this phase was the establishment of a modern enterprise system. Autonomy and monitoring were two key elements of the reform. Monitoring became a new focus of the SOE reform because it was recognized that the enterprises would hardly fulfill their full responsibilities if there was no effective monitoring (Zhang 1999). The SOE reform has started to move away from the adjustment of distributional relationships and authority reallocation between government and enterprise towards the system of property rights (ownership). The principal framework for the reform of large and medium-sized SOEs was the establishment of Modern Enterprise System (MES).

The MES was put into a nationwide experiment at the end of 1994. The MES was officially defined to include four important aspects: (1) clearly defined property rights, (2) clear-cut responsibility and authority, (3) separation of the function of government and enterprises and (4) scientific management. The core of the MES was a company system. According to the system, the state was prohibited from direct intervention with enterprise management. State enterprises, in turn, become legally responsible for self-management, profits and losses, taxes-payment, assets

and other state or non-state entities). The main advantages of the shareholding system are seen as below (IMF 1993): (1) separating government ownership from enterprise management; (2) mobilizing and rationalizing the allocation of financial resource; (3) providing greater financial and decision-making autonomy to enterprises so that they can become more efficient and respond dynamically to changing market conditions. By the end of 1996, 4,300 SOEs had been converted into joint stock companies (FEER September 25, 1997: 15). ‘In 1997 alone, 3,000 enterprises were merged and 15.5 billion yuan state assets were reallocated (Smyth 2000: 723). By the end of 1997, 2,329 large and medium-sized industrial SOEs had established the MES, which included 151.26 million workers / staff and total assets of 3,932.9 billion yuan. Of 1,813 enterprises in the MES experiment, 538 were transferred into shareholding limited companies, accounting for 29.7%; 702 were turned into limited liability companies, accounting for 38.7%; 573 were formed as companies with the state as the only shareholder. According to the state statistical report, of the 2,562 enterprise in the MES experiment, 1943 completed MES transformation, accounting for 35.8 per cent. Of these, 612 enterprise were transformed into shareholding limited companies, accounting for 31.5 per cent; 768 were transformed into limited liability companies, accounting for 39.5 per cent, and 563 were companies with the state as the sole shareholder, accounting for 29 per cent (ERDSETC 1999: 26).

5. 3. 5 The current phase 1998 to present- Three-year programme

and deep ownership divest

Based on the notion that public ownership economy can be put into full play in a mixed ownership economy, and the rapid increase of loss-making SOEs, reform measures moved to fundamental and strategic restructuring. These included wider and deeper ownership diversification of the SOEs through the policy ‘holding the large SOEs and letting go the small’, the ‘Three year programme of lifting the large

loss-making SOEs out of difficulty’, and the continued emphasis on the establishment of a modern enterprise system (MES). Especially, the shareholding and

share-cooperative system has been largely promoted through the reorganization of state assets and industrial restructuring2.

Since the mid-1990s, the SOE sector had experienced deteriorating performance and run into losses. According to the statistics of China’s Financial Ministry, in 1998 the SOE sector for the first time made a net loss of 7.8 billion yuan. By June 1998, 49.59 per cent of the 59,000 state-owned industrial enterprise had made losses, and 55.12 per cent of the 14, 000 large and medium-sized industrial SOEs made losses

2

(Gao and Yang 1999: 237).

5. 3. 5. 1 The Three-year Programme

In order to reverse the loss-making trend of SOEs, a series of measures has been carried out which included ‘the three-year programme’ of lifting loss-making SOEs out of trouble. This scheme was proposed by central government in 1998 which intended to reverse at least 3,000 SOEs from loss-making into profit-making, at the same time, to build up about 1,000 large group SOEs within three years (Liu and Gao 1999). The measures included a strong state input, including regulation, guidance and the strategic reorganisation of assets. By September of 2000, 54.9 per cent of the above cited key SOEs had managed to make profits (China Daily Sept.30 2000)3. According to the statistics of China’s Financial Ministry, in 1999 and 2000 the SOEs as a whole made profits of 114.58 billion yuan and 283.38 billion yuan respectively. According to the latest State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) statistics, by early 2001, ‘at least 65 per cent of China's 6,599 large and medium-sized SOEs have reversed their money-losing trends (China Daily Mar. 6, 2001)2

5. 3. 5. 2 Holding the big and letting go the small

The measure of ‘holding the big SOEs and letting go the small’ was officially proposed in 1997 and put into national formal action since 1998. This measure was implemented in line with industrial restructuring and state asset reorganisation. Only about 1000 large SOEs, which hold 70 per cent of SOE fixed assets and generate 80 per cent of profits and taxes, were planned to retain government control and benefit from the high level of state protection.

In essence, the reform of grasping the big SOEs attempted to maintain about 1,000 large SOEs through the introduction of the modern enterprise system, which is dominated by the share-holding system. The rest of the small- and medium-sized SOEs were encouraged to privatize through sales, mergers, bankruptcies, leasing, and so on. Most large SOEs are transformed into shareholding companies and small SOEs are allowed to go to the private sector in a wide range of forms. Those which have lost the market demand for their products or services, or simply made net losses, are ordered to close, file for bankruptcy or merge as appropriate. In other words,

ownership diversity is the main approach to small enterprise.

The reform of SOEs stays at the heart of, and remains the most difficult task of China’s economic reform. It has gone through a complicated and uneven process on a trial-and–error basis. An enterprise responsibility system was adopted, mainly through

3

Source: State firms smash set targets, Sept. 30 2000. (http://search.chinadaily.com.cn/isearch/

2

the implementation of a contracting system and responsibility system in the 1980s and the establishment of modern enterprise system in the 1990s. Currently the SOE sector is characterized with four key features. First, SOEs are prevalent in almost every industry, competitive or natural monopoly, and exist in all sizes, from very small to huge. Second, deeply politically-influenced management, a lack of market-supporting external environment (e.g. executives and managers appointed by the Party). Third, SOEs play a vital social role in terms of employee welfare and urban employment provision. The shedding of surplus workers causes serious challenges to social stability, Fourth, SOEs face a dilemma of retaining surplus workers and improving efficiency in the absence of a developed social safety net. The imperfection of the social security net challenges significant layoffs other than those over which the SOEs do not have much choices.

In the process of transformation, the SOEs were confronted with various

difficulties, from deteriorating profitability to increasing debts, which demand further reform of ownership and governance. The reforms in the 1990s turned to the

establishment of the modern enterprise system with an aim to overcome the problems under the factory system. The government took various steps to convert a great majority of large and medium-sized SOEs into corporations, which are expected to adapt to market conditions with clarified property rights and strong internal

management. It is perceived that the Shareholding Cooperative System (SCS) can be the most effective way to deepen the current reform of SOEs. In recent years, the implementation of the SCS has spread rapidly, particularly in medium-sized and small enterprises. However, problems also emerged in the process of corporatization of the SOEs. One of the most crucial problems was the absence of the subject of

state-owned property. The current reform of SOEs aims to clarify the property rights, optimize enterprise governance structures and promote the management of human resources. Although competition has been continually fostered since the beginning of the reform, such as the encouraged growth of TVEs and COEs and the dynamic introduction of international competition, this essentially relates to competition from outside the SOEs. But outside competition is not very much in SOE markets and therefore SOE need to be exposed to competition.

It is expected that the government will accelerate the transformation of the ownership system despite bankruptcies and unemployment, and that the new wave of SOEs featured as a shareholding cooperative system, the privatization of small and medium-sized SOEs, the further creation of competition and management reform will be extended in the foreseeable future.

The reform has generated far-reaching impacts on labour in terms of

from the SOEs since the mid-1990s as the SOE sector shrinks during the reform process. On the other hand, there is still a lack of a social safety net for unemployed workers. Under this circumstance, the state enterprises have to take care of most of the employee welfare. Before the establishment of a sound social security system is accomplished, the SOEs have to continue to play a major role of employee welfare as a cushion during transition.

6. Management Issues Facing the SOEs

Reform of the SOE sector has long been seen as one of the most important challenges since the reform began. Two most crucial reforms of the SOEs lie in the incentive system and property right system. The former has long been the centre of SOE reform, but the latter has now started to draw much attention of economists and reformers.

A key to the reform of incentive system is to give enterprise a main role in the market economy. Unless enterprises attain full autonomy, the necessary incentive and sufficient capability for competition will remain elusive. In order for enterprises to attain full autonomy, the adjustment of autonomy in terms of personnel and investment rights is indispensable. In essence, reforms are taken to improve the management of SOEs. The following is an analysis of the management situation of SOEs under different system through out the reform process.

6.1 Basic situation of management systems of SOEs

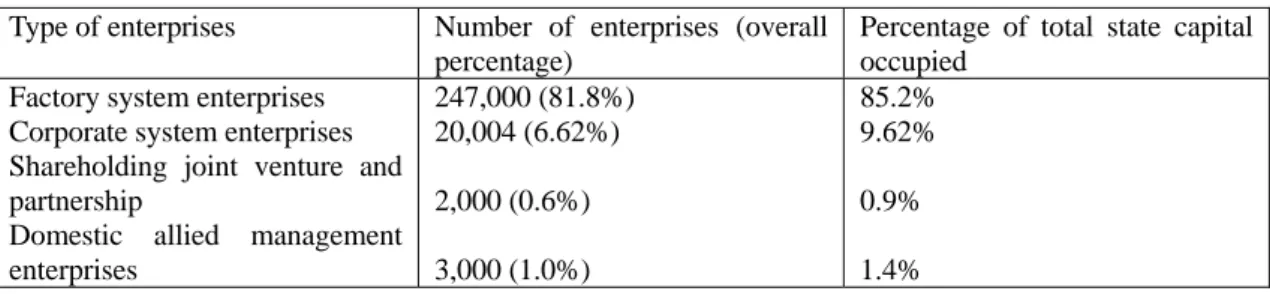

Since the beginning of the reform in 1978, two major systems of management have been employed for the mainstream of SOEs. These systems are factory system, corporate system (shareholding system as the main form). From factory system to shareholding system there has demonstrated an evolution trend.

The factory system includes manager responsibility system, contract system and leasing system. Enterprises under this system are managed based on the State-owned Enterprise Law (1988) and the Autonomous Management Right Regulations (1992). The state assets of these enterprises are managed based on the Regulations Governing the Supervision and Management of State-owned Enterprises’ Property (1994).

The corporate system consists of state-owned limited liability company, limited liability shareholding company and wholly state-owned company. Enterprises under such system are basically subject to the Company Law (1993). Since the mid-1990s, SOEs have increasingly shifted towards the shareholding system.

distribution of the management system of SOEs was as follows.

Table 6.1 Distribution of the system of management of the SOEs (unit: number of enterprises, %) Type of enterprises Number of enterprises (overall

percentage)

Percentage of total state capital occupied

Factory system enterprises Corporate system enterprises Shareholding joint venture and partnership

Domestic allied management enterprises 247,000 (81.8%) 20,004 (6.62%) 2,000 (0.6%) 3,000 (1.0%) 85.2% 9.62% 0.9% 1.4% Source: OECF (1998:120)

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, the most popular system of management was the factory system. Until now it is still the most widely-used system of

management although corporate system becomes increasingly popular and largely promoted from the mid-1990s and afterwards. But there is a trend that corporate system of management will eventually take over the factory system and be used as a dominant system of management for the enterprises. The result of OECF’s survey of 796 SOEs demonstrates that the enterprises under the corporate system have grown from 0.1% in 1991 to 5.7% in 1995. The increase of corporate management

enterprises is more rapid after 1995. The number of state-owned limited liability companies is increasing most rapidly. Problems and challenges appear in the factory management system as well as the transition from factory system to corporate system.

6. 1. 1 Key Feature of factory system SOEs

The important feature of factory system enterprises is the factory manager/director responsibility system, which is an extended version of the

contracting and leasing systems. As stated in the State-owned Enterprise Law (1988), under the factory system, ‘the factory manager exerts official power and receives legal protection’ and ‘the factory manager is the legal representative of the enterprise and takes full responsibility for the construction of the physical and mental

civilization of the enterprise.’ Under the Law, the factory manager is authorized to do the following (based on OECF 1998: 123):

1. Decide on the plans of the enterprise or apply for plan approval based on the relevant regulations of the State.

2. Decide on the establishment of the administrative organization of the enterprise. 3. Propose appointment and dismissal of managers at the deputy factory manager

level to the supervisory authorities of government. 4. Appoint or dismiss medium-level management.

bonuses, employee welfare, etc. And request discussion and decision at the employees’ congress.

6. Reward and punish employees based on the law, and propose rewards and punishments for deputy factory managers to the supervisory department.

In all, the factory manager is granted the right to occupy and use state properties whose management is entrusted by the state and to dispose of them accordingly. When it comes to the management autonomy of enterprises, the Enterprise Law provides the following 13 autonomies (OECF 1998: 123):

1. Independently determines the production of the products and services.

2. Has the right to request adjustment of directive plans when necessary supplies and sales of products are not secured, and has the right to accept and refuse production outside the directive plans.

3. Independently chooses suppliers and purchases input goods. 4. Independently determines the prices of products and service. 5. Independently markets the products of the enterprise concerned.

6. Negotiates with foreign enterprises, observing the provisions of the state council, concludes contracts, reserves and uses a prescribed percentage of foreign currency income.

7. Controls and uses reserved funds according to the provisions of the state council. 8. Leases or transfers fixed assets for consideration based on the provisions of the

state council. In this case, the manager is required to use the profits for the renovation of facilities or technological innovation.

9. Determines the form of wages and the distribution method of bonuses as according to the condition of the enterprise concerned.

10. Employs and dismisses workers in conformity with the laws and the provisions of the state council.

11. Determines the establishment and the number of staff of the organization. 12. Has the right to refuse any requisitioning of personnel, goods, funds, etc. By

another organization.

13. Has the right to have associated management with other enterprises or business units, investment in other enterprises or business units, and o hold the stock of other enterprises in conformity with the laws and the provisions of the state

council. Has the right to issue bonds based on the provision so f the state council.

which is the concrete form of the Enterprise Law. This law grants enterprises 14 autonomies as follows OECF (1998:124).

1. The right to decide on production;

2. The right to decide on the price of products and services; 3. The right to decide on independent sale of products; 4. The right to decide on the selection of suppliers; 5. The right to decide on foreign reserve funds; 6. The right to decide on investment;

7. The right to the use of reserve funds; 8. The right to decide on the disposal of assets;

9. The right to decide on joint operation and mergers with other units; 10. The right to decide on the hiring and firing of employees;

11. The right to decide on personnel management;

12. The right to decide on the distribution of wages and bonuses; 13. The right to decide on the organization of internal division; 14. The right to refuse requisition.

Among these autonomies, the rights to decide on the disposal of assets and to decide on personnel management are still difficult to operate. The core problem is the extent to which the State as an owner of the state-owned enterprises’ propertied should reserve control over personnel management and the disposal of assets. There is an on-going debate over this problem because there is ambiguity in the relationship between the management autonomy and the property ownership of the State. Thus, abuse of management autonomy by enterprises existed at the same time as the lack of management autonomy. In order to improve state property ownership, the Regulations Governing the Supervision and management of State-owned Enterprise’s Property was promulgated in 1994 (Supervision Regulation later) (OECF 1998). The

Supervision Regulations specifies the concept of the corporate property rights of the enterprises and provides that ‘enterprises have corporate property rights and

independently control properties where the management is entrusted to the State based on the law. The government and supervising organizations should not directly control the corporate property of the enterprises.’ However, the concept of ‘corporate property rights’ is confusing with its emergence in the Regulations. This leads to current top issue of property right.

on directive plan and the examination and approval of investments and allows that the State has the right to the partial use of the enterprises’ property. It also provides that the enterprises have the right to autonomous control over retained profits and allows the enterprises the right to partial receipt of income. Clearly there are defects in the definition of the management rights since the management rights is actually regarded as administrative management rights. There is not an accompanying change in the relations of property rights. Being specific forms of the Enterprise Law as well as two major regulations controlling the factory system enterprises, both the ‘Autonomous Management Right Regulations’ and the ‘Supervision Regulations’ do not solve all problems of SOE management while some new problems emerge in the process of their implementation. The autonomy is not granted easily or just a transfer of the administrative management right while the State’s property right does not have substance. This leads to absence of the real owner of state assets and problems of insider control due to poor monitoring. As the enterprise’s right is limited in the disposal of assets and personnel appointment, there still exists the bedrock for government intervention. The enterprise management neglects the increase in assets value and development of the enterprise. Instead enterprises more often than not put their focus on securing profit transfer and employees’ income (OECF 1998).

6. 1. 2 Major problems under the factory system:

There are three major problems of the factory system. The biggest one is the severe outflow of state assets; the second one is the poor management performance of state assets; the last one is non-economies of scale -too many too small enterprises and large enterprises are not large compared internationally.

The biggest problem resulting from the factory system is the critical condition of the outflow of state assets. OECF (1998) defines two kinds of outflow: the outflow in a narrow sense is the free conversion of state-owned assets to non-state-owned assets. The outflow in a broad sense includes, in addition to the narrow sense outflow, loss caused by inefficient management. ‘The amount of outflow is huge, its form is diversified and the number is increasing’.

The forms of state assets outflow include (based on OECF 1998: 133):

1. Contracting is only for profits and, enterprises or managers take no responsibility for loss. The state as the asset owner has to be responsible for losses. This problem especially occurs in the contracting and leasing management systems.

3. Unlisted income and assets are too extensive. There are many cases where the assets formed by a unit through funds offered from finance have not been included in the books, fixed assets which have already been used by the enterprise have not been included, or assets transferred to a collective ownership system enterprise have not been included.

4. Non-state owned enterprises (especially the collective ownership enterprises) occupy state-owned assets free of charge.

5. The abuse of autonomy and infringement upon the rights of the state owner are often committed by enterprises. Some enterprises invest in real estate, stock, and futures using public funds, taking the earnings if it makes a profit and passing them on to the State if it is a loss. Some enterprises make a window dressing settlement without including prescribed depreciation or deferred expenses, or give out too many bonuses.

Moreover, the poor management performance of the state assets is often demonstrated in profit declining and loss increasing, low rate of input production, increasing deficits and high ratio of debt to assets (FCLMA, 2007). In 1994, 11% of all the SOEs had liabilities which exceeded their assets (OECF 1998:133) and In 1995 this figure rose to 16.28% and the average ratio of debt to assets of all but financial SOEs was 69.27% (Liu & Gao 1999).

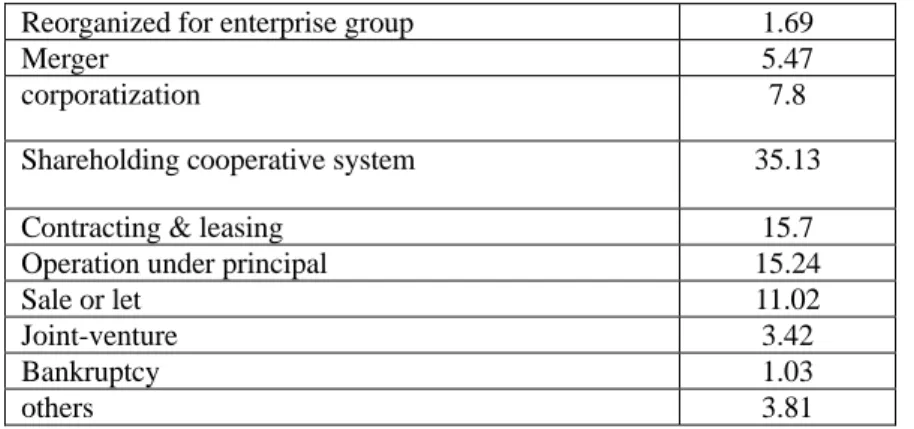

6. 2 Situation of Corporation system and its problems

Table 6.2 Situation of Small SOE transformation (by 1996 investigation) (%) Reorganized for enterprise group 1.69

Merger 5.47 corporatization 7.8 Shareholding cooperative system 35.13

Contracting & leasing 15.7 Operation under principal 15.24 Sale or let 11.02

Joint-venture 3.42 Bankruptcy 1.03 others 3.81

Source: Liu & Gao 1999: 268

Since the 1990s reorganization of property rights have come to the center of SOE reform and shareholding system has become the main form of the reform. By the end of 1997 there had been 745 listed enterprises and the gross market value

accounted for 23.4% of GDP. In March of 1998 the number of listed enterprises rose to 762. Shi and Zhou (1998) state that among 9200 shareholding limited companies, state shares account for 43% and legal person shares account for 25.1%. But at present these public shares ( consists of state and legal person shares) are not allowed to circulate in the stock market.

However problems have started to appear in the reform for the establishment of modern enterprise system. These problems mainly include:

Ideological chaos

Some thinks that shareholding system in the SOEs is equivalent to private system. This thought insists that the state shares’ entering the stock market will lead to the privatization of state assets. Privatization of state assets is not acceptable to socialist economy. It is also seen as leading to the forfeiture or outflow of state assets. Thus in order to protect state assets, there is classification of state shares, legal person shares, individual shares. The first two shares are named public shares which

Nonstandard operation of shareholding system

There is trend that same shares have different rights and different value. These differences mainly exist between state shares and individual shares. This is against the principle of fairness and can lead to the outflow of state assets.

Moreover some enterprises force each employee to buy a stipulated number of shares. Each shareholder equally shares the profits and losses. Should any employee refuse to buy the shares, they have to leave the enterprise. This causes a new type of ‘eating from the big-pot’ of equalitarian of distribution.

Personal appointment remains irrational. According to the situation of 762 listed enterprises in 1998, it is estimated that over 90% shareholding companies (formerly state-owned) have one person to be the chairman and general manager at the same time (Liu & Gao 1999).

Old wine in new bottle

Some enterprises only do some superficial work in the transformation for shareholding system. They just change their names into shareholding companies, set up boards of directors and monitoring committees whose chairmen and general managers are internally appointed without selection by the shareholders. As a result, the operating system of enterprise is the same. The establishment of shareholding system is just like old wine in new bottle.

In all, the transformation of SOEs towards shareholding system corporation is aimed to clarify property rights and strengthen enterprise governance structure and internal management. Up to now, the biggest problem of SOE reform is the absence of the management subject of state property ownership, that is, to clearly define the ownership representative of state assets of enterprises. Another critical challenge is the Party-involved personnel appointment system and the need for modern human resource management.

7. Conclusion

at the heart and remains the most difficult task of China’s economic reform. The reform of state-owned enterprises has gone through a complicated and uneven process on a trial-and –error basis. It once adopted factory system, mainly through implementation of contracting system and responsibility system in the 1980s.

However, the SOEs were confronted with various difficulties, from deteriorating profitability to increasing debts, which demand further reform of ownership and governance structure. Thus the reform turned to the establishment of modern

enterprise system with an aim to overcome the problems under the factory system and new difficulties. The government takes steps to convert a great majority of large and medium-sized SOEs into corporations, which will adapt to market conditions with clarified property rights and strong internal management. It is perceived the

shareholding cooperative system (SCS) can be the most effective way to deepen the current reform of SOEs. In recent years, the implementation of the SCS has spread rapidly, particularly in medium-sized and small enterprises. However, problems emerge in the process of corporatization of the SOEs. The most crucial problem is to the absence of the management subject of state property ownership. The future reform of SOEs are to clarify the property rights, optimize enterprise governance structure and promote the management of enterprise human resources.

In the end, the paper questions the conventional transition claims that

‘ownership matters most and ownership matters more than competition’. The study claims that competition is essential to the transition and without it the economic transition to a market economy cannot be achieved. But competition needs

well-designed market-supporting institutions and strong government support. Some lessons can be learnt as follows:

7. 1 Lessons from the Chinese case

The transition to a market economy does not succeed without well-designed and government-led development policies. More detailed lessons are addressed in the aspects of management reform and labour issues.

7. 1. 1 Lesson for the introduction of competition

Competition is essential to market transition and should be created in all sorts of ways. The following ways are effective and have been proved to be useful, at least in the Chinese case. First, the nonstate sector should always be encouraged to grow to create external competition to the SOEs. Second, opening up to the outside world and the involvement in the global economy, such as WTO access, would generate