Mainland China’s Diplomatic

Maneu-ver in Central America: The Impact

of the Nicaragua Grand Canal

Chung-chian Teng

Distinguished Professor, Department of Diplomacy National Cheng-chi University

Abstract

The leftist Sandinista government signed an agreement with Hong Kong-based HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Company (HKND) to initiate the construction of the Nicaragua Grand Canal within five years. It has been described as a milestone in the history of Central America. This great project will transform not only the landscape of this region but also the geopolitical and geoeconomic power configuration.

It has been discussed widely that Beijing is behind the scenes of the canal project, because Wang Jing, the owner of HKND, has no civil engineering background or experience, not to mention the ability to obtain the necessary capital.

In this study, the main objective is to gain a comprehensive understanding about the mainland China and Latin American rela-tionship, along with mainland China’s grand strategy and diplomacy in this region. Then, the analysis of the Nicaragua Great Canal project will be done to know the pros and cons of the canal as well as the

position of mainland China. In view of Central America traditionally being seen as America’s backyard, the U.S. policy toward Latin America and Central America is examined and observed to see its impact.

Although mainland China has not mentioned Latin America and Central America in its “One Belt, One Road” strategy, the geopolitical and geoeconomic importance of Latin America and Central America cannot be ignored. With the creation of three international financial institutions (i.e., New Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure In-vestment Bank, and Silk Road Fund Company), mainland China is able to promote critical infrastructure construction projects around the world, the Nicaragua Grand Canal must be one of them.

In conclusion, it is predictable that, with the strong support of the Nicaraguan government and mainland China’s grand strategy, the Nicaragua Grand Canal will be finished sooner or later. Mainland China will benefit from the completion of the canal and hold a better geo-strategic position in the region and in the world.

Keywords: Mainlan China, U.S., Central America, Nicaragua Grand

Canal, Diplomatic Maneuver

I. Introduction

In the history of Nicaragua, one of the poorest countries in Latin America, the first Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) project, the Nicaragua Grand Canal, was officially sealed in June 2013. It is argued that “This will be the largest project in Latin America in 100 years and is going to be a transformational project not only for Nicaragua but for the region.”1With very rapid process to award a huge project to

strong protests in Nicaragua. Many critics view the role of Beijing in this project with suspicion. They are afraid that the sovereignty of Nicaragua might be compromised by this deal. No matter whether the national government is behind the scenes of the Nicaragua Grand Canal, mainland China’s presence in Latin America has attracted a lot of academic attention and research.

The facts are that Nicaragua maintains diplomatic relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan and there exists a diplomatic truce between mainland China and Taiwan. Is Chinese authority conceiving plots and actions to penetrate into the rest of Central America, to re-start diplomatic games with Taiwan, or both? Does the joint Nicaragua Grand Canal project match mainland China’s grand strategy in Latin America and in the world? What is the reaction from the United States to mainland China’s activities in general and the pending canal project in particular?

Under these circumstances, it is important to study Beijing’s strategy and policy in this area and the possible impact of the con-struction of the Nicaragua Grand Canal. In this paper, the American factor also will be touched upon, because of the critical role of the U.S. government in Latin America, especially after the announcement of normalization between the United States and Cuba.

II. Mainland China in Latin America: Resources

Diplo-macy and Beyond

Entering the 21st Century, scholars and practitioners in China’s

Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama Canal,” The Guardian, June 12, 2013, <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/12/nicaragua-canal-waterway-panama>.

affairs have applied ‘resources diplomacy’ to describe mainland China’s foreign policy behavior in Latin America. It is apparent that mainland China has been seeking natural resources and foodstuffs for sustainable economic development around the world, especially in developing countries. With abundant foreign exchange reserves, mainland China is in an advantageous position to conduct campaigns for its urgent needs.

1. South-South Cooperation

Fully aware of the negative image of colonialism/neo-colonialism, mainland China has adopted a cautious path in approaching developing countries. One critical option is to positively advocate ‘South-South Cooperation,’ focusing more on assisting genuine development there. ‘South-South Cooperation’ means not only, passively speaking, the prevention of the economic exploitation and political subordination of the South by the North, but also, actively speaking, the provision of capital and technology transfer by the relative “have” country for assisting indigenous development of the “have-not” ones. When in-teracting with the Latin American nations, mainland China certainly would like to adopt a ‘South-South Cooperation’ model.

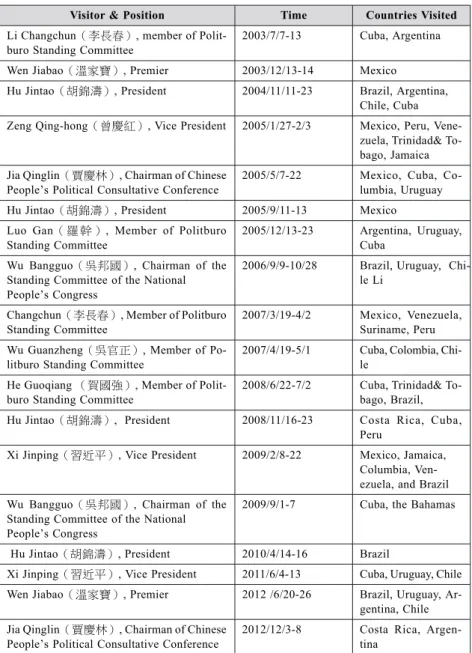

To implement resources diplomacy, intervention from the state or the government is necessary, and the state leads and coordinates a variety of resources. At the same time, the state also plays the role of directing resources to people who need them. It goes without saying that high-level diplomacy is a critical part of the function of the state. During the Hu Jintao era, the eminent position of Latin America in mainland China’ s foreign relations could be understood through the high frequency of visits made by the inner circle of Chinese decision-making (i.e. members of Politburo Standing Com-mittee of the Chinese Communist Party) (see Table 1 & Table 2). From 2003 to 2012, they made eighteen visits. Even since the beginning

Table 1: Official Visits by PRC Leaders to Latin America: Hu Jintao Era

Visitor & Position Time Countries Visited

Li Changchun(李長春), member of Polit-buro Standing Committee

2003/7/7-13 Cuba, Argentina Wen Jiabao(溫家寶), Premier 2003/12/13-14 Mexico

Hu Jintao(胡錦濤), President 2004/11/11-23 Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Cuba Zeng Qing-hong(曾慶紅), Vice President 2005/1/27-2/3 Mexico, Peru,

Vene-zuela, Trinidad& To-bago, Jamaica Jia Qinglin(賈慶林), Chairman of Chinese

People’s Political Consultative Conference

2005/5/7-22 Mexico, Cuba, Co-lumbia, Uruguay Hu Jintao(胡錦濤), President 2005/9/11-13 Mexico Luo Gan( 羅 幹 ), Member of Politburo

Standing Committee

2005/12/13-23 Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba

Wu Bangguo(吳邦國), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress

2006/9/9-10/28 Brazil, Uruguay, Chi-le Li

Changchun(李長春), Member of Politburo Standing Committee

2007/3/19-4/2 Mexico, Venezuela, Suriname, Peru Wu Guanzheng(吳官正), Member of

Po-litburo Standing Committee

2007/4/19-5/1 Cuba, Colombia, Chi-le

He Guoqiang (賀國強), Member of Polit-buro Standing Committee

2008/6/22-7/2 Cuba, Trinidad& To-bago, Brazil, Hu Jintao(胡錦濤), President 2008/11/16-23 Costa Rica, Cuba,

Peru

Xi Jinping(習近平), Vice President 2009/2/8-22 Mexico, Jamaica, Columbia, Ven-ezuela, and Brazil Wu Bangguo(吳邦國), Chairman of the

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress

2009/9/1-7 Cuba, the Bahamas

Hu Jintao(胡錦濤), President 2010/4/14-16 Brazil

Xi Jinping(習近平), Vice President 2011/6/4-13 Cuba, Uruguay, Chile Wen Jiabao(溫家寶), Premier 2012 /6/20-26 Brazil, Uruguay,

Ar-gentina, Chile Jia Qinglin(賈慶林), Chairman of Chinese

People’s Political Consultative Conference

2012/12/3-8 Costa Rica, Argen-tina

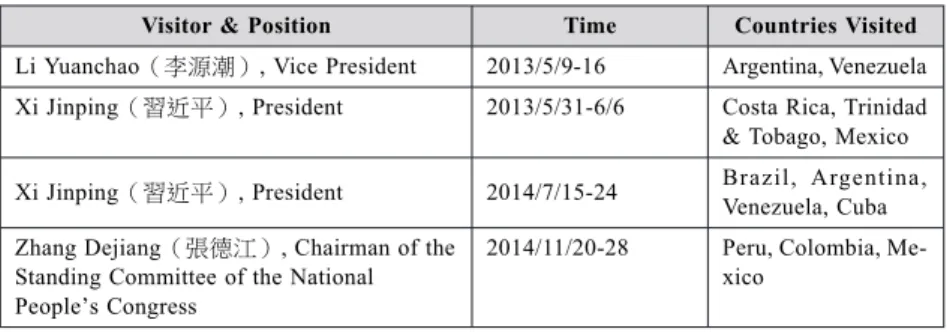

Table 2: Official Visits by PRC Leaders to Latin America: Xi Jinping Era

Visitor & Position Time Countries Visited

Li Yuanchao(李源潮), Vice President 2013/5/9-16 Argentina, Venezuela Xi Jinping(習近平), President 2013/5/31-6/6 Costa Rica, Trinidad & Tobago, Mexico Xi Jinping(習近平), President 2014/7/15-24 Brazil, Argentina,Venezuela, Cuba Zhang Dejiang(張德江), Chairman of the

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress

2014/11/20-28 Peru, Colombia, Me-xico

Source: The author compiled from news reports.

of the Xi Jinping era, there already have been four visits. The strong support from the state leaders have provided more momentum driving as well as deepening economic exchanges.

It is understandable that PRC leaders always have illustrated the win-win strategy toward China-Latin America relations and streng-thened the spirit of South-South cooperation on the basis of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (mutual respect for territorial in-tegrity and sovereignty, nonaggression, noninterference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence).2 In

Zheng Bingwen, Sun Hongbo, & Yue Yunxia, “The Present Situation and Prospects of China-Latin American Relations: A Review of the History since 1949,” in Wu Baiyi, Liu Weiguang, He Shuangrong, & Cai Tongchang, ed.,

China-Latin America Relations: Review and Analysis, Volume 1 (Beijing: Social

Sciences Academic Press, 2012), p. 3; mainland China’s late Premier and moderate leader Zhou Enlai announced “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” at the First National People’s Congress in 1954 and carried out a propaganda campaign on a large scale, which really signaled its shift of partial attention to the Third World in general and Afro-Asian nations in particular. See Steven I. Levine, “China in Asia: The PRC as a Regional Power,” in Harry

1990, Yang Shangkun, then PRC President, made state visits to five Latin American nations (i.e. Mexico, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile) and mentioned the foundation of Chinese foreign policy toward Latin America was based upon the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.3When mainland China published China’s Policy Paper

on Latin America and the Caribbean in 2008, it identified these Five

Principles again,4 which emphasized the necessity and preeminence

of the South-South relationship.

In a 2003 official statement, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC voiced its position on South-South cooperation by illustrating the necessity of a unified third world while confronting pressure from the North. For the causes of the South, it further stated that mainland China would like to offer assistance “sincerely and without any con-ditions attached.”5

Mainland China’s support for the South-South cooperation has drawn attention and elicited expectation among scholars and practi-tioners. Some Latin American scholars are discussing the emergence of new South-South relations and mainland China’s role in promotion

Harding ed., China’s Foreign Relations in the 1980s (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), p. 116.

Zouxian, “Yang Shangkun: Writes A New Chapter for Sino-Latin American Relations,” CNTV News Network, June 3, 2013, <http://news.cntv.cn/2013/06/03/ ARTI1370259614401819.shtml>.

Gastn Fornes & Alan B. Philip, The China-Latin America Axis: Emerging

Markets and the Future of Globalisation (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012),

p.138.

Jose Luis Leon-Manriquez & Adrian H. Hearn, “China, Latin America, and the Trajectory of Change,” in Adrian H. Hearn & Jose Luis Leon-Manriquez, eds., China Engages Latin America: Tracing the Trajectory (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2011), p. 283.

of a “pro-South agenda.”6Many even hold that the cooperation among

major emerging economies (e.g. mainland China, Brazil, India, and South Africa) staged a successful resistance against the West during the 2003 World Trade Organization ministerial meeting.

Addressing the National Congress of Brazil in November 2004, President Hu Jintao said the development objectives of mainland China and Latin America relations should focus on “supporting each other politically and complementing each other economically and building mutually beneficial and win-win partnership at new starting points.”7 On another occasion in Santiago, Mr. Hu Jintao identified

that “China, as a large developing country with a strong sense of re-sponsibility, is ready to contribute its share in advancing win-win cooperation for sustainable development.”8

Prior to his 2013 visit to Latin America, President Xi expressed that “In international affairs, the two sides have stepped up coordination and cooperation, effectively upholding their fundamental interests and the common interests of the developing countries.”9He implicitly

suggested the importance of South-South cooperation. In 2015, at

Alex E. F. Jilberto & Barbara Hogenboom, “Latin America – from Washington Consensus to Beijing Consensus?” in Alex E. F. Jilberto & Barbara Hogenboom, ed., Latin America Facing China: South-South Relations beyond the Washington

Consensus (New York: Berghahn Books, 2012), pp. 182-184.

Hu Jintao,“Hu Jintao Addresses the Brazilian Parliament (Full Text),” Ministry

of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, November 13, 2004, <http://

www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/huvisit_665888/t170363.shtml>. “China vows to promote win-win cooperation,” Xinhua, November 20, 2004, <http://china.org.cn/english/2004/Nov/112737.htm>.

Yang Yi, “President Xi Jinping Gives a Joint Written Interview to the Media of Trinidad and Tobago, Costa Rica and Mexico,” Xinhua, May 31, 2013, <http:// news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-05/31/c_132423049_2.htm>.

the first meeting of the China-CELAC Forum, Xi explicitly expressed that he hopes the forum will “have an important and far-reaching impact on promoting South-South cooperation and prosperity for the world.”10Part of the rationale behind this strategy is to avoid becoming

a neo-colonialist power. Furthermore, mainland China would like to create a favorable external environment for the purpose of maintaining the stability of its internal economy.

2. Resources Diplomacy and Others

With mainland China’s economic rise and the urgent need of raw materials, Latin America has occupied a critical position in ma-inland China’s national strategy and diplomacy.11From the viewpoint

of geography, the distance between mainland China and Latin America has prevented them from establishing closer economic exchanges. Prior to the mid-1990s, two-way trade between mainland China and Latin America was relatively small.12 For example, in 1979,

two-way merchandise trade between China and Latin America was only 1 billion US dollars and reached 2.3 billion in 1990.13 This trade

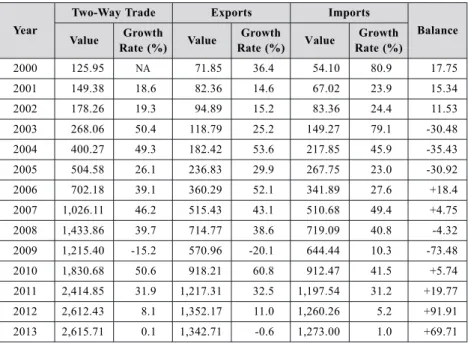

figure, however, jumped to 14.9 billion in 2001 (see Table 3). Mainland China’s trade exchanges with Latin America have been faster than with the world as a whole. Between 2001 and 2013 Shannon Tiezzi, “Despite US-Cuba Detente, China Forges Ahead in Latin America,” The Diplomat, January 9, 2015, <http://thediplomat.com/2015/01/ despite-us-cuba-detente-china-forges-ahead-in-latin-america/>.

Zhiqun Zhu, China’s New Diplomacy: Rationale, Strategies and Significance, 2ndEdition (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), p.83.

Gastn Fornes & Alan B. Philip, The China-Latin America Axis: Emerging

Markets and the Future of Globalisation, p. 26.

Zhang Quingmin, “The Relationship between China and Latin America,” China.

org.cn., July 28, 2009, <http://www.china.com.cn/international/txt/2009-07/28/

(see Table 3), mainland China’s exports to Latin America grew from $8.23 billion to $134.27 billion with average annual growth rate 27.4%; its imports from $6.7 billion to $127.3 billion with average annual growth rate 31%; its two-way trade from $14.93 billion to $261.57 billion with average annual growth rate 28%.

Table 3: Mainland China’s Merchandise Trade with Latin America, 2001-2013

Unit: 100 Million US Dollars

Year

Two-Way Trade Exports Imports

Balance Value Growth Rate (%) Value Growth Rate (%) Value Growth Rate (%) 2000 125.95 NA 71.85 36.4 54.10 80.9 17.75 2001 149.38 18.6 82.36 14.6 67.02 23.9 15.34 2002 178.26 19.3 94.89 15.2 83.36 24.4 11.53 2003 268.06 50.4 118.79 25.2 149.27 79.1 -30.48 2004 400.27 49.3 182.42 53.6 217.85 45.9 -35.43 2005 504.58 26.1 236.83 29.9 267.75 23.0 -30.92 2006 702.18 39.1 360.29 52.1 341.89 27.6 +18.4 2007 1,026.11 46.2 515.43 43.1 510.68 49.4 +4.75 2008 1,433.86 39.7 714.77 38.6 719.09 40.8 -4.32 2009 1,215.40 -15.2 570.96 -20.1 644.44 10.3 -73.48 2010 1,830.68 50.6 918.21 60.8 912.47 41.5 +5.74 2011 2,414.85 31.9 1,217.31 32.5 1,197.54 31.2 +19.77 2012 2,612.43 8.1 1,352.17 11.0 1,260.26 5.2 +91.91 2013 2,615.71 0.1 1,342.71 -0.6 1,273.00 1.0 +69.71 Sources: Ministry of Commerce of People’s Republic of China, China’s Foreign Trade Situation

Report.

As the Chinese economy grows spirally, Chinese industries have come to rely more on imported supplies of vital resources. Entering the 21st Century, mainland China has become the biggest consumer

of copper, tin, zinc, platinum, steel, and iron ore; the second biggest consumer of aluminum and lead; and the third biggest consumer of

nickel.14 On top of these materials, the most urgent need is energy

supply. According to estimates, mainland China’s oil use rose from 4.95 million barrels a day in 2002 to 5.39 million barrels in 2003 and to 5.70 million barrels in 2004.15In sum, the increasing Chinese

demand for petroleum accounted for 35% of the rise in total world demand in 2003 and 30% in 2004.16With regard to food supply, there

has been a dramatic increase of Brazilian and Argentine soybean exports to mainland China because of mainland China’s ongoing grain shortage and struggle to feed its 1.3 billion people.17

The importance of natural resources and foodstuffs in trade be-tween mainland China and Latin America can be reflected by the composites of their economic exchanges. Let us examine five major Latin American powerhouses’ product exports to mainland China (see Table 4). Except for Mexico, almost 90% or more of the products exported to mainland China are mineral products, primary industrial goods, and foodstuffs. For Argentina, the top five products exported to mainland China are oil seeds and oleaginous fruit, fixed vegetable oils, crude oil, leather, and unprocessed tobacco; for Brazil, they are iron ore, oil seeds and oleaginous fruit, crude oil, paper pulp and waste, sugars, molasses, and honey; for Chile, they are copper, copper ore, iron ore, paper pulp and waste, fruits, and nuts; for Mexico, they are copper ore, crude oil, electronic microassemblies, and iron ore; for Venezuela, they are crude oil, petroleum derivatives, iron ore,

Robert J. Samuelson, “Great Wall of Unknowns,” The Washington Post, May 26, 2004, p. A27.

Bhushan Bahree, “China Now Leads in New Demand for Oil, IEA Says,” The

Wall Street Journal, November 14, 2003, p. A10.

Bhushan Bahree, “China Now Leads in New Demand for Oil, IEA Says.” Chung-chian Teng, “The Policy and Behavior of the Rising China in Latin America,” The Journal of International Relations, January 2007, pp. 30-31.

ferrous alloys, and base metal scrap. In some countries, more than 60% of their exports are accounted for by one single commodity.

Table 4: Latin America and the Caribbean: top five product exports to mainland China, 2011

Country

Sum of top five pro-ducts(%)

First Second Third Fourth Fifth

Argentina 87.8 Oil seeds and oleagi-nous fruit (69.3) Fixed veg-etable oils (8.3) Crude oil (2.1) Leather (3.2) Unprocess-ed tobacco (1.9)

Brazil 86.9 Iron ore (49.1) Oil seeds and oleagi-nous fruit (22.5) Crude oil (-) Paper pulp and waste (3.5) Sugars, mo-lasses, and honey (2.4) Chile 94.0 Copper (60.7) Copper ore (18.3) Iron ore (7.8) Paper pulp and waste (4.9) Fruits and nuts(2.1)

Mexico 54.5 Copper ore(14.0) Crude oil(12.5)

Electronic microas-semblies (11.7) Passenger vehicles (10.0) Iron ore (6.3)

Venezuela 99.8 Crude oil (62.2) Petroleum derivatives (27.5) Iron ore (8.1) Ferro alloys (1.6) Base metal scrap (0.4) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, The People’s Republic of

China and Latin America and the Caribbean: Dialogue and Cooperation for the new challenges of the global economy (Santiago, Chile: United Nations, 2012), p.35.

In addition to trade, mainland China’s loans and aid toward Latin America play a critical role in their economic relations. The terms loan-for-natural resources or loan-for-food best describe their relationship. While observing the loans made by Chinese banks toward Latin America from 2005 to 2011, some experts argue that two thirds of the loans were earmarked to acquire oil resources and related ac-tivities.18In a word, mainland China is performing the neo-colonialist

policy and behavior by this kind of resources diplomacy. Nevertheless, the anatomy of these loans might reveal more interesting details and realize their real contributions to local development. In the first place, loans given to the Latin American governments were for infrastructure construction, such as transportation systems, communication systems, irrigation systems, and road building. Second, loans for national oil companies there were for renovation and reinvestment. This applies to Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) in particular. Owing to funding various kinds of social programs in Venezuela, PDVSA must obtain loans from outside to maintain its operations, as well to boost its production.19 Therefore, loans were utilized to help needed people.

From the aforementioned analysis, a tentative conclusion can be drawn that trade and investment between mainland China and Latin America goes beyond natural resources and foodstuffs. In other words, infrastructure construction is one of the major foci in the bilateral relationship.

Central America seems to be an exception for current mainland China’s resources diplomacy, because nations in that region lack vital mineral products and their major exports consist of coffee, fruits (especially bananas), and other minor agricultural and mineral products.20Costa Rica so far is the only country in Central America

to break ties with Taiwan and forge diplomatic relations with Beijing. Before the diplomatic truce proposed by President Ma Ying-jeou,

Town: Chinese Finance in Latin America,” Working Paper, March 2012, p.5,

Inter-American Dialogue, <http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/TheNew

BanksinTown-FullTextnewversion.pdf>.

Henry Sanderson & Michael Forsythe, China’s Superbank: Debt, Oil and

Influence (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley, 2013), pp. 132-138.

Thomas E. Skidmore, Peter H. Smith, & James N. Green, Modern Latin America, 7thEdition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 91-97.

mainland China’s only interest in this region was its diplomatic struggle with Taiwan.21Nevertheless, the geographic location

con-necting the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean (via the Caribbean Sea) is the most important asset Central America has. In the 19th

century, the European powers and the United States assessed the value and necessity of building a canal there.22 In view of its

economic rise, mainland China has become one of the most important and frequent users of the Panama Canal.

3. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

Having discussed the increasingly close economic contacts be-tween mainland China and Latin America, it is necessary to assess Latin America’s weight in mainland China’s grand strategy, especially in comparison with Europe, Asia, and Africa. The “One Belt, One Road” initiative would be the grand strategy, at least over the next ten years, and it is the starting point to assess the role and function of Latin America.

To advance this strategy, mainland China is making critical moves on political and economic fronts. It is perceived widely that fostering good relations with neighboring countries or a peaceful en-vironment is a precondition for successful implementation of the “One Belt, One Road” strategy. At least, in the last year, mainland China has made substantial diplomatic movement to reduce tension with Japan in the East China Sea and Vietnam in the South China

Francisco Haro Navejas, “China’s Relations with Central America and the Cari-bbean States,” in Adrian H. Hearn & Jose Luis Leon-Manriquez, eds., China

Engages Latin America: Tracing the Trajectory (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner,

2011), pp. 204-211.

Gregory B. Weeks, U.S. and Latin American Relation (New York: Pearson Long-man, 2008), pp. 45-50.

Sea. The most recent event was the foreign ministers of South Korea, Japan, and mainland China holding their first meeting in three years and agreeing “to continue their efforts to hold the trilateral summit at the earliest convenient time for the three countries.”23

Economically speaking, three financial mechanisms are in good positions for the promotion of “One Belt, One Road.” The first is BRICS’ New Development Bank (NDB), which was formally formed with the Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA) at the 2014 annual summit of BRICS in Fortaleza, Brazil. The major objective of NDB is the provision of a capital base to finance infrastructure and sustainable development, while the CRA will serve to rescue the economies of participating countries during economic downturns and international balance of payments crises.24 NDB with $100 billion

initial capital plans to start lending two years after the legislative ap-proval in each of the participating countries, which is the same time frame as CRA. It is believed widely that both NDB and CRA are in-ternational financial institutions to counterbalance both the Inin-ternational Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.25

During the 2014 APEC summit, President Xi announced estab-lishment of a $40 billion “Silk Road Fund,” which will invest mainly in infrastructure and resources, as well as industrial and financial co-Ju-min Park, “Top South Korea, Japan, China envoys agree to work for a summit soon,” Reuters, March 21, 2015, <http://www.reuters.com/ar-ticle/2015/03/21/us-southkorea-china-japan-idUSKBN0MH02Q20150321>.

Ryan Eustace & Ronn Pineo, “The BRICS’ New Financial Initiatives: Good For Whom?” COHA Research, July 28, 2014, <http://www.coha.org/the-brics-new-financial-initiatives-good-for-whom/>.

“BRICS voices disappointment with non-implementation of IMF reforms,”

China Daily, July 16, 2014, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2014-07/16/

operation, among other projects related with the “One Belt, One Road” strategy.26The Silk Road Fund Co. Ltd. has officially registered,

and it began operation in December 2014. Currently, $10 billion U.S. dollars is ready for investment.27Another key financial institution

is the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was proposed by Xi Jinping in his speech at Indonesian Parliament on October 3, 2013.28Although it has been widely speculated that this

bank rivals the World Bank, Xi reiterated that “under current operation of international economic and financial order, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Silk Road Fund are going to be complementary with global and regional multilateral development banks, instead of replacing them.”29

Despite strong U.S. opposition and vehement campaigning against the AIIB,30the process of preparation has continued, with thirty-three

Yang Yi, “China pledges 40 bln USD for Silk Road Fund,” Xinhua, November 8, 2014, <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-11/08/c_133774993. htm>.

Wei Xi, “$10 Billion of Silk Road Fund Is Ready and 65% from China’s Foreign Exchange Reserves,” Xinhua, February 16, 2015, <http://news.xinhuanet.com/ fortune/2015-02/16/c_127503252.htm>.

Banyan, “An Asian infrastructure bank: Only connect,” The Economist, October 4, 2013, <http://www.economist.com/blogs/analects/2013/10/asian-infrastructure-bank-1>.

Dhara Ranasinghe, “Why Europe is breaking ranks with US on China bank,”

CNBC, March 19, 2015, <http://www.cnbc.com/id/102518551>; “Xi Jinping:

To accelerate the promotion of the construction of Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” Xinhua, November 6, 2014, <http:// news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2014-11/06/c_1113146840.htm>.

Kishore Mahbubani, “Why Britain Joining China-Led Bank Is a Sign of American Decline,” The Huffington Post, March 16, 2015, <http://www.huffingtonpost. com/kishore-mahbubani/britain-china-bank-america-decline_b_6877942.html>; Jane Perlez, “U.S. Opposing China’s Answer to World Bank,” The New York

nations as founding members, including major American allies in Europe, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Luxemburg.31The Economist magazine stated that, in the process

of building AIIB and the rivalry between mainland China and America, mainland China is “a clear winner.”32The AIIB will become operational

at the end of 2015. Then, we will have more insight into how mainland China will lead and cooperate with others in the international financial circle.

One Belt means the ‘New Silk Road Economic Belt,’ which connects western parts of China and Europe via Central Asia, West Asia, and the Middle East; One Road indicates the ‘21st Century

Maritime Silk Road,’ which connects the southern part of China and Europe via Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.33 Following this delineation of ‘One Belt, One Road,’ Latin

America is not part of it. Moreover, PRC leaders failed to make linkage between the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative and Latin America on two important occasions. During his visit in that region in 2014, President Xi did not mention the New Silk Road publicly.34

Times, October 10, 2014, p. A1.

“Switzerland, Luxembourg apply for China-led infrastructure bank,” RT, March 21, 2015, <http://rt.com/business/242897-switzerland-luxembourg-aiib-china/>; Jin Kai, “The AIIB: China’s Just Getting Started,” The Diplomat, March 20, 2015, <http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/the-aiib-chinas-just-getting-started/>. “The infrastructure gap: Development finance helps China win friends and in-fluence American allies,” The Economist, March 21, 2015, <http://www.economist. com/news/asia/21646740-development-finance-helps-china-win-friends-and-in-fluence-american-allies-infrastructure-gap?fsrc=nlw|hig|19-03-2015|>.

Flynt Leverett, Hillary Mann Leverett, & Wu Bingbing, “China Looks West: What Is at Stake in Beijing’s “New Silk Road” Project,” The World financial

Review, January/February 2015, pp. 6-7; “Xi Jinping: To accelerate the promotion

of the construction of Silk Road Economic Belt and 21stCentury Maritime Silk Road.”

In a similar vein, Chinese authority mentioned nothing about ‘One Belt, One Road’ during the 2015 ministerial meeting of the China-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) Forum.35

Xue Li, a Division Director in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, raised the question about the relative importance of Latin American in China’s grand strategy. Xue argues that the New Silk Road’s “main objective is to establish cooperative networks in Europe and Asia,” so “Latin America and Africa are not as important for China’s ‘one belt, one road’ strategy as Eurasia.”36He further expressed

that Latin America is “far away, with lots of U.S. influence, weak economic connections, obvious cultural differences and no way to connect it [to China] via roads, making China-Latin America relations overall a weaker grade than China-Africa relations.”37

Nevertheless, Lu Guozheng, who is a board member of the Chinese Association of Latin American Studies and Chinese Asso-ciation of International Trade, presented the importance of Latin America in the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative from a historical pers-pective. His argument is based upon the Pacific Silk Road from 1565 to 1865, which constituted a vase trade network connecting two oceans (i.e., Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean) as well as three con-tinents (i.e. Asia, America, and Europe). The Pacific Silk Road linked Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, “The New Silk Road and Latin America: Will They Ever Meet?” China Brief, Vol. 15, Issue 5, March 6, 2015, p.1.

Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, “The New Silk Road and Latin America: Will They Ever Meet?” p. 2.

Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, “The New Silk Road and Latin America: Will They Ever Meet?” p. 2.

Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, “The New Silk Road and Latin America: Will They Ever Meet?” p. 2.

mainland China and Mexico, was the main sea route for trans-Pacific trade, represented the last glory of the maritime Silk Road, and, fur-thermore, extended to Europe through the Atlantic Ocean, transporting goods from mainland China, Japan, India, and Southeast Asia.38 Lu

Guozheng, in the end, believes that the construction of the ‘21st

Century Maritime Silk Road’ and the connectivity between mainland China and Latin America must be beneficial for countries and peoples in the Pacific Basin area.39

III. The Nicaragua Grand Canal and Mainland China

in Central America

“The Panama Canal was the U.S. canal in the XX Century, a Nicaragua Canal would eventually be the Chinese Canal in the XXI Century,” Juan Gabriel Tokatlian said.40This is a proper description

of the strategic meaning of the canal and pinpoints the reason President Ortega has named it as “Phase Two” of the Nicaraguan revolution and has made every effort to make the dream come true, which would leave his family legacy in history.

1. President Daniel Ortega’s Dream: A Legacy

With the grand strategy on mind, President Ortega has bet his Lu Guozheng, “Maritime Silk Road: Assists to Promote Sino-Latin American Economics and Trade, Cultural Cooperation and Development,” Chinanet, January 8, 2015, <http://big5.china.com.cn/news/txt/2015-01/08/con-tent_34508733.htm>.

Lu Guozheng, “Maritime Silk Road: Assists to Promote Sino-Latin American Economics and Trade, Cultural Cooperation and Development.”

Guillermo Háskel, “Nicaragua Canal Project Seen Having Geopolitical, Not Just Trade Implications,” Buenos Aires Herald, July 21, 2014, <http://bueno- sairesherald.com/article/165077/nicaragua-canal-project-seen-having-geopolitical-not-just-trade-implications>.

political life by wielding his power to make swift actions facilitating the realization of the Grand Nicaragua Canal. The most important move was to obtain authorization from the legislative branch. The last mile of this plan started with the debate and approval of National Assembly of Nicaragua in June 2014 about constructing and operating a canal linking Nicaragua’s Caribbean and Pacific coasts by HK Nica-ragua Canal Development Investment Company. One day later, Presi-dent Daniel Ortega and Chinese businessman Wang Jing officially signed the agreement.41With a 450-year dream and 72 proposals,42

the construction plan of the Grand Nicaragua Canal has been finalized and the canal is set to be finished in 2019.

The agreement, which was passed by the Ortega-controlled Nica-raguan congress after less than 48 hours of public debate, gives Wang’s HKND a 50-year concession to build the canal, with an option to run it for an additional 50 years. The canal project consists of six sub-projects, including the canal itself, construction of two deep-water ports, a free-trade area, tourism projects in San Lorenzo, a ‘dry canal’ freight railway, and an airport in the city of Rivas.43

Another critical part of the legislative authorization is the power of land expropriation for the canal project. The Canal Law establishes the Nicaragua Canal and Development Project Commission and gives “Nicaragua’s Ortega, Wang Jing Sign Canal Agreement,” San Jose Mercury

News, June 14, 2014,

<http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_23465932/nicaraguas-ortega-wang-jing-sign-canal-agreemen>.

Nina Lakhani, “Giant Canal Threatens Way of Life on The Banks of Lake Nic-aragua,” The Telegraph, October 26 2014, <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/ worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/nicaragua/11167697/Giant-canal-threatens-way-of-life-on-the-banks-of-Lake-Nicaragua.html>.

“Nicaragua’s Ortega, Wang Jing Sign Canal Agreement”; Jonathan Watts, “Nica-ragua Waterway to Dwarf Panama Canal.”

it all power to determine which land needs to be expropriated, and how much they will pay for the land.44Legal property owners whose

lands are expropriated by the government are not allowed to appeal the decision or negotiate market-value compensation with the Grand Canal Commission.45

The Nicaragua Grand Canal project has a close relationship with Ortega’s family. The beginning of this grand project can be traced back three years to when Nicaraguan officials, including Ortega’s favorite son Laureano, visited China and the first meeting between Ortega and Wang Jing was held. On that occasion, Wang Jing, spoke with Laureano privately about the canal.46 In late October of 2013,

Laureano went to China again with a group of 21 Nicaraguan poli-ticians, academics, and businesspeople to talk about the $40 billion canal project.47

On top of his popularity, there are several factors have strengthened the resolution of President Daniel Ortega to speed up the construction of the Grand Nicaragua Canal. In the first place, it is a contribution to Nicaragua’s economic development and more benefits are expected from the enlarged economy. Paul Oquist, who is secretary of public policies of the presidency, said the Canal will double Nicaragua’s Tim Rogers, “HKND: ‘Nicaragua Is Not A Very Tranquil Country’,” The

Nica-ragua Dispatch, September 7, 2014, <http://nicaNica-raguadispatch.com/2014/09/

hknd-nicaragua-is-not-a-very-tranquil-country/>.

Tim Rogers, “HKND: ‘Nicaragua Is Not A Very Tranquil Country’.” Nina Lakhani, “Giant Canal Threatens Way of Life on The Banks of Lake Nica-ragua.”

Russell Flannery, “Nicaraguan President’s Son Laureano Ortega Discusses $40 Bln Canal During China Visit,” Forbes, October 31, 2013, <http://www.forbes. com/sites/russellflannery/2013/10/31/nicaraguan-presidents-son-laureano-ortega-discusses-40-bln-canal-during-china-visit/>.

GDP and triple employment by 2018.48Second, HKND officials

es-timated that the project would “employ about 50,000 people directly, and indirectly benefit another 200,000.”49Moreover, an opinion poll

in Nicaragua shows that around half the population supports the canal project.50Fourth, the Nicaragua Canal will be more competitive than

the Panama Canal because the former can “handle ships much larger than those that can pass through the Panama Canal.”51The Nicaraguan

canal would support supertankers capable of carrying 2.3 million barrels of oil, which are too big for Panama.52

2. The Construction of Canal: Capital and Capabilities

As the original plan was for an entirely privately funded project, the operators have to access international financial markets in New York, London, and Tokyo for investment in the project. An HKND spokesman said they were negotiating with investors from China, Europe, Asia, and the Americas, but declined to give any names.53

Attracting international investment, the operator needs to provide credible and reliable information and, as a result, has hired the world's leading consulting company, Environmental Resources Management, to conduct impact assessments.54

Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama canal.” “Nicaragua’s Ortega, Wang Jing Sign Canal Agreement.”

Nina Lakhani, “Giant Canal Threatens Way of Life on The Banks of Lake Nica-ragua.”

“Nicaragua’s Ortega, Wang Jing Sign Canal Agreement.”

Nina Lakhani, “Giant Canal Threatens Way of Life on The Banks of Lake Nica-ragua.”

Nina Lakhani,“China’s Nicaragua Canal Could Spark A New Central America Revolution,” The Daily Beast, November 31, 2014, <http://www.thedailybeast. com/articles/2014/11/30/china-s-nicaragua-canal-could-spark-a-new-central-america-revolution.html#>.

In addition, President Daniel Ortega assisted the promotion cam-paign and met with ambassadors from Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and Canada to solicit financial support.55

Although Ms. Hua Chunying, the spokeswoman of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, has reiterated that there is no role and involvement of Beijing in this canal project,56many foreign and

do-mestic observers have indicated Beijing is behind the scenes in the project and the funds for the Nicaragua Canal project may come from mainland China.57Nevertheless, funds from Chinese enterprises will

be inevitable. In an interview with Nicaragua Dispatch, MacLean-Abaroa, current advisor to HKND, admitted that “Mr. Wang is working with Chinese state businesses that will have a small amount of parti-cipation in this project and will finance a great part of this project.”58

In fact, with abundant capital, it is almost inconceivable that any big construction project in the world will neglect the importance of ma-inland China for seeking the necessary capital. It is noteworthy that many important Chinese state companies are involved in this project. The major contractor and subcontractor of road constructio n is China Railway Siyuan Survey and Design Group Company; Changjiang In-stitute of Survey, Planning, Design and Research is a subcontractor of canal engineering design; CCCC Second Harbor Engineering Com-pany Ltd.59and Investigation and Design Institute Limited Company

Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama canal.” Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama canal.”

“Chinese-Invested Nicaragua Canal Has Nothing to Do with Chinese Govern-ment,” Chinese Daily, December 24, 2014, <http://www.chinesedaily.com/focus_ list.asp?no=c1337043.txt&catid=4&lanmu=Z09&readdate=12-24-2014>.

Guillermo Háskel, “Nicaragua Canal Project Seen Having Geopolitical, Not Just Trade Implications.”

Tim Rogers, “HKND: ‘Nicaragua Is Not A Very Tranquil Country’.” ‘CCCC’ is the abbreviation of China Communications Construction Company

are subcontractors of harbor construction; Civil Aviation Engineering Consulting Company of China is a subcontractor of airport construction; and Shenzhen Layout Urban Design Consulting Company, Ltd. is subcontractor of the free trade zone and resorts.60All these are

well-known state and semi-state enterprises, and they could conduct and solicit financial investment and even guarantee the success of this project.

3. Foreseeable Challenges for the Canal Project

The most serious challenge is the negative environmental impact, especially on Lake Nicaragua. Centro Humboldt, an internationally known environmental group, publicized its two-year investigation with a conclusion that “the canal was unviable and posed extraordinary environmental risks, especially to the lake and there will be insufficient water to maintain the canal by 2039.”61Jaime Incer, an environmentalist

and presidential adviser, reminded to be cautious and claimed that “there are no alternatives for cleaning a lake after a disaster has hap-pened. We [do not] have another Lake Nicaragua.”62

A second one is the failure of the Nicaraguan government to win a national consensus by holding a thorough consultation with the civil society in general, including opposition parties, non-go-vernmental organizations, and indigenous groups. Opposition

law-Ltd., a state-owned construction group and world top 500 enterprise, and Second Harbor Engineering Company Ltd. belongs to its infrastructure construction group. Antonio Hsiang, “HK Enterprise-Invested Nicaragua Canal Open Ceremony,”

Yazhou Zhoukan, Vol. 28, No. 48, December 7, 2014, <http://www.yzzk.com/

cfm/content_archive.cfm?id=1417061011746&docissue=2014-48>.

Nina Lakhani,“China’s Nicaragua Canal Could Spark A New Central America Revolution.”

makers accused the government of violation of the constitution and sovereignty by awarding immunity, tax breaks, and other preferential treatment for foreign investors in such a project.63 The Sandinista

Renovation Movement expressed its opposition to the bill and “any document that gifts a concession, privileges, exonerations and tax exemptions to an unknown company, for an unknown route, for a period of 100 years.”64 Indigenous groups also say they have not

been adequately consulted.

Some have challenged the viability of this canal project and if it can be finished in the end. One argument reveals that the world economic slowdown in recent years “means large numbers of ships are unused, perhaps 5 percent of the global fleet. Many vessels are scheduled to be completed in coming years, meaning the percentage of idled ships could grow to more than 20 percent.”65 Additionally,

the melting of icebergs in the Arctic may present a viable alternative sea lane, which will leave the canal idle.66

Finally, there is the compensation to the property owners. Some people are afraid that they will not get enough money to buy replace-ment properties because compensation is to be based on declared tax value, or market value, whichever is lower. Normally, tax values are set far below the market value.67

Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama Canal.” Jonathan Watts, “Nicaragua waterway to dwarf Panama Canal.”

Luis M. Galeano & Michael Weissenstein, “Nicaragua Approves Massive Canal Project,” Yahoo News, June 13, 2013, <http://news.yahoo.com/nicaragua-approves-massive-canal-project-195037555.html>.

Luis M. Galeano & Michael Weissenstein, “Nicaragua Approves Massive Canal Project,”

“Nicaragua’s Trans-Oceanic Canal Survey Leaves Residents Fearful of Losing Homes,” The Guardian, August 27, 2014, <http://www.theguardian.com/world

4. The Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Implication

Geopolitically, the canal would further strengthen mainland China’s foothold in Latin America. Mainland China is already a major buyer of Venezuelan oil and gas, and its trade with the continent increased from $12 billion (£7.5 billion) in 2000 to $250 billion (£ 157 billion) in 2012.68

Telemaco Talavera, spokesman for the government’s Canal Com-mission, told The Telegraph: “The cold war is over. In today’s world, geoeconomics are much more important than geopolitics and the U.S. and mainland China are practically interdependent in financial and business terms. The canal will benefit the world, and transform Nicaragua. Some people have doubts, but once they understand how every Nicaraguan will benefit, they will get behind it.”69

If the Nicaragua Grand Canal is built, the landscape of Central America will be changed dramatically. Not only will the wet canal itself have an impact on the region, but also the dry canals in other parts of Central America will have even greater impact. In the first place, Honduras already has signed an agreement with the China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) for a $20 billion railway project, connecting the sea port of Puerto Castilla on the Caribbean Sea with Amapala, located on El Tigre Island in the Gulf of Fonseca – a part of the Pacific Ocean bordering Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador.70This railway system was designed to assist in the

ship- /2014/aug/27/residents-fearful-nicaragua-trans-oceanic-canal-surveys-hknd-gro-up>.

Nina Lakhani, “China’s Nicaragua Canal Could Spark A New Central America Revolution.”

Nina Lakhani, “China’s Nicaragua Canal Could Spark A New Central America Revolution.”

loading of vessels up to 300,000 tonnes, a kind of dry canal comple-mentary to the wet canal.71Another dry canal project in the planning

stage is Guatemala’s $10 billion plan, consisting of new ports on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and a 244-mile dry canal.72It goes without

saying that Chinese financial support will be inevitable and critical. Under these circumstances, mainland China will hold the key position in Central America and severely undermine U.S. supreme status there.

IV. U.S. and Central America: A Challenge to Mainland

China?

Strategically speaking, Central America, including major nations in the Caribbean (namely, Cuba, Haiti, and Dominican Republic) is the real backyard of the United States. With rapid economic growth and expansion after the end of the Civil War, U.S. policy toward Central America has been based upon “a combination of economic opportunism and national security.”73One important indicator to

de-monstrate this is U.S. military interventions in this region in the 19th

and 20thcenturies. The strategic importance of this region includes

a canal to communicate both oceans and, as a result, the United States finished the construction of the Panama Canal and solely controlled it almost a hundred years.74

“Honduras and China Sign MOU for Interoceanic Railway,” Resistencia Honduras, October 9, 2013, <http://www.resistenciahonduras.net/index.php?option=com_ content&view=article&id=5882:honduras-and-china-sign-mou-for-interoceanic-railway&catid=101:news&Itemid=349>.

“Honduras and China Sign MOU for Interoceanic Railway.”

Rob Holmes, “China Digs Deep in Central American Canal Race,” World, March 8, 2014, <http://www.worldmag.com/2014/03/china_digs_deep_in_ central_american_canal_race>.

Gregory B. Weeks, U.S. and Latin American Relations, pp. 45-47.

Take Cuba as an example. The serious intention of the U.S. to take control of Cuba from Spain can be reflected by the 1854 Ostend Manifesto, which “spelled out why the United States should purchase Cuba and, if Spain were not willing to sell, stated that troops should take it by force to maintain order.”75 In the end, the United States

forced Spain to allow the independence of Cuba after the Spanish-American War in 1898. With the approval of the Platt Amendment by U.S. Congress, Cuba became an American protectorate.76 In the

meantime, the U.S. built up firm control over the Cuban economy, especially the sugar production.77Ever since then, the United States,

most of the time, has taken a supreme and dominant position in its relationship with Cuba. This is a microscopic picture of American imperialism in Latin America. It is easy to locate similar foreign policy behavior toward other Central American states, such as Nica-ragua.

As its power has been declining, it is difficult for the U.S. to maintain its leadership in this region and establish new institutions. Furthermore, quarrels or disputes have emerged with major Latin American powers, including Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela. As a result, President Obama has been blamed for “spying” in Brazil, ma-liciously described as “a warmonger” by Bolivia, and dismissed as a “lost opportunity” by Argentina.78

Turn,” in Albert Fishlow & James Jones, eds., The United States and theAmericas (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999), pp. 111-113.

Gregory B. Weeks, U.S. and Latin American Relations, p. 20.

Thomas E. Skidmore, Peter H. Smith, & James N. Green, Modern Latin America, 7thEdition, pp. 123-124.

Thomas E. Skidmore, Peter H. Smith, & James N. Green, Modern Latin America, 7thEdition, pp. 124-128.

Simon Romero & William Neuman, “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington,” The New York Times, December 19, 2014, p. A1.

The impatience of Latin American nations toward U.S. policy is quite obvious and, consequently, they have taken an independent position with regard to regional affairs. One of their recent efforts has been the treatment and status of Cuba in the Western Hemisphere. In the 2009 annual meeting of the Organization of American States (OAS) in Honduras, Latin American nations revoked the 1962 decision to suspend Cuba’s membership in this international regional organi-zation.79This collective action not only challenged but also rebuked

outdated U.S. policy toward Cuba. Furthermore, Latin American na-tions have determined to set up their own organization of economic integration as an alternative to OAS. Subsequently, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) was officially created in December 2011, including all states in the Western Hemis-phere except the United States and Canada.

Moreover, previous Cuba policy of the United States has had negative impact upon its policy in the region. In the 2012 Summit of the Americas in Colombia, leaders spent a lot of time talking about U.S.-Cuba policy, instead of talking what the United States wanted to focus on, such as exports, counternarcotics, and other issues.80

The 2015 Summit will be held in Panama, and Cuba has already ac-cepted the invitation from the Panamanian government and confirmed its participation for the first time.81The thaw of U.S.-Cuba relations

will let the U.S. avoid a potentially awkward meeting for American

Arthur Brice, “OAS Lifts 47-year-old Suspension of Cuba,” CNN, June 3, 2009, <http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/americas/06/03/cuba.oas/index.html?_s= PM:WORLD>.

Simon Romero &William Neuman, “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington.”

Simon Romero & William Neuman, “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington.”

officials. On the global level, the United Nations General Assembly has passed a resolution annually, requesting the U.S. to lift its economic, commercial, and financial embargo on Cuba of the last twenty-three years. In the final vote, only the United States and an ally, Israel, voted against the declaration and three Pacific island nations, Palau, Marshall Islands, and Micronesia, abstained.82All of

thes e highlight the embarrassment of the United States and the ab-surdity of this U.S. policy.

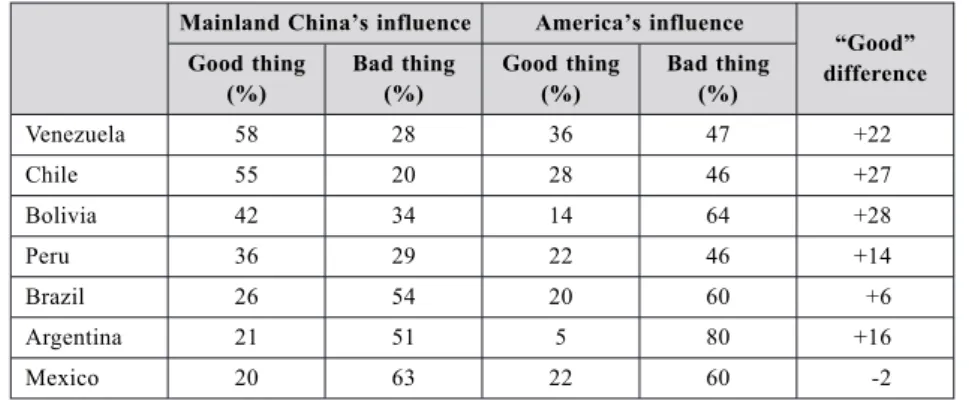

Meanwhile, mainland China’s rise has encroached on American influence and has gained support politically and economically in Latin America. When asking about mainland China’s influence in an international opinion poll by the Pew Research Center, more people hold that mainland China’s influence is good thing and is higher than America’s influence (see Table 5). Except for Mexico, people in other nations (i.e. Venezuela, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil, and Ar-gentina) expressed that mainland China’s influence is more positive than America’s.

Mirjam Donath & Louis Charbonneau, “For 23rdTime, U.N. Nations Urge End to U.S. Embargo on Cuba,” Reuters, October 28, 2014, <http://www.reuters. com/article/2014/10/28/us-cuba-un-idUSKBN0IH1RN20141028>.

Table 5: Mainland China’s Influence More Positive than America’s

Mainland China’s influence America’s influence

“Good” difference Good thing (%) Bad thing (%) Good thing (%) Bad thing (%) Venezuela 58 28 36 47 +22 Chile 55 20 28 46 +27 Bolivia 42 34 14 64 +28 Peru 36 29 22 46 +14 Brazil 26 54 20 60 +6 Argentina 21 51 5 80 +16 Mexico 20 63 22 60 -2 Source: Pew Research Center, Global Unease with Major World Power (2007).

Facing all these, Obama would like to turn the table on mainland China, win back American support, and return to the dominant position in Latin America. In 2013, Obama made state visits to Mexico and Costa Rica, where he convened all U.S. ambassadors in the region; Vice President Joe Biden later toured Brazil, Colombia, and Trinidad and Tobago. Their unusual and unprecedented diplomatic travel sweeping the Western Hemisphere revealed the changing policy and behavior but without knowing the direction and scope.

The next surprising maneuver in foreign policy toward Latin America was Obama’s announcement of normalization with Cuba in December 2014. Having sealed an agreement with Cuban President Raul Castro, President Obama personally ordered the restoration of full diplomatic relations with Cuba and the opening of an embassy in Havana for the first time in more than a half-century. What was on his mind was to “cut loose the shackles of the past,” and close the final chapter of the Cold War.83The secret negotiations with Cuba

began in June 2013, with eight rounds of talks in Canada and Vatican City.

Obama’s new Latin American policy won praise from leaders in this region.Now, however, Latin American leaders have a new kind of vocabulary to describe him: They are calling him “brave,” “extraordinary,” and “intelligent.”84Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff,

called Obama’s agreement with Cuba “a moment which marks a change in civilization”; President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela de-scribed it as “a brave gesture and historically necessary, perhaps the most important step;” Daniel Ortega, the Nicaraguan president and former Sandinista rebel, thought the United States deserved the top spot in a new list of state sponsors of terrorism.85 All of the

afore-mentioned comments are from leaders of leftist regimes and, to a certain extent, represent a breakthrough of Obama’s new diplomatic initiative, which Beijing should not neglect the future development and influence on mainland China’s strategic maneuver there.

Nevertheless, Obama’s effort to reshape policy toward Latin America has been undermined by heavy attacks, mainly from Re-publicans and leaders of Cuban immigrants. Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican hopeful for the 2016 presidential election and son of Cuban immigrants, strongly denounced the normalization with Cube and argued that “this entire policy shift announced today is based on an illusion, on a lie, the lie and the illusion that more commerce and access to money and goods will translate to political freedom for the Cuban people.”86 Of course, his position could affect many of his

Peter Baker, “U.S. to Restore Full Relations With Cuba, Erasing a Last Trace of Cold War Hostility,” The New York Times, December 17, 2014, p. A1.

Simon Romero & William Neuman, “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington.”

Simon Romero & William Neuman, “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington.”

Peter Baker, “U.S. to Restore Full Relations With Cuba, Erasing a Last Trace of Cold War Hostility.”

colleagues in the Congress.

Fortunately, Obama’s diplomatic initiative is shored up by strong support from the U.S people. According to opinion poll conducted by Pew Research Center,8763% of Americans approve of the Obama

administration’s decision to normalize ties with Cuba and open its embassy in Havana after more than 50 years and 66% favor the ending the decades-long U.S. trade embargo against Cuba. It is note-worthy that American young people give stronger support for Obama’s new foreign policy.

V. Conclusion

As leader of one of the poorest countries in Latin America, President Daniel Ortega has a dream and high aspirations for the construction of the Nicaragua Grand Canal. The Ortega family initiated the promotion of the canal project and convinced Sandinista party members to work together. Ortega chose partners from China, Wang Jing and his HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Company. With strong support in the government and parliament, the Canal

Act was passed and the construction agreement was sealed in June 2014.

Strategically speaking, Central America has no attraction for mainland China. South America is the major target of mainland China’s regional policy because of its abundance in mineral resources and foodstuffs, and major trading partners are in the South and Mexico. Central America seems an exception for current mainland China’s resources diplomacy, because nations in that region lack vital

Pew Research Center, “Most Support Stronger U.S. Ties with Cuba,” Pew

Re-search Center, January 16, 2015, <http://www.people-press.org/2015/01/16/

mineral products and their major exports consist of coffee, bananas, and sugar. Costa Rica so far is the only country in Central America to break ties with Taiwan and forge diplomatic relations with Beijing. In the past, mainland China’s only interest in this region was its diplomatic struggle with Taiwan until the diplomatic truce proposed by President Ma Ying-jeou. Nevertheless, the geographic location connecting the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean is the most important asset Central America has. Mainland China has become one of the most important and frequent users of the Panama Canal.

Ever since 2013, when President Xi announced it, “One Belt, One Road” initiative has become mainland China’s grand strategy, at least, for the next ten years. Economically speaking, three financial mechanisms are in good positions for the promotion of “One Belt, One Road.” The first one is BRICS’ New Development Bank, which was formally formed with the Contingency Reserve Arrangement at the 2014 annual summit of BRICS in Brazil. During the 2104 APEC summit, President Xi announced establishment of a $40 billion “Silk Road Fund,” and The Silk Road Fund Co. Ltd. officially registered and commenced operation in December 2104 with $10 billion dollars ready for investment. A third key financial institution is the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which is going to be operational by the end of 2015. One common objective for these three financial institutions is to support and invest in infrastructure construction.

The construction of the Nicaragua Grand Canal must rely upon foreign capital, technology, and equipment, from mainland China in particular. All policy makers, scholars, and experts have agreed that Beijing is behind the scenes of the canal project. According to recent information, many Chinese state enterprises have participated in this project and forged a partnership with HKND. For example, China

Railway Siyuan Survey and Design Group Company; Changjiang In-stitute of Survey, Planning, Design and Research, CCCC Second Harbor Engineering, Investigation, and Design Institute Limited Com-pany, Civil Aviation Engineering Consulting Company of China, and Shenzhen Layout Urban Design Consulting Limited Company are all on board.

Owing to Central America being the real backyard of the United States, mainland China has to be very careful while designing its grand strategy and, consequently, leaving a leak or a hole there. In other words, mainland China does not mention Latin America in its “One Belt, One Road” strategy. Mainland China has paid considerable attention to the position of the U.S. and avoided early and open con-frontation and conflicts in Latin America.

From the preceding analysis, a tentative conclusion is that, with the strong support of the Nicaraguan government and mainland China’s grand strategy, the Nicaragua Grand Canal, sooner or later, will be finished. Mainland China will benefit from the completion of the canal and possess geopolitical and geoeconomic superiority, which, in turn, will assure its influence in this region and in the world.

References

Books

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2012.

The People’s Republic of China and Latin America and the Cari-bbean: Dialogue and Cooperation for the new challenges of the global economy. Santiago, Chile: United Nations.

Fornes, Gaston & Alan B. Philip, 2012. The China-Latin America

Axis: Emerging Markets and the Future of Globalization. New

York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gil, Federico G., 1971. Latin American-United States Relations. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Sanderson, Henry & Michael Forsythe, 2013. China’s Superbank:

Debt, Oil and Influence. Hobokken, N.J.: John Wiley.

Skidmore, Thomas E., Peter H. Smith, & James N. Green, 2010.

Modern Latin America, 7thEdition. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Weeks, Gregory B., 2008. U.S. and Latin American Relations. New York: Pearson Longman.

Zhu, Zhiqun, 2013. China’s New Diplomacy: Rationale, Strategies

and Significance. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. Book Articles

Jilberto, Alex E. F. & Barbara Hogenboom, 2012. “Latin America –from Washington Consensus to Beijing Consensus?” in Alex E. F. Jilberto & Barbara Hogenboom eds., Latin America Facing

China: South-South Relations beyond the Washington Consensus.

New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 181-193.

Leon-Manriquez, Jose Luis & Adrian H. Hearn, 2011. “China, Latin America, and The Trajectory of Change,” in Adrian H. Hearn & Jose Luis Leon-Manriquez, eds., China Engages Latin America:

Levine, Steven I., 1984. “China in Asia: The PRC as a Regional Power,” in Harry Harding ed., China’s Foreign Relations in the

1980s. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 107-145.

Lowenthal, Abraham F., 1999. “United States-Latin American Relations at the Century’s Turn,” in Albert Fishlow & James Jones eds.,

The United States and the Americas. New York: W. W. Norton.

pp. 109-136.

Navejas, Francisco Haro, 2011. “China’s Relations with Central America and the Caribbean States,” in Adrian H. Hearn and Jose Luis Leon-Manriquez, eds., China Engages Latin America:

Tracing the Trajectory. Boulder. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

pp. 203-219.

Zheng, Bingwen, Sun Hongbo, & Yue Yunxia, 2012. “The Present Situation and Prospects of China-Latin American Relations: A Review of the History since 1949,” in Wu Baiyi, Liu Weiguang, He Shuangrong, & Cai Tongchang, ed., China-Latin America

Relations: Review and Analysis, Volume 1. Beijing: Social

Scien-ces Academic Press. pp. 1-21.

Journal Articles

Beauchamp-Mustafaga, Nathan, 2015/3/6. “The New Silk Road and Latin America: Will They Ever Meet?” China Brief, Vol.15, Issue 5, pp.1-3.

Leverett, Flynt, Hillary Mann Leverett, & Wu Bingbing, 2015/1-2. “China Looks West: What Is at Stake in Beijing’s “New Silk Road” Project,” The World financial Review, pp. 6-7.

Teng, Chung-chian. 2007/1. “The Policy and Behavior of the Rising China in Latin America,” The Journal of International Relations, No. 23, pp. 15-55.

Newspapers

fro Oil, IEA Says,” The Wall Street Journal, p. A10.

Baker, Peter, 2014/12/17. “U.S. to Restore Full Relations With Cuba, Erasing a Last Trace of Cold War Hostility,” The New York

Times, p. A1.

Perlez, Jane, 2014/10/10. “U.S. Opposing China’s Answer to World Bank,” The New York Times, p. A1.

Romero, Simon & William Neuman, 2014/12/19. “Cuba Thaw Lets Rest of Latin America Warm to Washington,” The New York

Times, p. A1.

Samuelson, Robert J., 2004/5/26. “Great Wall of Unknowns,” The

Washington Post, p. A27. Online Resources

2013/10/9. “Honduras and China Sign MOU for Interoceanic Railway,”

Resistencia Honduras,

<http://www.resistenciahonduras.net/in- dex.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5882:honduras-and-china-sign-mou-for-interoceanic-railway&catid=101:news& Itemid=349>.

2014/6/14. “Nicaragua’s Ortega, Wang Jing Sign Canal Agreement,”

San Jose Mercury News, <http://www.mercurynews.com/

ci_23465932/nicaraguas-ortega-wang-jing-sign-canal-agreemen>. 2014/7/16. “BRICS voices disappointment with non-implementation of IMF reforms,” China Daily, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/ world/2014-07/16/content_17795098.htm>.

2014/8/27. “Nicaragua’s Trans-Oceanic Canal Survey Leaves Residents Fearful of Losing Homes,” The Guardian, <http://www.theguar- dian.com/world/2014/aug/27/residents-fearful-nicaragua-trans-oceanic-canal-surveys-hknd-group>.

2004/11/10. “China looking to Latin America for resources during Hu trip,” Yahoo News, <http://news.yahoo.com>.

2014/11/6. “Xi Jinping: To accelerate the promotion of the construction of Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk

Road,” Xinhua, <http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2014-11/06/ c_1113146840.htm>.

2004/11/20.“China vows to promote win-win cooperation,” Xinhua, <http://china.org.cn/english/2004/Nov/112737.htm>.

2014/12/24. “Chinese-Invested Nicaragua Canal Has Nothing to Do with Chinese Government,” Chinese Daily, <http://www.chi-nesedaily.com/focus_list.asp? no=c1337043.txt&catid=4&lanmu= Z09&readdate=12-24-2014>.

2015/3/21.“The infrastructure gap: Development finance helps China win friends and influence American allies,” The Economist, <http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21646740-development- finance-helps-china-win-friends-and-influence-american-allies-infrastructure-gap?fsrc=nlw|hig|19-03-2015|>.

2015/3/21.“Switzerland, Luxembourg apply for China-led infrastructure bank,” RT, <http://rt.com/business/242897-switzerland-luxem-bourg-aiib-china/>.

Banyan, 2013/10/4. “An Asian infrastructure bank: Only connect,”

The Economist, <http://www.economist.com/blogs/analects/2013/

10/asian-infrastructure-bank-1>.

Brice, Arthur, 2009/6/3. “OAS lifts 47-year-old Suspension of Cuba,”

CNN, <http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/americas/06/03/cuba.

oas/index.html?_s=PM:WORLD>.

Donath, Mirjam & Louis Charbonneau, 2014/10/28. “For 23rdTime,

U.N. Nations Urge End to U.S. Embargo on Cuba,” Reuters, <http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/10/28/us-cuba-un-idUSK BN0IH1RN20141028>.

Eustace, Ryan & Ronn Pineo, 2014/7/28. “The BRICS’ New Financial Initiatives: Good For Whom?” COHA Research, <http://www. coha.org/the-brics-new-financial-initiatives-good-for-whom/>. Flannery, Russell, 2013/10/31. “Nicaraguan President’s Son Laureano

Ortega Discusses $40 Bln Canal During China Visit,” Forbes,