Running Head: IMPROVING INTERACTION AND FEEDBACK

Improving Interaction and Feedback with Computer Mediated Communication in Asian EFL Composition Classes: A Case Study

Michael C. Cheng National Chengchi University

Abstract

This paper explores some of the problems associated with teaching writing in Asian EFL contexts. Asian university students are often shy and unresponsive in class. This passivity is especially problematic when writing instructors attempt to introduce a process writing approach that utilizes peer revision along with instructor feedback to their classes. A second problem is that students may feel that they are unqualified or that it is not their place to give peer feedback. Large class sizes also create a heavy workload for writing instructors, who may find it difficult to schedule adequate conference time with their students. Finally, students may not adequately revise their papers after receiving feedback. Introducing synchronous or asynchronous forms of computer mediated communication (CMC) can alleviate these problems. Examination of a case study in which CMC in the form of email was introducing into a university level writing class illustrates the immediate and positive impact a common and simple tool like email can have on student motivation, participation, and interaction.

Improving Interaction and Feedback with Computer Mediated Communication in Asian EFL Composition Classes: A Case Study

Introduction

Instructors of EFL writing classes in Asian contexts can face a number of discouraging hurdles. The students in writing classes often interact with their instructors and peers with great passivity. They can also be overly dependent on the instructor for feedback, but then only make superficial revisions to their essays after receiving written feedback from their instructor. These problems can be compounded by the crushing workload that accompanies teaching large classes of EFL writers, making it difficult to schedule conferences in order to elaborate on written feedback for example. Integrating computer mediated communication into a writing class can mitigate the problem of incomplete and underutilized feedback by changing the interpersonal dynamics of the class, allowing for new forms of teacher-student interaction and peer interaction, as well as increased individual autonomy. In addition, other benefits include creating an environment conducive to language learning (Kung, 2004) by increasing student participation (Warschauer, 1996) and improving motivation (Warschauer, 1996b; Alias & Hussin, 2002) as well as other factors. This paper will also examine a case in which introducing CMC into a university level writing class led to increased student

participation, motivation, and may have improved student comprehension. Problems in Writing Class

Passive students. Lack of response in writing classes can be the frustrating norm in Asia. Teachers in Japan (Snell, 1999), Singapore (Kannan & Macknish, 2000), Hong Kong

(Tinker-Sachs, Candlin, Rose & Shum, 2000), Malaysia (Alias & Hussin, 2002), Korea (Kim & Kim, 2005; Lim & Griffith, 2003), Taiwan (Penzenstadler, 1999), and Vietnam (Cam Le, 2005) have all commented on the quietness, shyness, or passivity of students learning English. Generally, Asian students are unlikely to speak out when the instructor poses a question to the entire class unless called upon directly. Students also rarely express opinions or even ask questions in class.

This passivity may be due in part to a lack of motivation. Although Lim and Griffith (2003) attribute the passivity of their Korean students to anxiety about speaking in English, rather than a disinterest in learning, the Hong Kong secondary students in the study referred to above are characterized as unmotivated, and twenty percent of the university students in Alias and Hussin's (2002) Malaysian study did not consider writing to be enjoyable when initially surveyed. In fact, students in general may consider writing to be the least enjoyable way to learn English (Brunton, 2005; Barkhuizen, 1998; Spratt, 2001).

Providing feedback. Student attitudes toward instructor feedback can also be a source of frustration. First, students may believe that only feedback from their instructor is acceptable, so when given a choice, students will choose feedback from their instructor over feedback from peers (Zhang, 1999). This could be a consequence of being "distrustful" of feedback from peers (Kim & Kim, 2005), or it may be because they feel that it is not their role to act as the teacher in the classroom (Sengupta, 1998; DiGiovanni & Nagaswami, 2001). Student concerns about peer evaluation do have validity as Brunton's (2005) survey of a number of studies shows that the effectiveness of peer evaluation is quite variable, although if training is provided, peer collaboration can be positive.

Secondly, once the instructor determines to provide feedback, the logistics can be daunting. If the instructor decides to provide feedback via face-to-face conferences to supplement written feedback, it may be inconvenient to schedule conferences with many of the students. Students may also forget many of the suggestions that are elaborated on in the conference, rendering the time spent ineffective. If feedback is only provided in written form, it is unclear how much students will reflect on the suggestions before making revisions since students writing in a foreign language tend to only make surface changes to their writing after completing their first draft (New, 1999). In Kannan and Macknish's (2000) study of tertiary level students in Singapore, the students claimed to be receptive to online feedback of their writing, but they never made efforts to seek clarification on the feedback, so it is unclear whether the feedback actually aided in their learning. In a non-credit ESL program preparing students for academic work in the U.S., student revisions often consisted of merely copying the corrections that had been written on their first drafts (Fregeau, 1999). Lower intermediate level university students in Japan, coped with feedback by deleting the sentences that were marked ungrammatical as long as the deletions did not interfere with the meaning of their essays (Kubota, 2001). Muncie (2000) believes that teacher feedback leads to automated acceptance of the teacher suggestions with students giving little critical evaluation to the instructor comments. Students believe that as their evaluator has given advice, they need to follow it in order to maximize the grade they receive on the assignment. Student reaction to instructor feedback can be summarized by Sengupta's (2000) statement that "studies have consistently found that students revise at a superficial level, failing to make any changes in meaning (p. 98)."

Given the large writing classes that are the norm in many Asian secondary and tertiary level educational institutions, it is easy to see how teachers can become dispirited. Once the instructor is done marking essays for grammatical errors with additional comments regarding the overall content of the essay, the students may invest little time in revision, settling to find the simplest solutions to surface errors.

The Benefits of Computer Mediated Communication as an Interaction Tool

One tool that can be made better use of in university level writing programs is computer mediated communication (CMC). Computer mediated communication can occur

synchronously through the use of instant messaging programs, or asynchronously through email. CMC also includes the construction of web page where students can post their work, allowing their peers to peruse and comment on their essays.

Integrating CMC into a class can bring numerous advantageous to second language writing classes by changing the interpersonal dynamics of teacher-student and student-student interactions. These changes can ease the feedback process for writing instructors and

facilitate improved peer feedback. CMC has also been shown to increase participation of students in class discussions (Warschauer, 1996). Positive associations that students have with computers (Warschauer, 1996b) and increased opportunities for instructors to interact with students can lead to improving the motivation of students (Huett, 2004). Other

advantages include placing students in a situation where they tend to interact with greater syntactic complexity (Warschauer, 2001), providing students opportunities for authentic communication (Gonglewski, Meloni & Brant, 2001), and using the target language exclusively, which can all create an environment conducive to language learning (Kung, 2004).

What is computer mediated communication? Computers mediated communication (CMC) is a step beyond the traditional use of computers in the language learning classroom

and has become widespread in the last fifteen years (Kern & Warschauer, 2000). CMC, also called network based language teaching (NBLT) focuses on "human-to-human

communication" while traditional computer assisted language learning (CALL) is often

"associated with self-contained, programmed applications such as tutorials, drills, simulations, instructional games, tests and so on" (Kern & Warschauer, 2000, para. 2). In CMC, a

language class can be connected together by "either local or global networks" (Kern & Warschauer, 2000, para. 2) to communicate synchronously or asynchronously. Instant messaging programs are the most common software used for synchronous communication. Instant messaging allows a class to interact through written messages or through video or audio conferences. Asynchronous communication occurs when email is used or web pages are constructed. The different forms of CMC allow a teacher and the students many options in terms of the number of people to communicate with and the amount of material to

communicate. Communication can be one-to-one, from one person to a specific list of people, or from one person to anyone with internet access. The message that is communicated can range from a few words to hundreds of linked hypertext pages on a website (Kern & Warschauer, 2000).

Benefits to teacher-students interaction. Utilizing CMC as a form of interaction can bring immediate benefits to an EFL writing class. First, an alternative form of interaction between teacher and students is established. The teacher and student can arrange to meet at an appointed time for a synchronous discussion, eliminating the need for face-to-face

conferences with all students (Belisle, 1996). Conducting synchronous discussions with instant messaging software allows for written chats, live video conferences, or a combination of both. This opens the possibility of meeting outside of office hours, and can also save time by cutting out any travel time. CMC chats can also leave a written record of what was discussed, allowing the student to review the contents of the discussion immediately before and during the revision process.

CMC also enables more frequent exchanges between students and their instructor. Essays can be emailed to the instructor at any time, instead of waiting until the next class meeting to turn in an assignment. Likewise, the instructor is also able to provide feedback by emailing responses before the next scheduled class. This has the dubious benefit of possibly decreasing the turnover time between assignments; however, a definite benefit is that students may be able to interact with their instructor many times during a week while working on intermediate versions of their essays, and students are no longer reliant on having all their feedback lumped into one conference.

Another use of CMC is to post student work and instructor comments to a website or bulletin board. Again, teacher-student exchanges are no longer limited to class periods, students have access to feedback in a more timely fashion, and additionally, students are able to view the essays written by their classmates and the comments left by the instructor. Mak (1999 p. 105) "found that electronic conferencing encourages a movement from teacher-centred to learner-teacher-centred pedagogy, resulting in students constructing their knowledge together, heightening their language awareness, developing spontaneity in communicating in English and sharpening the precision of their word choice."

The effectiveness of online feedback. Matsumura and Hann (2004) have found that indirect online feedback was just as effective as face-to-face conferences in improving student writing. In their study with university students in Japan, students were able to choose their preferred feedback method. They could post their essays to an online class bulletin board and read comments from the instructor and fellow classmates, receive feedback in a direct face-to-face conference, read the essay of other students and extrapolate improvements

to their own papers, or combine any of the three previous alternatives as they saw fit. High computer anxiety students opted to use the direct conference alternative. Students that combined direct conferences with indirect comments on their posted essays were judged to have made the most improvement. Students who used only online feedback or direct conferences improved at equal levels, while students who received no feedback and only observed the essays of fellow students lagged behind in terms of improvement.

Writing models. Public access to draft essay that have been commented on leads to a second and third major advantage of using computer mediated communication in a writing class. The online essays and comments can be helpful in training students in both their writing and their awareness as peer reviewers. Online access to peer essays provides interim writing models that can give students examples of "achievable target texts" (Brunton, 2005, p. 13). Reading the writing of classmates during the revision process is also beneficial because it allows students to see how their fellow classmates "negotiate the lexical, syntactic and discourse levels" while revising their writing (Sengupta, 2000, p. 111). By having the essays of all students available online, the instructor can easily select example essays for all students to read. Passages no longer need to be written on the board, nor do photocopies of essays need to be made for all students to illustrate a point. Pertinent passages can be emailed to students before class, or these models can be viewed directly from the computer in class if a computer lab is available for class meetings.

Peer correction. In terms of peer correction, CMC has major advantages in training students to give effective peer feedback. When instructor and student comments are both posted to a single site as in the Matsumura and Hann study, students can compare the feedback from the instructor and students for similarities or differences. A scaffolding environment can also be created if the instructor comments on the student peer feedback to point out reasons for the differences in their commentary. To further the training of students in peer feedback, once the instructor has introduced students to peer feedback, written synchronous CMC can be used to monitor the effectiveness of the peer interactions if a computer lab is available for the class. Many students distrusted the advice from their peers (Kim & Kim, 2005), but felt more comfortable with online peer correction because they felt that the teacher was monitoring their feedback and would intervene if their partner's

suggestions were inappropriate, while in a face-to-face setting the instructor could only catch bits and pieces of conversations while moving from pair to pair (DiGiovanni & Nagaswami, 2001). DiGiovanni and Nagaswami also found that the majority of students in the American ESL class that they studied preferred CMC over face-to-face peer review because they could say things more truthfully than they would if they were speaking directly, they stayed more focused on the task, and they did not have to remember every bit of the conversation because they could print out comments after the class.

Muncie (2000) also believes that the instructor should not comment on preliminary drafts of an essay because students accept the instructor advice without reflecting on it. He believes that the first comments should be made by peers and finds that students are much more "discriminating in their incorporation of the feedback" (p. 50) from peers creating an environment in which the peers can collaborate on revising an essay, and where students can build autonomy in evaluating and reflecting on their own writing. Moreover, de Guerrero & Villamil (2000) build on this by showing that even stronger students benefit when paired with a weaker student while peer revising. They conclude that "scaffolding may be mutual rather than unidirectional (p. 51)."

As students become more autonomous and more effective at providing peer feedback, the feedback burden of the instructor may lighten. The instructor will no longer need to be

responsible for correcting every intermediate draft of an essay, but can still be confident that students are providing appropriate advice by monitoring their suggestions via CMC.

An environment conducive to language learning. In addition to providing alternative and effective ways for teachers to provide feedback to students, using CMC in class has a number of advantages that can create an environment conducive to language learning.

Participation. CMC can lead to both and increase of participation and more even participation. Warschauer (1996) showed that the students working in small discussion groups had a much more even level of participation when using computers for a synchronous discussion as opposed to discussing in a face-to-face format. Salaberry (2001) concludes that CMC slows down the rate of communication as compared to face-to-face communication, but can still increase participation as all students can be crafting responses simultaneously.

Chou's 1999 study and Warschauer's (2004) continuing research on this theme concluded that the benefits of synchronous online discussions included greater participation by quiet

students, and improved accuracy in student writing after online discussions. Asynchronous email communication was also lauded for improving interactions between the teacher and students and for creating a permanent log that students could refer to and learn from.

Motivation. Warschauer (1996b) showed that "all categories of students showed positive attitudes toward using computers" (p. 9) and that motivation for a class can be increased if the teacher integrates computer use into the "regular structures and goals of the course (p. 11)." Alias and Hussin (2002) also found that the twenty percent of students who were unmotivated about attending their writing course changed their perception toward writing after

participating in a number of web-based writing activities. Huett's (2004) paper summarizes research into the advantages of using email as a feedback tool. These advantages include greater interaction between teachers and students, which can contribute to increased

involvement and motivation on the part of students. Kupelian (2001) lists less anxiety, fewer inhibitions, better preparedness for face-to-face discussions, and improved attitudes toward the target culture as advantages to using asynchronous email discussions. However, problems may arise if emails are not returned promptly, a problem that can be mitigated by the use of synchronous chats for discussions. Kupelian notes additional benefits of chat mode include increasing reading speed and learning to think and compose at the same time. Honeycutt (2001, p. 26) sees differences in student attitude towards email and chat with students considering email to be "more serious and helpful than chats." Finally, motivation may be impacted by the assessment method of a course as Weasenforth, Meloni, and Biesenbach-Lucas (2000, p. 12) believe that "electronic group discussions are also an assessment alternative to more traditional assessment types in both graduate and ESL courses" because they "may appeal more to some students who do not do well with quizzes, tests, papers, and oral presentations."

Syntactic complexity. Warschauer (1996) showed that students used greater syntactic complexity while discussing via the computer, making CMC an advantageous tool for prewriting discussions as the computer mediated discussions could serve as a clear bridge between discussion and writing during the process of composition creation "by facilitating L2 interaction that is linguistically complex yet informal and communicative" (Warschauer, 2001, Interaction section, para. 2). Park (n.d.) hypothesizes much the same after a literature review of the subject. Miyao (1997, p 190) saw that her students were "starting to learn both interaction skills and composing skills in English without inhibitions" after she incorporated email into her composition teaching techniques. She also noted that email facilitated the

prompt response to questions, and allowed the teacher to easily monitor the language used in student to student discussions. Sotillo (2000, p. 82) sees advantages in both asynchronous and synchronous CMC that can be exploited by experienced teachers with one clear advantage of asynchronous communication being that it allows students to write with greater "syntactic complexity."

Authentic communication. Gonglewski, Meloni and Brant (2001, Pedagogical Benefits of E-mail section) comment that "e-mail extends what one can do in the classroom, since it provides a venue for meeting and communicating in the foreign language outside of class." In addition, since students can "write e-mail from the comfort of their own room, from a public library or from a cyber-café" they may "increase the amount of time they can spend both composing and reading in the foreign language in a communicative context." Other advantages include "communicating with other speakers in authentic communicative situations" and the preservation of a permanent record of the students correspondences (Gonglewski, et. al. 2001). d'Eça (2003, Chat and EFL/ESL: Advantages section, para. 3) echoes these advantages as well as lauding how chat "encourages collaborative learning and team work and helps develop group skills." Kung's (2004) use of synchronous CMC caused her Taiwanese reading students to use the target language throughout the class and also to initiate and manage discourse throughout their chats.

A note on disadvantages. d'Eça (2003) does caution that there are disadvantages to computer mediated communication in the language learning classroom including the use of short message service (SMS) language and possible technological problems such as

insufficient bandwidth. Matsumura & Hann (2004) in their study of Japanese university students in EFL writing classes believe that some students may be disadvantaged because computer anxiety can affect a student's willingness to utilize computer mediated

communication. Sengupta (2001) also notes that teacher's who are less computer savvy may be overwhelmed by the preparation necessary to begin utilizing CMC in their classes.

In summary, this literature review shows the numerous advantages of integrating computer mediated communication into English classes; however, it should be noted that many of these studies were conducted in computer labs. For example, Warschauer's 1996 study took place in a dedicated computer lab with students using Daedalus InterChange software. In DiGiovanni and Nagaswami's (2001) study the students used Norton Textra Connect software on their networked computers. In the Matsumura and Hann study, the students and instructor interacted using the Caucus electronic bulletin board system. For an instructor who is less comfortable using computers, the necessity of learning a new software system can create a barrier to utilizing CMC in composition classes. However, in the

following case study, this barrier is circumvented by using common email software and personal computers as the means of introducing CMC into an English composition class.

A Case Study on Integrating CMC into a Face-to-Face Composition Class

In this case study, computer mediated communication was unexpectedly introduced into a university level writing class by necessity, rather than by design. The overwhelmingly positive response caused the instructor the continue experimenting with its use at periodic intervals during the semester, even when it was no longer necessary to do so. However, this case study examines only the first two class sessions that incorporated the use of CMC.

The subjects of this case study were 15 students enrolled in the second semester of a section of English Composition II at a national university in Taiwan. The semester began in

February 2004. This was the second semester of a year long course that met for two hours every week. All students had passed two previous years of writing classes (Freshman

Grammar and Guided Writing, English Composition I). In the first semester of the course the task was to teach the students to write persuasive essay. In addition, the issue of plagiarism and how to cite the sources was taught during the first semester. The class was taught in a traditional classroom. The creation of each new essay typically followed this process:

1. Student discussions and idea generation. Each student brought in background material on a subject of interest and discussed possible areas to focus on with a small group of classmates. Each student was expected to have a thesis statement and outline constructed by the end of class.

2. Writing. Students wrote the first draft of their essay for homework and turned their essays in the following week.

3. Peer evaluation. Students read at least one of the essays written by a classmate and commented on it.

4. Revision. The following week students would receive their essays back with feedback from their instructor. Common errors were discussed in class. Sample passages were distributed to the class, and students were asked to suggest ways of improving the targeted passages. Time was left for students to discuss their individual difficulties as needed, with extra time

available outside of class as required. Papers were revised for homework.

It was expected that essays would be generated using the same general process during the second semester that began in February 2004. However, personal issues kept the instructor from attending class at the beginning of the semester. It was then decided that an attempt would be made to run the class from the United States using email as the medium for computer mediated discussion.

First CMC Composition Class

The first CMC class was conducted using the following procedures. Students were sent emails informing them that class would be held at the regularly scheduled time, and to be at internet connected computers at the appointed time. Two student essays were also attached to this email, and the students were told to read and evaluate the essays and to be prepared to comment on them. The essays were chosen because although they were generally well written, they did contain organizational problems that would be worthwhile to point out. Moreover, they also contained some controversial ideas that could lead to a spirited discussion.

In addition, before the class began a number of target passages were selected from these two essays and other student essays. Some target passages included organizational problems, common grammatical errors, underdeveloped ideas, or some other mistake that would be valuable for the entire class to be made aware of. Other target passages included ideas that could be used as springboards for discussion. The key passages were numbered and pasted into a new document so they could be quickly cut and pasted into an email before it was sent to the students in the class. Twelve passages were selected because it was believed that this would be a reasonable amount of material to cover in a three-hour class.

At the beginning of the class, all students were asked to check in via email. Twelve of the fifteen students replied. One student missed the class because she had not checked her email, and the other student made a mistake on the time of the class and appeared late. The

last student actually attempted to participate but had trouble connecting to the internet and was unable to access her email.

After most students had checked in, the following two emails were sent to the class: Subject: First Question

"Many homosexual issues are discussed enthusiastically in recent decades. However, comparing with these late discussions, the

situation of homosexuality is much older. It has existed in our lives as long as the history in every different culture and country."

Look at the introduction. What should be in the introduction of an essay?

How does this essay measure up according to your own criteria for an introduction?

Subject: More directions for the First Question

This is the intro to ______'s essay. Think about what you should do in the introductory paragraph of an essay. How well does ______

accomplish this goal? Reply within 5 minutes to me alone. I will forward interesting replies to the entire class.

Replies from the students began trickling in and then the second set of questions to work on was sent out twelve minutes after the first set had been sent.

Subject: Second Question

This is the first line of the second paragraph. Work on it and email your answers back to me.

"First of all, I will introduce the east by talking about these two countries--Chinese and Japan. But the homosexuality referred here are mainly male."

These two sentences are jumpy. How can you bridge the ideas? Now continue by working on these following sentences in the second paragraph.

"Ji Yun, a scholar of Ching Dynasty, had recorded in his book that the boy prostitute began at the time of Huang Emperor (Sina, 2001)." Make this more concise.

"In the following dynasties, this climate has lasted for over four thousand years."

The next step was to provide feedback to the students on their answers to the first set of questions. This was done by selecting two student answers and forwarding them to the whole class. One of these forwarded replies was a strong answer, while the other answer was judged to be on the right track but needed to be strengthened. An evaluation of the answer was also added to each reply that was forwarded.

This series of sending out questions, receiving student replies, and forwarding selected replies with an added evaluation continued for the rest of the class. The class lasted for a total of 3:20 minutes, and 178 email messages were received by the instructor. There was only sufficient time to discuss five of the questions that had originally been prepared.

The class concluded with a request for feedback from the students about the experience, to which eleven students responded. Every student made a statement that included positive comments about the experience. Four students also included statements that were negative. Of these negative responses, one concerned feeling pressured by the need to write and respond quickly. Two negative responses were related to feeling tired from looking at the computer monitor. The final negative response concerned the slowness of her internet connection. Six of the eleven students, including one that included a negative statement, also requested that we use this method again.

Second CMC Composition Class

A second class was held via the internet two weeks after the first class. The focus of this second class was citation format. The structure of the class was similar to the first CMC class in that the instructor queried the students, collected their replies, and then forwarded selected replies to the entire class. Fourteen of the fifteen students registered for the class were able to attend this class. The class lasted two hours.

The first phase of the lesson had students go to Purdue University's Online Writing Lab to learn about APA style. They were then referred to specific sub-pages of this site and asked to summarize what they learned about citing sources in text, what to do when an idea used in a paper was acquired merely from talking to a person, and how to write a citation when a website gives no credit to the author of an article.

This was followed by an assignment in which the class was asked to go a page on CNN's website to find the necessary information to answer a question. Students were expected to answer the question with the proper in-text citation showing the source of the material used in their answers.

Subject: New assignment:

Look at how to do a citation if the author of an article is not given. Then go to this website:

http://www.cnn.com/2004/HEALTH/03/30/sleep.study.ap/index.html I'm wondering how much sleep a third grade child should get. How much do they tend to get now?

Find out the answers to my questions and write a short answer. Make sure you use proper in-text citations.

Examples of properly formatted in-text citations were then forwarded to the class. This class also ended with a request for feedback on whether the class helped the students to understand citation format better. In total, the students were asked to reply to six questions.

After the second CMC class, the feedback was also generally positive. Eight of the fifteen students responded with feedback with six students indicating that the class had been

helpful. Both non-positive responses asked for more direct correction of their citation mistakes. One non-positive response stated that the material had been covered previously. This last response is of interest because in actuality the material had been covered both in a previous class and as a homework assignment, yet the majority of the class stated that the CMC class session was beneficial since it helped them to understand the material better and also forced them to examine the online links to citation format websites that the instructor had provided.

Observations on the Classroom Results

The results of using computer mediated discussion in these two classes raise three issues that will be discussed in this section. The first issue is what type of participation could be observed after CMC was introduced into the class. The second issue is why student participation increased after CMC was introduced into the class. And the third issue is whether CMC was an effective tool for teaching students to accurately format citations? Student Participation

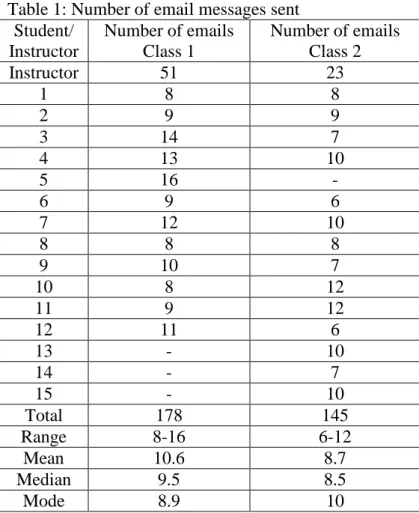

First CMC Composition Class. In terms of participation, this study supports Warshauer's (1996) conclusion that CMC encourages a more even pattern of participation among students. In the first CMC class, 178 email messages were exchanged. 127 of these messages were sent from students to their instructor. 51 messages were sent by the instructor to the entire class. Table 1: Number of email messages sent

Student/ Instructor Number of emails Class 1 Number of emails Class 2 Instructor 51 23 1 8 8 2 9 9 3 14 7 4 13 10 5 16 - 6 9 6 7 12 10 8 8 8 9 10 7 10 8 12 11 9 12 12 11 6 13 - 10 14 - 7 15 - 10 Total 178 145 Range 8-16 6-12 Mean 10.6 8.7 Median 9.5 8.5 Mode 8.9 10

Number of student responses ranged from 8 to 16 replies as can be seen in Table 1. Since the students were asked to make replies to five questions, every student participated

above the minimum amount necessary with a few students participating much more than required. The pace of participation did vary greatly with some students sending in their replies long after they were asked to move on to the next question. The students who replied 16 times and 13 times have tended to have consistently high participation rates in this and also other classes taught by the same instructor. However, a surprising result was that Student 3 had the second highest number of replies, 14. This student rarely spoke in the normal face-to-face classes unless asked to answer a question directly. Student 3 also tended to turn in papers late, and when they did arrive, the papers were underdeveloped. In this class, Student 3 was consistently one of the first to reply to questions from the instructor. In addition the answers were accurate and well written. Thus, Student 3's answers were often forwarded to the entire class as examples of a possible correct answer to the instructor's questions.

Second CMC Composition Class. In the second class, student responses ranged from 6 to 12 replies to the six questions that were asked. Thus every student participated at or above the minimal level necessary, with half of the students participating at or beyond 50% over the minimum requirement.

Reasons for High Participation

Class design. The high amount of participation shows that in essence every student answered every question that was asked by the instructor. This is a marked contrast to the student responses during the traditional face-to-face classroom sessions where usually only one or two students answered questions posed by the instructor. This high participation rate is likely due to the design of the class in which every student sent his or her answers directly to the instructor, instead of to the class in general. The instructor then filtered the answers that were forwarded to the entire class to reduce the amount of reading for the students. This is the main reason that an asynchronous form of communication was used to conduct the class. Instead of having to read every email written by their classmates, students only read the messages that were judged most beneficial in helping to improve their writing skill. The fact that each student only received replies from the instructor and never saw the replies of other students unless they were later forwarded to the entire class may have also made each student feel like he or she was having a personal one-to-one lesson with the instructor.

Decreased inhibitions. The content of peer comments is also of interest. Students tended to critique each other much more freely and directly than they did in the traditional face-to-face classes. One method to solicit comments that was used in the face-to-face-to-face-to-face classes was to use an opaque projector to project essays onto a screen for the class to read. In the face-to-face classes, students were reluctant to speak out when asked to comment on the quality of a classmate's essay. Students usually waited for the instructor to select a student to answer a question on a problem in the essay being viewed. In contrast, students were quick to respond with direct critiques of their classmate's essays when using asynchronous computer mediated discussions. Examples of student responses to the first question concerning the introduction of one of the essays follow.

The introductuon dosen't give us information about what kind of "things" the writer want to talk about. It's a little vague. In addition, I can't figure out what are the "late discussions" mean.

The intro should give at lease some background information of the issue being discussed. Ant to state clearly the thesis of this essay will be good. I see that ______ points out directly what she's going to

tell–history of homosexuality. However, citing one event as an example will be helpful. Such as the recently hot California issue. I think the introduction of _______'s is appropriate along with her subject. But it seems that it ddoesn't contain the main points of what she is going to say. I think an introduction should clearly point out what is going on on the following paragraphs in order to make peopele have a clear and broad vision of our essay.

There can be a number of reasons why students were more willing to critique their classmates. First of all, emails were sent directly to the instructor, instead of to the entire class. Students could have felt as if they were being individually tested by the instructor, making the need to pass the test of greater importance than the need refrain from criticizing or embarrassing a classmate. The students could also have been less inhibited since they did not have to face their classmates directly while making criticisms. Whether barriers to maintain proper social etiquette weaken when communicating through email was not within the scope of the study, but those who have participated in discussion boards are likely to have witnessed the breakout of "flame wars" on many occasions. Whether the use of synchronous communication would have also inhibited students from making direct criticisms of their classmates' essays is an issue that could be investigated in a further study.

Effectiveness in Teaching Citation Formatting

In terms of effectiveness, computer mediated communication may be a useful tool for teaching students to format citations properly. A comparison of student essays that were written before and after the citation formatting lesson shows improvement on the part of the students. Unfortunately, many mistakes still existed.

In this example, Student 4 made mistakes in both the format for the in-text citations and the works cited section at the end of the essay. However, Student 4 made much progress after the citation format lesson. The in-text citation format is correct, and the citations in the works cited section are greatly improved.

Student 4 pre-lesson:

Such phenomenon would prompt the boy be lack of the identity of his own gender (The Psychology of Homosexuality. Paul Cameron, Ph. D. 1999.).

The Psychology of Homosexuality. Paul Cameron, Ph. D. 1999. http://www.familyresearchinst.org/FRI_EduPamphlet6.html (March 10, 2004)

S. L. Arthur. Homosexuality and the Constitution. New York & London. Garland Publishing, Inc. 1997.

Student 4 post-lesson:

Under such circumstances, if their fathers are busy making money or strongly disgusting their boys, the boys will naturally be accepted and “dominated” by their mothers (Homosexuals, 1989).

Homosexuals. n. d.

http://www.sextoall.com.hk/sexeducation/homosexual/homosexual.htm

(April 5, 2004)

Grey, C. C.(1992). Psychoanalysis and social construction of gender and sexuality: Discussion. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 1(2): 74-78.

In this example by Student 1, the correct author of the article is not cited in the original essay, but this mistake is corrected in the revision done after the lesson.

Student 1 pre-lesson:

The dispute over same-sex marriage (SSM) is sweeping across US soon after San Francisco Mayer Gavin Newsom (Feb.11, 2004) said he wanted the city to try to find a way to issue marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples in defiance of state law.

Student 1 post-lesson:

The dispute over same-sex marriage (SSM) swept across US soon after San Francisco Mayer Gavin Newsom (Gordon, Feb.11, 2004) said he wanted the city to try to find a way to issue marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples in defiance of state law.

And in this final example, Student 2 had no in-text citations in the original essay and improperly formatted the works cited section. Student 2 improved after the lesson by now including in-text citations, although improperly formatted, and making some marginal improvements on the structure of the works cited section.

Student 2 pre-lesson: No in-text citations

http://www.cnn.com/2003/LAW/11/18/samesex.marriage.ruling/ Student 2 post-lesson:

Men talk in order to find a solution to the problem where as women talk for the sake of sharing and understanding, a solution is not always necessary. (John Gray, 1992)

Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus. John Gray. 1992

A lesson utilizing computer mediated communication can be helpful in improving student ability to properly format citations. However, one lesson still does not seem to be enough to allow students to fully grasp the entire citation process.

Discussion on Classroom Implications and Limitations

Computer mediated communication is a useful tool that can be beneficial in increasing the motivation and participation of students in university level advanced composition classes. It can also improve student comprehension of material by reinforcing lessons taught using traditional face-to-face classroom methods. There are difficulties caused by using email as

the tool for discussion though. These difficulties may be overcome by incorporating instant messaging or the use of a computer lab into the CMC teaching techniques used in the case study.

Motivation and participation. This case study shows that using CMC increased student motivation and participation in the class being studied. Student comments after the first CMC class show great enthusiasm for conducting the class via the internet. In addition, students that rarely made comments in class were quick to respond when questions were asked in the online class, a marked contrast to the passive responses that were typical of the first semester of the class. One student even seemed to be transformed by the CMC experience. This

student actively participated in the class for the first time during the CMC lessons, and for the rest of the semester, turned in better constructed essays in a timely manner. The very format of the online class also increased student participation since every student responded to every question posed by the instructor with some students responding multiple times. One final advantage is that by conducting the class with a computer mediated discussion format, the instructor was able to closely monitor student work and provide quick feedback when the students were practicing citation formatting. However, one drawback of this situation is that the high volume of emails that the instructor must process can be exhausting if the class is being held in real time.

Improved comprehension. Using CMC to teach also contributed to improved

comprehension of material that had been previously taught. It could be that CMC, being a novel way of presenting information, merely caused students to attend to the content of the lesson more diligently. But one real advantages of using CMC for teaching a highly detailed topic like citation format is that an online lesson creates a written log of all information that is exchanged between the instructor and the students. This allows students to scroll back and review information if an important point is missed, something impossible to do in a

conventional lecture situation. In addition, in the CMC class that was studied, the class design pushed each student to fully participate in each exercise presented in class. The instructor can then easily and quickly display student responses to the entire class. Having a written digital log of student responses allows the instructor to instantly highlight a mistake and display it for all students to examine. Students can quickly work on corrections and receive timely feedback from the instructor. In a traditional classroom, the time lag caused by recopying student writing samples onto the blackboard greatly slows the exchange of information and ideas.

Technological pitfalls. One disadvantage of how CMC was used in these classes was the time lag that can exist when sending email. These two classes were taught using email for asynchronous instead of one synchronous chat window. It was decided to not use

synchronous chat for a number of reasons.

First, using one synchronous chat window would mean that every student would have seen each of the 178 messages that were sent in the first class and the 145 messages sent in the second class. This was deemed both unnecessary and undesirable because the instructor's goal was to get every student to work through each of the exercises that were presented in class. If students were able to read each message as it was sent, the opportunity for each student to produce an independent answer would have been compromised. It is likely that student answers would be influenced by the answers of other students who were able to produce an answer more quickly.

In addition, having a constant stream of messages appearing on the computer screen could be distracting. Students would likely read each message since they needed to check on

whether the message had been sent by the instructor. Students with slower reading rates would also fall behind if the number of email messages that needed to be processed more than tripled from the 51 messages that were actually sent by the instructor to the 178 messages that were actually received by the instructor.

By using asynchronous communication, the instructor was able to easily organize and filter the emails, thus limiting the messages that students received to those messages that were most beneficial for learning. This decreased the reading load for the students, decreased distractions, and encouraged students to think independently as they completed the exercises presented in the class. Students were less likely to fall far behind and then skip ahead to catch up with the rest of the class, thus losing continuity by not working through all the problems in the proper progression. While the pace of participation did vary when asynchronous

communication was used, all students did participate by answering each of the questions posed by the instructor.

However, the choice of using email lead to the major problem encountered in these CMC classes–faulty email connections. Some students were unable to access their email accounts during the time of the class. There can also be a delay in the delivery of email. The time lag between opening a message, replying to a message and sending a message was also frustrating at times.

Combining synchronous and asynchronous communication. One way to overcome the time lag issue associated with email could be the use of a true synchronous discussion format instead of using asynchronous email to filter the discussion. This would necessitate using multiple instant messaging windows. One main window could be used by the whole class to view discussions since it is possible to for every member of an instant messaging group to connect to the same window. In addition, the instructor would still communicate with individual students through personal instant messaging windows. However, unlike email, students could not control their exposure to the messages on the main class window. The full messages would appear as soon as they were sent. When using email, students could open messages at their own pace, allowing each student to work through the progression of activities without feeling pressured to keep up with the fastest member of the class.

Another technological possibility would be to have an instructor controlled website for posting general information which is used concurrently with a linked discussion board. Blog software could fulfill this function. Questions by the instructor could be posted as individual blog entries. The students could reply by using the comment function of a blog to connect their responses directly to each question. The ideal configuration for integrating the many permutations of email, instant messaging, and websites is an issue worthy of further research.

Combining CMC and face-to-face interaction. Another issue to consider is the different advantages that spoken information and written information bring to the classroom. Spoken communication offers the advantage of speed, while written communication produces a permanent log that both students and the instructor can review in case of a misunderstanding. In the first CMC composition class, the instructor prepared twelve exercises to present to the class, but was only able to complete five exercises in a three-hour class. It is likely that many more exercises would have been completed in a face-to-face teaching situation. But although information can be communicated quickly if it is spoken, students may miss information, especially when they are listening to a difficult topic in a non-native language as was shown by how a majority of students responded that the CMC lesson on citation format was

beneficial to their understanding of the issue. Thus another area for further investigation is the integration of spoken face-to-face communication with synchronous computer mediated written communication. This can be accomplished by using the audio or video conferencing

function that is built into many instant messaging programs, or by holding composition class in a computer lab which will allow both face-to-face spoken communication and synchronous computer mediated written communication.

Areas for further research. Further research can also go into verifying the claims made in this paper in a more controlled environment. As the methodology of this class was forced upon it by necessity rather than design, it was not possible to survey student attitudes before the treatment. In addition, feedback from students after the CMC classes was not anonymous. However, the students had nothing to gain by claiming to enjoy the CMC class and asking for continued CMC use even after the instructor returned to Taiwan if they truly did not enjoy the technique.

Whether CMC does improve the ability of students to learn complex processes such as formatting citations properly can also be investigated further. This would entail developing a pretest and a posttest for test subjects and a control group to verify that students who were involved in a CMC learning environment assimilated the information better than students who were taught with traditional face-to-face teaching methods.

Student participation can also be studied. Participation levels and distribution were never charted before the treatment. In addition, it would be interesting to examine participation distribution in whole class face-to-face discussions after the treatment period to see if the students' full participation during CMC lessons decreased their inhibitions during future whole class face-to-face discussions.

Conclusions

When computer anxiety can still exist in our students (Matsumura & Hann, 2004) who were exposed to computers at much earlier ages than their instructors, it is likely that a much higher degree of computer anxiety exist among university faculty. Thus instructors may feel that setting up activities that are dependent on computer mediated communication is too time consuming or too confusing, even though many studies have shown that using computer mediated communication can have a positive effect on the learning and motivation of students in a writing class. However, this case study shows that even the simplest and most ubiquitous form of CMC–email–can have a dramatic effect on the attitudes and participation of students in a writing class. Using email to communicate with students during class time on a periodic basis can change the dynamics of a class by creating an environment conducive to learning where each student actively participates in all activities throughout the entire class. This environment also allows students to learn at their own pace and gives them the

References

Alias, N. & Hussin, S. (2002). E-learning in a writing course at Tenaga National University. TEFL Web Journal 1(3). Retrieved August 15, 2006 from

http://www.teflweb-j.org/v1n3/Alias_Hussin.htm

Barkhuizen, G. P. (1998). Discovering learners' perceptions of ESL classroom

teaching/learning activities in a South African context. TESOL Quarterly, 32(1), 85-108.

Belisle, R. (1996). E-mail activities in the ESL writing class. The Internet TESL Journal, 2(12). Retrieved October 13, 2006 from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Belisle-Email.html

Brunton, A. (2005). Process writing and communicative-task-based instruction: Many common features, but more common limitations? TESL-EJ, 9(3), A-2. Retrieved October 13, 2006 from http://www-writing.berkeley.edu/TESL-EJ/ej35/a2.pdf

Cam Le, N.T. (2005). From passive participant to active thinker. English Teaching Forum, 43(3), 2-9, 27.

Chou, C.C. (1999). From simple chat to virtual reality: formative evaluation of computer-mediated communication (CMC) systems for synchronous online learning. Retrieved January 25, 2005, from

http://www.lll.hawaii.edu/chou/conf/webnet99/webnet99chou.pdf

de Guerrero, M. C. M., & Villamil, O. S. (2000). Activating the ZPD: Mutual scaffolding in L2 peer revision. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 51-68.

d'Eça, T. A. (2003). The use of chat in EFL/ESL. TESL-EJ, 7(1), Int. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from http://www-writing.berkeley.edu/tesl-ej/ej25/int.html

DiGiovanni, E. & Nagaswami, G. (2001). Online peer review: an alternative to face-to-face? ELT Journal, 55(3), 263-272.

Fregeau, L. (1999). Preparing ESL students for college writing: Two case studies. The Internet TESL Journal, 5(10). Retrieved October 13, 2006 from

http://iteslj.org/Articles/Fregeau-CollegeWriting.html

Gonglewski, M., Meloni, C., & Brant, J. (2001). Using e-mail in foreign language teaching: Rationale and suggestions. The Internet TESL Journal, 7(3). Retrieved January 28, 2005, from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Meloni-Email.html

Honeycutt, L. (2001) Comparing email and synchronous conferencing in online peer response. Written Communication, 18, 26-60. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from

http://www.public.iastate.edu/~honeyl/research.html

Huett, J. (2004). Email as an educational feedback tool: Relative advantages and

implementation guidelines. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(6). Retrieved January 23, 2005, from

Kannan, J. & Macknish, C. (2000). Issues affecting on-line ESL learning: A Singapore case study. The Internet TESL Journal, 6(11). Retrieved October 13, 2006 from

http://iteslj.org/Articles/Kannan-OnlineESL.html

Kern, R. & Warschauer, M. (2000). Theory and practice of network-based language teaching. In M. Warschauer & R. Kern (Eds.), Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice. New York: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from http://www.gse.uci.edu/markw/nblt-intro.html

Kim, Y. & Kim, J. (2005). Teaching Korean university writing class: Balancing the process and the genre approach. Asian EFL Journal, 7(2), Article 5. Retrieved September 6, 2006 from http://www.asian-efl-journal.com/June_05_yk&jk.php

Kubota, M. (2001). Error correction strategies used by learners of Japanese when revising a writing task. System, 29(4), 467-480.

Kung, S.C. (2004). Synchronous electronic discussions in an EFL reading class. ELT Journal, 58(2), 164-173.

Kupelian, M. (2001). The use of e-mail in the L2 classroom: An overview. Second Language Learning & Teaching, 1. Retrieved January 23, 2005, from

http://www.usq.edu.au/opacs/sllt/1/Kupelian01.htm

Lim, H.Y. & Griffith, W.I. (2003). Successful classroom discussions with adult Korean ESL/EFL learners. The Internet TESL Journal, 9(5). Retrieved September 7, 2006 from

http://iteslj.org/Technique/Lim-AdultKoreanshtml

Mak, L.Y. (1999). What is the value of international e-mail groups for ESL learners?

Penetrating Discourse: Integrating theory with Practice in Second Language Teaching, 9th International Conference, Language centre, HKUST, Hong Kong (22-23 June, 1999), Language Centre, 2001, 105-118. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from

http://repository.ust.hk/dspace/handle/1783.1/1048

Matsumura, S. & Hann, G. (2004). Computer anxiety and students' preferred feedback methods in EFL writing. The Modern Language Journal, 88(3), 403-415.

Miyao, M. (1997). On-campus e-mail for communicative writing. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from http://www.kasei.ac.jp/library/kiyou/97/MIYAO.pdf

Muncie, J. (2000). Using written teacher feedback in EFL composition classes. ELT Journal, 54(1), 47-53.

New, E. (1999). Computer-aided writing in French as a foreign language: A qualitative and quantitative look at the process of revision. The Modern Language Journal, 83(1), 80-97.

Park, E. (n.d.). The effectiveness of electronic discussion in cooperative second language learning. Retrieved January 25, 2005, from

Penzenstadler, J. (1999). Literature teaching in Taiwan. ADE Bulletin, 123, 36-39.

Salaberry, M.R. (2001). The use of technology for second language learning and teaching: A retrospective. The Modern Language Journal, 85(1), 39-56.

Sengupta, S. (2001). Exchanging ideas with peers in network-based classrooms: An aid or a pain? Language Learning & Technology, 5(1), 103-134. Retrieved December 6, 2004, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol5num1/sengupta/default.html

Sengupta, S. (2000). An investigation into the effects of revision strategy instruction on L2 secondary school learners. System 28(1), 97-113.

Sengupta, S. (1998). Peer evaluation: 'I am not the teacher.' ELT Journal, 52(1), 19-28. Snell, J. (1999). Improving teacher-student interaction in the EFL classroom: An action

research report. The Internet TESL Journal, 5(4). Retrieved September 7, 2006 from

http://iteslj.org/Articles/Snell-Interaction.html

Sotillo, S. M. (2000). Discourse functions and syntactic complexity in synchronous and asynchronous communication. Language Learning & Technology, 4(1), 82-119. Retrieved January 28, 2005, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol4num1/sotillo/default.html

Spratt, M. (2001). The value of finding out what classroom activities students like. RELC Journal, 32(2), 80-103.

Tinker-Sachs, G., Candlin, C.N., Rose, K.R. & Shum, S. (2000). Learner behaviour and language acquisition project: Developing cooperative learning in the EFL/ESL secondary classroom. Perspectives (City University of Hong Kong), 12, 178-231. Retrieved September 14, 2006 from http://sunzi1.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/10/1000209.pdf

Warschauer, M. (2004). Technology and writing. In C. Davison and J. Cummins (Eds.), Handbook of English Language Teaching. Kluwer: Dordrecht, Netherlands. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from http://www.gse.uci.edu/markw/technology.pdf

Warschauer, M. (2001). Online communication. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 207-212). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from

http://www.gse.uci.edu/markw/oc.html

Warschauer, M. (1996). Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second language classroom. CALICO Journal, 13(2&3) 7-23. Retrieved January 20, 2005, from http://calico.org/journalarticles/Volume13/vol13-2and3/Warschauer.pdf Warschauer, Mark (1996b). Motivational aspects of using computers for writing and

communication. In Mark Warschauer (Ed.), Telecollaboration in foreign language learning: Proceedings of the Hawai‘i symposium. (Technical Report #12) (pp. 29–46). Honolulu, Hawai‘i: University of Hawai‘i, Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center. Retrieved January 28, 2005 from

Weasenforth, D., Meloni, C., & Biesenbach-Lucas, S. (2000). Impact of asynchronous electronic discussions on native and non-native students’ critical thinking. Retrieved January 24, 2005, from http://www2.cddc.vt.edu/lol2/papers/Beisenbach.pdf

Zhang, S. (1999). Thoughts on some recent evidence concerning the affective advantage of peer feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(3), 321-326.

Appendix 1 Student Feedback after CMC Composition Class 1 Table 2: Personal feedback on the class

Student Includes positive comment Includes positive comment Desires to use CMC again 1 X X 2 X X 3 X X 4 X X 5 6 X X 7 X X 8 X 9 X X X 10 X X 11 X X 12 X 13 14 15 Total 11 4 6 Student 1:

This is pretty special..and I think its easier to express ideas in words. However, to look at the monitor for such a long time is tiresome!

Student 2:

It was kind of fun but I actually felt more pressured than in class. In class, we could just say what we want to say out loud, but here we had to type it out. I think, on the other hand, when we write things down, we have paper proof, so that made us more cautious about what we were going to say.

I also felt more time-pressured. BUt overall, if was quite of a fresh experience. I never would of imagined having a class by email. hehe... ( i would never have this idea~~)

Student 3:

I think it's good. I write more in this way than I discuss in the class. Somepeople down the hill won't climb to the class.

It's fun and a good experience. I think we can one week in class and another week in E-mail discussion. (We cab also use Msn Messenger. it's convenient. We can write and talk on it.) Student 4:

I think it's excellently goooooood!!!!!

Though I was asdounded by the sudden notice to attend the class like this, it's a superb experience.

I highly recommend this form of class. Thank you and bon voyage!!! Student 5 left early and did not provide written feedback

Student 6:

Actually, it is an interesting expereince, and it can also force everyone to "write" something. However, I still prefer lecture face to face because keeping reading e-mail makes me feel dizzy . . . ^ ^

It is ok so far for today. Student 7:

Well, it's unbelievable! But I would like to have a meeting on MSN or whatever. It will be more convient for people to discuss, but you might miss some people's answers. Thinking twice, I think it's better for this kind of discuss, though my mail-box is almost full!!!! Student 8:

VERY GOOD..

I can hear all opinions from different voices TO MY COMPOSITIONS..=.+ I will find more evidence..

SO CHALLENGEOUS... Student 9:

It's quite interesting and different from the traditional way in classroom. Everyone expresses his/her opinion and gives suggestion. Although,it may be a little "cruel" to the writers to read so much "critiques" about their essays. I can't imagine how my essay will be critized in the future. However, I will still be glad to hear all kinds of suggestion from my classmates. That will help me to make progress on writing essay. I think that I will benefit from those opinions. Having class on line also has disadvantages, especially when the speed of the internet is slow. Sometimes I almost lose my patience. By the way, my computer was broken down this

morning. I was very angry that why misfortune happened to me in the most important and emergent moment!!! I had no choice but borrowing my roomate's computer to attend this on-line class. >"<

Anyway, I think this email writing class is great! Maybe we can have class like this in the future. (But I must have my computer fixed as soon as possible. I hope that I won't lose all my data in the computer.)

See you next week! Student 10:

I think this email writing class can encourage/force everyone to talk about thier ideas, unlike sit-and-idle problem in the meeting class. And it indeed offers good opportunities for me to practice writing. Besides, sitting in fornt of my computer at home is far easier and more convenient than climbing to the class at hilltop.

I'd like to have it more if possible. :P Student 11:

and i highly suggest that we can have class in this way foerever. i even pay more attention through the way~

Student 12:

good....i think everybody is forced to express their opinions, though we might lose the chance to speak. however, ________ is obviousely working harder in this way. haha!! novel

Appendix 2 Student Feedback after CMC Composition Class 2 Student 2:

Yes yes, it did help me. Student 4:

Yes, thank you a lot. ______ wants to play PS2 and she dare not tell you. Student 7:

I think....we have done this kind of exercise as homework before.

Actually, I would like to know more about what I do wrong in the citation of my essay, except the authority of the sources.

Student 8:

Yes, and more interesting. Student 10:

Yes. By asnwering these study questions, I can get the main ideas, key points and basic styles more easily from reading the articles.

Student 11:

sort of because the question forced me to check it out on the citation web. Student 12:

Maybe...but why is everyone's answer so different? can you give us some comment or

direction? Otherwise, I don't know what does it mean by just emailing forward their answers. Student 15:

Well, I guess this helped anyway, althoough i would look for answers by myself If I find problems about citation. But using this way to force us to read the web page about APA helps too. That's good.