行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

█

█

█

█ 成 果 報 告

成 果 報 告

成 果 報 告

成 果 報 告

□

□

□

□期中進度報告

期中進度報告

期中進度報告

期中進度報告

知識運用策略與危機管理策略之結盟對組織危機管理成效之

影響分析

計畫類別:

█

個別型計畫 □ 整合型計畫

計畫編號:NSC 96-2416-H-006-017

執行期間: 96 年 8 月 1 日至 97 年 7 月 31 日

計畫主持人:王 維 聰

共同主持人:N/A

計畫參與人員: 王 俊 傑、呂 育 誠、陳 群 樺

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):

█

精簡報告 □完整報告

本成果報告包括以下應繳交之附件:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告一份

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告一份

█

出席國際學術會議心得報告及發表之論文各一份

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告書一份

處理方式:除產學合作研究計畫、提升產業技術及人才培育研究計畫、

列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢

執行單位: 國立成功大學工業與資訊管理學系(所)

中 華 民 國 97 年 8 月 4 日

中文摘要 中文摘要 中文摘要 中文摘要: 現有之研究文獻顯示,各類的企業危機不僅對企業組織造成了很顯著的損害,某些 企業危機甚至導致了企業的衰亡。為了能得到更佳的企業危機管理成效,企業組織應該 以最有效的方式來運用其擁有的關鍵組織資源,例如知識。近年來,知識早已被認為是 對執行組織管理活動而言最重要的組織資源。作為一種組織資源,知識可以透過策略結 盟的方式,來與企業組識的危機管理任務產生關聯。儘管長期以來人們對於如何管理知 識與企業危機的議題,一直保有一定興趣,然而,僅有非常少、甚至可說是沒有人從事 有關知識相關策略與企業危機管理策略之策略結盟的研究。 本研究的目的,在於經由探討知識相關策略與企業危機管理策略的策略結盟,能如 何地幫助企業組織得到比以前更好的危機管理績效,來增進我們對知識管理與危機管理 相關議題的了解。本研究將運用由 Belardo、Chengalur-Smith、及 Pazer 所提出的企業危 機分類架構、以及由 Mitroff 所發展出來的危機管理模型,來幫助研究者專注於探討最 重要的危機管理觀點。此外,Zack 所提出的知識策略架構,將會被運用來幫助我们探 討在某一個特定種類的企業危機的每一個危機管理階段中,企業組織如何獲取具有關鍵 性的知識,來降低這些潛在企業危機的發生率以及對企業之潛在殺傷力。再者,本研究 也將採用 Venkatraman 所提出的”中介性”策略結盟觀點,來探討策略結盟的議題。根 據此策略結盟觀點的主張,知識策略將被視為一”中介物”,而能藉由直接增進企業危 機管理策略的執行成效,來間接地影響企業組織之績效。 本研究將採用深入個案分析的研究方法,來探究知識策略與企業危機管理策略的策 略結盟,能如何幫助企業組織更有效地利用它們的知識資源,並進而削減企業組織在管 理企業危機方面的弱點。本研究中所發展出來的知識策略與企業危機管理策略的策略結 盟架構,將可提供企業組織之高中階經理人一些策略性指導方針,來幫助他們在某一個 特定種類的企業危機的每一個危機管理階段中,界定何種知識才是他們真正需要的,以 及他們應如何管理這些知識,來管理其潛在的企業危機,進而避免危機的發生,或是當 危機已無法避免時,能盡可能地減低其造成之損失。 英文摘要 英文摘要 英文摘要 英文摘要:

Literature indicates that business crises are responsible for a great portion of the losses of organizations and some of them even have resulted in the demise of organizations. To acquire better crisis management results, it is proposed that organizations should make the best use of critical organizational resources, such as knowledge. Knowledge has been recognized as the most important organizational resource for performing management activities. As a resource, knowledge can be associated with crisis management tasks through alignment. Despite the interest in managing knowledge and business crises, there have been little or no studies about the alignment of knowledge-based strategy with crisis management strategy.

This study aims to enhance the current understandings on both knowledge management and crisis management by investigating how the alignment of knowledge-based strategies and crisis management strategies can lead to better crisis management performance of organizations. The crisis categorization framework developed by Belardo, Chengalur-Smith, and Pazer and the process-oriented crisis management model proposed by Mitroff are employed to focus on critical aspects of crisis management. In addition, the knowledge strategy framework developed by Zack and will be used to help identify knowledge appropriate to each crisis phase of a particular kind of business crisis. Furthermore, the alignment perspective of “fit as mediation” proposed by Venkatraman is adopted by treating knowledge strategies as mediators that can facilitate the enforcement of crisis management strategies and in turn affect organizational performance indirectly.

The approach of in-depth case study will be used in order to investigate how the alignment of knowledge strategy and crisis management strategy can help enterprises better use their knowledge resources, and in turn help them eliminate their vulnerability to business crises. The proposed alignment framework of knowledge strategy and crisis management strategy will benefit executives and managers of organizations by providing guidelines on identifying what knowledge they really need and determining how they can better manage the needed knowledge at each of the main phases of a particular business crisis if they were to prevent the business crisis or mitigate its impact once it does occur.

前言 前言 前言 前言: 目前已有許多學者專家針對預防企業危機的發生或是當它們發生時盡量減低其對 企業組織造成的損失這兩方面,發展出許多可做為管理人員之決策指導方針的危機管理 架構(e.g. Richardson, 1994; Salter, 1997)。然而,在這一類危機管理架構中,知識相關資 源 (例如: 員工之危機處理經驗、專家知識等等)的使用對危機管理成效的影響並沒有被 明確地加以探討與考慮。申請人從自身過往有關知識管理與危機管理結合的研究中,已 確認企業組織必須發展出一套有效的危機處理計劃及機制,以避免其潛在之企業危機對 其造成致命性的傷害。而申請人的過往研究結果也進一步地指出,一個企業是否能夠發 展出為其量身訂做的一套有效的危機處理計劃及機制,關鍵在於該企業是否能對所需的 知識有更充份地瞭解,並以更有效地方式運用及管理這些與其潛在企業危機相關的知 識。 為了進一步地加深人們對知識管理在管理企業危機的任務中扮演著什麼樣的角 色,本研究將從策略管理的觀點出發,來探討知識相關策略與危機管理相關策略的策略 結盟,對企業組織執行危機管理任務的表現,會有什麼樣的影響。換句話說,藉由本研 究,我們期望能了解一個企業組織,應該如何依據它的某一個潛在企業危機的特性與必 須執行的危機管理任務,來選用適當之知識相關策略,以便幫助它以最有效並且最有效 率的方法,來界定並獲取其管理該企業危機所真正需要的知識,並妥善地加以運用在預 防或是處理該企業危機的工作上,最終達到提高企業之危機管理成效的目的 研究目的 研究目的 研究目的 研究目的: 由於企業危機擁有”低發生率” (low frequency) 的獨特特質,使得企業經營者僅 擁有十分稀少的機會,來從中增加他們對其潛在企業危機的瞭解,並進一步學習如何更 有效地預防及處理這些潛在企業危機。這個現象告訴我們,在預防及處理潛在企業危機 這方面,一般企業中可能存在著極顯著的”知識缺口” (knowledge gaps)。所謂的”知 識缺口”,指的是一個企業或組織,為了要達成某一目標,所以必須擁有的知識與其目 前真正擁有的知識之間的差異 (Zack, 1999)。為了要關閉這些所謂的知識缺口,企業組 織必須設法界定出其營運上真正所需要、卻又尚未擁有的知識,然後再進一步思考如何 去獲得這些知識。由於企業危機隨著其種類的不同,而有著不同的特質,企業組織在面 對某一特定種類的企業危機時,在其每個危機處理階段,會需要運用不同的知識以及不 同的知識管理方法,來協助企業組織有效達成在該階段中最關鍵的階段性目標。由此可 推斷,在不同的危機處理階段中運用不同的知識管理方法來滿足企業不同的知識需求, 是有其必要的。因此,申請人相信,經由研究知識策略與危機管理策略的策略結盟,來 探討在不同種類之危機的各個危機處理階段中,該運用哪一些不同的知識策略,將會顯 著地減少企業組織在學習及使用關鍵知識時可能遭遇到的學習障礙,使它們能以最有效 率的方式學習並利用對它們在處理該危機時最有用的知識,進而增進其在危機管理方面 的績效。因此,本研究計劃將著重於探討企業組織應如何依據其所面臨之企業危機的特

性、以及處理該危機時的重要階段性任務的知識需求,來選用最適當的知識策略加以應 用,以便幫助其提升預防及處理潛在企業危機的能力,並減弱這些潛在企業危機對企業 組織之生存的威脅性。 研究方法 研究方法 研究方法 研究方法: 本研究採用個案分析法 (case study) 為主要的研究方法,目的在於深入瞭解,在一 企業組織中,當經理人員在預防及處理潛在企業危機時,會下哪一些與知識使用與管理 有關的決定? 為何他們會下這些決定? 這些決定是如何被員工所執行? 執行後又對該 企業的危機管理機制與成效造成何種影響? 在進行深入之個案研究時(in-depth case study),本研究中將採用 Yin (2003) 的建議,從多個不同來源收集所需要的資料 (data triangulation) , 以 確 保 研 究 結 果 之 結 構 有 效 度 (construct validity) 與 可 信 賴 度 (reliability);而所謂的”結構有效度”所關心的重點在於確認主觀意識對研究結果之正 確性是否有造成嚴重偏差。本研究之資料來源預計將包括企業內部文件、歸檔資料 (archival data)、與個人訪談資料。 在本研究中被分析之企業內部文件包括與所要調查之企業危機事件有關聯之個人 備忘錄、會議記錄、專案計劃報告等等。分析從企業內部文件所獲得之資料是十分重要 的,因為從這類資料所獲得的研究結果,可以用來與其他來源的資料之分析結果相互比 較查驗,進而加強分析結果的可信賴度;此外,企業內部文件也可提供我們企業內部人 員過往溝通過程的歷史記錄,而這些溝通的記錄也許會包含著與研究主題相關之重要資 訊。在本研究中將會被分析之歸檔資料 (archival data) 包括與所要調查之企業危機事件 有關聯之企業營運記錄、員工個人筆記及文件、報紙報導、雜誌報導、政府相關部門報 告等等。將歸檔資料 (archival data)作為資料來源也是必要的,因為它往往隱約地包括 了可以讓我們瞭解在某一段時間內與所要調查之企業危機事件有關聯的企業本身行為 與其員工個人行為的模式 (pattern);此外,此類資料也可讓我們經由交叉比對分析結果 的方式,來進一步確保得自其他資料來源之研究結果的有效度 (validity)。 至於個人訪談資料,則是最重要的一個資料來源。本研究採用半結構性訪談法 (semi-structured individual interviews) 來訪談數位至數十位研究合作企業的員工,以求能 從他們身上獲得大多數我們研究分析所需要的資料。在訪談過程中,受訪者將會被詢問 一系列與他們參與處理我們所正在研究的企業危機事件有關的個人經歷,比方說,他們 與同僚的互動、合作、分工,以期瞭解該企業在處理該危機事件時,其員工是如何管理 (例如:找尋、傳遞、分享) 他們的知識的。每次個人訪談的時間長度約為一至三小時。 本研究計劃中所做的所有個人訪談,均將在經由受訪者同意後錄音留存,隨後並以 電腦軟體逐行逐字的方式加以打字記錄,並轉換成電子文件以便保存。隨後,所有所收 集 的 訪 談 資 料 及 企 業 文 件 等 等 將 會 依 照 Lofland and Lofland (1995) 所 提 出 之 “Analytic Coding” 方法加以編譯。”Analytic Coding”的第一步驟亦稱為”Initial Coding”。在此步驟中,所有的資料將會被逐行逐字地檢視以決定有哪些資料是與我們 的研究相關而值得加以深入分析的。在完成編譯的第一步驟後,我們將會開始第二步

驟 – “Focus coding”。在”Focus coding”步驟中,編譯者將會將從第一步驟中篩選 出來的資料加以歸類與排序;在此過程中,資料編譯者也會依據研究主題對資料做更進 一步的檢查,並進一步捨去被認為與研究主旨無關或是關聯極小而不值得加以深入分析 之資料。在經過這兩個編譯步驟篩淢後所留存之資料碼 (codes),將會被用來就研究之 主旨作進一步的分析。 在資料編譯的過程中,我們將使用兩位編譯者交叉編譯相同的資料 (triangulation of coders),並將兩人編譯之結果加以比較修正。此作法之目的在於消除因個人對研究主題 之瞭解不同以及個人主觀意識 (subjectivity) 之不同所造成之編譯偏差 (biases),進而提 高資料的可信賴度 (reliability)。此外,在資料分析的執行部份,我們將採用 Yin (2003) 所提出之模式比對分析法(pattern matching) 來分析上述編譯過之原始資料。此資料分析 方法的主要原理,在於用模式比較的方式,來檢驗所收集的實證資料 (Trochim, 1989)。 換言之,為了探究某個特定的現象,分析者必須根據其研究理論架構或文獻評論之結 果,創造一個或多個假設性的行為模式 (predicted patterns),再將這些假設性的行為模 式,與從實證資料中探知之行為模式 (empirically-based pattern) 相比較;研究者經由檢 驗 實 證 資 料 之 行 為 模 式 (empirically-based pattern) 與 假 設 性 行 為 模 式 (predicted patterns) 之異同,來決定是接受或拒絕虛無假設 (null hypotheses)。經由使用模式比對 分析法,我們相信可以進一步地確保研究結果之內在有效度 (internal validity);而內在 有效度所關心的重點在於確認研究範圍內各重要因素之間的”因果關係”是否界定無 誤。 出席國際學術會議心得報告 出席國際學術會議心得報告 出席國際學術會議心得報告 出席國際學術會議心得報告: 請參閱附件一。 計畫成果 計畫成果 計畫成果 計畫成果: 本計畫針對申請人於其先前之研究成果中所提出的知識管理與危機管理整合的理 論架構進行進一步之理論補強與驗證。就申請人進行文獻蒐集評論以及與國內外知名學 者討論交流之結果顯示,不論在知識管理或是危機管理領域,此類相關研究均十分缺 乏。藉由本計畫之執行,我們已在此研究主題有理論上進一步的突破,建構出一個專為 協助企業組織執行危機管理相關工作之危機管理策略與知識策略結盟理論架構(a strategic alignment framework of crisis management strategy with knowledge strategy),並已 適當地使用實證資料對所提出之理論加以驗證。因此,我們認為本計劃之研究成果可以 幫助企業界之實務經理人在預防及處理企業危機方面,能有更全面性的瞭解,並提供實 用之指導綱領。因此,本計畫之研究成果無論在實用性或理論性方面,皆具有顯著之貢 獻。此外,我們已根據本計畫之研究成果,撰寫學術論文乙篇(請參閱附件二)。我們預 計在近日內,將該論文投稿至 Journal of Information Science (SSCI) 接受審查,以尋求 發表機會。若該論文能通過該期刊之審核並刊登,將可對我國之學術研究成績以及學術

研究會果之國際能見度有所貢獻。 結論 結論 結論 結論: 本計劃的執行唯一美中不足的一點,則是原先配合進行研究之企業組織內部之員 工,因某些不知名原因,而在研究計劃執行之後期,無法繼續提供研究人員所需的資料, 讓我們進行系統動力學的因果模型之建構與驗證。主要的原因據了解為該企業正逢業務 繁忙之際,經理人與員工們均缺乏再花費可觀的時間與我們進行討論之意願。雖然本計 劃之研究人員改採二手資料分析方法(secondary data analysis),搜尋與企業危機相關之文 件資料,包括現有相關文獻、報章雜誌之報導、公開發表之企業營運資料等等,來進行 分析,但仍然無法建構出讓我們研究人員認為具有一定程度的可信度之因果模型,。希 望日後若再度遭遇相同情形時,能在進行研究時程規劃時,先行了解合作之企業組織之 營運狀況,盡可能地避免其業務繁忙之時期,來進行重要之資料搜集或是合作之研究項 目。 儘管本計劃在執行期間有遭遇到上述之因境,整體而言,本計劃的執行仍然是成功 而有效率的。如同本報告前段所說明的,本計劃的執行使得我們發展出一個專為協助企 業組織執行危機管理相關工作之危機管理策略與知識策略結盟理論架構(a strategic alignment framework of crisis management strategy with knowledge strategy),並已適當地 使用實證資料對所提出之理論加以驗證。因此,本計劃的執行,不但使得我們在知識管 理與企業危機管理方面,有理論上的進一步突破,也為實務界的中高階經理人,提供了 一套實用之指導綱領。 參考文獻 參考文獻 參考文獻 參考文獻:

Lofland, J. & Lofland, L. H. (1995). Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis (3rd Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Richardson, B. (1994). “Socio-technical Disasters: Profile and Prevalence.” Disaster

Prevention and Management, 3(4), 41 – 69.

Salter, J. (1997). “Risk management in s disaster management context.” Journal of Contingencies and crisis management, 5(1), 60 – 65.

Trochim, W. (1989). Outcome pattern matching and program theory. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(4), 355 – 366.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zack, M. H. (1999). Developing a Knowledge Strategies. California Management Review, 41(3), 125 – 145.

附件一: 出席國際學術會議心得報告

出席國際學術會議心得報告

出席國際學術會議心得報告

出席國際學術會議心得報告

出席國際學術會議心得報告

計畫編號 NSC 96-2416-H-006-017- 計畫名稱 知識運用策略與危機管理策略之結盟對組織危機管理成效之影響分析 出國人員姓名 服務機關及職稱 王維聰; 國立成功大學工業與資訊管理學系助理教授 會議時間地點 民國 97 年 7 月 7 日至民國 97 年 7 月 9 日 於韓國首爾會議名稱 2008 International Conference on Business and Information

發表論文題目 Measuring Organizations’ Crisis Management Performance: An Exploratory Study

一、參加會議經過

We participated in the 2008 International Conference on Business and Information held in Seoul, Korea from July 7, 2007 to July 9, 2007. We went to the conference site along with a group of academics from several universities and arrived at around 8:00 am. Please refer to Figure 1 for the look of the site of the conference.

In the conference we presented a paper about how organizations can properly measure their crisis management performance in order to identify and eliminate their vulnerabilities to their potential business crises. The purpose to attend this conference was to get feedbacks on our paper from conference peer reviewers and participants so that we could continue to improve the quality of the paper and eventually get it published on a prestigious academic journal. In addition, by attending this conference, we were expected to get some new information about the research trend on knowledge management, crisis management, and information system implementation so that we could identify interesting and important research topics to explore for future progress on research development. Furthermore, we intended to learn more about the critical issues about e-commerce that concerned both academics and practitioners the most since we were planning to conduct research related to this particular research area.

Figure 1: Site of the BAI Conference

In addition to presenting the indicated paper, we also attended several sessions in which research papers related to knowledge management and e-commerce were presented and discussed. One example is the session “Business and Management” chaired by Dr. Poh Yen Ng from the Curtin University of Technology, Sarawak Campus, Malaysia. In this session five papers except ours were presented. The profiles of these five papers are as follows:

1. “Curtin graduate attributes: An exploratory study on business graduate in Curtin Sarawak” by Poh Yen Ng, Shamsul Kamariah Abdullah, Pai Hwa Nee, Nga Huong Tiew, and Chin Shin Choo.

Summary: The authors studied the degree to which Curtin Sarawak Business graduates have demonstrated Curtin Graduate Attributes in the workforce. The authors, based on the nine Curtin Graduate Attributes: Applying discipline knowledge, Thinking skills, Information skills, Communication skills, Technology skills, Learning how to learn, International perspective, Cultural understanding and Professional skills, developed a survey questionnaire to evaluate the importance level of the Curtin Graduate Attributes in meeting the needs of the Curtin graduates employers.

2. “Being expatriates in Thailand: Essential experience and knowledge” by Matorost Singhapong and Nuttawuth Muenjohn.

Summary: The authors investigated the work and personal related issues experienced by expatriate managers while they were working with local subordinates in Thailand. Data analyzed in this study was collected from 141 expatriate managers working in Thailand at the time of the study, who were

asked to respond on fifteen work and personal-related factors: culture; communication; interaction with subordinates; supervision; empowerment; work permit, opportunity to acquire skills; career advancement; adaptation of living styles, performance appraisals; work autonomy; career satisfaction; stress; negotiation styles; and health condition. The research results indicated that cultural differences, communication styles, relationships with subordinates, supervisory difficulties and inability to empower were the top five obstacles that encountered by the expatriates.

3. “On the determinants of corporate social responsibility: International evidence on the financial industry” by Hsiang_Lin Chih, Hsiang-Hsuan Chih, and Tzu-Yin Chen.

Summary: The authors empirically investigated Campbell’s (2007) theory. To achieve this purpose, the authors examined 520 financial firms in 34 countries during the 2003-2005 to offer a new understanding and greater insights into whether corporate social responsibility (CSR) is affected by financial and institutional variables.

4. “Management and strategy of legitimacy and reputation: Conceptual frameworks and methodology” by Keiichi Yamada.

Summary: The author discussed about the definition and concepts of legitimacy and reputation, relationship between them, and relationship between corporate reputation and corporate communication using his own communication models. Based on the results of an intensive literature reviews about legitimacy and reputation, the author developed a conceptual framework and methodology for management of legitimacy and reputation.

5. “Learning organization dimensions on knowledge sharing: A study of faculty members in the private universities in Malaysia” by Poh Yen Ng. Summary: The author used the learning organization dimensions populated by Watskins and Marsick in relation to knowledge sharing in private universities in Malaysia. Additionally, the author examined the extent of leadership role and organizational culture as possible motivators for building a learning organization. This study contribute to management professionals by enabling the management of universities/colleges to understand the factors motivating their employees share knowledge and thus provide suitable motivational programs, development opportunities and training programs.

二、與會心得

A significant number of studies in crisis management (CM) area have been conducted to explore how to enhance organizational performance by making use of

effective management activities in times of crisis. Based on the experience of attending this conference, it is found that research projects that aim to explore the relationships between crisis management and different corporate/functional management areas have been drawing the attention of both academic and practitioners. As a result, it is concluded that it is a research area with great potential and more research projects should be conducted to address the issues of crisis management in order to enrich our understanding about how organizations can continue to survive and prosper.

In addition, an emerging avenue of management-related research has been proved to be the alignment of strategies of different functional/conceptual areas. As a result, if one wants to make contributions to the knowledge base of management in any functional areas, he or she should focus on exploring issues related to the alliance, integration, and interactions of different management strategies.

附件二: 已撰寫完成之學術論文

Strategic Alignment of Knowledge Management and Crisis Management

Abstract

While most would agree that effective knowledge management can improve the management of a crisis, it is surprising how little research has been done in this area. In order to begin to address this deficiency, this study presents a framework designed to determine the whether and, if so, the extent to which knowledge management can positively impact crisis management (CM). The framework is the result of combining classic strategic CM frameworks with Zack’s framework of knowledge strategy. A case study of two energy companies in Taiwan is conducted to investigate the relationships between knowledge strategies and critical CM factors. Data analysis results indicate two main findings. First, an organization needs to employ different knowledge strategies at different phases of a business crisis to fulfill its different knowledge needs and, consequently, achieve the desired crisis management outcomes. Second, there exist significant relationships among knowledge strategies, crisis phases, and crisis characteristics, as summarized in nine theoretical propositions.

Keywords: knowledge management; crisis management; strategic alignment

1. Introduction

While numerous management methodologies and technologies have been developed to help business managers address the challenges they routinely encounter in their business environments, there are challenges that they face for which they are often unprepared. These challenges are the ones that result from low frequency, high consequence events that are commonly described as crises events. As evidenced by recent events, especially those in the global financial markets, the need to perform effective crisis management (CM) has never been greater and should not be ignored by business leaders (Hale, Hale, & Dulek, 2006; Ouedraogo, 2007). The potential impact of business crises is becoming more severe as the risk and uncertainty in the business environment, caused in part by the increasingly organized complex nature of business situations, increase (Hensgen, Desouza, & Kraff, 2003).

In order for organizations to prosper and survive, they must make the most effective use of their key resources and align these with their business strategies. This is especially true when dealing with crises. Unfortunately, one of the most valuable resources that organizations possess, knowledge, has been largely ignored in the CM literature. To address this deficiency, this study develops a strategic alignment framework that seeks to align CM strategy with knowledge strategy. Such an alignment, we contend, will contribute to more

effective CM.

Since crises evolve from an initiating event and progress through response and recovery phases, any effective alignment model must take these phases into consideration. By combining Mitroff’s (1988; 1994) CM strategy framework and the crisis classification framework developed by Chengalur-Smith, Belardo, and Pazer (1999), we have created an alignment framework that allows us to link the knowledge strategy (Zack, 1999) to each crisis phase. This conjoined framework provides insights into how organizations can align CM strategy and knowledge strategy in order to prevent, or at least minimize, undesired outcomes. In order to test our contention that alignment of CM strategy with knowledge strategy can help reduce the impact of crisis events, and that different knowledge strategies are needed for different phases of a crisis, we conducted an in-depth case study of two energy companies in Taiwan, both of which experienced the same type of business crises. This study enabled us to answer the following two research questions:

Q1. Does an organization tend to employ different knowledge strategies at different phases of a crisis in order to fulfill its different knowledge needs?

Q2. What are the relationships among knowledge strategies, crisis phases, and crisis characteristics?

The remaining structure of this paper is as follows: Section two reviews the literature on CM and KM, and section three discusses the details of the proposed strategic alignment framework. Section four discusses the research methodology, while section five presents the two cases, followed by the research findings in section six. Section seven presents the research implications, and section eight concludes this study with a discussion of its limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1 KM and its Employment in CM

Asoh, Belardo, and Duchessi (2007) contended that there was considerable confusion in the KM literature concerning the meanings of key KM-related terms, such as knowledge strategy (KS) and knowledge management strategy (KMS), and argued that such confusion would render organizations unable to adequately address how to properly situate KM concepts to correspond to organizational variations and strategic concerns. As such, it is necessary to distinguish between these two key terms.

In order to achieve a unique set of goals and enhance overall performance, organizations need to develop business strategies and identify the knowledge needed to ensure the successful implementation of these goals. But as business strategies change, so will the knowledge required. The difference between the knowledge that an organization needs and the knowledge it possesses is called the knowledge gap. The purpose of KS is to close or minimize this gap (Zack, 1999). Consequently, KS is used to help organizations determine

what to do with their knowledge in order to meet their performance goals (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996). Examples of KS frameworks include those proposed by Bohn (1994), De Long and Seemann (2000), Gopalakrishnan and Bierly (2006), Mitchell (2006), and Zack (1999). On the other hand, KMS is used to address the question of how to do it (Asoh et al., 2007). Examples of KMS frameworks include those proposed by Grant (1996), Davenport and Prusak (1998), Hansen, Nohria, and Tierney (1999), Earl (2001), Gold, Malhotra, and Segars (2001), and Choi and Lee (2003).

Business crises are low frequency, high consequence events (Hensgen et al., 2003; Pearson & Clair, 1998) that are characterized by uncertain causes and effects and can severely threaten the integrity of an organization. Corresponding to this definition of business crises, CM can be defined as a set of on going, systematic, and interrelated processes for identifying, analyzing, treating, and learning about business crises by means of applying management strategies and practices (Mitroff, 1994). A strategy can be thought of as a joint description of the objectives of organizations, the practical actions performed with intent to achieve these objectives, and the corresponding decisions for resource allocation (Chandler, 2000; Chrisman, Hofe, & Boulton, 1988). Consequently, based on this definition, it is argued that CM strategies (CMS) focus on addressing the question of what organizations should consider in order to make appropriate decisions, from various perspectives, for managing their business crises.

Using KM concepts to perform strategic CM has been discussed in the existing CM literature, although mostly in a very implicit way. This research may be grouped into three main categories. The first category addresses the importance of KM in terms of helping organizations acquire critical knowledge for managing business crises through effective learning processes (Boin, 2004; Nunamaker, Weber, & Chen, 1989; Simon & Pauchant, 2000; Weick, 1993; Weick & Roberts, 1993; Wilkinson & Mellahi, 2005). The second category concerns the issue of recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of an organization’s KM capabilities (Elsubbaugh, Fildes, & Rose, 2004; Nishiguchi & Beaudet, 1998; Quarantelli, 1988; Zhang, Zhou, & Nunamaker, 2002). Studies that fall into this category address the importance of the application of various kinds of technologies and methods to facilitate knowledge acquisition, sharing, distribution and storage. The third category concerns the sources of critical knowledge which can enhance the effectiveness of organizations’ CM efforts (Darling, 1994; Lagadec, 1997; Shrivastava & Mitroff, 1987). Studies that fall into this category emphasize the need to develop efficient and effective means of locating and acquiring knowledge critical for managing a business crisis. Despite the contributions of the se existing CM studies, very limited research has been explicitly dedicated to CM-related reasoning from a KM perspective.

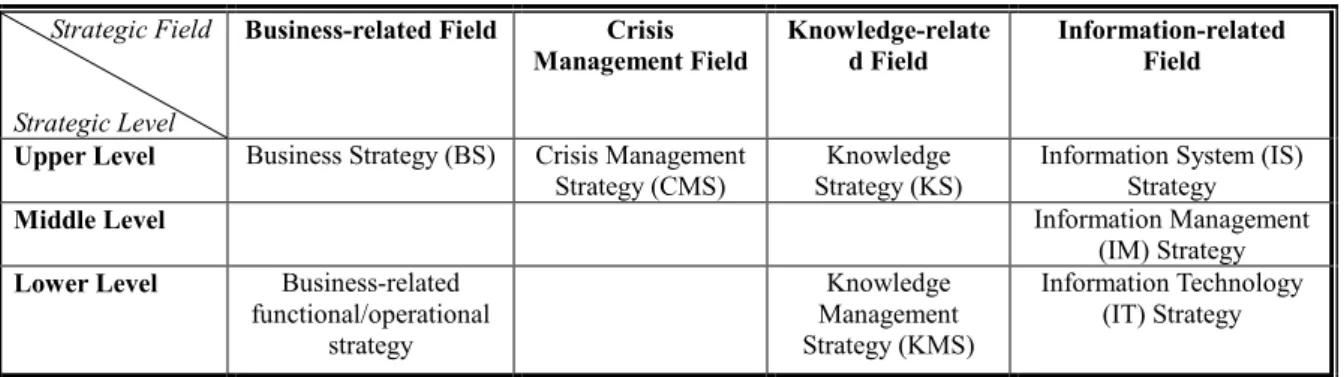

A review of the literature confirms that alignment of organizational resources, such as information, with business strategies plays a crucial role in ensuring successful business operations (e.g., Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Burgelman & Doz, 2001; Cragg, King, & Hussin, 2002; Rogers & Bamford, 2002; Sabherwal & Chan, 2001). From the perspective of information management, which can be considered the reference field of KM (Abou-Zeid, 2002; Asoh et al., 2007), there are three main streams of strategic alignment: the alignment of business strategy (BS) with information technology (IT) strategy (e.g., Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Henderson & Venkatraman, 1999; Pollalis, 2003); the alignment of BS with information system (IS) strategy (e.g., Sabherwal & Chan, 2001; Segars & Grover, 1998); and the alignment of BS with information management (IM) strategy (e.g., Rogers & Bamford, 2002). In addition, an important stream of strategic alignment that is not directly associated with information technology is the strategic alignment of BS and organizational resources in general (e.g., Burgelman & Doz, 2001; Van Den Hooff, Vijvers, & De Ridder, 2003).

In order to properly select a knowledge-based strategy construct for this study, an examination of the existing knowledge-based constructs is required from a strategic-level perspective. Asoh et al.’s (2007) defined information as the organized data and facts that existed outside the minds of individuals, and knowledge as the personal capability and capacity of individuals to perform specific actions. They viewed information-related strategies, such as the IM, IT, and IS strategies discussed previously (Earl, 1989), as enablers of all other types of organizational strategies. As a result, they believed that information was to the IS/IM/IT fields as knowledge was to the KM field. Based on this belief, they clarified the relationships existing among BS, KS, and IS by arguing that both BS and KS operated at a higher strategic level in order to make it possible for organizations to address not only the question of what to do, but also where, when, why, and who questions. Asoh et al. contended that IS served as an enabler of BS and KS at the same strategic organizational level. Correspondingly, they argued that KM and functional/operational strategies operated at a lower strategic level for the purpose of addressing how organizations might accomplish the tasks identified by BS and KS, while IT served as an enabler at the same lower strategic level. Finally, they argued that IM resided at a middle level between IS and IT and supported both.

Pearson & Rondinelli (1998) contended that it was crucial for organizations to treat CM as “an integral part of their overall business strategies.” Consequently, it is argued that CMS, such as those espoused by Mitroff (1988), mainly focuses on addressing the issue of what to do in the CM area, as BS and KS do in their respective areas. As a result, it is proposed that CMS are analogous to both BS and KS, operating at an upper strategic level of organizations for the purpose of effectively managing potential business crises, as is shown in Table 1. Since both CMS and KS operate at the same strategic level, it is more appropriate to align CMS with KS than with KMS.

2.3 Remarks about the Existing Literature

The KM, CM, and strategic alignment studies discussed earlier make clear the need for organizations to implement, based on their knowledge needs, knowledge-related strategies in times of crisis. These strategies can help decision makers learn how to continuously expand their business crises knowledge base and improve decisions concerning, for example, the choice of learning sources (e.g., internal or external) and learning means (e.g., exploitation or exploration). However, despite the contributions of the existing CM studies, very few of them have been explicitly dedicated to CM-related reasoning from a KM perspective. In addition, most of the existing CM studies mentioned earlier that implicitly address the need of KM in CM generally focus on how organizations can process their knowledge by taking advantage of various kinds of technologies and managerial systems, which is what KMS intends to address, rather than addressing the question of what organizations should do with their knowledge, which is the aim of KS.

Furthermore, none of the existing CM studies explicitly discuss the relationships between the application of KM concepts and critical CM-related factors, such as crisis phases, crisis characteristics, and crisis types. For example, Weick (1993) and Weick and Roberts (1993) addressed the importance of the concept of continued learning and the barriers to learning continuously during and in response to crises. Quarantelli (1988) recognized the existence of a gap between what people perceived and what they really encountered in a crisis. However, neither of these, nor any of those discussed above address the relationships between the application of KM concepts and CM-related factors, such as critical crisis phases and characteristics of crises, in terms of the influence of the alignment of KM and CM.

The lack of alignment research of CMS and KS has led to a significant gap in both theory and practice. In a manner similar to that employed in previous strategic alignment studies, this study aims to propose an alignment framework of CMS with KS.

3. An Alignment Framework of CMS with KS

Boin (2004) stressed the importance of having a well-organized approach to help managers conceptualize the dynamic processes of business crises that had different individual features. To address this perspective, Mitroff’s (1988; 1994) CMS framework (see Table 2) is adopted in this study for two reasons. First, this framework segments a crisis into five phases based on the most crucial tasks which managers must attention to at each phase of a crisis (Pearson & Rondinelli, 1998). This helps the organization identify what knowledge it needs in order to perform these tasks successfully. Second, Mitroff’s framework incorporates the concept of learning, which explicitly identifies the need for KM in times of crisis, since knowledge is the primary product of learning. Mitroff’s final crisis phase, learning, can be considered a wrap-up phase at which organizations summarize what they have learned and

embed it into organizational structures, such as organizational regulations and operational protocols, to improve their chances of surviving future crises.

(Table 2 presented here)

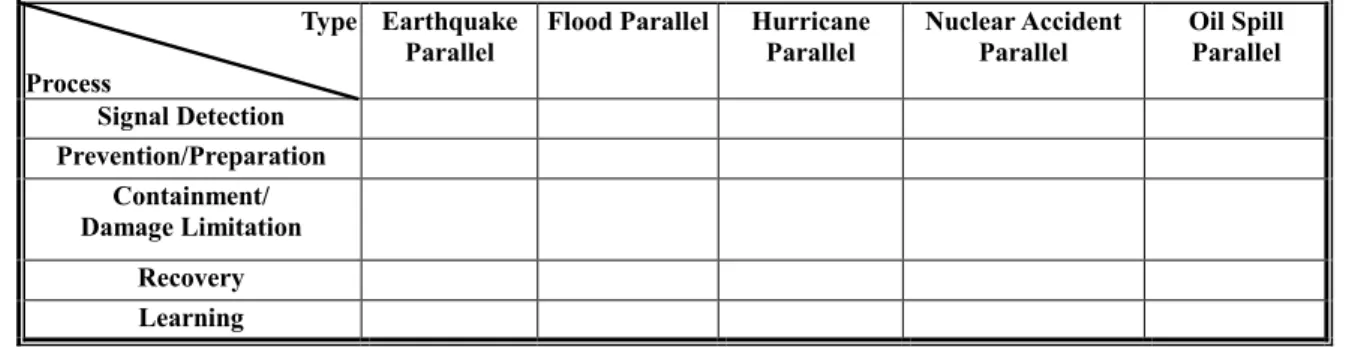

Additionally, the crisis classification framework proposed by Chengalur-Smith et al. (1999) is adopted in this study. In their framework, the type of a business crisis can be determined by evaluating its degree of similarity to each of the five major natural and man-made disasters: earthquakes (EQ), floods (FL), hurricanes (HC), nuclear accidents (NA), and oil spills (OS). Such an evaluation is performed by examining the four macro factors and associated micro characteristics of a crisis (see Table 3). Chengalur-Smith et al. have thus classified a number of business crises according to the five parallel categories: earthquake parallel, flood parallel, hurricane parallel, nuclear accident parallel, and oil spill parallel.

(Table 3 presented here)

A CMS framework that is developed by combining these two frameworks can benefit organizations in two ways. First, it specifically identifies the most critical tasks organizations need to perform at specific phases of certain types of crises. Second, it enables organizations to gain better insight into business crises by examining them using the methods previously used to analyze their parallels in the area of natural hazards, on which considerably more data has been gathered and analysis done, and consequently facilitate the execution of effective learning activities. For example, an organization may categorize a potential business crisis as parallel to an earthquake. This perception enables the organization to immediately determine, with reference to the abundant knowledge base of earthquakes, that this business crisis, like an earthquake, has very low predictability and very limited forewarning. As a result, among other recommendations, a computer simulation should be designed to help crisis managers constrained by the very limited response time for the organization. In this way, the simulation results can better reflect what would actually happen in the real world and in turn could the organization acquire more accurate insights and high-quality knowledge regarding this particular crisis.

Among existing KS frameworks, Zack's (1999) knowledge-based SWOT analysis (K-SWOT) framework is preferable for this study. Zack’s framework is appropriate for our analysis because it aims to associate an organization’s competitive strategy with its knowledge resources and capabilities. As a result, it is easy for organizations to develop practical and effective KS based on their “knowledge resources and capabilities against their strategic opportunities and threats” (Zack, 1999, p. 131) and, in turn, to take appropriate strategic actions when facing emergent and unexpected crisis events.

Zack’s (1999) framework of KS consists of two dimensions. The first addresses the degree to which an organization focuses more on applying its existing but underutilized knowledge (knowledge exploitation) or on increasing its knowledge in a particular professional domain (knowledge exploration). In other words, this dimension concerns itself

with the extent to which an organization is mainly a knowledge creator (an explorer), a knowledge user (an exploiter), or a combination of both (an innovator). The second dimension is concerned with whether the primary sources of the knowledge of an organization are internal, external, or are both, which is referred to as unbounded. Zack's KS framework is presented in Figure 1.

(Figure 1 presented here)

Zack (1999) argued that organizations that primarily focused on exploiting internal knowledge employed the most conservative KS. These organizations (internal exploiters) have sufficient knowledge resources to keep themselves competitive in their industries, and mainly focus on exploiting their internal knowledge bases in order to identify or create even more competitive advantages. Organizations that focus on both exploring external knowledge resources to develop new knowledge bases and exploiting internal knowledge bases in the search for business opportunities can be thought of as employing the most aggressive KS. These organizations (unbounded innovators) focus on both acquiring knowledge capital from their external environment and creating benefits by utilizing it. Zack contended that organizations in knowledge-intensive industries would perform better compared to their competitors if they used relatively aggressive KS.

To conclude, the frameworks of Mitroff (1988) and Chengalur-Smith et al. (1999) are employed to address critical CM aspects, while Zack’s (1999) KS framework is selected to help identify the knowledge appropriate to each main crisis phase in this study. As a result, on the basis of the concept of the strategic alignment of CMS with KS, a comprehensive framework can be constructed, as presented in Table 4.

(Table 4 presented here)

4. Research Methodology 4.1 Data Collection

This study adopted an exploratory, in-depth case study approach to address the research questions presented earlier. Two natural gas companies in Taiwan that both experienced the same type of business crisis were selected as cases for this study. Pseudonyms were selected for all the research subjects to ensure confidentiality. Data for this study was collected from multiple sources for the purpose of carrying out data triangulation (Sieber, 1973). The data sources are described as follows:

1. Data from nineteen semi-structured, face-to-face personal interviews with five top executives, eight line managers, and six employees at their offices;

2. documents from participating organizations, such as memos, personal notes, project review meeting minutes and reports, and pre-assessment reports of projects that were related to the target crises; archival data from local newspapers and governmental reports regarding the crises investigated.

Additionally, before the data collection process officially began, the sample interview questions, data collection protocols, and data analysis techniques to be used in this study were sent to the academics and practitioners with relevant expertise for their evaluation, and pilot interviews with two key informants were conducted in order to validate the interview instruments. Furthermore, the draft of the data analysis report was sent to four key informants in the participating organizations for review in order to further validate the research findings. As a result, it is believed that the construct validity and reliability of this study were ensured (Yin, 2003).

4.2 Data Analysis

Generally, this study adopts the logic of grounded theory for data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1997), which can be summarized by the following four characteristics. First, the researchers engaged in data analysis while collecting data. This allowed the researchers to gradually adjust the orientation of their data collection procedures based on the improving understanding of the research topic, which made the collected data become more focused. Second, the method of analytic coding (Lofland & Lofland, 1995) was adopted for the data coding process. In the first stage of initial coding, the data collected was examined line by line in order to identify statements related to the study. When initial coding was completed, the second stage of focus coding began, in which the codes were sorted and categorized based on their conceptual similarities. During the process of sorting and categorizing codes, codes that were considered irrelevant or relatively less productive were discarded. The remaining codes were then reexamined and their concepts were further elaborated for future analysis.

Third, the researchers used an inductive logic for data analysis in order to identify critical themes related to the research topic. These themes were then further analyzed using the analysis technique of pattern matching in order to ensure internal validity (Yin, 2003). The logic of pattern matching is to compare an empirically-based pattern or a rival pattern with one or multiple-predicted patterns (Trochim, 1989). If the patterns are identical, the internal validity of the case study is strengthened. If there are two potential patterns, the task is to first determine whether the data matches one pattern better than the other, and then to appropriately explain and organize what was observed from the collected data. Fourth, the validity of the data analysis results was checked and verified by the research participants through follow-up interviews.

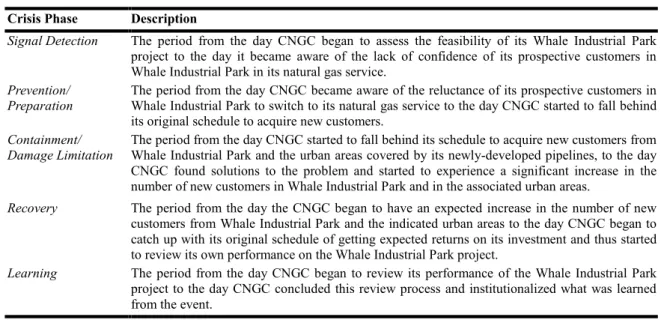

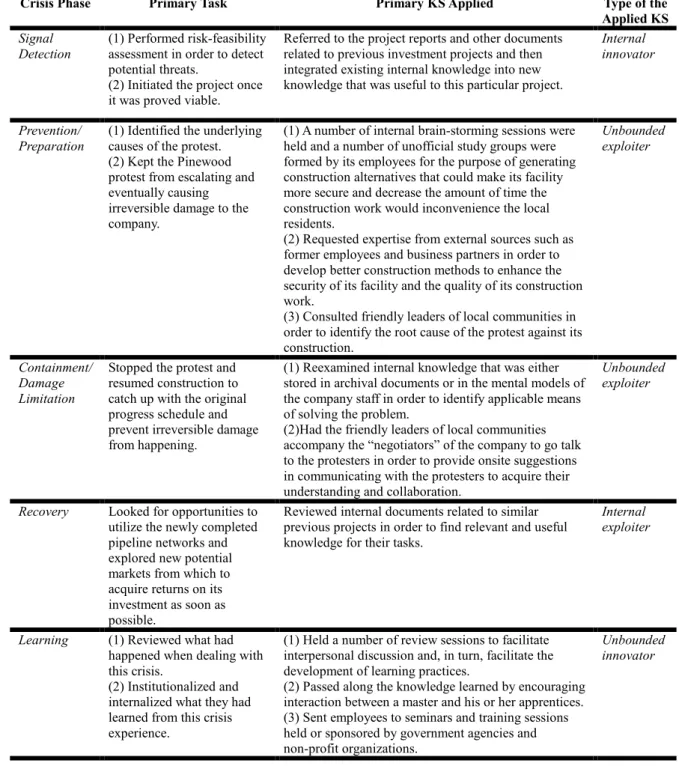

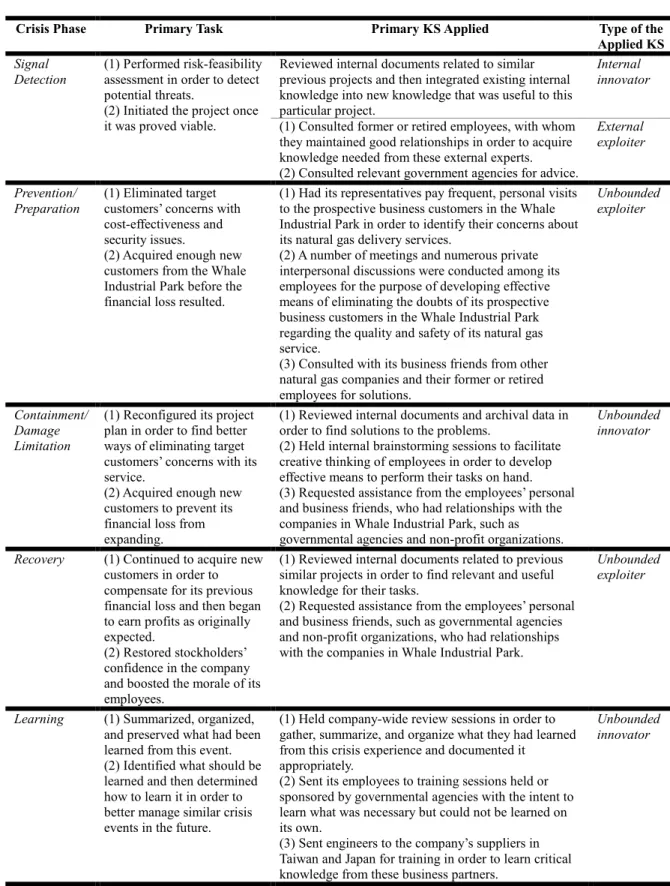

5. Application of the Proposed Framework: Case Analysis of Two Crises

To examine the propositions above, the proposed alignment framework of CMS with KS was applied to two energy companies, Pier (PNGC) and Central (CNGC) Natural Gas Corporations, both of which had experienced the same type of business crisis. The general descriptions and decompositions with reference to Mitroff’s (1988) framework of the

individual crises of these two companies are summarized in Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8. (Table 5 presented here)

(Table 6 presented here) (Table 7 presented here) (Table 8 presented here)

As discussed previously, crises can be classified by using Chengalur-Smith et al.’s (1999) crisis categorization framework (please refer to Appendix I for the details of their method). Generally, within this framework, a business crisis can be classified into one of the five reference types by performing two processes. The first process is designed to assess each business crisis according to eight well-established crisis characteristics (e.g., exposure and destructive potential). This is done using a three-point (high, medium, low) scale. The profiles of the two studied crises in terms of this scale are summarized in Table 9.

(Table 9 presented here)

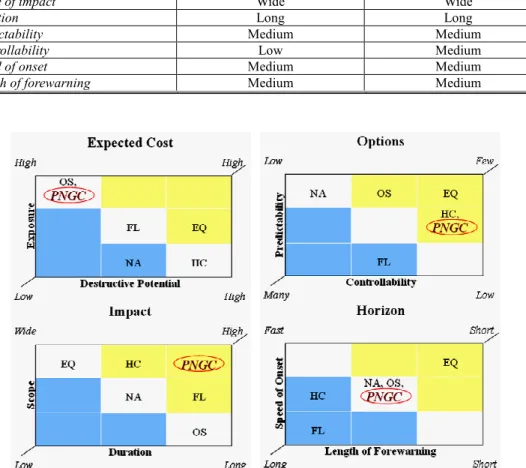

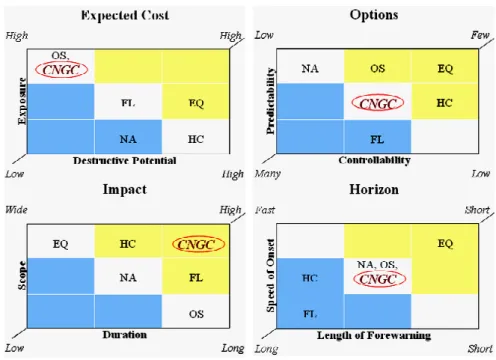

The second process is designed to determine the degree to which a business crisis differs from each of the five reference types. To do this each business crisis is evaluated, using the eight crisis characteristics, on two levels, macro and micro. The four macro factors in Chengalur-Smith et al.’s (1999) framework are expected cost, impact, options, and horizon. Each of these macro factors is evaluated along a continuum (low to high) that constitutes the micro level as presented in Figures 2 and 3. Based on these four-factor models, the sum of both macro factors and micro factors of the two studied crises can be calculated based on the degrees of their eight crisis characteristics, as presented in Figures 4 and 5.

(Figure 2 presented here) (Figure 3 presented here) (Figure 4 presented here) (Figure 5 presented here)

With reference to the results of the crisis profile analysis outlined above, both business crises studied deviate less from the OS than from the other four generic crisis types, and therefore they are both categorized as crises that are parallel to the OS. An important implication of this categorization analysis is that although the two crisis cases are not identical, they share a significant enough degree of similarity in terms of their key crisis characteristics to be categorized as the same parallel crisis type, an oil spill. Such categorization efforts can help organizations gain better insight into their business crises by examining them using the methods previously used to analyze the same types of previous business crises or similar natural hazards. This, in turn, can facilitate the execution of effective learning activities.

6. Research Findings

crisis phases, and crisis characteristics are examined and summarized in the form of theoretical propositions in the following sections.

6.1 The Employment of KS at Different Crisis Phases

Tables 10 and 11 summarize the KS used at each phase of the business crises of the participating companies. An important implication that emerges from Tables 8 and 9 is the trend of using different KS at different crisis phases. There are two key observations related to the determination of the trend of employing different KS at different phases of business crises. First, both participating companies employed different KS at different phases of their respective business crises in order to fulfill their different knowledge needs for performing critical CM tasks at the different phases. Second, in three out of five crisis phases, CNGC employed knowledge strategies that were different from those used by PNGC in the corresponding phase, resulting in the different outcome. This implies that an organization has different CM tasks to accomplish and different corresponding knowledge needs that require the use of different KS at different phases of a particular crisis. Based on these observations and in response to our first research question, the following proposition is raised:

P1. An organization tends to employ different KS at each of the five crisis phases of a business crisis in order to satisfy its different knowledge needs.

(Table 10 presented here) (Table 11 presented here)

6.2 The Employment of KS at the “Signal Detection” Phase

The medium predictability characteristic of the OS-type business crisis implies that this kind of crisis is moderately predictable if the task of signal detection can be effectively performed. The research results indicate that employees of the two participating companies had neither well-developed procedures for monitoring unusual phenomena, which were the warning signals of potential business crises, nor clear definitions of what qualified as warning signals. Because of this, they were incapable of distinguishing the warning signals of their potential business crises from their everyday, normal business operations, and thus prevent them. As a result, well-defined policies for monitoring such warning signals and clear definitions of what constitutes a warning signal needed to be developed to enable these companies to take effective actions to prevent business crises.

Our case analysis suggests that the exploitation of external knowledge is the key to properly defining the properties of the warning signals of OS-type business crises, thus leading to the development of well-structured signal detection policies. These policies can help companies proactively look for warning signals and eventually make similar events more predictable in the future. For example, CNGC took its crisis as an opportunity to learn more about its business. As a result, it actively sought suggestions from experts from inside

and outside the company. Although it was unable to prevent its crisis, it did learn much at this phase, particularly from experts in other organizations. For instance, by learning from governmental agencies affiliated with Chain City, CNGC acquired knowledge about future urban development, which was very valuable for them to accurately evaluate their business opportunities in the potential markets. As a result, they eliminated one of their weaknesses when planning for investment projects in the future. Generally, their efforts in exploiting external knowledge helped ensure that they would not complete this phase empty-handed. As a CNGC employee stated:

“The people we consulted were our friends in the agencies of the city government, such as the Department of Economic Development, Department of Urban Planning, or the Department of Environmental Protection. We got a lot of valuable opinions from them, since they had social connections and relationships with those manufacturers in the park and they could help us detect the thoughts of those business units about getting alternative energy sources.”

To conclude, the relationship among KS, signal detection phase, and the predictability of a crisis is summarized in the following proposition:

P2. The degree of effort which an organization makes to exploit knowledge from external sources at the signal detection phase of a business crisis has a positive influence on the degree of the predictability of the crisis.

6.3 The Employment of KS at the “Prevention/Preparation” Phase

The medium speed of onset and medium length of forewarning characteristics of the OS-type business crisis imply that this kind of crisis does not cause actual damage very quickly after its initial warning signals become detectable. As a result, a company which has detected the warning signals of an OS-type business crisis has a considerable amount of time to take effective action to either prevent it or to be well-prepared to resolve it before actual damage is caused.

For example, during PNGC’s crisis their internal knowledge was not sufficient to generate acceptable solutions, and as they had a considerable amount of time before the hostile local residents could take actions that would force them to cease their pipeline construction, they sought expertise from external sources. As a PNGC employee stated:

“We consulted some of our retired employees to get their suggestions and we got many useful thoughts from them. In addition, we also looked for help from our business partners and other natural gas companies and adopted some of their suggestions.”

Although the efforts of PNGC at this crisis phase did not help it prevent protests, it was able to find the most critical but implicit cause that was responsible for protests: manipulation of the public by politicians. A highly competitive local political campaign was scheduled to be held at this time. In order to increase their exposure in the press and in turn improve their reputations, some local politicians made the promise to protesters that they would prevent PNGC from continuing construction in their town, no matter what happened in the future. These politicians continued to lead the protests against PNGC’s construction plan after the campaign in 1998 for their own publicity purposes. As a PNGC employee recalled:

“We consulted our connections and friends who were familiar with the political and business environments of Pinewood, and finally we figured out what was really going on there. Apparently, it was never about the security concern of residents in Pinewood.”

Since PNGC had obtained the proper authorization for performing its construction, it had anticipated that the residents of Pinewood would protest the project and eventually force its adjournment. However, the problem was not totally undetectable or inevitable. A PNGC employee provided a moderate judgment regarding the problem by saying:

“We were not aware of this problem, since we got the consent for construction from their official authorities before we started to carry out our construction work……I think that we would have been more likely to detect this potential problem beforehand if we had done a better job of communicating with people to know better how they thought about the project and figuring out what factors made protestors decide not to allow us to do construction in their town.”

The above statement implies that if PNGC’s staff had done a good job of communicating with Pinewood residents about the natural gas industry and in turn gained their trust, the local politicians would not have had the chance to further escalate the protest for their own benefits, and they would have had more time to develop effective counteractions in response to this problem. The above discussions indicate that the more efforts PNGC could have made to exploit external knowledge, the longer the length of forewarning and the lower the speed of onset of its crisis could have been, and the more likely it could even have prevented the crisis. Consequently, the relationships among KS, prevention/preparation phase, and the speed of onset and the length of forewarning of a crisis are summarized in the following propositions: P3. The degree of effort which an organization makes to exploit knowledge from external

sources at the prevention/preparation phase of a crisis has a negative influence on the speed of onset of a crisis, and, in turn, has a positive influence on the organization’s performance at this crisis phase.

P4. The degree of effort which an organization makes to exploit knowledge from external sources at the prevention/preparation phase of a crisis has a positive influence on the length of forewarning of the crisis, and, in turn, has a positive influence on the organization’s performance at this crisis phase.

6.4 The Employment of KS at the “Containment/Damage Limitation” Phase

Research results imply that OS-type business crises have two characteristics that are associated with the organizational task of containment/damage limitation: low to medium controllability and long duration. Low to medium controllability indicates that organizations have limited options to control the impact of an OS-type business crisis. As a result, organizations should employ aggressive KS in order to increase their chance of identifying effective options to limit the damage. Although it takes relatively more time and organizational resources to enforce such an aggressive KS, the long duration means that organizations have the time to take aggressive actions. In addition, this relatively long containment/damage limitation phase implies that it is necessary for organizations to adopt aggressive actions in order to shorten this crisis phase, and, in turn, limit the damage caused.

In CNGC’s crisis, at the beginning of this phase its employees were struggling to find or create useful knowledge from their internal intellectual resources which could help them better ensure the safety of the natural gas facilities or install natural gas equipment in a more economical way. They looked to personal and business friends, such as their former employees, business partners, and leaders of local communities. The exploitation of external knowledge provided by their friends was useful. They finally managed to utilize the suggestions from one of their suppliers to create a better process with the help of new equipment for monitoring the conditions of their natural gas facilities in order to ensure the safety of the surrounding environment.

However, their goal of finding a more economical way to develop and install natural gas equipment in order to reduce the initial installation cost of their prospective customers was not achieved, despite their utilization of both internal and external knowledge. Help then came from an unexpected external source. CNGC managed to work with its potential customers in Whale Industrial Park, and even to work with the manufacturers of the energy-generating systems of these prospective customers through references from the latter. This method proved successful when it was applied to many of CNGC’s potential customers. As a CNGC employee stated:

“We worked with our prospective customers to find a better way to transform their energy generating systems, and it helped us a lot most of time since they knew their internal structure better than we did, and their opinions stimulated lots of new thoughts on our side. In addition, we asked for information and suggestions from the providers of

our prospective customers’ energy generating equipment. It also helped a lot, since we could know more about the equipment and have more information on how we might be able to modify it to fit our needs.”

The statement above indicates that CNGC not only exploited both internal and external knowledge at this phase, but also integrated the available knowledge from all sources to generate new techniques and processes. These new technologies and processes helped improved the safety of the natural gas facilities, and ensure economical installation of equipment. They also helped improve service quality with the result being a gain in customer trust. According to Zack’s (1999) framework, the KS applied by CNGC at this phase was the unbounded innovator,. The application of this KS allowed CNGC the opportunity to attract more potential customers, by enabling greater control over its crisis situation. Additionally, the solutions generated by the application of this KS enabled CNGC to acquire these customers in a faster and easier manner, which allowed them to shorten the duration of the crisis.

To conclude, the research results suggest that organizations should employ the aggressive KS of unbounded innovator in order to find timely solutions to their problems at this phase. The relationships among KS, containment/damage limitation phase, and the controllability and duration of a crisis are summarized in the following propositions:

P5. The degree of effort which an organization makes to integrate knowledge from both internal and external sources into new knowledge at the containment/damage limitation phase of a crisis has a positive influence on the controllability of the crisis, and, in turn, has a positive influence on the organization’s performance at this crisis phase.

P6. The degree of effort which an organization makes to integrate knowledge from both internal and external sources at the containment/damage limitation phase of a crisis has a negative influence on the duration of the crisis, and, in turn, has a positive influence on the organization’s performance at this crisis phase.

6.5 The Employment of KS at the “Recovery” Phase

The wide scope of impact characteristic suggests that individuals involved in managing an OS-type business crisis are likely to come from multiple departments, or even from multiple organizations. For example, PNGC’s investment project was a company-wide activity, and most of PNGC’s employees were sharing some responsibility for making progress on the project. The impact of the crisis event was also wide-spread outside PNGC as well. Many organizations, such as governmental agencies, companies in the Dolphin Industrial Park, and suppliers and business partners of PNGC, were counting on the execution and success of the constructions for PNGC’s project to earn either tangible or intangible profits. All of these businesses and governmental agencies were forced to modify their