Exploring the Moderating Effects of the Hedonic/Utilitarian Value on Brand Extension Evaluations

Author: Wenchin Tsao1 Couchen Wu2

Position: Candidate of Marketing Ph.D., National Taiwan University of Science and Technology.

Professor, Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology

Exploring the Moderating Effects of the Hedonic/Utilitarian Value on Brand Extension Evaluations

1 Wenchin Tsao

Address: 台中縣太平市中山路一段 215 巷 35 號 Phone: 04-23924505 ext. 7775

Fax: 04-23929584 E-mail: tsao@ncit.edu.tw

2Couchen Wu

Address: 台北市基隆路 4 段 43 號

Phone: 02-27376751 Fax: 02-27376744

Email: wu@ba.ntust.edu.tw

Abstract

An experiment was designed to investigate how the hedonic/utilitarian value of proposed product extensions influences the consumers’ brand extension evaluations. The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed for testing moderating effects .The evidence reveals that the effects of perceived quality, perceived fit, and consumer knowledge on brand extension evaluations will be moderated by the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value.

Implications of these findings for marketing managers are presented along with suggestions for further research.

Key words: Brand extension, Hedonic value, Utilitarian value, Perceived quality, Perceived fit, Moderator

Introduction

Brand extensions—the use of a brand name established in one product class to enter another product class—have been at the core of strategic growth for many firms, especially during the past decade (Aaker, 1991). Firms often try to exploit their existing well-

established brands by extending them into new product categories. An extension to a well- established brand, when compared with a new brand, has the advantage that it may be perceived by consumers as less risky.

In the interests of understanding brand extension, researchers have developed various ideas about extension strategies (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Barone et al., 2000; Bhat and Reddy, 2001; Meyvis and Janiszewski, 2004). Bottomley and Holden (2001) replicated Aaker and Keller's model (1990) of consumer evaluations of brand extensions and provisionally concluded that focus on either or both of perceived quality of the parent brand and perceived fit between the parent brand and the extension were the two major alternatives for the success of a proposed brand extension.

Reviewing the product categories for human consumption, researchers have done significant work on “utilitarian” and “hedonic” aspects, attempting to quantify these two major dimensions of product relevance (Batra and Ahtola, 1990; Babin, Darden, and Griffin, 1994; Spangenberg, Voss, and Crowley, 1997; Voss, Spangerberg, and Grohmann, 2003).

The former is the traditional notion of instrumental or utilitarian performance whereby the product is seen as performing a useful function. The latter dimension is that of hedonic or aesthetic performance whereby products are valued for their intrinsically pleasing properties.

On these bases, consumers’ choice will be driven by utilitarian and hedonic considerations toward the proposed extension (Holbrook and Hirschman, 1982).

Hedonism and utilitarianism are not necessary two ends of a purely objective, one- dimensional scale (Voss, Spangenberg, and Grohmann, 2003). In most situations, the

difference between the utilitarian and hedonic may be a matter of degree and perception. The same product may be utilitarian to some and hedonic to others (Okada, 2005). Taking the consumers’ choice among new automobiles for example, they may care about utilitarian aspects (e.g., gas mileage, speed, safety) or care about hedonic attributes (e.g., sporty design, fashion) (Dhar and Wertenbroch, 2000). Addis and Holbrook (2001) have argued at length for a conceptualization based on shades of gray; the relative balance of hedonic and utilitarian benefits in the consumption experience. Based on these perspectives, this research will capture a hedonic/utilitarian value ratio as a moderator for the brand extension evaluations that has never been conducted in current study. Hence, this could produce valuable insight germane to the development of better strategies.

We postulate distinct and significant effects of the hedonic and utilitarian natures of the proposed extension on the brand evaluation. In short, this study seeks to identify and clarify a specific moderator—hedonic/utilitarian value—that significantly influences the effects of perceived quality, perceived fit, and consumers’ knowledge on extension evaluations.

Background and Hypotheses

Hedonic/Utilitarian Value

In recent years, researchers have done significant work on these two major dimensions of product relevance, attempting to quantify these “hedonic” and “utilitarian” aspects (e.g., Batra and Ahtola ,1990; Voss, Spangerberg, and Grohmann, 2003). This first, utilitarian, aspect corresponds to the traditional notion of instrumental or utilitarian performance, in which products are seen as performing useful functions. The second, hedonic aspect can be thought of as aesthetic performance, in which products are valued for intrinsically pleasing properties, apart from those afforded by their utility.

Generally speaking, to judge the hedonic value of a product, consumers are inclined to rely heavily on peripheral cues, such as brand awareness, non-product-related attributes, and

experiential and perceived symbolic benefits (e.g., user imagery, brand personality, sensory pleasure, value-expressiveness, etc.) rather than using concrete attributes. This is done via affective elaboration on the messages to form appraisals of the product (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Johar and Sirgy, 1991).

Conversely, with utilitarian value, consumers can obtain available and useful information about the extension product’s concrete features via literature and direct inspection to judge the quality. Consumers considering an inherently utilitarian product involve themselves in an advertising message and the message argument by cognitively elaborating on that message (i.e., issue-relevant thinking). These consumers are likely to focus on product-related attributes and functional benefits in the message appeals, e.g., the quality, function, performance, features, and so on (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Johar and Sirgy, 1991).

Moderating Effect of the Hedonic/Utilitarian Value on Perceived Quality

A review of the literature highlights the important role of perceived quality of the parent brand in the consumer’s evaluation of the brand extension. This earlier research has

supported the view that parent brand quality positively impacts extension evaluations (Pitta and Katsanis, 1995; Bottomley and Holden, 2001). However, none of it has ever specifically discussed moderation effects on perceived quality, applied to the evaluation of a brand extension.

Research suggests that both utilitarian and hedonic components of product evaluation influence consumers’ affective experiences and product satisfaction (Batra and Ahtola, 1990;

Mano and Oliver, 1993; Babin and Attaway, 2000). Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001, 2002) supported a positive correlation of hedonic value to brand affect, where brand affect is defined as a brand’s potential to elicit a positive emotional response in the average consumer as a result of brand product use. Products possessing hedonic value have a higher potential

for eliciting emotional responses, including like/dislike, love/hate, anger/joy,

sadness/happiness, and so on (Holbrook and Batra, 1987). Hedonic consumption designates those facets of consumer behavior related to the multi-sensory, fantasy and emotive aspects of one’s experience with products (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). Based on the

Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) theory (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986), when a product is perceived as hedonic in nature, consumers may focus on more peripheral messages—non- tangible product attributes and experiential and symbolic benefits (such as fun, pleasure, prestige, excitation, and joy), and less on the utilitarian messages—product-related attributes (such as features, quality, etc.); thereby, we can infer that hedonic value may distract

consumers from focusing on the importance of the parent brand’s perceived quality.

In contrast, for products possessing a predominantly utilitarian aspect, consumers’

behaviors are driven by instrumental and goal-oriented needs, in which they focus on accomplishing practical issues, such as function, effectiveness, practicality, and necessity (Strahilevitz and Myers, 1998; Voss et al., 2003). Consumers will adopt the central route to persuasion (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). The central route suggests that consumers are likely to focus on the finer points in the message, e.g., the quality of argument. Therefore, the effect of perceived quality on extension evaluation may be strengthened when the utilitarian value in the product category is high (Holbrook and Hirschman, 1982; Dhar and Wertenbroch, 2000).

In conclusion, the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value can be expected to moderate consumers’ evaluations of extensions. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: With the higher ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between perceived quality of the parent brand and extension evaluations will be attenuated.

Moderating Effect of the Hedonic/Utilitarian Value on Perceived Fit

Drawing primarily on categorization theory, prior studies propose that the degree to

which a parent brand associations are transferred to an extension depends on the level of perceived fit or degree of relatedness between the extension category and the parent brand (see, e.g., Aaker and Keller, 1990; Smith and Park, 1992). Categorization theory holds that people organize objects or information into categories that enable them to process and understand their environment efficiently (Rosch and Mervis, 1975). Perceived fit of product similarity is the degree to which components of the parent’s product categorization (i.e., attributes, features, usage, and manufacturing process) comfortably transfer to the proposed extension categories (Boush and Loken, 1993; Barsalou, 1983). Many researchers (e.g., Aaker and Keller, 1990; Park, et al., 1991; Smith and Park, 1992; Loken and John, 1993) have argued that consumers view a brand extension as an exemplar of the parent brand category. These researchers propose that the degree to which brand associations are transferred to an extension depends on the level of perceived fit or degree of relatedness between the extension category and that of the parent brand. Empirical evidence from a number of studies confirms that high fit is related to more positive extension evaluations (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Boush and Loken, 1991; Bottomley and Holden, 2001). Those researchers are inclined to adopt a categorization theory in which people perceive extensions categorically.

According to the aforementioned ELM theory, consumers having heightened hedonic expectations for a product are more inclined to respond to peripheral message cues (Johar and Sirgy, 1991). Hedonic consumption refers to consumers’ multi-sensory images, fantasies, and emotional arousal in using (in our case) an extension product. As hedonic usage is more affective and experiential, the importance of perceived fit between the extension and the parent brand could be attenuated since consumers are expecting fantasies, feelings, and fun from the extension (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982). In contrast, there is a reasonable expectation that utilitarian usage is more inclined to take into account categorical

considerations; considerations of fit. For example, if Sony endeavored to launch a new product line of video games, consumers would perhaps be more concerned with whether the video games are fun, interesting, and exciting or not. The perceived fit with Sony’ core products—non-gaming home electronic equipment—would be less important in their minds.

Hence, it is here posited that the higher the balance of hedonic/utilitarian value, the less the importance of perceived fit. Stated formally;

H2: With the higher ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between perceived fit and extension evaluations will be attenuated.

Moderating Effect of Hedonic/Utilitarian Value on Consumer Knowledge

Consumer knowledge is of key importance when evaluating brand extensions (Flynn and Goldsmith, 1999). Brucks (1985) describes three categories of consumer knowledge:

Subjective knowledge, i.e. what consumers think they know; objective knowledge, i.e. actual knowledge constructs measurable by some sort of test; and prior experiences with the product category. The benefit of this breakdown is that subjective knowledge has been shown to be a stronger motivation of purchase-related behaviors than objective knowledge. Subjective knowledge has typically been measured in terms of subjects’ claims to knowledge of a product or product domain (Bruck, 1985).

A subjectively knowledgeable consumer will make those choice decisions more easily and confidently than consumers without this knowledge. When an extension object is generally favorably evaluated, there exists an additional positive relationship between consumer knowledge and brand extension evaluations (Gronhaug et al., 2002). For example, if a consumer claims knowledge about the video games product category, when Sony extends into a new video game product line, and that extension is generally favorably evaluated, the knowledgeable consumer will have more confidence to accept this new product or to make a trial than the consumer who makes no claim to special knowledge.

Consideration will now be given to the moderating effect of the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value on this positive relationship when the extension evaluation is favorable. Park and Lessig (1981) found evidence that confidence in the decision was significantly lower for low-familiarity subjects (consumers) relative to high-familiarity subjects. When the situation makes it difficult for consumers to justify consuming the product, they are less likely to consume goods that perceived as largely hedonic (Okada, 2005). Accordingly, when low- familiarity consumers perceive a high hedonic/utilitarian value ratio, they will be more likely to avoid consumption. Despite this, it should be easier for people to consume goods that are more hedonic when the justification is facilitated (Okada, 2005). Subjectively knowledgeable people possess self-confidence that facilitates their consumption justification. Accordingly, these knowledgeable people tend to be an exception to the rule, and are more likely to accept the object, in spite of the higher ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value.

The above discussion can be applied to the case of product extensions. It is reasonable to expect that the positive relationship of consumers’ knowledge to the extension evaluation will be strengthened when the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value is higher. On the basis of the literature review, our next hypothesis is:

H3: With a higher ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between consumers’ knowledge of the extension-product class and extension evaluations will be strengthened.

Extension Evaluations and Purchase Intention

Attitudes—generally defined as a general and enduring positive or negative feeling about some person, an object, or idea—have served as independent variables in studies examining purchasing behavior (Morris et al., 2002). Other researchers have found that affective- and cognitive-based attitudes play significant mediating roles between the stimuli and purchase intention (Sweeney and Wyber, 2002; Olney, Holbrook and Batra, 1991). These research

findings can be extended to the realm of product extensions, as well; extension attitudes will be significant and positive predictors for purchase intention.

Based on select article reviews, (Klink and Smith, 2001; Martin and Stewart, 2001;

Barone et al., 2000), we find out that extension evaluation has been regarded as synonymous with extension attitude (as measured by subjective feeling and favorability toward the extension). Hence, we take the same viewpoints and regard extension evaluations as cognitive and affective-based attitudes. Given the body of research that distinctly links attitude to purchase intension, we go on to infer that the more favorable the extension evaluation, the higher the probability the customer will purchase. Therefore, we posit that extension evaluation is an antecedent of purchase intention. So,

H4: Purchase intention toward the extension is positively indicated for extension evaluation.

Methodology

Parent Brands and Extensions Selection

Three hypothetical extensions for each of two actual brands were chosen for use in the main study. By definition for this study, examination of brand extensions requires that (1) the parent brand names are well known, (2) these parent brands are reputable, and (3) that for reasons of product class coverage, they are not operational in the same product categories (Klink and Smith, 2001). A pretest1 was conducted to generate candidate brands. We held a focus group composed of fifteen undergraduate students to discuss the matter of identifying salient brands according to the abovementioned selection criteria. Finally, the brand names Nokia, Acer, Nike, and Swatch were selected.

Pretest2 took the form of another focus group composed of twenty undergraduate students, assembled to select the final two target brands from those brands obtained by the pretest1, and generate the three proposed extensions for each of these two brands. We asked a

sample of 30 undergraduate students, similar in composition to that used in the prior pretest study, to fill out a survey, looking at the list of four establish brands, and expressing product and extension interest and purchase intention in a free-associating way. There were two questions in this focus group. The first was, “Which brand would be your favorite to extend?”

The other was, “Which brand extension would attract your attention and increase your purchase intention?” This process resulted in the selection of the final two parent brands and proposed extensions, which will be described below.

Main Study Subjects

The main study recruited 315 subjects from the body of undergraduate business students at the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (NTUST) and the National Chinyi Institute of Technology (NCIT). The average age of the subjects was 21 years; 17 percent were male and 83 percent were female.

Main Experiment Design and Procedure

The main study used this 23 between-subjects experimental design, that is, two actual brands (Nokia and Swatch) and three hypothetical extensions, resulting in six treatment groups. The treatment groups were (1) Nokia PDA, (2) Nokia motorcycles, (3) Nokia video games, (4) Swatch alarm clocks, (5) Swatch PCs, and (6) Swatch theme restaurants. The 315 subjects were each randomly assigned to one of the six treatment groups.

Subjects were seated in one of six separate conference rooms, a room for each treatment group. After about 10 minutes for general instructions, subjects received one of six booklets.

On the first page of the booklet, subjects were informed of the purpose of the study; to generate useful information that could help Nokia and Swatch to launch new products. Later, all subjects filled out a questionnaire to collect salient information for this research. When all subjects finished their questionnaires, they could take their free gift on their way out. Note that fifteen subjects failed to complete major portions of the questionnaire, leaving an

effective sample of 300 subjects.

Development of Measures

Hedonic/utilitarian value. The testing methodology used to measure the product value type was adapted from Batra and Ahtola (1990), Babin, Darden and Griffin (1994), and Voss et al., (2003). The test asks subjects to rank four product attributes on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with the midpoint 4 being neutral. The utilitarian aspect of a product was gauged using two of the attributes (necessary, and practical), while the other two (interested, happy) measured the hedonic aspect.

Perceived quality. As discussed previously, perceived quality is a measure of consumers’

subjective judgment about a brand’s overall excellence or superiority and addresses overall quality rather than individual elements of quality. For this study, a five-item metric based on Dodds et al.’s research (1991) and Yoo et al.’s (2000) work measures perceived quality They marked their responses on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree) with the midpoint 4 being neutral.

Perceived fit. Our method for measuring perceived fit was adapted from Smith and Park, (1992), Smith and Andrews (1995), and Klink and Smith (2001). This construct was

measured by asking subjects to provide similarity assessments between the parent brand and the extension in terms of the four following characteristics: (1) product category, (2)

manufacturing processes, (3) usage situations, and (4) product functions. These were measured via responses to questionnaire items on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly not similar) to 7 (strongly similar).

Consumers’ knowledge of the extension-product class. Referring to prior work in this area (Smith and Park, 1992; Smith, 1992; Park et al., 1994; Gronhaug et al., 2002), consumers’

knowledge of the extension-product class was measured by asking respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with fours items of statements regarding their knowledge of the

relevant product categories on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Extension evaluation. We measured the extension evaluation by asking subjects to indicate (1) how favorable they felt toward the extension (from “not very favorable” to “very

favorable”), (2) their evaluation of extension quality (from “very bad” to “very good”), and (3) the likelihood of future involvement with the extension (from ”not very likely” to “very likely”); again, consistently using the 7-point scale (Barone et al., 2000; Klink and Smith, 2001).

Purchase intention. Purchase intention for the extension is defined as the likelihood that the buyer will purchase the extension (Dodds et al., 1991). For this study, a three-item metric based on Dodds et al.’s study measures willingness to buy the extension. Subjects marked their responses on three seven-point scales ranging from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high) with the midpoint 4 being neutral. The three measured items were probability, willingness, and likelihood (see Table1).

Analysis and Results

Plan for Data Analysis

Three methods—Cronbach’s reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)—were used to assess and select the final items that would be employed for hypothesis testing. First, Cronbach’s reliability coefficient was calculated for the items of each higher-level construct (e.g. perceived quality). A coefficient of .70 is considered the cutoff level of reliability recommended for theory testing research (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). Items that did not significantly contribute to the reliability would be eliminated in the interests of parsimony. In our results, all items met or exceeded the .70 cutoff. All 26 items were retained for the seven constructs; five for perceived quality.

four for perceived fit, four for consumer’s knowledge, two for hedonic value, two for

utilitarian value, three for extension evaluation, and three for purchase intention. Seven constructs’ Cronbach reliability coefficients all exceed .70.

Second, EFA was then applied to determine whether the items in fact aggregated around their proposed factors, and whether the individual items are loaded on their appropriate factors as intended. Factor analysis with a varimax rotation technique was conducted on all measured items, and as expected, seven distinct factors were found.

Finally, CFA was used to assess the construct items more rigorously, based on the correlation matrix of the items. Specifically, CFA was used to detect the unidimensionality of each construct (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). This unidimensionality check verifies the validity and reliability of our seven constructs. PRELIS was used to generate the correlation matrix, and the LISREL 8.3 maximum-likelihood method was used to produce a completely standardized solution (Joreskog and Sorbom, 1993).

Measurement of Properties of the Scales

The CFA was used to measure seven latent constructs in the model, and the results are provided in Talbe1. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (ρc) are also provided. The assessment of the measurement properties of all seven constructs indicated that the factor loadings (lambdas) were high and significant (the t values for the loading ranged from 6.83 to 26.94, all being greater than 4.63), which satisfies the criteria for convergent validity (Simonin, 1999). Content validity was established through a literature review and by consulting experienced researchers and managers.

Discriminant validity is evidenced, in that no confidence interval (± two standard errors) around the correlation estimates for the 21 pairs of latent variables included 1.0 (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The highest was for extension evaluation and purchase intention (r = . 88± 2 .02). Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested that discriminant validity also could be assessed by determining whether the AVE estimates for two constructs are greater than the

square of the parameter estimate between them (standard Φ2). In this case, all seven measured constructs met this criterion.

Fornell and Larcker (1981) also stressed the importance of examining composite reliability and average variance extracted. Bagozzi and Yi (1988) suggested two criteria:

Composite reliability (ρc) should be greater than or equal to .60, and AVE should be greater than or equal to .50. For this study, all seven composite reliabilities (ρc) were greater than . 71, and all AVE figures exceeded .56. There was an overall statistical fit of the measurement model (2(209) = 491.23), RMR, SRMR, and RMSEA were all lower than .07; and the indexes of NFI, NNFI, IFI, CFI, and GFI all exceeded .86. These indicated a reasonable level of fit in favor of the model (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Hypotheses Tests

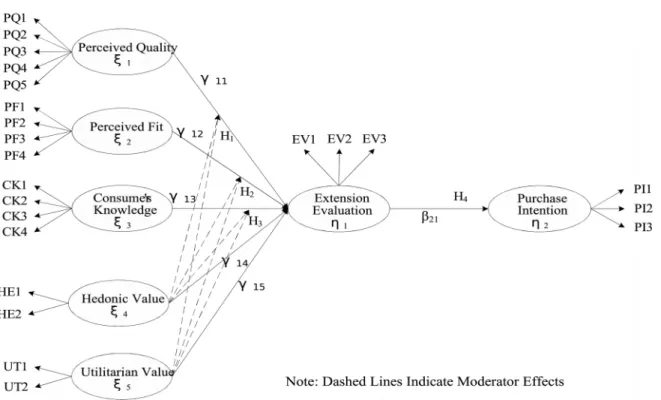

The fit of structural model. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to estimate parameters of the structural model shown in Figure 1, and the completely standardized solutions computed by the LISREL 8.3 maximum-likelihood method are reported in Table 2 (full sample) and Table 3 (two groups). The structural model specified the perceived quality (ξ1), perceived fit (ξ2), consumer’s knowledge (ξ3), hedonic value (ξ4), and utilitarian value (ξ5) as the exogenous constructs. The exogenous constructs were selectively related to one endogenous mediating construct (extension evaluation as η1), which was related to the last endogenous construct, purchase intention, as η2. There were overall statistical fits of two measurement models (see Table 2 and Table3). These indicated a reasonable level of fit in favor of two models (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Testing moderating effects of hedonic/utilitarian value on extension evaluations. To investigate the moderating effects of hedonic/utilitarian value, this study applies the multiple- group analyses. Baron and Kenny (1986) explained that for testing moderating effect, “the levels of the moderator are treated as different groups.” Hence, we divide the

hedonic/utilitarian construct values taken from the subject responses into high value and low value groups. These high and low value groups were based on a mean split of 1.0074, with values ranging from .17 to 4.00.

In order to investigate the moderating effects of hedonic/utilitarian value on extension evaluations, we first clarify and test three antecedents—perceived quality, perceived fit, and consumer’s knowledge—that dominate consumers’ evaluations of brand extensions. An analysis of the moderating effect of hedonic/utilitarian value, Table 3 shows that the causal path from perceived quality to extension evaluation is positively significant in the low value group (γ11= .39, t = 6.18*). Conversely, this path is not significant in the high value group (γ11= .12, t = 1.33). Thus, H1 is supported. For the low hedonic/utilitarian value group, the causal path from perceived fit to extension evaluation is also positively significant (γ12= .49, t

= 7.29*) while this causal path is not significant (γ12= .01, t = 0.09) in the other group. Thus, H2 is supported.

Then, we test the moderating effect of the hedonic/utilitarian value on consumer’s knowledge. Respecting the moderating effect of the hedonic/utilitarian value, Table 3 also shows that the causal path from consumers’ knowledge to extension evaluation is positively significant in the low value group (γ13= .16, t = 2.42*) and this path is also positively

significant in the high value group (γ13= .66, t = 5.97*). Furthermore, we undertook the χ2 difference test for examining γ13 change between these two groups. It appears that the χ2 difference for a change in one degree is significant for the moderating variable (∆χ2 =27.20,

∆df = 1). The result implies that the γ13 for the high hedonic/utilitarian value group is significantly larger than for the low hedonic/utilitarian value group. Thus, H3 is supported.

These results indicate that with higher ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between consumer’s knowledge of the extension-product class and extension evaluations will be strengthened.

Testing the effect of extension evaluation on purchase intention. As can be seen in Table 2, the causal path from extension evaluation to purchase intention is significant (β21= .89, t = 17.37*). This result verifies that purchase intention toward the extension is positively

indicated for extension evaluations. Thus, H4 is supported. These results and others are further described in the General Discussion section that follows.

General Discussion

Summary

The current research refers to prior work and adds to the growing body of literature by examining how antecedent states of consumers affect their responses to proposed extensions.

Up to now, there’s been very little research investigating the direct effects of product value (hedonic/utilitarian) on extension evaluation, and no examination of the effects of value as a moderator. Here, we further explore both direct and moderating effects of perceived quality of the parent brand, perceived fit between the parent brand and the proposed extension, and consumers’ knowledge of the extension-product class on brand extension evaluations, which in turn influence purchase intention toward the extension. In particular, this study lends special focus to the moderating impact of hedonic/utilitarian value on brand extension evaluations that have now been discussed and verified by prior research.

As expected, the findings indicate that there are direct, positive effects of perceived quality, perceived fit, and consumers’ knowledge on extension evaluation (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Klink and Smith, 2001; Smith, 1992; Gronhaug and Lines, 2002). The positive

relationship between perceived fit and customer evaluation of brand extensions is one of the best-supported findings in brand extension research. Our results are in accordance with Bottomley and Holden (2001)’s findings based on their secondary analyses in eight studies.

Meanwhile, we mainly focus the discussion on the important finding about the role of

the balance of hedonic/utilitarian value on extension evaluations. This study has produced evidence to support H1, H2, and H3. These findings shed new light on a moderating effect of the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value on brand extension evaluations. Hedonic and

utilitarian values not only play important direct, antecedent roles in extension evaluation, but also play these moderating roles as well. Thus, with greater (lesser) ratios of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between perceived quality and extension

evaluations is attenuated (strengthened). With greater (lesser) ratios of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between perceived fit and extension evaluations is also attenuated (strengthened). Conversely, another important finding is that with greater (lesser) ratios of hedonic to utilitarian value, the positive relationship between consumers’ knowledge and extension evaluations is strengthened (attenuated). This means that there is a positive interaction between consumers’ knowledge and the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value.

With respect to these moderating effects, our findings indicate that the greater (lesser) the ratio of hedonic/utilitarian value possessed by the extension, the smaller (larger) the effect of perceived quality and perceived fit on its evaluation (see Table 3). Based on the antecedent analysis of the extension evaluations (see Table 2), the results also reveal that the higher the levels of hedonic value of the extension, the more favorable will be its evaluation (γ14 =.35*).

Conversely, higher levels of utilitarian value will lead to less favorable evaluations (γ15= -0.13). Hence, hedonic and utilitarian values play key roles in the process of extension evaluation. To the best of our knowledge, prior research has not examined these moderating effects. Accordingly, the results presented here concerning these effects on extension evaluation offer a unique contribution to the literature.

Implications for Business

These findings have important implications for both academic research and practical business management. The conceptualization guiding the present investigation provides a

useful framework for managers developing tactics for predicting—and perhaps even

enhancing, via hedonic-focused promotion—consumers’ evaluations of brand extensions. In summary, positive extension evaluations are indicated for hedonic value and negative

extension evaluations are indicated for utilitarian value for direct, causal reasons. At the same time, however, the ratio of hedonic to utilitarian value attenuates the effect of perceived quality and perceived fit on extension evaluations, for mediating reasons. Therefore, the hedonic/utilitarian characteristics possessed by the extension plays the key, strategic role in brand extension promotion strategies.

Actually—and especially in view of these moderating aspects—this is the most important and valued finding of this research. If a company’s parent brand is saddled with low perceived quality or low perceived fit, they might nonetheless be able to undertake a brand extension strategy where the proposed extension possesses high levels of hedonic value. The positive antecedent effect of hedonic value on extension evaluation (see Table 2,

γ14 =.35*) more than makes up for its attenuating moderating effect on perceived quality and perceived fit (see Table 3, γ11=.12, γ12 =.01). At the same time, a company blessed with high- perceived quality of its parent brand and high perceived fit can afford to employ an extension strategy that is highly utilitarian. The high utilitarian value of the extension will strengthen the effect of perceived quality and perceived fit on its evaluation (see Table 3, γ11=.39*, γ12

=.49*). This more than compensates for the negative antecedent effect of the utilitarian value on the extension evaluation (see Table 2, γ15 = -0.13*).

To summarize, the product value (hedonic/utilitarian) is a very important factor. Taking into account both direct and indirect (modulating) effects, it can be a strategic tool for crafting effective brand extension promotional campaigns, with positive downstream effects on purchase intention.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

As noted, there is no universally accepted conceptualization or measure of fit. Although this study applied a widely accepted construal and measure of perceived fit, it would

nonetheless be useful to see how other constructs, such as brand image fit (Bhat and Reddy, 2001), concept consistency (Park et al., 1991; Martin and Stewart, 2001), psychological view of similarity (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994), and so on could be adapted to the methods presented here. If knowledge in this area is to progress in a meaningful manner, it would be useful to arrive at some consensus about how to define and measure the perceived fit

construct. The second issue is related to hedonic and utilitarian value. Two items for hedonic value and two items for utilitarian value may be not enough to deliberately address these two constructs. Thus, we suggest that the Cronbach’sαcan be improved by adding more

measured items adapted from prior research (Voss et al., 2003; Batra and Ahtola, 1990; Mano and Oliver, 1993).

A potential limitation associated with our research involves the question of product category coverage reflected in the pretest final selection of our two actual brands, Nokia and Swatch. Both these brands have high technology associations, albeit in different sub domains

—communications electronics vs. timepiece engineering. Resultantly, these conclusions may not comprehensively scale to all business types. Further research should investigate brands from a broader range of types. Also, as we were dealing with a homogeneous subject base of adult students, the usual caveats that accompany the use of samples hold here as well.

Table 1

Scale items and measurement prosperities

Item Standardized

Loading t Value αb Perceived Quality(ρc= .82; AVE = .57)a

PQ1 The likely quality of Xc is extremely high.

PQ2 The likelihood that X is reliable is high.

PQ3 I recognized the X style.

PQ4 The likelihood that X is durable is high.

PQ5 The likely quality of X is extremely low. (r)d

.86 .91 .54 .67 .40

- 18.62

9.71 12.86 6.83

.80

Perceived Fit (ρc= .86; AVE = .67)

How similar are X core product and X brand extension in terms of the following characteristics: (1 is “Not very similar” and 7 is “Very Similar”)

PF1 Product category PF2 Manufacturing processes PF3 Usage situations PF4 Product functions

.

.87 .84 .80 .57

- 16.98 15.99 10.36

.86

Consumer’s Knowledge (ρc= .83; AVE = .72) CK1 I feel very knowledgeable about this product.

CK2 If I wanted to purchase this product today, I would need to gather very little information in order to make a wise decision.

CK3 If friends asked me about this product, I could give them advice about different brands.

CK4 I could compare individual product features over a variety of brands.

.63 .59 .82 .86

- 8.58 10.88 11.06

.82

Hedonic Value (ρc= .72; AVE = .73)

HE1 I feel interested when I use this product.

HE2 I feel happy when I use this product. .69

.79. -

8.05 .71

Utilitarian Value (ρc= .82;AVE = .81) UT1 This product is necessary for me.

UT2 This product is practical for me .72

.93

- 7.69

.80

Extension Evaluation (ρc= .88; AVE = .78)

EV1 How favorable do I feel toward this product?

EV2 How is this product quality?

EV3 How likely I will have a trial of this product?

.86 .83 .81

-17.62 17.08

.87

Purchase Intension (ρc= 93; AVE = .86)

PI1 The probability that I would consider buying this product is: (very low to very high)

PI2 My willingness to buy this product is: (very low to very high) PI3 The likelihood of purchasing this product is: (very low to very high)

.92 .93 .85

-26.94 21.52

.93

Goodness-of Fit

2 (df=209)= 491.23 CFI= .92 IFI= .93 RMSEA= .067 NFI= .88 GFI= .87 RMR= .066 NNFI= .91 RMSEA= .067

a For each construct, scale composite reliability (ρc) and average variance extracted (AVE) are provided. These are calculated using the formula provided by Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Baggozzi and Yi (1988).

b Cronbach’s α (α) means internal consistency.

CX= the focal brand

d(r)= reverse-coded

Table 2

Structural parameter estimates and goodness-of-fit indices

(Full Sample)

Paths Estimatea t− Value

Perceived quality ===> Extension Evaluation γ11 0.29 5.26*

Perceived Fit ===> Extension Evaluation γ12 0.31 5.76*

Consumer’s Knowledge ===> Extension Evaluation γ13 0.22 3.13*

Hedonic Value ===> Extension Evaluation γ14 0.35 4.71*

Utilitarian Value ===> Extension Evaluation γ15 -0.13 -2.20*

Extension Evaluation ===> Purchase Intension β21 0.89 17.37*

NFI = .88 NNFI= .91 CFI = .92 IFI = .92 GFI= .88

RMSEA = .067 Sample size = 300

RMR = .067 SRMR = .067 χ2(df=214) = 497.01 CN=200.63 (>200)

a Standardized estimate

*Significant at p< .05 (t > 1.96 or t< -1.96)

Table 3

Structural parameter estimates and goodness-of-fit indices for two-group comparison on hedonic/utilitarian value

Hedonic/Utilitarian Value High (n=100)

Hedonic/Utilitarian Value Low (n=200) Paths Estimatea t− Value Estimatea t− Value Perceived quality ===> Extension evaluation γ11 .12 1.33 .39 6.18*

Perceived fit ===> Extension evaluation γ12 .01 .09 .49 7.29*

Consumers’ knowledge ===> Extension evaluation γ13 .66 5.97* .16 2.42* (S*) NFI = .85

NNFI= .92 CFI= .93 IFI = .93

RMSEA = .068 SRMR = .071

χ2(df=310) = 522.72

a Standardized estimate

*Significant at p< .05 (t > 1.96 or t< -1.96)

S*= supported (coefficient change is tested byχ2 difference test)

Figure 1. Conceptual Model

References

1. Aaker, D. A. (1991), Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name, New York: The Free Press.

2. ---- (1996), “Measuring brand equity cross products and markets”, California Manage Review, 38, pp. 102-120.

3. ----and Keller, K. L. (1990), “Consumer evaluations of brand extensions”, Journal of Marketing, 54, pp. 27-41.

4. Addis, M. and Holbrook, M. B. (2001), “On the conceptual link between mass customisation and experiential consumption: an explosion of subjectivity”, Journal of Consumer Research, 1, pp. 50-66.

5. Anderson, J. C., Gerbing, D. W. (1998), “Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach”, Psychological Bulletin, 103, pp. 411-423.

6. Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R. and Griffin, M. (1994), “Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value, Journal of Consumer Research, 20, pp. 644-656.

7. ---- , Attaway, J. S. (2000), “Atmospheric affect as a tool for creating value and gaining share of customer”, Journal of Business Research, 49, pp. 91-99.

8. Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (1988), “On the evaluation of structural equation models”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, pp. 74-94.

9. Baron, R. M. and Kenny, D. A. (1985), “The Moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, pp.1173

10. Barone, M. J., Miniard, P. W., and Romeo, J. B. (200), “The influence of positive mood on brand extension evaluations”, Journal of Consumer Research, 26, pp. 386-400.

11. Barsalou, L. W. (1983), “Ad hoc categories”, Memory and Cognition, 11, pp. 211-227.

12. Batra, R. and Ahtola, O. T. (1990), “Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes”, Marketing Letters, 2, pp.159-170.

13. Bhat, S. and Reddy, S. K. (2001), “The impact of parent brand attribute associations and affect on brand extension”, Journal of Business Research, 53, pp. 111-122.

14. Bottomley, P. A. and Holden, S. J.S. (2001), “Do we really know how consumers evaluation Brand extensions? Empirical generalizations based on secondary analysis of eight studies”, Journal of Marketing Research, 38, pp. 494-500.

15. Boush, D. M. and Loken. B. (1991), “A process-tracing study of brand extension evaluation”, Journal of Marketing Research, 28, pp. 16-28.

16. Broniarczyk, S. M. and Alba, J. W. (1994), “The importance of the brand in brand extension”, Journal of Marketing Research, 31, pp. 214-228.

17. Brucks, M. (1985), “The effect of product class knowledge on information search behavior”, Journal of Consumer Research, 12, pp. 1-16.

18. Chaudhuri, A. and Holbrook, M. B. (2001), “ The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty”, Journal of Marketing, 65, pp. 81-93.

19. Chaudhuri, A. and Holbrook, M. B. (2002), “Product-class effects on brand commitment and brand outcomes: The role of brand trust and brand affect”, Brand Management, 10, pp. 33-57.

20. Dhar, R. and Wertenbroch, K. (2000), “Consumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods”, Journal of Marketing, 37, pp. 60-71.

21. Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., and Grewal, D. (1991), “Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations”, Journal of Marketing, 28, pp. 307-319.

22. Flynn, L. R. and Goldsmith, R. E. (1999), “A short reliable measure of subjective knowledge”, Journal of Business Research, 46, pp. 57-66.

23. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, 18, pp.

39-50.

24. Gronhaug, K., Hem, L., and Lines, R. (2002), “Exploring the impact of product category risk and consumer knowledge in brand extension”, Journal of Brand Management, 9, pp. 463-476.

25. Hirschman, E. C. and Holbrook, M. B. (1982), “Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods, and propositions”, Journal of Marketing, 46, pp. 92-101.

26. Holbrook, M. B. and Batra, R. (1987), “Assessing the role of emotion as mediators of consumer responses to advertising”, Journal of Consumers Research, 14, pp. 404-420.

27. Holbrook, M. B. and Hirschman, E. C. (1982), “The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun”, Journal of Consumer Research. 9, pp. 132-140.

28. Hu, L. and Bentler, P. M. (1999), “Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in conventional criteria versus new alternatives”, Structural Equation Modeling, 6, pp. 1-55.

29. Johar, J. S. and Sirgy, M. J. (1991), “Value-expressive versus utilitarian advertising appeals: when and why to use which appeal”, Journal of Advertising, 20, pp. 23-33.

30. Joreskog, K. G. and Sorbom, D. (1993), LISREL 8.02, Chicago: Scientific Software International.

31. Klink, R. R. and Smith, D. C. (2001), “Threats to the external validity of brand extension research”, Journal of Marketing Research, 38, pp. 326-335.

32. Loken, B. and John, D. R. (1993), “Diluting brand beliefs: when do brand extensions have a negative impact?”, Journal of Marketing, 57, pp. 71-84.

33. Mano, H. and Oliver, R. L. (1993), “Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction”, Journal of Consumer Research, 20, pp. 451-466.

34. Martin, I. M. and Stewart, D. W. (2001), “The differential impact of goal congruency on attitudes, intentions, and the transfer of brand equity”, Journal of Marketing Research, 38, pp. 471-484.

35. Meyvis, T. and Janiszewski, C. (2004), “When are broader brands stronger brands? An accessibility perspective on the success of brand extension”, Journal of Consumer Research, 31, pp. 346-357.

36. Morris, J. D., Woo, C., Geason, J. A., and Kim, J. (2002), “The power of affect:

Predicting intention”, Journal of Advertising Research, 42, pp. 7-17.

37. Nunnally, J. C. and, Bernstein, I. H. (1994), Psychometric Theory. 3d ed., New York:

McGraw-Hill.

38. Okada, E. M. (2005), “Justification effects on consumer choice of hedonic and utilitarian goods”, Journal of Marketing Research, 42, pp. 43-53.

39. Olney, T. J, Holbrook, M. B, and Batra, R. (1991), “Consumer responses to advertising:

The effects of ad content, emotions, and attitude toward the ad on viewing time”, Journal of Consumer Research, 17, pp. 440-445.

40. Park, C. W, Milberg, S., and Lawson, R. (1991), “Evaluation of brand extensions: The role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency”, Journal of Consumer Research, 18, pp. 185-193.

41. Park, C. W. and Lessig, P. V. (1981), “Familiarity and its impact on consumer decision biases and heuristics”, Journal of Consumer Research, 8, pp. 223-230.

42. ----, Mothersbaugh, D. L., and Feick, L. (1994), “Consumer knowledge assessment”, Journal of Consumer Research, 21, pp. 71-82.

43. Petty, R. E. and Cacioppo, J. T. (1986), Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change, New York: Spring-Verlag.

44. Pitta, D. A. and Katsanis, L. P. (1995), “Understanding brand equity for successful brand extension”, The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12, pp. 51-64.

45. Rosch, E. H. and Mervis, C. B. (1975), “Family resemblances: studies in the internal structure of categories”, Cognitive Psychology, 7, pp. 573-605.

46. Simonin, B. L. (1999), “Transfer of marketing know-how in international strategic alliances: An empirical investigation of the role and antecedents of knowledge ambiguity”, Journal of International Business Studies, 30, pp. 463-490.

47. Smith, D. C. (1992), “Brand extensions and advertising efficiency: What can and cannot be expected”, Journal of Advertising Research, 32, pp. 11-20.

48. ----, Park, C. W. (1992), “The effects of brand extensions on market share and advertising efficiency”, Journal of Marketing Research, 29, pp.296-313.

49. ----, Andrews, J. (1995), “Rethinking the effect of perceived fit on customers’

evaluations of new products”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, pp.

115-121.

50. Spangenberg, E. R. and Voss, K. E., and Crowley, A. E. (1997) “Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of attitude: A generally applicable scale”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol 24, pp. 235-241.

51. Strahilevitz, M. and Myers, J. G. (1998), “Donations to charity as purchase incentives:

How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell”, Journal of Consumer Research, 24, pp. 434-446.

52. Sweeney, J. C. and Wyber, F. (2002), “The role of cognitions and emotions in the music-approach-avoidance behavior relationship”, The Journal of Services Marketing, 16, pp. 51-69.

53. Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., and Grohmann, B. (2003), “Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude’, Journal of Marketing Research, 40, pp.

310-320.

54. Yoo, B., Donthu, N., and Lee, S. (2000), “An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, pp. 195- 211.