Chapter Two Literature Review

This chapter reviews literature on the linguistic features of English RCs and

acquisition of this complex construction by EFL/ESL learners. Section 2.1 generally

describes English RCs in terms of their structural and functional properties. Section

2.2 presents previous empirical studies on variables that have been found to influence

English RC acquisition, in particular, L1 interference and universal factors.

2.1 General Descriptions of English Relative Clauses

This section gives a brief overview of English RCs with respect to their structure

and function. The descriptions are presented in general terms, since an extensive

linguistic analysis of the construction is not intended here. Only those aspects of

English RCs that serve as the basis of materials for the present study are discussed,

including (1) the syntactic dimensions of English RCs as a post-nominal, clause-size

noun modifier; and (2) the functional dimensions of English RCs as a

referent-tracking strategy, an information-adding interpolator, and a backgrounding

device.

2.1.1 Syntactic Dimensions of English Relativization

In transformational terms, the relative construction in English has for a long time

been viewed as being formed via the process of relativization, in which the input is a

simple sentence and, with such rules applied as relative marker substitution and

relative marker fronting, the output is a post-nominal RC as a clause-size noun

modifier within a noun phrase (NP) (Givon, 1993: 107). Syntactically, it is a

subordinate clause which is embedded inside an NP in another higher-order or

superordinate clause in such a manner that it becomes part of the main clause as a

complex adjectival construction1. Take sentence (3) below for example:

(1) The woman who is standing next to the door is my teacher.

In (3), the RC who is standing next to the door is closely associated with the NP the

woman in the main clause in that they together form a complex NP: the woman who is standing next to the door, where the RC is incorporated into another superordinate

clause and functions much like an adjective. Without the relative construction, one

would not have other ways of expressing the same proposition than coding it in two

independent clauses, as shown in (4):

(2) The woman is my teacher. She is standing next to the door.

(Or: The woman is my teacher and she is standing next to the door.)

The RC is so called because it is related to the matrix clause by virtue of the

co-referential relationship held between its antecedent in the main clause and an

anaphoric element, either overt (e.g. relative pronouns and determiner: who, whom,

which, whose) or covert (e.g. the subordinator/complementizer that and the zero

1 This embedding nature of English RCs applies to restrictive ones only. In a strict sense, non-restrictive RCs are not considered embedded clauses as they are often separated from head NPs by an intonational break (or a comma in writing).

relative Ø), in the embedded clause (Huddleston et al., 2003: 1034). Take sentence

(3) above for example. The overt anaphoric marker who is interpreted as

co-referential with the NP the woman as it is used to replace the same NP the woman

in the RC, as can be illustrated in (5):

(3) The woman〔who is standing next to the door〕is my teacher.

>The woman〔the woman is standing next to the door〕is my teacher.

Normally, the choice of the anaphoric element or relative marker in English RCs

depends on the following three factors (Quirk et al., 1985: 1247-1248): (1) the

relation of the RC to its antecedent─whether it is restrictive or non-restrictive (e.g.

the complementizer that and the zero relative Ø cannot be used in non-restrictive

RCs); (2) the animacy of the antecedent─whether it is human or nonhuman; and (3)

the grammatical function of the relative marker─whether it functions as a subject, an

object, a prepositional complement, a predicative complement, a determiner, or an

adverb.

With regard to relativization sites ─namely, which grammatical roles of a

co-referent noun in the embedded clause can be relativized─English RCs can

syntactically be divided into seven types: subject, direct object, indirect object,

prepositional object, predicative complement, possessive determiner, and adverb, each

exemplified in the following sentences:

(4) Subject: They are delighted with the person who has been appointed.

(5) Direct object: They are delighted with the person who we have appointed.

(6) Indirect object: They are delighted with the person who we gave a call to.

(7) Prepositional object: They are delighted with the person who we spoke to.

(8) Predicative complement: She is the perfect accountant which her

predecessor was not.

(9) Possessive determiner: The woman whose daughter you met is Mrs. Brown.

(10) Adverb: 1950 is the year when I was born.

When taking into account the syntactic position in the matrix clause of NPs being

modified by RCs, one then has a greater variety of English RCs.2 Part of this

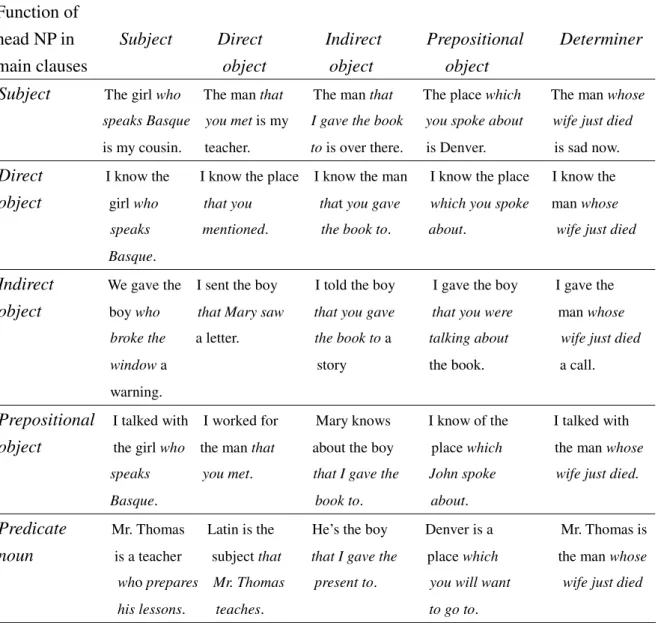

diversity is well illustrated in Table 1:

2 For the sake of research focus, the scope of the present study is limited to those prototypical, fully-fledged RCs as in examples (6)-(12) above, as opposed to such variant RC types as reduced RCs (i.e. prepositional, participial, or adjectival phrases), free (headless or fused) RCs, cleft RCs, or non-finite RCs, as in examples (i)-(iv) below, respectively:

(i) Reduced RC: The woman standing next to the door is my teacher.

(ii) Free RC: What happened then was strange.

(iii) Cleft RC: It was Kim who wanted Pat as treasurer.

(iv) Non-finite RC: We found someone to fix the roof.

However, among the seven RC types, classified in terms of relativization sites, predicative complement and adverb RCs are excluded from the study due to the low frequency of the former and the interchangeability of the latter with prepositional object RCs─for instance, 1985 is the year in which I was born is synonymous with 1985 is the year when I was born.

Table 1: Example sentences for various relative clauses in English (adapted from Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999: 579)

Function of identical (i.e. relativized) NP in relative clauses Function of

head NP in Subject Direct Indirect Prepositional Determiner main clauses object object object

Subject The girl who The man that The man that The place which The man whose speaks Basque you met is my I gave the book you spoke about wife just died is my cousin. teacher. to is over there. is Denver. is sad now.

Direct I know the I know the place I know the man I know the place I know the

object girl who that you that you gave which you spoke man whose speaks mentioned. the book to. about. wife just died

Basque.

Indirect We gave the I sent the boy I told the boy I gave the boy I gave the

object boy who that Mary saw that you gave that you were man whose broke the a letter. the book to a talking about wife just died window a story the book. a call.

warning.

Prepositional I talked with I worked for Mary knows I know of the I talked with

object the girl who the man that about the boy place which the man whose speaks you met. that I gave the John spoke wife just died.

Basque. book to. about.

Predicate Mr. Thomas Latin is the He’s the boy Denver is a Mr. Thomas is

noun is a teacher subject that that I gave the place which the man whose who prepares Mr. Thomas present to. you will want wife just died his lessons. teaches. to go to.

2.1.2 Functional Dimensions of English Relativization

English RCs can be categorized as either restrictive or non-restrictive,3

depending on whether they serve the function of tracking down a referent or adding a

parenthetical assertion. Since restrictive RCs represent the prototype of RCs, we

3 As indicated by Morris (1969), different terms have been proposed for the same restrictive─

non-restrictive distinction of English RCs, such as defining─non-defining, restrictive─descriptive, restrictive─continuative, restrictive─amplifying, and restrictive─parenthetical. In this paper, we shall retain the terms “restrictive” and “non-restrictive,” since they have wider currency in the

will first expound their functional aspects.

2.1.2.1 Restrictive Relative Clauses as a Referent-tracking Strategy

Semantically, restrictive RCs (henceforth RRCs), as their name suggests, serve to

restrict the denotation of an NP they modify to a smaller subset (Quirk et al., 1985:

1239). That is, they have the effect of further delimiting the domain of reference of

an NP, thereby specifying to the hearer exactly which one(s) or what type/kind is

meant by the speaker. Consider:

(11) The runners who reached the finishing line were hailed by the crowd.

In (13), the RRC functions to narrow the whole set of runners down to a smaller

group of runners─i.e. only those runners who had reached the destination were

cheered by the crowd, whereas the unsuccessful others were not. Without the

modification supplied by the RRC to single out a limited subset of runners, the hearer

of (13) would have difficulty knowing which runners are being referred to by the

speaker.

Functionally, RRCs serve to furnish essential information to assist the hearer in

tracking down a referent in question as either a known entity or a particular type

(Givon, 1990, 1993, 2001). In tracking down a referent, RRCs at the same time

serve to establish in the hearer’s mind a coherence relation for it (i.e. referential

coherence). More specifically, RRCs also function to make a referent relevant to the

hearer at the particular point when it is mentioned by grounding─or relating─it to

his/her pre-existing knowledge base or abuilding mental text-structure.

According to their scope of referent-tracking (i.e. a known entity versus a

particular type) and direction of referential grounding (i.e. anaphoric versus

cataphoric), English RRCs can be further divided into two functional subtypes:

identifying RRCs and characterizing RRCs4.

2.1.2.1.1 Restrictive Relative Clauses that Identify Definite NPs

Most typically, RRCs are used to help the hearer identify an already known

referent in his/her current knowledge base. According to Givon (1993: 108), the

common communicative context for using RRCs is “when the speaker assumes that a

referent’s identity is accessible to the hearer─i.e. definite─but not easily accessible,”

that is to say, the hearer needs some reminding so as to track down the known referent.

Therefore, to aid him/her in successfully identifying the referent, the speaker further

provides a proposition depicting an event/state presumably familiar to the hearer in

which the referent participated as subject, direct object, indirect object, etc. This

explicit cuing proposition is then manifested syntactically as an RRC which carries

presupposed (i.e. old) information to modify a definite NP (i.e. with the definite

4 This functional categorization of RRCs is based on Givon’s (1990; 1993; 2001) comprehensive accounts of English RRCs, and for ease of reference, the researcher here adopts two terms,

“identifying” and “characterizing,” to refer to the two functional subtypes. The two terms in effect correspond to “grounding” (or “anchoring”) and “description,” respectively, employed by Fox and

article the). To illustrate this point, sentences (14) and (15) are given:

(12) The woman who is standing there is my teacher.

(13) The woman I told you about is now my teacher.

In order for these RRCs to fully assist the hearer in identifying the referent of the

woman, the speaker must assume that the hearer of (14) has somehow noticed the

woman sitting there and that the hearer of (15) still remembers what the speaker

previously told him/her. This is so because if the hearer is not familiar with the

event/state coded in an RRC, he/she in turn has no way of identifying a particular

participant involved in that event/state.

Obviously, this identifying type of RRCs typically partakes in an anaphoric

grounding, making a definite referent cohere (i.e. relevant to) with the hearer’s

readily-available mental storage of past experience. They, in conjunction with the

definite article the, overtly prompt the hearer to launch a mental search for the

referent in his/her “episodic–text memory or speech situation model” (Givon, 1993:

114).

2.1.2.1.2 Restrictive Relative Clauses that Characterize Indefinite NPs

The characterizing type of RRCs, on the other hand, is used to provide a

description or qualification of a new referent (either logically referring or

hypothetically referring) in order to “alert the hearer as to what the new referent is

like as a type.” (Givon, 1990: 647) In contrast to identifying RRCs, characterizing

RRCs typically track down a referent that is not previously known to the hearer, and

code a proposition assumed by the speaker to be completely new information (but not

asserted) to the hearer. Accordingly, the head NP of such RRCs tends to be

indefinite, either non-referring or referring. Below are examples of RRCs with

non-referring-indefinite and referring-indefinite head NPs (from Givon, 1993:

110-117):

(14) Non-referring: Anybody who marries my sister is asking for trouble.

(15) Non-referring: I know no man who would do this.

(16) Non-referring: Women who love too much are often disappointed.

(17) Referring: A man who had no shoes on collapsed in the bread-line.

(18) Referring: I know a woman at work who you’d enjoy meeting.

For RRCs with a non-referring-indefinite head NP, as in (16), (17), and (18), the

information contained is not presupposed but assumed to be new to the hearer.

Specifically, these RRCs “always fall under some non-fact modality, either irrealis or

the habitual” and “code hypothetical states/events” in which their non-referring head

is a participant (Givon, 1993:115). Accordingly, such RRCs as (16)-(18) express a

conditional relationship with their non-referring head, as is illustrated by their

semantic equivalents of (21), (22), and (23), respectively:

(19) If there is a man who marries my sister, he is asking for trouble.

(20) If there is a man who would do this, I do not know him.

(21) If there are women who love too much, they are often disappointed.

In a strictly logical sense, the heads of these RRCs are indeed non-referring; however,

in pragmatic terms, they can be regarded as referring to a hypothetical individual

verbally established in the universe of discourse.5 Therefore, RRCs with a

non-referring-indefinite antecedent serve to signal to the hearer what kind of

hypothetical (non-)individual is being referred to by the speaker.

The referential grounding of these RRCs can be either anaphoric or cataphoric,

depending on the referential status of their participants (Givon, 1993: 116). For

instance, the RRCs in (16) and (17) contain the previously introduced participants my

sister and this, thus grounding their heads anaphorically to the preceding discourse;

the RRC in (18) contains no such participants, thereby establishing for its head some

cataphoric coherence with the subsequent discourse.

For RRCs with a referring-indefinite head NP, as in (19) and (20), the

information status of these RRCs is just as new as that of their main clauses. Since

the event/state depicted in such RRCs is not presupposed as old information, it would

be counterintuitive to expect the hearer to be able to identify a participant from the

5 As Givon (1993: 213-214) argues, reference in language is not a mapping from linguistic expressions to individuals in the Real World, but rather to individuals in some universe of discourse.

event/state he/she does not know. Therefore, their head NPs are marked as indefinite,

and these RRCs mainly serve to present the hearer with a salient mental

representation of a new referent that cues the hearer as to what kind of entity─in (19)

and (20), for example, what kind of man or woman─is being referred to.

Regarding their referential grounding, these RRCs ground a referring-indefinite

referent catephorically to the hearer’s abuilding mental structure of text, rather than

his/her memory-stored past experience. In other words, they instruct the hearer to

establish a coherence relation for the referent with the incoming─or yet-to-be

transacted─discourse (Givon, 1990: 647-648).

It is worth noting that characterizing RRCs can often be exploited as a useful

presentative device. To be precise, when occurring in the beginning position of a

discourse unit, RRCs with indefinite NPs, besides characterizing, further serve to

introduce a thematically important, new referent into the discourse (Chen, 2004). To

illustrate this point, text (24) is given:

(22) From the outset, the Grameen Bank was built on principles that ran counter to the conventional wisdom of banking. It sought out the very poorest borrowers, and required no collateral. At first, Yunus offered loans to men because they, typically, were the bread-winners. But men frequently would gamble or drink away the money, he learned. Women turned out to be far more reliable borrowers, and unlike their husbands, they invested their money in food, clothing, and education for their children. Across cultural and geographical boundaries, these facts have held true, and most micro-lending organization now target women.

--“Poorest Women Gaining Equality”

(from Chen, 2004: 35) In text (24), the underlined RRC helps present the new NP principles as the topic for

the following discourse in two aspects. On the one hand, the RRC marks the NP as

the discourse topic by giving it a salient initial description that facilitates subsequent

reference (Givon, 2001: 177). On the other, the RRC also paves the way for the

development of this discourse topic by coding information about it that is going to be

further discussed (Chen, 2004: 36), which is evident from the rest of the text

explaining how the principles of the Grameen Bank are different from those of

traditional banks.

With such a discourse function in topic construction, RRCs are often used as an

extra predication attached to a presentative clause with either existential there or such

verbs as be, live, come in, appear, get, have, know (Givon, 1993: 206-209; 2001:

209-210), as exemplified in (25) and (26):

(23) Clause with existential there: There is a man here who wants to see you.

(24) Clause with a presentative verb: A man came in yesterday who lost his

wallet.

In some sense, presentative RRCs, in comparison with their main clauses, carry

foreground information (as opposed to background information), i.e. important

information that contributes to the development of the discourse─a contradiction to

Givon’s (1979: 55) claim that in English, foregrounding tends to be realized

syntactically as main clauses, and backgrounding, subordinate clauses. Normally,

these presentative RRCs act as the main focus of the whole sentence, namely, the

significant part of what the speaker has to say. Compare sentences (27) and (28)

with (25) and (26) above:

(25) ?There is a man here.

(26) ?A man came in yesterday.

Without the original RRC predication, the resulting sentences (27) and (28), though

grammatically correct, are pragmatically odd in that there is little, if any, information

value in the two semantically bleached sentences. The facts that there is a man here

and that a man came in yesterday are not in themselves sufficiently newsworthy to be

worth saying, that is, they are something that would, in many contexts, “go without

saying.” However, with the addition of RRCs, they provide a piece of relevant and

important information that advances the discourse and serves as the locus of

information in the sentences (Zhao, 1989, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992). This

information-focusing, associated with presentative RRCs, may well explain the

motivation for extraposing an RRC when it serves as a presentative device, as in (26),

since the focused information more often than not occurs at the end of a sentence.

2.1.2.2 Non-restrictive Relative Clauses as an Information-adding Interpolator

Semantically, English RCs are regarded as non-restrictive when they do not

denote a specification of a subset of a larger set of referents, but merely supply

additional, incidental information to further elaborate on the head NP,6 information

that is non-essential to the identification or characterization of the head. An instance

of English non-restrictive RCs (henceforth NRRCs) is given in sentence (29), which

is the same as (13) above, except for commas that separate the RC from the main

clause:

(27) The runners, who reached the finishing line, were hailed by the crowd.

In (29), the NRRC plays no role in singling out a restricted domain of reference of the

NP the runners but rather just elaborates on it as a whole with extra information─i.e.

the runners were all hailed by the audience and they made it to the finishing line.

In thematic terms, the information contained in NRRCs “is presented as separate

from, and secondary to, that encoded in the remainder of the superordinate clause7,”

whereas the information contained in RRCs “forms an integral part of the message

conveyed by the larger construction” (Huddleston, 1984: 399) in that such

information is needed to define a given subset of the set denoted by the NP they

6 According to Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999: 595), in terms of their antecedent, English NRRCs can be subdivided into appositive, where NRRCs refer to and elaborate on an NP in the main clause, and commentary, where NRRCs (always with the relative pronoun which) refer to and comment on the entire preceding main clause (cf. RRCs can only modify NPs, not clauses). The two types of NRRCs are represented by (i) and (ii), respectively:

(i) Mr. Wang, who is a dentist, likes to talk with people around him.

(ii) My favorite baseball team has won the game, which is something to celebrate.

7 The low integration of information between NRRCs and their main clauses may explain why they are often set off from each other by commas or other punctuations. This is because according to the theory of iconicity, the weaker the semantic bond is between two propositions, the farther will they be from each other in their linguistic manifestations, and vice versa.

modify. Take (13) and (29) again for example. Were the RC in (29) omitted, one

would still be able to understand the meaning of the remaining sentence; however, in

the case of (13), one would not be able to do so because he/she would be left

wondering exactly which runners are being referred to.

English NRRCs always modify referring (including definite and indefinite) NPs,

but not non-referring ones, as in (30) and (31):

(28) *Anybody, who marries my sister, is asking for trouble.

(29) *I know no man, who would do this.

This is so because pragmatically, it is unnecessary to elaborate on a non-existent

referent. Moreover, being only amplifying, i.e. non-limiting, NRRCs tend to modify

referentially accessible NPs, namely, NPs whose referents are well established in

context in such a way that further restriction on the domain of their reference is

superfluous (Frank, 1972: 281). These referentially accessible NPs include (1) NPs

which are definite by virtue of the prior discourse; (2) NPs which are definite by

virtue of the speech situation; (3) NPs which are narrowly specified with extra

modifications; (4) NPs which refer to the entire class, rather than part of it; (5) NPs

which refer to a particular class or category of people or things; (6) personal pronouns,

proper NPs, and one-of-a-kind NPs, all of which are referentially identifiable due to

their lexical connotations of “uniqueness” or “being the only one.” Examples of

NRRCs with these NPs are respectively given in the following sentences:

(30) Linguistically definite NPs: Late in the evening, I went out to the store for a

cup of coffee. The coffee, which had been boiling for a long time there,

tasted rather rancid.

(31) Situationally definite NPs: This novel, which I finished reading yesterday,

has a really interesting plot.

(32) Narrowly specified NPs: My new Oriental rug, which was handmade in

India, has a contemporary design.

(33) Whole-referring NPs8: I taught English to some children today. To my

surprise, all the children, who were only 9 years old, were really quiet and

attentive during the class.

(34) Generic NPs9: Elephants, which have a long nose, can easily pick up heavy

things.

(35) Personal pronouns10: I, who you all know, will speak now.

Proper NPs: Many people congratulated William Faulkner, who had just

8 Whether an NP refers to the entire class or part of it should depend on context. Compare (35) with sentence (i), where the NP children refers to a subset of the whole group:

(i) I took some children to a playground for different games. As soon as we arrived, children who wanted to play soccer ran to an open field while the others just stayed nearby to play basketball.

9 Many NPs can be used as either common NPs or generic NPs, depending on context. Compare (36) with sentence (i), where the same NP elephants is used as a common NP and thus modified with an RRC:

(i) Elephants which are kept in the Taipei Zoo can easily pick up heavy things.

10 The personal pronoun, he, in particular, can be used with RRCs to refer to people in general, as in (i) below:

(i) He who laughs last laughs best = People who laugh last laugh best.

won the Nobel Prize for literature.

One-of-a-kind NPs: Mary looked up at the moon, which was very bright

that evening.

Functionally, English NRRCs carry the communicative intent of “parenthetical

comments or afterthoughts” (Radford, 1988), conveying supplementary information

that serves to amplify the ongoing discourse. As Givon (1990: 649; 2001: 179)

argues, the pragmatic condition for using NRRCs is when the speaker considers that

some additional information may somehow be useful to the hearer, though the

information conveyed is indeed less central to the discourse topic under discussion.

This incidental information then surfaces syntactically as NRRCs, which typically

carry propositions that are not presupposed but asserted as new information to the

hearer.

Echoing Givon’s view of NRRCs as interpolating parenthetical assertions are

Tao and McCarthy (2001), who examined the use of NRRCs in British and American

spoken data. In the light of their spoken corpus evidence, it is concluded that

NRRCs generally fall into three broad functional subtypes, each of which can be

thought of as reflecting the parenthetical nature of NRRCs. The first subtype is

expansion: “the addition of information offered by the speaker as topically relevant,

i.e. about the same person or object, or as a projection of the information needs of the

listener” (p. 663). Consider:

(36) (Speaker 2 is on the phone checking seat allocations with speaker 1, an airline employee, for a forthcoming plane trip)

Speaker 1: What we’ve got is E and G, which is aisle and next to it.

Speaker 2: Yeah.

Speaker 1: On the window side Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1: But not the window seat.

Speaker 2: Mm. (p. 664)

In example (38), there seems to be a clear motivation for the addition of information

coded in the NNRC which is aisle and next to it, since speaker 1 assumes that speaker

2 may not know what the abbreviations E and G mean and thus provides extra

information to help his/her listener to better understand the sentence.

The other two functional subtypes of NRRCs pertain to evaluation─the addition

of “the speaker’s attitude, opinion or stance toward the message of the immediately

preceding utterance(s)” (p. 662)─and affirmation─the addition of the speaker’s

confirmation of “an event or action referred to in the previous utterance” (p. 655).

Examples of these two subtypes are shown in (39) and (40), respectively:

(37) And I, it was really, I read the whole thing, which is pretty rare. (p. 663)

(38) I was asked if I would work as a co-auditor with them, which I did do. (p.

665)

Regardless of the fact that they serve not to track down a referent but to insert a

parenthetical assertion, NNRCs still function to ground a referent to some context in

order to make it relevant to the hearer at the juncture of the discourse where it is

mentioned. Their referential grounding can be either anaphoric, with definite head

NPs, or cataphoric, with referring-indefinite head NPs (Givon, 1993: 119), as shown

in (41) and (42), respectively:

(39) The woman, who was standing next to the door, pull a gun, and…

(40) A good friend of mine, whom I hope you’ll meet some day, just called and

said….

Parenthetical assertions by nature, English NRRCs are typically separated from

their matrix clauses by an intonational break (or commas11 in writing), and can

semantically be paraphrased with coordination or subordination (though there would

be a different focus) (Quirk et al., 1985:1258-1259), as illustrated in the following

sentences, where the NRRC in (43) has the semantic equivalents of the coordinate

11 It may be worth a mention in passing that in written English, the presence or absence of commas in RCs does not always signal a restrictive─non-restrictive distinction in semantic terms of sets and subsets. As remarked by Sopher (1999: 256), where context makes it clear whether an RC is restrictive or non-restrictive, or where there would be no marked differences in RC meanings, stylistic considerations may determine the use or nonuse of commas, as shown in (i), in which a comma would disrupt the rhythmic pattern of the sentence, though (i) is in effect non-restrictive:

(i) Where Lear, such a short while since, sat in his majesty, there sit the Fool and the outcast, with Kent whom he banished beside them.

Huddleston et al. (2003: 1064-65) point out, further, that the use or nonuse of commas in RCs sometimes has to do with information packaging, rather than with whether RCs give distinctive, contrastive properties of the class denoted. For example, in (ii):

(ii) The father who had planned my life to the point of my unsought arrival in Brighton took it for granted that in the last three weeks of his legal guardianship I would still do as he directed.

the RC is actually non-restrictive but no comma is present. This is so because the information coded in the RC is treated as an important and indispensable part of the message that explains why the father took it for granted that the son would do as he directed. The restrictive─non-restrictive distinction (i.e. the concept of subsets) is irrelevant here.

Though these two additional factors, stylistic considerations and information packaging, may govern the use or nonuse of commas in English RCs, they after all account for very marginal cases.

Therefore, the present study will limit itself to examining the use of commas in RCs in relation to the

clause in (44) and the adverbial clause in (45):

(41) My brother, who has lived in America since boyhood, can still speak fluent

Italian.

(42) My brother can still speak fluent Italian, and he has lived in America since

boyhood.

(43) My brother can still speak fluent Italian although he has lived in America

since boyhood.

2.1.2.3 Relative Clauses as a Backgrounding Device

Putting aside the aforementioned functional differences12 between RRCs as a

referent-tracking strategy and NRRCs as an information-adding interpolator, both

types of RCs (except for those presentative RRCs, which tend to foreground

important information) indeed have in common the discourse function of

backgrouding─they serve to add specificity or contextual information to assist in the

interpretation of the central ideas. According to Hopper and Thompson (1980:

280)13, information units in a discourse can broadly be classified into two types on the

12 For more detailed differences between English RRCs and NRRCs, refer to Huddleston et al. (2003:

1058-66). Basically, they recapitulate the differences in terms of the degree of integration of the RC into the matrix clause in prosody (or punctuation), syntax, and meaning. First, NRRCs are usually marked off from the rest of the sentence with a separate intonation contour and pause in prosody or with a comma in punctuation (or stronger punctuations, such as a dash or parenthesis), as is not the case with RRCs. Second, RRCs function as an essential part of a nominal group, i.e. combining with their head NPs to form larger NPs, whereas NRRCs are rather loosely incorporated into the main clause in that they themselves do not form constituents of any NPs. Last and foremost, the information of RRCs is presented as an integral part of the meaning of the sentence containing them (one information unit); that of NRRCs, in contrast, is felt to constitute another notional unit independent of the matrix clause (two information units).

13 Originally, they introduced the terms “foregrounding” and “backgrounding” to distinguish between

basis of information status or value they carry in relation to the main communicative

intent of the speaker:

That part of a discourse that does not immediately contribute to a speaker’s goal, but which merely assists, amplifies, or comments on it, is referred to as background. By contrast, that material which supplies the main points of the discourse is known as foreground…. The foregrounded portions together comprise the backbone or skeleton of the text, forming its basic structure; the backgrounded clauses put flesh on the skeleton, but are extraneous to its structural coherence.

More specifically, foreground information is more important, serving to push forward

the development of the central ideas that the speaker wants to express, whereas

background information is only secondary, serving to provide supportive, amplifying,

or evaluative material─or to borrow Goodin and Perklins’ (1982) term, “asides”─on

the ongoing discourse. With respect to their manifestations, such syntactic

embedding as relativazation has been considered one of the powerful means for

marking background information (Reinhart, 1984: 791; Matthiessen & Thompson,

1988: 279). Consider the following examples:

(44) The boy who stole Peter’s bicycle beat Mary.

(45) John, who stole Peter’s bicycle, beat Mary.

In both sentences, the main proposition is about the boy’s or John’s beating Mary,

most likely with the subsequent discourse continuing to develop or explicate this

event. The content coded in the RCs here is minor in information value in relation to

that in the main clauses. They merely provide background information about the

agent of the main event: one identifies the agent the boy, whereas the other elaborates

on the agent John. Were the main proposition about the boy’s or John’s stealing

Peter’s bicycle, the original sentences would be rewritten as (48) and (49),

respectively:

(46) The boy who beat Mary stole Peter’s bicycle.

(47) John, who beat Mary, stole Peter’s bicycle.

With this discourse function of backgrounding, English RCs, both restrictive and

non-restrictive, can serve to package information properly in proportion to its

communicative status or importance so that one can readily follow the flow of

information in the discourse.

2.1.3 Summary

In this section, we have discussed the syntactic and functional properties of

English RCs. Structurally, English RCs are complex adjectival clauses which

post-nominally modify an NP in the matrix clause, within which they are embedded;

they are anaphorically related to the main clause by means of relative markers, which

replace the relativized element in the embedded clause. Functionally, English RCs

are typically associated with backgrounding to maintain textual coherence, whether

they serve to track down a referent in question as either a known entity (identification)

or a particular type (characterization), i.e. RRCs, or to interpolate parenthetical

assertions considered useful to the hearer in a number of ways, i.e. NRRCs. With

these general descriptions of English RCs in mind, we proceed in the next section to

probe into those aspects of the RC construction which may cause difficulties for

ESL/EEL learners.

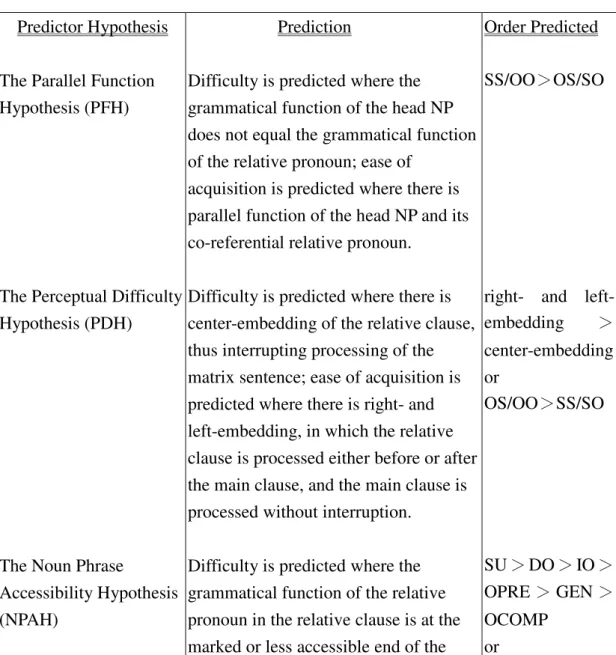

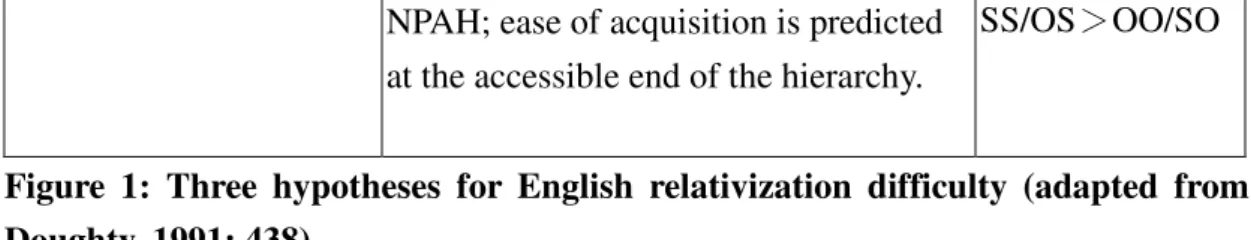

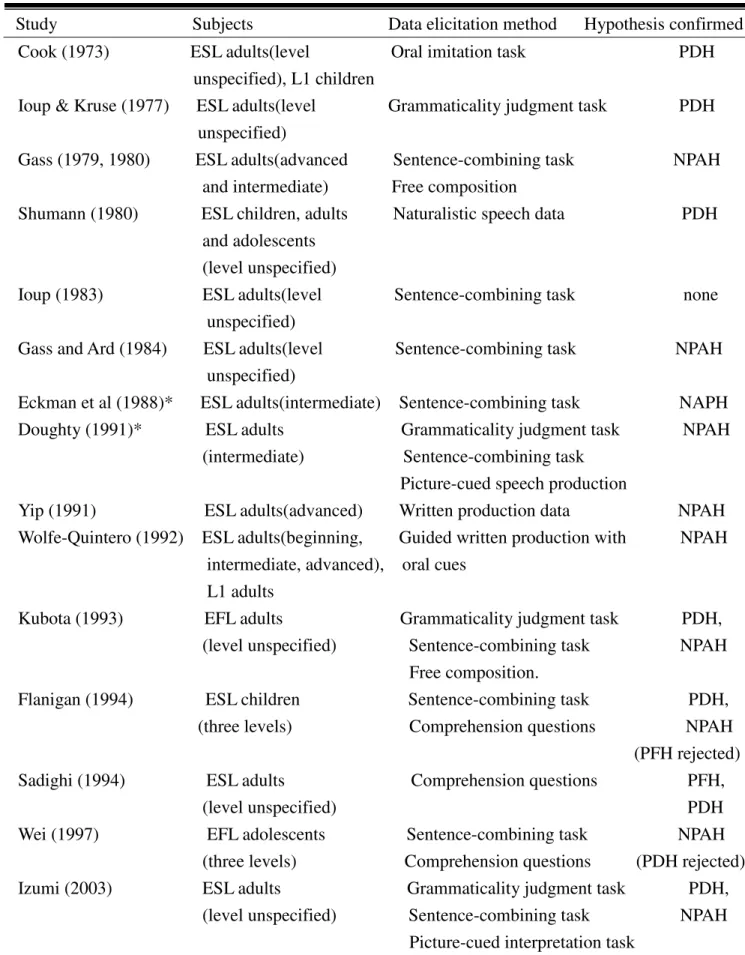

2.2 Variables in Acquisition of Relative Clauses by ESL/EFL Learners

This section concerns itself with previous empirical studies on how English RCs

are used by ESL/EFL learners. It begins with a survey of relevant RC research on

L1 interference, emanating from the framework of the Contrastive Analysis

Hypothesis. This is then followed by a review of RC studies intended to establish a

universal order of difficulty based on three predictor hypotheses: the Parallel Function

Hypothesis, the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis, and the Noun Phrase Accessibility

Hierarchy Hypothesis.

2.2.1 L1 Interference

Although the development of RCs has been investigated in various SLA contexts,

the case of Chinese learners of English is particularly of interest to researchers in that

English RCs are typologically different from their Chinese counterparts not only in

their syntactic manifestations but also in their pragmatic/discourse functions.

2.2.1.1 Differences Between English and Chinese Relative Clauses

According to Gass (1980), there are five main dimensions along which RC

formation varies among the world’s languages. The first dimension is adjacency to

the head NP. Although English and Chinese both require RCs to appear immediately

next to the head NP, extraposed RCs, namely, those placed at the end of the main

clause, are permissible only in English, especially for considerations of syntactic

complexity or for achieving a presentative function in discourse (Givon, 1993:

148-150), as is illustrated in (50) and (51), respectively:

(48) He bought a rug from his uncle’s estate that cost him a small fortune that he

couldn't really afford but went ahead and spent anyway.

(49) A spot was materializing that had pretty ominous look.

The second dimension has to do with the position of the RC with regard to the

head NP. English, a right-branching (or head-initial) language, requires RCs to

follow the head NP as post-nominal modifiers, whereas Chinese, a left-branching (or

head-final) one, forms RCs pre-nominally, i.e. to the left of the head NP. Such a

difference is clearly demonstrated in (52):

(50) mai hua de nei ge nuhai hen qiong sell flowers COM14 that CL15 girl very poor

‘The girl that sells flowers is very poor.’ (Cheng, 1995: 14)

The third dimension relates to how RCs are marked. English employs variable

relative markers, e.g. who(m), which, whose, that, to indicate what follows is an RC;

14 COM is the abbreviation for complementizer.

15 CL is the abbreviation for classifier.

Chinese instead uses only one invariable marker between the head NP and the RC,

namely, the complementizer16 de, which is not only used uniquely for RC marking

but also occurs in various structures of nominal modification in Chinese.

Fourthly, RC formation also differs in relative marker retention from language to

language. Unlike English relative markers, which are optional as long as they are in

the object position, the Chinese complementizer de is obligatory in all positions.

The last dimension involves the retention or omission of a pronominal reflex in

the process of relativization. The pronominal reflex refers to a resumptive pronoun

present in the RC that is co-referential with the head NP. English RCs disallow such

a resumptive pronoun. In contrast, pronominal reflexes are allowed in Chinese RCs,

depending on the position being relativized. Generally speaking, Chinese RCs tend

to adopt the gap method17 when relativizing out of the subject position, as in (52)

above, but the resumptive pronoun method when relativizing from such positions as

indirect object and prepositional object (Cheng, 1995), as shown in (53) and (54):

(51) zhangsan song ta hua de nei ge nuhai Zhangsan send her flowers COM that CL girl

‘the girl that Zhangsan sends flowers to her’ (p.18)

16 The syntactic status of de in Chinese RCs has long been debated. De is not a pronominal element, and thus cannot be treated as a relative pronoun like who(m), which in English. De has been thought of as either a nominalizer (Chan, 2004a) or a complementizer (Keenan, 1985). In order to make a direct comparison with English RCs, where that serves as a complementizer, de is treated in this paper as a complementizer in Chinese relative constructions.

17 The gap method is one of the universal relativization strategies employed in RC formation, in which there is one empty slot left in the embedded clause without any NP or resumptive pronoun found to

(52) zhangsan gen ta zhuzai yiqi de nei ge ren Zhangsan with he live together COM that CL person

‘the person that Zhangsan lives with him’ (p.18)

Another difference in RC formation across languages, not pointed out by Gass

above, is the permissibility of structural reduction of RCs (Li, 1996: 174). English

RCs can be reduced to participial phrases, prepositional phrases, adjectival phrases, or

to-infinitive phrases, while such reduction is disallowed in Chinese RCs, as can been

seen in (55):

(53) Eng.: visitors from London

Chi.: lunden lai de keren London come COM visitors ‘visitors who are from London’

Besides these structural differences, English RCs exhibit some

pragmatic/discourse functions not served by their Chinese counterparts. The most

obvious difference in function may be that the distinction between RRCs and NRRCs

in English does not exist in Chinese (Li, 1996). To put it another way, the primary

and sole function of Chinese RCs is to identify or characterize the head NP, specifying

which one or what type is meant by the speaker (i.e. restrictive); they do not serve to

supply parenthetical comments or afterthoughts (i.e. non-restrictive). Non-restrictive

RCs in English therefore have no RC correspondents in Chinese. For the same

function performed by English NRRCs, Chinese tends to use independent clauses

instead, as illustrated in (56):

(54) Eng.: The Browns, whose house has been burgled five times, never go on

holiday now.

Chi.: bulang jia zaiye bu qu du jia le Brown family again never go on holiday marker tamen de fanzi bei dao guo wu ci they GEN18 house be burgled tense five times

‘The Browns never go on holiday now. Their house has been burgled five times.’ (Li, 1996: 173)

According to Zhao (1989: 109, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992), who conducted a

discourse analysis of RCs in English and Chinese, besides those serving to provide

additional information, there is another type of English RCs which normally

correspond to independent clauses in Chinese. Different from their prototypical

functions of identifying or characterizing, this type of English RCs, she claims, serves

to focus information. Three instances of such information-focusing RCs in English

are identified in her study. The first instance is represented by (57):

(55) RCs as the main assertions for sentences low in information value:

Eng.: China is a country that is behind Canada in technology and a number of scientific disciplines.

Chi.: zhongguo zai jishu he yixie kexue xueke China in technology and some science discipline fangmian shi luohou yu jianada de

aspects is behind preposition Canada particle ‘China is behind Canada in technology and a number of scientific

disciplines.’

The English RC in (57) acts as the locus of information in the sentence and is often

rendered into Chinese as an independent clause by the “shi…de” construction (a kind

of nominalization), which is used to express and emphasize an established fact.

Another instance is given in (58):

(56) Extraposed RCs:

Eng.: A man came in who wore very funny clothes.

Chi.: jin lai le ge ren, ta chuanda hen qiguai come in tense one man he wear very funny

‘A man came in; he wore very funny clothes.’

Eng.: A girl is studying with me who has an IQ of 200.

Chi.: wo you ge nu tongxie, ta de zhishang wei 200 I have one girl classmate she GEN IQ is 200 ‘I have a female classmate; her IQ is 200.’

The two English RCs in (58) can only be translated into Chinese as independent

clauses serving as comments on their main clauses, which functions as topics. The

third instance of information-focusing RCs in English is seen in (59), in which the

equivalent structure in Chinese is an independent clause:

(57) RCs introduced by existential there:

Eng.: There were certain aspects of China which I was very interested in examining.

Chi.: wo dui zhongguo de mouxie wenti you xingqu I about China GEN some aspect have interest jinxing kaocha

carry out examining

‘I was very interested in examining certain aspects of China.’

It is noteworthy that the RCs in (57), (58) and (59) are all an extra predication

attached to a presentative clause. Apparently, what Zhao refers to as an

“information-focusing” RC is in effect a “presentative” RC, which serves to introduce

a thematically important, new referent into the discourse, as previously discussed in

Section 2.1.2.1.2.

2.2.1.2 Previous Empirical Studies on L1 Interference

In the light of these cross-linguistic discrepancies in RC structure and function,

one would not be surprised to find that considerable SLA research on English RCs has

been devoted to investigating the influence of L1 interference on EFL/ESL learners’

RC acquisition. These studies are in and of themselves the exponents of the

Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH), predominant in the field of SLA. The CAH

claims that the principal barrier to second language acquisition comes from

interference of an L2 learner’s mother tongue with a second language system being

acquired, especially when these two structurally differ to a great extent, and that a

systematic analysis between the two languages in question can yield a taxonomy of

linguistic contrasts which enables one to predict or explain difficulties an L2 learner

will encounter (Ellis, 1996: 23-27; Brown, 2000: 207-210). Emanating from such a

theoretical backdrop, many researchers (e.g. Schachter, 1974; Schachter et al., 1976;

Bley-Vroman & Houng, 1988, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992; Zhao, 1989, cited in

Kamimoto et al., 1992; Li, 1996; Wei, 1997; Gisborne, 2000; Yin, 2001; Chan, 2004a,

b) have strongly asserted that L1 transfer is the overriding and sole factor that

determines the success of RC acquisition by ESL/EFL learners. Their findings are

discussed in great detail below.

To begin with, Schachter et al. (1976) attested L1 influence on L2 learners’

inter-language by eliciting grammaticality judgments on English sentences containing

RCs from 100 high-intermediate and advanced ESL students of five language

backgrounds─Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Persian, and Spanish. In this task, the

subjects were presented with both native English RCs and malformed (non-native)

English RCs which corresponded to those RCs in the subjects’ L1. The results

indicated that although the subjects identified sentences with native RCs as

grammatical, they also tended to identify as grammatical sentences with their L1 form

of non-native RCs. For example, the Chinese group tended to identify as

grammatical those English RCs lacking relative pronouns in the subject position.

Schachter explains this phenomenon as the consequence of L1 transfer, citing the

non-occurrence of English relative pronouns in Chinese RCs.

Positive evidence of L1 interference is also provided by Wei’s 1997 study, in

which 131 Taiwanese EFL learners─roughly representing beginning, intermediate,

and advanced levels ─ were tested on English RCs in comprehension and

sentence-combining tasks. She found that contradictory to Flanigan’s findings (1994)

that the influence of L1 background was minimal on relativization, her subjects,

especially those of lower proficiency, were still occupied by their previous linguistic

repertoire, their RC errors indeed exhibiting L1 interference─including the use of

resumptive pronouns and lack of relative pronouns, both of which are typical of

Chinese RCs─ as well as resembling those errors commonly committed by native

speakers of English. Given the existence of negative L1 transfer, she suggests that

L2 learners acquiring English RCs cannot completely reset a new parameter value

(e.g. from head-final in Chinese to head-initial in English) without being influenced

by their L1.

Further landing support for L1 interference are Gisborne (2000), Yin (2001) and

Chan (2004a, b). Drawing on the Hong Kong database for the International Corpus

of English, Gisborne and Yin examined RC variation phenomena in Hong Kong

English (HKE) and identified some idiosyncratic features of RCs in HKE. Among

them, zero subject relatives (i.e. RCs lacking a relative pronoun in the subject position)

and blurring of the restrictive/non-restrictive contrast were claimed to be the

outcomes of Chinese’ influencing RC formation in HKE. In a similar vein, Chan

conducted a contrastive analysis of noun phrases in English and Chinese with 387

tertiary and secondary students of ESL in Hong Kong. Based on a corpus of

authentic data collected in a research project, she concluded that most English RC

errors committed by her subjects resulted largely from L1 transfer, such as

inappropriate relative pronouns (due to the absence of relative pronouns in Chinese),

missing relatives (due to the serial verb construction19 in Chinese), resumptive

19 The serial verb construction is typical of Chinese, referring to two or more verb phrases or clauses

pronouns, (due to this requirement in indirect and prepositional object RCs in

Chinese), and head-last RCs (especially among lower-proficiency learners, who tend

to adopt a word-for-word translation strategy), as illustrated in the following:

(58) *She is my mother which is the most important person in my life.

(59) *You are the first person came to Hong Kong.

(60) *There is one thing which I can remember it very clearly.

(61) *I wear the dress is very cute.

L1 interference manifests itself not only in L2 learners’ knee-jerk error making,

as revealed by the aforesaid studies, but also in their behavior of avoidance.

Kleinmann (1977) has argued for avoidance of a given structure as indicating areas of

difficulty, predictable on the basis of a contrastive analysis of the target and native

languages. In her classic paper on this issue, Schachter (1974) examined English

free compositions written by both native Americans and 50 intermediate and

advanced ESL learners, whose L1s were Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, and Persian (no

detail given for how this task was administered). She found that while the Arabic

and Persian learners produced as many RCs as their native American counterparts, the

Chinese and Japanese learners produced far fewer, though obtaining a significantly

lower error rate than the former two language groups. Schachter attributes this

avoidance phenomenon or strategy to L1 interference: because the structural

differences between Chinese/Japanese (head-final) and English RCs are greater than

those between Arabic/Persian (head-initial) and English RCs, it would be more

difficult for Chinese and Japanese learners to acquire English RCs, and the increased

learning difficulty would in turn lead to their tendency to avoid using English RCs in

their writing, especially when they feel unsure of getting the target structure right.

Based on the premise that L1 interference operates on the discourse as well as

the syntactic levels, other researchers, such as Bley-Vroman and Houng (1988, cited

in Kamimoto et al., 1992), Zhao (1989, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992) and Li (1996),

have attempted to put forward alternative explanations for the underproduction of

English RCs by the Chinese subjects in Schachter’s (1974) study. They all contend

that the low frequency rate of RCs in the English of Chinese learners results not so

much from structural interference of L1 with L2 as from pragmatic transfer of the RC

frequency, distribution, and function patterns in L1 to L2─namely, L2 learners may

know the grammatical structure of RCs, but may not know when to use it in English.

To challenge Schachter’s (1974) purely structural view of RCs, Bley-Vroman

and Houng (1988, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992) set out to examine relative

frequencies of English and Chinese RCs by comparing the first five chapters of the

American literary work The Great Catsby and its published Chinese translation.

They found that only one-third (32/93) of the original English RCs were translated

into the Chinese version, as shown in Table 2:

Table 2: Frequency of RCs in the first five chapters of The Great Catsby and the number of those clauses translated as RCs in the Chinese version (adapted from Bley-Vroman & Houng, 1988: 96, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992)

RC types in The Great Catsby Rendered as RCs in English Chinese translation*

Restrictive 50 21 (42%) Non-restrictive 43 11 (25%) Total 93 32 (34%)

*Figures in this column indicate only the number of English RCs of both types rendered as RCs rather than other structures in Chinese. There is no formal distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive RCs in Chinese.

Based on this lower RC density in Chinese, Bley-Vroman and Houng reason that

Chinese learners are likely to under-produce RCs in their English, inasmuch as they

do not use RCs frequently in their own native language and may transfer the

preference for non-relative structures (e.g. independent clauses or adverbial clauses)

in Chinese over to English for contexts in which RCs are normally used to achieve the

same communicative purposes.

By examining both English writings on impressions of China by Chinese

Americans and Canadians and their Chinese translations, Zhao (1989, cited in

Kamimoto et al., 1992) also concludes that Chinese indeed makes less use of RCs

than does English, as indicated in Table 3:

Table 3: RCs in English text and their Chinese translation (adapted from Zhao, 1989: 107, cited in Kamimoto et al., 1992)

RCs in English RCs in Chinese RCs in English in English in Chinese =RCs in Chinese only only 124 91 59 (48%) 65 32

More importantly, her study revealed that there are two types of English RCs which

have no RC equivalents in Chinese due to their special functions not performed by

Chinese RCs, namely, adding parenthetical assertions and focusing information (e.g.

presentative RCs with extraposition or existential there), as previously noted in

Section 2.2.1.1. Such functional differences between English and Chinese RCs,

Zhao claims, not only provide hard counterevidence for the implicit anglocentric view

in Schachter’s (1974) study that the way RCs function in English also holds true for

those in other languages, but also offer explanations for the relatively low production

rate of English RCs by her Chinese subjects: the subjects may have transferred the

limited range of RC functions in Chinese to English, thereby employing RCs merely

for identification or characterization in their English writing.

Further refining Schachter’s (1974) avoidance theory, Li (1996) propounds a

differentiation between conscious avoidance, as portrayed by Schachter, and

subconscious underproduction, a situation where a learner under-produces a certain

structure mainly because he/she lacks a full understanding of the common contexts for

using it (i.e. he/she may not be aware of all the functions it can serve). Li’s study

involved 11 Chinese ESL learners of Hong Kong (intermediate and advanced) in

definition questions (e.g. What is a clock?), Chinese-to-English translations (some of

which were adapted from Zhao’s examples of English RCs with special

pragmatic/discourse functions not served by Chinese RCs), and individual

retrospection interviews. In line with Schachter’s findings, her Chinese subjects

were indeed observed to employ RCs with low frequency. Nonetheless, in their

individual interviews, most of her subjects denied having deliberately tried to avoid

using English RCs because of the perceived gross structural differences between

English and Chinese RCs. Moreover, her subjects were quite successful in

producing all the English RCs in the translation test, except for those that served to

add parenthetical information or to focus information (i.e. to present a topical

referent). Based on the results, Li contends that Chinese learners’ sporadic use of

RCs in their English writing may be explicable in terms of their failure to discern the

subtle pragmatic differences between English and Chinese in RC function. That is,

under the influence of L1 transfer, Chinese learners often use English RCs as a pure

noun modifier, as they do with Chinese RCs, and tend to lose sight of the additional

functions RCs can serve in English; as a result, they subconsciously produce fewer

RCs in their English writing.

It is worth pointing out that the foregoing RC studies on L1 interference may be

tainted by two weaknesses in their research methodology. One weakness concerns

the nature of elicitation tasks. Most of the studies above employed elicitation tasks

that imposed a high degree of control over L2 learners’ output production, including

grammaticality judgments, comprehension questions, sentence-combining, and

translation. As a result, learners’ true competence in the target structure may not

have been shown. The translation task, in particular, is more problematic in that the

extent of L1 interference may have been aggravated by directly inviting the use of L1

in producing English RCs. Moreover, even though free writing, a more spontaneous

task, was adopted by Schachter (1974), the task suffers from lack of control as well as

lack of methodological detail in the data collection procedure (i.e. how she collected

her writing samples is left unknown). Her use of this unconstrained elicitation

format certainly begs the question as regards whether her subjects may have truly

been forced to reveal facets of their inter-language under investigation (Corder, 1973).

This is so because Schachter gave little consideration for the nature and topic of her

writing task (no detail given for what topic was chosen), not placing limitations on her

subjects (e.g. requiring them to follow specific instructions or pictorial prompts) that

would prompt the use of English RCs in their compositions.

The other weakness relates to the failure to consider the effect of L1 interference

observed in relation to L2 proficiency. In these previous studies, with the exception

of Wei (1997), little is said about the role of L2 proficiency in their subsequent data

analysis. Instead, they tend to make a general conclusion without making allowance

for the very fact that L2 proficiency may well play a part in intervening and