Feng Chia Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences pp. 229-253 , No. 1, Nov. 2000

College of Humanities and Social Sciences Feng Chia University

Cross-Cultural Emailing Politeness for

Taiwanese Students

Chao-Chih Liao

*Abstract

My students have been writing communicatively with international e-pals in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) since 1996. After analyzing the email messages of my students and their international e-pals, I have generalized the following seven email politeness rules for Taiwan-Chinese students to follow: (R1) offer counteranswers in the context for any questions that you ask, (R2) answer all questions asked by the e-pal, (R3) talk about the same topics as the e-pal, (R4) talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply, (R5) salute properly, (R6) do not ask questions to which your e-pal has given the answer, and (R7) do not make up stories. The above seven rules were formed in chronological order from R1 in 1996 to R6 and R7 in 2000.

This paper discussed how the seven rules were gradually formed and how I did five experimental studies on the Taiwan-Chinese e-mail reply, trying to find out why Taiwan-Chinese poorly follow R2 and the different communicative competence between males and females, as well as that between junior high school and university students.

Keywords: intercultural emailing, politeness, inter-emailing discourse

*

1.Introduction

There have been many papers or books discussing network etiquette (e.g., Hongladarom & Hongladarom, 1999; and Horton & Spafford, 1993). Horton & Spafford (1993) indicate postings should be distributed in as limited a manner as possible; the same article should not be posted twice to different groups; postings should not be repeated; posting other people's work without permission is not allowed; postings should be used neither for blatantly commercial purposes nor when one is "upset, angry, or intoxicated." Their rules do not seem applicable to cyberspace situations now, when numerous web sites are supported commercially. Pure commercial postings are tolerated and allowed.

Hongladarom & Hongladarom (1999) opine that Thai culture is affected by CMC (computer-mediated communication), which entails a greater risk of impoliteness. CMC politeness in Thai seems more negative than positive. Thai Netiquettes shown in Pantip.com are: (1) Messages critical of the King and/or royal family are absolutely prohibited. (2) Do not post messages which contain foul language and sexually explicit content. (3) Do not post messages intended to cause a person to be insulted or hated by others without citing a clear source of reference. (4) Do not post messages which are challenging or inciting, with the intention of causing quarrels or chaos on this web site, whereas the source of these quarrels or chaos is not due to free expression of opinions by a self-respecting person. (5) Do not post messages which attack or criticize any religious teachings. (6) Do not use pseudonyms which resemble somebody else’s real name with the intention of misleading others, so that the original owner of the name might be damaged or might receive loss to his/her reputation. (7) Do not post messages which might cause conflicts among educational institutions. And (8) do not post messages containing personal data of others, such as paper numbers, email addresses or telephone numbers, with the intention of causing trouble to the owner. (Source: http://pantip.inet.co.th/cafe/frame_rule.html) All these eight rules, unlike Horton & Spafford’s, relate to language use. The focus has shifted from technology to content, showing that internet or email has become a medium of communication.

Without checking Taiwan-Chinese conversational routines, the question-answer adjacency pairs discovered by Western linguists, such as Levinson (1983: 303-370) and Schegloff & Sacks (1973), seem obvious. Following A's question, B should/will answer because the question has a strong commanding power of an answer (Fishman, 1983: 94). After reading the aforementioned works, I have paid more attention to

Taiwan-Chinese interactions as a participant observer and found that many people do not answer questions; instead they talk about something else. In some circumstances, this kind of phenomenon constitutes "refusing" to answer the question (Liao, 1994; Sifianou, 1997: 5). Under other circumstances, I simply doubt its validity. For instance, in replying to Maria's E1, Chih-Hao wrote E2, but did not answer any of Maria's questions.

E1

Dear Winnie,

My name is Maria Agustina. I am a nine years old girl. My birthday is on May 25th. When is your birthday?

I live in Argentina and I study English. I like Spanish. I can't speak Chinese. I have got three sisters, a father and a mother. And you? Have you got a pet? I have got a dog. My favourite sport is swimming.

Bye!

Maria Agustina Blanco ---

E2

Dear Maria Agustina,

Winnie is not here. I write for her from now on. My name is Chih-Hao Hu. You can call me Chih-Hao. And I am a 19 years old boy. I live in Taipei, But at the moment, I live in school dormitory because I study in National Chung-Hsing University at Taichung. I major in Applied Mathematics. In our course, we also learn computer science and how to Design computer program. Those are interest.

In this time, I plan to design a homepage of our mathematical Department, So I must read many books as I can in order to expend my Information. Maybe you can see my homepage in the Internet after several Days. Another plan I want to achieve is to learn the instrument, guitar.

Well, I have some questions that I want to ask you. How is your feeling when you get the email? Do you have some goal to achieve? What foods do you like best? Do you often surf the Internet?

What do you always do in your free time? Sincerely yours,

Chih-Hao Hu

Sifianou (1997: 64-65) divides silence into two categories: mandatory and communicative. Communicative silence might be a way of preventing disagreement, or it may indicate that there is conflict. This is called 'eloquent silence'. Referring to E2, Chih-Hao's silence on the three questions seemed not related to disagreement or

conflict. This phenomenon might reflect the Chinese careless attitude in reading and/or listening.

The proposal of politeness rules is based on the presupposition that linguistic competence does not automatically lead to communicative competence (Hymes, 1974), nor does it guarantee the appropriateness of foreign/second language use in real contexts (Canal and Swain, 1980; Canal, 1983; Lii-Shih, 1987).

In contrast to linguistic politeness, Grice's Conversational Co-operation Principles (CP; 1975) are much discussed; they are for achieving maximum efficiency in communication (Brown and Levinson, 1987). The principles are reiterated here:

Quantity: Give the right amount of information: i.e., 1. Make your contribution as informative as required.

2. Do not make your contribution more informative than required. Quality: Try to make your contribution one that is true: i.e.,

1. Do not say what you believe to be false.

2. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence. Relation: Be relevant.

Manner: Be perspicuous; i.e.

1. Avoid obscurity of expression. 2. Avoid ambiguity.

3. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity). 4. Be orderly.

For me, email politeness means writing to make the international e-pal feel good. In other words, Lakoff's (1973) politeness rule of "making the hearer feel good" is part of my consideration. Kachru (1999) opines that people may flout the Grice's CP for politeness sake. However, my emailing politeness rules are partly based on CP because I asked my students to do the following:

1. Make your contribution as informative as is required. It is R2: Answer all of the e-pal's questions.

2. Try to make your contribution one that is true, which is R7.

3. Relation: Be relevant. This is R3: talk about similar topics that the e-pal offered in the last correspondence.

4.Avoid obscurity of expression (refer to Liao, 1999). 5. Avoid ambiguity (ibid).

6. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity) (R6). I asked my students to write at least 500 words for each message. Superficially, it flouts the rule of "being

brief." However, I told students to increase content. We still "avoid unnecessary prolixity" if we are informative in giving more Taiwan-Chinese culture; R6 also shows its spirit.

7. Be orderly.

I asked the student groups involved in emailing in the spring of 2000 to follow the above seven of the nine rules that Grice offers.

Sacks, et al (1974) observed that the absence of speech-encoded second part of an adjacency pair "is noticeable and noticed, … people regularly complain 'You didn't answer my question' or 'I said hello, and she just walked past' (Coulthard, 1992: 70; Sobkowiak, 1997: 50)."

In homogeneous Taiwan-Chinese society, people often ask questions and receive silent answers, not valuing others’ questions as important. Moreover, when Chinese write, they ask more rhetorical questions than ENL (English as a native language) speakers (Liao, 1997), not expecting others' answers. Therefore, when American ENL e-pals answer all their questions, they feel flattered.

Do Taiwanese-Chinese leave international e-pal's questions unanswered for positive or negative face (Goffman, 1967; Brown and Levinson, 1987)? Positive face relates to the desire to be liked, appreciated and approved of by selected others, whereas negative expresses the desire to be free from imposition. It seems Taiwan-Chinese do not answer the e-pal's questions for negative face, yet they ask many questions themselves (e.g., E2). They do not like to be imposed on, but like to impose. Intuitively, Taiwan-Chinese ask personal questions to show interest in the interlocutor. Perhaps Argentine culture has trained/conditioned Maria (E1) to play fair in the emailing game. Taiwan-Chinese culture does not foster the concept of fair game.

Sifianou (1997: 71) also divides silence into the speaker- and addressee- produced silence. When a speaker thinks that what he says might damage the interlocutor's self-image, s/he decides not to do the FTA (face-threatening act); it is speaker-produced silence. For a speaker, to avoid initiating FTAs can be seen as encoding a high degree of politeness. However, the silence does more FTA than speech if the addressee fails to respond to a request or a question.

It seems that Taiwan-Chinese are more likely than Westerners to leave questions unanswered due to general Chinese personality traits. In the concluding session of ISLP (International Symposium on Linguistic Politeness) on December 9, 1999, many Thai participants raised the issue that Thai people do not listen in the wedding ceremony. Taiwan-Chinese people probably share the same tendency. They do not

listen or read carefully on many occasions, especially when the material is highly predictable, as in most kinds of ceremonies.

Kurzon (1998: 20) categorizes silence into unintentional and intentional. In email communication, sometimes interactants answer the first questions and forget later ones. This is unintentional silence. In E2, Chih-Hao did not even answer the first question.

Blum-Kulka (1991), Blum-Kulka and Sheffer (1993), Clyne (1979), Clyne, Ball, and Neil (1991), Gumperz (1982) and Tannen (1985) generally support the intercultural style hypothesis that speakers fully competent in two languages may create an intercultural style of speaking both related to and distinct from styles prevalent in the culture of their first and foreign languages. This paper also supports the hypothesis. I tried to help students understand more about cultural differences and adapt a style of speaking/writing to make international people happy. In email communication between Taiwan and Argentina, Australia, the Czech Republic, Germany and the United States, my students have their special email discourse structures, which differ from those of Taiwan-Chinese who do not receive the instructions of emailing politeness and practice.

2. The First Five Intercultural Emailing Politeness Rules

Since 1996 I have asked my students to write communicatively with international e-pals. After doing inter-email discourse analysis, I have generalized seven email politeness rules for my students to follow: (R1) offer counteranswers in the context for any questions that you ask, (R2) answer all questions asked by the e-pal, (R3) talk about the same topics as the e-pal, (R4) talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply, (R5) salute properly, (R6) do not ask questions to which your e-pal has given the answer, and (R7) do not make up stories. These rules were formed in chronological order from R1 to R7. R6 and R7 were formed in 2000, which will be discussed in Sub-study II.

In Taiwan in 1999, I presented two lectures related to this article where I asked the audience which rule, R1 or R2, was easier for Taiwan-Chinese students; each time they answered R2. Sub-studies II, IV and V will show that R1 is much easier.

Taiwan-Chinese, as well as most Orientals, have difficulty practicing R1, as when Davis (1998) warned Japanese students not to ask some personal questions. However, it is difficult to ask students to remember that some personal questions are forbidden, such as:

How old are you?

Do you have a boyfriend? Are you married?

How much do you earn each month? How many children do you have? Why don't you have a child? but it is fine to ask personal questions like:

What do you do?

How do you like your job? or How do you like Taiwan?

It would be better to change the rule of "Don't ask a certain kind of personal question" into "If you want to ask personal questions, reveal the same type of personal information about yourself in the context." For face-to-face conversation, I have changed the rule to "Reveal yourself in whatever aspect you want to know about your international friends and see if they reveal themselves in more or less the same aspect to the same degree, too. If they do not, then you ask them if it is all right to ask the question of which you just revealed yourself."

In the fall semester of 1996, I set the rule as "Don’t ask personal questions." I formulated this rule based on my EFL learning experience, recalling that my first English teacher warned us not to ask foreigners personal questions. I passed this knowledge to my students. However, my students indicated that they were only interested in these personal issues. If they were not allowed to ask such questions, they were silent. As a Taiwan-Chinese, I understand that in my homogeneous society, these personal questions are among the first ones we ask when meeting a new friend. I did not want to silence either Taiwan-Chinese or Vietnamese EFL learners (Sam, 1999). The feeling of privacy invasion from Orientals reported by Occidentals (Le 1999, for example) seems to come from the fact that Oriental people ask a lot of personal questions without revealing counteranswers.

As an intercultural researcher, I had frequent contact with ENL speakers and found that they initiated personal information while expecting me to do the same. When I did not do the same, they asked me questions to which they had already given their counteranswers. Therefore, I changed the rule of "Don't ask certain personal questions" to

R1': Provide your counteranswers first if you want to ask personal questions.

Later on, I changed it again to become R1.

R1 is easier to remember. There are two reasons for proposing R1, not R1': First, it helps students write more email content, which allows international e-pals to learn more about Taiwan and its people. Second, without considering the international e-pal who is a beginning EFL learner, my students are found to ask difficult impersonal questions, such as, "Would you tell me how the news in Germany reports the Kosovo events? Tell me some news there." R1 prevents them from asking difficult personal or impersonal questions.

EFL teaching is a kind of education as well. Education and training in intercultural communication play an important role in behavior and personal growth (Hsia, 1999). I set up R1 for changing unpleasant behavior to pleasant. Unlike Davis (1998), I do not want to inhibit my students from asking personal questions; it would be better to ask them to play the fair game by revealing themselves in the same aspect. Besides, in sharing, nothing is inappropriate.

Formation of R2. Since 1996, I have wondered whether American Anglo-Saxons are better at keeping question-answer adjacency pairs than people of any other ethnicity. In E1, Maria gave counteranswers to three questions she asked; however, Chih-Hao did not answer them. Though Maria originally did not mean to write to him, I thought anyone requested to reply for Winnie ought to answer those questions, as Maria had given counteranswers. Chih-Hao's email contents were influenced by his communicative competence in Taiwan-Chinese society.

My students often, if not usually, did not answer e-pals' questions. When I read their correspondence letters in chronological order, I felt embarrassed and thought, "If I were the international e-pal, I would be disappointed and frustrated by the silence." Therefore, I produced R2: Answer all questions asked by the e-pal. Chang (1992: 548) also mentioned a similar problem that coincided with the reason for R2, indicating an American student expressed disappointment with her Taiwan-Chinese e-pal who

wrote a rather formal autobiography rather than respond directly to her questions (emphasis mine). Taiwan-Chinese students are generally moved by the fact

that their American e-pals always read their email carefully and answered all their questions (Liao, 2000). By contrast, they felt Taiwan-Chinese were not so careful in reading letters and did not care if they answered e-pal's questions. They are more eager to share other things.

Formation of R3 was partly derived from Tannen (1990), who proposes that one's conversational topics are one of the following: (1) the same as the interlocutor's; (2) answering questions; and (3) asking questions based on what the interlocutor said. The five rules might be easy for American ENL speakers. Without checking their

validity with native Mandarin/Taiwanese speakers, we might say, "Yes, the aforementioned five rules are ordinary conversational rules."

Taiwan-Chinese students, like German ones (Liao and Wolf, 2000), may not get used to talking on the same topic as the e-pal (refer to E2, where Chih-Hao did not talk on the same topics as Maria.) They, however, frequently ask personal questions, which may not be based on what e-pals have written, but on what interests them and on intuition as Taiwan-Chinese talking in their homogeneous society. Chih-Hao's email brings to mind the tragicomedy of Waiting for Godot (Beckett, 1954), in which Estragon and Vladimir engage in incoherent conversation. The play is generally categorized as absurd, yet when viewed from the standpoint of daily Chinese conversation, it is realistic.

R4 may be implied by E2 as easy for Taiwan-Chinese. Actually, many Taiwan-Chinese complain that they do not know what to talk about; therefore, I assign the weekly topic to enable the EFL learners to talk about a little bit of everything. Then they complain that they are not interested in the weekly topic. I comfort them, saying that they need to be accustomed to the practice because they cannot choose topics when they attend an EFL writing test or contest. In daily conversation, they are not always able to choose their own topics either.

Another reason for R4 is that international e-pals have a heavy burden to find new topics to talk about if an interlocutor only follows R2 and R3 in the body of the letter. Had Chih-Hao only answered her questions and talked about counterpoints Maria had covered, Maria would have always had the burden of finding some new subject, difficult for a nine-year-old or even older people.

R5 was formulated in the spring semester of 1999, when 80% of a class of 40 students failed to change the salutation of "Dear e-pal" for the introductory letter to an unspecified e-pal to "Dear <specific name>" in later letters, which caused the teacher of the international e-pals not to allow her students to reply.

3. Five Experimental Studies

Five experimental Sub-studies were done: I and II (December 1999), III (February 2000), IV and V (May 29 through June 2, 2000).

3. 1 Sub-study I

On December 22, 1999, eight subjects at Feng Chia University (FCU) had learned the first five politeness rules, but had difficulty practicing them. They read E1 and E2 together in class to find that Chih-Hao did not answer Maria's questions and

offered counteranswers to only three of his own. He did not follow R1 or R2 well. As homework, they answered the two questions (Q1: How do you like E2? And Q2: Why do you think that Chih-Hao did not answer Maria's questions? Please don't say that he was not good at following the five email politeness rules. Use your intuition as a Taiwan-Chinese) and re-wrote E2, using their own data for the missing part, to meet R1 and R2.

The answers, translated into English by me, to Q1 are: He neither answered Maria's questions nor offered counteranswers to two of his own questions. Anyone who received E2 would be frustrated (A1, male). He wrote a good letter. A very minor defect is that he asked a lot of questions in succession. Besides, he did not offer all counteranswers. This made me feel that he was not polite (A2, female). The contents of his reply were unrelated to Maria's letter. Basically, Maria self-introduced her own age, birthday, family members, and pet. Chih-Hao should have done the same (A3, f). I like his reply. Though he did not pay attention to politeness rules, he was zealous in talking about himself. He was sincere. He wrote a good reply (A4, f). Chih-Hao only talked about the part that he wanted Maria to know. He neglected all others. Actually, the five politeness rules are very basic; they should not be restricted to EFL email writing. We learned this kind of basic politeness rules in grade school. However, the Taiwan educational system does not focus on practice. Many people have forgotten the elementary etiquette (A5, m). If I were Maria, I would feel unhappy about the reply. He was talking about his own topics. I could not get what I wanted (A6, f). Chih-Hao was careless about answering Maria's questions. He put all questions at the end of a letter, giving the reader a sense of being questioned. Though he did not answer Maria's questions, Chih-Hao at least said something about himself (A7, f). He did not read Maria's letter carefully (A8, f).

The answers to Q2 are: He read the letter without replying immediately. When replying, he did not re-read it. Or he might be devoted to writing about himself and forgot to answer the questions (A1, m). Maria wrote a very clear letter, but Chih-Hao talked about his own topics. This made me feel Maria was not respected (A2, f). Chih-Hao mentioned his age, major, and interests, then asked a lot of questions. He only mentioned what he liked and ignored Maria (A3, f). Taiwan-Chinese generally do not read email carefully. If we get a reply, any reply, we are happy, so we are likely to ignore e-pals' questions (A4, f). When he replied, he did not put Maria's letter at the computer. Taiwan-Chinese students' English is generally poor. They are writing and thinking about diction, grammar and they forget the contents of incoming email. Another possibility is that he does not want to talk about his sad family story (A5, m).

The three questions might have been boring for him. Owing to Taiwan-Chinese culture, he may have thought Maria asked the three questions for politeness only. She did not really want to know the answer. He might not have noticed that Maria asked questions (A6, f). Chih-Hao might not have read through the letter. He did not know that Maria asked him questions, which might let Maria feel disrespected. It is very unlikely that Chih-Hao did not know the answers (A7, f). He did not read the letter carefully. The three questions should have been easy (A8, f).

Only A4 gave positive answers to Chih-Hao's behavior. A2 did not say that E1 and E2 form an absurd and incoherent inter-email discourse, but said that E1 was not respected. I share A6's interpretation that it is the Taiwan-Chinese mind at the subconscious level. In the two previous related speeches, some informants agreed that Chinese people are more self-centered than Westerners. Sub-study II was done one week after Sub-study I.

3.2 Sub-Study II

I wanted to understand how many Taiwan-Chinese are good readers (or listeners in the counterspeech context). A second group of 77 FCU students (49 male, 28 female), none attending Sub-study I, were asked to write a reply to E1. They were told that this was a practice to see if they wrote good email; later, they would be given an international e-pal, which came true in February, 2000.

Table 1 shows that the 49 males were asked a total of 147 (= 3 x 49) questions, 99 of which (67.3%) they answered. Twenty-five (51%) of the 49 males answered all three questions.

Table 2 shows that the females answered 56 (66.7%) of the 84 (=3 x 28) questions; eleven of them (39.3%) answered all questions. Comparing Tables 1 and 2, we find that more males than females were careful readers (51% to 39.3%) because more males answered all Maria's questions. However, Table 3 shows that they were not significantly different (the p-value being 0.321).

Table 1: How many of Maria's questions were answered by males?

Total: M1: 3/3 M2: 3/3 M3: 3/3 M4: 0/3 M5: 0/3 M6: 0/3 M7: 3/3 M8: 0/3 M9: 3/3 M10: 1/3 M11: 3/3 M12: 2/3 M13: 2/3 M14: 1/3 M15: 3/3 M16: 1/3 M17: 3/3 M18: 3/3 M19: 3/3 M20: 1/3 M21: 3/3 M: 99/147 M22: 3/3 M23: 1/3 M24: 1/3 M25: 3/3 M26: 2/3 M27: 2/3 M28: 3/3 M29: 1/3 M30: 0/3 M31: 1/3 M32: 2/3 M33: 3/3 M34: 3/3 M35: 2/3 M36: 3/3 M37: 3/3 M38: 3/3 M39: 0/3 M40: 3/3 M41: 1/3 M42: 0/3 3/3: 25/49 M43: 3/3 M44: 3/3 M45: 2/3 M46: 1/3 M47: 3/3 M48: 3/3 M49: 3/3

Table 2: How many of Maria's questions were answered by females? Total: F1: 3/3 F2: 1/3 F3: 2/3 F4: 3/3 F5: 3/3 F6: 1/3 F7: 2/3 F:56/84 F8: 3/3 F9: 2/3 F10: 3/3 F11: 0/3 F12: 2/3 F13: 2/3 F14: 2/3 F15: 3/3 F16: 1/3 F17: 2/3 F18: 1/3 F19: 3/3 F20: 3/3 F21: 3/3 3/3: 11/28 F22: 1/3 F23: 1/3 F24: 3/3 F25: 0/3 F26: 3/3 F27: 2/3 F28: 1/3

Table 3: Were males and females significantly different in keeping the Q-A adjacency pairs?

Males Females Total

Answered all questions 25 (51.02%) 11 (39.29%) 36 (46.75%)

Not all 24 (48.98%) 17 (60.71%) 41 (53.25%)

Total 49 (63.64%) 28 (36.36%) 77 (100%)

Chi-square value= 0.986 (p-value= 0.321)

3.2.1 Asking unnecessary questions

Reading those 77 letters, I found that except for the fact that 41 subjects (53.3%) did not answer all three questions, they showed one more clue of carelessness: twelve (seven men and five women; 15.6%) asked unnecessary questions because Maria had given the answer in E1.

The questions they asked were: M4: Do you have a dog?

M8: How old are you? M8: What is your sport?

M12: Who are your family members? M14: When is your birthday?

M27: Do you speak Spanish? Why do you like Spanish. M32: When is your birthday?

M32: Who are your family members?

M48: Who are your family members? M48: Have you got a pet?

F2: Who are your family members? F6: Who are your family members? F11: What's your name?

F11: What's your favorite sport? F18: When is your birthday?

F22: Who are your family members?

3.2.2 Creative Writing

I am sure none of the 77 students knew who Winnie was. However, there were still four men (M4, M15, M16, and M19), no women, who pretended to be Winnie's best friends. Since 1996, I have found that students give contradictory data in two messages. Grice's CP maxims are for testing speakers' co-operation. My rules are also for testing if Taiwan-Chinese are sincere, honest, informative and concerned (or making the e-pal happy by not privacy-intruding and refusing to answer questions). R6 and R7 were formed after Sub-study II.

3.2.3 How well did they follow emailing politeness rules?

different in keeping the Q-A adjacency pairs; that is, 53.25% flouted R2. Now we check how they followed the other five rules (excluding R5, not applicable because I offered the first part of the letter):

Dear Maria,

Winnie is not here. I write for her from now on. My name is…

Table 4 shows university females and males did not significantly differ in following R1: offer counteranswers in context for any questions that you ask; that is, 5.49% of them flouted it. All the questions they asked are personal ones.

Table 4: How university students followed R1

Yes Not applicable No Total

Males 13 (26.53%) 32 (65.31%) 4 (8.16%) 49 Females 9 (32.14%) 18 (64.29%) 1 (3.57%) 28 Total 22 (28.57%) 50 (64.94%) 5 (5.49%) 77

Chi-square value = 0.778 (p-value = 0.678)

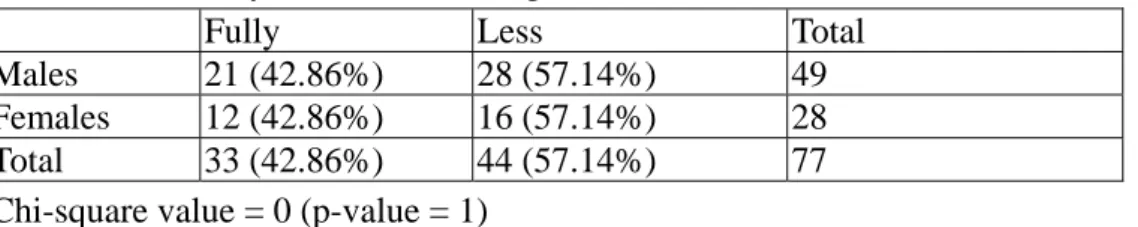

Table 5 shows that 57.14% of the university females and males flouted R3: talk on the same topics as the e-pal. Chinese students are often not used to talking about the same topic as the interlocutor. At the beginning stage of encountering people, they are more used to show admiration for the interlocutor, such as, "You can swim. I admire you… Wow, you can also speak Spanish…"

Table 5: University students following R3

Fully Less Total

Males 21 (42.86%) 28 (57.14%) 49

Females 12 (42.86%) 16 (57.14%) 28

Total 33 (42.86%) 44 (57.14%) 77

Chi-square value = 0 (p-value = 1)

Table 6 proves significantly more women than men (92.86% to 51.02%) talked about something new to facilitate e-pals' replies; men have more difficulty initiating new topics and need more help from EFL teachers offering weekly topics. Many researchers (e.g., Fishman, 1978; Tannen, 1984; West and Garcia, 1988; DeFrancisco,

1991) also find that women tend to raise more topics than men in personal conversation.

Table 6: How university students followed R4

Yes No Total

Males 25 (51.02%) 24 (48.98%) 49

Females 26 (92.86%) 2 (7.14%) 28

Total 51 (66.23%) 26 (33.77%) 77

Chi-square value = 13.945 (p-value = 0.000)

Table 7 indicates university men and women were not significantly different; 15.58% of them flouted R6: Do not ask questions which a key pal has answered.

Table 7: How university students followed R6

Follow Not follow Total

Males 42 (85.71%) 7 (14.29%) 49

Females 23 (82.14%) 5 (17.86%) 28

Total 65 (84.42%) 12 (15.58%) 77

Chi-square value = 0.173 (p-value =0.678)

From Tables 3 to 7, we find that the six rules flouted from the highest frequency (i.e., most difficult to follow) to lowest are:

1. R3: Talk about the same topic as the e-pal (57.14%) 2. R2: Answer all the e-pal's questions (53.25%)

3. Talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply (33.77%); males especially bad in finding new topics to talk about.

4. Do not ask questions to which the e-pal has given the answer (15.58%) 5. Offer counteranswers in context for any questions that you ask (6.49%) 6.Do not make up stories (5.2%).

3.3 Sub-study III

I had the chance to go back to the 77 students who offered data for Sub-study II. To obtain reasons, I randomly chose 19 (ten males and nine females–originally I chose 10 females, one being absent) of those who gave incomplete answers to Maria's questions and/or asked unnecessary questions. I typed my questions on the back of their letter sheets for Sub-study II, asked them to answer in Chinese, and told them that they were to do a psychology test to understand more about themselves. Eight

females and nine males indicated they forgot that there was such a question or they did not answer: "I thought I had answered all the questions," "I did not neglect the questions intentionally," "I forgot that she mentioned her birthday," "I did not have a pet, so I ignored the question," "I ignored those questions. I am sorry for that," "I did not read the letter carefully," and "I don't know why; perhaps I did not pay attention to her questions."

One female indicated that she felt uneasy to tell a first-time encounter her birthday. A male said it was his first time writing to her and he did not want to answer the personal question of "When is your birthday?" Family members were not important, so he did not answer it. He did not have any pet and decided not to answer it. Chinese lack the concept of offering counter or equal information. Even though Maria revealed her birthday, they still felt that it was a personal question and did not want to answer. For the groups involved in cross-cultural emailing, the 'fair game' in giving and taking information should be emphasized.

3.4 Sub-studies IV and V

In two informal situations, I talked about Sub-studies I to III with my colleagues. They suggested that I do the research in Chinese because Taiwanese-Chinese might be struggling with their EFL grammar and diction and could not take good care of the E1 contents. I decided to ask some students, aged 14, at Tongshan Junior High School, in Taichung City, to do Sub-studies IV and V. For Sub-study IV, I changed the salutation line of E1 to "Dear E-pal in Taiwan" from "Dear Winnie" and asked 20 girls and 15 boys to write English replies.

For Sub-study V, I translated the English letter to Chinese with little change in contents (shown as E1''), asking 25 girls and the same number of boys to reply in Chinese. Thanks go to Ching-chu Chiu, who gave her students 25 minutes for either Sub-study IV or Sub-study V. Those who wrote the English reply did not do Sub-study V and vice versa.

E'' (Chinese) 臺灣的筆友,你好, 我的名字是瑪麗亞•奧古斯稊那. 我是女孩子,今年九歲,我的生 日是五月二十五日。你的生日是甚麼時候? 我住在阿根廷,我正在學中國話。我喜歡西班牙語。我英語說得不好。 我有三個姊姊,一個爸爸,一個媽媽。 你呢?你養寵物嗎?我有一隻 狗。我最喜歡的運動是游泳。再見。 瑪麗亞•奧古斯稊那敬上

E" (English)

Dear E-pal in Taiwan,

How are you? My name is Maria Agustina. I am a nine years old girl. My birthday is on May 25th. When is your birthday?

I live in Argentina and I am learning Chinese. I like Spanish. My English is not good. I have got three sisters, a father and a mother. And you? Have you got a pet? I have got a dog. My favourite sport is swimming.

Bye!

Maria Agustina

Purpose of Sub-studies IV and V was to check if junior high school students behaved differently in writing English and Chinese concerning the first six rules. I could not check how they followed R7, because I had no way of knowing that they made up stories.

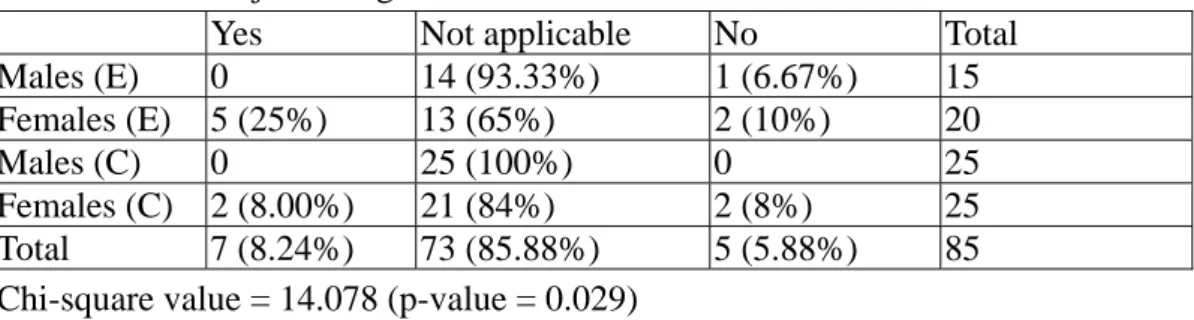

Table 8: How the junior high school students followed R1

Yes Not applicable No Total

Males (E) 0 14 (93.33%) 1 (6.67%) 15

Females (E) 5 (25%) 13 (65%) 2 (10%) 20

Males (C) 0 25 (100%) 0 25

Females (C) 2 (8.00%) 21 (84%) 2 (8%) 25

Total 7 (8.24%) 73 (85.88%) 5 (5.88%) 85

Chi-square value = 14.078 (p-value = 0.029)

Concerning R1 (offer counteranswers in context of any questions you ask), the Chi-square value of 14.078 and the p-value of 0.029 (Table 8) imply that one group of females or males in Chinese or English responses is different from another. I checked the cells and decided to combine "Yes" and "Not applicable" categories into "Not flouting the rule", and the "No" category became "flouting". Table 8.1 shows that junior high school males and females are not significantly different: 5.88% of them flouted the rule.

Table 8.1: How junior high school students followed R1

Not flouting Flouting Total

Males (E) 14 (93.33%) 1 (6.67%) 15 Females (E) 18 (90%) 2 (10%) 20 Males (C) 25 (100%) 0 25 Females (C) 23 (92%) 2 (8%) 25 Total 80 (94.12%) 5 (5.88%) 85 Chi-square value = 2.394 (p=0.495)

Table 9: How junior high school students followed R2

Yes No Total Males (E) 10 (66.67%) 5 (33.33%) 15 Females (E) 15 (75%) 5 (25%) 20 Males (C) 18 (72%) 7 (28%) 25 Females (C) 21 (84%) 4 (16%) 25 Total 64 (75.29%) 21 (24.71%) 85 Chi-square value = 1.766 (p=0.622)

Table 9 shows junior high school boys and girls do not differ significantly in writing English or Chinese replies; 24.71% flouted R2, and they did not answer all three questions.

Concerning R3 (talk about the same topics as the e-pal), Table 10 shows 14-year-old boys and girls are not significantly different in either English or Chinese replies; 31.76% talked less compared with what Maria had talked about.

Table 10: How junior high school students followed R3

Fully Less Total

Males (E) 10 (66.67%) 5 (33.33%) 15

Females (E) 13 (65%) 7 (35%) 20

Males (C) 18 (72%) 7 (28%) 25

Females (C) 17 (68%) 8 (32%) 25

Total 58 (68.24%) 27 (31.76%) 85

Chi-square value = 0.278 (p-value = 0.964)

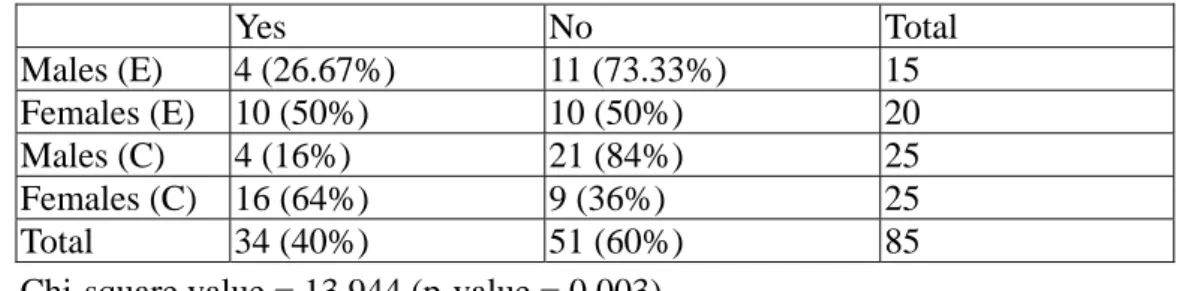

Table 11: How junior high school students followed R4

Yes No Total Males (E) 4 (26.67%) 11 (73.33%) 15 Females (E) 10 (50%) 10 (50%) 20 Males (C) 4 (16%) 21 (84%) 25 Females (C) 16 (64%) 9 (36%) 25 Total 34 (40%) 51 (60%) 85

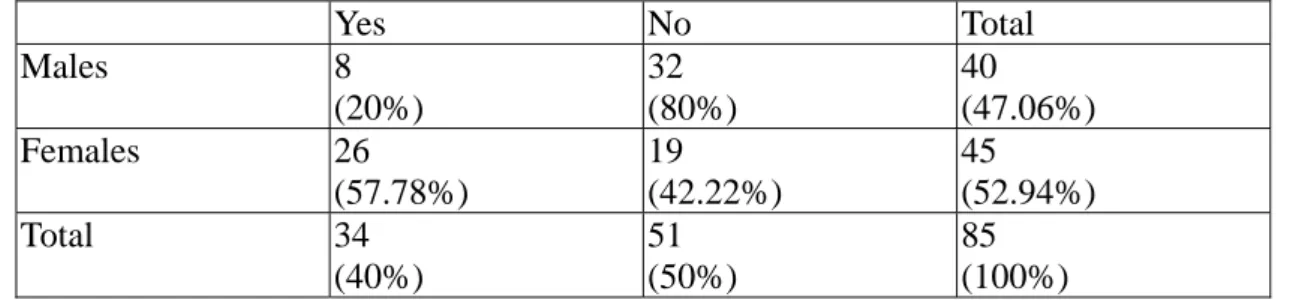

Table 11.1 How junior high school students followed R4 Yes No Total Males 8 (20%) 32 (80%) 40 (47.06%) Females 26 (57.78%) 19 (42.22%) 45 (52.94%) Total 34 (40%) 51 (50%) 85 (100%) Chi-square value = 12.593; p-value=0.000

The Chi-square value of 13.944 and p-value of 0.003 shown under Table 11 indicate at least one row differing significantly from another in following R4 (talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply). I compared the meaningful pairs of Males (E) and Males (C) and found that they were not significantly different (Chi-square value 0.667, p-value 0.414). The test of Females (E) and Females (C) also shows no significant difference (Chi-square value 0.893 and p-value 0.345). Comparison of students writing in English (14: 21) and Chinese (20:30) letters shows that the two groups are not significantly different: 40% of them talked on some new topics, 60 % did not. Now, it seems that the significant difference must be in females versus males. Table 11.1 shows that significantly more females than males are able to talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply (57.78% to 20%) in both Chinese and English. This phenomenon is similar to that shown in Table 6 (university women are abler than men to talk on new topics).

Table 12: How they followed R5: Salute properly

Yes No Total Males (E) 13 (86.67%) 2 (13.33%) 15 Females (E) 19 (95%) 1 (5%) 20 Males (C) 17 (68%) 8 (32%) 25 Females (C) 24 (96%) 1 (4%) 25 Total 73 (85.88%) 12 (14.12%) 85

Chi-square value = 10.083 (p-value = 0.018)

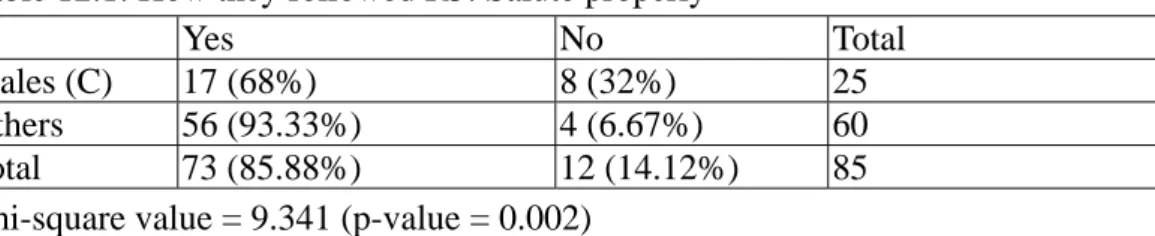

Chi-square value of 10.083 and p-value of 0.018 in Table 12 show that at least the frequency distribution of one row is significant different from that of another. Again, I tested Males (E) and Males (C) to find a Chi-square value of 1.742 and p-value of 0.187–i.e., no significant difference. The test of Females (E) and Females (C) yields similar results (Chi-square value 0.026, p-value 0.872). Viewing the four rows again, I believed a significant difference could exist in Males (C). Hence the

other rows were pooled to compare with Males (C). Table 12.1 shows that indeed when junior high school males wrote in Chinese, significantly more forgot to salute properly; 32% just began the letter with "My name is…". One Chinese politeness rule is that people need to address each other appropriately; our data support Holmes’ (1995) finding that Taiwanese females are generally more polite than males of the same age group.

Table 12.1: How they followed R5: Salute properly

Yes No Total

Males (C) 17 (68%) 8 (32%) 25

Others 56 (93.33%) 4 (6.67%) 60

Total 73 (85.88%) 12 (14.12%) 85

Chi-square value = 9.341 (p-value = 0.002)

Finally, none of these 85 students flouted R6 by asking unnecessary questions. Junior high children read more carefully than university freshmen. For junior high school students, the five rules from the most difficult to the least are:

1. Talk about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply (Table 11: flouting rate 60%)

2. Talk about the same topics as the e-pal (Table 10: 31.76%) 3. Answer all questions asked by the e-pal (Table 9: 24.71%) 4. Salute properly (Table 12: 14.12%)

5. Offer counteranswers to the questions you ask (5.88%)

4. Conclusion

Comparing Tables 4 and 8.1, we find university and junior high school students manifesting similar communicative competence in following R1 (offer counteranswers to whatever questions you ask); 5.49% and 5.88% of them, respectively, flouted it.

Comparing Tables 3 and 9, we (readers and I) find that junior high school students better at keeping Q-A adjacency pairs than university students (24.71% to 53.25%). Reading their replies at one sitting, I felt that the reply letters were so easy for university students because of their linguistic competence in English that they talked about whatever they wanted to without reading E1 carefully. Another reason is that university students had experienced four more years of ritualized interpersonal interaction in relatively homogeneous Taiwanese society; they felt people ask questions for ritual sake and were not really interested in answers, so they did not

bother themselves to answer the three questions. Junior high school students followed R2 so well because their English abilities were not very good; some used Maria's letter as a kind of guided composition. Yet they did not repeat her questions, while 15.6% of the university students did. Table 13 shows that university and junior high school students differ significantly.

Table 13: Comparing university students and junior high school ones in R2

Answered all Qs Not all Total

University 36 (46.75%) 41 (53.25%) 77 (100%)

Junior High School 64 (75.29%) 21 (24.71%) 85 (100%)

Total 100 (61.73%) 62 (38.27%) 162 (100%)

Chi-square value =13.931; p-value = 0.000

Table 14 compares Tables 5 and 10 to prove junior high school students better at talking about the same topics with e-pals than university students. This is related to linguistic competence: university students felt it easy to reply and wrote whatever they wanted without revealing similar information about themselves.

Table 14: Comparing university students and junior high school ones in R3

Fully Less Total

University 33 (42.86%) 44 (57.14%) 77 (100%)

Junior High School 58 (68.24%) 27 (31.76%) 85 (100%)

Total 91 (56.17%) 71 (43.83%) 162 (100%)

Chi-square value =10.569; p-value = 0.001

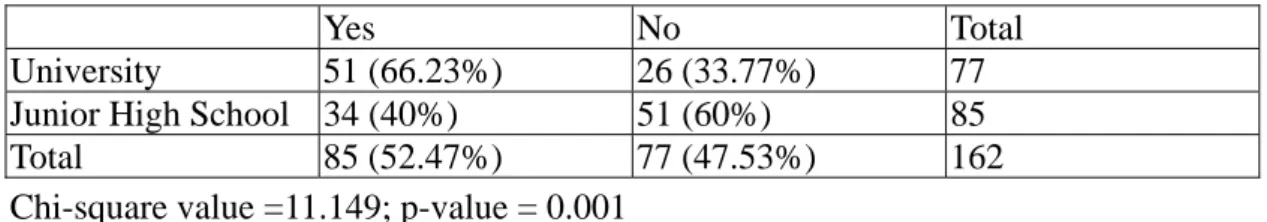

Tables 6 and 11.1 show that males and females in both age groups were significantly different, with females better in talking about something new to facilitate the e-pal's reply. Table 15 compares Tables 6 and 11.1. University students outdid junior high school ones in finding new topics to talk about.

Table 15: Comparing university students and junior high school ones in R4

Yes No Total

University 51 (66.23%) 26 (33.77%) 77

Junior High School 34 (40%) 51 (60%) 85

Total 85 (52.47%) 77 (47.53%) 162

Chi-square value =11.149; p-value = 0.001

worse at R2, R3, and R6. They are about the same good/bad in R1: fewer than 6% asked personal questions without revealing their own answers first. Why do Western scholars, such as Davis (1998) and Le (1999), complain that Orientals often invade privacy and suggest them not to? The reason might be that privacy intrusion is so strongly marked for Western people that privacy intrusion of one single person among 100 is annoying enough. Our study shows that among one hundred people, there were about six who do. Avoiding answering questions is not very marked; people feel frustrated only when they are in desperate need of an answer–e.g., a student required to obtain the answer.

R1 and R7 are good for the introductory letter. From the second letter on, all seven rules are useful. From Sub-Study I, we have found that Taiwan-Chinese generally are not happy with a peer's way of asking too much and not giving answers. Education–EFL teaching here–should modify their behavior, especially in the international arena when intercultural differences are expected. If we ask our students to provide counteranswers first in asking questions, they serve as a model to offer phrases and words for international EFL/ESL e-pals, especially beginning learners. This both prevents them from asking difficult questions and protects them from the accusation of being selfish (Liao, 1999); it also provides a hint to international e-pals regarding the extent they must answer. If they want a detailed answer, they need to provide their own answers in the same depth.

In intercultural communication, it is always the ones who know intercultural differences to adjust themselves to the ones who do not, rather than vice versa.

References

Beckett, Samuel. 1954. Waiting for Godot: Tragicomedy in 2 Acts. New York: Grove Press.

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1991. Interlanguage Pragmatics: The Case of Requests. In R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith, and M. Swain. Eds.

Foreign/Second Language Pedagogy Research. 255-272. Clevedon and

Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters.

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana and Hadass Sheffer. 1993. The Metapragmatic Discourse of American-Israeli Families at Dinner. In Kasper, Gabriele and Shoshana Blum-Kulka. Eds. 196-223.

Brown, Penelope and Stephen Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in

Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Canal, M. 1983. From Communicative Competence to Communicative Language Pedagogy. In Richards and Schmidt. Eds. Langauge and Communication. London: Longman.

Canal, M. and M. Swain. 1980. Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Applied

Linguistics. 1.1, pp. 1-47.

Chang, Ye-ling. 1992. Contact of the Three Dimensions of Language and Culture: Methods and Perspectives of an Email Writing Program. The Proceeding of the

Eighth Annual Convention of the English Teacher’s Association in R.O.C. Pp.

541-562.

Clyne, M. 1979. Communicative Competences in Contact. ITL. 43. 17-37.

Clyne, M., Ball, M., and Neil, D. 1991. Intercultural Communication at Work in Australia: Complaints and Apologies in Turns. Multilingua. 10. 251-273.

Coulthard, Malcolm. 1992. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis. (2nd edition.) London: Longman.

Curzon, Dennis. 1998. Discourse of Silence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Davis, Randall S. 1998. Captioned Video: Making it Work for You. The Internet TESL

Journal. 4(3). Available at

http://www.aitech.ac.jp/~iteslj/Techniques/Davis-CaptionedVideo/

DeFrancisco, Victoria L. 1991. The sounds of silence: how men silence women in marital relations. Discourse and Society. 2, 4: 413-23.

397-406.

Fishman, Pamela M. 1983. Interaction: the work women do. In Barrie Thorne, Cheris Kramarae and Nancy Henley. Eds. Language, Gender and Society. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House. Pp. 89-101.

Grice, H. P. 1975. Logic and Conversation. In P. Cole and J. L. Morgan. Eds. Syntax

and Semantics. Vol. 3: Speech Acts. New York: Academic Press. Pp. 41-58.

Gumperz, J. J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Holmes, Janet. 1995. Women, Men and Politeness. London and New York: Longman. Hongladarom, Krisadawan and Soraj Hongladarom. Politeness Ideology in Thai

Computer-Mediated Communication. Paper presented at International Symposium on Linguistic Politeness. Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. Thailand. December 7-9.

Horton, Mark and Gene Spafford. 1993. Rules of Usenet Conduct. Part of a series of documents compiled and distributed by Gene Spafford 1992/93 in news.announce.newusers.

Hsia, Chung-shun. 1999. Small Group-Discussion in EFL and Culture Learning. Paper presented at the International Conference on ESL/EFL Literacies in the Asia-Pacific Region. Tunghai University. December 4-5.

Hymes, D. 1974. Foundations in Sociolinguistics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Jaworski, Adam. 1997. Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Mouton de Gruyter. Kachru, Yamuna. 1999. Politeness Across Cultures. Focus Lecture presented at

International Association for World Englishes. Tokyo, July 30.

Kasper, Gabriele and Shoshana Blum-Kulka. Eds. 1993. Interlanguage pragmatics: An introduction. Interlanguage Pragmatics. New York: Oxford University Press. Lakoff, Robin. 1973. The Logic of Politeness: or Minding your P's and Q's. In Papers

from the Ninth Regional Meeting of Chicago Linguistic Society. Pp. 292-305.

Le, Mark. 1999. Privacy: Intercultural Problems. Paper presented at ISLP. Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. Thailand. December 7-9.

Levinson, Stephen C. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1994. A Study on the Strategies, Maxims, and Development of

Refusal in Mandarin Chinese. Taipei: Crane.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1997. Understanding cultural differences from disparity of Chinese and English version of The Story of The Stone and the implication in MFL/EFL teaching: A sociopragmatic viewpoint. Presented at The First Translation Conference, National Taiwan Normal University. March 22-23.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1999. E-mailing to improve EFL learners' reading and writing abilities: Taiwan experience. The internet TESL journal. 5(3). Available at http://www. aitech.ac.jp/~iteslj/.

Liao, Chao-chih. 2000. Intercultural Emailing. Taipei: Crane.

Liao, Chao-chih and Hans-Georg Wolf. 2000. E-mail Discourse Structure and Cross-cultural Understanding between Taiwan and Germany. Studies in English

Language and Literature. No. 7. National Taiwan University of Science and

Technology. Taipei, Taiwan. Accepted.

Lii-Shih, Yu-hwei E. 1987. Conversational Politeness and Foreign Language

Teaching. Taipei: Crane.

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A Simplest Systematics for Organization of Turn-Taking in Conversation. Language 50: 696-735.

Schegloff, E.A. and Sacks, H. 1973. Opening up Closings. Semiotica, 7.4, 289-327. Sifianou, Maria. 1997. Silence and Politeness. In Adam Jaworski (ed). Pp. 63-84. Sobkowiak, Wloodzimierz. 1997. Silence and Markedness Theory. In Adam Jaworski

(ed). Pp. 39-61.

Tannen, Deborah. 1984. Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Tannen, Deborah. 1985. Silence: Anything but. In Deborah Tannen and Muriel Saville-Troike (eds), 93-111.

Tannen, Deborah. 1990. You Just Don't Understand. New York: Ballatine Books. Tannen, Deborah and Muriel Saville-Troike. Eds. 1985. Perspectives on Silence.

Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

West, Candace and A. Garcia. 1988. Conversational shift work: a study of topical transitions between women and men. Social Problems 35, 5: 551-575.

逢甲人文社會學報第 1 期 第 229-253 頁 2000 年 11 月 逢甲大學人文社會學院