Original Article

Tourette Syndrome and Risk of Depression:

A Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan

I-Ching Chou, MD,*† Hung-Chih Lin, MD,*‡ Che-Chen Lin, MSc,§ Fung-Chang Sung, PhD,§\

Chia-Hung Kao, MD‡¶

ABSTRACT: Objective: The temporal relationship between Tourette syndrome (TS) and depression is unclear.

This cohort study evaluates the relationship between TS and depression in Taiwan. Methods: Claims data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance database were used to conduct retrospective cohort analyses. The study cohort contained 1337 TS patients who were frequency matched by sex, age, urbanization of residence area, parental occupation, and baseline year with 10 individuals without TS. Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis was conducted to estimate the effects of TS on depression risk. Results: In patients with TS, the risk of developing depression was significantly higher than in patients without TS (p value for log-rank test< .0001). After adjusting for potential confounding, the TS cohort was 4.85 times more likely to develop depression than the control cohort (HR5 4.85, 95% CI 5 3.46–6.79). Conclusions: In Taiwan, patients with TS have a higher risk of developing depression. The findings of this study are compatible with studies from other countries. This study could provide an evidence to inform the prognosis for a child with TS. The mechanism between TS and increased depression risk requires further investigation.

(J Dev Behav Pediatr 34:181–185, 2013) Index Terms: Tourette syndrome, depression, cohort study.

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a developmental neuropsy- chiatric disorder characterized by multiple, brief, stereo- typical nonrhythmic movements and phonations (called tics) lasting at least 1 year.1The onset of tic symptoms in TS typically occurs during early childhood, and the disor- der affects 0.15% to 3.8% of Western2 and 0.56% of Taiwanese3 school-age children. Children with TS often function poorly in numerous psychosocial domains4and have high rates of psychiatric comorbidity.5An epidemi- ological study in an elementary school with 2000 Taiwa- nese children aged from 6 to 12 years demonstrated that the prevalence TS was approximately 0.56%. The ratio of males to females with TS was 9:2. Comorbid rates were 36% for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 27% for self-injurious behaviors, and 18% for obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD) and learning difficulties.3

A recent study showed that children with TS experi- ence more frequently with comorbid depression and

anxiety disorders in adolescence and early adulthood than the comparison group. The severity of tics in TS children usually declines during adolescence, but comorbidities may persist and often cause more functional impairment.6 It is unclear, however, whether psychosocial function- ing, such as tics, improves by this age. Previous longitu- dinal studies have found that patients with TS functioned reasonably well in late adolescence or early adulthood, but these studies were limited by the absence of a control group.7–9 By contrast, controlled cross-sectional studies have reported that adults with TS had a poorer quality of life10and more psychopathology.11A critical limitation to these studies was that the participants were not neces- sarily identified as having TS in childhood and attended specialty clinics as adults. Consequently, the poor out- comes described may apply mainly to the minority of TS patients who continue to have prominent tics and pursue treatment during adulthood.

This study aims to determine whether individuals with TS are more likely to be diagnosed with depression than those without TS. A representative data set was used to perform a population-based retrospective cohort study to determine the risk of depression for TS patients.

The database was obtained from the National Health Insurance (NHI) system in Taiwan.

METHODS Data Source

The Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program has provided universal health insurance since 1996 and covered almost 99% of the Taiwanese population in

From the *Department of Pediatrics, China Medical University Hospital, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan;†Graduate Institute of Integrated Medi- cine, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan;

‡Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine Science and School of Medicine, Col- lege of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan;§Management Office for Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan;

\Departments of Public Health, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan;

¶Department of Nuclear Medicine and PET Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

Received October 2012; accepted December 2012.

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Address for reprints: Chia-Hung Kao, MD, Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine Science and School of Medicine, College of Medicine, China Medical University, No. 2, Yuh-Der Road, Taichung 404, Taiwan; e-mail: d10040@mail.cmuh.org.tw CopyrightÓ 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

1998. The NHI Research Database (NHIRD) includes annual reimbursement claims data from the Taiwan NHI program. The National Health Research Institute (NHRI) established and manages the database and encrypts all identification information to protect patient privacy before the data are released for research.

This research uses the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID), a subset of the NHIRD. The LHID includes historical claims data for 1 million people ran- domly sampled from the whole insured population from 1996 to 2000. The NHRI created an anonymous identifi- cation number to link each claimant’s demographic information (including sex, birth date, occupation, and residential area) with their registry of medical services. This research used the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to define disease diagnoses from outpatient and inpatient data.

All the included study subjects with TS diagnoses and outcome measure of depression diagnoses were already confirmed by accurate ICD-9 coding according to the study subject’s medical records in the NHIRD. In addi- tion, TS and depression diagnoses in NHIRD were already evaluated based on validated definitions.12 Study Population

This research is a population-based retrospective cohort study. The Tourette syndrome (TS) cohort included patients younger than 18 years with TS (ICD-9- CM 307.2) diagnosed between 2000 and 2010. The base- line was set as the date of TS diagnosis. A comparative cohort was randomly selected from rest of children in the same years frequency-matched individuals without TS by sex, age (in intervals of 3 years), urbanization of resi- dence area, parental occupation, and baseline year. Newly occurring depression (ICD-9-CM 296.2-296.3, 300.4, and 311) was noted in the 2 cohorts. For each child with TS, 10 comparison children were selected to increase the statisti- cal power and avoid small number of depression in the stratified analysis. Children with depression diagnosed at baseline were excluded from the study cohorts. Follow-up was continued until developing depression, insurance was withdrawn, or December 31, 2010.

Parental occupation was classified into 3 groups (white collar, blue collar, and other). Residential area was grouped into 4 urbanization levels based on an index that included population density (people/km2), population ratio of edu- cational level, population ratio of older adults, population ratio of agricultural workers, and the number of physicians per 100,000 people.13 Level 1 reflects the highest degree of urbanization and Level 4 reflects the lowest. We also collected the children comorbidity history before the end of follow-up. The comorbidity included attention-deficit- hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, ICD-9-CM 314) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD, ICD-9-CM 300.3).

Statistical Analysis

The means and standard deviations (SDs) for continu- ous variables and counts and percentages for categorical

variables were used to demonstrate the baseline distribu- tion of the Tourette syndrome (TS) and comparison cohorts. The t test andx2tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, to assess the dif- ference between the cohorts. The overall depression incidence and demographic-specific depression incidence rate were calculated by number of patients per 10,000 person-years. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to depict cumulative depression incidence for the TS and comparison cohorts. A log-rank test was used to test the difference between the curves. Cox’s proportional haz- ards regression model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and confidence interval (CI) for the TS cohort compared with the comparison cohort, after controlling for potential confounding factors. Because the pro- portions of comorbidity in study population were small, the comorbidities were excluded from the adjusted model. Demographic-specific HRs were estimated to compare patients with TS with patients without TS by demographic characteristics. We grouped Levels 1 and 2 of urbanization into the urban group and grouped Levels 3 and 41 of urbanization into the rural group for estimating

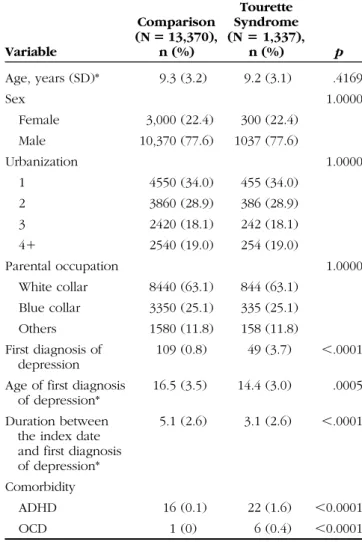

Table 1. Comparisons in Demographic Status and Comorbidity Between Comparison Cohort and Tourette Syndrome Cohort

Variable

Comparison (N 5 13,370),

n (%)

Tourette Syndrome (N 5 1,337),

n (%) p

Age, years (SD)* 9.3 (3.2) 9.2 (3.1) .4169

Sex 1.0000

Female 3,000 (22.4) 300 (22.4) Male 10,370 (77.6) 1037 (77.6)

Urbanization 1.0000

1 4550 (34.0) 455 (34.0)

2 3860 (28.9) 386 (28.9)

3 2420 (18.1) 242 (18.1)

41 2540 (19.0) 254 (19.0)

Parental occupation 1.0000

White collar 8440 (63.1) 844 (63.1) Blue collar 3350 (25.1) 335 (25.1)

Others 1580 (11.8) 158 (11.8)

First diagnosis of depression

109 (0.8) 49 (3.7) ,.0001 Age of first diagnosis

of depression*

16.5 (3.5) 14.4 (3.0) .0005 Duration between

the index date and first diagnosis of depression*

5.1 (2.6) 3.1 (2.6) ,.0001

Comorbidity

ADHD 16 (0.1) 22 (1.6) ,0.0001

OCD 1 (0) 6 (0.4) ,0.0001

*t test. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

demographic-specific HRs. Further data analysis was conducted to observe how the risk of depression changed during the follow-up period.

Data management and analysis were performed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and cumulative incidence curves were drawn using R software (R Foun- dation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The sig- nificance level was set at p, .05 for two-side testing.

RESULTS

The study includes a cohort of 1,337 patients with Tourette syndrome (TS) and a comparative cohort of 13,370 patients (Table 1). The mean age of the 2 cohorts was 9.3 years, and there were 3 times more boys than girls; 34% of the study population lived in highly urban- ized areas and 63% of parents were engaged in white- collar occupations; 3.7% of patients developed depression in the TS cohort compared with 0.8% in the comparative cohort. The mean age of depression diagnosis in the TS

cohort was nearly 2 years less than in the comparison cohort (14.4 vs 16.5 years, p,. 0001).

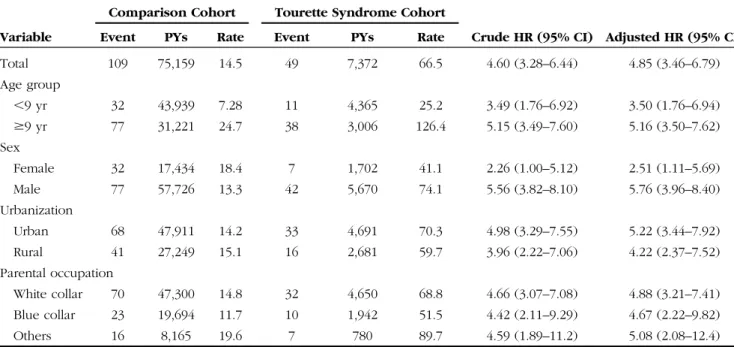

The depression incidence in the TS cohort was 66.47 per 10,000 person-years (Table 2), which is 4.6 times higher than the comparison cohort (14.50 per 10,000 person-years). Figure 1 shows the cumulative TS incidence curve for the 2 cohorts and indicates that the TS incidence curve is significantly higher than the comparison cohort (p value for the log-rank test, .0001). After adjusting for potential confounding, the TS cohort is more than 4.85 times more likely to develop depression than the com- parison cohort (hazards ratio [HR] 5 4.85, 95% confi- dence interval [CI]5 3.46–6.79).

Table 2 shows demographic-specific depression rates and the HRs for the 2 cohorts. The hazards of being diagnosed with depression were greater for boys than for girls (HR5 5.76 vs 2.51) and greater for older children ($9 years) than for younger children (,9 years) (HR 5 5.16 vs 3.5). The depression rate in the TS cohort was higher for children living in urban areas than in rural areas and the lowest for children with blue-collar patents.

Further data analysis measured depression being diagnosed for both cohorts in the follow-up period (Table 3). The events of depression were on the wane over time in the TS cohort, declining from 101.2 per 10,000 person-years in Year 1 to near a half in Year 5 and longer.

On the other hand, the depression rate increased from 5.39 per 10,000 person-years to nearly five-fold higher, corre- spondingly, in the comparison children. The corresponding HR for the TS cohort dwindles greatly to nearly nine-fold.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort study, Tourette syn- drome (TS) was significantly associated with an increased Table 2. Incident Depression and Multivariate Cox’s Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis Measured HR for the Study Cohort

Variable

Comparison Cohort Tourette Syndrome Cohort

Crude HR (95% CI) Adjusted HR (95% CI)

Event PYs Rate Event PYs Rate

Total 109 75,159 14.5 49 7,372 66.5 4.60 (3.28–6.44) 4.85 (3.46–6.79)

Age group

,9 yr 32 43,939 7.28 11 4,365 25.2 3.49 (1.76–6.92) 3.50 (1.76–6.94)

$9 yr 77 31,221 24.7 38 3,006 126.4 5.15 (3.49–7.60) 5.16 (3.50–7.62)

Sex

Female 32 17,434 18.4 7 1,702 41.1 2.26 (1.00–5.12) 2.51 (1.11–5.69)

Male 77 57,726 13.3 42 5,670 74.1 5.56 (3.82–8.10) 5.76 (3.96–8.40)

Urbanization

Urban 68 47,911 14.2 33 4,691 70.3 4.98 (3.29–7.55) 5.22 (3.44–7.92)

Rural 41 27,249 15.1 16 2,681 59.7 3.96 (2.22–7.06) 4.22 (2.37–7.52)

Parental occupation

White collar 70 47,300 14.8 32 4,650 68.8 4.66 (3.07–7.08) 4.88 (3.21–7.41) Blue collar 23 19,694 11.7 10 1,942 51.5 4.42 (2.11–9.29) 4.67 (2.22–9.82)

Others 16 8,165 19.6 7 780 89.7 4.59 (1.89–11.2) 5.08 (2.08–12.4)

Model adjusted for age, sex, urbanization, and parental occupation. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PYs, person-years; rate, per 10,000 person-years.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier model depicted cumulative incidence of depression in the comparison and Tourette Syndrome (TS) cohorts.

rate of depression measured in the TS group than in the comparison group, despite where children lived or what parental occupations were. The evidence shows that depression rate in the TS cohort was 4.6 times higher than that in the comparison cohort. The mean age of depression diagnosis in the TS cohort was less than that in the comparison cohort. This is consistent with pre- vious studies stating that children with TS experience comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders during ado- lescence and early adulthood more frequently than those without TS.6,8 A Canadian study found approximately 40% of children with TS had experienced depression or a nonobsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) anxiety dis- order.6Besides, we found that males with TS were more likely to be diagnosed with depression later than females.

Although the cause of depression is multifactorial, and adult female is more vulnerable to depression, males with TS may be relatively at an elevated risk of depression. The important finding is that most depression cases in the TS cohort are identified in earlier follow-up period. It is possible that depression is a comorbidity being found because of the diagnosis and care of TS.

The reason for this association remains uncertain.

Comings and Comings14have reported that depression is an integral part of TS and shares a common genetic basis, whereas others argue that the disorders are genetically unrelated and that TS is a risk factor for depression because of the emotional consequences of having a chronic illness.15The effects of tic severity, attention- deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), OCD, and psy- chosocial stress may account for the association of TS with depression.16,17 Gorman et al recently found that a major depressive disorder was the only comorbid dis- order not associated with a lifetime diagnosis of ADHD or OCD, any tic, or ADHD or OCD severity. Unlike learning and conduct disorders, the between-group dif- ferences for major depressive disorder rates remain sig- nificant after controlling for ADHD diagnosis or severity.

Therefore, these disorders could be inherently linked, independent of the emotional effects of chronic illness.

The study was subject to certain limitations. First, the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) does not include detailed information on patients, such as physical activity, socioeconomic status, and family history of systemic or neuropsychiatric diseases. These are all risk factors that could be associated with depression. Second, evidence from a cohort study is usually less reliable than

that from randomized trials, because a cohort study design is subject to many biases related to confound adjustments.

Despite the meticulous study design with adequate con- trol of confounding factors, bias could still remain because of possible unmeasured or unknown confounders. It is also possible that the children in the TS cohort might be more closely monitored for the development of psychi- atric comorbidity and a higher rate of depression was identified. Third, we were unable to probe for associa- tions of depression with specific medications and psy- chotherapy because of the complicacies of data requiring a larger sample size.

The data show that older adolescents with TS identi- fied during childhood continue to experience consider- able psychosocial impairment and they have high lifetime rates of depressive disorders. Thus, although tics are likely to improve by the age of 18 years,3,4outcomes for psychosocial functioning and comorbid conditions must be monitored. This study could provide an evidence to inform the prognosis for a child with TS. The mecha- nism of TS and the subsequent increased depression risk requires further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has used a follow-up analysis to prove that children with Tourette syndrome are more than four-fold likely to be diagnosed with depression than general children. The hazard of depression wanes over time.

Whether or not depression is associated, medication for children deserves further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the study project (DMR-101-36) in China Medical University Hospital; Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center and for Excellence (DOH102-TD-B-111-004), Tai- wan Department of Health Cancer Research Center for Excellence (DOH102-TD-C-111-005); and International Research-Intensive Centers of Excellence in Taiwan (I-RiCE) (NSC101-2911-I-002-303).

REFERENCES

1. Leckman JF, Peterson BS, Pauls DL, Cohen DJ. Tic disorders.

Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:839–861.

2. Robertson MM. Diagnosing Tourette syndrome: is it a common disorder? J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:3–6.

3. Wang HS, Kuo MF. Tourette’s syndrome in Taiwan: an

epidemiological study of tic disorders in an elementary school at Taipei County. Brain Dev. 2003;25(suppl 1):S29–S31.

4. Carter AS, O’Donnell DA, Schultz RT, Scahill L, Leckman JF, Pauls DL.

Social and emotional adjustment in children affected with Gilles de la Table 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Model Estimated Depression Incidence in Study Cohorts by Follow-Up Year and Hazard Ratio of Depression for Study Cohorts

Follow-Up Years

Comparison Cohort Tourette Syndrome Cohort

HR (95% CI) Adjusted HR (95% CI)

Event PYs Rate Event PYs Rate

#1 7 12,975 5.39 13 1,285 101.2 18.7 (7.46–46.9) 20.0 (7.97–50.1)

2–4 29 32,951 8.80 21 3,257 64.5 7.33 (4.18–12.8) 7.75 (4.42–13.6)

.4 73 29,233 25.0 15 2,829 53.0 2.12 (1.22–3.70) 2.22 (1.27–3.86)

Model adjusted for age, sex, urbanization, and parental occupation. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PYs: person-years; rate: per 10,000 person-years.

Tourette’s syndrome: associations with ADHD and family functioning.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2000;41:215–223.

5. Kurlan R, Como PG, Miller B, et al. The behavioral spectrum of tic disorders: a community-based study. Neurology. 2002;59:

414–420.

6. Gorman DA, Thompson N, Plessen KJ, Robertson MM, Leckman JF, Peterson BS. Psychosocial outcome and psychiatric comorbidity in older adolescents with Tourette syndrome: controlled study.

Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:36–44.

7. Leckman JF, Bloch MH, King RA, Scahill L. Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders. Adv Neurol. 2006;

99:1–16.

8. Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, et al. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:

65–69.

9. Burd L, Kerbeshian PJ, Barth A, Klug MG, Avery PK, Benz B.

Long-term follow-up of an epidemiologically defined cohort of patients with Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:

431–437.

10. Elstner K, Selai CE, Trimble MR, Robertson MM. Quality of Life (QOL) of patients with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:52–59.

11. Robertson MM, Banerjee S, Hiley PJ, Tannock C. Personality disorder and psychopathology in Tourette’s syndrome: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:283–286.

12. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the national health insurance research database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:

236–242.

13. Liu CY, Hung YT, Chuang YL, et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manage. 2006;4:1–22.

14. Comings DE, Comings BG. A controlled family history study of Tourette’s syndrome, III: affective and other disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:288–291.

15. Pauls DL, Leckman JF, Cohen DJ. Evidence against a genetic relationship between Tourette’s syndrome and anxiety, depression, panic and phobic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:215–221.

16. Lin H, Katsovich L, Ghebremichael M, et al. Psychosocial stress predicts future symptom severities in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:157–166.

17. Robertson MM. Mood disorders and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome: an update on prevalence, etiology, comorbidity, clinical associations, and implications. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:

349–358.