跨國文化的協調:非語言部分

全文

(2) Ab stract:. The unprecedented growth of international business has resulted in an increased volume of face-to-face negotiations between parties from different cultures. The importance of cross-cultural negotiation in today’s business environment is reflected in the growing body of negotiation literature. However, there is a notable void in negotiation research regarding the impact of culturally divergent modes of nonverbal communication. The purpose of this paper is to identify the key linkages between the disparate fields of cross-cultural negotiation and nonverbal communication. A model illustrating how key determinants of nonverbal communication affect cross-cultural negotiation is presented. The goal of the model is to provide some valuable insights into how negotiators from diverse backgrounds communicate on a nonverbal level, and how divergences in nonverbal communication affect the negotiation process and outcomes.. i.

(3) Abstract: 國際化企業如雨後春筍冒出 ,使得我們面臨空前大量不同文化對手的談判 .從談判 文獻的鉅增 , 可看出企業面臨誇國談判的重要性 .然而, 關於非語言溝通文化分散模 式的衝擊,在談判中, ? 相當缺乏。 本研究主要確認跨國文化談判及非語言溝通兩個不同領域關鍵連結.我們採用了 一個模型來說明非語言溝通影響跨國文化的談判.此模型也提供了某些 觀點來說明 不同背景談判者如何使用非語言來溝通及非語言溝通如何影響談判過程及結果。. ii.

(4) Table of Contents. I.. INTRODUCTION … … ..… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 1 i.. Main Argument… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 1. ii.. U.S. – China Trade and Negotiation … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 2. iii.. Motivation and Purpose … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 3. iv.. Defining Negotiation… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 3. SECTION 1: LITERATURE REVIEW. 1.. Approaches to Negotiation Research … … .… … … … … … … … … . … ..4 1.1 Normative and Prescriptive Approaches … … … … … … … … … … … 4 1.2 Individual Differences Approach … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 5 1.3 Cognitive or Information-Processing Approach … … … … … … … … 5 1.4 Structural Approach… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 7 1.5 Social Contextualist Approach … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 7. 2. Negotiation Research Approaches and Nonverbal Communication … … … 10. 3. Cross-Cultural Negotiation Research … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..11. 4. Nonverbal Communication Research … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … .12 4.1 Kinesics … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 13 4.2 Vocalics… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 13 4.3 Proxemics… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 14 4.4 Haptics… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 15 4.5 Oculesics… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 15 4.6 Chronemics… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 16 4.7 Appearance and Artifacts… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 17 iii.

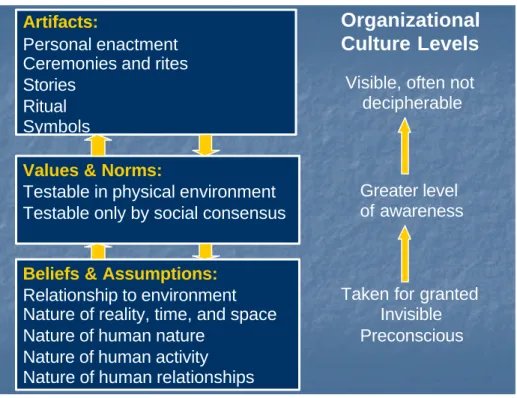

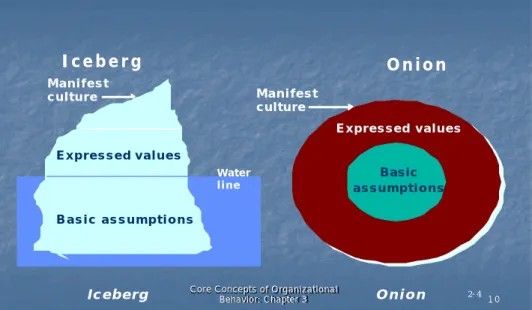

(5) SECTION II: KEY CONSTRUCTS INFLUENCING CROSS-CULTURAL NEGOTIATION & NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION … … … … … … … … ..18. 1. National Character … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … .18 a. Hofstede’s Model of National Culture… … … … … … … … … … … … 19. b.. i.. Uncertainty Avoidance… … … … … … … … … … … … … 20. ii.. Individualism … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 21. iii.. Power Distance … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 23. iv.. Masculinity… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 24. v.. Long-term Orientation… … … … … … … … … … … … … 25. National Character and Cross-Cultural Negotiation… … … … … 27. c. Cultural Divergence: China and the United States… … … … … … 27 d. Face Management and Context … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 28. 2. Organizational Culture… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..............31 2.1 Hofstede’s Organizational Culture Model … … … … … … … … … 32 2.1.1 Process versus Results… … … … … … … … … … … … … 33 2.1.2 Employee- versus Job-Oriented Cultures… … … … … 34 2.1.3 Parochial versus Professional … … … … … … … … … 35 2.1.4 Open versus Closed Systems … … … … … … … … … … 36 2.1.5 Loose versus Tight Control … … … … … … … … … … 36 2.1.6 Normative versus Pragmatic … … … … … … … … … … 37 2.2 Organizational Culture and Nonverbal Communication … … … 38 2.3 Reynold’s Organizational Culture Model … … … … … … … … … 39 2.3.1 External versus Internal Emphasis … … … … … … … … 39 2.3.2 Task versus Social Focus … … … … … … … … … … … … 39 2.3.3 Conformity versus Individuality … … … … … … … … … 40 2.3.4 Safety versus Risk … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 40 2.3.5 Ad Hockery versus Planning … … … … … … … … … … 41 2.4 Schein’s Model of Organizational Culture … … … … … … … … … 41. iv.

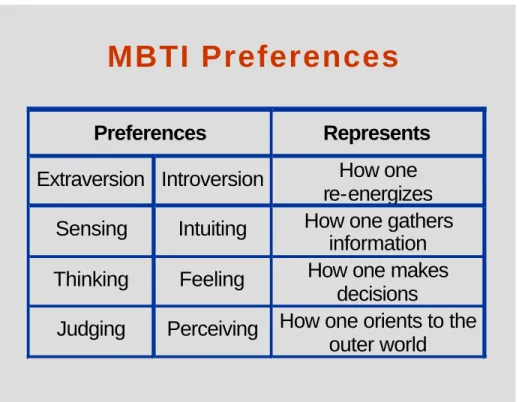

(6) 3. Individual Personality… … … … … … … … … … … … … … .… … … … … … … .44 3.1 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)… … … … … … … … … … … 45 3.1.1 Extroversion-Introversion … … … … … … … … … … … … 45 3.1.2 Sensing-Intuition … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 45 3.1.3 Thinking-Feeling … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 46 3.1.4 Judging-Perceiving … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 46 3.2 The “Big Five”… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 48 3.2.1 Extroversion … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 48 3.2.2 Agreeableness … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 49 3.2.3 Conscientiousness… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 49 3.2.4 Neuroticism … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 49 3.2.5 Openness… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 50 3.3 Impact of Individual Personality on Nonverbal Communication … … 51. SECTION III: CROSS-CULTURAL NEGOTIATION … … … … … … … … … .52. 1. Components of Negotiation … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 52. 2. Cultural Communication Styles … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 52. 3. Negotiation Process … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … .53 3.1 Cultural Divergences Between Chinese and American Negotiation Processes … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 54. 4. Negotiation Strategies and Tactics … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 55 4.1 Distributive Approach … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 56 4.2 Integrative Approach… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 56. SECTION IV: THE NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION MATRIX MODEL. v.

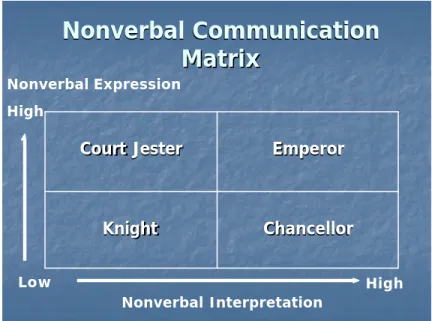

(7) 1. Determinants of Nonverbal Expressive Behavior … … … … … … … … 58 1.1 Internalized Values and Norms … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 58 1.2 Individual Differences … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 59. 2. The Nonverbal Communication Matrix … … … … … … … … … … … … 60. 3. Application of the Matrix… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ...61. SECTION V: CONCLUSION … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …. 62. REFERENCES … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 65. vi.

(8) Cross-Cultural Negotiation: The Nonverbal Component. I.. Introduction Accompanying the myriad of benefits brought about by the global village, is an. equally numerous amount of challenges and problems that modern managers must face. The unprecedented growth of international business has resulted in an increased volume of face-to-face negotiations between members of different cultures. In order to be successful in such a diverse and complex business environment, managers must be globally aware and have a frame of reference that goes beyond a country, or even a region, and encompasses the world (Cateora, 1996). Effective negotiation skills are becoming increasingly important for today’s global managers. By some estimates, global managers spend more than half of their time negotiating (Fayweather and Kapoor, 1972, 1976; Perlmutter, 1984; Adler, 1991). A key component of successful international negotiation is effective cross-cultural communication. This requires that negotiators understand not only the written and oral language of their counterparts, but also other components of culturally different communication styles (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). In particular, it requires an understanding of the more subtle, nonverbal aspects of communication. These aspects of nonverbal communication play a vital role in our understanding of the communication process (Duke, 1974).. i.. Main Argument It has been estimated that only 35 percent of the social communication among. people is verbal, with the remaining 65 percent consisting of nonverbal modes of behavior. 1.

(9) (Harrison, 1965; Birdwhistell, 1970). Effective cross-cultural communication is therefore dependent on understanding the subtle intricacies and differences in the communication styles of different cultures. This requires sensitivity to, and awareness of the potential messages contained in nonverbal behaviors. Given the importance of nonverbal aspects of communication, it is surprising how little research has been conducted on the impact of nonverbal behavior on cross-cultural negotiations. Although negotiation and nonverbal communication have been extensively researched and studied over the last few decades, very few studies have actually attempted to link these two fields together. Several negotiation theorists have mentioned the interplay of nonverbal modes of communication, albeit on a fairly cursory and superficial level (ex. Graham, 1984; Martin and Herbig, 1998; Tung, 1982). Rather than underlining and investigating the importance of nonverbal behavior in negotiation, most theorists have typically discussed the issue as a small facet of the negotiation process. This superficial glossing of the issue has therefore emasculated the importance of nonverbal communication in cross -cultural negotiations.. ii.. U.S. – China Trade and Negotiation The increasing frequency and importance of international business between the US. and China has contributed to the growing need for cross-cultural negotiation skills among today’s global managers. According to US statistics, China's export to the United States reached US$243.5 billion in 2005, accounting for 32 per cent of China's US$762 billion total exports and 14.6 per cent of US total imports. As a result, China has become the United States’ third-largest trade partner. Not only does this demonstrate the mutual dependency of these two markets, but it also underscores the importance of effective negotiation. Since effective negotiation is dependent on effective communication, both American and Chinese negotiators need to be able to understand, and accurately interpret their counterparts’ positions, perspectives, and expectations. A prerequisite of this understanding is the ability to recognize and interpret both the verbal and nonverbal aspects of communication.. 2.

(10) iii.. Motivation and Purpose The purpose of this paper is to discuss the importance of nonverbal communication. on cross -cultural negotiation processes and outcomes. Examining the broad base of literature concerning negotiation and nonverbal communication, this paper will attempt to link the critical findings of these two fields of research into a coherent and comprehensive model of cross-cultural negotiation – encompassing both verbal and nonverbal aspects of communication. The first section provides an overview of negotiation and nonverbal communication research literature. This is followed by a discussion of three categories of determinants that affect cross-cultural negotiation and nonverbal communication, particularly as they relate to U.S.-China commercial negotiations: (1) national character; (2) organizational culture; and (3) individual personality. The third section discusses the components and stages of the negotiation process, which is followed by a summary of the general strategies and tactics adopted by international negotiators. The paper will conclude with the presentation of a model that outlines key determinants of nonverbal communication, and how they impact cross-cultural negotiations.. iv.. Defining Negotiation There is ample literature on negotiation, which include contributions from various. fields ranging from social psychology to communication to business management. The definition of ‘negotiation,’ however, tends to vary greatly in terms of specificity and breadth. Cohen (1980) defines negotiation as “the use of information and power to affect behavior within a web of tension.” Gulbro and Herbig (1995) define negotiation as “the process by which at least two parties try to reach an agreement on matters of mutual interest.” Fisher and Ury (1991) take a more informal approach, defining negotiation as “a basic means of getting what one wants from others and a communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed.” Other authors such as Odell (1999) are more formal in their definition of negotiation, stating that “negotiation is a sequence of actions in which two or more parties address demands and proposals to each other for the ostensible purposes of reaching an. 3.

(11) agreement and changing the behavior of at least one actor.”. Even with this wide range of definitions, most authors tend to converge on several basic characteristics of negotiation. Fowler (1986) and McCall and Warrington (1989) have pooled together an extensive array of negotiation literature in order to identify some of the basic characteristics of negotiation. First, negotiation is essentially an interaction between two or more parties. Second, each party has different interests and objectives, which prevent the achievement of an outcome – hence, the necessity of negotiation. Third, each party has a degree of power over the other’s ability to act. Finally, the parties need each other’s involvement in achieving some jointly desired outcome.. SECTION I: LITERATURE REVIEW 1.. Approaches to Negotiation Research The broad base of negotiation literature has resulted from various approaches taken. by negotiation researchers and theorists. Carroll and Payne (1990) have noted that negotiation research tends to fall under four general approaches: (1) a normative or prescriptive approach, based on rational models of bargaining; (2) an individual differences approach that focuses on personality factors; (3) a cognitive or information-processing approach that highlights the role of judgmental heuristics and biases in negotiations; and (4) a structural approach grounded in sociological conceptions. Kramer et. al. (1993) have identified a fifth approach which they term the social contextualist approach. Each of these approaches will be described briefly in the following sections.. 1.1. Normative and Prescriptive Approaches The normative approach is primarily based around game theory models, which. emphasize economic rationality. Game theory models assume that negotiators are. 4.

(12) operating with perfect rationality and perfect or near perfect knowledge of all parties. It is this assumption that has enabled the development of the prescriptive approach which prescribes procedures and user behaviors that negotiators should follow in order to optimize the negotiation (Bui, 1994; Teich, 1996). The prescriptive approach posits that in fully rational negotiations, there are certain optimal strategies that negotiators should adopt to maximize their economic gains. Sakawa and Nishizaki (1996) state that the game theory allows for formal problem analysis and the specification of well-defined solutions, which can therefore be used for an extensive evaluation of the scenarios and specific moves of the parties involved, their strategies, and the determination of the characteristics of the potential compromise solutions. In other words, the game theory constitutes a way to systematically understand the interests of the parties in order to infer the possible range of moves and countermoves that will result in a certain outcome.. Several weaknesses have been identified regarding the game-the oretic approach to negotiation research, particularly its assumptions of strict rationality and perfect information (Bazerman, 1998; Bazerman and Neale, 1991). For numerous reasons, such as cognitive limitations, biases, and bounded rationality, negotiators often deviate from optimally rational behavior. Despite some problematic assumptions, game-theoretic approaches remain useful in the prior and posterior analysis of the group decision or negotiation problems. A complete analysis of negotiations, however, must include an analysis of key factors that influence negotiator attitudes and behaviors. One such factor is the divergence between negotiators, particularly in terms of their personality. This facet of negotiation research is more thoroughly investigated in the individual differences approach.. 1.2. Individual Differences Approach The individual differences approach to negotiation research focuses on the effects. of negotiator differences on negotiation. Most research in this area emphasizes individual personality factors that impact negotiation. The focus of much of this research lies in classifying individuals into types. Numerous studies have documented personality. 5.

(13) influences on both the content and the style of dyadic interactions (Kroeger and Thuesen, 1998; Barry and Friedman, 1998; Rubin and Brown, 1975). Personality is generally defined as an individual’s consistency in behaviors and reactions to events. Negotiators tend to exert their personality traits or individual preferences during negotiations, which in turn, serve to influence the proceedings and outcomes.. Negotiator traits and preferences are conditioned by the broader social environment from which they come. The effect of individual differences and personality traits on negotiation is moderated by other factors such as national culture and context. Although the results are still inconclusive with regard to the universality of principles and the functioning of personality measures across cultures, it is still important to recognize the potential influence that personality has on the negotiation process as well as the outcomes. As a result, the research-base concerning the impact of individual differences on negotiation continues to grow. Closely related to the individual differences approach to negotiation research is the cognitive or information processing approach.. 1.3. Cognitive or Information-Processing Approach This approach to negotiation research highlights the role of judgmental heuristics. and biases in negotiations. It focuses analysis on the cognitive processes among decision makers – namely the perception and interpretation leading to the construction of representations and the use of heuristics. Heuristics are simple, efficient rules of thumb which enable people to make decisions and solve problems in complex situations or situations involving incomplete information. Problems are typically interpreted and categorized through references to pre-existing knowledge structures and judgmental heuristics.. The cognitive approach to negotiation research has formed the foundation for structural problem representations. This has not only provided a means to reduce structural uncertainty in negotiations, but it has also enabled decision-makers to connect opportunities to needs so that they correspond to potential decision outcomes. There are. 6.

(14) several well-documented techniques for utilizing cognitive maps as a tool to account for unexplained variance in data (Huff and Fletcher, 1990). One such technique, involving schemas, is based on the assumption that past experience structures our interpretation of events and guides our behavior. Schemas are abstract cognitive structures that contain knowledge about a given type of target or stimuli (Fiske and Taylor, 1991). These schemas are said to guide and structure the perception and interpretation of new information, such that new information is processed in ways that are congruent with a person’s preexisting schemas (Abelson, 1981; Fiske and Taylor, 1991; Rumelhart and Ortony, 1977). As a process-oriented tool, this technique can be used to help negotiators better understand their own assumptions about a problem, the perspectives of the other parties, and the ways that others perceive their position.. Individuals are limited in their cognitive ability to process vast amounts of information, which requires them to reduce complex inferential tasks into simpler operations. By focusing on the systematic biases in negotiators judgments, the cognitive approach attributes discrepancies from rationality to human limitations in information processing capacity. Several studies have documented various biases which lead negotiators to deviate from optimally rational behavior (Dawes, 1998; Pinker, 1997; Bazerman and Neale, 1991). It is these biases that tend to ca use negotiators to make decisions that are inconsistent, inefficient, and based on normatively irrelevant information. As such, knowledge of these biases plays an integral role in the negotiation process, particularly in terms of how they affect negotiator behaviors and attitudes.. In spite of all the insightful information provided by the cognitive approach to negotiation research, many authors criticize this approach for ignoring a number of other factors that are critical in negotiation – such as context, negotiator personality, and culture (Greenhalgh and Chapman, 1995). Several authors have also noted the difficulty in applying and integrating cognitive maps in actual negotiation situations. This is due to the fact that these maps are typically both user and context specific, which exclude them from generic application across a wide range of situations. The structural approach to negotiation research focuses attention on situational factors that influence the negotiation. 7.

(15) process.. 1.4. Structural Approach The structural approach to negotiation research focuses on the situational and. structural variables that define the context of the negotiation. These are the variables that negotiators inherit and normally cannot influence in the short-term – including the presence of constituencies, parties’ incentives and payoffs, power distribution, deadlines, the number of people on each side, setting, the nature of the issue, and interpersonal dynamics and mood. Several studies have been conducted on the various impacts that contextual factors have on negotiation and negotiator affect (Druckman, 1967; Axelrod and May, 1968; Marwell and Schmitt, 1972).. The growing body of research linking negotiators’ behaviors and outcomes to situational contexts and constraints suggests that there is a significant amount of validity in this approach. Despite the importance of recognizing situational variables and their influence on negotiations, it is important to also recognize that situational variables are not the only factors that affect the negotiation process or outcome. Furthermore, the diversity of contextual conditions having the potential to influence negotiations – coupled with the fact that most situational variables are context specific – makes it very difficult to draw definite conclusions on the impact of any particular factor. Consideration of contextual conditions should therefore be regarded as a part of a broader range of variables that influence negotiations. Another important variable that has a strong influence on negotiation is the social environment surrounding the negotiation. Further investigation into this area can be seen in the social contextualist approach to negotiation research.. 1.5. Social Contextualist Approach Kramer et. al. (1993) contend that it is important to take into consideration the. impact of the social environment, within which negotiations are embedded. More specifically, they argue that there is a need to consider negotiation within the context of. 8.

(16) preexisting social ties and relations. Other authors such as Pruitt (1981) also allude to the importance of the social side of negotiation. Most laboratory research on negotiation consciously try to minimize or control information regarding preexisting social relational variables in order to minimize their impact on decision-making (Greenhalgh, 1987). Tetlock (1985) states that in experimental research on decision-making, subjects in the typical laboratory study “function in a social vacuum in which they do not need to worry about the interpers onal consequences of their conduct.” This, however, is not a realistic representation of most decision-making and negotiation situations in today’s global economy.. Traditional models, which posit that decision makers are “strangers, with no shared histor y, who meet, interact strategically in their self -interest … and who will never meet again” (Hoffman et. al. 1991), seem overly simplistic and dubious given today’s interconnected business environment. In the current hypercompetitive global economy, long lasting relationships between suppliers, distributors, and customers have become key drivers of success and viability. As such, decision-making typically occurs in a social context whereby social identity and interpersonal accountability influence negotiator decision-making (Kramer et. al., 1993). Social identity refers to the extent that a negotiator identifies with, or is attracted to, a particular group. Kramer et. al. (1993) argue that when a distinctive personal identity is salient, negotiators will adopt relatively self-interested orientations, focusing attention primarily on their own outcomes. However, if social identity is salient, then negotiators are more likely to express greater concern for the outcomes obtained by the other negotiating party. Furthermore, when negotiators feel accountable to others, they are more likely to be concerned not only about objective outcomes or payoffs, but also how those outcomes are “perceived and evaluated by those to whom they feel accountable” (Kramer et. al., 1993).. Social identity and interpersonal accountability may serve to constrain the potential self-interested behavior of negotiators. In other words, the expectation of future interaction between parties tends to increase cooperation during negotiations, since longer-term issues such as reputation, trust, and harmony are brought to bear on short-term decision-making. 9.

(17) (Kramer et. al., 1993). As a result, social contextualist factors are important considerations in negotiations, particularly when dealing with parties that greatly value social identity, or when future interactions are expected.. 2.. Negotiation Research Approaches and Nonverbal Communication Although all five approaches to negotiation research have been widely applied in. various settings from laboratories to field studies, there exists virtually no research directly linking any of these approaches to the field of nonverbal communication. Each of these approaches displays a suspicious gap in research pertaining to the nonverbal components of communication. The normative and prescriptive approaches, which purport that negotiators are fully rational and have perfect or near perfect information, assume that communicated messages are unambiguous and clear. Since nonverbal modes of communication have various interpretations depending on the situation and the relationship between the interactants, they tend to be overlooked in both the normative and prescriptive approaches to negotiation research. Instead, these approaches primarily focus on the verbal side of communication, largely ignoring the nonverbal side.. The individual differences and cognitive approaches to negotiation research indirectly incorporate nonverbal components of communication into their research. The latter approach, the cognitive appr oach, does this by focusing analysis on the use of judgmental heuristics that are used to interpret specific issues and behaviors. The former approach focuses on individual personality differences that influence the content and style of negotiations. However, these approaches to negotiation research do not directly analyze the impact of nonverbal communication. This is a fairly significant omission given the critical insights that can be gauged about negotiators’ cognitive perceptions and attitudes – simply by recognizing nonverbal cues. Kirch (1979) notes that “nonverbal communication occurs to a greater extent beneath the level of awareness,” which suggest that nonverbal communication is essentially a cognitive process. The lack of research linking human cognition to nonverbal communication is therefore, a major oversight in this domain of negotiation research.. 10.

(18) The structural approach to negotiation is primarily concerned with the influence of contextual factors on negotiation proceedings. However, this preoccupation with the predominantly tangible or visible aspects of negotiation creates a problematic oversight of critical intangible aspects. In particular, studies in this area largely ignore the importance of nonverbal communication in negotiations. This creates a potential caveat in the portrayal of the negotiation process, since nonverbal cues play such an important role in the communication process.. 3.. Cross-Cultural Negotiation Research Cross-cultural negotiation research thus far has focused on two general areas:. intra-cultural negotiations and inter-cultural negotiations. Intra-cultural negotiations are those that occur between parties from the same culture, whereas inter-cultural negotiations are those that occur between parties from different cultures. Studies on the latter area tend to focus on the difficulties arising in cross-cultural negotiations due to cultural differences. Most of these inter -cultural studies outline strategies to overcome ‘cultural divergences’ (e.g. Koldau, 1996; LeBaron, 2003; Lui et. al., 2003; Luxmoore, 2000). Studies relating to intra-cultural negotiations, on the other hand, focus on descriptive comparisons of negotiation styles (e.g. Graham, 1993; Neuliep and Hazelton, 1995). Whilst intra-cultural negotiations are decidedly challenging, inter-cultural negotiations add a whole new level of complexity to the negotiation table.. Negotiations between members from different cultures present an added challenge. Not only are the negotiators separated from each other in terms of their negotiating positions, but they are also separated from one another in terms of language, communication styles, business etiquette, as well as by a different way to perceive the world, to define business goals, to express thinking and feelings, and to show or hide motivation and interests (Tung, 1991). The common Western ideal of a persuasive negotiator is one who is highly skilled in debate, able to overcome objections with verbal flair, and an energetic extrovert (Gulbro and Herbig, 1995). This is far from the ideal that the Chinese hold for negotiators. The Chinese believe that a negotiator should be. 11.

(19) thoughtful, cooperative, considerate, and respectful. Consequently, the Chinese typically react negatively to the Western ideal type of negotiator, regarding them as unnecessarily aggressive, superficial, and insincere. It is, therefore, important that negotiators recognize that many of the rules, behaviors, and approaches that are successful to domestic negotiations may not apply to cross-cultural negotiations. Adler and Graham (1989) argue that negotiators do indeed change and adapt their ‘within culture’ behavior when dealing with foreign counterparts. This conclusion has several important implications both theoretically and practically. First, if this conclusion is valid then previous research based on the assumption that domestic negotiating styles predict international styles need to be reexamined. Second, on the practical side, this conclusion suggests that international negotiators need to be wary of behavioral discrepancies in cross-cultural negotiations.. In the field of cross-cultural negotiation, few studies directly focus on the importance of nonverbal communication. Some authors (e.g. George et. al, 1998; Herbig and Kramer, 1995; Tung, 1991) mention how cultural differences in nonverbal communication may impact negotiation. However, most of the cross -cultural research to date simply alludes to the potential impact of nonverbal communication on the negotiation process. As a result, there is a notable void in research linking nonverbal communication to cross-cultural negotiation.. 4.. Nonverbal Communication Research The study of nonverbal communication has long been a major field of research in. the Communications discipline. However, it wasn’t until Edward T. Hall’s work in the 1950’s that cultural differences in nonverbal communication became an area of formal academic interest in a variety of other fields such as Anthropology, Sociology, and Psychology. In the broadest sense, nonverbal communication is defined as “all the messages other than words that people exchange in interactive contexts” (Hecht et. al., 1999). Most research involving nonverbal communication focus on several general codes of nonverbal signals including: kinesics, vocalics or paralanguage, proxemics, haptics, oculesics, chronemics, appearance, and artifacts.. 12.

(20) 4.1. Kinesics Kinesics is the study of communication through corporeal movements. Every. culture has a distinct set of movements to communicate nonverbally including body posture, facial expressions, hand gestures, and movement. As with oral communication, there is no universal code for what these movements mean in all societies. Furthermore, since most of these nonverbal signals are neither sent nor received on a conscious level, it is difficult to interpret their precise social meaning without considering cultural and contextual factors. Some aspects of kinesics such as hand gestures are very much culture bound, while other aspects are less conscious reflections of attitude and engagement. Consequently, lists of gestures and their meanings are useless without accompanying reference to the specific contexts in which the gestures and movements are observed (Duke, 1974).. Americans are comparatively more expressive than the Chinese in terms of hand gestures to embellish and add emphasis to oral communication. The Chinese tend to be more subtle and formal in terms of body language and gestures. Several nonverbal communication researchers, however, have noted that gestures are conspicuously limited or absent in more formal levels of communication, and most common in casual or intimate interaction (Kirch, 1979). As such, it is important to note that the use of gestures is varied and adjusted according to contextual factors.. 4.2. Vocalics Vocalics, which is closely related to paralanguage, includes all the vocal cues other. than words. Various aspects of voice can be measured such as pitch level and variability, duration of sounds, pauses and response time, volume, resonance, articulation, rate, rhythm, and the use of vocal filler sounds. These aspects of vocalics can be altered and refined to communicate key elements of an individual’s personality, mood, and cultural background.. While Americans typically rely on words as the most important vehicle of 13.

(21) communication, the Chinese tend to transmit the most important information via nonverbal channels such as tone of voice and the use of silence (Tung, 1991). Graham and Sano (1989) argue that Americans usually focus more on the less important, worded task-related information. As a result, they tend to ignore the more informative nonverbal channel of communication. The use and interpretation of nonverbal modes of communication play an integral role in the negotiation process. For example, the Chinese usually use long moments of silence to contemplate the issue at hand, or when an impasse is reached. Conversely, the American style of communication generally contains only a few long silence periods. As a result, the common American negotiator’s reaction to silence is to try to fill it with either words or even concessions. Thus, Chinese negotiators have been noted to use silence as a bargaining tactic against Americans (Hall and Hall, 1987).. 4.3. Proxemics Proxemics focuses on how people use space to communicate. Each culture. prescribes appropriate distances for various levels of communication. Violations of these spatial rules tend to cause discomfort, anxiety, misunderstandings, and even offense. A lack of awareness about t he importance of distance in communication can create barriers to communication. Hall (1959, 1996) outlines four zones of personal space which have communicational significance in American culture. These spatial distances are: (1) intimate zone – for intimate relationships; (2) personal zone – for close friends and family; (3) social zone – for acquaintances and colleagues; and (4) public zone – for strangers. In most instances, distance is determined by social and cultural norms, as well as by the unique patterns of those interacting.. In negotiation research, the discussion of proxemics is usually related to seating positions and arrangements at the negotiation table. Duke (1974) conducted an in depth study on people’s behaviors in meetings and negotiation. His research revealed that the arrangement of seating affects the amount of interaction that occurs. More specifically, his findings suggest that leaders gravitate toward end (observational) positions at rectangular tables; whereas individuals who make the most vocal contributions tend to sit in a central. 14.

(22) position on either side of the table (Goffman, 1963). Intuitively, this pattern makes sense since directly-opposing positions offer full visibility, which is more conducive to frequent conversation. Similarly, positions at the ends of the negotiating table provide a supervisory vantage point, without the precondition of constant eye-contact.. 4.4. Haptics Haptics and Oculesics are the more sensory aspects of nonverbal communication.. They relate to physical contact and eye contact, respectively. Haptics, or touching, is closely related to proxemics and is a basic form of routine human interaction. The type of bodily contact deemed appropriate is deeply rooted in cultural values. Cultures tend to vary along the dimension commonly referred to as high contact – low contact. High contact cultures are characterized by a comparatively high degree of touching, whereas low contact cultures are characterized relatively low degree of bodily contact. Like proxemics, however, haptics are largely affected by relational and situational factors.. 4.5. Oculesics Studies in oculesics, or gaze, have shown considerable variation in the degree of. comfort with eye contact across cultures as well as subcultures. Some cultures, such as the United States, are very comfortable with and to a certain extent, expect eye contact to demonstrate attention, respect, and truthfulness. However, other cultures attempt to avoid eye contact for fear of being rude and disrespectful. This type of deliberate gaze aversion is evident in the Chinese culture, where prolonged eye contact is considered very rude and disrespectful. Variations in oculesic guidelines also exist within cultures particularly in terms of gender and age. In many cultures, there tend to be differences between males and females in terms of maintenance and duration of gaze. Similarly, age differentials have been noted to denote certain guidelines related to gaze – typically with the younger interactant averting the gaze as a sign of deference and respect.. Several negotiation theorists discuss cross-cultural differences in nonverbal 15.

(23) expressive behaviors that are likely to impact negotiations (George, 1998; LeBaron, 2003; Hendon et. al, 1996). These discussions typically differentiate between high-contact versus low-contact cultures. High-contact cultures are characterized by a heavy use of touching during communication, contact greetings, and small personal space (Hall, 1966; Hall and Hall, 1990). Conversely, low -contact cultures are characterized by very little physical contact during communication. Axtell (1998) developed three broad classifications of countries according to the degree of touching: no touching (e.g. Japan, United States, and England), moderate touching (e.g. Australia, China, and India), and touching (e.g. Latin America, Italy, and Greece). Therefore, the touch behavior that is regarded as proper in one culture may be quite inappropriate in another. In international business and negotiation settings, however, physical contact is typically restrained to handshakes at the beginning and conclusion of communications.. 4.6. Chronemics Chronemics concerns the way people perceive and manage time. The use of time. can be seen as a message system, communicating certain messages through punctuality, the amount of time spent with another, as well as waiting time. Different temporal attitudes generally fall within the spectrum of monochronic versus polychronic time. Monochronic cultures are highly conscious of time and schedules, which tend to promote certain expectations regarding punctuality, promptness, planning, and prioritizing. These cultures typically view time as linear and sequential with one activity or event taking place at a time. Polychronic cultures, on the other hand, view time in a more cyclical and flexible way. Unlike monochronic cultures that tightly compartmentalize time, polychronic cultures tend to perceive time more synchronously, allowing several activities to occur simultaneously (Cullen, J. and K. Parboteeah (2005).. The U.S. is a highly polychronic culture, which tends to worship time and manage it as though it were a scarce and tangible resource. This is reflected in their “time is money attitude” that espouses the values of promptness and punctuality. Planning and schedules are of the utmost importance to polychronic cultures, which are highly subservient to the. 16.

(24) clock. China is also considered a polychronic culture, although to a slightly lesser extent than the United States. In the Chinese context, punctuality is expected of lower-ranking members, but not necessarily of higher-ranking ones. As such, punctuality and waiting time is communicative of status and prestige.. 4.7. Appearance and Artifacts Physical appearance and artifacts are important facets of nonverbal communication.. They encompass the manipulative cues related to the body such as clothing and hairstyle, and the environment. These nonverbal cues are generally the most obvious due to their highly visible nature. Individuals can manipulate physical appearance and environmental artifacts to create certain impressions that communicate their status and personality. For example, one can change one’s clothing, hairstyle, and surroundings to create a desired impression or self-image.. In most business settings, physical appearance and artifacts tend to communicate a formal and professional image. However, cultures – both national and organizational – tend to differ on their emphasis on formality. The status -conscious Chinese are generally very mindful of physical appearance and artifacts in the communication of prestige and social ranking. Conversely, Americans tend to have a preference toward informality and equality. This typically leads to a more informal business setting and a more relaxed, and casual sense of business attire. However, when dealing with foreign counterparts, Americans may emphasize a greater degree of formality in physical appearance and artifacts.. Oftentimes people may not be consciously aware of how nonverbal cues influence their. feelings. and. interpretations,. yet. when. cross -cultural. differences. occur,. misunderstandings and negative feelings may arise (Graham, 1996). Three primary factors shape how nonverbal messages are sent and received: (1) culture; (2) the relationship between interactants; and (3) the situation (Holtgraves, 1992). Although there is evidence of some universal facial expressions, culture remains a strong influence on nonverbal. 17.

(25) communication. Cultural values of specific groups typically prescribe certain norms and values relating to space, touch, eye contact, and even dress. As a result, culture provides an overall template for nonverbal communication. Similarly, the type and stage of a relationship – whether close and intimate or distant and professional – dictates certain expected norms and behaviors among interactants. Finally, each communication situation presents its own parameters for nonverbal behaviors. These parameters include the physical environment, timing, temporary mental or emotional states , and the number of people present.. SECTION II: KEY CONSTRUCTS INFLUENCING CROSS -CULTURAL NEGOTIATION & NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION Kale and Barnes (1992) outline three broad antecedent constructs that have a major impact on cross-cultural negotiations. These distinct, yet highly inter-related constructs are (1) national character, (2) organizational culture, and (3) individual personality. Their affect on the negotiation process, negotiator affect, and negotiation outcomes have been well-documented in several other negotiation studies (Drake, 2001; George et. al., 1998; Graham, 1983; Liu et. al., 2003). Research on these constructs typically fall under the individual differences and structural approaches to negotiation. Although some studies allude to how these constructs may influence nonverbal communication, there is a discernable gap in literature regarding this issue.. 1.. National Character The first construct, national character, is undoubtedly the most well documented. factor affecting cross-cultural negotiations. Numerous authors have noted the importance of national character on inter-cultural negotiations (e.g. George et. al., 1998; Gulbro et. al., 2002; Kale and Barnes, 1992). National character consists of the beliefs, assumptions,. 18.

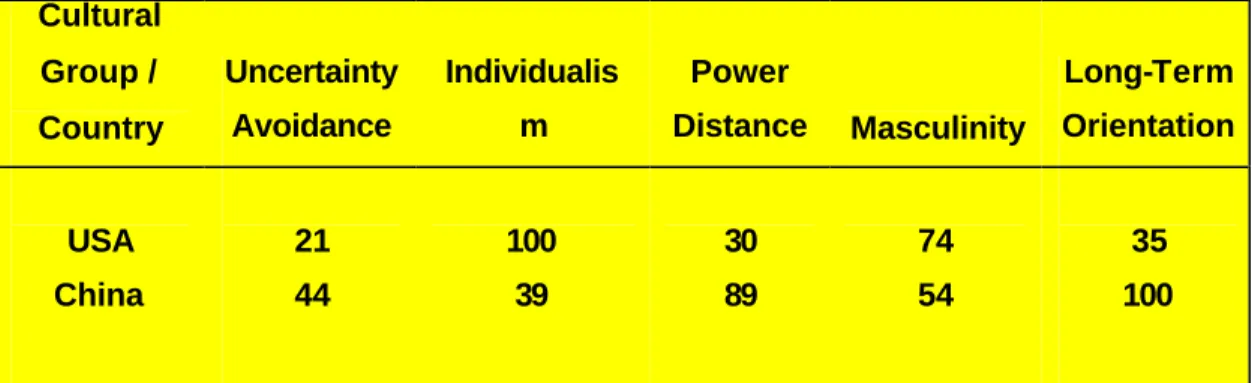

(26) values, and nor ms that are shared by the majority of the members of a country or cultural group (Cray and Mallory, 1998). Members from different national cultures are likely to behave differently in negotiations due to divergence in inherent assumptions, values, norms, as well as behavioral attributes.. 1.1. Hofstede’s Model of National Culture A number of cross-cultural negotiation studies draw on Hofstede’s (1980) model of. national culture. This model was initially developed in terms of differences in values and beliefs regarding work goals. Hofstede’s model outlines a four-dimensional framework of uncertainty avoidance, individualism, power distance, and masculinity. These four dimensions show meaningful relationships with important demographic, geographic, economic, and political national indicators (Triandis, 1982).. Later research by Hofstede and others led to the development of a fifth dimension, long-term orientation. Research on this dimension was unique since it did not rely on survey questions developed by Western researchers. Instead, Michael Bond and several Chinese colleagues developed a new survey based on questions developed by Asian researchers reflecting Confucian values. Hofstede and Bond have related this long-term orientation to the economic growth in rising Asian economies (Walder, 1986).. Table 1 presents a segment of the percentile ranks for Hofstede’s cultural dimensions as they relate to China and the United States. These dimensions provide a general overview of the different cultural patterns of the United States and China. They further provide a better understanding of how the US and China differ in terms of Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions.. 19.

(27) Cultural Group /. Uncertainty. Individualis. Power. Long-Term. Country. Avoidance. m. Distance. Masculinity. Orientation. USA. 21. 100. 30. 74. 35. China. 44. 39. 89. 54. 100. Source: Adapted from Hofstede, Geert. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill. Table 1: Percentile Ranks for Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions for the United States and China by Cultural Cluster (100 = Highest; 50 = Middle). 1.1.1 Uncertainty Avoidance The first dimension, uncertainty avoidance, assesses the extent to which members of a society avoid risk and feel threatened by ambiguous situations. It encompasses the norms, values, and beliefs regarding a tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. High uncertainty avoidance cultures seek to structure social systems in a predictable and orderly manner, where rules and regulations are paramount. Me mbers of these cultures feel a great deal of stress and anxiety in the face of risk, ambiguity, and uncertainty. Commonly held norms, values, and beliefs in these societies include avoidance of conflict, intolerance for deviant people and ideas, strict adherence to laws, and an emphasis on consensus (Hofstede, 1980). Business cultures in these countries tend to have management systems and processes that espouse dependable and predictable work processes, practices, and even employees (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Similarly, personnel are chosen for their potential fit with and loyalty to the organization in order to minimize interpersonal conflict and competition, reduce employee turnover, and increase predictability. High uncertainty cultures are characterized by extensive rules and procedures, as well as task-directed leaders, who give clear and explicit directions to subordinates thereby reducing ambiguity regarding job expectations.. 20.

(28) In contrast, low uncertainty avoidance cultures socialize members to accept and handle uncertainty and ambiguity without much anxiety or discomfort. Members of these cultures prefer more flexibility and freedom. They also take relatively more risks, and show a greater tolerance for opinions and behaviors that are different from their own (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Business cultures in low uncertainty avoidance cultures favor more autonomy and flexibility in the design of their organizations. They also tend to be more nondirective and person-oriented. There are typically fewer rules, regulations, and less supervision, thus giving employees more control over their work.. In terms of negotiation, high uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to engage in extensive preparation and planning prior to negotiations. In addition, negotiating parties from these cultures also place a greater degree of emphasis on group decision-making as a means for avoiding individual risk. As such, an individual is protected if the outcome of a decision produces less than satisfactory results. This type of behavior and approach to negotiation is characteristic of Chinese negotiators, who prefer to diffuse decision-making so that responsibility is difficult to locate. Negotiators in low uncertainty avoidance cultures such as the U.S. have comparatively more freedom in their approach to negotiations than do negotiators from high-uncertainty avoidance cultures. According to Koldau (1996), American negotiators usually prefer to handle a negotiation by themselves, taking full responsibility for the decisio ns made at the negotiation table. As a consequence, American negotiators are typically outnumbered by the Chinese negotiating team.. 1.1.2 Individualism The individualist-collectivist dimension refers to the extent to which individuals expect personal freedom versus group responsibilities. It describes the collectivity which prevails in a society, or the relationship between the individual and the group. Individualist cultures are those where members are concerned primarily with their own interests rather than those of the collective. They represent societies with very loose ties between individuals, allowing them a greater degree of freedom (Hofstede, 1980). These cultures perceive members as being unique individuals, who are responsible for themselves as well. 21.

(29) as their nuclear family. As such, individualist cultures value people for their own achievements, status, and other unique characteristics. Translated to the business setting, these beliefs, values, and norms create an environment where employees are not emotionally dependent on organizations, and where universalistic qualification is expected (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Universalistic qualification is the practice of applying the same qualifications universally across all candidates. It reflects the belief that open competition allows the most qualified individual to get the job, and that rewards should be based solely on individual performance.. Collectivist cultures, at the other extreme, view people largely through the groups to which they belong. One’s identity in collectivist cultures is dependent on group membership. Members of these cultures expect people to place the interests of their in-group above their own personal interests. In return for member loyalty, the in-group is expected to protect its members. Organizations in collectivist cultures tend to be characterized by a type of organizational paternalism, where people feel that a major reward for working is being taken care of by their organizations (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). This practice of organizational paternalism is reflected in a relatively high degree of loyalty and low turnover rate. This loyalty is further reinforced in reward systems, which promotes members based on seniority and age. Unlike individualist cultures, the selection process in collectivist cultures often shows favoritism toward favored groups such as family and friends. The logic behind this is that members from favored groups will show a greater sense of loyalty and responsibility to the organization. Decision-making in collectivist cultures is usually group-based. Cullen and Parboteeah (2005) present two key reasons for this phenomenon. First, since people in the organization are family members or trusted friends, privileged information flows up and down the organizational hierarchy more freely. Second, as a close-knit group, there is pressure to account for the feelings and desires of all members.. Since individualist cultures value autonomy, competition, and self-determination, negotiators from these cultures are likely to perceive negotiation competitively. Consequently, Americans – ranked highest on Hofstede’s individualism dimension –. 22.

(30) typically view negotiations as competitive, win -lose situations. In contrast, negotiators from collectivist cultures typically perceive negotiations from a more collaborative standpoint. This is due to the fact that collectivist cultures emphasize social duty and harmony, which tends to foster an appreciation for cooperation and an integration of needs. Collectivist negotiators are, therefore, likely to be more inclined than individualist negotiators to share information. Gundykunst (1987) argues that collectivist negotiators should be less inclined to adopt fixed-sum errors because success is primarily a factor of maximizing group rather than individual interests and because collectivists emphasize holistic thinking. Holistic thinking refers to a simultaneous, rather than sequential, consideration of negotiation issues. This has a major impact on the negotiation process, since it leads negotiators to view the process in a more cyclical and oscillatory rather than linear manner.. 1.1.3 Power Distance Power distance involves a society’s perception of and response to inequality. It indicates a society’s tolerance for social hierarchy, and inequalities in wealth and power structures. High power distance cultures exhibit discernible class and power differentials between individuals. These cultures typically espouse the belief that inequality is fundamentally good and that everyone ha s a place. Members of these cultures believe that most people should depend on a leader, and that leaders are entitled to certain privileges. This concern for hierarchy, inequality, and deference to superiors and elders is rooted in early socialization in the family and education systems. In the business context, organizations in high power distance cultures will commonly adopt management systems and processes that reinforce hierarchical structures, which maintain a high degree of supervision and conformity. Managers in high power distance cultures characteristically adopt an authoritarian style of management, based on the Theory X assumption that people inherently dislike work. Decision-making is centralized, enabling those at the top to make strategic decisions that perpetuate and support the hierarchy (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Such strategic decisions include reward and promotion systems based on elite associations rather than individual performance.. 23.

(31) Low power distance countries de -emphasize inequalities, and strive toward maintaining a relative equity in the distribution of power, status, and wealth (Kale and Barnes, 1992). Organizations in low power distance countries commonly adopt a more participative leadership style, based on the Theory Y assumption that people inherently like work. This leadership style is reflected in a more decentralized, and flat pyramidal structure of organizational design. Evaluation and rewards are based primarily on performance, and remuneration reflects a relatively smaller wage difference between management and worker.. Divergent attitudes relating to power and inequality have a major impact on negotiations. The American preference for interpersonal equality in human relations is in stark contrast to the high value that the Chinese place on role differences and status distinctions. In China, status generally determines the specific role each person is expected to play, which affects the communication style and behaviors that each member of the negotiating team adopts. The conflicting perspectives regarding status distinctions between the Chinese and American negotiators commonly lead to misunderstanding and misinterpretations. The lack of recognition of status differentials by Americans may make Chinese negotiators feel uncomfortable, and perhaps even offended. This will have a negative affect not only on the negotiation process, but also on the outcome of the negotiation.. 1.1.4 Masculinity Masculinity pertains to the extent to which societies hold values and role expectations traditionally regarded as predominantly masculine or feminine. Masculine cultures place a greater emphasis on achievement motivation, self -reliance, and material wealth. These societies typically distinguish between gender roles – where men are expected to be more assertive, decisive, and dominant. In masculine cultures, work typically takes precedence over other duties including familial ones. In such cultures, recognition on the job is considered a prime motivator, encouraging members to work longer hours. Managers are expected to act decisively and avoid the appearance of intuitive. 24.

(32) decision-making, which is often regarded as feminine (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Organizations in these cultures clearly define jobs by gender, with men holding jobs that are associated with long-term careers and women holding jobs associated with relatively short-term employment. Several factors, however, may be eroding traditional views of masculinity, particularly the growing incidence of delayed childbirth and s maller families, as well as the pressure for dual-career earnings and changing national cultural values.. In low masculinity cultures, or feminine cultures, the emphasis is placed on quality of life, interdependence, and relationships. Work typically has less centrality, with members adopting a more short-term, job-oriented attitude rather than a long-term, career-oriented one. Organizations in low masculinity cultures tend to distribute rewards based on job performance – independent of gender and persona l relationships. Unlike masculine cultures, low masculinity cultures take on a more intuitive decision-making approach, in addition to a more participative leadership style.. Herbig and Kramer (1991) suggest that high masculinity cultures tend to be more deal-focused, whereas low masculinity cultures tend to be more relationship-focused. They note that Americans tend to be more deal-focused, which makes them relatively more open to doing business with strangers since they perceive business as being predominately separate from their private lives. Chinese negotiators, however, are much more relationship-focused, preferring to get to know their business partners first – in order to establish a basis for trust and friendship. The different emphasis that Americans and Chinese place on the deal and relationship aspects of the negotiation has a major affect on the expectations and goals of each party.. 1.1.5 Long-term Orientation Long-term orientation, also known as Confucian dynamism, refers to the time orientation of a culture – whether short-term or long-term. This time perspective addresses the balance between short-term satisfaction and rewards with long-term opportunity and. 25.

(33) rewards. In long-term oriented cultures, members are more sensitive to social relationships and value synthesis. Value synthesis refers to the practice of taking apparently conflicting points of view and logic and seeking ways to reconcile them into practical solutions and general consensus. In this respect, tong-term cultures value security and stability. Organizations in these cultures tend to base selection of candidates’ on “fit” with the organization, in terms of personal and background characteristics (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). As such, most organizations are willing to trade initial weaknesses in work-related skills for long-term commitment to the organization. These organizations typically view training as an investment in long-term employment skills. Leaders in these organizations focus on developing social obligations and relationships, which is assumed to lead to long-term success and growth. This type of managerial approach is comparatively more supportive of entrepreneurial activity, since it is willing to trade short-term profits for long-term opportunities and rewards.. Short-term oriented cultures stress personal steadfastness and deep respect for traditional values. By focusing on the past and present, these cultures generally focus on immediate rewards rather than long-term opportunities. Organizations in short-term oriented cultures therefore focus on immediate, usable skills – since there is no guarantee or assurance of a return on any investment in employee training and socialization (Cullen and Parboteeah, 2005). Rewards are perceived in the short-term, focusing on pay and rapid promotion. Decision-making is predominantly based on a logical analysis of the current situation – the objective being short-term, measurable success. As a result, organizations in short-term oriented cultures are designed and managed to purposefully respond to immediate pressures from the environment.. Negotiation behavior is typically influenced by the degree of emphasis placed on establishing long-term relationships between parties. While China ranked the highest on Hofstede’s long-term orientation dimension, the U.S. ranked fairly low, comparatively. Since the Chinese are significantly more long-term oriented, they will typically invest more time and effort into the rapport and relationship building activities of a negotiation. Consequently, the Chinese negotiation process tends to be extremely time consuming, thus. 26.

(34) requiring patience and diligence from their counterparts. Americans, on the other hand, tend to focus more on short-term goals and immediate profitability. This short-term orientation is reflected in the Western perception that ‘time is money,’ which typically leads American negotiators to try to accelerate the negotiation process. This attempt to rush the process is perceived negatively by the Chinese, who regard it as either impatience or insincerity on the part of the Americans (Tung, 1982).. 1.2. National Character and Cross-Cultural Negotiation Hofstede’s unparalleled and expansive study found uniqueness and cultural. differences in the behavior between cultures. According to Hofstede, the construct of “national character” describes a pattern of enduring personality characteristics found among a large number of persons conditioned by similar background, education, and life experiences. These ‘national culture differences’ ha ve been extensively catalogued in cross-cultural negotiation research (e.g. Adler et. al., 1992; Graham, 1983, 1985; Cohen, 1991; Weiss, 1997). Several studies have suggested that people from different cultures approach negotiation differently, due to differences in their perceptions, attitudes, and expectations of the decision-making situation that are conditioned by the characteristics of their national culture (Ting-Toomey, 1988; Tse et. al, 1994; George et. al., 1998). These studies have pointed to a potential existence of a causal relationship between national culture and the process, strategy selection, and outcome of cross-cultural negotiations. Gulbro et. al. (2002) contend that since these groupings help explain behavior then perhaps these attributes may also be extended to explain and categorize the negotiating behavior of people from various cultures.. 1.3. Cultural Divergence: China & the United States Numerous researchers hypothesize that cultural similarity increases harmony,. therefore reducing friction in cross-cultural negotiations (Shenkar, 2001; House et. al., 2002). The logic behind this hypothesis is that culturally similar negotiators are more likely to share the same attitudes, values, beliefs, knowledge, management systems, leadership 27.

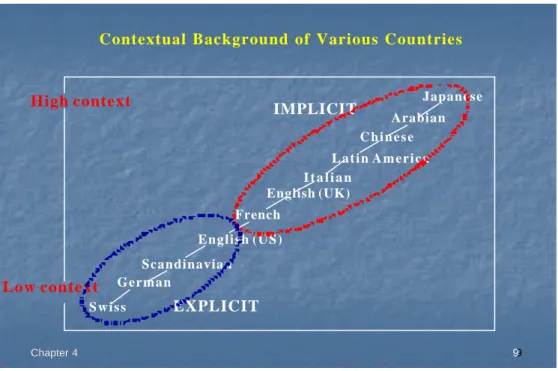

(35) styles, and behavioral norms (Lasserre, 1999; Kogut and Singh, 1989). In addition, similarities typically facilitate and enhance the ability to communicate, cooperate, integrate knowledge, and develop trust (Killing, 1983). Evidence supporting this hypothesis can be seen in the high rate of failure in inter-cultural negotiations between highly divergent cultures (Herbig and Kramer, 1991). Likewise, several authors have documented numerous difficulties faced by American negotiators when dealing with Chinese counterparts (e.g. Tung, 1982; Woo and Prud'homme, 1999; Ting-Toomey, 1992). Given the fact that the US and China differ quite extensively on virtually all of Hofstede’s national culture dimensions; it is highly probable that cultural divergence is a key factor behind the difficulties faced by their respective negotiators.. 1.4. Face Management and Context Aside from Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, two distinct differences between China. and the U.S. are readily apparent. The first relates to the issue of face management and the second relates to differences in communicating styles regarding context. The first issue, face management, points to an important divergence between the American and Chinese cultures. Face, according to Goffman (1967), is “the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact.” In other words, ‘face’ is the public manifestation of one’s self that results from the undertaking of ‘face-work’ – which includes all communication designed to create, support, or challenge a particular line (Holtgraves, 1992). Although concerns with face, and the linguistic strategies for managing face, are universal, cultures tend to perceive face-work and face -threatening issues differently (Holtgraves, 1991). This discrepancy of perceptions is readily apparent in negotiations between Chinese and Americans.. Numerous studies have documented the Chinese preoccupation with face in all facets of social and business life (e.g. Tung, 1982; Tse et. al., 1994; Tinsley and Pillutla, 1998; Holtgraves, 1991, 1992). To the Chinese, having face means having high status and prestige in the eyes of one’s peers. More specifically, face represents a mark of personal dignity that can be compared wit h a prized commodity. In this sense, the Chinese often. 28.

數據

相關文件

The natural structure for two vari- ables is often a rectangular array with columns corresponding to the categories of one vari- able and rows to categories of the second

Write three nuclear equations to represent the nuclear decay sequence that begins with the alpha decay of U-235 followed by a beta decay of the daughter nuclide and then another

It is important to use a variety of text types, including information texts, with content-area links, as reading materials, to increase students’ exposure to texts that they

This essay wish to design an outline for the course "Taiwan and the Maritime Silkroad" through three planes of discussion: (1) The Amalgamation of History and Geography;

Through a critical examination of some Chinese Christian intellectuals’ discussion on the indigenization of Christianity in China, this paper attempts to show that Chinese

- A viewing activity on the positive attitude towards challenges, followed by a discussion on the challenges students face, how to deal with.

This was followed by architectural, surveying and project engineering services related to construction and real estate activities (with a share of 17.6%); accounting, auditing

The remaining positions contain //the rest of the original array elements //the rest of the original array elements.