The Self-perceptions of Inservice and Preservice

Kindergarten Teachers in Kaohsiung and

Pingtung Regions Concerning the Usefulness of

the Music Content of Their Teacher Training

Programs

Yi-Yuan Chen*

Abstract

This study (1) ascertained the perceived effectiveness of preservice and inservice training of kindergarten teachers in music education at Pingtung Teachers College with regard to their competencies, and (2) determined the differences between the perceptions of 110 preservice and 129 inservice teachers from two selected areas of Taiwan about necessary competencies for music teaching, as well as examined their expectations of their preservice and inservice music training.

The research questions addressed: (1) the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education preservice teachers for music teaching; (2) the

self-perceived preparatory needs of ECE inservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching, and (3) significant differences between the self-perceived needs of preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching.

The data were gathered using a questionnaire called The Self-Perceptions of Kindergarten Teachers Regarding Necessary Music Competencies (PKTNMC). Descriptive statistical analysis was used to compute frequency, percents, means, and a t-test.

There were five conclusions: (1) Teachers colleges should provide practical and accessible music curricula applicable to the kindergarten classroom so that inservice and preservice teachers are well prepared to meet the growing need for music education in kindergarten; (2) all inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers in this study agreed that all the competencies listed in the questionnaire were at least somewhat useful; (3) teachers colleges should provide more conferences or training programs to help kindergarten teachers learn a variety of competencies; (4) the teacher preparation program is valuable for providing kindergarten teachers with the music and music-teaching competencies they need, and (5) kindergarten

administrators and school districts should support and encourage inservice teachers to attend workshops and training programs to enhance their teaching abilities, especially with teaching skills that have been effective for their students.

The recommendations from this study include: (1) actual plans for publishing a new music curriculum, integrated with other arts, in Taiwan, that incorporates music and music-teaching competencies; (2) repeating the survey three years consecutively to investigate fluctuations; (3) conducting the same study nationally; (4) extending the study to other subjects; and (5) determining how inservice teachersí backgrounds affect their responses to the questionnaire.

INTRODUCTION

The effectiveness of teacher preparation for early childhood music instruction has long been a concern of music educators in Taiwan. Although teacher training programs and preschool curricula have been much improved in the past 40 years (Tzai & Line, 1987; Wu, 1999), a number of kindergarten teachers find that there is an enormous difference between preparation and practice in the teaching of music (Housewright, 1972). Because most kindergarten teachers have graduated from Teachers Colleges, those colleges play an important role in the training of early childhood educators. Thus, the music instruction offered in the Teachers Colleges should be based on what is necessary for actual practice in kindergarten classrooms.

The purposes of this study were: (a) to ascertain the perceived effectiveness of the preservice and inservice training of kindergarten teachers in music education at Pingtung Teachers College with regard to their competencies, and (b) to determine differences in the perceptions of preservice and inservice teachers in two selected areas of Taiwan concerning the necessary competencies for music teaching. The study examined the expectations of 129 inservice and 110 preservice kindergarten teachers concerning their preservice music courses and their need to gain specific music competencies through inservice training.

Prior researches (e.g., Bloom 1964; Gardner, 1983; McDonald & Simons, 1989; Scott, 1989; Suzuki, 1983) indicate that young children are ripe for learning. Bloom (1964) emphasized that "80 percent of a child's intellectual growth occurs between conception and age eight” (p. 8). During that sensitive period, children have a natural curiosity and love for learning. It is important that in this sensitive period the full development of the child be considered, not only the intellectual, but the

psychological and the emotional development as well (Wu, 1999). Romanek (1971) stated that early experiences have a profound effect on children’s cognitive

accumulating evidence from both psychology and anthropology that musical experiences are an excellent vehicle for early learning" (p. 19). According to the research, most educators agree that a child's early music experiences will have a lifelong effect and that kindergarten is an important period for learning. They also agree that music is one of various important activities for children. Kindergarten teachers play an important role in influencing children's enjoyment of music (Sims, 1994). Music educators, parents, and administrators are concerned about teacher quality, as well as teaching curriculum and conditions.

Teachers Colleges have, for some time, been offering different music content for preservice kindergarten teachers, and inservice kindergarten teachers have been concentrating on improving their teaching, providing valuable music experiences, and developing a positive attitude toward music teaching (Wu, 1999). The content of the music courses offered in the Teachers Colleges, such as fundamentals of music, keyboard skills, children’s song accompaniment, music teaching methods and materials for children, moving to music, simple instruments for children, rhythm for children, research for children’s music education, music appreciation, Chinese children’s music, and story and chant allow students to acquire general pedagogical skills, as well as develop understanding and competency in a variety of knowledge domains.

Considering these developments, several question arise: Why are the

kindergarten music activities offered in some classrooms outstanding while those in others are mediocre or even non-existent? Why do some kindergarten teachers provide successful music instruction to their classes while others do not? What is the relationship between the knowledge and skills taught in the Teachers Colleges and the perceptions of kindergarten teachers concerning music teaching competencies?

Research has shown that kindergarten teachers play an important role in

kindergarten teachers need? What difference is there in the expectations of

preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers concerning their competency to teach music to their young students?

The research questions for the study were the following:

1. What are the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education preservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching?

2. What are the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education inservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching?

3. Are there significant differences between the self-perceived needs of preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching?

In sum, this study was designed to examine kindergarten music teachers’ perceptions of their own competency levels. It also determined whether or not teachers with inservice training had different perceptions about music teaching competency and music teaching preparation from those with preservice training.

Definition of Terms

The following definitions are included in order to clarify the terminology used most frequently in the study:

Music Teaching

A major research concern is the quality of the music instruction provided by kindergarten teachers. The term “music teaching” refers to any musical activity or experience provided by the kindergarten teacher in which the students are given instruction in the elements of music or its characteristics or qualities, e.g., chanting, singing, play-moving, listening, and creating (Goodman, 1985).

Competency

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

This review of the literature about preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers’ perceived needs for music teaching addresses the following topics: (a) kindergarten teachers’ music competencies, and (b) teachers’ preparation for teaching music in kindergarten. Each is addressed below.Kindergarten Teachers’ Music Competencies

The level of competency of the teacher greatly affects the value of a musical activity for the child. Teachout (1997) conducted research concerning preservice and experienced teachers’ opinions of the skills and behaviors that are important to successful music teaching. He points out that because most undergraduate music major students enter college with little or no experience in teaching music, many are unaware of the skills needed to be a successful teacher. Experienced teachers, however, have learned these skills and have developed and refined them throughout their years of teaching. Therefore, it would make sense for universities to provide teacher training programs that involve undergraduate students working with

experienced teachers. These competencies are all important to being a successful teacher. The aim of this study was to compare the responses of preservice student teachers and experienced teachers to the question of which skills and behaviors are important to successful music teaching in the first three years. The subjects were 125 preservice and 105 experienced teachers.

talent as being more important than did experienced teachers. In Teachout’s finding, it also indicated that some teaching skills and behaviors were ranked higher by

experienced music teachers than by preservice music teachers. Because of their teaching experiences, experienced music teachers consider some skills and behaviors more crucial for initial success than do preservice teachers.

In Soderblom’s study (1982), the following competencies were considered, by first-year teachers, experienced teachers, and college instructors, to be essential to the success of first-year elementary school general music teachers: conducting, singing, ancillary instruments, and lesson planning. Instructional planning was also viewed as very important by three-quarters of respondents. The findings indicated that there were some music and music-teaching competencies considered by all respondents to be essential to the success of first-year elementary school general music teachers.

In addition, Baker and Saunders (1991) stated in their study that inservice kindergarten teachers considered the ability to develop movement activities, the ability to lead and teach songs, and piano-playing skills as useful in their teaching.

Wenerd (1989) listed six popular musical experiences offered in American kindergartens: singing, movement, listening, instrumental activity, improvisation of melodies, and sound exploration. Similarly, in Morin’s study (1994), the result showed that singing, listening, playing instruments, and moving were four primary modes of musical learning.

toward their teaching situations.

Goodman (1985) assessed the perceived music and music-teaching competencies of classroom teachers from three different types of school district: city, county, and exempted village. He ascertained the perceived effectiveness of preservice training in music and music education in college. The findings were the following: (a) teachers perceived the competencies acquired from their undergraduate preparation to be somewhat effective in providing music instruction in the classroom, (b)

perceptions were affected by private music lessons more than anything else, and (c) undergraduate music courses did affect teachers’ perceptions of their own

competence.

Teachers’ Preparation for Teaching Music in Kindergarten

Musical experiences in preschool and kindergarten affect children for the rest of their lives. Therefore, more child care centers need to provide children with musical experiences, and these activities need to be taught by a teacher trained in music activities. For this purpose, more inservice training is needed. Summer programs in the arts, for example, have been shown to increase teachers’ confidence in their abilities. Self-confidence is crucial to high-quality teaching, since teachers’ educational principles are formed both by their beliefs about learning and by their images of themselves as teachers. Many teachers have not received any instruction in some of the areas that they teach children, and many of the skills that they do learn do not prove to be useful to them, which keeps their confidence and their competence lower than it should be.

A study conducted by Boyle and Thompson (1976) assessed the efficacy of the Penn State University Arts Term and Encounters In The Arts programs for improving teacher self-confidence, which is necessary for high quality instruction. The

significant positive shifts on the posttest. The posttest showed a large shift, showing that confidence in this area was greatly increased. The general conclusion of this research is that these Penn State summer experiences do increase participants' confidence in their own abilities in the arts.

Kinder (1988) found that five types of teacher preparation were rated most important by classroom teachers: demonstrations of how to teach action songs, demonstrations of the organization of musical activities around a holiday, observing music being taught by a specialist, learning to use rhythm and melody instruments, and learning to sing.

Researchers have also examined the qualities that make a good music teacher. Many researchers (Birch, 1969; Bresler, 1994; Goodman, 1985) have agreed that music teachers who had musical experiences prior to entering university to study music were better prepared to teach music. The level of the teacher’s prior

involvement with music and the grade the teacher teaches have also been studied by researchers.

More research is needed to determine what the most effective kinds of music experiences might be for music teachers in training. In Morin (1995) study, 250 final-year music education students from the University of Manitoba sought to reveal the kinds of music experience that positively influence a music teacher's effectiveness in the classroom. Nine two-hour workshops were held. The topics of the

workshops were the following: music resources for the classroom; correlating music with other subjects; activities with classroom instruments; singing with children; music materials for holidays; activities for music listening and movement; planning music instruction; and multicultural music education. During the first class, students completed the Self-Perception Music Inventory. This test was given again at the end of the workshops. The differences between the two tests were evaluated. Results revealed a minimal change in attitude about music. This may be largely due to the fact that students revealed in the pre-test that they enjoyed music already. However, the course did increase students’ confidence in teaching music to children.

in order to provide children in preschool and kindergarten with the musical experiences that are so crucial to their development. More research is needed to determine what kinds of programs are more effective for teachers in training, although some, such as summer programs in the arts have already been shown to give teachers the self-confidence they sometimes lack. Teacher confidence and competence are kept at a low level by a lack of instruction in some of the areas that they teach.

METHODOLOGY

Quantitative research methods were used in this study, representing descriptive correctional research. According to Borg and Gall (1989), the questionnaire format is commonly used in educational survey research. The data, therefore, were

gathered using a questionnaire entitled The Self-perceptions of Kindergarten Teachers Regarding Necessary Music Competencies (PKTNMC), which was designed by the investigator specifically for this study. This study examined the expectations of 129 inservice and 110 preservice kindergarten teachers concerning their preparatory music courses and their need to gain specific music competencies through college training.

The pilot study suggested necessary revisions, including rewording of

instructions, elimination of difficult sections, and adjustment of the time necessary for participant completion. The main study determined the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education preservice and inservice teachers for music teaching.

Of the 139 questionnaires originally distributed to the inservice teachers for the study, 129 were completed and returned. Thus, the response rate was 92.8%.

Information about these teachers includes (a) age, (b) years of teaching, (c) age taught, (d) status of the kindergarten program, (e) teachers’ educational levels and academic degrees, (f) music courses taken, and (g) music inservice conferences attended.

In sum, 35% of the teachers were under the age of 31 while 64% were above the age of 30. Forty-two percent of the participants were teaching 5 year olds. Almost 50% of the teachers had teaching experience between 1 and 10 years, and another 50% between 11 and 25 years. Seventy-eight percent of the participants were from private kindergartens, while 21% were from public kindergartens. Eighty-one percent of the inservice teachers had graduated from junior colleges, and 65% of all the teachers had attended an ECE program. Eighty-five percent of the teachers had taken music course(s) before they got into college. For example, 78.3% had learned piano; 19.4% had taken singing lessons, and 47.3% had taken a music teaching methods course. Additionally, 72.9% of inservice teachers had experience with music conference(s).

A total of 115 questionnaires were distributed to the preservice teachers, of which 110 consent forms and questionnaires were returned. Their response rate was 95.7%. Information about the participants provided on the questionnaire to

determine the personal background of the participants includes (a) college class standing, (b) music courses taken, (c) piano, and (d) singing.

Just 50% of preservice teachers were juniors or seniors respectively. Forty percent of preservice teachers had taken a music course. Thirty-three participants had taken piano and only one participant had taken singing lessons.

Instrumentation for Pilot and Main Study

The investigator designed a questionnaire as a research instrument for this study. This questionnaire, entitled The Self-perceptions of Kindergarten Teachers Regarding Necessary Music Competencies (PKTNMC), combines open-ended and Likert-type scale questions. The participating inservice kindergarten teachers were asked to respond based on their actual teaching experience, rather than on what they believed to be ideal, whereas preservice teachers were asked to respond based on their

The questionnaire consists of two sections. The first section contains seven questions requesting the participant’s personal background, such as age, teaching experience, age-group taught, employment at a public or private kindergarten, educational levels and degrees, and attendance at music conferences. The second section contains 46 questions involving music and music teaching competencies. These questions were rated on a Likert-type scale to measure the self-perceived useful music competencies of the teachers. Only the first section, about the participant’s background, is different. The specific content of the survey items reflects the previous work of Baker, 1981; Baker & Saunders, 1991; Blackburn, Coop, & Stegall, 1978; Goodman, 1985; Montgomery, 1995; Sefzik, 1983; Smith, 1985; and Wu, 1999.

Data Collection

Data collection included two parts, the pilot study and the main study. These studies had several phases, as follows.

Pilot Study

The investigator conducted a pilot study prior to the main study to assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. The pilot study, which took place in September 1999. The investigator determined, by means of this pilot study, how comprehensible the questionnaire items were to the participants, and refined the questionnaire for the main study by using the suggestions from the results of the pilot study.

The investigator analyzed these data after the questionnaires were returned. The participants in the pilot study were willing to help the investigator refine the instrument. Therefore, suggestions for modifying the questionnaire were collected from the participants. The suggestions made by the inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers and by the professors were determined and some items

modified, for example, questions 2 in Part One of questionnaire of preservice teacher, and 16, 17, 18, 19, 24, 31, 35, and 45 in Part Two. The major changes made were the following: (a) type of kindergarten district, (b) music courses taken, (c) questions asked more appropriately (no.35 in part two), (d) fundamental music eliminated (no.2 in part one), (e) redundant question eliminated (no.31, 45 in part two), (f) piano changed to keyboard (no.16-19 in part two), and (g) question number 24 modified to include movement instead of harmony, form, and timbre.

Main Study

The main study was conducted between October 15 and November 15, 1999. . The 139 inservice kindergarten teachers were studying at the Institute of Inservice Teacher Training at Pingtung Teachers College. The individuals included in the sample were inservice kindergarten teachers, either full-time or part-time, in the Kaohsiung or Pingtung regions. The investigator received permission from the director of the Institute of Inservice Teacher Training to administer the questionnaire. Then, 115 additional participants, all kindergarten preservice teachers, were chosen from the junior and senior classes in the Early Childhood Education Department at Pingtung Teachers College with the department’s permission.

Data Analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. The whole database for the questionnaire was loaded into the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Graduate Pack for Window Release 7.0 (Norusis, 1995). The investigator used the Cronbach alpha coefficient (Anastasi, 1982) to determine the internal consistency of the instrument and assess its reliability. Responses to the questionnaire were based on a forced-choice, Likert-type scale, ranging from “not useful” to “very useful.” The investigator determined the means, standard deviations, and t-test, and reported the necessary reliability coefficients. The

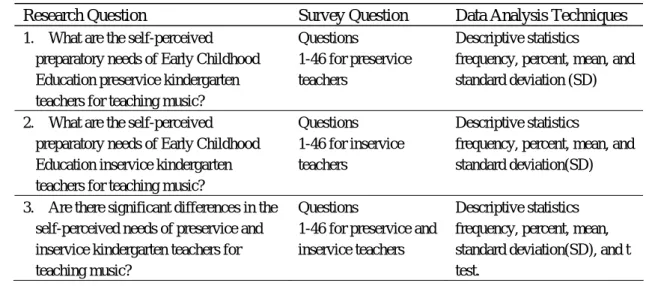

Cronbach alpha value on music competencies of questionnaire responded by inservice teachers was 0.95, and on music-teaching competencies was 0.92. On the other hand, the Cronbach alpha value on music competencies of questionnaire responded by preservice teachers was 0.94, and on music-teaching competencies was 0.96. The data-analysis procedures used for the research questions are summarized in Table 1. Table 1. Data Analysis Procedures

Research Question Survey Question Data Analysis Techniques

1. What are the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education preservice kindergarten teachers for teaching music?

Questions 1-46 for preservice teachers

Descriptive statistics

frequency, percent, mean, and standard deviation (SD) 2. What are the self-perceived

preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education inservice kindergarten teachers for teaching music?

Questions 1-46 for inservice teachers

Descriptive statistics

frequency, percent, mean, and standard deviation(SD) 3. Are there significant differences in the

self-perceived needs of preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers for teaching music?

Questions

1-46 for preservice and inservice teachers

Descriptive statistics frequency, percent, mean, standard deviation(SD), and t test.

Each question, with data analysis, is indicated in the following sections. Research Question 1

What are the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education preservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching?

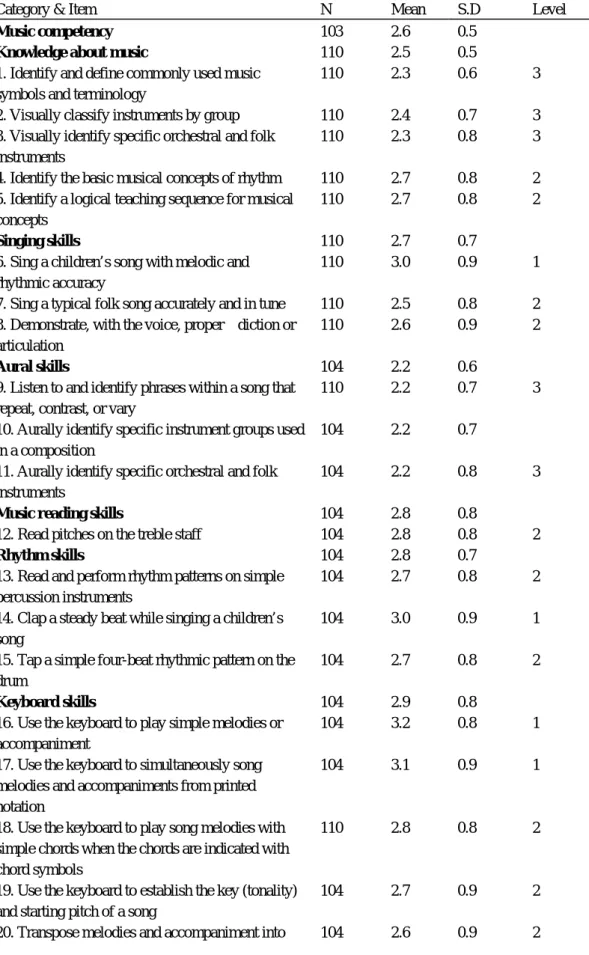

The PKTNMC questionnaire includes 46 questions with a total of 48 items. These are divided into two groups: music competencies and music teaching competencies. Each group is made up of 24 items. The means for the 48 items have been divided into three levels of usefulness by the investigator, based on her professional experience and judgment. These three levels of usefulness are as follows: (a) level-one 3.0-3.5, very useful, (b) level-two 2.50-2.99, useful, and (c) level-three 2-2.49, somewhat useful. The greater the value of the mean, the more important is that competency for teaching kindergarten music classes.

The following eight categories were grouped under music competencies: (a) knowledge about music, (b) singing skills, (c) aural skills, (d) music reading skills, (e) rhythm skills, (f) keyboard skills, (g) ability to play instruments, and (h)

improvisation / composition skills. There were four possible ratings for each question in a Likert-type scale: (a) not useful, (b) somewhat useful, (c) rather useful, and (d) very useful. Table 2 indicates the mean for each of the 24 items considered by preservice kindergarten teachers, based on their expectations and ideals regarding music competencies. The mean for all the items was between 2.2 and 3.2; in other words, all music competency items included were seen by the preservice teachers as being necessary for kindergarten teaching (see Table 2).

Table 2 also shows the music competency questions whose means are at level one (3.0-3.5), meaning that they are very useful for teaching kindergarten music classes. The highest mean was 3.2 for “ability to use the keyboard to play simple melodies or accompaniment.” The “ability to use the keyboard to simultaneously play song melodies and accompaniments from printed notation” had the second highest mean (3.1). These two abilities, therefore, are considered by these

Table 2. Means for Music Competencies of Preservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category & Item N Mean S.D Level Music competency 103 2.6 0.5 Knowledge about music 110 2.5 0.5 1. Identify and define commonly used music

symbols and terminology

110 2.3 0.6 3 2. Visually classify instruments by group 110 2.4 0.7 3 3. Visually identify specific orchestral and folk

instruments

110 2.3 0.8 3 4. Identify the basic musical concepts of rhythm 110 2.7 0.8 2 5. Identify a logical teaching sequence for musical

concepts

110 2.7 0.8 2 Singing skills 110 2.7 0.7 6. Sing a children’s song with melodic and

rhythmic accuracy

110 3.0 0.9 1 7. Sing a typical folk song accurately and in tune 110 2.5 0.8 2 8. Demonstrate, with the voice, proper diction or

articulation

110 2.6 0.9 2

Aural skills 104 2.2 0.6

9. Listen to and identify phrases within a song that repeat, contrast, or vary

110 2.2 0.7 3 10. Aurally identify specific instrument groups used

in a composition

104 2.2 0.7 11. Aurally identify specific orchestral and folk

instruments

104 2.2 0.8 3 Music reading skills 104 2.8 0.8 12. Read pitches on the treble staff 104 2.8 0.8 2 Rhythm skills 104 2.8 0.7 13. Read and perform rhythm patterns on simple

percussion instruments

104 2.7 0.8 2 14. Clap a steady beat while singing a children’s

song

104 3.0 0.9 1 15. Tap a simple four-beat rhythmic pattern on the

drum

104 2.7 0.8 2 Keyboard skills 104 2.9 0.8 16. Use the keyboard to play simple melodies or

accompaniment

104 3.2 0.8 1 17. Use the keyboard to simultaneously song

melodies and accompaniments from printed notation

104 3.1 0.9 1

18. Use the keyboard to play song melodies with simple chords when the chords are indicated with chord symbols

110 2.8 0.8 2

19. Use the keyboard to establish the key (tonality) and starting pitch of a song

other keys at the keyboard

Playing instruments skills 104 2.6 0.9 21. Play a variety of children’s percussion

instruments

104 2.6 0.9 2 Improvisation / composition skills 106 2.7 0.7 42. Respond to music through physical

movement, demonstrating an awareness of the expressive possibilities of rhythmic, melodic, and formal organization.

106 3.0 0.8 1

43. Create and notate rhythm compositions in various meters

106 2.5 0.9 2 44. Devise rhythmic accompaniment which can be

played on simple percussion instruments

106 2.8 0.8 2

1=useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = rather useful, 4 = very useful) (Missing = No response)

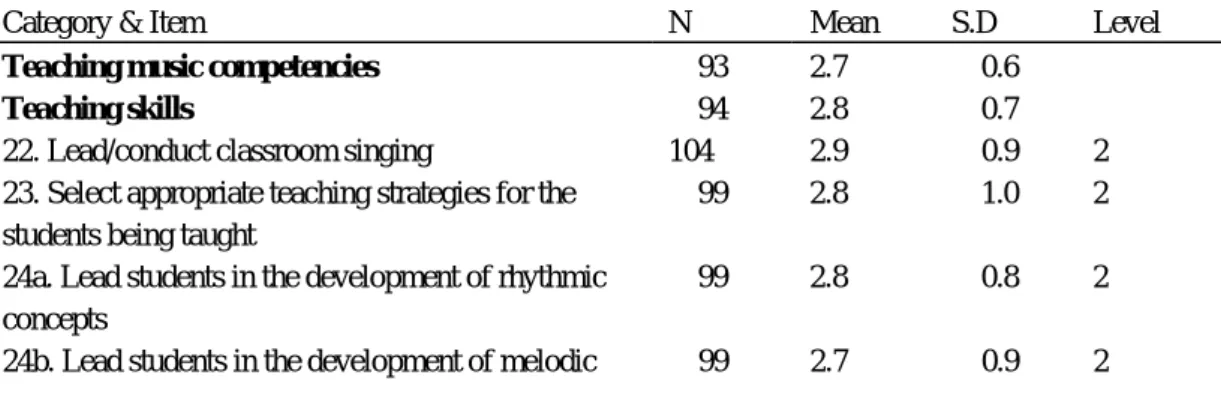

Table 3 reports the means of five categories with 24 items regarding the music-teaching competencies, scaled by preservice kindergarten teachers. The “music-teaching competencies” is divided into five categories: (a) teaching skills, (b) familiarity with music repertoire, (c) activity planning skills, (d) professional teaching competencies, and (e) assessment skills. The means for the 24 items are all between 2.5 and 3.1, which would also make them necessary competencies (see Table 3). That the “ability to exhibit enthusiasm for teaching and caring for the students” and the “ability to develop within the students observable enjoyment / interest / enthusiasm in music and music participation” are regarded by the preservice kindergarten teachers surveyed as two of the most important abilities to apply in their future kindergarten music teaching (see Table 3).

Table 3. Means for Music-Teaching Competencies for Preservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category & Item N Mean S.D Level Teaching music competencies 93 2.7 0.6

Teaching skills 94 2.8 0.7 22. Lead/conduct classroom singing 104 2.9 0.9 2 23. Select appropriate teaching strategies for the

students being taught

99 2.8 1.0 2 24a. Lead students in the development of rhythmic

concepts

concepts

24c. Lead students in the development of movement concepts

99 3.0 0.8 1 Familiarity with music repertoire 98 2.6 0.8 25. Select appropriate singing and listening materials

for the age and musical development level of the child

98 2.7 0.9 2

26. Select musical examples that illustrate specific music concepts

98 2.5 0.9 2 27. Identify a variety of materials and techniques to

help the beginning singer learn to match pitch

98 2.6 0.9 2 28. Develop appropriate children’s songs for

kindergartners

98 2.5 0.9 2 Activity planning skills 99 2.8 0.7 29. Develop appropriate singing games for

kindergartners

99 3.0 0.9 1 30. Select appropriate music for listening lessons 99 2.7 0.9 2 31. Organize sequences and implement learning

experiences that encourage musical growth through the development of listening, performing, and creative skills.

99 3.0 0.9 1

32. Plan individual lessons dealing with specific skill and concept areas

99 2.8 0.9 2 33. Sequence a series of music lessons leading to the

attainment of stated program goals and objectives

99 2.6 0.9 2 34. Establish long-term goals and objectives for the

music curriculum that are appropriate for the age and musical development level of the child

99 2.5 0.9 2

Professional teaching competencies 106 2.8 0.7 35. Provide a creative, interesting, well-paced

presentation involving a breadth of activities.

106 2.9 0.9 2 36. Exhibit enthusiasm for teaching and caring for

students

106 3.1 0.8 1 37. Develop within students observable enjoyment /

interest / enthusiasm for music and music participation

106 3.1 0.9 1

38. Communicate and receive the respect of students while maintaining strong and fair discipline

106 2.5 0.9 2 39. Integrate music with other subjects 106 2.8 0.8 2 40. Use positive group management techniques 106 2.7 0.8 2 41. Identify potential community resources that may

enhance musical learning

106 2.6 0.9 2 Assessment skills 107 2.6 0.8 45. Detect melodic and rhythmic errors in children’s

singing

(1 = not useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = rather useful, 4 = very useful) (Missing = No response)

Research Question 2

What are the self-perceived preparatory needs of Early Childhood Education inservice kindergarten teachers for music teaching?

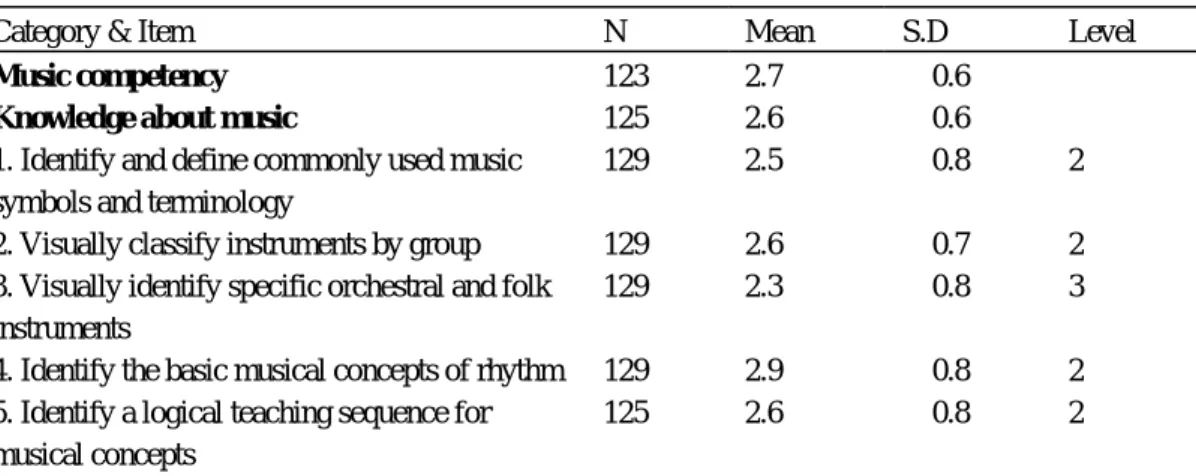

The PKTNMC questionnaire was approached by inservice kindergarten teachers from the standpoint of their actual teaching experience rather than from what they believed to be ideal. Just as the means of preservice teachers were divided into three different levels, the means of inservice teachers were divided into three levels as well: level-one 3.0-3.5, level-two 2.50-2.99, and level-three 2.0-2.49. The music and music teaching competencies with means of level-one are considered very useful that should be applied in the kindergarten classroom.

The mean for music competencies as a group was 2.7, which means that all 24 items were considered useful by inservice teachers in their college preparatory courses. The same was the case for the “music teaching competencies” group, which had a mean of 2.9.

Table 4 displays the means of the music competency group, from 2.3 to 3.0. Among the means for each of the eight categories, the mean for “rhythm skills” (3.0) was the highest, while that for “aural skills” (2.4) was lowest (see Table 4). Six items with means of 3.0 are scaled as the highest means in the music competency group.

Table 4. Means for the Music Competencies of Inservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category & Item N Mean S.D Level Music competency 123 2.7 0.6

Knowledge about music 125 2.6 0.6 1. Identify and define commonly used music

symbols and terminology

129 2.5 0.8 2 2. Visually classify instruments by group 129 2.6 0.7 2 3. Visually identify specific orchestral and folk

instruments

129 2.3 0.8 3 4. Identify the basic musical concepts of rhythm 129 2.9 0.8 2 5. Identify a logical teaching sequence for

musical concepts

Singing skills 125 2.8 0.8 6. Sing a children’s song with melodic and

rhythmic accuracy

125 3.0 0.8 1 7. Sing a typical folk song accurately and in tune 125 2.6 0.8 2 8. Demonstrate, with the voice, proper diction or

articulation

125 2.7 1.0 2 Aural skills 125 2.4 0.7

9. Listen to and identify phrases within a song that repeat, contrast, or vary

125 2.3 0.7 3 10. Aurally identify specific instrument groups

used in a composition

125 2.4 0.9 3 11. Aurally identify specific orchestral and folk

instruments

125 2.4 0.9 3 Music reading skills 125 2.7 0.9

12. Read pitches on the treble staff 125 2.7 1.0 2 Rhythm skills 125 3.0 0.8

13. Read and perform rhythm patterns on simple percussion instruments

125 2.8 0.9 2 14. Clap a steady beat while singing a children’s

song

125 3.0 0.9 1 15. Tap a simple four-beat rhythmic pattern on

the drum

125 3.0 0.9 1 Keyboard skills 124 2.8 0.8

16. Use the keyboard to play simple melodies or accompaniment

125 3.0 0.9 1 17. Use the keyboard to simultaneously play

song melodies and accompaniments from printed notation

125 3.0 0.9 1

18. Use the keyboard to play song melodies with simple chords when the chords are indicated with chord symbols

125 2.7 0.9 2

19. Use the keyboard to establish the key (tonality) and starting pitch of a song

127 2.6 1.0 2 20. Transpose melodies and accompaniment

into other keys at the keyboard

128 2.5 1.0 Playing instruments skills 129 2.8 1.0 21. Play a variety of children’s percussion

instruments

129 2.8 1.0 Improvisation/composition skills 127 2.8 0.7

42. Respond to music through physical movement, demonstrating an awareness of the expressive possibilities of rhythmic, melodic, and formal organization

127 3.0 0.8 1

43. Create and notate rhythm compositions in various meters

127 2.4 0.9 3 44. Devise rhythmic accompaniment that can be

played on simple percussion instruments

1=not useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = rather useful, 4 = very useful) (Missing = No response)

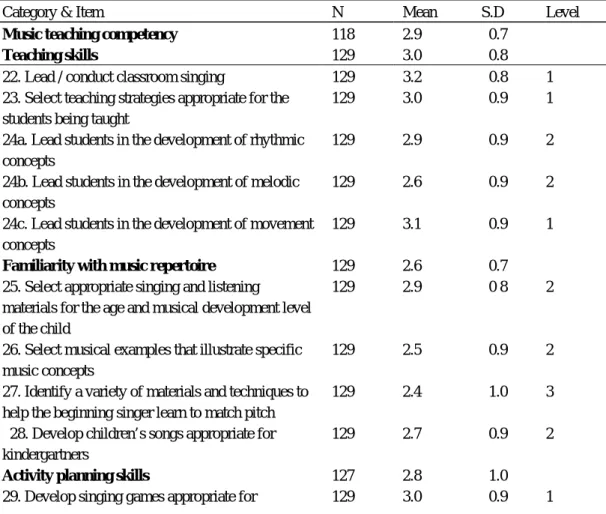

Table 5 reports the means for 24 items, grouped into five categories, regarding music-teaching competencies. The mean for the “teaching skills” category (3.0) is highest. Therefore, “teaching skills” were thought by the inservice teachers to be the most necessary skills, followed by “professional teaching competency,” with a mean of 2.9. Among the 24 items in the music-teaching competency group, the “ability to lead / conduct classroom singing” and the “ability to organize sequences and to implement learning experiences that encourage musical growth through the

development of listening, performing, and creative skills” were rated highest, with a mean of 3.2. The “ability to develop children’s songs appropriate for

kindergartners” was rated lowest, with a mean of 2.4 (see Table 5).

Table 5. Means for Music-Teaching Competencies of Inservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category & Item N Mean S.D Level Music teaching competency 118 2.9 0.7 Teaching skills 129 3.0 0.8 22. Lead / conduct classroom singing 129 3.2 0.8 1 23. Select teaching strategies appropriate for the

students being taught

129 3.0 0.9 1 24a. Lead students in the development of rhythmic

concepts

129 2.9 0.9 2 24b. Lead students in the development of melodic

concepts

129 2.6 0.9 2 24c. Lead students in the development of movement

concepts

129 3.1 0.9 1 Familiarity with music repertoire 129 2.6 0.7 25. Select appropriate singing and listening

materials for the age and musical development level of the child

129 2.9 0 8 2

26. Select musical examples that illustrate specific music concepts

129 2.5 0.9 2 27. Identify a variety of materials and techniques to

help the beginning singer learn to match pitch

129 2.4 1.0 3 28. Develop children’s songs appropriate for

kindergartners

kindergartners

30. Select appropriate music for listening lessons 129 2.9 1.0 2 31. Organize sequences and implement learning

experiences that encourage musical growth through the development of listening, performing ,and creative skills

129 3.2 0.7 1

32. Plan individual lessons dealing with specific skills and concept areas

128 2.8 0.9 2 33. Sequence a series of music lessons, leading to

the attainment of stated program goals and objectives

127 2.6 1.0 2

34. Establish long-term goals and objectives for the music curriculum that are appropriate for the age and musical development level of the child

127 2.5 1.0 2

Professional teaching competencies 125 2.9 0.7 35. Provide a creative, interesting, well paced

presentation involving a breadth of activities

127 3.0 1.0 1 36. Exhibit enthusiasm for teaching and caring for

the students

127 3.0 0.8 1 37. Develop within students observable enjoyment /

interest / enthusiasm for music and music participation

127 3.1 0.9 1

38. Command and receive the respect of students while maintaining strong and fair discipline

126 2.7 0.9 2 39. Integrate music with other subjects 126 2.9 0.9 2 40. Use positive group management techniques 127 3.1 0.8 1 41. Identify potential community resources that

might enhance musical learning

127 2.6 0.9 2 Assessment skills 120 2.6 0.8 2 45. Detect melodic and rhythmic errors in children’s

singing

127 2.7 0.9 2 46. Detect pitch in group singing 122 2.5 1.0 2

1 = not useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = rather useful, 4 = very useful) (Missing = No response)

Research Question 3

Are there significant differences in the self-perceived needs for music teaching between preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers?

few differences between the means of inservice and preservice teachers in the music competency group. Sometimes they are exactly the same. There are also four items that have identical means for inservice and preservice teachers. Twelve items have slight mean differences of 0.1, seven items have a mean difference of 0.2, and one item has a mean difference of 0.3. Because the mean differences are very slight, it can be concluded that inservice and preservice teachers have the same needs

concerning music competencies in their college preparatory courses (see Table 2 & 4).

In addition, nineteen items of music competencies were rated at the same levels by inservice and preservice participants, four items were rated higher by preservice teachers than by inservice teachers, and one item was rated higher by inservice teachers than by preservice teachers (see Table 2 & 4).

The individual item mean for all 24 music-teaching competency items was 2.9 for inservice teachers and 2.7 for preservice teachers. The means for music-teaching competencies of inservice teachers are from 2.4 to 3.2. On the other hand, the means of preservice teachers are between 2.5 and 3.1. Inservice and preservice teachers had the same viewpoint on 8 out of 24 items on the questionnaire (PKTNMC), with the same means. In the “activity planning skills” category, 4 items out of 6 had the same values for the two groups of participants. As with the music competencies, there are slight differences between the means of inservice and preservice teachers for music-teaching competencies. For example, seven items show mean differences of 0.1, another seven show differences of 0.2; one item has a moderate mean difference of 0.3, and one item has a mean difference of 0.4. Based on the information, inservice and preservice teachers have the same needs where music-teaching competencies are concerned in their preparatory college courses (seeTable 3 & 5).

The t-Test

For this study, the investigator conducted an inferential statistical independent t-test. The investigator employed the t-test to test a null hypothesis regarding the observed difference between two means (Patten, 1997). The two-tailed independent t-test was used because the investigator was testing whether or not the mean values of inservice and preservice teachers were different. The investigator did not have a directional hypothesis postulated as part of the study. Instead, she employed a non-directional alternative hypothesis (Hinkle, Jurs, & Wiersma, 1988).

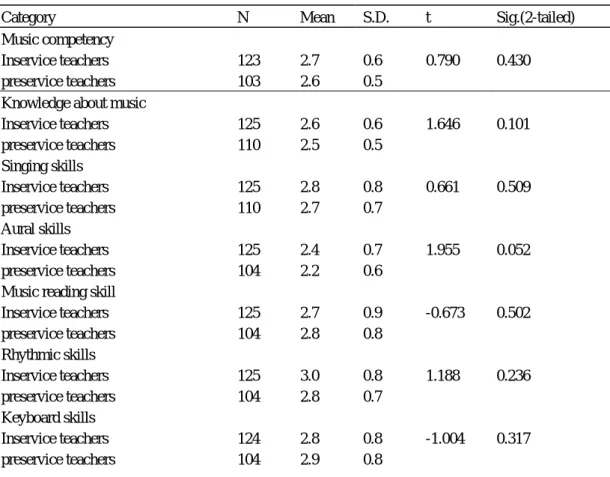

Table 6 displays the results of the t-test for music competencies of inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers. The results show that there is no significant mean difference in eight categories of the music competency group. The significant value of “Aural skills” is 0.052, which is very close to the value 0.05, however, which can almost be considered a significant difference between inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers (see Table 6).

Table 6. T-test Analysis of Music Competencies of Inservice and Preservice Teachers

Category N Mean S.D. t Sig.(2-tailed)

Music competency

Inservice teachers 123 2.7 0.6 0.790 0.430 preservice teachers 103 2.6 0.5

Knowledge about music Inservice teachers 125 2.6 0.6 1.646 0.101 preservice teachers 110 2.5 0.5 Singing skills Inservice teachers 125 2.8 0.8 0.661 0.509 preservice teachers 110 2.7 0.7 Aural skills Inservice teachers 125 2.4 0.7 1.955 0.052 preservice teachers 104 2.2 0.6

Instrument playing skills Inservice teachers 129 2.8 1.0 1.467 0.144 preservice teachers 104 2.6 0.9 Improvisation / composition Inservice teachers 127 2.8 0.7 0.083 0.934 preservice teachers 106 2.7 0.7

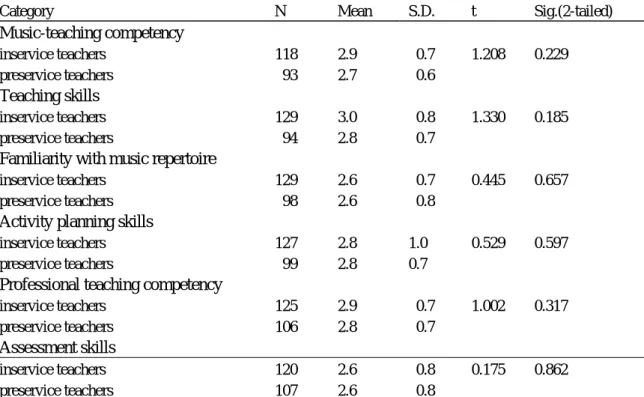

Table 7 shows that for music-teaching competencies, there is no significant mean difference between inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers regarding

music-teaching competencies (see Table7).

Table 7. T-test for Music-Teaching Competencies of Inservice and Preservice Teachers

Category N Mean S.D. t Sig.(2-tailed)

Music-teaching competency inservice teachers 118 2.9 0.7 1.208 0.229 preservice teachers 93 2.7 0.6 Teaching skills inservice teachers 129 3.0 0.8 1.330 0.185 preservice teachers 94 2.8 0.7

Familiarity with music repertoire

inservice teachers 129 2.6 0.7 0.445 0.657 preservice teachers 98 2.6 0.8

Activity planning skills

inservice teachers 127 2.8 1.0 0.529 0.597 preservice teachers 99 2.8 0.7

Professional teaching competency

inservice teachers 125 2.9 0.7 1.002 0.317 preservice teachers 106 2.8 0.7

Assessment skills

inservice teachers 120 2.6 0.8 0.175 0.862 preservice teachers 107 2.6 0.8

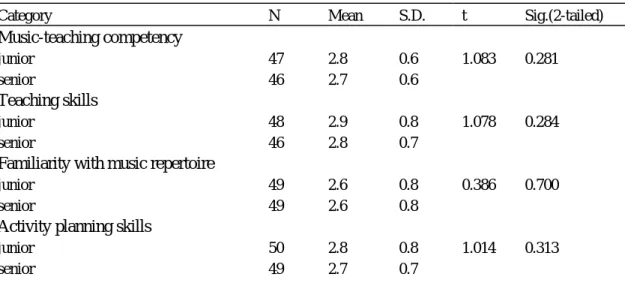

Table 8 reveals that, according to the t-test analysis, there is no significant mean difference between junior and senior preservice kindergarten teachers regarding music competencies. This result is very similar to the comparison of inservice and

preservice kindergarten teachers (see Table 8).

Table 8. T-test Results for Music Competency of Junior and Senior Preservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category N Mean S.D. t Sig.(2-tailed)

Music competency

senior 52 2.7 0.6

Knowledge about music

junior 55 2.5 0.5 -0.319 0.751 senior 55 2.5 0.6 Singing skills junior 55 2.7 0.7 -0.175 0.862 senior 55 2.7 0.8 Aural skills junior 52 2.2 0.6 0.450 0.654 senior 52 2.2 0.5

Music reading skill

junior 52 2.7 0.9 -0.469 0.640 senior 52 2.8 0.9 Rhythmic skills junior 52 2.9 0.7 0.444 0.658 senior 52 2.8 0.8 Keyboard skills junior 52 2.9 0.8 0.026 0.979 senior 52 2.9 0.7

Instrument playing skills

junior 52 2.6 0.9 0.537 0.592

senior 52 2.5 0.9

Improvisation / composition

junior 54 2.7 0.7 -0.886 0.377

senior 52 2.8 0.8

Table 9 shows the results of the t-test on music-teaching competencies of junior and senior preservice kindergarten teachers. There is no significant mean difference between the two groups of preservice teachers for either music or music-teaching competencies (see Table 9).

Table 9. T-test Results for Music-Teaching Competencies of Junior and Senior Preservice Kindergarten Teachers

Category N Mean S.D. t Sig.(2-tailed)

Music-teaching competency junior 47 2.8 0.6 1.083 0.281 senior 46 2.7 0.6 Teaching skills junior 48 2.9 0.8 1.078 0.284 senior 46 2.8 0.7

Familiarity with music repertoire

junior 49 2.6 0.8 0.386 0.700 senior 49 2.6 0.8

Activity planning skills

Professional teaching competency junior 54 2.9 0.7 1.405 0.163 senior 52 2.7 0.7 Assessment skills junior 55 2.6 0.8 0.826 0.411 senior 52 2.5 .8

In sum, the mean differences between inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers are very slight for both music competency and music-teaching competency, as are the differences between junior and senior preservice teachers. Consequently, it can be statistically concluded that inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers have the same needs concerning music competencies and music-teaching

competencies as do junior and senior preservice teachers in their preparatory college courses.

Discussion

This study was designed to examine kindergarten music teachers’ perceptions of their own competency levels. It also aimed to determine whether inservice teachers, with their inservice training, have different perceptions from preservice teachers with their preservice training. The following discussion section is concerned with the findings from the analysis of the responses to the questionnaire, which examined the kindergarten teachers’ perceptions of their music skills and music-teaching

competencies. The major findings revealed in this study are described below. 1. Inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers have very similar viewpoints on the “very useful” competency levels for both music and music-teaching. As can be seen from the results, both inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers rated singing, movement, keyboard applications, and rhythmic ability as very useful competencies, under the “music competency” category. This result is similar to Wenerd’s findings (1989). Wenerd listed six popular musical experiences offered in American kindergartens: singing, movement, listening,

instrumental activity, improvisation of melodies, and sound exploration. Morin (1994) emphasized that singing, listening, playing instruments, and moving were four

in their study that inservice kindergarten teachers considered the ability to develop movement activities, the ability to lead and teach songs, and piano-playing skills as useful in their teaching.

Singing is the most frequent activity in kindergarten. Singing activities help children discover the world of pitch. Preparatory college music courses may provide a singing course for kindergarten teachers in order to help them discover ways to employ singing in their lessons (Daniels, 1992; Malin, 1993; Teachout, 1997).

Other teaching competencies considered to be very useful by both inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers included the following: leading students in

development of concepts, in singing, and in movement activities; developing children’s interest and enjoyment in music and music participation; exhibiting enthusiasm for teaching and caring for children, and organizing sequences to

encourage children’s musical growth. Kinder (1988) found that five types of teacher preparation were rated most important by classroom teachers: demonstrations of how to teach action songs, demonstrations of the organization of musical activities around a holiday, observing music being taught by a specialist, learning to use rhythm and melody instruments, and learning to sing. Teachout (1997) found seven common behaviors rated within the 10 top-ranked items by both inservice and preservice music teachers: be mature and have self-control, be able to motivate students, possess strong leadership skills, involve students in the learning process, display confidence, be organized, and employ a positive approach.

With agreement among inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers with varied teaching experiences, these music and music-teaching competencies are considered to be particularly important for kindergarten music teaching, according to this study.

useful” music-teaching competencies rated as level 1 by preservice teachers were identical to five out of the nine competencies placed in this group by inservice teachers. As for the “useful” music competencies, rated as level 2, 11 out of 13 music competencies placed in this group by preservice teachers were the same as 11 out of 13 competencies placed in this group by inservice teachers. For the “useful” music-teaching competencies, in level 2, inservice teachers included 14, identical to 14 out of 19 competencies chosen by preservice teachers. Among level 3

“somewhat useful” music competencies, four out of six competencies chosen by preservice teachers were the same as four out of five competencies chosen by inservice teachers.

In Soderblom’s survey (1982, Competencies Rating Questionnaire), the music skills of conducting, singing, and ancillary instruments were regarded as essential music competencies, and the instructional planning was viewed as an essential

music-teaching competency for first-year elementary school general music instructors, as judged by college teachers, experienced teachers, and first-year teachers.

Additionally, Morin (1994) indicated that three music course topics showed a high level of agreement between inservice and preservice teachers: music methods and materials for K- Grade 6, planning music instruction, and singing with children. Goodman (1985) assessed the perceived music and music-teaching competencies of classroom teachers from three different types of school system: city, county, and exempted village. He ascertained the perceived effectiveness of preservice training in music and music education in college. All of the classroom teachers agreed that their competencies from their undergraduate preparation were somewhat effective for providing music instruction in the classroom, and undergraduate music courses did affect teacher perceptions of their competence.

teachers.

3. There is no statistically significant difference in the findings of this study. However, there are very slight mean differences between inservice and

preservice kindergarten teachers on category means, item means, and competency group means. An examination of the 24 music-competency items shows four item means scaled identically by inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers. Twelve items had very slight 0.1 mean differences. Seven items had 0.2 mean differences, and one item had a 0.3 mean difference (see Table 2 & 4). As for the 24 items concerning music-teaching competencies, eight items were scaled identically by inservice and preservice teachers. Seven items had 0.1 mean

differences. The other seven items had 0.2 mean differences. One item had a little difference of 0.3, and the remaining item had a 0.4 mean difference (see Table 3 & 5).

In Teachout’s study (1997), he reported similar findings after examining

teaching skills and behaviors of experienced music teachers and preservice teachers. Seven out of 10 top-ranked skills and behaviors were common to the lists of both groups and were indicated to be the most important to successful teaching by both experienced and preservice music teachers. However, they ranked these 10 top skills and behaviors slightly differently due to their different experiences.

In addition, Morin (1994) found that there were significant differences in the ratings of preservice and inservice teachers in four skill areas: music composition and improvisation, playing the ukelele / guitar, teaching music reading, and playing the recorder. The general trend for both groups, however, was to place these items in the “least useful” category.

4. Inservice kindergarten teachers generally rated these music and

inservice teachers were higher than those of the preservice teachers. Only two category means of the inservice teachers were lower than those of the preservice teachers. Among the 24 item means for music competencies, the inservice teachers had 12 item means higher than the item means of the preservice teachers, four item means equal to those of the preservice teachers, and eight item means lower than those of the preservice teachers, including five items in the keyboard skills category. There were five items in this category, and all five item means were higher for

preservice teachers than for inservice teachers. It can be assumed that preservice kindergarten teachers expect keyboard skills to play an important role in kindergarten music teaching. Inservice teachers, however, find that this does not turn out to be so (see Table 2 & 4).

Similarly, the mean value for music-teaching competencies was 2.9 for inservice teachers, higher than the preservice teachers’ mean of 2.7. The music-teaching competencies consisted of 24 items within five categories. Two category means were rated higher by inservice teachers than by preservice teachers, and three

category means were rated equally by inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers. Of the 24 item means, 13 item means were rated higher by inservice teachers than by preservice teachers. There were eight item means rated equally by inservice and preservice teachers, and only three item means were rated lower by inservice teachers than by preservice teachers (see Table 3 & 5).

Overall, 37 item means out of 48 were rated equal or higher by inservice

kindergarten teachers than by preservice teachers. It can be assumed, therefore, that inservice kindergarten teachers use those music and music-teaching competencies more than preservice teachers would expect. The inservice teachers judged the importance of the competencies by drawing on their professional experience and found that some corresponded with their actual needs. The importance of the competencies to inservice kindergarten teachers was beyond the expectations of the preservice teachers.

(1997) had similar findings in his research that some teaching skills and behaviors were ranked higher by experienced music teachers than by preservice music teachers. Because of their teaching experiences, experienced music teachers consider some skills and behaviors more crucial for initial success than do preservice teachers. For example, “Be enthusiastic, energetic,” “Maximize time on task,” “Maintain student behavior (strong, but fair discipline),” and “Be patient.”

Sefzik (1983) inquired into the effectiveness, as perceived by elementary school teachers in their first three years of teaching, of teacher preparation programs in six areas of competency: classroom discipline, skills for teaching specific subjects, student evaluation, teaching methods and strategies, human relations skills, and skills for teaching special students. The findings showed that in every area but teaching methods and strategies, the youngest teachers, ages 20-24, had higher mean scores than did the other two groups of teachers, those aged 25-29 years and those age 30 and above. Perhaps the youngest teachers were showing more youthful enthusiasm for their teaching situations.

CONCLUSIONS

Music and music-teaching competencies are perceived as having an important value in early childhood education. It is assumed that a kindergarten teacher with adequate music and music-teaching competencies will be able to provide appropriate music instruction for her kindergartners. This study attempted to provide an

accurate description of the music and music-teaching competencies considered important by selected Taiwanese kindergarten teachers, and, more specifically, to examine the kinds of music and music-teaching competencies gained from their teacher training program that are useful for teaching music in kindergarten.

The findings of this study suggest the following conclusions:

resources to ensure that graduates of both inservice and preservice programs in Early Childhood Education are well prepared to meet the growing need for music education at the kindergarten level.

2. All of the inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers surveyed agreed that all the competencies listed in this questionnaire were at least “somewhat useful.” It could be assumed that these kindergarten teachers would accept a teacher training program which provided those useful competencies. All means scores for the 48 items were rated beyond two points (1 = not useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = rather useful, 4 = very useful), which means that all of the respondents agreed that the music competencies and music-teaching competencies mentioned were correspondent with their needs and applicable to their current or future teaching. Therefore, it must be assumed that Pingtung Teachers College provides appropriate music courses for both inservice and preservice kindergarten teachers.

3. Teachers Colleges should provide more conferences or training programs to help kindergarten teachers learn a variety of competencies, since inservice teachers know what kind of competencies they actually need.

4. Based on the results of this study, the music courses for preservice and inservice kindergarten teachers should contain not only the development of various music and music-teaching competencies and understandings, but also guidance in exploring teaching strategies and course materials for integrating music into other subject areas. Music professors and administrators at the Teachers Colleges should be looking to provide an effective teacher preparation program, to promote

kindergarten teachers’ positive attitudes toward their musical abilities, and the implementation of those abilities for successful teaching. With more music and music-teaching competencies, kindergarten teachers will be able to better use music in their music teaching.

student population.

Recommendations for Further Research

According to the findings and conclusions of this investigation, the following recommendations would appear to be in order:1. A new music curriculum, integrated with other arts, will be published in September 2000, in Taiwan. Further research based on the present study should take into consideration the music and music-teaching competencies included in this new curriculum.

2. This study should be repeated once a year for a period of three years, in order to investigate fluctuations in the self-perceived effectiveness of teacher preparation programs in the Teachers Colleges. The findings of these replicated studies will assist the Teachers Colleges in improving the quality of their teacher training programs.

3. A similar study of the perceptions of kindergarten teachers concerning the usefulness of the music content of their teacher training programs could be extended in order to further ascertain kindergarten teachers’ needs on a nationwide basis. A comparison of usefulness ratings could be made among similar counties in Taiwan.

4. An extension of the present study could survey other subjects, elementary school music teachers, music supervisors, and college professors who teach music teaching methods for young children, for example, using the same questionnaire. Elementary school music teachers and supervisors may have different opinions about the competencies needed in the schools.

teachers’ background variables affect their responses on the questionnaire regarding music competencies and music-teaching competencies.

The investigator’s goal, in conducting this study, was to examine kindergarten music teachers’ perceptions of their own competency levels, as well as to identify any differences in the perceptions of inservice and preservice teachers in this regard. It was found that differences did exist between the perceptions of the two groups due to the professional experience of the inservice teachers. However, the differences were slight, and mostly variations in degree, making this study a very useful instrument for the Teachers Colleges to develop new curricula that focus on the effectiveness of the teacher training provided.

REFERENCES

Anastasi, A. (1982). Psychological testing (5th ed). New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Baker, D. S. & Saunders, T. C. (1991). In-Service classroom teachers’ perceptions of useful music skills and understandings. Journal of Research in Music

Education, 39(3), 248-261.

Baker, P. J. (1981). The development of music teacher checklists for use by

administrators, music supervisors, and teachers in evaluating music teaching effectiveness. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon.

Birch, W. (1969). Factors related to differences in classroom teachers’ attitude toward music. Dissertation Abstracts International, 30, 1743A.

Blackburn, J. E., Coop, R. H., & Stegall, J. R.,(1978). Administrators’ ratings of competencies for an undergraduate music education curriculum. Journal Research

in Music Education, 26(1), 3-15.

Bloom, B. S. (1964). Stability and change in human characteristics. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Boyle, J. D., & Thompson, K. P. (1976). Changing inservice teachers’ self-perceptions of their ability to be effective teachers of the arts. Journal of

Research in Music Education, 24(4), 187-196.

Bresler, L. (1994). Music in a double-bind: Instruction by non-specialist in elementary schools. Arts Education Policy Review. 95(3), 30-36.

Daniels, R. D. (1992). Preschool music education in four Southeastern State: Survey and recommendations. Update Application of Resouch in Music Education, 10(2), 16-19.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books.

Goodman, J. L. (1985). Perceived music and music-teaching competencies of

classroom teachers in the state of Ohio. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The

Ohio State University.

Hinkle, D. E., Jurs, S. G., & Wiersma, W. (1988). Applied statistics for the

behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Housewright, W. L. (1972). Charge to the commission “Teacher Education in

Music” : Final Report. Washington, D.C. Music Educators National Conference.

Kinder, G. A. (1988). A survey of the musical activities of classroom teachers with implication for undergraduate music courses for elementary education majors (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, 1987). Dissertation Abstracts

International, 48(07), 1691A.

McDonald, D. T., & Simons, G. M. (1989). Musical growth and development:

Birth through six. New York: Schirmer Books.

Malin, S. A. M. (1993). Music experiences in the elementary classroom as directed

and reported by in-service elementary classroom teachers. Unpublished doctoral

dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Montgomery, A. (1995). The importance of music teaching competencies as rated by elementary classroom teachers and university methods instructors. Canadian

Journal of Research in Music Education, 36(7), 19-26.

Morin, F. (1994). Beliefs of pre-service and in-service early years/elementary

dissertation, University of Manitoba.

Morin, F. (1995). The effects of a music course and student teaching experience on early years/elementary pre-service teachers’ orientations toward music and teaching. Canadian Journal of Research in Music Education, 36(7), 5-12.

Norusis, M. J. (1995). Statistical package for the social sciences. Chicage, IL: SPSS, Inc.

Patten, M. (1997). Understanding research methods: An overview of the essentials. Los Angeles, CA: Pyrczak Publishing.

Romanek, M. L. (1971). A self-instructional program for the development of musical

concepts in preschool children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The

Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Scott, C. R. (1989). How children grow musically. Music Educators Journal, 76(2), 28-31.

Sefzik, W. P. (1983). A study of the effectiveness of teacher preparation programs in six areas of competency as perceived by elementary school teachers in Texas during their first three years of teaching. (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, 1983). Dissertation Abstracts International, 44(05), 1284A. (University Microfilms No. 1041).

Sims, W. (1994). Early Childhood Music Education. International Journal of Music Education, 24, 61-63.

Smith, A. B. (1985). An evaluation of music teacher competencies identified by The

Florida Music Educators Association and teacher assessment of undergraduate preparation to demonstrate those competencies. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,

The Florida State University.

Soderblom, C. J. (1982). Music and music-teaching competencies considered

essential for first-year elementary school general music teachers. Unpublished

doctoral dissertation, The University of Iowa.

Suzuki, S. (1983). Nurtured by love: The classic approach to talent education. Athens, OH: A Senzay.

behaviors important to successful music teaching. Journal Research in Music

Education, 45(1), 41-50.

Tzai, T. M., & Lin, Y. W. (1987). Kindergarten music education of past forty years.

Education Information, 12, 465-495.

Wenerd, B. M. (1989). A status report of early childhood music education in

thirty-four preschool centers of south central Pennsylvania. Unpublished

master’s thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park. Wu, H. I. (1999). Experience and attitude of kindergarten teachers toward

implementing music in their classrooms in the Kaohsiung and Pingtung regions of Taiwan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University,