Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 45, no. 1 (June 2006) © by University of Hawai‘i Press. All rights reserved.

The Pragmatics of Case Marking

in Saisiyat

Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang

graduate institute of linguistics, national taiwan university Saisiyat, an Austronesian language spoken in northwest Taiwan, has an elaborate case marking system for nominals and pronominals, but the nominative case is often zero marked. Based on natural spoken data, we demonstrate that this absence of nominative case markers is closely tied to the ongoing word order shift from a V-initial language to a strongly subject-initial language, especially in Agent-Focus sentences, rendering any marking for the nominative case pragmat-ically redundant. Nominative case marking remains a pragmatic option for the presentative construction to introduce a new referent into discourse. A second issue addressed concerns the coding of the Recipient in a ditransitive sentence. We present an unusual case of biaccusative constructions where the semantic role of the Recipient is marked by either the dative or the accusative case marker, the choice being pragmatically determined by the spatial or psychological dis-tance between the Agent and the Recipient. If the Recipient is perceived as being within the spatial or psychological sphere of in³uence of the Agent and conse-quently likely to be affected by the action of the Agent, the accusative case is pre-ferred; elsewhere the dative is used. The effect of this is to produce biaccusative constructions, because the Theme in ditransitive sentences is always coded by the accusative case. Case marking in Saisiyat therefore cannot be dissociated from the discourse-pragmatics of language use and an understanding of the nature of the word order change the language is currently undergoing.

1. INTRODUCTION.1 Saisiyat, a moderately endangered Austronesian language,

is spoken by indigenous people inhabiting the mountain areas in northwest Taiwan, with a population of about 5,000.2 Two mutually intelligible dialects are usually distin-guished: the Taai dialect in the north and the Tungho dialect in the south. The latter is 1. The research reported here was supported by a research grant from Taiwan's National Science Council to the second author. An early version of this paper was presented at the Annual Confer-ence of American Applied Linguistics held at Portland, Oregon, May 1–4, 2004 and at the Sec-ond Workshop on Discourse and Cognition held at Taiwan University, May 12, 2005. We thank the participants at these conferences for their comments. We would also like to thank our Saisiyat informants for sharing their expert language skills and astute linguistic intuitions: ’oemaw a ’obay tawtawazay ‘Shan-ho Chao’ (Taai dialect), bownay a taheS ‘Te-hui Fong’, waun a bo:ong babayi’ ‘Yu-yun Fong’, kalaeh a taro’ ‘Shiu-lang Fong’, parayin a ’oemaw ‘Te-hseng Kao’, kalaehya ’oemaw ‘A-liang Chu’, lahi’ a taro’ babayi’ ‘Jian-fu Fong’, lalo’ a taehes kaybay-baw ‘Yu-mei Kao’, and awe’ a basi’ ‘Fan-hsiung Rih’. The ²rst author acknowledges the support of a travel grant by the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange. 2. http://others.apc.gov.tw/popu/9406/aprp5803.htm

the one reported on here. The main differences between the two dialects involve their phonology and lexicon (Li 1978b; Yeh 1991, 2000, 2003).

Blust (1999), based largely on phonological grounds, groups Saisiyat together with Kulon-Pazeh under the Northwest Formosan branch of the Austronesian family. A great majority of the Formosan languages share the following structural features: (a) they are verb-initial, and (b) they are morphologically ergative languages. Saisiyat differs in that it is strongly subject-initial and is shifting into an accusative language, while still exhibiting features of split-ergativity.3

In this paper two unusual features of case marking in Saisiyat are addressed. First, its nominative and accusative case markers share a morphologically identical form, and the marking on the nominative argument NP in the Agent Focus (af) construction tends to be absent, a phenomenon that was explained by earlier researchers on Formosan lan-guages as a process of deletion. Second, the semantic role of the Recipient in a ditransi-tive sentence is marked by either the daditransi-tive or the accusaditransi-tive case marker. We demonstrate below that the choice between these two cases is pragmatically determined by the spatial or psychological distance between the Agent and the Recipient. When the Agent is spatially closer to the Recipient, or feels that the Recipient is closer to him/her and consequently that his/her action is perceived as having an impact on the Recipient, the accusative case is preferred; elsewhere the dative is used.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a brief sketch of the Saisiyat lan-guage, with a focus on its case marking system and the focus system. Section 3 states our research questions. The pragmatic factors governing the choice of the nominative case marker are discussed in section 4. Section 5 discusses the spatial/psychological factors that determine the selection of the accusative and the dative in encoding the Recipient in some ditransitive constructions. Section 6 is the conclusion.

2. A BRIEF SKETCH OF THE SAISIYAT GRAMMAR.Saisiyat has an

elabo-rate case marking system for nominals and pronominals. The nominal case markers in Saisiyat are categorized into six cases, and each can be divided into two sets: one for personal nouns and the other for common nouns. The pronominal system and the nominal case marking system are given in tables 1 and 2, respectively.

There are two sets of focus marking systems in Saisiyat.4 Set I is used in present declarative sentences or in negative sentences containing the negators kayni’ and ’okik, while Set II is used in the imperative or in negative sentences containing the negators ’okay, ’izi’, and ’in’ini’. The focus markers can be categorized into four types: agent focus (af), patient focus (pf), locative focus (lf), and referential focus (rf), which can be further divided into instrumental focus (if) and benefactive focus (bf), as summa-rized in table 3. Below we use corpus sentences to illustrate how the focus system 3. See Hsieh and Huang (submitted) “Saisiyat as a split ergative language” for a fuller discussion

of the issues involved.

4. An emerging consensus among Austronesian linguists is that these are not focus markers, but rather markers of a voice system, if we understand voice alternations in terms of syntactic con-structions with speci²c grammatical characteristics and attendant pragmatic effects (cf. Starosta 1986; Chang 1997; Himmelmann 2002; Ross 2002). Ross and Teng (2005) reformulate the focus system of Puyuma as a transitivity system (see Huang [2005] for a similar view). In defer-ence to tradition, however, we will continue to use the term “focus” in the present study.

works. In the af construction, the thematic role of the nominative NP can be an Agent, as with sia ‘he’ in (1), an Experiencer, as with korkoring ‘child’ in (1), or a Theme, as with ka binisitan ‘bottle’ in (2), while that of the accusative NP can be a Patient, as with

ka hinoehas ‘window’ in (1), or a Goal, as with ka ’aehoe’ ‘dog’ in (1).5

TABLE 1. THE PERSONAL PRONOMINAL SYSTEM IN SAISIYAT †

† From Yeh 2003:17.

nominative accusative genitive dative possessive locative

sg

1 yako/yao yakin/iyakin ma’an ’iniman ’amana’a kanman

2 So’o ’iso’on niSo ’iniSo ’anso’o’a kanSo

3 sia hisia nisia ’inisia ’ansiaa kansia

pl

1.incl ’ita ’inimita mita’ ’inimita’ ’anmita’a kan’ita 1.excl yami ’iniya’om niya’om ’iniya’om ’anya’oma kanyami

2 moyo ’inimon nimon ’inimon ’anmoyoa kanmoyo

3 lasia hilasia nasia ’inilasia ’anlasiaa kanlasia

TABLE 2. THE CASE MARKING SYSTEM†

† From Huang, Su, and Sung (n.d.), chap.3.

noun nom acc gen poss dat loc

personal name Ø

hi hi ni ’an-a ’ini’ kankala

common noun Ø

ka ka noka ’an noka-a no ray

TABLE 3. THE FOCUS SYSTEM

focus I II

Agent Focus m-, -om-, ma-, Ø Ø

Patient Focus -en -i

Locative Focus -an

Referential Focus si- / sik- -ani

5. Abbreviations and symbols used in this study include ’ for the glottal stop and : for long vowels (with the latter following the orthography promulgated at http://www.apc.gov.tw/of²cial/news/newsde-tail.aspx?no=847 by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan).Nonstandard abbreviations used (those not included in the Leipzig Glossing Rules): af, Agent Focus; pf, Patient Focus; lf, Locative Focus; rf, Referential Focus; if, Instrumental Focus; bf, Benefactive Focus; asp, aspectual marker; pn, proper noun/personal name; pro, pronoun; red, reduplication; fs, false start; int, interjection; lnk, linker; fil, pause ²ller; dm, discourse marker. Symbols for discourse coding are based on the system of Du Bois et al. (1993): [ ] speech overlap; -- truncated utterance; : speaker identity; . ²nal intonation; , con-tinuing intonation; \ falling pitch; / rising pitch; _ level pitch; ^ primary accent; …(N) long pause; … medium pause; .. short pause; = lengthening; (0) latching; @@ laughter.

(1) SyNr-Frog 8

1.. Korkoring k<om>i-kita’ ka=,\6

child <af>red-look.at acc 2.. (0.8) ’aehoe’,\.

dog

‘The child was looking at the dog.’ ….

9 …(2.1) Sia hawah ka hinoehas.\.

3sg.pron.nom af.open acc window ‘He opened the window.’

(2)

SyNr-Frog 4

31.…(2.0) Isaa ka= binisitan minlakay ila hiza’,_ … that nom bottle af.break pfv that ‘The bottle broke, …’

In the pf construction, the thematic role the nominative NP assumes is usually the Patient, while the genitive NP usually encodes the thematic role of the Agent, as in (3):

(3) SyNr-Frog 7

37 … Mari’-in noka ma’iaeh awpo’-on ila

’aehoe’.\.

take-pf gen person carry-pf pfv dog ‘The person took and carried the dog.’

The lf form appears only in equational sentences to denote the place where an event or activity takes place, as shown in (4):

(4)

ka-sia’el-an hini’

ka-eat-lf.nmlz here

‘Here (is the place) where we eat.’

The rf construction has a number of closely related functions and can be easily recog-nized by its morphological form: the verb root is pre²xed with the morpheme si- or

sik-. Generally speaking, the genitive argument of an rf construction encodes the Agent of an action or the Experiencer of an emotion event, while the nominative argu-ment may be the Cause (5a), the Bene²ciary (5b), or the Instruargu-ment (5c).

(5) a. Noka korkoring ka ’aehoe’ si-haengih.

gen child nom dog rf-cry

‘The child cried for the dog.’

(cause) b. Korkoring si-Sebet ni ’oya’ hi Kizaw.child rf-beat gen mother acc pn

‘Mother beat Kizaw for the child.’

(beneficiary) c. Kahoey si-Sebet ni ’oya’ ka korkoring.wood.stick rf-beat gen mother acc child

‘Mother beat children with the wood-stick.’

(instrument) 6. Note that Saisiyat does not specify number in its nouns, nor does it have de²nite articles.Therefore, ka korkoring can refer to ‘a child’, ‘the child’, ‘children’, or ‘the children’. The speci²c interpretation is sensitive to contextual information.

3. THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS. Ogawa and Asai (1935) ²rst reported that ka

and hi are both nominative and accusative case markers. Starosta (1974) noted that ka, hi, and Ø werenominative case markers. Li (1978a:601) maintains that the nominative case does not have any overt case marker. Yeh (1995b) argues that ka and hi are both nomina-tive and accusanomina-tive case markers, but interprets the zero marking of the nominanomina-tive case ²rst observed by Starosta (1974) and Li (1978a) as an ellipsis phenomenon, while also noting that “… the nominative case markers are now on the way of dropping” (Yeh 1995b:38). A detailed examination of our corpus data reveals that intransitive af clauses are realized in either SV or VS constructions and that most of the preverbal subjects tend to be zero-marked, while nearly all of the postverbal nominative NPs are overtly marked. The question that arises then is: Are marked (with the marker ka or hi) and zero-marked nominative forms free variants? Or are they constrained by discourse-pragmatic factors?

The second question that we address concerns the competition between the accusa-tive and the daaccusa-tive case for encoding the thematic role of Recipient in “ditransiaccusa-tive” sentences in Saisiyat. Sentences (6a) and (6b) are taken from our ²eld notes:

(6) a. Sia

’

am mo-bay ka’

aehae’ kakaat ka korkoring. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen acc child ‘He will give the child one pen.’b. Sia

’

am mo-bay ka’

aehae’ kakaat no korkoring. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen dat child ‘He will give the child one pen.’These Saisiyat data suggest that in a ditransitive sentence with a predicate like mo-bay ‘af-give’, Saisiyat seems to have differential strategies for conceptualizing the Recipi-ent korkoring ‘child’: the RecipiRecipi-ent is encoded by either the accusative case ka or the dative no. The difference between (6a) and (6b) cannot be dismissed as a simple instance of free variation, but hinges on the perceived physical or psychological dis-tance between the Agent and the Recipient in events involving transfer of an object from one individual to another. Before we take up the speci²cs of our proposal, we ²rst introduce our methodology and database.

4. DATA AND FINDINGS

4.1 METHODOLOGY AND DATABASE. The present study is based on

nar-rative data and ²eld notes collected between October 2002 and April 2005. The narra-tive data are taken from an evolving National Taiwan University Spoken Corpus of Formosan Languages and consist of four Pear stories, eight Frog stories, and four Saisiyat folk stories,7 which together run to 70 minutes, for a total of 1805 intonation units (IUs). All the narrative data were transcribed into IUs as part of a large project to study the interaction between grammar and prosody. In all the corpus sentences used to illustrate speci²c points below, each line represents an intonation unit and corresponds oftentimes to a grammatical clause.

7. These four Saisiyat folk stories are ’anhi ‘bamboo.shoot’, molaw ‘molt’, kathethel ‘Goddess of Thunder’, and the Flood Story.

4.2 RESULTS AND FINDINGS. Only nonpronominal subject and object NPs

in af clauses were surveyed for the behavior of the case markers that we focus on in the present study. The reason we examined the af clauses only is that based on Huang, Su, and Sung (n.d.:44–47), the occurrences of af clauses in the narrative texts account for 75.9 percent of all clause tokens, as shown in table 4.8

Because word order is an important element, we counted separately preverbal and postverbal nominative NPs and accusative NPs; we further separated the subjects of one-place verbs (i.e., the Ss) from the subjects of the two-one-place verbs (i.e., the As) in our count. First, we look at the behavior of nominative NPs. As shown in table 5, as many as 79 percent of preverbal nominative NPs (both Ss and As) are zero-marked. As further revealed in table 6, while As occur only in the preverbal position and 81 percent (48 out of 59) of them are zero-marked, Ss can occur both preverbally and postverbally, with

8. As a comparison, the distribution patterns of focus forms in Seediq and Tsou are shown in the following table, taken from Huang 2002b:674, tables 4 and 5.

Seediq Tsou

narratives conversation narratives conversation

af 413 (78%) 130 (80%) 198 (58.4%) 111 (65%)

naf 117 (22%) 32 (20%) 141 (41.6%) 60 (35%)

totals 532 162 339 171

TABLE 4. DISTRIBUTION OF THE AF AND NAF CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE TEXTS

narrative conversation total

af construction 532 75% 88 84% 620 75.9%

naf construction 180 25% 17 16% 197 24.1%

total 712 105 817

TABLE 5. DISTRIBUTION OF ka/hi-MARKED AND ZERO-MARKED NPS IN THE TEXTS

preverbal position postverbal position

Nominative (S/A) Accusative Nominative (S/A) Accusative

ka/hi-marked 51 (21%) 0 72 (93%) 162 (100%)

Ø-marked 192 (79%) 0 4 (7%) 0

total 243 0 76 162

TABLE 6. DISTRIBUTION OF ka/hi-MARKED AND ZERO-MARKED NPS WITH S/A SEPARATED

preverbal position postverbal position

S A O S A O

ka/hi-marked 40 (21.74%) 11 (18.64%) 0 72 (93%) 0 162 (100%)

Zero-marked 144(78.26%) 48 (81.36%) 0 4 (7%) 0 0

78.3 percent of the preverbal Ss zero-marked and 93 percent of all postverbal nominative NPs overtly marked.

All the accusative-marked NPs occur in the postverbal position and they are all overtly marked. Absence of an accusative case marker simply does not occur in our data. Based on the fact that the Os are consistently postverbal and the As are consis-tently preverbal, we conclude that the word order in Saisiyat af dyadic clauses is now highly rigid, i.e., AVO. This means that innovation in the ongoing word order shift to a more subject-initial language must have originated with the af clauses and is propagat-ing to the non-af clauses, where variability in word order is much greater.

Only the case marking on the nominative NPs in intransitives exhibits a divergent pattern. In preverbal position, most of the nominative arguments are zero-marked (144 out of 184, or 78 percent); on the other hand, in postverbal position, they are nearly always marked. The only exceptions to this rule in our corpus data are four VS clauses where the Ss are numeral NPs referring to inde²nite entities, as shown in (7) and (8).9

(7) SyNr-Flood

4 … (2.8) M-wa:i’ ila ’aehae’ ma’iaeh.\ af-come pfv one person 5 … (0.8) rima’,\.

af.go

6 … M-ayaka:i’ka ’imahaba:an k<om>oSa’=,\ af-say acc ima.many <af>say 7 … (0.8) paskayzaeh ka palono’.\.

af.do acc boat

‘There came a man. (He) said to many people (and) told (them to) build a boat.’

(8) SyNr-Pear 3

26 … (1.3) M-wa:i’ to:o’ ma’iaeh korkoring.\ af-come three person child

27 … (1.9) tatilhaehael r<om>okrok ka boway,\ af.help <af>pick acc fruit

28 … (1.5) boway mari’-in papayhae’hae’-en ray .. kala’.\. fruit take-pf fully.²lled-pf loc basket

‘Three children came and helped (the boy) pick up the fruit and put (them back) in the basket.’

4.3 DISCUSSION. What initially attracted our attention was the differential behavior

of the case marking of the intransitive subjects in various sentence types. As stated above, most of the preverbal Ss are zero-marked (78 percent), while nearly all of the postverbal Ss are overtly marked (93 percent, the percentage would be 100 percent, if we disregard the 9. If the numeral NPs refer to de²nite entities, they tend to be case-marked, as in (9) further below. The syntax of the numeral NPs in Formosan languages is known to differ from other types of NPs (cf. Li 2006). For example, a ligature is always required between a numeral and the head noun in Thao, Rukai (in Maga and Tanan), Pazih, and Atayal (in Mayrinax). In Kavalan, a suf²x -ay, which is identi²ed variously as a nominalizer (Hsin 1996; Lee 1997; Li 1997, 2006) or as a relativizer (Chang and Lee 2002; also see Hsieh and Chen 2006 for an alternative analysis), is always required between a numeral and the head noun.

four sentences containing numeral NPs), as shown in table 6. It is thus worth exploring what factors may have been responsible for such a difference in case marking.

First, we examined the semantic classes of the verbs that the intransitive clauses co-occur with to see if there is any interesting correlation. The results are shown in table 7. Verbs in Type A are CHANGE-OF-LOCATION verbs and they are used to denote a referent moving away from some location. Type B verbs, PARTICIPANTREMOVAL verbs such as ‘disappear’ and ‘run away’, denote an event participant removing himself or herself from the scene. Type C is the EXISTENTIAL verb. These three types of verbs are frequently used in the presentative VS construction to introduce a new referent into the discourse. Based on table 7, it seems quite natural to draw a line that separates the ²rst three types of verbs from the other four types. Nearly all the VS constructions cooccur only with the ²rst three types of verbs (63 out of 72, or 88 percent), while the preverbal Ss, which are as shown above to be largely zero-marked, go with the other four types of verbs (Type D to G). Because SV and VS constructions have very different pragmatic functions, an expla-nation based purely on the semantics of the verbs in these constructions cannot be right. A more plausible explanation must be sought in the differential pragmatic functions that the two types of Ss appearing in the SV and VS clauses exhibit. To determine whether there is a discourse basis to such a functional split in the Ss, we adopt Givón’s (1983a:13) strategy and assess the gap between the previous occurrence in the discourse of a referent and its current mention in a clause, count the mean referential distance of each S, the results of which are summarized in table 8.

Table 8 says that the mean referential distance of postverbal Ss is about three times greater than that of preverbal Ss (17.48 vs. 6.13). This means that the distance between the current mention and the last mention of the Ss in the VS construction is on the aver-age more than 17 clauses, while that of the Ss in the SV construction is about 6 clauses.

TABLE 7. TYPES OF INTRANSITIVE VERBS IN SV OR VS CONSTRUCTIONS

Verb Types Examples SV VS

A change-of-location

m-wai’ ‘af-come’, kas’oehaz ‘AF.move.out’, sathang ‘af.appear’ 27 21 B participant

removal

’oka’ ‘af.be.not.seen; af.disappear’, raiw ‘af.run.away’ 7 17

C existential hayza’ ‘af.exist’ 1 25

D activity papama’ ‘af.ride’, <oem>oe’oe ‘<AF>call’, h<oem>ayap ‘<af> ³y’ 63 3 E perception k<om>ita’ ‘<AF>see’, s<om>azek ‘<AF>smell’ 18 0 F emotion homses ‘AF.be.frightened’, boe’oe: ‘AF.be.angry’, siya’ ‘AF.be.happy’ 12 0 G stative hoepay ‘AF.be.tired’, kayzaeh AF.be.good’ 16 6 totals144 72 TABLE 8. MEAN REFERENTIAL DISTANCE OF VS AND SV

SV (144) VS (72) (1) Mean referential distance (MRD) 6.13 17.48 (2) Subjects with previous reference in

Furthermore, from table 8 we can also see that a great majority of the preverbal Ss can be found to have their previously mentioned references in the preceding 20 clauses (121 out of 144), while only 6 out of 72 of the postverbal Ss are found to have their previous refer-ences in the preceding 20 clauses. Indeed, postverbal Ss are predominantly used in the ²rst mentions, and are rarely if ever used to do referent-tracking, as shown in table 9.

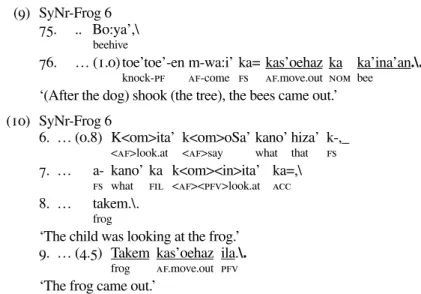

We therefore conclude that there is a clear functional split in the Saisiyat Ss. The postverbal subjects are overtly case-marked and occur in the presentative constructions to introduce a ²rst-mention entity into the discourse. We illustrate this with examples from our corpus data.

(9) SyNr-Frog 6 75. .. Bo:ya’,\

beehive

76. … (1.0) toe’toe’-en m-wa:i’ ka= kas’oehaz ka ka’ina’an.\. knock-pf af-come fs af.move.out nom bee ‘(After the dog) shook (the tree), the bees came out.’ (10) SyNr-Frog 6

6. … (0.8) K<om>ita’ k<om>oSa’ kano’ hiza’ k-,_ <af>look.at <af>say what that fs 7. … a- kano’ ka k<om><in>ita’ ka=,\

fs what fil <af><pfv>look.at acc 8. … takem.\.

frog

‘The child was looking at the frog.’ 9. … (4.5) Takem kas’oehaz ila.\.

frog af.move.out pfv ‘The frog came out.’

Excerpt (9) is taken from one of the Frog stories.10 The narrator is talking about a little boy and his dog looking for his frog in the woods, where they experience a series of adventures. Here they see a beehive and the dog barks at it and shakes the tree, which causes the beehive to fall to the ground, and all the bees swarm out as a result. In line 76, the narrator uses a VS construction to introduce these new entities into the narra-tive. By comparison, the narrator in (10) uses a SV construction to describe an event of an already introduced entity, that is, the frog. On the next page is another example.

10. Frog stories are elicited narratives where narrators were asked to narrate to the transcribers the story of a wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer 1969). The stories were then transcribed into intonation units based on Du Bois et al. (1993).

TABLE 9. FIRST MENTION AND NONFIRST MENTION OF TYPES OF S

SV VS

First mention 13 (9.03%) 66 (91%)

Non²rst mention 131 (90.97%) 6 (9%)

(11) SyNr-Molaw

6. … (1.4) Hiza= hayza’ ila koSa’en ka SaiSiyat.\.

there exist pfv fil nom pn

‘Then there were Saisiyats.’

7. … (1.8) SaiSiyat hayza’ ila lasia so:,\ pn exist pfv 3pl.pron.nom if 8. … ’i’iyah o:=,_

af.live dm

9. .. tatini’ ila nanaw.\ af.grow.old pfv still

‘Saisiyats existed. When they lived till they grew old, …’

Excerpt (11) is taken from a legend about the Saisiyat ancestor. In Saisiyat folk-lore, it is said that in the distant past, Saisiyat people never died; they, like snakes, just molted. When a Saisiyat became old, he would molt and then a new fresh Saisiyat young man would emerge. In line 6, the narrator begins his story by saying that a long time ago under the sky, there existed Saisiyats. After he introduces a new referent identi²ed by ka SaiSiyat with a VS construction in line 6, he shifts to a SV construction to continue his narration about the new referent in line 7.

We have thus shown that the absence of the nominative case marking on the prever-bal S/A in Saisiyat is closely tied to the ongoing word order change from a V-initial language to a strongly subject-initial language, especially in Actor-Focus construc-tions, rendering any marking pragmatically redundant. We have also shown that intran-sitive subjects exhibit a fairly clear-cut functional split. Nominative case marking is a pragmatic option for the presentative construction. When a referent is introduced into discourse for the ²rst time, the preferred strategy of the language is to use VS construc-tions, where the intransitive subject is always coded by the nominative case marker. The SV construction is used otherwise.

5. COMPETITION BETWEEN ACCUSATIVE AND DATIVE IN THE CODING OF RECIPIENT. In this section we investigate case marking of the

the-matic role of the Recipient in Saisiyat ditransitive constructions. Consider ²rst the follow-ing sentences in Saisiyat.

(12) a. Yao wakik ka laleke: no korkoring. 1sg.pron.nom af.wind acc telephone dat child

‘I made a phone-call to the child; I gave the child a phone-call.’ b. Yao wakik ka laleke: ka korkoring.

1sg.pron.nom af.wind acc telephone acc child ‘I gave the child a phone call.’

In (12a) the noun laleke:‘telephone’ is coded by the accusative, serving as the Theme of the verb wakik ‘to wind’, and the NP korkoring ‘child’ is marked by the dative case and serves as the Recipient, the entity that receives the phone call. What is unusual is (12b), in which both the Theme and the Recipient are marked by the accusative, resulting in a biaccusative construction.11 The readings of these two sentences are the same: ‘I gave the child a phone call/I made a phone call to the child.’

Identical markings of the Theme and the Recipient also appear in (13–15), where the main verb is mo-bay ‘to give’.

(13) a. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat ka korkoring. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen acc child ‘She will give the child one pen.’

b. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat no korkoring. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen dat child ‘She will give the child one pen.’

(14) a. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat hi ’Obay. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen acc pn ‘She will give Obay one pen.’

b. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat ’ini’ ’Obay. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen dat pn ‘She will give Obay one pen.’

(15) a. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat hisia. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen 3sg.pron.acc ‘She will give him one pen.’

b. Sia ’am mo-bay ka ’aehae’ kakaat ’inisia. 3sg.pron.nom fut af-give acc one pen 3sg.pron.dat ‘She will give him one pen.’

These sentence pairs do not differ in construction type, because the Recipients in the sen-tences are encoded as arguments, and neither no korkoring in (13b) nor

’

ini’

’

Obay in (14b) nor’

inisia in (15b) can be interpreted as a benefactive adjunct (cf. Goldberg 2002). These Saisiyat data reveal one important linguistic truth. In a three-place predicate, Saisiyat deploys differential strategies in conceptualizing the Recipient: it is marked either by the accusative or by the dative. The question then is: What is the factor that con-strains the choice between the accusative and the dative? We demonstrate below that the choice is determined by the spatial or psychological distance between the Agent and the Recipient. If the Recipient is perceived to be within the spatial or psychological sphere of in³uence of the Agent and is consequently likely to be affected by the action of the Agent, then the accusative case is preferred; otherwise, the dative is used.5.1 CASE MARKING IN THREE-PLACE PREDICATE CONSTRUC-TIONS. It is well known that, as a cross-linguistic generalization, only one semantic role

of each type may be permitted to occur in a single clause, and thus it is unusual to ²nd two 11. Note that, as expected, the transitive causative construction in Saisiyat also exhibits a bi-accusative coding pattern, where both the causee and patient are marked by the accusative case (cf. Comrie 1975:11–19; Comrie 1976:276–77; Kozinsky and Polinsky 1993:180–81).

(i) Yao pa-tbok hi ’Obay ka waliSan.

1sg.pron.nom caus-af.kill acc pn accwild.pig ‘I made Obay kill a wild pig.’

(ii) ’Oya’ pa-si’ael ka korkoring ka ’alaw. mother caus-af.eat acc child acc ²sh

distinct patients cooccurring in a single clause (Fillmore1968; Blake 2001:66; Goldberg 2002:334). Nevertheless, three-place predicate constructions are known to exhibit various patterns of case marking that may go against this apparent near-universal. Newman’s (1998) cross-linguistic study on the ‘give’ construction found that though it appears that all languages allow the Giver to function as an AGENT, languages differ in the way in which they conceptualize the other two entities, namely, the Theme (T), and the Recipient (R). For example, Mâori allows only the T as OBJECT, Ojibwa and Ttzotzil tolerate only the R as OBJECT, while both types are found in West Greenlandic (Newman 1998:3). Croft (1990:102) also observes that while most European languages treat T in the same way as P, that is, as Direct Object, and treat R differently, as indirect object, languages like Yoruba and Yokuts treat R in the same way as P, and treat T differently. The combination of R+P is referred to as the primary object, and T is the secondary object (see Dryer 1986 for a detailed discussion).12 Saisiyat constructions like those in (15b) and (16a) suggest that Saisiyat makes use of the primary-secondary object distinction as well as the more basic direct-indirect object distinction found in (15a) and (16b). In the next section we examine in further detail the case-marking system of the ‘give’ and allied constructions in Saisiyat.

5.2 RECIPIENTS AND ‘GIVE’ CONSTRUCTIONS IN SAISIYAT. We

have shown that in Saisiyat ‘give’ constructions, the Giver and the Theme are invari-antly marked by the nominative and the accusative, respectively, and that the language allows the Recipient to be coded by either the accusative or the dative, as schematized in (16a–b).

(16) case marking of the three entities in a ditransitive sentence

giver (a) theme (t) recipient (r)

a. Nominative Accusative Dative

b. Nominative Accusative Accusative

Cross-linguistically, the dative case can also encode a Bene²ciary role, because one feature typical of the “giving” situations is that the Recipient usually makes some use of the Theme for his/her own bene²t (Newman 1998:13–18). Thus the thematic role of Bene²ciary and that of Recipient are usually con³ated and encoded with the same case marker in many languages.

Such a con³ation of thematic roles is not possible in Saisiyat, however, although the dative can indeed mark either the Bene²cary or the Recipient in the language. We exemplify this point with the following pairs of sentences (17), (18), and (20) (repeated from [12]) below:

(17) a. ’Oya’ ’am t<om>alek ka pazay hi Kizaw. mother fut <af>cook acc rice dat pn ‘Mother is cooking rice for Kizaw.’

b. *’Oya’ ’am t<om>alek ka pazay ka Kizaw. mother fut <af>cook acc rice acc pn

‘Mother is cooking rice for Kizaw.’

12. In Croft (1990) and Dryer (1986), R (Recipient) is referred to as G (Goal), but the difference is purely terminological.

(18) a. Yao baehi’ ka kaiba:en

’

ini’’

Obay. 1sg.pron.nom af.wash acc clothes dat pn ‘I wash clothes for Obay.’b. *Yao baehi’ ka kaiba:en hi ’Obay.

1sg.pron.nom af.wash acc clothes acc pn ‘I wash clothes for Obay.’

(19) Yao t<om>alek ka ’alaw ka-pa-si’ael ka korkoring. 1sg.pron.nom <af>cook acc ²sh ka-caus-af.eat acc pn ‘I cook ²sh for the child to eat.’

(20) a. Yao wakik ka laleke: no korkoring.

1sg.pro.nom af.wind acc telephone dat child ‘I gave the child a phone-call.’

b. Yao wakik ka laleke: ka korkoring.

1sg.pro.nom af.wind acc telephone acc child ‘I gave the child a phone call.’

Sentence (17) says that ‘mother is cooking rice for Kizaw’, and (18) says that ‘I wash clothes for Obay’. The Bene²ciary is marked by the dative in (17a) and (18a), which are predictably acceptable in Saisiyat. Note that the Bene²ciary can not be coded by the accusative, as (17b) and (18b) are rejected by our Saisiyat informants. When the Saisiyat speaker wishes to say things like, ‘I cook ²sh for the child to eat’ they would use a serial verb construction like (19), an altogether different construction. By contrast, native Saisiyat speakers do not accept a bene²ciary reading of the animate argument no

korkor-ing ‘DAT child’ in (20a). In other words, (20a) cannot be interpreted as “I did the activity of phone-calling for the child’, and the only correct reading is ‘I gave the child a phone call’. Sentence (20b) also disallows a bene²ciary reading. At one level, the interpretations of the pair in (20a) and (20b) are the same in that the activity of making a phone call is performed. At another level, however, there are subtle yet clear pragmatic differences between them: (20b) implies that the child is psychologically closer to the speaker (either that the child and the speaker are emotionally close or that the child means a lot to the speaker), while the use of (20a) does not have such an implication.

As another illustration, consider another pair of examples: (21) a. Yao pasibaeaeh ka rayhil hi ’Obay.13

1sg.pro.nom af.lend accmoney acc pn

‘I lent money to Obay (as Obay came to me in person).’ b. Yao pasibaeaeh ka rayhil ’ini’ ’Obay.

1sg.pro.nom af.lend accmoney dat pn

‘(A third party came to borrow money for Obay; and) I lent money to Obay.’

13. The verb pasibaeaeh ‘af.lend’, though containing the causative marker pa-, is now lexicalized and thus can not introduce an extra argument, as would be the case with a syntactic causative. Quite a few lexemes with the causative pre²x pa-/pak- behave analogously, e.g., papama’ ‘to ride’ vs. pama’ ‘to back-pack’; paoka’ ‘to use up; to spend’ vs. pak-oka’ ‘to cause to disap-pear; to cause to become null’; pakomoSa’ to believe; to think as’.

In (21) Obay is the Recipient and it can be case-marked either by the accusative (21a) or the dative (21b). Again, there are important differences in the interpretations of the two sentences: in (21a), the sentence is used in situations where it was Obay who per-formed the activity of money-borrowing, and I directly lent him the money; (21b) implies that a third party did the activity of borrowing for Obay and so I did not give the money directly to Obay himself, though there is a loan-debt relationship between me and Obay.

When does the language allow its Recipients to be coded as either the accusative or the dative? Below, we use another verb baiw ‘to buy’ to illustrate how recipients may allow an Accusative-Dative competition.

(22) a. Yao baiw ’aehae’ ka kinaat ’ini’ ’Obay. 1sg.pro.nom af.buy one acc book dat pn ‘I bought a book for Obay.’

b. *Yao baiw ’aehae’ ka kinaat hi ’Obay. 1sg.pro.nom af.buy one acc book acc pn ‘I bought Obay a book.’

In English, I bought a book for John is ambiguous between the reading where (for)

John is interpreted as a Bene²ciary (John is busy now, I do the buying for him, and he pays for the Theme) and John as a Recipient (I wanted to give John a book, I did the activity of buying, I paid for the Theme, and then I gave the Theme to John, and John received and thus possessed the Theme). The ambiguity arises because the Bene²ciary and the Recipient are con³ated in the English sentence. However, the thematic role con³ation does not occur in the Saisiyat ‘buy’ construction. In (23a) the argument marked with the dative case can only be interpreted as the Bene²ciary, never the Recip-ient. This means that the verb baiw is a monotransitive, not a ditransitive, verb.14

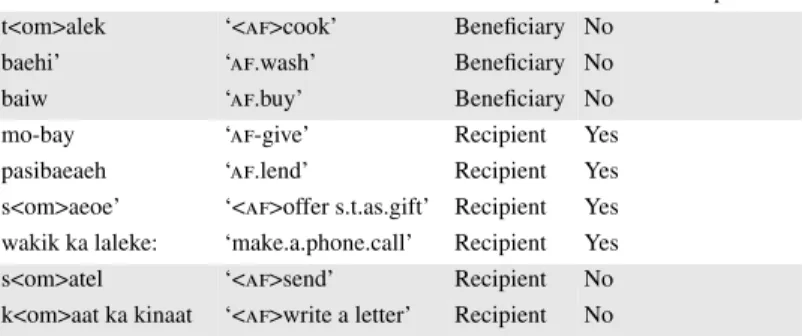

Thus, though both the Bene²ciary and the Recipient in Saisiyat are marked by the dative, these two thematic roles are not con³ated, and only the Recipient is coded as either the dative or the accusative. Such a “competition” between the dative and the accusative with respect to a number of ditransitive verbs is summarized in table 10. 14. An informal survey of Squliq Atayal, Kavalan, Tsou, Cebuano, and Malay suggests that

non-con³ation of the roles Benefactive and Recipient appears to be a pervasive feature of the west-ern Austronesian languages. The verbs that correspond to ‘buy’ in these languages, unlike the ‘give’ verb, are monotransitive and their Benefactive must be coded as an adjunct, as shown in the following Malay examples (Siaw-Fong Chung, pers. comm.):

(a) Hasnah mem-beri kek itu kepada Asri. pn mem-give cake that to pn ‘Hasnah gives that cake to Asri.’

(a’) Hasnah mem-beri Asri kek itu. pn mem-give pn cake that ‘Hasnah gives that cake to Asri.’

(b) Hasnah mem-beli kek itu untuk Asri. pn mem-buy cake that for pn ‘Hasnah bought that cake for Asri.’ (b’) *Hasnah mem-beli Asri kek itu. pn mem-buy pn cake that ‘Hasnah bought that cake for Asri.’

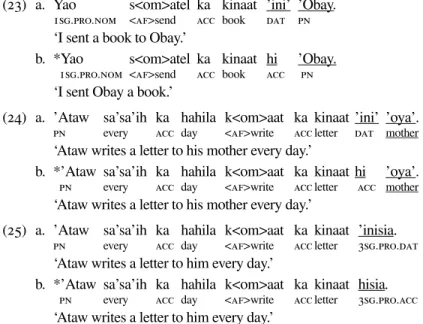

Table 10 might seem to imply that all Recipients allow a Dative-Accusative compe-tition, but that is not true. Consider the following sentences:

(23) a. Yao s<om>atel ka kinaat ’ini’ ’Obay. 1sg.pro.nom <af>send acc book dat pn ‘I sent a book to Obay.’

b. *Yao s<om>atel ka kinaat hi ’Obay. 1sg.pro.nom <af>send acc book acc pn ‘I sent Obay a book.’

(24) a. ’Ataw sa’sa’ih ka hahila k<om>aat ka kinaat ’ini’ ’oya’. pn every acc day <af>write accletter dat mother ‘Ataw writes a letter to his mother every day.’

b. *’Ataw sa’sa’ih ka hahila k<om>aat ka kinaat hi ’oya’. pn every acc day <af>write accletter acc mother ‘Ataw writes a letter to his mother every day.’

(25) a. ’Ataw sa’sa’ih ka hahila k<om>aat ka kinaat ’inisia. pn every acc day <af>write accletter 3sg.pro.dat ‘Ataw writes a letter to him every day.’

b. *’Ataw sa’sa’ih ka hahila k<om>aat ka kinaat hisia. pn every acc day <af>write accletter 3sg.pro.acc ‘Ataw writes a letter to him every day.’

In all these sentences the Recipient is marked by the dative, but it cannot be marked by the accusative. In English, it is possible to say ‘I gave the children a phone-call’ and ‘I made a phone-call to them’ and ‘I write a letter to my mother/her everyday’ and ‘I write my mother/her a letter every day’. Thus it seems somewhat odd to ²nd that the Recipient in Saisiyat allows both accusative and dative in ‘making a phone call’ and ‘giving some-one a pen’, as evidenced in (12) to (15), but not in ‘sending somesome-one a book’, or ‘writing someone a letter’ as seen in (23) to (25). We summarize our ²ndings in table 11.

Table 11 shows that only a subset of Recipients allows dat-acc competition. To see why verbs like s<om>atel ‘to send’ and k<om>aat ka kinaat ‘to write a letter’ do not permit dat-acc competition, let’s look at the following English examples.

(26) a. The old man walked in the streets of the village. b. The old man walked the streets of the village.

TABLE 10. DATIVE NPS AND THEMATIC ROLES

Verbs Dative NPs dat-acc competition

t<om>alek ‘<af>cook’ Bene²ciary no

baehi’ ‘af.wash’ Bene²ciary no

baiw ‘af.buy’ Bene²ciary no

mo-bay ‘af-give’ Recipient yes

pasibaeaeh ‘af.lend’ Recipient yes

The thematic role normally associated with the direct object is Patient and the encod-ing of a non-Patient thematic role as direct object may involve some added sense of affectedness. As shown in (26), the NP the streets of the village is marked by a preposi-tion and encoded as a locative adjunct (i.e., an oblique) in (26a), while it is encoded as a direct object in (26b). The difference in the syntactic coding entails semantic and pragmatic differences. Sentence (26a) tells us where the old man did some walking, but (26b) tells us that the man traversed a lot of streets, perhaps most of the streets. Where a role other than Patient is expressed as direct object, there is often an added sense of affectedness, or a holistic interpretation becomes likely (cf. Blake 2001:133).

Exactly the same interpretation applies to the acc-dat competition in Saisiyat: when the Recipient is in a sphere of potential contact (physically or psychologically) with the Agent, and is perceived to likely be affected by his/her action, it is marked by the accusative case; otherwise, it is marked by the dative.

To Saisiyat speakers, the Recipients coded by the accusative are those who are either in direct physical contact with the Agent, or those who are perceived to be within the sphere of in³uence of the Agent. We illustrate this point in ²gure 1.

TABLE 11. DAT-ACC COMPETITION IN DATIVE NPS

Verbs Dative NPs dat-acc competition

t<om>alek ‘<af>cook’ Bene²ciary No

baehi’ ‘af.wash’ Bene²ciary No

baiw ‘af.buy’ Bene²ciary No

mo-bay ‘af-give’ Recipient Yes

pasibaeaeh ‘af.lend’ Recipient Yes

s<om>aeoe’ ‘<af>offer s.t.as.gift’ Recipient Yes wakik ka laleke: ‘make.a.phone.call’ Recipient Yes s<om>atel ‘<af>send’ Recipient No k<om>aat ka kinaat ‘<af>write a letter’ Recipient No

FIGURE 1. COMPETITION BETWEEN ACCUSATIVE AND DATIVE

Recipient in dative Recipient in accusative

nominative nominative accusative

Giver Giver Theme

accusative accusative

Theme Recipient

dative Recipient

As diagrammed in ²gure 1, in Saisiyat the Agent is invariantly marked by the nom-inative case, the Theme invariantly by the accusative case, and the Recipient allows competition here. When the Recipient is in physical or psychological proximity with, and is thus within the sphere of in³uence of, the Agent, the accusative is preferred. Otherwise, the dative is selected.

6. CONCLUSIONS. In this paper we have shown that the case marking system in

Saisiyat is closely tied to the discourse pragmatics of language use. With regard to the behavior of the nominative case markers, our data show that speakers do not “drop” the case markers indiscriminately. Rather, the presence or the absence of the case markers is semantically and pragmatically constrained. This is especially clear in the behavior of the nominative case markers in SV versus VS constructions.

The coding of the Recipient in ditransitive clauses is shown to be constrained by spa-tial or psychological factors. Recipients marked by the accusative are those within the sphere of in³uence of the Agent, and are thus likely to be in some way affected by the activity of the Agent, while dative-marked Recipients do not have such an implication.

We conclude that case marking in Saisiyat cannot be dissociated from an understand-ing of the nature of the kind of ongounderstand-ing word order change, or from an understandunderstand-ing of the discourse pragmatics of language use.

REFERENCES

Blake, Barry. 2001. Case. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blust, Robert. 1999. Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: Some issues in Austrone-sian comparative linguistics. In Selected Papers from the Eighth International Confer-ence on Austronesian Linguistics, ed. by Elizabeth Zeitoun and Paul Jen-kuei Li, 31– 94. Symposium Series of the Institute of Linguistics (Preparatory Office), No.1. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Chang, Henry Yung-li. 1997. Voice, case and agreement in Seediq and Kavalan. PhD diss., National Tsing Hua University.

Chang, Henry Yung-li, and Amy Pei-jung Lee. 2002. Nominalization in Kavalan. Lan-guage and Linguistics 3(2): 349–68.

Comrie, Bernard. 1975. Causatives and universal grammar. Transactions of the Philo-logical Society 1974:1–32.

———. 1976. The syntax of causative constructions: Cross-language similarities and divergence. In Syntax and semantics 6: The grammar of causative constructions, ed. by Masayoshi Shibatani, 261–312. New York: Academic Press.

Croft, William. 1990. Typology and universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1972. The Dyirbal language of North Queensland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Du Bois, John, Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, Susanna Cumming, and Danae Paolino. 1993. Outline of discourse transcription. In Talking data: Transcription and coding for lan-guage research, ed. by Jane Edwards and Martin Lampert, 45–89. Hillsdale: New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dryer, Matthew. 1986. Primary objects, secondary objects and antidative. Language 62:808–45.

Fillmore, Charles J. 1968. The case for case. In Universals in linguistics theory, ed. by E. Bach, and R. T. Harms, 1–88. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ———. 1989. Grammatical construction theory and the familiar dichotomies. In

Lan-guage processing in social context, ed. by R. Dietrich and C. F. Graumann, 17–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Givón, T. 1983a. Topic continuity in discourse: An introduction. In Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study, ed. by T. Givón, 1–41. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

———. 1983b. Topic continuity and word-order pragmatics in Ute. In Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study, ed. by T. Givón, 141–214. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Goldberg, Adele E. 2002. Surface generalizations: An alternative to alternations. Cognitive Linguistics 13(4): 327–56.

Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. 2002. Voice in western Austronesian: An update. In The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems, ed. by Fay Wouk and Malcolm Ross, 7–16. Canberra: Paci²c Linguistics.

Hopper, Paul J., and Sandy Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse. Language 56:251–99.

Hsieh, Fuhui, and Chihsin Chen. 2006. Nominalization and relativization constructions in Kavalan revisited. Paper presented at the Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (10-ICAL), January 17-20, Palawan, Philippines. Hsieh, Fuhui, and Shuanfan Huang. Saisiyat as a split ergative language. Submitted. Hsin, Aili. 1996. Noun phrase structure and focus marking in Kavalan. Tsing Hua Journal

of Chinese Studies, New Series 26(3): 323–64.

Huang, Shuanfan. 2002a. Tsou is different: A cognitive perspective on language, emotion, and body. Cognitive linguistics 13(2): 167–86.

———. 2002b. The pragmatics of focus in Tsou and Seediq. Language and Linguistics 3(4): 665–94.

———. 2005. Split O in Formosan Languages. Language and Linguistics 6(4): 783– 806.

Huang, Shuanfan, Lily I-wen Su, and Limay Sung. n.d. A functional rerference grammar of Saisiyat. Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University. Ms. Kozinsky, Isaac, and Maria Polinsky. 1993. Causee and patient in causative of transitive. In

Causatives and transitivity, ed. by Bernard Comrie and Maria Polinsky, 177–240. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lee, Amy Pei-jung. 1997. The case-marking and focus systems in Kavalan. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1978a. The case-marking systems of the four less known Formosan languages. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, fasc. 1, ed. by S. A. Wurm and Lois Carrington, 569–615. Series C-61. Canberra: Paci²c Linguistics.

———. 1978b. A comparative vocabulary of Saisiyat dialects. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 49(2): 133–99.

———. 1997. The Formosan tribes and languages in I-Lan. I-Lan: I-Lan County Government. (In Chinese)

———. 2006. Numerals in Formosan languages. Oceanic Linguistics 45:133–52. Meyer, Karen Sundberg. 1992. Word order in Klamath. Pragmatics of word order ³exibility,

ed. by Doris L. Payne, 167–92. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Newman, John. 1998. Recipients and ‘give’ constructions. In The dative, vol.2: Theoret-ical and contrastive studies, ed. by Willy van Langendonck and William van Belle, 1–28. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ogawa, Naoyoshi, and Erin Asai. 1935. Myths and traditions of the Formosan native tribes, 109–28. Taipei: Taihoku Imperial University.

Ross, Malcom. 2002. History and transitivity of western Austronesian voice and voice marking. In The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems, ed. by Fay Wouk and Malcolm Ross, 17–62. Canberra: Paci²c Linguistics.

Ross, Malcom, and Stacy Fang-ching Teng. 2005. Formosan languages and linguistic typology. Language and Linguistics 6(4): 739–81.

Smith, Michael B. 1997. Why quirky case really isn’t quirky or how to treat Dative Sickness in Icelandic. In Polysemy in Cognitive Linguistics, ed. by Hubert Cuyckens and Britta Zawada, 115–60. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Starosta, Stanley. 1974. Causative verbs in Formosan languages. Oceanic Linguistics 13:279–36.

———. 1986. Focus as recentralization. In Focal I: Papers from the Fourth Interna-tional Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, ed. by Paul Geraghty, Lois Car-rington, and S. A. Wurm, 73–95. Series C-93. Canberra: Paci²c Linguistics. Starosta, Stanley, Andrew Pawley, and Lawrence Reid. 1982. The evolution of focus in

Austronesian languages. In Papers from the Third International Conference on Aus-tronesian Linguistics, vol. 2: Tracking the Travelers, ed. by A. Halim, Lois Car-rington, and S. A. Wurm, 145–70. Series C-75. Canberra: Paci²c Linguistics. Wouk, Fay. 1986. Transitivity in Toba Batak and Tagalog. Studies in Language 10:391–424. Yeh, Marie M. 1991. Saisiyat structure. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University. ———. 1995a. Sai-xia-yu-de shi-zhi yu dong-mao chu-tan (An initial investigation on

Saisiyat tense and aspect). In Tai-wan Nan-dao min-zu mu-yu yan-jiu lun-wen-ji (Studies on Formosan Austronesian languages), ed. by Paul Li and Ying-jin Lin, 369–84. Taipei: Ministry of Education. (In Chinese)

———. 1995b. Focus and marking system in Saisiyat. In Papers from the First Interna-tional Symposium on Linguistics in Taiwan, ed. by Feng-fu Tsao and Mei-hui Tsai, 29–58. Taipei: The Crane Publishing Co.

———. 2000. A reference grammar of Saisiyat. Formosan Languages Series 2. Taipei: Yuan-liu. (In Chinese)

———. 2001. The uses and functions of ka in Formosan languages. Proceedings of the Symposium on Selected NSC Projects in General Linguistics 1998–2000, 17–36. June 9 –10, Taipei: National Taiwan University.

———. 2003. A syntactic and semantic study of Saisiyat verbs. PhD diss., National Taiwan Normal University.

Zeitoun, Elizabeth, and Lillian M. Huang. 2000. Concerning ka-, an overlooked marker of verbal derivation in Formosan languages. Oceanic Linguistics 39:391–414.