國 立 交 通 大 學

管理科學系

博 士 論 文

No.051

探討網路購物價值與網路購物態度之關係:性

別差異性

Exploring the Relationship between Online Shopping

Values and Attitude toward Online Shopping: Gender

Differences

指導教授:黃仁宏 教授

研 究 生:楊易淳

探討網路購物價值與網路購物態度之關係:性

別差異性

Exploring the Relationship between Online Shopping

Values and Attitude toward Online Shopping: Gender

Differences

研 究 生:楊易淳 Student:Yi-Chun Yang

指導教授:黃仁宏 Advisor:Jen-Hung Huang

國 立 交 通 大 學

管理科學系

博 士 論 文

A DessertationSubmitted to Department of Management Science College of Management

National Chiao Tung University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in Management

July 2010

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

I

探討網路購物價值與網路購物態度之關係:性

別差異性

研究生:楊易淳

指導教授:黃仁宏

國立交通大學管理科學系博士班

摘

要

本研究從性別差異的角度探討網路購物價值與網路購物態度之間關連性。

本研究透過問卷調查方式,資料來源為296個大學生。研究結果發現功能性

價值(像是便利性、資訊取得及避免社交性)及享樂性價值(像是探險性及社

交性)對於網路購物態度皆有正向的影響。性別對與五種網路購物價值皆有

產生主效果影響。此外,性別對於五種網路購物價值與網路購物態度之間的

關連性有產生干擾效果,結果顯示便利性及避免社交性對於網路購物態度

的影響上男性是高於女性的;反之探險性、資訊取得及社交性對於網路購物

態度的影響上女性是高於男性的。最後本研究討論研究結果的意涵及提出

未來可供研究的方向。

關鍵字: 性別差異;網路購物價值;功能性價值;享樂性價值;網路購物態度

II

Exploring the Relationship between Online Shopping

Values and Attitude toward Online Shopping: Gender

Differences

Student:

Yi-Chun YangAdvisor(Advisors):Dr.

Jen-Hung HuangDepartment of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

This study examines the relationships between online shopping values and

attitude toward online shopping using gender as a moderator. Data were

collected from 296 undergraduate students using a questionnaire. The result

indicated that utilitarian values (i.e. convenience, availability of information and

lack of sociality) and hedonic values (i.e. adventure and sociality) positively

influence attitude toward online shopping. Gender has a main effect on each

value. In addition, gender has a moderating effect on each path from five

shopping values to attitude toward Internet purchasing. A moderating test

reveals that the influences of convenience and lack of sociality on attitude

toward online shopping are stronger for men than for women, while the

influences of adventure, availability of information and sociality on attitude

toward online shopping are stronger for women than for men. Finally

implications and further research directions are then discussed.

Keywords: Gender differences, Online shopping values, Utilitarian values,

III

誌 謝

在獲悉博士論文口試通過的消息,心中充滿了開心與感謝,回想在交大讀博班

的五年期間,發生了許多事,也歷經了人生最低潮的階段,過程雖然辛苦,但其

實是非常值得的。回想起當初工作與課業兩頭燒,尤其是每天工作下班後拖著疲

累的身軀回到家後,還必須面對寫paper的壓力,儘管壓力很大,可是內心一直

有份執著且不肯輕易認輸的力量支撐著我,而也正因為這份執著,所以能順利畢

業。

除了自我的堅持外,也非常感謝恩師黃仁宏教授的指導,謝謝老師您這段時間

來對我的照顧與指導,我會銘記在心且會在往後的日子會更加努力。此外我也要

感謝我的爸媽,謝謝您們對我的栽培,我沒有讓您們失望,我很高興我可以讓您

們以我為榮。此外我也非常感謝我碩班的指導教授何雍慶教授,若沒有您當初幫

我寫推薦函,我也就沒有今日,非常感謝老師。在此也要感謝思榕,謝謝妳特別

請假一天陪我參加論文口試,妳的陪伴帶給我無限的信心與鼓勵。最後我還要感

謝四位口試委員,分別是林進財教授、李經遠教授、林君信教授及蔡璧徽教授,

謝謝您們的指教,使得我的論文得以臻至完整,學生在此致上我最深的謝意。由

於要感謝的人太多了,我想除了心中感激外,我更應該好好努力向上,讓大家能

夠在未來的日子裡以我為榮。

楊易淳

2010.7 於交通大學

IV

Table of Contents

Chinese Abstract……….I

English Abstract……….II

誌 謝

… … … . . . I I I

Table of Contents………...IV

Chapter 1 Introduction………1

1.1 Research Background ………..…….………...1

1.2 Objectives of This Study………...3

1.3 Organizations of the Dissertation…….………4

Chapter 2 Literature Review………..…………..……...6

2.1 Development of Conceptual Model………...6

2.2 Utilitarian Value………...10

2.3 Hedonic Value………...………...11

2.4 Main Effect of Gender on Online Shopping Value………...12

2.5 Attitude toward Online Shopping………...……...…………...17

2.6 Gender as a Moderator………...………...18

2.7 Gender Research………...………...19

2.8 Summary………...………...19

Chapter 3 Methodology……….………..21

3.1 Instrument Design………..………...21

3.2 Sampling………...………...23

3.3 Pretest and Pilot Study………...24

V

Table of Contents (Conti.)

Chapter 4 Analysis and Results………...26

4.1 Analytical Strategy……….………...26

4.2 Reliability of Measures……….………....26

4.3 Validity of Measures……….………27

4.4 Hypothesis Test………….………31

4.5 Latent Means Differences……….…………...32

4.6 Subgroup Analysis……….………...33

4.7 Summary………….………..34

Chapter 5 Conclusions and Implications……….………...36

5.1 Discussion and Conclusion………...36

5.2 Limitation………...39

5.3 Future Research………...39

Reference ………...………41

Appendix A Measurement Scales………...49

VI

List of Tables

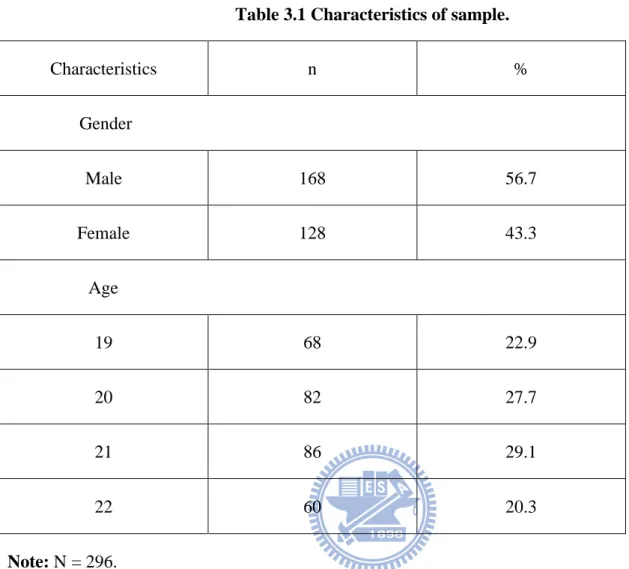

Table 3.1 Characteristics of Sample……….………24

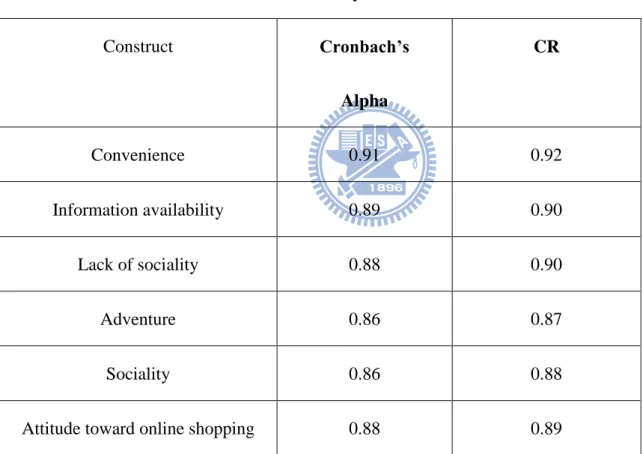

Table 4.1 Reliability of Measurement Scales………27

Table 4.2 Validity of Measurement Scales………28

Table 4.3 Results of Hypotheses and Model Statistics………..………31

Table 4.4 Latent Means Differences between Women and Men………...33

VII

List of Figures

Figure 2.1 Technology Acceptance Model………....7

Figure 2.2 Conceptual Model………...9

Figure 4.1 Original Model……….………30

1

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1 Research Background

With the rapid development of electronic commerce, the Internet has become a dominant shopping vehicle. Internet shopping has been increasing rapidly over the past years, and it has become a popular tool for delivering and trading information, services and goods (Gurley, 2000). More than 627 million people in the world have the experience of shopping online, and this trend keeps on growing (ACNielsen, 2007).

The influence of various shopping values is an important factor determining consumers’ willingness to shop online (Pui et al., 2007). Previous studies demonstrated that online shoppers engage in Internet shopping because of some benefits, such as convenience, availability of information, adventure and sociality (Pui et al., 2007). Many studies have explored individual motivations by identifying conceptual factors to elucidate Internet purchase behavior; however, few studies have discussed the factors influencing online purchase attitude (Narges et al., 2009).

Attitude toward online shopping refers to a person’s positive or negative feelings about conducting the purchasing behavior on the internet (Chiu et al., 2005; Schlosser, 2003). Attitude serves as the bridge between consumers’ background characteristics and the consumption behaviors (Armstrong and Kotler, 2000; Shwu-Ing, 2003). The consumers’ attitude towards online shopping plays a crucial

2

role in determining e-shopping behaviors (Shwu-Ing, 2003). Because attitude is difficult to change; therefore, to understand consumers’ attitudes toward online shopping enables marketing managers to predict the online shoppers’ behaviors and satisfy their needs (Armstrong and Kotler, 2000). Therefore, it is important to explore what factors generate consumers’ attitude toward Internet purchasing.

Furthermore, Jackson et al. (2001) noted that though young women and men use the Internet equally often, they use it differently, and this may influence the attitude of buying online. Therefore, it is interesting to discuss sex differences in attitude toward online consumption. Early researchers tended to explore demographic profiles of Internet buyers and functional advantages of online shopping, few stressed gender differences in online shopping attitude. In fact, the study of gender differences has been a fertile area in marketing research, but it seems that there are few studies that explore gender differences in online buying. Through the understanding of what causes gender differences in perception and attitude toward buying on the internet is beneficial in several ways. First, e-tail practitioners can understand Internet purchasing behaviors and implement e-service efficiently. Second, researchers can easily explain online shopping intention and behaviors.

Among numerous studies on online shopping, one stream discusses Internet shopping in terms of consumer perspective, while another stresses the importance of technology-oriented perspective.

3

Because the success of online shopping largely depends on consumers’ willingness to accept it; therefore, we adopted the consumer-oriented view of online shopping in this study.

1.2 Objectives of This Study

The aim of this study is to test empirically the relationship between online shopping values and attitude toward online shopping. In addition, gender role functions as a potential moderator on these relationships. This study developed a conceptual model based on previous studies. This study proposed that the five constructs of online shopping values (i.e. convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure and sociality) are positively related to Internet shopping attitude. Some hypotheses are proposed and examined with data collected from online shoppers in Taiwanese college.

This study enriches the current literature in several ways. First, though consumers’ attitude towards online shopping is a crucial factor affecting e-shopping potential (Michieal, 1998), little is known about what factors influencing their attitude (Haque et al., 2006). This study helps understand consumer attitude toward online shopping, and this helps marketing managers to clearly know critical motivators when engaging in Internet marketing.

4

Second, gender is regarded as a potential moderator on these relationships. Though the role of gender has been a fertile area in marketing research, the influence of gender roles has rarely been examined under a topic combining attitude toward online shopping with Internet shopping value. If gender does moderate the relationships between online shopping value and online shopping attitude, it can help firms design gender-specific marketing strategies to target specific group (e.g. male student).

The study seeks to answer the following research questions:

1. Is utilitarian value positively related to attitude toward online shopping? 2. Is hedonic value positively related to attitude toward online shopping? 3. Is there any gender difference in utilitarian value?

4. Is there any gender difference in hedonic value?

5. Is the relationship between online shopping value and attitude toward online shopping moderated by gender?

1.3 Organizations of the Dissertation

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Chapter one begins with introduction of our research background. Chapter two reviewed literature on utilitarian consumption value, hedonic consumption value, attitude toward online shopping, and gender difference in related research, hypotheses are then advanced. Chapter three detailed the research design and the development of the

5

research instrument. Chapter four presented the structural equation modeling of the research framework and results, followed by Chapter five suggested the conclusions and implications derived from the study.

6

Chapter 2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

This chapter reviews the literature pertaining to the constructs of the proposed model in this study. Various studies in the areas of utilitarian value, hedonic value, attitude toward online shopping, and gender differences will be analyzed to form the rationale of the proposed model.

2.1 Development of Conceptual Model

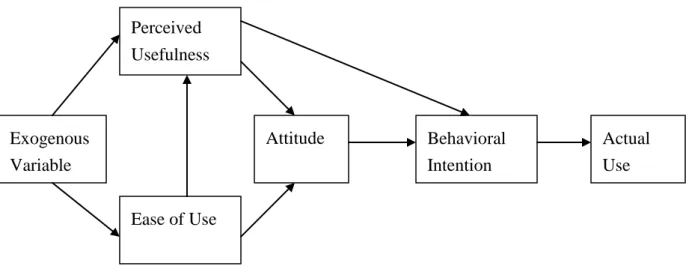

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has been extensively used in exploring user behavior in an online shopping context (Pavlou, 2003). The belief-affect-intention-behavior causality has proven valid in discussing the online shopping behaviors (Chen et al., 2003; Limayem et al., 2000). According to TAM, system use is determined by users’ behavioral intention to use and attitude. Moreover, attitude is directly affected by users’ belief about a system, such as perceived usefulness and ease of use (Davis, 1989). In addition to perceived usefulness and ease of use, Narges et al. (2009) proposed that perceived enjoyment is also a vital factor when discussing attitude toward online shopping base on TAM.

7

Figure 2.1.Technology Acceptance Model, Davis (1989)

Online shopping offers both hedonic and utilitarian aspects (Childers et al., 2001). Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use can be viewed as utilitarian aspects in online shopping environment, whereas perceived enjoyment reflects the hedonic aspects (Monsuwe et al., 2004). Hence, utilitarian and hedonic aspects can be regarded as important factors influence consumers’ attitude toward conducting Internet shopping.

As to utilitarian value we use a model suggested by Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2001) and Pui et al. (2007). Concerning hedonic value, we conduct the model proposed by Arnold and Reynolds (2003) and Pui et al. (2007).

Utilitarian value, defined as mission critical and goal oriented (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982; Batra and Ahtola, 1991), is an overall assessment of functional benefits, such as economic value, Exogenous Variable Perceived Usefulness (U) Ease of Use Attitude Behavioral Intention Actual Use

8

convenience, time savings (Jarvenpaa and Todd, 1997; Teo, 2001). There are many research concerning utilitarian value, we hereby focus on the utilitarian value of online shopping, such as convenience, availability of information and lack of sociality.

Hedonic shoppers is entertainment oriented that hedonic shopping behaviors tend to seek fun and be immersed in the process of consumption. Internet shoppers shop to seek the hedonic values such as adventure and sociality (Pui et al., 2007).

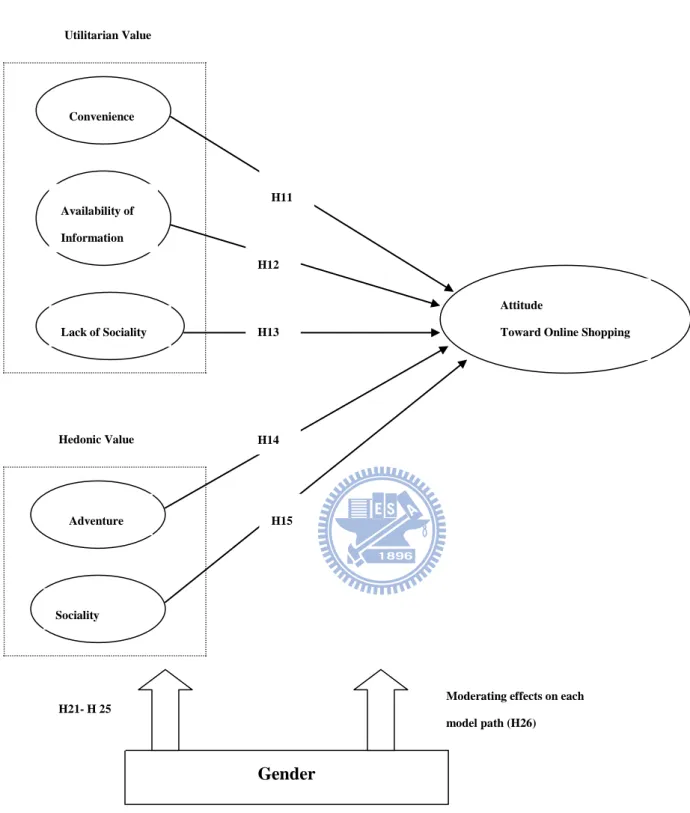

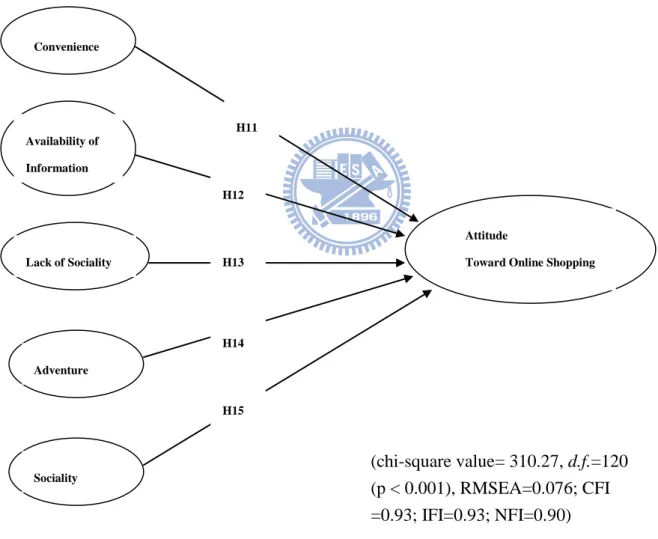

The conceptual model displayed in Fig. 2-1 suggests that five components of shopping values—convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure, and sociality—influence attitude toward online shopping. Gender has a moderating effect on each path and a main effect on each antecedent.

9

Figure 2.2. Conceptual model.

Convenience

Attitude

Toward Online Shopping Availability of Information Lack of Sociality Adventure Sociality H11 H12 H13 H14 Gender

Moderating effects on each model path (H26) H15

Utilitarian Value

Hedonic Value

10

2.2 Utilitarian value

Utilitarian value is defined as mission critical and goal oriented (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982; Batra and Ahtola, 1991). Babin et al. (1994) defined utilitarian shopping value as acquiring the benefit of the product needed, or acquiring the product more efficiently during the shopping process. Therefore, utilitarian shoppers are transaction-oriented and desire to purchase what they want efficiently and without distraction (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). Utilitarian value is an overall assessment of functional benefits, such as economic value, convenience, time savings (Jarvenpaa and Todd, 1997; Teo, 2001). Previous researchers believe that utilitarian values are the fundamental factors for people shopping online.

Utilitarian shoppers are interested in e-tailing because of some specific attributes: convenience and accessibility, availability of information and lack of sociality (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). The online medium facilitates utilitarian behavior as search costs for product information are dramatically reduced. Moe (2003) indicated that consumers’ perceived benefits of Internet shopping have an effect on their attitude of purchase on the web site, especially a positive influence of a utilitarian orientation on purchase attitude. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H11: Convenience is positively related to attitude toward online shopping.

11

H13: Lack of sociality is positively related to attitude toward online shopping.

2.3 Hedonic value

Hedonic value, defined as consumption behaviors that relate to fantasy, happiness, sensuality, and enjoyment (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982), is an overall assessment of experiential benefits. Compared with conventional utilitarian shopping values, the merit of hedonic value is experiential and emotional. The reason why hedonic consumers do shopping is not for physical objective but for the shopping process instead. Research concerning hedonic motivation becomes more popular lies in two reasons. One is the obvious value that appeals to consumers to patronage the website, the other is the fact that hedonic value is the extension of utilitarian value and these two values seem to become crucial factors in keeping competitive advantage (Parsons, 2002).

Numerous studies used to adopt hedonic value dimensions to discuss in-store shopping. Nevertheless, there are more and more research using hedonic value dimensions to explore online shopping. Except for the freedom to search, hedonic value is also an important element. Mathwick et al. (2001) discusses the experiential value of online shopping, and enjoyment and aesthetics should be viewed as hedonic value. Kim and Shim (2002) propose that consumers go on line is not only for information and products, but also for emotional satisfaction. Hedonic online shoppers are accustomed to active pursuit while online. They often browse website, search for new items and

12

download updated information, actually they are bathed in the process of enjoyment. In addition, hedonic shoppers were attracted to online environment because the virtual community offers social relationship (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001).

According to previous studies, it appears that hedonic values play important roles in online shopping (Pui et al., 2007). Childers et al. (2001) indicated that hedonic orientations are strong predictors of attitudes toward online shopping. Hedonic shopping values were positively related to attitude toward online shopping and intentions to shop online (Menon and Kahn, 2002). In view of the above, it is plausible to expect a positive relationship between hedonic values and attitude toward online shopping. It is thus hypothesized that:

H14: Adventure is positively related to attitude toward online shopping.

H15: Sociality is positively related to attitude toward online shopping.

2.4 Main effects of gender on online shopping values

This study categorizes utilitarian value into convenience, availability of information and lack of sociality, they are detailed as follows.

13

2.4.1 Convenience

Convenience is defined as time savings and effort savings, including physical and mental effort. Convenience is a crucial attribute for consumers when shopping online.

Shopping online makes it easy for consumers to locate merchants, find items, and procure offerings (Balasubramanian, 1997). Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2001) mentioned that internet shopping provides a more comfortable and convenient shopping environment. Consumers do not have to leave their home and they can also browse for items by category or online store. Schaffer (2000) argued that a convenient internet shopping provides a short response time and minimizes customer effort.

Swaminathan et al. (1999) reported that male internet buyers were more convenience oriented and less motivated by social interaction than women Internet buyers. Alreck and Settle (2002) indicated that women have more positive attitudes toward shopping, while men prefer shopping via internet (Alreck and Settle, 2002). Hence,

H21: Men have higher scores on convenience than women.

2.4.2 Information availability

Bakos (1997) postulated that the internet includes abundant public information resources that can be easily collected. For online shoppers, internet is the most efficient means to get related

14

information. The internet as a medium facilitates searching both product specifications and price information. Price is an important reference and adolescent consumers often compare price between multiple websites.

Women tend to be more sensitive to related information online than men when making judgments (Meyers-Levy and Sternthal, 1991), bringing out subsequent purchase attitudes and intentions presented by men and women to differ. In other words, females make greater use of cues than males. Cleveland et al. (2003) find that when executing consumption women seek more information than men. Hence,

H22: Women have higher scores on information availability than men.

2.4.3 Lack of sociality

Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2001) indicate that online shopping enables people to execute a transaction without contacting others, and online buyers have more freedom and control over the transaction. One advantage of online shopping is that online buyers can decide to buy or not and the transaction is under their control. In addition, while shopping online, it turns out that people can avoid social interaction and crowded environment.

15

Since men and women differ significantly in conventional buying motivations, we seem to assume that this would also be the case on the internet purchasing. Swaminathan et al. (1999) reported that male internet buyers were less motivated by social interaction than women Internet buyers. Compared with men, women tend to enjoy shopping (Alreck and Settle, 2002), and they can have more social interactions in the process of consumption. Computer-mediated shopping does not offer women much social contact. Hence,

H23: Men have higher scores on lack of sociality than women.

Based on Pui et al. (2007), the hedonic values in this study comprise adventure and sociality, they are detailed as follows.

2.4.4 Adventure

Adventure refers to the fact that shopping can bring stimulation and excitement, meaning that consumers can run across novelty and interesting affairs in the process of fantastic shopping (Westbrook and Black, 1985). Experienced consumers are inclined to view the shopping experience as thrills, excitement and amazement. Babin et al. (1994) regard adventurous aspect of shopping as an element that may produce hedonic shopping value. Sherry (1990) addresses that in the shopping process shoppers pay more attention to sensual satisfaction rather than the product itself.

16

Women stress emotional and psychological involvement in the whole shopping and buying process, while men emphasize efficiency and convenience in obtaining buying outcomes (Dittmar et al., 2004). In other words, the added value attached to shopping process may play a much more prominent role for female consumers, whereas male consumers’ primary concerns are to get the product only, shopping process may function as nothing meaningful for men. Hence,

H24: Women have higher scores on adventure than men.

2.4.5 Sociality

Sociality, grounded in McGuire’s (1974) collection of affiliation theories of human motivation, suggesting that people put emphasis on cohesiveness, affiliation and affection in interpersonal relationships. Tauber (1972) indicated that shoppers are fond of affiliating with reference groups and interacting with those who have similar interests. Westbrook and Black (1985) regarded affiliation as a shopping value, and Reynolds and Beatty (1999) stress the importance of social motivations for shopping. Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2001) propose that virtual community is a new platform of sociality, meaning that Internet shopper can share updated information and related shopping experiences with one another and compared with traditional social benefits from friends, virtual community furnishes shoppers with fresh pleasure.

17

Alexander (1947) mentioned that the experimental psychologists have developed very convincing evidence that women are more prone to social contacts than men, and reasonably convincing evidence that they have more aptitude for maintaining such contacts. Based on the results of carefully conducted aptitude and interest tests, the gender differences seem to be notable. Dittmar et al. (2004) address that women, compared with men, have a strong desire for emotional and social gratification in the Internet buying environment. Hence,

H25: Women have higher scores on sociality than men.

2.5 Attitude toward online shopping

Attitude towards a behavior refers to ―the degree to which a person has favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior of the question‖ (Grandom and Mykytyn, 2004). Attitude can be viewed as the bridge between consumers’ background characteristics and the consumption that fulfills their needs (Armstrong and Kotler, 2000; Shwu-Ing, 2003). A person’s shopping choices are influenced by attitude (Haque et al., 2006).

Attitude toward online shopping can be defined as a person’s positive or negative feelings about conducting the purchasing behavior on the internet (Chiu et al., 2005; Schlosser, 2003). The consumers’ attitude towards online shopping plays an important role in determining e-shopping

18

behaviors (Shwu-Ing, 2003). Because attitude is difficult to change; therefore, to understand consumers’ attitudes toward online shopping enables marketing managers to predict the online shoppers’ behaviors and satisfy their needs (Armstrong and Kotler, 2000).

2.6 Gender as a Moderator

Numerous studies related to consumer behavior indicated that males and females differ in their processing of information (Holbrook, 1986; Palmer and Bejou, 1995). In other words, males and females differ in the response to alternative consuming stimuli (Meyers-Levy, 1989).The differences between males and females suggest the potential moderating role of gender in the influence of shopping values (convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure, and sociality) on attitude toward Internet purchasing, because online shopping causes different stimuli than those of physical store. Therefore, males and females would vary in making judgments when facing relevant information online (Meyers-Levy and Sternthal, 1991), and this may result in gender differences in attitudes toward Internet purchasing. The following hypotheses are rooted in this gendered analysis.

H26: The relationship between online shopping value and attitude toward online shopping is

19

2.7 Gender research

The discrepancy between men and women really does exist, including physical and mental differences. The differences drew marketing researchers’ interest that brought out related studies, such as gender differences in decision-making styles (Vincent and Walsh, 2004), attitudes toward Internet, catalog, and store shopping (Alreck and Settle, 2002), attitudes toward Internet and store shopping (Dholakia and Uusitalo, 2002), online and store buying motivations (Dittmar et al., 2004), perceived risk of buying online (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004), and Internet shopping behavior (Chang and Samuel, 2004). Moreover, Jackson et al. (2001) noted that though young women and men use the Internet equally often, they use it differently, and this may influence the motivations of buying online. This steam of research may be a fertile area in marketing.

2.8 Summary

This chapter developed a conceptual framework based on technology acceptance model. The literature review provided necessary and sufficient statements to support the hypotheses which specify the relationships between the constructs: convenience and attitude toward online shopping, information availability and attitude toward online shopping, lack of sociality and attitude toward online shopping, adventure and attitude toward online shopping, and sociality and attitude toward online shopping. In addition, gender has main effect on convenience, information availability, lack of sociality, adventure and sociality, and the relationship between online shopping value and attitude

20

toward online shopping is moderated by gender. The following chapter illustrates the methodology which will be used to examine the model.

21

Chapter 3. Methodology

This chapter presents the methodology used to examine the conceptual model. The following addresses (1) the instrument design, (2) sampling, and (3) pretest and pilot study used in this study. The details are presented as follows.

3.1 Instrument Design

The scales in this study are derived from previous studies, and are modified according to the special conditions of Internet shopping. The scales are presented in the Appendix A. The questionnaire is composed of three parts, the first part included 15 items to measure the utilitarian and hedonic values of Internet shopping. The second part included four items measuring the Internet shoppers’ attitude toward online shopping. The last part collected the demographic data of the subject. Detailed definitions of the dimensions are provided in the following text.

Utilitarian values

The items of convenience are derived from the questionnaire of Eastlick and Feinberg (1999) and Pui et al. (2007). Information availability was assessed using a 3-item version of the scale developed by Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2001) and Pui et al. (2007), while the items of lack of sociality are adopted from the scale developed by Pui et al., (2007). Respondents were scored on a scale ranging from 1 = total disagreement to 7 = total agreement. The internal consistency of each shopping value

22

met the standard of Cronbach’s α in excess of .7 with sufficient reliability (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

Hedonic Values

The items of adventure value were adopted from the questionnaire of Arnold and Reynolds (2003), whereas the items of sociality value come from the scale developed by Arnold and Reynolds (2003) and Pui et al. (2007). Item responses were on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = total disagreement to 7 = total agreement. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each shopping value exceeded .7, indicating that the scale had adequate reliability (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

Attitude toward Online Shopping

Attitude refers to a consumer's overall evaluation of online shopping as a way of shopping, which can be positive / favorable or negative / unfavorable. The items used to measure the attitude toward online shopping were modified from the scale developed by Taylor and Todd (1995). Attitude toward online shopping was measured by four items. Respondents respond to the items using a seven-scale Likert-type scale. The alpha coefficient of this variable was 0.88 with sufficient reliability

23

3.2 Sampling

The data came from Taiwanese universities. Respondents were approached in and around a university community located in a major metropolitan area during October of 2009. Sampling is conducted via convenient sampling. Study subjects were undergraduate students in Taiwan who have shopped online. Notably, university students play an important role in online shopping and represent a long-term potential market (Bruin and Lawrence, 2000). A self-administered questionnaire was randomly distributed to 600 students attending the chosen school. Of the 308 questionnaires returned, 12 were incomplete. The remaining 296 were valid for analysis, representing a response rate of 49.33%. Among the 296 subjects, 168 (56.7%) were males and 128 (43.3%) were females.

24

Table 3.1 Characteristics of sample.

Characteristics n % Gender Male 168 56.7 Female 128 43.3 Age 19 68 22.9 20 82 27.7 21 86 29.1 22 60 20.3 Note: N = 296.

3.3 Pretest and Pilot Study

Pretest was adopted before conducting formal survey, confirming that the questionnaire had no semantic problem. Two Ph.D. candidates majoring in marketing serve as the subjects of the pretests. The pretest was performed in an open-end format that the subjects could propose any questions about the items. During the process, the subjects suggested that the phrasing of certain items could be revised, which included utilitarian value, hedonic value, and attitude toward online shopping. According to several suggestions from the pretest subjects, we slightly revised wording of the items.

25

After the pretest, we conducted pilot test by distributing 60 questionnaires to some undergraduate students having online shopping experience. A total of 30 questionnaires were received for reliability analysis. This study examined Cronbach’s alpha of all constructs, and we eliminated some items that the Cronbach’s alpha are below 0.7. The alpha coefficients of remaining items were above 0.7. Finally, nineteen items remained in the questionnaire were used for later analysis.

3.4 Summary

This chapter provided information for instrument design and data collection. The measurement scales for the constructs were adopted from previous studies. The following chapter will illustrate statistical technique, structural model, fit indices of model fit and the result of the hypotheses testing.

26

Chapter 4. Analysis and Results

This chapter presents the results from the data analysis by using LISREL 8.51computer software. The reliability and validity of the constructs are presented, followed by the discussion of model fit. Finally, the hypotheses and the model are tested and the results are elaborated.

4.1 Analytical strategy

This study used structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the relationships among the variables. SEM enables researchers to definitely test research hypotheses concerning the relationships among research constructs. This study used LISREL 8.51 to assess the fit of the measurement and structural models, and calculated the values of incremental fit index (IFI) (Bollen, 1989), comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990), normed fit index (NFI) (Bentler and Bonett, 1980), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Steiger, 1990). If the values of IFI, CFI and NFI exceed the cut-off value of 0.9, and the value of RMSEA is below the cut-off values 0.08, then the model is said to be acceptable (Hu and Bentler, 1999). In addition to the fit indices, this study uses the parameter estimates in the structural model to test the hypotheses.

4.2 Reliability of Measures

To assess the internal consistency of the constructs, the Cronbach alpha values were examined and were shown on Table 4.1. The result of six constructs ranged from 0.86 to 0.91, meeting the

27

lower standard of 0.7. In addition, the composite reliability (CR) shows the internal consistency of the indicators assessing a given factor and is calculated by the formula suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). If the value is higher than 0.7, we can conclude that the indicator is acceptable for a composite reliability (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As seen in Table 4.1, the CR scores of all constructs exceeded the acceptable levels.

Table 4.1. Reliability of Measurement Scales

Construct Cronbach’s Alpha CR Convenience 0.91 0.92 Information availability 0.89 0.90 Lack of sociality 0.88 0.90 Adventure 0.86 0.87 Sociality 0.86 0.88 Attitude toward online shopping 0.88 0.89

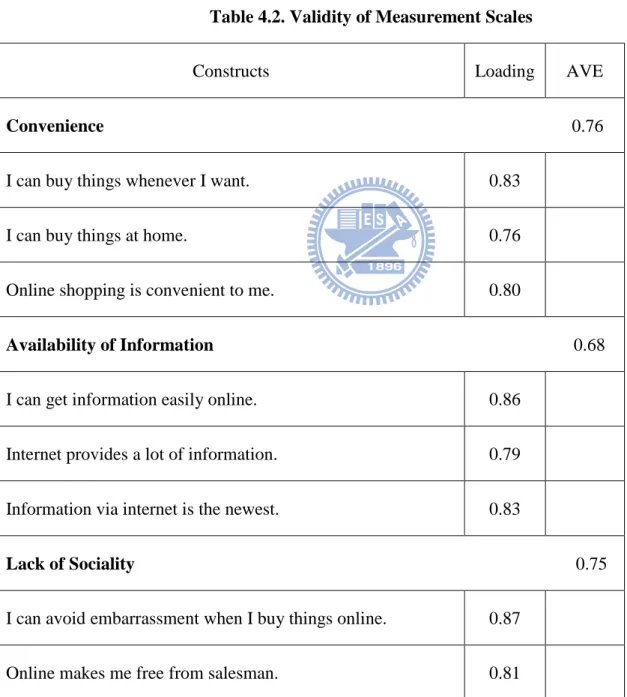

4.3 Validity of Measures

Before testing the hypotheses, this study first conducted average variances extracted (AVE) to ensure that respondents can explicitly distinguish the variables in this study. The average variances

28

extracted (AVE) represents the amount of variance captured by the construct’s measures relative to measurement error and the correlations among the latent variables. The analysis indicated that all items had factor loadings higher than 0.7 (see Table 4.2). As seen in Table 4.2, all of the AVE values were larger than 0.5, revealing good convergent and discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Table 4.2. Validity of Measurement Scales

Constructs Loading AVE

Convenience 0.76

I can buy things whenever I want. 0.83 I can buy things at home. 0.76 Online shopping is convenient to me. 0.80

Availability of Information 0.68

I can get information easily online. 0.86 Internet provides a lot of information. 0.79 Information via internet is the newest. 0.83

Lack of Sociality 0.75

I can avoid embarrassment when I buy things online. 0.87 Online makes me free from salesman. 0.81

29

Online makes me free from social interaction. 0.84

Adventure 0.64

Online shopping is an adventure. 0.90 I find shopping stimulating. 0.81 Online shopping makes me feel like I am in my own universe. 0.85

Sociality 0.67

I can exchange information with friends online. 0.78 I can develop friendships with other internet shoppers. 0.83 I can extend personal relationship online. 0.81 I can exchange information with friends online. 0.85

Attitude toward online shopping 0.72

Using the Internet to buy things is a good idea. 0.88 I like the idea of busing what I need via the Internet. 0.81 Using the Internet to buy things is a wise idea. 0.86 Using the Internet to buy things would be pleasant. 0.82

Overall, all the constructs show very good reliability and validity. Since we confirmed the reliability and validity of constructs, we then test our hypotheses by estimating the full model. A structural model was used to test the previously presented hypotheses. SEM results for testing the

30

model depicted in Figure 4.1 revealed that the fit statistics of model were within the recommended range (chi-square value= 310.27, d.f.=120 (p < 0.001), RMSEA=0.076; CFI =0.93; IFI=0.93; NFI=0.90). All of these fit indices are within the acceptable limit, suggesting that the overall structural model provides a good fit with the data. Owing to an excellent fit between the structural model and the data, this study then tested the hypotheses according to its parameter estimates.

Figure 4.1. Original model.

Convenience

Attitude

Toward Online Shopping Availability of Information Lack of Sociality Adventure Sociality H11 H12 H13 H14 H15 (chi-square value= 310.27, d.f.=120 (p < 0.001), RMSEA=0.076; CFI =0.93; IFI=0.93; NFI=0.90)

31

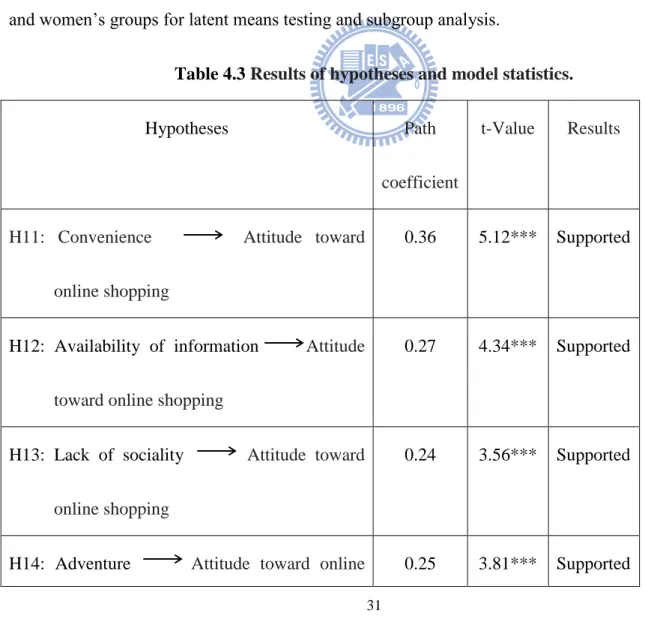

4.4 Hypothesis Test

Hypothesis 11-15 depicted that online shopping values are positively related to attitude toward

Internet shopping. As observed, Table 4.3 represents summaries of the hypothesis tests. The

structural links to attitude toward Internet shopping from convenience (H11), availability of

information (H12), lack of sociality (H13), adventure (H14), and sociality (H15) are completely supported. Therefore, the model is supported as five online shopping values positively influence

attitude toward online shopping, indicating that hypothesis 11-15 were fully supported. In addition,

this study divided the sample respectively by men and women, further investigating across men’s and women’s groups for latent means testing and subgroup analysis.

Table 4.3 Results of hypotheses and model statistics.

Hypotheses Path coefficient

t-Value Results

H11: Convenience Attitude toward

online shopping

0.36 5.12*** Supported

H12: Availability of information Attitude toward online shopping

0.27 4.34*** Supported

H13: Lack of sociality Attitude toward online shopping

0.24 3.56*** Supported

32

shopping

H15: Sociality Attitude toward online shopping

0.18 3.43*** Supported

***p < 0.01.

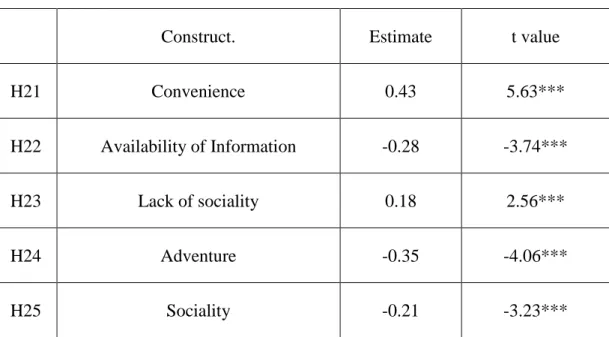

4.5 Latent Means Difference

Based on the above measurement model, latent means testing is conducted (Byrne, 2001). Table 4.4 represents the results of latent means testing. Given that the women group functions as the reference group, the members’ factor means are hence fixed to zero to examine the latent means difference between the two subgroups. As seen in Table 4.4, the significantly positive estimate of the latent means difference across the subgroups for construct H21 and H23 indicates that the scores on convenience, lack of sociality are significantly higher for men than for women. On the other hand, the significantly negative estimate of the latent means difference across the subgroups for construct H22, H24 and H25 indicates that the scores on availability of information, adventure and sociality are significantly higher for women than for men.

33

Table 4.4 Latent means difference between women and men

Construct. Estimate t value H21 Convenience 0.43 5.63*** H22 Availability of Information -0.28 -3.74*** H23 Lack of sociality 0.18 2.56*** H24 Adventure -0.35 -4.06*** H25 Sociality -0.21 -3.23*** *** p < 0.01

4.6 Subgroup Analysis

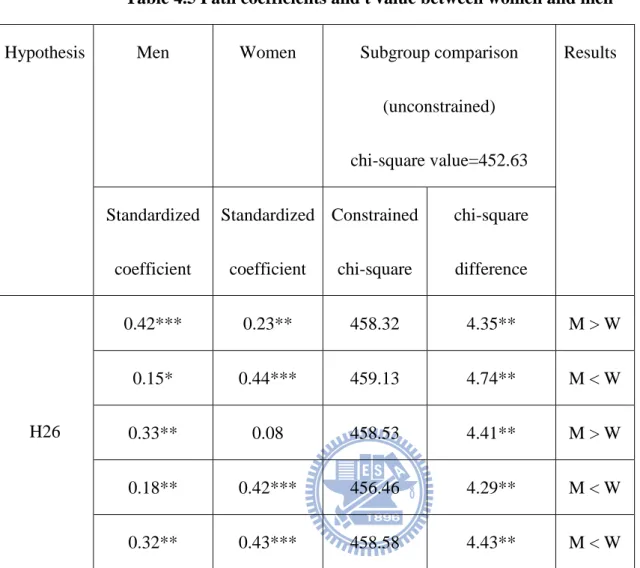

In order to examine the existence of the moderating effects on the structural model, this study conducted subgroup analyses (Byrne, 2001; Singh, 1995). As depicted in Table 4.5, the results demonstrated the moderating effects of gender along with path coefficients.

34

Table 4.5 Path coefficients and t value between women and men

Hypothesis Men Women Subgroup comparison (unconstrained) chi-square value=452.63 Results Standardized coefficient Standardized coefficient Constrained chi-square chi-square difference H26 0.42*** 0.23** 458.32 4.35** M > W 0.15* 0.44*** 459.13 4.74** M < W 0.33** 0.08 458.53 4.41** M > W 0.18** 0.42*** 456.46 4.29** M < W 0.32** 0.43*** 458.58 4.43** M < W *** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.10

Note: M = Men; W = Women

4.7 Summary

According to the entire sample (see Table 4.3), we found that five paths are all significant (H11, H12, H13, H14, and H15 are supported), indicating that the five online shopping values are positively related to attitude toward Internet shopping. Latent means testing between women and men group in Table 4.4 reveals that gender have main effects on convenience, availability of information, lack of

35

sociality, adventure and sociality. The results indicate that women tend to have higher scores than men on availability of information (H22), adventure (H24) and sociality (H25), whereas men tend to have higher scores than women on convenience (H21) and lack of sociality (H23). Last, the results in Table 4.5 indicate that the influence of convenience and lack of sociality on attitude toward online shopping are stronger for men than for women, while the influences of availability of information, adventure and sociality on attitude toward online shopping are stronger for women than for men. The result indicated that the relationship between online shopping value and attitude toward online shopping is moderated by gender (H26).

36

Chapter 5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1 Discussion and Conclusion

This study proposed a framework for enhancing our understanding of consumers’ attitudes toward online shopping. These findings indicated that utilitarian values (i.e. convenience, availability of information and lack of sociality) and hedonic values (i.e. adventure and sociality) are important predictors of consumer’s attitude toward Internet purchasing. Boosting the five shopping values can induce positive attitude. Though the causal relationship among variables is concluded at this time, the causality of the variables needed to be further examined with longitudinal designs. In addition, since the samples were drawn solely from Taiwanese context, future research can assess the generalizability of findings in other cultural contexts.

Because utilitarian shopping values reflect usefulness and ease of use aspects (Monsuwe et al., 2004), this study found that utilitarian values positively impact consumers’ attitude toward adopting a new technology or system, congruent with the theory acceptance model (Lee et al., 2006). In the other hand, hedonic shopping values reflect enjoyment aspects (Monsuwe et al., 2004), and hedonic shopping values were found to have positive effect on consumers’ attitude toward online shopping (Davis et al., 1989). The result is consistent with the findings of Narges et al. (2009) that perceived enjoyment is also a crucial determinant when discussing attitude toward online shopping base on theory acceptance model (TAM).

37

Regarding the effect of gender, gender is shown to have main effects on five shopping values, such as convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure, and sociality. The significant differences between convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure, and sociality means for women and men bring critical messages for management. The significantly higher means of convenience and lack of sociality for men than women indicated that male internet buyers were more convenience oriented and less motivated by social interaction than women internet buyers, congruent with the findings of Swaminathan et al. (1999). In addition, the significantly higher means of adventure and sociality for women than men indicated that females are more motivated by emotional factors (for example, adventure, sociality), as compared to males, and the findings of this study were consistent with those of Arnold and Reynolds (2003). Last, the significantly higher means of availability of information for women than men indicated that women tend to be more sensitive to related information online than men when making judgments, they seek more information than men when making consumption decision, congruent with the findings of Meyers-Levy and Sternthal (1991) and Cleveland et al. (2003).

Gender also has moderating effects on paths going from convenience, availability of information, lack of sociality, adventure, and sociality to attitude toward Internet purchasing. The findings of significant gender differences suggest that males and females have different gender-based perceptions that may eventually influence their preferences during Internet purchasing. Based on the

38

findings of gender differences, two implications are presented as follows.

First, a stronger influence of convenience and lack of sociality on attitude toward online shopping for males (versus females) indicated that it is important for e-tailers targeting the male consumers to stress functional benefits (e.g., convenience and lack of sociality) to satisfy those male consumers. Therefore, males will have more positive attitude if they feel that the Internet shopping provide them with convenience and lack of sociality benefits, and the positive attitude may enhance online purchase intentions.

Second, a stronger influence of adventure, sociality and availability of information on attitude toward online shopping for females (versus males) suggested that female consumers have a stronger desire for the sensory pleasures associated with online shopping. Online marketers may work on producing some topics related to hedonic factors when targeting female consumers. For example, to attract females, online marketers should provide the sociality value by creating a platform for sharing information and related shopping experiences. In addition, e-tailers can demonstrate for females how fun to purchase products online and engage them with abundant information on the website, and this may eventually stimulate their positive attitudes and increase purchase intentions.

39

5.2 Limitations

This study has some limitations. The first limitation of this study is that all participants were students. Although they may shop online, students typically have less income than non-student consumers. Future researchers can select other representative samples to assess the generalizability of findings. Second, the samples were drawn solely from Taiwanese context, this may result in potential cultural limitation that differences may exist from one country to another. Future research can avoid this by exploring different cultural contexts. Third, the use of a cross-sectional research design may make causality difficult to determine. This study has the methodological limitation that causal relationships among variables cannot be concluded. Longitudinal designs are required to examine the causality of the variables.

5.3 Future Research

In addition to some limitations, this study provides some directions for future research. First of all, one important area for future research is to explore gender differences concerning utilitarian and hedonic values of web-based shopping by culture. Suh and Kwon (2002) suggested that consumers from different cultures have different attitudes, preferences and values, thus consumers with different cultural background may have different attitudes toward computer-mediated consumption. It is interesting to see how the results of this study would vary in different cultural settings. Second, data for this study was collected from students in Taiwan’s universities, it is interesting to duplicate the

40

study in other consumer market segments (i.e. age, education, income) to test the generalization of

findings. Last, study findings provided preliminary evidence concerning the relationships between online shopping values and attitude toward shopping online. Future research can examine these relationships and other possible factors that may mediate or moderate the effect of shopping values on attitude toward Internet shopping. Despite the limitations, this study does furnish a fertile direction for internet marketing.

41

REFERENCES

AC Nielsen (2007). Seek and You Shall Buy, Entertainment and Travel, retrieved from, http://www2acnielsen.com/news/20051019.shtml.

Alexander, R. S. (1947), Some aspects of sex differences in relation to marketing, The

Journal of Marketing, 12, 158-172.

Alreck, P., and Settle R. B. (2002), Gender effects on internet, catalogue and store shopping, Journal

of Database Marketing, 9, 150–162.

Armstrong, G., and Kotler, P. (2000), Marketing, Paper presented at the 5th ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 153-154.

Babin, B. J., William, R. D., and Mitch, G. ( 1994), Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value, Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 644–656.

Bakos, J. Y. (1997), Reducing buyer search costs: Implications for electronic marketplaces, Management Science, 43, 1676–1692.

Balasubramanian, S. (1997). Two Essays in Direct Marketing. Yale University, New Haven Press.

Batra, R., and Ahtola, O. T. (1991), Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of customer attitudes, Marketing Letters, 12, 159–170.

42

Bentler, P. M. (1990), Comparative fit indexes in structural models, Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bentler, P. M., and Bonett, D. G. (1980), Significant tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures, Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606.

Bollen, K. A. (1989), A new incremental fit index for general structural models, Sociological

Methods and Research, 17, 303–316.

Bruin, M., and Lawrence, F. (2000), Differences in spending habits and credit use of college students,

Journal of Consumer Affair, 34(1), 113-133.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and

programming. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chang, J., and Samuel, N. (2004), Internet shopper demographics and buying behaviour in Australia, Journal of American Academy Business, 5, 171–176.

Chen, S. J., and Chan, T. Z. (2003), A descriptive model of online shopping process: Soe empirical results, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14, 556-569.

Childers, T. L., Carr, C. C., Peck, J., and Carson, S. (2001), Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior, Journal of Retailing, 77, 511-535.

Chiu, Y. B., Lin, C. P., and Tang, L. L. (2005), Gender differs: Assessing a model of online purchase intentions in e-tail service, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 16(5), 138-149.

43

Cleveland, M., Babin, B. J., Laroche, M., Ward, P., and Bergeron, J. (2003),

Information search patterns for gift purchases: A cross-national examination of gender differences, Journal of Consumer Behavior, 3, 20–47.

Cole, D. A., Maxwell, S. E., Arvey, R., and Salas, E. (1993), Multivariate group comparisons of variable systems: MANOVA and structural equation modeling. Psychological Bulletin, 114(11), 174–184.

Davis, F. D. (1989), Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology, MIS Quarterly, 13, 319-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., and Warshaw, P. R. (1989), User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models, Management Science, 35(8), 982-1003.

Dholakia, R. R., and Uusitalo, O. (2002), Switching to electronic stores: Consumer characteristics and the perception of shopping benefits, International Journal of

Retail Distribution Management, 30, 459–469.

Dittmar, H., Long, K., and Meek R. (2004), Buying on the Internet: Gender differences in on-line and conventional buying motivations. Sex Roles, 50, 423– 444.

Eastlick, M. A., and Feinberg, R. A. (1999), Shopping motives for mail catalog shopping, Journal of

Business Research, 45(3), 281–290.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981), Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50.

44

Garbarino, E., and Strahilevitz, M. (2004), Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation, Journal of

Business Research, 57, 768–775.

Grandom, E., and Mykytyn, P. (2004), Theory-based instrumentation to measure the intention to use electronic commerce in small and medium sized businesses, Journal of Computer Information

Systems, 44(3), 44-57.

Gurley, J. W. (2000), The one Internet metric that really matters, Fortune, 2, 141-392.

Haque, A., Sadeghzadeh, J., Khatibi, A. (2006), Identifying potentiality online sales in Malaysia: A study on customer relationships online shopping, Journal of Applied Business Research, 22(4), 119-130.

Hirschman, E. C., and Holbrook, M. B. (1982), Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions, Journal of Marketing, 46, 92–101.

Holbrook, M. B. (1986), Aims, concepts and methods for the representation of individual differences in aesthetic response to design features, Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 337-347.

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999), Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Jackson, L. A., Ervin, K. S., Gardner, P. D., and Schmitt, N. (2001), Gender and the Internet: Women communicating and men searching, Sex Roles, 44, 363–379.

45

Jarvenpaa, S. L., and Todd, P. A. (1997), Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the world wide web, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 1, 59–88.

Kim,Y. M., and Shim, K. Y. (2002), The influence of intent shopping mall characteristics and user traits on purchase intent, Iris Marketing Review, 15, 25–34.

Lee, H. H., Fiore, A. M., and Kim, J. (2006), The role of the technology acceptance model in explaining effects of image interactivity technology on consumer responses. International

Journal of Retail Distribution Management, 34(8), 621-644.

Limayem, M., Khalifa, M., and Frini, A. (2000), What makes consumers buy from internet: A longitudinal study of online shopping, IEEE, 30(4), 176-189.

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., and Rigdon, E. (2001), Experiential value:

Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment, Journal of Retailing, 77, 39–56.

McGuire, W. (1974), Psychological motives and communication gratification.

In J. F. Blumer, &Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communication: Current perspectives on

gratification research. Beverly Hills: Sage Press.

Menon, S., and Kahn, B. (2002), Cross-category effects of induced arousal and pleasure on the internet shopping experience, Journal of Business Research, 78, 31-40.

46

Meyers-Levy, J. (1989), Priming effects on product judgments: A hemispheric interpretation,

Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 76-86.

Meyers-Levy, J., and Sternthal, B. (1991), Gender differences in the use of message cues and judgments, Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 84-96.

Michieal, K. (1998). E-shock the electronic shopping revolution: Strategies for retailers and

manufactures. London, Mac Millan Business.

Moe, W. W. (2003), Buying, searching, or browsing: Differentiating between online shoppers using in-store navigational clickstream, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 173-184.

Monsuwe, T. P., Dellaert, B. G. C., and de Ruyter, K. R. (2004), What drives consumers to shop online: A literature review, International Journal of Services Industry Management, 15(1), 102-121.

Narges, D., Laily, H. P., Sharifah, A. H., Samsinar, M. S., and Ali, K. (2009), Factors affecting students’ attitude toward online shopping, African Journal of Business Management, 3(5), 200-209.

Nunnally, J. C., and Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Palmer, A. and Bejou, D. (1995), The effects of gender on the development of relationships beteen clients and financial adviers, The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 13(3), 18-27.

47

Parsons, A. G. (2002), Non-functional motives for online shoppers: Why we click,

The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19, 380–392.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003), Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101-134.

Pui, L. T., Chechen, L., and Tzu, H. L. (2007), Shopping motivations on Internet: A study based on utilitarian and hedonic value, Technovation, 27, 774-787.

Reynolds, K. E., and Beatty, S. E. (1999), A relationship customer typology, Journal

of Retailing, 75, 509–523.

Schaffer, E. (2000), A better way for web design, Information Week, 784, 194-202.

Schlosser, A. E. (2003), Experiencing products in the virtual world-the role of goal and imagery in influencing attitudes, Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 184-198.

Sherry, J. F. (1990), A sociocultural analysis of Midwestern flea market, Journal of

Consumer Research, 17, 13–30.

Shwu-Ing, W. (2003), The relationship between consumer characteristics and attitude toward online shopping, Management Intelligence Planning, 21(1), 37-44.

Singh, J. (1995), Measurement issues in cross-national research, Journal of International Business

48

Steiger, J. H. (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach,

Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180.

Suh, T., & Kwon, I. W. (2002). Globalization and reluctant buyers. International Marketing Review,

19, 663–680.

Swaminathan, V., Lepowska, W. E., and Rao, B. P. (1999), Browsers or buyers in cyberspace: An investigation of factors influencing electronic exchange, Journal

of Computer-Mediated Communication, 5, 224-234.

Tauber, E. M. (1972), Why do people shop, Journal of Marketing, 36, 46–49.

Taylor, S. and Todd, P. A. (1995), Decomposition of cross effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12(2), 137-155.

Teo, T. (2001), Demographic and motivation variables associated with Internet usage activities, Internet Research, 11, 125–137.

Vincent, W. M., and Walsh, G. (2004), Gender differences in German consumer decision-making styles, Journal of Consumer Behavior, 3, 331–348.

Westbrook, R. A., and Black, W. C. (1985), A motivation-based shopper typology,

Journal of Retailing, 61, 78–103.

Wolfinbarger, M., and Gilly, M. (2001), Shopping online for freedom, control and fun, California

49

Appendix A- Measurement Scales

(Respondents were requested to answer the following questions from totally disagreement to totally agreement on a 7-point Likert scale except for attitude toard online shopping.)

Convenience (Eastlick and Feinberg, 1999; Pui et al., 2007)

1-1 I can buy things whenever I want. 1-2 I can buy things at home.

1-3 Online shopping is convenient to me.

Availability of information (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001; Pui et al., 2007)

2-1 I can get information easily online. 2-2 Internet provides a lot of information. 2-3 Information via internet is the newest.

Lack of society (Pui et al.,2007)

3-1 I can avoid embarrassment when I buy things online. 3-2 Online makes me free from salesman.

50

Adventure (Arnold and Reynolds,2003 ;Pui et al.,2007)

4-1 Online shopping is an adventure. 4-2 I find shopping stimulating.

4-3 Online shopping makes me feel like I am in my own universe.

Sociality (Arnold and Reynolds,2003 ;Pui et al.,2007)

5-1 I can exchange information with friends online. 5-2 I can develop friendships with other internet shoppers. 5-3 I can extend personal relationship online.

Attitude toward online shopping (Taylor and Todd, 1995)

6-1 Using the Internet to buy things is a good idea. 6-2 I like the idea of busing what I need via the Internet. 6-3 Using the Internet to buy things is a wise idea. 6-4 Using the Internet to buy things would be pleasant.

51