CHAPTER 2 Literature Review

This chapter provides an overview of literature in the areas relevant to the present

study and consists of six sections. The first section introduces the process of reading

comprehension and summarizes its application to early EFL reading. The second

section provides a brief description of the building blocks of an effective early reading

instruction. The third section reviews literatures related to the learning strategy of

scaffolding. Its application on to reading instruction is also discussed. The fourth

section provides a brief interpretation of collaborative learning and its application on

reading instruction. The fifth section introduces a brief categorization of computer

technology application on reading instruction. The last section reviews the late

application of mobile technology in learning and reading instruction.

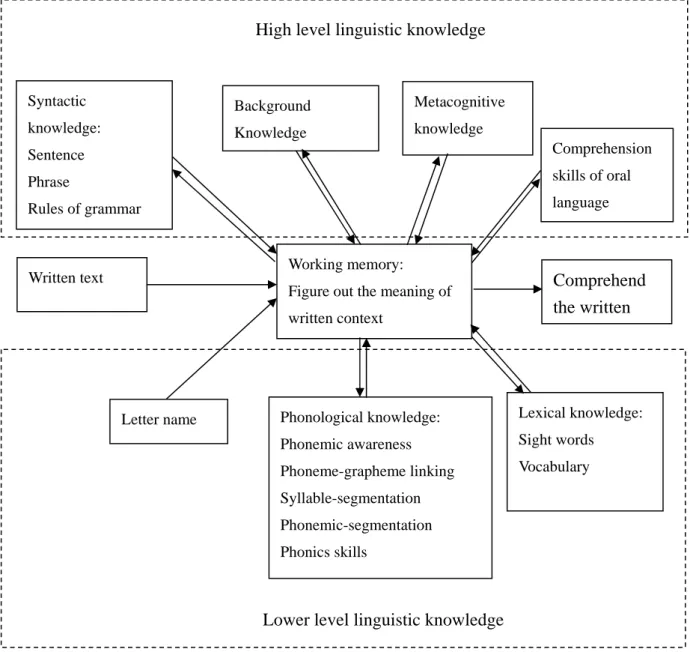

2.1 Reading comprehension process

Based on the theory of information processing systems, the language processing

can be viewed as a parallel interactive process (Carroll, 1999). While reading a context,

children use lower level linguistic knowledge, such as the phonological level, to

identify the phonemes and syllables that the lecture is using. Concurrently, they also

use higher level lexical knowledge, such as the lexical level from their semantic

memory to retrieve the lexical entries of the words based on the identified phonemes

and syllables. Ehri (1995, p.11) called it an interactive model of the reading process. In

order to reconstruct language during reading, the reader must attend to syntactic,

semantic and pragmatic strategies. Decoding must be automatic and the corresponding

words must be easily connected with the words during decoding. Compared with

Ehri’s interactive reading process model, to an EFL early reader the background

knowledge acquired by their first language (Lin, 2002) and the oral language skills

(Rivers, 1981) are also essential high level linguistic skills while reading a written

context. Based on Ehri’s reading process model, this mental process of EFL early

reading was modified in a mutually interactive cognitive processing model as in Figure

1.

Working memory:

Figure out the meaning of written context

Comprehension skills of oral language Metacognitive

knowledge

Lexical knowledge:

Sight words Vocabulary Letter name

Background Knowledge

Syntactic knowledge:

Sentence Phrase

Rules of grammar

Written text

Phonological knowledge:

Phonemic awareness Phoneme-grapheme linking Syllable-segmentation Phonemic-segmentation Phonics skills

Lower level linguistic knowledge High level linguistic knowledge

Comprehend the written

Figure 1. Mutual interactive cognitive processing model of EFL early reading.

In this model both top-down and bottom-up processes operate in parallel. That is

readers use low level knowledge, such as phonemic awareness and phonics skills, to

identify the phonemes and syllables that the context is using. Simultaneously, they also

use a higher level knowledge, the lexical knowledge, to retrieve the lexical entries of

the words from semantic memory via those identified phonemes and syllables. Then

they match the identified words with the sight words, vocabulary and spoken language

as well as involving the syntactic knowledge and background knowledge to figure out

the meaning of the text. A reader’s lower level linguistic skills, such as phonological

knowledge and Lexical knowledge, must be automatic or the working memory of the

reader will not have enough capacity to process the higher level lexical information. As

a result, children will fail in comprehending a written context. Research evidence also

suggested that such low level linguistic skills are appropriate predictors of children’s

later reading achievement (Anthony, Lonigan, Driscoll, Phillips, & Burgess, 2003;

Guron & Lundberg, 2003; Hulme, 2002; Larrivee & Catts, 1999; Mody, 2003;

Nag-Arulmani, Reddy, & Buckley, 2003; Passenger, Stuart, & Terrell, 2000; Vadasy,

Jenkins, & Pool, 2000). That is, each child should develop those skills in early school

years otherwise there will be a bigger probability that he or she will fail in later reading

achievement.

This brings EFL reading to a natural balance between meaning and skill-based

learning (Bensoussan, 1998). It also underlines the importance of the automation of the

interacting cognitive and linguistic processes during reading. Numerous researches are

consistent with the above argument (Frost, 2000; Pressley, 1998; Strickland, 1998),

they all emphasize the importance of introducing reading for meaning, and not simply

decoding, right after the pupils have some low level linguistic knowledge of the

spoken language (Brewster & Ellis, 2002).

2.2 Early reading instruction program

According to the research report conducted by the NRP (2000), an effective

elementary reading program must contain the following five components: (1)

phonemic awareness instruction to help children learn to notice, think about, and work

with the individual sounds in spoken words; (2) phonics instruction to teach children

the relationships between the letters (graphemes) of written language and the

individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language; (3) fluency instruction to children

so that they learn to read a text accurately and quickly; (4) vocabulary instruction to

increase the number of words for which children know the meanings; and (5) text

comprehension instruction help children become purposeful and active readers.

The five components need to be integrated as children learn to read. Therefore, an

effective elementary EFL reading program should be balanced and capable of

providing elementary EFL learners with effective training activities of low level

linguistics knowledge (phoneme awareness, phonics, and vocabulary) as well as the

opportunities to apply this low level linguistics knowledge to fluently read a text and

comprehend its meaning.

Unfortunately only phonics and oral communication skills are taught in most

elementary EFL settings of Taiwan (Lan, Chang, & Sung ,2004), the EFL teachers’

lack of experience in designing and teaching a reading program is correspondent with

the requirement argued by the NRP. Thus it is urgent that a balanced elementary EFL

reading program is constructed which is fit for the reality of elementary EFL settings in

Taiwan. This thesis will develop a balanced elementary EFL reading program

according to requirements for an effective elementary reading program. This will

provide further understanding about the above issue.

2.3 Scaffolding

Scaffolding is providing enough support to enable learners to succeed in more

complex tasks, and hence to extend the range of experiences from which they can learn

(Davis & Linn, 2000). It often involves providing support (models, cues, prompts,

hints, partial solutions) to students to bridge the gap between what students can do on

their own and what they can do with guidance from others (advanced peers, teacher, or

other adults). The goal of providing scaffolds is for students to become independent,

self-regulated thinkers who are more self-sufficient and less teacher or peer dependent.

Thus the support is temporary, and can be gradually decreased as students’ competence

increases (Diaz-Rico & Weed, 2002; Rosenshine & Meister, 1992). In addition, the

teacher’s role shifts from being a model or an instructor to being a manager who gives

cues as well as corrective and real-time feedback.

There are two types of scaffolding involved in reading instructions for at-risk

children when the focus is on who offers the scaffolding support. One type of

scaffolding gave positive comments about efficiency of peer-assisted learning

strategies (Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, & Simmons, 1997; George & Patrick, 2002; Mathes,

Torgesen, & Allor, 2001). As Hartup (1992) said that children teaching each other are

generally effective in cognitive activities. Similarly, Greenwood and his colleagues

(Greenwood, 1996) have reported that the Class Wide Peer Tutoring model they have

used, increased the improvements in learning outcomes in reading.

Another type of scaffolding involves adult-child interactive dialogue (Bellon &

Ogleetree, & Harn, 2000; Juel, 1996). Adult involvement in any activity with children

can promote the efficiency of the learning process (Vygotsky, 1978). Other researches

pointed out that adult speech played an important role in young child’s language

acquisition (Bloom & Lahey, 1978; Brown, 1958; Mervis & Mervis, 1982; Ninio &

Bruner, 1978). The study results suggested that adult naming practices guide children

through lexical development. Like Campbell (2001) concluded in a longitudinal study

of one child’s interactive story reading from birth to 5-years-of-age, without direct

teaching she acquired a visual memory of words and knowledge of phonics and she

also showed an increasing sensitivity to rhythm, which she used in her writing, and an

empathy with the story. Just as argued by Cazden (1983) that three forms of adult

“input” that occurred as parents communicated with young children: scaffolds, models,

and direct instruction play an important role in child’s language development.

Although peer-assisted learning benefits children’s cognitive learning activities

and increases the improvements in learning outcomes in reading, the reality of

elementary EFL setting in Asia might inhibit the effect of scaffolding on teaching

reading. The EFL settings in Asia are quite different from that in the Western countries.

As an example, in Taiwan, there are about 30 students with diverse reading abilities in

an EFL class at elementary level. Some of them are able to read individually, yet some

of them are unable to recognize the common sight words or to decode and encode a

new word. There is only one EFL teacher to take charge all of the teaching and

classroom management tasks. The teaching time is only 2 forty-minute lessons a week.

Furthermore, the resources that are available to the EFL teachers and learners are quite

different between city and town locations.

In an elementary EFL class in Taiwan, does peer-assisted learning happen in a

small reading group? If it does, are there any difficulties reducing the effect of

peer-assisted learning in a small reading group? In addition, how to embed the adult’s

(the EFL teacher’s) scaffolding in reading activities run in a small reading group? All

these questions will be investigated in this study.

2.4 Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning is a learning approach in which peer interaction plays a

significant role (Ravenscroft, Buckless, & Hassall, 1999) and students work together to

accomplish shared goals (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). While using collaborative

learning approaches, teachers need to make sure that all students are actively involved

in the process working towards a common goal (Artz & Newman, 1990). Rather than a

seating arrangement, in collaborative learning, students are positively interdependent

with each other in a teaching-learning situation to reach their learning goals. Five

essential components teachers should structure into lessons to guarantee students to

collaborate well: positive interdependence, promotive interaction, individual

accountability, interpersonal and small-group skills, and group processing (Johnson &

Johnson, 1994). The idea is that lessons are created in such a way that students must

collaborate in order to achieve their learning objectives.

Collaborative learning can be implemented in three basic forms: tutoring (peer or

cross-age), in which one student teaches another; pairs, in which students work and

learn with each other; and small groups of students are teaching and learning together.

Spencer Kagan (1990) has identified several collaborative learning structures, which

are approaches of organizing the interaction of students by prescribing students’

behaviors step by step to accomplish their learning goal. Several well-known

collaborative learning structures are as follows: reciprocal peer tutoring (RPT)

(Fantuzzo, King, & Heller, 1992), Student Teams Achievement Division (STAD)

(Slavin, 1986), The Math Solution (Burns, 1987), Finding Out/Descubrimiento

(DeAvila & Duncan, 1980), Team Assisted Individualization (TAI) (Slavin, Levey, &

Madden, 1986), Teaching and Pair Methods, Group Investigation (Sharan & Sharan,

1976), Circles of Learning (Johnson, Johnson, & Holubec, 1986), and JIGSAW

(Slavin, 1986).

In a review of the literature on collaborative learning and students’ reading skills,

Ushioda (1996) suggests that collaborative learning can promote students’ learning

motivation and satisfaction. Researchers (Nichols & Miller, 1994) have also found that

collaborative learning helps push students involved in group goal pursuit. Slavin (1988)

found that collaborative learning methods are considerably more effective than

traditional methods in increasing basic achievement outcomes, including performance

on standardized tests of reading and language arts, mathematics, social studies, and

science. Students’ EFL reading achievement and academic self-esteem are improving

as well as their feeling of school alienation is decreasing in collaborative learning

situation (Ghaith, 2003).

Even though collaborative learning has been known as an effective teaching

method in EFL reading, it is necessary to have a further investigation specifically into

what interactive behaviors that Asian students have in collaborative learning

processing, into which collaborative learning activity structure will bring positive

results, and into what kind of role an EFL teacher in Asia should play in collaborative

reading activities. Also it is important to identify what difficulties the elementary EFL

learners experience that inhibit them from doing collaborative reading with their peers.

In this study, the analysis of qualitative data will provide further information about

these demands for applying collaborative learning strategy in the elementary EFL

settings in Asia.

2.5 Computer technology for early reading instruction

Computers are the latest technology to influence the learning activities in

classrooms. The research report conducted by Atkinson and Hansen (1966-1967) is the

first documented use of computers for reading instruction. Reitsma (1988) found that

independent reading practice with computer speech feedback was a useful tool for

helping improve early reading skills. The benefits of using computer instruction to

teach early reading skills are that students can receive targeted practice on areas of

weakness and can engage in rote skill learning, and the increased opportunity to

receive immediate corrective feedback. The application of computer in reading

instruction can be divided into two categories: The early reading skill training

including phonological knowledge and lexical knowledge; and text comprehension.

The research in the first category emphasizes the automation of the low level

linguistic knowledge, such as phonemic awareness, phonics, and vocabulary. On

phonemic awareness, computer technology is able to support phonemic awareness

instruction (Barker & Torgesen, 1995; Mioduser, Tur-Kaspa, & Leitner, 2000; Mitchell

& Fox, 2001; Reitsma & Wesseling, 1998; Van Daal & Reitsma, 2000) because of its

capability to enable immediate association between phonemes and graphemes (Foster,

Erickson, Foster, Brinkman, & Torgesen, 1994).

On phonics instruction, computer software specifically designed to drill students

to master the relationship, such as drilling children on consonant and vowel

letter-sound relationships (Burns, Roe & Ross, 1996; Grabe and Grabe, 1996), or

helping children’s understanding of word segmentation (Wise, 1992; Wise, Olson, &

Treiman, 1990), which, led by computer technology, is able to benefit children

developing fluency and accuracy in word identification.

On children’s vocabulary learning, the use of electronic talking books and

electronic texts with scaffolds has positive impact on supporting children’s vocabulary

development (Anderson-Inman & Horney, 1998; McKenna & Watkins, 1996; Reinking

& Rickman, 1990).

The researches in the second category emphasize mastering of the high level

knowledge, especially the use of metacognitive knowledge to comprehend a written

text. Computer technology is capable of supporting comprehension instruction by

using concept mapping to enhance text comprehension and summarization (Chang,

Sung, & Chen, 2002), of enhancing students’ strategy use and reading comprehension

(Sung, Huang, & Chang, under review). By using interactive texts (Higgins & Boone,

1991), e-books (Matthew, 1997; Medwell, 1996; Lewin, 1997) and multimedia

presentation of information, computer technology is also capable of facilitating

children’s reading comprehension ability (Sharp, Bransford, Goldman, Risko, Kinzer,

& Vye, 1995).

Though computer technology can support teaching and learning of the low or

high level linguistic knowledge needed in reading, one of the main problems caused by

the dichotomy of the computer software is a lack of a bridge between low level

linguistic knowledge and text comprehension. All the low level knowledge is a critical

part of text comprehension: students who are unable to recognize or decode written

words are unable to read fluently, or do not know the meanings of words and will be

limited in their abilities to comprehend text. Thus, it is worth investigating how to

provide children with a bridge between low level linguistic knowledge and text

comprehension by carefully designed scenarios. This thesis may add to the research on

this question.

2.6 Mobile leaning

Mobile Learning is the use of mobile or wireless devices for learning on the move.

Phones, computers and media devices now fit in our pockets and can connect us with a

variety of information resources and enable communication nearly anywhere and

anytime, which has led to mobile learning receiving increasing attention from

educators and researchers.

Many of the applications of mobile technology in education are using handheld

computers. According to Soloway, Norris, Blumenfeld, Fishman, Krajcik, and Marx

(2001), handheld computers will become an increasingly popular choice of technology

for K-12 classrooms because they will enable a transition from occasional,

supplemental use to frequent, integral use. For example, Tatar, Roschelle, Vahey, and

Penuel (2003) conducted a series of applications of using wireless handheld devices to

enhance K-12 classroom instruction; Zurita and Nussbaum (2004) used wirelessly

interconnected handheld computers in math and language activities for 6- and 7-year

old children; and Pinkwart, Hoppe, Milrad, and Perez (2003) used wireless Personal

Digital Assistants (PDAs) to support students’ collaborative knowledge building.

Some mobile learning applications are implemented by using tablet PCs. With the

feature of supporting specific editing function, tablet PCs allow students to note and

mark the learning materials, and to create works in an easy way. For example, the

WiTEC system (Liu, Ko, Chan, Wang, and Wei, 2004) is designed to support teachers

and students to promote communication, in which students read contents on their tablet

PCs, discuss with peers, and also create their work on their devices.

Some researchers, because of their popularity are interested in the potential

application of mobile phones in education. For example, Thornton and Houser (2004)

chose web-enable phones as a medium of delivery to help Japanese university students

learn English idioms.

To date the research into mobile learning gives a potential future that mobile

learning is capable of providing students with a rich, collaborative and conversational

experience in classrooms or out of school, still it is a challenge for educators and

researchers to understand and explore how best mobile technology might be used to

support learning and how students behave in mobile device-supported collaborative

learning activities. It is also important to ask how the existing theories and strategies of

learning to read might be drawn out to deal with the difficulties what inhibit

elementary EFL learners learn to read in a collaborative group. This study will provide

further understanding about this issue.