A Case Study of Advancing International Distance

Education between Taiwanese and Japanese

Universities

Wei-Jane Lin, Hsiu-Ping Yueh and Michihiko Minoh

Abstract

This paper presents a case of the implementation of international distance courses between two universities of Taiwan and Japan in Asia-Pacific area. It reports the design of activities engaged in learning with supports of various communication tools. It also examines the students’ interaction and context of learning in distance education. The paper begins by briefly introducing the initiatives, the curriculum and the instructional design on implementation of the case. It then presents results of the study with discussion, along with assessment data available on its success. Meanwhile, it also explores cultural interaction among students and class dynamics observed throughout this study. Finally, this paper closes by making recommendations for further research possibilities and practical applications aiming at enhancing international distance education.

Keywords: international distance education, learning activity design, cultural interaction

Introduction

Over the past decades, a considerable number of studies have been made on distance education. Along with recent, rapid technological advancements in networked computing, many technical problems such as distribution equity, storage capacity and flexibility to meet the needs of learners were cleared up to a significant extent (Divitini, Haugalokken, & Morken, 2005; Laurillard, 1995). However, by its very nature of distance education, even with implementation of the most updated two-way interactive conferencing technology, new problems of motivation and interaction have emerged as critical issues in practice as well as the research field. Although a variety of solutions had already been examined and developed to increase learner motivation and decrease social isolation among participants, those problems remained controversial and demand more research efforts. There has been a long history of intercultural exchange between Taiwan and Japan in various social events at all levels. Due to the commonly recognizable writing systems and similarities in the development of social values, intercultural collaboration has become more and more frequent in recent decades. Along with the development of emerging technology and

its applications in educational systems, National Taiwan University (NTU) in Taiwan and Kyoto University (KU) in Japan decided to launch a collaborative distance education project in order to extend and improve mutual academic exchange between the two universities in Feb, 2005. Before the exchange of the formal courses, some exhibitions with trail connection were held first as a warm up.

As Kyoto University opened one of its courses via real-time video-conferencing to National Taiwan University as a demonstration, it allowed the faculty and students of NTU to experience the classroom atmosphere as well as the instructor’s tempo of teaching to the class of KU. About 70 teachers and students attended the open class demonstration, and had a direct discussion with the instructor of Kyoto University. Feedbacks collected from the participants showed that they thought the best part of international distance education would be that it provides the opportunity for participants to see how different approaches worked with foreign cultures over common subject matter.

This practice had motivated them to ponder on the learning issues more profoundly and also inspired them to think of possible new curriculum design. And besides, the faculties who participated also reflected through the discussion that although classroom management is essential to student learning (Emmer & Stough, 2001; Lin, Yueh, Murakami, Minoh, 2009) in any instructional context like traditional face-to-face meetings, it is even more critical to the success of distance education.

Instructors of international distance education must have an overall understanding of students in advance to better manage the classroom and content. Otherwise, the extremely interlaced network may become a great disturbance in teaching and learning in distance education. Taking the feedbacks from the pilot demonstration into consideration, the two universities have established the NTU-KU International Distance Education Collaboration Project and defined the format as course exchange with mutual benefit and thereafter started running distance courses in fall of 2005. Within the framework of the project, the effective pedagogic design from the curriculum to learning activities was infused and introduced both to instructors and students. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore and examine the role of learning activities in the international distance education context with the intention of improving students’ motivation and enhancing their intercultural interactions through working together in distance courses.

Implementing a Collaborative Teaching Approach in Distance Courses Since it had been the first experience of distance education for most students enrolled in these courses, it is very critical to adopt sound strategies that can facilitate instructors’ teaching and students’ learning to ensure the success of the implementation. In this program, instructors of each subject matter from both universities had to work in teams to plan and co-teach the courses. Rather than one-way delivery system of the instruction, the curricula

plan, instructional design and methods, as well as assessment criteria were all collaboratively decided and developed by instructors of both sides beforehand based on thorough discussion and negotiation. One key issue that needed to be worked out is the class meeting times due to the differences in semester schedule of both universities. With full supports from administrative and information technology teams of both universities, collaborating faculties then formed a team to co-teach the courses during video-conference meetings and tutor students at their own sites. However, the learning assessment was conducted respectively at both sites. This collaboration model was implemented with concerns for maintaining the respective autonomy, and managing the meaningful exchange between the two universities at the same time.

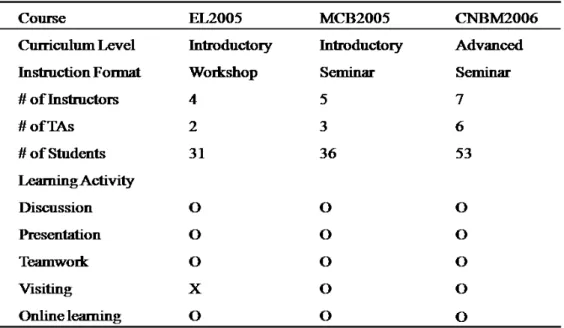

In the first academic year of this project, there had been three exchanged courses including “Molecular and Cell Biology, MCB” led by Kyoto University, and “Introduction to e-Learning, EL” and “Cellular Network of Biological Molecules, CNBM”, both led by National Taiwan University. More than 10 professors in total joined the lectures, and greater than 100 students (MCB: 36; EL: 31; CNBM: 53) participated in the three courses that this case study explored. For the classroom atmosphere, all three courses adopted the student-centered approach but with different designs of the instructions. The MCB and CNBM courses were structured in a seminar-like format; the instructors gave short lectures and let the students take charge of

leading discussions in the seminar. The EL course, on the other hand, was more in a workshop-like format with instructors’ lectures and invited highlighted speeches. Faculties of both universities would also facilitate students learning in both the synchronous video-conference class meetings as well as on the Internet asynchronously. However, despite somewhat differences in the course formats, cross-university discussions and teamwork activities were agreed to remain as the core value and were highly emphasized in all the three courses.

Furthermore, faculties of the three courses have all adopted the NTU Learning Management System – CEIBA, to support classroom teaching and learning and integrated some online activities such as theme-based discussion, information sharing, project group teamwork, and so on with the system. CEIBA is a learning management system designed with theoretical bases of instructional design principles that aimed at offering faculty instructional support and in turn would facilitate students’ learning (Yueh & Hsu, 2008). Moreover, referring to the researches that argued the importance of cultural issues on technology integration in education especially in the context of distance learning (i.e., Chen, Mashhadi, Ang, Harkrider, 1999; Rogers, Hsueh, & Allen, 2006), all faculty of the courses has also considered the cultural differences in course planning and intended to promote the experience of cultural exchange through learning in the international distance courses.

Designing of Learning Activities in Supporting Distance Learning

Activities have been proved to be a highly effective means that could help by introducing students and teachers to a new set of cultural tools in successfully structuring their interactions (Cole, 1996). Besides, Lee and Im (2006) also reported that students with more e-learning experiences had tendencies of studying more. In particular, some researches (i.e., Kalfadellis, 2005; Saito & Ishizuka, 2005; Teng, 2008) indicated the importance in designing of learner-centered learning activities and integrating experiential learning in instructional activities would help to facilitate cross-cultural learning. It is obvious that to provide the link between learning activities inside and outside the classroom, as well as in the online learning environment are important to ensure students’ meaningful learning especially at a distance. This idea was actually embedded in the instructional design of the three courses in this case study. In this section, learning which activities were adopted in the three courses and how they were designed and infused to advance the implementation, interaction, and cultural exchanges in the international distance courses will be presented.

Case Profile

The three courses, “Molecular and Cell Biology, MCB”, “Introduction to e-Learning, EL”, and “Cellular Network of Biological Molecules, CNBM”, were offered to both undergraduate and graduate students in fall of 2005 and spring of 2006. Conflicts of the

academic schedule due to different school system between the two countries were solved by adjustment of both sides before classes started in each semester. English was chosen to be used as the official language in the class teachings, discussions, and online communications. And in general, students of both universities all possessed moderate, good to excellent English proficiencies.

The courses were delivered via two-way real-time video conferencing system every week by connecting the two sites of NTU and KU. Instructors and students can communicate in class synchronously without any delays. Meanwhile, all courses used the learning management system CEIBA and all course materials were aggregated onto the system for students of the two universities to access. Moreover, asynchronous communication tools provided by CEIBA including announcement, forums, instant chat, and votes were freely adopted by instructors for managing class activities (Yueh & Hsu, 2008) and facilitating students’ active participations in distance learning.

The content of the three courses was set at the introductory level while taking the undergraduate enrollment and language issues into considerations. Instructors strongly encouraged students to actively participate in class discussions both synchronously and asynchronously, making oral presentations in class, and explore the issues with all kinds of online learning activities (Sheng & Takeyasu, 2005, 2006; Yueh & Minoh, 2005).

evaluation was conducted by distributing an evaluation form (Yueh, 2005) to collect feedback and suggestions from instructors and students of each course. Based on the analysis, students reflected on five major activities including class discussions, oral presentations, teamwork, academic mutual visits, and online learning to be the most impressive and meaningful learning events. This result has not only met the design purpose of the courses but also had important implications on cultural exchange in the international distance education.

Class Discussions

Interactions and communications are very important to the success of classroom teaching, yet are somewhat difficult to manage in real practice of distance education (Yueh, 2000). It is often that many distance educators would hesitate to lead discussions in class, ignore interactions between instructors and students, or even avoid questions due to the concern of possible technical troubles that may distract the ongoing instruction (Linn, 1996). However, in the NTU-KU case, students were impressed by the purposeful engagement with the class discussion activities especially designed for the class seminars, cross-bordered peer discussions, and the instructors’ answers and feedback to their questions. Despite that those discussion activities usually would account as some grade points, students felt encouraged to take every chance to express themselves in class, and even take charge of leading the discussions.

Oral Presentations

All three courses required the students to make oral presentations with different formats. The two bio-science courses asked the students of each sites to form groups to prepare for the academic presentation of reference reviews in a seminar-like format. They needed to prepare important issues for the discussion and lead the class discussion as a part of the presentation. Every instructor of the two courses was responsible for supervising one or two groups individually and to facilitate the in class discussion processes. On the other hand, as the “Introduction to E-Learning”, the course took the project-based learning approach. Project work activities was implemented and students in groups were required to give oral presentations to the class at the end of the semester in which they reported their ideas, approaches, progresses, and products of the project works. And the instructors also acted as facilitators to help students in group learning processes.

Teamwork

As described in the previous section, students of the three courses all needed to work in teams to complete assignments. For the two bio-science courses, students of the same universities worked together in the study groups. And for the E-Learning course, students of both sites were assigned to work in autonomous groups of cross-bordered members to work on their group learning tasks. Through the online team work, students of different universities developed their project-based

learning experiences and finally completed their projects.

Academic Visits

It is not common for distance educators to visit different sites that receives the instruction via telecommunication or web technology systems. However, research showed that students would appreciate the opportunity to have instructors coming into the classroom in person and have direct face-to-face interaction. It would even improve quality of distance education indirectly (Yueh, 2000). In the fall 2005, a visiting trip was arranged by the KU instructors of the Molecular and Cell Biology course. Some students volunteered to come with the KU instructor to visit and meet the instructors and the students of NTU. With a good experience reported by students of MCB course in the fall of 2005, the NTU instructors consequently organized another visiting trip in CNBM course in spring of 2006. During this trip, NTU students went to Japan and visited the instructors and the students of KU in person. Several interactive events were also arranged during both trips such as attending academic seminars, visiting laboratories, and going to local tours of sight seeing. Those activities were managed by students at the local site in which they actively planned and guided the tours to provide their friends with cultural exchange experiences. In addition, these visits sort of moved the distance education to more like a

blended format, and not only faculty members could identify the students at the distant site easier, but was also observed that the students’ active interactions in class and online had increased because they actually felt more closer to each other and more familiar with the original instructors at a distant after the visits. And these visiting activities turned out to be the most impressive activities for the students who had participated in any format in the two courses.

Online Learning

Online learning activities have been viewed and designed as the mediated mechanism that linked students together in many distance courses. In the NTU-KU case, the instructors have managed to perform some learning activities on the course management and learning system, CEIBA (See Figure 1). Each class had its course website (Sheng & Takeyasu, 2005, 2006; Yueh & Minoh, 2005) that allowed instructors to post announcements, publish course materials, collect assignments, and communicate with students on forums, all led to facilitate students’ online learning as a supplement to their weekly class meetings via video-conferencing. Since the CEIBA system supports languages such as English, Chinese and Japanese, students could easily choose the interface between English and Chinese and make their input using the three languages as they wish.

Figure 1. The course websites on NTU CEIBA. From left to right: EL2005-Introduction to E-Learning, MCB2005- Molecular and Cell Biology, and CNBM2006- Cellular Network of Biological Molecules.

In addition to the commonly adopted online learning designs, the E-Learning course had a special online activity that required the students to maintain their own blogs. Students could document their learning of domain knowledge and self-reflect their learning in the

class or relevant experiences. With the process, it was expected that students will be able to develop their own learning experience and also exchange their experiences with other students of the two universities. Table 1 summarizes profile of this NTU-KU case.

Learning and Cultural Experiences in the International Distance Courses One main purpose of the NTU-KU international distance course collaborative project was to provide students with the opportunities to develop an international exchange experience and global perspectives. The Culture is emerged as the crucial issue in this kind of distance education practice as observed in the study. While this study of collected data from course documents, websites, instructors and students interviews, as well as results of course evaluations, researchers of this study developed an analytic mechanism to looking into important factors that affect the implementation of this international distance education project. Based on the analytic mechanism, following are some reflections and discussions on culture and learning dynamics with dominant and recessive intercultural interaction of the distance learning practice by researchers who were also instructors of some of the courses.

Attentions

According to the researchers’ observation and feedbacks collected from student questionnaires, the international distance course itself had drawn the most attention from the students. Over ninety percent of the students decided to register these courses for the reasons of having the opportunities to learn from foreign scholars with different perspectives; having the novel experiences to learn with foreign students; and having chances to be in a course taught in English within which an environment where

they can freely communicate with others in English.

Motivation

The international distance courses required students to communicate in English, work in groups, share their opinions, and reflect on the authentic issues in the classes and on the websites. These learning activities could be viewed as the dominant intercultural interaction, which were also the artifacts of the course culture that embedded in the practice. Students were motivated by these dominant intercultural learning activities that stimulated their awareness of their roles and actions in the classes. They were aware and tended to monitor their own performances, with the intention to show and share their learning progresses with others and had demonstrated it as a continuous effort. In particular, through the learning activities in the courses, students autonomously paid attention to and especially valued the responses and opinions from their foreign classmates. It is the novelty of the learning experience first attracted them, and kept them motivated with active participations in learning throughout the whole semester.

Authentic and Natural Interactions

It is worth noting that the classes had developed an unspoken set of core values naturally that guided both what students had done in the learning environment and how they made sense of each other’s actions. Although students first needed to experience the stage of accommodation, once they strode across this

point, they perceived the authority of their own learning, and became engaged in active learning without any pushing of instructors or tutors. The reason for that could be students got used to the norms of culture they developed collaboratively, and with that they knew what to expect and respond in the interaction process so that they could perform naturally even in intercultural exchange activities. The culture students developed together was made by the students who were in distance courses. It was reflected in how they structured their learning, what content they discussed with one another, and what kind of communication tools they selected to perform the interactions.

Self Presentation with Non-native Language As discussed earlier, to be in a course taught in English was one of the key factors that drove students to the courses. However, since English is not native language to all students at NTU and KU, it was a challenge for them to speak up and discuss in English, and let alone to make a formal presentation in class. Most students reflected that this was their very first presentation in English, which was more challenging than they expected, but they viewed it as a precious learning experience they could get appraisals especially from the classmates at local and distance. One interesting finding was that rather than assigning group representatives to make the presentation, almost every student volunteered to give the presentation while they argued the difficulty of this task earlier. This happened too in their writing and communication on web forums and

on their learning blogs. Every student expressed their ideas in English no matter how difficult they thought it would be before actually doing it. The reason for that was that they wanted to be understood and to communicate effectively with their peers in foreign countries. It clearly became a cultural issue and shaped the environment within which they developed their identities.

Collaborative Knowledge Construction Teamwork has been emphasized in all the courses in this NTU-KU case. Students not only were expected to work in groups for completion of their assignments but also to construct a workable mechanism with in which they would exchange information and develop knowledge together. In this kind of knowledge construction activities, it was actually challenging for students to balance learning in class discussion and in online environment, especially when the English was not their native language. To complete the group assignments successful, students often utilized the mechanisms of the online support provided by instructors. They discussed subject matter, shared information, worked on group projects online with the learning management system. Also they consulted instructors and tutors, supported one another by giving feedback and comments or providing important information, which made the class become a big learning community without barriers. With all the efforts, students learned to share, clarify, and build knowledge collaboratively in their groups as well as in the whole classes. These

collaborative efforts of knowledge construction were evidenced by the project results, classroom presentations, and feedback on their returned questionnaires.

Life Experience and Cultural Exchange As an international distance course with students from two countries, it was also found that many students chose to talk about cultural events as the icebreaking strategies while getting to know one another online. For example, when the Japanese students introduced several historical spots in their city at first, the Taiwanese students then shared the information of the famous snacks in Taipei. Students of both sites expressed high interests toward this kind of cultural issues. Sometimes one person’s comment to the other’s entry could draw lots of audience and finally became a thread of series talk among peers in the community. Through this kind of free conversations, they exchanged life stories, cultural information, learning experiences, and made friends with one another.

Effects of Online Support

The main purpose of providing online support in the international distance courses was to make knowledge sharing and cultural interaction visibly important to the students. Online support was viewed as not only complementary to the class meetings but also the scaffolding structure to guide students’ learning and teachers’ instruction with the possibility to extend the interaction outside the classroom. To better support the culture and

learning activities in these distance courses, the mechanisms of online forums and tutors were introduced as supports which extended the classroom interaction to a certain degree. Teaching assistants (TAs) in these distance courses played the mediated role of resourceful learning partners in online learning environment. They monitored the students in learning, participated in students’ discussions, provided in-time advices to minor problems, and kept the instructors posted with the status of students’ learning. Online forums helped the class continue the discussion of issues and questions raised in the class meetings, which helped students to better organize their thoughts and keep tracked with the threads of discussion. Meanwhile, corresponding resources that were suggested by students and tutors during discussion were extracted and posted onto the Information-Sharing repository of CEIBA for students to follow up.

Conclusions

The NTU-KU international distance education collaboration project between the two universities in this study was designed to be a long-term project that would continue for some years. Throughout the implementation in the first year, three courses had been developed and delivered with a success in terms of satisfaction expressed by students and their performance. It is a quite novel experience for instructors to co-teach at distance and across countries. With many kinds of learning tools and internet technology infusions, it was also viewed as an educational experiment to try out the technology affordance in supporting

international distance courses. Students were encouraged to try things out through various learning activities in this course with different online supports designed to foster intercultural exchange. At the end of each semester, from the observation and faculties’ reflections, it was found that these learning activities had shaped a specific culture in these courses including the two sites at distance in two countries.

As the purpose of this study is to explore and examine the role of learning activities in the international distance education context, and to investigate whether it would help improve students’ motivation and enhance their intercultural interactions. Results of this study not only proved well designed activities did help increase the students’ motivations and interactions in the context, it actually demonstrated a case that fully contextualized a learning experience with cross-culture interaction and technology integration in international distance courses. It echoed Rogers, Hsueh, and Allen’s (2006) call for specific insights for designing more effective instruction across different cultures in distance learning, and proved it to be a successful experience. As the project is still undergoing, there are opportunities to continue the study to deepen our understanding of cultural exchange and strategies for advancing distance learning especially within cross-bordered context. It is suggested that future researchers or educational practitioners may put efforts into modification and adjustment of instructional strategies, improvement of communication tools, and designing of effective curriculums and learning activities that would better motivate students’ intercultural collaboration to advance students’ learning experiences in international distance courses.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this paper is supported by NTU-KU distance learning collaboration project. The authors would like to thank all the supporting staff and participating students of Kyoto University and National Taiwan University for their great help and efforts to make these distance courses successful.

References

Chen, A., Mashhadi, A., Ang, D., & Harkrider, N. (1999). Cultural issues in the design of technology-enhanced learning systems. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30, 217-230.

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Divitini, M., Haugalokken, O., & Morken, E.M., (2005). Blog to support learning in the field: lessons learned from a fiasco, Proceedings of the Fifth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, ICALT, 219-221.

Emmer, E.T., & Stough, L.M. (2001). Classroom management: A critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educational Psychologist, 36(2), 103-112.

Kalfadellis, P. (2005). Integrating experiential learning in the teaching of cross-cultural communication. Journal of New Business Ideas and Trends, 3(1), 37-45.

Laurillard, D. (1995). Multimedia and the changing experience of the learner. British Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3),

179-189.

Lee, O. & Im, Y. (2006). How do students and faculty of higher education perceive E-learning in Korea? Asia-Pacific Cybereducation Journal, 2(2), Retrieved 09/10/08 from http://www.acecjournal.org/ current_issue_ current_issue.php.

Lin, W-J., Yueh, H-P., Murakami, M., & Minoh, M. (2009). Exploring students’ communication and project-based learning experience in an international distance course. International Journal of Digital Learning Technology, 1(3), 162-177. Linn, M. (1996), Cognition and distance

learning, Journal of The American Society for Information Science, 47(11), 826-842. Rogers, P.C., Hsueh, S., & Allen, S. (2006).

American and Chinese cultural differences and their implications for distance learning. Asia-Pacific Cybereducation Journal, 2(2), Retrieved 09/10/08 from http://www.acecjou rnal.org/current_issue_current_issue.php. Saito, R., & Ishizuka, N. (2005). Practice of

online chat communication between two countries and across different curricula. Journal of Multimedia Aided Education Research, 2(1), 151-158.

Sheng, T. & Takeyasu, T. (2005). Molecular and Cell Biology website. Retrieved 09/10/06 from http://ceiba.ntu.edu.tw/941MCB2005Fall Sheng, T. & Takeyasu, T. (2006). Cellular Network of Biological Molecules website. Retrieved 09/10/06 fromhttp://ceiba.ntu.edu.tw /942sig-naling

Teng, L.Y.W. (2008). Understanding cross-bordered collaboration through an

online intercultural project. Journal of Scientific and Technological Studies, 42(1), 33-48.

Yueh, H-P. (2000). Classroom management in real-time broadcasting distance education. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 3(2), 63-74.

Yueh, H-P. (2005). The evaluation form of distance courses. Taipei: National Taiwan University.

Yueh, H-P. & Hsu, S. (2008) Designing an LMS to Support Instruction: The Case of National Taiwan University. Communications of the ACM, 51(4), 59-63.

Yueh, H-P. & Minoh, M. (2005) Introduction to e-Learning: Course website. Retrieved 09/10/ 06 fromhttp://ceiba.ntu.edu.tw/941elearning

The Authors

Wei-Jane Lin is a research fellow of Academic Center for Computing & Media Studies, and Ph.D. Candidate with the Department of Intelligence Science & Technology, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

E-mail: lin@mm.media.kyoto-u.ac.jp

Hsiu-Ping Yueh, is corresponding author and Associate Professor of the Department of Bio-Industry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. E-mail: yueh@ntu.edu.tw

Michihiko Minoh is the Director and Professor of Academic Center for Computing & Media Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. E-mail: minoh@media.kyoto-u.ac.jp