College of Management

I-Shou University

Master Thesis

Cultural Factors That Hinder Cooperation in

the Workplace

Advisor: Peter Gilks

Graduate Student: Anujin Molomjamts

January 2015

Acknowledgements

No one creates or does anything without other’s direct or indirect influence. The one who played an enormous role in completing this work was my supervisor, Professor Peter Gilks, whose guidance allowed me to reach this point. Throughout my journey of writing this master’s dissertation, I had my ups and downs with regard to feasibility and difficulties of this work. His timely patience and encouragement were crucial during the challenges that we had. Also, I am sincerely grateful for his contribution to my academic growth by not only being my supervisor but also letting me attend his classes as an auditing student for two semesters. I wish him good luck and wish his mentorship work to involve more and more students from all over the world, thereby becoming rich of his students like the definition of ‘moderate wealth’ in three assets of the universe in our saying.

Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the committee members of this dissertation—Professor Anestis Fotiadis and Professor Fu-Sheng Tsai—for witnessing my one year work, generously sharing their constructive comments and advice and helping the dissertation to be one step ahead.

My deepest gratitude goes to my family, for their love and faith in me created the current individual. Moreover, I would not have been able to finish this master’s program unless they had supported me. They aided me in every way except for academic assistance, and their blessing has been with me all the way my graduation.

Finally, as a student studying abroad, I want to close acknowledgements by expressing my impression of the country where I studied and lived for almost two years. My appreciation of Taiwanese friends and people is great. Their hospitality resembles that of nomadic Mongolians, so during my stay although having hard times about the food, I felt homelike here in the gloomy yet friendly island.

Abstract

The relationship between Mongolia and China has seen an unprecedented growth in both public and private sectors in recent years. While previous research has documented many large cultural differences between the two countries, the impact of these differences in the Mongolian-Chinese intercultural workplace and the relative importance of these differences have not been investigated until now. This study therefore attempts to address this gap in Mongolian/Chinese cross-cultural studies. This study focuses on Mongolian workers’ perspectives on the value differences between themselves and their Chinese employers with regard to three of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, namely, power distance (PD), long-term orientation (LTO) and masculinity (MAS), which have been investigated using quantitative techniques. Statistical analysis of the survey based on a sample of 47 Mongolian employees suggests that Mongolian employees in Chinese owned business do not see the cultural differences pertaining to these three dimensions as contributing equally to dissatisfaction in the workplace. In particular, differences in the area of PD and MAS appear to contribute more to worker dissatisfaction than LTO does. Based on these findings, certain suggestions are offered for Chinese managers. A second research question aimed to know the extent to which certain distinct characteristics of Chinese culture relating to the three dimensions actually occur in the workplace. It was found that from the perspective of those Mongolian employees surveyed, a lack of consideration for employees’ leisure time and hierarchical organizational structures were the most common characteristics.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ... iv

Abstract ... v

List of Tables ... viii

Abbreviation of Key terms ... ix

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 General Background ... 1

1.2 Choosing a Country ... 3

1.3 Different values of the two nations ... 5

1.4 Research Background ... 7

1.5 Research Significance ... 8

1.6 Research Objectives ... 15

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 16

2.1 Cultural value study ... 16

2.2 Types of Cultural Value Studies ... 17

2.3 The Utility of Hofstede’s Cultural Values in the Workplace ... 19

2.4 Mongolian Culture according to Hofstede’s dimensions ... 22

2.5 Summary ... 32

Chapter 3 METHODOLOGY ... 33

3.1 Selection of Participants ... 33

3.2 Method ... 34

3.3 Data Collection ... 35

Chapter 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 37

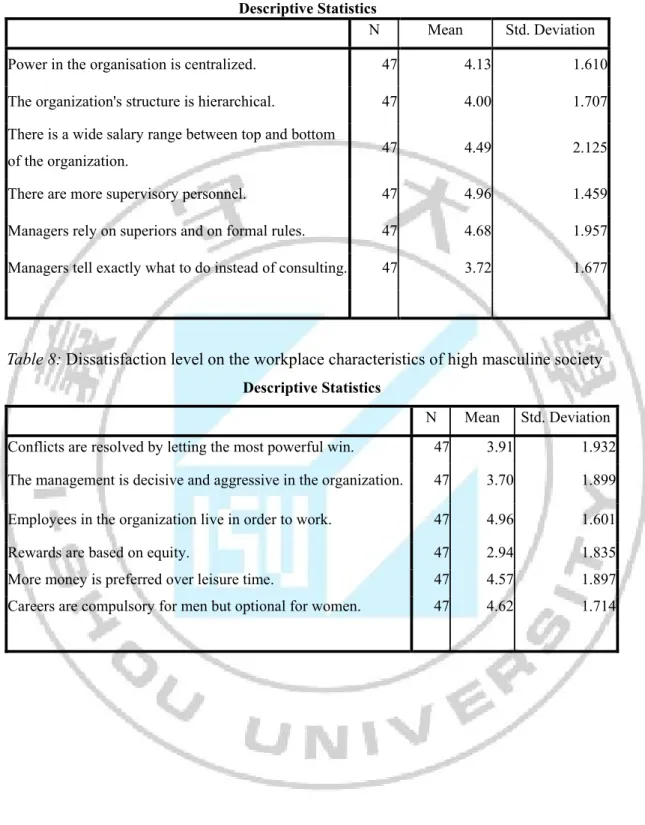

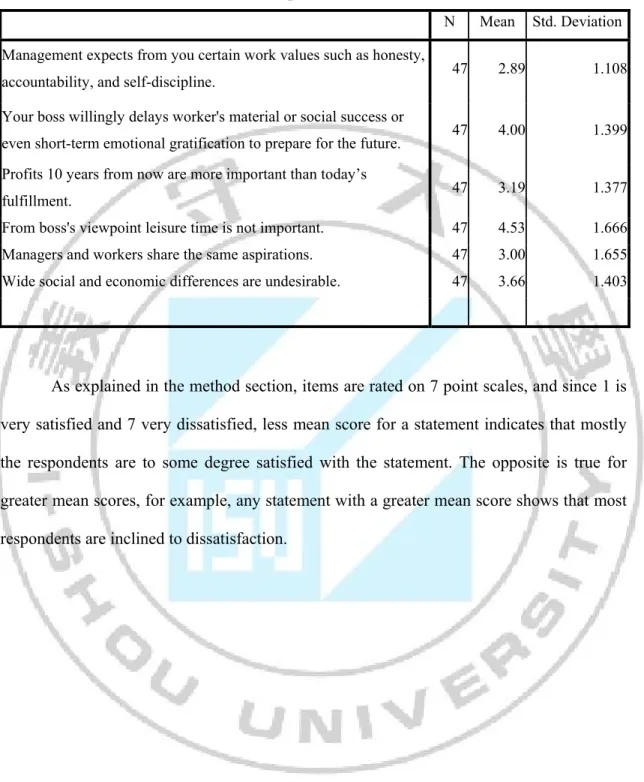

4.1 Descriptive Statistics ... 37

4.2 Cronbach’s Alpha for the Instrumentation Testing ... 40

4.3 Testing the Research Questions ... 40

4.4 Summary ... 45

Chapter 5 CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ... 46

5.1 Research Summary ... 46 5.2 Managerial Implications ... 47 5.3 Research Limitations ... 48 5.4 Future Research ... 49 5.5 Conclusions ... 50 References ... 52

Appendix A Government reports ... 56

List of Tables

Table 1: Nationality of Foreign residents in MongoliaTable 2: Residence permits issued as of 2012 in Mongolia by status Table 3: Foreign companies in Mongolia by sectors

Table 4: FDI in Mongolia by countries

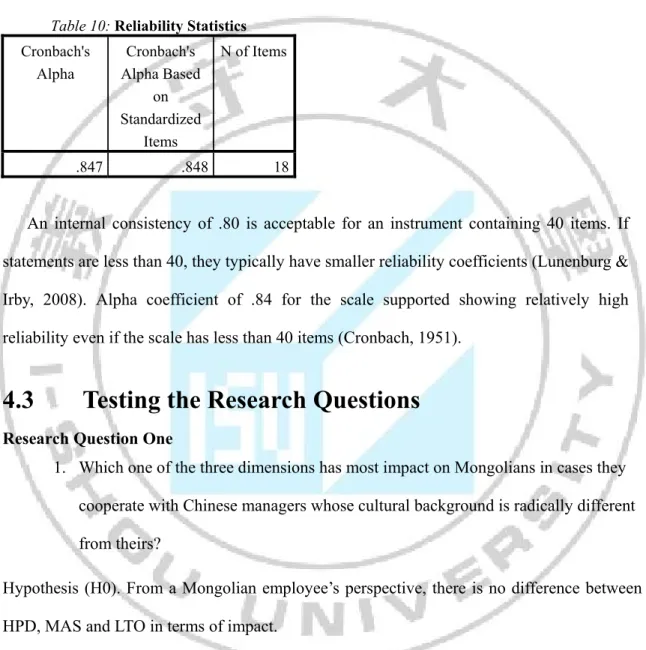

Table 5: Mongolian Cultural dimensions according to two different studies Table 6: Comparison of Mongolia and China's PD, MAS and LTO indices Table 7: Dissatisfaction level on the workplace of high power distance society Table 8: Dissatisfaction level on the workplace of high masculine society Table 9: Dissatisfaction level on the workplace of long term oriented society Table 10: Reliability Statistics

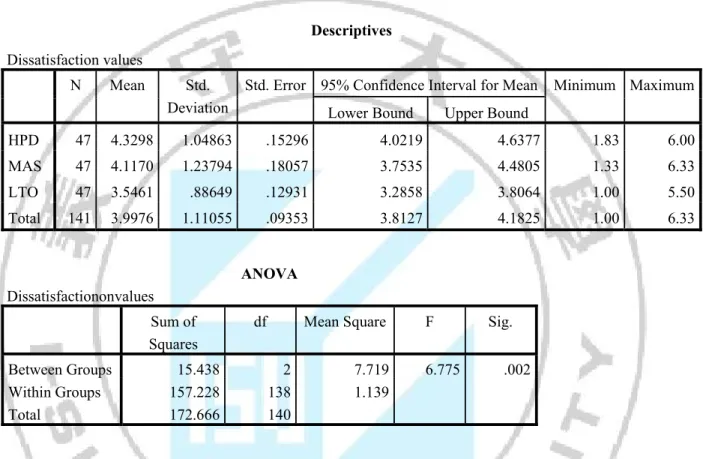

Table 11: Means and ANOVA Summary Table a sample of 47 Mongolian employees Table 12: Comparisons between HPD, MAS and LTO among the sample

Table.13: frequencies of HPD descriptions Table.14: frequencies of MAS descriptions Table.15: frequencies of LTO descriptions

Abbreviation of Key terms

PD- high power distance

MAS-masculinity

LTO-long term orientation

IND-individualism

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 General Background

The world has globalized at a rapid pace in economic terms over the last two decades, which has prompted companies go beyond national boundaries in order to expand their business and conquer new, lucrative markets. With regard to economic globalization, issues of cultural differences appear and therefore received much attention from researchers such as Hall & Hall (1969) Hofstede (1980) House et al. (1999) Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner (1998). Their studies suggest existing differences in different nationalities, which could be taken into account by outsiders. Nowadays, it is common for different nationalities to work together in a multinational corporation or even any private company. In this respect, managing employees from different cultures becomes a challenging task for managers, who must try to maintain a company's productiveness and profitability while avoiding mismanagement. Cultural differences for intercultural management have been studied by some researchers (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1998), whose findings suggest that unless cultural differences are carefully considered by management, conflicts and misunderstandings become prevalent in companies where more than one nationalities work.

One case that reminds us the significance of cultural issue is The Anglo-French merger of Metal Box Company and Carnaud in 1989. Though the both companies were successful in respective regions, the trend was downward after the merger took place. Many experts in the industry ascribed the failure to ‘clashes of cultures’ at the top level of the company leading to indecision about organization and strategy. As one analyst explained their failure, the fact that management styles are different throughout Europe while the executives overlooked cultural difference. Even if differences exist in companies in the same country, those small differences cannot be paralleled with the cross-country differences (Johnson &

Scholes, 1993).

Another case concerns trying to embark upon a new common goal without recognizing the motivational and inspirational factors of culturally different employees. An American computer company developed new operating principles as a common corporate vision for its subsidiaries all over the world. One of the listed principles was ‘Have Fun’. Yet Dutch employees reacted as if they should mind their own business. (Hoecklin, 1996).

Taking a systematic approach to cross-cultural studies, Hofstede (1980), Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner (1998) and GLOBE research team (House et al., 2004) have respectively attempted to identify common values, behaviors, and institutions within countries. Perhaps the most influential research has been that of Hofstede (1980), who argues that people in the same country hold common values and mindsets which are developed in the family in early childhood and reinforced in schools and organizations. These value systems contain components of national culture and are distinguishable across nations. His empirical findings and theoretical analysis contribute to cross-cultural value analysis and to the cross-cultural study of workplace motivation and organizational dynamics. To date, Hofstede’s nationalities’ framework has been extended by other researchers, for example Erumban & De Jong (2006), Tang & Koveos (2008), Yoo, Donthu, & Lenartowicz (2011), and used by many others including laypeople and scholars. As people who are interested in cross-cultural studies already know, Hofstede’s framework supplies measurable differences within nationalities by defining nationalities’ value differences based upon five dimensions: power distance, masculinity, long or short-term orientation, individualism and uncertainty avoidance (power distance, masculinity and long-term orientation are hereafter referred to as PD, MAS and LTO).

Hofstede’s study delineates a particular country/culture through the five dimensions and suggests what factors should be taken into consideration with regard to cultural differences when one actively engages with people of another nationality. But if two countries have more

than one difference it is not known which one of those differences is the most important for the people of a given country. In other words, which dimension has a dominant influence over the other dimensions? For example if a person from a society characterized by low power distance and low masculine society moves to a society characterized by high power distance and high masculine, would high power distance differences exert more influence than masculine differences on people? Or do masculine differences have a greater effect? The idea proposed here is to estimate the degree of relative importance of Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions.

The most well-studied of Hofstede’s cultural value is Individualism index which tries to define a nation’s degree of individualism, i.e. if it is mostly collectivist or individualist. For example, there are 120 empirical studies at individual, group/organizational and country level in the fields of business and psychology excluding studies in marketing and financial fields (Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, 2006). After executing a comprehensive review on 180 articles and chapters that utilized Hofstede’s cultural values framework for empirical research, Kirkman et al. (2006) recommend that researchers actively include the other cultural values—PD, MAS, LTO and UA—into their research to know more about them. In accordance with their advice, this research attempts to assess the relative importance of those of Hofstede’s three cultural values—PD, MAS, and LTO—in the Mongolian workplace given the differences observed in those dimensions. In doing so, the researcher would like to enhance the cooperation between Mongolian workers and Chinese employers. Also, since there is no single study about measuring those dimensions against one another, it is a pilot study for further research. The main goal of the research is to know which of those cultural values is deemed to be the most important for Mongolian employees.

To find out the relative importance of the five cultural dimensions, this study chose Mongolia, which is culturally distinct from its long-term neighbor, China. Since the first introduction of the cultural dimensions among western scholars, China has been the interest of research for such a long time that now it is a well known nation due to its huge influence on word economy as well as its rich history and ancient culture. Compared to its southern neighbor, Mongolia has been such a forgotten place that few studies have attempted to delineate Mongolian culture so far despite the fact that it has a distinctive culture with long history. However, what makes Mongolian context so necessary as well as interesting to be studied is the recent political deals that intensively promote cooperation between Chinese and Mongolians. At the same time, values held by two nations are quite different, and there is also considerable sinophobia in Mongolia.

The first reason to select Mongolia was as a Mongolian student studying abroad, I have witnessed a number of distinct attitudes between Mongolian students and those of mainland China, Taiwan and Vietnam. For instance, when communicating with teachers, school staff as well as administrators, most Mongolian students show neither fear nor nervousness and usually regard those people as their supporter or as a sister or brother in case of their own country. But in contrast with their Mongolian counterparts, students of south East Asian countries especially students from Mainland China, mostly seem rather nervous and anxious in the same situation and see administrators as unapproachable superiors. The probable underlying reason for such an attitude is Chinese cultural characteristic that is known having high power distance society (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

Second, there has been historically rooted dislike between the two nations though the tense bilateral relationship between Mongolia and China is likely to soften to some degree in the coming years due to the fact that both countries’ presidents signed on 26 agreements during Chinese president Xi Jinping’s first visit to Mongolia on 21st of August 2014 to extend partnership in the private and public sector (Jiao & Shengnan, 2014). As a result, the

intercultural interaction between ordinary Mongolians and China will probably become more active. Notwithstanding this and previous attempts to bring the people of the two country together, there has been rising anti-Chinese movements in Mongolia. So the importance of cultural awareness may come in handy for not only smooth collaboration but also further mutual success of the two countries.

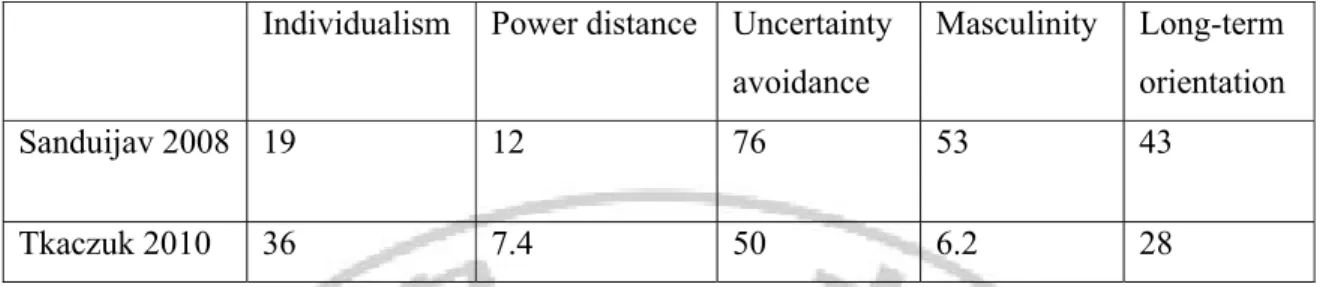

Third, the literature on Mongolian cultural dimension reveals that Mongolians received radically different scores from China in two of the five dimensions: long-term orientation and power distance (Sanduijav, 2008; Tkaczuk, Badarch, & Tureckov, 2010). In addition to the two remarkable distinctions, masculinity score in one study is rather low 6.2 that can be also seen as another huge difference, but one study reaches a high score of 53 in masculinity (Sanduijav, 2008). These vast cultural differences could cause troubles for people who will endeavor to cooperate with each other.

In 2008, Sanduijav (2008) assessed Mongolian cultural dimensions in the form of replicating Hofstede’s IBM study in her doctorial thesis. Her study’s result revealed remarkably low scores of 12 in Power Distance and 48 in Long-term orientation. Likewise, in 2010, three students of Warsaw University of Life Science who are Polish, Mongolian and Russian, replicated Hofstede’s seminal work on their respective countries in which Mongolians scored 7.4 in Power distance and 28 in Long-term orientation (Tkaczuk et al., 2010). The results of these two replications are relatively similar in spite of their different sample sizes. However, the scores of masculinity index differ noticeably from each other. It might be due to the sample of the 2008 study because respondents vary regarding occupation and age, unlike the 2010 study.

1.3 Different values of the two nations

The study of value is important for Mongolians. They are considered as one of the last nomadic cultures. Whilst Chinese are known as successful businessmen compared to other

cultural groups when working or doing business abroad (Gannon, 2004), historical accounts reported that Mongolians were herders with no aptitude for commerce (Huc, 1900). For instance, the Mongolian terms ‘panzchin’ (originating from fanzi in Chinese) in Mongolian and ‘damiin naimaachin’ are derogatory terms for a merchant or trader due to the fact that Mongolians got swindled and betrayed by Chinese merchants and traders during 18th century and 19th century. The meaning of these two terms gives a clue to how Mongolians regarded commerce disapprovingly. This kind of attitudes shows the sign of a feminine society i.e. low masculine score as defined by Hofstede and Hofstede (2005).

Bawden (1968) first chronicled in English the history of Mongolia from the colonial period to modern era. In his book, he pointed out that Chinese managers (danjaad in Mongolian) of shops in Mongolia would often become superficially ‘Mongolised’ by acquiring Mongolian name, even neglecting to perform the Chinese funeral rituals and marrying a Mongolian women, even if the marriage was forbidden at that time. In spite of their Mongolisation, Chinese merchants operated a very harsh credit policy on Mongolians in during their settlement in Mongolia. Conversely, from the Mongolian standpoint, changing one’s Mongolian name to a Chinese name, marrying with a Chinese, opposing traditions have been frowned upon and regarded as disgrace among Mongolians. These two different attitudes of people show how Mongolians are short-term oriented whilst Chinese are long-term oriented.

It was mentioned in earlier historical accounts that during Yuan dynasty, the ruling Mongolians were “insensitive to Chinese cultural values, distrustful of Chinese influences and inept heads of Chinese government” (Mote, 1961, as cited in Rossabi, 1988, p. 2). In contrast, during Qing dynasty, both Mongolia and China were under the control of Manchus, who were eventually sinicized. Of this period, Haslund (1993) writes:

Although the ordinances of the Chinese Colonial Ministry of 1789 and 1815 constituted the laws of the nomads, the principles of justice introduced by the Chinese

never struck deep roots among the people of the tents in the wilderness. With Buddhistic submissiveness the nomads accommodated themselves to the Chinese judicial system, yet they continued to judge the worth of their fellows according to the ancient moral conceptions of their forefathers (p. 268).

This kind of Mongolian characters fits with characteristics of short-term oriented society as specified by Hofstede & Hofstede (2005).

1.4 Research Background

The Mongolian economy is prospering by virtue of the mining industry growth in recent years, and this has resulted in an increasing interest by foreign companies to commence operations in Mongolia. Expatriate workers are also seeking job opportunities in the country. This influx of employers as well as employees presents a new challenge with respect to intercultural communication in cross-cultural management for many companies and also for the locals. Most foreign companies tend to begin operation in mining sector since more than 80% of Mongolia's exports source from mineral extraction, a percentage expected to sooner or later increase to 95%. Around 3,000 mining licenses in Mongolia have been issued to date (The Economist, 2012).

The management of cultural diversity is becoming a critical issue for companies in Mongolia since expatriates have sought greener pastures within the country. In particular, the recent proliferation of Chinese laborers and employers is unprecedented. This trend is likely to continue, for the heads of both countries have endeavored to consolidate their bilateral relation so as to promote cooperation. A case in point is that of Chinese ambassador Wang Xiaolong, who told Xinhua in a recent interview about Mongolia and Chinese relationship. According to him, their relationship is currently at its best in history:

‘On the economic front, the two countries have seen rapid growth in two-way trade in the past decade, from 360 million U.S. dollars in 2002 to 6.6 billion dollars in 2012, among which 3.9 billion dollars were Mongolian exports to China’, said Wang. (Huang, 2013).

1.5 Research Significance

As mentioned at the end of the general background section, this study attempts to investigate the relative importance of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, particularly, PD, MAS and LTO. To the researcher’s knowledge, there is no study which measures relative importance of Hofstede’s dimensions. In addition to theoretical application, to consider China and Mongolia in this study has many practical applications for people of the two countries. The following facts, which are substantiated below, show how pragmatically significant this research is.

1. Most dominant foreign population is Chinese.

2. Most foreign direct invested companies are Chinese owned.

3. There are occasional clashes in Mongolia between people of the two countries. Each of these factors will now be discussed in more detail.

Chinese population in Mongolia

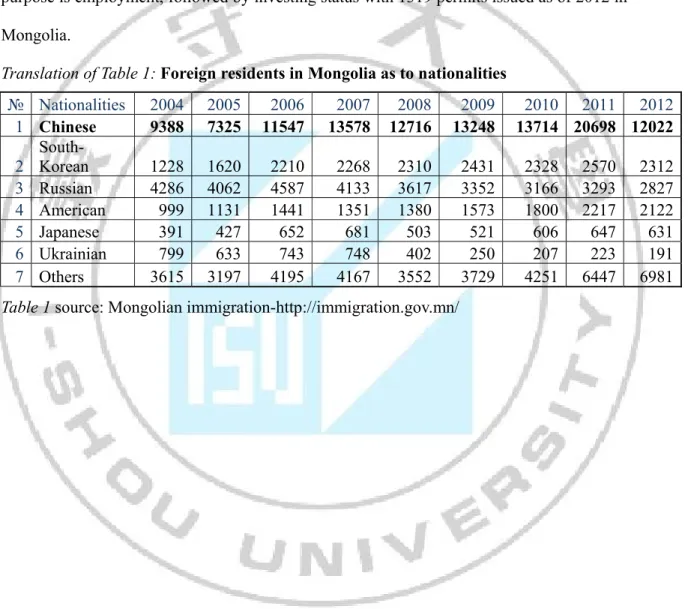

According to Mongolian immigration statistics, the largest number of foreign residents is Chinese, and 9388 of them were accounted for as of 2004 (see Table 1). Chinese population in Mongolia reached a peak of 20698 people in 2011, but the following year this number fell into 12022 (Citizenship and Migration General Authority of Mongolia, 2012). However, although the table does not demonstrate the last two years reports, anecdotal evidence has it that the population of Chinese people has increased again. The second highest number of foreign people is 2827 Russians who were counted as of 2012. Thus, the

number of Chinese 4.5 times larger than the second most numerous group. As a percentage, Chinese people constitute 44 percent of the total foreign residents in Mongolia (see appendix A, table 1). Besides knowing the population of foreign residents, we can see from Table 2 their purpose for coming in relation to issued residence permits’ status. 26744 foreigners obtained residence permits as employment status, which means the dominant purpose is employment, followed by investing status with 1319 permits issued as of 2012 in Mongolia.

Translation of Table 1: Foreign residents in Mongolia as to nationalities

№ Nationalities 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 1 Chinese 9388 7325 11547 13578 12716 13248 13714 20698 12022 2 South-Korean 1228 1620 2210 2268 2310 2431 2328 2570 2312 3 Russian 4286 4062 4587 4133 3617 3352 3166 3293 2827 4 American 999 1131 1441 1351 1380 1573 1800 2217 2122 5 Japanese 391 427 652 681 503 521 606 647 631 6 Ukrainian 799 633 743 748 402 250 207 223 191 7 Others 3615 3197 4195 4167 3552 3729 4251 6447 6981

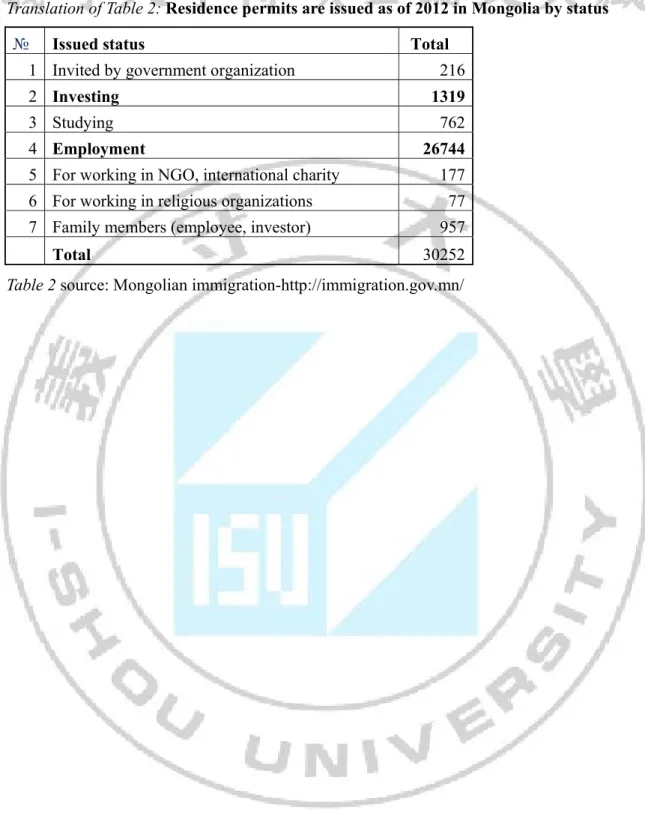

Translation of Table 2: Residence permits are issued as of 2012 in Mongolia by status

№ Issued status Total

1 Invited by government organization 216

2 Investing 1319

3 Studying 762

4 Employment 26744

5 For working in NGO, international charity 177

6 For working in religious organizations 77

7 Family members (employee, investor) 957

Total 30252

Chinese invested companies in Mongolia

As Foreign Investment Regulations and Registration Department, the Ministry of Economic Development of Mongolia (2012) reported as of June 30th 2012, there are 5951 Chinese companies out of the total 12118 foreign invested companies in Mongolia. 8232 Foreign invested companies representing 67.9 percent of all the foreign invested companies are registered to operate in food and trade sectors, currently most attractive sectors for marketers in Mongolia. The second most occupied sector in Mongolia is named as others having 1504 companies and 12.4 in percentage terms (see appendix A table 3). Thirdly, geology and mineral exploration having 413 companies that are followed by engineering construction and construction materials’ manufacturing with 388 companies and Tourism with 312 companies.

Translation of Table 3: Foreign companies in Mongolia as to sectors

Source:http://www.mongolchamber.mn/index.php

Also China has been the biggest investor in Mongolia for more than a decade. It can be seen from a total amount of foreign direct investment coming from China. In the following table, the nine biggest investor countries are demonstrated with their respective investment amount between 1990 to June 30th 2012.

№ Industries % Total (1990-2012.6.30)

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012.06.30

1 Trade, foodservice 67.9 8,232 1,112 1,505 1,515 572 731 872 434

2 Others 12.4 1,504 262 21 3 15 14 15 17

3 Geology, mining and search for mining.

Source:http://www.mongolchamber.mn/index.php/

Clashes between the people

While all those events take place, the growth of nationalists, who are labeled neo-nazis by the western press, has increased all over the country. Nationalists have instigated a number of raids on Chinese and companies owned by Chinese so far. The following incidents were reported by Xinhua news agency in 2005.

“A hotel, a restaurant and a supermarket owned by Chinese in downtown Ulaanbaatar were attacked overnight, leaving one man wounded, sources said Sunday [27 November]. At about 11:30 p.m. Saturday, a group of nearly 40 gangsters tried to break into the "Beijing Supermarket" in downtown Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian capital. They destroyed a door and windows before getting away.

On another occasion, a Chinese restaurant was attacked by some unidentified people. At 1:00 a.m. Sunday, "Fu Xing", a hotel owned by Chinese, was raided and its reception room was seriously damaged. One man staying in the hotel was injured and three mobile

Translation of Table 4: FDI in Mongolia by countries in one thousand USD

Country name % Total (1990-2012.06.30) 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012.06.30 1 China 31.71 3,650,996.96 497,800.88 613,058.80 176,038.36 1,015,265.04 167,496.52 2 Netherland 23.16 2,667,036.01 4,069.20 51,028.60 232,962.18 1,816,714.10 556,240.28 3 Luxemburg 9.01 1,037,196.26 195.8 1,012.65 25,589.47 476,652.07 525,896.34 4 Virgin Islands(UK) 7.48 861,441.27 6,157.89 19,305.18 101,986.27 610,933.11 28,070.02 5 Singapore 5.45 627,075.05 32,339.86 9,359.44 31,075.00 402,738.17 136,974.92 6 Canada 4.23 487,595.94 2,739.57 1,028.00 147,811.12 72,288.16 15,302.75 7 South Korea 2.93 337,736.42 41,765.41 31,673.98 38,763.43 54,972.59 26,950.22 8 USA 2.54 292,657.89 6,466.89 2,571.52 13,911.20 127,238.95 49,728.36 9 Hong Kong(ROC) 1.8 207,007.21 1,757.81 11,032.44 80,148.35 54,366.84 25,289.38

phones were reported missing (Xinhua, 2005).

In addition, fights and clashes between Mongolians and Chinese are not only instigated by the former but are also provoked by Chinese. Regarding this issue, The Economic Observer, the English web-based edition of ‘The Weekly Chinese Newspaper’, reported its investigation. The article written by Song, Zhang, and Wang (2012) reveals some clues to clashes or fights.

The Chinese manager, surnamed Wang, of a Chinese restaurant, who has been in Mongolia for more than four years, says clashes between Mongolians and Chinese take place once in a while, yet sometimes it’s the latter’s fault.

According to Zhao Jurong (赵巨荣), head of a real estate company in Mongolia, thriving Mongolian construction industry has resulted in demand for a massive number of construction workers, which has appealed to many Chinese. Clashes implicating Chinese workers aren’t unprecedented thing in Ulaanbaatar.

In most cases, clashes arise from language barriers and misunderstanding one another. Most Chinese workers in Mongolia come from southern China where the language dialect is very fast and high pitched. Conversely, Mongolians raise their voices when arguing, or they speak with low voices. When being in a close contact with southern Chinese people, Mongolians may misinterpret Chinese talk and think that Chinese are trying to scold them. Chinese workers could also exacerbate problems through their own manner. Some of them stigmatize Mongolians by calling them alcoholic or indolent. Sometimes they scorn

Mongolia’s lack of industrialization in comparison with China’s or say, “Mongolia was once our territory”. Of course Mongolians dislike such insults.

Zhao said that a group of construction workers tends to come together from the same area of China from twelve to a hundred people in it. If one or few Mongolians have a clash with that number of Chinese, certainly they will have trouble. In cases of this situation, Mongolians occasionally call nationalists. As a result, clashes turn into a gang war at times. Generally, the strained relationship between Chinese and Mongolians is so fragile that it can easily turn to a fight, clash or an argument. Merely signing cooperation and mutual development agreements is not adequate to bring harmonious results. Therefore, to reach the goals of the agreements, cooperation between regular people must be carefully fostered in certain ways, one of which may be introducing work-related value distinctions of the two nations to potential businessmen and employees.

If intercultural communication between a Chinese employer or manager and Mongolian workers is taken as unproblematic, it could be an underlying exacerbation factor for organizations or possibly can lead to losses as many famous unfortunate cases such as ones in the introduction.

People with experiences of several months and long stay abroad have increased intercultural competence (Behrnd & Porzelt, 2012). However, most Chinese coming to Mongolia are unlikely to have experience of living abroad or be conscious of cultural value differences. By the same token, most Mongolians who work with Chinese might not have experience of working with foreigners, nor might they be aware of cultural value differences, particularly when culture is viewed through work-related values rather than obvious cultural distinctions such as clothing, food, objects and artifacts.

1.6 Research Objectives

As emphasized in the preceding sections, the two nations have certain cultural differences, which may manifest in the form of social conflicts, (in Power-distance, Masculinity, Long-term orientation) revealed by Hofstede's cultural dimension.

The purpose of this study is to identify relative importance of Hofstede’s above mentioned three dimensions from among five cultural dimensions from a Mongolian worker’s perspective. So the study focused on answering the following question.

1. Which one of the three dimensions has most impact on Mongolians in cases they cooperate with Chinese managers whose cultural background is radically different from theirs?

2. To what extent do differences of power distance, masculinity and long-term orientation predicted by Hofstede really exist in the workplace in Mongolia?

Ultimate purpose of this work is to bring cooperative atmosphere between Mongolian employees and Chinese employers and to rectify any misconception and preconception about each other’s value differences, especially among employers.

To investigate the first research question, this study developed the following null

hypothesis: From a Mongolian employee’s perspective, there is no difference between HPD,

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

OverviewThis chapter begins with the brief overview of cultural value studies, together with definitions for PD, MAS, and LTO provided by Hofstede. Next, the development of cultural research and how cultural studies differ in terms of their scope are briefly discussed. This study is then classified with regard to a particular framework for cultural research. Following on from this, the relevance and utility of cultural values to the workplace relationship are reviewed. Then one study, which was carried out on similar purpose as this study, was reported. Mongolian cultural value scores found by two replications of the IBM study are reported, and radically different raw scores of Mongolia and China are compared in a table. Then, existing anti-Chinese sentiment in Mongolia is shortly discussed. Finally, the review discusses what is already known about work relation between Mongolian employees and Chinese employers and elaborates on underlying reasons that impede the cooperation between the two parties.

2.1

Cultural value study

The concepts of cultural differences in terms of work-related values were pioneered by Hofstede (1980), who carried out a large scale study of national value differences across the worldwide subsidiaries of IBM between 1967 and 1973. He identified four dimensions of cultural values based on the common social structures of over 40 countries; namely 1) high/low power distance, 2) weak/strong uncertainty avoidance, 3) femininity/ masculinity and 4) individualism/collectivism. In subsequent research Hofstede and Bond (1988) identified a fifth dimension, long-term orientation—initially called Confucian dynamism. The definitions of the three cultural values relevant to this study are demonstrated as follows.

Masculinity

A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 120).

Long-term orientation

Long-term orientation stands for the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards – in particular, perseverance and thrift. On the other hand, short term orientation stands for fostering of virtues related to the past and present—in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of face, and fulfilling social obligations (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 210)

Power distance

Power distance is defined as “the extent to which less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 76). The basic elements of society are institutions: the family, the school, and the community. Organizations are the places in which people work for a common goal.

2.2

Types of Cultural Value Studies

Research on culture has investigated main relationship between values and outcomes as well as values as moderators. Main effect studies have been labeled ‘Type 1’ and moderator studies ‘Type 2’ (Lytle, Brett, Barsness, Tinsley, & Janssens, 1995). Within Type 1 studies, two different individual level studies have been further identified; one is cross-cultural, and the other type is mono-cultural (Kirkman et al., 2006). Researchers investigate associations

between individuals’ cultural values and various outcomes in both types of study. However, all individuals emanate from one particular country in mono-cultural studies whilst two or more countries are incorporated in cross-cultural studies. Since this study intends to identify which cultural dimension of Hofstede’s PD, MAS, LTO is important for Mongolian employees, does not include people from other than Mongolia, nor does it compare two nations, it can be labeled as mono-cultural study. To put it simply, this study strives to delve into differences in PD, MAS, LTO that have been found from the literature. To clarify the goal of this research, a couple of things should be emphasized. One is that this study is considering the impact of Chinese cultural values on Mongolian employees with respect to their differences in the three dimensions. The other is that it surveys Mongolian workers to identify which dimension has the greatest impact.

While most previous cross-cultural research has focused on mapping value differences (Hofstede, 1980; House et al., 2004; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1998), recently researchers have noted that merely knowing value differences does not provide much guidance for effective relationship development (Bond, 2003; Smith, 2003) and few studies suggest how to deal with challenges and difficulties that arise from cultural difference (Smith, 2003). One of the gaps this study attempts to fill is determining the most important cultural dimension (value difference) among Hofstede’s power distance, masculinity and long-term orientation from a Mongolian employee perspective, thereby assisting Chinese managers to identify Mongolian employees’ priority value that should be dealt with first and enabling them to mitigate the issues of cultural differences between Chinese boss and Mongolian workers.

One may wonder why it only mitigates the issues of cultural differences experienced by Mongolian workers which arise from Chinese bosses and why not vice versa. The reason is that Chinese society has a high power distance while Mongolian society has very low power distance, so it is assumed that misunderstandings and conflicts will likely occur between

Mongolian subordinates and Chinese supervisors rather than between Mongolian supervisors and Chinese subordinates. Subordinates with high power distance orientation do not readily question authority. But those with low PD orientation do not accept rigorous hierarchical relations. They prefer supervisor/subordinate relationship to be more equal and to have rather personalized relationships with authority figures (Bochner & Hesketh, 1994). Supervisors with high PD are task-oriented and have a tendency not to allow much participation or encourage interpersonal relations with subordinates (House et al., 2004). Nor do they make much effort to communicate, or be more approachable, or be likely to provide personal relationship opportunities or participation (Offermann & Hellmann, 1997). This suggests that we may see unsatisfied feelings from Mongolian subordinates in that regard. However, and what kind of influence do differences in MAS and LTO have on Mongolian workers? And which one is the most valuable for Mongolians? To know more about these questions, the way in which the three cultural values are studied in relation to their significance to workplace relationship will now be reviewed.

2.3

The Utility of Hofstede’s Cultural Values in the Workplace

Researchers have adopted Hofstede’s framework of cultural values, altogether or partially by way of using two to three values on a particular purpose in their research. This section looks through cultural studies that used Hofstede’s values, other than IND, with regard to the workplace relationship like employee commitment, leadership and negotiations at individual as well as organizational level. The review especially tries to show significance of three cultural values of this study in relation to the workplace relationship.

Brett and Okumura (1998) confirmed that joint gains are lower in intercultural negotiations between U.S and Japanese negotiators than in intra-cultural negotiations among either U.S or Japanese negotiators. This finding was based on data from 30

intercultural, 47 U.S-U.S intra-cultural and 18 Japanese-Japanese intra-cultural simulated negotiations in a series of inter- and intra-cultural dyad experiments. They found that US negotiators were more individualistic yet lower in PD than Japanese. Individualists endorsed self-interest in negotiations whereas Japanese negotiators higher in PD endorsed distributive tactics and spent more time discussing power. But they did not attempt to compare the importance of these differences in PD.

Helgstrand and Stuhlmacher (1999) validated Hofstede’s PD and IND constructs through a survey completed by 263 Australian bank employees representing 28 different nationalities. Each participant was assigned a country score for PD and IND-COL and divided into high and low groups on the two values. Collectivists had more informal contact with coworkers, and were more cooperative than individualists. The respondents who were high in PD had more contact with superiors described their supervision as being more direct and close, more task-oriented and had greater beliefs in management style favoring centralized decision making, tight control and hierarchy. In contrast, those low in PD were less open with their superiors.

As regards the relationship between Hofstede’s values and employee commitment, there are certain studies such as Clugston, Howell, and Dorfman (2000) Kirkman and Shapiro (2001). Clugston et al. (2000) assessed the relationships between PD, COL, UA and MAS and an employee’s level of commitment with three bases (affective, continuance and normative) and three foci (organization, supervisor and workgroup) using surveys in a US public agency. PD was positively related to affective commitment to the organization and both continuance and normative commitment were positively related to all 3 foci. UA was related to continuance commitment across all foci; and COL was related to workgroup commitment across all bases of commitment. By using surveys from self-managing work team members in Finland, US, Philippines and Belgium, Kirkman and Shapiro (2001) found that COL was related to team members’ job satisfaction and commitment. It was also found

that resistance to teams mediated the relationships between COL and both satisfaction and commitment while resistance to self-management partially mediated the negative relationship between PD and commitment.

Regarding cultural values in leadership studies, Offermann and Hellmann (1997) examined relationships between cultural values held by over 400 managers representing 39 different nationalities and their leadership practices as assessed by subordinates. Their findings show that PD was negatively related to leader communication, approachability, delegation and team building, and UA was positively associated with more leader control but negatively to approachability and delegation. COL was positively related to team-oriented leadership, and PD and UA were negatively related to participative leadership in a sample of middle managers from countries (House et al., 1999). In examining the existence of culture specific leadership attributes, Javidan and Carl (2005) found a charismatic leader whose attributions are sacrifice, forgoing own interest and elevating subordinates self-esteem, self-confidence (Bennis & Nanus, 1985) and those attributions imply PD, i.e., regarding subordinates as equal rather than seeing as a inferior (Hofstede, 1980).

Mikalauskienė and Štreimikienė (2012) investigated the impact of national culture dimensions on organizational culture dimensions through a comparative analysis. Using the Denison Organizational Culture Survey and comparing the survey results with Taiwan’s, Mexic’s and Lithuania’s respective Hofstede’s culture dimension scores, they found that PD is positively related to involvement, but negatively related to the traits of consistency,

adaptability and mission. MAS is positively connected to involvement, but negatively to

other traits. LTO is positively associated to the organizational traits involvement and

consistency, but negatively related to adaptability and mission. Mission, Adaptability,

Involvement and Consistency are organizational culture dimensions developed by Denison (1990).

first research question of this study and encountered one study by Barkema and Vermeulen (1997), whose study gave attempt in determining which cultural value difference is most disruptive relative to the other cultural value differences for international joint ventures. Their findings disclosed that long-term orientation has a stronger effect on survival of international joint ventures than that of the other dimensions. Even though they found long-term orientation as most disruptive towards survival of international joint ventures, it seems illogical to assume that long-term orientation will also have most disruptive impact on people of any country because culture is defined as shared values that have been studied on two purposes: 1) to facilitate external adaptation of an organization and 2) to facilitate internal integration of an organization (Schein, 2010; Schneider, 1989). External adaption is how an organization relates to a new context (country with different culture) with the awareness of threats and opportunities in it. Obviously, their research was about the outside issues of an organization and was not really about interpersonal relationship within organization. Thus, which cultural value difference is most disruptive for people of a particular nation remains unanswered.

As far as the cultural-value related studies are reviewed here, there is no study that attempts to compare cultural values against each other at interpersonal level. Perhaps this is due to importance of other fields such as management, marketing, consumer behaviors that may have occupied researchers’ attention more. Therefore, the question postulated here in this work needs to be answered for the sake of cooperation and development between the two countries as well as for its contribution to cultural-value related literature. In the following section, the two nationalities observed main differences are shown and are compared to shed some light on their unseen cultural value differences.

2.4

Mongolian Culture according to Hofstede’s dimensions

Sanduijav (2008) and Tkaczuk et al. (2010) measured Mongolian culture in the form of replicating Hofstede’s study. Though earlier briefly introduced in the introduction chapter,

the two studies’ findings are summarized in the following table.

Table 5: Mongolian Cultural dimensions by two different studies

Individualism Power distance Uncertainty avoidance

Masculinity Long-term orientation

Sanduijav 2008 19 12 76 53 43

Tkaczuk 2010 36 7.4 50 6.2 28

From the above table, Mongolian culture can be easily distinguished apart from a radical difference of masculinity scores in two studies. As a Mongolian who has grown up in the culture and the results of the two studies accord with the researcher’s personal observations except for the odd high masculine score of 53 in Sanduijav’s study.

Regarding the odd high masculine score, Hofstede (2005) stressed that age and occupation affects masculinity values. For instance, people tend to become more social and less competitive and egocentric as they age which leads to lower MAS and certain occupations are classified from most masculine to most feminine in his book Cultures and Organization. The most masculine occupations are sales representatives, engineers and scientists, technicians and skilled craftspeople whereas the most feminine occupations are office workers, semiskilled and unskilled workers and managers of all categories (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). With this in mind, it is possible to speculate the reason why Sanduijav (2008) obtained high masculinity score in her study. That 66.3% of her sample comprises age of 25-49 years old people, and academically trained professionals, and vocationally trained craftsperson, technician, information-technologists, nurses, artists or equivalent professionals make up 54.5% percent of the sample while merely 33.5% of the sample encompasses those feminine jobs such as office workers, semiskilled and unskilled workers and managers of all categories. In other words, the sample was not representative of Mongolian society as a whole.

Thus, on the basis of the above indices, the following three conclusions can be drawn regarding Mongolia.

1. Based on low score in PD dimension Mongolia is a country that supports equality in society with the very low scores in power distance index.

2. Based on low score in LTO dimension Mongolians are quite short-term oriented people

3. Based on low score in MAS dimension Mongolian society inclines toward feminine It is useful to consider whether Mongolians were equal in terms of social status due to traditional support for equality or whether they have enjoyed equality by virtue of socialism and democracy. The common belief that Mongolians enjoy equality due to arrival of socialism is likely to be mistaken. In fact, at the commencement of the socialist period numerous Mongolian nobles and lamas were slain by socialists who were committing genocide under the command of Russian socialists. The elimination started in the fall of 1937 killing at least 22000 people out of a population which counted at most 800000. Although all levels of Mongolians were slain, the majority of victims were 18000 Buddhist lamas followed by nobles, political and academic figures (Dashpurev, Soni, & Phil, 1992). On the other hand, there is evidence to suggest that equality was traditionally fostered by most members of Mongolia. Looking through literature on Mongolian culture and society, the review came across a book titled ‘Travels in Tartary Thibet and China’ by Huc (1900) in which the author wrote a great deal about his observations on Mongolians. This 114 year-old-book gives a good insight into traditional Mongolian society and Mongolians who were mostly defined by neighbors: Chinese and Russia during that time. Equality between noble Mongolians and commoners impressed the author. As he stated about equality in Mongolian society,

The noble families scarcely differ from the slave families. In examining the

they live both alike in tents, and both alike occupy their lives in pasturing their flocks. You will never find among them luxury and opulence insolently staring in the face of poverty. When the slave enters his master's tent, the latter never fails to offer him tea and milk; they smoke together, and exchange their pipes. Around the tents the young slaves and the young noblemen romp and wrestle together without distinction; the stronger throws the weaker that is all. You often find families of slaves becoming proprietors of numerous flocks, and spending their days in

abundance. We met many who were richer than their masters, a circumstance giving no umbrage to the latter (Huc, 1900, p. 186).

Even today Mongolians are not much changed from that of old days as to equality. With regard to LTO, Mongolians have extremely short-term orientation which can be seen from Mongolian extravagance and proverbs. It is often observed that Mongolians love to be extravagant about dressing and frittering away money. For example, once in a while it is reported that some families lease their home and others sell their cars to opulently celebrate “Tsagaan Sar”, Lunar year. People in short-term society tend not to be concerned about the future. For example, they do not invest compared to long-term oriented people, nor do they foster thrift (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

In traditional Mongolian culture, wealth is not very important which may be the reason why Mongolians have today’s feminine society as postulated by (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Mongolians are nomadic people. As such, collecting wealth is an unnecessary load when they move to settle another place. One kind of Mongolian proverbs is “Yortontsiin 3” which literally means three things of the universe. It tries to define everything abstract to objects in the universe within a three line verse from a Mongolian viewpoint. Regarding the notion of wealth, Yortontsiin 3 teaches,

“Knowledge is the greatest wealth To have children is the moderate wealth

Material is the least wealth (Erdene & Sanjperlee, 2012).1”

In Mongolian culture thus material wealth is traditionally not deemed to be the most valuable concern. Yortontsiin 3 has no author, and initially it was orally passed to a next generation by Mongolians. It is widely known in Mongolian society.

Comparison of Mongolia and China in Three Dimensions

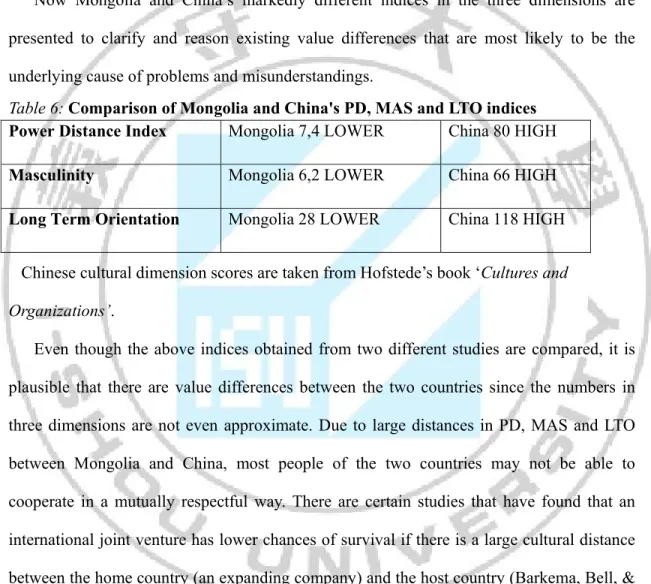

Now Mongolia and China’s markedly different indices in the three dimensions are presented to clarify and reason existing value differences that are most likely to be the underlying cause of problems and misunderstandings.

Table 6: Comparison of Mongolia and China's PD, MAS and LTO indices Power Distance Index Mongolia 7,4 LOWER China 80 HIGH

Masculinity Mongolia 6,2 LOWER China 66 HIGH

Long Term Orientation Mongolia 28 LOWER China 118 HIGH Chinese cultural dimension scores are taken from Hofstede’s book ‘Cultures and

Organizations’.

Even though the above indices obtained from two different studies are compared, it is plausible that there are value differences between the two countries since the numbers in three dimensions are not even approximate. Due to large distances in PD, MAS and LTO between Mongolia and China, most people of the two countries may not be able to cooperate in a mutually respectful way. There are certain studies that have found that an international joint venture has lower chances of survival if there is a large cultural distance between the home country (an expanding company) and the host country (Barkema, Bell, & Pennings, 1996; Barkema, Shenkar, Vermeulen, & Bell, 1997; Li & Guisinger, 1991). The same thing might apply to many of Chinese owned businesses in Mongolia.

Also, one study measured cross-cultural differences in Central European countries

1Эрдэм ном дээд баян

(Kolman, Noorderhaven, Hofstede, & Dienes, 2003). One of their findings was strikingly similar to Mongolia and China context which was cultural value differences in three dimensions. Kolman et al. (2003) found that Slovakia markedly differed from the Czech Republic on four of the five dimensions regardless of geographical proximity and the past historical event of being one nation for many decades. On the basis of this finding, the authors surmise that it may be difficult to unite activities in these two countries in a single integrated organization. Their conjecture might seem true at least in Mongolia and China context.

Numerous studies have replicated Hofstede’s IBM study at the individual, organizational as well as country level and reached scores similar to the origial IBM study. As Hofstede pointed out, there are six major replicated studies at the country level between 1990 and 2002 covering between 14 to 28 nationalities; four of the six replications confirmed three out of the four dimensions—and each time the one missing is different. As it is explained, “the missing one is because the respondents included people without paid jobs at all such as housewives and students” (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005, p. 25).

Even though there is not any available cross-cultural comparative study of China and Mongolia, one study of Taiwanese doctors compared with Mongolian doctors and nurses has been carried out by Wu, Batmunkh, and Lai (2011). Taiwanese originally come from China so that they can to a certain extent represent China and hold rather similar value that is evidenced by G. Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) dimension scores for the two countries.

Their comparative case study found that Mongolian participants were more individualistic than Taiwanese doctors (Wu et al., 2011). However, regarding other comparisons in PD, MAS, their study seem to provide nothing due to the authors’ misinterpretation of MAS and PD. For instance, as they put it, “most of the doctors of both countries prefer male supervisors when in communication as they find them easier to understand both with each other and in the working environment” (Wu et al., 2011, p. 81). In fact, MAS has less to do with gender

preference yet much to do with preferred values of assertiveness and materialism. If both men and women prefer competitiveness and material success in a particular society, they are regarded as high in MAS. In contrast, a feminine society prefers the quality of life rather than material success and competition regardless of gender (G. Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Since their study is at organizational level and compared two groups each consisted of 9 people from each country, their findings cannot give useful information as the authors themselves mentioned future research may use quantitative approach on a greater scale. Nonetheless, this kind of cross-cultural study is somewhat outside the scope of this study since this study was defined as a mono-cultural study

Sinophobia as a barrier

As stated in the preceding chapters, intercultural activity between Mongolia and China has been animated, and two countries are on the verge of further mutual development. However, the existence of sinophobia in Mongolia is undeniable. Mongolia has some mistrust of its south neighbor for a long time. Rather than looking back to the old dispute, national hatred and wars between Mongolia and China, this section reviews contemporary anti-Chinese feelings among Mongolians which might adversely impact on the collaboration between the two nations’ people.

Billé (2008) carried out some fieldwork on anti-Chinese sentiment among Mongolians by looking at oral narratives in the country. During his stay in Mongolia, Billé conducted an interview with many Mongolians, observed the media and was conscious of other social activity in relation to anti-Chinese sentiment among the everyday Mongolians. In his research Billé identified three discussion subjects—threat to the nation’s territory, threat to the body and threat to Mongolian reproduction—about which Mongolians concern and feel threatened by China and its people. He claims that current anti-Chinese discourse was initially developed by Marxist ideology during socialist era. Billé concluded his research by stating that anti-Chinese discourse is fractured along a number of fault lines. For instance,

Mongolians who have direct personal experience with China no longer align themselves with mainstream discourse. This is true for particularly Mongolians who visited modern China cities such as Hong Kong, Shanghai. Another fracture is in gender, for Mongolian women were less nationalist compared with males. Therefore, Billé’s research findings support Bulag (1998) and Tumursukh (2001) who argue that nationalist discourse in Mongolia is mainly talked by males and that xenophobia is supported by strong patriarchal values and ethics.

Challenges Encountered by a Chinese employer in Mongolia

Although conflicts and anti-Chinese sentiments arisen from misunderstandings, prejudice or historical issues between the ordinary people have been studied by certain researchers such as Bulag (1998), Tumursukh (2001) and Billé (2008), how cultural value differences affect on workplace relationship between Chinese and Mongolians is unknown and is not really brought up into academic discussion. One newspaper article published in China, Song et al. (2012) wrote about challenges encountered by Chinese employers in Mongolia under the subtitle of ‘Irreplaceable Workers’:

It’s not easy to find workers in Ulan Baatar. Although Mongolians often complain that Chinese workers are taking their jobs, when companies come to recruit, there’s a small pool of local laborers. Even if a company can find Mongolian workers, management is a headache. From the view of Chinese bosses, Mongolian workers are lazy, alcoholic and unwilling to adhere to normal working hours. No matter whether it’s in the real estate or mining industry, Chinese bosses tend to prefer Chinese workers, even if the cost is higher.

It is obvious that the manner of managing Chinese employees does not work when it comes to Mongolian workers. The underlying reason seems to be that their work related value distinctions, as they are illustrated in the previous table 4, the two nations stand in two opposite poles in the three dimensions. To put it simply, the way Mongolian workers view

work differ from their Chinese counterparts.

From a Mongolian point of view, problems between a Chinese boss and Mongolian employees written by Munkhtsetseg (2008), a journalist, tells a story of a strike by tailors in a Chinese company in Ulaanbaatar. The complaints give a clue to cultural value differences:

Employees work from 8:30am to 17:30pm five days in a week. Yet on Tuesdays and Thursdays they work until 02:00 am. In case of coming late to the work, getting sick and taking leave, the employees get punished to pay a fine of 5000 to 10000 tugrug, Mongolian currency. Moreover, it is common that the tailors get locked from outside during work time, and that they work without having their locker keys. In addition, their lunch time is just 5 minutes. Just to go to a restroom for three minutes, the employees have to go through red tape to get the permission. If the servant arbitrary opens the restroom’s door for any of employees, there is a dominating rigid rule that takes measures on her. In response to their complaints, the Chinese boss said that a Mongolian worker who works as a tailor cannot be found. So the contract to take 300 employees from North Korea has been made (Munkhtsetseg, 2008).2

Apparently, a Chinese employer’s workplace requirement hardly meets Mongolian employees’ expectations. From the above complaints, it looks like the Chinese boss’s 2 Ажилчид долоо хоногийн таван өдөрт 08.30-17.30 цаг хүртэл хөдөлмөрлөдөг гэнэ. Харин мягмар, пүрэв гаригт 02.00 цаг хүртэл ажилладаг байж. Хэрэв ажлаасаа хоцорч, өвчилж, чөлөө авбал халах юм уу 5-10 мянган төгрөгөөр торгодог байна. Улмаар ажлын цагаар гаднаас нь цоожилж, хувцасны өлгүүрийн түлхүүрийг нь өгөхгүй ажиллуулах тохиолдол энгийн үзэгдэл гэнэ. Дээрээс нь тэдний цайны цаг ердөө тавхан минут аж. Харин гуравхан минутад 00-д орохын тулд олон шат дамжлагаар бичиг цаас бүрдүүлдэг гэнэ. Хэрэв үйлчлэгч дураараа ариун цэврийн өрөөг онгойлгож өгвөл түүнд арга хэмжээ авдаг хатуу "хууль" ноёрхжээ. Хариуд нь захирал А.О.Фин нь оёдолчин хийх монгол ажилтан олдохгүй байна. Хойд Солонгосоос 300 ажилтан авах гэрээ хийсэн. Хятад эзэнтэй үйлдвэрийн монгол оёдолчид ажил хаялаа. Мөнхцэцэг, М. (2008). from http://archive.olloo.mn/modules.php?name=News&file=print&sid=1140276

discipline is regarded too rigid for Mongolians. On the other hand, the Chinese employer endeavors to make his tailors work by setting certain rigid rules. Of course, the Chinese boss seems to have values of high masculinity and long-term orientation as well. The all concerns expressed by the Mongolian tailors imply that they are low in MAS and prefer well-being and quality of live over success or money. For example, in their view, sometimes coming late to the work, getting sick and taking leave is okay. For such things, an employer should not impose any fine on employees. Also they want more time for having lunch and going to toilet.

Because “management study in Mongolia is a relatively new subject, and there are no empirical studies in local managerial values and practices” (Manalsuren, Weir, & Hopfl, p. 9), and there is also no intercultural management study that involves China and Mongolia, this research has done a little survey using Google survey among 53 Mongolian employees who work under Chinese employers prior to conducting a main survey based on Hofsede’s predictions in differences of PD, MAS and LTO societies. The minor survey focused on asking a few questions including multiple choice question and open ended question with regard to differences in three dimensions such as do you think that your Chinese boss seems too strict when it comes to the following. The multiple choices consisted of answers like ‘to grant leave or to give days off’ and ‘to promote one’s position.

The results for this multiple choice questions showed that 62% of the respondents consider their boss as strict when granting leave and giving days off, and 53% of the respondents view their boss strict when giving promotion. The open-ended question asked ‘if they have encountered similar kind of problems like long delay of promotion or refusal of a day leave request’. Not surprisingly, the responses for the open-ended question imply that there is dissatisfaction about those kinds of different views of a Chinese employer. There are many instances of dissatisfied comments on absence of promotion and refusal of leave requests. For example, one female respondent expressed her dissatisfaction saying

that ‘when her Chinese boss grants leave, the boss asks too many questions’ showing that seems an invasion of privacy for her. On the other hand, one male respondent comment was that ‘no matter how well you work, your position won’t get changed from initial position’. Not only secondary data produced by Sanduijav (2008) and Tkaczuk et al. (2010) G. Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) and the stories of workplace conflicts but also my preliminary survey result convince me that differences in PD, MAS and LTO really exist between two nations; therefore, to prioritize those differences from a Mongolian employee perspective might be helpful to a Chinese employer.

2.5

Summary

This chapter shortly presented the overview of Hofstede’s cultural value study and the definitions of chosen three cultural dimensions: PD, MAS, and LTO. After that it introduced several types of cultural studies in relation to their differences in scope, as well as identifying common trend in cultural studies. This study was categorized with regard to a particular framework for cultural research. Then the chapter reviewed the relevance of Hofstede’s cultural values to management, employee commitment, leadership, and so forth. Mongolian cultural value scores found by two studies were reported and interpreted; interpretations for indices were then supported with social phenomena. Radically different indices of Mongolia and China were contrasted in a table. Further, anti-Chinese sentiment in Mongolia is briefly presented. At end of the chapter, it demonstrated existing work relation issues between Mongolian employees and Chinese employers and elaborated on underlying reasons in connection with cultural value differences.